Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Assessing desertification in sub-Saharan peri-urban areas: Case study applications in Burkina Faso and Senegal

2018, Journal of Geochemical Exploration

Related Papers

iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry

Agostino Ferrara

Current Perspectives in Contaminant Hydrology and Water Resources Sustainability

Emmanuele gautier

Jesse Ribot

Urban demand for woodfuels in Sudanian and Sahelian West Africa has long been assumed to contribute to permanent deforestation in dryland forests and wooded savannas. Deforestation has also long been assumed to be progressing such that these woodlands will no longer be able to provide the region's cities with fuel. Available studies of regeneration do not support the first assumption. Further, woodfuel shortages projected in the 1980s to arrive in the 1990s or early 2000s are nowhere near, while more recent projections predict supply shortages another twenty-five years hence. While there is deforestation from many causes, the data do not support crisis scenarios concerning woodfuels. Nonetheless, crisis scenarios and policies persist. While there may yet be deforestation due to urban woodfuel extraction, and shortages may be lurking on the horizon, the article explores some possible alternative origins of these woodfuel related deforestation and shortage fears.

Global Ecology and Biogeography

The Re-Greening of the West African Sahel has attracted great interdisciplinary interest since it was originally detected in the mid-2000s. Studies have investigated vegetation patterns at regional scales using a time series of coarse resolution remote sensing analyses. Fewer have attempted to explain the processes behind these patterns at local scales. This research investigates bottom-up processes driving Sahelian greening in the northern Central Plateau of Burkina Faso—a region recognized as a greening hot spot. The objective was to understand the relationship between soil and water conservation (SWC) measures and the presence of trees through a comparative case study of three village terroirs, which have been the site of long-term human ecology fieldwork. Research specifically tests the hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between SWC and tree cover. Methods include remote sensing of high-resolution satellite imagery and aerial photos; GIS procedures; and chi-square ...

The vegetation, water and open spaces within and around African cities provide many benefits for their inhabitants. Without this “green infrastructure” our cities would be hotter, more uncomfortable, more prone to flooding, produce less food, and be less attractive places to live, work, visit and invest. Yet across African cities we are witnessing a loss of this green resource – and of the associated benefits – through rapid development and inadequate planning. It is now time for planners and decision makers to plan effectively for this infrastructure, in recognition of the essential role it plays in the sustainable and climate conscious development of all urban areas. This information note can help with this process. It draws upon findings from a three year research project called CLUVA (CLimate change and Urban Vulnerability in Africa; www.cluva.eu), which has been conducted with universities and practitioners from across the African continent. It sets out: - An introduction to gr...

Louise Simonsson

Jonathan Chukwujekwu Onyekwelu

Antoine Cornet

Julie L Snorek

The Sahelian countries (CILSS) are among the poorest countries in the world with the most degraded environments. They are also among the countries that are the most vulnerable to the estimated effects of climate change. This makes the region an area to focus regional and international attention on, in respect to the possible effects of climate change and its potential linkages to migration and/or conflict. UNEP’s study focuses on the nine countries that form the Permanent Inter-State Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel (Comité Permanent Inter-Etats de Lutte contre la Sécheresse dans le Sahel, CILSS), namely, Senegal, Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde, Mauritania, Mali, Chad, Niger, Gambia and Burkina Faso. Part of CILSS’s mandate is to direct efforts towards natural resources management and food security. The study seeks to: 1) identify how and where climate change exacerbates existing vulnerabilities in the Sahel;2) analyze its potential links to conflict and/or migration; 3) assess current policies that address the climate, conflict and migration nexus, and raise awareness, catalyze support; and finally, 4) inform investments to meet emerging climate change adaptation needs.

RELATED PAPERS

Sustainability

Arnaud Zida

Emmanuel Ifeanyi Ofoezie

cheikh gueye

George F Taylor II

European Scientific Journal ESJ

Jonas KOALA

Pierre Hiernaux

Antoine Kalinganire

Abel Kadeba

Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography

Elvire Eijkman

Adjima Thiombiano

Annals of Forest Research

Blandine Nacoulma

International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences

Barkissa Fofana

Leonard Amekudzi

Agricultural Systems

Kjeld Rasmussen

Raf Aerts , Aklilu Negussie

Dominique Masse

Sensors (Basel, Switzerland)

Saber Hafid

Ruerd Ruben

Just Dengerink

aboubacar coulibaly

Verina Ingram

Environment International

Philippe Lavigne Delville , Claude Raynaut

Property Rights, Risk, and Livestock Development in …

Nancy McCarthy

Georges Félix

Anna Tengberg

Hydrological Processes

Olivier Ribolzi

Martial Bernoux

Revue d'élevage et de médecine vétérinaire des pays tropicaux

Mathieu Ouedraogo

Journal of Arid Environments

Souleymane Ganaba

Agronomy for Sustainable Development

Cathy Clermont-dauphin

micle working paper no. 1

Martin Doevenspeck

The Open Hydrology Journal

Lekan Oyebande

EDMUND MABHUYE

Antoine Kalinganire , Fergus Sinclair , D. Garrity , Z. Tchoundjeu

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Advertisement

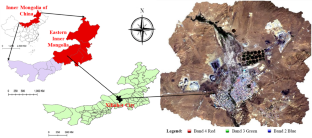

Study of the desertification index based on the albedo-MSAVI feature space for semi-arid steppe region

- Original Article

- Published: 22 March 2019

- Volume 78 , article number 232 , ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Zhenhua Wu 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Shaogang Lei 2 , 3 ,

- Zhengfu Bian 2 , 3 ,

- Jiu Huang 2 , 3 &

- Yong Zhang 4

1295 Accesses

47 Citations

Explore all metrics

Desertification has been listed as the top of ten major problems affecting global environmental changes, and represents one of the important reasons of semi-arid grassland degradation. It is therefore crucial to understand ecological environment of semi-arid grasslands and temporal and spatial changes in real time for regional and local environmental protection and management. At present, remote sensing technology is being widely used in monitoring and evaluation of land desertification due to its wide observation range, large amount of information, fast data updating and high accuracy. It represents an advanced method for remote sensing monitoring of desertification by extracting various indicators and constructing feature space. Based on this, this study used Landsat images and field survey data to establish a desertification index (SASDI) model based on the albedo-MSAVI (Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index) feature space and analyze the relationship between desertification and surface quantitative parameters in semi-arid grassland area. Results show that the SASDI model has a high correlation ( R 2 = 0.7585) with the organic matter in the soil surface and makes full use of multi-dimensional remote sensing information. The index reflects the surface cover, water, and heat combination as well as changes of the desertification land, with a clear biophysical significance. Moreover, the index is simple and easy to obtain, facilitating to quantitative analysis and continuous monitoring of desertification in semi-arid grasslands.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

An overview of land degradation, desertification and sustainable land management using GIS and remote sensing applications

Mohamed A. E. AbdelRahman

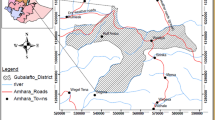

Analysing land use/land cover changes and its dynamics using remote sensing and GIS in Gubalafito district, Northeastern Ethiopia

Gebeyehu Abebe, Dodge Getachew & Alelgn Ewunetu

Predicting urban growth and its impact on fragile environment using Land Change Modeler (LCM): a case study of Djelfa City, Algeria

Amar Benkhelif, M’hammed Setti, … Islam Nazrul

Becerril-Piña R, Díaz-Delgadoa C, Mastachi-Loza CA, González-Sosa E (2016) Integration of remote sensing techniques for monitoring desertification in Mexico. Hum Ecol Risk Assess 22(6):1323–1340

Article Google Scholar

Burke IC, Laurenroth WK, Milchunas DG (1997) Biogeochemistry of managed grasslands in central North America. In: Paul EA (ed) Soil organic matter in temperate agroecosystems: long-term experiments in North America. CRC, Boca Raton, pp 85–102

Google Scholar

Capozzi F, Di Palma A (2018) Assessing desertification in sub-Saharan peri-urban areas: case study applications in Burkina Faso and Senegal. J Geochem Explor 190:281–291

Charney J, Stone PH, Quirk WJ (1975) Drought in the sahara: a biogeophysical feedback mechanism. Science 187(4175):434

Crist EP, Cicone RC (1984a) Application of the Tasseled Cap concept to simulated thematic mapper data. Photogramm Eng Remote Sens 50(3b):343–352

Crist EP, Cicone RC (1984b) A physically-based transformation of thematic mapper data—the TM Tasseled Cap. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens 22(3a):256–263

D’Odorico P, Bhattachan A, Kyle F, Davis KF, Ravi S, Runyan CW (2013) Global desertification: drivers and feedbacks. Adv Water Resour 51:326–344

Del Valle HF, Elissalde NO, Gagliardini DA et al. Status of desertification in the Patagonian region: assessment and mapping from satellite imagery. Arid Soil Res Rehabilit 1998, 12(2): 95–121

Deng C, Wu C (2012) BCI: a biophysical composition index for remote sensing of urban environments. Remote Sens Environ 127(5):247–259

Development Planning Department of Agriculture (2002) National grassland ecological construction planning. Agriculture Press, Beijing

Dickinson RE (1995) Land processes in climate models. Remote Sens Environ 51(1):27–38

Ding J, Juan QU, Yongmeng S et al (2013) The retrieval model of soil salinization information in arid region based on MSAVI-WI feature space: a case study of the delta oasis in Weigan-Kuqa watershed. Geogr Res 32(2):223–232

Ding J, Yuan Y, Fei W (2014) Detecting soil salinization in arid regions using spectral feature space derived from remote sensing data. Acta Ecol Sin 34(16):4620–4631

Feng Y, Wang Y (2009) Estimated of soil moisture from Ts-EVI feature space. Acta Ecol Sin 29(9):4884–4891

Gao Y, Xingguo H, Shiping W (2004) The effects of grazing on grassland soils. Acta Ecol Sin 24(4):790–797

Gillies RR, Carlson TN, Cui J, Kustas WP, Humes KS (1997) A verification of the ‘triangle’ method for obtaining surface soil water content and energy fluxes from remote measurements of the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and surface radiant temperature. Int J Remote Sens 18(15):3145–3166

Gitelson AA, Kaufman YJ, Stark R, Rundquist D (2002) Novel algorithms for remote estimation of vegetation fraction. Remote Sens Environ 80(1):76–87

Guan Y (2015) Global desertification index building and desertification trend analysis based on remote sensing image. University of electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu

Guangyin HU, Zhibao D, Junfeng LU et al (2015) The developmental trend and influencing factors of aeolian desertification in the Zoige Basin, eastern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Aeol Res 19:275–281

Gülersoy AE (2013) Farkli uzaktan algilama teknikleri kullanilarak arazi örtüsü/kullaniminda meydana gelen değişimlerin incelenmesi: manisa merkez ilçesi örneği (1986–2010). Turk Stud Int Period Lang Lit Hist Turk Turk 8(8):1915–1934 (ANKARA–TURKEY)

Jingfeng X, Aaron M (2005) A comparison of methods for estimating fractional green vegetation cover within a desert-to-upland transition zone in central New Mexico, USA. Remote Sens Environ 98(2–3):237–250

Khan NM, Sato Y (2001) Monitoring hydro-salinity status and its impact in irrigated semi-arid areas using IRS-1B LISS-II data. Asian J Geoinform 1(3):63–73

Lecain DR, Morgan JA, Schuman GE et al (2002) Carbon exchange and species composition of grazed pastures and exclosures in the shortgrass steppe of Colorado. Agric Ecosyst Environ 93(1):421–435

Li M (2003) The method of vegetation fraction estimation by remote sensing. Beijing: Institute of remote sensing applications of the Chinese Academy of Sciences

Li J (2011) The response of vegetation-soil-soil fauna to desertification in the western of Ordos Plateau. Northeast Normal University, Changchun

Li J (2014) Spatio-temporal variations and its driving factors of the grassland sandy desertification in the horqin sand land based on remote sensing. Beijing: Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences Dissertation

Li SG, Harazono Y, Oikawa T et al (2000) Grassland desertification by grazing and the resulting micrometeorological changes in Inner Mongolia. Agric For Meteorol 102(2–3):125–137

Li M, Bingfang WU, Changzhen Y, Weifeng Z (2004) Estimation of vegetation fraction in the upper basin of miyun reservoir by remote sensing. Resour Sci 26(4):153–159

Li SG, Eugster W, Asanuma J, Kotani A, Davaa G, Oyunbaatar D, Sugita M (2006) Energy partitioning and its biophysical controls above a grazing steppe in central Mongolia. Agric For Meteorol 137(1):89–106

Li J, Y Xiuchun, J Yunxiang et al (2013) Monitoring and analysis of grassland desertification dynamics using Landsat images in Ningxia, China. Remote Sens Environ 138(6):19–26

Li N, Yan CZ, Xie JL (2015a) Remote sensing monitoring recent rapid increase of coal mining activity of an important energy base in northern China, a case study of Mu Us Sandy Land. Resour Conserv Recycl 94(94):129–135

Li Y, Jianli D, Yongmeng S et al (2015b) Remote sensing monitoring models of soil salinization based on the three dimensional feature space of MSAVI-WI-SI. Res Soil Water Conserv 4:113

Liang S (2001) Narrowband to broadband conversions of land surface albedo I: algorithms. Remote Sens Environ 76(2):213–238

Lin YH, Mengli GZ et al (2010) Spatial vegetation patterns as early signs of desertification: a case study of a desert steppe in Inner Mongolia, China. Landsc Ecol 25(10):1519–1527

Liu Yun S, Danfeng Yu, Zhenrong et al (2008) Water deficit diagnosis and growing condition monitoring of winter wheat based on NDVI-Ts feature space. Trans CSAE 24(5):147–151

London National Strategy For Sustainable, Unep Nairobi (1994) United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification in Countries Experiencing Serious Drought and/or Desertification, particularly in Africa

Mcfeeters SK (1996) The use of the normalized difference water index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int J Remote Sens 17(7):1425–1432

Pan J, Li T (2013) Extracting desertification from Landsat TM imagery based on spectral mixture analysis and albedo-vegetation feature space. Nat Hazards 68:915–927

Percival HJ, Parfitt RL, Scott NA (2000) Factors controlling soil carbon levels in New Zealand grassland: is clay content important?. Soil Sci Soc Am J 64(5):1623–1630

Poitras TB, Villarreal ML, Waller EK et al (2018) Identifying optimal remotely-sensed variables for ecosystem monitoring in Colorado Plateau drylands. J Arid Environ 153:76–87

Potter GL, Ellsaesser HW, Maccracken MC et al (1981) Albedo change by man: test of climatic effects. Nature 291(5810):47–49

Qi J, Chehbouni A, Huete AR et al (1994) A modified soil adjusted vegetation index. Remote Sens Environ 48(2):119–126

Ridd MK (1995) Exploring a V-I-S (vegetation-impervious surface-soil) model for urban ecosystem analysis through remote sensing: comparative anatomy for citiesâ. Int J Remote Sens 16(12):2165–2185

Robert KG, Running SW (1993) Community type differentiation using NOAA/AVHRR data within a sagebrush-steppe ecosystem. Remote Sens Environ 46(3):311–318

Röder A, Hill J et al. (2008) Trend analysis of Landsat-TM and -ETM + imagery to monitor grazing impact in a rangeland ecosystem in Northern Greece. Remote Sens Environ 112(6):2863–2875

Rouse JW, Haas RH, Schell JA et al (1973) Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. Nasa Spec Publ 351:309

Sagan CT, Owen B, Pollack JB (1979) Anthropogenic albedo changes and the earth’s climate. Science 206(4425):1363

Sommer S, Zucca C, Grainger A et al (2011) Application of indicator systems for monitoring and assessment of desertification from national to global scales. Land Degrad Dev 22(2):184–197

Sui X, Qiming Q et al (2013) Monitoring of farmland drought based on LST-LAI spectral feature space. Spectrosc Spectr Anal 33(1):201

Tucker CJ, Newcomb WW (1991) Expansion and contraction of the sahara desert from 1980 to 1990. Science 253(5017):299–300

Verstraete MM, Pinty B (1996) Designing optimal spectral indexes for remote sensing applications. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens 34(5):1254–1265

Verstraete MM, Scholes RJ Smith MS (2009) Climate and desertification: looking at an old problem through new lenses. Front Ecol Environ 7(8):421–428

Wang G, Hu Z, Du H et al (2006) Analysis of grassland desertification due to coal mining based on remote sensing——an example from huolinhe open-cast coalmine. J Remote Sens 10(6):917–925

Wang F, Ding J, Wu M (2010) Remote sensing monitoring models of soil salinization based on NDVI-SI feature space. Trans CSAE 26(8):168–173

Wei H, Zongwei H et al (2015) Spatial distribution of soil organic matter based on topographic unit. Trans Chin Soc Agric Mach 4:161–167

William H, Schlesinger JF, Reynolds GL et al (1990) Biological feedbacks in global desertification. Science 247(4946):1043–1048

Wu CL, Gaohuan L et al (2016) The spatial distribution of soil organic matter on the north-central Mongolian Plateau. Resour Sci 38(5):994–1002

Xiongde M, Limin F, Xiaotuan Z et al (2016) Dynamic change of land desertification and its driving mechanism in Yushenfu mining area based on remote sensing. J China Coal Soc 41(8):2063–2070

Xu H (2010) Analysis of impervious surface and its impact on urban heat environment using the normalized difference impervious surface index (NDISI). Photogramm Eng Remote Sens 76(5):557–565

Xu D, Ding X (2018) Assessing the impact of desertification dynamics on regional ecosystem service value in North China from 1981 to 2010. Ecosyst Serv 30:172–180

Xu H et al. (2005) A study on information extraction of water body with the modified normalized difference water index (MNDWI). J Remote Sens 9(5):589–595

Xueping HA, Jianli D, Tiyip T et al (2009) SI-albedo space-based remote sensing synthesis index models for monitoring of soil salinization. Acta Pedol Sin 46(4):698–703

Yuan MX, Zou L, Lin AW, Zhu HJ (2016) Analyzing dynamic vegetation change and response to climatic factors in Hubei Province, China. Acta Ecol Sin 36(17):5315–5323

Zeng Y, Feng Z et al (2006) Albedo-NDVI space and remote sensing synthesis index models for desertification monitoring. Sci Geogr Sin 26(1):75–81

Zha Y, Gao Y, Ni S (2003) Use of normalized difference built-up index in automatically mapping urban areas from TM imagery. Int J Remote Sens 24:583–594

Zhao M, Ganlin Z et al (2013) Spatial variability of soil organic matter and its dominating factors in Xu-Huai Alluvial Plain. Acta Pedol Sin 50(1):1–11

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Seventh Project “The National Key Research and Development Program of China 2016YFC0501107”, “National Natural Science Foundation of China U1710120” and “National key projects for basic science and technology work of China 2014FY110800”.

This research was funded by (Key Technologies of Landscape Ecological Restoration of Large-scale Coal-power Bases) Grant number (2016YFC0501107), National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1710120) and National key projects for basic science and technology work of China (2014FY110800).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Land and Resources, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, 221116, China

Ministry of Education Engineering Research Center for Mine Ecological Restoration, Xuzhou, 221116, China

Zhenhua Wu, Shaogang Lei, Zhengfu Bian & Jiu Huang

School of Environment Science and Spatial Informatics, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, 221116, Jiangsu, China

School of Finance and Public Management, Anhui University of Finance and Economics, Bengbu, 233030, Anhui, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Zhengfu Bian .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wu, Z., Lei, S., Bian, Z. et al. Study of the desertification index based on the albedo-MSAVI feature space for semi-arid steppe region. Environ Earth Sci 78 , 232 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-019-8111-9

Download citation

Received : 29 August 2018

Accepted : 28 January 2019

Published : 22 March 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-019-8111-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Feature space

- Desertification index

- Remote sensing monitoring

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Beating back the desert: the case of Burkina Faso

- PMID: 12157787

PIP: The views of a geographer, agricultural scientist, and women's activist focused on the importance of improving women's status and involvement in development. Women in Burkina Faso have shown an ability to organize themselves, but there was insufficient coordination among aid organizations. Researchers and development professionals must broaden and deepen their knowledge about climate, farming methods and traditional natural resource management methods, and women's concerns and occupations. Women need to be engaged in the planning and implementation of natural resource management strategies and in learning about appropriate training and information dissemination methods. The expertise in environmental disciplines is concentrated in developed nations and is needed by Sahelian women. Burkina's environment is replete with droughts, lack of forested areas, and dependence on subsistence farming. Famine and mass migration of men to urban areas have left women in poverty. Women must work 14-16 hours a day to provide food for their families and help husbands with cash crops. About 25% of women die from malnutrition, anemia, repeated pregnancies, malaria, and overexertion, as reported in a 1987 UNICEF study. The literature on women in Burkina Faso has focused only on broad issues of women's status. The few studies of local conditions conducted on a small scale by nongovernmental organizations have revealed that women were 60-80% of the labor force on anti-desertification projects. Women's overwhelming work load prevented even greater participation in environmental protection. Property laws gave land titles to men or the state. Women's groups have set up cereal banks, village pharmacies, and other self help projects pertaining to health, the environment, and agriculture. Women in development individual programs have not sufficiently integrated women and programs were archaic and dispersed. Environmental enforcement was limited.

Publication types

- Case Reports

- Africa South of the Sahara

- Africa, Northern

- Africa, Western

- Burkina Faso

- Community Participation*

- Developing Countries

- Environment

- Evaluation Studies as Topic*

- Health Facilities, Proprietary*

- Organization and Administration

- Socioeconomic Factors

- Women's Rights*

- Get involved

- Case Studies for the RFS Catalytic Grant Projects: Burkina Faso pdf (1.4 MB)

Case Studies for the RFS Catalytic Grant Projects: Burkina Faso

March 21, 2024.

Under the Resilient Food System (RFS) Programme , UNDP and AGRA co-designed three catalytic grant projects to pilot innovative approaches and model projects to showcase and develop practical methodologies of promoting Green Value Chain Development in East, Southern and West Africa.

In Burkina Faso, the catalytic grant project “ Fostering Climate-Resilient Agriculture for Resilient Maize Production Systems for Small-Scale Producers in Burkina Faso (FARMS – BF) ” aimed to support the development of a resilient maize value chain. INERA (Burkina Faso’s National Agriculture Research Organization), the catalytic grant awardee, developed and released 30 high-yielding, climate-smart (drought, pest, diseases tolerant) and high nutritional (high protein, provitamin A) maize varieties that are suited to the local social and agroecological conditions. The project connected small-scale producers to the input supply chain systems. To reach the optimum yield of the varieties, the project promoted the adoption of good agronomic practices such as integrated soil fertility management, compost application and postharvest management.

This case study documents the process of the implementation of the catalytic grant project. It puts together key lessons, success and/or failure factors, and outlines the project results as part of the process of documenting and disseminating information that can be used by multiple stakeholders including policy and decision-makers, project developers, funding agencies, and the private sector for widescale application of greening principles in food systems particularly in response to the challenges and impacts of climate change and environmental degradation.

Document Type

Regions and countries, related publications.

Publications

Case studies for the rfs catalytic grant projects: malawi.

Under the Resilient Food System (RFS) Programme, UNDP and AGRA co-designed three catalytic grant projects to pilot innovative approaches and model projects to s...

Case Studies for the RFS Catalytic Grant Projects: Tanzan...

Under the Resilient Food System (RFS) Programme, UNDP and AGRA co-designed three catalytic grant projects to pilot innovative approaches and model projects to s...

Online Gender-Based Violence Among Women and Girls In Zam...

An Assessment of the Nature, Extent and Effects of Online Gender Based Violence among Women and Girls in Zambia

Road Safety in Zambia — Investment Case

This investment case on Road Safety in Zambia presents a compelling case for action. Road traffic accidents not only claim more than 2,100 Zambian lives annuall...

The Impact Assessment of the Energy Vulnerability Reducti...

A series of three policy briefs focused on assessing the impact of the Energy Vulnerability Reduction Fund (EVRF) was conducted.

ADDRESSING THE DRIVERS AND CAUSES OF VULNERABILITY IN MIG...

To address the drivers and causes of these migration-related vulnerabilities and to enhance the cross-border trade environment along the Trans Gambia transport ...

Case Study: Sahel Desertification

What is desertification: It is the term used to describe the changing of semi arid (dry) areas into desert. It is severe in Sudan, Chad, Senegal and Burkina Faso

What are the causes:

- Overcultivation: the land is continually used for crops and does not have time to recover eventually al the nutrients are depleted (taken out) and the ground eventually turns to dust.

- Overgrazing: In some areas animals have eaten all the vegetation leaving bare soil.

- Deforestation: Cutting down trees leaves soil open to erosion by wind and rain.

- Climate Change: Decrease in rainfall and rise in temperatures causes vegetation to die

What is being done to solve the problem?

Over the past twelve years Oxfam has worked with local villagers in Yatenga (Burkina Faso) training them in the process of BUNDING. This is building lines of stones across a slope to stop water and soil running away. This method preserves the topsoil and has improved farming and food production in the village.

Burkina Faso - desertification

This video shows the Sahel region south of the Sahara is at risk of becoming desert. Elders in a village in Burkina Faso describe how the area has changed from a fertile area to a drought-prone near-desert. The area experiences a dry season which can last up to eight or nine months. During this time rivers dry up and people, animals and crops are jeopardised.

This video showcases the Sahel region

Living World - Desertification Strategies

Strategies used to reduce the risk of desertification Desertification is not inevitable and with careful management of water resources, the soil and vegetation via tree planting we can limit the spread of deserts. We have even managed to reverse the effects of desertification. Many of the techniques used have used appropriate technology, which is suited to the needs, skills, knowledge and wealth of local people in the environment which they live.

Tree Planting - Senegal In the Senegal region of the Sahel (a 5,000km long belt of land that separates the Southern part of Africa from the Sahara) the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the UN is trying to help in the fight against desertification. Less than 50 years ago land in this region of the Sahel was productive Savannah, but is now dry desert because of decades of climate change and over intensive farming, forestry and land degradation. This has led to vegetation disappearing. A project focussing on Acacia or gum trees is trying to help. The FAO and forestry service have provided nursery’s to grow seeds and seedlings. The locals were also taught how to sow and plant the Acacia trees, and how to extract and market the gum they produce. They were also given a tractor and digger tool specially adapted to dryland conditions. It cuts half moon shaped holes which collect rainwater ensuring that the young plant roots will have enough water to survive the long dry season. This also massively reduces the amount of labour needed.

An Acacia nursery

Planting the trees reverses desertification by preventing soil erosion and providing nutrients for other plants and crops to grow. The tree is a native tree, it puts nutrients back into the soil, provides shelter for crops under its branches and provides fodder for livestock. The knock on effects have been good for the whole community.

Tractor ploughing crescents

The Great Green Wall The Great Green wall is a planned project to plant trees across Africa along the southern edge of the Sahara Desert to prevent the desert spreading south. It has been developed by the African Union to reduce the negative effects of desertification and land degradation on people, the environment and the economies of the countries affected.

Stone lines – Water and soil management

Desertification leads to outmigration in countries such as Burkina Faso in the Sahel. This idea was to lay stones along the contours of the land in long lines which traps the rainwater that falls. A contour stone line 25 to 30cm high with other stones behind is constructed. These stones slow down run off water and allow it time to infiltrate the ground and rich sediments to be trapped in the field. This results in less erosion and more water for the crops. Farmers were trained in laying out contours using a simple water tube level. They marked out the contours and dug out a foundation trench. Large stones are then placed into this trench followed by smaller ones. Grasses can also be planted along the barrier. The villagers work together and it is a collective effort. The technique has spread from Burkina Faso to Mali and Niger. It is a technology that is low cost and requires skills that can be quickly learned. Planting pits are also used to hold more water around the plant and homemade compost is used to provide a fertility boost for the soil. Barren land has been restored and vegetation re-established so the scheme has been a big success and sustained.

NEXT UNIT - GCSE - Physical landscapes in the UK GCSE - Challenge of Natural Hazards GCSE - Urban Issues and Challenges GCSE - Challenge of Resource Management GCSE - Changing Economic World

©2015 Cool Geography

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy & Cookies

- Testimonials

- Feedback & support

The Burkina Faso case study

General methodology

The Burkina case study research followed the basic Land Settlement Review (LSR) model. 1 The case study was based on a blend of quantitative and qualitative research at four study sites - the AVV (Autorité pour l'Aménagement des Vallées des Volta, or Volta Valley Authority) planned settlements in the upper Nakambe (ex-White Volta) [1] river basin, spontaneous settlement in the southwest "cotton boom" area of Solenzo [2] in the Mouhoun (ex-Black Volta) river basin, spontaneous settlement [3] in the area surrounding the newly created hydroelectric dam in the Kompienga river basin [4], and spontaneous settlement into the Niangoloko subsector and the neighbouring Classified Forest at Toumousseni near the Leraba and Comoe river basins (Figure 2). The interviews with study farmers revolved around four surveys:

1. frequent visitation surveys of crop, livestock, and non-farm production activities for 25 to 35 households at three of the four sites (excluding Niangoloko); 2. a structured interview with 25 to 35 households at each site regarding their immigration history and historic relationships with the indigenous hosts and immigrant agriculturalists and pastoralists; 3. a structured interview with 25 to 35 women at each of the study sites relating to their activities before and after coming to the site; and 4. a series of sample questions to be used as guidelines in the development of a brief history of natural resource management issues.

The Rapid Assessment Procedure

In the original LSR methodology, it was assumed that analysis of immigration trends could be based on existing data. An inventory of existing physical and socioeconomic data for the OCP river basins was summarized in a four-volume Preparatory Phase Study conducted by Hunting Technical Services Limited [6]. The 1985 national census for Burkina provided information on interregional population trends [6-28]. More specific information on the OCP river basins was obtained from an aerial photo survey. This particular survey, commissioned by the OCP as part of a ten-year assessment of the socioeconomic impact of control, compared aerial photos of a sub-sample of the major river basins in 1983 with baseline photographs from 1974 [5]. This OCP study provided the first concrete information on the relative rates and patterns of settlement in the different river basins.

While the OCP aerial photo survey and the 1985 national census were very useful, they did not provide the type of up-to-date information needed on intraregional and interregional immigration. The majority of the printed analyses were aggregated at the administrative province level or in the smaller, more numerous, administrative departments. As such, they did not examine more specific immigration within regions to areas adjacent to the river basins. When these intraregional immigration trends were examined, by comparing the 1975 and 1985 census figures for specific villages, we encountered other problems. For example, some villages with sizeable populations in 1985 did not even exist as official villages in 1975. In another case, a newly created administrative department had not inherited all of the old census records.

Figure 2. Case study research sites in Burkina Faso

Source: McMillan, D., J.B. Nana and K. Savadogo, 1990 [9].

More accurate information was available for the AVV planned settlements at Rapadama and Linoghin. Here, sociologists working with the AVV extension staff developed a simple one-line interview format that sought basic information about year of immigration, area of origin, and the means by which the spontaneous settlers moving into the surrounding area had acquired new land [29]. Some of the same sociologists and research assistants used a similar form to study spontaneous immigration into the Kompienga river basin 0. B. Nana, personal communication) [30].

The LSR Rapid Assessment Procedure

A similar, simple interview format was adopted to study immigration trends at the study sites where accurate immigration data were not available. The sites studied included the Solenzo subsector, the Niangoloko subsector, four villages around the Classified Forest at Toumousseni, and Kompienga, a town that developed at the construction site of the Kompienga Dam.

At Niangoloko, Toumousseni, and Solenzo, village leaders were asked to identify all of the households within a particular geographical unit of the village who were identified as "immigrant." Since all but a small nucleus of the settlement at Kompienga had immigrated since 1985 and had never been counted, we attempted to conduct a fairly accurate census of the entire population. Leaders were asked the approximate year when members of a family unit first immigrated, where they came from, approximate family size, and the household head's primary and secondary occupation. These village leaders were often interviewed in a group setting, which allowed them to cross-validate information.

An average of one month of research assistant's time was required to conduct the rapid assessment procedure at each of the major study sites. One week was required for the four villages adjacent to the Classified Forest at Toumousseni because of the low rates of immigration to the area.

SOLENZO Immigration to the areas adjacent to the Mouhoun (ex-Black Volta) river basin in southwestern Burkina Faso was already well under way when the Onchocerciasis Control Programme began in 1974 [31] (Figure 3). This may be attributed to the extremely successful cotton extension programme that has been promoted in Burkina's upper southwest since the 1950s.

This strong current of immigration toward the prosperous cotton boom areas has continued. Census figures showed that the Solenzo population more than doubled between 1975 and 1985; 38% of this population increase was attributed to immigration. The aerial photo survey showed a striking six-fold increase in new lands cleared for the entire Monhoun (ex-Black Volta) river basin between 1974 and 1984 [5]. This continuous stream of immigration, coupled with the extensive cultivation practices used by most migrants, is putting stress on area soils. Planners are especially concerned about a potential decline in soil fertility caused by decreases in soil organic matter [32]. More intensive cultivation practices, using manure and the reincorporation of crop residues, have enjoyed only limited success; mineral fertilizer is expensive and is used primarily on the cotton and maize grown for sale [9, 32-34].

Current efforts to promote the development of more intensive, environmentally sustainable crop and livestock production practices focus on the development of village land management associations. A core premise of the village land management concept or PNGTV (Programme Nationale pour le Gestion des Terroirs Villageois) is that spontaneous immigrants tend to use extensive cultivation practices because they have insecure land tenure rights. The PNGTV programme hopes to counter this trend by delineating village boundaries and establishing village land management committees to control access to and use of village lands. Other policy innovations include restricting the total area that farmers are allowed to cultivate, promoting new intensive extension themes, and stricter regulation of the terms under which new migrants may occupy village lands.

The PNGTV model is considered relevant to the entire Solenzo region. The results of the farming census survey and rapid assessment survey suggest, however, that receptivity to the programme will be very different in the older villages away from the Mouhoun River and in those along the river basin's edge.

Our best evidence for this is in the recorded differences in the total area farmed and net crop income per active worker for the mini-tractor farmers at the two villages in the farming systems survey [33,34]. The mini-tractor farmers at Dar-es-Salaam/Kie, the village closest to the river basin, farmed an area per active worker that was one-and-a-half times the average area per active worker for mini-tractor farmers in the more inland village of Daboura [9, 34]

Daboura, located along the main highway linking the provincial capital Dedougou with Solenzo, was one of the first villages to experience extensive immigration - much of it before 1974. Dar-es-Salaam possesses a vast uninhabited bush between the core village and the Mouhoun (ex-Black Volta) River; Daboura does not. Because of this large supply of "new" land, the Dares-Salaam settlers and hosts can still expand toward the river. In contrast, the Daboura farmers have little choice but to raise crop productivity through increased use of fertilizer and labour or move to villages like Dar-es-Salaam/Kie where "new" land is still available.

The rapid assessment approach showed that over 46% of the recorded immigrant households (51% if one excludes immigration to the commercial centre of Solenzo) were concentrated in five villages in the vicinity of Dar-es-Salaam. The vast majority of this immigration has occurred since 1974. The incentive to invest in more sustainable crop, livestock and forestry management practices is likely to be less in these five villages adjacent to the river basins. Here "new" land that can be easily cleared is generally still available. These areas are also usually less accessible, with little, if any, basic infrastructure or support services. Efforts to promote sound environmental management are likely to be more successful in these villages when they are linked with a strong concerted effort to work with settlers and hosts to develop roads and services that will be beneficial to both groups. These improved services raise rural living standards and create an incentive to invest before land shortages leave no other option.

These findings had a significant impact on the willingness of national government, regional political and development authorities to support a pilot project to expand the AVV's development programmes to include spontaneous as well as sponsored settlers. This experimental programme was first tried at Linoghin and Rapadama, for the obvious reason that these were the two settlement groups that had experienced the highest rates of new land settlement [29]. A similar programme to incorporate the spontaneous settlers at Mogtedo and Mogtedo-Bombore was initiated in 1989 (Figure 4).

KOMPIENGA There was very little spontaneous immigration to the isolated Kompienga river basin in the southernmost part of the Gourma province until 1982. Living in small, scattered, low-density settlements, the indigenous Gourmantche and Yarse had generally shunned cultivation near the fly-ridden, low-lying rivers [30]. Nevertheless, it was obvious that this situation would change once the government constructed the country's first hydroelectric dam on the Togo-Burkina border (Figure 5). Based on the 1985 census, demographers predicted that construction of the Kompienga dam would briny about a 15% increase in immigration to the Fada planning area between 1985 and 1990,15% between 1990 and 1995, and 8% between 1995 and 2000 [28].

While this 15% figure between 1985 and 1990 might be valid for the province as a whole, it is an inadequate depiction of the sudden influx that occurred in the valley itself. The entire Kompienga river basin experienced a sudden, dramatic increase in agricultural immigration after 1985. This immigration was especially important in the area immediately adjacent to the dam construction site, which became Kompienga town.

By August 1989, when the rapid assessment census was conducted, the town of Kompienga, previously consisting of only three large compounds in the early 1980s, numbered 3,239 persons, excluding civil servants. Only 63 (15%) of the heads of household indicated that they had worked on the dam project, and 310 (75%) of the household heads reported that either agriculture or livestock production was their primary activity. In short, although government officials still thought of the community as essentially one of unemployed former dam employees, the census and case study interviews showed that subsequent immigration had created a new community attracted to the area by the prospect of acquiring irrigated farmland near the dam.

By 1989, virtually the entire area within a ten kilometre radius of the town of Kompienga had been occupied. The farming systems survey confirmed interviews with farmers and extension staff that described the settlers' extensive farming systems. Even if farmers wanted to farm more intensively, this was difficult. Neither extension services, nor plows, nor fertilizer were available to the town farmers. In contrast to the town of Kompienga, the villages that were to be either totally or partially flooded by the dam-created lake had access to fertilizer, plows and extension services through a well organized relocation programme.

These high rates of immigration displaced the indigenous and immigrant pastoralists from land that was formerly used for grazing. The expulsion of the Fulbe from northern Ghana in late 1988 further increased competition for scarce pasture. During the 1988 and 1989 rainy seasons there were repeated complaints of Fulbe cattle destroying farmers' fields and even reports of physical violence.

Future development planning for the Kompienga river basin area will no doubt require some type of area zoning for crop production, grazing and forestry. Spontaneous immigration has occurred on such a scale, however, that any future zoning will involve relocating many homesteads and fields. The hostility generated by this relocation will exacerbate the already stressed relations between the agriculturalists and pastoralists and may create new stresses between hosts and immigrants.

The type of area planning to be funded for the Kompienga basin is still undecided. The information on Kompienga, however, has fairly immediate significance for policy planning near Burkina's second major hydroelectric dam, now under construction at Bagre. In particular, it suggests that:

1. Participatory natural resource zoning to protect the land tenure rights of the indigenous pastoralists and hosts needs to be carried out at a very early stage, well before the actual construction of the dam; and 2. Crop and livestock extension services must be expanded well in advance of the completion of the dam in order to work with the large numbers of spontaneous immigrants who can be expected to move into the area almost immediately.

NIANGOLOKO AND THE CLASSIFIED FOREST AT TOUMOUSSENI Immigration to the Comoe and Leraba River Basins shares many similarities with early immigration to Kompienga. Before 1974, the river basins were highly infected with onchocerciasis. Here too, the indigenous people have traditionally shunned cultivation of the fly-ridden, low-lying areas near the rivers. These same sparse population densities made the area a popular transit grazing spot with the Fulbe agropastoralists. It also made it possible to designate vast areas of the Comoe Province as classified forests during the 1950s [36].

Despite some of the highest rainfall in the country, the Comoe and Leraba river basins have experienced only a threefold increase in the total percentage of land under cultivation between 1974 and 1984, according to the 1984 OCP aerial photo survey 15, p. 19]. This compares with a six-fold increase for the Mouhoun and its major tributaries (ex-Black Volta) near Solenzo. The low immigration to the river basins reflects the lower net immigration figures for the Comoe province between 1975 and 1985 - a net increase of 16,513 persons versus 137,957; 56,439; and 56,439 for the Houet, Kossi and Mouhoun provinces adjacent to the more northern Mouhoun Basin and its effluents and 79,110 for the Sissili province adjacent to the Sissili province [Ref. 28].

The results of the rapid assessment census suggest that immigration to the Niangoloko subsector within the Comoe Province has increased dramatically since 1985. This initial increase in immigration can be attributed to the pastoralists who began moving into the area as active settlement in the more northern river basins displaced them from their traditional grazing areas. Since 1988 a series of violent conflicts between agriculturalists and pastoralists in northern Côte d'Ivoire forced a large number of Fulbe and their herds back across the Côte d'Ivoire-Burkina border. Agricultural immigration to the Niangoloko region has increased since 1983, mostly because of Burkinabè immigrants returning from Côte d'Ivoire in the wake of a downturn in the coastal country's plantation economy. These immigrants are primarily responsible for the recent (since 1985) increase in draft animal and cotton cultivation that we see in certain areas of the Leraba [35].

The rapid assessment census confirmed that, in Niangoloko as in other areas, the largest number of immigrants were attracted to major market and administrative centres and neighbouring villages [35]. Nevertheless, a rapid assessment of "immigrant" households in four more isolated villages along the edge of the Classified Forest at Toumousseni showed a substantial increase in immigration as well (Figure 6). This immigration repeats the early pattern observed for the Niangoloko subsector in that a majority of the immigrant households tend to be pastoralists pushed into the forests by increased agricultural settlement in the more accessible river basins [35].

Although total immigration to the Niangoloko subsector is still less than what was recorded at Solenzo, we expect it to increase. The main impetus for the predicted increase will be the large numbers of Burkinabè expected to return from Côte d'Ivoire. We can also anticipate that a significant proportion of the immigration will be redirected to the southwest as the more northern river basins in the Kossi, Mouhoun, Bougouriba and Houet provinces that were resettled earlier become saturated.

This finding has significant policy implications for natural resource management in Burkina. The Comoe Province includes the largest area of classified national forests of any province in the country [35]. In the past these areas were protected by the river basins' low population densities. As immigration increases, it will be increasingly difficult to restrict illegal grazing and farming in the protected forests.

Forest management projects that enlist the active participation of the local populations are more likely to be successful. A model for this is a series of highly successful projects that have helped agriculturalist and pastoralist extension groups harvest and sell renewable forest products like honey, karite butter, wood and charcoal. The genius of these sorts of multiple-use forest projects is that they create a population with a vested economic interest in protecting and managing the forests.

In view of growing evidence that the rate of immigration is increasing, it would be prudent to expand the development of these multiple use forest management programmes into Comoe Province [35]. Our rapid assessment survey of the Niangoloko subsector showed an annual immigration of 85 families in 1987, 90 in 1988, and 61 in 1989, even without a full census of the Fulbe pastoralists, which would undoubtedly more than double the figures. These numbers are fast approaching the numbers recorded for the Solenzo subsector (81 families in 1986, 67 in 1987, and 120 in 1988). The Solenzo region is well known as an area of active spontaneous immigration. Clearly, Niangoloko is also emerging as such an area.

Conclusions

In summary, the rapid assessment procedure using both qualitative and quantitative approaches that we used i n Burkina Faso offers one cost-effective, rapid method for describing intraregional and interregional immigration trends with greater precision.

Especially important was the ability of these simple studies to depict:

1. important differences among the villages within a region in terms of the rate of new lands settlement; 2. more recent trends in the five years since the last census; and 3. background information on the settlers' occupations and areas of origin.

This information provides a sounder basis for the allocation of funding to facilitate sustainable development in areas undergoing spontaneous settlement.

It is important, however, to stress some of the limitations as well as the strengths of this approach. Although the rapid assessment procedures provide an overview of settlement trends for immigrants still living in the villages, it tells us nothing about the settlers who immigrated into an area, mined the soil and left.

Longitudinal research, over a ten year period, with a single group of settlers living in the AVV planned settlements at Mogtedo [9, 25, 37-42], showed that many of the original study households eventually left the area. These included some of the most successful commercial farmers in the project. Of the 255 households who acquired project farms in the AVV settlements at Mogtedo between 1974 and 1980, only 58% (148) were still living there in 1989 [38,39]. Eighty-one percent of the 345 households that claimed AVV farms at Mogtedo-Bombore in 1980 and 1981 were still residing there in 1989.

A second problem with the technique has to do with the limitations of a single interview survey to give accurate information on income trends. In most cases we found that the information we gathered on the estimated total production for each crop gave an accurate portrayal of the households' crop production patterns and the subdivision of private and cooperative crop production activities within families. The data on livestock and non-farm production, however, were extremely unreliable. The most accurate and frank information that we obtained on these and other complex topics like host-settler and pastoralist-agriculturalist conflicts, was in the villages where team members had worked or lived for many years.

To conclude, no one doubts that the successful control of river blindness can have a substantial economic impact on development in the landlocked Sahelian countries. This development potential is a finite resource, however, and therefore needs to be managed. For this reason there is an urgent need to assist national governments, foreign donors and local populations with the design of more appropriate planning policies. Especially important is the need to work with spontaneous settlement as it is occurring - not after problems have emerged.

Not all of the research techniques that the Land Settlement Review developed were equally successful. Nevertheless, these techniques could be used as a point of departure for the development of a handbook of practical guidelines, topics for data collection and data gathering aids to improve policy planning in the OCP river basins. Current efforts by anthropologists to incorporate anthropological approaches to improve programme effectiveness in nutrition and primary health care [40,41] and in farming systems research and extension [42-44] provide a model for how this standardization might be carried out.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Carol Lauriault, Priscilla Reining, Thayes Scudder and Mary Sies who provided useful comments on various drafts of this paper.

1. McMillan D, Painter T. Scudder T. Final Report of the Land Settlement Review: Settlement Experiences and Development Strategies in the Onchocerciasis Controlled Areas of West Africa. Binghamton, NY: IDA (Institute for Development Anthropology), 1990.

2. OCP (Onchocerciasis Control Programme), Joint Programme Committee. Onchocerciasis Control Programme in West Africa Progress Report of the World Health Organization for 1990 (1 September 1989-31 August 1990). Report No. JPC11.2 (OCP/PR/90). Ouagadougou: Onchocerciasis Control Programme, 1990.

3. Remme J. Zongo JB. Demographic aspects of the epidemiology and control of onchocerciasis in West Africa. In: Service MW, ed. Demography and Vector Borne Diseases. Boca Raton Florida: CRC Press, Inc., 1989.

4. OCP. Report on the Evaluation of the Socioeconomic Impact of the Onchocerciasis Control Programme. Report No. JPC7.3 (OCP/86.7). Ouagadougou: OCP, 1986.

5. Hervouet JP, Clanet JC, Paris F. Some H. Settlement of the valleys protected from Onchocerciasis after ten years of vector control in Burkina. (OCP/GVA/84.5). Ouagadougou: OCP, 1984.

6. Hunting Technical Services, Ltd. Socioeconomic Development Studies of the Onchocerciasis Control Programme Area (4 Volumes). London: Hunting Technical Servies, Ltd., 1988.

7. Akwabi-Ameyaw K. Land Settlement Review, Country Case Study: Ghana. Binghamton, NY: IDA, 1990.

8. Koenig D. Land Settlement Review, Country Case Study: Mali. Binghamton, NY: IDA, 1990.

9. McMillan D, Nana JB, Savadogo K. Land Settlement Review, Country Case Study: Burkina Faso. Binghamton, NY: IDA, 1990: 104-106.

10. Painter T. Land Settlement Review, Country Case Study: Togo. Binghamton, NY: IDA, 1990.

11. Ancey G. Facteurs et systémes de production dans la société mossi d'aujourd'hui: migrations, travail, terre et capital. In: Enquéte sur les mouvements de population a partir du pays Mossi, Tome 11. Ouagadougou, Paris: ORSTOM (Office de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique Outre-Mer), 1974.

12. Benoit M. Espaces agraires mossi en pays bwa. 2 tomes. Ouagadougou, Paris: ORSTOM, 1973.

13. Benoit M. Le champ spatial mossi dans les pays du Voun-Houet de la Volta Noire (Cercle de Nouna, Haute-Volta). Cahiers des Sciences Humaines 1973; X(2): 115-137.

14. Capron J, Kohler JM. Environnement sociologique des migrations agricoles. In: Enquête sur les mouvements de population a partir du pays mossi, Tome 1. Ouagadougou, Paris: ORSTOM, 1974.

15. Kohler JM. Activités agricoles et transformation socio-économique de l'ouest du mossi. Paris: ORSTOM, 1972.

16. Marchal JY. Géographie des aires d'émigration en pays mossi. In: Enquéte sur les mouvements de population à partir du pays Mossi, Dossier 11, Fascicule 3. Ouagadougou, Paris: ORSTOM, 1975.

17. Remy G. Les migrations de travail et les mouvements de colonisation mossi. Paris: ORSTOM, 1973.

18. Angel S. Spontaneous land settlement on rural frontiers: an agenda for a global approach. Paper presented at the International Seminar on Planning for Settlements in Rural Regions: The Case of Spontaneous Settlements. Nairobi, Kenya, 11-20 November 1985.

19. Becker BK. Spontaneous/induced rural settlements in Brazilian Amazonia. Paper presented at the International Seminar on Planning for Settlements in Rural Regions: The Case of Spontaneous Settlements. Nairobi, Kenya 11-20 November 1985.

20. Bharin TS. Review and evaluation of attempts to direct migrants to frontier areas through land colonization schemes. In: Population Distribution Policies in Development Planning. Population Studies No. 75. NY, NY: United Nations, Department of International Economic and Social Affairs, 1981.

21. Couty P. Marchal JY, Pélissier P. Poussi M, Savonnet G. Schwartz A, eds. Maîtrise de l'espace agraire et développement en afrique tropicale: logique paysanne et rationalité technique. Paris: ORSTOM, 1979.

22. Dollfus O. Phénoménes pionniers et problémes de frontiéres: quelques remarques en guise de conclusion. In: Les Phénoménes de "Frontiére" dans les pas tropicaux. Travaux et Mémoires de l'Institut des Hautes Etudes de l'Amérique Latine 32: 445-448.

23. McMillan D. Land Settlement Review, Draft Country Case Study: Burkina Faso (Analysis of Material from Site Reports and Other Research at AW-UP1, Kompienga, Solenzo, and Niangoloko). Binghamton, NY: IDA, 1990.

24. Weitz R. Pelley D, Applebaum L. Employment and income generation in new settlement projets Geneva: International Labour Office 10/WP3. World Employment Paper 10, Working Papers 3, 1978.

25. Van Raay GT, Hilhorst JGM. Land settlement and regional development in the tropics: results, prospects and options. The Hague: Institute for Social Studies Advisory Board, February 1981.

26. Scudder T. The development potential of new lands settlement in the tropics and subtropics: a global state-of-the-art evaluation with specific emphasis on policy implications. Binghamton, NY: IDA, 1981.

27. Scudder T. The experience of the World Bank with government-sponsored land settlement. Report No. 5625, Operations Evaluation Department. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 1985.

28. SEPIA (Société d'Etudes de Projets d'Investissement en Afrique). Etude Démographique: Projections de la population Burkinabé pour les années 1990, 1995 et 2000. Ouagadougou: SEPIA for the Comité National de Lutte Contre la Desertification, Plan d'Action National pour l'Environnement (PANE), 1990.

29. AVV (Aménagement des Vallées des Volta). Programme réforme agraire et gestion de l'espace UP1-Zorgho (UD de Linoghin, UD de Rapadama). Rapport general. Ouagadougou: DEPC, Service Etudes et Programmes, 1988.

30. Agrotechnik. Etude de développement régional ans le bassin versant de la Kompienga. Rapport final. Référence No. 84.70.049, 1989.

31. Nana JB. Rapport sur le site de sous-secteur de Solenzo. Land Settlement Review Draft Site Report. Binghamton, NY: IDA, 1989.

32. CRPA (Centre Regional de Promotion Agro-pastorale de la Boucle du Monhoun). Rapport d'achévement de projet. Projet de développement agricole de la boucle du monhoun (ex-volta noire). Dedougou: CRPA du Mouhoun, 1989.

33. Savadogo K, Sanders J. Farm and female productivities in the river blindness settlement programs of Burkina Faso. Land Settlement Review Draft Site Report. Binghamton, NY: IDA 1989.

34. Savadogo K. Factors explaining household food production systems. Land Settlement Review Draft Site Report. Binghamton, NY: IDA, 1989.

35. Nana JB. Rapport sur le site de la zone de sous-secteur de Niangoloko et de la forét classée de toumousseini. Land Settlement Review Draft Site Report. Binghamton, NY: IDA, 1989.

36. Murphy J. Sprey L. The Volta Valley Authority: socioeconomic evaluation of a resettlement project in Upper Volta. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University, Department of Agricultural Economics, 1980.

37. McMillan D. A resettlement project in Upper Volta. Ph.D. Dissertation, Anthropology Department. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University, 1983.

38. AVV. L'Impact socio-économique du programme de lutte contre l'onchocercose au Burkina (1974-1984) Ouagadougou: AVV. Juin, 1985.

39. Sawadogo S. Rapport préliminaire départs de Mogtedo et Mogtedo-Bombore. Land Settlement Review Draft Site Report. Binghamton: IDA, 1989

40. Scrimshaw SCM, Hurtado E. Rapid assessment procedures for nutrition and primary health care: anthropological approaches to improving programme effectiveness. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1987.

41. Scrimshaw SCM, Hurtado E. Anthropological involvement in the Central American Diarrheal Disease Control Project. Soc Sci Med 1988; 27, 1: 7-105.

42. Fresco LO, Poats SV. Farming systems research and extension: an approach to solving food problems in Africa. In: Hansen A and McMillan DE, eds. Food in Sub-Saharan Africa. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., 1886.

43. Hansen A. Learning from experience: implementing farming systems research and extension in the Malawi Agricultural Research Project. In: McMillan D., ed. Anthropology and Food Policy. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991.

44. Shaner WW, Philipp PF, Schmehl WR. Farming systems research and development: guidelines for developing countries. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1982.

13. Rapid assessment procedures and the Latinas and AIDS research project

Introduction The Latinas and AIDS research project AIDS prevention workshops for Latinas Implications for future research and application Conclusion References Additional reading Annex A: Summary of workshop illustrated fact and fiction card data Annex B: Individual card responses for Latina subset, workshop data

By Laura Ramos

Laura Ramos is at the School of Public Health, UCLA.

This paper provides a detailed description of the use of RAP to identify difficult to reach populations who may be at higher than normal risk for contracting AIDS. Additionally, the step by step development of a visually based testing instrument for assessing knowledge gain in small groups workshops on sexual behavior and AIDS risks to Latina women in Los Angeles County is described. The procedures outlined may be of significant value to those developing illustrative educational materials on AIDS prevention for low and/or non-literate populations. - Eds.

THE AIDS EPIDEMIC in the United States has now increased to more than 179,000 cases [CDC, June 1991]. While the majority of these cases have been adult and adolescent males, the number of women affected by AIDS is increasing at a rapid pace. There are now almost 18,000 women's AIDS cases, and that official number is considered to be a underestimate of the true level of this problem in women [ Chu, et al., July 1990]. Within the women's AIDS cases, Latinas (20%) are disproportionately represented compared to their estimated proportion of the national population (8% respectively) [Worth, 1990a, 1990b]. Of the small number of documented lesbian AIDS cases, Latinas represent 42% [Chu, November 1990]. Thus it is important to study the effect of the AIDS epidemic within Latina populations in the United States, and to develop culturally specific methods of AIDS prevention which will be effective in stemming the tide of the epidemic in Latina populations [Arguelles and Rivero, 1990]. This concept is well stated in Scrimshaw, et al.'s, article, "The AIDS Rapid Anthropological Assessment Procedures: A Tool for Health Education Planning and Evaluation" [Scrimshaw, Spring 1991]:

"The AIDS epidemic has highlighted the need for both quantitative and qualitative research into social and cultural factors influencing human behaviour, particularly in terms of preventive measures and supportive care. Baseline research prior to programme design is needed to provide information to guide the development of health education interventions. Formative research in which educational materials are tested is equally needed to refine those interventions in a way that makes them culturally appropriate, well understood and accepted. Obtaining these data is often complicated by the fact that behaviours related to the prevention and treatment of AIDS are usually considered personal and confidential. They may not be readily revealed publicly and are constantly changing. The issues which can be discussed and the manner in which they are discussed vary from culture to culture. Efficient methods of collecting this information are essential to health education efforts both in terms of accuracy and speed."

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Desertification Challenge : case study of Burkina Faso ... • In Burkina Faso, nearly 250,000 ha of natural formations are cleared to satisfy the need for firewood, crop land, pasture.

Burkina Faso is an ideal case to investigate because the country is experiencing all the economic and demographic trends that are generally associated with desertification (Niemeijer and Mazzucato, 2002).Burkina Faso (274,000 km 2) is a landlocked country in West Africa with >13 million inhabitants (Wittig et al., 2007).It is one of the poorest regions of the world, and urbanization is ...

Burkina Faso is a former French colony in West Africa. "In a study of the Mossi plateau in central Burkina Faso, 32.2% of the area investigated [was] degraded savanna in 1975. Twelve years later, in 1987, this percentage had risen to 65.3" (Davis 2004) This problem of desertification has long been known in Burkina Faso, Former president of ...

05/07/2019. Gargaboulé, Burkina Faso - Two years of restoration work in northern Burkina Faso show that land degradation is not yet irreversible. Rural communities work with FAO's Action Against Desertification, putting scientific know-how into practice to tackle some of Africa's drylands long-time woes.

CASE STUDIES IN NORTHERN BURKINA FASO. Department of Physical Geography, University of Goteborg, G6teborg, Sweden. Lindqvist, Sven and Tengberg, Anna, 1993: New evidence season; of it lies between the isolines for precipita- desertification from case studies in northern Burkina Faso. tion of 100 to 650 mm/year. The vegetation is.

Assessing desertification in sub-Saharan peri-urban areas: Case study applications in Burkina Faso and Senegal

This study, carried out within the FP7-ENV-2010 CLUVA project, aimed to classify and map sensitivity to desertification in peri-urban areas of Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) and Saint Louis (Senegal ...

DOI: 10.1016/J.GEXPLO.2018.03.012 Corpus ID: 133820953; Assessing desertification in sub-Saharan peri-urban areas: Case study applications in Burkina Faso and Senegal @article{Capozzi2018AssessingDI, title={Assessing desertification in sub-Saharan peri-urban areas: Case study applications in Burkina Faso and Senegal}, author={Fiore Capozzi and Anna Di Palma and Francesco M. De Paola and ...

From the time of the United Nation's Conference On Desertification in Nairobi, 1976, certain areas of northern Burkina Faso have been pointed out as examples of severe desertification. Several studies demonstrated that revitalization of a series of E-W oriented fossille dunes in the Oudalan province was ongoing.

ABSTRACT. Case studies on desertification in northern Burkina Faso, in the Western Sahel, using satellite-aided ground navigation technology, have shown that a noticeable environmental degradation took place from the late 1960s to 1990.

One-third of Burkina Faso's national territory - over 9 million hectares of productive land - is degraded. This area is estimated to expand at an average of 360 000 hectares per year. Action Against Desertification supports land restoration in the provinces of Soum, Séno and Yagha in Burkina's Sahel region.

DOI: 10.1080/04353676.1993.11880390 Corpus ID: 129234883; New evidence of desertification from case studies in Northern Burkina Faso @article{Lindqvist1993NewEO, title={New evidence of desertification from case studies in Northern Burkina Faso}, author={Sven Lindqvist and Anna E. Tengberg}, journal={Desertification control bulletin}, year={1993}, pages={54-60} }

Study area. Burkina Faso is an ideal case to investigate because the country is experiencing all the economic and demographic trends that are generally associated with desertification (Niemeijer and Mazzucato, 2002). Burkina Faso (274,000 km 2) is a landlocked country in West Africa with >13 million inhabitants (Wittig et al., 2007). It is one ...

Desertification studies show that with the aggravation of desertification, ... (2018) Assessing desertification in sub-Saharan peri-urban areas: case study applications in Burkina Faso and Senegal. J Geochem Explor 190:281-291. Article Google Scholar Charney J, Stone PH, Quirk WJ (1975) Drought in the sahara: a biogeophysical feedback ...

The consequences of desertification in the Sahel are severe, including food insecurity, loss of biodiversity, and displacement of communities. in the region, for around 8 months of the year, the weather is dry. The rainy season only happens for a few short months and only produces around 4-8 inches of water. The population growth over the years ...

Rasmussen, Kjeld & Anette Reenberg: Satellite Remote Sensing of Land-use in Northern Burkina Faso—the Case of Kolel Village. Geografisk Tidsskrift 92:86-93. Copenhagen 1992. On the basis of SPOT … Expand. 14. ... ABSTRACTCase studies on desertification in northern Burkina Faso, in the Western Sahel, using satellite-aided ground navigation ...

The literature on women in Burkina Faso has focused only on broad issues of women's status. The few studies of local conditions conducted on a small scale by nongovernmental organizations have revealed that women were 60-80% of the labor force on anti-desertification projects.

McMillan, D. 1995. Sahel visions: planned settlement and river blindness control in Burkina Faso. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. McMillan, D., J. Nana and K. Savadogo. 1993. Settlement and development in the River Blindness Control Zone: case study of Burkina Faso. World Bank Technical Paper 200. Washington DC: The World Bank.

From the time of the United Nation's Conference On Desertification in Nairobi, 1976, certain areas of northern Burkina Faso have been pointed out as examples of severe desertification. Several studies demonstrated that revitalization of a series of E-W oriented fossille dunes in the Oudalan province was ongoing. The present study includes an ...

Under the Resilient Food System (RFS) Programme, UNDP and AGRA co-designed three catalytic grant projects to pilot innovative approaches and model projects to showcase and develop practical methodologies of promoting Green Value Chain Development in East, Southern and West Africa. In Burkina Faso, the catalytic grant project "Fostering Climate-Resilient Agriculture for Resilient Maize ...

What is desertification: It is the term used to describe the changing of semi arid (dry) areas into desert. It is severe in Sudan, Chad, Senegal and Burkina Faso. What are the causes: Overcultivation: the land is continually used for crops and does not have time to recover eventually al the nutrients are depleted (taken out) and the ground eventually turns to dust.

Stone lines - Water and soil management. Desertification leads to outmigration in countries such as Burkina Faso in the Sahel. This idea was to lay stones along the contours of the land in long lines which traps the rainwater that falls. A contour stone line 25 to 30cm high with other stones behind is constructed.

The Burkina Faso case study. General methodology. The Burkina case study research followed the basic Land Settlement Review (LSR) model. 1 The case study was based on a blend of quantitative and qualitative research at four study sites - the AVV (Autorité pour l'Aménagement des Vallées des Volta, or Volta Valley Authority) planned settlements in the upper Nakambe (ex-White Volta) [1] river ...