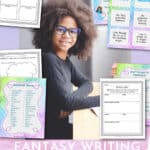

Fantasy Writing Unit of Study

Help guide your students through the fantasy writing process with this fantasy writing unit of study.

This is another free writing unit of study from The Curriculum Corner!

Add this fantasy writing unit of study to your writing studies during the school year.

So many students have a great imagination. They are excited to attempt fantasy pieces of writing. What we find they often lack is a problem and a solution.

We have created this unit of study to help your students write a complete fantasy story. These free writing lessons are geared towards second and third grade students.

For this writing unit, we do not have children begin writing fantasy stories right away. We first build a good foundation.

This unit is newly updated to include additional resources. Also, you will not find a PDF of the lessons as described in this post. This is great for those teachers who like to print out a copy for future years.

How should I begin my unit of study?

As always we begin our writing unit of study with a day or two of noticings..

We pull together our favorite fantasy books in the classroom. We introduce the idea of a fantasy book by reading aloud an example.

One of our favorites is a book from The Magic Treehouse series. Students enjoy these and they contain many elements of a fantasy. As we read aloud, we bring up the idea of reality versus fantasy.

Within the download we have created you will find a Mentor Texts chart. Record the books you use as mentor texts for this unit on this page. Along with the title, write down the location of the book. This will make it easier to find the books you used next year!

What are noticings?

To begin noticings, we partner up students and give them each a book or two that is a good example of a fantasy book. We hand students a few post it notes and give them a chance to search for features of a fantasy text.

Remember, this is before we have created an anchor chart so some answers may be true and some may not be. This is ok…both will give you more to discuss when you pull back together as a class.

As students complete their noticings, make sure you filter around to talk with the kids about what they are noticing. This activity may last 20 minutes or it may take an hour – it depends on your students. When you feel like most groups are finished, pull back together as a class.

We have included a noticings page you may use if you would like your students to record their observations.

Anchor Charts

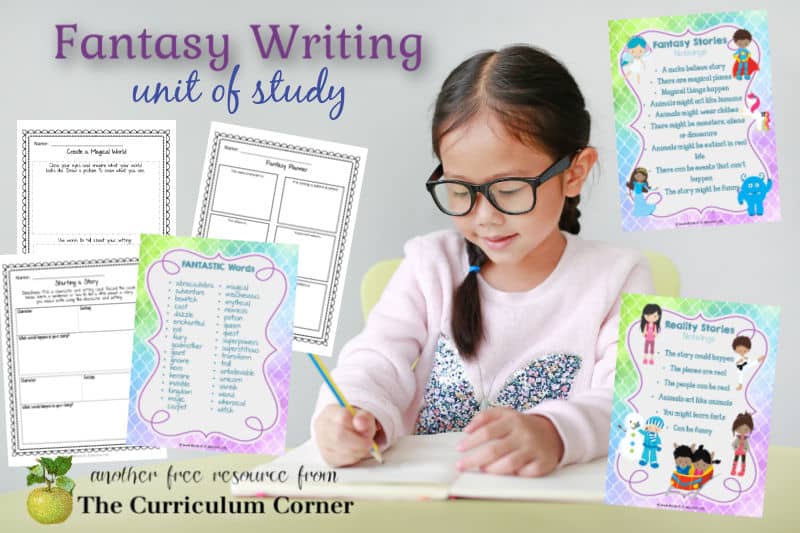

When you pull back together, create an anchor chart that includes the aspects of a fantasy story that you have found. We have created printable and colorful samples you might choose to use. We have also created a reality anchor chart if your students need a visual to help them compare.

There is a T-chart students can use to record the differences they find between fantasy and reality.

Within the resources, you will find graphic organizers designed for you to give to students along with a fantasy and a reality book.

Students look for the differences and fill out the graphic organizer in order to show their understanding.

Fantasy and Reality Sort For an easy literacy center, you will find a card sort for students to sort the events between fantasy and reality.

There is also a blank page so that students can create their own events as an extension. Simply print and laminate the blank page and students can use a vis-a-vis marker.

Introducing Fantasy Characters

You can choose any favorite book with characters that are not real for this mini-lesson.

One of our favorites is Click Clack Moo. We like it because it is a familiar text with many examples of what characters can do that are not real.

After reading aloud the story, talk about what makes the characters fantasy characters. Responses should refer to the human-like actions of the animals.

Introducing Fantasy Settings

Again, this lesson can be completed with any fantasy book with a good example of an imaginary world.

After reading the book, discuss the fantasy setting. Have students share how they know the setting is imaginary.

Problem & Solution

This is often the most difficult part for students to include in their fantasy writing.

Students tend to have a problem, but forget to include a solution.

Or, the story created is a list of events without a problem to solve.

For this reason, this is a good topic to focus on for more than one day.

After a read aloud, we like to have students complete a story map or a simple graphic organizer like this one: Problem & Solution.

We like to follow the whole group lesson up with an independent practice the following day.

Starting a Story

You will find pages with ten cards on each. One has labels for characters and the other for settings. These can be printed on card stock and laminated for future use. There is also an additional blank page.

Have students choose one of each card. You might place them in a basket and have students pick without looking. Or, you can allow children to choose the cards that interest them the most.

Children will then take their two cards and complete the Starting a Story page.

These pages can be completed in small groups or as a literacy center activity.

Have students save their pages in their writing folders. These can then be used as story starters later on.

Planning Your Writing

Model for students how to create a fantasy planner for their books.

Use one of our Fantasy Writing Planners and have children plan their own stories.

Remind students that it is ok to use a familiar character or setting from a favorite book. Their job is to create a new story using that character or setting.

Create a Magical World This graphic organizer can be used at any point in this unit to get your students thinking about their setting.

Fantastic Words This simple anchor chart of words might be used as a word wall or simply a tool to get your students thinking about possibilities.

Includes two graphic organizers for students who want to make a list of words they will use in their writing.

Working on Capitalization

In order to help students become better writers, we like to include a grammar focus in each unit.

We have included an anchor chart and checklists for students to use when checking for correct capitalization.

Of course, it is always best to first talk about and practice this skill in a mini-lesson. Then review as needed.

If there are other grammar skills you find students need practice with, review in small groups or with a whole class mini-lesson if needed.

Celebration

Every publishing should end with a celebration to recognize your students’ writing growth! We have included colorful certificates and dedication bookplates for books.

You can download this free writing unit here:

Writing Download

We have also pulled all of the lesson plans above into a PDF. You can download this here:

Lesson Plan Download

Looking for other free writing resources? You might like these:

Thank you to PrettyGrafik for the always cute clip art!

Looking for some mentor texts to fill your basket? Take a look at some we’ve found: (contains affiliate links)

As with all of our resources, The Curriculum Corner creates these for free classroom use. Our products may not be sold. You may print and copy for your personal classroom use. These are also great for home school families!

You may not modify and resell in any form. Please let us know if you have any questions.

Tuesday 26th of October 2021

Thank you so much, this is so helpful in planning my fantasy writing unit with my second graders!

Planning a Dynamic Writing Workshop - The Curriculum Corner 123

Sunday 24th of June 2018

[…] Fantasy Writing […]

Fantasy & Reality Card Sort - The Curriculum Corner 123

Friday 11th of May 2018

[…] Fantasy Writing Unit of Study […]

Thursday 3rd of December 2015

Great stuff

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Teaching Fantasy Writing Lessons That Inspire Student Engagement and Creativity, Grades K-6

- Carl Anderson

Foreword by Matt Glover

- Description

Teaching fantasy writing increases student engagement, enables them to flex their creative muscles – and helps them learn important narrative writing skills.

Opportunities for kids to lean into their innate creativity and imagination have been squeezed out of most school days, due to the pressures of standardized testing. And writing instruction has become more and more formulaic. In Teaching Fantasy Writing , Carl Anderson shows you how to include a study of fantasy writing in your writing curriculum that will engage student interest and creativity -- and make writing exciting for them again.

Teaching Fantasy Writing is a game-changer. The fantasy genre gives children tools for expression that other genres don’t, providing them with a powerful way to work through challenging issues and emotions. And it also offers students the opportunity to address subjects such as gaining confidence in oneself, bullying, fighting injustice – and more.

Plus, fantasy writing helps kids learn the skills necessary to meet narrative writing standards. And they’ll have fun doing it!

If you’re an elementary school teacher who wants to help your students develop their writing skills by studying a high-interest, high-impact genre, you’ve come to the right place. In Teaching Fantasy Writing , Carl Anderson will:

- Discuss why fantasy writing develops students’ creativity, increases their engagement in writing, and accelerates their growth as writers

- Walk you through fantasy units for students in grades K-1, 2-3, and 4-6, which include detailed lessons you can teach to help students write beautiful and powerful fantasy stories

- Suggest mentor texts that will show students how to craft their fantasy stories.

- Show you examples of students’ fantasy writing, including the “worldbuilding” work they do before writing drafts

- Explain how you can modify the units and lessons to fit the needs of the students in your classroom

By teaching fantasy writing, you can reignite the spark of creativity in your students and increase their joy in writing. Imagine the possibilities!

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Supplements

This comprehensive guide brilliantly unlocks the magic of storytelling for young minds. From crafting the first idea of a fantasy story to illustrating magical worlds, the book serves as an essential tool for budding writers and artists. Its engaging lessons on character creation, plot development, and incorporating magic into narratives not only inspire creativity but also foster a love for writing and illustration. A must-have for educators and students alike.

The genre of fantasy has the power and potential to inspire young writers, engaging and inviting them into the world of storytelling by tapping into their vast imaginations and love of make-believe. Carl's book provides a navigable and welcome roadmap for teachers who want to offer students fantasy writing experiences, but need structure, guidance, and resources. Teachers will love the lessons, and students will love the portals into their own worlds and creations of fantasy.

Students will love Carl’s book for the opportunity to create their own rich worlds. My students thrived developing characters, maps, creatures, alliances, and conflicts. Carl’s book is a much-needed breath of fresh narrative air for both elementary writers and teachers.

I had the good fortune of hosting Carl several times over the past couple of years as he piloted this work in my classroom and was amazed at how much writing students were doing, the high levels of student engagement, and the elevated quality of their writing. This book is a powerful elixir that will vanquish disengagement and ignite a love of writing within some of your most reluctant writers. And it’s grab-and-go, with units, mini-lessons, mentor texts, charts, student samples, and more.

I was always fearful of teaching fantasy writing, but Carl Anderson has completely changed my views. Fantasy is now my favorite genre to teach, and my writers will agree. Children are eager to write fantasy stories and this book provides teachers with all the tools they’ll need to bring these units to life.

Teaching Fantasy Writing brims with strategies, lessons, mentor texts, and think-alouds designed to captivate and empower student writers. Reading this book is like having a mentor teacher to guide you through a genre that many teachers may not even consider yet is adored by so many students.

Behold, Carl’s magic key for teaching what our students crave: Fantasy writing. With effective, step-by-step lessons for multiple subgenres, you can follow the “Yellow Brick Road” or revise to fit the needs of your students—even learn to write and illustrate your fantasy story alongside them. Carl is my Merlin in all things Fantasy; let him become yours, too!

For too long, writing fantasy in grades K-6 school has been relegated to the fringes. This book is the perfectly blended concoction of scholarship, inspiration and practical resources that will allow fantasy to take its rightful place as a powerful driver of imagination, engagement, craft, and vocabulary growth. Teaching Fantasy Writing is the enchanted gift given by a magical creature (Carl) to a weary mage (you) in need of joy, light, and triumph. If you choose to accept it, be prepared for your instruction and students’ writing to transform in ways you could never imagine!

Preview this book

For instructors, select a purchasing option.

Fantasy with Fifth-Graders

Intro to Fantasy

Sarah LaBrie

In this lesson plan, former New York University Writers in the Schools Fellow Sarah LaBrie introduces fifth-graders to the world of writing fantasy. Her method includes group reading, writing, and brainstorming as ways to kick-start ideas before moving into vibrant, detailed writing that can combine our world with the fantastic.

Lesson Overview

Grade(s) Taught: 5th

Genre(s) Taught: Fantasy Fiction

Download: Fantasy with Fifth-Graders

Common Core State Standards: (Refer to English Language Arts Standards > Writing > Grade 5 )

- ELA-LITERACY.W.5.3.A Orient the reader by establishing a situation and introducing a narrator and/or characters; organize an event sequence that unfolds naturally.

- ELA-LITERACY.W.5.3.D Use concrete words and phrases and sensory details to convey experiences and events precisely.

- ELA-LITERACY.W.5.10 Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of discipline-specific tasks, purposes, and audiences.

Guiding Questions:

What is a fantasy protagonist? How can we use sensory perception to create a believable character? How can we combine character, and sensory perception to expand description of setting? How can we use a character’s wants, needs, desires, and emotions as they relate to a setting to start a story?

LESSON

Introduction: “Choosing a hero”: I read an early passage from a familiar fantasy novel, The Lightning Thief , that deals with a fantastical hero and his/her attempts to escape from a specific place. Together, we come up with a list of the different elements of a fantasy protagonist, using Percy Jackson—the main character in the book—as an example; e.g., ability to use magical tools, special qualities, a sense of being “chosen” for a quest, etc.

We talk about how we can understand a main character better if we understand his emotional and physical reactions to his surroundings. We also briefly discuss potential fantasy environments. Do fantasies have to take place in another world or can they take place in this world? Where did Percy Jackson’s story begin? How will you decide where to set your story?

Main Activity: With the participation of the class, I model the following prompt: Your hero wakes up in a mysterious place to discover that she is wearing a blindfold that cannot be removed. What could you put after the prompt “I see only darkness…” to have the hero put together sensory clues about that place using her five senses. Write what the students suggest on the board, and then discuss what place they think they’ve described.

I introduce the concept of a talisman, an object important to the protagonist’s life. I have some examples of talisman props ready to share, and have students brainstorm other objects we might use as talismans in our stories.

Now we transition into independent writing. Students begin with their own response to the first prompt, and move on to the connecting one: First, help your character devise a blind escape using a talisman. Then, discuss what your character’s choices tell us about the character.

Closing: Students share in small groups, with time left for feedback on other interpretations of what the characters’ choices could tell us about them.

Percy Jackson and the Olympians: The Lightning Thief , Rick Riordan Talisman props Lots of room to write on the board

Vocabulary:

Talisman, character, sensory perception, fantasy

Multi-Modal Approaches to Learning:

This lesson appeals to aural learners, hearing the model text read aloud; kinesthetic and visual learners, picturing a scenario using four of the senses that inform and allow the creation of a mental image; interpersonal learners, answering a prompt as a class and group brainstorming; and intrapersonal learners, with time dedicated to independent writing.

Related Posts

- International

- Schools directory

- Resources Jobs Schools directory News Search

KS3 Fantasy Writing Unit

Subject: English

Age range: 11-14

Resource type: Unit of work

Last updated

2 February 2024

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

5 - 6 week fantasy creative writing unit, suitable for KS3.

- Fully resourced with clearly labelled and ordered powerpoints, extracts and worksheets*

- Full scheme of work included; SoW has lesson by lesson breakdown of activities, links to KS3 learning objectives from the National Curriculum, indication of where British Values are met in the lessons, indication of ICT/Media opportunities in the lessons, homework suggestions and indication of assessment opportunities.

- Lessons are engaging, well-structured and last 50 minutes each

- Includes linked assessment task

- Lesson PowerPoints have clearly marked sections: Starter, LOs (Previous learning, what, how, why), Guided Practice, Independent Work, Plenary

- These lessons were used during Inspection 2023

I have used this with mixed ability Year 7 but the scheme is suitable for all KS3 and can be easily adapted for higher/lower ability as needed.

Please be aware that hyperlinks to resources on the SoW will need to be relinked, as these will not go to the correct place on your own computer/shared area when initially downloaded.

If there are any problems downloading the resources, please let me know and I will sort it out for you ASAP!

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

DOWNLOADED AN EMPTY FOLDER. TRIED REPORTING THE ISSUE BUT THE SCREEN WENT BLANK.

The resource should have downloaded as a ZIP folder - there are almost 30 files inside it. Please email me ASAP and I will send you the resources: [email protected]

Empty reply does not make any sense for the end user

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

- Benefits to Participating Communities

- Participating School Districts

- Evaluations and Results

- Recognition Accorded

- National Advisory Committee

- Establishing New Institutes

- Topical Index of Curriculum Units

- View Topical Index of Curriculum Units

- Search Curricular Resources

- View Volumes of Curriculum Units from National Seminars

- Find Curriculum Units Written in Seminars Led by Yale Faculty

- Find Curriculum Units Written by Teachers in National Seminars

- Browse Curriculum Units Developed in Teachers Institutes

- On Common Ground

- Reports and Evaluations

- Articles and Essays

- Documentation

- Video Programs

Have a suggestion to improve this page?

To leave a general comment about our Web site, please click here

Share this page with your network.

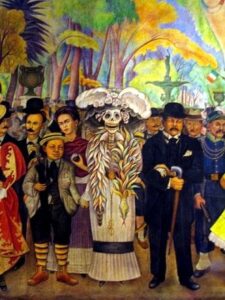

Fantasy Books: There's a Whole Other World Out There

What this unit will teach.

My favorite genre is fantasy. The idea that the magical can happen in the midst of the ordinary is fantastic. Fantasy really makes the phrase "Escape with a good book" meaningful. Our everyday world is at times quite predictable and mundane. Some of us dream of having magical powers or coming across a mythical beast. The supernatural is so very intriguing to me. I know that many students feel the same way. They eat up anything that has magic, dragons, wizards or talking beasts. Stories like that seem so real that sometimes the fantasy and the reality become intertwined and hard to separate. I once had a girl who was puzzled because she didn't realize that dragons didn't exist. I in no way want to encourage children to live in a world that is outside our realm and believe in the things that happen within a fantasy novel. However, I do enjoy seeing the excitement brewing within students when they are really into a fantasy novel. There's definitely a different passion for fantasy than there is for any other genre.

As a middle school sixth grade teacher I notice that the majority of my students prefer fantasy novels to most other genres. I have noticed the trend in fantasy take a huge upswing over the past decade or so. It's almost as if the other genres have taken a back seat and are waiting in the shadows for things to calm down. Since I see such resounding interest in fantasy I decided that I should write a curriculum unit focusing solely on that genre. If this is what interests our students, why not use that material to provide a teaching device. We've all had our moments of teaching a lesson only to look out and see the bored faces out in the crowd. If fantasy is what interests the students then perhaps that interest will be enough to keep our students focused for the Reading and English objectives we are required to teach.

I wish therefore to create a unit devoted purely to the genre of fantasy. We will look at fantasy in forms such as picture book and novel. If a student is resistant to fantasy, that might pose a challenge in teaching this unit. However, I believe that the teaching approach in this unit and the stories that will be taught will draw any student into an enjoyable experience with fantasy.

This unit will focus on reading and analyzing the genre of fantasy. There are some specific aspects of fantasy that make it a genre of its own. We will study these aspects and learn what makes this genre so engrossing. In addition to reading, we will do some writing. It is amazing how easy it is for kids to create the supernatural. My goal is to have pairs or small groups of students write an original piece of fantasy with illustrations—basically, to create a fantasy picture story book. This will come of course with coaching and reassurance. They have that creative spark in them, we all know that. But very often the spark cannot surface due to all the "school" that they are given. Hopefully the magical world of fantasy will intrigue the students enough to be free to write about it.

The practical purpose of this unit is the teaching of literary elements. We will incorporate as many literary devices as possible, such as plot, characterization, point of view, conflict, foreshadowing/flashback, tone/mood, and setting. We will look at where these devices appear in various texts. We will also concentrate on including them in the original fantasy stories we write.

For the short stories I intend to do teacher read alouds. For the novels I intend to do literature circles. Some of the stories I am intending to use would be novels such as Harry Potter, Chronicles of Narnia, Rabbit Hill, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, James and the Giant Peach, The Indian in the Cupboard, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, A Wrinkle in Time, The Lord of the Rings and Charlotte's Web . We will also incorporate some fantasy short stories such as Jumanji, Curious George, Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, The Tub People, The Velveteen Rabbit and The Rainbow Fish.

Introduction to Fantasy

What is fantasy? How can one identify a fantasy story? When we speak of just the word itself we are referring to an imagined dream or event. We also refer to the word when we are speaking of wishful thinking. When we refer to fantasy in the context of literature we are referring to stories that have certain definable elements that make the story unreal. There are many such elements. They vary from mythical beasts roaming an imagined world to natural settings in which animals take on human characteristics. There are recognizable conventions of fantasy, such as toys coming to life, tiny humans, articulate animals, imaginary worlds, magical powers, and time-warp tales. A story needs to possess only one of these features in order to be classified as fantasy. However, some great stories use a combination of fantasy elements. I tell my students simply this: a fantasy is any story in which at least one element cannot be found in our human world.

Why should we acknowledge this genre at all? Isn't it leading children into unreal dreams and causing confusion between what is real and what is not real? I don't think so. Just because a story contains animals that talk doesn't mean that the animals are not expressing the same emotions as fictional characters. Can't a child learn about love just as easily from Charlotte's Web as from Old Yeller ? In fact, it seems to me it takes more imagination and a more open mind to believe that Charlotte had feelings and could show love than it does to respond to the connection between a boy and his dog. It certainly takes an open mind to believe that there is a Middle-earth and that dwarfs, elves and humans can bond and protect one another. I believe that fantasy not only does not lead children astray and cause them confusion, but that it actually broadens their mind and causes them to think beyond what we consider to be the limits of reality.

What Fantasy Isn't

After saying what fantasy is, we should take a minute and look at what it isn't. Fantasy is not any of the following genres: realistic fiction, historical fiction, or science fiction. Let's look at each of these genres briefly.

Realistic fiction is a story in which all the action, characters and setting could happen, it just didn't. In other words, the characters act like you and me and they live in places where you and I could live. Many times the author has styled the character after someone he or she knows, but just made some minor changes. Realistic fiction has every quality of being true, except it isn't.

Historical fiction is a story that takes place in the past. In fact the setting of the story plays a major role in the action of the characters and the events that happen. The characters act and dress in the style and manner of real people of that time period. One distinction I make in defining historical fiction is that it can only be historical fiction if the setting of the story precedes the time when the story was written. In other words, a book that was written in 1950 about children in the 1950s does not become historical fiction in 2006. It will remain realistic fiction even though the setting and characters are now in the past.

Science Fiction: now here is where a distinction is truly necessary. Science fiction in some way involves a medical or technological advance that has not yet occurred, or a mode of advanced life that has not yet been discovered. But that is not to say that these things could not emerge in the future. We as humans are brilliantly coming up with new advances in medicine and surgical procedures. In the same realm we are also constantly coming up with advances in technology. If you had asked someone in 1930 if they thought there would be any way that one day everyone would not only have a telephone at home that can call anyone in the entire world, but also that virtually everyone would also have a cellular phone that had all the capabilities of a home phone, and more, and was something that could fit in the smallest of your jean pockets, they would have said it was impossible. That is what I mean by science fiction. It has not happened, but it could possibly happen.

Of course each of the above genres can be combined with one another to make various stories. What I wanted to point out, however, is that none of them can ever be combined with fantasy and still maintain its true character. Fantasy has this brilliant way of taking over the story line so that no other story line or elements of another genre can remain the central focus of the reader's attention.

Elements of Fantasy

We will start with the definition of fantasy and give some examples to the students. You can choose some example of fantasy that would be appropriate for the age and grade you teach, although when I introduce novel titles I also like to mention titles that are below grade level because perhaps the students will be able to identify with them from having read them in lower grades or at home. For example, I teach sixth grade so of course I mention titles like Harry Potter and Redwall. But I also mention titles like Charlotte's Web and Curious George.

When beginning this unit I will have my students take notes on fantasy motifs, but one could also provide a handout to them, especially since all of these motifs cannot be covered adequately in one class period. When we return to the lesson they can refer to their notes, and this will also be helpful when they write their fantasy picture story book at the end of this unit. Next we will discuss the elements of fantasy. There are seven basic motifs in fantasy: magic, otherworlds, universal themes, heroism, special character types, talking animals, and fantastic objects. Every fantasy story has some blend of the above elements. It's almost like a formula for writing fantasy. Students need to understand this formula and these elements in order to understand the basis of fantasy. Let's look at each of these elements separately.

Magic is the most basic element of fantasy, whether it's Harry Potter waving his wand or the Cheshire Cat's ability to disappear. In my opinion, magic is what draws a reader to fantasy. Magic is that in which charms, spells or rituals are used in order to produce a supernatural event. It's something that we humans are unable to perform, so we are intrigued by it. The following is a quote from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland when Alice first meets the Cheshire Cat.

"You'll see me there," said the Cat, and vanished. Alice was not much surprised at this, she was getting so well used to queer things happening. While she was still looking at the place where it had been, it suddenly appeared again. (105)… "and I wish you wouldn't keep appearing and vanishing so suddenly: you make one quite giddy!" "All right," said the Cat; and this time it vanished quite slowly, beginning with the end of the tail, and ending with the grin, which remained some time after the rest of it had gone. (106)

Otherworlds

Otherworlds are an imaginative creation by the author of a place that is nothing like earth. It is a completely imagined world where anything can happen and is only limited by the author's imagination. One thing I respect the most about fantasy writers is their ability to create from scratch an entirely imagined world where unreal things happen. The author has two choices when introducing an imaginary world to the reader. He or she can begin the book by locating all characters in this imagined world and never refer to what we know as the real world, as in Tolkien's Middle-earth. Another way for an author to introduce another world is to have the characters leave the world that we know and enter the new world, as in Lewis's Narnia. The characters can also have the ability to jump between two worlds.

Universal Themes

Universal themes are a must-have in a fantasy story. The most basic of these is good versus evil. There's always a good guy trying to fight for what is right against the powerful force of a bad guy. A great example of good vs. evil is A Wrinkle in Time. Other themes include love ( Pinocchio) , friendship ( Charlotte's Web) and perseverance in the face of danger ( Lord of the Rings) .

Heroism is something we all love. We love to see heroes save the day and become victorious over evil. Many times the heroes are ordinary people in difficult circumstances. They themselves don't know of their powers or abilities until they are called upon to perform heroic feats. It is that humble strength that we love to see. Some characters are guided by a larger, more powerful force—characters such as Frodo by Gandalf or Meg Murry by Mrs. Whatsit in A Wrinkle in Time. The following quote from A Wrinkle in Time exemplifies not only the idea that ordinary characters are called to do great things, but also that they always find the power within themselves that they had no idea was there.

"But I do understand…That is has to be me. It can't be anyone else." (195) And that was where IT made ITs fatal mistake, for as Meg said, automatically, "Mrs. Whatsit loves me; that's what she told me, that she loves me," suddenly she knew. She knew! Love. That was what she had that IT did not have. (207)

Special Character Types

Special character types are abundant in fantasies. Some examples are fairies, giants, ogres, dragons, witches, unicorns and centaurs. We love these characters because they are so different from what we find in our daily lives. However, a good author can shape the character in such a way that the reader has no problem believing that such a being could exist.

Talking Animals

The use of talking animals or anthropomorphism in fantasy stories can be used for several purposes. Sometimes the animals can talk to humans, as in James in the Giant Peach or The Chronicles of Narnia . Then sometimes the animals only talk amongst each other and are incapable of talking with humans, as in Charlotte's Web, Redwall or Rabbit Hill . The need and use for communication is prevalent in both types. Here we can also mention the use of talking toys, as in The Velveteen Rabbit or The Indian in the Cupboard.

Fantastic Objects

Fantastic objects help the characters perform their task. Many times these objects become almost a character in themselves. Where would Dorothy be without her slippers, Harry without his wand or Tinkerbelle without her dust? Many times characters need such an object to make themselves complete. The following quote from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone illustrates the idea that a hero needs an object and many times that object finds its way to the hero rather than vice versa.

Harry took the wand. He felt a sudden warmth in his fingers. He raised the wand above his head…and a stream of red and gold sparks shot from the end…Mr. Ollivander fixed Harry with his pale stare. "I remember every wand I've ever sold…It is very curious indeed that you should be destined for this wand when its brother-why, its brother gave you that scar.…The wand chooses the wizard, remember…I think we must expect great things from you, Mr. Potter….After all, He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named did great things- terrible, yes, but great" (85)

Each of these motifs makes fantasy the distinctive genre that it is. As you begin to introduce and use fantasy in your classroom it is important to teach these motifs and point out specific examples to the students.

Literature Circles for Elements of Fantasy

To review the lesson on elements of fantasy the class will be put into small groups. Each group will be given a fantasy picture book. For this unit I will suggest the following books: Curious George, The Rainbow Fish, The Tub People, Jumanji , The Velveteen Rabbit and Sylvester and the Magic Pebble. Each group will read their respective picture book and look for the elements of fantasy we have just learned. I suggest that the group fill out a report answering first the question of "Why is this a fantasy story?" Then they will fill in the information about magic, otherworlds, universal theme, heroism, special character types, talking animals, and fantastic objects. If any of these motifs do not apply to the story, that should be noted. Afterwards a short presentation to the class should be given. The presentation should include a short summary of the book as well as provide information about the specific aspects of the story that relate to fantasy.

Literary Elements

We all know that literary elements are the basis for teaching reading. I am specifically referring to plot, characterization, point of view, conflict, foreshadowing/flashback, tone/mood, and setting. For this unit we will incorporate these elements into the fantasy stories we are using. There are many more literary elements, especially when teaching high school, such as irony, figurative language, allegory, etc. I have chosen just these seven for this unit. You can remove any of these you wish when teaching this unit in your classroom or add more that you wish to cover also.

Plot is the sequence of events that applies to all fiction stories. It begins with Beginning Action. This is where the setting and characters are set up and introduced. Next is the Initiating Event. This is the event that is the catalyst to the entire story. It begins the conflict. Then we see the Rising Action. This is the bulk of the story line. All the events leading to the Climax are found in the Rising Action. Then we come to the Climax. Here the conflict is resolved and all the tenseness of the story comes to a peak. Next is the Falling Action. After the Climax is revealed the Falling Action begins to wrap up the story and loose ends are tied up. Finally there is the Resolution. This is the conclusion of the action and the end of the story.

Most stories used in the classroom are fiction stories that have a plot or story line. It's important to illustrate this to the students and make the differentiation between elements that belong to fiction and that those that belong to non-fiction. When I introduce plot for the first time I use a picture book, for reasons of brevity. We make a plot outline together as a class so the students can see each and every part of the story. Since this unit is focusing on fantasy, I would recommend using Sylvester and the Magic Pebble or The Velveteen Rabbit. As you begin to use novels, then you can presume their understanding of "plot" in the discussion.

Characterization

Major characters are the basis for the story. They are mentioned the most and have the most influence on the outcome of the story. As major characters you have the protagonist and the antagonist. The protagonist is essentially the good guy and the main character. The antagonist is the character or force that is against the protagonist, essentially the bad guy. Major characters are always round or dynamic. This means that they change and grow as the story moves along.

Minor characters are there to support the major characters. They are not necessarily essential to the story; however they do provide support and background. The loss of a minor character does not necessarily change the outcome of the story. Minor characters are usually flat or static. This means that they do not change through the course of the story. They lack depth in character.

In A Wrinkle in Time , for example, Meg Murry would be the major character and protagonist. We can see her transformation from the beginning of the story to the end. She has depth and the story most certainly needs her to continue on. The antagonist would be IT. IT is essential to the story and provides the opposing force to Meg. Minor characters would be Meg's mother and in some respects her father, as her father is important to the story, but does not change as a result of the action of the story.

Point of View

Point of view is the view from which the story is told. There is first person, which is when the story is told through the eyes of one character who is the narrator. That character can reveal his or her thoughts but cannot go into the mind of any other character. The word "I" is frequently used in first person.

Third person has three different aspects. First there is third person objective. We do not know the thoughts of any characters, and only the action and conversation is revealed to the reader through the narrator. Then there is third person limited. This means that the narrator is an outsider who can see into the mind of only one character. The Indian in the Cupboard is told through the viewpoint of Omri, but he is not the narrator. Finally there is third person omniscient, in which the narrator has access to the minds of all characters. All thoughts and actions of the characters are revealed, and sometimes even the thoughts of the author are revealed, thoughts that none of the characters are aware of. The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe is an example of this point of view. We are able to follow the thoughts of each of the characters, especially Lucy and Edmund.

Conflict is the essence of the plot. It is the major problem that the story line is trying to resolve. There are four types of conflict which will be discussed below.

Man vs. man is where the conflict involves one character against another. In James and the Giant Peach James has conflict with his two aunts. They are despicable and wholly negligent towards him. In The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe we see a conflict between Aslan and the White Witch that resembles a man vs. man conflict. However, if we look at the story in a broader sense and see Aslan as God, then it becomes a man vs. society conflict. Man vs. self is a conflict within a character and his or her thoughts. In many parts of Harry Potter we find Harry struggling with himself. He is constantly balancing the boy he has always been with the newfound wizard he is becoming. Man vs. society is a struggle between a character's thoughts or action and what is expected of him or her in the society in which he or she lives. Pinocchio is a good example of this conflict because he always finds himself going against what society expects of him. Finally there is man vs. nature where the character struggles against natural forces. A Wrinkle in Time could be an example of this—if in fact we view IT as natural.

Foreshadowing/ Flashback

Foreshadowing is a hint at what will happen later in the story. Foreshadowings are not always recognized until later in the story when the reader learns something and realizes that a hint of it was given earlier. But in most cases foreshadowing is recognized, and raises the interest of the reader through suspense and encourages them to continue reading.

Flashback is a remembering of an event that happened previously. Sometimes the event was already revealed in the story. However, sometimes a flashback is about an event that was not revealed to the reader and fills in the plot gaps the reader may have had.

Tone is the way in which the author expresses his or her attitude toward a subject. This is a very difficult literary element to teach. The easiest tone to recognize would be humor. However, the author also could be feeling bitterness, joy, resentment, seriousness, pessimism or optimism. In James and the Giant Peach it seems the author uses humor to explain various situations. He uses humor to explain the deaths of Aunt Sponge and Aunt Spiker. He also makes a humorous situation when he introduces the Cloud-Men making hail, snow and rainbows.

Mood is what the reader feels while reading. It is the atmosphere created by the piece of writing. These feelings are achieved through the use of characters, setting, language and images. A good writer can evoke a strong mood within the reader that affects the way a story is read. Pinocchio gives us a constant feeling of frustration. We cannot understand why Pinocchio won't do the right thing. A Wrinkle in Time gives us a feeling of mystery. We are intrigued by this adventure Meg is having and also a little confused by it.

Setting is the place and time in which a story happens. The place can be as broad as Asia or as specific as a child's closet. The setting can also shift as the story moves along. Time is when the story is happening. Again, it can be as broad as the Civil War or as specific as 3 PM. The setting is usually revealed early in the story. Sometimes a setting is simply a backdrop to the story and is just there. Other times the setting may act as an influence upon the action of the story.

The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe is set in two places, Narnia and the professor's house in the English countryside, the latter being the non-fantasy world. The time period is World War II, which is significant in that it gives the reason why the children must leave home. Pinocchio is set in Italy in the late 1800s. The background of Italy does affect some of the dialogue and language, but overall it is not significant. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland obviously takes place in Wonderland. This non-existent land is the basis and cause for all the lunacy that appears in the novel. Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry is one of the settings for Harry Potter , the other being the English muggle house of the Dursleys. Of course none of the story could take place without Hogwarts because that is where Harry meets his best friends and his enemy Voldemort. The major and significant setting for James and the Giant Peach is the peach, which travels from London to New York City. All the adventure takes place inside the giant peach. Of course the magical setting of The Lord of the Rings is Middle-earth. This setting is significant because only a place like this could be the home for the hobbits, the elves, the dwarfs, the orcs, and the like.

Literature Circles for Literary Elements

After the literary elements have been taught, the students will again go back to the literature circles. They will be given the same book as before, but this time they will be looking for the literary elements previously discussed. Again, a report will be made providing the information for that book. Another short presentation to the class will be given relaying the information about the literary elements found in the story.

Creating A Fantasy Picture Story Book

After we have studied the elements of fantasy and read some fantasy stories, the students will write their own fantasy story. This will be done in partners or groups. The final product will be an illustrated fantasy story that contains one or more of the elements we learned at the beginning of this unit.

Students will decide what type of fantasy they would be interested in writing. Will it be one with mythical creatures, one where humans have magical powers or one where animals are like humans? They must decide if the imaginary world is the only world in the story or if the characters move from the human world into the imaginary world. They need to choose a main character, whether it be male, female or animal. What do they want this character to do? What challenges will this character be faced with? What, if any, powers does this character have and what is the fantastic object that they will use? What kind of villain will the book have and what will its powers be?

The students should have about a week to write and illustrate this story. Details like the length, type of binding, etc. can be left to the teacher. We all have students of different ages and abilities, so this unit can be adapted to your classroom needs. A good way to keep the students focused is to provide them a checklist of things that need to be covered in the story. For example, each of the elements of fantasy needs to be checked as being used or not used. Also, a list of the literary elements needs to be addressed and noted where it occurs in the story. So let's say the rough draft of the story is turned in and the paragraphs or pages are numbered. On the checklist the students would note where in the story, page or paragraph, it provides the setting or the universal theme is revealed. Also they would note where the use of point of view is revealed and where the conflict is noted. It would be a way for the teacher to check that the students are understanding the assignment in incorporating the elements learned properly. Also this is a good way to keep the students focused on using and applying the knowledge they gained from the lesson. These books will definitely be something to display and something the students will be proud of. Be sure to expose the students to many fantasy picture books in addition to those used for the literature circle. It would be good if they could refer to some of the books as they are working to get ideas. This is especially helpful for the struggling readers who may not know where to begin when writing an original story.

Extension Activity

I would suggest creating extended literature circles in which the groups read a fantasy novel. I have suggested and referenced many in this unit. I would, however, enforce that a student could not be in a literature circle for a novel he or she has already read. The purpose of the literature circles would be to expose the students to new novels as well as provide practice for them in identifying all the fantasy and literary elements learned in this unit.

Writing this unit was very exciting for me. That old saying "like a kid in a candy store" definitely applied to me as I was researching for this unit. I just really love fantasy and I was ecstatic to be able to write a curriculum unit that taught the reading skills I need to teach but also used stories that I love to read. I know many of my students love fantasy as much as I do. Hopefully by incorporating literature that they are interested in they will be more apt to learn the concepts presented.

As with any curriculum outline, you can modify for the needs of your class. I tried to reference several different fantasy books at varying reading levels so teachers could adapt to their classroom. You, of course, may have some favorite stories that were not mentioned in this unit. I'm sure that by the time I teach this unit a year or two, I will be using some new stories. That's the great thing about literature; there are great, great classics out there that need not be overlooked. Then too, new stories come out every year, and some of those go on to become classics. My hope is that this unit will be versatile enough to last in your classroom from year to year.

Lesson Plans

Lesson plan 1.

Objective: Students will understand the elements of fantasy.

Materials: Any variety of fantasy novels and picture books that is appropriate for your class level. I have referenced several previously in this unit. Also, a handout or report to be completed by the literature circle group concerning the various fantasy motifs.

Activities: The teacher will present the seven motifs of fantasy, being sure to read examples from various literature sources. Students will either be given a handout of the motifs and definitions or take notes on their own. After all seven motifs have been presented the students will form literature circles and will read a selected fantasy picture story book. Each group will complete a short report on the story and what motifs were used, citing specific examples. Each group will present to the class.

Lesson Plan 2

Objective: Students will understand several literary elements.

Materials: Notes on literary elements, a variety of fantasy picture story books. Optional: a handout containing this information for students. Also, a handout or report to be completed by the literature circle group concerning the various literary elements.

Activities: The teacher will present the information about the literary elements, being sure to give examples where possible. Students will either take notes on the lecture or will be given a handout to review. After all literary elements have been discussed, students will return to their literature circles and re-read their picture book looking for examples of each of the literary elements presented. Each group will complete a short report on their findings citing specific examples where possible.

Lesson Plan 3

Objective: Students will create an original fantasy picture story book.

Materials: Various fantasy picture books to be used as references, white drawing paper, markers or crayons, some type of binding chosen by the teacher, checklist of requirements for the story.

Activities: Students choose partners or small groups with which to work. Each group will create an original fantasy picture story book that contains illustrations. The students must include several of the motifs of fantasy as well as several of the literary devices. Each group will complete a checklist provided by the teacher of what is to be included. Students will complete the checklist citing examples from their story. After all stories have been created each group will read their original picture story book to the class.

Comments (7)

Send us your comment

Creative Writing Unit for High School Students

My creative writing unit for high school students allows for adaptations and for fun! With plenty of creative writing activities, you’ll have flexibility.

If you are looking for a creative writing unit, I have ideas for you. When I taught middle school, I sprinkled such activities throughout the school year. As a high school teacher, though, I taught an entire creative writing course. With no textbook and very little established activities, I largely worked from a blank slate.

Which. . . turned out well. I love teaching creative writing!

ELA Specific Classes

Older students often can choose electives for their ELA classes, and Creative Writing is a popular class. I’ve condensed my ideas into one post, so I organized the ideas by creative nonfiction and fiction writing and added pictures to organize this information for you.

EDIT: This post about my creative writing unit for high school writers has exploded and is about three times as long as a normal blog post. If you’d like to skip around to get inspiration for teaching creative writing, you can use the pictures and headings as guidance.

ANOTHER NOTE: I attempted to outline the days I spend on each topic, but several factors went into my estimates. First, each class differs in what they enjoy and what they dislike. If a class dislikes a specific topic, we will wrap it up and move on. If a class has fun with an assignment or needs more time to work, the days might vary.

What are the key elements of a creative writing unit?

Key elements of a creative writing unit include introducing different writing genres, teaching basic writing techniques, encouraging imagination and creativity, providing writing prompts and exercises, offering constructive feedback and revision opportunities, and fostering a supportive writing community.

How can we organize such activities?

Starting with creative nonfiction has worked for my classes, small pieces like paragraphs. I believe the success is because young writers can write what they know about. Then we can switch to fiction for the second quarter. Again, the days spent on each assignment varies, and I honestly do not stress about creative nonfiction being nine weeks and fiction being nine weeks.

All of the material listed below is in my newly updated Creative Writing Bundle . The pieces are sold separately, but that creative writing unit includes bonus material and a discount.

Ok, settle in! Here are my ideas about teaching creative writing with high school students.

First Week of School for a Creative Writing Unit

The first day of school , we complete activities that build awareness into the classroom environment about “creativity.” Do not shy away from setting a foundation of support and understanding as you engage with young writers. During my first creative writing classes, I neglected to spend time establishing expectations and community. The following semester, the time invested early paid off with engaged students later.

Those first days, we also discuss:

- Published vs. private writing. I tell writers they may share whatever they like with me and the class. As a community of writers, we will share with each other. Most of our writing will be public, but some will be private.

- A community of writers. Writing and sharing ideas requires maturity and acceptance. Not everyone will agree is largely my motto (about negotiables, not human rights), and I stress with students that they may read and provide feedback with topics in which they do not agree.

- Routines. Writers write. That sentence might sound silly, but some people believe that humans are born with a skill to write or they are not. Writing well takes practice. The practice can be short and unconnected to a larger product. I typically begin each week with a quick writing prompt , and we share our responses, which of course, builds that community of writers.

Whatever you are teaching—a creative writing unit or a creative writing class—spend some time establishing your expectations and goals with your students. Laying a foundation is never a waste of time! In fact, I believe so much in the power of the first week of a creative writing class that I have a blog post devoted to the concept.

Time: 2-3 days

First weeks: creative nonfiction

Creative nonfiction seems to be the genre of our time. Memoirs, essays, and hermit-crab essays flood bookstores and journals.

When students read captions on social media, profiles of their favorite artists, or long Threads, they are reading creative nonfiction. Not only should students be able to dissect this form of writing, but they should also be able to write in our society’s preferred genre.

Below, I’ve outlined creative nonfiction activities that work with teenagers.

Nonfiction Narrative Writing

Writing narratives (and meeting those standards) are trickier with older students. As a teacher, I struggle: Students will often tell me deep, meaningful, and personal parts of their lives, and I am supposed to grade those writings!

When students write a narrative , I address this situation immediately. Share with writers that their narrative ideas are strong (I believe that to be the truth!), and that in no way are we grading their ideas. Rather, we want their excellent narratives to be communicated in the best light; therefore, we will provide guidance about the structures of narrative writing.

The topic for a nonfiction narrative varies. Often, students write about themselves as learners or as community members. Framing students in a positive way allows them to explore their strengths in life and to build confidence as writers.

Time: 7-9 days

Object Essay

An object essay might sound like a “blah” type of assignment, but the simplicity allows students to push past their normal experiences. An object essay is simple, so they can experiment with their writing.

What object? I have assigned this essay several ways. For instance, I have brought in a very plain object (like a rock) and had students explain it. I like this approach because students can work together to discover the best descriptions.

Another way, my preferred way, is to allow students to choose the object. Students write about a coffee cup, water bottle, car keys, or bus pass. When students choose, the essays are richer with meaning.

Neither approach disappoints me, though! With a plain object, students must stretch themselves to be creative. Judge what your class needs and get students writing!

Time: 3-4 days

How-to Paper

No, not a “how to make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich” paper. A fun and meaningful how-to paper can encourage classes as they see themselves as experts.

What I like about a how-to paper is students get to be the expert in their paper. Finding a used vehicle to buy? Shopping for a formal event? Saving money? Cleaning a closet? Selling at consignment stores? Each writer has an area in which they shine, and a how-to paper allows them to share their knowledge with others. They write about “behind the scenes” or little known secrets.

Of all the creative writing activities, I assign the how-to paper early. It builds confidence in young writers.

Time: 5 days

Sell this Apple

Why an apple? When I wanted students to creatively sell something, I searched for something they could all have in common but sell in different ways. I wanted classes to have one object but to witness the multiple approaches for advertising. Apples (which I could also afford to bring to class) fit nicely.

What do students sell when they “sell an apple”?

- Dips for apples.

- Apples for preschool snacks.

- Charcuterie apple boards.

- Apple crisp.

- Red and green apple rainbows.

Basically, students can create a marketing plan for multiple age groups and other demographics. For instance, they can write a blog post about safety in cutting pieces for young children (and complete some research in the process). They can then “promote” a local apple orchard or fruit stand.

Another advertisement is an apple pie recipe for a Thanksgiving brochure for a supermarket.

When I gave students something simple, like an apple, they ran with the idea. Then, we can share our ideas for selling apples.

A profile is difficult to write, so this assignment is normally my last assignment of the quarter. Before we switch to writing fiction, we apply all our concepts learned to writing a profile.

Profiles are more than summaries of the person. Writers must take an angle and articulate the person’s traits utilizing Showing vs. Telling. Of all creative writing assignments, the profile, might be the most difficult. I place it in the middle of the semester so that writers understand our goals in class but are not tired from the end of the semester.

Time: 10-12 days

Final weeks: fiction

Fantasy, historical fiction, mystery, romance: Students consume a variety of fiction via books, movies, and shows. Fictional creative writing activities invite young writers into worlds they already consume.

Below, I’ve outlined some that work with teenagers.

Alternative Point-of-View

Grab some googly eyes or some construction paper and send students loose. (A few guidelines help. Should students remove the googly eyes from the principal’s office door?) Have them adhere the eyes to an inanimate object to make a “being” who learns a lesson. They should snap a picture and write a quick story about the learned lesson.

What type of lesson? Perhaps an apple with a bruise learns that it still has value and is loved with blemishes. Maybe a fire extinguisher realizes that its purpose is important even if it isn’t fancy.

Honestly, the creativity with the googly eyes adhered to inanimate objects is so simple, but it always is my favorite event of the semester. I officially call it the “ alternative point-of-view ” activity, but “googly eyes” is how my writers remember it.

Time: 2 days

Create a Superhero with a Template

A superhero does not need to wear a cape or fancy shoes. Rather, in this creative writing activity, students build a superhero from a normal individual. When I created the activity, I envisioned students writing about a librarian or volunteer, but students often write about a grandparent (adorable).

Since students enjoy graphic novels, I wanted students to experience making a graphic novel. The colorful sheets allow students to add their ideas and words to pages that fit their messages.

After students create a comic book, they will also write a brief marketing campaign for a target audience. Learning about who would buy their graphic novel typically leads them to parents and librarians which should lead students to discover the importance of reading. The advertising campaign additionally serves as a reflective component for the initial activity.

Product Review

Product reviews and question/answer sections are a genre all their own. SO! Have students write reviews and questions/answers for goofy products . Students will find a product and write several reviews and questions/answers.

This quick activity lends itself to extension activities. Once, a teacher emailed me and said her school bought some of the goofy products for a sort of “sharing” day with the school. Since students have access to pictures of the item, you can make a “catalog” for the class out of a Canva presentation and share it with them and your colleagues.

Here are a few examples:

- Banana slicer .

- Horse head .

- Wolf shirt.

Aside from the alternative point-of-view activity, the product reviews remain my personal favorite part of a creative writing unit. Writers find random products and write goofy workups that they share with the class.

Time: 3 days

Character Creation

Creating a well-rounded and interesting character requires prep work. The brainstorming part of the writing process, the pre-writing? We spend lots of time in that area as we create fleshed out characters.

I like to start with a multiple-choice activity. We begin my imagining the main character. Next, students take a “quiz” as the character. How does the character eat? What sort of movies does the character enjoy? hate? After the multiple-choice activity, they can derive what those pieces explain about their characters. Finally, they can begin to brainstorm how those pieces will develop in their story.

Flash Fiction

Flash fiction is a simple, short story. Writers might cheer when they hear I expect a 300-word story, but often, they discover it is a challenging assignment from class. A large part of a creative writing unit is giving students a variety of lengths so they can practice their skills under different circumstances.

Historical Fiction

Historical fiction is a popular genre, and classes are familiar with many popular historical fiction books. I find it helpful to have several books displayed to inspire students. Additionally, I read from the books to demonstrate dialogue, pacing, theme, and more.

Since my historical fiction activity takes at least two weeks to accomplish, we work on that tough standard for narrative writing. To that end, these activities target the hardest components:

- Pacing within a narrative.

- Developing a theme .

- Building imagery .

- Creating external conflicts in a story.

- Establishing a setting .

First, I used pictures to inspire students, to get them brainstorming. Second, I created those activities to solve a problem that all writers (no matter the age!) have: Telling vs. Showing. I found that my writers would add dialogue that was heavy on explanation, too “world building” for their narrative. The story sounded forced, so I took a step back with them and introduced mini-activities for practicing those skills.

Third, the above creative writing activities can EASILY be assignments independently for short and fun assignments. I teach them with historical fiction because that activity is at the end of the semester when my expectations are higher, and because students enjoy writing historical fiction so they are invested.

But! You can easily add them to another narrative activity.

Time: 10-12 days

A clean tabloid! Tabloids are largely replaced by online social sharing creators, so they are fun to review with students. Students might not be familiar with tabloids at the grocery store checkout, but they are familiar with catchy headlines. They will be completely ready to write a tabloid !

To ensure a clean tabloid, I ask students to write about a children’s show, something scandalous happening from a cartoon. The results are hysterical.

Time: 4 days

Children’s Book

I have two introductory activities for the children’s book. One, students answer questions about a mentor text (another children’s book). Two, students evaluate the language of a specific book to start them in their brainstorming.

My students write their children’s book as a final activity in class as it requires all the elements of creative writing. When a school requires me to give a final exam, students write a reflection piece on their children’s books. If you are looking for a finale for your creative writing unit, a children’s book is a satisfying ending as students have a memorable piece.

Time 10-12 weeks

Final note on creative writing activities and bundle

I intended for this post to inspire you and give you ideas for teaching either a creative writing unit or a creative writing class in ELA. My first time through teaching creative writing, I worried that my lessons would flop and that students would not find their groove with me. I found success, but with modifications, I formed a cohesive semester.

The first time through, I did not frontload information and expectations. (Spending time at the start of class is my biggest message! Please establish groundwork with students!) I also did not provide concrete enough guidelines so students understood the differences between the assignments. After a few semesters, I developed my creative writing unit . With a variety of activities and an appropriate amount of structure, I found success, and I hope you do too.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive updates about new blog posts, freebies, and teaching resources!

Marketing Permissions We will send you emails, but we will never sell your address.

You can change your mind at any time by clicking the unsubscribe link in the footer of any email you receive from us, or by contacting us at [email protected] . We will treat your information with respect. For more information about our privacy practices please visit our website. By clicking below, you agree that we may process your information in accordance with these terms.

We use Mailchimp as our marketing platform. By clicking below to subscribe, you acknowledge that your information will be transferred to Mailchimp for processing. Learn more about Mailchimp’s privacy practices here.

*This post contains affiliate links. You can read my complete disclosures .

creative writing creative writing activities

Terrific Teaching Tactics

Make Learning Fun

The Best Mentor Texts For Teaching Fictional Narratives

Adding mentor texts to your writing curriculum can be a huge plus for your students! Read on to see my list of the 12 best mentor texts for teaching fictional narratives to 3rd-grade students.

Why Use Mentor Texts While Teaching Fictional Narratives?

First, let’s acknowledge the importance of using mentor texts when teaching writing. The simple truth is that WE know what we expect our students to do, but our students have no idea! Students must be exposed to examples of the writing genre we teach.

Mentor texts aren’t just great for exposing students to the genre; they are also powerful for explicitly teaching the structure and features. For example, we can show examples of characterization, setting, problems, and solutions. We can offer an author’s use of dialogue or linking words. Overall, mentor texts can be really powerful.

Let’s dive into my recommendations! FYI, I recommend these books in my third-grade fictional narratives writing unit (which you can check out here ).

Let’s look at the best mentor texts for teaching fictional narratives.

Robo-Sauce By Adam Rubin

Intrigue your students with a book about robots that is hilarious and awe-inspiring! It has everything they want in a story but will still show them key pieces of a fictional narrative piece. Kiddos just want to run free and have no rules, and the characters in this book run wild and turn into robots with laser eyes and supercomputer brains!

Teaching Idea: This book lends itself to fictional narratives because the whole story stems from the imagination. Give your students an open-ended prompt to encourage them to continue the story or share about them turning into a robot.

You can check out the storybook here .

Where the Wild Things Are By Maurice Sendak

I am sure you are familiar with this classic story of a child’s imagination gone wild. He is mad at his mother and imagines a world where he doesn’t have to have any rules and can do whatever he wants. He rules over the wild things but soon realizes he misses his mom. A warm supper is waiting for him when he returns from his voyage and makes him realize he needs his mother more than he thought.

Teaching Idea: I use this book during the second lesson of my fictional narrative writing curriculum , where I share with the children how to decide what to write about.

Check out the book here .

The Day I Lost My Superpowers By Michael Escoffier

Join a little girl on her daily adventures; on one particular day, she discovers her superpowers! She is delighted and wants to use them all the time. To her dismay, they fail her. She soon discovers that her mother has superpowers too. Good thing mom is there to save the day! The little girl and the mother share a special bond now.

Teaching Idea: Encourage your students to write about the superpower they wish they had.

You will find the book here .

A Bad Case Of The Stripes By David Shannon

Camilla Cream wants to fit in with all the kids at school, so she doesn’t eat lima beans anymore, even though they are her favorite! She is struggling to be true to herself and puts a lot of pressure on herself. Camilla finds herself coming down with a bad case of the stripes! Your students will be captivated to find out what happens to young Camilla.

Teaching Idea: Teach children about characters and their feelings. A fictional narrative must have characters, and the story is much better if they show emotions and feelings. Have children create a character that feels large emotions.

Get A Bad Case of the Stripes here .

Cloudy With A Chance Of Meatballs By Judi Barrett

This book is a wonderful example of a fictional narrative! Food falling from the sky for each meal, but soon the food gets a mind of its own and becomes large and dangerous. Just think of being able to order your meal, and it falls already prepared at your doorstep or not even having to prepare a meal!

Teaching Idea: Kids love to eat, and they will love to imagine a day’s worth of meals falling from the sky. I love this story since it leads children to imagine very easily; there is no right or wrong answer for this prompt idea. This picture book is also great for teaching about setting.

Grab the book here .

The Panda Problem By Deborah Underwood

This is the perfect book to share about the parts of a story; it is full of problems, a climax, a silly character, and a fun setting. The panda wants to make a story, but he doesn’t have a problem, so he decides to be the problem! He is ornery and creates mischief everywhere he goes! It makes for a great story!

Teaching Idea: The panda cause mayhem for a day…don’t you think your students will want to imagine a day of freedom and no rules? The perfect fictional narrative writing prompt for reluctant writers. This storybook is ideal for teaching about problems in narrative writing.

Click here to see the book.

Giraffes Can’t Dance By Giles Andreae

Teach children about accepting their unique talents while also showing students a good example of a fictional narrative. This book has all the features you want to teach about while also being silly and holding their attention. Gerald, the giraffe, can’t dance no matter how much he practices or tries. He just can’t until he finds a new tune and some courage!

Teaching Idea: Share a problem that all students can write about to create a solution. Make it a problem that doesn’t have an obvious solution, so students have to use their imagination to write something.

Here is the book link.

The Gruffalo By Julia Donaldson

Have you ever seen a gruffalo? Me neither! This book is so fun and will have your children laughing while imagining a walk in the woods on a search for one. Join the little mouse as it walks through the woods, meeting all kinds of creatures that want to eat it for a snack. It goes deeper into the woods, and you will have to read it to find out what he finds.

Teaching Idea: Read part of the story and have the students finish the rest. This mentor text is ideal for teaching story arcs.

Grab the story here .

Creepy Carrots! By Aaron Reynolds

Jasper Rabbit loves carrots! He especially likes the ones from a particular garden. One day, he starts to think that the carrots are following him. Are they? He really isn’t sure, but he is scared!

Teaching Idea: This is the perfect book to teach about adding suspense to a fictional narrative.

Check out Creepy Carrots! here .

Harold And The Purple Crayon By Crockett Johnson