An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

- PMC10016174

Engaged learning during distraction: a case study of successful working moms in distance education

Anne fensie.

1 College of Education and Human Development, University of Maine, Orono, USA

2 5766 Shibles Hall, Orono, ME 04469 USA

Teri St. Pierre

Jennifer jain, asli sezen-barrie.

Adult learners are a significant proportion of distance learners and many of these students are working mothers. Several instructional design models center the learner, and this requires understanding the learner needs, strengths, and context. There is a gap in the literature describing the experience of modern working mother students in distance education. To understand this experience, the researchers interviewed and observed six academically high-achieving working mother students as they participated in their distance education courses during the pandemic. A discourse analysis approach was utilized to analyze the data. This extreme sample revealed several strategies that these students used to be successful despite their challenges. The findings suggest that understanding the experiences of distance learners as they study in the home are important for effective course design. More specifically, working mothers face significant distractions in their study environments, but the cognitive load can be reduced by making use of their prior knowledge, scaffolding instruction, and encouraging social presence. Additional strategies from the literature that address these constructs are provided for instructors and instructional designers.

Approximately 20% of college undergraduates are parents or guardians of children under 18, and 70% of these students are women (Cruse et al., 2020 ). Moreover, more than a third of graduate students are parents (Yoo & Marshall, 2022 ) and women enroll in postbaccalaureate education at twice the rate of men (Harrington, 2013 ). The proportion of graduate students who are mothers has continued to rise (Kuperberg, 2009 ). Mothers return to school for several reasons, including better income and to be role models for their children (Estes, 2011 ; Forste & Jacobsen, 2013 ; Lindsay & Gillum, 2018 ). Conceptions of "intensive mothering" in modern society define the successful mother as "patient, self-sacrificing, and devoted to caring for others," yet the time and energy required to maintain parenting responsibilities compete with the demands of role maintenance as an employee and student (Markle, 2015 , p. 269; Thomas et al., 2021 ). In addition, single and divorced mothers often carry the role of sole wage-earner for the family and bear all of the responsibility for childcare (Forste & Jacobsen, 2013 ). For many working mother students, their self-concept is tied to their success in balancing these roles (Lindsay & Gillum, 2018 ). Many mother students wished more faculty understood their needs (Mahaffey et al., 2015 ). This study aimed to understand the distance learning experience of academically high-achieving working mother students to inform faculty in their design of instruction for these learners and other adult learners.

Several instructional design models and frameworks center on the learner, such as the ADDIE approach, cognitive apprenticeship, design thinking, and Learning Experience Design (LXD), yet many faculty still maintain a mindset of knowledge transmission versus learning facilitation (Allendoerfer et al., 2014 ; Lane, 2018 ; Liu et al., 2006 ; Norton et al., 2005 ). While faculty are beginning to shift their thinking towards student-centered learning, there is some evidence that self-reported beliefs of instructors often do not match practice and much of the research does not examine both beliefs and practices (Kane et al., 2002 ). Distance education continues to increase in popularity with adults as the primary audience for this modality, yet adults left higher education during the pandemic at alarming rates (Gallagher, 2021 ). Understanding these learners will be essential for developing distance instruction to meet their needs. Examining an extreme case, such as academically high-achieving working mothers, may be helpful in emphasizing salient characteristics and experiences of the adult learner in distance education (Patton, 1990 ).

Two prominent approaches to instructional design in higher education that include a focus on understanding the learner are the ADDIE process and Learning Experience Design (LXD). ADDIE, which stands for Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate, is a development paradigm that emerged from instructional systems design in the military (Allen, 2006 ), and addresses the needs, learner, context, and tasks in the first phase (Ritzhaupt & Covello, 2017 ). Learning Experience Design (LXD) has been defined as “a human-centric, theoretically-grounded, and socio-culturally sensitive approach to learning design, intended to propel learners towards identified learning goals, and informed by UXD methods” (Schmidt & Huang, 2022 , p. 151), maintaining a focus on the individual learner experience. These approaches are gaining traction in higher education, but the authors contend that the learner and context are often overlooked in the design of instruction (A. H. Brown & Green, 2019 ; Tessmer & Richey, 1997 ). Much of the literature on adult learners in distance education has limited descriptions and lacks the deep context necessary to fully understand the learner (Gunawardena & McIsaac, 2004 ), particularly when balancing multiple life roles such as work and motherhood, so this collective case study attempts to provide some insight into important factors to consider in instructional design and facilitation for students like working moms.

In this paper, the authors begin by briefly summarizing the literature on adult learners in distance education, including working mothers, and then outlining the conceptual framework guiding this study. The next section describes the case study methodology and the collective case study method used, including a description of the participants, data collection methods, and data analysis. In the third section of the paper, the authors present the cases and the results of the findings that speak to the need to understand the learner when designing instruction, specifically understanding the level of distraction that these adult working mothers faced in distance education and the effects of prior knowledge and self-pacing on student success. Design considerations and potential applications in practice are presented in the fourth section, including addressing cognitive load, scaffolding of instruction, and increasing social presence. Implications of this research and a summary of these sections conclude the paper.

Literature review

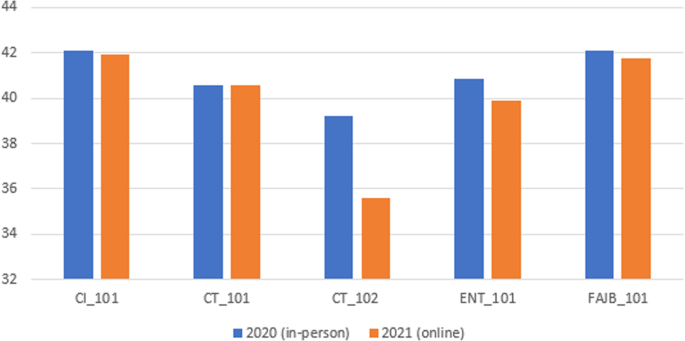

Adult learners have participated in distance education since it first became available through correspondence courses in the early eighteenth century (Casey, 2008 ; Harting & Erthal, 2005 ). Distance options for accessing higher education have been available to adults through the mail, radio, television, video conference, and the internet. Opportunities to take courses at a distance have been increasing in availability since the rise of web-based technologies (see Fig. 1 ) with 33% of institutions of higher education offering distance education courses in 1995 to 79% in 2018. Of those that offered distance courses, asynchronous options rapidly grew in this time frame. The proportion of students at an institution taking distance education courses has also increased in recent years from only 5% of all enrollments in 1995 to 35% of enrollments in 2018. In the fall of 2020, 74% of all students in higher education were enrolled in a distance education course (de Brey et al., 2022).

Distance education offerings and enrollment in higher education in 1995 – 2018. Data are not available for the rate of institutions that offer online courses as an option for distance education in 2018, but the trend, pervasiveness of Internet technologies, and the recent pandemic suggest that this rate is close to 100%. Data are not available for the portion of total enrollments for 2006 because the numbers reported were duplicated student counts of registrations

Sources : (Lewis et al., 1997 ; Parsad & Lewis, 2008 ; Ruiz & Sun, 2021 ; Waits & Lewis, 2003 )

Enrollment in distance education has grown for all age groups, but adults participate in distance education at higher rates than traditional-aged college students (see Fig. 2 ). For example, in 2015, 23% of traditional-aged college students were enrolled in distance education, while 51% of adult undergraduate students aged 24–29 were enrolled in distance education and 54% of those aged 30 or older.

Percentage of undergraduate students enrolled in distance higher education in 2003–2015

Source : (Snyder et al., 2019 )

Distance education is the primary domain for adult learners in higher education; however, adult learners face many challenges while participating in distance education, including internal, external, and program-related problems with working mothers facing the most significant level of challenge (Kara et al., 2019 ). In the nineteenth century, “normal schools”, or higher education institutions that trained nontraditional students to become teachers, excelled at providing inclusive and supportive environments for students from a variety of backgrounds, particularly those from rural and low-income areas (Ogren, 2003 ). Normal students were integrated in a vibrant school community. However, as these schools transformed into universities, the focus on nontraditional learners was lost.

Developing an identity as a student can be particularly challenging for adults who also balance financial, personal, and family obligations (Banks, 2018 ; Berker et al., 2003 ; Flynn et al., 2011 ; Ross-Gordon, 2011 ). This necessitates the consideration of the whole learner, including all of their responsibilities, their background, mindset, and social factors. Traditional-aged college students often identify first as a student, while adults weave “student” into their already complex self-concept (Berker et al., 2003 ; Kasworm, 2008 ). Kasworm noted that adult learners often enter higher education after a life crisis, adding to the emotional burden of developing a new student identity. She argued, “When time is perceived as limited, emotion-related goals assume primacy”, continuing to say that this “captures the paradoxical place of the adult student as an emotional self and a knowledge-striving self” (p. 30). Kasworm also remarked on the role of faculty in the experience of the adult learner: mature students are affected by validation from faculty about their belonging in higher education.

Family support and feelings of guilt have been shown to impact how mother students balance their competing life roles (Thomas et al., 2021 ; Webber & Dismore, 2020 ). Family members provide the most significant social and emotional support which allows women to better balance their roles of student and mother (Kensinger & Minnick, 2018 ). Women’s feelings of guilt stem from their perceived failures due to a lack of control resulting in their inability to balance the demands from their different roles (Korabik, 2015 ). Earlier research on mother students in distance education reported on the “double burden” of meeting the needs of their family as well as “their own self-imposed, sometimes dysfunctionally high standards for ‘domestic and mothering roles,’ as if they want to offer compensation for ‘being allowed’ to enter formal programs” (Burge, 1998 , p. 31). Single mothers in one study found that maintaining a schedule and routine were essential for success in balancing their roles (Lindsay & Gillum, 2018 ). Our goal in this study was to explore the experiences of modern working mother students and potentially identify other strategies that have been beneficial to them.

In this article, the authors use the U.S. Department of Education definition of the nontraditional learner as “being independent for financial aid purposes, having one or more dependents, being a single caregiver, not having a traditional high school diploma, delaying postsecondary enrollment, attending school part time, and being employed full time” (Radford et al., 2015 , p. 7). The Department also defines independence as age 24 and older. As the cognitive processes that impact learning begin to change at this age (Ackerman, 1996 ; Fjell et al., 2013 ; Hagen & Park, 2016 ; Kirchhoff et al., 2014 ; Salthouse, 2010 ), the authors further define adult learners as those age 24 and older. The term distance education refers to synchronous and/or asynchronous online or technology-mediated instruction where the student and teacher are not in the same physical location (Simonson & Seepersaud, 2019 ). This can include completely online classes, video conference classes, hyflex classes where students have the option to attend synchronously or asynchronously in person or remotely, and hybrid combinations that include the above paired with traditional classroom modalities. As recommended by research scholars, it is important to define student success and how it guides the research (Weatherton & Schussler, 2021 ). The authors define academically high-achieving or successful as maintaining continuous enrollment with a GPA of 3.5 or above and balancing the many roles that working mother students maintain.

Conceptual framing

We used Learning Experience Design (LXD) to conceptually frame this work. LXD features human-centered, theoretically grounded, and socio-culturally responsive designs that utilize user experience design (UXD) methods (Schmidt & Huang, 2022 ). This framework is appropriate for this study as our intention was to understand the learning experience of these working mother students, using theory and the extant literature on socio-cultural factors to interpret our data (see Table Table1). 1 ). To understand the human aspects of our learners, the first component of LXD, we used cognitive load theory (Sweller et al., 2019 ) as well as research on attention (Petersen & Posner, 2012 ), and motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2020 ). This research was used to help us understand the learning behaviors we observed in our participants and examine some of the internal factors that were most relevant to their learning experiences. Developing personas and scenarios are integral to learning experience design (Schmidt et al., 2020 ), so we aimed to provide rich descriptions of each participant and describe scenarios where they were engaged in their course learning activities.

Conceptual framework used to guide this study

This table shows the four components of Learning Experience Design (LXD) along with the related constructs for each component used to inform this study

The second component of LXD is grounding design in theory. Our research was grounded in adult learning theories, such as andragogy, self-directed learning, and transformative learning (Merriam, 2017 ). This focused our attention on the aspects of learning that are unique to adults as opposed to children or traditional-aged college students, such as their approach to learning. Many adult learning and distance education theories emphasize the importance of considering the whole student when planning and facilitating online learning (Gibson, 1998 ; Merriam, 2017 ), which requires specific design strategies and supports that accommodate unique learning contexts (Tessmer & Richey, 1997 ). Much of the literature on adult learners in distance education prior to the advent of the internet focused on these areas (e.g., Gibson, 1998 ), but more recent literature focuses on student perceptions of learning, online learning communities, and student persistence in degree programs (Fensie et al., 2022 ).

We also grounded our research study in the theories of embodied discourse analysis (Poynton & Lee, 2011 ). Embodied cognition posits that bodily states, modalities affecting perception and action, and interactions with a specific context affect mental phenomena, like learning (Foglia & Wilson, 2013 ; Sampson, 1996 ). A rich tradition in discourse analysis (Miles, 2012 ) provided us with some methods of data exploration in the relatively new field of multimodal research (Jewitt, 2012 ). This guided our observations and interpretations of the movements, body language, and actions of the students in the screen recordings.

The third component of LXD is socio-cultural responsiveness. Adults do not learn in isolation, even when they are separated from an instructor and peers by distance, so critical social science perspectives (Brookfield, 2018 ) and situated learning theories (Lave & Wenger, 1991 ) helped the researchers to consider the student participants' ways of being in the world in relation to their learning. Because adults often balance multiple responsibilities with competing demands, the researchers were interested to see how they coped with these demands and how their life roles and identities interacted. While most traditional learning theories focus on the rational and cognitive aspects of knowing, the authors recognize that learning is inextricably linked to the whole person, including the mind, body, and spirit. The final component of LXD, user experience design methods, were not used in this study as our goal was not to design instruction but to understand the learning experience for future design.

Case study methodology

Case Study is used as a methodology in the social sciences to provide a deep understanding of the context of a phenomenon with either a single instrumental case study to illustrate a unique case, a study of multiple cases for identification of common themes, or an intrinsic case study which represents a unique situation (Creswell & Poth, 2018 ). To understand the experience of adults in distance education, the researchers recruited six academically high-achieving working mothers who participated in synchronous and asynchronous online learning in the summers of 2020 and 2021, an extreme sample. Patton ( 1990 ) suggested that purposive sampling that included extreme cases, such as “outstanding successes” could provide rich information to understand the boundaries of a phenomenon (p. 231). Primarily a qualitative approach is used with a constructivist epistemology in case study methods (Merriam & Merriam, 1998 ; Stake, 1995 ), although some use a positivist approach (Yin, 1994 ). The researchers combined these approaches by using the interviews and observations to construct an understanding of the experience of these six women and also worked to quantify some of the data to synthesize the observations of their study sessions. Merriam’s defining characteristic of case study research is the delimitation of the case; a bounded system—a single unit around which there are boundaries (Merriam in Yazan, 2015 ). The boundaries of these cases were academically high-achieving working mothers in distance education in the summers of 2020 and 2021 who were studying from home.

The researchers used both holistic analysis of the entire cases and embedded analysis to examine specific aspects within each case (Creswell & Poth, 2018 ). Cases were analyzed individually, and then common themes were examined across the cases. The approach was inductive as themes were allowed to emerge from within each case to drive the study with the focus on identifying themes common across all cases.

Participants

Three faculty, three undergraduates, and three graduate students at rural public universities in the Northeastern United States were included in this case study. IRB approval was obtained for study with human subjects. A purposive sample of faculty who had experience teaching adult learners in distance education were selected, who then helped to recruit student participants from within their classes by sending out email invitations. The six student participants who responded all had a history of academic excellence, juggled multiple roles, and developed strategies to be successful students through the challenges of being distance learners at home. All six women were White, had school-aged children, were employed outside the home, and were experienced distance learners. While this study occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, their previous experience equipped them to handle the learning challenges but not the increased demand on their mental load from stress and forced isolation. Initially, the intent was to recruit a variety of adult learners with different characteristics; however, few students responded to the calls for participation, possibly because the recruitment period was at the beginning of the pandemic. Those students that did respond to the invitations all happened to be academically high-achieving working mothers, so when the researchers recruited additional participants in later classes, they purposively selected participants with those characteristics.

Data collection

Data sources included interview and weekly debrief conversation transcripts and recordings of faculty and students, as well as annotated and video-recorded study sessions of the student participants. The study began with interviews of the faculty who taught the distance classes the student participants were enrolled in to understand their expectations for the student experience. Faculty were asked about their perceptions of nontraditional learners, what factors are important to them in their course design, and what they expected the student experience to be like. These data were used to understand the instructional strategies and intentions of the faculty and was compared to the student experience. Student participants were then enrolled, and interviews were conducted to gain an understanding of their online learning experiences, the challenges they faced, and strategies they developed to persist. Participants recorded their study sessions for at least 30 min at least once a week during a three-week time frame. Unique Zoom links were provided to each participant, and participants were instructed to share their screen, camera, and microphone during their study sessions so the entire experience could be recorded.

Telephone or Zoom check-ins were scheduled with student participants each week to debrief their study sessions. These sessions were ten to twenty minutes in length and were recorded and transcribed or annotated. These conversations helped to clarify what was viewed in the study session recordings, ask probing questions, and allowed the students to explain other activities and experiences they had during the week. Following data collection, small video clips of study sessions were shared with each participant during Zoom meetings as an opportunity for member checking and to collect additional data. Students were asked to confirm interpretations of what was seen on the screen and to elaborate on their experiences during the recorded moments.

Positionality

The authors now pause to insert relevant information about themselves as researchers and the lens with which the data were analyzed. These authors decided on the research topic, target audience, data collection, and analysis, and thus their positionality matters (Reich, 2021 ). Anne Fensie was a 35–44 year old married White mother of three teen children, two with special needs, who balanced doctoral studies, a graduate assistantship, and university teaching. Her first attempt at doctoral studies was not successful when her children were younger and receiving intensive therapeutic services. At that time, she also struggled with challenges to her mental health. With the help of her husband and middle child, she has since structured her home environment to safeguard her work time; however, distractions continued to intrude, particularly in the form of a highly inattentive and impulsive daughter. Anne completed her master’s degree in a hybrid format and participates in much of her current program through Zoom.

Teri St. Pierre was a 35–44 year old married White mother of three children aging in range from six through fourteen. She worked as an Assistant Professor of Mathematics and the Director of Early College while pursuing her doctoral degree mostly via Zoom. She attempted to balance work and family life while transporting her children to sports activities and working from her car. She obtained one graduate degree live and one entirely online. She thrived in an environment where she can collaborate with other students. Teri was still trying to structure her role of “student” in the home but had made progress in the form of a home office and external support. As a night owl, she completed work late at night while her children and husband were not a distraction.

Jennifer Jain was a 45–54 year-old mixed-race mother of a teenager and young adult who both lived at home with her husband and puppy. She was a doctoral student who worked part-time as a research assistant at the Center on Aging, is a former university lecturer, and had worked as a recreational therapist in mental health. Jennifer delayed doctoral studies due to the high intensity of her husband’s career. She was also the family chauffeur, sporting event spectator, and managed all other household duties as needed. Finding time to do schoolwork was a challenge, but in order of importance, she tended to juggle her work and schoolwork in the mornings, when there was less distraction. She worked sporadically during the afternoons during the highest level of distraction and again in the evening hours, when there were no distractions, but she often hit a wall and fell asleep at the computer.

Being working mothers and students, these authors could identify with the challenges the participants faced in their own studies. Their experiences made them more sensitive to the level of distraction these students faced and their strategies for managing the competing demands of motherhood, being a spouse, homemaking, work, and school. Although the authors were all experienced educators, they did gain important insights from the experiences of these participants. For example, by examining the experiences of these students, they learned the importance of developing a well-structured syllabus that allows students to plan in advance and know what to expect from instructors (Jones, 2018 ; Ramírez Espinosa, 2015 ; Taylor et al., 2019 ). Much of what they observed validated their own strategies for success as working mother-students and highlighted the importance of time and space for study (Webber & Dismore, 2020 ).

The authors openly discussed bias and used strategies to reduce it, including triangulation, member checking, researcher reflexivity, an audit trail, rich descriptions of the data, and peer debriefing (Creswell & Miller, 2000 ). Several of the study session videos were analyzed by at least two researchers to calibrate their interpretations of the actions (Creswell & Poth, 2018 ), and several data sources were used to support each claim (Miles et al., 2020 ). Member checking was completed through showing the student participants video clips of their study sessions and discussing what was seen, and weekly debrief interviews with each participant also helped to gauge what happened during a study session (Creswell & Miller, 2000 ). The researchers challenged each other's interpretations of the data during meetings and discussed findings with colleagues (Miles et al., 2020 ). They used analytic memos during transcript coding and video annotations to capture their impressions of the data (Miles et al., 2020 ). Notes were taken during meetings among the authors, with some of these meetings recorded, and procedures and definitions were documented, creating an audit trail (Creswell & Miller, 2000 ). The cases are described below with rich descriptions and details to illustrate the findings (Miles et al., 2020 ). Finally, they asked an expert in qualitative research to examine the manuscript and methods for researcher bias (Miles et al., 2020 ).

Data analysis

Here, the authors describe the process used for analyzing the data which included the use of process codes to annotate the interview transcripts using the constant comparative method (Charmaz, 1995 ), as well as analytical memos to capture their impressions and interpretations of the data (Miles et al., 2020 ). Each interview and debrief session was transcribed by the authors and they used open coding to identify underlying processes in what the participants shared (Charmaz, 1995 ). For example, Roxy said,

Okay, So I got an MBA. It was–I’ll say it was a marginal experience because of the lack of participation from the professors I had at that time. It was very much like, here's the material. It was self-driven for the most part, even though it was a hybrid, too.

The researchers coded this excerpt as valuing instructor presence . Students tend to perceive their success from their interactions with their instructor which can be a challenge for online instructors (Gnanadass & Sanders, 2018 ). Similarly, when discussing her relationships with faculty and other students, Chloe mentioned, “It feels like you're not like you're not as connected to [the faculty] as [you] need to be.” This excerpt was coded as feeling isolated . On the other hand, Tiffany described a strategy that had been helpful for her studies, saying, “I find myself reaching out more to people in my classes.” The authors coded this excerpt as connecting with peers .

The researchers coded some of the same transcripts to calibrate their application of the process codes (Creswell & Poth, 2018 ). The authors then met for second-level coding where they grouped the codes into themes and then searched the transcripts for artifacts that supported these themes (Creswell & Poth, 2018 ; Miles et al., 2020 ). For example, the above codes, valuing instructor presence , feeling isolated , and connecting with peers , were grouped into the second-level code social presence . These data were used to corroborate findings from the screen recording analysis and the faculty interviews, as well as supported in the extant literature (Aragon, 2003 ; Sung & Mayer, 2012 ).

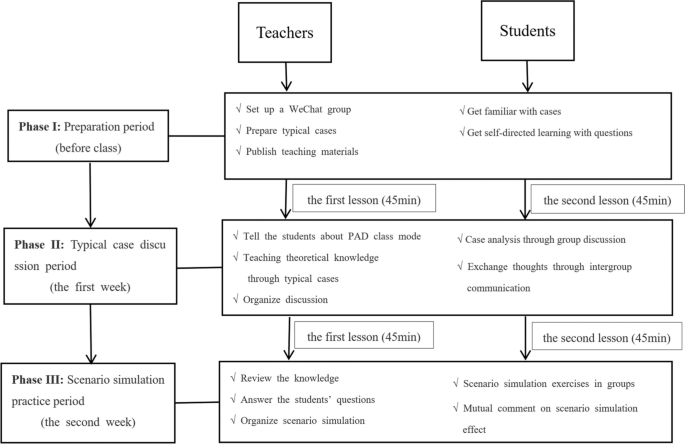

To begin the screen recording analysis, all researchers watched all of the screen recordings, documenting their noticings and questions they wanted to explore (L. M. Brown, 1997 ). The most salient theme that emerged from these recordings was the unexpected level of distraction that most of these students endured during their study sessions. With this as the focus, they went back through each recording carefully to annotate all of the embodied actions and the context that was observed through the video and audio of the screen, the student, and their surroundings (see Fig. 3 ). Excerpts were marked when the actions changed on the screen with time stamps recorded, and each excerpt was marked if a distraction was observed, regardless of whether it disturbed the student. The researchers then developed a collection of codes to mark each excerpt, labeling (1) the type of distraction (switching windows/scrolling, using a cell phone, using social media, looking away from the screen, engaging with another person, walking away from the computer, drinking/eating, movement, talking, other noise, or technology issue); (2) the type of activity they were engaged in (reading, writing/editing/creating, watching video, navigating, or self-regulation [planning, organizing, monitoring, reflecting]); and (3) the source of the distraction (self, adult, child, animal, or other) (see Fig. 4 ). The authors realized that these students were very good at ignoring many of these distractions, so they then went back to code the level of engagement during each of the distractions (continues working, stops working, or undetectable).

Screen annotation of study session clip. The first three columns in the figure show the start time, stop time, and elapsed time of the selected video clip. The next column identifies whether a distraction was observed, regardless of whether the student was distracted by it. The last column describes what was seen and heard in the recording. In this clip, the student was observed trying to watch an instructional video assigned in one of her classes but was dealing with interruptions from one of her children and technical issues of the video not loading

Coded screen annotation. The figure shows a screenshot of the coding tool developed in Google Sheets. Time stamps and excerpt numbers were cropped out in order to show the remaining columns. The columns shown include the annotation describing the excerpt and columns to mark the activity the student was engaged in, the source of the distraction, and the level of engagement in the coursework. Not shown is the type of distraction

An embodied discourse analysis approach to the videos helped to more deeply understand the phenomena observed. For example, using Gee’s ( 2011 ) The Context is Reflexive Tool to analyze the interaction between Margaret and her child during a study session described below, the researchers asked, “How is what the speaker is saying, and how he or she is saying it, helping to create or shape (possibly even manipulate) what listeners will take as the relevant context?” (p. 85). When her child asked, “Are you in a Zoom?”, it was evident that the child was aware of the need to refrain from disturbing his mother when she was in Zoom meetings and was testing for what level of interaction they could exert from her. By responding to her child, saying, “Yes. It’s recording my screen and my microphone”, she was signaling to her child that they need to not bother her, but also to be quiet so that they are not included in the recording. The participant was speaking aloud to herself about her assignment just before the child asked this question, and the participant did not look away from her screen to answer her child. Instead, she continued to stare intently at her screen, then talk to herself again about “cash conversion”. These embodied discourse signals alerted the child that she was focused on another activity and would not attend to them. By interacting with her child in this way, the participant shaped her child's understanding of the situation, providing herself with a more distraction-free study session. In contrast, most of the time when the other participants were interrupted with questions from their children, the mother stopped what she was doing and made eye contact with the child. These interactions also tended to last longer contributing to less time engaging with the course content.

This interpretation of the data was confirmed by one of the authors as she was analyzing this video clip. When she was playing the recording, her child came to sit next to her and asked, “Are you in a meeting?” The author responded, “No”, and the child began asking questions and interrupting the work. At other times, when the author alerted her child that she was in a meeting, her child would leave the room and find something else to occupy her. This finding could be beneficial to working mother students who are looking for ways to shape a home environment that is conducive to study. Helping their children to understand when they can receive the attention they need from their parents, and then reinforcing this behavior consistently, may help parents to more readily achieve the delicate balance between the roles of parent and student (Tamres et al., 2002 ).

In this section, the six cases are presented, first with the three undergraduate students and then the three graduate students. Each case will begin with a description of the working mother student, a discussion of her challenges, supports, and strategies for success, and finally, a short excerpt from one of her recorded study sessions.

Case one: Margaret

Description.

Margaret was a 35–44-year-old undergraduate student in business, taking one upper-level business course while maintaining a full-time job and parenting three school-aged children and a toddler. Margaret perceived her biggest struggle to be the time management necessary to balance her job, take classes, and care for her children. Her schedule became more “jumbled” when offices and schools closed down and went online in an effort to minimize the spread of the COVID-19 virus. She did not provide much information about her family and private life and muted her audio when someone was speaking to her, so it was not clear who or what distracted her. However, it seemed an adult male was present in the home, who was assumed to be also caring for the children while she worked at her job and her studies.

Challenges, supports, and strategies

Margaret found more flexibility in her schedule when she began working from home during the pandemic. On a typical workday, Margaret started the tasks for her job at 7:00 am, checking on her kids periodically until she took a break at 10:30 am to join her class remotely via Zoom. In past semesters, Margaret used her lunch break at work to watch the recordings of class sessions that she missed due to her work schedule. Her summer class was accelerated, so she thought it would have taken more than twice the time to stay caught up if she had to watch the class delayed. Attending class live “was huge” as it allowed her to be more engaged and to ask questions. After a quick lunch break at home, Margaret was back at work until 3:30 pm, when she would spend time with her kids and take care of some housework.

Her assignments were completed after she put the kids to bed in the evening and on the weekends. To manage her assignments, she broke them into small chunks, focusing on the items that took less time to complete first, and planning a schedule to address the more time-intensive assignments. If she didn’t have time to finish everything, she disregarded the assignments that did not have a significant impact on her grade. The researchers observed Margaret talking to herself throughout her study sessions and she remarked that this helped to maintain her focus. Margaret suggested that students in distance education should talk to their advisor about choosing “the right classes with the right instructors who are a good match for you”. She also highlighted the importance of time management and scheduling small blocks of time throughout the week so as not to get overwhelmed. Finally, she recommended that students look carefully at the syllabus to understand what is expected of them and not be afraid to ask for help when needed.

Margaret explained that her class learned about financial ratios from the text and then discussed them in class, practicing with real financial data from companies with which they were all familiar. Her final exam included an essay analyzing the finances of a corporation. There were financial ratios to calculate, which she used to support her statements in her essay. She also needed to locate recent news articles about the company and weave that information into her response. Margaret liked this kind of work. “I found that I'm able to relate my course material more to my life now in my career than I probably would have if I was in my 20's and that's been extremely beneficial,” she said. “I feel very confident coming out of [this course] being able to look at a financial report and understanding what the terms, what everything means, and, you know, when I start to invest…money in the stock market, feeling confident and picking the right companies and knowing the financial stability of the company.”

Session excerpt

In this study session, Margaret was sitting outside on a sunny late afternoon in June, working on an Excel spreadsheet. She had the 10-K financial report from Disney on her screen and was copying values into her spreadsheet to calculate ratios that determine the financial health of the company. Margaret did not appear distracted by the sounds of birds chirping or a honking horn as she talked to herself about what she was doing. She was distracted for a moment by her child, so she muted the microphone and turned to talk to them. Margaret returned to her work, and, after a few moments, her child asked, “Are you in a Zoom?” Margaret responded without looking up and continued to work. While her children were visible on the screen at several points and there were some soft noises from them at times, Margaret remained focused. Distractions were recorded during ten percent of this very focused study session.

Case two: Rebecca

Rebecca was also a 35–44-year-old woman in the business program, taking the same 300-level finance class as Margaret. Rebecca worked full-time in the finance industry and juggled a husband, three school-aged children, household responsibilities that she shared with her spouse, and several hours per week at her children’s sports games and volunteering in the community. Rebecca took a break from her studies for ten years due to her child’s illness and this was her first class upon her return. She did not think she could handle more than one class as she spent at least eight hours per week on her studies. Rebecca loved the online modality, explaining that she would not be able to return to college without the flexibility of joining class sessions remotely or watching them when she could not attend synchronously.

Rebecca completed her schoolwork at night after everyone had gone to bed to minimize distractions. She indicated that she needed structure and organization in her classes and appreciated it if the syllabus did not change throughout the semester. She would get anxious about the unknown in her classes, such as assignment details, exam content, and deadlines. Rebecca used the syllabus as her guide to work ahead on assignments and readings. She indicated that she is efficient at tuning out distractions and often works with earbuds, without connecting them to audio, to muffle background noises in the home.

If she could find periods of time to work while her family was awake, she would set herself up in a space that accommodated her specific needs to complete her school tasks. Since she lacked a private space in her house to complete her studies, such as a room and desk, she scheduled time based on the type of task and the level of distractions she could handle. For example, she found that she could complete homework if there were distractions and was able to work in a common area of her house. However, if she was studying for an exam, she would relocate to her vehicle to concentrate with fewer distractions.

Rebecca opted to record her study sessions within her home, where distractions were observed in the background. In three out of her four study sessions, Rebecca did not record her webcam, so the authors could not see what was happening around her. In those sessions, observations were made on the audio and visual cues from her computer screen, such as changing windows, typing, the movement of her cursor, and the level of her breathing, indicating when she was moving around or focused.

In the one session where she was visible, Rebecca was observed sitting in the dark at her computer. Background noises of a television and a child talking could be heard as she navigated spreadsheets. She seemed to be undistracted when a male voice joined the conversation with the child. Rebecca was observed navigating her screen from the spreadsheet and to a website while at the same time, she was whispering, singing, and humming to herself. However, she injected a comment into the background discussion, “Mom didn’t eat any,” before returning to her document to read aloud to herself. While she remained primarily focused on her work, she was still tuned in to the actions in her environment. The conversation continued in the background while Rebecca searched for information on a website. She repeated out loud, “2018,” a few times as if she were trying not to forget that piece of information. The background noises continued as Rebecca’s child called out to her. “What Bubby?” She responded to an inaudible question, “I don’t know,” and continued to work through the distractions that occurred during 85% of this study session.

Case three: Jessica

Jessica was an undergraduate student in liberal studies returning to school after a long gap due to her focus on her military career. She was working part-time while balancing life as the mother of two school-aged children and one toddler. The 35–44 year old wife was taking five classes of various difficulty levels. Jessica constantly thought of the tasks she needed to complete as a wife, mother, and student but always prioritized her role as a mother. COVID-19 had reduced her schedule because she could not volunteer or attend martial arts classes three nights per week, but also created a need for better time management when her children were learning from home. She appreciated learning remotely because the actions of students in her live classes were distracting. However, she believed the pandemic had elevated her level of distraction at home.

Jessica recently retired from the military to spend more time with her three children. She had transferred in several credits from her prior learning, so even though this was her third semester in her undergraduate program, she was well on her way to earning a degree. Jessica worked outside the home part-time, volunteered in her children’s classrooms, and taught karate three nights a week. Jessica preferred distance classes because she felt that the younger students in her live classes “just didn’t take things as seriously” as she did, and they did not want to work as hard as her. Jessica believed that toxic positivity has invaded course discussions because students were quick to avoid challenging conversations and disagreements. She appreciated discussion prompts that challenged students and their beliefs and wanted to have the tough conversations with her peers; a skill she noted as vital in life. When the instructor creates a constructive and supportive learning environment for discussions online, women learners tend to engage more, leading to deeper understanding and clarity through articulating thoughts and concepts (Gnanadass, and Sander, 2018 ).

Jessica liked to stay organized and really appreciated when faculty had materials and assignments available in advance so she could plan her busy life. Her ideal would be to be able to plan at least three weeks in advance. She had a regular routine for getting her work done so she could be available for her children, but the pandemic made things much more hectic for her. She preferred to complete her schoolwork at the dining room table but realized that this made her prone to more distraction. However, her oldest child and her husband helped “play defense to the other two” children. Her family was very supportive of her role as a student, but she still found it difficult to balance everything.

The researchers showed Jessica some clips of her study sessions and she was disturbed by one excerpt in particular. In this instance, Jessica was watching an instructional video and had paused the video to take some notes. Her children were making quite a bit of noise, and she looked up to say, “Hey, you guys are triplets! Super cool. I love it.” She looked back down to continue writing as her middle child excitedly continued to tell her something. She did not look up at him but continued to write. The youngest child jumped in to say something, and Jessica looked up to exclaim, “Your power kick? Awesome.” She immediately looked away and continued writing. When this clip was played back for her, Jessica grimaced. When the clip ended, she said, “That was my, ‘I’m really, really trying to engage with you and to give you what you need, but I can’t right now.’ That was awful.” When asked how she balanced the sometimes-competing roles of mother and student, Jessica responded that it is really rough some days. “It’s a struggle”, she said, looking visibly upset and wiping a tear from her eye. “That was really hard to watch…That was against everything that my mothering side wants to be and it’s not a good student, either.” This echoes the “dysfunctionally high standards” mother students often have for themselves referenced in the literature review section of this paper. Jessica experienced distractions during 60% of this study session.

Case four: Tiffany

Tiffany was a graduate student in social work, working full-time and balancing life as a wife and mother of a school-aged child while trying to accommodate a 16-hour internship. The 25–34-year-old was taking two graduate-level courses. Tiffany was a self-defined overthinker who appreciated big projects being broken down and actionable feedback from instructors. COVID-19 and the racial tensions playing out on the world stage made it difficult for her to focus mentally, compounded by social media, a stressor that she attempted to avoid. She found everything “overwhelming”. The majority of her coursework for her undergraduate degree was completed online; she was familiar with the expectations of the format and appreciated the flexibility. However, she was struggling to adapt to the load of graduate-level coursework.

Tiffany skimmed while she was reading, focusing only on the pertinent information needed to complete the assignment. It was an effective strategy when she was pressed for time. If an assigned reading was not necessary to complete a learning task, she typically skipped it and would circle back if time allowed. When writing, she often began with a bulleted list of her thoughts, then turned these into complete sentences in a paragraph. Tiffany’s program used a cohort model, which she found beneficial in learning study strategies and receiving support. She met regularly online with a small group from the cohort, then checked in periodically with the full group throughout the semester.

During a study session, it was common for her to switch between assignments and courses when she hit a “mental block”. Tiffany did not perceive studying in the common area of her home as a distraction for her because she claimed that she could easily tune out distractions. She reported that barking dogs and her child disturbed her the most. She felt guilty that she could not entertain her child all of the time because she was working. This is another example of “dysfunctionally high standards” and the guilt that mother students often suffer at a disproportionately higher rate than father students (Korabik, 2015 ).

It was a Thursday night in week five of the summer semester, and Tiffany was settled in at her computer to work on her online social work classes. There were nine tabs open in her browser, including a Google Doc where she listed out the learning tasks she still needed to complete this week, highlighting the ones that were most important. Her husband was behind her playing computer games, and her child was sitting quietly occupied nearby. Like many gamers, her husband had a loud keyboard and spurts of clickety-clack penetrated the quiet as Tiffany worked. Tiffany was a gamer, too, so she reported that these noises did not bother her, although she was observed rolling her eyes at some of the noises he made.

Tiffany was unsure about what she and her assignment partner had decided for their next mock therapy session, so she texted her partner and continued to work while she awaited a reply. Her child interrupted to show what they had been working on, and Tiffany turned around to look. “Pretty cool,” she said and returned to typing up her plan for the next mock therapy session.

Tiffany saw an alert icon in the task bar and opened it up to dismiss her notifications. The typing noises became frenzied behind her as Tiffany logged into Facebook. While the page loaded, she headed back to her task list and noted where each task will be: Google Docs, Microsoft Word, or the learning management system (LMS). Her child talked to themself as they played. Tiffany checked her Facebook notifications, then headed to another window to log her hours for her internship.

Tiffany navigated around applications with skill, staying focused despite the distractions of her family in the background. She smiled when her husband laughed at something her child said, so she still had one ear attuned to her family while she returned to re-read feedback from her instructor so she could clarify her next steps on the assignment. Tiffany endured distractions during nearly two-thirds of this study session. She reported that this level of distraction is typical of her study sessions. After putting her child to bed, she continued to work for a few hours. Working, taking classes, and participating in an unpaid internship meant that finding time to complete all of her learning tasks was a balancing act. Tiffany felt like she was barely getting by, but she had a nearly perfect grade point average. This is important for faculty to note as they might consider a student who appears to be “doing well” in class might not actually be “doing well”.

Case five: Chloe

Chloe was a 35–44-year-old single mom that shared custody of her young child. She was enrolled in the graduate social work program and took three 500-level classes during that summer semester. Chloe recently left her job to focus on her studies, so she was the only participant who was not currently working. However, she reflected on her experiences as a full-time working mother student in her undergraduate distance education. Because she inherited her home, she felt fortunate to have the time to devote to her graduate studies while her child was in school so that she could be available to him when he got home. Chloe needed to feel “like a part of something” and wanted to be connected to her instructors, but felt “like sometimes our teachers are too busy doing other things”. In their chapter on gender and distance learning, Gnanadass and Sanders ( 2018 ) discussed the value of social presence for the women learners and how it can be accomplished through peer and instructor interactions online. It is especially worthwhile for the instructor to keep the woman learner in mind and set the foundations in the learning environment for how students will interact with one another respectfully and provide frequent opportunities for interactions with both peers and instructor.

Chloe locked her doors, shut her phone off, and hid distractions while she completed her tasks for her graduate degree. She even closed her garage door to prevent people from dropping in unannounced. Chloe appreciated a structured course with extreme organization as she planned out her semester with a calendar, inputting due dates, assignments, and assessments at the beginning of the semester. Changes to this schedule were frustrating as her time to complete tasks was often determined by her child’s custody schedule. She liked instructors making videos that she could watch multiple times if needed and desired a supportive, communicative classroom environment.

Chloe arranged her custody schedule this year around the two Saturdays a month her classes met so she could be with her child but was surprised when the classes fell on a different week during the summer. She was required to rearrange her child’s schedule, which she was reluctant to do because she wanted to provide her child with stability. When she contacted the program coordinator to suggest that they keep the same schedule each semester, she felt that they were not responsive and did not seem to understand the impact it had on her and her family. This is an illustration of how class policy, historically developed for traditional students, does not fit the needs of parent students (Lindsay & Gillum, 2018 ).

During her study sessions, she could be inside her house in her work area or on her covered porch. Chloe was strategic about her time and also about her learning strategies. For example, she explained:

So if I read the log and the social work competencies, and then I go and I read my other books that I'm reading from my other class, I try to…connect that. I try to make a connection that way within those two readings. Because if I can do that, then it's going to be a lot easier for me to understand those competencies. Because when I read them now, I feel like they sound like a different language.

Chloe took notes and liked to highlight within the texts. In many of her study sessions she was watching and listening to videos while taking notes in her notebook, rewinding as needed to capture an important theme. Although there were background noises when she was outside, they did not distract her focus. Her eye movements and body shifting may have indicated that she was not attentive, but she was distracted in her three videos less than five percent of the time.

In this very focused study session, Chloe was completing a case study activity on the publisher companion website, copying and pasting her responses into a Word document so that she did not lose her work if her answers were not saved on the website. This was a cognitively demanding task as it required exploring several different pages with a lot of information on the screen. There were times when Chloe was reading what was on the screen, as evidenced by her continued gaze directed at the screen and intermittent scrolling, while at other times, she was scrolling more quickly and clicking back and forward through several pages, evidently looking for something. Chloe was conscientious about her work as it appeared that she was taking notes by hand as she read on the screen and was careful about her written responses. She often began typing a sentence, deleted it, and wrote something else. She also re-read her work and made edits. She periodically scrolled through to check on her responses in the other fields. In this 32-min study session, she was able to complete four short paragraphs with very little distraction.

Case six: Roxy

Roxy was a full-time graduate student in the 35–44 year-old range. She was in the social work program and was taking two upper level social work courses. She also worked full-time at a social service agency and was completing extra hours to fulfill her field placement at her place of employment. She shared custody of her young child with her ex-husband, so her child was with her four nights of the week. At the time of this research, she was seeking a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) for herself due to things she learned about herself and her mental health during the early stages of the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, Roxy had completed a master’s degree in business administration, which was a hybrid online program. She felt the professors were disconnected and not accessible which left a “bitter taste in [her] mouth”. Because of that experience, Roxy felt she did better with in person courses and was apprehensive about the social work program being online. When the pandemic occurred, her perceptions changed, and she was content with the quality of the online classes.

Roxy spent her days working in the office and found her social work courses to be very applicable to her occupation. She was not dating because she found herself asking, “Is pursuing this person worth my time where I could be spending four hours getting some writing done?” She made time every weekend to have coffee with a classmate, but the rest of her time was occupied with work, caring for her child, and schoolwork. Despite struggling with maintaining focus on her schoolwork, Roxy’s motivation and persistence aided her in completing her assignments before their deadlines. She used several strategies to compensate for her challenges, such as triplicating her notes, recording due dates and appointments on a large wall calendar, checking in with her cohort on assignments, and using color-coded post-it notes to help with recalling information.

In this study session, Roxy made revisions to an Intervention plan for one of her social work classes. Her instructor had provided feedback within the document, and Roxy was working on making the requested edits. It appeared late in the day, and Roxy said, “I’m tired” while looking at the screen. Her child was at summer camp, so she had the house to herself and did not face distraction from her child. Roxy narrated everything she did, carrying on conversations with herself or reading aloud. Figure 5 shows a short snippet of one of her study sessions where she struggled to stay focused, along with her verbal attempts to stop herself from multitasking, which were unfruitful. Approximately 30% of this session was coded with distractions created by Roxy, herself.

Screen recording annotation of a portion of one of Roxy’s study sessions. In this study session recording, Roxy attempts to refrain from distracting herself, but is also balancing other responsibilities, like meal-planning. She clearly makes several attempts to focus on the work on her screen but is struggling to remain focused

Several themes emerged when analyzing the data from these cases, including distraction, prior knowledge, cognitive load, scaffolding, and social presence. In this section, the authors summarize the responses from the faculty about their perceptions of nontraditional students and their intentions in designing their distance courses. Next, they summarize the literature on the themes and describe how these themes were evident in the data. Suggestions are provided for addressing these concerns of working mother students in the design and delivery of distance instruction.

Faculty perceptions and intentions

The three faculty members who taught the courses the participants were enrolled in shared their perceptions of nontraditional learners. Hannah, the psychology instructor, noted that her adult learners are committed and engaged, while some struggle with technology. She also explained that they tend to integrate their life experiences into what they are learning, wanting to immediately apply it in their work. This is consistent with the theory of andragogy, which suggests that adults’ “time perspective changes from one of postponed application of knowledge to immediacy of application” (Knowles, 1988 , p. 45). Hannah also said,

How they come to understand the course material is through their own life experiences in a way that …is more comprehensive and sophisticated [than] for the traditional students…they rarely default to an academic explanation; they often default to a lived experience.

Rachael, the social work instructor, also commented on the commitment of adult learners saying that most are motivated but have many challenges with juggling a lot of things. Ryan and Deci ( 2000 ), in their work on motivation, explained how intrinsic motivation, the students' tendency towards learning, can be influenced by their environment. In other words, the adult learner can be highly motivated to learn, but their commitments to work and family can compromise their learning experiences. Rex, the business instructor, supported this, explaining that they are often raising kids, working full-time, and trying to take two to four courses. He said, “They are gritty”. Hannah noticed that her online adult students did not share their challenges with her as often as her in-person adult students. She suspected that they did not have fewer problems but were more hesitant to reach out to the instructor for assistance. This was not because she was unapproachable, as she reported that students commented on the course evaluations about the extent of her presence online: “Students felt like I was right there.”

When asked about the most important consideration in their distance course design, Hannah reported that engagement made “work feel less like work”. Rachael felt that structure was the most important consideration, explaining that she scaffolded students through her course with a weekly routine. Rex privileged teaching students how to think about learning, often incorporating Bloom’s taxonomy into his lectures and discussions. His other instructional goal was to “provide students with an authentic learning experience”, such as applying course concepts to real-life businesses with which the students are familiar. He tried to “use the textbook for the underlying theory and use these companies to really bring the concepts to life”. Rex taught in a hyflex format where students had the choice of joining class synchronously in Zoom or watching the recorded sessions and completing assignments asynchronously. He admitted that he did not know what the learning experience was like for those students who participated asynchronously and did not adjust his instruction based on age groups. “I teach the class the same.” This is consistent with other research that suggests that while faculty do acknowledge that adult students have unique needs, they do not teach their traditional and non-traditional students differently (Donavant, 2009 ; Panacci, 2017 ). While the faculty estimated that students spent about three to four hours on their class each week, students reported spending significantly more time (Yin & Lim, 2020 ).

Understanding the learner

Using this case study method allowed for better understanding of each learner. It is clear from the science on learning that each learner is unique and brings a unique combination of strengths and weaknesses, as well as interests, background, and knowledge (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018 ; Pape, 2018 ). Adult learners, including working mother students, have accumulated more life experiences and knowledge, and are even more variable as learners (Berker et al., 2003 ; Chen, 2017 ; Fairchild, 2003 ; MacDonald, 2018 ), so understanding them is especially important for the design of distance learning that includes nontraditional students. Understanding the lived experiences of learners is especially important during stressful situations like the COVID-19 pandemic. In this section, the authors describe the salient factors that were observed from the working mother students that are important for their success as learners.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic

In this study, students reported both positive and negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on their home and student life. It was a challenge for almost all of them to readjust and find balance as work and school impinged on their home lives. Across the United States, university students reported lack of motivation, fatigue, and isolation (Browning et al., 2021 ). At the same time, low infection numbers in rural communities, such as the one where this study was conducted (Fehr et al., 2020 ), may have caused comparatively less stress associated with avoiding infection than for those in urban areas. Some students welcomed the events of public entities shutting down, which opened up time and provided flexibility to go back to school and to complete course work. For example, Chloe explained how the pandemic encouraged her to return to school full-time.

I felt like this is a lot of work. And I'm going to have to be a hermit crab. And in 2020, everybody had to be a hermit crab…I might as well do it, too. But I didn't want to be around classmates…because there weren’t any vaccines at the beginning.

However, for others, the lifestyle changes the pandemic produced made it hard to manage time and maintain focus on their schoolwork. Jessica described how school closures magnified her struggle.

I knew that on certain days I got to [take] my youngest to daycare and I had that day to do schoolwork, whatever. That doesn’t happen anymore. So I have to be much better about time management, which sometimes gets me.

Tiffany also was challenged with the added role of home-schooler.

My [child] stopped going to school in March, so we’ve been doing distance learning for [them] ever since March, trying to make sure [they have their] zoom classes set up, making sure [their] homework’s getting done. And we try to teach [them] while still working full-time from home. Still trying to keep up on classwork. That just made things more overwhelming. But luckily, I was still able to work. And that was stressful.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was different on each one of the learners in this study, but for the most part, it added to their already-full plate of responsibilities. It should be noted, however, that most of the mother students in this study down-played the amount of stress they were under when talking about all of these challenges. From our perspective, it seemed as if these participants were so used to being overwhelmed by juggling so many responsibilities that the additional challenges created by the pandemic did not appear to change the amount of overwhelm.

The pandemic heightened inequities in rural colleges (Ratledge et al., 2020 ), such as the digital divide. While none of the participants reported lack of access to broadband internet, there were several instances in Jessica’s study session recordings where she waited inordinate amounts of time for pages to load (see Fig. 3 ). Aristeidou and Cross ( 2021 ) found in their research on distance education students that the difficulty in managing workload and minimal student interactions were predictors of negative impacts of the pandemic. They further implied that it was no surprise when a lot of off-campus students were faced with being the sole childcare provider for their children when schools and childcare facilities closed.

The three graduate students in this study discussed their experiences of staying connected with their student cohort, which was formed before the pandemic, through social media and instant messaging. This strategy kept each of the students engaged and on top of the schoolwork (Fenning, 2004 ). Two of the graduate students discussed the difficulties with staying focused, so they utilized strategies to combat their challenges. Outside of family life, each having one child, they all believed it was important to stay within their school bubble and isolate themselves from regular social routines or shut out outside world events in order to be “successful” in balancing work, school, and home life.

Similarly, the three undergraduates, who were all mothers of multiple children, three to four each, all kept a tight schedule with balancing school, work, and home life. It is possible the undergraduate students may have welcomed interaction with a student cohort like the graduate students, but limited time for connecting with others outside of the home may have been a challenge with more children. Managing time became a priority for the mothers, and one mentioned that she welcomed the change of going online for all of her classes so she had minimal interactions with other students. Regardless, for both graduate and undergraduate students, they prioritized time with their children and found ways to complete their school work.

Distraction

Household and family obligations contributed to the majority of the distractions these working mother students experienced during online learning, although the student was their own source of distraction at times, too (Blasiman et al., 2018 ; Hollis & Was, 2016 ; Scanlon, 2009 ). The study participants had multiple responsibilities outside of the classroom, such as jobs, housework, volunteer activities, and family. These life obligations often interrupted their schoolwork, and often occupied their minds throughout the week. However, there were some distractions the participants were able to ignore, such as the dog barking, people talking, and the television playing in the background. To mitigate the impact of distractions, one participant continued to look at the computer screen when their child asked a question. The participant quickly responded to their child, then read out loud to herself to help focus on her class materials. Gazzaley and Nobre ( 2012 ) refer to this strategy as selective attention, or effortful attention, to help maintain information in the working memory.

Selective attention can be defined as “goal-directed focus on one aspect of the environment, while ignoring irrelevant aspects” (Gazzaley & Nobre, 2012 , p. 129). While students are engaged in coursework, they need to maintain information in working memory as they work through a learning task. Distractions during this task will diminish working memory performance, but selective attention predisposes the brain to select incoming sensory information that is relevant to the information in working memory and ignore irrelevant information (Gazzaley & Nobre, 2012 ; Petersen & Posner, 2012 ). Interest in the content or a relevant goal for completing the task can reduce the demands on attentional resources, making it easier to learn the content (McDaniel et al., 2000 ). Jessica commented on the challenges she had when focusing on the instructional videos in her marketing class compared to her psychology class because she was less interested in that content and found it less relevant to her personal and professional life. Rose ( 2010 ) suggested that short of developing courses like action video games that innately capture student attention, it is important to develop metacognitive and reflective designs that help learners understand the limits of their attention and encourage deep engagement with the content.

Another phenomenon observed in this study is the ability to recover from distractions. Clapp et al. ( 2011 ), discussed in their article the length and process it takes an older adult to re-activate their working memory which is longer in contrast to the younger adult. They noted that “unlike younger individuals, older adults failed to both disengage from the interruption and reestablish functional connections associated with the disrupted memory network” (p. 7212). The ability to switch focus between tasks declines with age, making the effect of disruptions greater on adult learners. The researchers observed this in the participants in this study. For example, when the participants experienced a distraction that required their attention, there was often a visual pause on the screen, or the participant would go back and read aloud the previous sentence before continuing to type. Not only did distractions detract from the total available study time, but they also resulted in additional work for the students.

Prior knowledge and learner pacing

Understanding the role of prior knowledge is essential in designing instruction. New information and experiences are processed through the lens of prior knowledge (Bransford et al., 2000 ) and are incorporated into existing mental schemas during consolidation of memory (Tse et al., 2007 ). Activation of prior knowledge may be especially important in adult learners as crystallized intelligence continues to grow throughout adulthood while processing speed and fluid intelligence declines (Horn & Cattell, 1967 ; Murman, 2015 ; Salthouse, 1996 ). These challenges can be mitigated by the freedom of the learner to pace their learning (Beier & Ackerman, 2005 ; Callahan et al., 2003 ). While the work of Beier and Ackerman and Callahan et al. was conducted on a range of adults, this was consistent with the working mother students in this study. In this section, the authors describe findings from the cases to illustrate how the participants made use of their prior knowledge to help them learn course content and paced their studies to accommodate the challenges of slower mental processing and increased levels of distraction.

Holistic data from the student interviews and video coding showed participants using techniques they developed from prior knowledge and applying pacing strategies that allowed them to be successful and minimize distractions. All of the participants noted that connecting their learning to life experiences and their everyday work helped them to be successful in their coursework. Some students found it helpful that course content related to what they had already experienced in their lives or things that they had discovered through their work experience. While Jessica enjoyed her psychology course, she struggled with the marketing class as she had no background in this content area and much of it seemed irrelevant to her needs as an adult (Knowles, 1988 ).

Rebecca explained that her background knowledge had helped in learning the course content. “I'm really feeling like so far, it's a lot of what I already know and what I do at work every day. So, it's a really good confirmation that I know my job. I learned a lot.” Rebecca connected this new knowledge with prior knowledge which has been shown to predict acquisition of related content (Simonsmeier et al., 2022 ). “I work with a lot of analysis ratios and I’m anxious to see if there's any new ones I can add to my tool bag. That's where I get a little geeked out.” Margaret and Rebecca both commented on how helpful it was that their instructor used real financial data from businesses they were familiar with to illustrate concepts they were learning in class (Lave & Wenger, 1991 ; The Cognition And Technology Group At Vanderbilt, 1990 ).

In situations where students felt disconnected to the content, they motivated themselves to get into a positive frame of mind. Roxy described how she had to work herself up for learning particular content in a course where she had no background and no perceived use for this new information. She also found anything historical to be boring. “I’m going to psych myself up to get through this class. [This law] from 1968 is so amazing and I want to learn all about it,” she said, trying to convince herself that it was relevant to her work and important to learn. Knowles ( 1988 ) suggested that relevance and immediacy of application are important considerations for adult learners. Some students used course rubrics and worked backwards to complete assignments or used assignment specifics to schedule time for reading around the information needed to complete tasks. For example, in her self-evaluation assignment, Tiffany copied the success indicators from the rubric into a new document and began to paraphrase them to detail how she was meeting the criteria.