- Search Menu

- Themed Collections

- Editor's Choice

- Ilona Kickbusch Award

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Online

- Open Access Option

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Health Promotion International

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

- < Previous

Advertising appeals effectiveness: a systematic literature review

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Murooj Yousef, Sharyn Rundle-Thiele, Timo Dietrich, Advertising appeals effectiveness: a systematic literature review, Health Promotion International , Volume 38, Issue 4, August 2023, daab204, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab204

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Positive, negative and coactive appeals are used in advertising. The evidence base indicates mixed results making practitioner guidance on optimal advertising appeals difficult. This study aims to identify the most effective advertising appeals and it seeks to synthesize relevant literature up to August 2019. Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses framework a total of 31 studies were identified and analyzed. Emotional appeals, theory utilization, materials, results and quality were examined. Across multiple contexts, results from this review found that positive appeals were more often effective than coactive and negative appeals. Most studies examined fear and humour appeals, reflecting a literature skew towards the two emotional appeals. The Effective Public Health Practice Project framework was applied to assess the quality of the studies and identified that there remains opportunity for improvement in research design of advertising studies. Only one-third of studies utilized theory, signalling the need for more theory testing and application in future research. Scholars should look at increasing methodological strength by drawing more representative samples, establishing strong study designs and valid data collection methods. In the meantime, advertisers are encouraged to employ and test more positive and coactive advertising appeals.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2245

- Print ISSN 0957-4824

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Social Advertising Effectiveness in Driving Action: A Study of Positive, Negative and Coactive Appeals on Social Media

Associated data.

Data available upon request.

Background: Social media offers a cost-effective and wide-reaching advertising platform for marketers. Objectively testing the effectiveness of social media advertising remains difficult due to a lack of guiding frameworks and applicable behavioral measures. This study examines advertising appeals’ effectiveness in driving engagement and actions on and beyond social media platforms. Method: In an experiment, positive, negative and coactive ads were shared on social media and promoted for a week. The three ads were controlled in an A/B testing experiment to ensure applicable comparison. Measures used included impressions, likes, shares and clicks following the multi-actor social media engagement framework. Data were extracted using Facebook ads manager and website data. Significance was tested through a series of chi-square tests. Results: The promoted ads reached over 21,000 users. Significant effect was found for appeal type on engagement and behavioral actions. The findings support the use of negative advertising appeals over positive and coactive appeals. Conclusion: Practically, in the charity and environment context, advertisers aiming to drive engagement on social media as well as behavioral actions beyond social media should consider negative advertising appeals. Theoretically, this study demonstrates the value of using the multi-actor social media engagement framework to test advertising appeal effectiveness. Further, this study proposes an extension to evaluate behavioral outcomes.

1. Introduction

The popularity of social media is growing with advertisers utilizing different platforms to drive online and offline customer engagement [ 1 , 2 ]. As the third largest advertising channel, social media accounts for 13% of global advertising spending [ 3 ]. In 2019, Australian brands spent AUD 2.4 billion on social media advertisements, making social media the second highest expenditure category in digital advertising spending after paid search [ 4 ]. Since the COVID-19 pandemic erupted across the world, social media played a crucial role in disseminating information. Research found social media to be the most rapid digital tool in spreading information regarding the virus, which helped reach and educate specific audiences, such as front-line workers [ 5 ]. With some drawbacks due to the publication of misinformative facts and knowledge, social media platforms remain a major communication platform for scientists, organizations and governments to reach different audience groups and create highly persuasive outcomes [ 6 ]. Similarly, advertisers invest in social media platforms, seeking attention, engagement and action in online and offline, making a clear understanding of social media advertising’s effectiveness of paramount importance.

It is established that emotional appeal messages perform better on social media than rational appeals. Evidence suggests emotional appeals are more likely to achieve engagement and virality [ 1 , 7 ]. However, less is known about the effectiveness of positive, negative and coactive emotional appeals, with the best approach to take remaining unresolved. Recent studies have explored positive versus negative appeals’ effectiveness, with mixed and inconsistent results [ 8 , 9 ]. In fact, examination of coactive appeals has been neglected in contrast to efforts directed at examining positive and negative appeals, further limiting practitioner guidance. This study aims to empirically test the effectiveness of three advertising appeals (i.e., positive, negative and coactive) delivered via social media. Effectiveness is evaluated using online engagement [ 10 ] and behavioral actions.

Social Media Advertising

When creating social media ads, advertisers reportedly prioritize online engagement and utilize this measure to evaluate social media advertising success [ 11 , 12 ]. Quantitative online engagement metrics that social media platforms provide such as likes, comments, shares and clicks are key measures of online engagement. While such metrics provide insights into online engagement, they do not identify actual behaviors taken in response to viewed social media advertisements. To compensate for this omission, scholars have utilized separate data collection tools (i.e., surveys) to evaluate social media effectiveness, relying on consumer self-reports of actions taken following exposure to an advertisement [ 1 ]. The relationship between online engagement (e.g., likes, comments and shares) and behavior (e.g., donations) has received less attention. Therefore, there is limited understanding of social media advertising’s effect on actual behavior. Further, the relationship between online engagement and behavior is not reflected in social media marketing models [ 10 ] and models derived from empirical-based evaluation are needed to address this gap. To this end, the current study investigates social media advertising appeals, comparing three appeals’ (negative, positive and coactive) effects on online engagement and prosocial behavior. Drawing on empirical results, this paper proposes an extension to the social media multi-actor engagement framework outlined by Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] linking online engagement to behavior. The current study’s focus on social media advertising effectiveness is important theoretically and practically. Theoretically, the current study extends social media evaluation frameworks linking online engagement metrics with behavioral actions. On a practical level, the study enables advertisers to create effective behavior change messages on social media that go beyond likes, comments and shares, delivering empirical evidence outlining the most effective approach to engage audiences and drive action.

2. Literature Review

Advertisements are designed with the ultimate goal of changing behavior [ 13 ]. Commercially, advertisers aim to increase sales by encouraging customers to purchase certain products or choose specific brands [ 8 , 14 , 15 ]. Beyond commercial application, the power of advertising is harnessed to positively change people’s lives, encouraging social and health behaviors such as quitting smoking [ 14 ], encouraging healthy eating [ 15 ], preventing diseases [ 16 ], safe driving [ 17 ] and increasing charity donations [ 18 ]. Such efforts are known as social advertising, the use of promotion and communication techniques to change social behavior [ 19 ]. To motivate the adoption of positive social behavior, social advertising raises awareness, induces action and reinforces maintenance of prosocial behaviors [ 19 , 20 ]. One area where social advertisers may deliver change is the impact of low-quality donations on charities and the environment. One of the most challenging tasks for charities is filtering donations received based on their quality before moving donated goods for redistribution or sale to generate revenue to support essential charity service provision [ 21 ]. Australian charity organizations spend millions of dollars each year on donation sorting processes, ensuring that unusable items donated to charities are discarded and others are remanufactured, while the remaining goods are distributed or sold. In 2018, over USD 9 million was spent sending unusable donations to landfill [ 22 ]. Processing of waste by charities diverts funding away from the delivery of essential community services [ 21 ]. As much as 30% of goods donated are estimated to be unusable, suggesting that there is substantial room for improvement. Despite the magnitude of the problem, limited research focused on improving the quality of donated items is available [ 23 ].

2.1. Emotional Advertising Appeals

As advertisers increasingly seek greater communication effectiveness, the choice of advertising appeal requires more consideration and careful assessment [ 24 ]. Viewers may utilize cognitive or affective evaluation systems when processing an advertisement message [ 25 ]. Rational appeals rely on cognitive evaluations through the persuasive power of arguments or reason to change audience beliefs, attitudes and actions. Such messages are evident in the dissemination of scientific information such as the ones seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. These include facts, infographics and arguments that appeal to a person’s rational processes [ 5 ]. Conversely, emotional appeals utilize the affective evaluation system by evoking emotions to drive action. Recent meta-analytic studies identified that consumers respond more favorably to emotional appeals compared to rational appeals [ 9 , 26 ].

Emotions are defined in many different ways in the literature. In an effort to summarize all definitions in one, Kleinginna and Kleinginna [ 27 ] provide a unified definition that is now relied on by psychology, marketing and other disciplines. They define emotions as “a complex set of interactions among subjective and objective factors, mediated by neural/hormonal systems, which can (a) give rise to affective feelings of arousal, pleasure/displeasure; (b) generate cognitive processes such as emotionally relevant perceptual effects, appraisals, labeling processes; (c) activate widespread physiological adjustments to the arousing conditions; and (d) lead to behavior that is often, but not always, expressive, goal-directed, and adaptive (p. 371)”. For decades, scholars have been studying the effect of emotion on behavior through multiple disciplines and contexts. In the past 10 years, considerable advancement has been clear in research around emotions. Specifically, technology advancements along with new research methodologies allowed scholars to measure and track emotion effects more accurately than before. For example, autonomic measures, including facial expression, heart rate and skin conductance, enabled researchers and practitioners to test emotional responses to certain stimuli [ 28 ]. This, along with digital and social media growth over recent decades, created an opportunity for advertisers to create, manipulate and test different advertising strategies to achieve the highest persuasion effects.

Researchers from psychology, social sciences, health and marketing agree on the crucial role emotions play in shaping human behavior [ 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Emotions have been part of persuasion models as early as the AIDA model, with desire indicating an emotional reaction following the cognition level of attention and interest [ 32 ]. More recently, emotions were found to dominate cognition in a persuasion process, occurring before any cognitive assessment of the message [ 33 ]. Hence, emotions are crucial in advertising’s ability to influence behavior [ 30 , 31 ].

For years, classifying emotions has been a research interest with multiple schools of thought. There are two main ways of classifying emotions, categorically (i.e., discrete emotions) or dimensionally. The discrete emotions approach posits that emotions are specific and defined. Different scholars present different sets of discrete emotions. For example, Ekman [ 34 ] presented six basic emotions, namely anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness and surprise. Plutchik [ 35 ] argued there are eight basic emotions (fear, anger, sorrow, joy, disgust, acceptance, anticipation and surprise), with mixed emotions producing a secondary emotion (e.g., anger and disgust produce hostility). Models based on the discrete emotions approach appeared, mapping emotions on different dimensions of valence and arousal [ 36 ]. On the other hand, the dimensional theory of emotions classifies emotions based on three main dimensions: (a) valance, (b) arousal and (c) dominance. Hence, emotions can be positive or negative, highly aroused or calm and dominating or under control. Application of the dimensional theory is seen in testing different emotional appeals in advertising with positive emotional appeals and negative emotional appeals, and more recently a mixture of both valanced appeals (i.e., coactive appeals) [ 1 , 7 , 37 ]. The dimensional theory allows for valid comparison of different advertising strategies and appeals and has proven to be valid in multiple empirical results [ 38 , 39 , 40 ]. Hence, the current study employs the dimensional theory of emotions in classifying emotional appeals.

Based on the dimensional theory of emotions, people can perceive any emotional appeal stimulus as pleasant, unpleasant or a mixture of both (i.e., coactive state) [ 41 ]. Hence, emotional appeals are categorized as positive, negative and coactive based on the valance of employed emotions. Emotional appeals research employing the dimensional theory of emotions focuses on the effect of different valanced emotions on cognitive and behavioral actions [ 42 ]. While there is a strong connection between emotional appeals and behavior change [ 43 ], inconsistent results are evident in the literature when comparing positive, negative and coactive appeals (e.g., [ 7 , 8 , 17 , 44 , 45 ]).

2.2. Positive, Negative and Coactive Appeals

While positive emotional appeals were found to increase an individual’s tendency to take action and yield higher message liking [ 9 , 46 ], they are explored and utilized to a lesser extent when contrasted with negative emotional appeals [ 47 , 48 , 49 ]. When positive appeals are studied, humor appeals remain the focus, with less attention directed to the utilization of other positive emotional appeals which may deliver behavioral change [ 9 ]. A review of the literature indicates that positive appeals hold a persuasive advantage in both social and commercial behavior. Wang et al. [ 50 ] found positive admiration appeals to increase purchase intentions more than negative appeals. Similarly, Vaala et al. [ 51 ] support the use of positive empowering appeals when targeting health-related behavior. Positive appeals are especially effective when targeting males [ 52 ], however, studies of positive appeal effectiveness remain limited in number and in execution [ 47 , 48 ]. Some limitations in positive appeals are discussed in the literature. Segev and Fernandes [ 53 ] found positive appeals to be only effective when the behavior requires low effort. Hence, when environmental or climate change advertisements encourage green consumption, recycling or other complex behaviors, positive appeals might be less effective. Similarly, when positive appeals are used to evoke hope in audiences, hope for change is reported in the viewers instead of action taken towards change, indicating an emotion-focused coping function [ 54 ]. Hence, social advertisers remain reluctant to apply positive approaches. Fewer examples of positive appeals being applied to address social issues such as alcohol consumption [ 55 ], obesity [ 56 ], the environment [ 52 ] and safe driving behaviors [ 17 ] are evident.

Negative appeals, on the other hand, dominate research and practice, with over 70% of social advertisements employing negative appeals [ 48 ]. As the main driver of psychic discomfort, negative appeals are utilized to create emotional imbalance to stimulate behavior change [ 57 ]. According to this view, a message that is negatively framed when aiming to drive donations to charities is designed to make the individual feel uncomfortable as they are blamed for the poverty of certain groups (e.g., homeless children). To eliminate such feelings, a viewer is then more likely to contribute to the solution by donating to the charity [ 58 ]. While the use of negative appeals has been found to be effective in multiple contexts, such as healthy eating [ 56 ], moderate alcohol consumption [ 55 ] and safe driving [ 17 ], certain limitations apply. Negative appeals result in developing a coping mechanism such as ignoring the message (i.e., flight) or rejecting the message (i.e., fight), reducing message effectiveness [ 30 , 31 , 59 ]. Furthermore, negative appeals dominate social advertising efforts [ 47 , 48 ], resulting in desensitization to negative emotions, potentially causing such appeals to become less effective [ 57 ]. Finally, negative appeals can serve to reinforce stereotypes, further stigmatizing some people which can lead to reactance in some areas of the community [ 16 ].

Appeals utilizing both positive and negative emotions are labeled inconsistently in the literature. For example, Hong and Lee [ 60 ] and Taute et al. [ 61 ] employ the term mixed emotional appeals while others utilized the term coactive appeal [ 7 , 8 , 62 , 63 , 64 ]. The current study employs the term coactive appeals as coactivity is used to explain the mixed state of emotions and is applied more heavily in the marketing communication literature [ 8 , 62 , 64 ]. When comparing single appeals with coactive appeals that feature an emotional shift (e.g., from positive to negative), coactive appeals were found to be more effective [ 65 , 66 ]. Hence, coactive appeals have recently gained research attention, with advertising studies including such appeals in their evaluations [ 7 ]. Coactive emotional appeals seek to induce both positive and negative emotions simultaneously or as a flow from one appeal to the other [ 42 , 49 ]. For example, a coactive message can take the viewer on an emotional journey either from negative to positive or from positive to negative. The use of a negative to positive emotional flow or a threat–relief emotional message is hypothesized to result in a stronger persuasion outcome [ 49 ]. A recent study by Gebreselassie Andinet and Bougie [ 67 ] found the flow from negative to positive appeals produced more desirable results than negative or positive appeals alone. Similarly, Rossiter and Thornton [ 68 ] found fear–relief appeals to reduce young adults’ speed choice when driving. This is due to positive appeals’ ability to reduce different defensive reactions (e.g., fight, flight) that negative appeals generate. When a positive appeal is added to a negative appeal, post-exposure discomfort is reduced, resulting in the combination of appeals (i.e., coactive) being more effective in changing behavior [ 66 , 69 , 70 ]. Nonetheless, negative appeals remain highly featured in social advertising messages. This is attributed to the rich action tendency potential negative appeals hold [ 71 ], along with their ability to activate the brain more than other emotions [ 72 ]. Negative appeals have the ability to drive action without being liked first. This explains their dominance in social advertising messages and heavy focus in the literature. No known study has empirically tested and contrasted the effectiveness of a coactive appeal with positive and negative appeals directly on social media platforms. Previously studies compared the three appeals using self-report data collection measures, an approach that is limited by social desirability effects [ 73 ]. This study eliminates such limitations by utilizing social media advertising tools and measures where data are collected based on the viewer’s actual reactions on the platform (e.g., likes and clicks) rather than intentions to perform such reactions [ 1 , 74 ].

2.3. Theory

This study applies and builds on the multi-actor engagement framework proposed by Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ]. The framework provides an “integrated, dynamic and measurable framework for managing customer engagement on social media” enabling marketers to understand the different levels of engagement and measure the success of their campaigns [ 10 ]. As social media grows beyond simple dyadic exchanges between customers and companies, the multi-actor engagement framework operationalizes the different levels of engagement in a multi-actor ecosystem where customers, fans, organizations and stakeholders all contribute to levels of engagement with content. The different levels of engagement set by Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] include connection, interaction, loyalty and advocacy. Connection is defined as a one-way communication where content is presented to customers without any action taken by the customer. When the stimulus attracts a customer’s attention, connection is achieved. In other words, Schivinski et al. [ 75 ] label this level as the consumption stage where social media users consume content but do not necessarily interact with it. At this level, customers passively consume the online content without taking any action yet [ 75 , 76 ]. Based on the Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] framework, this level is measured by reach and impressions. Reach is defined as the number of unique users who viewed an advertisement, while impressions are recorded every time an ad is viewed, including multiple views by the same user [ 77 ]. The next level in the Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] framework is interaction, and this level highlights the beginning of two-way communication between different actors, including customers, organizations and other customers. At this level, users engage with the advertisement by interactively contributing to the advertised message [ 75 ]. Social media interaction can be defined as “the number of participant interactions stratified by interaction type” [ 78 ]. Interaction types include likes, comments, clicks and overall engagement which are utilized to measure this level following the Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] framework. The third level in the Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] framework is loyalty, where interaction is repeated over time. A user is regarded as loyal if they are consistently seen interacting and contributing to an organization’s advertisements and content on social media. To encourage loyalty on social media, an organization’s content should aspire to complement the user’s image, as this will increase the chances of interactions over time and sharing with others [ 79 ]. This level is measured by multiple comments and messages in the Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] framework. Finally, advocacy marks the fourth and highest level of engagement. Advocacy is recorded when customers spread an organization’s message by generating new content through their networks. Advocacy is where interaction is sustained, and support moves beyond the dyadic nature, reaching users’ own networks. This is when users share organizations’ content with their community circles through their own pages, profiles and networks [ 80 ]. Following the Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] framework, this level is measured by shares, tagging of others on a post and word of mouth. The last two levels are parallel to Schivinski, Christodoulides and Dabrowski [ 75 ] creation level where users generate and create content. This is regarded as the highest level of online engagement as it motivates future interaction and involvement with the organization online and offline [ 76 ].

The multi-actor engagement framework stops at advocacy as the highest level of engagement. As a result of our study, we propose a fifth level which marks the transition from online engagement to behavior. The fifth level signifies the customer’s action beyond social media platforms, and this can be reflected by purchases, donations, registrations, signatures on a petition and many other actions. While previous studies explore advertising effectiveness with customer perceptions such as attitudes, memorability, likability of the ad and intentions to take action, the direct effect of advertising on behavior, specifically in a social media context, is yet to be explored [ 71 ]. This is now possible with methodological advances and digital and social media platforms that allow for experiments to track not only automated measures on social media (e.g., likes and shares), but further action taken beyond such platforms (e.g., filling lead form, visiting a store, buying a product) [ 71 ]. This is of specific interest to advertisers employing emotional appeals, as each emotion has different action tendencies which influence the audience behavior after being exposed to the emotional advertisement appeal. As Poels and Dewitte [ 71 ] explain, different emotional appeals “help the individual sort out which action tendency is the most functional in this situation”. Each behavior is tracked differently, for example, weight loss campaigns can be tracked through the audience’s eating habits and exercise patterns, while antitobacco campaigns may track cigarette purchases, hence, this level has a number of possible measures. If measuring purchases of a product or donations to an online charity, the click through rate to the product or the donation page along with the number of orders or the amount of donations are examples of measures that reflect actions. For the purpose of this study, we measure actions through the number of requests to receive a donation sorting bag that helps reduce textile waste. The extended model is shown in Figure 1 .

The extended multi-actor engagement framework [ 10 ].

Past literature identified that positive advertising appeals produce an emotion-focused coping mechanism, while negative appeals create emotional imbalance to stimulate behavior change, and coactive appeals may reduce defensive reactions with less evidence of effectiveness in creating behavior change. For the purpose of the current study, we focus on four online behavioral outcomes. First, connection is defined by reach. Second, interaction is defined by engagement, likes, comments and clicks. Third, loyalty is defined by repeated actions on the ad. Finally, advocacy is defined by sharing the ad. Guided by past research, the current study expects negative advertising appeals to be more effective in evoking online behavioral responses than positive and coactive message on social media. Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Negative advertising appeals will achieve more interactions than positive and coactive advertising appeals on social media .

Negative advertising appeals will achieve more loyalty than positive and coactive advertising appeals on social media .

Negative advertising appeals will achieve more advocacy than positive and coactive advertising appeals on social media .

Negative advertising appeals will achieve more behavior actions than positive and coactive advertising appeals on social media .

2.4. Gaps and Aims

This study aims to address three main gaps in the literature. First, the need for a social media advertisement evaluation model that addresses both online engagement as well as behavior actions which is addressed through an empirical study. Second, the evaluation of social media advertisements has been limited by self-reported measures of intentions to engage with advertisements (e.g., intention to click, like, share) [ 81 ], neglecting actual engagement measures (e.g., comments, reactions, shares, likes and ad clicks) that can be directly observed in social media. Third, current evidence on social media advertising appeals’ effectiveness in engagement and changing behavior remains conflicted, inconsistent and fragmented. Such gaps create a challenge for researchers aiming to understand social media advertising appeal effectiveness and advertisers, given that limited guidance is available to provide an implementation roadmap that can be relied upon to deliver behavior change benefitting people. This study addresses the aforementioned gaps testing the capacity of positive, negative and coactive advertising appeals to engage audiences on social media and drive behavioral actions.

3. Material and Methods

The current study employed an experimental study design, where three advertising appeals (positive, negative and coactive) were designed following Alhabash, McAlister, Hagerstrom, Quilliam, Rifon and Richards [ 7 ] and Hong and Lee [ 60 ] and published on Facebook following a pre-test conducted with a participant panel ( n = 10).

3.1. Pre-Test

An online survey was distributed featuring the three advertisements. After exposure to each ad, participants were asked to rate how the advertisement made them feel on a 7-point scale (mostly positive/mostly negative) [ 82 ]. Next, participants were asked to describe how the advertisements made them feel in one word. The three ads maintained similarities in visuals and manipulated verbal elements to represent each appeal. The pre-test included one between-subjects ANOVA to compare advertisements’ emotional valance and a sentiment analysis of each advertisement response. The aim was to ensure that the positive advertisements were rated as more positive than the negative and coactive advertisements, the negative advertisements more negative than positive and coactive advertisements and the coactive advertisements in the middle. Moreover, the pre-test included a sentiment analysis of participants’ feedback on each advertisement. Word maps were generated and analyzed to confirm each ad represented the respective appeal.

3.2. Social Media Advertisements

After the pre-test, the three advertisements were published on Facebook and promoted for a week, controlling for the reach (i.e., number of people who were presented with the ad) of each advertisement through Facebook’s A/B testing tool on Facebook ads manager. The A/B testing tool allows for a comparable data set between the tested advertisements by controlling for reach across the different groups along with demographic elements (e.g., gender). Facebook ads manager allows for extraction of advertisements’ performance data as a spreadsheet, which was then used by the research team to analyze advertising appeal effectiveness using SPSS v.25. Facebook records advertisements’ performance data in key metrics including reach, likes, comments and shares. The ad appeared to Facebook users on their news feed as they scrolled through the content. The published ads (see Table 1 ) were linked to a charity website. One aim of the website is to educate people on what to donate to increase the quality of donations for Australian charities. When landing on the website, customers were asked to fill in a form to request a cloth sorting bag for their donations. Each form submission was recorded, and web data were extracted for all form submissions when the campaign was over. The research procedure is outlined in Figure 2 .

Research procedure.

Overview of employed stimulus.

3.3. Analysis and Measures

The three advertisements employed in this study were analyzed using Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] multi-actor social media engagement framework. When customers viewed the advertisement, reach was recorded. When a customer liked or reacted to or clicked on an ad, interaction was recorded. When customers commented multiple times or replied to others to clarify the message or provide information, loyalty was recorded. When users shared the advertisement, advocacy was recorded. Finally, when customers filled in the form on the charity website, action was recorded. The form was created as a lead capture tool where customers filled in their information (e.g., name, address, contact details) to request a donation bag they could use to take their donations to charities. Three separate forms were created with three links for each advertising appeal. Data of each ad’s performance were extracted from Facebook ads manager while data of all request forms were extracted from the website after the ads on Facebook ended and were analyzed based on the number of requests received on each form. Following Merchant, Weibel, Patrick, Fowler, Norman, Gupta, Servetas, Calfas, Raste, Pina, Donohue, Griswold and Marshall [ 78 ], the data received were analyzed as categorical (out of all users reached, ad was liked: yes or no, ad was clicked on: yes or no) and continuous in the sense how many liked, clicked, commented. A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relation between advertising appeal and Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] engagement levels: connection, interaction, loyalty, advocacy and the fifth proposed level of behavior, using SPSS v.25.

A sample of ten participants was achieved for the pre-test with a mean age of 24 and balanced gender (50% females). Using SPSS v.25, pre-tests were successful for all advertising appeals. There was a statistically significant difference between group means showing a significant effect of appeal type on emotional valence (mostly positive/mostly negative) at the p < 0.05 level as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(2,27) = 199.957, p = 0.00). Post hoc analyses were conducted using Tukey’s post hoc test. The test showed that the three advertising appeal groups differed significantly at p < 0.05. The positive appeal ad (M = 6.60, SD = 0.52) was significantly more positive than the negative ad (M = 1.40, SD = 0.51) and the coactive ad (M = 4.40, SD = 0.69). Similarly, the negative ad (M = 1.40, SD = 0.51) was significantly more negative than the positive (M = 6.60, SD = 0.52) and coactive ads (M = 4.40, SD = 0.69). The coactive ad means appear in the middle as their mean scores were mostly neutral compared to the other two categories of emotional tone (see Figure 3 ). This result indicated that in the coactive condition, participants perceived the advertisement as both positive and negative at the same time, reflecting the bi-dimensional nature of the appeal (negative and positive).

Pre-test mean scores of emotional valences.

The sentiment analysis showed that the positive appeal was perceived as mostly hopeful, the negative mostly shameful and the coactive was perceived as motivational. Figure 4 showcases the word map for each advertisement.

Word map based on sentiment analysis.

4.1. Social Media Advertisements

The three promoted appeals achieved a total of 23,905 impressions and reached 21,054 users which resulted in 787 clicks to the website. Facebook ads manager targeted a balanced sample for the three promoted appeals by using its A/B testing tool. The three ads reached Facebook users above 18 years of age of both genders (see Figure 5 and Figure 6 ). While the overall sample is female skewed (see Figure 6 ), each advertising appeal achieved a balanced reach for both genders (see Figure 7 ). The click through rate achieved through the three ads of 3.28% is considered above the average of 1.24% for Facebook ads [ 83 ]. A total of 28 requests were received for donation bags through the website forms. The results for each advertising appeal are discussed next.

Gender distribution across the three ads.

Gender distribution across advertisements.

Distribution of females across the three appeals.

4.1.1. Connection

Connection was measured through reach and was controlled between the three appeal ads to ensure applicable comparison (see Table 2 ). A chi-square test of independence revealed an insignificant effect of appeal type on reach between the three advertisements χ 2 (2, N = 21,054) = 4.57, p = 0.11.

Number of people reached compared to impressions on positive, negative and coactive appeals.

4.1.2. Interaction

Appeal type had a significant effect on the level of interaction. This is evident through all three measures: clicks, engagement and comments (see Table 3 ). The negative appeal ad had significantly more engagement than the positive and coactive appeals. A chi-square test of independence showed significance for clicks χ 2 (2, N = 21,054) = 18.57 p < 0.05, and engagement χ 2 (2, N = 21,054) = 20.68 p < 0.05. No significant difference was observed for comments χ 2 (2, N = 21,054) = 4.94 p < 1, partially supporting H1. When comparing clicks on the positive and coactive appeals, no statistical significance was recorded at the 0.05 level χ 2 (1, N = 13,851) = 1.49 p = 1.11. Similarly, effect was insignificant when comparing engagement χ 2 (1, N = 13,851) = 1.48 p = 1.15 and comments χ 2 (1, N = 13,851) = 1.02 p = 0.3 between positive and coactive appeals.

Number of interactions on positive, negative and coactive appeals.

4.1.3. Loyalty

No repeated interaction was recorded for any of the three advertising appeals (see Table 4 ). Therefore, appeal type had no effect on level of loyalty. Hence, H2 was not supported.

Number of repeated interactions on positive, negative and coactive appeals.

4.1.4. Advocacy

A chi-square test of independence showed no significant effect of appeal type on advocacy (see Table 5 ). This is seen in the number of shares the three appeals received χ 2 (2, N = 21,054) = 1.82 p = 0.40. Hence, H3 was not supported.

Number of shares on positive, negative and coactive appeals.

4.1.5. Behavior

Behavior was measured through the number of requests for a donation sorting bag received for each advertising appeal. The negative appeal achieved the highest number of requests, followed by positive and coactive appeals (see Table 6 ). A chi-square test of independence showed a significant difference for appeal type based on the number of bag requests χ 2 (2, N = 21,054) = 6.54 p < 0.05, supporting H4.

Number of requests on positive, negative and coactive appeals.

5. Discussion

The current study contributes to the literature in three ways. Firstly, we tested positive, negative and coactive appeals’ effectiveness on social media to understand their effect on engagement and behavior. This is the first study to directly examine advertising appeals on social media without the use of self-report measures. Our findings support the use of negative appeals over positive and coactive appeals when aiming to drive engagement and change behavior. This provides clear guidance for practitioners aiming to create effective social advertisement messages on social media. Secondly, this is the first study to apply and build on the Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] social media multi-actor engagement framework in testing advertising appeals’ effectiveness. Our findings support the use of the framework in testing advertising effectiveness and show clear measures for each level of engagement. Finally, the study proposed an extension to the social media multi-actor engagement framework [ 10 ] with a clear and practical way of measuring actions beyond social media engagement. This will enable social advertisers to measure advertising effectiveness on actual behavior, moving beyond indirect behavioral measures such as attitudes, norms and intentions. Each contribution will be discussed in detail next.

5.1. Negativity Increases Appeals’ Effectiveness

When comparing positive, negative and coactive appeals’ performance in driving engagement and action on social media, our findings suggest negative appeals hold a persuasive advantage (see Figure 8 ). This is evident in the significant increase in engagement and actions for the negative advertisements when compared with the positive and coactive advertising appeals. This is consistent with previous findings, especially with behavior related to charities [ 18 , 84 ] and the environment [ 52 , 85 ]. Our findings support the limited effectiveness of positive appeals when complex issues are discussed. The advertisements employed by the current study address the issue of waste and its impact on the planet, where positive appeals have been found to be less effective in the past [ 54 ].

Comparison of advertising appeal performance.

The effectiveness of coactive appeals has not been tested directly on social media before, marking a significant contribution of this study. Interestingly, the coactive appeal was equally effective when compared to positive appeals in attracting comments, and driving loyalty, advocacy and behavioral actions. The findings in this study indicate that both positive and coactive appeals performed in a similar way, contradicting previous findings supporting positive appeals’ effectiveness over coactive appeals [ 7 ]. The limited effectiveness of both positive and coactive appeals in this study may be attributed to the advertising platform.

5.2. Platform Effect on Appeal Effectiveness

Social media advertising engagement differs across social media platforms [ 86 , 87 ]. To understand why negative appeals were most effective in our experiment, a review of the platform of choice (i.e., Facebook) was necessary. Evidence suggests Facebook is among the most negative platforms in nature. Voorveld, van Noort, Muntinga and Bronner [ 86 ] explain the implications of such findings by relating them to advertising valence (i.e., appeals). Hence, when advertising on Facebook, advertisements that evoke negative feelings (i.e., negative appeals) perform best. The effectiveness of such appeals stems from the fluency between advertising appeal and platform nature [ 87 ]. Platform–appeal fit was found to increase the effectiveness of advertising and drive higher rates of engagement [ 87 ]. In fact, Facebook ran an experiment in 2014, where content was manipulated for half a million users. The experiment tested whether what users share is affected by what they see in their newsfeed. The findings supported the concept of platform–appeal fit. When negative content was increased in users’ feeds, their posts became more negative as a result [ 88 ]. Recently, Facebook was criticized for carrying out such experiments, which can have an impact on mental health, personal decisions and in many cases political election outcomes [ 89 ]. All of this results in users’ skepticism of the platform, contributing to its negative nature.

5.3. Driving Action Beyond Social Media Engagement

The current study applies and builds on the Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] social media multi- actor engagement framework. The framework provides a practical tool for organizations seeking to evaluate their social media content. This study applies the framework, testing advertising appeals’ effectiveness, an application of the framework that has not previously occurred. It showcases the ability to use the Shawky, Kubacki, Dietrich and Weaven [ 10 ] framework as a tool to evaluate social media advertising effectiveness in driving engagement and prosocial behaviors. While the framework proved to be a practical and easy measurement tool for advertisers, it has a key limitation when aiming to carry out a thorough evaluation of advertising messages’ capacity to drive action. Linking online engagement to behavior remains limited when evaluating social media advertising effectiveness. Hence, an extension to the model is proposed, where behavior is measured through action (e.g., donations), extending understanding beyond social media engagement (see Figure 9 ). This extension could be tested empirically, allowing actions taken to be observed and analyzed. Behavior could be measured as a fifth step in Shawky et al.’s framework.

Proposed extension to Shawky et al. (2020) social media multi-actor engagement framework.

Negative appeals achieved the highest actions, while positive and coactive appeals received equal actions from users. This could be explained by the emotion-focused coping function, where positive emotions produce a hope for change rather than inducing a motivation to take action [ 54 ]. Furthermore, when viewers hold favorable prior attitudes towards the advertised behavior (i.e., reduce waste) positive appeals are found to be less effective [ 90 ]. While there are no data on prior attitudes of the viewers for this experiment, the comments received about the negative appeal advertisement suggest some people are passionate about the environment, and they want to take actions to help others and reduce waste. Hence, negative appeals were more effective in driving both engagement and action.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Three main limitations apply to this study. First, mediators of effectiveness, such as prior attitude towards the issue, were not examined in this study. Future research is recommended to employ a pre-exposure survey to collect such data or utilize social media targeting tools to target specific audiences with certain interests. Second, the advertisements tested in this study were shared predominantly on Facebook where negative content dominates. Future research should investigate other platforms to understand the effects that social media platforms exert on advertising appeal effectiveness. Empirical tests of different appeals on multiple platforms (e.g., Twitter, TikTok, Snapchat) are needed to draw conclusions on where different appeals perform best. Third, the sample reached by this study may be small when compared to other studies in social media settings [ 91 ], and future research may increase the reach by increasing the budget invested in the advertising campaign on Facebook.

It is important to note that different contexts may achieve different results, and the experiment can be replicated to understand if other behaviors, such as the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine, are more effectively achieved through negative advertising appeals. Research shows a promising effect of emotional appeals in both social and health domains, with more empirical evidence needed [ 92 ]. Future research may investigate the role of social media advertisements in inspiring loyalty and advocacy through different emotional appeals. The current study found no effect of appeal type on loyalty and advocacy, presenting a limitation to the overall findings. To increase analytic rigor, future research may employ a CB/PLS-SEM approach to test social media advertising’s effect on behavior [ 93 ].

6. Conclusions

This study examined positive, negative and coactive advertising appeals’ effectiveness in driving engagement and actions on and beyond social media platforms. Findings support the use of negative advertising appeals over positive and coactive appeals. The results highlight how negative appeals on social media advertising in an environmental and charity context can deliver superior outcomes to engage more people and positively impact social behavior. Theoretically, this study highlights the value of using Shawky et al.’s (2020) multi-actor social media engagement framework to test social advertising appeal effectiveness and provides a practical extension to evaluate behavioral outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Y., T.D. and S.R.-T.; methodology, M.Y.; software, M.Y. and T.D.; validation, M.Y., S.R.-T. and T.D.; formal analysis, M.Y.; investigation, M.Y.; resources, M.Y.; data curation, M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y.; writing—review and editing, M.Y., T.D. and S.R.-T.; visualization, M.Y.; supervision, T.D. and S.R.-T.; project administration, M.Y. and T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee of Griffith University (protocol code 2019/697 and date of approval 3 September 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The impact of interactive advertising on consumer engagement, recall, and understanding: A scoping systematic review for informing regulatory science

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation RTI International, Research Triangle Park, Durham, NC, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Data curation, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Office of Prescription Drug Promotion, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Kristen Giombi,

- Catherine Viator,

- Juliana Hoover,

- Janice Tzeng,

- Helen W. Sullivan,

- Amie C. O’Donoghue,

- Brian G. Southwell,

- Leila C. Kahwati

- Published: February 3, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263339

- Reader Comments

We conducted a scoping systematic review with respect to how consumer engagement with interactive advertising is evaluated and if interactive features influence consumer recall, awareness, or comprehension of product claims and risk disclosures for informing regulatory science. MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Business Source Corporate, and SCOPUS were searched for original research published from 1997 through February 2021. Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and full-text articles for inclusion. Outcomes were abstracted into a structured abstraction form. We included 32 studies overall. The types of interactive ads evaluated included website banner and pop up ads, search engine ads, interactive TV ads, advergames, product websites, digital magazine ads, and ads on social network sites. Twenty-three studies reported objective measures of engagement using observational analyses or laboratory-based experiments. In nine studies evaluating the association between different interactivity features and outcomes, the evidence was mixed on whether more interactivity improves or worsens recall and comprehension. Studies vary with respect to populations, designs, ads evaluated, and outcomes assessed.

Citation: Giombi K, Viator C, Hoover J, Tzeng J, Sullivan HW, O’Donoghue AC, et al. (2022) The impact of interactive advertising on consumer engagement, recall, and understanding: A scoping systematic review for informing regulatory science. PLoS ONE 17(2): e0263339. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263339

Editor: Qihong Liu, University of Oklahama Norman Campus: The University of Oklahoma, UNITED STATES

Received: September 15, 2021; Accepted: January 15, 2022; Published: February 3, 2022

This is an open access article, free of all copyright, and may be freely reproduced, distributed, transmitted, modified, built upon, or otherwise used by anyone for any lawful purpose. The work is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 public domain dedication.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: Funded through a contract from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to RTI International (Contract 75F40120A00017, Order Number 75F40120F19003). KG, CV, JH, JT, BS, LK are employees of RTI International. HS and AO are employees of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. HS and AO (employees of the sponsor) participated in the study design, decision to publish, and critically reviewed the manuscript prior to submission.

Competing interests: HS and AO are employees of the study sponsor. This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

1. Introduction

In 2020, it is estimated that nearly $356 billion was spent on digital advertising in the United States [ 1 ]. Much of this advertising consists of display ads, social media ads, search engine marketing, and email marketing often with interactive components to target the 85% of US adults who go online daily [ 2 ]. An interactive ad encourages consumers to interact with the ad (and thus the brand), rather than just passively view the ad. Although interactivity is often considered a vital element of successful online advertising [ 3 , 4 ], its impact on consumer engagement and decision-making is not entirely clear.

The academic definition of interactive advertising has evolved and varied at least in part as possibilities for ad design and placement have shifted, meaning interactive advertising can be defined differently depending on the context. Experts have defined interactive ads in terms of processes, features, and/or user perceptions, and no consensus about the definition has been reached to date [ 5 – 14 ]. Conceptual frameworks considered by researchers in approaching interactive advertising have tended to include descriptions of how users behave in response to ads [ 13 , 15 – 17 ]. Metrics employed by the advertising industry also have shifted over time. The operationalization of interactive advertising often has been determined by the conceptual framework used and the outcome of interest to the researcher.

With an increased presence of interactive advertising in digital and social media [ 18 ], it is critical to understand how consumers engage with these types of advertisements and whether interactive features influence consumer recall, awareness, or comprehension of product claims and risk disclosures. This is of particular importance for products or services for which advertising content is regulated, such as prescription drugs, alcohol, tobacco, and financial products or services, to ensure that such advertising does not introduce barriers or challenges to consumer understanding of risks associated with such products. Especially within the past decade, regulatory science researchers have embraced the tools of social science to assess consumer perceptions of risk as well as potential impediments to consumer understanding [ 19 , 20 ]. Social science research can offer evidence of advertising effects on consumer perceptions, and agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration have used such approaches to assess consumer engagement with different types of advertisements, such as direct-to-consumer prescription drug television ads [ 21 ]. In order to assess whether interactive advertising poses new theoretical challenges or opportunities, we conducted a scoping systematic review to summarize the research related to consumer engagement with interactive advertisements and impact on recall and understanding of product claims and risk disclosures.

The protocol for this scoping review was registered at Open Science Framework on October 26, 2020 [ 22 ]. The goal of this scoping systematic review was to describe the extant literature on interactive advertising and consumer engagement, particularly as it concerned regulated product advertising and its influence on comprehension of product claims and risk disclosures. We designed the four research questions (RQs) that guided this scoping review to identify gaps in the evidence base and summarize important considerations needed to inform the design and conduct of future primary research studies in this area. The four RQs were:

- RQ 1: What methods and measures are used to evaluate consumer engagement with interactive advertisements in empirical studies?

- RQ 2: In empirical studies of interactive advertising in naturalistic or real-world contexts, to what extent do consumers engage with interactive advertisements?

- RQ 3: What is the association between features of interactive advertisements for goods or services and consumer engagement, recall, awareness, or comprehension of product claims and risk disclosures?

- RQ 4: How do interactive advertisements for goods and services compare to non-interactive advertisements (e.g., traditional print or broadcast advertisements) with respect to consumer engagement, recall, awareness, and comprehension of product claims and risk disclosures?

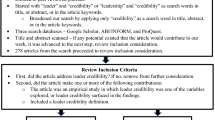

2.1 Search and data sources

We searched MEDLINE via PubMed, PsycINFO, Business Source Corporate, and SCOPUS for original research published in English from January 1, 1997, through February 17, 2021, using search terms related to advertising and marketing, internet, and the outcomes of interest (e.g., engagement, knowledge, click-through rate). Little research on digital advertising was conducted prior to the mid-1990s, and our preliminary evidence scan showed very few papers published prior to 1997. The detailed search strategy is in S1 Appendix . We also searched reference lists of systematic and narrative reviews and editorials where relevant.

2.2 Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and full-text articles for inclusion based on study selection criteria for each research question. Disagreements at the full-text review stage were resolved by a third reviewer. Detailed study selection criteria are described in S2 Appendix . In brief, we included all studies among persons of any age in the general public who were characterized as being a potential consumer target for interactive advertising. For all RQs, we included studies that examined exposure to interactive advertisements, which we defined as the promotion of a product, service, or idea using various features or tools that provide the opportunity for persons to interact directly with the ad and potentially influence/inform the remaining sequence, appearance, or content to be presented about the product, service, or idea. For RQ 2, we included only studies with exposure to interactive advertising in naturalistic or real-world contexts. For RQ 3, studies that compared alternative versions of advertisements with interactive elements that varied with respect to the type or level of interactivity were selected. For RQ 4, studies that compared interactive advertisements with traditional advertising (i.e., print ads, broadcast ads, or online/internet ads without interactive elements) were included.

Eligible outcomes varied by RQ. For RQ 1, we included studies with any measure of consumer engagement. For RQ 2, we required objective measures of engagement such as time spent viewing, content navigation, click-through rates, page views, shares, likes, or leaving comments. For RQs 3 and 4, we required studies to report outcomes including consumer recall, awareness, and comprehension of product claims, risk disclosures, or both. Lastly, we included only studies conducted in countries designated as very highly developed per the United Nations Human Development Index to maximize applicability to decision-makers in such settings [ 23 ].

2.3 Data abstraction and synthesis

For each article included, one reviewer abstracted relevant study characteristics and outcomes into a structured abstraction form, and a second senior reviewer checked the form for completeness and accuracy. We narratively synthesized findings for each RQ by summarizing the characteristics and results of the included studies in narrative and tabular formats. Because this was designed as a scoping review, we did not conduct risk of bias assessments on included studies, quantitatively synthesize findings, or conduct strength of evidence assessments.

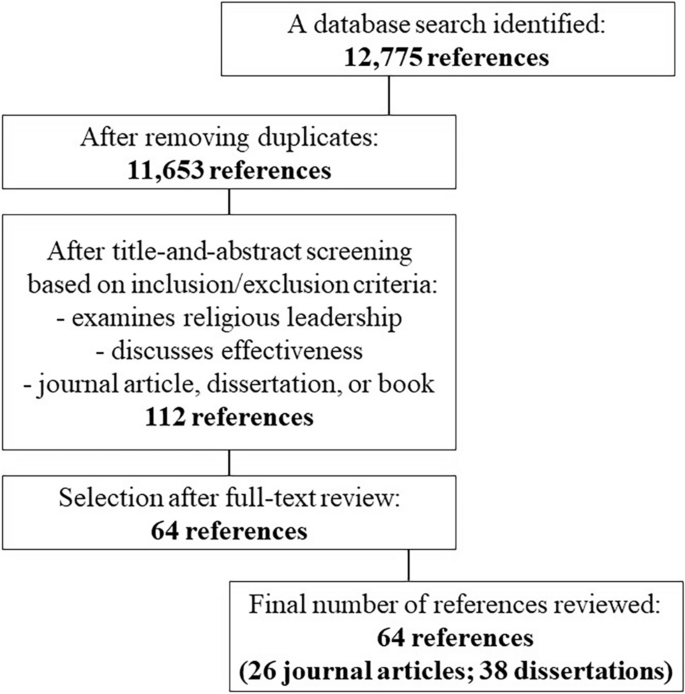

We screened 3,765 titles and abstracts and 136 full-text articles. We included 32 studies published in 33 articles ( Fig 1 ) [ 7 , 24 – 55 ]. Twenty-three studies addressed RQ 1, eight studies addressed RQ 2, nine studies addressed RQ 3, and four studies addressed RQ 4. An overview of included studies is provided in Table S4-1 in S4 Appendix . A list of full-text studies that we reviewed and excluded is provided in the S3 Appendix .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263339.g001

3.1 Research question 1: What methods and measures are used to evaluate consumer engagement with interactive advertisements in empirical studies?

3.1.1 study characteristics..

We identified 23 studies eligible for RQ 1 that were published between the years 1997 and 2019 and conducted across multiple countries [ 24 – 30 , 33 , 35 – 42 , 46 , 47 , 50 – 53 ]. An overview of the studies is in Table S4-1 and S4-2 in S4 Appendix . Six were observational studies evaluating consumer response to real-world advertisements or campaigns [ 24 , 25 , 28 – 30 , 37 ]. The rest of the studies were experiments conducted in laboratory or controlled environments. The sample sizes across the included studies ranged from 20 to 116,168 participants; however, two studies [ 29 , 30 ] did not report the number of persons participating in the study.

The types of interactive advertisements evaluated varied across the included studies. Six studies [ 26 , 33 , 35 , 40 , 47 , 50 ] evaluated banner ads, three studies [ 7 , 36 , 46 ] evaluated product websites, three studies [ 29 , 30 , 41 ] evaluated paid search engine ads, three studies [ 38 , 51 , 52 ] evaluated interactive television ads, two studies [ 24 , 27 ] evaluated social network site ads, one study [ 39 ] evaluated a pop-up ad and the rest of the studies evaluated other types of digital ads. This included short-message-service TV marketing [ 37 ], an ad with a video clip embedded in a digital magazine [ 42 ], ads within a simulated online store [ 53 ], and combinations of different types of digital and online ads [ 25 , 30 ]. The type of products advertised across the included studies included unregulated consumer products (e.g., digital cameras) and services (e.g., travel planning); regulated products and services (car insurance, financial); and health/health behavior campaigns.

3.1.2 Findings.

An overview of findings is in Fig 2 . Authors of the six observational studies reported engagement outcomes associated with real-world advertising or marketing campaigns [ 24 , 25 , 28 – 30 , 37 ]. Authors of four studies reported objective measures of the proportion of users exposed to an ad that clicked on the ad (i.e., “click-through rates”) by using platform-specific (e.g., Facebook, Google AdWords) analytic tools for advertisers [ 24 , 29 ], specialized web tracking software that members of a market research panel consented to have installed on their computers to monitor web behavior [ 28 ], or a unique event identifier created on the advertiser’s server whenever an online ad was clicked [ 30 ]. Authors of the other two observational studies reported subjective measures of engagement. In one study, authors used audio, computer-assisted self-interviews that asked respondents about their engagement with online marketing of a specific class of product [ 25 ]. In the other study, authors used post-campaign surveys (mode not specified) to evaluate engagement outcomes [ 37 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263339.g002

Authors of the 17 experimental studies reported engagement outcomes from experiments using actual real-world ads or from experiments using fictitious ads designed specifically for the experiment. Authors of the experimental studies controlled participant exposure to the ads, and depending on the measure, outcome measurement occurred either concurrently with the ad exposure or through completion of post-exposure surveys or interviews.

Two of the experimental studies used objective measures of ad engagement employing eye-tracking technologies during exposure to evaluate user engagement with digital ads placed on online platforms (Facebook page, blog, and industry-specific search engine) [ 26 , 50 ]. In Muñoz-Leiva, Hernández-Méndez, and Gómez-Carmona [ 26 ] the ads used were fictitious, and the sites they were placed on were mocked up to resemble existing platforms (e.g., Facebook). In Barreto [ 50 ], each participant’s own Facebook page and the authentic Facebook page for a specific brand of athletic shoe was used. In both studies, authors first calibrated the eye-tracking equipment for each participant, then assigned one or more tasks for the participants to complete (e.g., navigate to find a specific item). The eye-tracking technology measured fixation counts and duration of fixation on the ad portion of the screens as participants navigated through the task.

Seven of the experimental studies were designed using a within- or between-subjects randomized factorial design or both [ 27 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 41 , 51 , 52 ]. In these studies, authors manipulated two or more ad features, including message/information content, tone, amount, or presentation order; images; screen placement; and level of interactivity. Eight of the experimental studies were parallel-group randomized experiments with one group assigned to a manipulated ad exposure in one or more ways and the other group assigned to a control ad exposure [ 7 , 35 , 39 , 40 , 42 , 46 , 47 , 53 ]. In both types of experimental studies, measures of ad engagement varied and included both subjective (e.g., user intentions as to whether they would click the ad or like or share the ad post) and objective measures (e.g., actual click-through rates on ads encountered, view duration tracked by computer). Nearly all studies also measured additional outcomes such as attitudes toward ads, ad or brand recall, or purchase intentions through post-exposure surveys.

3.2 Research question 2: In empirical studies of interactive advertising in naturalistic or real-world contexts, to what extent do consumers engage with interactive advertisements?

3.2.1 study characteristics..

Eight studies addressed RQ 2; these were published between 2006 and 2019 (Table S4-3 in S4 Appendix ) [ 24 , 28 – 31 , 39 , 47 , 54 ]. Six were observational studies [ 24 , 28 – 31 , 54 ], and two studies were experimental but conducted in real-world (i.e., not laboratory) settings [ 39 , 47 ]. The sample sizes across the included studies ranged from 30,638 to 2,000,000 participants. The types of interactive advertisements evaluated varied and could include more than one type of ad. Three studies evaluated banner ads [ 28 , 30 , 47 ], two studies evaluated social network site ads [ 24 , 31 ], and one study evaluated a pop-up ad [ 39 ]. Three studies evaluated other types of digital ads including paid search engine ads and video ads [ 28 , 29 , 54 ]. The type of products advertised across the included studies included unregulated consumer products and services and health/health behavior campaigns.

Authors measured consumer engagement with click-through rates; page views; and/or number of “likes,” comments, or shares on social media. The two experimental studies analyzed click-through rates for banner and pop-up ads [ 39 , 47 ], while the six observational studies analyzed click-through rates for banner ads [ 28 , 30 ], search ads [ 28 – 30 , 54 ], and social media interaction [ 24 , 31 ].

3.2.2 Findings.

An overview of findings is in Fig 3 . The level of engagement by consumers varied across studies. Six studies reported click-through rates ranging from 0.02% to 2.30% [ 24 , 29 , 31 , 39 , 47 , 54 ]. Two of these studies also reported differences in click-through rates when selected characteristics of the ad were varied, such as differences on which page the ad was placed, a variable delay before the ad was displayed [ 39 ], or whether the ads were static or morphing and whether they were context matched to the website on which they were placed [ 47 ]. In contrast to other studies reporting click-through rates, Graham et al. [ 30 ] reported a much higher click-through rate (81.6%); this study used ads to recruit individuals to a website to register for smoking cessation treatment.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263339.g003

Other measures of consumer engagement beyond click-through rates included number of page views (after clicking through an ad) and interactions such as liking, sharing, or posting comments to ads on social networking platforms. Two studies measured page views, which is the number of pages the viewer visited after going to the landing site [ 29 , 39 ]. In Birnbaum et al. [ 29 ] the median number of pages visited on the website (not including other relevant websites that were linked on the study site) was 1.29. Moe [ 39 ] measured the difference in number of page views when users were exposed to the ad on a gateway page of an informational website compared with exposure to the ad from a content page of the website. The mean number of page views after an ad on a content page (6.31) was higher than page views after an ad on a gateway page (4.86, P < .001), suggesting greater engagement from consumers when involved in the content.

Two studies measured interactive engagement with social media ads through “likes” and shares [ 24 , 31 ]. Horrell et al. [ 24 ] defined levels of consumer engagement as “low” if a consumer liked a page or reacted to a post and “medium” if a consumer shared or commented on a post. Over a 5-week advertising campaign targeted to 91,385 users of a specific Facebook page site targeting lung cancer awareness, the page had 2,602 reactions to posts, 149 page likes, 452 shares, and 157 comments [ 24 ]. Similarly, Platt et al. [ 31 ] reported findings from a 1-month time period in which a Michigan biobank advertising campaign was targeted to an estimated 2 million state residents aged 18 to 28. The campaign’s social media presence garnered 516 page likes, 477 ad likes, 25 page post shares, and 30 entries into an advertised photo contest. This study also reported that a greater percentage of viewers clicked an ad or post they saw when it was associated with the name of a friend who had already liked the Facebook page [ 31 ].

3.3 Research question 3: What is the association between features of interactive advertisements for goods or services and consumer engagement, recall, awareness, or comprehension of product claims and risk disclosures?

3.3.1 study characteristics..

We identified nine studies eligible for RQ 3 that were published between the years 1997 and 2019 (Tables S4-4 and S4-5 in S4 Appendix ) [ 26 , 32 , 34 , 36 , 43 – 45 , 51 , 53 ]. Eight studies were conducted as experiments [ 26 , 32 , 34 , 36 , 43 , 44 , 51 , 53 ], and the remaining study was a meta-analysis [ 45 ]. The sample sizes across the included primary research studies ranged from 60 to 1,600 participants. The type of advertisements evaluated varied. Four studies [ 32 , 34 , 36 , 44 ] evaluated product websites, one study [ 26 ] evaluated banner ads, one study [ 43 ] evaluated both banner ads and advergames, and two studies [ 51 , 53 ] evaluated other types of digital ads (e.g., interactive TV ads and interactive ads in a simulated online store). The included studies manipulated the ad stimuli to vary the level of interactivity or the type of interactive features included in the ad. Interactive features used in these studies included clickable hyperlinks, navigation bars, navigation buttons, rollover and clickable animation, responsive chat features, comment forms, and interactive game elements. The type of products advertised across the included studies included unregulated consumer products and services as well as regulated products or services.

The meta-analysis reported on 63 experimental studies (total N = 13,484) that evaluated how web interactivity affects various psychological outcomes and how those effects are moderated [ 45 ]. Of the included studies, half focused on interactivity within an advertising context, and 25% reported cognition outcomes, the only outcomes of relevance to this review.

3.3.2 Findings.

An overview of findings is in Fig 4 . In the meta-analysis, Yang and Shen [ 45 ] defined cognition measures such as comprehension, elaboration, knowledge acquisition, and recall. The authors reported no significant association between interactivity and cognition (correlation coefficient 0.05, P = .25). Across the eight primary research studies for this RQ, outcomes varied widely by level or type of interactivity. Five of the studies measured consumer recall of the brand, product, or service advertised [ 32 , 34 , 36 , 43 , 44 ]. Four of these involved websites or web pages with varying levels of interactivity [ 32 , 34 , 36 , 44 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263339.g004

In Chung and Zhao [ 36 ], undergraduate university students viewed websites advertising cameras, which were classified as either low, medium, or high interactivity based on the number of hyperlinks included. They found a significant association between a higher number of clicks available and higher memory scores [ 36 ].

In Chung and Ahn [ 32 ], authors asked participants to view either a website with a linear structure (scroll to bottom of page and click link to move to next page), an interactive structure (multiple links available on the page), or a mixed linear and interactive structure and asked them to write down all the product information they could recall after exposure [ 32 ]. The authors found that participants who viewed the linear web page exhibited the highest memory score [ 32 ].

In Macias [ 44 ], participants viewed either a low or high interactivity website that advertised one of two consumer products. The high interactivity websites included rollover animation, hyperlinks, comment forms, and chat features. The authors found that participants who viewed the high interactivity website exhibited greater comprehension [ 44 ].

Polster et al. [ 34 ] reported the results of a study comparing interactive and noninteractive versions of a website with important safety information (ISI) about a fictitious medication viewed either on a desktop computer or smartphone. Authors found that a higher percentage of participants allocated to noninteractive websites saw any ISI as measured through objective clicking and scrolling behavior compared with participants who were allocated to the interactive websites ( P < .001). Further, a higher proportion of desktop-using participants allocated to noninteractive websites recalled at least one relevant side effect compared with participants allocated to the interactive websites ( P < .001) [ 34 ]. A higher proportion of participants using a smartphone allocated to noninteractive websites also had higher recall of at least one relevant side effect compared with participants who were allocated to interactive sites, but this finding was only statistically significant for one of the two noninteractive layouts [ 34 ]. Authors also reported the mean percentage correct recognition of medication side effects and conducted additional analyses of recognition limited to those participants who saw any ISI (Table S4-4 in S4 Appendix ).