- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

- Health Sciences

Medical Students Scholarly Project Course

- Literature Review

What is a literature review?

Systematic reviews vs literature reviews, literature reviews - articles, writing literature reviews, frequently used journal article databases.

- Conference Posters This link opens in a new window

- Soft Skills

The literature review is the qualitative summary of evidence on a topic using informal or subjective methods to collect and interpret studies.The literature review can inform a particular research project or can result in a review article publication.

- Aaron L. Writing a literature review article. Radiol Technol. 2008 Nov-Dec; 80(12): 185-6.

- Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Blackmore H, Kitas GD. Writing a narrative biomedical review: considerations for authors, peer reviewers, and editors. Rheumatol Int. 2011 Nov; 31(11): 1409-17.

- Matharu GS, Buckley CD. Performing a literature review: a necessary skill for any doctor. Student BMJ. 2012; 20:e404. Requires FREE site registration

- Literature Reviews The Writing Center at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has created a succinct handout that explains what a literature review is and offer insights into the form and construction of a literature review in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

- Review Articles (Health Sciences) Guide Identifies the difference between a systematic review and a literature review. Connects to tools for research, writing, and publishing.

- Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review by Andrew Booth; Diana Papaioannou; Anthea Sutton Call Number: Norris Medical Library, Upper Level, LB 1047.3 B725s 2012

- Documenting your search This resource provides guidance on how to document and save database search strategies.

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

- Embase This link opens in a new window

- Google Scholar This link opens in a new window

- PsycINFO This link opens in a new window

- Scopus This link opens in a new window

- Web of Science This link opens in a new window

- Next: Data Mgmt >>

- Last Updated: Nov 1, 2023 3:17 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/healthsciences/spc

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Performing a...

Performing a literature review

- Related content

- Peer review

- Gulraj S Matharu , academic foundation doctor ,

- Christopher D Buckley , Arthritis Research UK professor of rheumatology

- 1 Institute of Biomedical Research, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, School of Immunity and Infection, University of Birmingham, UK

A necessary skill for any doctor

What causes disease, which drug is best, does this patient need surgery, and what is the prognosis? Although experience helps in answering these questions, ultimately they are best answered by evidence based medicine. But how do you assess the evidence? As a medical student, and throughout your career as a doctor, critical appraisal of published literature is an important skill to develop and refine. At medical school you will repeatedly appraise published literature and write literature reviews. These activities are commonly part of a special study module, research project for an intercalated degree, or another type of essay based assignment.

Formulating a question

Literature reviews are most commonly performed to help answer a particular question. While you are at medical school, there will usually be some choice regarding the area you are going to review.

Once you have identified a subject area for review, the next step is to formulate a specific research question. This is arguably the most important step because a clear question needs to be defined from the outset, which you aim to answer by doing the review. The clearer the question, the more likely it is that the answer will be clear too. It is important to have discussions with your supervisor when formulating a research question as his or her input will be invaluable. The research question must be objective and concise because it is easier to search through the evidence with a clear question. The question also needs to be feasible. What is the point in having a question for which no published evidence exists? Your supervisor’s input will ensure you are not trying to answer an unrealistic question. Finally, is the research question clinically important? There are many research questions that may be answered, but not all of them will be relevant to clinical practice. The research question we will use as an example to work through in this article is, “What is the evidence for using angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors in patients with hypertension?”

Collecting the evidence

After formulating a specific research question for your literature review, the next step is to collect the evidence. Your supervisor will initially point you in the right direction by highlighting some of the more relevant papers published. Before doing the literature search it is important to agree a list of keywords with your supervisor. A source of useful keywords can be obtained by reading Cochrane reviews or other systematic reviews, such as those published in the BMJ . 1 2 A relevant Cochrane review for our research question on ACE inhibitors in hypertension is that by Heran and colleagues. 3 Appropriate keywords to search for the evidence include the words used in your research question (“angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor,” “hypertension,” “blood pressure”), details of the types of study you are looking for (“randomised controlled trial,” “case control,” “cohort”), and the specific drugs you are interested in (that is, the various ACE inhibitors such as “ramipril,” “perindopril,” and “lisinopril”).

Once keywords have been agreed it is time to search for the evidence using the various electronic medical databases (such as PubMed, Medline, and EMBASE). PubMed is the largest of these databases and contains online information and tutorials on how to do literature searches with worked examples. Searching the databases and obtaining the articles are usually free of charge through the subscription that your university pays. Early consultation with a medical librarian is important as it will help you perform your literature search in an impartial manner, and librarians can train you to do these searches for yourself.

Literature searches can be broad or tailored to be more specific. With our example, a broad search would entail searching all articles that contain the words “blood pressure” or “ACE inhibitor.” This provides a comprehensive list of all the literature, but there are likely to be thousands of articles to review subsequently (fig 1). ⇓ In contrast, various search restrictions can be applied on the electronic databases to filter out papers that may not be relevant to your review. Figure 2 gives an example of a specific search. ⇓ The search terms used in this case were “angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor” and “hypertension.” The limits applied to this search were all randomised controlled trials carried out in humans, published in the English language over the last 10 years, with the search terms appearing in the title of the study only. Thus the more specific the search strategy, the more manageable the number of articles to review (fig 3), and this will save you time. ⇓ However, this method risks your not identifying all the evidence in the particular field. Striking a balance between a broad and a specific search strategy is therefore important. This will come with experience and consultation with your supervisor. It is important to note that evidence is continually becoming available on these electronic databases and therefore repeating the same search at a later date can provide new evidence relevant to your review.

Fig 1 Results from a broad literature search using the term “angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor”

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Fig 2 Example of a specific literature search. The search terms used were “angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor” and “hypertension.” The limits applied to this search were all randomised controlled trials carried out in humans, published in English over the past 10 years, with the search terms appearing in the title of the study only

Fig 3 Results from a specific literature search (using the search terms and limits from figure 2)

Reading the abstracts (study summary) of the articles identified in your search may help you decide whether the study is applicable for your review—for example, the work may have been carried out using an animal model rather than in humans. After excluding any inappropriate articles, you need to obtain the full articles of studies you have identified. Additional relevant articles that may not have come up in your original search can also be found by searching the reference lists of the articles you have already obtained. Once again, you may find that some articles are still not applicable for your review, and these can also be excluded at this stage. It is important to explain in your final review what criteria you used to exclude articles as well as those criteria used for inclusion.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) publishes evidence based guidelines for the United Kingdom and therefore provides an additional resource for identifying the relevant literature in a particular field. 4 NICE critically appraises the published literature with recommendations for best clinical practice proposed and graded based on the quality of evidence available. Similarly, there are internationally published evidence based guidelines, such as those produced by the European Society of Cardiology and the American College of Chest Physicians, which can be useful when collecting the literature in a particular field. 5 6

Appraising the evidence

Once you have collected the evidence, you need to critically appraise the published material. Box 1 gives definitions of terms you will encounter when reading the literature. A brief guide of how to critically appraise a study is presented; however, it is advisable to consult the references cited for further details.

Box 1: Definitions of common terms in the literature 7

Prospective—collecting data in real time after the study is designed

Retrospective—analysis of data that have already been collected to determine associations between exposure and outcome

Hypothesis—proposed association between exposure and outcome. If presented in the negative it is called the null hypothesis

Variable—a quantity or quality that changes during the study and can be measured

Single blind—subjects are unaware of their treatment, but clinicians are aware

Double blind—both subjects and clinicians are unaware of treatment given

Placebo—a simulated medical intervention, with subjects not receiving the specific intervention or treatment being studied

Outcome measure/endpoint—clinical variable or variables measured in a study subsequently used to make conclusions about the original interventions or treatments administered

Bias—difference between reported results and true results. Many types exist (such as selection, allocation, and reporting biases)

Probability (P) value—number between 0 and 1 providing the likelihood the reported results occurred by chance. A P value of 0.05 means there is a 5% likelihood that the reported result occurred by chance

Confidence intervals—provides a range between two numbers within which one can be certain the results lie. A confidence interval of 95% means one can be 95% certain the actual results lie within the reported range

The study authors should clearly define their research question and ideally the hypothesis to be tested. If the hypothesis is presented in the negative, it is called the null hypothesis. An example of a null hypothesis is smoking does not cause lung cancer. The study is then performed to assess the significance of the exposure (smoking) on outcome (lung cancer).

A major part of the critical appraisal process is to focus on study methodology, with your key task being an assessment of the extent to which a study was susceptible to bias (the discrepancy between the reported results and the true results). It should be clear from the methods what type of study was performed (box 2).

Box 2: Different study types 7

Systematic review/meta-analysis—comprehensive review of published literature using predefined methodology. Meta-analyses combine results from various studies to give numerical data for the overall association between variables

Randomised controlled trial—random allocation of patients to one of two or more groups. Used to test a new drug or procedure

Cohort study—two or more groups followed up over a long period, with one group exposed to a certain agent (drug or environmental agent) and the other not exposed, with various outcomes compared. An example would be following up a group of smokers and a group of non-smokers with the outcome measure being the development of lung cancer

Case-control study—cases (those with a particular outcome) are matched as closely as possible (for age, sex, ethnicity) with controls (those without the particular outcome). Retrospective data analysis is performed to determine any factors associated with developing the particular outcomes

Cross sectional study—looks at a specific group of patients at a single point in time. Effectively a survey. An example is asking a group of people how many of them drink alcohol

Case report—detailed reports concerning single patients. Useful in highlighting adverse drug reactions

There are many different types of bias, which depend on the particular type of study performed, and it is important to look for these biases. Several published checklists are available that provide excellent resources to help you work through the various studies and identify sources of bias. The CONSORT statement (which stands for CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) provides a minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomised controlled trials and comprises a rigorous 25 item checklist, with variations available for other study types. 8 9 As would be expected, most (17 of 25) of the items focus on questions relating to the methods and results of the randomised trial. The remaining items relate to the title, abstract, introduction, and discussion of the study, in addition to questions on trial registration, protocol, and funding.

Jadad scoring provides a simple and validated system to assess the methodological quality of a randomised clinical trial using three questions. 10 The score ranges from zero to five, with one point given for a “yes” in each of the following questions. (1) Was the study described as randomised? (2) Was the study described as double blind? (3) Were there details of subject withdrawals, exclusions, and dropouts? A further point is given if (1) the method of randomisation was appropriate, and (2) the method of blinding was appropriate.

In addition, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme provides excellent tools for assessing the evidence in all study types (box 2). 11 The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine levels of evidence is yet another useful resource for assessing the methodological quality of all studies. 12

Ensure all patients have been accounted for and any exclusions, for whatever reason, are reported. Knowing the baseline demographic (age, sex, ethnicity) and clinical characteristics of the population is important. Results are usually reported as probability values or confidence intervals (box 1).

This should explain the major study findings, put the results in the context of the published literature, and attempt to account for any variations from previous work. Study limitations and sources of bias should be discussed. Authors’ conclusions should be supported by the study results and not unnecessarily extrapolated. For example, a treatment shown to be effective in animals does not necessarily mean it will work in humans.

The format for writing up the literature review usually consists of an abstract (short structured summary of the review), the introduction or background, methods, results, and discussion with conclusions. There are a number of good examples of how to structure a literature review and these can be used as an outline when writing your review. 13 14

The introduction should identify the specific research question you intend to address and briefly put this into the context of the published literature. As you have now probably realised, the methods used for the review must be clear to the reader and provide the necessary detail for someone to be able to reproduce the search. The search strategy needs to include a list of keywords used, which databases were searched, and the specific search limits or filters applied. Any grading of methodological quality, such as the CONSORT statement or Jadad scoring, must be explained in addition to any study inclusion or exclusion criteria. 6 7 8 The methods also need to include a section on the data collected from each of the studies, the specific outcomes of interest, and any statistical analysis used. The latter point is usually relevant only when performing meta-analyses.

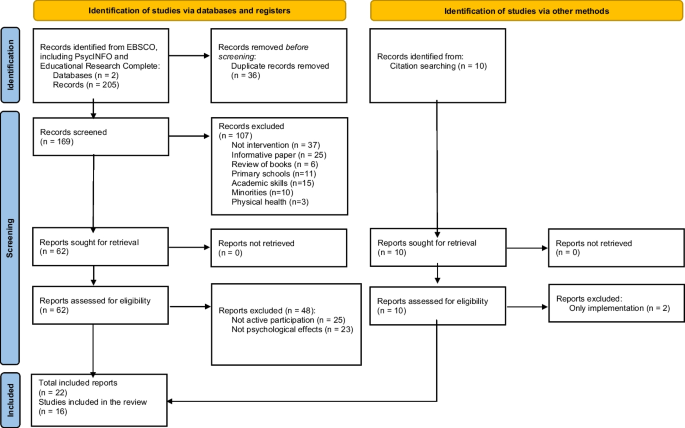

The results section must clearly show the process of filtering down from the articles obtained from the original search to the final studies included in the review—that is, accounting for all excluded studies. A flowchart is usually best to illustrate this. Next should follow a brief description of what was done in the main studies, the number of participants, the relevant results, and any potential sources of bias. It is useful to group similar studies together as it allows comparisons to be made by the reader and saves repetition in your write-up. Boxes and figures should be used appropriately to illustrate important findings from the various studies.

Finally, in the discussion you need to consider the study findings in light of the methodological quality—that is, the extent of potential bias in each study that may have affected the study results. Using the evidence, you need to make conclusions in your review, and highlight any important gaps in the evidence base, which need to be dealt with in future studies. Working through drafts of the literature review with your supervisor will help refine your critical appraisal skills and the ability to present information concisely in a structured review article. Remember, if the work is good it may get published.

Originally published as: Student BMJ 2012;20:e404

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ The Cochrane Library. www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgibin/mrwhome/106568753/HOME?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0 .

- ↵ British Medical Journal . www.bmj.com/ .

- ↵ Heran BS, Wong MMY, Heran IK, Wright JM. Blood pressure lowering efficacy of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008 ; 4 : CD003823 , doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003823.pub2. OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. www.nice.org.uk .

- ↵ European Society of Cardiology. www.escardio.org/guidelines .

- ↵ Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, Heit JA, Samama CM, Lassen MR, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th ed). Chest 2008 ; 133 : 381 -453S. OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki .

- ↵ Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, et al. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet 2001 ; 357 : 1191 -4. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ The CONSORT statement. www.consort-statement.org/ .

- ↵ Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996 ; 17 : 1 -12. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). www.sph.nhs.uk/what-we-do/public-health-workforce/resources/critical-appraisals-skills-programme .

- ↵ Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine—Levels of Evidence. www.cebm.net .

- ↵ Van den Bruel A, Thompson MJ, Haj-Hassan T, Stevens R, Moll H, Lakhanpaul M, et al . Diagnostic value of laboratory tests in identifying serious infections in febrile children: systematic review. BMJ 2011 ; 342 : d3082 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Awopetu AI, Moxey P, Hinchliffe RJ, Jones KG, Thompson MM, Holt PJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between hospital volume and outcome for lower limb arterial surgery. Br J Surg 2010 ; 97 : 797 -803. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- University of Texas Libraries

- UT Libraries

Literature Reviews

- Dell Medical School Library

- LibKey Nomad - Full Text

- What's New?

- Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Clinical Trials

- Drug Information

- Health and Medical Law

- Point-of-Care Tools

- Test Prep Resources

- Video, Audio, and Images

- Search Tips

- PubMed Guide This link opens in a new window

- Ask the Question

- Acquire the Evidence

- Appraise the Evidence

- Evidence Hierarchy

- EBM Bibliography

- Child Neurology

- Dermatology

- Emergency Medicine

- Family Medicine

- Internal Medicine

- Obstetrics & Gynecology

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopaedic Surgery

- Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation

- Mobile Apps

- Citation Managers This link opens in a new window

- Citation Manuals

- General Resources

- Study Types

- Systematic Reviews

- Scoping Reviews

- Rapid Reviews

- Integrative Reviews

- Technical Reports

- Case Reports

- Getting Published

- Selecting a Journal

- Open Access Publishing

- Avoiding Low Quality Open Access

- High Quality Open Access Journals

- Keeping Up with the Literature

- Health Statistics

- Research Funding This link opens in a new window

- Author Metrics

- Article Metrics

- Journal Metrics

- Scholarly Profile Tools

- Health Humanities This link opens in a new window

- Health Equity This link opens in a new window

- UT-Authored Articles

- Resources for DMS COVID-19 Elective

- Types of Literature Reviews

- How to Write a Literature Review

- How to Write the Introduction to a Research Article

- Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements | Health Information and Libraries Journal, 2019

- A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies | Health Information and Libraries Journal, 2009

- Conceptual recommendations for selecting the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to answer research questions related to complex evidence | Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 2016

- Methods for knowledge synthesis: an overview | Heart & Lung: The Journal of Critical Care, 2014

- Not sure what type of review to conduct? Brief descriptions of each type plus tools to help you decide

- Ten simple rules for writing a literature review | PLoS Computational Biology, 2013

- The Purpose, Process, and Methods of Writing a Literature Review | AORN Journal. 2016

- Why, When, Who, What, How, and Where for Trainees Writing Literature Review Articles. | Annals of Biomed Engineering, 2019

- So You Want to Write a Narrative Review Article? | Journal of Cardiothoracic and Anesthesia, 2021

- An Introduction to Writing Narrative and Systematic Reviews - Tasks, Tips and Traps for Aspiring Authors | Heart, Lung, and Circulation, 2018

- The Literature Review: A Foundation for High-Quality Medical Education Research | Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 2016

- Writing an effective literature review : Part I: Mapping the gap | Perspectives on Medical Education, 2018

- Writing an effective literature review : Part II: Citation technique | Perspectives on Medical Education, 2018

- Last Updated: Mar 7, 2024 6:43 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/medicine

Home » Office of Curriculum » Medical Student Scholarship » III Scholarship Start Here » Scholarship of Integration » Key Steps in a Literature Review

Key Steps in a Literature Review

The 5 key steps below are most relevant to narrative reviews. Systematic reviews include the additional step of using a standardized scoring system to assess the quality of each article. More information on Step 1 can be found here and Step 5 here .

- Consider the purpose and rationale of a review

- Clearly articulate the components of the question

- The research question and purpose of your review should guide the development of your search strategy (i.e. which databases to search and which search terms to use)

- Justify any limitations you create for your search,

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Start by reviewing abstracts for relevant articles. Once this is complete, then begin a full text review of the remaining articles.

- Develop a data-charting form to extract data from each article. Update this form as needed if you find there is more information worth collecting.

- The resulting forms will serve as a summary of each article that will facilitate the process of synthesizing your results (i.e. the selected articles).

- In your analysis, include a numerical summary of studies included, an evidence table summarizing included articles, and a qualitative summary of the results.

- Report the results in the context of the overall purpose or research question.

- Consider the meaning of your results. Discuss limitations and implications for future research, practice, and/or policy.

Scholarship of Integration

- III Scholarship of Integration Timeline

- How to Find a Project

- Directory of Faculty Projects

- Choosing a Faculty Mentor

- How to Create a Research Question

- How to Write Your Project Proposal

- How to Write Your Final Paper

- Final Paper Evaluation Rubric

- Career Advising

Melbourne Medical School

- Our Departments

- Medical Education

- Qualitative journeys

Literature review

Literature reviews are a way of identifying what is already known about a research area and what the gaps are. To do a literature review, you will need to identify relevant literature, often through searching academic databases, and then review existing literature. Most often, you will do the literature review at the beginning of your research project, but it is iterative, so you may choose to change the literature review as you move through your project.

Searching the literature

The University of Melbourne Library has some resources about searching the literature. Leonie spoke about how she met with a librarian about searching the literature. You may also want to meet face-to-face with a librarian or attend a class at the library to learn more about literature searching. When you search the literature, you may find journal articles, reports, books and other materials.

Filing, categorising and managing literature

In order to manage the literature you have identified through searches, you may choose to use a reference manager. The University of Melbourne has access to RefWorks and Endnote. Further information about accessing this software is available through the University of Melbourne Library .

Writing a literature review

The purpose of the literature review is to identify what is already known about a particular research area and critically analyse prior studies. It will also help you to identify any gaps in the research and situate your research in what is already known about a particular topic.

- Aveyard, H. (2010). Doing a literature review in health and social care: A practical guide . London, UK: McGraw-Hill Education. Retrieved from Proquest https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unimelb/detail.action?docID=771406

- Reeves, S., Koppel, I., Barr, H., Freeth, D., Hammick, M. (2002). Twelve tips for undertaking a systematic review. Medical Teacher . 24(4), 358-363 .

- Grant, M.J. and Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal .

- Jesson, J., & Lacey, F. (2006). How to do (or not to do) a critical literature review. Pharmacy Education , 6(2), 139-148 .

- Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences

- Baker Department of Cardiometabolic Health

- Clinical Pathology

- Critical Care

- General Practice and Primary Care

- Infectious Diseases

- Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Newborn Health

- Paediatrics

- Rural Health

- News & Events

- Medical Research Projects by Theme

- Department Research Overviews

- General Practice

- Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Graduate Research

- Medical Research Services

- Our Degrees

- Scholarships, Bursaries and Prizes

- Our Short Courses

- Current Student Resources

- Melbourne Medical Electives

- Welcome from the School Head

- Honorary Appointments

- MMS Staff Hub

- Current Students

The use of drugs and medical students: a literature review

Affiliations.

- 1 4Th-year Medical Students fo the State University of Ponta Grossa (PR), Brazil.

- 2 Master in Science and Technology Teaching; Associate Professor of the Medical Program of the State University of Ponta Grossa (PR), Brazil.

- 3 PhD in Internal Medicine; Adjunct Professor of Medicine at the Ponta Grossa State University (UEPG), Ponta Grossa (PR), Brazil.

- PMID: 30304147

- DOI: 10.1590/1806-9282.64.05.462

Introduction: The consumption and abuse of alcohol and other drugs are increasingly present in the lives of university students and may already be considered a public health problem because of the direct impacts on the physical and mental health of these individuals. The requirements of the medical program play a vital role in the increasing rate of drug users.

Objectives: To carry out a systematic review of the literature on the use of drugs, licit or not, in Brazilian medical students.

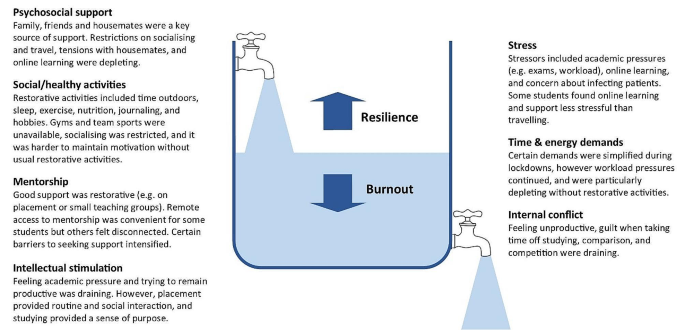

Methods: A descriptive-exploratory study, in which the SciELO and MEDLINE databases were used. A total of 99 articles were found, of which 16 were selected for this review.

Results: Alcohol and tobacco were the most frequently used licit drugs among medical students. The most consumed illicit drugs were marijuana, solvents, "lança-perfume" (ether spray), and anxiolytics. The male genre presented a tendency of consuming more significant amounts of all kinds of drugs, with the exception of tranquilizers. It was found an increasing prevalence of drug consumption in medical students, as the program progressed, which may result from the intrinsic stress from medical school activities. Students who do not use psychoactive drugs are more likely to live with their parents, to disapprove drugs consumption, to practice religious beliefs and to be employed.

Conclusion: The prevalence of licit and illicit drug use among medical students is high, even though they understand the injuries it may cause.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Alcohol Drinking / epidemiology

- Brazil / epidemiology

- Illicit Drugs

- Marijuana Smoking / epidemiology

- Sex Factors

- Smoking / epidemiology

- Students, Medical / psychology*

- Substance-Related Disorders / epidemiology*

- Open access

- Published: 28 March 2024

Medical student wellbeing during COVID-19: a qualitative study of challenges, coping strategies, and sources of support

- Helen M West ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8712-5890 1 ,

- Luke Flain ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7296-6304 2 ,

- Rowan M Davies 3 , 4 ,

- Benjamin Shelley 3 , 5 &

- Oscar T Edginton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5298-9402 3 , 6

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 179 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Medical students face challenges to their mental wellbeing and have a high prevalence of mental health problems. During training, they are expected to develop strategies for dealing with stress. This study investigated factors medical students perceived as draining and replenishing during COVID-19, using the ‘coping reservoir’ model of wellbeing.

In synchronous interactive pre-recorded webinars, 78 fourth-year medical students in the UK responded to reflective prompts. Participants wrote open-text comments on a Padlet site. Responses were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Analysis identified five themes. COVID-19 exacerbated academic pressures, while reducing the strategies available to cope with stress. Relational connections with family and friends were affected by the pandemic, leading to isolation and reliance on housemates for informal support. Relationships with patients were adversely affected by masks and telephone consultations, however attending placement was protective for some students’ wellbeing. Experiences of formal support were generally positive, but some students experienced attitudinal and practical barriers.

Conclusions

This study used a novel methodology to elicit medical students’ reflections on their mental wellbeing during COVID-19. Our findings reinforce and extend the ‘coping reservoir’ model, increasing our understanding of factors that contribute to resilience or burnout. Many stressors that medical students typically face were exacerbated during COVID-19, and their access to coping strategies and support were restricted. The changes to relationships with family, friends, patients, and staff resulted in reduced support and isolation. Recognising the importance of relational connections upon medical students’ mental wellbeing can inform future support.

Peer Review reports

Medical students are known to experience high levels of stress, anxiety, depression and burnout due to the nature, intensity and length of their course [ 1 ]. Medical students are apprehensive about seeking support for their mental wellbeing due to perceived stigma and concerns about facing fitness to practice proceedings [ 2 ], increasing their vulnerability to poor mental health.

Research has identified that the stressors medical students experience include a demanding workload, maintaining work–life balance, relationships, personal life events, pressure to succeed, finances, administrative issues, career uncertainty, pressure around assessments, ethical concerns, and exposure to patient death [ 3 , 4 ]. In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional stressors into medical students’ lives. These included sudden alterations to clinical placements, the delivery of online teaching, uncertainty around exams and progression, ambiguity regarding adequate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), fear of infection, and increased exposure to death and dying [ 5 , 6 ]. Systematic reviews have reported elevated levels of anxiety, depression and stress among medical students during COVID-19 [ 7 ] and that the prevalence of depression and anxiety during COVID-19 was higher among medical students than in the general population or healthcare workers [ 8 ].

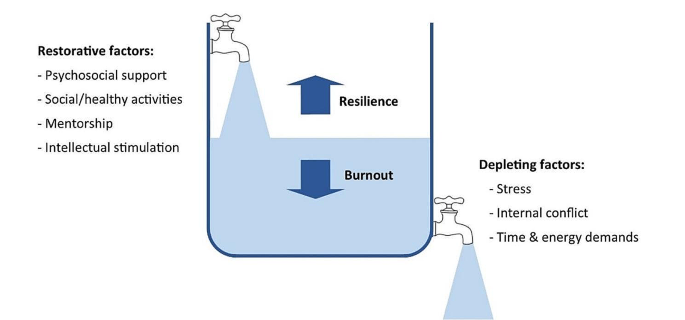

While training, medical students are expected to develop awareness of personal mental wellbeing and learn healthy coping strategies for dealing with stress [ 9 ]. Developing adaptive methods of self-care and stress reduction is beneficial both while studying medicine, and in a doctor’s future career. Protecting and promoting psychological wellbeing has the potential to improve medical students’ academic attainment, as well as their physical and mental wellbeing [ 10 ], and it is therefore important for medical educators to consider how mental wellbeing is fostered. Feeling emotionally supported while at medical school reduces the risk of psychological distress and burnout, and is related to whether students contemplate dropping out of medical training [ 11 ]. In their systematic narrative review of support systems for medical students during COVID-19, Ardekani et al. [ 12 ] propose a framework incorporating four levels: policies that promote a supportive culture and environment, active support for students at higher risk of mental health problems, screening for support needs, and provision for students wishing to access support. This emphasis on preventative strategies aligns with discussions of trauma-informed approaches to medical education, which aim to support student learning and prevent harm to mental wellbeing [ 13 ]. Dunn et al. [ 14 ] proposed a ‘coping reservoir’ model to conceptualise the factors that deplete and restore medical students’ mental wellbeing (Fig. 1 ). This reservoir is drained and filled repeatedly, as a student faces demands for their time, energy, and cognitive and emotional resources. This dynamic process leads to positive or negative outcomes such as resilience or burnout.

Coping reservoir model– adapted from Dunn et al. [ 14 ], with permission from the authors and Springer Nature

At present we have limited evidence to indicate why medical students’ mental wellbeing was so profoundly affected by COVID-19 and whether students developed coping strategies that enhanced their resilience, as suggested by Kelly et al. [ 15 ]. This study therefore sought to conceptualise the challenges medical students experienced during COVID-19, the coping strategies they developed in response to these stressors, and the supportive measures they valued. The ‘coping reservoir’ model [ 14 ] was chosen as the conceptual framework for this study because it includes both restorative and depleting influences. Understanding the factors that mediate medical students’ mental wellbeing will enable the development of interventions and support that are effective during crises such as the pandemic and more generally.

Methodology

This research study is based on a critical realist paradigm, recognising that our experience of reality is socially located [ 16 ]. Participant responses were understood to represent a shared understanding of that reality, acknowledging the social constructivist position that subjective meanings are formed through social norms and interactions with others, including while participating in this study. It also draws on hermeneutic phenomenology in aiming to interpret everyday experienced meanings for medical students during COVID-19 [ 17 ]. The use of an e-learning environment demonstrates an application of connectivism [ 18 ], a learning theory in which students participate in technological enabled networks. We recognise that meaning is co-constructed by the webinar content, prompts, ‘coping reservoir’ framework and through the process of analysis.

The multidisciplinary research team included a psychologist working in medical education, two medical students, and two Foundation level doctors. The team’s direct experience of the phenomenon studied was an important resource throughout the research process, and the researchers regularly reflected on how their subjective experiences and beliefs informed their interpretation of the data. Reflexive thematic analysis was chosen because it provides access to a socially contextualised reality, encompasses both deductive and inductive orientations so that analysis could be informed by the ‘coping reservoir’ while also generating unanticipated insights, and enables actionable outcomes to be produced [ 19 ].

Ethical approval

Approval was granted by the University of Liverpool Institute of Population Health Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 8365).

Participants

Fourth-year medical students at the University of Liverpool were invited to participate in the study during an online webinar in their Palliative Medicine placement. During six webinars between November 2020 and June 2021, 78 out of 113 eligible students participated, giving a response rate of 69%. This was a convenience sample of medical students who had a timetabled session on mental wellbeing. At the time, these medical students were attending clinical placements, however COVID-19 measures in the United Kingdom meant that academic teaching and support was conducted online, travel was limited, and contact with family and friends was restricted.

Students were informed about the study prior to the synchronous interactive pre-recorded webinar and had an opportunity to ask questions. Those who consented to participate accessed a Padlet ( www.padlet.com ) site during the webinar that provided teaching on mental wellbeing, self-care and resilience in the context of palliative medicine. Padlet is a collaborative online platform that hosts customisable virtual bulletin boards. During this recording, participants were asked to write anonymous open-text responses to reflective prompts developed from reviewing the literature (Appendix 1 ), and post these on Padlet. The Padlet board contained an Introduction to the webinar, sections for each prompt, links to references, and signposting to relevant support services. Data files were downloaded to Excel and stored securely, in line with the University of Liverpool Research Data Management Policy.

The research team used the six steps of reflexive thematic analysis to analyse the dataset. This process is described in Table 1 , and the four criteria for trustworthiness in qualitative research proposed by Lincoln and Guba [ 20 ] are outlined in Table 2 . We have used the purposeful approach to reporting thematic analysis recommended by Nowell et al. [ 21 ] and SRQR reporting standards [ 22 ] (Appendix 2 ).

Five themes were identified from the analysis:

COVID-19 exacerbated academic pressures.

COVID-19 affected students’ lifestyles and reduced their ability to cope with stress.

COVID-19 changed relationships with family and friends, which affected mental wellbeing.

COVID-19 changed interactions with patients, with positive and negative effects.

Formal support was valued but seeking it was perceived as more difficult during COVID-19.

COVID-19 exacerbated academic pressures

‘Every day feels the same, it’s hard to find motivation to do anything.’

Many participants reported feeling under chronic academic pressure due to studying medicine. Specific stressors reported were exams, revision, deadlines, workload, specific course requirements, timetables, online learning, placement, and communication from University. Some participants also reported negative effects on their mental wellbeing from feelings of comparison and competition, feeling unproductive, and overthinking.

Massive amounts of work load that feels unachievable.

COVID-19 exacerbated these academic stresses, with online learning and monotony identified as particularly draining. However, other students found online learning beneficial, due to reduced travelling.

I miss being able to see people face to face and zoom is becoming exhausting. My mental wellbeing hasn’t been great recently and I think the effects of the pandemic are slowly beginning to affect me.

I also prefer zoom as it is less tiring than travelling to campus/placement.

Clinical placements provided routine and social interaction. However, with few social interactions outside placement, this became monotonous. A reduction in other commitments helped some students to focus on their academic requirements.

Most social activity only taking place on placement has made every day feel the same.

Some students placed high value on continuing to be productive and achieve academically despite the disruption of a pandemic, potentially to the detriment of their mental wellbeing. Time that felt unproductive was frustrating and draining.

Having a productive day i.e. going for a run and a good amount of work completed in the day.

Unproductive days of revision or on placement.

COVID-19 affected students’ lifestyles and reduced their ability to cope with stress

‘Everyone’s mental well-being decreased as things they used for mental health were no longer available’.

Students often found it difficult to sustain motivation for academic work without the respite of their usual restorative activities challenging.

Not being able to balance work and social life to the same extent makes you resent work and placement more.

The competing demands medical students encounter for their time and energy were repeatedly reported by participants.

Sometimes having to go to placement + travel + study + look after myself is really tough to juggle!

However, removing some of the boundaries around academic contact and structure of extracurricular activities heightened the impact of stressors. Many participants focused on organising and managing their time to cope with this. Students were aware that setting time aside for relaxation, enjoyment, creativity, and entertainment would be beneficial for their wellbeing.

Taking time off on the weekends to watch movies.

However, they found it difficult to prioritise these without feeling guilty or believing they needed to ‘earn’ them, and academic commitments were prioritised over mental wellbeing.

Try to stop feeling guilty for doing something that isn’t medicine. Would like to say I’d do more to increase my mental wellbeing but finals are approaching and that will probably have to take priority for the next few months.

Medical students were generally aware that multiple factors such as physical activity, time with loved ones, spiritual care, nourishment and hobbies had a positive impact on their mental wellbeing. During COVID-19, many of the coping strategies that students had previously found helpful were unavailable.

Initially it improved my mental well-being as I found time to care for myself, but with time I think everyone’s mental well-being decreased as things they used for mental health were no longer available e.g. gym, counselling, seeing friends.

Participants adapted to use coping strategies that remained available during the pandemic. These included walks and time spent outdoors, exercise, journaling, reflection, nutrition, and sleep.

'Running’. ‘Yoga’. ‘Fresh air and walks'.

A few students also reported that they tried to avoid unhelpful coping strategies, such as social media and alcohol.

Not reading the news, not using social media.

Avoiding alcohol as it leads to poor sleep and time wasted.

Many participants commented on increased loneliness, anxiety, low mood, frustration, and somatic symptoms.

Everyone is worn out and demotivated. Feel that as I am feeling low I don’t want to bring others down. ‘Feel a lot more anxious than is normal and also easily annoyed and irritable.’

However, not all students reported that COVID-19 had a negative effect on wellbeing. A small minority responded that their wellbeing had improved in some way.

I think covid-19 has actually helped me become more self reliant in terms of well-being.

COVID-19 changed relationships with family and friends, which affected mental wellbeing

‘Family are a huge support for me and I miss seeing them and the lack of human contact.’

Feeling emotionally supported by family and friends was important for medical students to maintain good mental wellbeing. However, COVID-19 predominantly had a negative impact on these relationships. Restrictions, such as being unable to socialise or travel during lockdowns, led to isolation and poor mental wellbeing.

Not being able to see friends or travel back home to see friends/family there.

Participants frequently reported that spending too much time with people, feeling socially isolated, being unable to see people, or having negative social experiences had an adverse effect on their mental wellbeing. Relationships with housemates were a key source of support for some students. However, the increased intensity in housemate relationships caused tension in some cases, which had a particularly negative effect.

Much more difficult to have relationships with peers and began feeling very isolated. Talk about some of the experiences I’ve had on placement with my housemates. Added strain on my housemates to be the only ones to support me.

Knowing that their peers were experiencing similar stressors helped to normalise common difficulties. The awareness that personal contacts were also struggling sometimes curtailed seeking informal support to avoid being a burden.

Actually discussing difficulties with friends has been most helpful, as it can sometimes feel like you’re the only one struggling, when actually most people are finding this year really difficult. Family and friends, but also don’t want to burden them as I know I can feel overwhelmed if people are always coming to me for negative conversations.

COVID-19 changed interactions with patients, with positive and negative effects

‘With patients there has been limited contact and I miss speaking to patients.’

Some students reported positive effects on relationships with patients, and feeling a sense of purpose in talking to patients when their families were not allowed to visit. Medical students felt a moral responsibility to protect patients and other vulnerable people from infection, which contributed to a reduction in socialising even when not constrained by lockdown.

Talking to patients who can’t get visitors has actually made me feel more useful. Anxiety over giving COVID-19 to patients or elderly relatives.

Students occasionally reported that wearing PPE made interactions with patients more challenging. Students’ contact with patients changed on some placements due to COVID-19, for example replacing in-person appointments with telephone consultations, and they found this challenging and disappointing.

Masks are an impediment to meaningful connections with new people. GP block when I saw no patients due to it all being on the telephone.

Formal support was valued but seeking it was perceived as more difficult during COVID-19

‘Feel a burden on academic and clinical staff/in the way/annoying so tend to just keep to myself.’

Many participants emphasised the primary importance of support from family and friends, and their responses indicated that most had not sought formal support. While staff remained available and created opportunities for students to seek support, factors such as online learning and increased clinical workloads meant that some students found it harder to build supportive relationships with academic and placement staff and felt disconnected from them, which was detrimental for wellbeing and engagement.

Staff have been really helpful on placement but it was clear that in some cases, staff were overwhelmed with the workload created by COVID. Even though academic staff are available having to arrange meetings over zoom rather than face to face to discuss any problem is off putting.

A few students described difficulty knowing what support was available, and identifying when they needed it.

It’s difficult to access support when you’re not sure what is available. Also you may feel your problems aren’t as serious as other people’s so hold off on seeking support.

Formal support provided within the University included meetings with Academic Advisors, the School of Medicine wellbeing team, and University counselling service and mental health advisory team. It was also available from NHS services, such as GPs and psychological therapies. Those who had accessed formal support mostly described positive experiences with services. However, barriers to seeking formal support, such as perceived stigma, practicalities, waiting times for certain services, and concern that it may impact their future career were reported by some participants.

It is good that some services offer appointments that are after 5pm- this makes it more accessible to healthcare students. Had good experience with GPs about mental health personally. Admitting you need help or asking for help would make you look weak. Reassurance should be provided to medical students that accessing the wellbeing team is not detrimental to their degree. If anything it should be marketed as a professional and responsible thing to do.

Some students preferred the convenience of remote access, others found phone or video impersonal and preferred in-person contact.

Students expressed that it was helpful when wellbeing support was integrated with academic systems, for example Academic Advisors or placement supervisors.

My CCT [primary-care led small group teaching] makes sure to ask how we are getting on and how our placements are going, so I think small groups of people with more contact with someone are more useful then large groups over zoom. Someone to speak to on palliative care placement, individual time with supervisor to check how we are doing (wellbeing, mental health) - would be a nice quick checkup.

Participants typically felt able to share openly in an anonymous forum. Reading peers’ comments helped them to see that other students were having similar experiences and challenged unhealthy comparisons.

I definitely shared more than I would have done on a zoom call. I loved this session as it makes you feel like you’re not alone. Reassuring to know that there are others going through similar things as you.

Our findings demonstrate that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the stressors medical students experience, and removed some rewarding elements of learning, while reducing access to pre-existing coping strategies. The results support many aspects of the ‘coping reservoir’ framework [ 14 ]. Findings corroborate the restorative effects of psychosocial support and social/healthy activities such as sleep and physical activity, and the depletion of wellbeing due to time and energy demands, stress, and disruptions relating to the pandemic such as online teaching and limited social interaction. Feeling a sense of purpose, from continuing studying or interactions with patients for example, was restorative for wellbeing. Mentorship and intellectual stimulation were present in the responses, but received less attention than psychosocial support and social/healthy activities. Internal conflict is primarily characterised by Dunn et al. [ 14 ] as ambivalence about pursuing a career in medicine, which was not expressed by participants during the study. However, participants identified that their wellbeing was reduced by feeling unproductive and lacking purpose, feeling guilty about taking time for self-care, competing priorities, and comparison with peers, all of which could be described as forms of internal conflict. Different restorative and draining factors appeared to not be equally weighted by the participants responding to the prompts: some appear to be valued more highly, or rely on other needs being met. Possible explanations are that students may be less likely to find intellectual stimulation and mentorship beneficial if they are experiencing reduced social support or having difficulty sleeping, and internal conflict about pursuing a career in medicine might be overshadowed by more immediate concerns, for example about the pandemic. This prioritisation resembles the relationship between physiological and psychological needs being met and academic success [ 23 ], based on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs [ 24 ]. A revised ‘coping reservoir’ model is shown in Fig. 2 .

Coping reservoir model - the effects of COVID-19 on restorative and depleting factors for medical students, adapted from Dunn et al. [ 14 ], with permission from the authors and Springer Nature

Relational connections with family, friends, patients, and staff were protective factors for mental wellbeing. Feeling emotionally supported by family and friends is considered especially important for medical students to maintain good mental wellbeing [ 11 ]. These relationships usually mitigate the challenges of medical education [ 25 ], however they were fundamentally affected by the pandemic. Restrictions affecting support from family and friends, and changes to contact with patients on placement, had a negative effect on many participants’ mental wellbeing. Wellbeing support changed during the pandemic, with in-person support temporarily replaced by online consultations due to Government guidelines. Barriers to seeking formal support, such as perceived stigma, practicalities, and concern that it may impact their future career were reported by participants, reflecting previous research [ 26 ]. Despite initiatives to increase and publicise formal support, some students perceived that this was less available and accessible during COVID-19, due to online learning and awareness of the increased workload of clinicians, as described by Rich et al. [ 27 ]. These findings provide further support for the job demand-resources theory [ 28 , 29 ] where key relationships and support provide a protective buffer against the negative effects of challenging work.

In line with previous research, many participants reported feeling under chronic academic pressure while studying medicine [ 3 ]. Our findings indicate that medical students often continued to focus on achievement, productivity and competitiveness, despite the additional pressures of the pandemic. Remaining productive in their studies might have protected some students’ mental wellbeing by providing structure and purpose, however students’ responses primarily reflected the adverse effect this mindset had upon their wellbeing. Some students felt guilty taking time away from studying to relax, which contributes to burnout [ 30 ] , and explicitly prioritised academic achievement over their mental wellbeing.

Students were aware of the factors that have a positive impact on their mental wellbeing, such as physical activity, time with loved ones, spiritual care, nourishment and hobbies [ 31 ]. However, COVID-19 restrictions affected many replenishing factors, such as socialising, team sports, and gyms, and intensified draining factors, such as academic stressors. Students found ways to adapt to the removal of most coping strategies, for example doing home workouts instead of going to the gym, showing how they developed coping strategies that enhanced their resilience [ 15 ]. However, they found it more difficult to mitigate the effect of restrictions on relational connections with peers, patients and staff, and this appears to have had a particularly negative impact on mental wellbeing. While clinical placements provided helpful routine, social interaction and a sense of purpose, some students reported that having few social interactions outside placement became monotonous.

Our findings show that medical students often felt disconnected from peers and academic staff, and reported loneliness, isolation and decreased wellbeing during COVID-19. This corresponds with evidence that many medical students felt isolated [ 32 ], and students in general were at higher risk of loneliness than the general population during COVID-19 lockdowns [ 33 ]. Just as ‘belongingness’ mediates subjective wellbeing among University students [ 34 ], feeling connected and supported acts as a protective buffer for medical students’ psychological wellbeing [ 25 ].

Translation into practice

Based on the themes identified in this study, specific interventions can be recommended to support medical students’ mental wellbeing, summarised in Table 3 . This study provides evidence to support the development of interventions that increase relational connections between medical students, as a method of promoting mental wellbeing and preventing burnout. Our findings highlight the importance of interpersonal relationships and informal support mechanisms, and indicate that medical student wellbeing could be improved by strengthening these. Possible ways to do this include encouraging collaboration over competition, providing sufficient time off to visit family, having a peer mentor network, events that encourage students to meet each other, and wellbeing sessions that combine socialising with learning relaxation and mindfulness techniques. Students could be supported in their interactions with patients and peers by embedding reflective practice such as placement debrief sessions, Schwartz rounds [ 35 ] or Balint groups [ 36 ], and simulated communication workshops for difficult situations.

Experiencing guilt [ 30 ] and competition [ 4 ] while studying medicine are consistently recognised as contributing to distress and burnout, so interventions targeting these could improve mental wellbeing. Based on the responses from students, curriculum-based measures to protect mental wellbeing include manageable workloads, supportive learning environments, cultivating students’ sense of purpose, and encouraging taking breaks from studying without guilt. Normalising sharing of difficulties and regularly including content within the curriculum on self-care and stress reduction would improve mental wellbeing.

In aiming to reduce psychological distress among medical students, it is important that promotion of individual self-care is accompanied by reducing institutional stressors [ 11 , 29 ]. While the exploration of individual factors is important, such as promoting healthy lifestyle habits, reflection, time management, and mindset changes, this should not detract from addressing factors within the culture, learning and work environment that diminish mental wellbeing [ 37 ]. Heath et al. [ 38 ] propose a pro-active, multi-faceted approach, incorporating preventative strategies, organisational justice, individual strategies and organisational strategies to support resilience in healthcare workers. Similarly, trauma-informed medical education practices [ 13 ] involve individual and institutional strategies to promote student wellbeing.

Students favoured formal support that was responsive, individualised, and accessible. For example, integrating conversations about wellbeing into routine academic systems, and accommodating in-person and remote access to support. There has been increased awareness of the wellbeing needs of medical students in recent years, especially since the start of the pandemic, which has led to improvements in many of these areas, as reported in reviews by Ardekani et al. [ 12 ] and Klein and McCarthy [ 39 ]. Continuing to address stigma around mental health difficulties and embedding discussions around wellbeing in the curriculum are crucial for medical students to be able to seek appropriate support.

Strengths & limitations

By using qualitative open-text responses, rather than enforcing preconceived categories, this study captured students’ lived experience and priorities [ 4 , 31 ]. This increased the salience and depth of responses and generated categories of responses beyond the existing evidence, which is particularly important given the unprecedented experiences of COVID-19. Several strategies were used to establish rigour and trustworthiness, based on the four criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba [ 20 ] (Table 2 ). These included the active involvement of medical students and recent medical graduates in data analysis and the development of themes, increasing the credibility of the research findings.

Potential limitations of the study are that participants may have been primed to think about certain aspects of wellbeing due to data being collected during a webinar delivered by medical educators including the lead author at the start of their palliative medicine placement, and the choice of prompts. Data was collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore represents fourth year medical students’ views in specific and unusual circumstances. Information on this context is provided to enable the reader to evaluate whether the findings have transferability to their setting. Responses were visible to others in the group, so participants may have influenced each other to give socially acceptable responses. This process of forming subjective meanings through social interactions is recognised as part of the construction of a shared understanding of reality, and we therefore view it as an inherent feature of this methodology rather than a hindrance. Feedback on the webinar indicated that students benefitted from this process of collective meaning-making. Similarly, researcher subjectivity is viewed as a contextual resource for knowledge generation in reflexive thematic analysis, rather than a limitation to be managed [ 19 ]. The study design meant that different demographic groups could not be compared.

Padlet provided a novel and acceptable method of data collection, offering researchers and educators the potential benefits of an anonymous forum in which students can see their peers’ responses. The use of an interactive webinar demonstrated a potential application of connectivist pedagogical principles [ 18 ]. Researchers are increasingly using content from online forums for qualitative research [ 40 ], and Padlet has been extensively used as an educational tool. However, to the authors’ knowledge, Padlet has not previously been used as a data collection platform for qualitative research. Allowing anonymity carried the risk of students posting comments that were inappropriate or unprofessional. However, with appropriate guidance it appeared to engender honesty and reflection, provided a safe and collaborative learning environment, and student feedback was overwhelmingly positive. It would be useful to evaluate the effects of this reflective webinar on medical students’ mental wellbeing, given that it acted as an intervention in addition to a teaching session and research study.

Students were prompted to plan what they would do following the webinar to improve their mental wellbeing. A longitudinal study to determine how students enacted these plans would allow a more detailed investigation of students’ self-care behaviour.

While we hope that the stressors of COVID-19 will not be repeated, this study provides valuable insight into medical students’ mental wellbeing, which can inform support beyond this exceptional time. The lasting impact of the pandemic upon medical education and mental wellbeing remains to be seen. Nevertheless, our findings reinforce and extend the coping reservoir model proposed by Dunn et al. [ 14 ], adding to our understanding of the factors that contribute to resilience or burnout. In particular, it provides evidence for the development of interventions that increase experiences of relational connectedness and belonging, which are likely to act as a buffer against emotional distress among medical students.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2214.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Awad F, Awad M, Mattick K, Dieppe P. Mental health in medical students: time to act. Clin Teach. 2019;16(4):312–6.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Medical student distress: causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(12):1613–22.

Hill MR, Goicochea S, Merlo LJ. In their own words: stressors facing medical students in the millennial generation. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1530558.

Papapanou M, Routsi E, Tsamakis K, Fotis L, Marinos G, Lidoriki I, et al. Medical education challenges and innovations during COVID-19 pandemic. Postgrad Med J. 2021;0:1–7.

Google Scholar

De Andres Crespo M, Claireaux H, Handa AI. Medical students and COVID-19: lessons learnt from the 2020 pandemic. Postgrad Med J. 2021;97(1146):209–10.

Paz DC, Bains MS, Zueger ML, Bandi VR, Kuo VY, Cook K et al. COVID-19 and mental health: a systematic review of international medical student surveys. Front Psychol. 2022;(November):1–13.

Jia Q, Qu Y, Sun H, Huo H, Yin H, You D. Mental health among medical students during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;13:846789.

General Medical Council. Outcomes for Graduates. London; 2020 https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/standards-and-outcomes/outcomes-for-graduates [accessed 13 Feb 2024].

Shiralkar MT, Harris TB, Eddins-Folensbee FF, Coverdale JH. A systematic review of stress-management programs for medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):158–64.

McLuckie A, Matheson KM, Landers AL, Landine J, Novick J, Barrett T, et al. The relationship between psychological distress and perception of emotional support in medical students and residents and implications for educational institutions. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(1):41–7.

Ardekani A, Hosseini SA, Tabari P, Rahimian Z, Feili A, Amini M. Student support systems for undergraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic narrative review of the literature. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:352.

Brown T, Berman S, McDaniel K, Radford C, Mehta P, Potter J, et al. Trauma-informed medical education (TIME): advancing curricular content and educational context. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):661–7.

Dunn LB, Iglewicz A, Moutier C. Promoting resilience and preventing burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):44–53.

Kelly EL, Casola AR, Smith K, Kelly S, Syl M, Cruz D, De. A qualitative analysis of third-year medical students ’ reflection essays regarding the impact of COVID-19 on their education. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(481).

Pilgrim D. Some implications of critical realism for mental health research. Soc Theory Heal. 2014;12:1–21.

Article Google Scholar

Henriksson C, Friesen N. Introduction. In: Friesen N, Henriksson C, Saevi T, editors. Hermeneutic phenomenology in education. Sense; 2012. pp. 1–17.

Goldie JGS, Connectivism. A knowledge learning theory for the digital age? Med Teach. 2016;38(10):1064–9.

Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2021.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, California: SAGE; 1985.

Book Google Scholar

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving tomeet thetrustworthiness criteria. 2017;16:1–13.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–51.

PubMed Google Scholar

Freitas FA, Leonard LJ. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and student academic success. Teach Learn Nurs. 2011;6(1):9–13.

Maslow AH. Motivation and personality. 3rd ed. New York: Longman; 1954.

MacArthur KR, Sikorski J. A qualitative analysis of the coping reservoir model of pre-clinical medical student well-being: human connection as making it worth it. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Simpson V, Halpin L, Chalmers K, Joynes V. Exploring well-being: medical students and staff. Clin Teach. 2019;16(4):356–61.

Rich A, Viney R, Silkens M, Griffin A, Medisauskaite A. UK medical students ’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e070528.

Bakker AAB, Demerouti E. Job demands-resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017;22(3):273–85.

Riley R, Kokab F, Buszewicz M, Gopfert A, Van Hove M, Taylor AK et al. Protective factors and sources of support in the workplace as experienced by UK foundation and junior doctors: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6).

Greenmyer JR, Montgomery M, Hosford C, Burd M, Miller V, Storandt MH, et al. Guilt and burnout in medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2021;34(1):69–77.

Ayala EE, Omorodion AM, Nmecha D, Winseman JS, Mason HRC. What do medical students do for self-care? A student-centered approach to well-being. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(3):237–46.

Wurth S, Sader J, Cerutti B, Broers B, Bajwa MN, Carballo S, et al. Medical students’ perceptions and coping strategies during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: studies, clinical implication, and professional identity. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):620.

Bu F, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health. 2020;186:31–4.

Arslan G, Loneliness C, Belongingness. Subjective vitality, and psychological adjustment during coronavirus pandemic: development of the college belongingness questionnaire. J Posit Sch Psychol. 2021;5(1):17–31.

Maben J, Taylor C, Dawson J, Leamy M, McCarthy I, Reynolds E et al. A realist informed mixed-methods evaluation of Schwartz center rounds in England. Heal Serv Deliv Res. 2018;6(37).

Monk A, Hind D, Crimlisk H. Balint groups in undergraduate medical education: a systematic review. Psychoanal Psychother. 2018;8734:1–26.

Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):132–49.

Heath C, Sommerfield A, Von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(10):1364–71.

Klein HJ, McCarthy SM. Student wellness trends and interventions in medical education: a narrative review. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2022;9(92).

Smedley RM, Coulson NS. A practical guide to analysing online support forums. Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(1):76–103.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr P Byrne for providing guidance, Mrs A Threlfall and Professor VCT Goddard-Fuller for commenting on drafts, and the medical students who participated in the webinars.

This study was unfunded.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, University of Liverpool, Eleanor Rathbone Building, Bedford Street South, Liverpool, L69 7ZA, UK

Helen M West

Liverpool University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, UK

School of Medicine, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

Rowan M Davies, Benjamin Shelley & Oscar T Edginton

Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, UK

Rowan M Davies

Calderdale and Huddersfield NHS Foundation Trust, West Yorkshire, UK

Benjamin Shelley

Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Leeds, UK

Oscar T Edginton

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HMW conceptualised the study and collected the data. HMW, LF, RMD, BS and OTE conducted data analysis. HMW, LF, RMD and OTE wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Helen M West .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate.

Approval was granted by the University of Liverpool Institute of Population Health Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 8365). Students were fully informed about the study prior to the workshop and had an opportunity to ask questions. Participants provided informed consent, completing an electronic consent form before responding to prompts. The study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the University of Liverpool Research Ethics and Research Data Management Policies, and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

West, H.M., Flain, L., Davies, R.M. et al. Medical student wellbeing during COVID-19: a qualitative study of challenges, coping strategies, and sources of support. BMC Psychol 12 , 179 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01618-8

Download citation

Received : 12 December 2023

Accepted : 22 February 2024

Published : 28 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01618-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Mental wellbeing

- Medical student

- Student doctor

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government