- New Testament Books In Order (Canonical Order)

Explore the New Testament books in order. This list includes the New Testament Canon of the Bible as it appears in canonical order in modern Bible translations.

New Testament Books In Order

- 1 Corinthians

- 2 Corinthians

- Philippians

- 1 Thessalonians

- 2 Thessalonians

Go Beyond the New Testament In Canonical Order

While this list focused on the New Testament books in order from Matthew to Revelation, there are more ways to view the books of the Bible that make up the New and Old Testament Canons of Scripture. Browse through these additional guides to go beyond the New Testament books in canonical order.

- All Books of the Bible In Order

- Books of the Bible In Alphabetical Order

- Old Testament Books In Order (Canonical Order)

- Old Testament Books In Chronological Order

- Old Testament Books In Alphabetical Order

- New Testament Books In Alphabetical Order

- New Testament Books In Chronological Order

- Chronological Order of the Gospels

Biblevise is an online ministry that’s focused on getting people excited about reading the Bible and connecting the scriptures to their daily lives.

- All Bible Maps

- Heart Messages

- Roman Roads

- Archaeology

The Books of the New Testament

John 14:26 - "But the Counselor, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things, and will remind you of all that I said to you."

The New Testament - A Brief Overview

List of the 27 books of the New Testament in order, with English titles and Greek words and meanings.

Hebrews 8:6 - "But now he has obtained a more excellent ministry, by so much as he is also the mediator of a better covenant, which on better promises has been given as law."

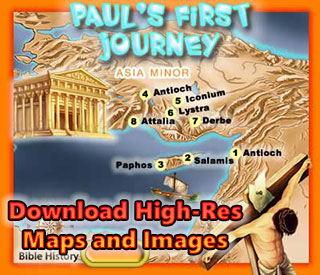

Explore the Bible Like Never Before!

Unearth the rich tapestry of biblical history with our extensive collection of over 1000 meticulously curated Bible Maps and Images . Enhance your understanding of scripture and embark on a journey through the lands and events of the Bible.

- Ancient city layouts

- Historic routes of biblical figures

- Architectural wonders of the Holy Land

- Key moments in biblical history

Start Your Journey Today!

Click here to access our Bible Maps and Images

The Story of the Bible

Summary of the new testament books, table of contents, 1 corinthians, 1 thessalonians, 2 corinthians, 2 thessalonians, 2 timothy is written, acts is written, beginning of john the baptist's ministry, bibliography and credits, colossians is written, destruction of jerusalem, ephesians is written, galatians is written, he visits various places, hebrews is written, i corinthians is written, i peter is written, i thessalonians is written, i timothy is written, ii corinthians is written, ii peter is written, ii thessalonians is written, james is killed by herod, james is written, jesus begins his public ministry, jesus calming the storm, jesus cleanses the temple, jesus leaves galilee for the last time, jesus meets nicodemus, jesus raises jairus' daughter, jesus raises lazarus from the dead, jesus is rejected at samaria, john the baptist's inquiry from prison, john's writings, jude is written, martyrdom of paul, new testament charts, new testament maps, paul reaches rome, paul at caesarea, paul is acquitted, paul's 2d imprisonment at rome, paul's arrest at jerusalem, paul's conversion on the road to damascus, paul's first missionary journey begins, paul's imprisonment at rome, paul's journey to rome, paul's second missionary journey begins, paul's third missionary journey begins, philemon is written, philip at samaria, philippians, philippians is written, romans is written, sea of galilee area in the time of christ, the ascension of jesus, the baptism of jesus, the betrayal by judas, the birth of jesus, the birth of john the baptist, the childhood of jesus, the church is established, the conversion of saul, the council at jerusalem, the crucifixion of jesus, the death of john the baptist, the divisions of herod's kingdom, the feast at bethany, the feeding of the multitudes, the first gentile is converted, the first persecutions of the christians, the founding of the church at antioch, the gospel of luke is written, the gospel of mark is written, the gospel of matthew is written, the holy spirit is poured out, the imprisonment of john the baptist, the last supper with his disciples, the mission of the seventy, the new testament world, the raising of the widow's son, the resurrection of jesus, the sermon on the mount, the temptation of christ, the transfiguration of jesus, the twelve disciples are chosen, timeline of the new testament books, titus is written.

New Testament

Matt—Matthew Mk—Mark Lk—Luke Jn—John Acts—Acts of the Apostles Rom—Romans 1 Cor—1 Corinthians 2 Cor—2 Corinthians Gal—Galatians Eph—Ephesians Phil—Philippians Col—Colossians 1 Thess—1 Thessalonians 2 Thess—2 Thessalonians 1 Tim—1 Timothy 2 Tim—2 Timothy Tit—Titus Phlm—Philemon Heb—Hebrews Jas—James 1 Pet—1 Peter 2 Pet—2 Peter 1 Jn—1 John 2 Jn—2 John 3 Jn—3 John Jude Rev—The Revelation to John (Apocalypse)

NEW TESTAMENT . There are twenty-seven books in the NT, made up of four gospels, the Book of Acts, twenty-one epistles, and the Book of Revelation. (For a detailed account of how these particular books came to be treated as a special collection see Canon of the New Testament .) It is the purpose of this article to give a brief summary of the historical situation out of which the collection of books came into being, a survey of its contents, and a discussion of its authority.

I. Historical background

Foremost in any study of the history of the NT is a consideration of its relationship to the OT. There are two aspects to this consideration: (1) the estimate of the OT found in the NT, and (2) the essential historical and theological link between them. There can be no doubt that the high esteem which the Lord had for the OT was the same among the Jews at that time, involving an acceptance of its full inspiration and authority. This must also have been assumed by the earliest Christian church at Jerusalem, where the members had been drawn from a Jewish milieu. This high regard for the OT exercised a profound influence on the growth of the NT, particularly because the OT immediately assumed importance as the sole Scriptures of the Early Church. This is substantiated by the frequency with which various writers of the NT cite the testimony of the OT, often with formulae of citation which reveal the highest regard for the authority of the OT. Such formulae as “Scripture says,” or “This has come to pass in order that that which has been spoken might be fulfilled,” show the integral relationship between the OT Scriptures and the Christian message. It is against this background that the growth of the NT collection must be traced.

It is a fair assumption that in early Christian worship the reading of the OT occupied a position of prime importance, as it had done in Judaism. It is further safe to say that comments on the OT text giving a Christian interpretation would at once be added, special attention being paid to passages which showed a direct fulfillment in the life of Jesus. Parallel to this development was a deep interest in the teaching of Jesus, which for the Christians possessed authority similar to the pronouncements of the OT. The teachings of Jesus possessed the same authority as Jesus Himself. It was these teachings that the disciples were exhorted to teach to others ( Matt 28:20 ). They could not have done this unless the teachings of Jesus were well stored in their minds.

Parallel to this development was the practice of reading in Christian assemblies letters from apostolic sources. That this practice was common is evident from Paul’s references to his own epistles being read to different communities (cf. Col 4:16 ; 1 Thess 5:27 ). How soon there was a general interchange of and consequent public reading of Paul’s epistles is not known, but a collection of epistles may well have been made within the period soon after Paul’s death (cf. 2 Pet 3:15 , 16 ). Evidence for the early use of these epistles is based mainly on the few extant early subapostolic writings that appear to echo them. While not all the epistles of Paul are cited in these writings, there is sufficient evidence to suggest the existence of an authoritative collection well before the beginning of the 2nd cent.

With the passing of eyewitnesses, and esp. when the apostolic witnesses were no longer available to act as authenticators of doctrine, a pressing need would be felt for the authoritative record, not only of the teaching of Jesus, but also of His deeds. This was prob. an important factor in the production of written gospels. The writing of gospels may have been an independent phenomenon to meet various special needs of the communities. It is certain that, as the Church spread, the need for authoritative lit., particularly the gospels, would become more acute. They would be valuable for evangelistic purposes in areas where no eyewitnesses of the events of the life of Jesus existed. John 20:31 makes the evangelistic purpose clear, at least for the fourth gospel, while the description of all the records as “gospels” designates their purpose as the impartation of good news. It is easy to see that an authoritative character would soon be attached to them. Although it was not until the 2nd cent. that definite evidence of their authoritative and exclusive use in the orthodox Christian Church is forthcoming, the usage is unchallenged in the period from Irenaeus onwards, and so strongly suggested by earlier evidence, that it is certain that the attitude of the churches had much earlier become firmly established. These four gospels stood out from all others as authentic records of the life and teaching of Jesus. It appears from all the extant evidence that as early as the authoritative reception of the gospels, the Book of Acts was also received. This book, which was so closely linked with the gospel of Luke in the tradition, was no doubt received on the same basis as the gospel, of which it appears to be a continuation (cf. the testimony of the late 2nd cent. Muratorian Canon).

In addition to the epistles of Paul, which at least by the mid-2nd cent., and in all probability much earlier, had been collected into the group of thirteen epistles as in the NT, the other NT epistles were gradually included. There is strong early evidence for 1 Peter and 1 John, but it is not known for certain when the other smaller epistles were added to the collection. Some of these are not so readily quotable as the longer epistles, and it is not therefore surprising that definite citations among the early writers are sparse, if present at all. Certainly by the mid-3rd cent., in many parts of the E these minor letters were all included in the NT, but in other parts there was some hesitation over their canonical status. The Book of Revelation was in a similar position, being received as authoritative at an early date in some areas, but being regarded with some hesitancy in others.

When eventually church councils (at Laodicea and Carthage) confirmed the limits of the NT, those limits had long been defined by usage among the great majority of orthodox churches. When the lists approved by these two councils are compared, the only difference was the exclusion of Revelation from the first and its inclusion in the second.

As a collection of Christian books, the NT possesses in itself considerable historical significance. The gospels are practically the only source of information about the historical Jesus. Various schools of NT criticism have suggested doubts concerning the extent to which the gospels preserve genuine information about the historical Jesus ( see article on Jesus Christ ). Since much of the speculation is not based on historical evidence, the gospels still may be regarded as furnishing a considerable amount of information about the historical Jesus, even though it is impossible to reconstruct from them a biography in the modern sense.

Another problem which has been raised over the use of the gospels as historical evidence is the estimate of the historicity of the fourth gospel. This cannot be discussed here, but it is certain that more historical veracity may be attributed to this gospel than many of its critics will allow. In recent years there has been generally a greater readiness to treat its statements as history.

The Book of Acts and the Pauline epistles are the main sources of historical information for the history of the earliest Christian churches, supplemented by the minor epistles. Although there is much more that one would like to know about the methods of procedure within the primitive Christian communities, the NT books contain sufficient data to enable a picture to be drawn, which is adequate for the enunciation of principles. Two books, 1 Peter and Revelation, are particularly valuable as evidence of the way in which the Early Church faced persecution. The Epistle to the Hebrews shows the interplay of Heb. and Hel. ideas, but furnishes little in the way of historical information.

II. Contents

The main concern of this article is to give a general survey of the contents of the NT with the special purpose of showing its essential unity. In spite of the value of the analytical approach, much would be lost if the NT ceased to be regarded as a whole. It is a collection of books of various types, but each part contributes to the unity of the whole.

A. Gospels . The first three of these are known as synoptic gospels because they share a common outline in their main features and because they are distinguished from John. The four books are not biographies of Jesus, although there is some biographical material in them. They are essentially gospels, announcing good news. Their form is unique among the lit. of the contemporary world, because they have a unique purpose, and announce a unique Person. Within their common aim, each has its own point of view, which will be brought out when the separate gospels are considered.

1. Matthew . Of all the gospels this is the most Jewish, as is seen immediately from the opening chs. recording the birth of Jesus. The genealogy is traced from Abraham and is arranged in three groups of fourteen names in typically Jewish fashion. Matthew clearly intended to set forth Christ as a true son of Abraham. There are other features which support this view of the gospel. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus declares that nothing of the law will pass away ( Matt 5:18 f.) which would strongly appeal to Jewish people with their great veneration of the books of the law. Moreover, Jesus did not dispense with the seat of Moses ( Matt 23:2 f.), but urged His followers to observe the Mosaic injunctions as expounded by the scribes and Pharisees, a surprising recommendation in view of the Lord’s condemnation of their hypocrisy. Matthew aims to make clear that Jesus did not conflict with the religious leaders of His day on the score of any different estimates of the law (cf. 19:17 f.; 23:23 for exhortations to fulfill the commandments). Matthew also includes references to Jewish affairs, such as the Temple tax ( 17:24 f.), fasting and sabbath keeping ( 5:23 f.; 6:16 ff.; 24:20 ), the tradition of the elders ( 15:2 ), phylacteries ( 23:5 ), the whitening of sepulchres ( 23:27 ). By this means he shows that Jesus moved in a typically Jewish milieu. One saying of Jesus which throws special light upon this approach is that He states that He has come only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel ( 15:24 ). It is against this specifically Jewish background that Matthew presents Jesus, and the general content of this gospel must be judged accordingly.

It is not unimportant to observe that the gospel is arranged on a pattern of alternating sections of narrative and discourse. This shows something of the intended message of the book. It records a Christ who both acts and speaks. Whereas there is some support for the view that Jesus is portrayed in the dress of a Jewish rabbi, there are some important differences. The rabbis taught traditional material related to and based upon the ancient law, but Jesus brought His own authoritative exposition of the truth. While not denying what Moses had said, He provided His own independent interpretation (cf. the statement, “But I say unto you”), which is esp. seen in the Sermon on the Mount to which Matthew gives such prominence. There is no question that of the synoptic gospels, Matthew presents the clearest picture of Christ as teacher, but this by no means exhausts Matthew’s portrait of Him.

Another important feature of his treatment is the emphasis found on the theme of the kingdom. Most of the parables are specifically described as parables of the kingdom. Jesus undoubtedly thinks of Himself in the role of king. This is in keeping with Matthew’s infancy narrative, in which the child Jesus receives homage from the Magi, and with the account of the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem in a regal manner. The more important aspect of this kingly approach is the incipient Messianism of this gospel. The many occasions when OT passages are claimed to support the actions of Jesus, call attention to the strong emphasis on fulfillment and to the close connection between past predictions and present events. In some cases Matthew treats as Messianic passages which were not so treated by the Jews. In Matthew’s presentation Jesus is not an isolated phenomenon, but the Messiah who would fulfill all the hopes of the past.

In spite of these strong Jewish flavorings, the gospel is by no means exclusively Jewish. The note on which it ends could not be more universalistic. The risen Christ is described not only as commissioning His disciples to go and teach all nations, but also commanding them to teach whatever He has commanded. Although given in a Jewish setting, the teaching of Jesus had a universalistic application.

One feature of Matthew’s gospel which is shared by the other gospels is the large proportion of the book which is devoted to the Passion narrative. The record of activity and teaching which precedes these narratives is essential, but the real center of interest is the Passion of Jesus, for this was the purpose for which He had come.

2. Mark . In its general presentation of the main events Mark’s gospel is similar to that of Matthew. Both begin with the Galilean ministry and trace the events through to the confession of Peter at Caesarea Philippi. From this point both describe the Lord’s steadfastness in setting His face toward Jerusalem, but Mark has his own characteristic features. He is concerned to show Jesus as a man of action. His account contains many vivid instances (e.g. 2:4 ; 4:37 , 38 ; 6:39 ; 7:33 ; 8:23 ; 14:54 ). He uses such connecting words as “immediately” to convey the impression of swiftness of action. He omits much of the teaching of Jesus, and includes only one instance of an extended discourse, i.e. Mark 13 . He differs from Matthew in focusing attention more on acts than on words.

Mark often records instances of Jesus’ description of Himself as Son of man, which fits well into the general picture of Jesus as perfectly human. Much debate has surrounded the meaning of this title, and it is not easy to decide what it meant to the people of Jesus’ own day. Yet, there can be little doubt that for the Lord it had Messianic connotations. He preferred the title because the title of Messiah had become confused on account of the many wrong conceptions of His contemporaries concerning it. Jesus did not come to lead the nation in a political coup. He had come, in Mark’s presentation of Him, to seek and to save the lost by laying down His life in an act of deliverance ( Mark 10:45 ).

Another equally important facet of the presentation of Jesus is the use of the title Son of God, which Mark uses at the beginning of his book. Although the statement is subject to textual variations, the best attested text supports the view that Mark intended writing a gospel about Jesus, the Son of God ( 1:1 ). Although the title cannot be said to be characteristic of this gospel, this aspect of the Lord’s claims is most evident in the powerful acts of Jesus. These are incredible as the acts of a mere man. They require a concept of Jesus which is consonant with supernatural power. Mark’s account, in short, leaves the reader with the impression of a unique person who is at once thoroughly human and yet is possessed of divine powers.

3. Luke . If Matthew’s gospel was designed for Jews, Luke’s portrait of Jesus would appeal to Gentiles. Unlike the other synoptists, Luke addresses his book to an individual, Theophilus, who appears to have been a Gentile of considerable standing. Although the dedication is so specific, there can be no doubt that Luke intended his gospel for a wide audience. Theophilus was more than a man to whom the gospel was dedicated. He prob. stood as representative of all those who were desirous of knowing more fully about the events of the life of Jesus. Luke, moreover, makes his purpose clear in the prologue, where he states that he intends to compile a narrative of the things that have been accomplished among them. Since he also claims to have gone to much trouble to find his data from eyewitnesses and ministers of the Word, it may fairly be deduced that he intended to write history. It was to be history with a theological purpose, in order that Theophilus and others might know the certainty of the things in which they already had been instructed. This clearly defined purpose must be the guiding principle in assessing the specific contribution that Luke’s gospel makes to the total knowledge of the life and work of Jesus.

Luke’s story is fuller than the other synoptics. His birth narratives are more extensive and his conclusion refers to the Ascension, which the other two omit. Many incidents concerning Jesus and a considerable amount of His teaching are preserved only in this gospel. The universal aspect of the work of Jesus is emphasized more. Hints of this broadening outlook are given in the birth narratives. The angelic announcement ( Luke 2:10 ) was for all people, not simply for the Jewish nation. In Simeon’s song ( 2:32 ), Jesus is said to be a light to lighten the Gentiles as well as the glory of Israel. In the citation from Isaiah which is applied to John the Baptist, Luke carries the quotation further than the other synoptics, concluding with the statement that all flesh would see God’s salvation ( 3:6 ). In the concluding commission of the risen Christ, Luke, like Matthew, makes clear that Jesus intended His Gospel to be preached among all nations ( 24:47 ), and the continuation in the Book of Acts shows the beginning of the fulfillment of this command. Moreover, in the gospel itself Luke shows Jesus’ concern for Samaritans as much as for Jews, which illustrates one aspect of His universal approach.

In addition, Luke shows the Lord’s special interest in people. In the parables of Jesus, recorded only by Luke, most find their center of interest in people rather than things. Luke has particular concern to record Jesus’ compassion for social outcasts. The characteristic story of Zacchaeus entertaining Jesus after restitution of goods to those he had wronged illustrates this aspect. The parable of the publican and the Pharisee praying vividly shows where the Lord’s sympathies lay. There is more about His interest in the social position of women in this gospel than in the others, a fact which may be illustrated not only in the number of instances in which women are mentioned in the narratives, but also in the characters appearing in the parables. The same may be said of His concern for children, which is clearly brought out in this gospel. It is, moreover, significant that in the Magnificat Mary points out that it is the hungry who are filled, and the rich who are sent away empty ( Luke 1:53 ); and Luke records several instances which show the Lord’s interest in the underdog.

In the light of these facts it might be supposed that Luke’s main purpose was to portray Jesus as a humanitarian figure who had come to inspire a similar humanitarian approach in man. But this would be a one-sided picture, for Luke, like the other synoptists, has devoted considerable attention to the Passion stories, and his purpose appears to be to show that the Christ who was crucified was the Christ of infinite compassion and human tenderness. Luke does not obscure the fact that Jesus resolutely set His face toward Jerusalem ( 9:51 ). Although some of the Lord’s most gracious acts and words are recorded by Luke after this statement of His set purpose, that purpose was kept in mind throughout. When Jesus hung upon the cross, He uttered a deeply moving cry of dereliction, but Luke does not record this. His account of the Passion may in some respects be described as less tragic than that of the other gospels, but this does not mean that he had any less estimate of its redemptive significance, which is clearly brought out in Luke’s continuation volume, the Book of Acts. The gospel presents what may be called the most human and sensitive account of the doings, teachings, and Passion of Jesus. In spite of the fact that there is much parallel material between the three synoptics, Luke’s picture of Jesus complements their portraits and vindicates the conviction of the Christian Church that all three gospels are essential for a full portrayal of the Lord.

4. John . The marked difference between this gospel and the other three has raised problems concerning its contribution to one’s knowledge of Jesus. For a long time during the history of criticism the historicity of John was disputed. The problem cannot be discussed here, but it should be noted that there is an increasing preparedness to ascribe some elements of historicity to this gospel. An ancient statement by Clement of Alexandria focuses on the problem, for he considered that the other gospels present the corporeal facts, while John presents a spiritual gospel. There is no need to suppose that he thought of John as any less factual, but rather that he understood John’s aim to bring out the spiritual significance of the facts.

Several considerations support this conclusion. When John records miracles, he calls them signs, which reveals his understanding of their purpose to testify to Jesus. Most of the miracles are used as occasions for the recording of discourses based upon them. Thus, the feeding of the five thousand leads into the Bread discourse ( John 6 ), the healing of the blind man into a discussion on the veracity of Jesus’ claims ( ch. 9 ), the raising of Lazarus into statements about resurrection ( ch. 11 ). The first part of the book has been called, with some aptness, the book of signs. The discourses in this portion are of a different kind from those of the synoptics. Here one sees Jesus in frequent dialogue with Jews, sometimes hostile, at other times seriously inquiring as in the case of Nicodemus. The incident with the Samaritan woman shows the breadth of Jesus’ spiritual appeal.

In this gospel the message of Jesus is presented in more abstract forms than in the synoptics, and there is an absence of parables, although there is some parabolic type of material. The teaching is full of metaphorical allusions which show a close relationship to the parabolic form, and there are two allegories—the Shepherd and the sheep, and the Vine. Generally, however, the Johannine teaching material is presented from a different point of view. The great “I am” statements of Jesus bring this into focus. These were selfrevelations of the part that He had come to fulfill. The Bread from heaven, the Light of the world, the Way, the Truth and the Life illustrate His personal assertions.

John provides mankind with knowledge of the Judean ministry of Jesus, which is lacking in the synoptic gospels. Most of the action in his gospel is centered on Jerusalem, which also supplements what is only indirectly hinted at in the synoptics. The portrait of Jesus is therefore seen in a different light. He is introduced as the eternal Logos or Word, without reference to the historical events of His birth. John is content with the bare statement that the Word became flesh. As the story moves on, increasing attention is given to the fact that the “hour” approaches, and this hour is the hour of the crucifixion, which is at the same time the hour of glorification. The Incarnation was the prelude for the fulfilling of a set purpose.

It is in the discourses of John 14-17 that the most characteristic portion of John’s gospel is found. Special attention is given to the work of the Holy Spirit (cf. 14:16 , 17 , 26 ; 15:26 ; 16:7 ; 16:13 , 14 ). In all but the last of these occurrences He is called the Paraclete, or Counselor, who gives assistance, guidance, teaching and reproof. As Jesus faces the imminency of the cross, His final teaching to the disciples is marked by a note of serene joy because He knows that what happens to Him will be for the benefit of His followers. His departure will, in fact, mark the occasion of the coming of the Spirit who will glorify Him.

Jesus’ teaching about His own death is more specific in this gospel than in any other. The statement of John the Baptist that Jesus was the Lamb of God ( John 1:29 ), the saying about the good shepherd laying down His life for the sheep ( 10:14 ff.), and the comparison of Jesus’ death to a kernel of wheat which must die to produce fruit ( 12:24 ) are the clearest indications that the meaning of the cross was not left to conjecture. The cry from the cross, “It is finished” ( 19:30 ), shows the completion of a task which had been foreshadowed in the past and perfectly worked out in Jesus’ life and death. It cannot be too greatly stressed that John’s gospel brings out meanings which are no more than implicit in the synoptic gospels.

B. The Acts of the Apostles . There is an obvious link between the gospels and the Acts, not only because Acts is a continuation of Luke, but also because all of the gospels presuppose some such continuance. Moreover, one of the most striking features about the early chs. of Acts is the evident belief that Jesus is still active among His people. The healing work of Peter and John ( Acts 3 ) is performed in the name of Jesus, and there are other instances of an appeal to His name. Another even more striking feature is the dominance of the work of the Holy Spirit. The book has not inappropriately been called the Acts of the Holy Spirit. The beginning of the evangelistic work of the Church is marked by the descent of the Spirit on the day of Pentecost. Luke is careful to show the indispensable part played by the Spirit in all the developing phases of the Church. Not only is this true of the Jewish mission but also of the Gentile mission. It was by the Spirit that Barnabas and Paul were separated for such work, and by the Spirit that the apostle to the Gentiles was constantly being led, as on the occasion of the second missionary journey when the Spirit forbade Paul’s entry into Bithynia.

The plan of Acts corresponds roughly to the statement in Acts 1:8 , where the risen Lord commands His disciples to witness in Jerusalem, Judaea, Samaria, and in the uttermost part of the earth. The first section of the book shows the development of the Church in the three areas named and the latter part shows the further development as far as the center of the Rom. empire. The history is necessarily selective, but it was undoubtedly part of the aim of the book to describe how Paul’s missionary witness culminated in Rome. In this connection it should be noted that Luke is careful to absolve the various Rom. officials, to whom he refers, from the guilt of hostility to the Church and to Paul. He finds the hostility to be due to Jewish schemes and intrigues.

In this book are preserved several sermons or statements of the Christian message which are invaluable for showing the methods and the content of early preaching. There is no developed theological system. The main burden is testimony to the meaning and achievement of the death and Resurrection of Jesus. This emphasis in the primitive preaching helps to explain the predominant proportion of space given in all the gospels to the Passion and Resurrection narratives. The Christ of the gospels is now seen as the center of the Christian proclamation. Acts lends no support to any view of Christianity which does not place the cross at the core of its message. The primitive church was not built on a new code of ethics, not even on the ethical teaching of Jesus. It was essentially a redeemed community, as the Book of Acts makes clear.

At the same time, the book furnishes some useful information about the life of the primitive communities, although what insights are given need to be supplemented by the epistles of Paul. One of the major contributions which the book makes is the account of the gathering of the apostles, elders and members of the Church at Jerusalem, to discuss the question of circumcision in relation to Paul’s work. This provides a glimpse of early Christian procedure. It also forms a close point of contact with the epistles of Paul, since he was implicated in this important issue.

Acts is therefore the link between the gospels and epistles. While much can be deduced about the apostle from his self-revelation in his epistles, it is the Book of Acts which provides the background against which the epistles must be studied.

C. The epistles of Paul . For the purpose of drawing out the major emphases in each epistle it is necessary to explain which epistles are being included. All the epistles which claim to be written by Paul will be considered in this context (i.e. thirteen epistles). The present writer does not consider that there are adequate grounds for disputing the true Pauline character of any of these. The epistle to the Hebrews will be considered separately. Although some changes of emphasis may be traced within the collection of Paul’s letters, yet there is found a remarkable unity of theological outlook.

1. Romans . This is the most theological of all Paul’s epistles. The predominant theme is righteousness and the method of attaining it. The apostle shows that all men, whether Gentile or Jew, have the same basic need for justification, and no one is exempt from that need. Justification can be secured only through faith in Christ, for God has provided Him as a propitiation for man’s sins ( Rom 3:26 ). God’s provision is a direct linkup with the death of Christ in the gospels. This epistle proceeds to show that Abraham illustrates the faith principle, and since Abraham preceded the law, justification could not depend upon allegiance to the law. Various principles of the life of faith are then enunciated, e.g., grace does not mean that sin can abound, the realization that in the inner struggle it is Christ alone who can give the victory, and that in the Christian life there is an imperative need for the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. Romans 1-8 is a closely reasoned entity. This is followed by a discussion of the problem of Israel and its relation to the Gentiles within the context of the Christian Church. The connection with the foregoing part of the epistle is not at once apparent, yet the Jewish-Gentile issue essentially concerned the problem of righteousness. The real question was: How could a God who had rejected Israel be righteous? Paul maintains that Israel will be restored to its rightful place, but on different grounds from the popular expectation. It could take place only according to the mercy and inscrutable wisdom of God ( Rom 11:33 ff.). The epistle concludes with practical exhortations which show the outworking of righteousness in the believer. This is typical of the way in which Paul links doctrine with practice.

2. The Corinthian epistles . Paul had somewhat checkered relationships with the Corinthian Christians, and his two epistles to them reflect a number of practical difficulties which had arisen. These epistles provide a valuable insight into Paul’s methods of dealing with such problems, and supply a pattern which has proved indispensable in the subsequent history of the Church. Probably the church at Corinth was not typical in Paul’s own time, but his enunciation of principles has proved to be timeless.

In the first epistle Paul deals with a variety of issues. He devotes most space to the factions which had arisen and which he deplores. He next proceeds to condemn the condoning of a case of incest and Christians appealing to heathen law courts to settle disputes. Following this he discusses marriage relationships, meat offered to idols, the behavior of women during Christian worship, spiritual gifts, and the resurrection from the dead. No one thread runs through this letter. What binds it into a unity is the urgency of the need to understand the Christian principles which must determine the approach to a variety of practical issues, many of which arose from the pagan background of the church members. The letter contains little theology, but the ethical principles are fully consonant with the theology expressed in such an epistle as Romans. The exquisite hymn of love in ch. thirteen is based on a higher than human love, the love of God, which figures prominently in the Roman epistle.

The second letter presents many problems to the exegete. It is the most difficult of all Paul’s epistles. Its occasion is connected with his personal relationship with the Corinthians. Matters had come to a head and a group had arisen within the church which was violently opposed to Paul. The epistle is in response to a report from Titus, who was able to assure the apostle that the condition of the church was not as serious as it had previously been. The apostle still found it necessary to take to task a portion of the church in the closing chs. ( 10-13 ), in which he strongly defends his own position, but the rest of the epistle breathes the spirit of relief. Paul has much to say about the nature of the Christian ministry in a discussion which has become basic for the Christian Church as a whole. Moreover, he includes a discussion on the Corinthians’ obligation to contribute to the collection scheme for the poverty-stricken believers in Judea, which illustrates the intensely practical and social concern of the great apostle.

3. Galatians . This epistle has special historical importance because of the light it throws on the problem of circumcision in the primitive Church. Jewish Christians tended to regard circumcision as an essential part of salvation, and since that was so it was necessary for Gentiles also to be circumcised. Some ardent advocates of this point of view had attempted to persuade the Gentiles to follow their line, and Paul’s letter is designed to combat this approach, which he does along two lines. He first establishes the validity of his apostleship, since the Jewish party were denying this. The more important part of the rebuttal is the doctrinal section, in which he emphatically denies that works of the law have anything to do with justification, which is entirely a matter of faith. The argument is similar to that in the Roman epistle. In both, Paul appeals to the position of Abraham, which weighed heavily with him. One interesting feature in Galatians is the use of allegory, which he does not use much elsewhere (cf. Gal 4:21 ff.). As in Romans, so here, the epistle closes with practical exhortations, the highlights of which are the appeal to the readers to show forth the fruit of the Spirit ( 5:22 ), and his own determination to boast only in the cross ( 6:14 ).

4. Ephesians . This epistle with Colossians, Philippians, and Philemon are known as the Prison Epistles, for in all of them Paul reveals that he is a prisoner. In the first part of the epistle Paul dwells on the mystery of God’s dealings with men and introduces a high view of Christ. He stresses that Christianity is a matter of faith and not works. He sees the Jewish-Gentile problem resolved in the death of Christ. The latter part of the epistle is devoted to Christian behavior, and once again the close relation between doctrine and practice is noticeably maintained.

5. Philippians . The major note in this epistle is Christian joy. The most notable portion is the Christological passage ( Phil 2:5 ff.), where Paul speaks of the condescension of Christ. Theology is used as a basis for an exhortation to the Christians to have the same mind as Christ. The letter reveals much of Paul’s affection for the readers and of theirs for him.

6. Colossians . There is much similarity between Colossians and Ephesians, but the former is tied to a specific situation, for Paul deals with a heresy. In answer to it he stresses the positive pre-eminence of Christ. He maintains that Christ’s reconciliation extends to the material creation, which shows Paul’s view of the world as essentially Christocentric. The ethical section runs closely parallel to Ephesians.

7. The Thessalonian epistles . These were almost certainly the earliest of Paul’s letters. In both he is mainly concerned with eschatology. There were problems concerning believers who had already died; the Christians wondered what their part would be at the Second Coming of Christ. There were others who thought the coming of the Lord to be so imminent that they ceased to work. The first epistle deals specifically with the first problem, and the second introduces strong caution about the second situation. Both epistles are notable for their practical teaching.

8. The Pastorals . This group comprises 1 and 2 Timothy and Titus. These epistles show Paul’s concern for orderly arrangement within the Church. He mentions the qualifications necessary for office bearers and gives advice about the treatment of false teachers who were active in the churches of Ephesus and Crete. Second Timothy is of special interest as Paul’s last epistle.

9. Philemon . Although brief, this is an exquisite example of Christian tact, as Paul is seen pleading for the restoration of the runaway slave Onesimus. While the apostle does not explicity condemn slavery, his approach was destined ultimately to overthrow it.

D. Other NT epistles

1. Hebrews. The background of this epistle is the priestly system of the OT, and Christ is portrayed against this background. Aaron’s order had failed because both priests and offerings were imperfect. Since Christ, both in His person and His offering, was perfect, the old order has ceased to have relevance. Such an exposition would have special interest for Jews, but was also valuable in enabling the Gentiles to understand the Christian approach to the OT. This epistle provides valuable instruction of the lines along which a Christian interpretation of the OT should proceed. The readers appear to have been on the point of apostatizing, and so the writer presents something of the glory of the Christian position.

2. James . This deals almost wholly with practical issues, such as temptation, prayer, control of the tongue and wealth. It is remarkable for the lack of doctrinal content, which seems to be assumed. The best-known passage is the section on faith and works ( James 2:14 ff.), which often has erroneously been supposed to conflict with Paul. But James is concerned that faith should work, and Paul that faith should not depend on works of the law (i.e. a legal system).

3. The Petrine epistles . The first of these was written against a background of persecution and its purpose is to encourage the readers. The basis of encouragement is the example of Christ, esp. His sufferings. There is a combination of the theological and practical significance of the cross. There is also a strong influence of the OT, particularly in allusions to the Exodus. The epistle is of special value for suffering Christian communities in any age.

In the second letter the main burden is the activity of certain false teachers whose policies lead to moral deterioration. Peter gives an outline of the nature of the false teaching, and then stresses the Holy Spirit’s part in the production of true prophecy ( 2 Peter 1:20 , 21 ). At the close of the epistle attention is given to the problem of the delay of the Second Coming of Christ, at which some were scoffing. There are solemn words about the coming day of the Lord.

4. The Johannine epistles . All three of these epistles dwell on the theme of truth, which reflects a background of controversy and error. From 1 and 2 John it seems certain that the error was Docetism, which distinguished between the heavenly Christ and the human Jesus. John’s answer is twofold—a right relationship with God in Christ and a life dominated by love. There are many antitheses. Light is contrasted with darkness, truth with error, the life of faith with the world. Sin comes into sharp focus and the efficacy of Christ’s offering in dealing with it. Second John cautions against the entertainment of false teachers, and 3 John criticizes a church for refusing to entertain the messengers of God.

5. Jude . This brief letter, warning against false teachers of a similar type as those referred to in 2 Peter, is significant for its ending, which exalts the love and keeping power of God.

E. The Book of Revelation . This book has given rise to numerous interpretations, over which there has been much dispute. All would acknowledge, however, that the overall theme is Christ’s ultimate victory over the powers of evil. Whether its symbolism is to be interpreted historically or prophetically, the message of encouragement to hard-pressed believers remains unaffected. It is a vision directed to seven churches of Asia, but it has an abiding message in focusing attention on the victorious consummation of the Christian era. The slain Lamb has become the enthroned Lamb. Without this book the NT would have been incomplete.

This survey of the separate books has shown a wide variety of facets, but they form a unity. There is one Christian message, although it comes through many channels.

III. The authority of the NT

It is impossible here to discuss the nature of religious authority. All that will be attempted is to give some reasons why the NT has come to be authoritative in the life and ministry of the Church. First, it must be recognized that the NT is the only authoritative source which can demonstrate the historical basis of Christianity. Differing opinions exist among different schools of criticism as to the authority of the books for this purpose. Where the authenticity of any of the books is challenged, its value as a historical source immediately becomes suspect. But orthodox Christianity has never doubted that the NT provides a reliable guide to the historical development of the Christian Church.

It is, however, preeminently in the field of doctrine and conduct that its authority lies. The Apostle Paul writes in such a way as to command his readers, and the authority of his approach has been recognized within the Christian Church. His doctrine accordingly has been invested with authority. It is because the apostle knows himself to be led of the Spirit of God that he can write so authoritatively. The tone of the epistles of the other NT writers is equally commanding. It is in the gospels, however, that this note of authority is less conspicuous in the writers, because of the different character of the writings. Whereas in the epistles men speak authoritatively under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, in the gospels the authority rests directly on the authority of Jesus Himself. What He says and does carries with it its own authority, which is nothing short of the authority of God Himself. He speaks and acts in harmony with the will of the Father.

The question arises why the NT books alone of all the lit. in the Early Church came to be regarded as authoritative. The answer is linked with the study of canonicity, which is discussed in the article on the Canon of the New Testament . Yet, some comment must be made here on the manner in which authority came to be attributed to the twenty-seven books comprising the NT. As mentioned in the opening section of this article, both the Lord and the apostles accepted the authority of the OT. Where the testimony of the OT supported a statement or illustrated an event, it added a dimension which could not be ignored. It was the firm conviction of Christ and the apostles that the OT Scriptures could not be broken. It was the Word of God, and therefore the voice of God. Men had been borne along by the Holy Spirit to write it. Its commands were accepted without question as the commands of God. But did the same apply to the NT?

It may be assumed that the authority which belonged to the OT would become transferred to the NT, as soon as the teaching of Jesus and His apostles was recognized as a logical sequence to the teaching of the OT. It is this conviction of the essential continuity between the old order and the new that paved the way for an extension of authority to those books which bore witness to that continuity. With this in mind, it is not difficult to see how the accounts of the ministry and teaching of Jesus would at once have become authoritative. Why, then, were four such accounts chosen?

It is essential to note that none of the gospels had an authority imposed upon it from without. Each possessed an inherent authority which was recognized by the earliest recipients. Further, it was recognized that the apostles had not only been appointed by the Lord, but also had been promised by Him the special guidance of the Holy Spirit ( John 14:26 ), and their words therefore became invested with special authority. The Apostle Paul repeatedly claimed to be on an equal footing with the Jerusalem apostles by his claim to the apostolic office, and it must be supposed that the Christian churches as a whole came to recognize that authority. His epistles were clearly so regarded when 2 Peter 3:15 , 16 was written.

The main problem rests with the remaining books. With the exception of 1 Peter and 1 John there was some delay in their universal acceptance. During the earliest period there is little evidence of the attitude toward the other minor epistles. They are not the kind of letters that would be much quoted, and since all the earliest evidence consists of patristic quotations, it is difficult to know what these authors thought of the books which they did not quote. In some cases there is evidence that doubts existed, but there is no knowledge of the basis of these doubts. The Book of Revelation was more highly esteemed in the E than in the W, but the hesitation over its acceptance may have been due to difficulties of interpretation. When eventually all the books were equally acknowledged, it was not through any ecclesiastical pronouncement, but through the long usage and esteem of the Christian Church as a whole. The books were acknowledged as an authoritative unity.

Bibliography A. Nairne, The Faith of the NT (1920); H. N. Bate, A Guide to the Epistles of St. Paul (1926); F. F. Bruce, Are the NT Documents Reliable? (1943); A. M. Hunter, The Unity of the NT (1946); W. G. Scroggie, A Guide to the Gospels (1948); F. V. Filson, The NT Against its Environment (1950); R. M. Grant, An Introduction to NT Thought (1950); J. L. Price, Interpreting the NT (1961); M. C. Tenney, NT Survey, A Historical and Analytical Survey , 2nd ed. (1961); W. C. van Unnik, The New Testament (1962); R. M. Grant, A Historical Introduction to the NT (1963); F. V. Filson, A NT History (1964); E. F. Harrison, NT Introduction (1964); B. M. Metzger, The NT, its Background, Growth, and Content (1965); P. Feine—J. Behm—W. G. Kümmel, Introduction to the NT (1966); G. W. Barker, W. L. Lane, J. R. Michols, The New Testament Speaks (1969); D. Guthrie, NT Introduction (1 vol., 1970); R. H. Gundry, A Survey of the New Testament (1970).

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

New Testament Books In Order. Matthew. Mark. Luke. John. Acts. Romans. 1 Corinthians. 2 Corinthians. Galatians. Ephesians. Philippians. Colossians. 1 Thessalonians. 2 Thessalonians. 1 Timothy. 2 Timothy. Titus. Philemon. Hebrews. James. 1 Peter. 2 Peter. 1 John. 2 John. 3 John. Jude. Revelation. Go Beyond the New Testament In Canonical Order.

The New Testament contains 27 different books written by nine different authors. Every author of the New Testament was Jewish except for Luke. Three of the writers: Matthew, Peter, and John were among the 12 disciples who walked with Christ during his earthly ministry.

The New Testament is a record of historical events, the ‘good news’ events of the saving life of the Lord Jesus Christ—His life, death, resurrection, ascension, and the continuation of His work in the world—which is explained and applied by the apostles whom He chose and sent into the world.

There are twenty-seven books in the NT, made up of four gospels, the Book of Acts, twenty-one epistles, and the Book of Revelation. (For a detailed account of how these particular books came to be treated as a special collection see Canon of the New Testament .)

Biblical literature - New Testament, Canon, Versions: The New Testament consists of 27 books, which are the residue, or precipitate, out of many 1st–2nd-century-ce writings that Christian groups considered sacred.