The Philippines economy in 2024: Stronger for longer?

The Philippines ended 2023 on a high note, being the fastest growing economy across Southeast Asia with a growth rate of 5.6 percent—just shy of the government's target of 6.0 to 7.0 percent. 1 “National accounts,” Philippine Statistics Authority, January 31, 2024; "Philippine economic updates,” Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, November 16, 2023. Should projections hold, the Philippines is expected to, once again, show significant growth in 2024, demonstrating its resilience despite various global economic pressures (Exhibit 1). 2 “Economic forecast 2024,” International Monetary Fund, November 1, 2023; McKinsey analysis.

The growth in the Philippine economy in 2023 was driven by a resumption in commercial activities, public infrastructure spending, and growth in digital financial services. Most sectors grew, with transportation and storage (13 percent), construction (9 percent), and financial services (9 percent), performing the best (Exhibit 2). 3 “National accounts,” Philippine Statistics Authority, January 31, 2024. While the country's trade deficit narrowed in 2023, it remains elevated at $52 billion due to slowing global demand and geopolitical uncertainties. 4 “Highlights of the Philippine export and import statistics,” Philippine Statistics Authority, January 28, 2024. Looking ahead to 2024, the current economic forecast for the Philippines projects a GDP growth of between 5 and 6 percent.

Inflation rates are expected to temper between 3.2 and 3.6 percent in 2024 after ending 2023 at 6.0 percent, above the 2.0 to 4.0 percent target range set by the government. 5 “Nomura downgrades Philippine 2024 growth forecast,” Nomura, September 11, 2023; “IMF raises Philippine growth rate forecast,” International Monetary Fund, July 16, 2023.

For the purposes of this article, most of the statistics used for our analysis have come from a common thread of sources. These include the Central Bank of the Philippines (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas); the Department of Energy Philippines; the IT and Business Process Association of the Philippines (IBPAP); and the Philippines Statistics Authority.

The state of the Philippine economy across seven major sectors and themes

In the article, we explore the 2024 outlook for seven key sectors and themes, what may affect each of them in the coming year, and what could potentially unlock continued growth.

Financial services

The recovery of the financial services sector appears on track as year-on-year growth rates stabilize. 6 Philippines Statistics Authority, November 2023; McKinsey in partnership with Oxford Economics, November 2023. In 2024, this sector will likely continue to grow, though at a slower pace of about 5 percent.

Financial inclusion and digitalization are contributing to growth in this sector in 2024, even if new challenges emerge. Various factors are expected to impact this sector:

- Inclusive finance: Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas continues to invest in financial inclusion initiatives. For example, basic deposit accounts (BDAs) reached $22 million in 2023 and banking penetration improved, with the proportion of adults with formal bank accounts increasing from 29 percent in 2019 to 56 percent in 2021. 7 “Financial inclusion dashboard: First quarter 2023,” Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, February 6, 2024.

- Digital adoption: Digital channels are expected to continue to grow, with data showing that 60 percent of adults who have a mobile phone and internet access have done a digital financial transaction. 8 “Financial inclusion dashboard: First quarter 2023,” Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, February 6, 2024. Businesses in this sector, however, will need to remain vigilant in navigating cybersecurity and fraud risks.

- Unsecured lending growth: Growth in unsecured lending is expected to continue, but at a slower pace than the past two to three years. For example, unsecured retail lending for the banking system alone grew by 27 percent annually from 2020 to 2022. 9 “Loan accounts: As of first quarter 2023,” Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, February 6, 2024; "Global banking pools,” McKinsey, November 2023. Businesses in this field are, however, expected to recalibrate their risk profiling models as segments with high nonperforming loans emerge.

- High interest rates: Key interest rates are expected to decline in the second half of 2024, creating more accommodating borrowing conditions that could boost wholesale and corporate loans.

Supportive frameworks have a pivotal role to play in unlocking growth in this sector to meet the ever-increasing demand from the financially underserved. For example, financial literacy programs and easier-to-access accounts—such as BDAs—are some measures that can help widen market access to financial services. Continued efforts are being made to build an open finance framework that could serve the needs of the unbanked population, as well as a unified credit scoring mechanism to increase the ability of historically under-financed segments, such as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), to access formal credit. 10 “BSP launches credit scoring model,” Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, April 26, 2023.

Energy and Power

The outlook for the energy sector seems positive, with the potential to grow by 7 percent in 2024 as the country focuses on renewable energy generation. 11 McKinsey analysis based on input from industry experts. Currently, stakeholders are focused on increasing energy security, particularly on importing liquefied natural gas (LNG) to meet power plants’ requirements as production in one of the country’s main sources of natural gas, the Malampaya gas field, declines. 12 Myrna M. Velasco, “Malampaya gas field prod’n declines steeply in 2021,” Manila Bulletin , July 9, 2022. High global inflation and the fact that the Philippines is a net fuel importer are impacting electricity prices and the build-out of planned renewable energy projects. Recent regulatory moves to remove foreign ownership limits on exploration, development, and utilization of renewable energy resources could possibly accelerate growth in the country’s energy and power sector. 13 “RA 11659,” Department of Energy Philippines, June 8, 2023.

Gas, renewables, and transmission are potential growth drivers for the sector. Upgrading power grids so that they become more flexible and better able to cope with the intermittent electricity supply that comes with renewables will be critical as the sector pivots toward renewable energy. A recent coal moratorium may position natural gas as a transition fuel—this could stimulate exploration and production investments for new, indigenous natural gas fields, gas pipeline infrastructure, and LNG import terminal projects. 14 Philippine energy plan 2020–2040, Department of Energy Philippines, June 10, 2022; Power development plan 2020–2040 , Department of Energy Philippines, 2021. The increasing momentum of green energy auctions could facilitate the development of renewables at scale, as the country targets 35 percent share of renewables by 2030. 15 Power development plan 2020–2040 , 2022.

Growth in the healthcare industry may slow to 2.8 percent in 2024, while pharmaceuticals manufacturing is expected to rebound with 5.2 percent growth in 2024. 16 McKinsey analysis in partnership with Oxford Economics.

Healthcare demand could grow, although the quality of care may be strained as the health worker shortage is projected to increase over the next five years. 17 McKinsey analysis. The supply-and-demand gap in nursing alone is forecast to reach a shortage of approximately 90,000 nurses by 2028. 18 McKinsey analysis. Another compounding factor straining healthcare is the higher than anticipated benefit utilization and rising healthcare costs, which, while helping to meet people's healthcare budgets, may continue to drive down profitability for health insurers.

Meanwhile, pharmaceutical companies are feeling varying effects of people becoming increasingly health conscious. Consumers are using more over the counter (OTC) medication and placing more beneficial value on organic health products, such as vitamins and supplements made from natural ingredients, which could impact demand for prescription drugs. 19 “Consumer health in the Philippines 2023,” Euromonitor, October 2023.

Businesses operating in this field may end up benefiting from universal healthcare policies. If initiatives are implemented that integrate healthcare systems, rationalize copayments, attract and retain talent, and incentivize investments, they could potentially help to strengthen healthcare provision and quality.

Businesses may also need to navigate an increasingly complex landscape of diverse health needs, digitization, and price controls. Digital and data transformations are being seen to facilitate improvements in healthcare delivery and access, with leading digital health apps getting more than one million downloads. 20 Google Play Store, September 27, 2023. Digitization may create an opportunity to develop healthcare ecosystems that unify touchpoints along the patient journey and provide offline-to-online care, as well as potentially realizing cost efficiencies.

Consumer and retail

Growth in the retail and wholesale trade and consumer goods sectors is projected to remain stable in 2024, at 4 percent and 5 percent, respectively.

Inflation, however, continues to put consumers under pressure. While inflation rates may fall—predicted to reach 4 percent in 2024—commodity prices may still remain elevated in the near term, a top concern for Filipinos. 21 “IMF raises Philippine growth forecast,” July 26, 2023; “Nomura downgrades Philippines 2024 growth forecast,” September 11, 2023. In response to challenging economic conditions, 92 percent of consumers have changed their shopping behaviors, and approximately 50 percent indicate that they are switching brands or retail providers in seek of promotions and better prices. 22 “Philippines consumer pulse survey, 2023,” McKinsey, November 2023.

Online shopping has become entrenched in Filipino consumers, as they find that they get access to a wider range of products, can compare prices more easily, and can shop with more convenience. For example, a McKinsey Philippines consumer sentiment survey in 2023 found that 80 percent of respondents, on average, use online and omnichannel to purchase footwear, toys, baby supplies, apparel, and accessories. To capture the opportunity that this shift in Filipino consumer preferences brings and to unlock growth in this sector, retail organizations could turn to omnichannel strategies to seamlessly integrate online and offline channels. Businesses may need to explore investments that increase resilience across the supply chain, alongside researching and developing new products that serve emerging consumer preferences, such as that for natural ingredients and sustainable sources.

Manufacturing

Manufacturing is a key contributor to the Philippine economy, contributing approximately 19 percent of GDP in 2022, employing about 7 percent of the country’s labor force, and growing in line with GDP at approximately 6 percent between 2023 and 2024. 23 McKinsey analysis based on input from industry experts.

Some changes could be seen in 2024 that might affect the sector moving forward. The focus toward building resilient supply chains and increasing self-sufficiency is growing. The Philippines also is likely to benefit from increasing regional trade, as well as the emerging trend of nearshoring or onshoring as countries seek to make their supply chains more resilient. With semiconductors driving approximately 45 percent of Philippine exports, the transfer of knowledge and technology, as well as the development of STEM capabilities, could help attract investments into the sector and increase the relevance of the country as a manufacturing hub. 24 McKinsey analysis based on input from industry experts.

To secure growth, public and private sector support could bolster investments in R&D and upskill the labor force. In addition, strategies to attract investment may be integral to the further development of supply chain infrastructure and manufacturing bases. Government programs to enable digital transformation and R&D, along with a strategic approach to upskilling the labor force, could help boost industry innovation in line with Industry 4.0 demand. 25 Industry 4.0 is also referred to as the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Priority products to which manufacturing industries could pivot include more complex, higher value chain electronic components in the semiconductor segment; generic OTC drugs and nature-based pharmaceuticals in the pharmaceutical sector; and, for green industries, products such as EVs, batteries, solar panels, and biomass production.

Information technology business process outsourcing

The information technology business process outsourcing (IT-BPO) sector is on track to reach its long-term targets, with $38 billion in forecast revenues in 2024. 26 Khriscielle Yalao, “WHF flexibility key to achieving growth targets—IBPAP,” Manila Bulletin , January 23, 2024. Emerging innovations in service delivery and work models are being observed, which could drive further growth in the sector.

The industry continues to outperform headcount and revenue targets, shaping its position as a country leader for employment and services. 27 McKinsey analysis based in input from industry experts. Demand from global companies for offshoring is expected to increase, due to cost containment strategies and preference for Philippine IT-BPO providers. New work setups continue to emerge, ranging from remote-first to office-first, which could translate to potential net benefits. These include a 10 to 30 percent increase in employee retention; a three- to four-hour reduction in commute times; an increase in enabled talent of 350,000; and a potential reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of 1.4 to 1.5 million tons of CO 2 per year. 28 McKinsey analysis based in input from industry experts. It is becoming increasingly more important that the IT-BPO sector adapts to new technologies as businesses begin to harness automation and generative AI (gen AI) to unlock productivity.

Talent and technology are clear areas where growth in this sector can be unlocked. The growing complexity of offshoring requirements necessitates building a proper talent hub to help bridge employee gaps and better match local talent to employers’ needs. Businesses in the industry could explore developing facilities and digital infrastructure to enable industry expansion outside the metros, especially in future “digital cities” nationwide. Introducing new service areas could capture latent demand from existing clients with evolving needs as well as unserved clients. BPO centers could explore the potential of offering higher-value services by cultivating technology-focused capabilities, such as using gen AI to unlock revenue, deliver sales excellence, and reduce general administrative costs.

Sustainability

The Philippines is considered to be the fourth most vulnerable country to climate change in the world as, due to its geographic location, the country has a higher risk of exposure to natural disasters, such as rising sea levels. 29 “The Philippines has been ranked the fourth most vulnerable country to climate change,” Global Climate Risk Index, January 2021. Approximately $3.2 billion, on average, in economic loss could occur annually because of natural disasters over the next five decades, translating to up to 7 to 8 percent of the country’s nominal GDP. 30 “The Philippines has been ranked the fourth most vulnerable country to climate change,” Global Climate Risk Index, January 2021.

The Philippines could capitalize on five green growth opportunities to operate in global value chains and catalyze growth for the nation:

- Renewable energy: The country could aim to generate 50 percent of its energy from renewables by 2040, building on its high renewable energy potential and the declining cost of producing renewable energy.

- Solar photovoltaic (PV) manufacturing: More than a twofold increase in annual output from 2023 to 2030 could be achieved, enabled by lower production costs.

- Battery production: The Philippines could aim for a $1.5 billion domestic market by 2030, capitalizing on its vast nickel reserves (the second largest globally). 31 “MineSpans,” McKinsey, November 2023.

- Electric mobility: Electric vehicles could account for 15 percent of the country’s vehicle sales by 2030 (from less than 1 percent currently), driven by incentives, local distribution, and charging infrastructure. 32 McKinsey analysis based on input from industry experts.

- Nature-based solutions: The country’s largely untapped total abatement potential could reach up to 200 to 300 metric tons of CO 2 , enabled by its biodiversity and strong demand.

The Philippine economy: Three scenarios for growth

Having grown faster than other economies in Southeast Asia in 2023 to end the year with 5.6 percent growth, the Philippines can expect a similarly healthy growth outlook for 2024. Based on our analysis, there are three potential scenarios for the country’s growth. 33 McKinsey analysis in partnership with Oxford Economics.

Slower growth: The first scenario projects GDP growth of 4.8 percent if there are challenging conditions—such as declining trade and accelerated inflation—which could keep key policy rates high at about 6.5 percent and dampen private consumption, leading to slower long-term growth.

Soft landing: The second scenario projects GDP growth of 5.2 percent if inflation moderates and global conditions turn out to be largely favorable due to a stable investment environment and regional trade demand.

Accelerated growth: In the third scenario, GDP growth is projected to reach 6.1 percent if inflation slows and public policies accommodate aspects such as loosening key policy rates and offering incentive programs to boost productivity.

Focusing on factors that could unlock growth in its seven critical sectors and themes, while adapting to the macro-economic scenario that plays out, would allow the Philippines to materialize its growth potential in 2024 and take steps towards achieving longer-term, sustainable economic growth.

Jon Canto is a partner in McKinsey’s Manila office, where Frauke Renz is an associate partner, and Vicah Villanueva is a consultant.

The authors wish to thank Charlene Chua, Charlie del Rosario, Ryan delos Reyes, Debadrita Dhara, Evelyn C. Fong, Krzysztof Kwiatkowski, Frances Lee, Aaron Ong, and Liane Tan for their contributions to this article.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

The Philippines Growth Dialogues

What does 2023 hold for the Philippines’ economy?

On the verge of a digital banking revolution in the Philippines

The Philippine economy under the pandemic: From Asian tiger to sick man again?

Subscribe to the center for asia policy studies bulletin, ronald u. mendoza ronald u. mendoza dean and professor, ateneo school of government - ateneo de manila university @profrum.

August 2, 2021

In 2019, the Philippines was one of the fastest growing economies in the world. It finally shed its “sick man of Asia” reputation obtained during the economic collapse towards the end of the Ferdinand Marcos regime in the mid-1980s. After decades of painstaking reform — not to mention paying back debts incurred under the dictatorship — the country’s economic renaissance took root in the decade prior to the pandemic. Posting over 6 percent average annual growth between 2010 and 2019 (computed from the Philippine Statistics Authority data on GDP growth rates at constant 2018 prices), the Philippines was touted as the next Asian tiger economy .

That was prior to COVID-19.

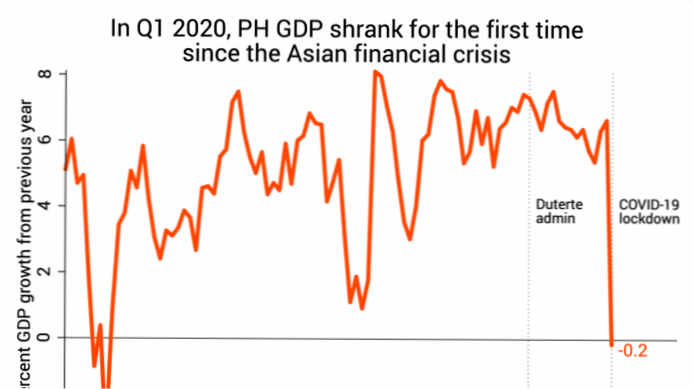

The rude awakening from the pandemic was that a services- and remittances-led growth model doesn’t do too well in a global disease outbreak. The Philippines’ economic growth faltered in 2020 — entering negative territory for the first time since 1999 — and the country experienced one of the deepest contractions in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) that year (Figure 1).

Figure 1: GDP growth for selected ASEAN countries

And while the government forecasts a slight rebound in 2021, some analysts are concerned over an uncertain and weak recovery, due to the country’s protracted lockdown and inability to shift to a more efficient containment strategy. The Philippines has relied instead on draconian mobility restrictions across large sections of the country’s key cities and growth hubs every time a COVID-19 surge threatens to overwhelm the country’s health system.

What went wrong?

How does one of the fastest growing economies in Asia falter? It would be too simplistic to blame this all on the pandemic.

First, the Philippines’ economic model itself appears more vulnerable to disease outbreak. It is built around the mobility of people, yet tourism, services, and remittances-fed growth are all vulnerable to pandemic-induced lockdowns and consumer confidence decline. International travel plunged, tourism came to a grinding halt, and domestic lockdowns and mobility restrictions crippled the retail sector, restaurants, and hospitality industry. Fortunately, the country’s business process outsourcing (BPO) sector is demonstrating some resilience — yet its main markets have been hit heavily by the pandemic, forcing the sector to rapidly upskill and adjust to emerging opportunities under the new normal.

Related Books

Thomas Wright, Colin Kahl

August 24, 2021

Jonathan Stromseth

February 16, 2021

Tarun Chhabra, Rush Doshi, Ryan Hass, Emilie Kimball

June 22, 2021

Second, pandemic handling was also problematic. Lockdown is useful if it buys a country time to strengthen health systems and test-trace-treat systems. These are the building blocks of more efficient containment of the disease. However, if a country fails to strengthen these systems, then it squanders the time that lockdown affords it. This seems to be the case for the Philippines, which made global headlines for implementing one of the world’s longest lockdowns during the pandemic, yet failed to flatten its COVID-19 curve.

At the time of writing, the Philippines is again headed for another hard lockdown and it is still trying to graduate to a more efficient containment strategy amidst rising concerns over the delta variant which has spread across Southeast Asia . It seems stuck with on-again, off-again lockdowns, which are severely damaging to the economy, and will likely create negative expectations for future COVID-19 surges (Figure 2).

Figure 2 clarifies how the Philippine government resorted to stricter lockdowns to temper each surge in COVID-19 in the country so far.

Figure 2: Community quarantine regimes during the COVID-19 pandemic, Philippine National Capital Region (NCR ), March 2020 to June 2021

If the delta variant and other possible variants are near-term threats, then the lack of efficient containment can be expected to force the country back to draconian mobility restrictions as a last resort. Meanwhile, only two months of social transfers ( ayuda ) were provided by the central government during 16 months of lockdown by mid-2021. All this puts more pressure on an already weary population reeling from deep recession, job displacement, and long-term risks on human development . Low social transfers support in the midst of joblessness and rising hunger is also likely to weaken compliance with mobility restriction policies.

Third, the Philippines suffered from delays in its vaccination rollout which was initially hobbled by implementation and supply issues, and later affected by lingering vaccine hesitancy . These are all likely to delay recovery in the Philippines.

By now there are many clear lessons both from the Philippine experience and from emerging international best practices. In order to mount a more successful economic recovery, the Philippines must address the following key policy issues:

- Build a more efficient containment strategy particularly against the threat of possible new variants principally by strengthening the test-trace-treat system. Based on lessons from other countries, test-trace-treat systems usually also involve comprehensive mass-testing strategies to better inform both the public and private sectors on the true state of infections among the population. In addition, integrated mobility databases (not fragmented city-based ones) also capacitate more effective and timely tracing. This kind of detailed and timely data allows for government and the private sector to better coordinate on nuanced containment strategies that target areas and communities that need help due to outbreak risk. And unlike a generalized lockdown, this targeted and data-informed strategy could allow other parts of the economy to remain more open than otherwise.

- Strengthen the sufficiency and transparency of direct social protection in order to give immediate relief to poor and low-income households already severely impacted by the mishandling of the pandemic. This requires a rebalancing of the budget in favor of education, health, and social protection spending, in lieu of an over-emphasis on build-build-build infrastructure projects. This is also an opportunity to enhance the social protection system to create a safety net and concurrent database that covers not just the poor but also the vulnerable low- and lower-middle- income population. The chief concern here would be to introduce social protection innovations that prevent middle income Filipinos from sliding into poverty during a pandemic or other crisis.

- Ramp-up vaccination to cover at least 70 percent of the population as soon as possible, and enlist the further support of the private sector and civil society in order to keep improving vaccine rollout. An effective communications campaign needs to be launched to counteract vaccine hesitancy, building on trustworthy institutions (like academia, the Catholic Church, civil society and certain private sector partners) in order to better protect the population against the threat of delta or another variant affecting the Philippines. It will also help if parts of government could stop the politically-motivated fearmongering on vaccines, as had occurred with the dengue fever vaccine, Dengvaxia, which continues to sow doubts and fears among parts of the population .

- Create a build-back-better strategy anchored on universal and inclusive healthcare. Among other things, such a strategy should a) acknowledge the critically important role of the private sector and civil society in pandemic response and healthcare sector cooperation, and b) underpin pandemic response around lasting investments in institutions and technology that enhance contact tracing (e-platforms), testing (labs), and universal healthcare with lower out-of-pocket costs and higher inclusivity. The latter requires a more inclusive, well-funded, and better-governed health insurance system.

As much of ASEAN reels from the spread of the delta variant, it is critical that the Philippines takes these steps to help allay concerns over the country’s preparedness to handle new variants emerging, while also recalibrating expectations in favor of resuscitating its economy. Only then can the Philippines avoid becoming the sick man of Asia again, and return to the rapid and steady growth of the pre-pandemic decade.

Related Content

Emma Willoughby

June 29, 2021

Adrien Chorn, Jonathan Stromseth

May 19, 2021

Thomas Pepinsky

January 26, 2021

Adrien Chorn provided editing assistance on this piece. The author thanks Jurel Yap and Kier J. Ballar for their research assistance. All views expressed herein are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of his institution.

Foreign Policy

Southeast Asia

Center for Asia Policy Studies

Mireya Solís

April 5, 2024

Tara Varma, Bruno Tertrais, Jim Townsend, Andrea Kendall-Taylor

Vanda Felbab-Brown, Jeffrey Feltman, Sharan Grewal, Steven Heydemann, Marvin Kalb, Patricia M. Kim, Tanvi Madan, Suzanne Maloney, Allison Minor, Bruce Riedel, Natan Sachs, Valerie Wirtschafter

- How We Work

- CrisisWatch

- Upcoming Events

- Event Recordings

- Afrique 360

- Hold Your Fire

- Ripple Effect

- War & Peace

- Photography

- For Journalists

- Download Full Report (English)

- Introduction

- The Philippine Claim over Time

- The 2016 Arbitration Award

- The Pivot to China

- A Quiet Sea?

- Geopolitics Come Back to the Fore

- The President

- The Diplomats

- The Military

- Other Security Actors

- Political and Economic Elites

- Public Opinion

- Scarborough Shoal

- The Spratlys

- Declining Fish Stocks

- Oil and Gas

- Dealing with Dilemmas

- Risk Management Mechanisms

- Using Minilaterals to Fill Governance Gaps

- Calibrate the Code of Conduct

- Keeping China in the Loop

Appendix D: Recommendations

The Philippines’ Dilemma: How to Manage Tensions in the South China Sea

The maritime dispute between China and the Philippines is simmering against the backdrop of strategic competition between Beijing and Washington. To keep tensions below boiling point, Manila should push for a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea as well as greater regional cooperation.

- "> Download PDF Full Report (en)

Principal Findings

What’s new? Five years after President Rodrigo Duterte’s pivot to China, tensions between Manila and Beijing are rising again in the South China Sea, compounded by increasing Sino-U.S. competition. The maritime disputes with China and other claimant states persist with little prospect for resolution.

Why does it matter? Armed conflict directly involving the Philippines is unlikely. But there is growing potential for incidents at sea to escalate . Despite President Duterte’s China-friendly stance, Manila continues to struggle with Beijing’s continuous efforts to assert sovereignty over most of the South China Sea.

What should be done? The Philippines should push for a substantive and effective Code of Conduct between ASEAN and China, while continuing to pursue bilateral talks with Beijing on maritime disputes. Manila should also try to boost regional cooperation on issues of common concern, such as fisheries management and law enforcement.

Executive Summary

The Philippines is a key player in the South China Sea territorial disputes, which are getting sharper due to China’s growing assertiveness and the claimant states’ competition over resources. Rather than appealing to international law as a bulwark against China’s claims, President Rodrigo Duterte has instead pursued a more pragmatic approach that avoids confronting China in the hope of reaping economic benefits. But five years on, it appears that his pivot may not have entirely paid off. The simmering maritime dispute between Manila and Beijing is increasingly linked to geopolitical competition between China, on one hand, and the U.S. and its allies, on the other. Given the growing risk of escalatory incidents at sea, Manila should push for a substantive and effective Code of Conduct between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to manage maritime tensions while keeping open a diplomatic channel with Beijing to reduce misunderstandings. It should also strive to foster regional cooperation, for example on the question of fisheries management.

Eager to loosen ties with the U.S. and broaden his strategic options, Duterte has throughout his presidency minimised the issue of territorial sovereignty in the South China Sea and instead sought economic benefits from China. Consistent with this approach, he downplayed Manila’s victory in a 2016 arbitration, awarded by a tribunal established under the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which refuted Beijing’s extensive claims of sovereignty and “historic rights” over the Sea. Manila has since pursued a flexible strategy, often perceived by local and international observers alike as erratic, aiming to strengthen ties with Beijing for the sake of economic growth. By proceeding cautiously, the Philippines hoped to prevent the maritime dispute from damaging its bilateral relationship with the region’s dominant economic and military power.

Five years into Duterte’s presidency, however, irritants remain. China’s ships prowl the Philippine exclusive economic zone without interruption, and Filipino boats often cannot reach traditional fishing grounds at Scarborough Shoal due to Chinese harassment. Tangible economic benefits from overtures to Beijing, especially promised infrastructure projects, have fallen short of expectations and major gains are not expected before Duterte’s term ends in 2022. Many in the Philippines are increasingly sceptical of rapprochement with China if it entails giving up claims to various disputed maritime features.

Since late 2019, Manila has been less willing to ignore Beijing’s assertiveness in the South China Sea. It has sent diplomatic protest notes to China in response to perceived territorial violations in the Sea. More consequentially, Duterte has reversed his abrupt February 2020 cancellation of the Visiting Forces Agreement with the U.S., which allows the U.S. to station military personnel in the Philippines and conduct joint exercises with Manila. In June 2020, Duterte suspended the cancellation. The U.S. subsequently began terming China’s claims in the Sea “unlawful”, reaffirmed its alliance with the Philippines and confirmed that the Mutual Defence Treaty between Manila and Washington encompasses attacks on Philippine forces or vessels in the Sea. A March 2021 quarrel around Whitsun Reef in the disputed Spratly Islands, which saw Chinese ships mass by the hundreds, led to another wave of anti-China sentiment in the Philippines and appears to have further strained relations. On 30 July 2021, Duterte unfroze the Visiting Forces Agreement, thus bringing it formally back into force.

Developing a coherent vision for the South China Sea while managing a treaty alliance with the U.S. and episodic tensions with neighbours, one of which is a rising great power, is particularly challenging. On one hand, Manila is tied to Washington by an alliance and longstanding cultural affinities. On the other, geography and economic imperatives impel the archipelago to find a modus vivendi with Beijing. At the same time, the Philippines must all the while maintain constructive relations with other South East Asian claimants. In addition, conflicting interests among and within the bureaucratic establishment and the military, as well as the interplay of elite positioning and Philippine public opinion, often result in apparent contradictions in government policy.

Manila, facing deadlock in a dispute it cannot resolve alone, should try to foster cooperation by discussing issues of common interest – such as fisheries management, law enforcement challenges and scientific research on environmental problems – in formal and informal interactions with neighbouring countries. Partnerships with other littoral states on joint management of resources could serve as a stepping stone for broader cooperation. In the interest of peace and stability in the South China Sea, Manila should both double down on its efforts to advance Code of Conduct negotiations and keep up bilateral dialogue with Beijing to sort out misunderstandings and manage disagreements. It should, for instance, negotiate rules of access to Scarborough Shoal, long a source of friction with China. It should also strengthen risk management mechanisms in case tensions between claimant states or the U.S. and China increase. None of these steps will resolve the increasingly entrenched maritime dispute, but they could help keep the risk low that incidents at sea will escalate toward conflict.

Manila/Brussels, 2 December 2021

To access this timeline of The Recent History of the South China Sea as a separate article page, please click here .

I. Introduction

In the South China Sea, the Philippines is party to a long-running quarrel that is a source of friction, and could even trigger an open confrontation, between China and the United States. [fn] For background, see Crisis Group Asia Reports N°275, Stirring up the South China Sea (IV): Oil in Troubled Waters , 26 January 2016 ; N°267, Stirring Up the South China Sea (III): A Fleeting Opportunity for Calm , 7 May 2015 ; N°229, Stirring up the South China Sea (II): Regional Responses , 24 July 2012; and N°223, Stirring Up the South China Sea (I) , 23 April 2012. Hide Footnote The dispute – to which Brunei, China, Malaysia, Taiwan and Vietnam are also party – is driven by competing claims to land features and the maritime entitlements they generate, including overlapping exclusive economic zones (EEZ). [fn] The EEZ of a coastal state, in which the state is entitled to the marine and undersea resources, stretches 200 nautical miles (nm) from its baseline, itself determined by the low-tide coastline (or, in some cases, by offshore features). A coastal state can claim full sovereignty over land, sea and air only within a zone extending 12nm offshore. For more details, see Crisis Group Asia Report N°315, Competing Visions of International Order in the South China Sea , 29 November 2021, pp. 2-3. Hide Footnote The Philippine claim focuses on the Spratly Islands and the maritime space around them, including Scarborough Shoal, a small ring of rocks and reefs more than 200km west of Luzon, the Philippines’ largest and most populous island. [fn] The Spratlys and Scarborough Shoal are commonly referred to as part of the South China Sea. Around June 2011, however, the Philippines began using the term West Philippine Sea for the area in its official communications. President Benigno Aquino III officially renamed the body of water through Administrative Order 29 of 5 September 2012, issued after a standoff with China at Scarborough Shoal. The Philippines claims specific islands and areas of the sea rather than the Spratlys as a whole. Hide Footnote

Manila’s claim to the Spratlys goes back at least half a century. It conflicts with China’s narrative of its own historic rights, expressed in the so-called nine-dash line, a boundary drawn on Chinese maps in 2009, but without clear historic or legal grounds, definition or delineation, and that lays claim to some 85 per cent of the South China Sea. The other littoral states are likewise affected, with Vietnam more emphatic than the rest in defending its interests against China. Both Beijing and Hanoi dispute Manila’s claims, as do, to a lesser degree, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan. [fn] Indonesia is not a claimant in the South China Sea dispute, but it remains an important player as maritime zones generated by its Natuna Islands appear to overlap with China’s claims. Hide Footnote

The Philippines’ location accounts for both the U.S. and the Chinese strategic interest in the archipelago. Midway between mainland South East Asia and Indonesia, the region’s other archipelago, the country is composed of 7,641 islands and has the world’s fifth-longest coastline, with most of its provinces bordering the sea. [fn] Control over the South China Sea implies dominance over the Malacca and Sunda Straits, both crucial chokepoints for global trade, as well as the Sulu and Taiwan Straits. Hide Footnote Its proximity to the Taiwan Strait puts it close to a “powder keg of conflict”. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, retired diplomat, 23 July 2020. Some of the Philippine outposts in the Spratlys are also close to Itu Aba, the largest natural land feature in the archipelago, which is occupied by Taiwan and is the forwardmost of Taipei’s defences. Ralph Jennings, “Wary of Beijing, Taiwan doubles down on South China Sea island”, Voice of America, 29 March 2021. Hide Footnote It also stands between a segment of China’s coast and access to the Pacific Ocean, thereby constituting a crucial part of what is often referred to as the “first island chain” that delimits China’s near sea. [fn] The first island chain refers to a chain of archipelagos stretching from Indonesia through Japan to the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia. The concept has been known in both U.S. and Chinese strategic circles for decades, defined as a natural barrier that is disadvantageous for China since it contains Beijing’s maritime power and access to the Pacific while serving as a forward defence perimeter for U.S. forces in Asia. Hide Footnote

The Philippines is thus a key player in the geopolitical contest playing out in the region. For Beijing, it could either become a stepping stone toward regional hegemony or an obstacle to such ambitions. Likewise, for Washington, it could continue to facilitate the U.S. forward presence in the South China Sea or become a stumbling block for its Indo-Pacific strategy. All these scenarios entail political costs and benefits for Manila. As Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin has said: “No other country feels the significant impact of the rivalry between the two superpowers more than the Philippines, the U.S. being its only defence treaty ally and China its biggest neighbour and top economic partner – with the U.S. second”. [fn] Recto Mercene, “Locsin: PHL to keep strong ties with both US and China”, Business Mirror , 27 October 2020. Hide Footnote

This report provides a view of the Philippine perspective on developments in the South China Sea since 2016, against the backdrop of China’s geopolitical ascendancy, heightened U.S.-China tensions and Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency. [fn] This report uses English-language terms for features in the South China Sea. Hide Footnote It is published along with a report on Vietnamese perspectives on the South China Sea dispute, and an overview detailing the rising frictions between the U.S. and China as they relate to the Sea. [fn] See Crisis Group Report, Competing Visions of International Order in the South China Sea , op. cit.; and Crisis Group Asia Report, Vietnam Tacks Between Cooperation and Struggle in the South China Sea , forthcoming. Hide Footnote It is based on more than 140 interviews and online discussions in Manila with current and former government officials, diplomats, academics, analysts and military officers, many of whom requested anonymity. Research was largely conducted remotely given travel restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, though the report includes input from a local researcher who visited Masinloc, the Philippine town closest to Scarborough Shoal.

II. Reefs and Ruptures

A. the philippine claim over time.

The Philippines’ efforts to assert its claims in the South China Sea date back to the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos, the dictator who ruled the country from 1965 to 1986. [fn] In 1956, a Filipino adventurer, Tomas Cloma, sailed out to the Spratlys seeking his fortune and laid claim to 33 features that he called Freedomland. Authorities arrested Cloma in 1974. Manila then asked him to formally transfer ownership of the features to the government, after which it asserted its sovereignty there. Hide Footnote Marcos sent the military in two waves (from 1970 to 1971, and from 1977 to 1980) to occupy several features in the Spratly archipelago. [fn] Marites Danguilan Vitug, Rock Solid: How the Philippines Won Its Maritime Case Against China (Manila, 2018), p. 10. In 1975, Vietnam occupied Southwest Cay, a feature where the Philippines had previously stationed an “on-and-off detachment”. Ibid., p.12. Hide Footnote In 1972, the Marcos government officially incorporated the islets into the Philippines’ westernmost Palawan province as the Kalayaan Island Group. [fn] In 1976, Manila created the Western Command, a military district covering the Spratlys. Hide Footnote In 1978, it formally created both a separate Kalayaan municipality in Palawan province and a Philippine exclusive economic zone. [fn] See Presidential Decree No. 1599 , 1978. Although the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was signed in 1982, UN members had been negotiating over the EEZ concept for years before the close of talks. Hide Footnote As a result, Manila has controlled nine of the Spratlys’ land features since the late 1970s. [fn] These are: Second Thomas Shoal (Ayungin), Thitu (Pagasa) Island, Nanshan (Lawak) Island, Northeast Cay (Parola Island), Flat (Patag) Island, Loaita (Kota) Island, Commodore (Rizal) Reef, West York (Likas) Island and Loaita Cay (Panata Island). Other Spratly features are controlled by Taiwan, China, Vietnam and Malaysia. Hide Footnote It remained on the sidelines when armed conflict erupted between Vietnam and China around the Paracel Islands in 1988. At the time, the Philippines was less concerned with China occupying features in the Spratlys (in 1988 and 1989) and Beijing’s heightened naval patrols than with Vietnam’s presence in the contested waters around them. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, military officer, 10 November 2020. Hide Footnote

China’s 1995 seizure of Mischief Reef, in the middle of the Spratlys, marked a major shift in the contest for control of those features. Seeing an opportunity after a Philippines Senate vote in 1991 compelled the U.S. to withdraw from its Philippine bases, China built light structures on the reef. [fn] In addition, China maintained a naval presence and constructed navigational aid facilities and a military observation post on the reef. Vitug, Rock Solid , op. cit., pp. 29-30. Hide Footnote The construction was a “shock” to the Philippines, deeply affecting its sense of security, particularly after Chinese troops occupied the new structures. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, academic, 6 August 2020. It was the first time that China had acted against the territorial entitlements of an Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member. Despite Manila’s lobbying, its fellow members issued only a muted statement on the incident. Hide Footnote Despite the 1951 Philippine-U.S. Mutual Defence Treaty, Washington remained neutral in Manila’s ensuing quarrel with Beijing and gave its ally no clear assurances of support. [fn] Longstanding U.S. policy was that the Mutual Defence Treaty did not cover contested territories in the South China Sea. Hide Footnote Questions accordingly arose among Philippine policymakers and diplomats about the utility of the strategic alliance with the U.S. [fn] “The Treaty was always subject to interpretation”. Crisis Group online interview, former Philippine diplomat, 3 August 2020. Hide Footnote

In August 1995, Beijing and Manila signed a bilateral Code of Conduct to curb tensions in the aftermath of the Mischief Reef incident, though any respite was short-lived. The Chinese naval presence in the disputed areas and bellicose rhetoric from both sides continued to exacerbate tensions and soon highlighted the agreement’s ineffectiveness. In 1997, fishermen from both countries squabbled around Scarborough Shoal. [fn] Scarborough Shoal, known in the Philippines as Bajo de Masinloc, is 220km or 120nm from the Philippine province of Zambales. Hide Footnote President Fidel Ramos’ government responded by seeking a closer partnership with Vietnam and launching a modernisation of the Philippine armed forces. This effort was, however, beset with difficulties due to mismanagement and the impact of the Asian financial crisis on government finances. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, defence analyst, 30 June 2020. Hide Footnote The dispute continued with ebbs and flows from 1998 to 2010, during the presidencies of Joseph Estrada and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. [fn] Appendix B describes the various Philippine presidents’ policies in more detail. Hide Footnote

It was Benigno Aquino’s presidency (2010-2016), however, that significantly changed the dispute’s dynamics, particularly after another Scarborough Shoal incident in 2012. Following an altercation between Chinese and Filipino fishermen in the area, the Philippine navy dispatched a ship to arrest the Chinese as poachers. Although Manila later replaced the vessel with a coast guard ship, Beijing retaliated by deploying more naval assets, leading to a month-long standoff. [fn] At the height of the standoff, China banned Philippine banana imports and encouraged its companies to reduce investment in the archipelago. Hide Footnote The U.S. tried to broker a simultaneous withdrawal by both sides, but the verbal agreement Washington struck with a Chinese representative fell through. [fn] Crisis Group Report, Stirring Up the South China Sea (III) , op. cit., p. 16. Hide Footnote While both countries did call their vessels home, the Chinese quickly returned and have occupied the shoal ever since. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, journalist, 24 September 2020. Some observers have suggested that the U.S. did not consider intervening directly in the standoff as it was not an armed conflict and posed no direct threat to U.S. ships. See Humphrey Hawksley, Asian Waters (New York, 2018), p.71. Hide Footnote The incident once again raised uneasy questions in Manila about Washington’s stance despite the Philippines’ status as a U.S. treaty ally. Manila also unsuccessfully appealed to the U.S. for a guarantee of assistance if China used force. [fn] Crisis Group Report, Stirring Up the South China Sea (II) , op. cit., p.9. During the standoff, the U.S. also failed to clarify whether the Mutual Defence Treaty covered the South China Sea. In a speech on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the alliance in September 2021, Philippine Defence Secretary Delfin Lorenzana recounted that during the standoff, the U.S. “ruled out any robust intervention to assist the Philippines”. “The U.S.-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty at 70”, Center for Strategic and International Studies (webinar), 8 September 2021. Hide Footnote

As a former Philippine official summed up the doubts: “Our position turned from what we thought was strategic clarity, as a partner and ally, to strategic ambiguity”. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, 1 November 2020. Hide Footnote

B. The 2016 Arbitration Award

As direct negotiation with China on the maritime dispute led nowhere, Aquino pursued the legal option, filing a case challenging China’s territorial claims under Annex VII of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). [fn] The tribunal acknowledged the Philippine effort to seek a resolution through dialogue. “We tried to talk”, a diplomat said. Crisis Group online interview, 18 September 2020. Hide Footnote The Permanent Court of Arbitration hosted the proceedings. Manila resorted to the international tribunal to resolve questions of interpretation bearing on Beijing’s maritime claims, including the validity of claims rooted in historic rights as manifested by the nine-dash line. The Philippine decision to take the legal route reportedly “was like a shock” for Beijing. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, academic, 23 August 2020. ASEAN and most of its member states were conspicuously silent on the arbitration. Though Hanoi supported Manila’s submission, the Philippines was otherwise on its own. Hide Footnote China cancelled several high-level events and summits and issued a travel advisory that diminished tourism in the Philippines. Overall, Beijing’s response was “very disproportionate”, according to a former Philippine official. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, 25 September 2020. Hide Footnote

On 12 July 2016, the Court finally delivered a ruling in the Philippines’ favour. The central finding was that China’s nine-dash line and assertion of “historic rights” have no basis in international law. [fn] As China did not participate in the arbitration, it avoided having to clarify the nine-dash line’s path. Although Vietnam claims the entire Spratlys, it did not object to the award. Hide Footnote The Court declared Scarborough Shoal a traditional fishing ground of Chinese (including from Taiwan), Philippine and Vietnamese fishermen, and ruled that China had violated international law by denying Filipinos access to the area. Importantly, the Court also ruled that no feature in the Spratlys could be legally classified as an island capable of generating an EEZ or a continental shelf. [fn] Crisis Group Report, Competing Visions of International Order in the South China Sea , op. cit., pp. 2-3. Hide Footnote Instead, all features were found to be “rocks” or “low-tide elevations” under UNCLOS. [fn] An important merit of the arbitration was the definition of what constitutes an “island” under international law, particularly the necessity of sustaining human habitation. Hide Footnote A ruling on sovereignty over the Spratlys and their associated maritime zones was, however, outside the tribunal’s jurisdiction. Likewise, territorial sovereignty over Scarborough Shoal remains ambiguous, as both Chinese and Philippine claims persist. [fn] A coastal state’s rights over its EEZ and continental shelf are “sovereign rights” that are not equivalent to sovereignty. Sovereign rights are recognised for the purpose of exploration and exploitation of the living and non-living resources in these areas. Crisis Group correspondence, legal scholar, 9 October 2020. Hide Footnote

Though the ruling did not generate an explicit jurisprudential precedent, as it only binds the Philippines and China, “the practical reality is that the pronouncement of the arbitral tribunal will be difficult to disregard, let alone challenge in any future litigation or negotiated agreement in respect of the South China Sea”. [fn] Crisis Group email correspondence, legal scholar, 25 September 2020. A Philippine government official said: “We do not have control any more, since international law now owns the arbitration. The genie is out of the bottle”. Crisis Group online interview, 18 September 2020. Hide Footnote The award spawned an immense body of literature and became an important reference point in international law.

But while Manila won the legal argument, the Aquino administration appeared to have given little if any thought to the possibility that China might refuse to enforce a ruling that went against its interests. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, South China Sea expert, 14 August 2020. Hide Footnote Beijing did just that, declaring the award “null and void”. An Aquino-era diplomat recalled: “It was a victory in the legal sense. But the question was: how do we implement it?” [fn] Crisis Group online interview, former diplomat, 11 September 2020. Hide Footnote Moreover, as the Philippines had acted independently of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which did not support the case for fear of antagonising China, Manila “bore the brunt” of Beijing’s ire. [fn] Crisis Group correspondence, legal scholar, 25 September 2020. ASEAN’s lukewarm support for the Philippines at the time frustrated Manila. Later, Vietnam and Malaysia observed the proceedings. Hanoi submitted a document to the tribunal in late 2014 reiterating its claims and formally opposing the nine-dash line. Hide Footnote Although the Philippines tried to drum up international support for the arbitration in the run-up to the decision, most foreign governments did little to support the ruling beyond lauding the victory of international law. [fn] Australia and Japan gave strong messages of support, but the European Union, for example, was cautious in its phrasing, providing a “soft” statement, according to former Philippine officials. Crisis Group online interview, 4 November 2020. See also Robin Emmott, “EU's statement on South China Sea reflects divisions”, Reuters, 15 July 2016. Hide Footnote Part of the reason lay in the fact that President Rodrigo Duterte took office in June 2016; his administration was much more cautious in encouraging international support and using the victory against China.

III. Enter Duterte

A. the pivot to china.

That Rodrigo Duterte would adopt an idiosyncratic foreign policy was clear from the start of his term in 2016. Inheriting Aquino’s arbitration victory, the Duterte administration noted the achievement but remained ambivalent about pressing its advantage, taking the view that triumphalism would anger Beijing. [fn] Crisis Group Commentary, “ South China Sea Ruling Sweeps Away Diplomatic Ambiguities ”, 19 July 2016. Hide Footnote Some observers agreed it was necessary to shift away from Aquino’s uncompromising stance. “Toning down the rhetoric and calibrating the response was good”, one said. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, Richard Javad Heydarian, academic, 24 September 2020. Hide Footnote But Duterte’s decision not to use the ruling at all led to missed opportunities at generating more robust international support. Instead, Manila gained only sympathy. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, journalist, 24 September 2020. Crisis Group correspondence, legal scholar, 25 September 2020. Hide Footnote

Duterte’s approach owed as much to his lack of foreign policy experience and parochial political style as to his personal dislike of the U.S. Facing U.S. and EU criticism in his administration’s first months on account of his brutal campaign to curb drug trafficking, Duterte moved closer to Beijing. [fn] Many Chinese publications stress that Beijing and Manila “reached consensus on shelving the decision of the South China Sea arbitration”. See, for example, Wu Shicun, “Preventing Confrontation and Conflict in the South China Sea”, China International Strategy Review , vol. 2 (2020), pp. 36-47. Hide Footnote In August 2016, he sent former President Fidel Ramos as special envoy to Hong Kong to set a less confrontational course in the South China Sea dispute. [fn] The Philippine delegation’s counterparts in Beijing were Wu Shicun, president of China’s National Institute for South China Sea Studies, and Fu Ying, China’s former vice foreign minister. Hide Footnote Ramos secured a non-binding communiqué emphasising cooperation and peaceful dispute resolution, with references to equal access for both countries’ fishermen to Scarborough Shoal, prospective cooperation on environmental protection and a long-term vision of demilitarisation in the Sea. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, former Philippine official, 2 November 2020. Ramos supported Aquino’s push for the arbitration, but emphasised as early as January 2013 the need to engage China diplomatically as “it was creating facts on the ground.” See Vitug, Rock Solid , op. cit., p. 162. Hide Footnote

Hide Footnote

Notwithstanding the rapprochement with Beijing and his distaste for the U.S., Duterte did not neglect other bilateral ties. He maintained a strong relationship with Japan, a traditional partner in development cooperation, the Philippines’ largest source of foreign direct investment and a supporter of the peace process in the Bangsamoro, the southern region where the government has fought a series of insurgencies. [fn] For background on this peace process, see Crisis Group Asia Reports N°313, Southern Philippines: Keeping Normalisation on Track in the Bangsamoro , 15 April 2021; N°306, Southern Philippines: Tackling Clan Politics in the Bangsamoro , 14 April 2020; and N°301, The Philippines: Militancy and the New Bangsamoro , 27 June 2019. Hide Footnote Under Duterte, Tokyo committed to developing the Philippines’ maritime capabilities, particularly its coast guard. [fn] Crisis Group interviews, Japanese officials, Manila, 21 October 2019. Hide Footnote The president also courted Russia, reflecting his desire to bolster ties with powers beyond the U.S. and China, but with limited success. [fn] Crisis Group online interviews, defence analyst, 30 June 2020; retired diplomat, 23 July 2020. Hide Footnote

A side effect of these new foreign policy initiatives was a slowdown of multilateral efforts in dealing with the South China Sea, particularly the ASEAN-China negotiations over a Code of Conduct to better manage maritime tensions among littoral states. [fn] The idea of a multilateral Code of Conduct stems from developing a clearer and more precise instrument than the 2002 non-binding Declaration between China and the Philippines, which was fairly general. Consultations on the Code have been going on since 2013. Hide Footnote “Duterte spoiled the process”, said a commentator, referring to Manila’s predominantly bilateral engagement with Beijing at the expense of a proactive multilateral approach. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, academic, 9 September 2020. Hide Footnote For Duterte, combining a quest for closer ties with multiple international actors and detente with Beijing was a way to achieve a “safe middle ground” through balancing and accommodation. [fn] Aileen Baviera, “Debating the National Interest in Philippine Relations with China: Economic, Security and Socio-cultural Dimensions”, National Security Review (2017), p. 158. Hide Footnote Distracted by internal challenges, not least the battle in Marawi (a city in the Bangsamoro) that pitted government forces against Islamist militants for five months in 2017, the Philippines did not use its ASEAN chairmanship that year to advance the South China Sea agenda. Hoping to avoid the outright confrontation with Beijing that had occurred under Aquino, Duterte put the thorny issue of territorial disputes on the back burner.

B. A Quiet Sea?

The first months of Duterte’s presidency saw improvements in relations between Beijing and Manila, even though the broader dispute in the South China Sea simmered. China did not occupy further Philippine-claimed features or cause standoffs with coast guard or navy ships, direct confrontations between Philippine and Chinese vessels declined, and Filipinos were even briefly able to fish around Scarborough Shoal thanks to the informal agreement Ramos had secured during his visit to Beijing. [fn] Part of the de-escalation stemmed from a recalibration of maritime forces. While President Duterte continued to support the coast guard build-up that started under Aquino, he encouraged the Philippine navy to be lenient with Chinese fishermen fishing illegally and not to board their boats. See “Gaining Competitive Advantage in the Gray Zone: Response Options for Coercive Aggression Below the Threshold of Major War”, RAND Corporation, 2019, p. 114. Hide Footnote Manila faced issues with another claimant state in 2017, however, after a navy ship used force against a Vietnamese boat in Philippine coastal waters, resulting in the death of two fishermen and the arrest of several more, and leading to a diplomatic crisis with Hanoi. [fn] “Philippines assures Vietnam of ‘fair’ probe into fishermen’s deaths”, Rappler.com, 25 September 2017. Hide Footnote

But even under Duterte, China’s grey zone operations – calibrated actions at sea short of live-fire attacks but intended to coerce opponents – have remained the most serious challenge to Philippine maritime sovereignty. Despite the president’s cooperative stand, Beijing has maintained a consistent maritime presence in the Spratlys and at Scarborough Shoal. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, think-tank analyst, 22 September 2020. Hide Footnote Around Thitu Island, the largest Spratly feature Manila controls, Chinese coast guard vessels and fishing boats – some if not most of which analysts believe to be part of China’s maritime militia – engaged Filipino fishermen in standoffs from 2017 onward. [fn] Officially named the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia, this force consists of fishing boats that are supported by the Chinese government with funding and operational guidance, under the navy’s supervision. The maritime militia is particularly known for using grey zone tactics, which involve the use of water cannons, ramming and intimidation of other claimants’ vessels. Nathan Swire, “Water wars”, Lawfare (blog), 5 March 2019. Hide Footnote At Scarborough Shoal, power dynamics are even more uneven: China’s coast guard regulates access to the shoal, often chasing Filipino fishermen away. Manila has dealt with these issues quietly, tackling violations of the informal agreement negotiated by Ramos through diplomatic means. As in the cases described below, it has regularly filed diplomatic protests following such incidents, to which Beijing has often reacted by making minor concessions, halting some of its provocative actions, but not all.

The foreign and defence ministries have often sought to counterbalance Duterte’s stark pro-Beijing stance, and the Philippines has also taken incremental steps to strengthen its maritime position, irritating China. For example, it started repairing facilities at Thitu Island in 2018, after attempting to build new ones in nearby Sandy Cay a year earlier, an initiative that backfired by attracting Chinese vessels that have since remained in the area. [fn] Aquino had refrained from ordering reinforcement or repair of Philippine facilities on the island, assuming that China would use such works against the Philippines. Under Duterte, construction started with repair of a beach ramp. Hide Footnote

The July 2019 Reed Bank incident, in which a Chinese coast guard ship rammed a Philippine fishing vessel, also strained bilateral relations. With the Chinese vessel leaving the scene, the Filipino crew would have perished had Vietnamese fishermen not rescued them. After a joint investigation, Beijing offered a muted apology, but the incident fanned anti-China sentiment in Philippine public opinion. [fn] Crisis Group interviews, diplomat, 29 July 2020; foreign policy expert, 21 October 2019. Hide Footnote In the following months, the relationship soured. When Duterte visited China in September 2019, he raised the 2016 arbitral ruling directly with President Xi Jinping for the first time; he came back without making progress on securing promised Chinese investments, leading observers to speculate that both leaders had left the meeting disappointed. [fn] Crisis Group interview, 24 July 2020. Hide Footnote A few months after the Reed Bank incident, other littoral states also began to adopt more assertive positions toward China. [fn] Crisis Group Report, Competing Visions of International Order in the South China Sea , op. cit. Hide Footnote

Duterte again proved unpredictable when in February 2020 he suddenly ordered the termination of the Visiting Forces Agreement with the U.S., apparently in retaliation for the cancellation of a U.S. visa for Ronald dela Rosa, one of his main political allies and a supporter of his anti-drug campaign. Had it been implemented, the termination, which was to take effect after six months, would have created substantive difficulties for U.S. forces present in the Philippines. [fn] “Philippines’ Duterte tells US he is scrapping troop agreement”, The Guardian , 11 February 2020. The Visiting Forces Agreement is a document laying out details of the Mutual Defence Treaty, stipulating rights and obligations for U.S. service personnel in the Philippines and rules for U.S. access to the country for military exercises and other activities. Without the Agreement, it would be “cumbersome” to make the alliance operational. Crisis Group interview, U.S. official, 21 October 2020. Hide Footnote Chinese experts interpreted the episode as a blow to Washington’s efforts to contain Beijing’s assertiveness in the South China Sea. [fn] Li Kaisheng, “Manila’s termination of military pact will upset US meddling in South China Sea”, Global Times , 13 February 2020. Hide Footnote

Overall, Duterte’s economic pivot to China has had mixed results. [fn] Crisis Group online interviews, economic experts, August and November 2020. Hide Footnote Philippine-Chinese trade ties have grown under his presidency. [fn] So has foreign direct investment, but at a rate lower than in other South East Asian countries. Crisis Group online interview, economist, 28 October 2020. Hide Footnote But China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which both governments billed as a link to Duterte’s flagship Build, Build, Build program, has not lived up to the initial fanfare. [fn] The Build, Build, Build program is an economic initiative launched under Duterte that aims to boost infrastructure across the Philippines. Hide Footnote The large infrastructure that was envisioned remains unbuilt. As of June 2021, only a handful of smaller BRI projects are under way. [fn] “Chinese investments in the Philippines”, Rappler.com, 15 September 2020. Crisis Group online interviews, academics, 6 and 19 August 2020. Hide Footnote An analyst explained: “Both China and the Philippines oversold their partnership, raising expectations for the Philippine public that were unfulfilled”. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, Alvin Camba, assistant professor, University of Denver, 13 August 2020. Hide Footnote

C. Geopolitics Come Back to the Fore

In the last two years, the geopolitics of the South China Sea dispute have become more pronounced as Beijing has pressed its claims more vigorously and ties between Manila and Washington have strengthened, against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Beyond its devastating health effects on the Philippines’ population, the pandemic also dealt a major blow to the economy, directly affecting the armed forces’ modernisation program. [fn] Michael Toole, “The Philippines passes the 2 million mark as COVID-19 cases surge in Southeast Asia”, The Conversation, 9 September 2021. Hide Footnote Although initial assessments indicated that Manila would proceed with “game changing” acquisitions such as submarines, cruise missiles and more advanced aircraft and ships, procurement has slowed as the government redirects funds to address the pandemic’s effects. [fn] Crisis Group correspondence, sources close to the process, 31 May 2021. Hide Footnote Military modernisation, while supported by the opposition, seems unlikely to make headway before the end of Duterte’s term. [fn] Apart from two Korean-built missile frigates purchased in early 2021, the items that the armed forces are procuring are primarily for counter-insurgency purposes. Hide Footnote

Meanwhile, Manila felt compelled to respond to assertive actions Beijing was taking in the South China Sea. In February 2020, the foreign ministry filed a diplomatic protest after the navy reported that a Chinese warship had shown “hostile intent” by aiming its gun control radar at a Philippine vessel. [fn] Anna Bajo, “Wescom confirms China’s ‘harassment’ vs. Philippine navy vessel in February”, GMA News, 23 April 2020. Hide Footnote In the following months, it also protested the Chinese navy’s confiscation of gear from fishermen around Masinloc, close to Scarborough Shoal, and Beijing’s announcement of new administrative units in the South China Sea. [fn] On 12 April 2020, the State Council of China announced the creation of two new districts under Sansha City prefecture, located on Woody Island in the Paracels. Hide Footnote

More consequentially, on 2 June 2020, the Philippines suspended the Visiting Forces Agreement’s cancellation that it had announced a few months earlier, citing “political and other developments in the region”. [fn] Tweet by Teodoro Locsin, @teddyboylocsin, 6:55pm, 2 June 2020. Hide Footnote The reversal was a clear sign that, while the top leadership emphasised the independence of Manila’s foreign policy, the security apparatus continued to value collaboration with the U.S., particularly as concerns about China’s grey zone infractions raised the spectre of yet more assertive actions by Beijing. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, former military regional commander, 9 September 2020. In mid-July, for instance, the Philippine military renamed its top rank designations in accordance with the U.S. system. Hide Footnote Statements by Philippine officials implied a correlation between the decision and Beijing’s actions in the South China Sea over the preceding month. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, 28 July 2020. See also Sofia Tomacruz, “Duterte halted VFA termination due to South China Sea tensions”, Rappler.com, 22 June 2020; and Darryl Esguerra, “PH envoy to US: COVID-19, South China Sea ‘developments’, reasons not to end VFA”, Inquirer , 3 June 2020. Hide Footnote

Shortly after it had suspended the Agreement’s cancellation, Manila welcomed a statement by U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo that clarified the U.S. position on the South China Sea. Notably, the statement affirmed the 2016 arbitration award and expressed support for “Southeast Asian allies and partners in protecting their sovereign rights to offshore resources”, with specific reference to the Philippines, including Scarborough and Second Thomas Shoals. [fn] “ U.S. Position on Maritime Claims in the South China Sea ”, U.S. Mission to ASEAN, 13 July 2020. Hide Footnote The thaw in U.S-Philippine relations benefited not only from the personal chemistry between Duterte and U.S. President Donald Trump, and concerns about China’s maritime actions, but also from U.S. assistance to contain the coronavirus outbreak in the islands. [fn] Crisis Group interview, Philippine official, 15 November 2020. Hide Footnote

Beijing, meanwhile, took a public relations hit in April 2020, when the Chinese embassy in Manila released a song, along with a music video, as a tribute to front-line workers trying to contain the pandemic in both countries. Filipinos criticised the song on social media for its reference to what the Chinese embassy called cooperation between “friendly neighbours across the sea”, saying China’s behaviour in the dispute belied this rhetoric. [fn] Glee Jalea, “Chinese embassy’s ‘Iisang Dagat’ tribute sparks outrage online”, CNN Philippines, 26 April 2020. Hide Footnote

Beijing’s continued activities also prompted Duterte to temper his hitherto starkly pro-Chinese public statements and instead stress Manila’s distinct position in the South China Sea dispute. [fn] In the last year of Duterte’s term, Manila remains too distracted by the pandemic and other challenges, such as natural disasters and internal conflicts, to formally overhaul its foreign policy. Manila’s unresolved dilemmas were epitomised in the wavering course regarding the anti-COVID-19 vaccination campaign, when Duterte seemed to bet on China and Russia as suppliers. The public and politicians are critical of the Sinovac deal and its perceived low effectiveness, even as Chinese (and Russian) vaccines kept the campaign afloat until the U.S. increased its vaccine shipments. “Roque turns around on finality of Sinovac deal”, Verafiles, 30 January 2021. Hide Footnote In particular, the president highlighted the arbitration award for the first time in front of an international audience at the UN General Assembly in September 2020, saying – without mentioning China – the Philippines “firmly rejects attempts to undermine it”. [fn] Statement of President Rodrigo Roa Duterte during the General Debate of the 75th Session of the UN General Assembly, 22 September 2020. Hide Footnote This unexpected shift led some analysts to believe that Duterte might recommit to the U.S. alliance. [fn] Crisis Group online interview, defence specialist, 2 September 2020. Hide Footnote Another sign of improvement in relations with the U.S. was Manila’s extension of the Visiting Forces Agreement (which it had previously slated for abrogation) for another six months on 11 November 2020 and then a third period on 14 June 2021. [fn] No major changes in the text seemed imminent and both sides were mulling over the inclusion of “implementing guidelines” to clarify ambiguous matters. Crisis Group telephone interview, diplomat, 29 May 2021. Hide Footnote On 30 July, Duterte formally restored the pact after U.S. Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin visited Manila. [fn] Manila and Washington are working on a “supplementary” agreement that is likely to tackle matters of criminal jurisdiction in cases where U.S. servicemen violate Philippine laws. Michael Punongbayan, “VFA addendum to cover US soldiers’ custody”, Philippine Star , 5 August 2021. In the run-up to the announcement, the U.S. also increased its arms sales to the Philippines. “U.S. Military Delivers Php183 Million in New Weapons and Equipment to AFP”, U.S. Embassy in the Philippines, 22 June 2021. On 24 June, the U.S. State Department approved $2.5 billion in sales of F-16 fighter aircraft, missiles and related equipment. Nick Aspinwall, “US clears F-16 sale to Philippines as South China Sea tensions brew”, The Diplomat , 30 June 2021. Hide Footnote

Relations with Washington keep warming with U.S. President Joe Biden in office, as the new administration does not seem to irritate the unpredictable Duterte. Biden’s secretary of state, Antony Blinken, reaffirmed the U.S. commitment to the alliance with the Philippines, reiterating U.S. support in case of armed confrontation in the South China Sea. [fn] Sofia Tomacruz, “New US top diplomat calls Locsin, vows support vs. China ‘pressure’”, Rappler.com, 28 January 2021. Hide Footnote Manila’s foreign secretary, Teodoro Locsin, reciprocated with optimistic remarks about the alliance. [fn] Tweet by Teodoro Locsin, @teddyboylocsin, 8:05am, 28 January 2021. Hide Footnote Joint military exercises have resumed, and the alliance received a further boost when the U.S. Marine Corps commandant, General David Berger, visited Manila in September. [fn] “US Marine Corps chief meets with Philippine counterparts in first visit since 2017”, Philippine Star , 13 September 2021. Hide Footnote