- Open access

- Published: 13 November 2019

Evidence-based models of care for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in primary health care settings: protocol for systematic review

- Susan A. Rombouts 1 ,

- James Conigrave 2 ,

- Eva Louie 1 ,

- Paul Haber 1 , 3 &

- Kirsten C. Morley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0868-9928 1

Systematic Reviews volume 8 , Article number: 275 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

7008 Accesses

3 Citations

Metrics details

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is highly prevalent and accounts globally for 1.6% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) among females and 6.0% of DALYs among males. Effective treatments for AUDs are available but are not commonly practiced in primary health care. Furthermore, referral to specialized care is often not successful and patients that do seek treatment are likely to have developed more severe dependence. A more cost-efficient health care model is to treat less severe AUD in a primary care setting before the onset of greater dependence severity. Few models of care for the management of AUD in primary health care have been developed and with limited implementation. This proposed systematic review will synthesize and evaluate differential models of care for the management of AUD in primary health care settings.

We will conduct a systematic review to synthesize studies that evaluate the effectiveness of models of care in the treatment of AUD in primary health care. A comprehensive search approach will be conducted using the following databases; MEDLINE (1946 to present), PsycINFO (1806 to present), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (1991 to present), and Embase (1947 to present).

Reference searches of relevant reviews and articles will be conducted. Similarly, a gray literature search will be done with the help of Google and the gray matter tool which is a checklist of health-related sites organized by topic. Two researchers will independently review all titles and abstracts followed by full-text review for inclusion. The planned method of extracting data from articles and the critical appraisal will also be done in duplicate. For the critical appraisal, the Cochrane risk of bias tool 2.0 will be used.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to guide improvement of design and implementation of evidence-based models of care for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in primary health care settings. The evidence will define which models are most promising and will guide further research.

Protocol registration number

PROSPERO CRD42019120293.

Peer Review reports

It is well recognized that alcohol use disorders (AUD) have a damaging impact on the health of the population. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 5.3% of all global deaths were attributable to alcohol consumption in 2016 [ 1 ]. The 2016 Global Burden of Disease Study reported that alcohol use led to 1.6% (95% uncertainty interval [UI] 1.4–2.0) of total DALYs globally among females and 6.0% (5.4–6.7) among males, resulting in alcohol use being the seventh leading risk factor for both premature death and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [ 2 ]. Among people aged 15–49 years, alcohol use was the leading risk factor for mortality and disability with 8.9% (95% UI 7.8–9.9) of all attributable DALYs for men and 2.3% (2.0–2.6) for women [ 2 ]. AUD has been linked to many physical and mental health complications, such as coronary heart disease, liver cirrhosis, a variety of cancers, depression, anxiety, and dementia [ 2 , 3 ]. Despite the high morbidity and mortality rate associated with hazardous alcohol use, the global prevalence of alcohol use disorders among persons aged above 15 years in 2016 was stated to be 5.1% (2.5% considered as harmful use and 2.6% as severe AUD), with the highest prevalence in the European and American region (8.8% and 8.2%, respectively) [ 1 ].

Effective and safe treatment for AUD is available through psychosocial and/or pharmacological interventions yet is not often received and is not commonly practiced in primary health care. While a recent European study reported 8.7% prevalence of alcohol dependence in primary health care populations [ 4 ], the vast majority of patients do not receive the professional treatment needed, with only 1 in 5 patients with alcohol dependence receiving any formal treatment [ 4 ]. In Australia, it is estimated that only 3% of individuals with AUD receive approved pharmacotherapy for the disorder [ 5 , 6 ]. Recognition of AUD in general practice uncommonly leads to treatment before severe medical and social disintegration [ 7 ]. Referral to specialized care is often not successful, and those patients that do seek treatment are likely to have more severe dependence with higher levels of alcohol use and concurrent mental and physical comorbidity [ 4 ].

Identifying and treating early stage AUDs in primary care settings can prevent condition worsening. This may reduce the need for more complex and more expensive specialized care. The high prevalence of AUD in primary health care and the chronic relapsing character of AUD make primary care a suitable and important location for implementing evidence-based interventions. Successful implementation of treatment models requires overcoming multiple barriers. Qualitative studies have identified several of those barriers such as limited time, limited organizational capacity, fear of losing patients, and physicians feeling incompetent in treating AUD [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Additionally, a recent systematic review revealed that diagnostic sensitivity of primary care physicians in the identification of AUD was 41.7% and that only in 27.3% alcohol problems were recorded correctly in primary care records [ 11 ].

Several models for primary care have been created to increase identification and treatment of patients with AUD. Of those, the model, screening, brief interventions, and referral to specialized treatment for people with severe AUD (SBIRT [ 12 ]) is most well-known. Multiple systematic reviews exist, confirming its effectiveness [ 13 , 14 , 15 ], although implementation in primary care has been inadequate. Moreover, most studies have looked primarily at SBIRT for the treatment of less severe AUD [ 16 ]. In the treatment of severe AUD, efficacy of SBIRT is limited [ 16 ]. Additionally, many patient referred to specialized care often do not attend as they encounter numerous difficulties in health care systems including stigmatization, costs, lack of information about existing treatments, and lack of non-abstinence-treatment goals [ 7 ]. An effective model of care for improved management of AUD that can be efficiently implemented in primary care settings is required.

Review objective

This proposed systematic review will synthesize and evaluate differential models of care for the management of AUD in primary health care settings. We aim to evaluate the effectiveness of the models of care in increasing engagement and reducing alcohol consumption.

By providing this overview, we aim to guide improvement of design and implementation of evidence-based models of care for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in primary health care settings.

The systematic review is registered in PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42019120293) and the current protocol has been written according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) recommended for systematic reviews [ 17 ]. A PRISMA-P checklist is included as Additional file 1 .

Eligibility criteria

Criteria for considering studies for this review are classified by the following:

Study design

Both individualized and cluster randomized trials will be included. Masking of patients and/or physicians is not an inclusion criterion as it is often hard to accomplish in these types of studies.

Patients in primary health care who are identified (using screening tools or by primary health care physician) as suffering from AUD (from mild to severe) or hazardous alcohol drinking habits (e.g., comorbidity, concurrent medication use). Eligible patients need to have had formal assessment of AUD with diagnostic tools such as Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV/V) or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) and/or formal assessment of hazardous alcohol use assessed by the Comorbidity Alcohol Risk Evaluation Tool (CARET) or the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification test (AUDIT) and/or alcohol use exceeding guideline recommendations to reduce health risks (e.g., US dietary guideline (2015–2020) specifies excessive drinking for women as ≥ 4 standard drinks (SD) on any day and/or ≥ 8 SD per week and for men ≥ 5 SD on any day and/or ≥ 15 SD per week).

Studies evaluating models of care for additional diseases (e.g., other dependencies/mental health) other than AUD are included when they have conducted data analysis on the alcohol use disorder patient data separately or when 80% or more of the included patients have AUD.

Intervention

The intervention should consist of a model of care; therefore, it should include multiple components and cover different stages of the care pathway (e.g., identification of patients, training of staff, modifying access to resources, and treatment). An example is the Chronic Care Model (CCM) which is a primary health care model designed for chronic (relapsing) conditions and involves six elements: linkage to community resources, redesign of health care organization, self-management support, delivery system redesign (e.g., use of non-physician personnel), decision support, and the use of clinical information systems [ 18 , 19 ].

As numerous articles have already assessed the treatment model SBIRT, this model of care will be excluded from our review unless the particular model adds a specific new aspect. Also, the article has to assess the effectiveness of the model rather than assessing the effectiveness of the particular treatment used. Because identification of patients is vital to including them in the trial, a care model that only evaluates either patient identification or treatment without including both will be excluded from this review.

Model effectiveness may be in comparison with the usual care or a different treatment model.

Included studies need to include at least one of the following outcome measures: alcohol consumption, treatment engagement, uptake of pharmacological agents, and/or quality of life.

Solely quantitative research will be included in this systematic review (e.g., randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster RCTs). We will only include peer-reviewed articles.

Restrictions (language/time period)

Studies published in English after 1 January 1998 will be included in this systematic review.

Studies have to be conducted in primary health care settings as such treatment facilities need to be physically in or attached to the primary care clinic. Examples are co-located clinics, veteran health primary care clinic, hospital-based primary care clinic, and community primary health clinics. Specialized primary health care clinics such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) clinics are excluded from this systematic review. All studies were included, irrespective of country of origin.

Search strategy and information sources

A comprehensive search will be conducted. The following databases will be consulted: MEDLINE (1946 to present), PsycINFO (1806 to present), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (1991 to present), and Embase (1947 to present). Initially, the search terms will be kept broad including alcohol use disorder (+synonyms), primary health care, and treatment to minimize the risk of missing any potentially relevant articles. Depending on the number of references attained by this preliminary search, we will add search terms referring to models such as models of care, integrated models, and stepped-care models, to limit the number of articles. Additionally, we will conduct reference searches of relevant reviews and articles. Similarly, a gray literature search will be done with the help of Google and the Gray Matters tool which is a checklist of health-related sites organized by topic. The tool is produced by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) [ 20 ].

See Additional file 2 for a draft of our search strategy in MEDLINE.

Data collection

The selection of relevant articles is based on several consecutive steps. All references will be managed using EndNote (EndNote version X9 Clarivate Analytics). Initially, duplicates will be removed from the database after which all the titles will be screened with the purpose of discarding clearly irrelevant articles. The remaining records will be included in an abstract and full-text screen. All steps will be done independently by two researchers. Disagreement will lead to consultation of a third researcher.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two researchers will extract data from included records. At the conclusion of data extraction, these two researchers will meet with the lead author to resolve any discrepancies.

In order to follow a structured approach, an extraction form will be used. Key elements of the extraction form are information about design of the study (randomized, blinded, control), type of participants (alcohol use, screening tool used, socio-economic status, severity of alcohol use, age, sex, number of participants), study setting (primary health care setting, VA centers, co-located), type of intervention/model of care (separate elements of the models), type of health care worker (primary, secondary (co-located)), duration of follow-up, outcome measures used in the study, and funding sources. We do not anticipate having sufficient studies for a meta-analysis. As such, we plan to perform a narrative synthesis. We will synthesize the findings from the included articles by cohort characteristics, differential aspects of the intervention, controls, and type of outcome measures.

Sensitivity analyses will be conducted when issues suitable for sensitivity analysis are identified during the review process (e.g., major differences in quality of the included articles).

Potential meta-analysis

In the event that sufficient numbers of effect sizes can be extracted, a meta-analytic synthesis will be performed. We will extract effect sizes from each study accordingly. Two effect sizes will be extracted (and transformed where appropriate). Categorical outcomes will be given in log odds ratios and continuous measures will be converted into standardized mean differences. Variation in effect sizes attributable to real differences (heterogeneity) will be estimated using the inconsistency index ( I 2 ) [ 21 , 22 ]. We anticipate high degrees of variation among effect sizes, as a result moderation and subgroup-analyses will be employed as appropriate. In particular, moderation analysis will focus on the degree of heterogeneity attributable to differences in cohort population (pre-intervention drinking severity, age, etc.), type of model/intervention, and study quality. We anticipate that each model of care will require a sub-group analysis, in which case a separate meta-analysis will be performed for each type of model. Small study effect will be assessed with funnel plots and Egger’s symmetry tests [ 23 ]. When we cannot obtain enough effect sizes for synthesis or when the included studies are too diverse, we will aim to illustrate patterns in the data by graphical display (e.g., bubble plot) [ 24 ].

Critical appraisal of studies

All studies will be critically assessed by two researchers independently using the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (RoB 2) [ 25 ]. This tool facilitates systematic assessment of the quality of the article per outcome according to the five domains: bias due to (1) the randomization process, (2) deviations from intended interventions, (3) missing outcome data, (4) measurement of the outcome, and (5) selection of the reported results. An additional domain 1b must be used when assessing the randomization process for cluster-randomized studies.

Meta-biases such as outcome reporting bias will be evaluated by determining whether the protocol was published before recruitment of patients. Additionally, trial registries will be checked to determine whether the reported outcome measures and statistical methods are similar to the ones described in the registry. The gray literature search will be of assistance when checking for publication bias; however, completely eliminating the presence of publication bias is impossible.

Similar to article selection, any disagreement between the researchers will lead to discussion and consultation of a third researcher. The strength of the evidence will be graded according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [ 26 ].

The primary outcome measure of this proposed systematic review is the consumption of alcohol at follow-up. Consumption of alcohol is often quantified in drinking quantity (e.g., number of drinks per week), drinking frequency (e.g., percentage of days abstinent), binge frequency (e.g., number of heavy drinking days), and drinking intensity (e.g., number of drinks per drinking day). Additionally, outcomes such as percentage/proportion included patients that are abstinent or considered heavy/risky drinkers at follow-up. We aim to report all these outcomes. The consumption of alcohol is often self-reported by patients. When studies report outcomes at multiple time points, we will consider the longest follow-up of individual studies as a primary outcome measure.

Depending on the included studies, we will also consider secondary outcome measures such as treatment engagement (e.g., number of visits or pharmacotherapy uptake), economic outcome measures, health care utilization, quality of life assessment (physical/mental), alcohol-related problems/harm, and mental health score for depression or anxiety.

This proposed systematic review will synthesize and evaluate differential models of care for the management of AUD in primary health care settings.

Given the complexities of researching models of care in primary care and the paucity of a focus on AUD treatment, there are likely to be only a few studies that sufficiently address the research question. Therefore, we will do a preliminary search without the search terms for model of care. Additionally, the search for online non-academic studies presents a challenge. However, the Gray Matters tool will be of guidance and will limit the possibility of missing useful studies. Further, due to diversity of treatment models, outcome measures, and limitations in research design, it is possible that a meta-analysis for comparative effectiveness may not be appropriate. Moreover, in the absence of large, cluster randomized controlled trials, it will be difficult to distinguish between the effectiveness of the treatment given and that of the model of care and/or implementation procedure. Nonetheless, we will synthesize the literature and provide a critical evaluation of the quality of the evidence.

This review will assist the design and implementation of models of care for the management of AUD in primary care settings. This review will thus improve the management of AUD in primary health care and potentially increase the uptake of evidence-based interventions for AUD.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Alcohol use disorder

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification test

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health

The Comorbidity Alcohol Risk Evaluation

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Human immunodeficiency virus

10 - International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols

Screening, brief intervention, referral to specialized treatment

Standard drinks

World Health Organization

WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health: World health organization; 2018.

The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016. a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(12):987–1012.

Article Google Scholar

WHO. Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol: World health organization; 2010.

Rehm J, Allamani A, Elekes Z, Jakubczyk A, Manthey J, Probst C, et al. Alcohol dependence and treatment utilization in Europe - a representative cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:90.

Morley KC, Logge W, Pearson SA, Baillie A, Haber PS. National trends in alcohol pharmacotherapy: findings from an Australian claims database. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;166:254–7.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Morley KC, Logge W, Pearson SA, Baillie A, Haber PS. Socioeconomic and geographic disparities in access to pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence. J Subst Abus Treat. 2017;74:23–5.

Rehm J, Anderson P, Manthey J, Shield KD, Struzzo P, Wojnar M, et al. Alcohol use disorders in primary health care: what do we know and where do we go? Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51(4):422–7.

Le KB, Johnson JA, Seale JP, Woodall H, Clark DC, Parish DC, et al. Primary care residents lack comfort and experience with alcohol screening and brief intervention: a multi-site survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):790–6.

McLellan AT, Starrels JL, Tai B, Gordon AJ, Brown R, Ghitza U, et al. Can substance use disorders be managed using the chronic care model? review and recommendations from a NIDA consensus group. Public Health Rev. 2014;35(2).

Storholm ED, Ober AJ, Hunter SB, Becker KM, Iyiewuare PO, Pham C, et al. Barriers to integrating the continuum of care for opioid and alcohol use disorders in primary care: a qualitative longitudinal study. J Subst Abus Treat. 2017;83:45–54.

Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Bird V, Rizzo M. Clinical recognition and recording of alcohol disorders by clinicians in primary and secondary care: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:93–100.

Babor TF, Ritson EB, Hodgson RJ. Alcohol-related problems in the primary health care setting: a review of early intervention strategies. Br J Addict. 1986;81(1):23–46.

Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, Pienaar E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):Cd004148.

O'Donnell A, Anderson P, Newbury-Birch D, Schulte B, Schmidt C, Reimer J, et al. The impact of brief alcohol interventions in primary healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(1):66–78.

Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Wietlisbach V, Fleming M, Burnand B. Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(9):986–95.

Saitz R. ‘SBIRT’ is the answer? Probably not. Addiction. 2015;110(9):1416–7.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Bmj. 2015;350:g7647.

Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. Jama. 2002;288(14):1775–9.

Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. Jama. 2002;288(15):1909–14.

CADTH. Grey Matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature Internet. 2018 (cited 2019 Feb 22).

Higgins JPT. Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Google Scholar

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ. Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Higgins JPT, López-López JA, Becker BJ, Davies SR, Dawson S, Grimshaw JM, et al. Synthesising quantitative evidence in systematic reviews of complex health interventions. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(Suppl 1):e000858–e.

Higgins, J.P.T., Sterne, J.A.C., Savović, J., Page, M.J., Hróbjartsson, A., Boutron, I., Reeves, B., Eldridge, S. (2016). A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. In: Chandler, J., McKenzie, J., Boutron, I., Welch, V. (editors). Cochrane methods. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 10 (Suppl 1). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD201601 .

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, editor(s). Handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using the GRADE approach (updated October 2013). GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/app/handbook/handbook.html ).

Download references

Acknowledgements

There is no dedicated funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Discipline of Addiction Medicine, Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Susan A. Rombouts, Eva Louie, Paul Haber & Kirsten C. Morley

NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Indigenous Health and Alcohol, Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

James Conigrave

Drug Health Services, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Camperdown, NSW, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

KM and PH conceived the presented idea of a systematic review and meta-analysis and helped with the scope of the literature. KM is the senior researcher providing overall guidance and the guarantor of this review. SR developed the background, search strategy, and data extraction form. SR and EL will both be working on the data extraction and risk of bias assessment. SR and JC will conduct the data analysis and synthesize the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kirsten C. Morley .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1..

PRISMA-P 2015 Checklist.

Additional file 2.

Draft search strategy MEDLINE. Search strategy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Rombouts, S.A., Conigrave, J., Louie, E. et al. Evidence-based models of care for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in primary health care settings: protocol for systematic review. Syst Rev 8 , 275 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1157-7

Download citation

Received : 25 March 2019

Accepted : 13 September 2019

Published : 13 November 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1157-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Model of care

- Primary health care

- Systematic review

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 08 November 2022

Alcohol use disorder with comorbid anxiety disorder: a case report and focused literature review

- Victor Mocanu 1 , 2 &

- Evan Wood ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9412-6699 1 , 2

Addiction Science & Clinical Practice volume 17 , Article number: 62 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4490 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) and anxiety disorders (AnxD) are prevalent health concerns in clinical practice which frequently co-occur (AUD-AnxD) and compound one another. Concurrent AUD-AnxD poses a challenge for clinical management as approaches to treatment of one disorder may be ineffective or potentially counterproductive for the other disorder.

Case Presentation

We present the case of a middle-aged man with anxiety disorder, AUD, chronic pain, and gamma-hydroxybutyrate use in context of tapering prescribed benzodiazepines who experienced severe alcohol withdrawal episodes during a complicated course of repeated inpatient withdrawal management. After medical stabilization, the patient found significant improvement in symptoms and no return to alcohol use with a regimen of naltrexone targeting his AUD, gabapentin targeting both his AUD and AnxD, and engagement with integrated psychotherapy, Alcoholics Anonymous, and addictions medicine follow-up.

Proper recognition and interventions for AUD and AnxD, ideally with overlapping efficacy, can benefit individuals with comorbid AUD-AnxD. Gabapentin, tobacco cessation, and integrated psychotherapy have preliminary evidence of synergistic effects in AUD-AnxD. Meta-analysis evidence does not support serotoninergic medications (e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) which are commonly prescribed in AnxD and mood disorders as their use has not been associated with improved outcomes for AUD-AnxD. Additionally, several double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials have suggested that serotonergic medications may worsen alcohol-related outcomes in some individuals with AUD. Areas for future investigation are highlighted.

Introduction

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a prevalent health concern with a recent epidemiologic survey of the United States indicating a lifetime AUD prevalence of 29.1% and previous 12 month prevalence of 13.9% [ 1 ]. AUD portends an increased risk for diagnosis of a primary anxiety disorder (AnxD) [ 1 ], the definition of which, for the purposes of this case report, aligns with the most recent Canadian clinical practice guidelines for treatment of AnxD to include the DSM-IV umbrella of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), panic disorder, specific phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [ 2 ]. A quarter or more of individuals with AUD qualify for dual diagnosis with a concurrent primary AnxD in cross-sectional studies [ 3 ]. Furthermore, individuals with comorbid AUD-AnxD fare worse in terms of severity, treatment response, and rate of relapse for both conditions [ 3 ]. Alcohol intoxication, withdrawal, and biopsychosocial consequences of AUD may all contribute to AnxD symptomatology and vice versa, some individuals with a primary AnxD may use alcohol as self-medication. Alternatively, these conditions may share a common neuropathophysiology influenced by environmental factors at the level of brain structures such as the amygdala and neurotransmitters including gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA), endogenous opioids, dopamine, and serotonin, with implications for clinical management [ 3 ].

We present a case report of an individual with comorbid AUD-AnxD and review literature for treatment options to aid clinicians in applying best current evidence for such individuals. Literature review consisted of relevant published studies extracted from author collections and PubMed search with no language or date restrictions for combinations of the following terms: alcohol, alcohol use disorder, anxiety, anxiety disorder, comorbidity, dual diagnosis. In addition, reference lists of selected articles were reviewed for eligible and relevant studies. We find that commonly used treatment options for either AUD or AnxD can have a range of positive and potentially negative impacts for AUD-AnxD which requires accurate understanding of evidence-based care in this area.

A middle-aged man with a longstanding but reportedly well managed history of anxiety disorder dating back to childhood presented for medicalized alcohol withdrawal management services. The individual had a workplace injury approximately 10 years prior that resulted in several spine fractures after which his anxiety deteriorated and he developed AUD. Around this time, an SSRI was trialed for AnxD over several months without benefit and ultimately discontinued. He did not endorse a history for a mood disorder, nor had he received a diagnosis as such. He went on to live with chronic pain and AUD-AnxD for half a decade at which point he had an accidental caustic ingestion resulting in an esophagectomy and jejunostomy tube feeding for one year. His AUD-AnxD subsequently deteriorated further resulting in a prescription of benzodiazepines which were taken for approximately one month until the patient experienced rebound anxiety, worsening of his AUD, and the emergence of gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) use in the context of attempting to discontinue benzodiazepines. The individual sought care through an inpatient withdrawal management program where he had a number of repeated admissions complicated by alcohol withdrawal seizures. He was fortunately stabilized and benzodiazepines were tapered off at which point he was taking no other prescribed medications regularly. Prior to discharge, he was informed of AUD and AnxD treatment options. He was keen to engage with psychosocial supports while starting naltrexone 50 mg once daily and gabapentin 600 mg three times daily.

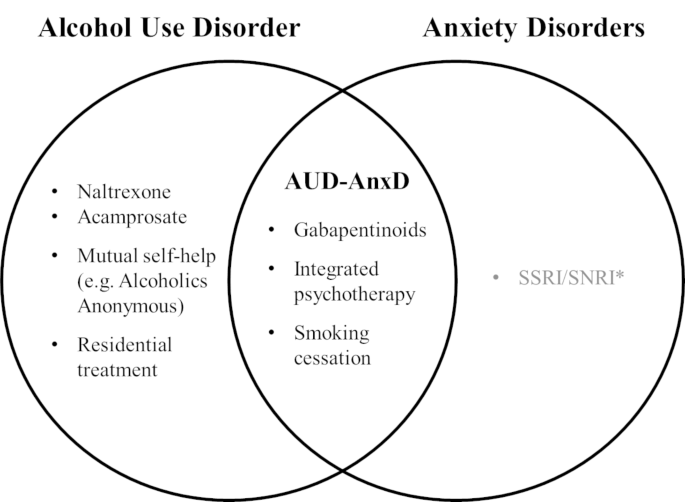

Eighteen months since discharge, he has found success engaging regularly with substance counselling, Alcoholics Anonymous, and outpatient addictions medicine as well as continuing with naltrexone and gabapentin, the majority of which were intended as synergistic treatments for AUD-AnxD (Fig. 1 ). He reports good health and no alcohol use, and although experiencing cravings, he describes feeling a shift from the sensation of “premeditated” or inevitable relapse as he had in previous attempts at reducing alcohol use.

Venn diagram of current evidence-based interventions reviewed for alcohol use and anxiety disorders

AUD-AnxD indicates comorbid alcohol use disorder and anxiety disorder

* Caution to be exercised with serotoninergic agents given evidence for potential worsening of alcohol outcomes in comorbid AUD-AnxD

Patient perspective

Hi, I’m here to share with you a little bit of the trial and tribulations endured over the many years of addiction. I was an individual who had a seemingly normal life, but under this was a person with undiagnosed mental problems. I was always a drinker who could take or leave drugs, and kept steady employment and had a very loving partner, it wasn’t until an injury in 2009 when my pace with alcohol quickened and I noticed that my consumption was now an everyday affair. Slowly I developed shakes and my day would start with vomiting until I had alcohol of some variety introduced, this continued on for many years and I was now a product of full-blown alcoholism. There now was no job, no partner and very few things that resembled a person who was still an active part of society. I was in and out of hospitals for experiencing multiple seizures and would go weeks with no food or water and begun isolating. I would become so weak physically that I could not move, and would some days awake in with bruises and cuts from either sizing or pass out, I was never sure which. Then I would begin my process of detox recovery house or treatment only to get home and start the vicious cycle again, some time I could stay sober longer if I was using GHB. Nothing would stop my craving and I no longer felt human. I wanted to die… I am proud to inform you that of Dec 12 2020 I have been living a life of sobriety but continue to struggle with cravings, but I use Alcoholics Anonymous as a support and by surrounding like minded people I find myself sober today.

Alcohol use disorder and anxiety

AUD and AnxD are common clinical concerns with evidence-based treatment options. Clinicians should recognize that when two conditions such as AUD and AnxD co-occur, clinical management may require nuance and differ from an approach taken in the context of an individual disorder. As we discuss below, research specifically concerning concurrent AUD-AnxD is still rare despite its high prevalence so data must often be extrapolated. The best available evidence indicates that approaches for treating one disorder may be efficacious, ineffective, or in fact counterproductive for comorbid AUD-AnxD.

AUD treatments

It is critical to recognize and offer proper treatment for AUD even when the primary presenting concern of a client may be an AnxD and vice versa. Whether sequential treatment of AUD and then AnxD, or vice versa, could reduce polypharmacy and iatrogenic harms versus their concurrent treatment remains largely unexplored. Unhealthy alcohol use and AUD are associated with more severe AnxD and conversely abstinence from alcohol is associated with improvement of AnxD [ 3 , 4 ]. To that effect, longitudinal strategies to address AUD may improve AnxD by extension. As conveyed by the reflections of the individual described in the present report, motivational enhancement, formal psychotherapy, mutual self-help interventions such as Alcoholics Anonymous, and supportive settings such as residential treatment facilities, all highlighting the health benefits of reduction or cessation of alcohol use, can serve an important psychosocial role alongside appropriate evidence-based AUD pharmacotherapy [ 5 ]. Nevertheless, the question remains whether certain interventions have additional efficacy in AnxD beyond their efficacy for AUD.

Naltrexone and Acamprosate

Naltrexone is a first-line evidence-based pharmacotherapy which functions as a non-selective opioid antagonist, reducing the rewarding effects of alcohol use mediated by endogenous opioids and downstream neurotransmitters. Studies have demonstrated efficacy for reducing binge drinking (number needed to treat [NNT] = 12) as well as relapse to any alcohol use (NNT = 20) [ 5 ], which motivated our use of naltrexone in the case strongly featuring AUD. To our knowledge, no clinical trial has yet effectively addressed whether naltrexone treatment for AUD can improve a comorbid AnxD, nor an AnxD disorder in isolation.

Acamprosate, which modulates glutamate and GABA signaling disrupted by chronic alcohol use, is another first-line AUD medication effective in preventing relapse to any alcohol use (NNT = 12) [ 5 ]. In terms of comorbid AnxD, some preliminary data suggests benefit of acamprosate for augmentation in various AnxD at doses equivalent or lower than those used in AUD [ 6 ]. However, as with naltrexone, there is a paucity of data to confidently gauge the effect of these first-line AUD medications on a comorbid AnxD and further research would be valuable in this area.

Gabapentinoids

Gabapentinoids such as gabapentin and pregabalin also modulate glutamate and GABA signaling implicated in AnxD and AUD specifically by antagonism of voltage-gated calcium channels. For AUD, gabapentin can be used in the short-term to treat alcohol withdrawal symptoms and in the longer-term to reduce heavy drinking days although efficacy for other endpoints such as reduction in cravings is debated [ 7 ]. Importantly, the data suggest that a key element of clinical efficacy of gabapentin is appropriate patient selection, specifically those with more severe AUD and alcohol withdrawal symptoms. For example, a recent positive randomized clinical trial (RCT) of gabapentin in AUD, which excluded any major psychiatric condition besides PTSD, found that patients with less severe withdrawal tended to fare worse numerically on all indices of alcohol use compared to placebo, although not statistically significant [ 8 ]. To date, some literature exists to support using pregabalin during alcohol withdrawal but data for longer-term treatment of AUD is very limited [ 5 ]. Interestingly, a RCT comparing pregabalin versus naltrexone in subjects with AUD (approximately 15% with comorbid AnxD in each arm) suggested pregabalin was about as effective as naltrexone in terms of AUD outcomes and more effective in reducing phobic anxiety, a subscale of the particular psychiatric questionnaire used in the study [ 9 ]. Further research is needed in this area to better characterize the efficacy of gabapentinoids for treating AnxD specifically in individuals with AUD-AnxD.

The available evidence more strongly supports efficacy of gabapentinoids in treatment of isolated primary AnxD. Gabapentin may be effective for several types of AnxD, [ 2 ] although to our knowledge there is no high-quality data yet available to support gabapentin for treatment of GAD which is frequently encountered in clinical practice. On the other hand, pregabalin has extensive data demonstrating efficacy for GAD as well as SAD, so much so that national practice guidelines currently view pregabalin as a first-line agent for these two conditions [ 2 ].

In sum, the current evidence indicates gabapentinoids have a role in the treatment of both AUD and AnxD and this class of medications may hold promise for treatment of comorbid AUD-AnxD. This emerging evidence supported the prescription of gabapentin in the above case which we believe ultimately contributed to the substantial benefit the individual found with the regimen described. In the interim while further evidence accumulates, a pertinent consideration in the application of gabapentinoids remains the risk of misuse. Gabapentin misuse occurs in the general population, particularly those with substance use disorders, for a variety of reasons including self-medication (e.g. anxiety, pain, and drug withdrawal symptoms) as well as documented recreational use or self-harm [ 10 ]. Even in context of supportive evidence, clinicians should nevertheless be aware of these reports and potential for gabapentinoids to be misused or diverted in treatment of AUD, AnxD, or overlap AUD-AnxD.

Other studied AUD medications

Other medications which have received research attention for AUD include baclofen, topiramate, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines [ 5 ]. The evidence base for these agents is even more limited and inconclusive in the realm of AUD and comorbid AUD-AnxD. For example, baclofen is a GABA-B agonist medication with a Cochrane systematic review finding conflicting evidence for AUD, comorbid anxiety, and lack of high-quality evidence for use in alcohol withdrawal [ 11 ].

AnxD pharmacotherapies

Psychotropics.

Regarding selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the prevalent pharmacologic treatment for AnxD [ 2 ], a Cochrane systematic review of RCTs for comorbid AUD-AnxD found modest improvements in anxiety measures but unreliable or even unhelpful effects on comorbid AUD [ 12 ]. At this juncture, we acknowledge SSRIs are also frequently prescribed according to clinical practice guidelines for treatment of mood disorders that can be challenging to distinguish clinically from AUD and AnxD, which are commonly comorbid [ 13 ]. Nevertheless, meta-analyses demonstrate a lack of benefit of SSRIs in the context of AUD with mood disorder with similar concerns of worsening outcomes [ 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Given the common co-presentation of anxiety and depression among individuals with AUD, the following discussion instead explores the literature from the perspective of AUD outcomes for individuals with any exposure to SSRI or other serotoninergic medications, such as the individual in our case report, regardless of the primary indication for their use. Notably, comorbid mood and anxiety disorders are frequently reported in the available studies and often served as the primary indication for SSRI use.

We note with interest the underappreciated phenomenon of enhanced serotoninergic neurotransmission exacerbating AUD for certain individuals. For example, a secondary analysis of a RCT studying naltrexone for individuals with AUD and comorbid mood and anxiety disorders found prescriptions for SSRI outside of study protocol during follow-up to be associated with worse drinking outcomes for participants randomized to placebo, an effect which was attenuated if participants received naltrexone [ 17 ]. More convincing evidence supporting the potential for harm also exists in several RCTs. In an RCT of the SSRI citalopram for AUD in which mood, AnxD, and both disorders were highly comorbid, participants consumed more alcohol on more days compared to placebo regardless of mood or anxiety measures [ 16 ]. Several trials have also evaluated sertraline in AUD and found that younger participants with more severe AUD in particular tend to fare worse when prescribed an SSRI [ 18 ], moderated in part by the presence of an allele of the serotonin transporter gene favoring greater serotonergic tone [ 18 ]. However, these data are complicated to apply in clinical practice since the predisposing allele may also be found in older participants who happen to develop AUD later in life. Based on allele prevalence in the general US population, Kranzler et al. extrapolated that approximately double the number of individuals with AUD on a population level would be adversely affected by unselected SSRI treatment rather than find benefit [ 18 ]. One small trial comparing combinations of venlafaxine and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for AUD found the only effective treatment for reducing heavy drinking days to be CBT alone with placebo medication, suggesting that selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors such as venlafaxine may likewise be unhelpful for AUD outcomes [ 19 ].

Trazodone, another psychotropic medication which modulates serotonin transmission, although used for mood disorders and insomnia rather than AnxD, should be addressed in context of AUD. Trazodone is occasionally prescribed with intent as an antidepressant and sleep aid for individuals with AUD but one RCT found a minimal short-term improvement in sleep quality, while also reporting reduced abstinent days, and increased severity of alcohol consumption following withdrawl of trazodone [ 20 ].

In sum, despite the evidence for first-line treatment of isolated AnxD or mood disorders with serotoninergic agents such as SSRIs, clinicians should reconsider and exercise caution in prescribing these medications for patients with comorbid AUD given current observational, RCT, and meta-analysis evidence demonstrating lack of benefit and potential of harm to alcohol use outcomes. In the interim, further investigation is needed to clarify which selected subpopulations in clinical practice would benefit from step-wise approach later involving serotoninergic agents or conversely serotonin antagonists [ 21 ]. Careful use of pharmacologic agents targeting AnxD, such as pregabalin or gabapentin, in tandem with other biopsychosocial strategies may have more of an evidence-based role to play since AnxD are frequently comorbid, have been reported to more frequently precede rather than follow AUD [ 3 ], and are associated with worsening of AUD [ 22 ], suggesting that effective treatment of AnxD may prevent AUD deterioration.

Tobacco cessation

Although not directly relevant to the individual described in our case report, tobacco use may impact clinical outcomes for individuals with AUD-AnxD. Research indicates that weekly smoking in youth is a risk factor for worsening of AUD [ 22 ], and tobacco cessation has been shown to improve anxiety symptoms for both individuals with and without psychiatric disorders [ 23 ]. For instance, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that the nicotinic receptor partial agonist varenicline was safe and conferred a 25% lower risk of anxiety compared to placebo - likely a result of reduction and cessation in tobacco use [ 24 ]. However, data specific to AUD-AnxD clinical outcomes after tobacco cessation interventions is still limited and inconclusive to date [ 25 ]. In addition to other known broad health benefits such as reduced incidence of cardiovascular disease and cancer, the cessation of tobacco use may also play a synergistic role in treatment of AUD-AnxD.

Psychotherapies

Formal psychotherapy holds promise for addressing the propagating psychosocial factors of AUD and AnxD alone or in addition to pharmacotherapy. In the realm of AnxD, CBT can be equally or more effective than medication alone [ 2 ]. For comorbid AUD-AnxD, motivational interviewing and CBT are effective for both conditions, especially as longer-term modalities with more durable efficacy [ 26 ]. Such targeted and integrated psychotherapy might be particularly effective for individuals with AnxD attempting to self-medicate anxiety symptoms by using alcohol.

Teaching points

AnxD and AUD are prevalent health concerns which frequently co-occur and can compound one another as demonstrated in our report. Their co-occurrence requires a thoughtful approach to treatment given the evidence that treatments of one disorder have been shown to be ineffective or counterproductive for the other disorder (Fig. 1 ). Although evidence is scarce for synergistic treatments of comorbid AUD-AnxD, the literature supports overlapping efficacy of tobacco cessation, use of gabapentinoids, and integrated psychotherapy, the latter two of which were applied with success for the individual in this case report. While the first-line AUD pharmacotherapies naltrexone and acamprosate do not yet have evidence of concurrent benefit for AnxD, effectively treating AUD may yield downstream benefit for AnxD as suggested by treatment response in this report. Lastly, caution should be exercised with serotoninergic medications such as SSRIs as there appears to be underappreciated evidence suggesting that SSRIs are not of benefit in the context of AUD [ 12 ], and may actually worsen alcohol related outcomes for certain individuals [ 16 ]. Further investigation is needed to understand synergistic versus step-wise approaches to treatment of comorbid AUD-AnxD and identification of specific population subgroups which may derive benefit with serotoninergic agonists versus antagonists.

Data availability

Not applicable to case report.

Abbreviations

anxiety disorder

alcohol use disorder

comorbid alcohol use disorder and anxiety disorder

cognitive Behavioral Therapy

gamma aminobutyric acid

generalized anxiety disorder

gamma-hydroxybutyrate

post-traumatic stress disorder

randomized clinical trial

social anxiety disorder

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry Aug. 2015;72(8):757–66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Katzman MA, Bleau P, Blier P, et al. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(Suppl 1):1. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-S1-S1 .

Article Google Scholar

Anker JJ, Kushner MG. Co-Occurring Alcohol Use Disorder and Anxiety: Bridging Psychiatric, Psychological, and Neurobiological Perspectives. Alcohol Res. 2019;40(1)doi: https://doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v40.1.03 .

Driessen M, Meier S, Hill A, Wetterling T, Lange W, Junghanns K. The course of anxiety, depression and drinking behaviours after completed detoxification in alcoholics with and without comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders. Alcohol Alcohol . 2001 May-Jun. 2001;36(3):249–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/36.3.249 .

British Columbia Centre on Substance Use (BCCSU), B.C. Ministry of Health, B.C. Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions. Provincial Guideline for the Clinical Management of High-Risk Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder. BCCSU; 2019. https://www.bccsu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/AUD-Guideline.pdf .

Hertzman M, Patt IS, Spielman LA. Open-label trial of acamprosate as a treatment for anxiety. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(5):267. doi: https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.08l00714 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kranzler HR, Feinn R, Morris P, Hartwell EE. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of gabapentin for treating alcohol use disorder. Addiction. 2019;09(9):1547–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14655 . 114 ) .

Anton RF, Latham P, Voronin K, et al. Efficacy of Gabapentin for the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder in Patients With Alcohol Withdrawal Symptoms: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. Mar 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0249 .

Martinotti G, Di Nicola M, Tedeschi D, et al. Pregabalin versus naltrexone in alcohol dependence: a randomised, double-blind, comparison trial. J Psychopharmacol Sep. 2010;24(9):1367–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881109102623 .

Smith RV, Havens JR, Walsh SL. Gabapentin misuse, abuse and diversion: a systematic review. Addict 07. 2016;111(7):1160–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13324 .

Minozzi S, Saulle R, Rösner S. Baclofen for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Nov. 2018;11:CD012557. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012557.pub2 .

Ipser JC, Wilson D, Akindipe TO, Sager C, Stein DJ. Pharmacotherapy for anxiety and comorbid alcohol use disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Jan. 2015;1:CD007505. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007505.pub2 .

Beaulieu S, Saury S, Sareen J, et al. The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid substance use disorders. Ann Clin Psychiatry Feb. 2012;24(1):38–55.

Google Scholar

Agabio R, Trogu E, Pani PP. Antidepressants for the treatment of people with co-occurring depression and alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;04:4:CD008581. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008581.pub2 .

Grant S, Azhar G, Han E, et al. Clinical interventions for adults with comorbid alcohol use and depressive disorders: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2021;10(10):e1003822. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003822 . 18 ) .

Charney DA, Heath LM, Zikos E, Palacios-Boix J, Gill KJ. Poorer Drinking Outcomes with Citalopram Treatment for Alcohol Dependence: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res Sep. 2015;39(9):1756–65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12802 .

Krystal JH, Gueorguieva R, Cramer J, Collins J, Rosenheck R, Team VCNS. Naltrexone is associated with reduced drinking by alcohol dependent patients receiving antidepressants for mood and anxiety symptoms: results from VA Cooperative Study No. 425, “Naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism”. Alcohol Clin Exp Res Jan. 2008;32(1):85–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00555.x .

Kranzler HR, Armeli S, Tennen H, et al. A double-blind, randomized trial of sertraline for alcohol dependence: moderation by age of onset [corrected] and 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter-linked promoter region genotype. J Clin Psychopharmacol Feb. 2011;31(1):22–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e31820465fa .

Ciraulo DA, Barlow DH, Gulliver SB, et al. The effects of venlafaxine and cognitive behavioral therapy alone and combined in the treatment of co-morbid alcohol use-anxiety disorders. Behav Res Ther Nov. 2013;51(11):729–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.08.003 .

Stein MD, Kurth ME, Sharkey KM, Anderson BJ, Corso RP, Millman RP. Trazodone for sleep disturbance during methadone maintenance: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend Jan. 2012;120(1–3):65–73. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.026 .

Johnson BA, Roache JD, Javors MA, et al. Ondansetron for reduction of drinking among biologically predisposed alcoholic patients: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA . 2000 Aug 23–30 2000;284(8):963 – 71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.8.963 .

Conway KP, Swendsen J, Husky MM, He JP, Merikangas KR. Association of Lifetime Mental Disorders and Subsequent Alcohol and Illicit Drug Use: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry Apr. 2016;55(4):280–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.01.006 .

Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, Farley A, Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed) Feb 13. 2014;348:g1151. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1151 .

Thomas KH, Martin RM, Knipe DW, Higgins JP, Gunnell D. Risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with varenicline: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Mar. 2015;12:350:h1109. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1109 .

Kodl M, Fu SS, Joseph AM. Tobacco cessation treatment for alcohol-dependent smokers: when is the best time? Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(3):203–7.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Baker AL, Thornton LK, Hiles S, Hides L, Lubman DI. Psychological interventions for alcohol misuse among people with co-occurring depression or anxiety disorders: a systematic review. J Affect Disord Aug. 2012;139(3):217–29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.004 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This development of this article was not supported by any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, 400-1045, V6Z 2A9, Howe St, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Victor Mocanu & Evan Wood

Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, 2255 Wesbrook Mall, V6T 2A1, Vancouver, BC, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

VM and EW were involved in conception, design, planning, drafting, revision, and final approval of the manuscript. EW was directly involved in patient care and data collection.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Evan Wood .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Per local University of British Columbia and Providence Health Care ethics boards, case reports do not meet the formal definition for research and ethics approval was waived.

Consent to publish

Written consent, manuscript feedback, and final approval was granted by the individual to present their anonymized information and reflection.

Competing interests

EW served as the Chief Medical Officer at Numinus Wellness, a Canadian company interested in medical application of psychedelic substances. Numinus Wellness was not involved in the conception, planning, writing or decision to submit this manuscript for publication. EW is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research through the Canada Research Chairs Program. No other competing interests were declared.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mocanu, V., Wood, E. Alcohol use disorder with comorbid anxiety disorder: a case report and focused literature review. Addict Sci Clin Pract 17 , 62 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-022-00344-z

Download citation

Received : 27 June 2022

Accepted : 19 October 2022

Published : 08 November 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-022-00344-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Comorbidity

- Dual diagnosis

- Treatment recommendations

Addiction Science & Clinical Practice

ISSN: 1940-0640

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Addictive Behaviour: Molecules to Mankind pp 260–291 Cite as

Alcohol Abuse in Society: Case Studies

- Adrian Bonner 3 &

- James Waterhouse 4

34 Accesses

The last three chapters have demonstrated how routine data may be collected from the health service and forensic medicine. These data present a view of the occurrence of alcohol and drug abuse in society which is generated from a ‘medical model’. As useful as this approach is, it does not take into account the nature and needs of specific groups. To do this a more ‘socially appropriate perspective’ can be used. The following case studies illustrate some of the problems resulting from methodological issues in this area of investigation and, in particular, from studies undertaken in short-term projects undertaken by graduate students. Important discussions relating to: ‘what level of consumption constitutes abuse ’ ‘alcohol usage by the elderly’, and ‘the effectiveness of health education’ will be introduced.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Anderson, P. (1984) ‘Alcohol Consumption of Undergraduates at Oxford University’, Alcohol and Alcoholism , 19:pp. 77–84.

Google Scholar

Black, D. and Weare, K. (1989) ‘Knowledge and Attitudes about Alcohol in 17- and 18-Year-Olds’, Health Education Journal , 48 (2):pp. 69–73.

Article Google Scholar

Cyster, R. and McEwen, J. (1987) ‘Alcohol Education in the Workplace’, Health Education Journal , 46 (4):pp. 156–61.

Davies, J. (1991) ‘Learning to Drink’, paper presented at a national conference on ‘Alcohol and Young People’, 8 October 1991, Queen Mother Conference Centre, Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh.

Gillies, P. (1991) ‘What Can Education Achieve?’, paper presented at a national conference on ‘Alcohol and Young People’, 8 October 1991, Queen Mother Conference Centre, Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh.

Grant, M. (1981) ‘Aims, Form and Content: First Steps in Developing a Taxonomy of Preventative Education in Drug and Alcohol Abuse’, in L. R. H. Drew et al . (eds), Man, Drugs, and Society: Current Perspectives (Canberra: Australian Foundation on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence).

Haack, M. (1988) ‘Stress and Impairment among Nursing Students’, Research in Nursing and Health , 11:pp. 125–34.

Haack, M. and Harford, T. (1984) ‘Drinking Patterns among Student Nurses’, The International Journal of the Addictions , 19 (5):pp. 577–83.

Hopkins, R., Maussa, A., Kearney, K. and Weisheit, R. (1988) ‘Comprehensive Evaluation of a Model Alcohol Education Curriculum’, Journal of Studies on Alcohol , 49 (1):pp. 38–50.

Hutchison, S. (1986) ‘Chemically Dependent Nurses: The Trajectory towards Self Annihilation’, Nursing Research , 35 (July/August):pp. 196–201.

Maussa, A., Hopkins, R., Weisheit, R., and Kearney, K. (1988) The Problematic Prospects for Prevention in the Classroom: Should Alcohol Education Programmes be Expected to Reduce Drinking by Youth?’, Journal of Studies in Alcohol , 49 (1):pp. 51–61.

Plant, M. (1991) ‘Heavy Drinkers: Are They Distinctive?’, paper presented at a national conference on ‘Alcohol and Young People’, 8 October 1991, Queen Mother Conference Centre, Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh.

Plant, M. L., Plant, M. A. and Foster, J. (1991) ‘Alcohol, Tobacco and Illicit Drug Use Amongst Nurses: A Scottish Study’, Drug and Alcohol Dependence , 28:pp. 195–202.

Roberts, R. (1988) ‘Hiccups in Alcohol Education’, Health Education Journal , 47 (213):pp. 73–5.

Royal College of General Practitioners (1986) Alcohol: A Balanced View (London: Tavistock).

Saltz, R., and Elandt, D. (1986) ‘College Students Drinking Studies 1976–1985’, Contemporary Drug Problems (Spring):pp. 117–59.

Wallace, P., Brennan, P., and Haines, A. (1987) ‘Drinking Patterns in General Practice Patients’, Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners , 37:pp. 354–7.

Weichsler, H. and McFadden, M. (1979) ‘Drinking among College Students in New England; Extent, Social Correlates and Consequences of Alcohol’, Journal of Studies on Alcohol , 40:pp. 969–99.

West, R., Drummond, C., and Eames, K. (1990) ‘Alcohol Consumption, Problem Drinking and Anti-Social Behaviour in a Sample of College Students’, British Journal of Addiction , 85:pp. 479–86.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Addictive Behaviour Centre Roehampton Institute, London, UK

Adrian Bonner ( Director )

School of Biological Sciences, School of Human Biology, University of Manchester, UK

James Waterhouse ( Senior Research Fellow, Lecturer in Physiology )

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Adrian Bonner ( Director ) ( Director )

James Waterhouse ( Senior Research Fellow, Lecturer in Physiology ) ( Senior Research Fellow, Lecturer in Physiology )

Copyright information

© 1996 Adrian Bonner and James Waterhouse

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Bonner, A., Waterhouse, J. (1996). Alcohol Abuse in Society: Case Studies. In: Bonner, A., Waterhouse, J. (eds) Addictive Behaviour: Molecules to Mankind. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-24657-1_17

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-24657-1_17

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-0-333-64556-7

Online ISBN : 978-1-349-24657-1

eBook Packages : Palgrave Social & Cultural Studies Collection Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

News & Events

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)

Research insights into alcoholism and alcohol abuse highlighted in 10th special report.

Saturday, November 11, 2000

Secretary of Health and Human Services Donna E. Shalala has announced the availability of the 10th Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health , produced by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). The report highlights recent research advances on the causes, consequences, treatment, and prevention of alcohol addiction (alcoholism) and alcohol abuse.

The 492-page report, available in print and on the internet, documents the scope of alcohol’s impact on society. The effects range from violence to traffic crashes to lost productivity to illness and premature death—all of which, combined, cost our nation an estimated $184.6 billion per year. The report also conveys the rapid progress of research into the genetic and environmental factors that can lead to alcohol addiction. Scientists are using these insights to develop and test new ways of preventing and treating this disease. "Alcohol problems can yield to scientific investigation and medical intervention in the same way as other health conditions," writes DHHS Secretary Donna Shalala in the foreword.

The new report presents advances in alcohol research since 1997, when the last edition of Alcohol and Health was published. "This report reflects the tremendous growth in the scope of alcohol research," according to NIAAA Director Enoch Gordis, M.D. Contemporary alcohol research spans all life stages—from prenatal alcohol exposure to drinking problems in the elderly—and applies the latest methods of basic, epidemiological, clinical, behavioral, and social sciences research, often in multidisciplinary collaborations. The following research areas are among those detailed in the 10 th Report :

Genetics of alcoholism. Two studies have found evidence of genes on specific chromosomes influencing susceptibility to alcoholism. The ongoing Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA), which involves 987 individuals from high-risk families, reported suggestive evidence of genes on chromosomes 1 and 7 involved in alcoholism. An early report from the study also reported weaker evidence of such a gene on chromosome 2. Another study from NIAAA’s Laboratory of Neurogenetics, based on 152 members of a southwestern Native American tribe, reported suggestive evidence for a gene influencing susceptibility to alcoholism on chromosome 11. Both studies reported finding evidence of a gene that was protective against alcoholism in a region of chromosome 4.

Heavy drinking during pregnancy and fetal brain development. Applying advances in neuroimaging and cellular and molecular biology, alcohol researchers are gaining an increasingly clear picture of the physical nature of alcohol-induced damage to the developing brain and the mechanisms that cause the damage. Imaging studies have demonstrated structural abnormalities in certain brain regions, whereas other regions seem to be spared. Research also shows that a number of deficits in cognitive and motor functions are linked to prenatal alcohol exposure, while other functions appear to remain intact. These studies, as well as basic research on the mechanisms of prenatal alcohol damage, support the notion that alcohol has specific, rather than global, effects on the developing brain.

Preventing underage drinking. One major study, the Community Trials Project, found that sales clerks in alcoholic beverage outlets were half as likely to sell alcohol to minors in communities with programs that trained clerks, enforced underage sales laws, and raised awareness of increased enforcement through the media. Another large study, Project Northland, showed that a multi-year program involving schools, parents, peers, policy-makers, and businesses can effectively reduce underage drinking—if the intervention begins before adolescents begin to use alcohol. The 10th Report also describes the search for the roots of alcohol problems in adolescence and later life stages, through multidisciplinary research on social, cultural, psychological, and biological influences.

Reducing alcohol-related traffic crashes. The 10 th Report presents many studies on the effectiveness of laws, public policies, community programs, and individual actions to deter drunk driving. A number of studies have focused on State laws that make it a criminal offense to drive with a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) over a certain limit, which in most States is 0.10 percent. New research shows that States that reduce the legal BAC limit to 0.08 percent experience a significant drop in fatal crashes related to alcohol, and that this decrease is distinct from the effects of other drunk driving measures.

Chronic alcohol use and the brain. Studies in animal models are revealing how changes in the brain from chronic alcohol consumption underlie such features of alcoholism as tolerance (lowered sensitivity to the intoxicating effects of alcohol), withdrawal, and craving. This work is helping scientists understand the biological basis for the motivation to drink too much and the mechanisms through which alcohol causes lasting damage to the brain in some individuals who consume alcohol heavily.

Damage to body organs. Research on how alcohol damages body organs is providing information that may be used in developing novel treatments. For example, a variety of evidence suggests that liver damage results from changes in immune function, suggesting the potential of immune-based treatments.

Helping patients to reduce alcohol use and related problems. When patients are found to be at-risk or problem drinkers, but not alcohol dependent, health care providers can significantly reduce alcohol use and related problems by providing a quick form of counseling called "brief intervention." Research shows that brief interventions delivered in primary care settings can decrease alcohol use for at least a year in persons who drink above recommended limits.

Medications for treating alcoholism. Advances in neuroscience have paved the way for medications that operate at the molecular level of brain processes that influence alcohol addiction. Studies show that the medication naltrexone and a similar compound, nalmefene, help reduce the chance of heavy drinking when abstinent individuals relapse; that a medication called acamprosate may prevent relapse; and that when patients with co-existing depression take antidepressants, their alcoholism treatment outcomes improve.

The report contains eight chapters: (1) Drinking Over the Life Span: Issues of Biology, Behavior and Risk, (2) Alcohol and the Brain: Neuroscience and Neurobehavior, (3) Genetic and Psychosocial Influences, (4) Medical Consequences, (5) Prenatal Exposure to Alcohol, (6) Economic and Health Services Perspectives, (7) Prevention, and (8) Treatment. Each chapter is divided into two to six subsections that can be downloaded individually in PDF format from the NIAAA website ( http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/ ). Bound copies of the entire 492-page report can also be ordered by writing to: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Publications Distribution Center, P.O. Box 10686, Rockville, MD 20849-0686.

The NIAAA produced the 10 th Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health with guidance from a distinguished editorial advisory board and contributions from some of the world’s leading alcohol researchers. A component of the National Institutes of Health, NIAAA funds more than 90 percent of the alcohol abuse and alcohol addiction (alcoholism) research in the United States.

About the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA): The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), part of the National Institutes of Health, is the primary U.S. agency for conducting and supporting research on the causes, consequences, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of alcohol use disorder. NIAAA also disseminates research findings to general, professional, and academic audiences. Additional alcohol research information and publications are available at www.niaaa.nih.gov .

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov .

Contact info : NIAAA Press Office 301-443-2857 [email protected]

niaaa.nih.gov

An official website of the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Study shows increase in serious alcohol-related complications early in pandemic

A new study in JAMA Health Forum shows increases in serious alcohol-related complications in 4 of 18 COVID-19 pandemic months studied (through September 2021), and suggests that women aged 40 to 64 years experienced increases of 33.3% to 56.0% in serious alcohol complication episodes in 10 of the 18 months.

The study is based on US national insurance claims data from March 2017 to September 2021, with researchers comparing prepandemic rates of serious alcohol-related problems to rates seen during pandemic months. A secondary outcome was the subset of episodes of alcohol-related liver disease (ALD).

Overall, in 4 of the 18 pandemic months beginning in March 2020, rates of serious alcohol-related issues were statistically higher than expected, the authors said, by 0.4 to 0.8 episodes per 100,000 people.