Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Research Guides

Multiple Case Studies

Nadia Alqahtani and Pengtong Qu

Description

The case study approach is popular across disciplines in education, anthropology, sociology, psychology, medicine, law, and political science (Creswell, 2013). It is both a research method and a strategy (Creswell, 2013; Yin, 2017). In this type of research design, a case can be an individual, an event, or an entity, as determined by the research questions. There are two variants of the case study: the single-case study and the multiple-case study. The former design can be used to study and understand an unusual case, a critical case, a longitudinal case, or a revelatory case. On the other hand, a multiple-case study includes two or more cases or replications across the cases to investigate the same phenomena (Lewis-Beck, Bryman & Liao, 2003; Yin, 2017). …a multiple-case study includes two or more cases or replications across the cases to investigate the same phenomena

The difference between the single- and multiple-case study is the research design; however, they are within the same methodological framework (Yin, 2017). Multiple cases are selected so that “individual case studies either (a) predict similar results (a literal replication) or (b) predict contrasting results but for anticipatable reasons (a theoretical replication)” (p. 55). When the purpose of the study is to compare and replicate the findings, the multiple-case study produces more compelling evidence so that the study is considered more robust than the single-case study (Yin, 2017).

To write a multiple-case study, a summary of individual cases should be reported, and researchers need to draw cross-case conclusions and form a cross-case report (Yin, 2017). With evidence from multiple cases, researchers may have generalizable findings and develop theories (Lewis-Beck, Bryman & Liao, 2003).

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Lewis-Beck, M., Bryman, A. E., & Liao, T. F. (2003). The Sage encyclopedia of social science research methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Key Research Books and Articles on Multiple Case Study Methodology

Yin discusses how to decide if a case study should be used in research. Novice researchers can learn about research design, data collection, and data analysis of different types of case studies, as well as writing a case study report.

Chapter 2 introduces four major types of research design in case studies: holistic single-case design, embedded single-case design, holistic multiple-case design, and embedded multiple-case design. Novice researchers will learn about the definitions and characteristics of different designs. This chapter also teaches researchers how to examine and discuss the reliability and validity of the designs.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

This book compares five different qualitative research designs: narrative research, phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, and case study. It compares the characteristics, data collection, data analysis and representation, validity, and writing-up procedures among five inquiry approaches using texts with tables. For each approach, the author introduced the definition, features, types, and procedures and contextualized these components in a study, which was conducted through the same method. Each chapter ends with a list of relevant readings of each inquiry approach.

This book invites readers to compare these five qualitative methods and see the value of each approach. Readers can consider which approach would serve for their research contexts and questions, as well as how to design their research and conduct the data analysis based on their choice of research method.

Günes, E., & Bahçivan, E. (2016). A multiple case study of preservice science teachers’ TPACK: Embedded in a comprehensive belief system. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11 (15), 8040-8054.

In this article, the researchers showed the importance of using technological opportunities in improving the education process and how they enhanced the students’ learning in science education. The study examined the connection between “Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge” (TPACK) and belief system in a science teaching context. The researchers used the multiple-case study to explore the effect of TPACK on the preservice science teachers’ (PST) beliefs on their TPACK level. The participants were three teachers with the low, medium, and high level of TPACK confidence. Content analysis was utilized to analyze the data, which were collected by individual semi-structured interviews with the participants about their lesson plans. The study first discussed each case, then compared features and relations across cases. The researchers found that there was a positive relationship between PST’s TPACK confidence and TPACK level; when PST had higher TPACK confidence, the participant had a higher competent TPACK level and vice versa.

Recent Dissertations Using Multiple Case Study Methodology

Milholland, E. S. (2015). A multiple case study of instructors utilizing Classroom Response Systems (CRS) to achieve pedagogical goals . Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3706380)

The researcher of this study critiques the use of Classroom Responses Systems by five instructors who employed this program five years ago in their classrooms. The researcher conducted the multiple-case study methodology and categorized themes. He interviewed each instructor with questions about their initial pedagogical goals, the changes in pedagogy during teaching, and the teaching techniques individuals used while practicing the CRS. The researcher used the multiple-case study with five instructors. He found that all instructors changed their goals during employing CRS; they decided to reduce the time of lecturing and to spend more time engaging students in interactive activities. This study also demonstrated that CRS was useful for the instructors to achieve multiple learning goals; all the instructors provided examples of the positive aspect of implementing CRS in their classrooms.

Li, C. L. (2010). The emergence of fairy tale literacy: A multiple case study on promoting critical literacy of children through a juxtaposed reading of classic fairy tales and their contemporary disruptive variants . Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3572104)

To explore how children’s development of critical literacy can be impacted by their reactions to fairy tales, the author conducted a multiple-case study with 4 cases, in which each child was a unit of analysis. Two Chinese immigrant children (a boy and a girl) and two American children (a boy and a girl) at the second or third grade were recruited in the study. The data were collected through interviews, discussions on fairy tales, and drawing pictures. The analysis was conducted within both individual cases and cross cases. Across four cases, the researcher found that the young children’s’ knowledge of traditional fairy tales was built upon mass-media based adaptations. The children believed that the representations on mass-media were the original stories, even though fairy tales are included in the elementary school curriculum. The author also found that introducing classic versions of fairy tales increased children’s knowledge in the genre’s origin, which would benefit their understanding of the genre. She argued that introducing fairy tales can be the first step to promote children’s development of critical literacy.

Asher, K. C. (2014). Mediating occupational socialization and occupational individuation in teacher education: A multiple case study of five elementary pre-service student teachers . Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3671989)

This study portrayed five pre-service teachers’ teaching experience in their student teaching phase and explored how pre-service teachers mediate their occupational socialization with occupational individuation. The study used the multiple-case study design and recruited five pre-service teachers from a Midwestern university as five cases. Qualitative data were collected through interviews, classroom observations, and field notes. The author implemented the case study analysis and found five strategies that the participants used to mediate occupational socialization with occupational individuation. These strategies were: 1) hindering from practicing their beliefs, 2) mimicking the styles of supervising teachers, 3) teaching in the ways in alignment with school’s existing practice, 4) enacting their own ideas, and 5) integrating and balancing occupational socialization and occupational individuation. The study also provided recommendations and implications to policymakers and educators in teacher education so that pre-service teachers can be better supported.

Multiple Case Studies Copyright © 2019 by Nadia Alqahtani and Pengtong Qu is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Perspectives from Researchers on Case Study Design

by Janet Salmons, PhD, Research Community Manager for SAGE Methodspace

Research design is the focus for the first quarter of 2023. Find a post about case study design , and read the unfolding series of posts here .

What is a “case study” research design?

Linda Bloomberg describes a case study as:

An in-depth exploration from multiple perspectives of the richness and complexity of a particular social unit, system, or phenomenon. Its primary purpose is to generate understanding and insights in order to gain knowledge and inform professional practice, policy development, and community or social action. Case study research is typically extensive; it draws on multiple methods of data collection and involves multiple data sources.

The researcher begins by identifying a specific case or set of cases to be studied. Each case is an entity that is described within certain parameters, such as a specific time frame, place, event, and process. Hence, the case becomes a bounded system . Typically, case study researchers analyze the real-life cases that are currently in progress so that they can gather accurate information that is not lost by time.

This method culminates in the production of a detailed description of a setting and its participants, accompanied by an analysis of the data for themes, patterns, and issues. A case study is therefore both a process of inquiry about the case at hand and the product of that inquiry. (Bloomberg, 2018, p. 276)

Case studies use more than one form of data either within a research paradigm (multimodal ), or more than one form of data from different paradigms (mixed methods). As Bloomberg notes, the case study method is employed across disciplines, including education, health care, social work, history, sociology, management studies, and organizational studies. When you look at lists of most-read and most-cited articles you will find that this flexible approach is widely used and published. Here are some open-access articles about multimodal qualitative or mixed methods designs that include both qualitative and quantitative elements.

Qualitative Research with Case Studies

Brannen, J., & Nilsen, A. (2011). Comparative Biographies in Case-based Cross-national Research: Methodological Considerations. Sociology, 45(4), 603–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511406602

Abstract. This article examines some methodological issues relating to an embedded case study design adopted in a comparative cross-national study of working parents covering three levels of social context: the macro level; the workplace level; and the individual level. It addresses issues of generalizability, in particular the importance of criteria for the selection of cases in the research design and analysis phases. To illustrate the benefits of the design the article focuses on the level of individual biographies. Three exemplars of biographical trajectories and experiences are presented and discussed. It is argued that a multi-tiered design and a comparative biographical approach can add to the understanding of individual experience by placing it in context and thus yield knowledge that is of general sociological relevance by demonstrating the interrelatedness of agency and structure.

Ebneyamini, S., & Sadeghi Moghadam, M. R. (2018). Toward Developing a Framework for Conducting Case Study Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918817954

Abstract. This article reviews the use of case study research for both practical and theoretical issues especially in management field with the emphasis on management of technology and innovation. Many researchers commented on the methodological issues of the case study research from their point of view thus, presenting a comprehensive framework was missing. We try representing a general framework with methodological and analytical perspective to design, develop, and conduct case study research. To test the coverage of our framework, we have analyzed articles in three major journals related to the management of technology and innovation to approve our framework. This study represents a general structure to guide, design, and fulfill a case study research with levels and steps necessary for researchers to use in their research.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

Abstract. This article examines five common misunderstandings about case-study research: (a) theoretical knowledge is more valuable than practical knowledge; (b) one cannot generalize from a single case, therefore, the single-case study cannot contribute to scientific development; (c) the case study is most useful for generating hypotheses, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypotheses testing and theory building; (d) the case study contains a bias toward verification; and (e) it is often difficult to summarize specific case studies. This article explains and corrects these misunderstandings one by one and concludes with the Kuhnian insight that a scientific discipline without a large number of thoroughly executed case studies is a discipline without systematic production of exemplars, and a discipline without exemplars is an ineffective one. Social science may be strengthened by the execution of a greater number of good case studies.

Morgan SJ, Pullon SRH, Macdonald LM, McKinlay EM, Gray BV. Case Study Observational Research: A Framework for Conducting Case Study Research Where Observation Data Are the Focus. Qualitative Health Research. 2017;27(7):1060-1068. doi:10.1177/1049732316649160

Abstract. Case study research is a comprehensive method that incorporates multiple sources of data to provide detailed accounts of complex research phenomena in real-life contexts. However, current models of case study research do not particularly distinguish the unique contribution observation data can make. Observation methods have the potential to reach beyond other methods that rely largely or solely on self-report. This article describes the distinctive characteristics of case study observational research, a modified form of Yin’s 2014 model of case study research the authors used in a study exploring interprofessional collaboration in primary care. In this approach, observation data are positioned as the central component of the research design. Case study observational research offers a promising approach for researchers in a wide range of health care settings seeking more complete understandings of complex topics, where contextual influences are of primary concern. Future research is needed to refine and evaluate the approach.

Rule, P., & John, V. M. (2015). A Necessary Dialogue: Theory in Case Study Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods , 14 (4). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915611575

Abstract. This article is premised on the understanding that there are multiple dimensions of the case–theory relation and examines four of these: theory of the case, theory for the case, theory from the case, and a dialogical relation between theory and case. This fourth dimension is the article’s key contribution to theorizing case study. Dialogic engagement between theory and case study creates rich potential for mutual formation and generative tension. The article argues that the process of constructing and conducting the case is theory laden, while the outcomes of the study might also have theoretical implications. Case study research that is contextually sensitive and theoretically astute can contribute not only to the application and revision of existing theory but also to the development of new theory. The case thus provides a potentially generative nexus for the engagement of theory, context, and research.

Thomas, G. (2011). A Typology for the Case Study in Social Science Following a Review of Definition, Discourse, and Structure. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(6), 511–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800411409884

Abstract. The author proposes a typology for the case study following a definition wherein various layers of classificatory principle are disaggregated. First, a clear distinction is drawn between two parts: (1) the subject of the study, which is the case itself, and (2) the object, which is the analytical frame or theory through which the subject is viewed and which the subject explicates. Beyond this distinction the case study is presented as classifiable by its purposes and the approaches adopted— principally with a distinction drawn between theory-centered and illustrative study. Beyond this, there are distinctions to be drawn among various operational structures that concern comparative versus noncomparative versions of the form and the ways that the study may employ time. The typology reveals that there are numerous valid permutations of these dimensions and many trajectories, therefore, open to the case inquirer.

VanWynsberghe, R., & Khan, S. (2007). Redefining Case Study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods , 6 (2), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690700600208

Abstract. In this paper the authors propose a more precise and encompassing definition of case study than is usually found. They support their definition by clarifying that case study is neither a method nor a methodology nor a research design as suggested by others. They use a case study prototype of their own design to propose common properties of case study and demonstrate how these properties support their definition. Next, they present several living myths about case study and refute them in relation to their definition. Finally, they discuss the interplay between the terms case study and unit of analysis to further delineate their definition of case study. The target audiences for this paper include case study researchers, research design and methods instructors, and graduate students interested in case study research.

Mixed Methods Research with Case Studies

Guetterman, T. C., & Fetters, M. D. (2018). Two Methodological Approaches to the Integration of Mixed Methods and Case Study Designs: A Systematic Review. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(7), 900–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218772641

Abstract. Case study has a tradition of collecting multiple forms of data—qualitative and quantitative—to gain a more complete understanding of the case. Case study integrates well with mixed methods, which seeks a more complete understanding through the integration of qualitative and quantitative research. We identify and characterize “mixed methods–case study designs” as mixed methods studies with a nested case study and “case study–mixed methods designs” as case studies with nested mixed methods. Based on a review of published research integrating mixed methods and case study designs, we describe key methodological features and discuss four exemplar interdisciplinary studies.

Luyt, R. (2012). A Framework for Mixing Methods in Quantitative Measurement Development, Validation, and Revision: A Case Study. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(4), 294–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689811427912

Abstract. A framework for quantitative measurement development, validation, and revision that incorporates both qualitative and quantitative methods is introduced. It extends and adapts Adcock and Collier’s work, and thus, facilitates understanding of quantitative measurement development, validation, and revision as an integrated and cyclical set of procedures best achieved through mixed methods research. It also offers a systematic guide concerning how these procedures may be undertaken through detailing key “stages,” “levels,” and practical “tasks.” A case study illustrates how qualitative and quantitative methods may be mixed through the use of the proposed framework in the cross-cultural content- and construct-related validation and subsequent revision of a quantitative measure. The contribution of this article to mixed methods research literature is briefly discussed.

Mason, W., Morris, K., Webb, C., Daniels, B., Featherstone, B., Bywaters, P., Mirza, N., Hooper, J., Brady, G., Bunting, L., & Scourfield, J. (2020). Toward Full Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Methods in Case Study Research: Insights From Investigating Child Welfare Inequalities. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 14(2), 164–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689819857972

Abstract. Delineation of the full integration of quantitative and qualitative methods throughout all stages of multisite mixed methods case study projects remains a gap in the methodological literature. This article offers advances to the field of mixed methods by detailing the application and integration of mixed methods throughout all stages of one such project; a study of child welfare inequalities. By offering a critical discussion of site selection and the management of confirmatory, expansionary and discordant data, this article contributes to the limited body of mixed methods exemplars specific to this field. We propose that our mixed methods approach provided distinctive insights into a complex social problem, offering expanded understandings of the relationship between poverty, child abuse, and neglect.

Onghena, P., Maes, B., & Heyvaert, M. (2019). Mixed Methods Single Case Research: State of the Art and Future Directions. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 13(4), 461–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689818789530

Abstract. Mixed methods single case research (MMSCR) is research in which single case experimental and qualitative case study methodologies, and their accompanying sets of methods and techniques, are integrated to answer research questions that concern a single case. This article discusses the historical roots and the distinct nature of MMSCR, the kinds of knowledge MMSCR produces, its philosophical underpinnings, examples of MMSCR, and the trustworthiness and validity of MMSCR. Methodological challenges relate to the development of a critical appraisal tool for MMSCR, to the team work that is involved in designing and conducting MMSCR studies, and to the application of mixed methods research synthesis for multiple case studies and single case experiments.

Sharp, J. L., Mobley, C., Hammond, C., Withington, C., Drew, S., Stringfield, S., & Stipanovic, N. (2012). A Mixed Methods Sampling Methodology for a Multisite Case Study. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(1), 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689811417133

Abstract. The flexibility of mixed methods research strategies makes such approaches especially suitable for multisite case studies. Yet the utilization of mixed methods to select sites for these studies is rarely reported. The authors describe their pragmatic mixed methods approach to select a sample for their multisite mixed methods case study of a statewide education policy initiative in the United States. The authors designed a four-stage sequential mixed methods site selection strategy to select eight sites in order to capture the broader context of the research, as well as any contextual nuances that shape policy implementation. The authors anticipate that their experience would provide guidance to other mixed methods researchers seeking to maximize the rigor of their multisite case study sampling designs.

Bloomberg, L. (2018). Case study. In B. B. Frey (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation . https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506326139

More Posts about Research Design

Julianne Cheek and Elise Øby, co-authors of the book Research Design: Why Thinking About Design Matters, discuss how to make decisions about what qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods data to collect and how to do so. This post is the third of a three-part series of posts that feature ten author interviews.

What if we didn’t have to go fast to do our academic work and research? What if we could embrace the spaces and places around us to slow down? What could that mean for us personally, professionally, and in how we relate to social justice and ecological issues?

Doctoral student Sandra Flores discusses her research in Puerto Rico, and what she learned from the experience.

Julianne Cheek and Elise Øby, co-authors of the book Research Design: Why Thinking About Design Matters, discuss how to make decisions about methodology in this collection of video interviews. This post is the second of a three-part series of posts that feature ten author interviews.

Learn about action and participatory research methods, and ways to design and carry out research with, not on, communities.

Is it too hard to address problems in our complex world with one type of data? Mixed methods might be the answer. Find explanations and open-access resources in this post.

Chart research directions that take you to the roots of the problem. Learn more in this guest post from Dr. Donna Mertens.

We need to think about research before we design and conduct it.

Julianne Cheek and Elise Øby, co-authors of the book Research Design: Why Thinking About Design Matters, discuss the first three chapters in these video interviews: Chapter 1 – Research Design: What You Need to Think About and Why

Chapter 2 – Ethical Issues in Research Design

Chapter 3 – Developing Your Research Questions

The process for researching literature on research methods is somewhat different from the process used for researching literature about the topic, problem, or questions. What should we keep in mind when selecting methods literature?

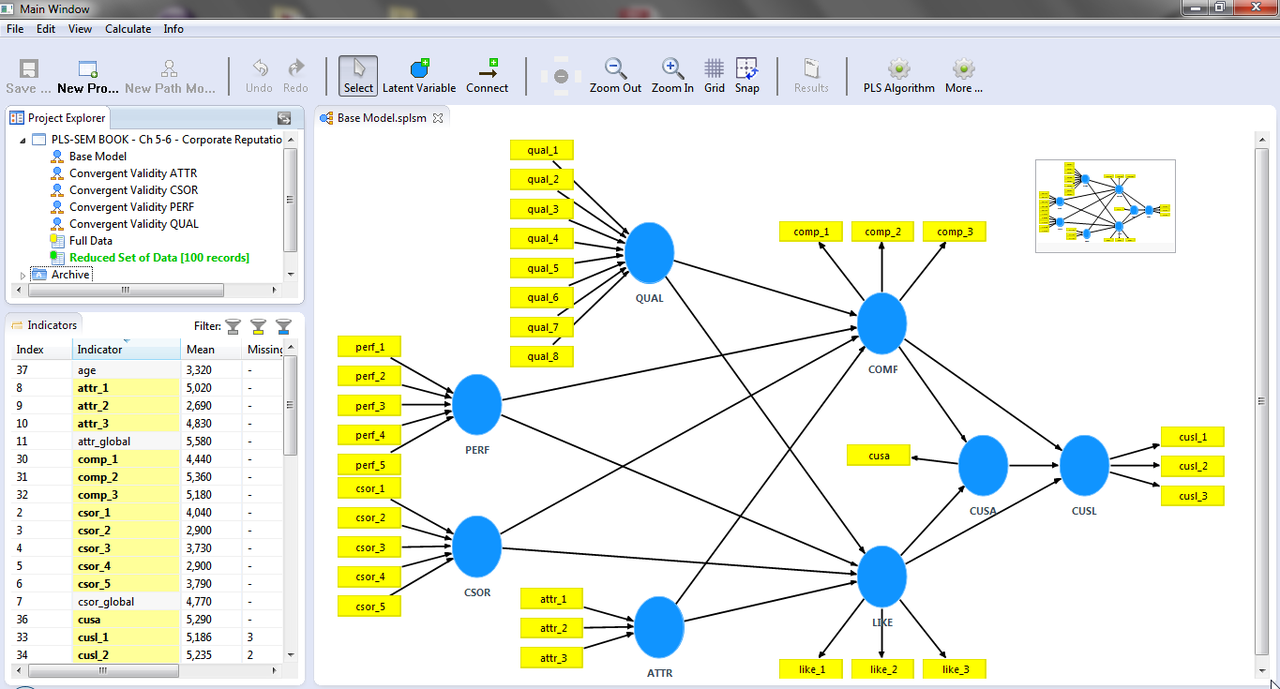

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) enables researchers to model and estimate complex cause-effects relationship models

How do researchers make design decisions about the methodology and methods?

In-depth comprehension and interpretation of social events, human experiences, and behaviours are often the main goals of qualitative researchers. Learn about the primary concerns of qualitative researchers in this guest post by Pinaki Burman.

Learn about connecting the unit of analysis with the qualitative methodology.

Research can often feel like an overwhelming process. If you are a novice researcher, there can be a lot of new terminology to learn too. This is where research road mapping can help!

These difficult times present challenges for researchers. Find five original posts by Robert Kozinets about using Netnography to study sensitive topics.

Looking back at 2023, find all posts here! We explored stages of a research project, from concept to publication. In each quarter we focused on one part of the process. In this recap for the year you will find original guest posts, interviews, curated collections of open-access resources, recordings from webinars or roundtable discussions, and instructional resources.

Read this collection of multidisciplinary articles to explore epistemological questions in Indigenous research.

Methods Film Fest! We can read what they write, but what do researchers say? What are they thinking about, what are they exploring, what insights do they share about methodologies, methods, and approaches? In 2023 Methodspace produced 32 videos, and you can find them all in this post!

Find suggestions for navigating the problem formulation stage that precedes research design in social science research.

Let’s begin this quarter’s exploration of research design by thinking about the research problem or topic. Who decides what to study?

This post includes tips about writing qualitative proposals excerpted from Research Design by Creswell and Creswell.

Learn how to design and defend your PhD research with the Idea Puzzle software from Ricardo Morais.

Dr. Stephen Gorard defines and explains randomness in a research context.

Have you seen Dr. Gorard use card tricks to teach research methods? Watch this video!

Some of us feel that technology is everywhere, but that is not the case for everyone. Inequalities persist. What do these disparities mean for researchers?

Designing Survey Research

Designing research with case study methods.

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Methodology: Multiple-Case Qualitative Study

- First Online: 01 July 2021

Cite this chapter

- Feng Ding 2

232 Accesses

This longitudinal multiple-case study is qualitative in nature, with data collection lasting for more than a year. As this study set out to understand the experiences, feelings, emotions, conceptions, and understanding of students about their experiences, a qualitative research approach was adopted to “identify issues from the perspective of” the participants, and to study them in a natural setting (Hennink et al., 2011, p. 9).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Apple Newspaper, 28/04/2013, http://hk.apple.nextmedia.com/news/art/20130428/18242744

Source: http://life.dayoo.com/edu/113887/201301/22/113887_28581159.htm

University of Hong Kong Public Poll, 2012. http://hkupop.hku.hk/english/release/release937.html

Buddy writer, 2010-1011 http://web02.carmelss.edu.hk/buddingwriters/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=971:importing-students-from-the-mainland-brings-more-harm-than-good-to-hong-kong&catid=109&Itemid=66

Bazeley, P., & Richards, L. (2000). The NVivo qualitative project book . Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (2007). Qualitative research for education. An introduction to theory and methods . Allyn and Bacon.

Google Scholar

Chee, W. C. (2012). Envisioned belonging: Cultural differences and ethnicities in Hong Kong schooling. Asian Anthropology (1683478X), 11 (1), 89–105.

Article Google Scholar

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches . Sage.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2000). Handbook of qualitative research . Sage Publications.

Ding, F., & Stapleton, P. (2015). Self-emergent peer support using online social networking during cross-border transition. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31 (6), 671–684.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies . Oxford University Press.

Evans, S. (2011). Hong Kong English and the professional world. World Englishes, 30 (3), 293–316.

Gao, X. (2010). Strategic language learning: The roles of agency and context . Multilingual Matters.

Hennink, M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2011). Qualitative research methods . Sage.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage.

Ministry of Education. (2007). College English curriculum requirements . Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods . Sage Publications.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods . Sage Publications.

Reason, R., Terenzini, P., & Domingo, R. (2006). First things first: Developing academic competence in the first year of college. Research in Higher Education, 47 (2), 149–175.

Stake, R. E. (2006). Multiple case study analysis . Guilford Press.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness . Penguin Books.

Willis, J. (2007). Qualitative research methods in education and educational technology . Sage Publications.

Xie, C. X. (2010). Mainland Chinese students’ adjustment to studying and living in Hong Kong . Unpublished doctoral dissertation of the University of Leicester.

Yin, R. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods . Sage.

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods . Sage.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Ding, F. (2021). Methodology: Multiple-Case Qualitative Study. In: First Year in a Multilingual University. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0796-7_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0796-7_3

Published : 01 July 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-0795-0

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-0796-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

5 Benefits of Learning Through the Case Study Method

- 28 Nov 2023

While several factors make HBS Online unique —including a global Community and real-world outcomes —active learning through the case study method rises to the top.

In a 2023 City Square Associates survey, 74 percent of HBS Online learners who also took a course from another provider said HBS Online’s case method and real-world examples were better by comparison.

Here’s a primer on the case method, five benefits you could gain, and how to experience it for yourself.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is the Harvard Business School Case Study Method?

The case study method , or case method , is a learning technique in which you’re presented with a real-world business challenge and asked how you’d solve it. After working through it yourself and with peers, you’re told how the scenario played out.

HBS pioneered the case method in 1922. Shortly before, in 1921, the first case was written.

“How do you go into an ambiguous situation and get to the bottom of it?” says HBS Professor Jan Rivkin, former senior associate dean and chair of HBS's master of business administration (MBA) program, in a video about the case method . “That skill—the skill of figuring out a course of inquiry to choose a course of action—that skill is as relevant today as it was in 1921.”

Originally developed for the in-person MBA classroom, HBS Online adapted the case method into an engaging, interactive online learning experience in 2014.

In HBS Online courses , you learn about each case from the business professional who experienced it. After reviewing their videos, you’re prompted to take their perspective and explain how you’d handle their situation.

You then get to read peers’ responses, “star” them, and comment to further the discussion. Afterward, you learn how the professional handled it and their key takeaways.

HBS Online’s adaptation of the case method incorporates the famed HBS “cold call,” in which you’re called on at random to make a decision without time to prepare.

“Learning came to life!” said Sheneka Balogun , chief administration officer and chief of staff at LeMoyne-Owen College, of her experience taking the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program . “The videos from the professors, the interactive cold calls where you were randomly selected to participate, and the case studies that enhanced and often captured the essence of objectives and learning goals were all embedded in each module. This made learning fun, engaging, and student-friendly.”

If you’re considering taking a course that leverages the case study method, here are five benefits you could experience.

5 Benefits of Learning Through Case Studies

1. take new perspectives.

The case method prompts you to consider a scenario from another person’s perspective. To work through the situation and come up with a solution, you must consider their circumstances, limitations, risk tolerance, stakeholders, resources, and potential consequences to assess how to respond.

Taking on new perspectives not only can help you navigate your own challenges but also others’. Putting yourself in someone else’s situation to understand their motivations and needs can go a long way when collaborating with stakeholders.

2. Hone Your Decision-Making Skills

Another skill you can build is the ability to make decisions effectively . The case study method forces you to use limited information to decide how to handle a problem—just like in the real world.

Throughout your career, you’ll need to make difficult decisions with incomplete or imperfect information—and sometimes, you won’t feel qualified to do so. Learning through the case method allows you to practice this skill in a low-stakes environment. When facing a real challenge, you’ll be better prepared to think quickly, collaborate with others, and present and defend your solution.

3. Become More Open-Minded

As you collaborate with peers on responses, it becomes clear that not everyone solves problems the same way. Exposing yourself to various approaches and perspectives can help you become a more open-minded professional.

When you’re part of a diverse group of learners from around the world, your experiences, cultures, and backgrounds contribute to a range of opinions on each case.

On the HBS Online course platform, you’re prompted to view and comment on others’ responses, and discussion is encouraged. This practice of considering others’ perspectives can make you more receptive in your career.

“You’d be surprised at how much you can learn from your peers,” said Ratnaditya Jonnalagadda , a software engineer who took CORe.

In addition to interacting with peers in the course platform, Jonnalagadda was part of the HBS Online Community , where he networked with other professionals and continued discussions sparked by course content.

“You get to understand your peers better, and students share examples of businesses implementing a concept from a module you just learned,” Jonnalagadda said. “It’s a very good way to cement the concepts in one's mind.”

4. Enhance Your Curiosity

One byproduct of taking on different perspectives is that it enables you to picture yourself in various roles, industries, and business functions.

“Each case offers an opportunity for students to see what resonates with them, what excites them, what bores them, which role they could imagine inhabiting in their careers,” says former HBS Dean Nitin Nohria in the Harvard Business Review . “Cases stimulate curiosity about the range of opportunities in the world and the many ways that students can make a difference as leaders.”

Through the case method, you can “try on” roles you may not have considered and feel more prepared to change or advance your career .

5. Build Your Self-Confidence

Finally, learning through the case study method can build your confidence. Each time you assume a business leader’s perspective, aim to solve a new challenge, and express and defend your opinions and decisions to peers, you prepare to do the same in your career.

According to a 2022 City Square Associates survey , 84 percent of HBS Online learners report feeling more confident making business decisions after taking a course.

“Self-confidence is difficult to teach or coach, but the case study method seems to instill it in people,” Nohria says in the Harvard Business Review . “There may well be other ways of learning these meta-skills, such as the repeated experience gained through practice or guidance from a gifted coach. However, under the direction of a masterful teacher, the case method can engage students and help them develop powerful meta-skills like no other form of teaching.”

How to Experience the Case Study Method

If the case method seems like a good fit for your learning style, experience it for yourself by taking an HBS Online course. Offerings span seven subject areas, including:

- Business essentials

- Leadership and management

- Entrepreneurship and innovation

- Finance and accounting

- Business in society

No matter which course or credential program you choose, you’ll examine case studies from real business professionals, work through their challenges alongside peers, and gain valuable insights to apply to your career.

Are you interested in discovering how HBS Online can help advance your career? Explore our course catalog and download our free guide —complete with interactive workbook sections—to determine if online learning is right for you and which course to take.

About the Author

Research Design Review

A discussion of qualitative & quantitative research design, a multi-method approach in qualitative research.

A portion of the following is taken from Applied Qualitative Research Design: A Total Quality Framework Approach (Roller & Lavrakas, 2015, pp. 288-289).

Qualitative multi-method research—due to the additional data collection and analysis considerations—has the potential disadvantage of consuming valuable resources such as time and available research funds. However, this is not always the case and, under the appropriate conditions, multiple qualitative methods can prove very useful toward gaining a more fully developed complexity and meaning in the researcher’s understanding of a subject matter compared to a single-method research design (cf. Denzin & Lincoln, 2011; Flick, 2007).

Ethnography is one such example. Observation is the principal method in an ethnographic study; however, it is often supplemented with other qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews (IDIs), focus group discussions, and/or documentary review in order to provide a more complete “picture” of the issue or phenomenon under investigation. Other applications of multi-method qualitative research are not uncommon. Lambert and Loiselle (2008), for instance, combined focus group discussions and IDIs in a study with cancer patients concerning their “information-seeking behavior.” These researchers found that this multi-method approach enriched the study because one method helped inform the other—for example, group discussions identified relevant questions/issues that were then used in the IDIs—and contributed unique information—for example, the IDIs were effective in obtaining details of patients’ information-seeking processes—as well as contextual clarification—for example, the focus groups were more valuable in highlighting contextual influences on these processes such as the physicians’ preferences or recommendations. Lambert and Loiselle concluded that the multi-method research design “enhanced understanding of the structure and essential characteristics of the phenomenon within the context of cancer” (p. 235).

Research Design Review has published articles on two special types of multiple-method qualitative research— case study and narrative research —each of which is a form of “case-centered” qualitative research, a term coined by Mishler (1996, 1999) and used by others (cf. Riessman, 2008) to denote a research approach that preserves the “unity and coherence” of the research subject throughout data collection and analysis. A six-step approach to case-centered research design is discussed in this article .

Regardless of the particular multi-method design or type of research, a multiple-method approach requires a unique set of qualitative researcher skills. These skills are discussed in this article— “Working with Multiple Methods in Qualitative Research: 7 Unique Researcher Skills.”

Brewer, J., & Hunter, A. (2006). Foundations of multimethod research: Synthesizing styles . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Flick, U. (2007). Designing qualitative research . London: Sage Publications.

Lambert, S. D., & Loiselle, C. G. (2008). Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 62 (2), 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04559.x

Mishler, E. G. (1996). Missing persons: Recovering developmental stories/histories. In R. Jessor, A. Colby, & R. A. Shweder (Eds.), Ethnography and human development: Context and meaning in social inquiry (pp. 73–100). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Mishler, E. G. (1999). Storylines: Craftartitists’ narratives of identity . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Snape, D., & Spencer, L. (2003). The foundations of qualitative research. In J. Ritchie & J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative research practice . London: Sage Publications.

Share this:

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Pingback: Ethnography & the Observation Method: 15 Articles on Design, Implementation, & Uses | Research Design Review

- Pingback: Ethnography: A Multi-method Approach | Research Design Review

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

10 Case Study Advantages and Disadvantages

A case study in academic research is a detailed and in-depth examination of a specific instance or event, generally conducted through a qualitative approach to data.

The most common case study definition that I come across is is Robert K. Yin’s (2003, p. 13) quote provided below:

“An empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident.”

Researchers conduct case studies for a number of reasons, such as to explore complex phenomena within their real-life context, to look at a particularly interesting instance of a situation, or to dig deeper into something of interest identified in a wider-scale project.

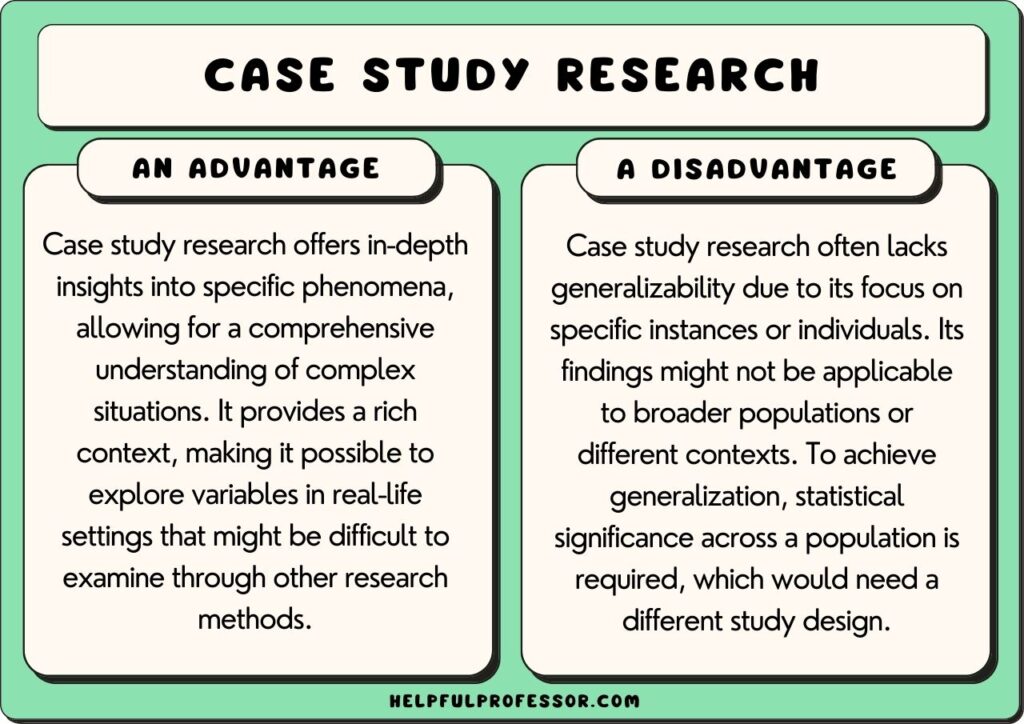

While case studies render extremely interesting data, they have many limitations and are not suitable for all studies. One key limitation is that a case study’s findings are not usually generalizable to broader populations because one instance cannot be used to infer trends across populations.

Case Study Advantages and Disadvantages

1. in-depth analysis of complex phenomena.

Case study design allows researchers to delve deeply into intricate issues and situations.

By focusing on a specific instance or event, researchers can uncover nuanced details and layers of understanding that might be missed with other research methods, especially large-scale survey studies.

As Lee and Saunders (2017) argue,

“It allows that particular event to be studies in detail so that its unique qualities may be identified.”

This depth of analysis can provide rich insights into the underlying factors and dynamics of the studied phenomenon.

2. Holistic Understanding

Building on the above point, case studies can help us to understand a topic holistically and from multiple angles.

This means the researcher isn’t restricted to just examining a topic by using a pre-determined set of questions, as with questionnaires. Instead, researchers can use qualitative methods to delve into the many different angles, perspectives, and contextual factors related to the case study.

We can turn to Lee and Saunders (2017) again, who notes that case study researchers “develop a deep, holistic understanding of a particular phenomenon” with the intent of deeply understanding the phenomenon.

3. Examination of rare and Unusual Phenomena

We need to use case study methods when we stumble upon “rare and unusual” (Lee & Saunders, 2017) phenomena that would tend to be seen as mere outliers in population studies.

Take, for example, a child genius. A population study of all children of that child’s age would merely see this child as an outlier in the dataset, and this child may even be removed in order to predict overall trends.

So, to truly come to an understanding of this child and get insights into the environmental conditions that led to this child’s remarkable cognitive development, we need to do an in-depth study of this child specifically – so, we’d use a case study.

4. Helps Reveal the Experiences of Marginalzied Groups

Just as rare and unsual cases can be overlooked in population studies, so too can the experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of marginalized groups.

As Lee and Saunders (2017) argue, “case studies are also extremely useful in helping the expression of the voices of people whose interests are often ignored.”

Take, for example, the experiences of minority populations as they navigate healthcare systems. This was for many years a “hidden” phenomenon, not examined by researchers. It took case study designs to truly reveal this phenomenon, which helped to raise practitioners’ awareness of the importance of cultural sensitivity in medicine.

5. Ideal in Situations where Researchers cannot Control the Variables

Experimental designs – where a study takes place in a lab or controlled environment – are excellent for determining cause and effect . But not all studies can take place in controlled environments (Tetnowski, 2015).

When we’re out in the field doing observational studies or similar fieldwork, we don’t have the freedom to isolate dependent and independent variables. We need to use alternate methods.

Case studies are ideal in such situations.

A case study design will allow researchers to deeply immerse themselves in a setting (potentially combining it with methods such as ethnography or researcher observation) in order to see how phenomena take place in real-life settings.

6. Supports the generation of new theories or hypotheses

While large-scale quantitative studies such as cross-sectional designs and population surveys are excellent at testing theories and hypotheses on a large scale, they need a hypothesis to start off with!

This is where case studies – in the form of grounded research – come in. Often, a case study doesn’t start with a hypothesis. Instead, it ends with a hypothesis based upon the findings within a singular setting.

The deep analysis allows for hypotheses to emerge, which can then be taken to larger-scale studies in order to conduct further, more generalizable, testing of the hypothesis or theory.

7. Reveals the Unexpected

When a largescale quantitative research project has a clear hypothesis that it will test, it often becomes very rigid and has tunnel-vision on just exploring the hypothesis.

Of course, a structured scientific examination of the effects of specific interventions targeted at specific variables is extermely valuable.

But narrowly-focused studies often fail to shine a spotlight on unexpected and emergent data. Here, case studies come in very useful. Oftentimes, researchers set their eyes on a phenomenon and, when examining it closely with case studies, identify data and come to conclusions that are unprecedented, unforeseen, and outright surprising.

As Lars Meier (2009, p. 975) marvels, “where else can we become a part of foreign social worlds and have the chance to become aware of the unexpected?”

Disadvantages

1. not usually generalizable.

Case studies are not generalizable because they tend not to look at a broad enough corpus of data to be able to infer that there is a trend across a population.

As Yang (2022) argues, “by definition, case studies can make no claims to be typical.”

Case studies focus on one specific instance of a phenomenon. They explore the context, nuances, and situational factors that have come to bear on the case study. This is really useful for bringing to light important, new, and surprising information, as I’ve already covered.

But , it’s not often useful for generating data that has validity beyond the specific case study being examined.

2. Subjectivity in interpretation

Case studies usually (but not always) use qualitative data which helps to get deep into a topic and explain it in human terms, finding insights unattainable by quantitative data.

But qualitative data in case studies relies heavily on researcher interpretation. While researchers can be trained and work hard to focus on minimizing subjectivity (through methods like triangulation), it often emerges – some might argue it’s innevitable in qualitative studies.

So, a criticism of case studies could be that they’re more prone to subjectivity – and researchers need to take strides to address this in their studies.

3. Difficulty in replicating results

Case study research is often non-replicable because the study takes place in complex real-world settings where variables are not controlled.

So, when returning to a setting to re-do or attempt to replicate a study, we often find that the variables have changed to such an extent that replication is difficult. Furthermore, new researchers (with new subjective eyes) may catch things that the other readers overlooked.

Replication is even harder when researchers attempt to replicate a case study design in a new setting or with different participants.

Comprehension Quiz for Students

Question 1: What benefit do case studies offer when exploring the experiences of marginalized groups?

a) They provide generalizable data. b) They help express the voices of often-ignored individuals. c) They control all variables for the study. d) They always start with a clear hypothesis.

Question 2: Why might case studies be considered ideal for situations where researchers cannot control all variables?

a) They provide a structured scientific examination. b) They allow for generalizability across populations. c) They focus on one specific instance of a phenomenon. d) They allow for deep immersion in real-life settings.

Question 3: What is a primary disadvantage of case studies in terms of data applicability?

a) They always focus on the unexpected. b) They are not usually generalizable. c) They support the generation of new theories. d) They provide a holistic understanding.

Question 4: Why might case studies be considered more prone to subjectivity?

a) They always use quantitative data. b) They heavily rely on researcher interpretation, especially with qualitative data. c) They are always replicable. d) They look at a broad corpus of data.

Question 5: In what situations are experimental designs, such as those conducted in labs, most valuable?

a) When there’s a need to study rare and unusual phenomena. b) When a holistic understanding is required. c) When determining cause-and-effect relationships. d) When the study focuses on marginalized groups.

Question 6: Why is replication challenging in case study research?

a) Because they always use qualitative data. b) Because they tend to focus on a broad corpus of data. c) Due to the changing variables in complex real-world settings. d) Because they always start with a hypothesis.

Lee, B., & Saunders, M. N. K. (2017). Conducting Case Study Research for Business and Management Students. SAGE Publications.

Meir, L. (2009). Feasting on the Benefits of Case Study Research. In Mills, A. J., Wiebe, E., & Durepos, G. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (Vol. 2). London: SAGE Publications.

Tetnowski, J. (2015). Qualitative case study research design. Perspectives on fluency and fluency disorders , 25 (1), 39-45. ( Source )

Yang, S. L. (2022). The War on Corruption in China: Local Reform and Innovation . Taylor & Francis.

Yin, R. (2003). Case Study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier Sponsored Documents

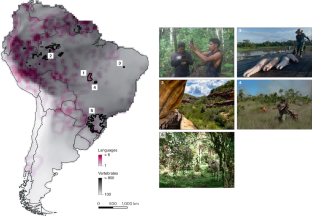

Advantages of the multiple case series approach to the study of cognitive deficits in autism spectrum disorder