Have an account?

Suggestions for you See more

Subject and Predicate

Punctuation, 14.3k plays, 7th - 9th , 16.3k plays, 1st - 3rd , 3rd - 4th .

Sentence Fragments

20 questions

Introducing new Paper mode

No student devices needed. Know more

Which is a complete sentence?

Malia always enchants audiences with the raw emotion in her performances.

Shawna already leaving to catch the plane for her week-long cruise to Puerto Vallarta.

More than fifty reviews of the new video game console.

For breakfast, this restaurant serves eggs with biscuits and gravy.

Which is a sentence fragment?

Our ice hockey team mascot, a grizzly bear.

Dalton and Wendy both handle themselves well under pressure.

After the trial, new evidence emerged about the case.

Ted going to the movies later this evening.

Mrs. Vincent carefully buttoned up her coat.

complete sentence

sentence fragment

Marie fulfilling her dream of hiking to the top of Mount St. Helens.

In August 2012, the Curiosity rover landed on Mars.

A long pleated skirt with a floral print.

In Japan, the Hanshin Expressway actually runs through a building!

Sometimes feels nervous and uncomfortable when speaking in front of large groups.

Brad performing onstage for the thrill of the audience’s cheers and applause.

missing a subject

missing a verb / predicate

missing a helping verb

The reporter writing an article with questionable sources.

Are dry after such a severe drought.

My parents’ business flourishing, thanks to online advertising.

Started making his own yogurt and cheese after inheriting a small dairy farm.

Explore all questions with a free account

Continue with email

Continue with phone

University Libraries

News literacy & alternative facts: how to be a responsible information consumer, tools for verification, things to consider, additional tips, evaluating a report, created by:.

- Finding Reliable Information

- Further Resources

- Need More Help?

Click on the black arrow to open the chat in a new window. If we're not online, please email us at [email protected]. Please allow 1-2 business days for a response.

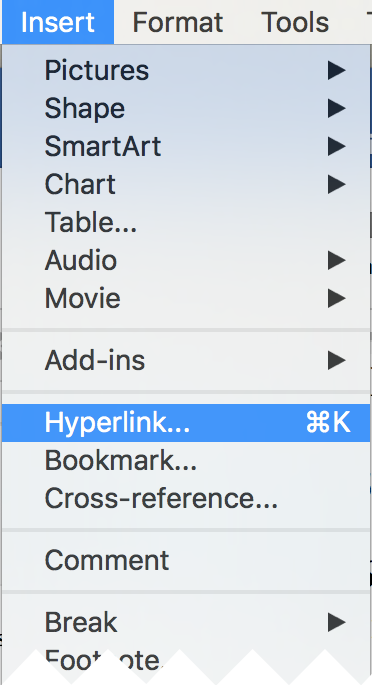

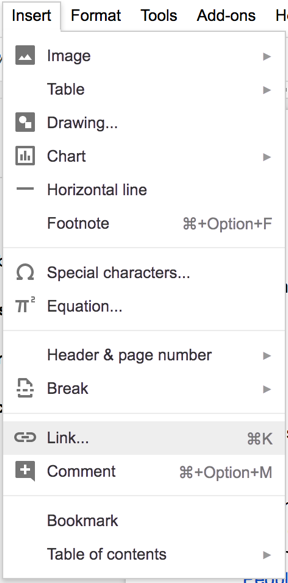

Looking for some basic tools to help you verify, cross-check, and compare content you see online to avoid spreading fake news? Here are a few basic open access resources to get you started:

Fact Checkers

- Factcheck.org FactCheck.org fact-checks claims made by presidents, members of Congress, presidential candidates, and other members of the political arena by reviewing TV ads, debates, speeches, interviews, and news releases.

- PolitiFact: Fact-checking US politics Politifact fact-checks claims by politicians at the federal, state, and local level, as well as political parties, PACs, and advocacy groups and ates the accuracy of these claims on its Truth-O-Meter.

- Snopes Snopes.com was originally founded to uncover rumors that had begun cropping up in chain emails and message boards and is now highly regarded for its fact-checking.

- Verification Handbook: An ultimate guideline on digital age sourcing Handbook is a step by step guide for verifying digital content initially created for reporters and emergency responders.

Verify Webpage History

- Internet Wayback Machine Web archive that captures websites over time and can be used to verify content history and edits.

Check Author's Credentials

- LinkedIn A professional networking website where you can look up the authors of articles and books to see if they're credible.

Verify Images

Found an image you think may have been manipulated or photo-shopped? Use these tools to check for any digital changes:

- FotoForensics Identify parts of an image that may have been modified or photoshopped.

- Google Reverse Image Search Upload or use a URL image to check the content history or to see similar images on the web.

- Google Street View Identifying the location of a suspicious photo or video is a crucial part of the verification process.

- TinEye Reverse Image Search Upload or enter an image URL to the search bar and see a list of related sites. Has plug-ins for your browser.

- Wikimapia Crowd-sourced version of Google Maps, featuring additional information.

Source: William H. Hannon Library. (2017). Tools for verifying. http://libguides.lmu.edu/c.php?g=595781&p=4121899

Source: IFLA. (2017). How to spot fake news [Online image]. http://blogs.ifla.org/lpa/2017/01/27/alternative-facts-and-fake-news-verifiability-in-the-information-society/

Source: WNYC. (2013). Breaking news consumer's handbook: Fake news edition [Online image]. http://www.wnyc.org/story/breaking-news-consumers-handbook-pdf/

Online tools can be helpful, but nothing is more important than developing your own ability to think critically about news and information sources. Still unsure of what questions you should ask when evaluating a news report? The Indiana University East Campus Library has provided an excellent example of how to evaluate a news claim from an online source. In the example below, see how the IUE Campus Library evaluated a claim that the earth is hollow.

Source: Indiana University East Campus Library. (2017). Let's check a claim. http://iue.libguides.com/fakenews/claim

Alicia Vaandering, 2/2017

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Finding Reliable Information >>

- Last Updated: Oct 1, 2023 5:00 PM

- URL: https://uri.libguides.com/newsliteracy

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

How to gauge the quality of a research study: 13 questions journalists should ask

Asking these questions can help journalists gauge the quality of a research study or report and avoid relying on flawed findings.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Denise-Marie Ordway, The Journalist's Resource March 21, 2017

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/media/good-research-bad-quality-journalism-tips/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

Academic research is one of journalists’ best tools for covering public policy issues. It’s also a tool that takes skill to use.

Experienced journalists use research to ground their work and fact-check claims made by politicians, policymakers and others. Many journalists, however, are not trained in research methods and statistical analysis. Some have difficulty differentiating between a quality study and a questionable one.

Journalist’s Resource has put together a list of questions reporters should ask when selecting studies to guide their coverage. While there is no way to guarantee the quality of a study, these questions can help journalists avoid biased or otherwise flawed research.

It’s important to note that many of these questions apply primarily to quantitative research, or research in social sciences and natural sciences that involves the analysis of data.

- Is this research peer reviewed? A study published in a peer-reviewed journal typically undergoes a detailed critique by a small number of qualified scholars. The peer-review process, while imperfect, is designed for quality control.

- Is it published in a top-tier academic journal? Top journals are more likely to feature high-quality research. They are more selective about the research they accept for publication. Also, their peer-review process tends to be more rigorous. A measure for gauging a journal’s ranking is its Impact Factor, which can be found in the Journal Citation Reports database . Impact Factor scores range from zero to over 100.

- Do other scholars trust this work? One indicator of whether other scholars consider a study to be credible is the number of times they cite it in their own research. It can take years, however, for a study to generate a high citation count. You can use Google Scholar , a free search engine, or Web of Science , a subscription-based service, to find citation counts. Journalists also can ask faculty in the field their opinions.

- Who funded the research? It’s important to know who sponsored the research and what role, if any, a sponsor played in the design of the study and its implementation or in decisions about how findings would be presented to the public. Authors of studies published in academic journals are required to disclose funding sources. Studies funded by organizations such as the National Science Foundation tend to be trustworthy because the funding process itself is subject to an exhaustive peer-review process.

- What are the authors’ credentials? Knowing where the authors work and how often they have been published can help you assess their expertise in a field of study.

- How old is the study? In certain fields — for example, chemistry or public opinion — a study that is several years old may no longer be reliable.

- Do the authors have a conflict of interest? Be leery of research conducted by individuals or organizations that stand to gain from the findings.

- What’s the sample size? For studies based on samples, larger samples generally yield more accurate results than smaller samples.

- Does the study rely on survey results? Survey results can be biased if respondents were not chosen by random selection. Beware of any survey that relies on respondents who self-select (for example, many internet-based surveys).

- Can you follow the methodology? Scholars should explain how they approached their research questions, where they got their data and how they used it. They also should clearly define key concepts and describe the statistical methods used in their analyses. This level of detail is necessary to allow other people to check and replicate their work. Replicability is critical.

- Is statistical data presented? Authors should present details about the data they are examining and the numerical results of their analyses. This allows others to review their calculations. In some fields, authors make their data sets publicly available.

- Are the study’s findings supported by the data? Good researchers are very cautious in describing their conclusions – because they want to convey exactly what they learned. Sometimes, however, researchers might exaggerate or minimize their findings or there will be a discrepancy between what an author claims to have found and what the data suggests.

- Is it a meta-study? Among the most reliable studies are meta-studies, also referred to as meta-analyses. Their conclusions are based on an analysis of multiple studies done on a particular topic.

Journalist’s Resource would like to thank these scholars for their help in creating this tip sheet: Adam J. Berinsky, professor of political science at MIT; Marybeth Gasman, professor of higher education at the University of Pennsylvania; Morgan L. W. Hazelton, assistant professor of political science at Saint Louis University; Thomas E. Patterson, professor of government and the press at Harvard University; Eric A. Stewart, professor of criminology at Florida State University.

About The Author

Denise-Marie Ordway

- ONA23 Conference

- Online Journalism Awards

- Ethics Tool

- Knowledge Base

- ONA Insights

- Member Log In

See all topics

Confidential sources

- What does an “anonymous source” mean?

- On what basis should we grant confidentiality to a source?

- What understandings should you have when granting confidentiality?

- What if a spokesperson doesn’t want to be identified?

Should you take part in background briefings?

- How can you protect confidentiality if you or the source might be subject to electronic surveillance?

Use of confidential sources is an area where many news organizations’ policies and practices don’t necessarily match up. Many news organizations have policies that say they rarely use confidential sources, but in practice they frequently use them. Whether you favor using confidential sources heavily because of the tips and information people will provide if you don’t name them, or whether you favor seldom or never using confidential sources, because you don’t consider them credible, top editors in any news organization should discuss their standards with their staffs and try to achieve consistency in how and why you grant confidentiality.

Terminology

Often among journalists and especially among our critics, the term for sources we don’t name is “anonymous sources,” or we explain in a story that the source requested “anonymity.” But this term can be misleading or even inaccurate in ways that undercut the news organization’s credibility. The truth is that few, if any, news stories ever actually use any information from truly anonymous sources: people whose identities are unknown to the journalists or the news organization.

Truly anonymous sources would be people who call us on the telephone with tips and refuse to give their names, anonymous commenters on our websites or someone contacting us through email or social media (or even in person) who refuse to identify themselves to us. Journalists get valuable tips in these ways but shouldn’t publish anything based on these sources. If you publish a story at all, you should use the tip as a starting point and find sources you trust — whether they will go on the record or not — on which to base a story.

This may appear a matter of semantics, but anything involving unnamed sources affects the credibility of your stories. And every tiny step you can take to assure the reader or viewer that you have tried to use reliable sources is important. Using terms such as “confidential” sources probably doesn’t build much confidence, but the word “anonymous” or “anonymity” can hurt your credibility, and isn’t accurate from your standpoint. So consider avoiding those terms.

Journalists using unnamed sources usually know the sources well. If they are not sources you have used before, you should question them extensively about how they know what they are telling you and why they can’t go on the record. You might research their credentials to judge their veracity. Because of your pledge of confidentiality, you generally can’t vet sources by asking others about their credibility, but sometimes a confidential source can put you in touch with a trusted contact of yours who can vouch for her credibility. Sometimes a source you trust leads you to a good source that insists on remaining confidential.

Steve Buttry discussed this issue at greater length in his blog post “You didn’t hear this from me…”

When to grant confidentiality

Here are other factors to consider when determining whether to grant confidentiality and how to handle such requests:

What is the source’s reason for wanting not to be identified?

Paul Farhi of the Washington Post wrote a story in 2013 about the weak explanations news reports give of sources’ reasons for not being identified.

Before a journalist grants confidentiality, you should have a detailed discussion of the source’s reasons for wanting to avoid accountability, which is what happens when you don’t name sources. Tell the source that your stories are more credible and your sources more accountable when you use their names and gain a thorough understanding of the source’s motivation.

Sometimes this discussion reveals that the source isn’t confident enough in what he is saying to stand behind it. You need to know that. Maybe the source isn’t sharing first-hand information. In that case, you need to ask the source to help you get to the original source. You can build credibility with the source by saying that you don’t use second-hand sources, and ask this person’s help in identifying and/or reaching the original source.

If the source’s reason for wanting anonymity sounds weak, push back on the source and see whether you can talk her into going on the record. Be willing to walk away from a source whose reason is so poor that you doubt the source’s credibility.

Is the information available elsewhere?

Ask the source who else might have the information or whether documentation exists. If the source can give you the documentation, you never have to name the source or use an unnamed source, just cite the documents.

If someone else has the information, try that person to see if she will speak for the record.

If a person is the only source for a piece of information, you might have a stronger reason to grant confidentiality.

You may wish to write, when quoting unnamed sources, that the person “insisted” on not being named. Saying that, rather than “requested not to be named,” emphasizes that you do not grant anonymity easily. It makes clear that if you had not granted confidentiality, you would not have the information.

What information is the source providing?

The more important the information is, the more willing a journalist will normally be to make a deal. If the information doesn’t seem very important, consider taking one of two approaches:

Tell the source you don’t want to talk unless it’s on the record. Tell the source you’d like to hear the information for background purposes but you’re not likely to use it without a name. It might help you understand the issue better or lead you to another source.

You can’t always get a good idea before granting confidentiality about what the information is. Sometimes you can opt for the first option during the interview, saying that if this is as good as it gets, you don’t want to continue talking off the record. It’s more likely in this case that you will end up going to the second option, thanking the source but saying you’re not likely to use this information unless you can attribute it by name.

Is the source dishing opinion?

Information from unnamed sources has some value if they are telling the truth. If a source gives you information, you can seek documentation or verification from other sources. You can describe how the source knows the information, giving credibility to the information.

But the value of an opinion is entirely dependent on the person holding the opinion. A person who criticizes others and won’t stand behind the opinions with his name is a coward, and journalists shouldn’t honor those opinions by publishing them.

Steve Buttry addressed this issue at greater length in a 2005 blog post “Unnamed sources should have unpublished opinions.”

Is the source eager or reluctant?

You should be more willing to grant confidentiality to a source you approach but is reluctant to talk than to a source who approaches you with information he hopes you’ll publish.

When you initiate the conversation, you are trying to persuade the source to help you with your story. Confidentiality is a technique you can use to start the conversation. You may already understand why the source is reluctant to be identified. You may be able to talk the person into going on the record about some or all of the interview if you use confidentiality to start the conversation and then get time to build some trust.

But when a source approaches you with a tip and wants to stay unnamed, it may be that you’re being played. In many cases, the source who approaches you isn’t the real source, but a pawn. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t grant confidentiality. The source might give you important information that you can verify elsewhere. One approach when dealing with an eager source who initiates a conversation is to grant confidentiality for the conversation but make clear that you may not publish the information unless the person will go on the record or unless you can verify it independently. Push back, and ask the person why she won’t be identified if she is so eager to get this information published.

Steve Buttry wrote more about these issues in a 2013 post “Use confidential sources to get on-the-record interviews” and in a 2010 post “Power and eagerness should guide reporters’ confidentiality decisions.”

Is the source powerful or vulnerable?

Journalists should be more willing to grant confidentiality to a vulnerable source than a powerful one. But keep in mind that power and vulnerability are both relative.

Mark Felt was a powerful man as associate director of the FBI. But he also was vulnerable, as Bob Woodward‘s famed “Deep Throat” source in the Watergate stories , when he was confirming information about wrongdoing that involved the White House. Also, he was reluctant rather than eager.

But other officials abuse their power by leaking classified information for political purposes.

Journalists have been lenient with many powerful people who seek to avoid accountability by doing their sniping from behind journalists. You may be better off missing a few stories than getting into this kind of abusive relationship. Keep in mind that some of the stories you get from these sources may be false or misleading; the sources are leaking partial or even false information because they aren’t accountable.

Steve Buttry discussed this issue in a 2010 post “Power and eagerness should guide reporters’ confidentiality decisions.”

Are the source and information worth going to jail for?

If good laws to protect confidential sources do not exist in your region, you need to consider whether law enforcement or someone in a civil court case will try to force you to reveal your source. Then you need to decide whether this story, the information the source is providing and the source himself is worth going to jail for.

Keep in mind that this is a calculation you need to make before granting confidentiality, not just before you publish. Reporters have been ordered by courts to reveal sources they did not even cite in stories.

It’s also worth noting that not every story based on confidential sources presents the threat of going to jail. Many stories present no risk at all (e.g. your local team is going to hire a new coach, and you have the news from unnamed sources before the official announcement).

How well can you protect the source?

A good rule of journalism and life is that you shouldn’t make promises you can’t keep. So, if you’re promising confidentiality to a source, especially one who might draw the attention of law enforcement or intelligence agencies, consider whether you can keep that promise.

If a law enforcement agency seizes your phone records, will they lead directly to your source? If an intelligence agency eavesdrops on your phone calls or snoops in your emails, will that lead to the source? What if the source’s employer checks the records for her company cell phone or checks her emails on her company account?

A journalist who promises confidentiality in a situation that could attract scrutiny by law enforcement, intelligence agencies or employers should learn about secrecy technology and then take simple steps to protect relationships with your sources. Meet in person when you can, in places where you can have some privacy. Discuss how to communicate, if at all, electronically. The situation will determine which options are best for you:

- Is it best (and sufficient) for either or both of you to communicate using personal (rather than work) computers and/or phones?

- Do you need to set up special email and/or social media accounts for communicating?

- Do you need to use a “burner” cell phone? (Don’t be too sure that it will protect your source.)

- Do you need to use encryption in any emails or documents you share?

- Is there a danger, in your country, that using encryption or other secure technologies could raise officials’ suspicions and lead to increased monitoring of your activities? Alternatively, might a court rule that if you use encryption for some messages, you have no expectation of privacy for those you don’t encrypt?

Jeremy Barr wrote a helpful piece for Poynter, “How journalists can encrypt their email.” However, technologies are constantly changing, so make sure you are using the latest advice available.

Do you trust the source?

Relations between journalists and sources require trust. The source has to trust the journalist to understand the story and report it accurately and fairly. The journalist has to trust the source to tell the truth.

Trust in a source depends on three things:

Your assessment of the source’s personal trustworthiness.

Your inquiry about how the source knows what he claims to know. An honest source can still be mistaken or have a faulty memory. “How do you know that?” and “How else do you know that?” are among the most important questions in journalism, and they are essential to ask when dealing with confidential sources.

Your ability to verify what the source tells you. You don’t have to make your demands for documentation and other sources a challenge to the source’s veracity. Everything you can verify through other sources is something you don’t have to pin on this source (or this source alone) and something that is harder to track back to the source.

Sometimes you can’t verify all the facts a source tells you. But if you verify some of the facts, you gain confidence in the source’s honesty and accuracy.

Will the information come out soon anyhow?

A lot of stories based on unnamed sources are stories that will become public in a day (or pretty soon) anyway.

You’re probably going to publish that story in most circumstances, unless you take a hard-line position against ever using unnamed sources. But you should consider whether a short-lived scoop is worth making sources and readers think you’re promiscuous about granting anonymity.

Nail down as much of the story as possible with sources that can be named. For example, can you verify that a university donor’s plane has flown to the city where the new coach lives? Or that the new coach has checked into a local hotel? Can you reach players or assistant coaches on the coach’s old team (or check their social media accounts) to see if they’ve been told? They won’t be as likely to honor a request to keep the secret until the announcement. You might be able to get someone else on the record.

Be specific about the terms of your agreement

When you discuss confidentiality, you need to be specific about the terms of your agreement. Be sure that the source understands you’re going to seek documentation and/or other on-the-record sources for the information.

Discuss whether you can attribute the information in some way to this source or whether this is just a tip.

If you can attribute, discuss how you will refer to the source, and avoid agreeing to a description that would be inaccurate or misleading.

An identification that’s overly broad (an “administration source”) is better than one that’s misleading. Particularly if the person doesn’t agree to a more specific or helpful description of who he is (“a close aide to the vice president”), negotiate what you can say about how the person knows (“according to a person who has read the report”).

When granting confidentiality for intimate personal stories, such as interviews with victims of domestic violence or sexual abuse, you might persuade a source to identify herself by her middle name (and to say in the story that you are using the middle name). Maybe a person will agree to use a childhood nickname or a birth name she no longer uses.

Some organizations will use a false name for a source (stating in the story, “not her real name”). Other news outlets take the position that they will carry nothing that is false, for any reason.

Discuss what will happen if the source is lying. Would you reveal a source who lies to you? (Keep in mind that sometimes a source has misinformation; not every bad tip you get is a lie.)

Discuss what will happen if you’re subpoenaed. Would you go to jail for the source? Would the source come forward in that circumstance? (Don’t expect this if the source is breaking the law by giving you this information.)

Powerful people sometimes talk with journalists in background briefings where they discuss issues on condition that they won’t be identified. Some journalists participate, but others have decided that the briefings don’t provide enough value to risk their credibility.

The Associated Press’ Statement of News Values and Principles (http://www.ap.org/company/News-Values) says, “Reporters should object vigorously when a source wants to brief a group of reporters on background and try to persuade the source to put the briefing on the record.”

You might consider going a step further in most circumstances and boycotting the briefing unless you know the information is unusually valuable. You can spend your time getting exclusive on-the-record stories rather than joining other media in an exercise that hurts everyone’s credibility.

What if a spokesperson wants confidentiality?

Journalists should be especially reluctant to quote a spokesperson without using her name. If she’s speaking for an official, organization or company, she should be on the record.

A rare exception might be when a spokesperson is giving you information that doesn’t relate directly to the official or organization she represents. You might also have valid reasons to grant confidentiality for a spokesperson who is revealing negative information about the person or organization he represents.

Some reporters deal with spokespeople whose organizations require that they speak only as a “spokesperson.” In these situations, keep in mind that mouthpiece statements often aren’t that important anyway. You might bolster your credibility by saying that a spokesperson wouldn’t give his name and the reasons didn’t meet your organization’s standards for confidentiality. Do that a few times, and the organizations you deal with may decide that they want to get their viewpoints out. You may also write simply that “the company said.”

Steve Buttry blogged about this in a 2012 post “Spokespeople should be named; set the bar high for confidentiality.”

After you talk, try again to get the source on the record.

At the end of an interview, ask sources again about going on the record for some or all of what they’ve said (Steve Buttry describes Eric Nalder’s “ratcheting” technique in his 2005 post “You can quote me on that.”

The main author of this module is Steve Buttry of Louisiana State University. It includes material from Buttry’s blog post on confidential sources .

See also the section in this project on “Sources: Reliability and Attribution.”

ETHICS IN THE NEWS

Ethical ground rules for handling sources, aidan white.

Good journalism is only ever as good as our sources of information. Most of those sources are personal, many are official, and some will be anonymous whistle-blowers. Together they provide reporters with the lifeblood of their trade – reliable, accurate and truthful information.

Journalists need to be as transparent as possible in their relations with sources. The news media have great power and people can be flattered when they are approached by reporters without understanding fully the risks to themselves and to others when they come into the public eye. This is particularly true of people caught up in humanitarian disasters, war or other traumatic events.

Journalists have to assess the vulnerability of sources as well as their value as providers of information. They have to explain the process of their journalism and why they are covering the story.

They should not, except in the most extraordinary circumstances, use subterfuge or deception in their dealings with sources.

Some questions that the ethical journalist will ask in establishing good relations with a source include:

- Have I clarified with my source the basis of our relations and have I been fully transparent about my intentions?

- Have I taken care to protect the source – for instance if they are a young person or someone in vulnerable circumstances – to ensure they are aware of the potential consequences of publication of the information they give?

- Am I confident the source fully understands the conditions of our interview and what I mean by off-the-record, on background, not-for attribution, or other labels?

- If a source asks for conditions before agreeing to an interview, what are my limits?

- Would I pay for a source’s expenses related to an interview? What legitimate costs could be paid?

- Would I agree to provide legal representation?

Of paramount importance is the need for journalists to reassure sources that their identity will be protected. But often this is easier said than done.

Protection of sources is well recognised in international law as a key principle underpinning press freedom. It has been specifically recognised by the United Nations and the Council of Europe.

Journalists and news media should establish guidelines and internal rules that help protect sources. Reporters may benefit from a clause in their contracts or agreements that clearly states their duties and obligations. National Public Radio in the United States has a clause in its guidelines that spells it out:

“Journalists must not turn over any notes, audio or working materials from their stories or productions, nor provide information they have observed in the course of their production activities to government officials or parties involved in or considering litigation. If such materials or information are requested in the context of any governmental, administrative or other legal processes this must be reported to the company.”

When faced with the decision to tell or not to tell in these circumstances, journalists must consider the impact of their actions and ask themselves some sharp questions:

- Who will benefit if this source is revealed?

- Who will suffer and who will lose?

- Will a criminal or powerful figure guilty of malpractice escape justice?

- Is this a case where the police and other investigating authorities are genuinely unable to provide the required information?

- Will the work of other journalists and the mission of media be compromised by revealing information?

- Will the public interest be served or not be served by cooperation?

In the end, journalists have to make their own decisions, based upon conscience and their own responsibility, but revealing a source of information is never to be taken lightly.

Don’t Get too Close to the Source

Sometimes journalists make the mistake of getting too close to their source. They sometimes create cosy relations that are ambiguous and can easily undermine the ethical base of their work. Powerful sources have their own agenda and accepting what they say without question crosses an ethical line and compromises newsroom independence.

The New York Times and other major news media in the United States, for instance, were heavily criticised before the invasion of Iraq in 2003 for relying too heavily on anonymous sources of information inside the government. Media coverage was highly deferential despite abundant evidence of the government’s flagrant misuse of intelligence information.

A chief offender was New York Times reporter Judith Miller, who produced stories in 2001 and 2002 about the government of Saddam Hussein in Iraq based on false information supplied by unnamed sources. She appeared to accept without question dubious information about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq from anonymous sources, including some at the Bush White House prior to the United States invasion in 2003.

Source Review of Content

The issue of who controls the story – the source or the reporter – comes up whenever copy approval is demanded, whether by high-profile and powerful figures or by sources themselves. It was a row at the heart of the falling out between WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and some major media over the handling of leaked official documents.

In many countries leading politicians and their spin doctors simply refuse exclusive interviews unless they can sign off on the final article. In Germany, it is accepted practice, even within the elite press, for journalists to submit the quotes they plan to use to politicians and other public figures, although most journalists claim they go along with this only for fact-checking and points of accuracy.

Given these conditions, journalists should ask themselves:

- Are there potential benefits to the accuracy of the story in allowing a source to review portions or all of it in advance of publication? In particular, are there technical aspects that might be clarified if incorrect?

- Are there potential pitfalls in doing so? Might the source respond in a manner harmful to the story or to others involved?

- If the source wants to change something in the story, such as a quote, how will I respond?

Anonymous Sources

Anonymity is a right that should be enjoyed by those who need it and should never be granted routinely to anyone who asks for it. People who may lose their job for whistleblowing; or young children; or women who are the victims of violence and abuse and others who are vulnerable and at risk from exposure are obviously entitled to it, but anonymity is not a privilege to be enjoyed by people who are self-seeking and who benefit by personal gain through keeping their identity secret.

Journalists should ask themselves:

- What is the likely motivation for demanding anonymity? Does that motivation potentially compromise me and my publication?

- Are there other methods I can employ to increase credibility while granting anonymity?

- Is there no other way to get and publish this information? Have I exhausted all other methods and potential sources?

- Do I or my colleagues have history with this source that speaks to his/her credibility?

- Have I maximised the level of identification that can be published without revealing the source’s personal identity?

Social Media and User-Generated Content

In today’s digital environment, rumour and speculation circulate freely and knowing what is real and how to verify news and information is essential. Reporters must be alert to the danger of falling for bad information from online sources whether it is user-generated content or social media. Digital-age sourcing is a major challenge, particularly in emergency coverage where rumour and falsehood can quickly add to the tension and uncertainty surrounding traumatic events.

Some questions a reporter might ask, in the case of social media, include:

- Have I corroborated the origin including location, date and time of images and content that I am using from social media?

- Have I confirmed that this material is the original piece of content?

- Have I verified the social media profiles of accounts I am using to avoid use of fake information?

- Is the account holder known to me and has it been a reliable source in the past?

- Have I asked direct questions of the content provider to verify the provenance of the information?

- Are any websites linked from the content?

- Have we looked for and found the same or similar posts/content elsewhere online?

- Have I obtained permission from the author or originator to use the material whether pictures, videos or audio content?

- Have I collaborated with others to verify and confirm the authenticity of content?

In the case of user-generated content:

- What do I know about the actual origin of this content? Can I verify the source?

- Are there copyright or legal issues around using the content?

- Have I ensured that all the information can be used and that the conditions for use are clear, for instance through Creative Commons Licence?

- Am I confident that there have been no reality-offering alterations (eg Photoshop) used?

In the case of sourcing breaking news:

- Before I report or retweet a development reported elsewhere, how confident am I in its accuracy?

- Would I potentially cause harm if I reported something before it is established at 100% certainty? Is there potential harm in not reporting it?

- Have I been careful to question first-hand accounts that can be inaccurate and manipulative, emotional or shaped by faulty memory and limited perspective?

- Have I triangulated the information with other credible sources?

- Have I acknowledged that the material I am using can be copied, distributed, and displayed, including derivative works based on it, and have I given credit to the original author and source?

Find out More: Craig Silverman, Editor of Regret the Error at the Poynter Institute, and Media Editor at BuzzFeed, has collaborated with the European Journalism Centre to produce a useful Verification Handbook.

You can read this article in Spanish thanks to FNPI: Preguntas que todo periodista debe hacerse sobre sus fuentes

When Human Rights Trump Protection of Sources

Over the years there have been hundreds of cases when courts and public authorities ordered journalists to hand over material or information that would reveal a source of information. In most cases the ethical reporter will instinctively demur. some will go to jail rather than betray a confidence.

Sometimes there are hard choices to be made. War correspondent Jonathan Randal of the Washington Post , for instance, famously refused to answer a subpoena in 2002 ordering him to appear before the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia which was prosecuting war crimes. Randal fought the subpoena with the backing of his paper and won. This action, which was supported by press freedom groups around the world, established some limited legal protection for war correspondents against being forced to give testimony.

But when conscience calls others have been willing to cooperate. Another journalist who reported on the Bosnian war in the 1990s, Ed Vulliamy of the Guardian , was happy to testify before the tribunal. His evidence helped convict and send to jail some of those responsible for war crimes. He argued that bringing to justice war criminals is a cause in which journalists, like other citizens, have a duty to join.

Main image: Journalist by Esther Vargas (Flickr – CC BY-SA 2.0)

BROWSE THE REPORT

Ethics in the News: Challenges for Journalism in the Post-Truth Era | 18th December 2016

Ethics in the News: Challenges for journalism in the post-truth era

Trumped: How US Media Played the Wrong Hand on Right-Wing Success

Media Lies and Brexit: A Double Hammer-Blow to Europe and Ethical Journalism

Fake News: Facebook and Matters of Fact in the Post-Truth Era

Tips for Exposing Fake News

Refugee Images - Ethics in the Picture

The Perfect Source: Edward Snowden, a Role Model for Whistleblowers and Journalists Everywhere

Panama Papers

Hate Speech: A Dilemma for Journalists the World Over

Ethics in the News: Challenges for Journalism in the Post-Truth Era | 4th January 2017

Hate Speech: India v Pakistan

Hate Speech: Africa

Hate Speech: Hong Kong

"Honour Killing"

Turkey: After an Attempted Coup the Journalists’ Nightmare

Support the work of the ethical journalism network.

If you share our mission, please consider donating to the Ethical Journalism Network. Your financial contribution will help the EJN to support journalists around the world who are striving to uphold ethical practices in order to build public trust in good journalism.

SUPPORT US NOW

The News Literacy Project

Evaluating unnamed sources in news reports

Published on September 12, 2018 Updates

John Silva, NBCT

Senior Director of Education and Training

On Sept. 5, the editors of The New York Times’ opinion page took what they called “the rare step of publishing an anonymous Op-Ed essay.” The action raises an important issue in journalism and an opportunity to teach students about evaluating unnamed sources in the news.

By “unnamed sources,” I am referring to the people who provide information published in news reports, editorials and other opinion pieces but whose names are not given. (It’s important to remember that the source’s identity is unknown to us — the readers, viewers and listeners — but is known by the journalist and, usually, at least one editor at the news organization.)

Being a critical consumer of news includes understanding and evaluating different types of sources — such as official sources, eyewitness sources, raw video and documents — to determine whether a news article is credible. Evaluating the words of individuals who are not named requires a closer look at both the journalist and the news organization.

Most news articles routinely attribute key facts to a source who is identified by name and, often, by title — information telling us why the source is in a position to know about and comment on the topic. When the source is unnamed, news consumers should consider two key elements: why the source desires anonymity, and what is behind the source’s decision to share this information.

Here is how The Associated Press, a global news agency that produces more than 2,000 news stories per day, defines the terms used in granting anonymity (parenthetical information in the definitions is not from AP). Other news organizations may have their own definitions of these terms. Both the reporter and the source must agree to these ground rules before an interview.

- On the record: The information can be used with no caveats, quoting the source by name.

- Off the record: The information cannot be used for publication. (But the reporter can use this knowledge to get the information verified elsewhere.)

- On background: The information can be published but only under conditions negotiated with the source. Generally, the sources do not want their names published but will agree to a description of their position. (Other news outlets may refer to this as “not for attribution”; some may even distinguish between “not for attribution” and “on background.”)

- On deep background: The information can be used but without attribution. The source does not want to be identified in any way, even on condition of anonymity.

Why do journalists use unnamed sources, especially since it might endanger the trust the public has in their work? After all, the public should know whether these sources are in a position to be fully informed on the matter or are offering a skewed version that serves their purposes, not ours.

The news organization’s obligation

For starters: Good news organizations do not publish information from unnamed sources without consideration and thorough vetting. As reporter Jason Grotto of ProPublica Illinois wrote , his organization’s ethics guidelines allow sources to remain unnamed “only when they insist upon it and when they provide vital information,” “when there is no other way to obtain that information” and when the journalist knows that the source is “knowledgeable and reliable.”

Typically, journalists share the names of these sources with their editors, who assess whether those criteria are met.

As the Society of Professional Journalists’ ethics code notes, “Consider sources’ motives before promising anonymity. Reserve anonymity for sources who may face danger, retribution or other harm, and have information that cannot be obtained elsewhere.”

Motives, of course, vary. The source may be acting as a whistleblower, exposing corruption or other illegal conduct. The source may feel compelled to share information with the public that is being withheld for some reason. Or — and good journalists know this — the source might have personal interests at heart. That does not necessarily disqualify the accuracy of the information, but it is why one standard of quality journalism is verification of facts by multiple sources.

News organizations that use unnamed sources owe it to their readers, viewers and listeners to clarify, as much as possible, why the source was granted anonymity, and why the source’s motives did not invalidate the value of the information.

The news consumer’s obligation

The challenge for news consumers is that the use of unnamed sources provides no outside way to verify what the journalist has written. We must decide whether to trust the journalist and the news organization. Fortunately, there are some actions we can take that help build that trust.

When evaluating a news article that uses unnamed sources, take a step back and engage in lateral reading* about the journalist who wrote the article and the news organization that published the report. Take a look at other articles by that journalist: How often does he use unnamed sources? (Is he lazy, or is he privy to officials who have great — but classified — information?) Does she write about this particular subject regularly, indicating that she has in-depth knowledge? Does the journalist also write opinion pieces? (If so, this could indicate a bias that must be evaluated.)

Consider, too, whether the journalist has provided sufficient context to determine whether the source is reliable and credible. In “When To Trust A Story That Uses Unnamed Sources,” Perry Bacon Jr. of FiveThirtyEight gives five details that readers should look for when considering a story that uses unnamed sources. His follow-up post, “Which Anonymous Sources Are Worth Paying Attention To?,” explains how to evaluate the description applied to an unnamed source — such as “a Pentagon official,” “a person familiar with” or “a law enforcement official.” The more details the journalist provides about a source, the more comfortable we can be trusting what that source has to say.

More fundamentally, has the article explained why the source was granted anonymity? Explaining why a source isn’t named — for example, attributing behind-the-scenes information about congressional action to “a committee aide who was not authorized to speak publicly about the meeting” — is something we can evaluate. Check to see if the news organization has a published policy on using unnamed sources (such as these from The Washington Post and NPR ).

We shouldn’t dismiss the use of anonymous sources out of hand. Particularly when reporting about the government, journalists often must rely on sources who have a justifiable concern about being named; at the same time, they must recognize that using anonymous sources may make their work appear less credible. In 2013, Margaret Sullivan, then the public editor of The New York Times, quoted a national security editor who said of government sources, “It’s almost impossible to get people who know anything to talk,” especially on the record. “So we’re caught in this dilemma.”

As for that op-ed in The New York Times, the author is described as “a senior official in the Trump administration whose identity is known to us and whose job would be jeopardized by its disclosure.” Whether the opinion page editors made a good decision in publishing the piece remains up for debate. And that’s what we, as critical consumers of news, should be able to do: Evaluate the available information and make our own determination about the credibility of what was published.

Further reading:

- Chapter 59: Sources of information (The News Manual)

- “Which Anonymous Sources Are Worth Paying Attention To?” (Perry Bacon Jr., FiveThirtyEight)

- “When To Trust A Story That Uses Unnamed Sources” (Perry Bacon Jr., FiveThirtyEight)

- “How do you use an anonymous source? The mysteries of journalism everyone should know” (Margaret Sullivan, The Washington Post)

- “Using anonymous sources with care” (H.L. Hall, Journalism Education Association)

- “What Does ‘Off the Record’ Really Mean?” (Matt Flegenheimer, The New York Times)

**The lateral reading concept and the term itself developed from research conducted by the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG), led by Sam Wineburg, founder and executive director of SHEG.

More Updates

Npr april fools’ day story cites advice from nlp rumorguard lead writer dan evon.

This April Fools’ Day, NPR offered tips for people to avoid falling for online pranks, and included news literacy tips from Dan Evon, NLP’s senior manager of education design.

Published on Apr 11, 2024 NLP in the News

School’s entire freshmen class learning news literacy with NLP’s resources

Pennslyvania educator Pam Szabo develops a media and news literacy curriculum for all freshman using News Literacy Project resources.

Published on Apr 9, 2024 Updates

Vote for us! Checkology is nominated for a Webby Award

Checkology® is in the running for top honors in The Webby Awards, the Academy of Digital Arts and Sciences’ signature awards program.

Published on Apr 3, 2024 Updates

Search Close

How to Write a News Article: Naming Sources

- What Is News?

- How to Interview

- The Intro or Lede

- Article Format/Narrative

- How To Write A Review

- Writing News Style

- Naming Sources

- Revising/Proofreading

- Photos/Graphics

- The Future of News?

About Sources

A good reporter makes it clear where he or she got their information. Everything but the most obvious and commonly known facts should be attributed. When in doubt, don’t assume your reader knows. State where you got your information. The reader can then decide how reliable a story is.

As in an essay, the source needs to be named in the story:

- The mayor expressed his support of a designated zone for protesters.

- According to police records, the suspect had been arrested for fraud before.

- The jury will announce its decision tomorrow, the court bailiff stated.

Unlike an essay, the source does not need a text citation in the story after each attribution or to be listed in a reference or works cited list.

All quotes must be attributed . Include the name of the person speaking in the sentence and surround their exact words in quotations marks.

- For example – Former President George Bush said, “Read my lips. No new taxes!”

- Never change what someone said – Doublecheck if you’re not sure of the exact wording.

- If a grammatical error in the exact quotation might make the person look bad, then the reporter needs to decide if it would be unfair to leave the mistake. Check with your editor.

Use multiple sources. Stories are more balanced when multiple points of view are presented. Make sure you don’t use just the official source for information. Try to talk with all parties involved.

- For example – A story on panhandling needs to include information from people who ask for money, people who’ve been asked for money, people who’ve given money, and people who refused – not just city officials.

Because sources have different perspectives, their information may contradict. The reporter has a responsibility to doublecheck information for accuracy.

- In the example above, any claim of increased panhandling should be checked with public records. Is there an increase in complaints or police action? Can you observe for yourself or ask people who regularly drive those streets for their observation?

It's a challenge for any organization.

- Only 1% of all the stories The Pew Research Center's Project for Excellence in Journalism examined during the Clinton-Lewinsky saga used two or more named sources.

In particular, any opinion must be attributed. Adding the opinion of persons involved in the story can add personal perspective to a story. However, the reporter should never include or shape the story to show his or her opinion. The reporter's job is to build a complete picture that the reader can base a decision on.

More About Sources

- 4 Best Plagiarism Checker Tools

- Advice on attribution for journalists

- Anonymous Sources

- Editor’s guide to identifying plagiarism

- Fairness and Accuracy in Media

- Quotes and Attribution

- Sources and confidentiality

- Sources of information

- Talk to the Newsroom: The Use of Anonymous Sources

- What is plagiarism?

- << Previous: Writing News Style

- Next: Headlines >>

- Last Updated: Oct 23, 2023 11:28 AM

- URL: https://spcollege.libguides.com/news

Module 9: Beyond the Research Paper

Journalism and investigative reporting, learning objectives.

Identify characteristics of effective journalism and investigative reporting

News messages are often broken into three categories: “hard” news, “soft” news or features, and opinion. “Hard” news comprises reports of important issues, current events, and other topics that inform citizens about what is going on in the world and their communities while “soft” news covers those things that are not necessarily important and are handled with a lighter approach. Opinion pieces, unlike the other two which value “objectivity,” are subjective and will have a specific point of view.

- Breaking news – Sometimes referred to as “the first take on history” breaking news stories provide as clear and accurate an accounting of some kind of event as possible while it is happening. In reporting about wildfires raging in the west, the breaking news story requires a timely accounting of what’s happening, with a tight focus on the “who, what, when, where, why” and it requires well-honed observation and interviewing skills. For the breaking news story, the information tasks for the reporters are to show up, assess the situation, use their senses to cover the event and learn more information through first-person interviews. Breaking news provides the “need to know” information as an event unfolds.

- Depth report – The depth report is the story after the breaking news report. The goals for journalists preparing a depth report are to try to help people understand how the event happened, who was affected, what is being done about it, how people are reacting. For instance, in the aftermath of a story about wildfires in the West, the reporter’s information tasks would include gathering background information about the firefighting efforts, the economic impact of the fires, the reactions of home and business owners, the potential impact that the weather might have on future similar events. As with the breaking news story, the journalist is transmitting information, not opinion and they must be able to identify the most knowledgeable sources.

- Analysis or interpretive report – The focus here is on an issue, problem or controversy. The substance of the report is still a verifiable fact, not opinion. But instead of presenting facts as with breaking news or a depth report and hoping the facts speak for themselves, the reporter writing an interpretive piece clarifies, explains, analyzes. The report usually focuses on WHY something has (or has not) happened. The information tasks are greater for this type of report, due to the need to clarify and explain rather than simply narrate. An analysis of the wildfires might look into how environmental policy or urban sprawl factored into the event. Analyses generally require learning about different perspectives or ranges of opinion from a variety of experts and more “digging” into causes.

- Investigative report – Unlike the analysis which follows up on a news event, the information tasks for an investigative report require journalists to uncover information that will not be handed to them, these stories are reported by opening closed doors and closed mouths. These are the stories that expose problems or controversies authorities may not want to see covered. This requires unearthing hidden or previously unorganized information in order to clarify, explain and analyze something. A key technique used in investigative reports is data analysis. In the aftermath of the wildfires, a news organization might investigate the insurance claims process or how a charitable organization that received relief funds for fire victims actually allocated the money. The investigative report requires the communicator to have a high level of information sophistication, and the ability to convey complex information in a straightforward way for the audience.

- News – A story about a man who used cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to revive a pet dog rescued from the bottom of a pool might be reported as a news feature. It is based on an event, but covered as a feature, but the information tasks require gathering material to put more emphasis on the drama of the event than on the information about how to do CPR on a dog.

- Personality sketch or profile – A story about the accomplishments, attitudes and characteristics of an individual seeks to capture the essence of a person. This requires both thorough backgrounding of the subject and skills in interviewing as information tasks. The communicator has to have a well-honed ability for noticing details that bring to life what is interesting or unique about the person.

- Informative – A sidebar to accompany a main news story might be written as an informative feature. For example, an informative feature that describes the various methods firefighters use to combat wildfires might accompany a breaking news story. The information tasks for the reporter include a good command of sometimes-technical information to convey the story to the audience.

- Historical – Holidays are often the inspiration for this type of piece, with focus on the history of the Christmas tree, the first Thanksgiving dinner, etc. The curious communicator could also create features about the anniversary of the founding of an important local business or the celebration of statehood using background archival documents. The information tasks for these types of reports obviously require locating and interpreting extensive historical information.

- Descriptive – Many features are about places people can visit, or events they can attend. Tourist spots, historical sites, recreational areas, and festivals all generate reams of feature story copy, pictures and video. Public relations specialists often have a significant hand in generating much of the background information in these types of features and promoting these events or places to the news media. The information tasks include finding a fresh and engaging angle for the content.

- How-to – Some features are created to provide information about how to improve your golf game, become a power-shopper, install your own shower tile. The communicator has to have a solid grasp of the subject matter to do a respectable job with this type of piece. The information tasks for how-to features include the need for material that is descriptive, specific, and very clearly communicated.

- Editorials – The editorial is a reflection of management’s attitude rather than a reporter’s or editor’s personal view. Most are unsigned and run on a specific page of the newspaper or website or during a particular time of the broadcast. Editorials usually seek to do one of three things: commend or condemn some action; persuade the audience to some point of view; or entertain and amuse the audience. The information tasks for an editorial include locating and using credible information as evidence for whatever position is being taken.

- Columns – A column includes the personal opinions of the writer on the state of the community and the world. Many columns are written by syndicated, national writers, but local commentators and columnists also have a following in their communities. Columnists use information selectively, based on their point of view and the argument they are making. Columnists’ information tasks include maintaining a consistent “voice” and approach to each topic.

- Reviews – Reviewers make informed judgments about the content and quality of something presented to the public–books, films, theater, television programs, concerts, recorded music, art exhibits, restaurants. The responsibility of reviewers is to report and evaluate on behalf of the audience. The information must be descriptive as well as evaluative. The reviewer describes the concert and then makes an evaluation of the quality of the performance. Reviewers’ information tasks require them to be deeply knowledgeable about the type of content or activity they are reviewing, as well as having an opinion about it.

Why does this matter? If journalists don’t create stories that inform and engage their audience those people will find other outlets to satisfy their information needs. Journalism serves not only a public need, it is also a business and a business without customers won’t be in business for long.

News organizations conduct user surveys and track audience behavior just as other kinds of companies do. The better journalists are able to understand their readership the better able they will be to anticipate and address their audiences needs. With the ability to track digital readership, journalists know what articles people read. At the start of the message analysis process journalists must ask a set of questions about their target audience that will help them identify the treatment of the topic about which they will be writing and make decisions about the kind of reporting they must do.

Understanding the audience that uses the publication or media outlet for which they are producing a news report will help clarify some of the following questions:

WHO: Who reads / views the publication? Who would be interested in this topic? Who needs to know about this topic? Who is the media organization interested in attracting with its offerings?

WHAT : What would the potential audience member want to know about the topic? What kind of report would be most informative or helpful for the audience? What kind of information will be useful? What does the audience already know about this?

WHERE: Where else do people interested in the topic find information? (For freelancers) Where should I pitch my story idea?

WHEN: When does the audience need to get this information (is this fast-breaking news, or something that will be used as analysis after the event?)

WHY: Why does the audience need to know this? Why does the audience care? Sometimes the audience member just wants to fill empty minutes with a news message (reading news briefs on a mobile device while standing in a line or eating alone at a restaurant). Sometimes the audience member needs to answer a specific question (who won the baseball game this afternoon? when does the movie start?). Each of these “why” questions suggests a different strategy for the communicator.

HOW: How can we best communicate to the audience? How much background do they need to understand what we are writing about? How technical can we be? How might the audience react to this report?

- News Messages / Audience. Authored by : Kathleen A. Hansen and Nora Paul. Located at : https://open.lib.umn.edu/infostrategies/chapter/2-4-news-messages/ . Project : Information Strategies for Communicators . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Newspaper. Provided by : The Creative Exchange. Located at : https://unsplash.com/photos/9WuHgaEQagY . License : CC BY: Attribution

5 Attribute All Sources

Kerry Benson

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Distinguish between primary and secondary, and human and nonhuman sources.

- Explain why and when attribution is necessary.

- Use proper mechanics of attribution.

- Embed links to online sources in digital text.

Ladybug Rock, by Mark Caton

My father, a Presbyterian minister, rarely used the King James Version of the Bible, so I remember vividly when he referenced the Apostle Paul’s letter to the Romans from the KJV.

Romans 13:7 reads: “Render therefore to all their dues: tribute to whom tribute is due; custom to whom custom; fear to whom fear; honour to whom honour.”

Because I was a child, the language of the passage confused me, and I asked my dad what it meant. He laughed before briefly summing up Paul’s message.

“It pretty much means you give people recognition for what they’ve done,” my dad said. “Like when your mom and I really liked the ladybug rock you brought home from school and you told us Mark Caton was the one who painted it. You gave Mark what was due to him, the credit for being the painter, instead of telling us you’d done it.”

Not everyone needs a biblical lesson on giving credit where it’s due. And credit isn’t necessarily an acknowledgment of excellence, as Mark Caton could have done a poor job of painting a ladybug on stone, but in journalism and strategic communications attribution is like that ladybug: a rock. It’s one of the ethical (and often lawful) foundations of a news or feature story, a documentary, a company news release, a digital ad, or a marketing PowerPoint.

This chapter will help illuminate the concept of attribution, why it matters, who uses it, who benefits from its use, when it’s used, and why professionals may disagree on its use. This chapter also will address how to journalistically cite sources, how attribution can go wrong, and where to find more on the topic.

What is Attribution?

Reputable and engrossing writing, whether it’s journalism or strategic communication, starts with responsible and principled research and reporting. Attribution is vital to all ethical reporting because it identifies information sources.

The Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications (ACEJMC), which accredits journalism schools, lists core values and competencies all graduates should be able to meet. Among those competencies is the ability to “demonstrate an understanding of professional ethical principles and work ethically in pursuit of truth, accuracy, fairness and diversity.” Attribution is key to the quest for veracity and transparency. Attribution’s job in journalism is to answer the “who” of a quotation, the “where” and “what” of background information, and –- sometimes –- the “how.”

Who said what? Where did reporters or editors get their data? What research was used to support an opinion? How did a human source provide those statistics?

Understanding attribution requires understanding sources.

Primary Sources

If a human contributes information for a story, whether it’s in-person, on the phone, or via email or text, that person is a source. The most credible human source is a primary one, a person with a direct connection to the information or situation pertinent to the story.

This first-hand relationship provides for an accurate telling of that person’s experience. Even though the source’s personal viewpoint can be an opinion, it can also provide a reporter with facts. It’s the reporter’s responsibility to confirm the facts. An exception to this is if the journalist is the witness to events. Journalists can’t name themselves as sources in articles.

Primary human sources also add what it sounds like –- humanness. They put a face to the facts and a person to the perspective. Often they can synthesize information in a way that makes it accessible and easy to understand for other people.

Any person who contributes any kind of information to a story is a human source, even if that material is never published or broadcast.

Primary human source examples:

Chadwick Boseman, star of the Disney and Marvel Studios film “Black Panther,” says in a 2018 interview with USA Today how respectful he is of the cinematic history the movie was about to make.

Infections, like the kind caused by what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention call “nightmare bacteria,” are drug-resistant and “virtually untreatable with modern medicine,” CDC Principal Deputy Director Dr. Anne Schuchat said in a press briefing .

The reporter in each scenario above indicates to readers or viewers where the information originates. The importance of primary source credibility is clear. The main actor in a film will know about acting in that film. Schuchat, who served as acting director of the CDC twice, will know the agency’s public health concerns and alerts.

A journalist could probably get the same information from a nonhuman source, but Boseman and Schuchat put a trustworthy human face to the communication they’re sharing.

Primary sources also can be nonhuman. Government records, reports of original research studies, and polls are examples of primary sources because they are the original locations of the information they contain. A nonhuman source is primary if it provides original information that does not cite other sources.

Some sources, like research studies, often are both primary and secondary sources, because they both re-state information found elsewhere, and are the original sources of other information.

Primary nonhuman source examples:

April is designated as Alcohol Awareness Month by the federal government. A journalist developing a story about drug and alcohol trends among seniors, or in a specific geographical region, might use data published by the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (NCADD), a primary nonhuman source.

Marketers at a major health care organization choose similarly to highlight the importance of alcohol awareness, and they also provide NCADD data in a story in their monthly e-zine or quarterly newsletter. NCADD serves as a primary nonhuman source. The marketers supplement their story with human primary sources from within their organization, such as physicians and counselors.

Journalists and strategic communicators should not leave their audience to question information or sources’ legitimacy. The exception is if something is a well-known –- or widely reported –- fact that’s reasonably indisputable.For example, it would not be necessary to cite a source for “Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, delivered what would come to be known as ‘The Gettysburg Address’ in November 1863.”

Secondary Sources

Both human and nonhuman sources also can be secondary sources, or research material. A secondary source is information containing others’ reporting and data gathering, and it’s usually information used for other purposes as well as a journalist or strategic communicator’s purposes.

Journalists must determine if the secondary source information is fact or opinion, or both, which they usually do by cross-referencing the information with other verifiable sources.

If a reporter looks to a website for background information, or reads other media reports on a story, it’s the reporter’s responsibility to go to the information’s original, or primary, source.

Avoid quoting The New York Times or Fox News as a source from their stories on obesity in the United States. Go to the primary source those media reference. If they cite a study, or data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), go to that study or to the CDC website. After verifying the information, cite the study or the CDC.

For example, a reporter working on an article about border crossings along the United States’ southern border sees a CNN report on a similar story, using data about who is crossing and where. The reporter should look for the source of the data, not CNN’s information. If the numbers are from U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the reporter should go to CBP for its facts and figures, and cite it as the source.

Often journalists use secondary sources as a springboard to develop a story idea, including a single exposé, an in-depth series of articles or podcasts, or a documentary. From these secondary sources, they look for the primary sources of information, and use those in their reports.

When To Attribute?

The late journalist Steve Buttry, whose résumé included editor, reporter, newsroom trainer, and teacher of digital journalism, wrote the following in a blog post, “You can quote me on that: Advice on attribution for journalists” :

“Attribute any time that attribution strengthens the credibility of a story. Attribute any time you are using someone else’s words. Attribute when you are reporting information gathered by other journalists. Attribute when you are not certain of facts. Attribute statements of opinion. When you wonder whether you should attribute, you probably should attribute in some fashion.”

Buttry’s advice from the same post on when not to use attribution is shorter:

“Don’t attribute facts that the reporter observed first-hand: It was a sunny day. Don’t worry about attributing facts where the source is obvious and not particularly important and the fact is not in dispute.”

Journalists and strategic communicators who write or report factual information or opinions should attribute all those facts and opinions to a source. In some circumstances, attribution is particularly important. Attribute facts if controversy might surround them, such as when gun permit requests go up or down, or the number of middle-aged men addicted to opioids changes dramatically. Also, always attribute evaluative facts that depend on the rule of law, or facts that rely on an expert’s information.

In broadcast, reporters and podcasters should identify the source of any statement, particularly one of questionable accuracy. The source interviewed in a radio, podcast or videotaped segment must be identified at the start. The newscaster, reporter, or podcaster can identify with a sound bite before the source speaks.

With video, a source can be acknowledged verbally and with a lower third super, a graphic, usually the interviewee’s name and location, superimposed along the bottom of the screen.

Why Attribute?

Both journalists and strategic communicators use attribution to signal to their audiences that they’re reliable and sincere. It indicates that they’ve vetted the sources, which helps readers, listeners and viewers understand the information effortlessly, without having to stop and question the content’s accuracy and authenticity.