- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of literature

Examples of literature in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'literature.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Middle English, from Anglo-French, from Latin litteratura writing, grammar, learning, from litteratus

15th century, in the meaning defined at sense 4

Phrases Containing literature

- gray literature

Articles Related to literature

Famous Novels, Last Lines

Needless to say, spoiler alert.

New Adventures in 'Cli-Fi'

Taking the temperature of a literary genre.

Trending: 'Literature' As Bob Dylan...

Trending: 'Literature' As Bob Dylan Sees It

We know how the Nobel Prize committee defines literature, but how does the dictionary?

Dictionary Entries Near literature

literature search

Cite this Entry

“Literature.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/literature. Accessed 10 Apr. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of literature, more from merriam-webster on literature.

Nglish: Translation of literature for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of literature for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about literature

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, more commonly mispronounced words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - apr. 5, 12 bird names that sound like compliments, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, games & quizzes.

What is Syntax? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Syntax definition.

Syntax (SIN-tacks), from the ancient Greek for “arrangement,” refers to the way a writer or speaker chooses to order their words. It’s an aspect of grammar, a general term for all the rules and best practices for effective writing.

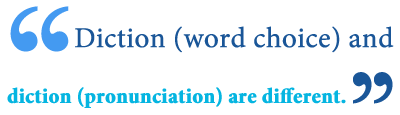

Syntax and Diction

These are both components of grammar; where syntax is the order of words, diction refers to the words themselves. Both the specific words a writer chooses and the order they choose to put them in impact the way their writing is understood.

Here are two sentences with the same diction but different syntax:

- “Georgia excitedly related the puppy story while we drank coffee.”

- “While we drank coffee, Georgia related the puppy story excitedly.”

Based on the organization, the information relayed can have different impacts. Because the first sentence ends on the coffee drinking, it reads as if that action is what the writer wants to put the focus on. In the second sentence, the words are rearranged so that the sentence ends with the puppy story being told. Thus, the emphasis is put on the storytelling; one might even expect to hear the actual story after this sentence.

Here are two sentences with different diction but similar syntax:

- “The distracted driver parked his car a little crookedly.”

- “The obnoxious driver parked his car haphazardly.”

The sentences describe the same scene with nearly identical syntax, but because of the diction, they give two different impressions. The first sentence is more forgiving in tone than the second one.

Syntax, Active Voice, and Passive Voice

Syntax is what helps determine whether something is written in active voice or passive voice .

With active voice, the subject of a sentence performs an action on an object. For example, in “The parents left their children with a babysitter,” the subject The parents perform the action left on the object their children . In passive voice, the object comes first; “The children were left with a babysitter by their parents.” Typically, writers use active voice because it’s considered the stronger, clearer option. However, there are certain reasons (primarily stylistic) why a writer may choose to write in passive voice.

Examples of Syntax in Literature

1. William Shakespeare, Henry V

Shakespeare frequently wrote in passive voce, as he does here:

It was our selfe thou didst abuse.

Elizabethan English allowed for more syntactic leeway than the modern ear would deem appropriate, and Shakespeare took full advantage of this. This could have been to facilitate rhyme or meter , two poetic devices that nearly all of his work employed, or just to make his words more memorable.

2. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “Snowflakes”

Periodic sentences, which intentionally place the main point at the end of the sentence, were popular during Longfellow’s time. Here, he utilizes this syntactic technique to create tension:

Out of the bosom of the Air,

Out of the cloud-folds of her garments shaken,

Over the woodlands brown and bare,

Over the harvest-fields forsaken,

Silent, and soft, and slow

Descends the snow.

3. Thylias Moss, “The Culture of Glass”

Contemporary poetry tends to be more conversational, often flowing into stream of consciousness, so it tends to use more informal syntax. Here, Moss makes frequent use of passive voice:

The future of fortunes is manufactured revelation

of a snow globe: when the right someone gets his hands

on such a world, that world is shaken to pieces, the glass

is tapped in the aquarium, semitransparent arowanas remain

inexplicable, a tapper’s desire breaks out: oh to become glass,

Further Resources on Syntax

The Frankfurt International School offers a guide on English syntax .

ThoughtCo offers a similar analysis of syntax.

Related Terms

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Grammar Coach ™

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

writings in which expression and form, in connection with ideas of permanent and universal interest, are characteristic or essential features, as poetry, novels, history, biography, and essays.

the entire body of writings of a specific language, period, people, etc.: the literature of England.

the writings dealing with a particular subject: the literature of ornithology.

the profession of a writer or author.

literary work or production.

any kind of printed material, as circulars, leaflets, or handbills: literature describing company products.

Archaic . polite learning; literary culture; appreciation of letters and books.

Origin of literature

Synonym study for literature, other words from literature.

- pre·lit·er·a·ture, noun

Words Nearby literature

Dictionary.com Unabridged Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2024

How to use literature in a sentence

If you want to understand the flamboyant family of objects that make up our solar system—from puny, sputtering comets to tremendous, ringed planets—you could start by immersing yourself in the technical terms that fill the scientific literature .

Poway Unified anticipates bringing forward two new courses – ethnic studies and ethnic literature – to the school board for review, said Christine Paik, a spokeswoman for the district.

The book she completed after that trip, Coming of Age in Samoa, published in 1928, would be hailed as a classic in the literature on sexuality and adolescence.

He also told Chemistry World he envisages the robots eventually being able to analyze the scientific literature to better guide their experiments.

Research also suggests that reading literature may help increase empathy and understanding of others’ experiences, potentially spurring better real-world behavior.

The research literature , too, asks these questions, and not without reason.

She wanted to know what happened over five years, or even 10, but the scientific literature had little to offer.

The religion shaped all facets of life: art, medicine, literature , and even dynastic politics.

Speaking of the literature you love, the Bloomsbury writers crop up in your collection repeatedly.

literature in the 14th century, Strohm points out, was an intimate, interactive affair.

All along the highways and by-paths of our literature we encounter much that pertains to this "queen of plants."

There cannot be many persons in the world who keep up with the whole range of musical literature as he does.

In early English literature there was at one time a tendency to ascribe to Solomon various proverbs not in the Bible.

He was deeply versed in Saxon literature and published a work on the antiquity of the English church.

Such unromantic literature as Acts of Parliament had not, it may be supposed, up to this, formed part of my mental pabulum.

British Dictionary definitions for literature

/ ( ˈlɪtərɪtʃə , ˈlɪtrɪ- ) /

written material such as poetry, novels, essays, etc, esp works of imagination characterized by excellence of style and expression and by themes of general or enduring interest

the body of written work of a particular culture or people : Scandinavian literature

written or printed matter of a particular type or on a particular subject : scientific literature ; the literature of the violin

printed material giving a particular type of information : sales literature

the art or profession of a writer

obsolete learning

Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Grammar in Literature

A Text-based Guide for Students

- © 2022

- Susan Lavender 0 ,

- Stavroula Varella 1

International English, University of Chichester, Chichester, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

School of Education, Communication and Society, King’s College London, London, UK

Explores creative use of grammar through in-depth analysis of real texts

Provides interactive writing tasks for seminar and workshop use

Includes a full answer key and glossary

2970 Accesses

4 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (14 chapters)

Front matter, english grammar.

- Susan Lavender, Stavroula Varella

Short Narrative 1

Morphemes, words and lexical categories, nouns and noun phrases, verbs 1: tense and aspect, verbs 2: modality, catenation and multi-word verbs, verb phrases, basic clauses, connecting ideas: clauses revisited, framing and compiling: sentences and the text, bringing it all together 1: a holistic review of chaps. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 based on narrative 1, bringing it all together 2: a holistic appreciation of narrative 1, short narrative 2, moving on 1: a holistic review of chaps. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 based on narrative 2, moving on 2: a holistic appreciation of narrative 2, back matter.

- noun phrase

- verb phrase

- word classes

- sentence structure

- basic clauses

- language structure

About this book

This textbook familiarizes students with grammatical concepts of the English language and develops skills to apply grammar to creative writing and the study of literature. Students take an interactive 'learn-by-doing' approach to the mechanics of language and explore the creative uses of grammar. Experimenting with their own linguistic and creative skills, they come to appreciate the importance of language not only as a means of communication but also as an essential part of creative practice and literary composition. This applied approach to learning about grammar will be a valuable resource for students of English Literature and Creative Writing who may already be good users of grammar but not fully aware of its significance for communication and creativity.

Authors and Affiliations

Susan Lavender

Stavroula Varella

About the authors

Bibliographic information.

Book Title : Grammar in Literature

Book Subtitle : A Text-based Guide for Students

Authors : Susan Lavender, Stavroula Varella

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98893-7

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan Cham

eBook Packages : Social Sciences , Social Sciences (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2022

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-98892-0 Published: 03 June 2022

eBook ISBN : 978-3-030-98893-7 Published: 02 June 2022

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XVI, 210

Number of Illustrations : 3 b/w illustrations

Topics : Grammar , English , Creative Writing , Creativity and Arts Education

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

31 Literary Variation

Lesley Jeffries is Professor of Linguistics and English Language at the University of Huddersfield, UK, where she has worked for most of her career. She is the co-author of Stylistics (2010, CUP) and Keywords in the Press (2017, Bloomsbury) and author of a number of books and articles on aspects of textual meaning including Opposition in Discourse (2010, Bloomsbury), Critical Stylistics (2010, Palgrave) and Textual Construction of the Female Body (2007, Palgrave). She is particularly interested in the interface between grammar and (textual) meaning and is currently working on a new book investigating the meaning of contemporary poetry.

- Published: 05 March 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter investigates grammatical variation in literary texts. It introduces key concepts in stylistics and discusses topics that stylisticians have been concerned with at the interface between literature and grammar, such as the use in literary texts of non-standard forms of the language and the iconic use of grammar to produce literary meaning and effects. Stylistics is now very much more than the application of linguistic description to the language of literature and has developed theories and models of its own. But at the core of the discipline remains text (both spoken and written) and the notion that text producers have choices as to how they put language into texts. This chapter explains the grammatical aspects of such choices and the literary effects they can have.

31.1 Introduction

In this chapter I will investigate grammatical variation in literary texts. As a full survey of this field would be a book in itself, I have instead chosen some topics that stylisticians have been concerned with at the interface between literature and grammar. These include the use in literary texts of non-standard forms of the language, either by writing in regional or social varieties or by the stretching of ‘rules’ (section 31.3 ), and the direct use of grammar to produce literary meaning through the exploitation of its iconic potential (section 31.4 ). Stylistics is now very much more than the application of linguistic description to the language of literature and has developed theories and models of its own. But at the core of the discipline remains text (both spoken and written) and the notion that text producers have choices as to how they put language into texts. Section 31.2 will introduce some of the background to stylistic discussion of literary texts.

Literature is one creative use of language (others include political speeches and advertising) which provides an opportunity to test the models arising from different grammatical theories. This opportunity arises because literary texts often stretch the norms of everyday usage. Interpreting divergent grammar relies on understanding what is ‘normal’ and can thereby reflect the systematic aspects of grammar. The strategies readers use to understand divergent grammar need explaining just as much as the stages that learners go through in acquiring a language or the loss of grammatical ability in aphasia. As John Sinclair puts it:

no systematic apparatus can claim to describe a language if it does not embrace the literature also; and not as a freakish development, but as a natural specialization of categories which are required in other parts of the descriptive system. (Sinclair 2004 : 51)

31.2 Stylistics: concepts and approaches

In this section I will introduce some of the fundamental ideas and terminology used in stylistics (see Leech and Short 2007 and Jeffries and McIntyre 2010 for further reading). Section 31.2.1 considers whether there is such a thing as ‘literary style’; section 31.2.2 introduces fundamental concepts in stylistics; section 31.2.3 summarizes the development of cognitive approaches to style; and section 31.2.4 discusses the influence of corpus methods on stylistic analysis of literary grammar.

31.2.1 Is literary language different from everyday language?

It is often popularly assumed that the language of literature has its own set of fundamentally different language features, and in some periods of history and some cultures today, there is indeed an expectation that the language of literature will be regarded as ‘elevated’ or special in some way. However, if there ever was an identifiably separate literary ‘register’ in English, it would be difficult to pin down to more than a handful of lexical items, most of which were regular words which fell out of fashion in everyday language and lingered on mostly in poetry (e.g., yonder and behold ).

In fact, although early stylistics, based on Russian formalism (Ehrlich 1965 ), spent a great deal of time and effort trying to define what was different about literary language, the discipline ultimately came to the view that if there is anything special about literary language, it is nevertheless drawing on exactly the same basic linguistic resources as the language in general. Thus, the idea that one might be able to list or catalogue the formal linguistic features in ‘literary’ as opposed to ‘non-literary’ language was eventually shown to be mistaken and recognition of the overlap between literary and other genres has now reached the point where stylistics tends to see ‘literariness’ as a point on a cline (Carter and Nash 1990 : 34) rather than as an absolute. Features that might be seen as more literary (though not limited to literature) would include many of the traditional figures of speech and other literary tropes, such as metaphor, irony, metonymy, and so on, though in stylistics these would be defined more closely by their linguistic nature. Thus personification, for example, would now be shown as the result of a lexico-grammatical choice, such as the decision to combine an inanimate subject with a verb requiring an animate Actor: e.g., the moon yawned .

Scholars of literary language conclude that what makes some literary works unique and/or aesthetically pleasing is the way in which they combine, frame, or contextualize the otherwise ordinary bits of language they are using. This may imply a relatively unusual concentration of one kind of feature (e.g., continuous forms of the verb such as traipsing, trudging, limping ) or unusual juxtapositions of otherwise different styles of language (e.g. a mixture of formal and informal language or a mixture of different dialects). Another feature often thought to be literary, though not unusual in other text-types, is parallelism of structure, or even exact repetition (see section 31.2.2 ). Though such features may indicate literary style, judgements about literary value are, in the end, not uniquely linguistic and are at least partly culturally determined as well as changeable (Cook 1994 ).

31.2.2 Stylistic concepts: foregrounding, deviation, and parallelism

Stylistics began in the early twentieth century, drawing on ideas of defamiliarization from Russian formalism, which considered that works of art were aiming to make the familiar seem new. Stylistics captured this interest from a linguistic perspective by developing the related concepts of foregrounding and deviation. Foregrounding refers to the process by which individual features of text stand out from their surroundings, while deviation refers to one of the means by which this foregrounding is achieved (Douthwaite 2000 , Leech 2008 : 30). Two kinds of deviation, external and internal, are distinguished. External deviation refers to features that are different in some way to the norms of the language generally. Internal deviation refers to features that differ from the norms of the text in which they appear.

Studies of the psychological reality of foregrounding have demonstrated that what scholars are noticing matches the reader’s experience. Van Peer (1986), for example, used experimental methods to ascertain which features readers were paying special attention to and found that these matched the features identified in stylistic analysis. Miall and Kuiken ( 1994 ) found further support for the psychological reality of foregrounding and also produced evidence that the foregrounded features can provoke an emotional response.

There are many potential candidates for prototypically literary features, but none of them would be found uniquely in literature and most derive their power, including their literary effect, by reference to the norms of everyday language or the norms of the text they appear in. We will see some further examples of this phenomenon in section 31.4 on iconicity in grammar, but a straightforward illustration of foregrounding is the use of parallelism in the structuring of literary (and other) texts, as seen in the opening stanza of the classic children’s poem by Alfred Noyes, ‘The Highwayman’ (1906: 244–7): 1

The wind was a torrent of darkness among the gusty trees, The moon was a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas, The road was a ribbon of moonlight over the purple moor, And the highwayman came riding – Riding – riding – The highwayman came riding, up to the old inn-door.

There is nothing grammatically unusual about the structure of each of the first three lines of this stanza, which have a Subject–Verb–Complement–Adverbial pattern. 2 It is rather the three repetitions of the same structure that both set the musical framework for the poem, and allow the emergence of the highwayman from the distance to be foregrounded, since he arrives at the point where the grammatical pattern set up in the first three lines is disrupted for the first time. There is also a change of pattern from descriptive sentences of the pattern ‘X was Y’, where the copular verb ( be ) sets up a metaphorical equivalence between the subject and the complement of the sentence. The new pattern from line four by contrast has a human Agent in subject position ( the highwayman ), followed by an active verb phrase ( came riding ). This change in pattern foregrounds the highwayman from the surrounding moorland-plus-sky scene, emphasizing that he is the only sentient—and active—being for miles around.

This kind of patterning is not unique to literary genres. The form and function of parallelism in political speech-making, for example, is similar to that in literature, making the language memorable and creating both musicality and foregrounding. An example is the following passage from the famous wartime speech by UK prime minister Winston Churchill, calling the British people to fight: 3

we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender

Advertising also uses parallel structures and in everyday life we sometimes use parallelism to foreground something in the stories we tell each other.

Parallelism (Leech 2008 : 22–3) can occur at any level of structure, from phonological to syntactic, and can be internally deviant (i.e. the remainder of the text does not consist of parallel structures) as well as being externally deviant (i.e. we do not normally speak or write using continually repeated structures). Parallelism can also become backgrounded where it is ubiquitous and therefore normalized. All of these effects are seen in ‘The Highwayman’, where the stanza patterns are the same each time, so that although there is a disruption (internal deviation) at line four, this is itself a regularity causing the reader to expect the same pattern in each stanza after the foregrounding of the disruption in verse one.

As this example of parallelism shows, foregrounding depends upon the background, which is also stylistically patterned. Anyone who has ever described an utterance as ‘Pinteresque’, referring to the idiosyncratically sparse style of playwright Harold Pinter, is instinctively responding to these background features of the text. The rise of corpus stylistics (see section 31.2.4 below) has enabled scholars to examine these less stark patterns of style empirically for the first time.

31.2.3 Text and context: author, narrator, character, and reader

The task of describing the style of literary texts combines an understanding of the norms of the language whilst recognizing unusual and abnormal usage for literary effect. In addition to the increased accuracy of description enabled by linguistic analysis, stylistics has developed a range of theories and models to address questions of textual meaning and where it resides.

These theories need to recognize the special communicative circumstances of literary works. Though readers may believe the author is directly addressing them, there is often a layering of participants in the discourse situation reflected in a distance between authors, readers, narrators, and characters invoked in reading a text. The discourse structure model, proposed by Leech and Short ( 2007 : 206–18), envisages a number of levels of participation, including implied author and implied reader, which are the idealized form of these participants as envisaged by each other. There may also be one or more layers of narration as, for example, in the Joseph Conrad novel Heart of Darkness . The opening of this novel is in the voice of a first person narrator telling a tale about himself and three friends on a yacht with the ‘Director of Companies’ as their captain and host. Very soon, this I-narrative gives way to another first person narrative, when one of the friends, Marlow, starts to tell a tale about his adventures in Africa. The remainder of the novel, with the exception of the last short paragraph, is in Marlow’s voice, though it is being channelled through the voice of the first (unnamed) narrator. Within Marlow’s story, there is also a great deal of quotation of others’ speech, mostly between other characters, but also often with Marlow himself as speaker or addressee, as in the following extract (Conrad 1993 : 96):

“‘His end,’ said I, with dull anger stirring in me, ‘was in every way worthy of his life.’ “‘And I was not with him,’ she murmured. My anger subsided before a feeling of infinite pity. “‘Everything that could be done—’ I mumbled.

Marlow is quoting (to his friends) his conversation with the fiancée of Kurtz, the subject of the novel, and the original narrator quotes him quoting this conversation. The original narrator also implies the existence of an interlocutor (his addressee). In addition, the author (Conrad) is telling the reader this whole narrative and there is therefore an implied (idealized) author and reader as well as the actual author and reader. Thus there are at least five levels at which some kind of communication is taking place.

Such complexity of structure clearly has knock-on effects in the grammar (for example, the patterning of tenses) of the text. Remarkably, perhaps, the average reader seems to find it relatively easy to navigate the different layers of narration, possibly by letting only the most relevant layer take precedence at any one time. Recent developments in stylistics have attempted to explain the reader’s negotiation of such complexity, drawing on cognitive linguistic and psychological theories to explain readers’ construction of textual meaning. Among these, Emmott’s (1997) contextual frame theory, Werth’s (1999) Text World Theory, and Lakoff and Johnson’s (1980) conceptual metaphor theory have influenced our understanding of the reading process. Emmott, for example, proposes a framework where the reader constructs contextual frames as they read, with episodic and non-episodic information being attached to the frames as the text is processed. This information is kept in mind by the reader through two processes, which Emmott labels ‘binding’ and ‘priming’. The features of any scene in the text at any one point will be bound to that scene and may be primed (i.e. brought to the forefront of the reader’s attention) if the scene is the current focus in the text being read. Once the reader moves on to a new passage, the features of that scene become ‘unprimed’ but remain bound into the scene in the reader’s memory. Thus, the reader of Heart of Darkness will at some level be aware of the initial scene on the yacht where Marlow, the original narrator and three other men are sitting, throughout. However, as this scene is not referred to again for a very long period, it is unprimed for most of the main narrative and starts to fade from the reader’s attention. The return of this scene for one final paragraph is both a jolt to the reader’s memory as they recall the features that were bound to the scene early on, and also a renewal of the many narrative layers in the novel, which could perhaps produce some scepticism for the reader as to the accuracy of the story they have just been told.

Another cognitive theory, deictic shift theory (McIntyre 2006 ), helps to explain how the reader perceives the unfolding action through linguistically determined and changing points-of-view. Each of these cognitive theories envisages how some aspect of the text’s meaning is likely to be produced in the reader’s mind on the basis of features of the text. The grammatical aspects considered by these theories tend to be at levels higher than the sentence, such as textual cohesion (Halliday and Hasan 1976), verb tense sequences, narration types (first, second, third person, etc.) and other textual features such as transitivity or modality patterning that produce particular effects in constructing text worlds (see Werth 1999 and Gavins 2007 ).

As we shall see below, there are some aspects of grammatical variation in literature where the potential effect on the reader appears to be based on a combination of what we might consider their ‘normal’ experience of the language and the foregrounded and deviant structures they encounter. This extends the cognitive trend in stylistics to include grammatical structure itself and as a result, increasingly stylistics scholars are using cognitive grammar to analyse literary texts (Harrison et al. 2014; see also Taylor, this volume).

31.2.4 Corpus stylistics

The advent of powerful computer technology and software to process large corpora of linguistic data has impacted practically and theoretically on the field of stylistics. The processing of literary texts using corpus software can not only tell us something about the style of a particular author 4 but also show how authors produce characterization through stylistic choices (e.g., Culpeper 2009 ). Corpus analysis reveals other broader patterns, not necessarily consciously noticed by readers, detailing the background style of texts and genres, against which internally deviant features are foregrounded. Important early work in this field includes Burrows ( 1987 ) who took computational analysis of literature to a new level by demonstrating that the behaviour of certain word classes (e.g., the modal verbs) could be shown to differentiate Austen’s characters, her speech and narration and different parts of her oeuvre.

Generic tools available through most corpus linguistic software can be used to identify regular collocational patterns, which involve words that tend to occur together (e.g., boundless energy ), and are largely semantic in nature; and also to identify n-grams (see Stubbs 2005 ), significantly frequent multiword sequences (e.g., it seemed to me ), used to discover expressions typical of an author, character or genre. Corpus stylistics of this kind depends on an electronic version of the text in which word forms can be identified. One good example is Ho ( 2012 ) who demonstrates the production and testing of hypotheses about the style of John Fowles.

A step up from using word-form recognition software is to use a part-of-speech tagged corpus as in Mahlberg ( 2013 ), who, amongst other things, examines the repetition of lexical clusters in the work of Dickens. These consist of repeated sequences of words with lexical gaps as in ‘(with) his/her ___ prep det ____’ (where ‘prep’ and ‘det’ match words tagged as prepositions and determiners, respectively): examples of this pattern include ‘with his eyes on the ground’ or ‘his hand upon his shoulder’. Such clusters demonstrate a link with more lexically-based approaches to communication (Hoey 2005 ) and developments in grammatical theory such as construction grammar which emphasizes the importance of semi-prefabricated utterances (Croft 2001 and see also Hilpert, this volume, for more on constructional approaches to grammar). Whilst construction grammar attempts to describe the facility with which speakers produce apparently new structures in general language use, however, Mahlberg’s clusters are identified as having what she terms a ‘local textual function’ indicating important features of the plot or character.

Progress towards a reliable automated word class tagging tool has been made (Garside 1987 , Fligelstone et al. 1996 , Fligelstone et al. 1997 , Garside and Smith 1997 ), but correctly identifying the word class of even high percentages (96–7 per cent) of words is not the same as producing a full grammatical analysis. Very few attempts have been made to study literature with a fully-parsed corpus of data, though Moss ( 2014 ) is an exception in creating and analysing a parsed corpus of the work of Henry James. (See also Wallis, this volume for more on corpus approaches to grammatical research.) Automatic parsing (structural analysis) has a much higher error rate than automatic part-of-speech tagging, and the process of manual correction is labour-intensive. Consequently, there are only a small number of fully parsed and corrected corpora, such as ICE-GB ( https://www.ucl.ac.uk/english-usage/projects/ice-gb/) based at the Survey of English Usage (University College London) (see Wallis, this volume). Though some attempts have been made to semi-automate the tagging of corpora for discourse presentation (see, for example, Mahlberg’s CliC software 5 ), there remain many difficulties with identifying the different functions of some formal structures, such as modal verbs, whose function (e.g., epistemic or deontic) can only be discerned by a human analyst (see Ziegeler, this volume, for discussion of modality).

The other huge advance in corpus methods is the chance to use very large corpora (e.g., the British National Corpus: www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/ ) as a baseline against which smaller corpora or individual texts or features can be compared. Although there remain problems in defining what constitutes any particular norm, the growing number of both general and specific corpora has enabled researchers to establish what might be considered a background style.

31.3 Using non-standard forms in literature

Most recent developments in literary language have tended towards democratization. The use of social and regional dialect forms in literature has challenged the dominance of varieties connected with education, wealth and power (section 31.3.1 ), and many writers have challenged not only the supremacy of one variety of English, but also the dominance of the written over the spoken mode (section 31.3.2 ). In addition, there have been attempts by writers to represent thought rather than language itself, and this is seen in the relative ‘ungrammaticality’ of some literary work (section 31.3.3 ).

31.3.1 Representing regional and social varieties in literature

Perhaps the most obvious question to ask about the grammar of literary works is whether they use a standard form of the language. Authors can be constrained by social and cultural pressures to use a standard form but increasingly in literatures written in English there is a sense that anything goes. Literary fashions at times dictated which variety of a language was acceptable for literary works, but this kind of linguistic snobbery is no longer the norm and geographical, social, and ethnic varieties are increasingly in use in mainstream as well as niche forms of literature. Much contemporary literature attempts to replicate dialect forms in the written language, in the dialogue and sometimes also in the narration, particularly where the narrator is a character in the story. Examples of different dialect use include the novels of James Kelman (e.g., The Busconductor Hines and How Late it Was, How Late ), which are written in a Glaswegian dialect; the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency novels by Alexander McCall Smith who represents Botswanan English in his characters’ speech; Roddy Doyle whose novels (e.g., Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha ; The Commitments ) conjure up Irish dialects of English and Cormac McCarthy (e.g., Blood Meridian ) whose characters and narration reflect the language of North America’s Southwest. There are many others, of course, and the increasing informality of literary prose means that the boundary between dialect and informal language is increasingly invisible (see Hodson 2014 on the use of dialect in film and literature).

Since the early twentieth century, writers have found themselves increasingly able to exercise choice of variety, yet sometimes these decisions can be politically charged. Writers who operated entirely in their native dialect in the more distant past were perhaps less conscious of making a decision than those using their dialect to contest oppressive regimes or to give voice to people with less access to prestigious forms of the language. The relationship between dialect literature and oppression, however, is not always straightforward. Whilst some writers (e.g., Irvine Welsh, who used code-switching between idiomatic Scots and Standard English in both the dialogue and narration of his novel Trainspotting ) might wish to assert their right to write in a non-standard dialect (or a minority language), others have been advised to do so by the powerful elites of dominant culture:

Howells suggests that in order to assure both critical acclaim and commercial success, the poet should dedicate himself to writing verses only in “black” dialect (Jarrett 2010 : 178).

Here, we see Jarrett’s representation of the advice from a benevolent, if patronising, literary reviewer and publisher, William Howells, to the poet and fiction writer Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906), who was ‘torn between, on the one hand, demonstrating his commitment to black political progress and, on the other, representing blacks as slaves and their language as dialect, which are what prominent literary critics and publishers expected of him and black writers in general’ (Jarrett 2010 : 177).

The representation of variation in language use has been a significant part of characterization at least since Chaucer’s time, when, as Phillips ( 2011 : 40) says, ‘Chaucer’s fictional language lessons run counter to much conventional wisdom about late medieval multilingual practice, as he celebrates enterprising poseurs instead of diligent scholars or eloquent courtiers’. Whilst Chaucer’s pilgrims were found code-switching repeatedly between English, French, and Latin, Shakespeare’s characters were more prone to being caricatured by isolated and repeated dialect forms such as ‘look you’ for the Welsh characters (e.g., Fluellen in Henry V or Evans in Merry Wives of Windsor ) or incorrect Early Modern English grammar, such as ‘this is lunatics’ (Crystal 2008a : 222).

31.3.2 Representation of spoken/informal language in literature

There are many ways in which grammatical variation is used to invoke the spoken language in literary works, often to produce realism, but also to produce foregrounding by internally deviant uses of non-standard spoken forms contrasting with surrounding standard forms. The literary effects of this are wide-ranging, but include the kind of pathos we find in Yorkshire poet Tony Harrison’s poems about his (dead) parents, where the sounds and structures of his father’s voice, for example, are blended with the poet’s own educated standard English style. Thus, we find the opening line of ‘Long Distance II’ includes ‘my mother was already two years dead’ (Harrison 1985 : 133), where a standard version would change was dead to had been dead .

Apart from advantages for the scansion and rhyme-scheme, this hints at the humble origins of the poet whose life has taken such a different path to those of his parents. Harrison’s evocation of his father in ‘Long Distance I’ includes non-standard demonstratives preceding nouns such as ‘them sweets’ (instead of those sweets ) which evoke the old man whose dialect the poet used to share. Much of Harrison’s early poetry relates his experience of becoming differentiated from his family background by his education and he mostly writes in Standard English where his ‘own’ voice is being represented. To find occasional hints of his earlier dialect in amongst the standard forms, then, directly references his bifurcated identity and is a kind of iconic use of dialect forms to reflect the meaning of the poem directly.

As well as including regional dialect forms, writers have increasingly adopted informal modes of expression, even in novels. Some writers adopt an almost entirely consistent spoken dialect (e.g., Irvine Welsh in Trainspotting ) but others represent spoken language only in the reported speech of novels or the script of plays. Modern grammatical description based on spoken corpora of language has developed ways of identifying patterns in this informal usage of speakers (Carter and McCarthy 2006 ) which show that it is also highly structured. Examples include utterances that are grammatically indeterminate (e.g., Wow ); phrases that function communicatively in context without clause structure (e.g., Oh that ); aborted or incomplete structures (e.g., A bit ) and back-channelling (e.g., Mm or Yeah ) where speakers support each other (examples from Carter 2003 ; see also Dorgeloh and Wanner, this volume).

The direct quoting of spoken language is a staple of narrative fiction and there are also clear grammatical regularities in any indirect quotation, so that present tense verbs take on a past form when quoted indirectly, first person becomes third person and any proximal deixis becomes distal. Thus I am coming home next Tuesday turns into He said he was going home the following Tuesday . These clear categories of direct and indirect speech, however, have been shown by stylistics to be more complex in practice, as there are other categories of speech presentation, including perhaps the most versatile and interesting category, ‘free indirect speech’ (Leech and Short 2007 : 260–70). With free indirect speech, some of the lexis and grammatical form of the quoted speaker is included, although some changes in form (i.e. tense, person, and deixis) match those for indirect speech. Thus, we might see He was coming home next Tuesday as a kind of blend of the two examples above, presenting the reader with both a narrated version of the speech and also something of the flavour of the original utterance, with the tense and person changed, but the deixis left intact. More or fewer of the features of indirect speech may be included, resulting in an apparently more or less faithful version of the original utterance. However, context is crucial for understanding whose words are being represented, as the loss of quotation marks and reporting clause can make the utterance appear to belong to the narrator or implied author instead. Whilst not unique to literary texts, free indirect speech is particularly useful to fiction-writers for blending the point-of-view of their characters with that of the narrator and/or implied author.

31.3.3 Representing cognitive patterns through ‘ungrammaticality’

One consequence of increasing variation in literary language is the experimentation with non-dialectal ‘ungrammaticality’ which has featured in many movements including modernist writing (e.g., Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf), L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry (e.g., Leslie Scalapino, Stephen Rodefer, Bruce Andrews) and feminist poetry (e.g., Fleur Adcock, U. A. Fanthorpe, Carol Rumens). The twentieth century in particular was a time when structuralist views of how human language worked induced in some writers the conviction that the language they spoke and used on a daily basis was inappropriate to their needs as artists, as it was likely to reproduce and reinforce social attitudes and inequalities embedded in the community from which it arose. This view arose from popular versions of the ‘Whorfian hypothesis’ (or ‘Sapir–Whorf hypothesis’; see Aarts et al. 2014 ) which, in its strong form, claimed that human beings were limited to thinking along lines laid out by the language they spoke. Feminists responded strongly to this theory as helping to explain some aspects of their oppression in a patriarchal society (see, for example, Spender 1980). Creative responses to this hypothesis, now accepted in a much weaker form (that language influences thought rather than determining it), went beyond the more basic reaction against the (standard) language of a recognized oppressor, with the result that writers tried to reflect mental and emotional states directly through a fragmentary and ‘new’ form of the language.

Here is an example from ‘Droplets’ by Carol Rumens, who, like other contemporary poets, has responded to the freedom of challenging grammatical ‘correctness’ in her poems:

Tiniest somersaulter through unroofed centuries, puzzling your hooped knees as you helter-skelter, dreamy, careless, Carol Rumens, ‘Droplets’( Hex , Bloodaxe Books, 2002, p. 15) 6

Not only does Rumens play with the morphology here, creating nouns from verbs (‘somersaulter’) and verbs from nouns (‘helter-skelter’) as well as possibly nonce-derived forms such as ‘unroofed’, she also fails to resolve the syntax by not introducing any main clause verbs until so late that they seem to have no real connection to the long series of images conjured up by multiple noun phrases and subordinate clauses. Her explanation for this (private communication) is that it is an ‘apostrophe’, a poetic form in which the speaker in a poem addresses someone or something not present. This may have influenced the long sequence of address forms, but it does not alter the fact that the syntax, by everyday standards, is stretched to the limit.

These literary responses to language as a kind of socio-cultural straightjacket originally resulted in writing that was deemed ‘too difficult’ by the reading public, though in some cases, such as the poetry of T. S. Eliot, critics celebrated the innovations. Over time, however, writers reverted to exploiting in less extreme ways some of the flexibilities built into the ‘system’ of the language, bending the rules without completely abandoning them and relying on more subtle forms of foregrounding to communicate their meaning. In addition, poetry readers became more accustomed to seeing the grammar stretched in new ways and were better able to process the results.

In a number of cases, such examples of gentle, but often repetitive grammatical abnormality—or spoken forms—have been used to produce a particular kind of characterization to identify the neuro-atypicality of characters and indicate their unusual ways of seeing the world. This technique is labelled ‘mind-style’ in stylistics (Fowler 1977 ) and, unlike the modernist and other writers expressing their own angst in relation to the world, mind-style is a use of ungrammaticality to express—and to try to understand—the world view of people we may otherwise not comprehend.

There are a few famous and well-studied novels that feature the language of a character whose cognitive processes differ from those of the majority population. These include, for example, characters with learning difficulties such as Benjy in Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury and characters who appear to lack the normal cognitive abilities of Homo sapiens such as the Neanderthal, Lok, in Golding’s The Inheritors (Leech and Short 2007 ). Other studies have focussed on characters showing symptoms of high-functioning autism such as Christopher in Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time (Semino 2014 ).

In the case of Benjy and Lok, from totally different worlds, but sharing a lack of understanding about causation, we find, for example, that transitive verbs are used without their objects, since the connections between the action and its effect are missing (Leech and Short 2007 : 25–9 and 162–6 respectively). Here, for example, Benjy is describing a game of golf: ‘Through the fence, between the curling flower spaces, I could see them hitting’. Possibly because of the distance (he is looking through the fence) or because he doesn’t understand the purpose of golf, Benjy just describes the actions of the golfers and leaves the normally transitive verb without its goal. The reader has to work out what is going on from this and similar sentences.

In the case of Christopher, the linguistic correlates of his cognitive style include his lack of use of pro-forms, resulting in repetitive parallel structures (e.g., ‘I do not like proper novels. In proper novels people say…’) and his over-use of coordinated structures rather than subordinated structures (e.g., ‘I said that I wanted to write about something real and I knew people who had died but I did not know any people who had been killed, except Edward’s father from school, Mr Paulson, and that was a gliding accident, not murder, and I didn’t really know him’) (Semino 2014 ). In all these cases, the grammatical oddness provides clues as to the character’s cognitive state, rather than an attempt to literally reproduce the likely language of such a character.

Similarly, where a short-term rather than a chronic cognitive impairment is depicted by textual means, the apparent breakdown of language may symbolically represent the mental distress of the character, rather than directly representing their language use. An example is the William Golding novel Pincher Martin , whose protagonist is drowning and where the stylistic choices reflect his mental state as his body parts appear to take on a life of their own: ‘His hand let the knife go’. A fuller analysis of this phenomenon in the novel can be found in Simpson ( 1993 : 111–12) who shows that as Pincher Martin gets closer to death, the role of Actor in relation to material action clauses is increasingly taken by either body parts or by inanimate entities such as ‘the lumps of hard water’ or ‘sea water’. Pincher Martin stops having agency and is reduced to an observer of his own demise.

31.4 Iconic grammar, creativity, and the reader

The discussion of grammatical variation in literature in this section will compare literary style with general or statistical norms of grammatical behaviour in English. In considering grammatical aspects of literary style, there are interesting effects that poets can achieve by the subtlest of manipulations of the ‘normal’ grammatical resources of English. The effects examined below do, of course, occur in prose as well as poetry and in non-literary as well as literary texts, but they seem peculiarly concentrated in poems as some of them are likely to have detrimental effects on comprehension in the more functional genres, which, unlike poetry, depend on conformity to norms of structure. Poetic style depends a great deal on the local effects of individual stylistic choices made by the poet, which are therefore more often foregrounded effects, rather than cumulative background effects of a pattern of choices. However, some of these choices also build up over a text to produce a particular topographical effect which may provide the norm against which a later internally deviant feature could be contrasted.

In this section I will use the semiotic concept of ‘iconicity’ to refer to the kind of direct meaning-making that emanates from certain grammatical choices made by poets. Whilst not as directly mimetic as the sound of a word (e.g., miaouw ) representing the sound it refers to, this form of iconicity can be said to be mimetic insofar as it exploits the inevitable temporal processing of language (Jeffries 2010b ). It is no surprise, then, to find that the speeding up and delaying of time in structural ways forms a large part of the iconicity to be found amongst grammatical choices in poetry.

31.4.1 Nominal versus verbal grammar and literary effect

For convenience, we might argue that language use is largely made up of labelling/naming (Jeffries 2010a ) and of the representation of processes and states. Roughly speaking, these divisions of meaning match nominal and verbal structures. The remainder of the language is largely subsumed into these divisions (e.g., adjectives often occur within noun phrases; many adverbs are attached to verbs) and what is not accounted for in this way—mostly adverbials and a few adjectival complements—forms a tiny part of the whole.