What young entrepreneurs learned in secondary school…and didn’t: a study summary

- Original Paper

- Published: 28 November 2023

- Volume 6 , pages 399–423, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Gregory R. L. Hadley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5603-5005 1 ,

- Madison Tennant 1 &

- Bethany Ripoll 1

144 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This qualitative study sought to identify, and understand, the key secondary school educational experiences and activities that supported the entrepreneurial development of young, practicing entrepreneurs. Data were gathered from a diverse pool of nine, under aged 40 entrepreneurs, from a variety of sectors, who offered their recollections of secondary school, and critically explored how those experiences contributed, if at all, to their entrepreneurial acumen and success. The study found that secondary school did not directly support explicit entrepreneurial learnings but, rather, was a place where latent entrepreneurial learnings occur, including the development of many, accepted, entrepreneurial knowledge, skills, and attitudes. A variety of pedagogical and curricular implications are explored as part of a broader analysis of how schooling can support the entrepreneurial propensity of youth.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

‘We Don’t Need No Education?’: Moving Towards the Integration of Tertiary Education and Entrepreneurship

The Emergence of Entrepreneurship Education

Entrepreneurial entrepreneurship youth education: initiating grounded theory

Richard J. Arend

Abdelkarim, A. (2021). From entrepreneurial desirability to entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The need for entrepreneurship education—A survey of university students in eight countries. Entrepreneurship Education, 4 , 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41959-021-00046-8

Article Google Scholar

Almeida, F., & Morais, J. (2023). Strategies for developing soft skills among higher engineering courses. Journal of Education, 203 (1), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220574211016417

Alemedia, F., & Devedzic, V. (2022). The relevance of soft skills for entrepreneurs. Journal for East European Management Studies, 27 (1), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.5771/0949-6181-2022-1

Arend, R. J. (2019). Entrepreneurial entrepreneurship youth education: Initiating grounded theory. Entrepreneurship Education, 2 , 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41959-019-00014-3

Arvanites, D. A., Glasgow, J. M., Klingler, J. W., & Stumpf, S. A. (2006). Innovation in entrepreneurship education. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 9 , 29–44.

Google Scholar

Ayodotun, S. I., Mozie, D., & AdebanjiWlliam, A. A. (2021). Entrepreneurial characteristics amongst university students: Insights for understanding entrepreneurial intentions amongst youths in a developing economy. Education & Training, 63 (1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-09-2019-0204

Azim, M. T. (2013). Entrepreneurship training in Bangladesh: A case study on small and cottage industries training institute. Life Science Journal, 10 (12), 188–201.

Azoulay, P., Jones, B., Kim, J. D., & Miranda, J. (2018). The average age of successful startup founders. Harvard Business Review, 21 , 1–12.

Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., Punie, Y., & Van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComp: The entrepreneurship competence framework. In JRC science for policy report (Issue June). https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5e633083-27c8-11e6-914b-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

Bell, R. (2015). Developing the next generation of entrepreneurs: Giving students the opportunity to gain experience and thrive. The International Journal of Management Education, 13 (1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2014.12.002

Bevan, D., & Kipka, C. (2012). Experiential learning and management education. Journal of Management Development, 31 (3), 193–197. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711211208943

Biesta, G. (2009). Good education in an age of measurement: On the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21 (1), 33–46.

Biesta, G. J. J. (2004). Education, accountability and the ethical demand. Can the democratic potential of accountability be regained? Educational Theory, 54 (3), 233–250.

Bikse, V., Riemere, I., & Rivza, B. (2014). The improvement of entrepreneurship education management in Latvia. Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences, 140 , 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.388

Blanda, B., & Urbancikova, N. (2021). Perceptions and attitudes of young people towards social entrepreneurship. Management Research and Practice, 13 (2), 5–14.

Boffo, V., Gamberi, L., Lim, H., & Aisha, N. (2020). Entrepreneurship education around the world: A possible comparison. Andragogical Studies, 1 , 77–100. https://doi.org/10.5937/AndStud2001077B

Busenitz, L. W., Plummer, L. A., Klotz, A. C., Shahzad, A., & Rhoads, K. (2014). Entrepreneurship research (1985–2009) and the emergence of opportunities. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38 (5), 981–1000. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12120

Caird, S. (1990). What does it mean to be enterprising. British Journal of Management, 1 (1), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.1990.tb00002.x

Cinque, M. (2015). Comparative analysis on the state of the art of Soft Skill identification and training in Europe and some Third Countries. Speech at “Soft Skills and their role in employability : New perspectives in teaching, assessment and certification.” Bertinoro, FC, Italy.

Cimatti, B. (2016). Definition, development, assessment of soft skills and their role for the quality of organizations and enterprises. International Journal for Quality Research, 10 (1), 97–130. https://doi.org/10.18421/IJQR10.01-05

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Dodd, S., Lage-Arias, S., Berglund, K., Jack, S., Hytti, U., & Verduijn, K. (2022). Transforming enterprise education: Sustainable pedagogies of hope and social justice. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 34 (7–8), 686–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2022.2071999

Edwards, L. J., & Muir, E. (2012). Evaluating enterprise education: Why do we do it? Education + Training, 54 (4), 278–290. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911211236136

Elert, N., Andersson, F. W., & Wennberg, K. (2014). The impact of entrepreneurship education in high school on long-term entrepreneurial performance. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 111 , 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2014.12.020

Elo, J., & Kurten, B. (2020). Exploring points of contact between enterprise education and open-ended investigations in science education. Education Inquiry, 11 (1), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2019.1633903

Fayolle, A. (2018). Personal views on the future of entrepreneurship education . Edward Elgar Publishing.

Book Google Scholar

Fiet, J. O. (2001). The pedagogical side of entrepreneurship theory. Journal of Business Venturing, 16 (2), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00042-7

Fillis, I., & Rentschler, R. (2010). The role of creativity in entrepreneurship. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 18 , 49–81. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218495810000501

Geldhof, G., Porter, T., Weiner, M. B., Malin, H., Bronk, K. C., Agans, J. P., Mueller, M., Damon, W., & Lerner, R. M. (2014). Fostering youth entrepreneurship: Preliminary findings from the young entrepreneurs study. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24 (3), 431–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12086

Göksen-Olgun, S., Groot, W., & Wakkee, I. (2022). Entrepreneurship programs and their underlying pedagogy in secondary education in the Netherlands. Entrepreneurship Education, 5 , 261–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41959-022-00078-8

Gonzalez, I., Lauroba, N., & Beitia, A. (2019). How can design thinking promote entrepreneurship in young people? The Design Journal, 22 (1), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1595853

Government of Canada. (2010). The teaching and practice of entrepreneurship within Canadian higher education institutions . https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/sme-research-statistics/en/research-reports/teaching-and-practice-entrepreneurship-within-canadian-higher-education-institutions/teaching-and-practice-entrepreneurship-within-canadian-higher-education-institutions

Government of Nova Scotia. (2014). Disrupting the status quo: Nova Scotians demand a better future for every student: Report of the minister’s panel on education . https://www.ednet.ns.ca/docs/disrupting-status-quo-nova-scotians-demand-better.pdf

Hadley, G. (2022). A characterization and pedagogical analysis of youth entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 6 (2), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/25151274221096035

Hägg, G., & Gabrielsson, J. (2019). A systematic literature review of the evolution of pedagogy in entre-preneurial education research. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26 , 829–861. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-04-2018-0272

Hägg, G., & Kurczewska, A. (2021). Entrepreneurship education: Scholarly progress and future challenges . Routledge.

Hamidi, D. Y., Wennberg, K., & Bergland, H. (2008). Creativity in entrepreneurship education. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 15 (2), 304–320. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626000810871691

Harlan, M. A. (2016). Constructing youth: Reflecting on defining youth and impact on methods. School Libraries Worldwide, 22 (2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.29173/slw6917

Hekman, B. (2007). Attitudes of young people toward entrepreneurship . Bertelsmann Stiftung. https://www.bertelsmannstiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/GP_Attitudes_of_young_people_toward_entrepreneurship.pdf

Hindle, K. (2007). Formalizing the concept of entrepreneurial capacity . Paper presented at the refereed proceedings of the 2007 ICSB World Conference, Finland: Turku School of Economics.

Hongtao, Y., Zhang, L., Wu, J. Y., & Shi, H. (2021). Benefits and costs of happy entrepreneurs: The dual effect of entrepreneurial identity on entrepreneurs’ subjective well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 12 , 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910710834120

Hynes, B., & Richardson, I. (2007). Entrepreneurship education: A mechanism for engaging and exchanging with the small business sector. Education + Training, 49 (8/9), 732–744. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910710834120

Ivankova, N. V., Creswell, J. W., & Stick, S. L. (2006). Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: From theory to practice. Field Methods, 18 (1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05282260

Jesson, J. K., Matheson, L., & Lacey, F. M. (2011). Doing your literature review: Traditional and systematic techniques . SAGE Publications Ltd.

Jones, B., & Iredale, N. (2010). Enterprise education as pedagogy. Education + Training, 52 (1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911011017654

Jones, C., & English, J. (2004). A contemporary approach to entrepreneurship education. Education and Training, 46 (8/9), 416–423. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910410569533

Jones, C., Penaluna, K., & Penaluna, A. (2019). The promise of andragogy, heutagogy and academagogy to enterprise and entrepreneurship pedagogy. Education & Training, 61 (9), 1170–1186. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-10-2018-0211

Karunua, C., Sudarsih, V., & Sunardi, C. R. (2017). The effect of soft skills and innovative attitudes on entrepreneurship competency. Journal Ekuilibrium, 2 (1), 47–54.

Kautz, J. (1999). Entrepreneurs add vitality to the economy. Entrepreneurs Library Weekly . http://entrepreneurs.about.com/smallbusiness/entrepreneurs/library/weekly/199/aa070

Kokkonen, L., & Koponen, J. (2020). Entrepreneurs’ interpersonal communication competence in networking. Prologi . https://doi.org/10.33352/prlg.91936

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4 (2), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2005.17268566

Kim, G., Kim, D., Lee, W. J., & Joung, S. (2021). The effect of youth entrepreneurship education programs: Two large-scale experimental studies. SAGE Open . https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020956976

Kurniawan, J. E., et al. (2019). Developing a measurement instrument for high school students’ entrepreneurial orientation. Cogent Education, 6 (1), 1564423.

Lackéus, M. (2014). An emotion based approach to assessing entrepreneurial education. The International Journal of Management Education, 12 (3), 374–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2014.06.005

Lackeus, M. (2015). Developing entrepreneurial competencies: An action-based approach and classification in entrepreneurial education. Management of Organizational Renewal & Entrepreneurship , 1–124. http://vcplist.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Lackeus-Licentiate-Thesis-2013-Developing-Entrepreneurial-Competencies.pdf

Liljedahl, P. (2020). Building thinking classrooms in mathematics, grades K-12: 14 practices for enhancing learning . Corwin.

Lin, J., Qin, J., & Lyons, T. (2023). Planning and evaluating youth entrepreneurship education programs in schools: A systematic literature review. Entrepreneurship Education, 6 , 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41959-023-00092-4

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. The Academy of Management Review, 27 (7), 135–172. https://doi.org/10.2307/258632

Marlino, D., & Wilson, F. (2003). Teen girls on business: Are they being empowered? Boston and Chicago: Simmons School of Management and The Committee of 200. http://girlsschools.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Teen-Girls-on-Business-Are-They-Being-Empowered.pdf

Merriam, S., & Tisdale, E. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation . Jossey-Bass.

Miles, M., & Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook . Sage.

Mills, G. E., & Gay, L. R. (2016). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and applications (11th ed.). Pearson.

Moberg, K. (2014). Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education: From ABC to Ph.D. Copenhagen Business School (CBS). https://research.cbs.dk/en/publications/assessing-the-impact-of-entrepreneurship-education-from-abc-to-phd

Morandin, G., Bergami, M., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2015). The hierarchical cognitive structure of entrepreneur motivation toward private equity financing. Venture Capital, 8 (3), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691060600748546

Mwasalwiba, E. S. (2010). Entrepreneurship education: A review of its objectives, teaching methods, and impact indicators. Education + Training, 52 (1), 20–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911011017663

Nabi, G., Walmsley, A., Liñan, F., Akhtar, I., & Neame, C. (2018). Does entrepreneurship education in the first year of higher education develop entrepreneurial intentions? The role of learning and inspiration. Studies in Higher Education, 43 (3), 452–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1177716

National Research Council. (1994). Learning, remembering, believing: Enhancing human performance . National Academies: Sciences Engineering, Medicine.

Ndofirepi, T. M. (2020). Relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial goal intentions: Psychological traits as mediators. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 9 (1), 1–20.

Neck, H. M., Greene, P. G., & Brush, C. G. (2014). Teaching entrepreneurship: A practice-based approach . Edward Elgar Publishing.

Oosterbeek, H., Van Praag, M., & Ijsselstein, A. (2010). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. European Economic Review, 54 (3), 442–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2009.08.002

Owusu-Ansah, W., & Poku, K. (2012). Entrepreneurship education, a panacea to graduate unemployment in Ghana. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2 (15), 211–220.

PadovezCualheta, L., Borges, C., Filho Camargo, A., & Tavares, L. (2019). An entrepreneurial career impacts on job and family satisfaction. RAUSP Management Journal, 54 (2), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAUSP-09-2018-0081

Papulová, Z., & Papula, J. (2015). Entrepreneurship in the eyes of the young generation. Procedia Economics and Finance, 34 , 514–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2212-5671(15)01662-7

Pigozne, T., Luka, I., & Surikova, S. (2019). Promoting youth entrepreneurship and employability through non-formal and informal learning: The Latvia case. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 9 (4), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.26529/cepsj.303

Piperopoulos, P., & Dimov, D. (2014). Burst bubbles or build steam? Entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 53 (12), 970–985. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12116

Porfírio, J. A., Carrilho, T., Jardim, J., & Wittberg, V. (2022). Fostering entrepreneurship intentions: The role of entrepreneurship education. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 32 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.53703/001c.32489

Rahman, H., Hasibuan, A. F., Husrizal, D. S., Hafiz, G. S., & Prayogo, R. (2022). Intrapreneurship: As the outcome of entrepreneurship education among business students. Cogent Education . https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2022.2149004

Rantanen, T., & Toikko, T. (2012). Young people’s attitudes towards entrepreneurship in Finnish society. International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanity Studies, 4 (1–2), 399–408.

Rasmussen, E. A., & Sørheim, R. (2006). Action-based entrepreneurship education. Technovation, 26 (2), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2005.06.012

Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G. T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33 (3), 761–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00308.x

Robinson, S., & Stubberud, H. A. (2014a). Teaching creativity, team work and other soft skills for entrepreneurship. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 17 (2), 186–197.

Robinson, S., & Stubberud, H. A. (2014b). Elements of entrepreneurial orientation and their relationship to entrepreneurial intent. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 17 (2), 1–11.

Russell, S., Sobel, K. A., & King, B. (2008). Does school choice increase the rate of youth entrepreneurship? Economics of Education Review, 27 (4), 429–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2007.01.005

Sahlman, W. (2017). Reviving entrepreneurship. Harvard Business Review, 90 (3), 116–119.

Saygin, M. (2020). The entrepreneurial characteristics of young entrepreneur councils: A Phenomenon. International Journal of Eurasia Social Sciences, 11 (39), 203–223. https://doi.org/10.35826/ijoess.2707

Schmidt, J. J., Soper, J. C., & Facca, T. M. (2012). Creativity in the entrepreneurship classroom. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 15 , 123–131.

Schultz, T. W. (1963). The economic value of education . Columbia University Press.

Sherman, P. A., Sebora, T., & Digman, L. A. (2008). Experiential entrepreneurship in the classroom: Effects of teaching methods on entrepreneurial career choice intentions. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 11 , 29–42.

Shittu Ibrahim, A. (2017). Promoting youth entrepreneurship: The role of mentoring. IDS Bulletin, 48 (3), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.19088/1968-2017.132

Sirelkhatim, F., & Gangi, Y. (2015). Entrepreneurship education: A systematic literature review of curricula contents and teaching methods. Cogent Business & Management, 2 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2015.1052034

Sweetland, S. R. (1996). Human capital theory: Foundations of a field of inquiry. Review of Educational Research, 66 (3), 341–359. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543066003341

Tarabishy, A., Solomon, G., Femald, L., & Saghkin, M. (2005). The entrepreneurial leader’s impact on the organization’s performance in dynamic markets. Journal of Private Equity . https://doi.org/10.3905/jpe.2005.580519

Touloumakos, A. (2020). Expanded yet restricted: A mini review of the soft skills literature. Frontiers in Psychology . https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02207

Ward, T. (2004). Cognition, creativity, and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 19 , 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00005-3

Wilson, F., Marlino, D., & Kickul, J. (2004). Our entrepreneurial future: Examining the diverse attitudes and motivations of teens across gender and ethnic identity. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 9 (3), 177–197.

Wraae, B., & Walmsley, A. (2020). Behind the scenes: Spotlight on the entrepreneurship educator. Education and Training, 62 (3), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-01-2019-0009

Yang, C. (2021). The design logic and development enlightenment of American social entrepreneurship curriculum. Entrepreneurship Education, 4 , 335–350.

Zhang, J., & Price, A. (2020). Developing the enterprise educators’ mindset to change the teaching methodology: The case of Creating Entrepreneurial Outcomes (CEO) Programme. Entrepreneurship Education, 3 , 339–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41959-020-00037-1

Zozimo, R., Jack, S., & Hamilton, E. (2017). Entrepreneurial learning from observing role models. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29 (9–10), 889–911. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1376518

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was generously supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, NS, Canada

Gregory R. L. Hadley, Madison Tennant & Bethany Ripoll

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gregory R. L. Hadley .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

This research, which includes human subjects, was approved by the Research Ethics Board of St. Francis Xavier University. The authors committed to the high ethical standards at all points of the project.

A note on dissemination

As part of our efforts to disseminate our research more widely, this project includes an online component. Our data collection was filmed, edited, and uploaded to YouTube as part of a web series that explores entrepreneurship education. The access link can be found here: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLln2DK7TSyboPYOWe02FHQbi8I2dezLvm .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hadley, G.R.L., Tennant, M. & Ripoll, B. What young entrepreneurs learned in secondary school…and didn’t: a study summary. Entrep Educ 6 , 399–423 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41959-023-00106-1

Download citation

Received : 11 June 2023

Revised : 02 October 2023

Accepted : 08 November 2023

Published : 28 November 2023

Issue Date : December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41959-023-00106-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Entrepreneurship

- Entrepreneurship education

- Youth entrepreneurship

- Entrepreneurship pedagogy

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News Center

- In the Media

- Faculty Research Interests

You are here

Researchers examine the secrets of successful young entrepreneurs.

The Stanford Center on Adolescence, led by Bill Damon, has teamed up with researchers at Tufts University to learn how we can effectively foster enterprising skills among adolescents and young adults.

School of Education News By Brianna Liang and Amy Yuen

The passing of Apple CEO Steve Jobs last fall has inspired a flurry of speculation about the roots of his entrepreneurial success. How do some entrepreneurs like Jobs develop their abilities to succeed at a young age? And how can we foster these enterprising qualities among young people? These are questions that the Young Entrepreneurs Study (YES) project has been investigating. YES, a three-year, longitudinal study on entrepreneurship development among young adults, is a partnership between the Stanford Center on Adolescence and the Institute of Applied Research in Youth Development at Tufts University. The John Templeton Foundation has provided support to the project with a $2 million grant. YES examines how entrepreneurial purpose, achievements, character attributes, and skills are developed among diverse adolescents and young adults in the U.S. It seeks to identify the cognitive, motivational, behavioral, and environmental factors that help individuals develop enterprising skills. “Entrepreneurship is a proven pathway to prosperity and freedom,” said Principal Investigator William Damon , director of the Stanford Center on Adolescenc e and a professor of education at Stanford University. “Yet little is known about how individuals develop such capacities during the years of youth and young adulthood, when entrepreneurship skills are often acquired. Without knowledge about how entrepreneurship abilities develop, efforts to create effective educational programs to foster entrepreneurial skills in young people will be limited in their effectiveness.” Researchers are studying the development of entrepreneurship among over 4,000 youth from ages 15 to 27 over a three-year period. A wide range of racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse youth are participating from the Bay Area, the greater Boston area, and the Muncie, Indiana area. These areas were chosen for their diverse demographics, as well as for the presence of either general postsecondary educational institutions, or institutions focused on the enhancement of entrepreneurship. Researchers will employ measurement models that assess youth entrepreneurial purpose and achievement, qualities of character and other attributes associated with youth entrepreneurship, as well as social support and mentoring. The investigators will employ the Bundick, et al. (2006) Stanford Youth Purpose Survey, a measure developed in Damon’s laboratory during a prior John Templeton-foundation supported project. In addition to this quantitative measure that will be administered to the entire sample, 32 subjects will participate in an interview sub-sample in order to provide a more elaborate qualitative understanding of entrepreneurial purpose and achievement. Damon and other researchers hope that the results of the study will enable educators and business leaders with information about how to promote entrepreneurship achievement in adolescents and young adults from diverse backgrounds, including those who have grown up in disadvantaged settings. “The fields of developmental science, economics, and education have not provided a lot of information about how entrepreneurship develops,” added Co-investigator Richard Lerner , the Bergstrom Chair in Applied Developmental Science at Tufts University and director of the Institute for Applied Research in Youth Development at Tufts. “We hope that YES will provide the empirical data needed for providing this understanding and for creating effective educational programs and policies designed to foster entrepreneurship interests and achievements among diverse youth.” For more information about the Stanford Center on Adolescence and the Youth Entrepreneurship Study, visit http://coa.stanford.edu .

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

A Systems View Across Time and Space

- Open access

- Published: 28 January 2020

A systematic literature review of the influence of the university’s environment and support system on the precursors of social entrepreneurial intention of students

- Carlos Bazan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8920-7486 1 ,

- Hannah Gaultois 2 ,

- Arifusalam Shaikh 3 ,

- Katie Gillespie 4 ,

- Sean Frederick 4 ,

- Ali Amjad 4 ,

- Simon Yap 4 ,

- Chantel Finn 4 ,

- James Rayner 4 &

- Nafisa Belal 4

Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship volume 9 , Article number: 4 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

49 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

This systematic literature review aims at understanding the influence of the university’s environment and support system (ESS) in shaping the social entrepreneurial intention (SEI) of post-secondary education students. Social entrepreneurs play an important role in the economic and social developments of the communities in which they operate, thus many post-secondary institutions are starting to encourage more students to engage in social entrepreneurial behaviour. Consequently, there is a need for systematic approaches to evaluate the impact of various motivational factors related to the university’s entrepreneurial ecosystem that could affect the SEI of students. Based on a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis of the antecedents of the SEI of post-secondary education students, the authors proposed a customized SEI model that modifies and extend the one proposed by Hockerts (Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 2017) and Mair and Noboa (Social entrepreneurship, 2006). This study fills a gap in the literature by providing a methodology grounded in theory that can help universities to design their educational and other interventions aimed at encouraging more students to consider social entrepreneurship as a viable career choice after graduation.

Introduction

This systematic literature review aims at understanding the influence of the university’s environment and support system (ESS) in shaping the social entrepreneurial intention (SEI) of post-secondary education students. Social entrepreneurs play an important role in the economic and social developments of the communities in which they operate (Mair & Noboa, 2006 ). They are a special type of entrepreneurs who are driven by a variety of motives including the alleviation of poverty, hunger or illiteracy; the improvement of human health; the reparation of social, legal or economic injustice; and the preservation of the environment for future generations (Austin, Stevenson, & Wei-Skillern, 2006 ; Seelos & Mair, 2005 ; Vidal, 2005 ). Despite their varied motivations, the one common denominator among all social entrepreneurs is the utilization of limited resources in new and creative ways to generate social value, as opposed to the maximization of personal and shareholder’s wealth (Zadek & Thake, 1997 ). Social entrepreneurs are also different from philanthropists in that they do not use their excess wealth to support worthy causes by sponsoring their favourite not-for-profit organizations, but rather mobilize the scarce resources necessary to address a problem that both the free market and government failed to solve (Khanin, 2011 ). Given the relevance of social entrepreneurs in today’s society, many post-secondary institutions are starting to encourage more students to participate in social entrepreneurial initiatives, i.e. to engage in social entrepreneurial behaviour (Hockerts, 2015 ; Miller, Grimes, Mcmullen, & Vogus, 2012 ; Smith, Kickul, & Coley, 2010 ). Consequently, there is a need for systematic approaches to evaluate the impact of various motivational factors related to the university’s entrepreneurial ecosystem that could shape the SEI of students.

There is evidence in the literature that contextual and situational factors, e.g. the university’s ESS, affect entrepreneurial intention by influencing the precursors (antecedents) of intention (Ajzen, 1987 ; Boyd & Vozikis, 1994 ; Krueger & Carsrud, 1993 ; Lee & Wong, 2004 ; Tubbs & Ekeberg, 1991 ). Situational variables typically have an indirect influence on intention by influencing key attitudes and general motivation to behave (Krueger, Reilly, & Carsrud, 2000 ). Trivedi ( 2016 ) has identified three motivational factors of the university’s ESS that could influence the precursors of entrepreneurial intention. He suggested that targeted cognitive and non-cognitive supports, and to a lesser extent the general educational support, seemed to have a positive correlation with the precursors of entrepreneurial intention. Trivedi ( 2016 ) also argued that a well-crafted entrepreneurship education curriculum could significantly improve students’ entrepreneurial competencies and raise their enthusiasm to become entrepreneurs. Bazan et al. ( 2019 ) have successfully applied a variant of Trivedi’s ( 2016 ) entrepreneurial intention model to understand the influence of the university’s ESS on the precursors of the entrepreneurial intention of students. Following similar rationale, the authors posit that contextual and situational factors such as the university’s ESS will also affect the SEI of students. This systematic literature review intends to gather enough evidence to support the aforementioned arguments.

The authors divided the remainder of the article in four sections as follows. “ Research methodology ” section describes the systematic literature review and narrative synthesis conducted for answering two research questions. “ Results ” section illustrates the state-of-the knowledge as it pertains to the antecedents of the SEI of students. “ Discussion ” section describes the proposed SEI model based on the results of the systematic literature review and narrative synthesis and the proposed instrument to operationalize the model. The paper ends with the “ Conclusion ” section and possible future work.

Research methodology

The authors conducted a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis of the effect of the university’s ESS in shaping the SEI of students. They designed the study as a way to understand the motivational factors related to the university’s entrepreneurial ecosystem that could affect the SEI of students (Popay, Roberts, Sowden, & Petticrew, 2006 ). There were two research questions guiding the literature review. (1) Does the university’s ESS affect the precursors of SEI of students? (2) How did previous studies measure the effect of the university’s ESS on the precursors of SEI of students? To answer these questions, the authors searched the SCOPUS electronic database platform—the largest citation database of peer-reviewed literature—from inception until October 2018. They used a systematic and repeatable approach to identify relevant publications describing the contents of interest. This included that use of precisely selected words and terms that allowed for a more inclusive search of articles in the database. For replicability, Table 1 provides the key terms, keywords and Boolean expressions used to query the literature.

The query returned 112 publications that met the search criteria, of which 67 documents appeared in scientific or professional journals (articles and reviews), 30 documents were parts of book publications and 15 documents were included in conference proceedings. The authors assumed that journal articles were the only documents validated by peer review, thus these were the only documents included in the literature review (Jones, Coviello, & Tang, 2011 ). As a starting point, they conducted a citation analysis to identify the most influential articles within the 67 returned documents. The frequency of citation reflects the importance and quality of the publication as determined by other researchers (Xi, Kraus, Filser, & Kellermanns, 2013 ). It is also an indication that the scientific knowledge conveyed in these articles is the foundation of foreground knowledge of more recent articles (Acedo & Casillas, 2005 ; Casillas & Acedo, 2007 ; Liñán & Fayolle, 2015 ). The citation analysis produced a ranking of articles sorted from the most cited to the least cited articles. Five of the authors read the abstracts of the ranked publications for the relevance of the contents and their potential for answering the two research questions. When in doubt, the entire article was read to discern its inclusion. This screening produced 40 documents that were retrieved for further scrutiny. The full text documents were scrutinized independently by three of the authors for whether those studies purposely posited a hypothesis, a research question or conjecture regarding the influence of the university’s ESS on the SEI of students. This process revealed that no previous researcher has considered the SEI of students as influenced by the university’s ESS per se. Some researchers who studied the influence of the university on the SEI of students did so in relation to the effect of social entrepreneurship education (Adelekan, Williamson, & Atiku, 2018 ; Kedmenec, Rebernik, & Tominc, 2017 ; Kwong, Thompson, & Cheung, 2012 ; Piperopoulos & Dimov, 2015 ; Smith & Woodworth, 2012 ; Tshikovhi & Shambare, 2015 ). Thus, the authors modified the inclusion criteria to contain articles that deal with the SEI of students in more general terms. In other words, articles that used students as subjects of the study, with the purpose of extracting some antecedents related to the university’s ESS and their effects on students.

In total, 25 documents met the new inclusion criteria and were examined in extenso by four of the authors. The authors also searched the reference lists of these documents (“snowballing”) for additional documents that might meet the inclusion criteria. Three additional documents were retrieved this way. After reading the documents several times by four of the authors and highlighting relevant contents using Qiqqa v.79s, the corresponding author used ATLAS.ti® v.8 to perform open coding to record examples of studies describing (1) precursors of SEI of students, (2) models to assess the SEI of students and (3) results and conclusions. Open coding was useful for identifying, naming, categorizing and describing the relevant contents found in the text. The study then used axial coding to break down the results of the open coding process into core findings that were used to develop the narrative synthesis and answer the research questions. Axial coding was used to relate codes from the open coding to each other, via a combination of inductive and deductive thinking (Long, Strauss, & Corbin, 2006 ).

The authors used tabulation to develop a preliminary synthesis in the literature review process. Tabulation is a common approach used in all types of systematic review to represent both quantitative and qualitative data visually (Popay et al., 2006 ). Tabulation was useful to develop the initial description of the included studies and to begin to identify patterns across studies. Table 2 provides the preliminary synthesis of results across studies (Forbes & Griffiths, 2002 ; Fulop, 2001 ; Jensen & Allen, 1996 ; Jones, 2004 ). Due to space limitation, Table 2 shows only the hypotheses formulated by the different researchers who used SEI models based on theory, and stated whether rigorous data analysis supported or rejected their proposed hypotheses. Table 2 is followed by a chronological narrative synthesis describing the evolution of the knowledge on the precursors of SEI of students. In the narrative synthesis, the authors included articles where researchers studied the SEI of students and formulated hypotheses, research questions or conjectures on the antecedents of social entrepreneurial intention. Both the tabulated and narrative syntheses informed the development of the proposed model and formulation of the proposed hypotheses that can be used in future studies of the influence of the university’s ESS on the SEI of students. Finally, Table 3 summarizes the findings from the tabulation and the narrative synthesis approaches as they relate to the two research questions.

Prieto ( 2011 ) was among the first authors to study the precursors of SEI of African American and Hispanic students in the USA. He tried to determine if hope moderates the relationship between a proactive personality and SEI. His findings showed that there exists a positive relationship between having a proactive personality and the SEI of students. However, Prieto’s ( 2011 ) findings also established that hope did not moderate that relationship. Kirby and Ibrahim ( 2011 ) conjectured that if young people are made aware of the concept of social entrepreneurship, recognize its role and importance to society and believe they have the ability to create a new venture, they will do so. They explored awareness of social entrepreneurship of students in Egypt and how the education system might need to adapt to help encourage more students to start social ventures upon graduation. The findings by Kirby and Ibrahim ( 2011 ) show that students were aware of the concept but that there was some confusion over what a social entrepreneur is or does.

On subsequent studies, Smith and Woodworth ( 2012 ) conjectured that a well-crafted social entrepreneurship course can instil in students both the desire to find solutions to critical social issues and the belief that they have the ability to make a difference. They provided multiple anecdotal examples of specific course contents and group projects that have led to active student engagement in social entrepreneurial endeavours. Kwong et al. ( 2012 ) conducted a pedagogical study to explore the effectiveness of social business plan teaching in inducing social and civic awareness and intentionality among business students. They compared social business plan teaching with the more traditional case study approach. Their study found that both approaches can be successful in raising awareness and improving the attitudes of participating students. Prieto, Phipps and Friedrich ( 2012 ) assessed the SEI of African-American and Hispanic students in the USA using a SEI scale modified from an entrepreneurial decision scale by Chen, Greene and Crick ( 1998 ). They concluded that African-American and Hispanic students possess low intentions to become social entrepreneurs.

Afterwards, Salamzadeh, Azimi and Kirby ( 2013 ) investigated awareness, intention/support and the contextual elements among students in Iran in order to find the gaps in social entrepreneurship education. Their survey was conducted in three different faculties (entrepreneurship, management and engineering), to evaluate the SEI of students and to capture varied orientations. Their findings show significant awareness of the concept and high SEI among students but a lack of sufficient attention to contextual elements and adequate support. Othman and Ab Wahid ( 2014 ) identified the social entrepreneurship dimensions that emphasize the specific personal characteristics of social entrepreneurs among students in the Students in Free Enterprise program in Malaysia. Their findings suggest a strong positive relationship between specific personal characteristics of social entrepreneurs and students in the program. Moorthy and Annamalah ( 2014 ) examined the SEI of students in Malaysia. In order of importance, they found that the following elements are influential in the formation of intention to start a social enterprise: social support, willpower, experience, empathy and regional factors surrounding the students.

Next, Tshikovhi and Shambare ( 2015 ) tested the association among practical entrepreneurship training (as operationalized by participation in Enactus projects), personal attitudes, entrepreneurial knowledge and SEI of students in South Africa. Findings of their study indicated that both entrepreneurial knowledge and personal attitude have significant influence on SEI. Tshikovhi and Shambare ( 2015 ) also found that personal attitude has a stronger influence on the SEI of students, while entrepreneurial knowledge seems to positively influence the personal attitudes of students. Konakll ( 2015 ) tried to determine the effects of self-efficacy on the social entrepreneurship characteristics of pre-services teachers (students) in Turkey. Her results revealed that effort and persistence—which are general self-efficacy dimensions—predicted personal creativity and risk-taking features of social entrepreneurship. According to her findings, the initiative, effort and persistence dimensions predict the self-confidence, which is a characteristic of social entrepreneurs. Shek and Lin ( 2015 ) identified the attributes of successful social entrepreneurs and suggested ways in which students in Hong Kong can be nurtured to become social entrepreneurs. They concluded that leadership competence, moral character and caring dispositions are the three attributes of a successful service leader.

Successively, Ashour ( 2016 ) explored the attitudes towards business and social entrepreneurship of students in the United Arab Emirates. She conjectured that the lack of awareness among students regarding social entrepreneurship and the lack of education opportunities in this particular field are adversely affecting students’ attitudes towards these areas. Ashour ( 2016 ) concluded that there is a gap between students’ entrepreneurial aspirations on the one hand and their readiness in terms of training and education on the other hand. Sezen-Gultekin and Gur-Erdogan ( 2016 ) sought to determine the relation between the lifelong learning tendency and social entrepreneurship characteristics (and vice versa) of pre-service teachers (students). Results of their analysis determined that there is a significant relationship between lifelong learning tendencies and social entrepreneurship characteristics of students. Furthermore, their study also found a moderate positive and significant relationship between lifelong learning tendencies and personal creativity, self-reliance and risk taking—which are sub-dimensions of social entrepreneurship. Politis et al. ( 2016 ) investigated if SEI is shaped in the same way as entrepreneurial intentions by assessing the extent to which Ajzen’s ( 1991 ) theory of planned behaviour (TPB) could be applied to SEI of students in the South-East European region. They also probed the factors that directly correlate to SEI and whether they are the same as those that directly correlate to entrepreneurial intentions. Their study found that the TPB was successful at predicting both social and commercial entrepreneurial intentions of students.

More recently, Hockerts ( 2017 ) tested the SEI model proposed by Mair and Noboa ( 2006 ) to predict the SEI of students in a Scandinavian business school. He also extended the model by including prior experience with social problems as an additional variable. Hockerts’ ( 2017 ) findings show that prior experience predicts SEI, and that this effect is mediated by the precursors suggested by Mair and Noboa ( 2006 ). His findings also suggest that social entrepreneurial self-efficacy has both the largest impact on intentions as well as being itself most responsive to prior experience. Liang et al. ( 2017 ) conducted two studies to analyse how personality traits, entrepreneurial creativity and social capital affect green socio-entrepreneurial intentions of students in Taiwan and Hong Kong. Their first study was conducted to confirm the factor structures of the scales, namely the five-factor model of personality traits (Thompson, 2008 ), entrepreneurial creativity (Chia & Liang, 2016 ), social capital (Williams, 2006 ) and green socio-entrepreneurial intentions (Wang, Chang, Yao, & Liang, 2016 ). Their second study built predictive models to compare students in Taiwan and Hong Kong. Findings of their first study confirmed the factor structures of the four scales that Liang et al. ( 2017 ) used in their study. Results of their second study revealed that though the effects of predictor variables on the outcome variable were varied, the mediation models of entrepreneurial creativity across contexts were partially supported. Tiwari et al. ( 2017 ) tried to assess the SEI of students in India as influenced by emotional intelligence and self-efficacy. Their results show that their proposed model can explain SEI and that both emotional intelligence and self-efficacy showed positive significant relationship with both attitude and the SEI of students. Huster et al. ( 2017 ) conducted a program evaluation to assess the outcome of students’ participation in a social entrepreneurship competition. This evaluation strongly suggests that social entrepreneurship competitions can contribute to training and educating in multiple and important ways.

Also recently, Radin et al. ( 2017 ) studied SEI and its differences among students and alumni and university categories (e.g. public and private university) in Malaysia. Their results revealed that the level of the SEI of students and alumni was moderate and very similar to each other, and that public university students have a higher potential to become social entrepreneurs as compared to those from private universities. Chipeta and Surujlal ( 2017 ) investigated the influence of attitude, risk taking propensity and proactive personality on SEI of students in South Africa. Their results showed that only risk-taking propensity and attitude towards entrepreneurship were significant, with risk taking propensity being the most significant. Their results also showed that proactive personality did not make a unique contribution to the SEI of students. Kedmenec et al. ( 2017 ) examined the association between social entrepreneurship education and experience in prosocial behaviour on the one hand, and the perceived desirability and feasibility of social entrepreneurship among business students on the other hand. Their results indicate a significant positive association between the “know what” (awareness) component of social entrepreneurship education and both the desirability and the feasibility of social entrepreneurship. Findings of their study also indicate a significant positive association between the “know how” (self-efficacy) component of social entrepreneurship education and the feasibility of social entrepreneurship. Furthermore, they concluded that experience in prosocial behaviour has a significant positive association with both the desirability and the feasibility of social entrepreneurship.

In some of the latest reports, Lacap, Mulyaningsih and Ramadani ( 2018 ) investigated how the SEI antecedents directly and indirectly affect SEI of students in Indonesia and the Philippines. Their results revealed that prior experience with social problems positively and significantly affects empathy, moral obligation, social entrepreneurial self-efficacy and perceived social support. They also found that social entrepreneurial self-efficacy and perceived social support positively and significantly affect SEI, and that these two antecedents mediate the positive relationship between prior experience with social problems and SEI. Aure ( 2018 ) used the studies by Hockerts ( 2017 ) and Mair and Noboa ( 2006 ) to explore the SEI of students in the Philippines. He extended Hockerts’ ( 2017 ) SEI model by examining grit, agreeableness and prior exposure to social action programs as antecedents that he hypothesised to be mediated by empathy, moral obligation, social entrepreneurial self-efficacy and perceived social support. Aure’s ( 2018 ) findings showed that the relationship of SEI with agreeableness are mediated by empathy, self-efficacy and perceived social support. Self-efficacy and social support mediated grit and SEI. Bacq and Alt ( 2018 ) proposed that empathy explains SEI through two complementary mechanisms: self-efficacy (an agentic mechanism) and social worth (a communal mechanism). Their results provided a novel explanation of the mechanisms through which empathy, both cognitive and affective, motivates SEI by building on the prosocial motives literature and on the psychological distinction between individual agency and communal motives. Ip, Liang, Wu, Law and Liu ( 2018 ) proposed a multiple mediation framework to examine the mediating role of entrepreneurial creativity for students in Taiwan and Hong Kong. Results of their study confirmed that prior experience with social problems, perceived social support and originality are the three most influential factors affecting the SEI of students.

Also very recently, Adelekan et al. ( 2018 ) examined the influence of social entrepreneurship pedagogy on the behavioural outcomes of students in Nigeria with regards to their attitudes, intentions and behaviours towards the creation of a social venture. Their results point to a significant positive relationship between social entrepreneurial pedagogy and students behavioural outcomes. Their results show that pedagogical contents exert the greatest influence on the SEI of students. They also found that students’ attitudes mediate the relationship between social entrepreneurial pedagogy and students’ behavioural outcomes. Ip, Wu et al. ( 2018 ) examined whether personality traits, creativity and social capital affect SEI of students in Hong Kong. Their analysis revealed that openness negatively predicted SEI, while originality positively predicted SEI. However, they found no direct association between social capital and SEI. Luc ( 2018 ) developed an integrated model based on the TPB to examine the direct and indirect effect of perceived access to financial resources on SEI. He found no direct relationship between perceived access to financial resources and SEI. Perceived access to financial resources only indirectly increases SEI through attitude towards behaviour and perceived behavioural control. Shahverdi et al. ( 2018 ) used the TPB as a framework to investigate the barriers of SEI of students in Malaysia. Findings of their study show that the lack of competency, self-confidence and resources were the barriers affecting SEI. Their results also show that social entrepreneurial education moderated the relationship between the perceived barriers and the SEI of students. Barton et al. ( 2018 ) investigated the process of content-based and process-based motivational needs influencing the SEI of students in the USA. For the process-based motives, they found that perceived feasibility and perceived desirability to start a social enterprise as well as exposure to entrepreneurship are significant predictors of the SEI of students. In addition, they found that perceived feasibility is determined by entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and perceived desirability is determined by students’ desire for self-realisation and autonomy. For the content-based motives, they found that students are motivated by the need for achievement and independence.

Table 3 summarizes the findings from the tabulation and narrative synthesis above as they help to answer the two research questions.

Limitations of the literature review

The methodology employed in this literature review has strengths and limitations. A strength of the literature review is the use of systematic methods for searching and synthesizing the current literature to answer the research questions. However, the literature review is limited by the key terms and keywords used to retrieve the desired information. Consequently, the authors acknowledge that there might exist very good sources that were not included in the synthesis. The rationale for choosing the key terms and keywords in the search was to identify a deliberate intent on the part of previous authors. That is, the authors wanted to learn from other researchers who deliberately intended to communicate about the influence of the university’s ESS on the SEI of students. Another limitation of the study is that the search strategy was restricted to English language publications. This might have introduced a bias in favour of studies conducted in English-speaking countries and institutions.

The large majority of the studies on SEI of students included in this systematic literature review are based on Ajzen’s ( 1991 ) TPB as modified by Mair and Noboa ( 2006 ) (Aure, 2018 ; Bacq & Alt, 2018 ; Barton et al., 2018 ; Hockerts, 2015 , 2017 ; Ip, Wu, et al., 2018 ; Luc, 2018 ; Moorthy & Annamalah, 2014 ; Politis et al., 2016 ; Tiwari et al., 2017 ). Choosing a career is a decision that requires certain degree of cognitive processing and some amount of planning (Kautonen, van Gelderen, & Tornikoski, 2013 ; Krueger, 2005 ). Becoming self-employed or starting a new business, e.g. a social enterprise, represents a career choice and thus falls under the category of planned behaviour , which is best described and predicted by intention rather than by responses to external stimuli (Davidsson, 1991 ; Katz, 1994 ; Krueger et al., 2000 ; Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 1994 ; Thompson, 2009 ). Intention is the single best predictor of the person’s behaviour and as such, it is a significant and unbiased predictor of career choice (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975 ; Lent et al., 1994 ). Drawing from social and cognitive psychology and based on Ajzen’s ( 1991 ) TPB, Mair and Noboa ( 2006 ) adapted the model of entrepreneurial intention proposed by Krueger and Carsrud ( 1993 ) and Krueger et al. ( 2000 ) and translated it to the context of social entrepreneurship. The TPB is a robust and parsimonious model of behavioural intention with proven power in predicting entrepreneurial behaviour (Kautonen et al., 2013 ; Kautonen, van Gelderen, & Fink, 2015 ; Moriano, Gorgievski, Laguna, Stephan, & Zarafshani, 2012 ). Intention models based on TPB offer a sound theoretical framework that can specifically map out the nature of processes underlying intentional entrepreneurial behaviour (Kim & Hunter, 1993 ; Krueger et al., 2000 ).

Great amount of cross-disciplinary research has been devoted to testing, advancing and criticizing the TPB-based models (Armitage & Conner, 2001 ; Sheeran, 2005 ). The main hypothesis behind the TPB relies on the idea that intention has three conceptually different precursors, i.e. attitude towards the behaviour (ATB), suggestive social norm (SSN) and perceived behavioural control (PBC) (Ajzen, 1991 ; Varamäki et al., 2013 ). In principle, understanding the three precursors of intention should be sufficient to predict behaviour (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2004 ). However, the TPB does allow for the three theoretical precursors to vary greatly in intensity and for them to exert certain degree of influence on each other depending on context (Varamäki et al., 2013 ). In addition, demographics and other characteristics related to the person’s background are not specifically included in the TPB. The TPB expects these factors to have only indirect impact on intention through their influence on the three precursors of intention (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994 ; Kolvereid, 1996b ; Krueger & Carsrud, 1993 ; Lee & Wong, 2004 ; Tubbs & Ekeberg, 1991 ).

Given its robustness, the TPB has become one of the most widely used psychological theories for explaining and predicting human behaviour in general (Kolvereid, 1996b ; Tkachev & Kolvereid, 1999 ; Varamäki et al., 2013 ). The models based on this theory have been successfully used in the entrepreneurial context to predict the specific behaviour of starting a new business (Kautonen et al., 2013 , 2015 ; Kolvereid, 1996a , 1996b ; Krueger & Carsrud, 1993 ). Also, it has been successfully used to assess the entrepreneurial intention of students in very different cultural settings (Autio, Keeley, Klofsten, Parker, & Hay, 2001 ; Devonish, Alleyne, Charles-Soverall, Young Marshall, & Pounder, 2010 ; Fayolle, Gailly, Lassas-Clerc, & Lassas-Clerc, 2006 ; Iakovleva, Kolvereid, & Stephan, 2011 ; Kolvereid, 1996b ; Krueger et al., 2000 ; Krueger & Carsrud, 1993 ; Tkachev & Kolvereid, 1999 ). Findings by previous studies support the claim that all three precursors of intention are important, but not in every situation and not to the same degree (Ajzen, 1991 ; Varamäki et al., 2013 ). Nonetheless, the TPB captures the three precursors of entrepreneurial intention which would indicate the amount of effort that the person will make to carry out the behaviour (Ajzen, 1991 ; Liñán, 2004 ; Liñán & Chen, 2009 ). .

Mair and Noboa ( 2006 ) proposed that, similar to commercial entrepreneurs , social entrepreneurs develop their intention to start a social enterprise after experiencing the perception of feasibility (PBC) and desirability (ATB) and a propensity to act (Shapero & Sokol, 1982 ). Furthermore, they also identified willpower, support and the recognition of opportunity as important precursors of perceptions of feasibility and desirability, and a propensity to act. Moreover, Mair and Noboa ( 2006 ) proposed that social sentiments will influence willpower, support and the recognition of opportunity. Hockerts ( 2015 ) developed and validated measures of four of the constructs identified by Mair and Noboa ( 2006 ) as antecedents of SEI. He redefined the antecedents as empathy with marginalized people, a feeling of moral obligation to help marginalized people, a high level of self-efficacy concerning the ability to effect social change and perceived availability of social support . Hockerts ( 2015 ) was able to demonstrate nomological validity by showing that, as specified by Mair and Noboa ( 2006 ), empathy and moral obligation are positively associated with perceived desirability and self-efficacy, and social support with perceived feasibility of starting a social venture. More recently, Hockerts ( 2017 ) refined his previous work and tested the model of SEI proposed by Mair and Noboa ( 2006 ) and included prior experience with social problems as an additional variable.

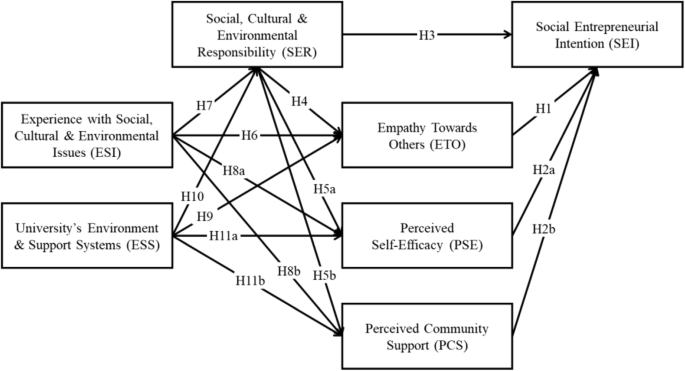

As part of the findings of this systematic literature review and as a way to assess the SEI of students, the authors adopted, adapted and extended Hockerts’ ( 2017 ) work to propose a SEI model for students. The authors are interested in exploring the relative importance of the precursors of SEI as influenced by university’s ESS, i.e. entrepreneurial ecosystem. Thus, they propose the model of SEI depicted in Fig. 1 . This model specifies and describes the governing rules and measurement properties of the observed variables.

Conceptual model of social entrepreneurial intention

In Fig. 1 , empathy towards others (ETO) is a proxy for ATB of the TPB. In the TPB, ATB refers to the degree to which the person has a favourable (or unfavourable) assessment of the behaviour (desirability). For example, a positive attitude towards the behaviour of starting a new business should lead to a stronger intention to go ahead and start a new business (Ajzen, 2001 ; Autio et al., 2001 ; Kolvereid, 1996b ; Krueger et al., 2000 ; Pruett, Shinnar, Toney, Llopis, & Fox, 2009 ; Segal, Borgia, & Schoenfeld, 2005 ; Shapero & Sokol, 1982 ; van Gelderen & Jansen, 2006 ; Varamäki et al., 2013 ). Previous studies have established ATB to be significant and among the most influential constructs in explaining the intention to start a new venture (Bazan et al., 2019 ; Harris & Gibson, 2008 ; Liñán & Chen, 2006 ; Watchravesringkan et al., 2013 ). Empathy has been extensively studied in the context of helping behaviour (Borman, Penner, Allen, & Motowidlo, 2001 ; Oswald, 1996 ). Empathy is an essential trait of social entrepreneurs (Dees, 2012 ) and similar to ATB, it has been regarded as an important antecedent of SEI (Dees, 2012 ; London, 2010 ; Mair & Noboa, 2006 ; Miller et al., 2012 ). ETO as a precursor of SEI is based on the premise that desirability will develop after a person is able to imagine the feelings or mental state of another person in need of compassion (Goetz, Keltner, & Simon-Thomas, 2010 ; Mehrabian & Epstein, 1972 ; Preston et al., 2007 ). It is also based on the premise that individuals with high levels of empathy are more likely to develop intentions to become social entrepreneurs as a way to assist others in need (Bacq & Alt, 2018 ). In Hockerts’ ( 2017 ) work, ETO includes both cognitive empathy and emotional empathy , or the ability to recognize and propensity to react to another person’s emotional state. Thus, the authors formulate the following hypothesis:

H1: Empathy towards others positively influences social entrepreneurial intention.

Perceived self-efficacy (PSE) and perceived community support (PCS) are proxies for PBC in the TPB, i.e. internal and external loci of control . PBC refers to the overall perceived level of ease (or difficulty) of performing the behaviour (feasibility). PBC is concerned with the presence (or absence) of requisite resources and opportunities for performing the behaviour, and how these are perceived to be under the person’s control (Bandura, 1977 ; Bandura, Adams, Hardy, & Howells, 1980 ; Dutton, 1993 ; Krueger & Dickson, 1994 ; Swann, Chang-Schneider, & Larsen McClarty, 2007 ). PBC also connects conceptually and empirically to attribution theory , which was already successfully applied to the study of new venture creation (Krueger et al., 2000 ; Zacharakis, Meyer, & DeCastro, 1999 ). Ajzen ( 2002 ) argued that there is clear and consistent evidence for distinguishing between internal PBC (PSE) and external PBC (PCS). He also argued that there is sufficient commonality between self-efficacy (PSE) and controllability (PCS) to suggest a two-level hierarchical model for PBC. Thus, in Ajzen’s ( 1991 ) TPB, PBC is the overarching, superordinate construct that is comprised of two lower-level components: PSE and PCS.

Drawing from Ajzen’s ( 2002 ) rationale, Mair and Noboa ( 2006 ) and Hockerts ( 2017 ) used self-efficacy and perceived social support as proxies for PBC of the TPB. Self-efficacy is widely considered to be a key antecedent of entrepreneurial intention (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994 ; Bullough, Renko, & Myatt, 2014 ; Fitzsimmons & Douglas, 2011 ; Kickul, Gundry, Barbosa, & Whitcanack, 2009 ; Mcgee, Peterson, Mueller, & Sequeira, 2009 ; Wilson, Kickul, & Marlino, 2007 ; Zhao, Seibert, Hills, & Seibert, 2005 ). Self-efficacy allows a person to perceive the creation of a social venture as a viable behaviour (Ip, Liang et al., 2018 ; Piperopoulos & Dimov, 2015 ). Social support refers to the relationship that social entrepreneurs build with like-minded stakeholders in pursuit of the mission, e.g. social capital (Chan, 2016 ; Estrin, Mickiewicz, & Stephan, 2013 ). Strong PSE and PCS regarding starting a new social business will generally lead to a strong intention to perform the behaviour. PSE and PCS would normally reflect the person’s competencies and past experience as well as the anticipated support (or impediments) and assets (or obstacles) that the person may encounter (Ajzen, 1991 ; Chandler & Jansen, 1992 ). Some researchers have found PBC to be the most important factor in shaping entrepreneurial intention (Arenius & Kovalainen, 2006 ; Souitaris, Zerbinati, & Al-Laham, 2007 ; van Gelderen et al., 2008 ). The authors expect similar relations between the combination of PSE and PCS, and the SEI of students. Thus, the authors formulate the following hypothesis:

H2: Perceived self-efficacy and perceived community support positively influence social entrepreneurial intention.

Social, cultural and environmental responsibility (SER) is a proxy for SSN in the TPB. SSN refers to the perceived social pressure to perform (or not to perform) the behaviour (compliance). Particularly, it is concerned with whether important reference people (family, friends, role models, etc.) approve or disapprove of the person’s behaviour. It is also concerned with the extent that the opinion of reference people matters to the person (Ajzen, 1991 , 2001 ). When the opinion of important reference people matters to the person, the intention to behave accordingly would be stronger if the opinion seems to encourage the behaviour (Cialdini & Trost, 1998 ; Pruett et al., 2009 ). Results in the literature regarding the importance of SSN as an influencer of entrepreneurial intention have been inconsistent (Armitage & Conner, 2001 ; Conner & Armitage, 1998 ; Kautonen et al., 2013 ; Kolvereid & Isaksen, 2006 ; Krueger et al., 2000 ; Lüthje & Franke, 2003 ). Although, it has been shown to exert a strong influence on both ATP and PBC as it was originally alluded in Ajzen’s ( 1991 ) TPB (Autio et al., 2001 ; Kautonen et al., 2013 , 2015 ; Matthews & Moser, 1996 ; Souitaris et al., 2007 ). Several authors have corroborated this argument from the point of view of social capital (Cooper, 1993 ; Liñán & Santos, 2007 ; Matthews & Moser, 1995 ; Scherer, Brodzinski, & Wiebe, 1991 ). Personal moral values and standards have been identified as essential attributes of social entrepreneurs (Bornstein, 2005 ; Chell, Spence, Perrini, & Harris, 2016 ; Hemingway, 2005 ; Koe Hwee Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010 ; Yiu, Wan, Ng, Chen, & Su, 2014 ). Moral beliefs have been found to be important factors of a person’s behaviour (Kaiser, 2006 ; Rivis, Sheeran, & Armitage, 2009 ). Therefore, social entrepreneurs often behave based on their sense of moral values. Mair and Noboa ( 2006 ) called this construct moral judgement and interpreted this sentiment through the lens of ethical principles that appeal to justice, human equality and respect for the dignity of the individual (Kohlberg, 1971 ). Hockerts ( 2017 ) on the other hand, called his construct moral obligation and argued that moral obligation can better measure the extent to which moral judgement will lead to moral intent . That is, moral judgement is a precursor of moral obligation which in turn is a precursor of moral intent (Haines, Street, & Haines, 2008 ). The authors agree with Hockerts’ ( 2017 ) rationale and extend the concept to encompass all sentiments of responsibility and stewardship towards social, cultural and environmental issues. Thus, the authors formulate the following hypotheses:

H3: Social, cultural and environmental responsibility positively influences social entrepreneurial intention. H4: Social, cultural and environmental responsibility positively influences empathy towards others. H5: Social, cultural and environmental responsibility positively influences perceived self-efficacy and perceived community support.

Experience with social issues was identified by Hockerts ( 2017 ) as a predictor of SEI. He argued that past experience such as family exposure (Carr & Sequeira, 2007 ; Chlosta, Patzelt, Klein, & Dormann, 2012 ) and work experience (Kautonen, Luoto, & Tornikoski, 2010 ) have been already identified as one of the predictors of entrepreneurial intention. By the same token, prior experience such as participating in recycle programs, community service and knowledge of social issues have been recognised as predictors of prosocial behaviour—which is always preceded by prosocial intention (Ernst, 2011 ; Miralles, Giones, & Riverola, 2016 ; Vining & Ebreo, 1989 ). For the purpose of this study, the authors adopted the more general construct experience with social, cultural and environmental issues (ESI) as an indirect (distal) antecedent of the SEI of students by affecting the more direct (proximal) precursors of ETO (Batson, Early, & Salvarani, 1997 ; Tukamushaba, Orobia, & George, 2011 ), PSE and PCS (Gist & Mitchell, 1992 ; Tierney & Farmer, 2002 ; Zhao et al., 2005 ) and SER (Coff, 1999 ; Comunian & Gielen, 1995 ; Thøgersen, 2002 ) which act as mediators between ESI and SEI. Thus, the authors formulate the following hypotheses:

H6: Experience with social, cultural and environmental issues positively influences empathy towards others. H7: Experience with social, cultural and environmental issues positively influences social & environmental responsibility. H8: Experience with social, cultural and environmental issues positively influences perceived self-efficacy and perceived community support .

This systematic literature review focused on the influence of the university’s ESS on ETO, PSE, PCS and SER. The university’s ESS corresponds to contextual conditions—exogenous influences or more distal factors—that can affect, similar to ESI, the SEI of students indirectly via their influences on more proximal, motivational factors such as ETO, PSE, PCS and SER (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010 ). This argument is not new. In the past, several authors have conjectured that universities as stakeholders can be one of the most influential factors in encouraging new entrepreneurs (Bacq & Alt, 2018 ; Debackere & Veugelers, 2005 ; Di Gregorio & Shane, 2003 ; Dyer, 2017 ; Henderson & Robertson, 1999 ; Peterman & Kennedy, 2003 ; Robinson, Huefner, & Hunt, 1991 ; Shane, 2004 ; Souitaris et al., 2007 ; Trivedi, 2016 ; Zhao et al., 2005 ). Fewer authors have posited that environmental factors may have an influence on the SEI of students (Moorthy & Annamalah, 2014 ; Politis et al., 2016 ; Salamzadeh et al., 2013 ). However, empirical studies linking external conditions for entrepreneurship and students’ career choices also provided inconsistent results (Schwarz, Wdowiak, Almer-Jarz, & Breitenecker, 2009 ). One explanation for this inconsistency could be that although structural conditions are similar for everyone living in the same context, e.g. the university’s ESS are similar for students attending the same school; the perceptions, attitudes and behaviours might vary from student to student (Turker & Selcuk, 2009 ). Nonetheless, it is reasonable to focus on the social entrepreneurial journey of students as an embedded process in the university context and thus, the university’s ESS could provide an explanation of the relation between personal-related factors and SEI of students (Lüthje & Franke, 2003 ; Schwarz et al., 2009 ).

Notwithstanding some of the comments above, there is also growing evidence that the university context has some influence on the entrepreneurial intention of students (Bae, Qian, Miao, & Fiet, 2014 ; Bazan et al., 2019 ; Kraaijenbrink, Bos, & Groen, 2010 ; Kraaijenbrink & Wijnhoven, 2008 ; Liñán, Urbano, & Guerrero, 2011 ; Sesen, 2013 ; Shirokova, Osiyevskyy, & Bogatyreva, 2016 ; Trivedi, 2016 ; Turker & Selcuk, 2009 ; Zhang, Duysters, & Cloodt, 2014 ). The traditional way in which universities may affect the SEI of students is through the offering of social entrepreneurship education programs. The impact of social entrepreneurship education programs on the precursors of the SEI of students has been the subject of several studies in the past (Adelekan et al., 2018 ; Hockerts, 2017 ; Kedmenec et al., 2017 ; Kwong et al., 2012 ; Piperopoulos & Dimov, 2015 ; Smith & Woodworth, 2012 ; Tshikovhi & Shambare, 2015 ). The investigation of other aspects of the university’s ESS such as business incubation and spin-offs (Chiesa & Piccaluga, 2000 ; Hughes, Ireland, & Morgan, 2007 ; Markuerkiaga, Caiazza, Igartua, & Errasti, 2016 ; Mian, 1996 , 1997 ), technology transfer mechanisms (Bray & Lee, 2000 ; Etzkowitz, 2003 ; Poole & Robertson, 2003 ), university venture funds (Lerner, 2004 ) and mentoring and networking (Nielsen & Lassen, 2012 ) are less common in the literature to date. This systematic literature review attempts to fill that gap by providing a mechanism for researchers to explore this phenomenon. It is clear that elements of the university’s ESS are efficient ways of developing social entrepreneurial competencies of students and motivating them to consider a social entrepreneurial career (Franke & Lüthje, 2004 ; Henderson & Robertson, 1999 ; Kraaijenbrink et al., 2010 ; Peterman & Kennedy, 2003 ). All the precursors of SEI would be affected by ESS, although SER, PSE and PCS seem a priori to be the ones that could be affected by the university’s ESS the most (Shirokova et al., 2016 ). Furthermore, similarly to Trivedi’s ( 2016 ) argument, the authors posit that the university’s ESS is composed of three basic elements: entrepreneurial training (ET), start-up support (SS) and entrepreneurial milieu (EM). Thus, the authors formulate the following hypotheses:

H9: The university’s environment and support system positively influences empathy towards others. H10: The university’s environment and support system positively influences social and environmental responsibility. H11: The university’s environment and support system positively influences perceived self-efficacy and perceived community support .

Table 4 summarizes the hypothesised connections among the constructs of the model. The arrows represent a direct, positive influence of one variable on another variable. A questionnaire operationalizing the proposed SEI model for students is shown in the Appendix .