7 Steps of Writing an Excellent Academic Book Chapter

Writing is an inextricable part of an academic’s career; maintaining lab reports, writing personal statements, drafting cover letters, research proposals, the dissertation—this list goes on. However, while these are considered as essentials during any research program, writing an academic book is a milestone every writer aims to achieve. It could either be your urge of authoring a book or you may have received an invite from a publisher to write a book chapter . In both cases, most researchers find it difficult to write an academic book chapter.

The questions that may arise when you plan on writing a book chapter are:

- Where do I start from?

- How do I even do this?

- What should be the length of book chapters?

- How should I link one chapter to the following chapter?

These questions are quite common when starting with your first book chapter. In this article, we’ll discuss the steps on how to write an excellent academic book chapter.

Table of Contents

What is an Academic Book Chapter?

An academic book chapter is defined as a section, or division, of a book. These are usually separated with a chapter number or title. A chapter divides the overall book topic into topic-specific sections. Furthermore, each chapter in a book is related to the overall theme of the book.

A book chapter allows the author to divide their work in parts for readers to understand and remember it easily. Additionally, chapters help create structure in your writing for a better flow of ideas.

How Long Should a Book Chapter be?

Typically, a non-fiction book chapter should be small and must only include information related to one major idea. However, since a non-fiction /academic book is around 50,000 to 70,000 words, and each book would comprise 10-20 chapters, each book chapter’s word limit should range between 3500 and 7000 words.

While there aren’t any standard rules to follow with respect to the length of a book chapter, it may vary depending on the genre of your writing. However, it is better to refer your publisher’s guidelines and write your chapters accordingly.

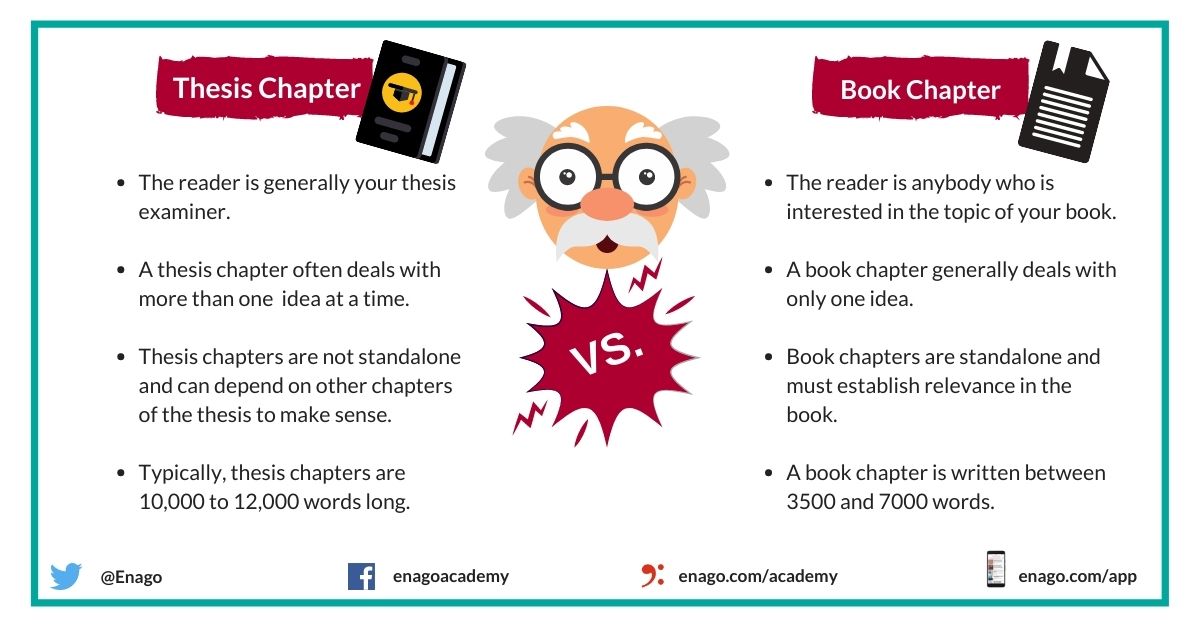

Difference between a Book Chapter and Thesis Chapter

What makes a book excellent are the book chapters that it comprises. Thus, the key to writing an excellent book is mastering the art of writing a book chapter . You’d think you could write a book easily because you’ve already written your dissertation. However, writing a book chapter is not the same as writing your thesis.

The image below shares 5 major differences between a book chapter and a thesis chapter:

How to Write a Book Chapter?

As writing a book chapter is the first milestone in your writing journey, it can be overwhelming and difficult to garner your thoughts and put them down on a sheet at once. It takes time and effort to gain momentum for accomplishing this mammoth task. However, proper planning followed by dedicated effort will make you realize that you were worrying over something trivial.

So let us make the process of writing a book chapter easier with these 7 steps.

Step 1: Collate Relevant Information

How would you even start writing a chapter if you do not have the necessary information or data? The first step even before you start writing is to review and collate all the relevant data that is necessary to formulate an informative chapter.

Since a chapter focuses on one major idea it should not include any gaps that perplexes the reader. Creating mind-maps help in linking different sources of information and compiling them to formulate a completely new chapter. As a result, you can structure your ideas to help with your analysis and see it visually. This process improves your understanding of the book’s theme. More importantly, sort the ideas into a logical order of how you should present them in your chapter. This makes it easier to write the chapter without convoluting it.

Step 2: Design the Chapter Structure

After spending hours in brainstorming ideas and understanding the fundamentals that the chapter should cover, you must create a structured outline. Furthermore, following a standard format helps you stay on track and structure your chapter fluently.

Ideally, a well-structured chapter includes the following elements:

- A title or heading

- An interesting introduction

- Main body informative paragraphs

- A summary of the chapter

- Smooth transition to the next chapter

Even so, you may not restrict yourself to following only one structure; rather, add more or less to each of your chapters depending on your genre, writing style, and requirement of the chapter to maintain the book’s overall theme. Keep only relevant content in your chapter. Avoid content that causes the reader to go off on a tangent.

Step 3: Write an Appealing Chapter Title/Heading

How often have you put a book back on the book store’s shelf right after reading its title? Didn’t even bother to read the synopsis, did you? Likewise, you may have written the most impactful chapter, but what sense would it make if its title is not interesting enough. An impactful chapter title captures the reader’s attention. It’s basically the “first sight” rule!

Your chapter’s title/heading must trigger curiosity in the reader and make them want to read and learn more. Although this is the first element of a chapter, most writers find it easier to create a title/heading after completing the chapter.

Step 4: Build an Engaging Introduction

Now that you have captured the reader’s attention with your title/heading, it has obviously increased the readers’ expectations from the content. To keep them interested in your chapter, write an introduction that keeps them hooked on. You may use a narrative approach or build a fictional plot to grab the attention of the reader. However, ensure that you do not deviate from the main context of your chapter. Finally, writing an effective introduction will help you in presenting an overview of your chapter.

Some of the tricks to follow when writing an exceptional introduction are:

- Share an anecdote

- Create a dialogue or conversation

- Include quotations

- Create a fictional plot

Step 5: Elaborate on Main Points of the Chapter

Impactful title? Checked!

Interesting introduction? Checked!

Now is the time to dive in to the details imparting section of the chapter. Expand your opening statement and begin to explain your points in detail. More importantly, leave no space for speculation in the reader’s mind.

This section should answer the following questions of the reader:

- Why has the reader chosen to read your book?

- What do they need to know?

- Are their questions and doubts being resolved with the content of your chapter?

Ensure that you build each point coherently and follow a cohesive flow. Furthermore, provide statistical data, evidence-based information, experimental data, graphical presentations, etc. You could formulate these points into 4-5 paragraphs based on the details of your chapter. To ensure you structure these details coherently across the right number of paragraphs, calculate the number of paragraphs in your text here .

Step 6: Summarize the Chapter

As impactful was the entry, so should be the exit, right? The summary is the part where you are almost done. This section is a key takeaway for your readers. So, revisit your chapter’s main content and summarize it. Since your chapter has given a lot of information, you’d want the reader to remember the gist of it as they reach the end of your chapter. Hence, writing a concise summary that constitutes the crux of your chapter is imperative.

Step 7: Add a Call-to-Action & Transition to Next Chapter

This section comes at the extreme end of the book chapter, when you ask the reader to implement the learnings from the chapter. It is a way of applying their newly acquired knowledge. In this section, you can also add a transition from your chapter to the succeeding chapter.

So would you still have jitters while writing your book chapter? Are there any other strategies or steps that you follow to write one? Let us know in the comments section below on how these steps helped you in writing a book chapter .

Thank you I have got a full lecture for sure

Thank for the encouraging words

You have demystified the act of writing a book chapter. Thank you for your efforts.

Very informative

It has really helpful for beginners like me.

Very impactful and informative. Thank you 😊

Very informative and helpful to beginners like us. Thank you.

Thanks for this very informative article

You have made writing a book chapter seem very simple. I appreciate all of your hard work.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Career Corner

- Trending Now

Recognizing the signs: A guide to overcoming academic burnout

As the sun set over the campus, casting long shadows through the library windows, Alex…

- Diversity and Inclusion

Reassessing the Lab Environment to Create an Equitable and Inclusive Space

The pursuit of scientific discovery has long been fueled by diverse minds and perspectives. Yet…

- AI in Academia

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

- Reporting Research

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without AI-assistance

Imagine you’re a scientist who just made a ground-breaking discovery! You want to share your…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

Being a Research Blogger: The art of making an impact on the academic audience with…

Statement of Purpose Vs. Personal Statement – A Guide for Early Career…

When Your Thesis Advisor Asks You to Quit

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Understanding and solving intractable resource governance problems.

- In the Press

- Conferences and Talks

- Exploring models of electronic wastes governance in the United States and Mexico: Recycling, risk and environmental justice

- The Collaborative Resource Governance Lab (CoReGovLab)

- Water Conflicts in Mexico: A Multi-Method Approach

- Past projects

- Publications and scholarly output

- Research Interests

- Higher education and academia

- Public administration, public policy and public management research

- Research-oriented blog posts

- Stuff about research methods

- Research trajectory

- Publications

- Developing a Writing Practice

- Outlining Papers

- Publishing strategies

- Writing a book manuscript

- Writing a research paper, book chapter or dissertation/thesis chapter

- Everything Notebook

- Literature Reviews

- Note-Taking Techniques

- Organization and Time Management

- Planning Methods and Approaches

- Qualitative Methods, Qualitative Research, Qualitative Analysis

- Reading Notes of Books

- Reading Strategies

- Teaching Public Policy, Public Administration and Public Management

- My Reading Notes of Books on How to Write a Doctoral Dissertation/How to Conduct PhD Research

- Writing a Thesis (Undergraduate or Masters) or a Dissertation (PhD)

- Reading strategies for undergraduates

- Social Media in Academia

- Resources for Job Seekers in the Academic Market

- Writing Groups and Retreats

- Regional Development (Fall 2015)

- State and Local Government (Fall 2015)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2016)

- Regional Development (Fall 2016)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2018)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2019)

- Public Policy Analysis (Spring 2016)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Summer Session 2011)

- POLI 352 Comparative Politics of Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 2)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Term 1)

- POLI 332 Latin American Environmental Politics (Term 2, Spring 2012)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

How to write a book chapter

I was asked by Dr. Joanna Brown for guidance on how to write a book chapter. I wouldn’t say I’m the ideal person for this task, but since I have published many of these for several edited collections , I think I can offer some advice.

I’ve got a few single-authored chapters on the go for three books at the moment (one on bottled water in the context of a human right to water, one on ethnography as a research method in comparative policy analysis, and one in press on national policy styles ), and thus I wanted to share my experience writing these.

My relationship with writing chapters for someone else’s edited volume is simultaneously love-and-hate, as people who read my blog regularly may remember .

@raulpacheco any advice for writing an academic book chapter? I'm struggling with some imposter syndrome. — Dr. Joanna (@joannawbrownphd) July 3, 2018

The value that different institutions place on book chapters varies widely. My own institution prefers journal articles, but as I’ve said before, I have participated in edited collections because I believe in the project, and also because these are usually collective projects I’m interested in undertaking. I’ve published book chapters in both Spanish and English, and I’ve also edited books as well, so I’m fond of the model. You should, nonetheless, consider the pros and cons of writing a book chapter.

First of all, book chapters are different from journal articles as many of these aren’t peer reviewed and therefore aren’t subject to as many changes and corrections as you could expect from articles. I will fully admit having published peer-reviewed book chapters that these are as much of a nightmare as journal article manuscripts. I have one particularly awful experience (which isn’t over yet!) in mind.

But the most important element that an author needs to keep thinking about when writing a book chapter, in my view, is how your chapter contributes to the overall Throughline of the book (I’ve mentioned The Throughline previously – or as Scandinavian authors call it, The Red Thread ). I’ve also emphasized the importance of demonstrating cohesiveness and coherence throughout an edited collection, as the editors of Untapped did in their edited volume on the sociology of beer .

With Untapped, Chapman and coauthors explore the question of "what is sociological about beer?" pic.twitter.com/tVcf069LRm — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2018

This sample chapter on how to write books actually provides a great example of how to write a book chapter . Normally, I would create an outline of the paper ( this blog post of mine will tell you two methods to create outlines ), then follow a sequential process to create the full paper ( my post on 8 sequential steps may be helpful here ).

More than anything, I do try really hard to use headings to guide the global argument of the chapter. The outline/sequence looks something like this:

- Introduction. – outline of questions or topics to tackle throughout the chapter, and description of how the chapter will deal with them.

- Topic 1 – answer to question 1.

- Topic 2 – answer to question 2.

- Topic N – answer to question N.

- Discussion/synthesis. – how it all integrates and relates to the overall book.

- Conclusions, limitations and future work.

- References.

As I write my chapter, I make sure to link its content with other chapters in the edited volume . This may be a bit tricky because of how editors have timed contributions. Sometimes they don’t have all the chapters readily available to be shared across authors. But I’ve found that normally they do, and so they’re willing to share across all authors.

This guideline to writing chapters may also be helpful. It’s also quite important that you follow both the press and the editors’ guide (style, punctuation, citation formatting, etc.). But more than anything, I strongly believe that the best approach to writing a book chapter is to think of it as a way to present a series of thoughts in a cohesive manner that doesn’t necessarily equal a journal article. Yes, there may be empirical claims presented, and yes, there should probably some theoretical advancement in there, but again, it’s NOT a journal article.

Hope this post helps those of you writing a book chapter. If you want to read some of mine, you can download some of them here or here (Academia.Edu) or here (ResearchGate).

You can share this blog post on the following social networks by clicking on their icon.

Posted in academia , research , writing .

Tagged with AcWri , book chapters , writing .

12 comments

By Raul Pacheco-Vega – July 11, 2018

12 Responses

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post .

Can I reuse my own published papers in writing book chapters?

Reuse per se, perhaps not, republish maybe, with caveats, but you can use some text, yes.

In the book chapters, do we have to give results or only survey of others works will do ?

That depends on you and what the book editor expects!

Thank you, Sir. That was helpful.

As a research scholar I want to write a book chapter instead of writing a review paper. Can I do that? Do I need any special permission to write a book chapter?

This reminds me of the quote… “Any fool can make something complicated. It takes a genius to make it simple.” Thanks for posting this.

No special permission!

This is very useful. Thanks Raul.

will the book chapters will have references in the same manner as in manuscripts of journal

In book chapters, we have to do new research like (journal article ) or illustrate our ideas with already published work?

Leave a Reply Cancel Some HTML is OK

Name (required)

Email (required, but never shared)

or, reply to this post via trackback .

About Raul Pacheco-Vega, PhD

Find me online.

My Research Output

- Google Scholar Profile

- Academia.Edu

- ResearchGate

My Social Networks

- Polycentricity Network

Recent Posts

- “State-Sponsored Activism: Bureaucrats and Social Movements in Brazil” – Jessica Rich – my reading notes

- Reading Like a Writer – Francine Prose – my reading notes

- Using the Pacheco-Vega workflows and frameworks to write and/or revise a scholarly book

- On framing, the value of narrative and storytelling in scholarly research, and the importance of asking the “what is this a story of” question

- The Abstract Decomposition Matrix Technique to find a gap in the literature

Recent Comments

- Hazera on On framing, the value of narrative and storytelling in scholarly research, and the importance of asking the “what is this a story of” question

- Kipi Fidelis on A sequential framework for teaching how to write good research questions

- Razib Paul on On framing, the value of narrative and storytelling in scholarly research, and the importance of asking the “what is this a story of” question

- Jonathan Wilcox on An improved version of the Drafts Review Matrix – responding to reviewers and editors’ comments

- Catherine Franz on What’s the difference between the Everything Notebook and the Commonplace Book?

Follow me on Twitter:

Proudly powered by WordPress and Carrington .

Carrington Theme by Crowd Favorite

Publishing Research: Book Chapters and Books

Cite this chapter.

- Lindy Woodrow 2

1704 Accesses

1 Citations

Sometimes researchers decide to publish their work in a book chapter in an edited volume, or they may decide to write a monograph or another type of book. There are advantages and disadvantages in choosing to publish in book form. This section discusses the merits of publishing book chapters and books with a section on writing monographs based on PhD theses.

- Journal Article

- Book Chapter

- Apply Linguistics

- Content Explicit

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Sydney, Australia

Lindy Woodrow

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© 2014 Lindy Woodrow

About this chapter

Woodrow, L. (2014). Publishing Research: Book Chapters and Books. In: Writing about Quantitative Research in Applied Linguistics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230369955_14

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230369955_14

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-0-230-36997-9

Online ISBN : 978-0-230-36995-5

eBook Packages : Palgrave Language & Linguistics Collection Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Resources Research Proposals --> Industrial Updates Webinar - Research Meet

- Countries-Served

- Add-on-services

Text particle

feel free to change the value of the variable "message"

How to write an Excellent Academic Book Chapter?

What is an Academic Book Chapter?

A book chapter is a portion or division of a book that focuses on a research topic. It is an expert collection that offers a balanced view and viewpoint on research that is often dispersed throughout journals and other publications. A book chapter is more widely focussed than a journal article and generally has a higher educational value since book chapters are frequently included in undergraduate and postgraduate students’ reading lists.

Calls for chapter proposals can be found online. In many circumstances, though, a researcher is commissioned by an editor or a publisher. This is why attending conferences and networking with research organizations in your profession are crucial ways to expand your network. Depending on the publisher’s or funding criteria, the commissioned book chapter might have open or paid access.

A chapter is typically commissioned with a due date of six, nine, or twelve months. Once the text has been agreed upon, it is ideal to continue working on it on a regular basis since writing abilities improve with practice. It is also critical to continue reading publications in the subject, in order to stay up to speed on new discoveries and to refresh your reference list with new contributions.

It is critical to write in simple language, eliminate jargon, and explain topics properly so that your work is understandable, particularly if the book is intended at students. Seek advice and input from senior academics if at all feasible. They may advise you on how to present your ideas and point out any gaps or references you should include.

Benefits of Publishing a Book Chapter in an Academic Journal

Publishing a book chapter might help you establish your credibility as an author and expert in your industry. There are further benefits:

- Academics frequently read chapter books to stay current and for educational purposes, thus your work may be mentioned in essays and dissertations.

- A chapter in a well-edited collection shows an employment panel or a publisher that your work has been sought after by leading academics and that you have the potential to write a book.

- A book chapter can be used to elaborate on a topic presented in a journal article, but you must obtain permission from the journal’s editor to cite parts from the article if it is behind a paywall.

- You do not need to persuade readers of the significance of your work. The editors will address this in the book’s foreword. This will empower you to write with greater confidence and creativity.

A book chapter allows you to focus on interested readers from a diverse range of backgrounds, rather than merely reviewers and academic colleagues. It assists you in developing strong writing abilities that may lead to the completion of a whole book as you gain confidence and improve in your academic career.

Steps to write a Book Chapter

Step 1: Gather Important Data

- Even before you begin writing, go through and collect all of the key facts that will be needed to create an informative chapter. Because a chapter concentrates on one important concept, there should be no gaps that confuse the reader.

- Making mind maps aids in connecting disparate sources of knowledge and assembling them to produce an entirely new chapter. As a consequence, you may organize your ideas to aid in your analysis and visualize them. This procedure increases your comprehension of the book’s concept.

- More crucially, arrange the concepts in a logical manner for presentation in your chapter. This makes it easy to compose the chapter without making it too complicated.

Step 2: Create the chapter structure .

After hours of brainstorming ideas and comprehending the principles that the chapter should include, you must build an organized framework. Furthermore, sticking to a regular format allows you to stay on track and arrange your chapter fluently.

Here are the elements of a chapter structure:

- A title or headline

- An introduction that hooks

- Body paragraphs that provide further details

- A recap, or summary, of the chapter

- A transition to the next chapter

While you can include more or less to each chapter based on your genre, writing style, and requirements, it is critical that all of your chapter contents have comparable points or bits of information connected to your main topic. Remove any contents that do not suit the concept of your chapter.

Step 3: Create a catchy chapter title or headline.

An impactful chapter title captures the reader’s attention. It’s basically the “first sight” rule!. Your chapter’s title/heading must trigger curiosity in the reader and make them want to read and learn more. Although this is the first element of a chapter, most writers find it easier to create a title/heading after completing the chapter.

Here are three types of headlines you can write:

- Use the “How to…” approach

- Use a phrase or belief statement

- Present it as a question

Step 4: Build an Engaging Introduction

Now that you’ve aroused the reader’s interest with your title/heading, the reader’s expectations for the content have plainly risen. To keep people engaged in your chapter, develop an interesting introduction. To capture the reader’s interest, you might employ a narrative method or create a fictitious scenario. However, avoid deviating from the main context of your chapter. Finally, crafting a strong opening will assist you in providing a summary of your chapter.

Some tips to remember while creating an outstanding introduction include:

- Share a personal story

- Show a conversation or dialogue

- Add powerful quotes

- Add shocking statistics

Step 5: Expand your story with main points

Now is the time to go into the chapter’s detail-instruction portion. Extend your introductory statement and start explaining your views in depth. More crucial, leave no room for the reader’s imagination.

This section should answer the following reader questions:

- Why did the reader decide to read your book?

- What do they need to know?

- Is the content of your chapter resolving their issues and doubts?

Make careful you establish each argument logically and in a logical order. Also, include statistical data, evidence-based material, experimental data, graphical displays, and so on. Based on the specifics of your chapter, you might compress these points into 4-5 paragraphs.

Step 6: Write a summary of the book chapter

The departure should be as powerful as the entering, right? The summary is the section when you are nearly finished. This part is essential for your viewers to understand. So, go back and summarize the important points of your chapter. Because your chapter has a lot of information, you’d like the reader to remember the gist of it by the time they get to the finish. As a result, it is critical to write a brief summary that summarizes the main point of your chapter.

Here’s how to create a book chapter summary:

- Read through the chapter and make a list of any main points or key takeaways.

- Make a note of each essential point or takeaway.

- Write a summary of each point.

- Narrow it down to one or two phrases for each point.

- Consolidate all of your summary arguments into a single paragraph.

- For each new point, use transition words such as “first,” “next,” or “then.”

Step 7: Add a Call-to-Action & Transition to Next Chapter

A call-to-action (CTA) is when you invite the reader to take action by implementing and applying what they have learnt in some way. In a short, ask the reader to take action.

What action do you want the reader to do next? At the end of your chapter, tell them what you want them to think, act, or do. It might be as simple as providing a few open-ended questions for the readers to consider.

Here are some ideas for including a call to action for your reader:

- Include reflection questions such as “So, what’s one AHA! moment you had while reading this chapter?”

- Include action steps: “What is one little action you can do today as a result of reading this chapter?”

- Signup to my email list: “Are you still having trouble with this (chapter problem)?” Sign up for my email list to get additional insights and techniques.”

- Contact us: “If this (chapter difficulty) is a recurring issue for you, please do not hesitate to contact us.” (Include your email address or other contact information)

- Purchase: “If you want to learn more about (chapter topic), try purchasing these other books that focus on X.”

After you’ve placed your call to action, you may prepare your reader for the following chapter with a short transition. Transitioning your reader to the next chapter tickles their interest and completely closes the loop on the information they just read. You may easily add some transition words and write a 1-2 sentence that summarizes the following chapter. Then you may finish the chapter and begin the chapter writing process all over again!

Are you ready to begin writing your fantastic chapter RIGHT NOW? By following these techniques, you will be able to write effective chapters with ease.

We can assist you if you are ready to begin (or finish) and publish your book!

https://sciendo.com/news/writing-an-academic-book-chapter

https://selfpublishing.com/how-to-write-a-book-chapter/

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

Preparing your manuscript

As you write, please follow the guidelines below to create a well-structured, discoverable, and engaging publication.

Structure

A clear structure enhances readability in both print and digital formats. In digital publications, the text structure affects how well it displays. The key is consistency in the organizational logic, at every level, from overarching sections through to granular headings.

Parts and/or sections

- When grouping chapters into parts or sections, be consistent. Do not create any ‘orphans’ which sit outside of a part or section. If you envision any free-standing chapters, such as an introduction, please discuss the idea with your OUP editorial contact.

- Use descriptive titles, rather than generic names, to identify all parts or sections (e.g. a book on Miguel de Cervantes would include ‘Part 1: Don Quixote and ‘Part 2: Novelas ejemplares’, rather than ‘Part 1’ or ‘Part 2’).

- Do not use blank part-opener pages, which appear as blank screens on digital devices and are confusing to readers. Adding a useful element, such as a brief table of contents, can avoid the problem.

Chapters

- If you split any chapters into ‘sub-chapters’, please do it for all chapters. If some chapters are broken into parts, then all the chapters in a multi-chapter book must be.

- Be consistent with features. If you open a chapter with a mini table of contents, use it in every chapter.

- Write chapters to similar lengths.

- Use headings consistently within and across chapters. For example, if you open and close with ‘Overview’ and ‘Conclusion’, follow this structure in all chapters.

- Chapter titles should be unambiguous and informative. ‘Chapter One: The archives of La Mancha’ is better than ‘Chapter One: Introduction’.

- Avoid extensive passages of unbroken text, long headings, and large, complex tables. Your work will be read on hand-held devices. Lengthy formats, which can be difficult to read on smaller screens, will lose your reader’s attention.

Appendices

- Number appendices separately. Name them with descriptive headings that inform and engage readers.

Headings

Headings are an essential element for making your work readable and accessible. Note the following when composing headings:

- Use headings consistently across your work. If ‘Overview’ is a level 1 heading in chapter 1, it should be a level 1 heading in all chapters.

- Headings should divide text into digestible chunks.

- Open every chapter with a heading, so that no text is left sitting outside the heading structure.

- ‘Nest’ one heading inside another logically. A level 1 heading is always followed by level 2 (don’t jump to a level 3 heading).

- Keep headings concise, so they can work in print and digital format (in the latter, long headings are cumbersome).

- Avoid the inclusion of references, footnotes, or ‘call-outs’ to figures, tables, or boxes in headings.

Cross references

The impact of cross-referencing within your work will have a greater value for your readers if you:

- Point to a specific target in the text, such as a heading, figure, table, box, or paragraph number (for practitioner law authors). In digital formats, cross-referencing links precisely to the target point in the text.

- Avoid using ‘see above’, ‘see below’, or using a page number to identify text that has a cross reference. Pagination may vary in responsive design formats (for hand-held devices) and some digital products.

- Always include a call-out, such as ‘see Figure 1.1’ when cross-referencing non-textual material. In digital formats, use linking to direct readers to the referenced material.

- Do not use specific references to any one format. Any references to material elsewhere in your work should make sense to readers, whatever device or format they are using to access the information.

References

References to the works of other authors are important to acknowledge their contributions to the development of your work and advance scholarly discourse. To give proper credit, make sure that all references are complete and follow a consistent reference style. Avoid print specific terms and conventions (e.g. ‘op. cit.’) that don’t work for reference linking in digital versions.

House style

Authors should follow OUP’s ‘ House style ’ for spelling, punctuation, text formatting, abbreviations, acceptable language, numbers, dates, and units of measure. Please compare your manuscript carefully against the style guide before you submit it. This will save time and effort during the production process.

Your OUP editorial contact will provide you with any additional subject- or series-specific guidelines that you need to follow.

Non-textual material

Non-textual material refers to artwork (e.g. line drawings, illustrations, halftones, or photographs), tables, boxes, or equations. Distinguishing between them is important in digital formatting. The following groups non-textual material feature-types with similar requirements:

- Figures : line drawings, photographs, diagrams, graphs

- Boxes : extracts, case studies, lists, vignettes, material without columns

- Tables : material with columns

There are other factors to consider when including non-textual material:

- Copyright : Any third-party material that you wish to reproduce must be cleared for copyright permissions. See more on this in ‘ Copyright of third-party material ’.

- Call-outs : Each item of non-textual material must be labeled (e.g. ‘See Figure 1.1’) to serve as anchor text for hyperlinks.

- Placement indicators : These are needed (in addition to call-outs) for figures and complex tables that are supplied in separate documents. The placement indicator is an instruction (placed in angle brackets) for the typesetter that indicates where to set the feature (e.g. <Insert Figure 3.2 near here>). It should always appear after the call-out. Please note that the figure may not appear exactly where you request.

- Numbers and captions : Include a figure number and caption beneath the placement indicator (or list all captions) for each chapter in a separate document. Use a naming scheme identifying the chapter and its sequence of figures (e.g. ‘Figure 1.4 is the fourth figure in Chapter 1’), followed by the caption (e.g. ‘Figure 1.1 A Chihuahua (left) and a Great Dane (right). Dogs have the widest range of body sizes among mammals’).

- Boxes : Don’t add design formatting to the boxes features in your manuscript. Please supply as text only, clearly labelled to indicate placement (e.g. <start of box>, <end of box>).

- for photographs , 300 dpi at 4 × 6 inches / 10mm × 15mm

- for line art , 600–1200 dpi at 4 × 6 inches / 10mm × 15mm.

Copyright of third-party material

Your publishing agreement will state whether you or OUP are responsible for obtaining permission to reuse copyright material in your work (including epigraphs). Regardless of who is responsible, it is a good idea to follow these best practices:

- Start early : Failure to obtain permission to use copyrighted material may significantly affect your title’s content and publication schedule.

- Licences : When you submit your manuscript, please include any licences already obtained, to assist your OUP editorial contact in determining which permissions are needed or granted.

- Open Access : If your final product will be Open Access, highlight this when requesting permissions—it may impact a copyright holder’s decision.

- Formats : Print and electronic

- Distribution : Worldwide

- English

- up to five languages

- all language rights worldwide

- Duration : Life of the edition

- Final note : Formal permission is needed to reproduce any material that is under copyright. Your OUP editorial contact cannot begin the production process until all copyright permissions are in place and documented.

Find out more with our Permissions Guidelines .

Abstracts and keywords

Abstracts and keywords are used to describe your work and ensure that it is fully searchable and discoverable online. For these reasons, it is very important for you to include abstracts and keywords when you submit your manuscript.

Abstracts

Abstracts provide potential readers with a quick description of the work so they can decide whether a book or chapter is relevant to their needs – they are the online equivalent of the blurb on the back of a book.

- The first sentence is the most important. Somebody looking for information quickly may not read beyond the first sentence, so it must clearly and concisely represent the key topics of the book or chapter it is describing.

- The abstract should start with the title of the work in question (whether a chapter or whole book). The remaining text should give an overview of the content in more detail.

- Use short, clear sentences and specific terminology.

- The information and words in the abstract are used by search engines to optimize discovery.

- If a term is known by an abbreviation or acronym, include both the long- and short-form names. For example, ‘cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)’, or ‘deep vein thrombosis (DVT)’.

- Abstracts are needed for the whole book, as well as one for each chapter.

- Abstracts should be between 100 and 250 words.

Keywords

Keywords should reflect the content of the work in individual words or short, recognizable phrases (fewer than three words). These will be used alongside the abstract to facilitate searching and indexing.

- book – five to ten keywords

- chapter – five to ten keywords

- The basic form of the keyword should be used (e.g. singular nouns, infinitive verbs).

- If an abbreviation is more familiar to the readership, it is acceptable to not include the long-form name in the keywords (e.g. ‘DNA’, rather than ‘deoxyribonucleic acid’). However, in most cases it is advisable to use both short- and long-form terms as separate keywords.

- Use of keywords needs to be consistent between chapters, including the use of synonyms, commercial or generic drug names, Latin, medical, or common terms. For edited works (i.e. those with multiple contributors), enforcing consistency is the responsibility of the volume editor.

- Keywords should also appear in the respective abstracts.

Ready for the next step?

To put your manuscript in final form, you must adhere to OUP’s preparation guidelines. To avoid unnecessary steps, please review it carefully before submitting a manuscript to your OUP editorial contact. OUP considers the submitted manuscript to be final; you will not be able to make changes during the production process other than fixing typos and factual and grammatical errors.

Your OUP editorial contact will review your manuscript to make sure it is in final form before moving it along the pipeline. Find out what’s involved in the production workflow in the section on ‘ Submitting your manuscript .’

Related information

- Submitting your manuscript

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Journals, books & databases

Prepare & submit a manuscript.

Guidelines for book editors, book authors and chapter authors

The following information gives advice and instructions on preparing a chapter or book and submitting it to us.

It is important that you adhere to the information on this page to ensure your manuscript is prepared and submitted to us correctly so that we are able to process and publish the book efficiently and on time.

Please ensure that you also read the specific instructions for your book type in addition to the general instructions below.

On this page

Format & layout Templates & sample layouts Submitting a manuscript

Guidelines for specific book types

Edited books Authored books Specialist periodical reports Conference proceedings

Format & layout

- The manuscript should be prepared in Microsoft Word. If you want to use a different application, please contact us to discuss this first.

- Text should use 2.0pt line-spacing.

- Punctuation and spelling must follow standard English practice. The use of either British or American English is acceptable, but must be used consistently.

- Standard IUPAC nomenclature must be used.

- SI units and symbols must be used.

- Abbreviations must be defined at first mention in the chapter and abbreviated thereafter. A list of abbreviations may be provided at the end of the chapter if necessary.

Numbers with five or more digits should have spaces every three digits (eg 10 000, 2 000 000 – commas, eg 10,000, should not be used).

Units should be presented in inverse style (eg m s -1 and not m/s).

Chapter abstract

Each chapter will need a chapter abstract. The abstract is very important in promoting the book content. The abstract:

- should be a single paragraph of 50–200 words, briefly summarising the chapter

- will be present only in the eBook version of the book, and not the print book (with the exception of the Issues in Environment Science and Technology series and some specialist periodical reports)

- must not contain any reference citations, figures or footnotes

- The chapter text should be divided into sections with headings, as appropriate.

- All main words within a heading should be capitalised.

- No full point is needed at the end of a heading.

- Acknowledgement and reference sections should be at the end of the chapter, and these headings are not numbered.

- Headings should be numbered as follows (where X is the chapter number)*.

- X Chapter Title

- X.1 Main Section Heading

- X.1.1 Sub Section Heading

- X.1.1.1 Lower Sub Section Heading

- Figures should be supplied as TIFF or EPS files, with a resolution of 600 dpi or greater and at a final size of 20 x 12 cm.

- Photographs should be provided at the best resolution available (minimum 600 dpi) as TIFF, PDF or JPEG files.

- Figures should be supplied ready for printing, without further retouching or redrawing.

- Figures should be adequately labelled, and this must remain legible after reduction.

- Information not necessary to the discussion – for example, solvents or temperatures – should be omitted from legends.

- Avoid using long, complicated schemes or large figures as these may end up some distance from the textual discussion.

- Over-large schemes or blocks of structures will be reduced to fit the page so you will need to ensure that detail is not lost in reduction – for example, make sure that lines are thick enough to be visible after reduction, and only label significant atoms in ORTEP-style diagrams.

- Figures must be cited in the text. The recommended location of a figure to appear should be indicated as follows: [Figure X.1 near here]

- Figures taken from internet sites are not usually of reproducible quality, and may also be copyright protected; the original authors should be contacted for a suitable file and permission.

- Figures should all be submitted as separate files and not embedded in the typescript (with the exception of ChemDraw files).

Chemical structures & schemes

- Structures should be supplied as ChemDraw files.

- Structural formulae and reaction schemes should be named Scheme X.1, X.2, etc, and must be cited in the text*.

- The approximate positions in the text should be clearly indicated as follows: [Scheme X.2 near here]

- Recommended guidelines for drawing structures as as follows.

- Chain bond angle = 120°

- Fixed bond angle = 15°

- Bond length = 0.43 cm or 12.2 pt

- Bond width = 0.016 cm or 0.5 pt

- Bold bond width = 0.056 cm or 1.6 pt

- Double bond space = 20% of bond length

- Stereo bond width = 0.056 cm or 1.6 pt

- Hash spacing = 0.062 cm or 1.8 pt

- Captions/atom labels = Arial, 7 pt

Colour figures

Your contract will state whether the use of colour is allowed in the printed book or not. The use of colour figures will be considered only where scientifically necessary.

In the eBook version, any figures supplied in colour will appear in colour, regardless of whether the printed book is in colour or black and white. However, the same figure captions will be used in both the print and electronic version so refrain from mentioning colour in the caption.

- Tables should be supplied in Word format.

- Do not supply tables as image files or in Excel or PowerPoint.

- Tables should be single-line spaced.

- Footnotes in tables should be self-contained, labelled with superior lower-case letters, and listed as a block of text beneath the table.

- The table must be cited in the text.

- The approximate location of a table to appear should be indicated as follows: [Table X.5 near here]

- All figures and tables should have a caption.

- Items should be numbered as X.1, X.2, etc consecutively throughout the chapter*.

- Items should be referred to by their number in the text. Do not use phrases such as 'in the figure above' as the final placement of items may change during typesetting.

- If a figure has been previously published, the correct copyright information must be included in the caption as stipulated by the copyright holder.

- When writing the caption for a figure, please bear in mind that a figure may be black and white in the print book but appear in the electronic book in colour, so the caption must make sense for both situations. Your contract will state if the use of colour is allowed in the printed book or not.

- A separate list of all figure and table captions should appear at the end of the main text document.

- These should be set in Mathtype (or Word Equation Editor, where Mathtype is unavailable).

- They should be displayed on a separate line in the main text.

- They should be numbered consecutively throughout each chapter ((X.1), (X.2) etc) in parentheses at the right-hand side of the page*.

- Symbols for variables and physical constants should be italicised.

- Matrices and vectors should appear in bold.

- References should be superscripted in the text (for example, one day. 36 The next…).

- CASSI Journal abbreviations should be used.

- For authors using EndNote, an EndNote style file is available in Templates & sample documents .

- A list of references in numerical order (following the Vancouver system) should appear at the end of the chapter. References should only appear once in the list. If the same source is cited more than once the reference number should be repeated.

- Books in the Issues in Toxicology series must also include the full article title and the full page range in the reference lists.

- References supplied in the Harvard (author/date) system will not be accepted. Please note that the Advances in Chemistry Education series is an exception to this rule.

Journal articles

A. Name, B. Name and C. Name, Journal Title , year, volume , first page.

When page numbers are not yet known, articles should be cited by DOI (Digital Object Identifier) – for example, T. J. Hebden, R. R. Schrock, M. K. Takase and P. Müller, Chem. Commun ., 2012, DOI: 10.1039/C2CC17634C.

For books in the Issues in Toxicology series, you must also include the full article title and the complete page range.

A. Name, B. Name and C. Name, Book Title , Publisher, Publisher's Location, edition, year. For example, S. T. Beckett, Science of Chocolate , Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, 2000.

If you are referencing published conference proceedings, these should be cited as for a book.

Book chapters

A. Name, in Book Title , ed. Editor Name(s), Publisher, Publisher Location, edition, year, chapter, pages.

The ‘ed.’ in the example above stands for ‘edited by’. If the book has no editors this should be left out.

A. Name, PhD thesis, University Name, year.

Lectures, meetings & conferences

A. Name, presented in part at Conference Title, Place, Month, year.

Reference to unpublished material

You should not reference unpublished work without the permission of those who completed the work.

For material accepted for publication, but not yet published: A. Name, Journal Title , in press.

For material submitted for publication, but not yet accepted: A. Name, Journal Title , submitted. For material that has yet to be submitted for publication: A. Name, unpublished work.

Online resources (including databases, websites & wikis)

Name of resource, URL, (accessed date).

Please note the most important information to include is the URL and the date accessed. For example, The Merck Index Online, http://www.rsc.org/Merck-Index/monograph/mono1500000841, (accessed January 2016).

Preprint servers (for example, arXiv)

For example: V. Krstic and M. Glerup, 2006, arXiv:cond-mat/0601513.

The name of the patentee must be given. For example, A. Name, Br. Pat. , 123 456, 2016. B. Name, US Pat ., 1 234 567, 2015.