West Bengal Population Census 2011 | West Bengal Religion, Caste Data - Census 2011

As per the Census 2011, the total Population of West Bengal is 9.13 Cr . Thus the population of West Bengal forms 7.54 percent of India in 2011. West Bengal has total population of 91,276,115 in which males were 46,809,027 while females were 44,467,088.

Total area of West Bengal is 88,752 square km. Thus the population Density of West Bengal is 1,028 per square km which is lower than national average 382 per square km.

West Bengal Literacy Rate - Census 2011

The total literacy rate of West Bengal is 76.26% which is greater than average literacy rate 72.98% of India. Also the male literacy rate is 81.69% and the female literacy rate is 70.54% in West Bengal.

West Bengal Sex Ratio - Census 2011

The average sex ration is the number of females per 1000 males. As per the Census 2011, the Average Sex Ration of West Bengal is 950 which is above than national average of 943 females per 1000 males. Also the child sex ration (age less than 6 years) of West Bengal is at 956 which is higher than 918 of India.

West Bengal Working Population - Census 2011

In West Bengal out of total population, 34,756,355 were engaged in work activities. 73.9% of workers describe their work as Main Work (Employment or Earning more than 6 Months) while 26.1% were involved in Marginal activity providing livelihood for less than 6 months. Of 34,756,355 workers engaged in Main Work, 4,203,767 were cultivators (owner or co-owner) while 5,869,498 were Agricultural labourer.

West Bengal Urban/Rural Population - Census 2011

As per the Census 2011 out of total population of West Bengal, 31.87% people lived in urban regions while 68.13% in rural areas. The total figure of population of urban population was 29,093,002 out of which 14,964,082 were males while remaining 14,128,920 were females. In rural areas of West Bengal, male population was 31,844,945 while female population was 30,338,168.

The average sex ratio in urban regions of West Bengal was 944 females per 1000 males. Also the Child (0-6 age) sex ration of urban areas in West Bengal was 947 girls per 1000 boys. Thus the total children (0-6 age) living in urban areas of West Bengal were 2,760,756 which is 9.49% of total urban population. Similarly the average sex ratio in rural areas of West Bengal was 953 females per 1000 males. The Child sex ratio of rural areas in West Bengal was 959 girls per 1000 boys.

The average literacy rate in West Bengal for urban regions was 84.78 percent in which males were 88.37% literate while female literacy stood at 80.98%. The total literate population of West Bengal was 61,538,281. Similarly in rural areas of West Bengal, the average literacy rate was 72.13 percent. Out of which literacy rate of males and females stood at 78.44% and 65.51% respectively. Total literates in rural areas of West Bengal were 39,213,779.

List of Districts in West Bengal

List of districts of West Bengal with Population, Literacy rate, Sex Ratio etc. As per the Census 2011, West Bengal is divided into 19 districts (zilla) which act as the administrative divisions. North Twenty Four Parganas is the largest district of West Bengal by population, while the least populated district of West Bengal is Dakshin Dinajpur .

Below is the complete list of districts ( zilla ) of West Bengal sorted by population.

WEST BENGAL CENSUS-2011

According To Census 2011, West Bengal Has Population Of 9.13 Crores, An Increase From Figure Of 8.02 Crore In 2001 Census. Total Population Of West Bengal As Per 2011 Census Is 91,276,115 Of Which Male And Female Are 46,809,027 And 44,467,088 Respectively. In 2001, Total Population Was 80,176,197 In Which Males Were 41,465,985 While Females Were 38,710,212. The Total Population Growth In This Decade Was 13.84 Percent While In Previous Decade It Was 17.84 Percent. The Population Of West Bengal Forms 7.54 Percent Of India In 2011. In 2001, The Figure Was 7.79 Percent.

West Bengal Population Census 2011

As Per Details From Census 2011, West Bengal Has Population Of 9.13 Crores, An Increase From Figure Of 8.02 Crore In 2001 Census. Total Population Of West Bengal As Per 2011 Census Is 91,276,115 Of Which Male And Female Are 46,809,027 And 44,467,088 Respectively. In 2001, Total Population Was 80,176,197 In Which Males Were 41,465,985 While Females Were 38,710,212. The Total Population Growth In This Decade Was 13.84 Percent While In Previous Decade It Was 17.84 Percent. The Population Of West Bengal Forms 7.54 Percent Of India In 2011. In 2001, The Figure Was 7.79 Percent.

West Bengal Literacy Rate Census 2011

Literacy Rate In West Bengal Has Seen Upward Trend And Is 76.26 Percent As Per 2011 Population Census. Of That, Male Literacy Stands At 81.69 Percent While Female Literacy Is At 70.54 Percent. In 2001, Literacy Rate In West Bengal Stood At 68.64 Percent Of Which Male And Female Were 77.02 Percent And 59.61 Percent Literate Respectively. In Actual Numbers, Total Literates In West Bengal Stands At 61,538,281 Of Which Males Were 33,818,810 And Females Were 27,719,471.

West Bengal Decadal Growth Rate Census 2011

According To The Census Of India, Ministry Of Home Affairs, The Decade Of 2001 To 2011 Is The 1st Decade Post Indian Independence, Which Added Least Number Of People To The Country's Population. The Percentage Of Decadal Growth In The Nation, For The First Time, Showed A Decrease By 3.90 % Since, The Present Census Of India 2011 Has Registered The Rate To Be 17.64 % From The Rate Of 21.54 % In The Earlier Census Conducted In The Year 2001

West Bengal Sex Ratio And Child Sex Ratio Census 2011

Sex Ratio In West Bengal Is 950 I.E. For Each 1000 Male, Which Is Below National Average Of 940 As Per Census 2011. In 2001, The Sex Ratio Of Female Was 934 Per 1000 Males In West Bengal. Child Sex Ratio In West Bengal Is 956 I.E. For Each 1000 Male,In The Census 2001 The Child Sex Ratio Of India Was 927 Which Declined To 919 In The Census 2011. As Per The Census 2011, Arunachal Pradesh Has The Highest Child Sex Ratio Among The Indian States I.E. 972 While Haryana Has The Lowest Child Sex Ratio I.E.834 Per Thousand Males.

Religious Data In West Bengal Census 2011

The Registrar General And Census Commissioner, India Today Released The Data On Population By Religious Communities Of Census 2011. The Distribution Is Total Population By Six Major Religious Communities Namely, Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain Besides “Other Religions And Persuasions” And “Religion Not Stated”. The Data Are Released By Sex And Residence Up To Sub-Districts And Towns. Total Population In 2011 Is 121.09 Crores ; Hindu 96.63 Crores (79.8%); Muslim 17.22 Crores (14.2%); Christian 2.78 Crores (2.3%); Sikh 2.08 Crores (1.7%); Buddhist 0.84 Crores (0.7%); Jain 0.45 Crores (0.4%), Other Religions & Persuasions (ORP) 0.79 Crores (0.7%) And Religion Not Stated 0.29 Crores (0.2%). Hinduism Is Majority Religion In State Of West Bengal With 70.54 % Followers. Islam Is Second Most Popular Religion In State Of West Bengal With Approximately 27.01 % Following It. In West Bengal State, Christinity Is Followed By 0.72 %, Jainism By 0.07 %, Sikhism By 0.07 % And Buddhism By 0.07 %. Around 1.03 % Stated 'Other Religion', Approximately 0.25 % Stated 'No Particular Religion'.

Rural Population In West Bengal Census 2011

Of The Total Population Of West Bengal State, Around 68.13 Percent Live In The Villages Of Rural Areas. In Actual Numbers, Males And Females Were 31,844,945 And 30,338,168 Respectively. Total Population Of Rural Areas Of West Bengal State Was 62,183,113. The Population Growth Rate Recorded For This Decade (2001-2011) Was 68.13%. In Rural Regions Of West Bengal State, Female Sex Ratio Per 1000 Males Was 953 While Same For The Child (0-6 Age) Was 959 Girls Per 1000 Boys. In West Bengal, 7,820,710 Children (0-6) Live In Rural Areas. Child Population Forms 12.58 Percent Of Total Rural Population. In Rural Areas Of West Bengal, Literacy Rate For Males And Female Stood At 78.44 % And 61.98 %. Average Literacy Rate In West Bengal For Rural Areas Was 72.13 Percent. Total Literates In Rural Areas Were 39,213,779.

Urban Population In West Bengal Census 2011

Out Of Total Population Of West Bengal, 31.87% People Live In Urban Regions. The Total Figure Of Population Living In Urban Areas Is 29,093,002 Of Which 14,964,082 Are Males And While Remaining 14,128,920 Are Females. The Urban Population In The Last 10 Years Has Increased By 31.87 Percent. Sex Ratio In Urban Regions Of West Bengal Was 944 Females Per 1000 Males. For Child (0-6) Sex Ratio The Figure For Urban Region Stood At 947 Girls Per 1000 Boys. Total Children (0-6 Age) Living In Urban Areas Of West Bengal Were 2,760,756. Of Total Population In Urban Region, 9.49 % Were Children (0-6). Average Literacy Rate In West Bengal For Urban Regions Was 84.78 Percent In Which Males Were 88.37% Literate While Female Literacy Stood At 76.01%. Total Literates In Urban Region Of West Bengal Were 22,324,502.

More Facts About West Bengal Census 2011

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Changing Pattern of Urbanization in West Bengal: An Analysis of 2011 Census of India Data

Since 1901, Urban Primacy has been a feature of urbanization of West Bengal and continuous increase of population in highly urbanized districts around Kolkata. This subsequently led to slowing down the process of urbanization from 1951 onwards and quite a different trend has been noticed during 2001-2011. The Census data of 2011 reveals that urbanization process of the state exhibits a growing trend and begins to spread into the interior districts (Maldah, Murshidabad, Nadia, Birbhum and Jalpaiguri) of West Bengal. These have been accompanied by a noticeable decline in the percentage share population share in Class I towns and substantial population growth in small towns. This study makes an attempt to explore this changing pattern of urbanization in West Bengal over the last decade and find out the significance and future of newly developed small towns over the urban landscape. For each of the districts, annual growth rate of urban population (All Towns) during 2001 – 2011 is calculated. Such rate has also been calculated separately considering only those towns which received urban status in 2001 or before i.e. Old Towns. Now the difference between these two rates represents the contribution of towns which emerged in between 2001 - 2011 to the growth of urban population in the districts. To make our understanding more trustworthy, all towns of each district have been classified into three broad groups. Population belonging to each town group has been converted into percentage share to the total urban population. To visualize the spatial spread of urbanization we used ‘kriging’ to interpolate a continuous surface from point samples of district headquarters. Results show for the first time in 2011, a proper decentralization of urbanization could be seen both in terms of spatial context and size class distribution. This may be attributed to the speeding up process of urbanization into the interior districts placed distant from Kolkata featuring with small towns, proclaiming their state of existence by holding significant population share. It could explain the increasing trend of urbanization in the state as a whole in 2011 characterized by the dispersion of dispersed urbanization.

Related Papers

Ashis Sarkar

This paper focuses on the important aspect of the spatial dimension of urbanization in the most significant area which nevertheless bestows with vibrant spirit and soul, i.e. Kolkata Metropolitan Region in West Bengal, Eastern India. Attention initially has paid to the basic pattern of urbanization in West Bengal in broader aspect before turning to an analysis to justify the recent trend of the pattern of demographic changes which is measured by the population density with the help of Geographic Information System through ARC GIS (9.3 version) software that would help to widen the view point of the geographers to establish the fact of decentralization in the study area. To identify and assess the status of demographic surface the System Component Technique has been employed to show the changing nature of it. From the prepared map we have identified the future potential urban pockets which are besieged with reversal growth momentum in the peripheral areas of the core city of Kolkata in the last decade of 2001-2011. Keeping the above concept in the backdrop, it is essential to have an understanding the reason for developing the potential urban pockets for the sustainable management of the existing saturated and decaying urban system.

Journal Space and Culture, India Open access Journal

The present work intends to study the recent processes of urbanisation of West Bengal by measuring some selected indices: like level of urbanisation, decadal growth of urban population, rate of urbanisation, pace of urbanisation and urban growth, contribution of growth in urban population to total growth and rural-urban displacement. It is a meso-level study, and 19 districts of the state have been selected as units of study. Using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), the research has identified three principal factors that determine the processes of urbanisation in the state: rural-urban displacement, decadal growth rate and rate of urbanisation. All these three factors responded positively in both primary and secondary loadings.

DR.BIKRAMJIT SAHA

Proceedings of the 58th ISOCARP World Planning Congress

Tazyeen Alam

Debarshi Guin

Contemporary urbanization in India is in transition and this, along with the continuation of a 'top heavy' urban structure and gradual deindustrialization, is characterized by faster growth of informal employment, a declining trend of urban-ward migration of males, the slow down in the growth of cities and towns and the emergence of new urban centres. Given this immediate backdrop, this paper examines the contemporary processes and emerging forms of urban transition in West Bengal, with its longstanding history of 'mono-centric' urbanization. It reveals that urbanization in the state is no longer confined to a few pockets, as many new urban centres have emerged away from them and small towns are growing at relatively faster rates compared to the cities. But the underlying factors of this transition are not associated with the dispersal of economic activities and employment opportunities away from the metropolises. Furthermore, the study is sceptical about the significance of this emerging form of urbanization fuelled by the growth of small cities and towns which have a weak economic base, a crisis of urban governance and inadequate access to basic amenities.

Deb Prakash Pahari

Dr. Suresh Chitragar

Urbanization is the process which transforms rural areas into urban areas as agricultural pursuits common to villages change into non-agricultural and corresponding change of behavioural patterns also take place. This process is predominantly associated with industrialization and economic growth which is eventually allied with urban development. It creates several job opportunities in the urban area and plays a significant role in declining poverty and unemployment. Belgaum, one of the largely populated districts of northern Karnataka and having a slow growth rate of urban population has been selected as the study area. The present paper attempts to understand the process of urbanization, its volume, trend, pattern, cause and consequences based on census data during 1901-2011. The study shows both spatio-temporal variations in the decadal and spatial pattern of growth and distribution of total and urban population, outline of urbanization in light of growth of urban settlements by s...

Joy Karmakar

The paper investigates the spatial and temporal growth pattern of the census towns. This is a rural area and not recognized as town by the state. Secondly to find out that census towns are product of agglomeration economies across all districts of west Bengal. Thirdly to investigate the spatial inequality of access to the basic services of this spatially transformed area and make a comparison with statutory urban area of the state. West Bengal is one of the most urbanized states of India. According to the 2011 census West Bengal has 31.87 percent of urban population and it was 27.48 percent in 1991. Therefore more than 4 percent increase of urban population within two decades. Growth of census town from 1981 to 2011 is 16.43 percent. It is apparent from the study that census town close the KMA (Kolkata Metropolitan Area) have greater accessibility of service. While in case of backward districts urban services are poor in both census and statutory town. Key word: Census Towns, Kolkata Metropolitan Area, Agglomeration, spatial inequality.

Mahalaya Chatterjee

Urbanization in India is currently characterized by two basic trends: lopsided migration to the larger cities and unbalanced regional economic development. In this context, this paper tries to find out the trend and pattern of urban Centres (municipality, Municipal Corporation etc.) of West Bengal. To know how the districts are consistent in terms of level of urbanization and with other aspect of urbanization. Lastly assess the policies for small and medium towns over the year regarding the balance regional economic development. Census data has been used for analyze the trend and pattern of urban centers of West Bengal. It is apparent that since the independence Kolkata have remained the largest urban centers in West Bengal as well as the eastern India. There was no single million size city till 2001 in the state. Even the second million size city (Howrah) of the state next to Kolkata emerged not outside the Kolkata Metropolitan area. District headquarters, planned towns and other small towns of the state perform in different way over the years. Policy intervention has played a crucial role in shaping the pattern of urbanization in the state. There was no uniform policy of urbanization rather Policy has been shaped and reshaped by the different political periods.

RELATED PAPERS

Paediatric Respiratory Reviews

Petr Pohunek

Nanomedicine : nanotechnology, biology, and medicine

Antonio De Grazia

Le Journal de Physique IV

C Suryanarayana

Ryan KAMMARTI

PLoS neglected tropical diseases

Manikkavasagan Ilangopathy

Química Nova

Débora Maria Moreno Luzia

Breast Cancer Research

Rhonda Hattar

American Journal of Pharmacology and Toxicology

Yazun B. Jarrar

Marco Ilardi

Journal of Values-Based Leadership

Sulee Tongvichean

International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies

Shakil Ahamed

Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica

Ramiro Gasca

Journal of Contemporary China

Guangyu (Karin) Qiao-Franco

Sunita Shrivastav

Revista Electrónica Educare

Kattia Salas Perez

Herpetological Conservation and Biology

Charles Martin

International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management

Archives of Microbiology

Dietmar Pieper

Pediatric blood & cancer

Manraj Heran

European Journal of Public Health

Emilie Friberg

Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology

Nefer Fallico

Jurnal Penelitian dan Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat UNSIQ

Fajar Husen

Chalotte Glintborg

Sports Medicine - Open

Psychotherapie-Wissenschaft

Peter Schulthess

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

General Report, Part I-A, Series-22, West Bengal - Census 1971

India , 1977.

- Document Description

Description

Authoring information, disclaimer and copyrights, themes and topics.

West Bengal Population | Sex Ratio | Literacy

West bengal sex ratio 2024.

Sex Ratio in West Bengal is 950 i.e. for each 1000 male, which is below national average of 940 as per latest census. In 2001, the sex ratio of female was 934 per 1000 males in West Bengal.

West Bengal Literacy Rate 2024

Literacy rate in West Bengal has seen upward trend and is 76.26 percent as per latest population census. Of that, male literacy stands at 81.69 percent while female literacy is at 70.54 percent.

West Bengal 2023 - 2024 Population

West bengal religion wise population 2024.

Hinduism is majority religion in state of West Bengal with 70.54 % followers. Islam is second most popular religion in state of West Bengal with approximately 27.01 % following it. In West Bengal state, Christinity is followed by 0.72 %, Jainism by 0.07 %, Sikhism by 0.07 % and Buddhism by 0.07 %. Around 1.03 % stated 'Other Religion', approximately 0.25 % stated 'No Particular Religion'.

West Bengal Population Data

West bengal urban population.

Out of total population of West Bengal, 31.87% people live in urban regions. The urban population of West Bengal increased by 29.72 percent during 2001-2011 period and is expected to rise further. Sex Ratio in urban regions of West Bengal was 944 females per 1000 males. Average Literacy rate in West Bengal for Urban regions was 84.78 percent.

West Bengal Rural Population

Of the total population of West Bengal state, around 68.13 percent live in the villages of rural areas. The population growth rate in West Bengal for rural populatation recorded for this decade (2001-2011) was 7.68%. In rural regions of West Bengal state, female sex ratio per 1000 males was 953. Average literacy rate in West Bengal for rural areas was 72.13 percent.

West Bengal City List

West bengal metropolitan regions, west bengal state information, what is the current population of west bengal, what is the literacy rate of west bengal, what is the sex ratio of west bengal.

Role of transport infrastructure in birth of census towns in West Bengal

- Published: 07 January 2022

- Volume 6 , pages 593–616, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Saumyabrata Chakrabarti 1 &

- Vivekananda Mukherjee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8696-8669 2 , 3

2745 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

In the Indian Census, the growth of villages into small towns (called Census Towns, CT) accounted for almost 30% of urbanization during 2001–11, which was significantly higher than the preceding decades. This paper evaluates the role of the transportation infrastructure in this phenomenon by using data from the State of West Bengal, which has experienced the birth of the largest number of such towns. We use the probit regression method involving binary dependent variables. The results show that the existence of state/national highways in the neighborhood increase the probability of a village, designated as a ‘would be CT’ in the 2001 Census, to be converted into a CT in the 2011 Census. The closer the location of the highway, the more intensive the positive effect. The rail infrastructure does not play a significant role in this process. Interestingly, the paper shows although the density of local road networks generally complements highways in the formation of cities, the complementarity relationship is the opposite in the districts bordering Kolkata. The role of the Golden Quadrangle (GQ) project, highway construction project undertaken in India during this time to connect the four major metropolitan cities of India, had a limited impact compared to national/state highways in the birth of CTs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Subaltern Urbanization: The Birth of Census Towns in West Bengal

Examining the relationship between socioeconomic structure and urban transport network efficiency: a circuity and spatial statistics based approach

Elif Su Karaaslan & K. Mert Cubukcu

Analyzing impacts of Vietnam’s North–South highway on creation of regional cluster

Euijune Kim, Min Jiang & Byula Kim

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

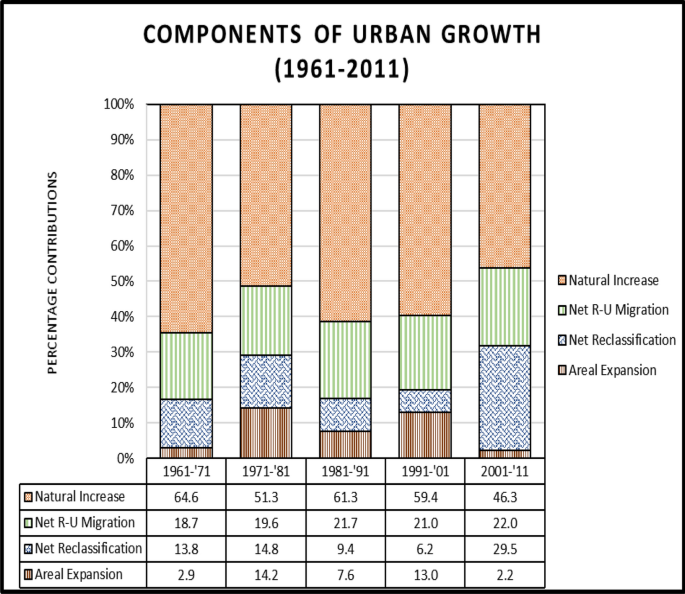

'Around the world the process of urbanization is relentless and remarkable since 1990 as the urban dwelling has increased from a yearly average of 57 million between 1990 and 2000 to yearly 77 million between 2010 and 2015’ (World Cities Report 2016 ). In 1990, 43% (2.3 billion) of world’s population lived in urban areas; by 2015, this has grown to 54% (4 billion). However, the increase in urban population is not evenly spread across the regions of the world. While no region in the world can report a decrease in urbanization, the highest growth rate between 1995 and 2015 was clearly in the least developed part in the world with Africa being most rapidly urbanizing. There has been emergence of large cities and megacities, particularly in the low and middle-income regions in the world. In 1995, there were 22 large cities and 14 megacities in the world; by 2015, both categories of cities had doubled, as there were 44 large cities and 29 megacities with most megacities located in developing countries. But, the fastest growing urban centers had not really been the large cities and megacities; they were small and medium cities which account for 59 percent of world’s urban population (World Cities Report 2016 ). India has also shown similar trend. India’s pattern of urbanization inherited from the colonial period was biased towards large cities. But it has been showing a reverse trend in the decade spanning from 2001 to 2011 owing to the growth of small- or medium-sized towns called ‘Census Towns’ (CT). These towns, which actually are reclassified from the villages by fulfilling the criteria that they have (1) a population of 5000 or more, (2) population density of at least 400 per square kilometer, (3) 75% of its male main workforce working in non-farm sector, and (4) administered by rural local governments, show an unprecedented numerical increase during the period 2001–2011. In fact, they contribute to almost 30% of total urbanization in India during the said period that shows up in the figure below, the data for which are procured from the Census report of various years published by Government of India (Fig. 1 ).

Understanding this pattern of urbanization is important, especially when it is generally believed that South Asian and Sub-Saharan African countries lag in terms their extent of urbanization. Footnote 1

Between 2001 and 2011 the pattern of urbanization in different states of India has not been the same. Mathur et al ( 2021 ) through their analysis of migration tables provided by the Census (2011) show that while in states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh the urbanization was dominated by natural increase in population. in states like Maharashtra and Gujarat it was mainly by rural–urban migration. In states like West Bengal and Kerala, the CT growth was the dominant form of urbanization. All the above-mentioned factors were balanced in the case of states like Haryana and Andhra Pradesh. The motivation of studying the case of West Bengal in the present paper follows from the fact that it had the highest absolute number of new CTs born among all Indian states in this period. Table 1 , using Census (2011), records the absolute number of new CTs for all the states in India between 2001 and 2011. The number of new CTs that was born in West Bengal had been 526, which was the highest in India. Footnote 2

The existing literature in economics, which has been reviewed below, studies the phenomenon of growth of the CTs. However, the role of transport infrastructure in the growth of CTs has not received adequate attention. This paper undertakes this study in detail and derives insightful results by using the data from West Bengal.

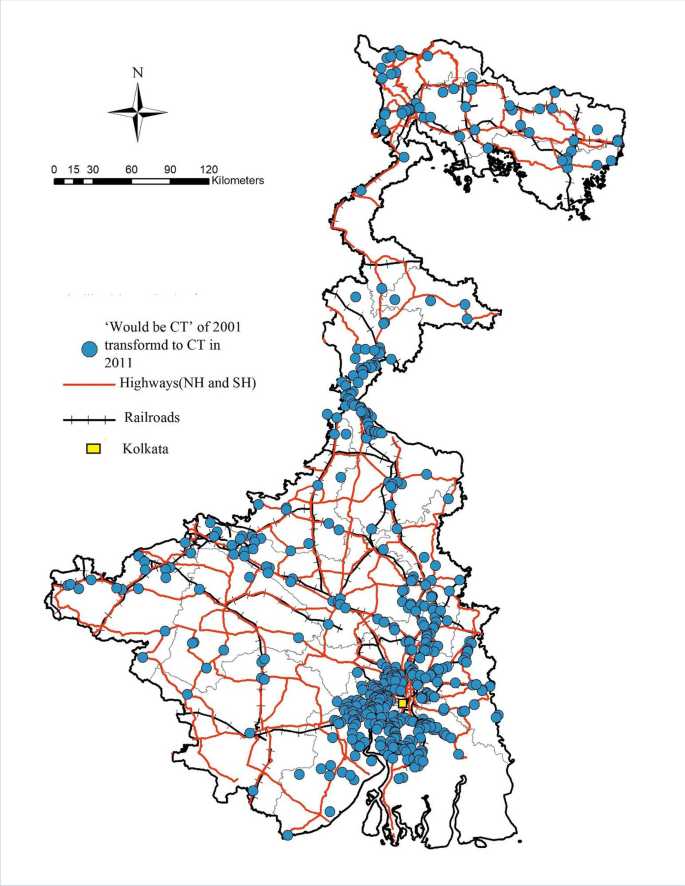

West Bengal is a state located in Eastern part of India sharing its international border with Bangladesh. It also shares its border with Indian states of Odisha, Jharkhand, Bihar, Sikkim and Assam. Kolkata is the capital of the state, which is also the third largest city of India. According to Census (2011) it is the fourth most populous state of India with a population of 91,347,736. Around 4.92% of the population lives in Kolkata. In terms of area it is the 13th largest state in India with an area of 88,752 km 2 . In 2011 it was divided into 19 districts including Kolkata, 16% of which were more than 50% urbanized. The spatial distribution of the new CTs in the state according to Census (2011) is shown in the map of West Bengal below.

There were 659 villages from 18 districts (excluding Kolkata) considered as ‘would be CTs’ in Census (2001) as they were likely to fulfil all the criteria of a CT in the next census. Eighty percent of these villages were transformed into CTs in Census (2011). The emergence of these CTs does not rest much on population growth as most of them already achieved a population size of 5000 in Census (2001). This paper mainly shows how the economic forces working through transport infrastructure helped them to grow their non-agricultural sector employment such that they could become CTs. Figure 2 shows that 46% of these new CTs were born in the districts of North and South 24 Parganas and Haora, which share their border with Kolkata. We provide a list of the villages termed as ‘would be CTs’ in the sampled districts in Census (2001), mentioning which of them transformed in CTs in Census (2011) and which of them maintained status quo. The list appears as supplementary material to the paper. The list shows concentration of CTs also in some districts like Hugli, Nadia, Maldah, Murshidabad, Barddahman, Jalpaiguri and Darjiling away from Kolkata. There are 16 National Highways of length 3565 km. pass through West Bengal. Only four of them connects the city of Kolkata. Similarly, there are 15 state highways of length 4505 km Footnote 3 , which are spread across the state with no direct connection to the city of Kolkata. The length of railways in West Bengal in 2011 was 3937 km. Footnote 4 The local roads are, however, not shown in the map. The paper investigates whether the existence state/national highways and railways in the neighborhood increases the likelihood that a village, which was designated as a ‘would be CT’ in Census (2001), is converted into a CT in Census (2011). It also studies the role the density of local roads play in the process.

Source: Census of India (1971,1981,1991, 2001 and 2011)

Components of Urban Growth in India (1961–2011).

The spatial distribution of CTs in Census 2011 that had been classified as ‘would be CTs’ in Census 2001

The pioneering paper by Krugman ( 1991 ) on economic geography argues that lowering of transport cost accelerates the centripetal forces that attracts both labor and capital to the city. However, Helpman ( 1998 ) points out that the rising cost of non-tradable commodities in the city like price of housing, clean environment, congestion-free traffic can disperse the centripetal forces mentioned by Krugman ( 1991 ) and if transport cost is very high, an existing agglomeration grows in its population size. While in the former, a lower transport cost due to improved infrastructure promotes growth of an existing agglomeration with higher welfare of its residents at the cost of the smaller agglomerations at its neighborhood, in the latter, a smaller agglomeration grows in terms of population with falling welfare level of its existing residents. Chandra and Thompson (2000) in the context of US show that the highways built between 1969 and 1993 raised the income of the rural counties through which they pass and reduced the income of the adjacent counties. Baum-Snow et al. ( 2020 ) in a recent paper show with Chinese data that investing in local transport infrastructure to promote the growth of hinterland often has a self-defeating impact of losing economic activities and specialization in agriculture in those areas.

In Indian context, Aggarwal ( 2018 ) takes a village-centric view and shows that expansion of rural roads and transport infrastructure results in greater market integration, reduced price of non-local goods, and wider variety of consumption basket in rural areas. It also leads to greater participation of local teenagers in the expanded labor market. Mukhopadhyay etal. (2016) with an investigation in certain CTs in northern India show that increased connectivity and growing rural income are the main driving forces for the growth of small-scale non-tradable services which are the main sources of non-farm employment in these settlements. Van Dujine and Nijman ( 2019 ), based on their fieldwork in West Bengal and Bihar, show that a sizable portion of urban growth has gone unrecorded in official statistics due to technical reasons. There are cases where the boundaries of existing agglomerations could be redefined as a new urban settlement. However, they also notice that in these states there has been a shift in the employment structure away from agriculture causing in situ urbanization in a dispersed manner. They identify the absence sufficient employment opportunities in existing urban settlements or major cities as one of the reasons behind this dispersed pattern of urbanization. Mathur et al. ( 2021 ) also confirm this trend by use of National Accounts Statistics, National Sample Survey and Annual Survey of Industries data made available by Government of India. However, none of these papers discuss the role of transport infrastructure in birth of the new CTs as we do in the present paper.

Ghani et al. ( 2012 ) found that district level infrastructure is partly facilitating the relocation of organized manufacturing to rural locations while the unorganized manufacturing is migrating to urban locations. Such movement seems to be partially explained by the development of national level highways, especially the construction of Golden Quadrangle, a highway project undertaken by Government of India that was implemented in the study period. However, there is a very limited impact of Golden Quadrangle on unorganized manufacturing outside the nodal districts where the more than one highways meet. Sharma ( 2013 ) claims that commuting to the nearest city is an important reason for observed expansion of non-farm employment in the villages. Balakrishnan ( 2013 ) with two examples of Bangalore–Mysore highway and Pune–Nasik highway demonstrates that the urbanization along highways has been the emerging pattern of urbanization in developing countries. Based on NSSO 55th round(1999–2000) 66th round (2009–2010), and 68th round(2011–2012) data, Mahajan and Nagraj ( 2017 ) argue that the road construction projects undertaken in India during 2000–2012, both highways and rural roads expanded rural construction demand and employment.

Our paper contributes to the literature in a number of ways. First, it analyzes both the forces of agglomeration and dispersion that work because of development of transport infrastructure like highways, rail head and local roads. It looks at interaction of each of the highways and rail infrastructure with local roads. In the analysis it not only juxtaposes the transport infrastructure variables, also controls for nearness to the city and local amenities at the villages. Second, it finds that the state and national highways located near the city increases the probability of a village turning into a CT. The closer the distance, the higher is the chance of a successful conversion. Contrary to the existing literature, for West Bengal, the paper finds that the local roads have insignificant but positive impact in emergence of CTs. Its role assumes significance, where it complements the highways. However, the nature of complementarity is different at the districts bordering the city of Kolkata compared to what we generally observe in the state. While generally it supports the forces of dispersion from the existing cities, in the neighborhood of Kolkata it supports the forces of agglomeration. Third, the GQ project in West Bengal has a weaker role compared to the state/national highways in turning the prospective villages into CTs. Fourth, commuting in general is not an important factor in formation of CTs in West Bengal. Fifth, in case of West Bengal, with its uneven pattern of development centered around its capital city of Kolkata, all other things remaining the same, the villages had a higher chance of getting converted in a CT in the districts bordering Kolkata. The results are new in the literature and important for policy making.

The plan of the paper is as follows: The next section discusses the theoretical possibilities of conversion of a village into a CT due to improvement of transport connectivity and due to increased amenities at the villages. Section 3 describes the empirical strategy of the paper with data, estimation procedure and the results discussed in different subsections. Section 4 concludes.

2 The theoretical possibilities

In this section we describe the theoretical possibilities through which the development of transport infrastructure and non-traded service sector could influence conversion of the villages in West Bengal into CTs by helping them to satisfy the population criteria that are required for the purpose of reclassification.

2.1 Improvement of transport infrastructure

In West Bengal the improvement of transport infrastructure at a village can occur in three different ways as follows: (1) development of a highway that connects cities may pass through vicinity of the village; (2) improvement of rail-connectivity of the village to the cities; (iii) improvement of local road network near the village.

We will discuss the theoretical implications of each of them below.

Development of a highway in the neighborhood of a village:

The development of a highway would lower the transport cost between the village and the nearest city. The theory proposed by papers like Janelle ( 1968 ), Krugman ( 1991 ) suggest that this would trigger the forces of agglomeration to attract labor and capital from the village to the city. Therefore, the chance of the village getting converted in a CT diminishes as it loses both its population and non-farm production units to the city. The non-farm products are carried from the city to the village, which now specializes in farm production, at a lower price. However, in a framework of continuum of cities and villages along a highway, Rossi-Hansberg ( 2005 ) argues, it is perfectly possible that in response to the lower transport costs the industry disperses geographically and new CTs develop specializing in production of intermediate goods, which is a view opposite of Krugman ( 1991 ) as he argued that both the final good production and the intermediate good production would agglomerate in the existing city. Helpman ( 1998 ) also opposes Krugman ( 1991 ) view by pointing out that from lowering of the transport cost a force of dispersion would come into play to disperse the non-farm activities and labor force to the neighboring villages. This happens because of rise in prices of non-tradables like housing, clean-environment, congestion-free traffic, etc. in the existing big cities. The force of dispersion increases the chance of a village, neighboring a city transforming into a CT. The closer is the village to the city, it seems that following the idea of gravity in trade (Head and Mayer 2014), it has a better chance of getting converted in a CT. Footnote 5 The ‘nearness’ of the city also increases the possibility that labors commute daily from the village to the city for their work rather than staying put at the city.

Improvement of rail-connectivity to the cities:

The consequences of rail connectivity are expected to be similar to the consequences of development of highways as described above, except for the crucial difference that exists between two alternative modes of transport, the rail and the road. The rail connectivity involves higher fixed cost and lower marginal cost both for transportation of passenger and freight as the one has to approach the nearest railway station to avail the rail facility (Brueckner 2011 ). However, the road transport facility comes at doorstep at a higher marginal cost. Therefore, for a shorter distance the road transport seems to be a better option for transportation and for a longer distance, it is the railway. Therefore, the agglomeration and the gravity-like forces discussed above are likely to be triggered more with railway connectivity if the existing city is located at a longer distance. As the nearness to the city increases, the highway connectivity seems to matter more.

Improvement of local road network:

The local road network may act as a complement either to the highway connectivity or to the rail connectivity in the situation where the highway does not pass exactly through the village or the rail station is not exactly located at the village. In such situations, connectivity to the highway or the rail station from the village may play a role in aggravating the forces of agglomeration at the city. However, the forces of dispersion from the large city can also work in the opposite direction converting a village to a CT. Since a large village has asymmetric distribution of population with adjoining villages, as the local road-network improves, the forces of agglomeration may work in the same way as described by Krugman ( 1991 ), perhaps at a smaller scale, between the adjoining small villages and the large village, which helps conversion of an already large village into a CT by attracting non-farm activity into it.

2.2 Development of non-tradable service sector

Development of non-tradable services like availability of electricity services, banks and financial services, education services like schools and colleges, etc. offers a better quality of life to village residents, creates more non-farm jobs and may attract more population in it. However, there exists a ‘chicken and egg’ problem in this process, because we are not sure whether a large population attracts better services or better services attract larger population. Although the causality cannot be ascertained, they are expected to be positively correlated with each other.

For finding out whether connectivity to city/local connectivity explains the formation of CTs, we use the available data to run the following regression specification:

\({y}_{ij}=\alpha +\beta {T}_{ij}+{x}_{ij}+ \varphi {KOL}_{ik}+{D}_{j}+{u}_{ij}\) ,where the dependent variable \({y}_{ij}\) is a binary variable that represents the CT status of the \(i\) th village in the \(j\) th district. For a CT, it takes a value of 1. Otherwise, it takes a value of 0. \({T}_{ij}\) represents the set of explanatory variables related to transport infrastructure, i.e. connectivity to city/local connectivity of village \(i\) , which are the main variables of interest of the present study. \({x}_{ij}\) represents the set of variables that indicate the development of non-tradable service sector at the \(i\) th village in the \(j\) th district. The district specific fixed factors of district \(j\) , which are shared by all the villages located in district \(j\) , are captured through the dummy variable \({D}_{j}\) . For checking whether proximity of Kolkata, because of uneven development of West Bengal centering around its capital city, increases the probability of a village converted to a CT, we introduce another dummy variable \({KOL}_{ik}\) . It takes value of 1, if a village \(i\) belongs to a district \(k\) bordering the district of Kolkata. For all other villages it takes value of zero. Footnote 6 The unobserved village specific factors are captured through \({u}_{ij}\) , which we assumed to be independently identically distributed across the villages.

In accordance with the theory, the set of variables included in \({T}_{ij}\) are the following:

HIGHWAY 5: A dummy variable that takes value of 1, if a highway passes through a neighborhood of 5 km radius around the center of village \(i\) in district \(j\) ;

RAIL 5: A dummy variable that takes value of 1, if there is at least one railway station within 5-km radius neighborhood around the center of village \(i\) in district \(j\) ;

NEARNESS: Reciprocal of the nearest city/ST Footnote 7 distance from the center of village \(i\) in district \(j\) ;

ROAD: The length of rural roads per 1000 square km. area in district \(j\) . We assume uniform distribution of rural roads across all villages of the district;

For robustness check, we replace HIGHWAY 5 and RAIL 5, with HIGHWAY 10 and RAIL 10 which are defined accordingly. Since the construction of the Golden Quadrilateral (GQ) changed the transport infrastructure in India during the study period, we also use a variable GQ, defined as a dummy variable that takes value of 1, if the GQ passes through the a neighborhood of 10 km radius around the center of village \(i\) in district \(j\) . We also consider interaction between the variables like (HIGHWAY 5*NEARNESS), (RAIL 5*NEARNESS), (HIGHWAY 5*ROAD) for our purpose.

In the regression equation, the location of highways/railways is exogenous to the villages as they are constructed to connect the cities and it is coincidence that a highway/railway passes through the neighborhood of a village. The same is not applicable for local roads. However, we proxy this variable with district level density of local roads to make it exogenous to a village. The theory described earlier does not predict a definite sign for coefficients of HIGHWAY 5, RAIL 5. The negative significant sign of these variables suggest that the agglomeration effect of lower transport cost dominates its dispersion effect to attract labor and production units to city/ST, reducing the chance of a village to turn into a CT. The positive significant sign suggests the opposite. A positive significant sign of ROAD would imply local agglomeration forces around the village dominate the agglomeration of the city/ST. Nearness of the city/ST would strengthen the force of agglomeration/dispersion originated at the city/ST. The lowering of the transport cost along with nearness would reinforce these forces. However, compared to RAIL 5, the effect of HIGHWAY 5 is expected to be more prominent if nearness to the city/ST increases.

The set of explanatory variables included in \({x}_{ij}\) are as follows:

BANK: A dummy variable that takes value of 1, if at least one branch of a commercial bank is present in village \(i\) at district \(j\) ;

POWER: Represents percentage of electrified villages in district \(j\) , where village \(i\) is located. This indicates the probability of availability of power in village \(i\) in district \(j\) .

Since these variables are likely to be correlated with other factors, which we have not controlled for, the regression analysis does not establish any causality with respect to these variables. However, as the improved amenities at the villages strengthen village-centric agglomeration effect, both these variables are expected to have positive regression coefficients.

Because of uneven development of West Bengal centering around its capital city of Kolkata, all other things remaining the same, the location of a village in a district bordering Kolkata may benefit the forces of agglomeration of the metropolitan city to get converted to a CT. Therefore, the coefficient of the \({KOL}_{ik}\) dummy in the regression equation is expected to have a positive sign.

3.1 Data and estimation procedure

The data used for the empirical study are taken from CTs/Villages Directory of West Bengal for2001 and 2011 extracted from Census of India (2001 and 2011) and also from State Statistical Handbook of West Bengal various years. Table 2 below describes the data.

Table 2 shows that 80% of the villages which were ‘would be’ census town in 2001 got converted into CT in 2011. Among the transport cost-related explanatory variables of this change, HIGHWAY5 has mean of 0.78 implying that in 2007–2008, a highway passed through 5 km neighborhood of 78 percent of the villages considered in this study. Notice that HIGHWAY10 has mean of 0.92, which implies that if 10 km radius is considered, around the same time, 92% of villages had a highway in their neighborhood. The highway can either be a national highway or a state highway. The highways constructed under the Golden Quadrangle (GQ) project by the middle of the decade, passed through the 10-km radius of only 9% of the sampled villages. The data shows that around 2007–08, 38 percent of the villages had a railway station within 5 km radius. As the radius was extended to 10 km, 57 percent villages had a rail station within it. For the NEARNESS variable, for the sampled villages the mean is 0.11, with maximum of 2 and minimum of 0.01. Notice that, as the distance of a village from the nearest city/ST increases, the value of NEARNESS variable falls. In the case of the variable ROAD, the village level data were unavailable. Therefore, we have proxied it with the data on the roads maintained by the local administrative bodies like Gram Panchayats, Panchayat Samitis and Zilla Parishads aggregated at the district level. The data have been normalized per 1000 km 2 area of the district. The average length of local roads per 1000 km 2 in the districts of West Bengal by 2007–08 was 11.46 km with a minimum of 3.09 km in the district of Darjeeling and maximum of 30.77 km in the district of South 24 Parganas. The assumption, here, is that the road allocation is uniformly distributed among all villages in a district.

For the non-tradable service sector related explanatory variables, it turned out that by 2007–08, the time when the Census operation took place, 50% of villages included in our study had at least one commercial bank branch located at the village. Since we do not have electrification data at the village level, we have proxied it by the district level data. On average, 93.70% of villages were electrified across all districts in West Bengal in 2001 with minimum of 53 percent and maximum of 100%. We interpret this data as probability that a village in a particular district receives the electricity service. Since, by 2007–08 almost all the villages received electricity services, the 2001 data also may be considered as indicator of average quality of electricity services in the villages as the newly connected villages experience unstable services in the initial years of connectivity.

There are three districts in West Bengal that share their border with the district of Kolkata. They are Haora, North and South 24 Parganas. Of the 659 villages in our sample, 46% belonged to these districts.

We use probit regression as the dependent variable is of binary nature, taking the value 1, if a village identified as ‘would be CT’ in Census (2001) gets converted to a CT in Census (2011). Let P i be the probability at which a village is converted to a CT. We allow the corresponding probability distribution to be associated with a cumulative normal distribution, Y = \(\phi (x\beta + u) \in (0,1)\) so that \(x\beta + u\) = \(\phi^{ - 1} (Y)\) . Notice,

\(Y^{\prime} = x\beta + u\) .

Since the dependent variable takes the value 0 and 1, we assume \(Y^{\prime}\) takes the value 0 and 1. The above function \(Y^{\prime} = x\beta + u\) is called the probit function whose parameters are to be estimated.

In our regression strategy, first, we regress the dependent variable with respect to the ‘connectivity to city/local connectivity’ variables and then with the ‘non-tradable sector’ variables like BANK and POWER. In the final specification, both types of explanatory variables are combined. In each specification we run two versions, one with district specific fixed effect (DSFE) and the other, without district specific fixed effect. The \({KOL}_{ik}\) dummy is included in every specification. In each specification, robust standard error has been calculated to control for possible heteroscedasticity.

In regression set 1, in the connectivity variables we consider only the highway and the rail connectivity within 5 km radius, the local road network and their interactions. We also control for the role of NEARNESS. Since some parts of existing national highways are also part of the GQ project, the HIGHWAY and GQ variables show strong correlation with each other. Therefore, we run a separate set of regressions (regression set 2) exclusively with GQ as connectivity variable, which evaluates the role of GQ in converting the villages into CT. Regression set 3 reruns regression set 2 described above, considering 10 km radius for the highway/rail connectivity variables instead of 5 km radius considered earlier. This is done for robustness check. We also calculate the marginal effects for each set of regressions.

3.2 Results

The results of the first set of regression are presented in the Table 3 below.

For the first set, notice that the coefficient of variable HIGHWAY 5 is positive and significant at 1% level in all the specifications, where it is included. It means that the presence of a highway within 5 km radius of a village, declared as a ‘would be CT’ in Census, 2001, increases its chance of turning into a CT in Census, 2011. Going by the theory, this implies that in our case the forces of dispersion as anticipated by Helpman ( 1998 ), Rossi-Hansberg ( 2005 ) acting through HIGHWAY 5, had been more dominant than the centripetal forces towards the city as proposed by Krugman ( 1991 ). However, the presence of a rail station within 5 km radius turns out to have an opposite but insignificant effect. Notice that as the distance of a village from the nearest city/ST increases, the value of NEARNESS variable falls. The negative sign of coefficient of NEARNESS in Table 3 and its interaction with HIGHWAY 5 indicate the negative effect of NEARNESS on conversion of a village into a CT. The negative sign shows that the centripetal force of agglomeration towards the city as suggested by Head and Mayer (2014) counters the dispersion force of enhanced possibility of commuting to the city through the highway, while staying put at the village. However, both these coefficients turn out to be insignificant. The interaction term between RAIL5 and NEARNESS has also negative and insignificant coefficient. The density of local roads has a positive effect on conversion of a ‘would be CT’ to a CT, showing the existence of the dispersion force from the nearest ST/city and the local forces of agglomeration at work. But, the effect is not significant. Interestingly, the interaction of ROAD with HIGHWAY 5 has positive significant coefficient at 5% level. This implies that the existence of the dense network of local roads complements the positive role played by a highway in the formation of a CT, which is expected. The existence of local amenities like BANK and POWER is significantly associated with formation of CTs. Footnote 8 The agglomeration force of Kolkata has a positive impact in formation of CTs in bordering districts, but at an insignificant level.

The second set of regressions replaces HIGHWAY5 and RAIL5 with GQ and run similar specifications as in set 1. The results of the second set of regression are presented in the Table 4 below.

The results show that the construction of highways under the Golden Quadrangle project had a positive impact on the ‘would be CT’ villages located in the neighborhood to get converted into a CT. However, the effect is significant only at 10% level. Notice from Table 2 that only 9 percent of the sampled villages in our study had GQ highways in their 10 km neighborhood, which explains the weak explanatory power of GQ in formation of CTs. Interestingly, in the case of GQ, it appears that neither its interaction with NEARNESS nor ROAD are significant in explaining the formation of CTs. The other results are similar to the one, we found in set 2 regressions, except the fact that the local amenities now has insignificant impact on formation of CTs.

The third set of regressions replaces HIGHWAY5 and RAIL5 with HIGHWAY10 and RAIL10 and run similar specifications as in set 1. This checks the robustness of the results we found in set 1 regressions. The results of the third set of regression are presented in Table 5 .

The results are qualitatively similar to the set 1 results. The only difference is that the coefficients of HIGHWAY10 are smaller than the coefficients of HIGHWAY5. Although Table 2 suggests that the greater radius of 10 km places almost 92 percent of the ‘would be CT’ villages in the neighborhood of a highway, which is a significant jump over 78 percent in the case of 5 km radius, the effect of highway as a dispersion force becomes weaker with the increased distance from a village.

Tables 6 , 7 and 8 calculate the marginal effects corresponding to set 1, 2 and 3 regressions, respectively.

These tables show that while the location of a highway within 5 km radius of a ‘would be CT’ village increases its chance of being converted into a CT by 39%, its location within 10 km radius of a such a village reduces the chance of the village being converted into a CT by 4%. In contrast, the location of GQ within 10 km of such a ‘would be CT’ village increases its chance of being converted into a CT only by 19%. Location of at least one branch of a commercial bank in such a village increases its probability of getting converted into a CT by 30–33%. The corresponding number for 1 percent rise in chance of electrification is estimated at 13–34%. The location of a village in the bordering districts of Kolkata raises its chance of being converted to a CT by 4%–6%.

Because of uneven development of West Bengal centering around its capital city of Kolkata, we also check whether the generalized conclusions drawn above holds for transformation to CTs of the villages located at the districts bordering Kolkata too. There are 295 such villages in our sample, as reported in Table 2 , which is 46% of our entire sample of villages. Table 9 below shows the results of the regression when HIGHWAY 5 is included as the transport infrastructure variable.

The results are similar to the reported results of Table 3 above, with a major difference. For the villages located in the three districts bordering Kolkata the sign of the interaction term between HIGHWAY5 and ROAD has changed its sign from positive to negative and the effect is significant. The result implies that the local roads, although still plays a positive role in transforming villages into CTs, for the villages in these districts which are located within 5 km. radius of a state/national highway, strengthens the forces of agglomeration towards the nearest ST/city rather than strengthening the forces of dispersion as in the previous case. The results with other transport infrastructure variables like GQ and HIGHWAY10 are similar in spirit and are not reported here.

4 Conclusions

A dispersed pattern of urbanization in the form of sub-urbanization, peri-urbanization or urban sprawl has been a significant trend in different parts of the World over the past two decades. Accommodating highways and automobile expansion with enhanced ease of mobility due to improved commuting technologies is suspected to be the one of the reasons behind it (World Cities Report 2016 ). However, apart from the highways, the transport infrastructure also includes alternatives like railways and local roads. This paper, in the context of growth of Census Towns in India during 2001–2010 period, juxtaposes these alternative forms of transport infrastructure in a statistical framework and evaluates their role in conversion of the villages, which was recorded as a ‘would be Census Town’ in Census, 2001, into a Census Town in Census, 2011. It uses the data from the state of West Bengal, which saw the birth of the highest number of Census Towns, for its purpose. The criteria for declaration of a village into a Census Town in India suggest that the agglomeration at the local level should trigger the process of conversion. However, the existing economic theory does not definitely answer which type of transport infrastructure acts as a trigger. The paper finds some suggestive empirical results regarding this. It finds that in West Bengal the existence state/national highways in the neighborhood increases the probability of a village, designated as a ‘would be Census Town’, being converted in a Census Town. It appears that the highways promote the dispersion of non-farm economic activities from existing cities to the newly formed CTs due to the factors like growing congestion, pollution and higher housing prices at the cities. The closer the location of the highway, the more intensive is the force of dispersion. The rail infrastructure did not play a significant role in the process. Interestingly, the paper finds that the density of local road network in a district in general complements the forces of dispersion due to highways converting ‘would be CTs’ in CTs, except in the districts bordering the capital city of West Bengal, Kolkata. Due to uneven development of urban system in West Bengal surrounding the city of Kolkata, in these districts, the local roads in fact oppose the dispersing influence of the highways in formation of CTs, decelerating the concentration of non-farm activities at the ‘would be CTs’. As the paper evaluates the role of Golden Quadrangle (GQ) project, the highway construction project undertaken in India during the study period of 2001–2011 to connect the four major metropolitan cities of India, it finds that it had a limited impact compared to national/state highways in birth of the Census Towns. The paper also finds a positive association between amenities available at the village in its conversion to a Census Town.

The results are new in the literature and important for policy making. As Baum-Snow et al. ( 2020 ) mentions, since about 20% of World Bank’s lending supports development of transport infrastructure, more than that for poverty alleviation programs, it is important to know the expected impact of alternative infrastructure-projects like development of the existing state/national highways, the GQ project or the local roads on spatial activities. Our results make an important contribution in this area. It appears from the results the impact of highways in urbanization process in West Bengal is quite opposite of what Baum-Snow et al. ( 2020 ) observes in China. Instead of facilitating agglomeration, it promotes dispersion of non-farm activities away from the existing cities. This may have happened due to lack of infrastructure development in the existing cities which failed to solve the problems of congestion, pollution and high housing-prices at the cities. As theoretically the dispersion may lead to fall in welfare, the results of the paper suggest that in West Bengal along with the investment in the highway projects perhaps more investment in developing the infrastructure of existing urban centers other than Kolkata could have been welfare improving.

Is there any limitation of the reported results? The results show the way the transport infrastructure has affected the transformation of a village to a Census Town. However, it does not control for the economic policies that may have utilized the transport infrastructure to trigger the change. In Indian context, the obvious candidate of such a policy would have been the economic reform undertaken in 1991. But, in a recent paper Tripathi ( 2019 ) shows that economic reform has no effect on urbanization in India. The local level development policies could have an influence on the villages helping them to transform into Census Towns. However, the state level policies should have equal effect on the districts and the study controls for the district specific fixed effects. The paper does not explore the exact channels through which transport infrastructure works. This remains as future research agenda.

The other limitation of the paper is that it does not analyze the more recent trend in development of Census Towns in West Bengal in the last ten years, during 2011–2021. Here the study has suffered from non-availability of the required data. The paper has used the Census data published by the Government of India. The Census report in India is published every 10 years. The 2021 report is delayed due to COVID-19 related restrictions in surveys. Therefore, there is no way to have authentic and comparable data to give general observations about the development of Census Town in West Bengal in the past 10 years. A future study may pick this up also as a research agenda.

See Henderson and Turner (2020) and Sridhar (2021) about two competing views on this.

Table A.1 in the Appendix shows that the relative proportions of the population living in different settlement size classes, both for India as a whole and for the West Bengal study area for years 2001 and 2011. The rise in proportion of population living in smaller cities in West Bengal is significantly higher than the national average. In West Bengal the proportion of population living in larger cities with more than 0.1 million population was also sharply falling over during 2001–2011.

See http://wbtrafficpolice.com accessed on 28.09.2021.

See https://www.statista.com/ accessed on 28.09.2021.

See Proost and Thisse (2019) for a recent survey of the literature.

We thank one of the reviewers for attracting our attention to this issue.

Statutory Town.

One of the reviewers suggests that this may indicate to the underlying process of “step migration” from village to large cities as proposed by Ravenstein ( 1885 ). However, testing this hypothesis is beyond the scope of the present paper due to non-availability of data.

Aggarwal S (2018) Do Rural Roads Create Pathways out of Poverty? Evidence from India. J Dev Econ 133(2018) :375–395.

Balakrishnan S (2013) Highway urbanization and land conflicts: the challenges to decentralization in India. PacificAffairs 86(4):785–811

Google Scholar

Baum-Snow N, Henderson JV, Turner MA , Zhang Q, Brandt L (2000) Does investment in national highways help or hurt hinterland city growth? J Urban Econ 115:103–124

Brueckner J (2011) Lectures on Urban economics. MIT University Press, Cambridge

Census of India. Various Years. Town and Village Directory, Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Government of India, New Delhi

Chakrabarti S, Mukherjee V (2020) Birth of census Towns in India; an economic analysis. South Asian J Macroecon Publ Finance 9(2):139–166

Article Google Scholar

Chandra A, Thompson E (2000) Does public infrastructure affect economic activity? evidence from the rural interstate highway system. Reg Sci Urban Econ 30(4):457–490

Van Dujine RJ, Nijman J (2019) India’s emergent urban formations. Ann Am Assoc Geogr 109(6):1978–1998

Ghani, E, Goswami A, Kerr W (2012) Is India’s Manufacturing Sector Moving Away from Cities? NBER Working Paper No.17992

Head K, Mayer T (2014) Gravity equations: workhorse, toolkit, and cookbook. In: Gopinath G, Helpman E, Rogoff K (eds) Handbook of international economics, vol 4. North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp 131–195

Helpman E (1998) The size of regions. in topics in public economics: theoretical and applied analysis David Pines, Efrail Sadka, and Itzhak Zilcha (ed) 33–54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Janelle DG (1968) Central place development in a time-space framework. Prof Geogr 20:5–10

Krugman P (1991) Increasing returns and economic geography. J Polit Econ 99(3):483–499

Mahajan K, Nagraj R (2017) Rural construction employment boom during 2000–12, Evidence from NSSO Surveys. Economic and Political Weekly, December 30, 2017 vol no LII (52):54–63

Mathur OP, Naqvi HN, Laroiya A, Samyukta VS, Verma H (2021) State of the cities report. Institute of Social Sciences: New Delhi

Mukhopadhyay P, Zerah H, Samanta G, Maria A (2016) Understanding India's urban frontier: what is behind the emergence of census towns in India? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 7923

Proost S, Thisse J-F (2019) What can be learnt from spatial economics? J Econ Literature 57(3):575–643

Ravenstein EG (1885) The laws of migration, J Stat Soc Lond 48(2):167–235

Rossi-Hansberg E (2005) A Spatial Theory of Trade. Am Econ Rev 95(5):1464–1491

Sharma A (2013) Exclusionary urbanization and changing migration pattern in India: Is commuting by workers a feasible alternative? Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai, India

Sridhar KS (2021) Is India’s urbanization really too low?, Area development and policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2019.1590153

Tripathi S (2019) Do economic reforms promote urbanization in India? Asia Pac J Reg Sci 3:647–674

Vernon HJ, Turner MA (2020) Urbanization in the developing world: too early or too slow? J Econ Perspectives 34(3):150–173

World Cities Report (2016) Urbanization and Development: Emerging Futures, UNHabitat, United Nationals Human Settlement Program: Nairobi

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, Ramsaday College, Howrah, India

Saumyabrata Chakrabarti

Department of Economics and Finance, BITS Pilani, Hyderabad Campus, Hyderabad, India

Vivekananda Mukherjee

Department of Economics, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Vivekananda Mukherjee .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Human participants and/or animals

The research has not involved any Human Participants and/or Animals.

Informed consent

The paper has informed consent from all the parties involved.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank four anonymous reviewers of the Journal for their helpful comments. We also thank the Editor-in-Chief of the Journal Yoshiro Higano for his cooperation. The usual disclaimer applies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (XLSX 26 KB)

See appendix Table

About this article

Chakrabarti, S., Mukherjee, V. Role of transport infrastructure in birth of census towns in West Bengal. Asia-Pac J Reg Sci 6 , 593–616 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-021-00224-5

Download citation

Received : 21 June 2021

Accepted : 20 November 2021

Published : 07 January 2022

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-021-00224-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Census Towns

- Transport infrastructure

- Local roads

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

© 2023 Sorting Hat Technologies Pvt Ltd

- LIC Assistant

- RBI Grade B

- RBI Assistant

- Upcoming Bank Exam

- IBPS PO Syllabus

- IBPS Clerk Syllabus

- IBPS RRB Syllabus

- IBPS SO Syllabus

- SBI PO Syllabus

- SBI Clerk Syllabus

- LIC Assistant Syllabus

- LIC AAO Syllabus

- LIC ADO Syllabus

- RBI Assistant Syllabus

- RBI Grade B Syllabus

- Magazine Download

- PYQs Download

- Bank Exams Notes

- Free Courses

- Scholarship Test

- Test Series

- Learning Festival

- Topper Interviews

- Paper Analysis

West Bengal: Urban Population as Per Census 2011

The Census of India 2011 was conducted in two phases; the first phase was conducted from April 1 to 10, and the second phase was conducted from April 20 to 28.

Table of Content

The Census of India 2011 was conducted in two phases; the first phase was conducted from April 1 to 10, and the second phase was conducted from April 20 to 28. The main objective of the census was to enumerate all persons residing in India on the night of March 31, 2011. In this article, we will take a look at the urban population of West Bengal. We will also look at the sex ratio, literacy rate, and ST population in West Bengal.

West Bengal Population, 2011

According to the 2011 Census, West Bengal has a population of 9.13 million people, an increase from the figure of 8.02 million in the 2001 census. The combined population of West Bengal as per the 2011 census is 91,276,115 individuals, with males accounting for 46,809,027 and females for 44,467,088. In 2001, India’s total population was 1.21 billion people, of whom males made up 42 % and females 57 %. During this decade, the country’s overall population increased by 13.84 %, whereas it grew by 17.84% in the previous one. The West Bengal population makes up 7.54% of India in 2011.

West Bengal’s literacy rate has seen an upward trend and was 76.26 % in the 2011 population census, with male literacy at 81.69 % and female literacy at 70.54 %. Male literacy was 81.69 % in 2001 while female literacy was 77.02 % back then (2001).

The Global Development Index ranks India the 88th country in terms of development, with a Human Development Index rating of 0.462 (Q2). According to UNESCO-IBRD statistics from 2010, West Bengal has a population of 3.35 billion people and boasts an average literacy rate of 80%.

The total area of West Bengal is 88,752 square kilometres. The density of West Bengal is 1,028 people per square kilometre, which is greater than the nationwide average of 382 persons per square kilometre. In 2001, the density in West Bengal was 903 people per square kilometre, while the national average was 324 persons per sq km.

There are 956 females for every 1000 males in West Bengal, which is less than the national average of 940 according to the census of 2011. According to data from 2001, the sex ratio of women in West Bengal was 934 per 1000 males.

Hindus make up the majority in West Bengal, with 70.54 % of the population following them. Muslims are the second most numerous religion in West Bengal, accounting for approximately 27.01 % of residents. Christianity is followed by 0.72 % in West Bengal, 0.07% in Jainism, 0.07% in Sikhism, and 0.07 % in Buddhism. Approximately 1.03 % stated ‘Other Religion’, around 0.25 % said No Particular Religion.

West Bengal Urban Population, 2011

31.87 % of the whole population of West Bengal resides in cities. The overall figure of people living in cities is 29,093,002 of which 14,964,082 are males and 14,128,920 are females. The urban population has grown by 31.87% over the last ten years.

In urban areas of West Bengal, the sex ratio was 944 females for every 1000 males. For kid (0-6) sex ratio, the figure in the city was 947 girls per 1000 boys. The total number of children (0-6 years old) living in urban West Bengal regions was 2,760,756. Of the total population in the urban region, 9.49 % were children (0-6). Bengal’s total literacy rate was 84.78 % males had a literacy rate of 88.37 % and females had a literacy rate of 76.01%. In the city region of West Bengal, there were 22,324,502 literates.

West Bengal Rural Population, 2011

Around 68.13% of the entire population of West Bengal state resides in rural areas, according to government statistics. According to the official figures, males and females were 31,844,945 and 30,338,168 respectively. The total population of rural areas in West Bengal was 62,183,113 individuals. The growth rate in the previous decade, calculated (2001-2011), was 68.13%.

The female sex ratio in rural areas of West Bengal state was 953 to 1000, while the child (0-6 age) sex ratio was 959 girls per 1000 boys. In rural regions of West Bengal, there are 7,820,710 children (0-6 years old). The child population accounts for 12.58% of the overall rural population.

In rural Bengal, the overall literacy rate was 78.44 % among males and 61.98 % among females. In West Bengal, the average literacy rate for rural areas was 72.13 %. In rural regions of West Bengal, there were 39,213,779 literates.

District Wise Census Analysis

From the above data, it is clear that West Bengal has made significant progress in terms of development and urbanisation in the last decade. The state has a high literacy rate and a relatively low sex ratio. The majority of the population is Hindu, followed by Muslims. The state has a large rural population but is gradually becoming more urbanised. There is still a large disparity between the literacy rates of rural and urban areas, but overall the state is progressing well.

Frequently asked questions

Get answers to the most common queries related to the BANK Examination Preparation.

What is the total population of West Bengal as per the 2011 Census?

Ans. The total population of West Bengal as per the 2011 Census is 91,276,115.

What is the urban population of West Bengal as per the 2011 Census?

Ans. The urban population of West Bengal as per the 2011 Census is 29,903,002.

What is the rural population of West Bengal as per the 2011 Census?

Ans. The rural population of West Bengal as per the 2011 Census is 62,183,113.

What is the literacy rate of West Bengal as per the 2011 Census?

Ans. The literacy rate of West Bengal as per the 2011 Census is 76.26%.

Crack Bank Exam with Unacademy

Get subscription and access unlimited live and recorded courses from India’s best educators

- Structured syllabus

- Daily live classes

- Tests & practice

Notifications

Get all the important information related to the Bank Exam including the process of application, important calendar dates, eligibility criteria, exam centers etc.

Bank Exam Application Process