An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Re-Thinking the Role of Government Information Intervention in the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Agent-Based Modeling Analysis

1 Dong Fureng Economic and Social Development School, Wuhan University, Beijing 100010, China; nc.ude.uhw@7009oayul

2 National School of Development, Southeast University, Nanjing 210000, China; ude.olaffub@hziqoaix (X.Z.); ude.dccws@3210801fk (H.L.)

Xiaoqi Zhang

Yanqiao zheng.

3 School of Finance, Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics, Hangzhou 310018, China; moc.liamtoh@oaiqnaygnehz

Associated Data

The data presented in this study are available on request of the authors.

The COVID-19 pandemic imposes new challenges on the capability of governments in intervening with the information dissemination and reducing the risk of infection outbreak. To reveal the complexity behind government intervention decision, we build a bi-layer network diffusion model for the information-disease dynamics that were intervened in and conduct a full space simulation to illustrate the trade-off faced by governments between information disclosing and blocking. The simulation results show that governments prioritize the accuracy of disclosed information over the disclosing speed when there is a high-level medical recognition of the virus and a high public health awareness, while, for the opposite situation, more strict information blocking is preferred. Furthermore, an unaccountable government tends to delay disclosing, a risk-averse government prefers a total blocking, and a low government credibility will discount the effect of information disclosing and aggravate the situation. These findings suggest that information intervention is indispensable for containing the outbreak of infectious disease, but its effectiveness depends on a complicated way on both external social/epidemic factors and the governments’ internal preferences and governance capability, for which more thorough investigations are needed in the future.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has attacked the whole world over the past few months. The key features of the Novel Coronavirus, such as long incubation period, high infectiousness, and asymptomatic transmission, were not perceived at the beginning until they were gradually unveiled [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. The WHO and governments keep disclosing epidemic information, but the disclosure is based on their own endowments, preferences, and perceptions, resulting in misleading information at least in the early stage of COVID-19 outbreak, such as “Masks work? NO” (quoted from Scott Atlas, the White House coronavirus task force member), “This is a flu. This is like a flu” (quoted from Donald Trump, the president of the US), and “There is some immune system variation with Asian people”(quoted form Taro Aso, the Deputy Prime Minister of Japan), etc. This information failed to alert the public but let their guards down instead. Then, the high mortality rate and emergency announcements subsequently incited widespread fear and exacerbated the epidemic situation. Theoretically, a systematic provision of timely and effective information from the government can mitigate the downsides [ 5 ]. However, in the real world, speed entails inaccuracy and cognitive uncertainty that keep government away from accomplishing such a tough mission [ 6 ]. Thus, in the early stage of an epidemic with strong externalities like COVID-19, the government’s choice between timeliness and effectiveness of intervention strategies raises a theoretical challenge for the management of urgent public health crisis.

The key to successfully contain the spread of an unexpected disease like COVID-19 is to understand the complicated two-way interaction between the dynamics of disease and those of information (and the human behavior response to information) [ 7 ]. Information might either amplify or diminish the public’s response to a risk event, depending on the transmission of risk information and public’s reactions at the time it occurs [ 8 ]. At the micro-level, one’s behavior depends on the epidemiological status of the disease, the individual’s knowledge about it (information accessed), misinformation, and the individual’s education and income level [ 9 ]. Along with the spread of disease in social life (physical level), information spreads in a virtual network, which brings the awareness of crisis for people [ 10 , 11 , 12 ], leading them to take preventive measures to stay healthy [ 13 , 14 ]. Therefore, the spread of disease facilitates the spread of information, which in turn inhibits the spread of disease [ 15 , 16 ]. However, on the other hand, people usually get illogical, fail to discern falsity, and disregard the truth during information dissemination [ 17 , 18 ]. Misleading information seems to have a natural disposition to resonate with public opinions, which causes spontaneous misrepresentation in transmission [ 19 ]. In addition, discussions on epidemic bring panic [ 20 ] and aggravate the harm of the epidemic [ 21 ], which will be further exaggerated by social media [ 22 ]. Meanwhile, increasing uncertainty about the disease makes people feel loss of control and boost people’s anxiety [ 23 ], usually accompanied by psychological distress [ 24 ]. Therefore, information is critical to fighting against the COVID-19-crisis [ 25 , 26 ], and improper information management strategy may lead to systematic failure [ 27 ].

The government, as the main governing body, is the most critical (information) node in the entire network, since it can intervene in information by “blocking” [ 28 , 29 ] and “disclosing” [ 5 , 30 ]. The minimal blocking implies a free and open information environment, which stimulates information to be widely diffused and induces more people to take self-protective measures [ 31 ], but “rumors” might also proliferate at the mean time [ 24 ]. Even if (under certain premises) some “rumors” are accurate [ 7 , 32 , 33 ], it might still interrupt the prevention efforts to the epidemic. It is always believed that government should perform as a central node to disclose accurate and up-to-date information to the entire society, so as to keep the public away from untruthful information and prompt the public to make informed decisions about health protection [ 30 , 34 ]. However, in the real world, governments do face time constraints and the trade-off between being accurate and being up-to-date in terms of information disclosing, which is not considered in classical information theory. Because a highly infectious disease caused by unknown viruses with great externality, such as COVID-19, spreads together with information of varying qualities (truthfulness, accuracy, etc.), it is highly probable that the disease has already contaminated the society before low-quality information is purged. In this case, the government has no way to disclose accurate information in time, resulting in the loss of public trust and raising the doubt of the public on the governing capacity of the government, which will accelerate epidemic outbreak [ 35 , 36 , 37 ]. Therefore, governments need to not only decide when to inject information into the network, but also whether to follow the tenet that governments do not and should not block information spreading at any circumstance [ 38 ].

For information blocking, studies have been conducted in theoretical [ 39 , 40 , 41 ], in empirical [ 42 , 43 ], in case studies [ 43 , 44 ], and other perspectives. These studies argued that, even if governments have the power to control information [ 45 ], they should not do that because free spread of information is essential to welfare-maximizing [ 38 ]. This argument is based on two underlying assumptions: (1) publishers are completely competitive to reach an equilibrium of disclosing accurate information; (2) there is no time constraint. These two assumptions do not apply for COVID-19 because, in the age of Internet media, people are not incentive compatible to spread accurate information. Moreover, such highly externalized infectious diseases caused by unknown viruses might have already infected a considerable amount of people before low-quality information is purified, so the government should not simply adhere to the tenet of not blocking information when facing an unknown health crisis [ 38 ]. As a result, we will discuss the complexity and diversity in information blocking and broaden current information control theory.

By the discussion so far, we notice that the successful containment of epidemic outbreak relies on the successful management on the information dissemination process, which, however, is hard to achieve in the real world. To better understand the failure in containing the COVID-19 pandemic, we here construct an information-behavior bi-layer model by adding a parallel layer of information transmission to the classical SI (Susceptible-Infected) model of infectious diseases. We intend to describe the effect of heterogeneous virtual information (at information layer) on heterogeneous nodes’ behaviors (at physical layer) [ 46 ]. The government, as the key node in information network, can influence the entire network through information disclosing and blocking. Based on this, we assign values to key variables such as the medical awareness level of the virus and the public’s health awareness level and then conduct computer simulation experiments under different scenarios. We reveal the pattern of government information intervention based on the simulation results. In addition, we only focus on the emergence stage of the infectious disease, during which the recovery from the infected status, such as self-healing and cure of the disease, is omitted [ 47 ]; therefore, the base model is the SI model rather than the SIR (Susceptible-Infected-Recovery) model.

Based on the bi-layered network model, we explore two main themes: how disease spreads affect information spreads and how information affects the efficiency of controlling the epidemic. We introduce the non-dualism of information and the heterogeneity of nodes’ behaviors into the epidemic model and conduct a simulation to reveal the information intervention dilemma faced by the government between information disclosing and blocking. We find that governments face a trade-off between speed and accuracy in information disclosing; and the optimal strategy is contingent on varying conditions in information blocking. The optimal combination of disclosing and blocking is highly sensitive to the government preference and its governance capacity. Governments that are only responsible for the outcome of intervention will focus unilaterally on the accuracy at the expense of speed; a risk-averse government that intends to minimize the maximum infection rate under uncertain scenarios will impose a more restrictive blocking; and the most restrictive blocking strategy might be the best for governments with lower capability and credibility.

In summary, this paper makes several important contributions to the literature. First, existing studies did not pay sufficient attention to the spread and evolution of rumors during a public crisis [ 48 , 49 , 50 ], which is considered in our study. We expounded the impacts of information dissemination on epidemic evolution in scenarios with different levels of medical awareness of the virus, public health awareness, and government preferences and credibilities, which complements the research in this field. Second, most current studies regard information and disease transmissions as simultaneously happened and jointly induced by the physical movement of an agent [ 46 ], while this is not the case during COVID-19 pandemic as the internet obviates the needs for physical contact in information transmissions [ 51 ]. Thus, in our paper, we separate the information and disease transmissions and investigate the impact of heterogeneous information on the individual behaviors and disease dynamics. Third, unlike previous research on government information interventions with known risk [ 5 , 28 , 29 , 30 ], ours are on government information interventions with unknown risk. The lack of prior knowledge on the Corona-SARS-2 is the most striking feature of the COVID-19 pandemic, which weakens the usefulness of government action and calls for a reassessment of government information intervention under a crisis environment with high uncertainty. To this end, this paper demonstrates a couple of intervention dilemmas faced by government, which complements the existing theories.

2.1. The Model of Information Disclosing

The information dissemination system resp. behavioral response system is embedded in the information network resp. physical network. Both networks are given as follows.

Information network: the network has ( N + 1 ) nodes, first N are individual nodes representing N individuals denoted as i , i = 1 , 2 , ⋯ N , and one government information node denoted as j . The degree of an individual node i is denoted as y i , which obeys a power-law distribution, that is, F y i ∝ y i − v , where F ( · ) is the CDF and y i satisfies ϵ ≤ 1 ∕ y i ≤ 1 , where ϵ is a small constant to avoid the degree to blow up. Degree and degree distribution are concepts used in graph theory and network theory. A graph (or network) consists of a number of vertices (nodes) and the edges (links) that connect them. The number of edges (links) connected to each vertex (node) is the degree of the vertex (node). The degree distribution is a general description of the number of degrees of vertices (nodes) in a graph (or network), and, for random graphs, the degree distribution is the probability distribution of the number of degrees of vertices in the graph, which usually assumes a power-law distribution. Throughout the following analysis, we take v = − 1 and ϵ = 0.01 . The government node j (representing real-world government) discloses information to every individual node and can only obtain information from n 1 ( n 1 ≪ N ) (The notation “≪” means that the number n 1 must be far less than the number N.) random nodes. The neighborhood of an individual node i is the set of all other nodes (including j ) it connects with, denoted as O i .

Physical network: the physical network has M nodes, including n 2 “special” nodes defined as the “gathering spots”, which predisposes these nodes to this epidemic. M t denotes the distribution of locations of all N individuals during period t , and M 0 is the initial distribution that can be viewed as the “home” for every individual (node), thus at the beginning of each period t the individuals move from M 0 to M t and return back to M 0 at the end of period t . Home coordinates M 0 and gathering spots are randomly assigned and different from each other, so we have N + n 2 < M . Suppose there are n 3 random nodes, each with identical initial information ξ , who disseminate information at the outbreak of disease; n 4 random nodes are initially affected by the public crisis, representing the “patient zero”.

Without loss of generality, we unitize the information between 0 and 1. The rules for information dissemination in each period are as follows.

Stage i. Individual nodes send information to neighbors . Each node that has information at the beginning of each period sends its information to all its neighbors, so all ( N + 1 ) nodes might receive information from others. As information is spontaneously [ 19 ], rapidly, and extensively [ 22 ] misrepresented during transmission, and most people do not send more accurate information than they receive [ 17 , 18 ], we assume that information gets distorted and misrepresented during each transmission. Thus, the actual amount of information received is δ x i due to information decay, where δ ∼ U ( 0 , 1 ) , and we assume x i ∈ 0 , 1 without loss of generality.

Stage ii. Individual nodes receive information from neighbors . Each node might have multiple information sources, and it merges the information from all its neighbors weighted by their degrees (and including itself). Each individual updates its information based on Equation ( 1 ) at each period before the government intervenes:

Stage iii. The government node censors and screens the information . The government has a threshold X D once it receives information from individuals (otherwise, the government would not act in this stage), the government will screen out all individuals with above-threshold information at the beginning of current period, among whom the government pinpoints the nearest ones and takes the maximum amount of information they carry denoted as x d .

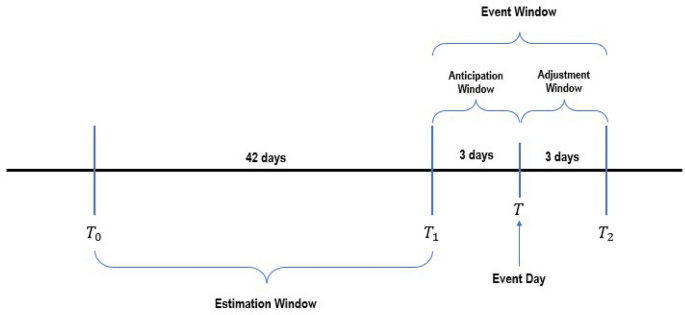

Stage iv. Government node discloses information . The government is not able to intervene until it censors and screens the information; thus, there is a lag between receiving information and disclosing, which as we can see in Figure 4e, increases with X D . After the lag (otherwise, the government would not act in this stage), the government shall disclose x d to all nodes in each period with a weight of λ , where λ ∈ 0 , 1 . The higher the λ , the more credible the information.

Stage v. Individual nodes update information again . The government intervention switches the updating rule to

which is also the final amount of the information after government intervention. In addition, we assume that the amount of information of initial information holders (those who have information in period 0) is constant, i.e., they do not apply for Equations ( 1 ) and ( 2 ).

In short, in the first period, only a few people disseminate information, which will be randomly decayed in each subsequent period, this process simulates the misrepresentation of information.

Twitter data show that there was a significant heterogeneity in the behavioral response to the COVID-19 epidemic [ 52 ]. Some people, once informed about the epidemic, wear a mask and practice social distance to not expose themselves to the virus—while others panicked, herded, and behaved irrationally because of bad news, exemplified by flocking to churches for psychological comfort [ 53 ], to supermarkets for daily supplies [ 54 ], and taking radical actions like repeated hospital visits [ 55 ]. Thus, in this paper, we group the population by susceptibleness to irrational behavior caused by information described by an exogenous parameter—individual threshold X I that distinguishes whether an individual is panic-prone or non panic-prone by comparing it with the amount of information the individual has. An above-threshold (under-threshold) information denotes a (non) panic-prone individual. For a panic-prone node, we assume its probability of going to gathering spots instead of maintaining the original trajectory is 1 − x · , a , where x · , a is the amount of information it has. For a non panic-prone node, we assume that its probability of not moving is r · , N = x · , a . Thus, the behavioral routine is as follows (see Figure 1 for a simplified example): a node moves along with its path with a maximum radius d 1 , and the actual distance it moves obeys a uniform distribution in ( 0 , d 1 ) ; this node will randomly choose one of the gathering spots if intending to go to one in this period; every individual node follows this routine, then we have an evolving geographical distribution M t of the population moving in period t . The uninfected will contact everyone within the maximum infection radius d 2 and there is a probability μ of being infected for each contact.

A diagram for individuals’ behavioral routine. Consider a world with 36 nodes ( d 1 = 2 , d 2 = 1 ), among which there are only one infected node (S), one health node (H) and one gathering spot (G).

Throughout the simulation analysis, we focus on the impact of three key parameters, the initial information ( ϵ ), individual threshold ( X I ), and disclosing threshold ( X D ), which are the most important quantities to measure the impact of government intervention on the coupled information-disease dynamics. The initial information is the source of all information, which denotes the medical awareness of the virus; the individual threshold is a parameter to distinguish the population by groups set above, the smaller it is, the higher the level of public health awareness. Disclosing the threshold, chosen by the government, measures its relative priority to speed and accuracy in information dissemination. One of the objectives of our experiment is to ascertain the optimal disclosing threshold. Government prioritizes speed more as its threshold is lower, “0“ means that government discloses the information immediately upon receipt; “1” means that government only discloses completely accurate information.

2.2. The Experiments of Information Disclosing

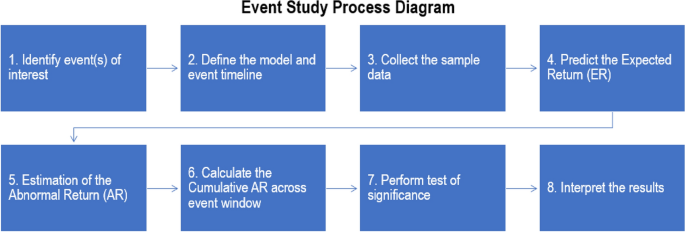

The simulation steps will be: ( Figure 2 brief overviews these steps):

- Generate a random information network and a random physical network, the former illustrates the information relationship between people, and the latter records the coordinates of people M 0 and gathering spots on the map.

- Assign values to initial information and individual threshold. The initial information is the source of all information, which denotes the medical awareness of the virus; the individual threshold is a parameter to distinguish the population by groups set above; the smaller it is, the higher the level of public health awareness.

- Assign values to the disclosing threshold. The disclosing threshold, chosen by the government, measures its relative priority to speed and accuracy in information dissemination. One of the objectives of our experiment is to ascertain the optimal disclosing threshold. Government prioritizes speed more as its threshold is lower.

- Generate random individual nodes with initial information and random initial infected nodes.

- (a) Each individual node with information sends out information to neighbors.

- (b) Each individual node will update its information (weighted) based on Equation ( 1 ).

- (c) The government initiates a censoring and screening and enters stage d after a lag period, only for the first time does it receive the above-threshold information. If the government never receives above-threshold information, skip c , d , and go to e .

- (d) Government discloses information to the public, which induces another round of information update for individual nodes based on Equation ( 2 ).

- (e) The population is grouped into infected and healthy people by health status, and into panic-prone and non panic-prone by how much information one has compared with the individual threshold.

- (f) Each individual node moves in a physical layer following the routine of the subgroup it is in with probability based on its final information.

- (g) Reset the infection status of healthy individual within the transmission radius of an infected one according to the infection probability.

- Return to step 5, initiate a new round for 50 times, that is, run the experiment for 50 periods. The data show a stability after 40 periods, so we stopped at 50.

- Output the final overall infection rate at the end of period 50.

- Repeat steps 4–7 for 50 times to reduce the randomness, record the mean, and standard deviation of the final infection rate.

- Reassign for the disclosing threshold discrete values that equally divide the interval 0 , 1 into 11 parts, and repeat steps 3–8 for each value, that is, 11 times, to find the final infection rates for different disclosing threshold scenarios.

- Reassign for initial information a discrete array 0.4 , 0.6 , 0.8 , 1.0 , and reassign for an individual threshold the same values reassigned for the disclosing threshold in the previous step. Then, repeat steps 2–9, that is, 44 times.

Flowchart of our simulation. In step ii, we assigned 4 × 11 × 11 = 484 different values. Then, we repeated steps iii and iv each for 50 times, respectively.

Now, we have conducted an experiment with a full parameter space for each initial condition. A total of 484 different conditions were simulated for 24,200 repetitions of the experiment, each lasts for 50 periods, which adds up to a total of 1,210,000 periods of experiments. They essentially cover all possible scenarios under different external constraints. Table 1 lists the definitions, values, and distributions of all parameters in the model.

Definitions, values, and distributions of variables in the model.

2.3. The Model and Experiments of Information Blocking

We assume the government will suppress any transmission of information under X B ; thus, X B = 0 denotes the special case in the previous discussion. Combining the blocking threshold with other initial conditions above, we have a new parameter space simulation with a total of 5324 different scenarios simulated and a total of 266,200 repeated experiments. Each group lasts for 50 periods, for a total of 13,310,000 experiments.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. modeling framework.

Our model consists of two main systems: information dissemination system and behavioral response system. In the information dissemination system, each individual sends (receives) information to (from) its neighbors through an information network. Given that information will always be rapidly, extensively [ 22 ], and spontaneously [ 19 ] misrepresented during transmission, and that most people do not send more accurate information than they receive [ 17 , 18 ], we assume information gets distorted and misrepresented during each transmission. In the behavioral response system, each individual makes a move according to its information (with probability). Once informed about the epidemic, some people behave rationally such as practicing social distancing, while others behave irrationally such as flocking to churches [ 53 ], to supermarkets [ 54 ], and taking radical actions like repeated hospital visits [ 55 ].

The information dissemination system affects the behavioral response system. The government might intervene in the information dissemination to reduce infections by either disclosing or blocking information.

For information disclosing, the government discloses information to all individuals to make them behave rationally (or at least not behave irrationally). Obviously, the more accurate the information is and the earlier it is disclosed, the public can be better guided which lowers the final infection rate. However, it takes time for government to censor and screen information before disclosing, which brings an accuracy-speed trade-off. We use a disclosing threshold to measure the government’s preference on speed or accuracy; a higher threshold indicates a higher preference on accuracy: a threshold “1” means the government would not disclose any information unless it is completely accurate; while “0” indicates an immediate disclosure without any censoring and screening.

For information blocking, the government blocks less-accurate information transmissions between individuals. Obviously, a stringent blocking leads to a transmission of information with higher accuracy. However, blocking will slow down the overall information dissemination in the network, and then slow down the government’s censoring and screening of information. Thus, there is a trade-off between disclosing and blocking. We use a blocking threshold to measure the blocking stringency, the government would block any transmission of any under-threshold information: a threshold “0” means no blocking at all; while “1” means that government blocks all information transmissions.

We analyze both of the optimal thresholds for government. More details on the settings of our model can be found in the Methods section. In reality, the government has a great influence on the information dissemination. Thus, in our model, we assume that the government node is the most critical one and the government-disclosed information highly outweighs individuals’ information (except for the further discussion of a government with low credibility in a later section).

3.2. Intervention Dilemma in Disclosing Information

In this part, we will discuss the speed-accuracy trade-off results and analyze the mechanism in information disclosing.

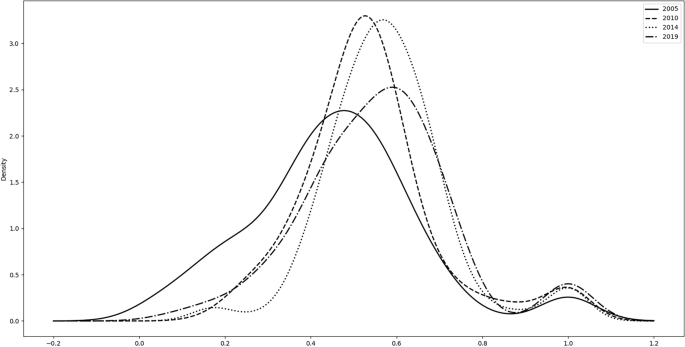

First, Figure 3 summarizes the results of the simulations with 44 different external constraints, and we find that there is seldom a single dominant disclosing threshold (the government’s preference on speed or accuracy), i.e., seeking either speed or accuracy alone will not result in the lowest infection rate, and the optimal strategy (corresponding to the lowest infection rate at the end of the last period) is somewhere in between, which implies a speed-accuracy trade-off.

Distribution diagram of disclosing threshold. These four subfigures ( a – d ) correspond to initial information of 1, 0.8, 0.6, and 0.4, respectively, each one has 11 curves representing individual thresholds of all 11 values, which shows the optimal disclosing thresholds under all 44 different external constraints. The horizontal axis is all possible values of disclosing thresholds, the vertical axis is the infection rate of the whole society.

Specifically, the optimal disclosing threshold lies between both ends in about 84.09 % of the cases, and their distributions vary in different external constraints. Figure 3 a,b show that (1) if the initial information is 1 or 0.8 and the individual threshold is in [ 0 , 0.7 ] , the optimal disclosing threshold has a 91.75 % probability of being in the middle, and mostly ( 66.89 % ) falls within [ 0.6 , 0.8 ] ; (2) if the initial information is 0.6 and the individual threshold is in [ 0 , 0.5 ] , the government has a 93.00 % probability of dealing with a trade-off ( Figure 3 c), and the optimal disclosing threshold mostly ( 77.78 % ) falls in [ 0.4 , 0.6 ] ; (3) if the initial information is 0.4 , the optimal disclosing threshold will almost certainly be greater than 0.4 ( 99.98 % ), but the distribution is too scattered to give a specific interval ( Figure 3 d). The mode of optimal disclosing threshold is 0.8 but only with 20.30 % frequency.

In addition, we can see that, if the virus is medically well-known ( ξ ≥ 0.8 ) and public health awareness is low ( X I ≥ 0.7 ), the government shall prioritize accuracy over speed; if the virus is medically medium-known ( ξ = 0.6 ) and public awareness is high ( X I ≤ 0.5 ), the government shall balance speed and accuracy, which almost equally signifies; and if the virus in medically less-known ( ξ = 0.4 ), the government shall probably prioritize accuracy over speed.

Second, we will dissect the underlying logic and mechanism of the government’s trade-off. We take one of the curves in Figure 3 a that is denoted by ξ = 1 and X I = 0.5 , as an example, to find the relationship between disclosing the threshold infection rate, then we have Figure 4 . In all 550 ( 11 × 50 ) experiments, the disclosing threshold for the lowest final infection rate usually lies between 0.7 and 0.9 , and the final infection rate first falls then rises as the disclosing threshold increases, with the inflection point being at 0.8 ( Figure 4 a); the amount of final information per capita and the duration of government intervention both increase monotonically with the disclosing threshold ( Figure 4 b,e); the number of people infected after government intervention, the number of people infected by a panic after government intervention and the number of uninfected people remaining at the time of government intervention all negatively correlate with the disclosing threshold ( Figure 4 c,d,f).

Simulation results for government’s trade-off in disclosing under the special case of ξ = 1 , X I = 0.5 . ( a ) depicts final infection rate; ( b ) conveys the impact of disclosing threshold on information; ( c , d ) represent the positive effective of a larger disclosing threshold by showing the new infections overall or from panic after government intervention; and ( e , f ) describe the negative effect by showing when the government intervenes and how many health people remained at intervention.

One of the fundamental reasons for the government to balance speed and accuracy is the precipitous fall in the marginal contribution of accuracy as the disclosing threshold exceeds a certain “point”, while speed hardly affects the final infection rate. The following is a detailed analysis on the effects of both accuracy and speed.

With respect to accuracy, the effect comes from two perspectives: (1) accurate information lowers the infection from panic in a healthy panic-prone population ( Figure 4 d); (2) accurate information changes the behavior routine in the panic-prone population, which reduces the spread of the disease. Both (1) and (2) are in play until the disclosing threshold exceeds 0.5 ( X I in our example); after that, there is no longer a panic-prone group, neither is infection from panic, which explains the precipitous fall in the marginal contribution of accuracy.

When it comes to speed, the effect comes from two perspectives as well: (1) the time the government spends on censoring and screening information, which we call a lag; (2) the number of remaining uninfected people at the time of government disclosing information. The more accurate information the government seeks, the longer the lag ( Figure 4 e) and the fewer uninfected people remain at the time of disclosing ( Figure 4 f). Notice that both have roughly the same slope with respect to disclosing threshold, which explains a roughly constant marginal cost of pursuing accuracy.

The combination of constant marginal costs and abrupt fall in marginal benefits leads to an inflection point in disclosing threshold, which explains the heterogeneity in the distribution of optimal disclosing threshold: as disclosing threshold exceeds individual threshold, a sudden fall of benefits occurs, which theoretically makes the optimal disclosing threshold slightly greater than the individual threshold, which explains what we discussed above that the intervals in which the optimal disclosing threshold mostly lays differ.

In most cases, the government’s premature disclosing of inaccurate information will contaminate the overall network, while obsession with accuracy may have the government miss the disclosure window before too many people are infected, which is intolerable to government who requires a low infection rate. Thus, there is a trade-off.

3.3. Intervention Dilemma in Blocking Information

We assume the government will block any transmission of under-the-blocking-threshold ( X B ) information between individuals; thus, X B = 0 denotes the special case in previous discussion. Other settings are the same as above. In this part, we will discuss the optimal blocking strategies and analyze the mechanism.

As shown in Figure 5 , the optimal blocking threshold varies from case to case. Overall, a small blocking threshold ( [ 0.1 , 0.3 ] ) is necessarily ( 100 % ) not optimal; a strict blocking threshold ( X B ≥ 0.8 ) is usually ( 50.41 % ) optimal, experimental data show a value between 45 % and 55 % in most external conditions; but 0 is the optimal threshold still in 20.25 % of cases, and usually ( 89.80 % ) occurs when ξ ≥ 0.8 and X I ≤ 0.7 . When the initial information is low ( ξ ≤ 0.6 ), not blocking is seldom ( 0.83 % ) optimal.

Simulation results for government’s trade-off in blocking. ( a ) conveys the distributions of optimal blocking threshold under 484 different external scenarios (4 pieces of initial information, 11 individual thresholds, and 11 disclosing thresholds). We show how the figure works by taking the first column as an example: there are 98 conditions in which 0 is the lowest infection rate; ( b ) conveys the relationship between initial information and blocking threshold; and ( c ) conveys the relationship between individual threshold and blocking threshold.

We have our key findings from the above analysis. First, minor blocking is not an option for government because it is dominated by stricter blocking in a deteriorated or being deteriorated information environment and undermines the efficiency of information dissemination in a benevolent environment. Second, in the age of the Internet, information is extremely interconnected and low-quality information is more easily disseminated, thus stricter information blocking might be an option worth considering in the early stages of an outbreak of an unknown infectious disease. Finally, if the virus is well-known at the medical level, plus the public has a certain level of health awareness, free spread of information might improve the situation; while, otherwise, as in the case of COVID-19, governments should intervene in the spread of information in social networks.

From the simulation results, we can see that, in most cases, the optimal strategy will be either highly stringent blocking or free spread. Blocking low-quality information not only increases the overall information of the whole population, but causes side effects under certain external conditions. Thus, not blocking can be an optimal strategy in some cases. In this section, we provide an in-depth analysis of the data and a mechanistic analysis.

Figure 5 b reveals in general the optimal blocking threshold negatively correlates with initial information: as initial information drops from 1 to 0.4 , the probability of optimal blocking threshold taking 0 will be 52.07 % , 27.27 % , 1.65 % , and 0 % , respectively. Figure 5 c shows a positive correlation between optimal blocking threshold and individual threshold.

Governments block information mainly by suppressing less-accurate information, but which, once implemented, will slow down the overall information dissemination in the network anyway. Therefore, blocking can neither be too stringent nor too liberal, an optimal one usually lies in between. However, mild blocking is necessarily not optimal as it fails to purify the information environment.

Furthermore, when the virus is well-known ( ξ = 1 ), especially when public health awareness is high ( X I ≤ 0.3 ), not blocking dominates most of the time ( 69.70 % ). While stringent blocking ( X B ≥ 0.8 ) is necessarily not ( 0 % ) an optimal strategy because higher-quality information, which helps to slow the spread of the disease with high public health awareness, is also blocked. Thus, when both the initial information and the level of public health awareness are at a high level, not blocking is optimal; otherwise, information that would not cause panic might do now. In addition, when medical awareness of the virus declines, so does the proportion of valuable information, which necessitates blocking as well.

3.4. Optimal Intervention under Different Government Types

In previous sections, our study was based on the neutral government assumption that governments only seek the lowest infection rate. However, in reality, a government is not a personalized organization pursuing social optimum because it is often checked by various inside and outside nodes. In addition, government credibility makes a difference as well. In this section, we will discuss the optimal strategy for non-neutral governments and low-credible governments.

An unaccountable government that evades responsibilities would only care for lower new infections after intervention rather than global infections, which digresses from the objective described above. As shown in Figure 6 a, the later the government discloses information, the less that will be newly infected after disclosure. There are two underlying reasons: (1) late disclosed information will indeed be more accurate, which reduces the infection rate; and (2) there are less uninfected people at the time of disclosing. Therefore, a blame-evading government would delay the disclosing to avoid being held accountable.

Simulation results for non-neutral governments and low-credible governments. ( a ) portrays the unaccountable governments based on the settings in Figure 4 a, the vertical axis is the number of newly infected people after government intervention; ( b ) the distribution of worst blocking threshold (highest infections) based on the settings of Figure 5 portrays the risk-averse government; ( c , d ) describe the low-credible governments by reassigning for government’s credibility 10 % while keeping other variables unchanged.

A conservative government that prefers the least error-prone strategy (minimizing maximum loss) rather than the optimal one (the loss minimization strategy) would block all the information ( Figure 6 b). Since the optimal strategy would not be accessed until all external conditions are fully judged and scrutinized, which is not feasible for COVID-19, complete blocking would be optimal for such a government to avoid the worst case scenario. Our experiment of 484 different scenarios manifests a complete blocking will never lead to the highest infections.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we introduce the non-dualism (by non-dualism, we mean the information is neither absolutely accurate nor absolutely not but partially accurate) of information and the heterogeneity of nodes’ behaviors into the epidemic model and conduct a simulation to reveal the information intervention dilemma faced by the government and to explore the trade-offs among corresponding strategies. Our experiments highlight that:

- For information disclosing, governments face a trade-off between speed and accuracy. A better medical understanding of the virus and an inadequate public health awareness make accuracy outweigh speed; otherwise, a quick one is better.

- For information blocking, the optimal strategy is contingent on varying conditions: no blocking is usually optimal for a well-known virus and a higher public health awareness; otherwise, blocking is preferred.

- The optimal combination of disclosing and blocking is highly sensitive to the government preference and its governance capability. A government that is only responsible for the outcome of intervention will focus unilaterally on accuracy at the expense of speed; a risk-averse government that intends to minimize the maximum infection rate in uncertain scenarios will impose a more restrictive blocking; and the most restrictive blocking strategy might be best for governments with lower capability and credibility.

These findings reveal the complexity in government decision-making about dissemination of disease information: neither allowing free flow of information nor disclosing it as early as possible is optimal. Under extreme conditions, they are even harmful to the goal of controlling disease outbreak. The interaction between information and infectious disease deepens our knowledge about public health crisis governance, enriches the existing theories in public economics and public management, and provides useful social and policy implications.

In reality, some governments are not as capable and credible as assumed. A lower credibility will discount the effects of disclosing information or even annul it, which makes a total blocking optimal as shown in Figure 6 c,d. The bankruptcy of government credibility originates in two ways: (1) the government’s past mediocre performance; (2) the public’s inherent belief in “small government”. Meanwhile, a similar experience in the past also affected government responses and effects, as we can see with the horrible painful memories of SARS inducing vigilance for COVID-19 in East Asia countries, while the U.S. and Europe were indifferent in the early stage of this pandemic.

In the preceding discussion, we relaxed one assumption at a time, whereas the government’s preferences are more complex in reality. In a broader context, the government’s preferences (objective function) are affected by two things: the government’s perception and judgment of the epidemic (decision-making base), and the government’s priorities in different objectives (decision-making objectives); both change over time.

This paper also has some limitations. For instance, our discussion focuses mainly on the theoretical mechanisms behind the joint spreading process of information and epidemic, and the proposed intervention strategies have not yet been analyzed with the real-world data. One reason for the lack of empirical analysis is the complex set-up of the bi-layered network model. The information dissemination network and the physical-layer contact network are not precisely observable in the real world, which makes it challenging for acquiring sufficient data for model fitting. On the other hand, the observed infection and information dissemination process are often already intervened in by the government; therefore, it is hard to separate the net effect of government intervention from the ex-post spreading data. Then, it is technically difficult to quantify the key parameters of intervention. To this end, we believe more sophisticated empirical techniques have to be introduced for the implement data-oriented analysis of our model, such as the network reconstruction and the causal detection techniques, which forms a promising direction for future investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Sheng Hua (Wuhan University) for helpful discussions and assistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, Y.L., Z.J., and X.Z.; analysis, Y.L., Z.J., X.Z., Y.Z., and H.L. All authors participated in manuscript writing or editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education in the China Profject of Humanities and Social Sciences, undner Grant No. 20YJC790176, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities in China, under Grant No. 2242020S30024.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4.2 Government Intervention in Market Prices: Price Floors and Price Ceilings

Learning objectives.

- Use the model of demand and supply to explain what happens when the government imposes price floors or price ceilings.

- Discuss the reasons why governments sometimes choose to control prices and the consequences of price control policies.

So far in this chapter and in the previous chapter, we have learned that markets tend to move toward their equilibrium prices and quantities. Surpluses and shortages of goods are short-lived as prices adjust to equate quantity demanded with quantity supplied.

In some markets, however, governments have been called on by groups of citizens to intervene to keep prices of certain items higher or lower than what would result from the market finding its own equilibrium price. In this section we will examine agricultural markets and apartment rental markets—two markets that have often been subject to price controls. Through these examples, we will identify the effects of controlling prices. In each case, we will look at reasons why governments have chosen to control prices in these markets and the consequences of these policies.

Agricultural Price Floors

Governments often seek to assist farmers by setting price floors in agricultural markets. A minimum allowable price set above the equilibrium price is a price floor . With a price floor, the government forbids a price below the minimum. (Notice that, if the price floor were for whatever reason set below the equilibrium price, it would be irrelevant to the determination of the price in the market since nothing would prohibit the price from rising to equilibrium.) A price floor that is set above the equilibrium price creates a surplus.

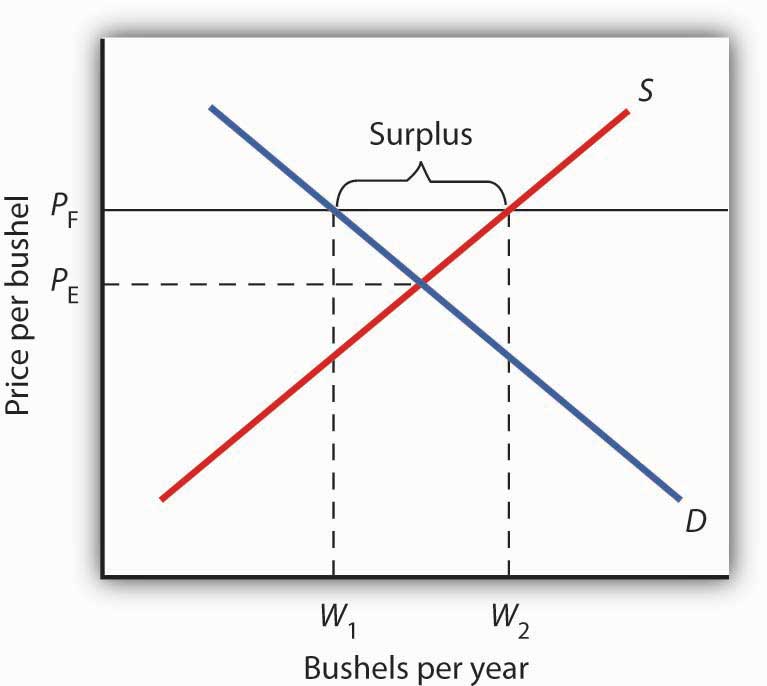

Figure 4.8 “Price Floors in Wheat Markets” shows the market for wheat. Suppose the government sets the price of wheat at P F . Notice that P F is above the equilibrium price of P E . At P F , we read over to the demand curve to find that the quantity of wheat that buyers will be willing and able to purchase is W 1 bushels. Reading over to the supply curve, we find that sellers will offer W 2 bushels of wheat at the price floor of P F . Because P F is above the equilibrium price, there is a surplus of wheat equal to ( W 2 − W 1 ) bushels. The surplus persists because the government does not allow the price to fall.

Figure 4.8 Price Floors in Wheat Markets

A price floor for wheat creates a surplus of wheat equal to ( W 2 – W 1 ) bushels.

Why have many governments around the world set price floors in agricultural markets? Farming has changed dramatically over the past two centuries. Technological improvements in the form of new equipment, fertilizers, pesticides, and new varieties of crops have led to dramatic increases in crop output per acre. Worldwide production capacity has expanded markedly. As we have learned, technological improvements cause the supply curve to shift to the right, reducing the price of food. While such price reductions have been celebrated in computer markets, farmers have successfully lobbied for government programs aimed at keeping their prices from falling.

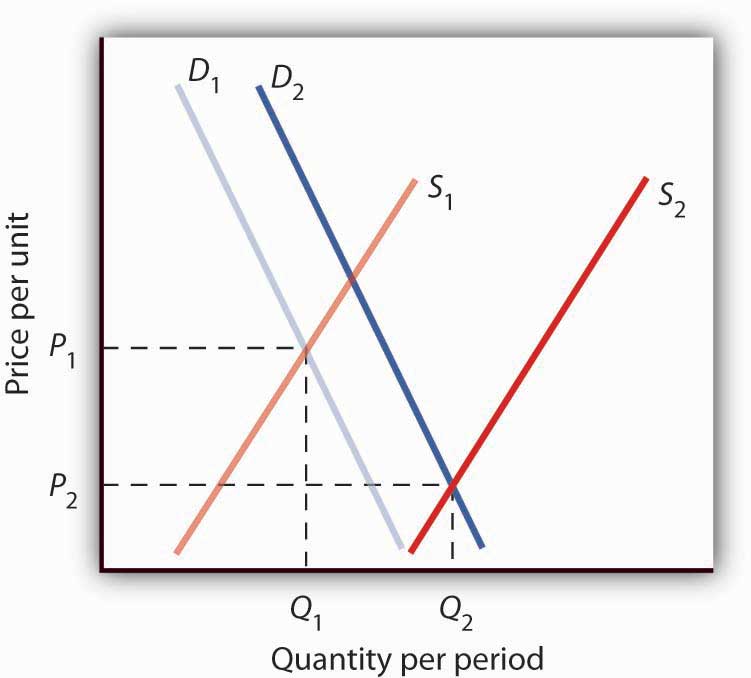

While the supply curve for agricultural goods has shifted to the right, the demand has increased with rising population and with rising income. But as incomes rise, people spend a smaller and smaller fraction of their incomes on food. While the demand for food has increased, that increase has not been nearly as great as the increase in supply. Figure 4.9 “Supply and Demand Shifts for Agricultural Products” shows that the supply curve has shifted much farther to the right, from S 1 to S 2 , than the demand curve has, from D 1 to D 2 . As a result, equilibrium quantity has risen dramatically, from Q 1 to Q 2 , and equilibrium price has fallen, from P 1 to P 2 .

On top of this long-term historical trend in agriculture, agricultural prices are subject to wide swings over shorter periods. Droughts or freezes can sharply reduce supplies of particular crops, causing sudden increases in prices. Demand for agricultural goods of one country can suddenly dry up if the government of another country imposes trade restrictions against its products, and prices can fall. Such dramatic shifts in prices and quantities make incomes of farmers unstable.

Figure 4.9 Supply and Demand Shifts for Agricultural Products

A relatively large increase in the supply of agricultural products, accompanied by a relatively small increase in demand, has reduced the price received by farmers and increased the quantity of agricultural goods.

The Great Depression of the 1930s led to a major federal role in agriculture. The Depression affected the entire economy, but it hit farmers particularly hard. Prices received by farmers plunged nearly two-thirds from 1930 to 1933. Many farmers had a tough time keeping up mortgage payments. By 1932, more than half of all farm loans were in default.

Farm legislation passed during the Great Depression has been modified many times, but the federal government has continued its direct involvement in agricultural markets. This has meant a variety of government programs that guarantee a minimum price for some types of agricultural products. These programs have been accompanied by government purchases of any surplus, by requirements to restrict acreage in order to limit those surpluses, by crop or production restrictions, and the like.

To see how such policies work, look back at Figure 4.8 “Price Floors in Wheat Markets” . At P F , W 2 bushels of wheat will be supplied. With that much wheat on the market, there is market pressure on the price of wheat to fall. To prevent price from falling, the government buys the surplus of ( W 2 – W 1 ) bushels of wheat, so that only W 1 bushels are actually available to private consumers for purchase on the market. The government can store the surpluses or find special uses for them. For example, surpluses generated in the United States have been shipped to developing countries as grants-in-aid or distributed to local school lunch programs. As a variation on this program, the government can require farmers who want to participate in the price support program to reduce acreage in order to limit the size of the surpluses.

After 1973, the government stopped buying the surpluses (with some exceptions) and simply guaranteed farmers a “target price.” If the average market price for a crop fell below the crop’s target price, the government paid the difference. If, for example, a crop had a market price of $3 per unit and a target price of $4 per unit, the government would give farmers a payment of $1 for each unit sold. Farmers would thus receive the market price of $3 plus a government payment of $1 per unit. For farmers to receive these payments, they had to agree to remove acres from production and to comply with certain conservation provisions. These restrictions sought to reduce the size of the surplus generated by the target price, which acted as a kind of price floor.

What are the effects of such farm support programs? The intention is to boost and stabilize farm incomes. But, with price floors, consumers pay more for food than they would otherwise, and governments spend heavily to finance the programs. With the target price approach, consumers pay less, but government financing of the program continues. U.S. federal spending for agriculture averaged well over $22 billion per year between 2003 and 2007, roughly $70 per person.

Help to farmers has sometimes been justified on the grounds that it boosts incomes of “small” farmers. However, since farm aid has generally been allotted on the basis of how much farms produce rather than on a per-farm basis, most federal farm support has gone to the largest farms. If the goal is to eliminate poverty among farmers, farm aid could be redesigned to supplement the incomes of small or poor farmers rather than to undermine the functioning of agricultural markets.

In 1996, the U.S. Congress passed the Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act of 1996, or FAIR. The thrust of the new legislation was to do away with the various programs of price support for most crops and hence provide incentives for farmers to respond to market price signals. To protect farmers through a transition period, the act provided for continued payments that were scheduled to decline over a seven-year period. However, with prices for many crops falling in 1998, the U.S. Congress passed an emergency aid package that increased payments to farmers. In 2008, as farm prices reached record highs, Congress passed a farm bill that increased subsidy payments to $40 billion. It did, however, for the first time limit payments to the wealthiest farmers. Individual farmers whose farm incomes exceed $750,000 (or $1.5 million for couples) would be ineligible for some subsidy programs.

Rental Price Ceilings

The purpose of rent control is to make rental units cheaper for tenants than they would otherwise be. Unlike agricultural price controls, rent control in the United States has been largely a local phenomenon, although there were national rent controls in effect during World War II. Currently, about 200 cities and counties have some type of rent control provisions, and about 10% of rental units in the United States are now subject to price controls. New York City’s rent control program, which began in 1943, is among the oldest in the country. Many other cities in the United States adopted some form of rent control in the 1970s. Rent controls have been pervasive in Europe since World War I, and many large cities in poorer countries have also adopted rent controls.

Rent controls in different cities differ in terms of their flexibility. Some cities allow rent increases for specified reasons, such as to make improvements in apartments or to allow rents to keep pace with price increases elsewhere in the economy. Often, rental housing constructed after the imposition of the rent control ordinances is exempted. Apartments that are vacated may also be decontrolled. For simplicity, the model presented here assumes that apartment rents are controlled at a price that does not change.

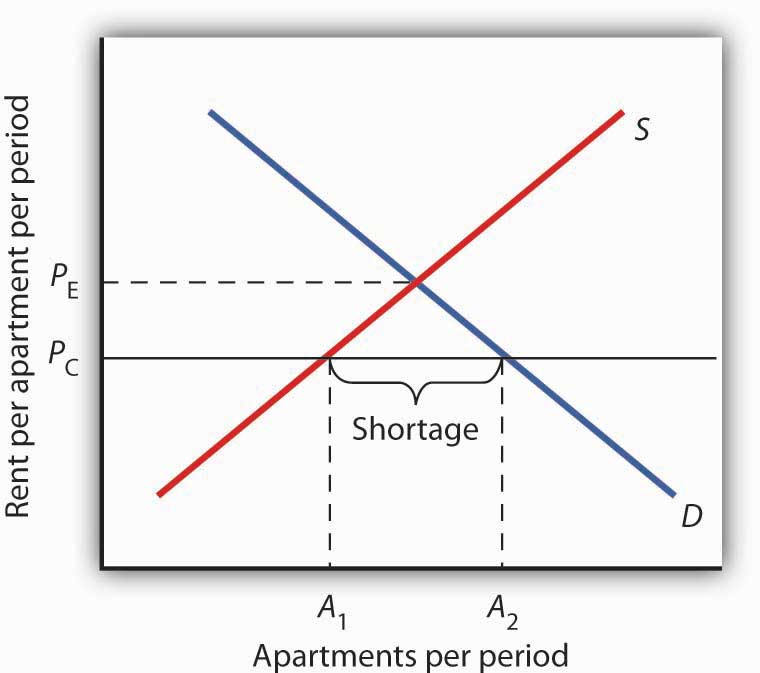

Figure 4.10 Effect of a Price Ceiling on the Market for Apartments

A price ceiling on apartment rents that is set below the equilibrium rent creates a shortage of apartments equal to ( A 2 − A 1 ) apartments.

Figure 4.10 “Effect of a Price Ceiling on the Market for Apartments” shows the market for rental apartments. Notice that the demand and supply curves are drawn to look like all the other demand and supply curves you have encountered so far in this text: the demand curve is downward-sloping and the supply curve is upward-sloping.

The demand curve shows that a higher price (rent) reduces the quantity of apartments demanded. For example, with higher rents, more young people will choose to live at home with their parents. With lower rents, more will choose to live in apartments. Higher rents may encourage more apartment sharing; lower rents would induce more people to live alone.

The supply curve is drawn to show that as rent increases, property owners will be encouraged to offer more apartments to rent. Even though an aerial photograph of a city would show apartments to be fixed at a point in time, owners of those properties will decide how many to rent depending on the amount of rent they anticipate. Higher rents may also induce some homeowners to rent out apartment space. In addition, renting out apartments implies a certain level of service to renters, so that low rents may lead some property owners to keep some apartments vacant.

Rent control is an example of a price ceiling , a maximum allowable price. With a price ceiling, the government forbids a price above the maximum. A price ceiling that is set below the equilibrium price creates a shortage that will persist.

Suppose the government sets the price of an apartment at P C in Figure 4.10 “Effect of a Price Ceiling on the Market for Apartments” . Notice that P C is below the equilibrium price of P E . At P C , we read over to the supply curve to find that sellers are willing to offer A 1 apartments. Reading over to the demand curve, we find that consumers would like to rent A 2 apartments at the price ceiling of P C . Because P C is below the equilibrium price, there is a shortage of apartments equal to ( A 2 – A 1 ). (Notice that if the price ceiling were set above the equilibrium price it would have no effect on the market since the law would not prohibit the price from settling at an equilibrium price that is lower than the price ceiling.)

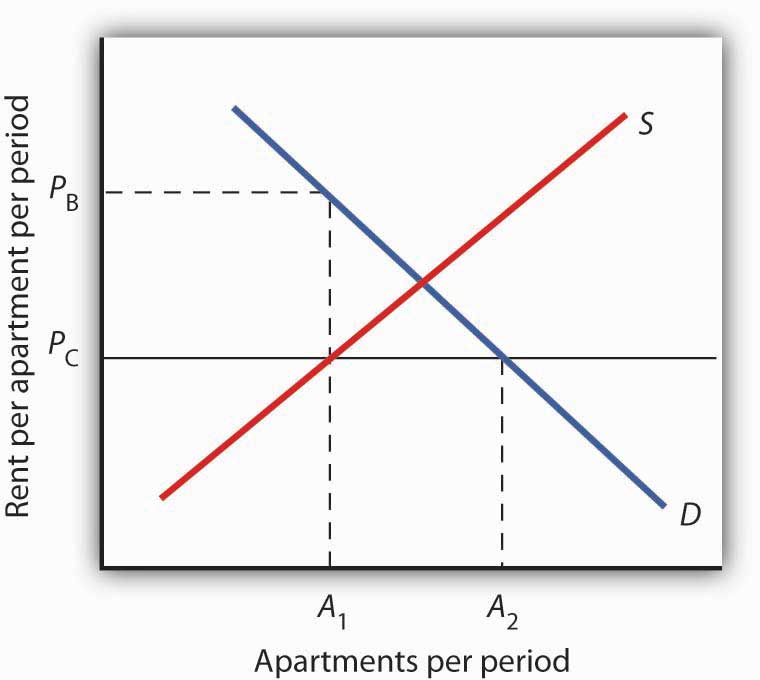

Figure 4.11 The Unintended Consequences of Rent Control

Controlling apartment rents at P C creates a shortage of ( A 2 − A 1 ) apartments. For A 1 apartments, consumers are willing and able to pay P B , which leads to various “backdoor” payments to apartment owners.

If rent control creates a shortage of apartments, why do some citizens nonetheless clamor for rent control and why do governments often give in to the demands? The reason generally given for rent control is to keep apartments affordable for low- and middle-income tenants.

But the reduced quantity of apartments supplied must be rationed in some way, since, at the price ceiling, the quantity demanded would exceed the quantity supplied. Current occupants may be reluctant to leave their dwellings because finding other apartments will be difficult. As apartments do become available, there will be a line of potential renters waiting to fill them, any of whom is willing to pay the controlled price of P C or more. In fact, reading up to the demand curve in Figure 4.11 “The Unintended Consequences of Rent Control” from A 1 apartments, the quantity available at P C , you can see that for A 1 apartments, there are potential renters willing and able to pay P B . This often leads to various “backdoor” payments to apartment owners, such as large security deposits, payments for things renters may not want (such as furniture), so-called “key” payments (“The monthly rent is $500 and the key price is $3,000”), or simple bribes.

In the end, rent controls and other price ceilings often end up hurting some of the people they are intended to help. Many people will have trouble finding apartments to rent. Ironically, some of those who do find apartments may actually end up paying more than they would have paid in the absence of rent control. And many of the people that the rent controls do help (primarily current occupants, regardless of their income, and those lucky enough to find apartments) are not those they are intended to help (the poor). There are also costs in government administration and enforcement.

Because New York City has the longest history of rent controls of any city in the United States, its program has been widely studied. There is general agreement that the rent control program has reduced tenant mobility, led to a substantial gap between rents on controlled and uncontrolled units, and favored long-term residents at the expense of newcomers to the city (Arnott, R., 1995). These distortions have grown over time, another frequent consequence of price controls.

A more direct means of helping poor tenants, one that would avoid interfering with the functioning of the market, would be to subsidize their incomes. As with price floors, interfering with the market mechanism may solve one problem, but it creates many others at the same time.

Key Takeaways

- Price floors create surpluses by fixing the price above the equilibrium price. At the price set by the floor, the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded.

- In agriculture, price floors have created persistent surpluses of a wide range of agricultural commodities. Governments typically purchase the amount of the surplus or impose production restrictions in an attempt to reduce the surplus.

- Price ceilings create shortages by setting the price below the equilibrium. At the ceiling price, the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied.

- Rent controls are an example of a price ceiling, and thus they create shortages of rental housing.

- It is sometimes the case that rent controls create “backdoor” arrangements, ranging from requirements that tenants rent items that they do not want to outright bribes, that result in rents higher than would exist in the absence of the ceiling.

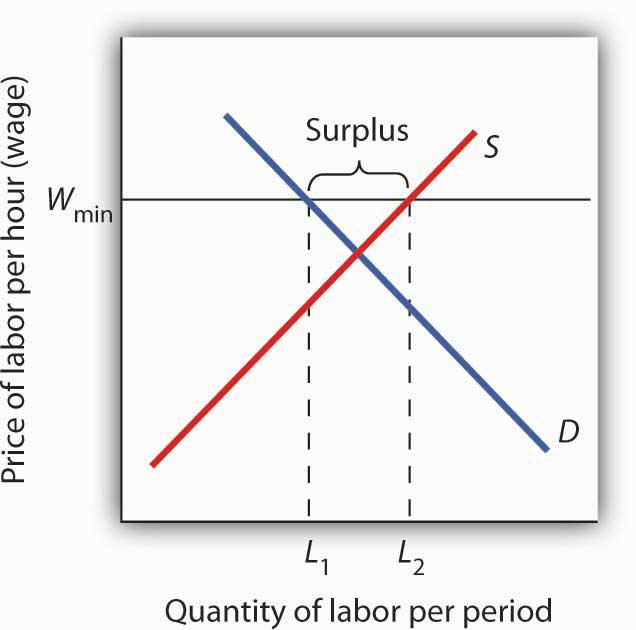

A minimum wage law is another example of a price floor. Draw demand and supply curves for unskilled labor. The horizontal axis will show the quantity of unskilled labor per period and the vertical axis will show the hourly wage rate for unskilled workers, which is the price of unskilled labor. Show and explain the effect of a minimum wage that is above the equilibrium wage.

Case in Point: Corn: It Is Not Just Food Any More

Figure 4.12

Herry Lawford – Stocks – CC BY 2.0.

Government support for corn dates back to the Agricultural Act of 1938 and, in one form or another, has been part of agricultural legislation ever since. Types of supports have ranged from government purchases of surpluses to target pricing, land set asides, and loan guarantees. According to one estimate, the U.S. government spent nearly $42 billion to support corn between 1995 and 2004.

Then, during the period of rising oil prices of the late 1970s and mounting concerns about dependence on foreign oil from volatile regions in the world, support for corn, not as a food, but rather as an input into the production of ethanol—an alternative to oil-based fuel—began. Ethanol tax credits were part of the Energy Act of 1978. Since 1980, a tariff of 50¢ per gallon against imported ethanol, even higher today, has served to protect domestic corn-based ethanol from imported ethanol, in particular from sugar-cane-based ethanol from Brazil.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 was another milestone in ethanol legislation. Through loan guarantees, support for research and development, and tax credits, it mandated that 4 billion gallons of ethanol be used by 2006 and 7.5 billion gallons by 2012. Ethanol production had already reached 6.5 billion gallons by 2007, so new legislation in 2007 upped the ante to 15 billion gallons by 2015.

Beyond the increased amount the government is spending to support corn and corn-based ethanol, criticism of the policy has three major prongs:

- Corn-based ethanol does little to reduce U.S. dependence on foreign oil because the energy required to produce a gallon of corn-based ethanol is quite high. A 2006 National Academy of Sciences paper estimated that one gallon of ethanol is needed to bring 1.25 gallons of it to market. Other studies show an even less favorable ratio.

- Biofuels, such as corn-based ethanol, are having detrimental effects on the environment, with increased deforestation, stemming from more land being used to grow fuel inputs, contributing to global warming.

- The diversion of corn and other crops from food to fuel is contributing to rising food prices and an increase in world hunger. C. Ford Runge and Benjamin Senauer wrote in Foreign Affairs that even small increases in prices of food staples have severe consequences on the very poor of the world, and “Filling the 25-gallon tank of an SUV with pure ethanol requires over 450 pounds of corn—which contains enough calories to feed one person for a year.”

Some of these criticisms may be contested as exaggerated: Will the ratio of energy-in to energy-out improve as new technologies emerge for producing ethanol? Did not other factors, such as weather and rising food demand worldwide, contribute to higher grain prices? Nonetheless, it is clear that corn-based ethanol is no free lunch. It is also clear that the end of government support for corn is nowhere to be seen.

Sources: Alexei Barrionuevo, “Mountains of Corn and a Sea of Farm Subsidies,” New York Times , November 9, 2005, online version; David Freddoso, “Children of the Corn,” National Review Online, May 6, 2008; C. Ford Runge and Benjamin Senauer, “How Biofuels Could Starve the Poor,” Foreign Affairs , May/June 2007, online version; Michael Grunwald, “The Clean Energy Scam,” Time 171:14 (April 7, 2008): 40–45.

Answer to Try It! Problem

A minimum wage ( W min ) that is set above the equilibrium wage would create a surplus of unskilled labor equal to ( L 2 – L 1 ). That is, L 2 units of unskilled labor are offered at the minimum wage, but companies only want to use L 1 units at that wage. Because unskilled workers are a substitute for a skilled workers, forcing the price of unskilled workers higher would increase the demand for skilled labor and thus increase their wages.

Figure 4.13

Arnott, R., “Time for Revisionism on Rent Control,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 9(1) (Winter, 1995): 99–120.

Principles of Economics Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Downloadable Content

Government Intervention and Free Markets: Case Studies in Voter Opinion

- Student Research

- Rhodes, Robert T.

- Guerrero, Mario

- Letters, Arts, & Social Sciences

- Political Science

- California State Polytechnic University, Pomona

- political science

- free market

- 2015-04-21T18:18:21Z

- http://hdl.handle.net/10211.3/138063

- All rights reserved.

Relationships

- 2015 SRC Oral Presentation Sessions

- Dr. Mario Guerrero

Items in ScholarWorks are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated.

In: Economics

Case Study 1: Government Intervention In Germany in 2009 there was considerable debate about the extent...

- Case Study 1: Government Intervention

In Germany in 2009 there was considerable debate about the extent to which the government should be intervening in the economy. For example, its citizens were worried about the future of Opel, a German car brand that was part of the ailing General Motors. Some wanted the government to make sure jobs were saved no matter what. Others, however, were more hesitant and worried about becoming the government becoming too interventionist. Traditionally since the Second World War the German government has seen itself as a referee in market issues and has avoided trying to control parts of the economy. It would regulate anti-competitive behavior, for example, but not try to run many industries. However, in the recession of 2009 when the economy was shrinking the government was forced to spend more to stimulate demand and had to intervene heavily to save the banking sector from collapse. The government also had to offer aid to businesses to keep them alive.

1. What are the possible benefits of a government intervening in an economy?

3. What prompted greater intervention by the German government in 2009?

4. What would determine whether the German continued to intervene on this scale in

the future?

Expert Solution

1. Governments can intervene to provide a basic security net – unemployment benefit, minimum income for those who are sick and disabled. This increases net economic welfare and enables individuals to escape the worst poverty. This government intervention can also prevent social unrest from extremes of inequality. There are many advantages of government intervention such as even income distribution, no social injustice, secured public goods and services, property rights and welfare opportunities for those who cannot afford.

3. Germany was shaken by the financial crisis that began in mid-September 2008 on two levels: First, its banks were hit by the spreading financial panic, forcing the government to intervene in the overleveraged banking sector; second, its exports were hit by falling worldwide demand as credit dried up.

4. The value of currency and the economic power of Germany will determine such an intervention in future.

Related Solutions

Case-1 in 1920, there was considerable debate regarding how much the us government should intervene in..., from this case study "the 2007-2009 financial crisis" , whats the role of derivative securities, government,..., in the intervention section of your case study, you need to describe what the intervention is..., discuss the extent to which market failure provides sufficient justification for government intervention into your country's..., to what extent the government response in each of the three countries usa, uk, and germany was effective in containing and solving the crisis, what is so special about healthcare that justifies government intervention, to what extent should government be concerned about the prospects of deflation, 1. a study conducted in march 2009 found that about half of u.s. adults trusted the..., case study: after a considerable investment of both money and time, executives at leman healthcare were..., case study - warehouse case study - warehouse the following case about otter aerospace is a....

- Advanced Math

- Anatomy and Physiology

- Civil Engineering

- Computer Science

- Electrical Engineering

- Mechanical Engineering

- Operations Management

- Statistics and Probability

- In April 2020, the U.S. national debts has exceeded $23.8 Trillion. It is rising much faster...

- what al ghazali thinks about virtue?

- 1. what intersectionality is and why it might be important to psychologists 2. what is the difference...

- Use the Black-Scholes model to find the value for a European put option that has an...

- Using C++ Write a program that reads a text from the keyboard until the user presses...

- Some economists claim that inflation is always a “monetary phenomenon.” What do they mean by this...

- How do you think recessions influence elections?

Lead in the Americas: A Call for Action (1996)

Chapter: session d: case studies of interventions, case studies of interventions, introduction: case studies of interventions.

D AVID R ALL *

The task of reducing lead exposures and preventing lead poisoning across the Americas seems a daunting task. This session highlights four case studies of interventions in different sectors. The first describes a successful voluntary industry initiative in Mexico to remove lead solder from the canning process. The second presents an example of government regulation—in this instance, the U.S. Clean Air Act—that dramatically reduced population lead levels in the United States. The third case study explores the role of international organized labor—in this case the U.S. Carpenter's Union—in educating and training workers about lead poisoning and describes the union's efforts to work with government agencies to ensure stricter protective policies for workers and their families. The final case study describes the role of community activism and education in empowering local communities in Mexico to design and implement focused public health programs to reduce lead exposure in their populations.

What these four case studies illustrate is that successful control and prevention strategies require the involvement of people and organizations at all levels of society, from the federal sector down to the grassroots or community. Lead poisoning is a problem that directly affects people at all levels of society. Its solutions must, therefore, also be shared.

A LFONSO DE L EÓN *

In 1992, the metallic containers industry in Mexico stopped producing tin cans with lead soldering as food containers, substituting instead a process that closes tin cans with electrical solder. Mexican public health authorities are now interested in determining whether a quantifiable reduction in population blood lead levels, especially in children, has occurred as a result of this voluntary industry change.

The National Chamber for Metallic Containers of Mexico represents more than 85 percent of steel tin can and 100 percent of aluminum tin can production, making it the leading manufacturer of metallic containers in Mexico. The process leading to the total elimination of lead soldering in food cans was begun as a voluntary initiative by industry, although the increased pace of change in the latter phases of conversion was dictated by external events. This process is described briefly below.

Metallic containers have been used to hold and conserve food for more than 180 years. In the beginning, tin was used in soldering, but it resulted in little flexibility and a fragile seam. Lead rapidly replaced tin in solder because it is a ductile material that easily adheres to the tin plate and can be mixed with the tin to produce a more flexible and less fragile soldering. At one point the solder commonly used contained 90 percent lead and 10 percent tin. Such soldering was universally adopted and, with it, many billions of cans were produced globally, without an understanding that lead in external soldering posed a public health hazard.

When medical and public health authorities began to acknowledge concerns about the effects of lead exposure on human health, attempts were made to identify the different sources of the metal. Leaded gasoline, paints, and ceramicware glazes and food cans containing leaded solder were rapidly identified as important sources.

Manufacturers of metallic containers had already began, by the late 1970s, to substitute lead soldering with electric soldering. This change was instituted for reasons apart from public health concerns about lead, which remained largely unknown at the time. The main motives for converting to electrical soldering were to have a cleaner production process, greater productivity, and a larger surface area on the cans for the purposes of advertising (leaded seams are broader than electrically soldered seams). Mexico adopted the electrical soldering technique, despite the many lead soldering production lines that still had many years of usable life and the $1.2-2.0 million investment that was required to refit production lines. This change was an unusual one for Mexico, which does not usually afford itself the luxury of getting rid of production equipment that is still considered useful.

At the beginning of 1991, a strong popular movement against lead in the environment was organized in Mexico City. The metallic container industries became involved in this movement, along with other lead industries. As an outcome, ecologists, united with health authorities, insisted that the electrical soldering substitution process that had been under way for over 10 years be abruptly accelerated. We cannot deny that moments in the ensuing deliberations were amusing.

The industry's basic argument in 1991 against an abrupt acceleration in the substitution process was based on the following: (1) in 1979 the industry voluntarily initiated a gradual substitution of production lines that utilized lead solder; (2) the cost for substituting each line was too high to warrant wholesale, rapid substitution; (3) until research proved that inward migration of lead from the external soldering of tin cans was contributing to the amount of lead in canned foods, accelerated action was premature; and (4) the recommended threshold for lead in foods was still subject to debate.

To support industry's argument, we noted U.S. FDA reports that indicated similar voluntary changes occurring at the same pace in the U.S. metallic container industry. According to these reports, in the early 1980s, 90 percent of tin cans produced in the United States had leaded solder; by the 1990s, the proportion had dropped to approximately 4 percent and was expected to decrease even more in the coming years. Clearly, industry in two major markets was voluntarily making changes, and the demand that the Mexican sector suddenly accelerate its rate of conversion—at considerable additional cost—was unfair.

The FDA , to my knowledge, has not yet been able to establish legislation totally prohibiting the use of lead soldering in tin cans for food. In 1994, for