Principle One

Put patient's interests first, principle two, communicate effectively with patients, principle three, obtain valid consent, principle four, maintain and protect patients' information, principle five, have a clear and effective complaints procedure, principle six, work with colleagues in a way that is in patients' best interests, principle seven, maintain, develop and work within your professional knowledge and skills, principle eight, raise concerns if patients are at risk, principle nine, make sure your personal behaviour maintains patients' confidence in you and the dental profession.

- The 9 Principles

- 1 Put patients' interests first

- 2 Communicate effectively with patients

- 3 Obtain valid consent

- 4 Maintain and protect patients' information

- 5 Have a clear and effective complaints procedure

- 6 Work with colleagues in a way that is in patients' best interests

- 7 Maintain, develop and work within your professional knowledge and skills

- 8 Raise concerns if patients are at risk

- 9 Make sure your personal behaviour maintains patients' confidence in you and the dental profession

Make sure your personal behaviour maintains patients’ confidence in you and the dental profession

Patients expect:.

- That all members of the dental team will maintain appropriate personal and professional behaviour

- That they can trust and have confidence in you as a dental professional

- That they can trust and have confidence in the dental profession

Standards & their guidance

- 9.1.1 You must treat all team members, other colleagues and members of the public fairly, with dignity and in line with the law.

- 9.1.2 You must not make disparaging remarks about another member of the dental team in front of patients. Any concerns you may have about a colleague should be raised through the proper channels.

- 9.1.3 You should not publish anything that could affect patients’ and the public’s confidence in you, or the dental profession, in any public media, unless this is done as part of raising a concern. Public media includes social networking sites, blogs and other social media. In particular, you must not make personal, inaccurate or derogatory comments about patients or colleagues. See our guidance on social networking for more information.

- 9.1.4 You must maintain appropriate boundaries in the relationships you have with patients. You must not take advantage of your position as a dental professional in your relationships with patients.

- 9.2.1 If you know, or suspect, that patients may be at risk because of your health, behaviour or professional performance, you must consult a suitably qualified colleague immediately and follow advice on how to put the interests of patients first.

- 9.2.2 You must not rely on your own assessment of the risk you pose to patients. You should seek occupational health advice or other appropriate advice as soon as possible.

- 9.3.1 You must inform the GDC immediately if you are subject to any criminal proceedings anywhere in the world. See our guidance on reporting criminal proceedings for more information.

- 9.3.2 You must inform the GDC immediately if you are subject to the fitness to practise procedures of another healthcare regulator, either in the United Kingdom or abroad.

- 9.3.3 You must inform the GDC immediately if a finding has been made against your registration by another healthcare regulator, either in the United Kingdom or abroad.

- 9.3.4 You must inform the GDC immediately if you are placed on a barred list held by either the Disclosure and Barring Service or Disclosure Scotland.

- 9.4.1 If you receive a letter from the GDC in connection with concerns about your fitness to practise, you must respond fully within the time specified in the letter. You should also seek advice from your indemnity provider or professional association.

- Commissioners of health;

- other healthcare regulators;

- Hospital Trusts carrying out any investigation;

- the coroner or Procurator Fiscal acting to investigate a death;

- any other regulatory body;

- the Health and Safety Executive; and

- any solicitor, barrister or advocate representing patients or colleagues.

Learning Material & case studies

Case studies for principle 9.

Frequently Asked Questions

Further guidance.

- Social networking dos and don'ts

- Standards for the Dental Team

- Scenario 1 - Drink driving conviction

37 Wimpole Street London W1G 8DQ

www.gdc-uk.org

We want to make sure all of our services are accessible to everyone. Therefore if you would like a copy of these standards in a different format (for example, in large print or audio) or in a language other than English, please contact us.

Personal Development Planning

Working in a dental practice can be exciting, invigorating and rewarding. At the same time it can be very demanding as there is always a lot going on. The dental industry is one of continual learning – things are always changing, especially in medical terms – so it is vital to keep up. A dental nurse’s role has advanced more than ever in recent years, a dental nurse carries out a wide range of tasks. These include looking after patients, patient reassurance, safety precautions, being at the dentist’s side and preparing and sterilising equipment, the list goes on . In addition, of course, all of these tasks must be performed to very high standard. This is why it is so important to take time to reflect on your role, your tasks, your progress and then evaluate how you can develop yourself professionally.

Completing and utilising a Personal Development Plan (PDP) effectively can help support you on your road to progression and what you really want to achieve. It can give you, as an individual, structure, focusing on quality and accountability, which are significant considerations in terms of future goals not only for the individual, but for a dental practice too. A PDP is a method for identifying your developmental needs and devising the best solutions to achieve this development.

A PDP is part of Clinical Governance – the government requires that all NHS clinicians have and use a PDP. A PDP involves updating, revisiting, stimulating ideas, identifying strengths and weaknesses, and prioritising and planning for your future career.

Many people find the idea of reflecting, evaluating and making plans daunting and overwhelming. A word of advice, go through the process slowly and break it down. It will hugely benefit you if you make and stick to an effective PDP.

A PDP in other words is a ‘plan.’ This ‘plan’ demonstrates commitment to your professional development. It can be useful to break down what you need to learn and what you want to learn. This will encourage you to focus on what you want to achieve through this learning and it will force you to think specifically about how you are going to get to that point. You can create your own learning objectives and your PDP will therefore stands as a evidence of your learning and objectives.

A Personal Development Plan demonstrates to the General Dental Council (GDC) that you are committed to lifelong learning in your professional field. It also provides guidance and goals, in addition, assisting with continual professional development (CPD). A PDP has been defined as ‘a process by which we identify our educational needs, set ourselves some objectives in relation to these, undertake our educational activities and produce evidence that you have learned something useful.’ (Rughani, Franklin & Dickson. Personal Development Plans for Dentists. The new approach to continuing professional development. Oxon: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2003, p. 27)

Since August 2008, it was determined by the GDC that Dental Care Professionals (DCPs) have to complete 50 hours of verifiable CPD (in recommended subject areas) and 100 hours non-verifiable in a five-year cycle. Furthermore, it is now law for dental professionals to take part in CPD. The GDC introduced the CPD scheme to ensure patients the best possible treatment. CPD was put in place to ensure patients receive high quality care.

A PDP involves identifying your learning needs, it incorporates CPD activity and aims to improve your professional status. This means you can take control of your own learning and future career. The GDC require that you keep CPD records for five-years and you may be selected for audit. The GDC have declared, ‘As a registered dental professional you have a duty to keep our skills and knowledge up to date so you can give patients the best possible treatment and care. Continuing professional development (CPD) is compulsory, but ideally it should just set out a formal framework for what you are already doing.’ (GDC) A PDP is essential for an individual’s professional portfolio as well as requested by the GDC. A PDP will also be useful for job interviews.

Some practical advice

Before you start your PDP it is a good idea to make a spider diagram including the following topics: Learning and educational needs: how you will address these? Outcomes and Evidence: scribble down ideas and many of your first thoughts which surface when thinking about your career and job role. You can refer back to this. It will be useful as a draft and template.

Whilst drawing on your spider diagram it may be useful to reflect on the following:

• What are you good at? • What could you do better? • What do you think you could change to benefit your practice? • Do any patients make you feel uncomfortable or uneasy? • Has a patient asked you something you don’t know the answer to? • Have you ever needed to look anything up? • What issues have been raised in your appraisals? • Does your practice run effectively? The best it can? • What doesn’t run well in practice? • Have there been any significant events in practice? • What are the practice development priorities? How do they affect you?

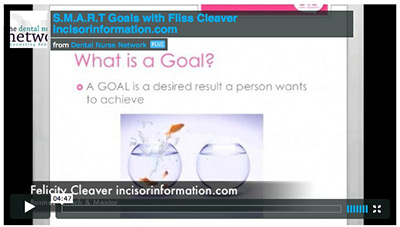

You might prefer to use a ‘Reflective Model’ which helps you to reflect and focus on something specific using the certain subtitles: Description: what happened? Feelings: what did you think or feel? Evaluation: was it good or bad? Analysis: what sense have you made of today? Conclusions: what else could have been done? Action plan: what will you do now? Gibbs (1988) stated that a Reflective Model will ‘help you reflect and focus on your thoughts today'.

The next stage is to begin your PDP. The key is to construct a simple, clear PDP and this can be achieved through a step by step approach.

SWOT analysis - open a word document, google document or pages document ( or DOWNLOAD one here ) and title it ‘SWOT analysis’. SWOT stands for STRENGHS (for example, team leader, update with CPD, good communication skills, good with elderly patients. This is an opportunity to sell yourself), WEAKNESSES (difficultly finding time for CPD or completing CPD, not recording CPD, lack of knowledge in specific areas. Address your weaknesses to help you overcome them), OPPORTUNITIES ( extended duties , supportive boss and colleagues, taking charge of PDP) and THREATS (new job, limited time, overwhelmed with learning new skills, poor communication with team). This gives you a chance to sit down and analyse your current situation. This can help you to work out your long term goals. You may want to do this with a colleague which may help.

The next part is to open a word document ( or DOWNLOAD one here ) and title it SMARTER GOAL 1, you may have more than one so the following pages you would label SMARTER GOAL 2, SMARTER GOAL 3, etc. This is where you can consider your goals, evaluate them, really think about them and make them smarter. You can identify your goals through appraisal, self-awareness, audit and reflection, etc. An occasion may occur when a patient asks you a question and you do not know the answer to it e.g ’ What are implants made of?' This realisation that you are not sure what to respond might highlight that you need to develop your knowledge on implants. Another example of goal may be to complete a certain number of CPD courses. In you PDP you should specifically state which CPD courses you want to undertake. You do not have to write 50 at once, you can build your PDP gradually.

Once you have determined a goal, you then make it smarter by addressing the following questions:

It is important to break your goals down. How will you achieve your goal? What will mark your success? What resources will you need? Set a date to complete the goal Too. You make these decisions and be as flexible as you want working towards what you want to achieve.

The next section of your PDP needs to be a record of your CPD ( DOWNLOAD Record sheet here ) . This includes both verifiable and non-verifiable CPD. This is just a case of compiling certificates, recording dates and sources.

Now you need to decide on how you are going to present you PDP and formulate your PDP portfolio. This can also include: your CV, references, appraisals.

Some practices have undergone annual appraisals and PDPs are involved in the final part of these appraisals. PDPs set out some of your planned, future learning. In this case, your appraiser will likely sign your PDP as satisfactory. Changes or suggestions may be given. The following year's appraisal will involve a review of the previous year's PDP.

The important thing to remember is that you must update your PDP constantly. You can change, alter and modify your goals and then you can add new needs as the year progresses. It is all about self-awareness and figuring out where your strengths and weaknesses lie. It is personal, so it is yours to do and decide what you want to do with. Its main aim is to help with your own development and this further benefits the practice and patients.

Remember Me

- Forgot Login?

Copyright © 2024 Dental Nurse Network. All Rights Reserved.

- News & blogs

- Search the register

Promoting professionalism

Developing our principles of professionalism .

We are currently working with dental professionals and patients to come to a shared understanding of what professionalism means in dentistry today. This work is being done to underpin the development of new principles of professionalism for UK dentistry.

Research has also been undertaken to support the work, Professionalism: a mixed-methods research study , was commissioned by the GDC to provide a comprehensive study of professionalism in healthcare and dentistry.

We have also worked with Community Research to conduct facilitated online sessions with dental professionals and patients to better understand the reasons why views on professionalism in some areas diverge. This work has included sharing stories of professionalism in dentistry and asking you to share with us your examples of professionalism - take a look at the details and get involved.

You can find out more about this work on our research pages and you can watch our recorded online session with the researchers from ADEE where we explored the findings in more detail.

The results were also the subject of a panel discussion at our Moving Upstream Conference 2020 . The expert panel, led by Professor Jonathan Cowpe, ADEE, discussed key points from the research including cultural and generational differences, and the challenges posed by social media.

Video: We asked delegates at our conference to also share their thoughts on what professionalism means to them - have a listen to what they told us.

The results of this work are now being used to inform the development of the principles of professionalism, and our review of the Standards for the dental team and its supporting guidance.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 03 November 2017

Service quality in dentistry: the role of the dental nurse

- M. T. Mindak

BDJ Team volume 4 , Article number: 17177 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

4809 Accesses

1 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health services

- Quality of life

This From the archive article by M. T. Mindak was originally published in the BDJ on 23 November 1996 ( 181 : 363-368). Were dental nurses well motivated and satisfied with their roles 21 years ago? Did dentists’ and dental nurses’ perceptions of the dental nurse's role differ? Was there good communication within dental teams? Read on and see how 1995/6 compares to your experience in 2017.

Patients judge the dental service they receive by the interaction with the service providers - the dentist and his or her staff - as they are unable to judge the technical quality of the service. To perform well as a service provider, employees such as dental nurses have to be well motivated and satisfied with their position. A study of the role of the dental nurse in contributing to service quality in dentistry was carried out through interviews with dentists and nurses at 20 dental practices in the South Thames region in 1995. The results revealed that while dental staff believed that the role of the dental nurse was important in terms of the patient's view of the practice, perceptions of the nurse's role differed. The majority of dentists felt that the nurse's role should be to anticipate their needs, while the nurses’ opinions were evenly divided between putting the needs of the patient first or those of the dentist. Nurses also felt that their role was stressful and reported a lack of praise and recognition of their efforts by dentists. Few practices had written contracts or performance appraisals. The results indicated a lack of effective communication in many dental practices, producing role strain for the nurse and reducing job satisfaction. Increasing job satisfaction reduces staff turnover, resulting in more consistent service quality and reducing associated costs. In order to achieve this, several recommendations are made with the aim of improving communication between staff in dental practices.

The actions of health care representatives play a critical role in the public perception of any health care service. The provision of dental treatment provides a good example of this as a patient cannot judge the technical aspects of dentistry and so will judge the quality of the service provided by the quality of the interaction with the service providers - the dentist and his or her staff.

The dental nurse is an essential member of the dental team. The dentist and dental nurse need to have a clear understanding of their working relationship and the factors that affect it, in order to be effective in the process of service delivery. The importance of an effective interaction between dentist and dental nurse is further highlighted by the fact that there is a possibility, albeit rare, of that interaction working to save the life of a patient who has been taken ill during treatment.

The real benefit, however, in developing an improved working relationship between dentist and nurse, is in creating a more harmonious working environment. This, in turn, produces a more pleasant, friendly atmosphere for the patient, who perceives an improvement in the quality of service. As a result, the patient is more likely to stay with the practice and recommend it to friends and family.

There is a high turnover of dental staff. 1 This causes problems in delivering consistent service quality due to the disruption of routine for the dentist and loss of relationship continuity for patients when a staff member leaves. There is also the expense and time required to recruit and train a new member of staff. It is useful, therefore, to know what factors affect this turnover in order to try to reduce it. The aim of this study was to examine aspects of the role of the nurse in order to provide recommendations for reducing staff turnover and improving service quality in dental practices.

Materials and methods

A study was conducted by means of a series of qualitative interviews with dentists and nurses at 22 practices selected from the South Thames Health Authority region. Qualitative research was deemed to be the most appropriate method as the study was to be exploratory in nature, to ascertain general themes, which required a more flexible approach than would be possible by a standardised structured questionnaire.

It was decided to select 11 NHS practices and 11 private practices for the purposes of the study. The practices were chosen from three FHSAs from within the South Thames Health Authority region: Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham FHSA, Bromley FHSA and Bexley and Greenwich FHSA. One hundred dental practices were initially selected, 50 practices from the NHS and 50 private practices.

Each practice was contacted by letter detailing the nature of the research. They were each then telephoned and asked if they wished to participate. Many practices did not wish to participate or else stated that the dates during which the study was being held (June to August 1995) were not convenient. The final sample of 22 practices (11 NHS and 11 private) was therefore, in part, self-selected.

The only selection criteria applied by the author were those of the practice being in one of the three FHSA areas, that the practice agreed to participate and that the interviewees consisted of one dentist and his or her own dental nurse and not a nurse who routinely worked with a colleague.

Pilot interviews were carried out at two additional dental practices in the London area to clarify the nature of the questions to be asked in the main study interviews. The main study interviews were conducted at the dental practices during July and August 1995. The vast majority took place during the practice lunch break and consisted of individual semi-structured interviews of approximately 20 to 30 minutes.

The interviewer first asked general closed questions regarding qualifications, hours worked and so on and then asked open-ended questions regarding the role of the dental nurse. Two sets of questions were used for the interview frameworks - one for the dentists and one for the dental nurses, but both followed the pattern of closed followed by open-ended questions. The interviews were conducted face-to-face with the author who travelled to each practice.

The dentist and his or her nurse were interviewed separately and encouraged to speak freely, being assured that the other members of the practice would not be informed of any comments made. All interviews were tape-recorded with individuals being informed of this prior to the interview and consent obtained. The taped interviews were then transcribed for analysis. Recurring themes and topics were then grouped together to produce the results.

Quantitative results

One dentist and his or her dental nurse were interviewed at each practice, a total of 40 individual interviews out of a possible 44. The results from two practices, ie four interviews, were deemed unsuitable for inclusion in the study. The reasons for this were that for one practice there was a mechanical fault with the tape recorder resulting in only half the interview being recorded, and in the other practice, the dentist concerned declined to continue with the interview and did not wish to answer the questions. This left a final sample of 20 practices - 10 NHS and 10 private.

Characteristics of the sample: dentists

AGE AND GENDER

The age range of dentists was from 27 to 58 years, with the majority between 30 and 40 years old. Four of the 20 dentists were female.

DATE OF DENTAL QUALIFICATION

The date of the dental qualification was naturally correlated with age and ranged from 1963 to 1991. Ten of the UK's 16 dental schools were represented, from all parts of the country. Two respondents had trained abroad - Nigeria and India.

TIME AT CURRENT PRACTICE

Time at current practice ranged from 11 months to 32 years, with 12 respondents being at the practice for more than two years. The majority of respondents were the practice owner and would therefore be expected to remain at the practice.

NUMBER OF STAFF AT THE PRACTICE

The number of staff was calculated to include part time staff as well as full time. The range was from two, where the nurse was also the full time receptionist (three practices), to one practice of 24 staff. The majority had four to six staff.

NUMBER OF PATIENTS SEEN PER DENTIST PER DAY

For NHS practices, this ranged from 18 patients (in two newly established practices) to around 40. The vast majority were in the range 25-30. In private practices the figures were rather lower; the range was 10-25, with most being around 15.

Characteristics of the sample: nurses

The range was from 16 to 57 years old. Two were over 50, three in their 40s and the remainder 39 or under. Two were teenagers. The average age of nurses in private practice was around nine years older (35 years) than that for NHS practices (26 years).

LENGTH OF TIME WORKED AS A DENTAL NURSE

This varied from eight months to, in one case, 39 years (the nurse having left school at 14). The sample was fairly evenly split between those who had worked as a nurse for 10 years or less and those who had worked as a nurse for more than 10 years.

For NHS practices, this ranged from two days to six years. Seven out of 10 nurses had been at the practice for two years or less. In private practice, the range was from 10 months to 15 years. Five nurses had been at the practice for two years or less and the other five for two years or more.

DENTAL NURSING CERTIFICATE

Six out of 20 nurses had a qualification, five in private practice and one in the NHS. Two further nurses in the NHS had taken the exam and failed, but did not intend to retake it. Two nurses in private practices were currently on the training course.

Qualitative results

All those involved in the study agreed that the role of the dental nurse was very important in terms of how the patient viewed the practice. The nurse was seen to be the patients’ confidante and provided reassurance:

‘It's always you they will ask’ (nurse aged 25, private practice)

‘If they’ve got a problem, I talk to them because at times they don’t want to talk to the dentist, so they talk to me and I can pass the message on to the dentist’ (nurse aged 30, NHS practice)

The study also produced other findings that can be grouped into three areas:

A difference in perceptions of the role of the dental nurse between nurses and dentists.

The lack of appreciation and acknowledgement of nurses’ efforts by dentists, as felt by nurses.

The lack of formalisation of the nurse's role in terms of written contracts or performance appraisal and the lack of regular staff meetings.

The difference in perceptions of the nurse's role

THE DENTISTS’ VIEW

The vast majority of the dentists (18 of 20) viewed the role of the dental nurse principally to be anticipating the dentist's needs: having instruments ready, the surgery clean and so on. They wanted the nurse to be able to think ahead for them:

‘You get to a stage where she's got it ready before you say anything and then when you get one stage further, you can ask for the wrong things and get the right things’ (male dentist aged 47, private practice)

Dentists felt that reliability was very important in fulfilling the nurse's role:

‘I’ve had situations where after being her for three or four months a nurse has taken her pay cheque on the Friday and then not come in on the Monday, without telling me that they’re not coming back’ (dentist aged 31, NHS practice)

Many of the dentists, 12 of 20, expressed a preference for older nurses rather than teenagers, and for those who had gained previous experience, saying that they found younger staff to be far less reliable in terms of timekeeping and attendance:

‘If I had a choice of someone to employ, I would happily go for someone in their late 20s onwards with children. We’ve found that with younger women, their attendance can be distinctly “iffy” and the merest sniffle, they’re off’ (dentist aged 39, private practice)

Dentists also felt that an empathetic and cheerful personality was important, not just for patients’ sake, but also for their own morale. All dentists said that an efficient and friendly nurse acted to greatly reduce the day to day stress of practice:

‘If you’ve got a very close relationship with that person (the dental nurse) for eight hours a day and if they’re not happy it can drain on you and affect the relationship with the patient’ (female dentist aged 30, NHS practice)

‘My stress level goes up enormously if she isn’t working with me ... she makes life a lot easier without a doubt’ (male dentist aged 35, private practice)

THE NURSES’ VIEW OF THEIR ROLE

In contrast to the dentists, dental nurses were divided as to their principal role: 10 nurses clearly stated that the patient was their first priority, while the other 10 said that the dentist's needs come first.

‘My role is actually thinking for the dentist’ (nurse aged 30, NHS practice)

‘I think for him, I’m one step ahead’ (nurse aged 31 private practice)

‘To help the patient feel as relaxed as possible’ (nurse aged 18, NHS practice)

‘Primarily, to make sure the patients feel comfortable and welcome’ (nurse aged 43, private practice)

Nurses also said that they saw a major part of their role to be acting as an intermediary between dentists and patients and that this could be very stressful. They said that patients saw them as representing the practice and would want explanations as to why an appointment was late, for example, while the dentists would be telling them to go out and keep the patient calm:

‘They (patients) quite often treat the nurse very differently to the dentist ... the patients have a real moan and then go into the surgery and be as nice as pie and you think “oooh”!’ (nurse aged 22, private practice)

The lack of appreciation

Many nurses, 11 of 20, reported problems in communicating with dentists. Areas of concern were principally the lack of definition of the nurses’ role by dentists and lack of appreciation by dentists for the nurses’ efforts. Nurses reported being given little instruction when joining a practice and were often expected to know what to do in the surgery:

‘He just expected everything there without telling you or asking you. Me sitting there not doing it because I don’t know what he needs and him probably thinking, “Oh she's just sitting there”, but it's not, it's because he's not actually explained what he needs and therefore I can’t mix it when I don’t know’ (nurse aged 24, NHS practice, describing life as a trainee at 17)

Most nurses, 14 of 20, reported being spoken to in a derogatory manner, which they felt indicated a lack of respect. This got worse when the dentist was under stress. Many understood that dentistry was stressful and wanted to help the dentist, but still wished to be spoken to courteously.

‘He was very rude, he used to swear at you and abuse you if you did things wrong’ (nurse aged 31, private practice)

‘I was a trainee and he was just very impatient and used to be sarcastic in front of patients and I didn’t like that because it made me look stupid’ (nurse aged 22, private practice)

Some dentists apparently coped with stress in unusual ways:

‘There was one guy, if he didn’t like things or things didn’t go his way or he couldn’t get a matrix band on, he’d throw tweezers at your ankles ... It wasn’t anything to do with the nurses, it was just his own pure frustration, but he was quite well known for it’ (nurse aged 43, private practice)

Dental nurses wanted their efforts recognised and acknowledged by the dentist and felt that this rarely occurred. When this did happen, it was much appreciated and was felt to contribute to a more pleasant atmosphere in the practice, which, nurses said, was noticed by the patients:

‘If the dentist appreciates what the nurse is doing, then the nurse gives her best to the dental surgeon. You’ve got to work as a team ... if you work as a team and you can be friends then the patient gets so much more out of that because the atmosphere is so different. I think a patient can feel an atmosphere when they go into a surgery. If they feel a good atmosphere, then they get good vibrations and they relax more’ (nurse aged 44, NHS practice)

A nurse with 24 years’ experience said of her employer, a dentist aged 39, in private practice:

‘I think really a dentist should include their nurse in the work or they can make them feel just like the washer-upper and I feel very included here ... he's terrific, absolutely terrific. This dentist will at the end of the day say “thank you”. That's not usual, normally they’re tools down and gone and leave you to clear up’.

Some dentists said they found managing staff difficult, especially in the first years of practice. Three of the four female dentists felt that the task was harder as a woman than for a man. Their nurses felt that female dentists were more sensitive in dealing with staff and would help the nurse more than a male dentist would.

RESPONSIBILITY AND EXPANSION OF THE ROLE OF THE DENTAL NURSE

At present, the role of the dental nurse is limited in terms of direct clinical interaction with the patient, in contrast to other countries such as the USA and New Zealand. Dentists and nurses were asked their views on the possible expansion of the nurse's role, as considered in the Nuffield Report. 2

Most dentists, 11 of 17 (three did not respond), were not in favour of the dental nurse taking on any clinical duties, apart from taking radiographs. Many did not see any real benefit of the nurse undertaking these tasks and expressed concern about the level of training for nurses that would be necessary to ensure patient safety. The majority of nurses however, expressed a desire to expand their role and mentioned the lack of a career path. Several nurses mentioned that being given responsibility made their job more enjoyable:

‘Having the responsibility brings our your best qualities because everybody's got a forte at something’ (nurse aged 31, private practice)

Six of the 20 had a dental nursing qualification, and five of these were in private practice. Many expressed a desire to expand their role with the patient and said they felt frustrated at not being able to do more in the surgery. Five of the 20 interviewed had made a definite decision to obtain further qualifications towards that end and had registered to train as a hygienist (1), dental therapist (2) oral health educator (1) and general medical nurse (1).

Four of the 20 nurses brought up the subject of their salary. They felt it was far too low for the job and felt unappreciated as a result. One nurse said:

‘You are risking yourself as much as dentists, with AIDS and all that, and their pay is good ... that makes me sick ... they sort themselves out and forget the nurses’ (nurse aged 24, NHS practice)

Some dentists seemed to be unaware of just how sensitive an issue this was. Nurses in private practice, not surprisingly, reported being paid more than in NHS practices and had left NHS practices as a result. Some private dentists said that they felt higher salaries to be a worthwhile investment to attract good staff.

The lack of a formalised role

WRITTEN CONTRACTS AND STAFF APPRAISAL

Only five practices in the survey had a written contract for staff and only one carried out a formal staff appraisal. Nurses said that they would welcome a regular appraisal of their performance, as some had just occasional comments made to them. Several complained of being readily criticised if they made a mistake, yet never praised when they performed well.

PRACTICE MEETINGS

Similarly, only five practices held practice meetings on a regular basis, while a few more held them on an occasional basis. The practices that did currently hold meetings found them to be valuable aids to communication and staff participation. Some nurses however, felt that little was achieved by meetings: they had attended them in the past and said that little attention was paid to their opinions or suggestions. In a lot of practices, both dentists and nurses did not see any need for meetings at all.

The results of the study should be interpreted with caution as this was a small and self-selecting sample. Nonetheless, several of the findings are relevant to dental practice management. It was evident from the study that there are problems in communication between the dentist and the dental nurse in many dental practices. These problems were manifested in the different perceptions as to what the role for the nurse actually entailed, in the way the required role was explained, the lack of written job descriptions, coupled with little positive feedback or appraisal, and a derogatory manner used in addressing the nurse. In addition, very few practices provided an opportunity for the nurse to raise problems, make suggestions or participate in decision making, by means of mechanisms such as a regular practice meeting. The lack of management skills training for dentists may well be a contributory factor here. These findings confirm previous research that has been carried out into job related for the dental nurse.

The consequences of poor communication

A lack of communication between and employer and employee results in several negative outcomes which researchers have found affect job satisfaction. 6 , 7 Two principal ones are role ambiguity and role conflict. Role ambiguity occurs where a role has not been clearly defined and responsibilities are ambiguous, as was clearly felt by the nurses in the study. Role conflict occurs when the employee is expected to carry out contradictory tasks, such as trying to please both patient and dentist. The stress nurses mentioned at being the ‘intermediary’ is well recognised in the literature, this position being described as the ‘boundary-spanning’ role ie the boundary between the organisation and the customer. Such roles have been associated with high degrees of stress for employees. 7

These factors result in role strain, which has been shown to decrease job satisfaction. Dentists stated that the main problems they had with dental nurses were poor timekeeping and absenteeism. Both these behaviours have been shown to be symptomatic of reduced job satisfaction.

Staff turnover

A reduction in job satisfaction is directly related to the employee's tendency to leave the organisation. 9 It is known that dental nurses have a high employment turnover, with the resultant increased costs and inconsistency of service quality for the dental practice as previously mentioned. Turnover of staff adversely affects the consumer's perception of the service, with the result that they will go elsewhere. So in order to provide and maintain service quality in the eyes of the consumer (the patient) staff turnover is to be avoided.

The results of this study show that a lack of communication between dentist and nurse could well be contributing to the high turnover rate. In order to reduce turnover of dental nurses and increase job satisfaction, positive steps should be taken to improve communication.

Recommendations

The process of good communication involves the processes of active listening - concentrating on exactly what a person is saying, not jumping to conclusions or assumptions; feedback on how the role was performed helps to clarify discussion and self-disclosure - an atmosphere of trust and openness should be established so that staff feel able to make comments and suggestions. 10

Many of the suggestions made below are not new. 11 - 16 However, this survey shows that they are still relevant and that improving communication is still necessary for many dental practices. Several of these improvements can be made immediately and the majority can be implemented at little or no financial cost.

Immediate changes in the dental practice

To make changes towards improving communication in the dental practice work, it is best to start with small and simple things that are easy to implement and are likely to succeed. Early success will encourage staff and reinforce the new approach.

ACHIEVING BETTER COMMUNICATION

Praise and recognition are powerful ‘motivators’. These are therefore ideal areas with which to start ( Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , and 5 ).

THE PRACTICE MEETING

Efforts to improve communication in the practice should involve all the staff, not just the nurse, and the suggestions below are relevant for all staff. In addition, practice meetings are a valuable tool.

Changes in the medium term

The initial approaches will start to improve communication in the practice and can be reinforced over the following few months by further measures - further clarify roles by written descriptions, build in praise and recognition and build up an atmosphere of trust by training and delegation.

Long term changes - recommendations for the profession

As we can see, these are relatively simply changes that can be carried out in a short period of time. However, for the profession as a whole, there remains the issue of training for both dentists and nurses which needs to take into account communication and interpersonal skills, which, as the study showed, are so necessary. In addition, the recommendations in the Nuffield Report 2 regarding the training of dental nurses, ie the introduction of a national training standard and statutory minimum qualification, should be implemented as soon as possible. A better career structure for dental nurses will act to retain and motivate staff, raise standards of care, improve service quality and thereby the patients’ view of the practice.

Bader J . Auxiliary turnover in 13 dental offices. J Am Dent Assoc 1982; 104 307–312.

Article Google Scholar

Nuffield Report. Education and training of personnel auxiliary to dentistry . Norwich, UK: The Nuffield Foundation 1993.

Locker D, Burman D, Otchere D . Work-related stress and its predictors among Canadian dental assistants. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1989; 17 263–266.

Blinkhorn A . Stress and the dental team: a qualitative investigation of the causes of stress in general dental practice. Dent Update 1992; 19 385–387.

PubMed Google Scholar

Craven R C, Blinkhorn A S, Roberts C . A survey of job stress and job satisfaction among DSAs in the north-west of England. Br Dent J 1995; 178 101–104.

Jackson S E, Schuler R S . A meta-analysis and conceptual critique of research on role ambiguity and role conflict in work settings. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes 1985; 36 16–49.

Netemeyer R, Burton S, Johnston M . A nested comparison of four models of the consequences of role perception variables. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes 1995; 61 77–93.

Shamir B . Between service and servility. Human Relations 1984; 33 : 741–756.

Bedian A, Armenakis A . A path analytic study of the consequences of role conflict and ambiguity. Academy of Management J 1981; 24 417–424.

Google Scholar

Hellriegal D, Slocum J Jr, Woodman R W . Organizational behaviour . 6th ed. St Paul, MN: West, 1992.

Cummings T G, Worley C G . Organizational development and change . St Paul, MN: West, 1993.

Schwartz S . Motivating the dental staff. Dent Clin North Am 1988; 32 35–45.

McKenzie S . Empowering your dental team. J Michigan Dent Assoc 1992; 74 36–38.

Manji I . Fair pay and then some: how to retain your staff. J Can Dent Assoc 1992; 58 : 895–896.

Butters J, Willis D . Satisfaction level of dental office personnel. Gen Dent 1993; May-June: 236–240.

Nacht E S . 13 ways to keep the staff motivated in your pediatric dental office. J Clin Pediatr Dent 1994; 18 163–164.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mindak, M. Service quality in dentistry: the role of the dental nurse . BDJ Team 4 , 17177 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/bdjteam.2017.177

Download citation

Published : 03 November 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/bdjteam.2017.177

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Creating a new NHS England: Health Education England, NHS Digital and NHS England have merged. Learn more.

- Privacy and Cookies Policy

Reflection and Personal Development Plans

Home / About Us / Education and Training / Development Plans / Reflection and Personal Development Plans

The use of reflection has become a routine part of many professions such as teaching and nursing. In dentistry we have been slower to adopt it as way of highlighting development needs.

You might think, how can reflection help me, either to learn things or highlight an area that I need to develop further. How can reflection help to develop my own personal development plan?

There is evidence that engaging in Reflective Practice is associated with the improvement of the quality of care, stimulating personal and professional growth and closing the gap between theory and practice. There is a lot of literature on Reflective Practice. Davies (2012) has summarised a lot this and identifies that there are both benefits as well as limitations to reflective practice:

Benefits to Reflective Practice

- Increased learning from an experience or situation

- Promotion of deep learning

- Identification of personal and professional strengths and areas for improvement

- Identification of educational needs

- Acquisition of new knowledge and skills

- Further understanding of own beliefs, attitudes and values

- Encouragement of self-motivation and self-directed learning

- Could act as a source of feedback

- Possible improvements of personal and clinical confidence

Limitations of Reflective Practice

- Not all practitioners may understand the reflective process

- May feel uncomfortable challenging and evaluating own practice

- Could be time consuming

- May have confusion as to which situations/experiences to reflect upon

- May not be adequate to resolve clinical problems [this would point to a further learning need.]

Reflection is something we do every day we just don’t notice that were doing it much of the time. A lot has been written about reflection, but it can be best illustrated by an example:

You start a new job and have a new journey to work. Before your first day you think about the journey to work, which route to work will be best and how long will it take. This indicates what time you need to set off to arrive, at the time you want. As you have not done the journey before you may drive it before hand or allow extra time so you can allow for delays. This then becomes your daily commute. However on this drive there is a roundabout that always holds you up. One day you try a slightly different route and it works, you avoid the holdup and save five minutes on your journey Time. You have tried a new route and it worked, you have learnt something from trying something new. Another day there is a bad accident and your normal route is blocked so you have to take another one to try to get round it. You are forced to react to the situation.

These are examples of reflection and how it could help in professional practice. You try something out to overcome a problem you have and see if your idea improves the situation or not. Most of the time, we do this in our minds. In more ‘formal’ reflection, we take that a stage further and write in down. This separation helps us to consider what we are doing and consider our thought processes. It also means we can demonstrate this to others. [It will be part of revalidation with the GDC, when it comes.]

If we look at a Dental example: you have a number of new patients that have advanced periodontal disease, you would normally do quadrant scaling for these patients {which you were taught at Dental school}, some seem to be helped and others don’t seem to respond. In this situation you could carry on doing the same thing or start to reflect ‘I’m not sure this is the best way to treat them’. This might prompt you to go on a Periodontal update course and see if what you were taught at Dental school is still the current treatment being taught. It highlights a possible learning need.

In practice if we take the time to reflect on things that happens it can help us to identify areas we need to improve in our own practice. If you like Endodontics and get good results then it should not be a priority for your personal development plan. The temptation is to go on another endodontic course as you enjoy it. It may to the case that a Periodontal course would be more useful. This thought process can be developed by reflection. You are able to consider the areas of dentistry that you are comfortable with and get good results against those areas that you feel you could improve or feel you don’t have all the understanding to do well.

Lots of different ways of reflecting have been described, none of which is necessarily better or the correct way to do it. One way that is widely used is Gibbs reflection cycle [1988]

This page was last updated June 18th 2015 (9 years ago)

Pocket Dentistry

Fastest clinical dentistry insight engine.

- Dental Hygiene

- Dental Materials

- Dental Nursing and Assisting

- Dental Technology

- Endodontics

- Esthetic Dentristry

- General Dentistry

- Implantology

- Operative Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology

- Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Orthodontics

- Pedodontics

- Periodontics

- Prosthodontics

- Gold Member

- Terms and Condition

4 Health and Safety in the Dental Workplace

Health and safety in the dental workplace.

- health and safety requirements relevant to both employers and employees

- the legislative and regulatory requirements of the dental workplace and its staff

- risk assessment in the dental workplace

- occupational hazards and their avoidance in the dental workplace

- the actions to take in various first aid scenarios

- general safety and security issues in the dental workplace

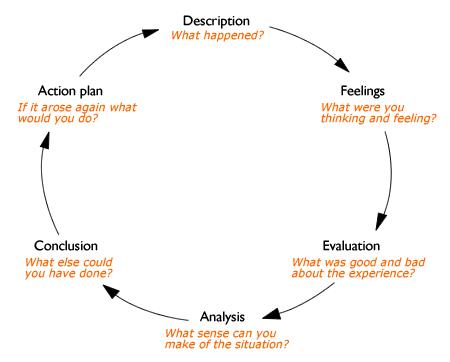

Health and Safety at Work Act (1974)

All dental workplaces, their staff and patients are covered by the provisions of the Health and Safety at Work Act (1974), as is any other workplace. In addition, other legislation is relevant to the dental workplace due to the potentially harmful nature of the equipment and chemicals used, as well as the occupational hazards associated with delivering dental treatment or working in the dental environment.

The Health and Safety legislation seeks to protect staff and patients while on the premises by making the staff aware of any potential hazards at work, and encouraging them to find the best ways of making their premises safer for all concerned. In legal terms, the employer has a statutory duty to ensure that, as far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of all employees and all visitors (including patients) are considered at all times. To do this, all the potential hazards first need to be identified, and then the likelihood of them actually causing harm to anyone must be determined. The chance that a particular workplace hazard could cause harm to someone is known as its risk, and the correct procedure to be followed by the employer (and their staff) to identify those hazards that could cause harm is called a risk assessment.

Compliance with the Health and Safety at Work Act is overseen and regulated by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). This is a government body that provides guidance to employers on the correct enforcement of the Act, and investigates when any serious incidents occur in any workplace where someone suffers serious harm or is killed. Every dental workplace is required to be registered with the HSE.

Compliance with the additional legislation specific to the dental workplace is also required by the General Dental Council, under its Standards for Dental Professionals documentation.

To comply with the basic requirements of the Health and Safety at Work Act, every employer in the dental workplace must abide by the following requirements.

- Provide a working environment for employees that is safe, without risks to health, and adequate with regard to facilities and arrangements for their welfare at work.

- Maintain the place of work, including the means of access and exit, in a safe condition.

- Provide and maintain safe equipment, appliances and systems of work.

- Ensure all staff are trained in the safe handling and storage of any dangerous or potentially harmful items or substances.

- Provide such instruction, training and supervision as is necessary to ensure health and safety.

- Review the Health and Safety performance of all staff annually, be aware of and investigate any failures or concerns highlighted, when they occur.

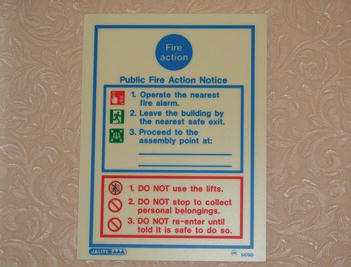

- Display the official Health and Safety poster for all staff to refer to ( Figure 4.1 ).

To comply with these statutory obligations, dentists must keep their staff informed of all the safety measures adopted. Practices with five or more employees must produce a comprehensive Health and Safety policy and provide all staff with a copy. The policy will classify the practice Health and Safety procedures and name the persons responsible. It should also list the telephone numbers of all dental, administration and equipment maintenance contractors, the local HSE contact, and emergency services.

Role of the dental nurse

All dental nurses have a legal obligation to co-operate with their employers in carrying out the practice requirements in respect of these safety measures. They are designed to protect not only the staff and patients, but anybody else using or visiting the premises. In a large dental workplace, a dental nurse may be appointed as safety representative under the Act for the purpose of improving liaison within the practice about Health and Safety matters.

However, many dental nurses begin their careers as young trainees in the dental environment, so the following two sets of regulations are specifically important in protecting their welfare.

- Health and Safety (Young Persons) Regulations 1997

- Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999

Figure 4.1 Health and Safety poster.© Crown Copyright 2009. Published by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE).

These sets of regulations dictate that a risk assessment of the dental environment has to be carried out, with particular regard to the protection of younger staff members, by taking into account the following points.

- The risks to young people before they start work.

- The psychological or physical immaturity and inexperience of young people.

- Their lack of awareness of existing or potential risks to their health and safety.

- The fitting and layout of the practice and surgery, with regard to the safety of young people.

- The nature, degree and duration of any exposure to biological, chemical or physical agents within the work environment.

- The form, range, use and handling of dental equipment.

- The way in which processes and activities are organized.

- Any Health and Safety training given, or intended to be given.

A summary of the risk assessment details, covering the various types of work activity that a student dental nurse is likely to undertake, to ensure their safety in the dental workplace is shown in Table 4.1 . The risk assessment should take into account the likely activities that the student dental nurse will undertake while on the premises, and these are listed in the first column. To train effectively, they must always be involved in chairside assisting activities, so the potential areas of risk to the student during chairside working should then be considered – these are listed in the second column. The final column then needs to identify the methods required to ensure that the student is not exposed to these risks in the first place, and for each area it can be seen that suitable induction training is always required. This involves explaining why a certain activity is a risk to them, the provision of suitable training in the activity so that the risk is minimised as far as possible, and initial supervision when the activity is carried out for the first few times. Before dental nurses became registrants with the General Dental Council (GDC), and therefore before training and qualification were necessary, this supervision used to be referred to as ‘shadowing’ of a junior colleague by a senior colleague, until they were deemed able to carry out the activity unsupervised. The risk assessment procedure described here merely formalises the technique of shadowing.

Table 4.1 Risk assessment for student dental nurse

Full compliance with Health and Safety legislation for all dental workplaces, whether a practice, a clinic or a hospital department, involves all of the following.

- Fire Precaution (Workplace) Regulations (1999)

- Health and Safety (First Aid) Regulations (1981)

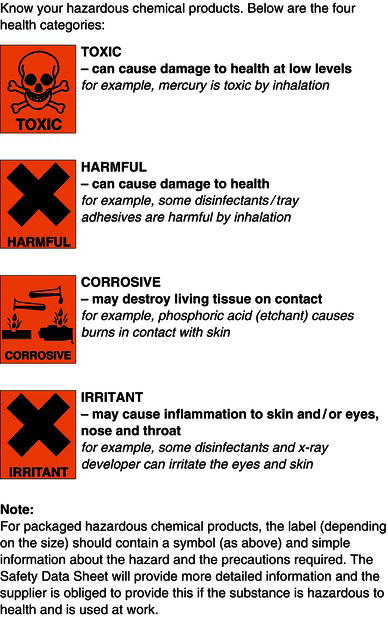

- Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSSH) (1994)

- Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences (RIDDOR) (1995)

- Environmental Protection Act (1990)

- Special Waste and Hazardous Waste Regulations (2005)

- Ionising Radiation Regulations (IRR) 1999

- Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations (IR(ME)R) 2000

- Occupational hazards

- General safety measures

- General security measures

Since 2010, additional regulations have been introduced in the specific areas of decontamination and infection control in the dental workplace, although their implementation currently varies throughout the UK. Referred to collectively as HTM 01-05, their detail is discussed in Chapter 8. Finally, since 2011 a system of mandatory registration with the Care Quality Commission (CQC) has been introduced for all providers of health and social care, including all dental workplaces. The CQC is a regulatory body which ensures that all registrants comply with essential standards of quality and safety when dealing with patients. The impact of CQC registration on the dental workplace, and its relevance to dental nurses, is discussed more fully in Chapter 3.

Risk assessment

As stated above, the whole purpose of the Health and Safety legislation is to protect everyone within the dental workplace (staff, patients and visitors) from coming to any harm while on the premises. This is achieved by carrying out a risk assessment of every potential hazard that could occur. The aim is not necessarily to eliminate every risk completely (this is likely to be impossible in most workplaces, including dental surgeries) but instead to minimise those risks identified as far as possible, so that there is little chance of them causing harm to anyone.

For example, various chemicals must be used in the dental workplace to carry out dental treatment successfully – these include decontamination solutions, x-ray processing solutions, and mercury in amalgam fillings; all are potentially harmful but only if mishandled. So knowledge of their correct storage and usage by staff, and protection from misuse by all others, are key factors in avoiding a hazardous event.

The steps involved in carrying out a risk assessment on a hazard, whatever its nature, should always follow the same pattern.

Although specialist knowledge of some hazards in the dental workplace is necessary to fully realise their potential for causing harm, many of the actions that should be followed to ensure the health and safety of everyone on the premises are common sense.

Table 4.2 Avoidance of hazards

Consider the scenarios and relevant common-sense actions in Table 4.2 . The table gives examples of various hazardous situations that may be encountered by patients and visitors to the dental workplace in the first column, in a similar way to those that may be encountered by the student dental nurse shown in Table 4.1 . The second column then suggests common-sense actions to take that will minimise the potential risk in the first place. So, for example, there are several potentially harmful chemicals used in dentistry that cannot be avoided, such as bleach-based cleaning agents. When used for their specific purpose, there is no risk but if used contrary to that purpose (such as being swallowed by a child), their potential to cause harm is huge. The common-sense action is to prevent the child from having access to the chemical at all times, by locking it away in a cupboard or storing it in a locked room away from the public access areas of the workplace. The differing design and layout of each workplace will require that an individual risk assessment is carried out for each one.

These scenarios are not exclusive to the dental workplace – they could occur anywhere at any time and to anyone. However, if they do occur in the dental workplace then they are not merely an unavoidable accident but have become an avoidable risk that should have been prevented from happening. In other words, someone is to blame. If the simple common-sense actions have not been carried out initially, then the employer is to blame. If, however, a risk assessment has resulted in the necessary preventive measures being put into place and someone has flouted them, such as by leaving a door or cupboard unlocked to avoid the inconvenience of having to keep unlocking it, then that person is to blame instead.

All members of staff have a legal obligation under the Health and Safety at Work Act to co-operate with their employer by following the policies and procedures put in place to protect all persons while on the premises. They must also take reasonable care for their own and others’ health and safety while on the premises. Failure to do so, as indicated above, will result in their possible investigation and prosecution by the HSE, and a fitness to practise hearing by the GDC, for those who are registrants.

The level of reasonable care expected to be taken for their own health and safety as an employee (and in line with ‘fitness to practise’ requirements by the GDC) requires all dental care professionals to abide by the following when in the dental workplace.

- Undergo suitable training in the use of dental materials and equipment.

- Always follow that training when using those materials and equipment.

- Always follow all policies in relation to health, safety and welfare issues.

- Never misuse any materials or equipment on the premises.

- In particular, never misuse or fail to use any materials or equipment that are specifically meant to reduce or eliminate hazardous risks.

- Always report any faults in procedures or equipment to a senior colleague immediately.

- Never enter certain designated ‘hazardous’ areas unless authorised to do so.

- Always report any suspected health problem that will affect their normal work to a senior colleague as soon as possible.

It is important, then, that a FULL risk assessment of the dental workplace is carried out and its findings reviewed on a regular basis, and that all staff follow the control measures that have been put into place, at all times. Advice and guidance are available on risk assessment generally, and in the dental workplace in particular, from both the HSE and from organisations such as the British Dental Association. Their website addresses for further information are:

- Health and Safety Executive: www.hse.gov.uk

- British Dental Association: www.bda.org .

Fire Precaution (Workplace) Regulations 1999

The above regulations were updated by the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order, which became law in 2006. This stipulates that the employer/owner of the premises (the dental workplace) must take reasonable steps to reduce the risk from fire, and to make sure that people on the premises can escape safely if there is a fire. They therefore require the employer/owner to risk assess the fire precautions that are needed for their own work premises, as these will vary from one workplace to another; a ground floor practice will be considered less dangerous to staff and patients in the event of a fire than one that is in a multistorey building, for instance.

A typical fire risk assessment should consider the following points, and in this order.

All dental workplaces then undergo a fire safety inspection, so that the premises can be formally recorded as having carried out the necessary risk assessment. Although several companies provide the means for this to be carried out by post, a visit by a suitably qualified inspector from the Fire Brigade will hold more weight if a fire does occur and the practice is held to account for its level of compliance.

The inspection will give advice with regard to the following.

- The number and positioning of smoke detectors.

- The number and positioning of fire extinguishers.

- Written records of staff training in the use of fire extinguishers.

- The types of fire extinguishers to be provided, with at least two types present in all workplaces.

Fire detection

The Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005 states that an electrical fire alarm system and/or an automatic detection system are only necessary on premises where these devices would be necessary to give warning in case of fire. The types of premises involved would be large workplaces, perhaps over several levels, where a fire breaking out in one area could go undetected by an ordinary smoke alarm or unnoticed by a person for some time. Hospital departments and health clinics are examples of places where these additional fire detection methods would be required.

In smaller workplaces (the majority of dental practices), a fire risk assessment should determine that adequate fire detection is provided by battery-operated smoke alarms around the premises ( Figure 4.2 ). The local fire station, or the fire inspector, will give advice on the number required and their suitable locations at key points throughout the premises. They should be tested on a regular basis to ensure they are functioning correctly, and a record kept of these test dates and results. Obviously, the battery should be changed as soon as it begins to fail, or the alarm changed if any malfunctions occur.

Figure 4.2 Smoke alarm.

Fire fighting

The main equipment available for use in fire fighting is the fire extinguisher ( Figure 4.3 ), although some premises will have additional equipment such as fire blankets and hoses. To determine which fire-fighting equipment should be available, the classification of fires is considered as follows.

- Class A fire – caused by the ignition of carbon-containing items such as paper, wood and textiles.

- Class B fire – caused by flammable liquids such as oils, solvents and petrol.

- Class C fire – caused by flammable gases such as domestic gas, butane, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG).

- Class D fire – caused by reactive metals that oxidise in air such as sodium and magnesium.

- Class E fire – caused by electrical components and equipment.

- Class F fire – caused by liquid fats such as used in kitchens and restaurants.

In the dental workplace, the likeliest causes of fire shown above suggest that extinguishers to fight classes A, B, C and E should be available. The content of each fire extinguisher varies depending on its recommended use, and is identifiable by a coloured label or specific wording on the label of the extinguisher. All extinguishers are coloured red so that they are easily visible, while the label and its wording describe the fire classification that it is suitable for, as follows.

- Red (water) extinguisher – for use on all except electrical fires.

- Black (carbon dioxide) extinguisher – for use on all fires.

- Blue (dry powder) extinguisher – for use on all fires.

Figure 4.3 Fire extinguisher.

The extinguishers must all be inspected and certificated by a competent person on an annual basis, and replaced as necessary. They should be located:

- within easy reach, ideally along escape routes

- in conspicuous positions (so not hidden by surrounding cupboards, for example)

- on wall mountings and signposted

- in a similar position on each level of the premises.

Evacuation and escape routes

During the risk assessment process, consideration should be given to whether, in the event of a fire, all persons on the premises could leave safely and reach a place of safety. There should be no possibility of anyone being cut off from escaping from the premises by either smoke or flames.

In particular, the following areas of fire safety must be complied with.

- Escape routes must be kept free from all obstructions to allow immediate evacuation from the premises if necessary. In particular, key-operated doors must be kept unlocked during normal working hours.

- Fire exits must lead directly to a place of safety, usually outside the building itself.

- They must be clearly marked by green ‘Fire Exit’ signs, with an accompanying pictogram of a running man ( Figure 4.4 ).

- Emergency lighting should be provided if necessary – this applies to hospitals rather than individual practices, and will have been identified during the fire risk assessment.

- Emergency doors should open manually in the direction of escape, and should not be operated electrically.

- Sliding or revolving doors should not be used as fire exits.

- All staff must be aware of the fire safety and evacuation process, and the procedure for evacuation should be practised at least annually.

- In addition, some staff should be charged with certain actions during the evacuation procedure, such as checking certain areas are clear or closing certain doors to contain the fire.

- Special consideration also needs to be given to the needs of disabled persons, and in small workplaces they should only be treated in ground-floor surgeries so that they can be easily evacuated from the premises.

Figure 4.4 Fire exit pictogram.

Figure 4.5 Fire escape poster.

The culmination of the findings from the fire risk assessment will ultimately be the development of a written fire policy or an emergency plan. This is a legal requirement in workplaces with more than five employees, and must be available to all employees and to the fire inspector. It should detail what action everyone on the premises should take in the event of a fire, and may be covered by a simple ‘Fire Action’ poster displayed in the reception area ( Figure 4.5 ). Larger premises will be expected to provide more detail still, and a suitable emergency plan should cover the following points.

- Action to take in the event of a fire.

- Alarm warnings (klaxon, whistle, etc.).

- How to call rescue services.

- Evacuation arrangements, including details for disabled persons.

- Assembly point.

- Method of accounting for all persons (daylist, for example).

- Key escape routes.

- Location and use of fire-fighting equipment.

- Responsibilities of nominated persons.

- Power shutdown methods.

- Staff training.

Smoking in the workplace

Smoking in all enclosed workplaces is now prohibited throughout the UK. All enclosed workplaces, which include all types of dental workplace, must display a ‘No Smoking’ sign at each entrance ( Figure 4.6 ) and the sign must contain the following wording: ‘No smoking. It is against the law to smoke in these premises’. Before the ban, careless disposal of cigarettes was a significant cause of fires in the workplace, so future analysis of fires and their causes will hopefully show a reduction in their incidence.

Figure 4.6 ‘No Smoking’ sign.

Health and Safety (First Aid) Regulations 1981

In addition to the identification of the signs and symptoms of the medical emergencies that may occur in dental practice and their correct management (see Chapter 6), the whole dental team should be able to deal with basic first aid procedures too.

Under the First Aid Regulations, all workplaces must have adequate first aid provision available for all employees, although there is no legal requirement to provide first aid treatment and facilities for non-employees, including patients.

The risk assessment process carried out to comply with general Health and Safety requirements should identify the hazards and risks associated with the workplace itself, and the occupational hazards associated with the business of dentistry. The hazards and risks identified will determine the extent of the first aid provision that is required for the premises and the employees.

In line with clinical governance guidelines (see Chapter 3), every practice must comply with the following requirements.

- All staff must be trained and certificated in basic life support (see Chapter 6).

- All workplaces with more than five employees should have at least one person trained in emergency first aid.

- All practices must have a first aid kit available, besides the full range of emergency drugs and emergency oxygen cylinders required under clinical governance guidelines.

- All practices must have an accident book, which is used to record all except major accidental events that occur on the premises to staff, patients or visitors.

- In the event of a medical emergency, the dental team must be able to reassure and help the casualty until the professionals arrive, and this may include basic life support (BLS) to maintain life if necessary.

Figure 4.7 First aid box.

The first aid kit that must be present in the dental workplace should be placed in an easy-access and signposted location. Regulations stipulate that it should be a green box with a white cross on ( Figure 4.7 ), and should contain minimum requirements with regard to sterile dressings, eye pads, bandages, etc.

Specific training for emergency first aid is provided by various HSE-approved organisations, including the British Red Cross and St John Ambulance. The first aid emergencies that should be covered are as follows, and are summarised below.

Severe bleeding

Burns and scalds, electrocution.

- Bone fractures

- The first aid principle is to restrict the blood flow to the wound and encourage clotting to reduce blood loss .

- Arterial bleeding will spurt rhythmically and be cherry red in colour.

- Venous bleeding will gush quickly and be dark red or purple in colour.

- Capillary bleeding will ooze slowly and be dark red in colour.

- The required treatment is to raise the injured part above the level of the heart if possible, and apply direct pressure to the wound for up to 15 min using a clean dressing.

- Any foreign objects present should not be removed from the wound.

- As a last resort, severed arteries can be compressed against the underlying bone for up to 15 min, using a tourniquet.

- The casualty should be removed to hospital once the bleeding is under control, or the emergency services should be called if it cannot be controlled.

Possible causes of severe bleeding in the dental workplace include unexpected surgical trauma, traumatic falls, severe sharps injury, etc.

- A burn is an injury caused by dry heat, corrosive chemicals or irradiation.

- A scald is a wet burn caused by steam or hot liquids.

- The first aid principles are to prevent infection of the underlying tissues and to prevent clinical shock developing due to the loss of blood serum.

- The required treatment is to remove the casualty from the source of danger if possible, and to reassure them if they are still conscious.

- The injured part should be placed under cold water for a minimum of 10 min, to reduce blistering.

- Any restrictive jewellery should be removed before any swelling occurs, but clothing should be left in place as its removal may causing tearing of the tissues.

- Seek medical help for all but minor burns or scalds, and be prepared to carry out BLS if clinical shock develops in severe cases.

Possible causes of burns in the dental workplace include touching hot equipment or instruments, touching naked flames, various chemicals (etching gel, bleach products, other cleaning agents) and uncontrolled exposure to x-rays.

- The first aid principle is to limit the exposure of the casualty to the poison , and maintain life if necessary.

- Consult any available COSHH documentation for the required first aid advice.

- The required treatment is to remove the casualty from the source of the poison, without endangering other lives.

- Where vapours are the cause, provide good ventilation of the area immediately.

- Vomiting should not be induced, as caustic poisons will burn the digestive tract each time they pass through.

- Maintain the airway and carry out BLS if necessary.

- Seek urgent medical help.

Possible causes in the dental workplace include the ingestion or inhalation of various agents, such as corrosive chemicals (bleach products and acids), toxic chemicals (cleaning agents, processing chemicals, mercury), toxic vapours (processing chemicals, mercury, gases).

- This is caused by an electrical current passing through the body, causing burns and possibly affecting the electrical conduction of the heart itself.

- The first aid principle is to remove the casualty from the electrical source and maintain life until help arrives .