- Camp Invention (K-6th)

- Camp Invention Connect (K-6th)

- Refer a Friend Rewards Program

- Club Invention (1st-6th)

- Leaders-in-Training (7th-9th)

- Leadership Intern Program (High School & College Students)

- About the Educators

- FAQs for Parents

- Parent Resource Center

- Our Programs

- Find a Program

- Professional Development

- Resources for Educators

- FAQs for Educators

- Program Team Resource Center

- Plan Your Visit

- Inductee Search

- Nominate an Inventor

- Newest Inductees

- Induction Ceremony

- Our Inductees

- Apply for the Collegiate Inventors Competition

- CIC Judging

- Meet the Finalists

- Past CIC Winners

- FAQs for Collegiate Inventors

- Collegiate Inventors Competition

- Register for 2024 Camp

- Learning Resources

- Sponsor and Donate

50 Years of Innovation: Supporting Problem Solving

“I think there’s a huge satisfaction to coming up with solutions to problems, and especially to problems that really make a difference in people’s lives. I can’t imagine a more satisfying career than being able to do that.” — National Inventors Hall of Fame ® Inductee Frances Arnold, inventor of directed evolution of enzymes

National Inventors Hall of Fame Inductees are the world’s greatest problem solvers. From taking on complex challenges that shape industries to developing ideas that make our everyday lives easier, visionary inventors make the world a better place.

For 50 years, the National Inventors Hall of Fame has honored the most influential U.S. patent holders. As we look ahead to the next 50 years, we remain committed to not only telling our Inductees’ stories but also supporting the next generation of great problem solvers.

Learning From Solution Seekers

Every invention begins with a challenge to be overcome. From making everyday tasks easier to creating lifesaving devices, inventors create solutions by applying the right mindset. At the National Inventors Hall of Fame, we call this the I Can Invent ® Mindset. It’s a way of looking at the world with curiosity, ingenuity and a passion for finding ways to make the world a better place.

The I Can Invent Mindset combines creative problem solving, confidence, persistence, collaboration and design thinking with STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) skills, intellectual property knowledge, entrepreneurship and innovation. Over the last 50 years, the National Inventors Hall of Fame team has learned that while our Inductees represent diverse fields, backgrounds, perspectives and experiences, this mindset is one thing they all have in common.

Inductee Marion Donovan took on the daily challenges of changing her daughter's cloth diapers, clothing and bed sheets by creating, patenting and marketing a waterproof diaper cover. Inductees Stewart Adams and John Nicholson were tasked with finding new treatments for rheumatoid arthritis, so they collaborated for a decade to develop ibuprofen – one of the world’s safest, most effective and most widely used pain relievers. When Inductee Patricia Bath , an ophthalmologist, found that Black patients were far more likely to have glaucoma and experience a higher degree of vision loss, she revolutionized care by developing the discipline of Community Ophthalmology and inventing laserphaco cataract surgery.

These are just a few of the more than 600 problem-solving stories you’ll find when you read more about our National Inventors Hall of Fame Inductees .

Solving for the Future

To carry the problem-solving legacy of the world’s greatest innovators into the future, the National Inventors Hall of Fame collaborates with our Inductees to create one-of-a-kind education programs for children across the country. Programs like Camp Invention ® and Invention Project ® guide children to build the I Can Invent Mindset by developing their own solutions to real-world problems through creative, hands-on, fun.

“Why is problem solving so fun and interesting?” asks Inductee R. Rox Anderson, inventor of laser dermatology. “Well, it has that pleasure associated with actually changing the world.”

Each of our education programs is designed to help children discover the joy Anderson describes. While building the problem-solving skills that will help them navigate their lives, children learn that just like our Inductees, they have the potential to change lives and shape the world around them.

“My child felt included and considered during problem-solving situations, which made him feel more confident. He also feels more confident with knowing how to start creating his own inventions.” — Sarah S., Camp Invention parent, King George, VA

“My children were able to use their minds creatively and build upon their problem-solving skills. They worked together with friends they knew and with new friends they met. Camp Invention helped my kids become more independent and boosted their self-confidence. They loved it!” — Rebecca W., Camp Invention parent, Westport, CT

“The most meaningful parts [of National Inventors Hall of Fame education programs] were the problem solving for the students. They were in a safe place to try new ideas and see how their thoughts worked out.” — Kim E., Educator, Burleson, TX

“The opportunity for kids to make mistakes while developing their ideas is always my favorite part. This is a hard concept for kids these days, and Camp Invention makes it fun to fail in order to succeed.” —Stefan T., Educator, South Lyon, MI

Share Your Story

Do you have a story about how you or your child has solved a problem, or how your life has been improved by a great problem solver? Visit our website to share your story and learn how you could win a trip to Washington, D.C., to help us celebrate our 50th anniversary at our 2023 Induction Ceremony!

Related Articles

Maria-teresa correll’s inspiring camp invention journey, exploring careers in steam at camp invention, explore camp invention’s inspiring new 2024 curriculum.

History Cooperative

Daedalus: The Ancient Greek Problem Solver

Daedalus is a mythical Greek inventor and problem solver who is one of the most well-known figures in Greek mythology. The myth of Daedalus and his son, Icarus, has been passed down from the Minoans. The Minoans thrived on the Greek islands in the Aegean Sea from 3500 BCE.

The stories of the genius Daedalus are as enthralling as they are tragic. Daedalus’ son, Icarus, is the boy who perished when he flew too close to the sun, wearing wings his father had fashioned.

Daedalus was responsible for creating the labyrinth that housed the bull-headed creature, known as the minotaur. Homer makes mention of the inventor in the Odyssey, as does Ovid. The myth of Icarus and Daedalus is one of the most famous stories from ancient Greece.

Table of Contents

Who is Daedalus?

The tale of Daedalus, and the precarious situations he found himself in, have been told by ancient Greeks since the Bronze Age. The first mention of Daedalus appears on the Linear B tablets from Knossos (Crete), where he is referred to as Daidalos.

READ MORE: Prehistory: Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic Periods, and More

The civilization that developed on mainland Greece, known as the Mycenaeans, was similarly enamored with the antics of the skilled inventor. The Myceneans told similar myths about the great carpenter and architect Daedalus, his family rivalries, and the tragic demise of his son.

Daedalus is an Athenian inventor, carpenter, architect, and creator, who the Greeks credit with the invention of carpentry and its tools. Depending on who retells the tale of Daedalus, he is Athenian or Cretian. The name Daedalus means “to work cunningly.”

The ancient master craftsman was blessed with his genius by the goddess Athena . Daedalus is known for the intricate figurines he carved, called Daedalic sculptures, and almost life-like sculptures called auto automatos.

READ MORE: Greek Gods and Goddesses

The sculptures are described as being extremely life-like, giving the impression they are in motion. Daedalus also designed children’s figurines that could move, likened to modern action figures. Not only was he a master carpenter, but he was an architect and builder too.

Daedalus and his son Icarus lived in Athens but had to flee the city when Daedalus was suspected of murder. Daedalus and Icarus settled in Crete, where most of Daedalus’ inventions were made. Daedalus settled in Italy in later life, becoming the palace sculptor for King Cocalus.

In addition to his many creations, Daedalus is known for attempting to murder his nephew Talos or Perdix, but he is most known for inventing the wings that led to his son’s death and for being the architect of the labyrinth that housed the mythical creature, the minotaur .

What is the Myth of Daedalus?

Daedalus first appears in ancient Greek mythology in 1400 BCE but is mentioned more frequently in the 5th Century. Ovid tells the tale of Daedalus and the wings in the Metamorphoses. Homer mentions Daedalus in both the Iliad and the Odyssey .

READ MORE: Ancient Civilizations Timeline: The Complete List from Aboriginals to Incans

The myth of Daedalus gives us insight into how the ancient Greeks perceived power, invention, and creativity within their society. The story of Daedalus is intertwined with the tale of the Athenian hero Theseus , who slew the minotaur.

The myths of Daedalus have been a popular choice for artists for millennia. The most frequent depiction found in ancient Greek art is the myth of Icarus and Daedalus’ flight from Crete.

Daedalus and Family Rivalry

According to Greek mythology Daedalus had two sons, Icarus and Lapyx. Neither son wanted to learn his father’s trade. Daedalus’ nephew, Talos, showed interest in his uncle’s inventions. The child became Daedalus’ apprentice.

Daedalus tutored Talos in the mechanical arts, for which Talos had great potential and talent, Daedalus was excited to share his knowledge with his nephew. The excitement quickly turned to resentment when his nephew showed a skill that could eclipse Daedalus’ own.

His nephew was a keen inventor, on his way to replacing Daedalus as the Athenian’s favorite craftsman. Talos is credited with the invention of the saw, which he based on the spine of a fish he saw washed up on the beach. In addition, Talos is believed to have invented the first compass .

Daedalus was jealous of his nephew’s talent and feared he would soon surpass him. Daedalus and Icarus lured his nephew to the highest point of Athens, the Acropolis . Daedalus told Talos he wanted to test his latest invention, wings.

Daedalus threw Talos from the Acropolis. The nephew did not die but instead was rescued by Athena , who turned him into a partridge. Daedalus and Icarus became pariahs in Athenian society and were driven out of the city. The pair fled to Crete.

Daedalus and Icarus in Crete

Daedalus and Icarus received a warm welcome from the king of Crete, Minos , who was familiar with the Athenian inventor’s work. Daedalus was popular in Crete. He served as the king’s artist, craftsman, and inventor. It was in Crete that Daedalus invented the first dancefloor for Princess Ariadne.

While in Crete, Daedalus was asked to invent a rather peculiar suit for the king of Crete’s wife, Pasiphaë. Poseidon , the Olympian god of the sea , had gifted the Minoan king and Queen a white bull to be sacrificed to him.

READ MORE: Olympian Gods

Minos disobeyed Poseidon’s request and kept the animal instead. Poseidon and Athena sought revenge on the king by making his wife lust after the bull. Consumed with desire for the beast, Pasiphaë asked the master craftsman to create a cow suit so that she could mate with the animal. Daedalus created a wooden cow that Pasiphaë climbed inside to perform the act.

Pasiphaë was impregnated by the bull and birthed a creature that was half man, half bull called the Minotaur. Minos ordered Daedalus to build a Labyrinth to house the monster.

Daedalus, Theseus, and Myth of the Minotaur

Daedalus designed an intricate cage for the mythical beast in the form of a labyrinth, built beneath the palace. It consisted of a series of twisting passageways that seemed impossible to navigate, even for Daedalus.

King Minos used the creature to seek revenge on the Athenian ruler after the death of Minos’ son. The king asked for fourteen Athenian children, seven girls, and seven boys, which he imprisoned in the labyrinth for the Minotaur to eat.

One year, the prince of Athens, Theseus, was brought to the labyrinth as a sacrifice. He was determined to defeat the Minotaur. He succeeded but became confused in the labyrinth. Luckily, the king’s daughter, Ariadne had fallen in love with the hero.

Ariadne convinced Daedalus to help her and Theseus defeat the minotaur and escape the labyrinth. The princess used a ball of string to mark the way out of the prison for Theseus. Without Daedalus, Theseus would have been trapped in the maze.

Minos was furious with Daedalus for his role in helping Theseus escape, and so he imprisoned Daedalus and Icarus in the labyrinth. Daedalus hatched a cunning plan to escape the labyrinth. Daedalus knew he and his son would be caught if they tried to escape Crete by land or sea.

Daedalus and Icarus would escape imprisonment by way of the sky. The inventor fashioned wings for himself and Icarus out of beeswax, string, and bird feathers.

The Myth of Icarus and Daedalus

Daedalus and his son Icarus escaped the maze by flying out of it. Daedalus warned Icarus not to fly too low because the sea foam would wet the feathers. The seafoam would loosen the wax, and he could fall. Icarus was also warned not to fly too high because the sun would melt the wax, and the wings would fall apart.

Once the father and son were clear of Crete, Icarus began joyfully swooping through the skies. In his excitement, Icarus did not heed his father’s warning and flew too close to the sun. The wax holding his wings together melted, and he plunged into the Aegean Sea and drowned.

Daedalus found the lifeless body of Icarus ashore on an island he named Icaria, where he buried his son. In the process, he was taunted by a partridge that looked suspiciously like the partridge into which Athena had transformed his nephew. Icarus’ death is interpreted as the gods’ retribution for the attempted murder of his nephew.

Grief-stricken, Daedalus continued his flight until he reached Italy. Upon reaching Sicily, Daedalus was welcomed by King Cocalus.

Daedalus and the Spiral Seashell

While in Sicily Daedalus built a temple to the god Apollo and hung up his wings as an offering.

King Minos did not forget Daedalus’ treachery. Minos scoured Greece trying to find him.

When Minos reached a new city or town, he would offer a reward in return for a riddle to be solved. Minos would present a spiral seashell and ask for a string to be run through it. Minos knew the only person who would be able to thread the string through the shell would be Daedalus.

When Minos arrived in Sicily, he approached King Cocalus with the shell. Cocalus gave the shell to Daedalus in secret. Of course, Daedalus solved the impossible puzzle. He tied the string to an ant and coerced the ant through the shell with honey.

When Cocalus presented the solved puzzle, Minos knew he had finally found Daedalus and demanded Cocalus turn Daedalus over to him to answer for his crime. Cocalus was not willing to give Daedalus to Minos. Instead, he hatched a plan to kill Minos in his chamber.

How Minos died is up for interpretation, with some stories stating Cocalus’ daughters murdered Minos in the bath by pouring boiling water over him. Others say he was poisoned, and some even suggest it was Daedalus himself who killed Minos.

After the death of King Minos, Daedalus continued to build and create wonders for the ancient world, until his death.

READ MORE: 7 Wonders of the Ancient World

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/daedalus/ ">Daedalus: The Ancient Greek Problem Solver </a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- News Releases

The math problem that took nearly a century to solve

UC San Diego mathematicians unlock the secret to Ramsey numbers

University of California - San Diego

Ramsey problems, such as r(4,5) are simple to state, but as shown in this graph, the possible solutions are nearly endless, making them very difficult to solve.

Credit: Jacques Verstraete / UC San Diego

We’ve all been there: staring at a math test with a problem that seems impossible to solve. What if finding the solution to a problem took almost a century? For mathematicians who dabble in Ramsey theory, this is very much the case. In fact, little progress had been made in solving Ramsey problems since the 1930s.

Now, University of California San Diego researchers Jacques Verstraete and Sam Mattheus have found the answer to r(4,t), a longstanding Ramsey problem that has perplexed the math world for decades.

What was Ramsey’s problem, anyway?

In mathematical parlance, a graph is a series of points and the lines in between those points. Ramsey theory suggests that if the graph is large enough, you’re guaranteed to find some kind of order within it — either a set of points with no lines between them or a set of points with all possible lines between them (these sets are called “cliques”). This is written as r(s,t) where s are the points with lines and t are the points without lines.

To those of us who don’t deal in graph theory, the most well-known Ramsey problem, r(3,3), is sometimes called “the theorem on friends and strangers” and is explained by way of a party: in a group of six people, you will find at least three people who all know each other or three people who all don’t know each other. The answer to r(3,3) is six.

“It’s a fact of nature, an absolute truth,” Verstraete states. “It doesn't matter what the situation is or which six people you pick — you will find three people who all know each other or three people who all don't know each other. You may be able to find more, but you are guaranteed that there will be at least three in one clique or the other.”

What happened after mathematicians found that r(3,3) = 6? Naturally, they wanted to know r(4,4), r(5,5), and r(4,t) where the number of points that are not connected is variable. The solution to r(4,4) is 18 and is proved using a theorem created by Paul Erdös and George Szekeres in the 1930s.

Currently r(5,5) is still unknown.

A good problem fights back

Why is something so simple to state so hard to solve? It turns out to be more complicated than it appears. Let’s say you knew the solution to r(5,5) was somewhere between 40-50. If you started with 45 points, there would be more than 10 234 graphs to consider!

“Because these numbers are so notoriously difficult to find, mathematicians look for estimations,” Verstraete explained. “This is what Sam and I have achieved in our recent work. How do we find not the exact answer, but the best estimates for what these Ramsey numbers might be?”

Math students learn about Ramsey problems early on, so r(4,t) has been on Verstraete’s radar for most of his professional career. In fact, he first saw the problem in print in Erdös on Graphs: His Legacy of Unsolved Problems, written by two UC San Diego professors, Fan Chung and the late Ron Graham. The problem is a conjecture from Erdös, who offered $250 to the first person who could solve it.

“Many people have thought about r(4,t) — it’s been an open problem for over 90 years,” Verstraete said. “But it wasn’t something that was at the forefront of my research. Everybody knows it's hard and everyone’s tried to figure it out, so unless you have a new idea, you’re not likely to get anywhere.”

Then about four years ago, Verstraete was working on a different Ramsey problem with a mathematician at the University of Illinois-Chicago, Dhruv Mubayi. Together they discovered that pseudorandom graphs could advance the current knowledge on these old problems.

In 1937, Erdös discovered that using random graphs could give good lower bounds on Ramsey problems. What Verstraete and Mubayi discovered was that sampling from pseudo random graphs frequently gives better bounds on Ramsey numbers than random graphs. These bounds — upper and lower limits on the possible answer — tightened the range of estimations they could make. In other words, they were getting closer to the truth.

In 2019, to the delight of the math world, Verstraete and Mubayi used pseudorandom graphs to solve r(3,t). However, Verstraete struggled to build a pseudorandom graph that could help solve r(4,t).

He began pulling in different areas of math outside of combinatorics, including finite geometry, algebra and probability. Eventually he joined forces with Mattheus, a postdoctoral scholar in his group whose background was in finite geometry.

“It turned out that the pseudorandom graph we needed could be found in finite geometry,” Verstraete stated. “Sam was the perfect person to come along and help build what we needed.”

Once they had the pseudorandom graph in place, they still had to puzzle out several pieces of math. It took almost a year, but eventually they realized they had a solution: r(4,t) is close to a cubic function of t . If you want a party where there will always be four people who all know each other or t people who all don’t know each other, you will need roughly t 3 people present. There is a small asterisk (actually an o) because, remember, this is an estimate, not an exact answer. But t 3 is very close to the exact answer.

The findings are currently under review with the Annals of Mathematics .

“It really did take us years to solve,” Verstraete stated. “And there were many times where we were stuck and wondered if we’d be able to solve it at all. But one should never give up, no matter how long it takes.”

Verstraete emphasizes the importance of perseverance — something he reminds his students of often. “If you find that the problem is hard and you're stuck, that means it's a good problem. Fan Chung said a good problem fights back. You can't expect it just to reveal itself.”

Verstraete knows such dogged determination is well-rewarded: “I got a call from Fan saying she owes me $250.”

Annals of Mathematics

10.4007/annals.2024.199.2.8

Method of Research

Experimental study

Article Title

The asymptotics of r(4,t)

Article Publication Date

Disclaimer: AAAS and EurekAlert! are not responsible for the accuracy of news releases posted to EurekAlert! by contributing institutions or for the use of any information through the EurekAlert system.

Original Source

- inspirko.org

Inspirational topics for a quality life.

Problem solving

Entertaining introduction.

Problem-solving is an essential skill that we use every day, whether we realize it or not. From fixing a broken bike to figuring out how to make a delicious meal with limited ingredients, problem-solving is at the core of our daily lives. But what exactly is problem-solving? It's the process of identifying a problem, developing a plan to solve it, and implementing that plan to reach a solution. And while it may sound straightforward, the reality is that problem-solving can be a tricky and sometimes frustrating process.

Imagine you're trying to bake a cake, but you realize you're missing an ingredient. You could throw in the towel and give up on the cake altogether, or you could think creatively and find a solution. Maybe you could substitute a similar ingredient or adjust the recipe to work without it. The ability to think critically and outside the box is essential for effective problem-solving, and it's a skill that can be developed with practice.

Problem-solving has been a part of human history for as long as we've existed. Our ancestors had to solve problems every day just to survive, from hunting for food to building shelter. Over time, we've developed more sophisticated methods of problem-solving, from the scientific method to design thinking. But even with all our technological advances, we still face new challenges that require innovative problem-solving.

In this text, we'll explore the fascinating world of problem-solving, from its history to its practical applications in everyday life. We'll also dive into the principles of effective problem-solving and debunk some common myths surrounding the topic. So buckle up and get ready to exercise your brain – because problem-solving is about to become your new favorite pastime.

Short History

As mentioned in the previous chapter, problem-solving has been a part of human history since the beginning. Our ancestors had to solve problems every day to survive, such as finding food and water, building shelter, and protecting themselves from predators. These early humans developed practical problem-solving skills based on trial and error, and they passed their knowledge down through the generations.

As civilizations developed, problem-solving became more complex. For example, ancient civilizations like the Greeks and Romans developed advanced systems for building structures, creating art, and governing their societies. The Greeks developed a method of inquiry called dialectic, which involved questioning and answering to arrive at the truth. The Romans developed a legal system that relied on solving disputes between individuals and groups.

In the Middle Ages, problem-solving continued to be important, particularly in the fields of mathematics and science. Many of the mathematical and scientific advancements made during this time laid the foundation for modern science and engineering. In the Renaissance, problem-solving became more focused on the arts, with artists like Leonardo da Vinci using their creativity to solve complex problems in fields like engineering, anatomy, and architecture.

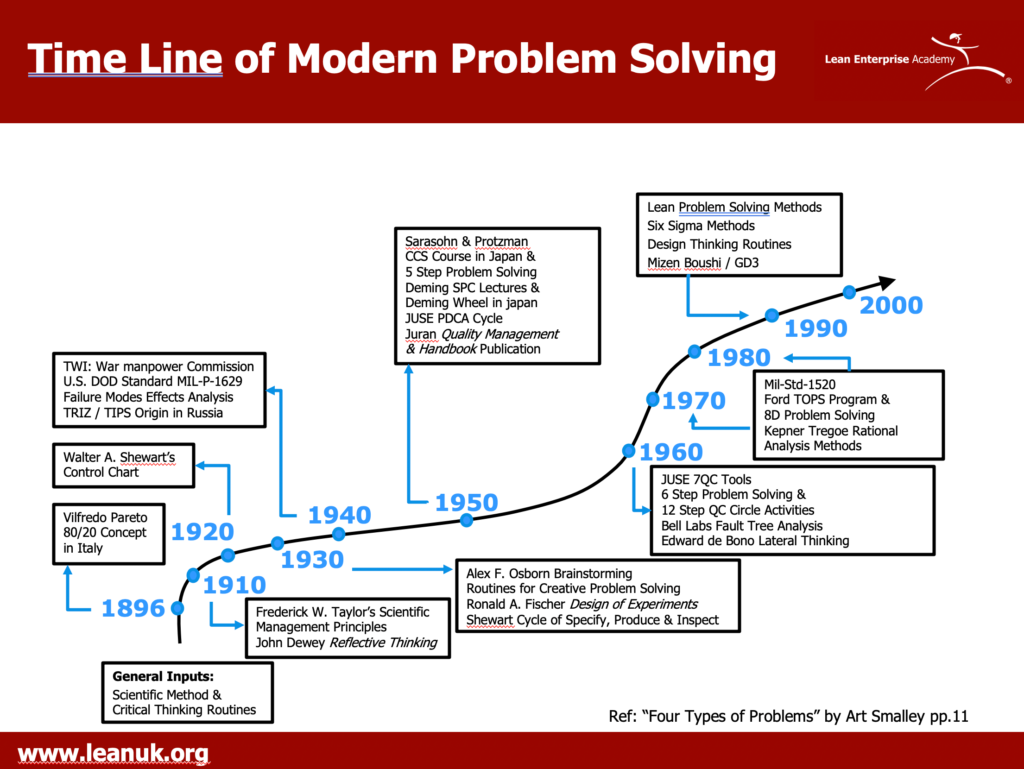

In the modern era, problem-solving has become even more crucial, as technology and globalization have made the world more complex and interconnected. Today, we face challenges like climate change, resource depletion, and social inequality, which require innovative problem-solving to address. Many fields, such as engineering, computer science, and business, have developed problem-solving methodologies, such as design thinking and lean startup, to help people tackle these complex challenges.

In short, problem-solving has been a fundamental part of human history and has evolved alongside the development of civilizations and societies. From our earliest ancestors to the present day, problem-solving has been essential to our survival and progress. And as we face new challenges in the future, we'll need to continue developing innovative problem-solving skills to overcome them.

Famous People

Throughout history, there have been many famous people who have made significant contributions to the field of problem-solving. These individuals have used their creativity, intelligence, and persistence to tackle some of the world's most complex problems and come up with innovative solutions. Here are just a few examples:

Thomas Edison - Edison is perhaps best known for inventing the light bulb, but he was also a prolific problem-solver who held over 1,000 patents in his lifetime. Edison famously said, "I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work," reflecting his perseverance in the face of challenges.

Albert Einstein - Einstein is one of the most famous scientists in history, known for his groundbreaking work in physics. He was also an excellent problem-solver, using his intuition and mathematical skills to make revolutionary discoveries about the nature of the universe.

Steve Jobs - Jobs was the co-founder of Apple and is credited with revolutionizing the personal computer, music, and mobile phone industries. He was a master problem-solver who believed that design thinking was the key to innovation and success.

Marie Curie - Curie was a pioneering physicist and chemist who made significant contributions to the field of radioactivity. She was also an excellent problem-solver, using her analytical skills to develop new scientific theories and techniques.

Elon Musk - Musk is a modern-day problem-solving genius, known for his work with Tesla, SpaceX, and other ventures. He has a reputation for thinking big and tackling audacious goals, like colonizing Mars and creating a high-speed transportation system.

These individuals and many others have shown that effective problem-solving requires creativity, persistence, and a willingness to take risks. They have tackled some of the world's most complex problems and come up with innovative solutions that have changed the course of history. Their examples show us that problem-solving is not just a practical skill, but also a powerful tool for innovation and progress.

Shocking Facts

Problem-solving is an essential skill that we use every day, but there are some surprising and shocking facts about problem-solving that many people are not aware of. Here are a few:

Most people are terrible at problem-solving - Studies have shown that most people struggle with even simple problem-solving tasks. In fact, only about 20% of the population is considered to be proficient in problem-solving.

Problem-solving ability declines with age - As we age, our problem-solving abilities tend to decline. This is due to changes in the brain and decreased cognitive function.

Lack of sleep can impair problem-solving ability - A lack of sleep can significantly impair our ability to solve problems. Studies have shown that people who are sleep-deprived make more errors and take longer to complete tasks that require problem-solving.

Stress can hinder problem-solving - While a certain amount of stress can be beneficial for problem-solving, too much stress can actually hinder our ability to think creatively and come up with solutions.

Our problem-solving ability is affected by our mindset - Our mindset can play a significant role in our ability to solve problems. People with a growth mindset, who believe that their abilities can be developed through hard work and perseverance, tend to be better problem-solvers than those with a fixed mindset, who believe that their abilities are predetermined and unchangeable.

These shocking facts highlight the importance of developing effective problem-solving skills and taking care of our mental and physical health to optimize our problem-solving ability. By understanding these factors, we can improve our problem-solving abilities and achieve greater success in our personal and professional lives.

Secrets of the Topic

While problem-solving may seem straightforward, there are some secrets to effective problem-solving that can help us achieve better results. Here are a few:

Break the problem down into smaller parts - When faced with a complex problem, it can be helpful to break it down into smaller, more manageable parts. This can help us better understand the problem and come up with more targeted solutions.

Use analogies and metaphors - Using analogies and metaphors can help us approach problems from a fresh perspective and generate new ideas. By comparing the problem to something else, we can often identify similarities and differences that we may not have otherwise noticed.

Ask the right questions - Asking the right questions is essential for effective problem-solving. By asking open-ended questions, we can encourage creative thinking and generate new ideas. It's also important to ask questions that help us better understand the problem and its underlying causes.

Use trial and error - While trial and error may not be the most efficient problem-solving method, it can be effective for complex problems with multiple solutions. By trying different approaches and learning from our mistakes, we can ultimately arrive at a solution that works.

Collaborate with others - Collaboration can be a powerful tool for problem-solving. By working with others, we can draw on their expertise and perspectives, and generate more creative solutions. It's important to cultivate a culture of collaboration and open communication to make the most of this approach.

By understanding these secrets of effective problem-solving, we can improve our ability to solve complex problems and achieve greater success in our personal and professional lives.

Effective problem-solving requires a set of principles to guide our approach. These principles are based on research and experience, and can help us approach problems in a structured and effective way. Here are a few key principles of effective problem-solving:

Define the problem - Before we can solve a problem, we need to define it clearly. This involves identifying the underlying issue, understanding its scope and impact, and clarifying our goals and objectives.

Generate multiple solutions - Effective problem-solving involves generating multiple potential solutions to a problem, rather than just one. This allows us to consider a range of options and choose the best one.

Evaluate the solutions - Once we have generated multiple solutions, we need to evaluate them based on a set of criteria, such as feasibility, impact, and cost. This helps us choose the best solution for the problem at hand.

Implement the solution - Once we have selected a solution, we need to implement it effectively. This may involve developing a plan, allocating resources, and communicating the solution to stakeholders.

Monitor and adjust - Effective problem-solving requires ongoing monitoring and adjustment. We need to track the progress of the solution, identify any issues or challenges that arise, and make adjustments as necessary.

By following these principles, we can approach problems in a structured and effective way, and achieve better results. These principles are applicable to a range of fields, from business and engineering to education and healthcare. By applying them consistently, we can develop our problem-solving skills and achieve greater success in our personal and professional lives.

Using the Topic to Improve Everyday Life

Effective problem-solving is not just about solving complex business or technical problems. It can also be used to improve our everyday lives. Here are some ways in which we can use problem-solving to improve our daily experiences:

Time management - Many of us struggle with managing our time effectively. By using problem-solving techniques, we can identify the root causes of our time management issues and develop effective strategies to address them.

Personal relationships - Relationships can be complex, and we often encounter problems that require creative solutions. By using problem-solving techniques, we can communicate more effectively, resolve conflicts, and strengthen our relationships.

Health and wellness - Many health and wellness issues, such as weight management and stress reduction, require effective problem-solving skills. By breaking down the problem into smaller parts and developing targeted solutions, we can improve our overall health and well-being.

Financial management - Financial management can be a challenge for many people. By using problem-solving techniques, we can identify areas where we can reduce expenses or increase income, and develop effective strategies to achieve our financial goals.

Personal growth - Effective problem-solving can also be used to facilitate personal growth and development. By identifying our strengths and weaknesses, setting goals, and developing action plans, we can achieve our full potential and live a more fulfilling life.

By applying problem-solving principles to our everyday lives, we can improve our overall quality of life and achieve greater success in all areas. Effective problem-solving is a versatile and valuable skill that can be used in virtually any context to achieve better results.

Practical Uses

Effective problem-solving has practical uses in a range of fields, from business to healthcare to education. Here are a few practical uses of problem-solving:

Business - Problem-solving is essential in the business world, where companies face complex challenges like market competition, changing customer needs, and financial constraints. Business leaders use problem-solving techniques to identify problems, generate solutions, and implement changes that improve performance and profitability.

Healthcare - Problem-solving is essential in healthcare, where medical professionals face complex diagnoses, treatment plans, and patient care issues. Healthcare professionals use problem-solving techniques to identify the underlying causes of health problems, develop effective treatment plans, and improve patient outcomes.

Education - Problem-solving is essential in education, where teachers and students face a range of challenges, from student engagement to curriculum design. Teachers use problem-solving techniques to identify areas where students are struggling, develop effective teaching strategies, and improve student performance.

Engineering - Problem-solving is essential in engineering, where engineers face complex design challenges, from building structures to developing new technologies. Engineers use problem-solving techniques to identify design issues, develop innovative solutions, and test and implement those solutions in real-world contexts.

Government - Problem-solving is essential in government, where policymakers face complex social and economic challenges, from reducing poverty to improving infrastructure. Government officials use problem-solving techniques to identify underlying issues, develop effective policies, and implement changes that improve outcomes for citizens.

These are just a few examples of the practical uses of problem-solving. Effective problem-solving is essential in virtually every field, and can be used to improve performance, productivity, and outcomes in a range of contexts.

Recommendations

Effective problem-solving requires a combination of knowledge, skills, and experience. Here are a few recommendations for improving your problem-solving abilities:

Develop your critical thinking skills - Critical thinking is an essential component of effective problem-solving. By developing your critical thinking skills, you can identify underlying issues, evaluate potential solutions, and make informed decisions.

Practice creative thinking - Creative thinking is essential for generating innovative solutions to complex problems. By practicing creative thinking techniques, such as brainstorming, mind mapping, and analogical thinking, you can develop your ability to think outside the box.

Build your knowledge base - Effective problem-solving requires a strong foundation of knowledge in the relevant field. By building your knowledge base through education, research, and practical experience, you can become more effective at identifying and solving problems.

Collaborate with others - Collaboration is a powerful tool for problem-solving. By working with others, you can draw on their expertise and perspectives, generate new ideas, and achieve better results.

Practice problem-solving in different contexts - Effective problem-solving requires adaptability and versatility. By practicing problem-solving in different contexts, you can develop your ability to apply problem-solving principles in a range of situations.

By following these recommendations, you can improve your problem-solving abilities and achieve greater success in your personal and professional life. Effective problem-solving is a valuable skill that can help you overcome challenges, achieve your goals, and make a positive impact on the world.

Effective problem-solving has many advantages, both personal and professional. Here are a few:

Improved decision-making - Effective problem-solving involves evaluating potential solutions and making informed decisions based on evidence and analysis. By developing your problem-solving abilities, you can become a better decision-maker in all areas of your life.

Increased efficiency - Effective problem-solving involves identifying and addressing underlying issues, which can lead to increased efficiency in personal and professional contexts. By addressing problems before they become larger issues, you can save time, resources, and energy.

Increased innovation - Effective problem-solving requires creativity and out-of-the-box thinking, which can lead to increased innovation in personal and professional contexts. By generating new ideas and approaches, you can improve your performance and achieve better results.

Improved teamwork - Effective problem-solving often requires collaboration and communication, which can lead to improved teamwork in personal and professional contexts. By working with others to identify and solve problems, you can develop stronger relationships and achieve better outcomes.

Improved self-confidence - Effective problem-solving requires persistence, resilience, and the ability to overcome obstacles. By developing your problem-solving abilities, you can improve your self-confidence and achieve greater success in all areas of your life.

These advantages highlight the importance of developing effective problem-solving skills. By becoming a better problem-solver, you can achieve better outcomes, overcome challenges, and make a positive impact on the world around you.

Disadvantages

While effective problem-solving has many advantages, there are also some potential disadvantages to consider. Here are a few:

Overthinking - Effective problem-solving involves analysis and evaluation, but too much of this can lead to overthinking. Overthinking can cause stress and anxiety, and can also lead to indecision and procrastination.

Analysis paralysis - Analysis paralysis is a type of overthinking that occurs when we become stuck in the analysis phase of problem-solving and struggle to make a decision or take action. This can lead to missed opportunities and wasted time.

Lack of creativity - Effective problem-solving requires creativity and innovative thinking, but some individuals may struggle with this aspect of problem-solving. A lack of creativity can lead to a limited range of solutions and missed opportunities for improvement.

Resistance to change - Effective problem-solving often requires change, which can be difficult for some individuals to accept. Resistance to change can limit the effectiveness of problem-solving efforts and lead to missed opportunities for improvement.

Resource constraints - Effective problem-solving often requires resources, such as time, money, and personnel. Resource constraints can limit the effectiveness of problem-solving efforts and lead to suboptimal solutions.

These disadvantages highlight the importance of being mindful of the potential downsides of problem-solving and taking steps to mitigate them. By balancing analysis and creativity, being open to change, and being mindful of resource constraints, we can overcome these potential disadvantages and achieve greater success in our problem-solving efforts.

Possibilities of Misunderstanding the Topic

While problem-solving may seem straightforward, there are some common misunderstandings that can lead to ineffective problem-solving. Here are a few possibilities of misunderstanding the topic:

Assuming there is only one solution - Effective problem-solving involves generating multiple potential solutions to a problem, rather than assuming there is only one correct answer. By considering a range of options, we can identify the best solution for the problem at hand.

Focusing on symptoms rather than underlying causes - Effective problem-solving requires us to identify the underlying causes of a problem, rather than just addressing the symptoms. By addressing the root cause of a problem, we can develop more targeted and effective solutions.

Ignoring potential biases - Effective problem-solving requires us to be aware of our biases and assumptions, which can influence our thinking and decision-making. By recognizing and addressing these biases, we can improve the quality of our problem-solving efforts.

Assuming a linear problem-solving process - Effective problem-solving is not always a linear process, and can involve a range of approaches, from trial and error to creative thinking. By being flexible and adaptive, we can achieve better results in our problem-solving efforts.

Overlooking the importance of implementation and monitoring - Effective problem-solving is not just about generating solutions, but also about implementing them effectively and monitoring their success. By tracking progress and making adjustments as necessary, we can ensure that our problem-solving efforts are effective and sustainable.

By understanding these possibilities of misunderstanding the topic, we can approach problem-solving in a more effective and nuanced way, and achieve better results. Effective problem-solving requires a combination of knowledge, skills, and experience, and by being mindful of these potential misunderstandings, we can improve our problem-solving abilities and achieve greater success in our personal and professional lives.

Controversy

While problem-solving is generally seen as a positive and necessary skill, there are some controversies surrounding its use in certain contexts. Here are a few examples:

In some industries, there is a focus on rapid problem-solving that may prioritize speed over accuracy. This can lead to rushed solutions that may not be effective in the long term.

Some people argue that problem-solving can be overused, and that individuals may rely too heavily on problem-solving techniques rather than using intuition or common sense.

There is debate over whether problem-solving is a skill that can be taught or if it is an innate ability. Some people argue that problem-solving is a learned skill that can be developed through practice, while others argue that some people are naturally better problem-solvers than others.

In some cases, problem-solving can be a source of stress or burnout, particularly in high-pressure environments where there is a constant need to identify and solve problems.

There is debate over the role of problem-solving in decision-making, and whether problem-solving should be the primary approach to decision-making or whether other approaches, such as intuition, should also be considered.

These controversies highlight the complexity and nuance of problem-solving as a skill. While problem-solving is generally seen as a positive and necessary skill, there are potential downsides and debates over its use in certain contexts. By being aware of these controversies, we can approach problem-solving in a more nuanced and informed way, and achieve better results.

Debunking Myths

There are some common myths surrounding problem-solving that can lead to ineffective or inefficient problem-solving efforts. Here are a few of these myths, and why they are not accurate:

Myth: There is only one correct solution to a problem. Reality: Effective problem-solving involves generating multiple potential solutions to a problem, and evaluating them based on a set of criteria to choose the best option.

Myth: Problem-solving is a linear process that always follows the same steps. Reality: Problem-solving can involve a range of approaches, from trial and error to creative thinking, and may require adaptation and flexibility based on the specific context and problem.

Myth: Effective problem-solving requires a high IQ or advanced education. Reality: While knowledge and experience can be helpful in effective problem-solving, problem-solving is a skill that can be developed through practice and effort.

Myth: Problem-solving always involves complex, technical problems. Reality: Problem-solving can be applied to a range of issues and challenges, from personal relationships to time management.

Myth: Problem-solving requires perfectionism and an aversion to risk-taking. Reality: Effective problem-solving involves taking calculated risks and being willing to make mistakes and learn from them.

By debunking these myths, we can approach problem-solving in a more effective and realistic way, and achieve better results. Effective problem-solving requires a combination of knowledge, skills, and experience, and by recognizing these common myths, we can improve our problem-solving abilities and achieve greater success in our personal and professional lives.

Other Points of Interest on This Topic

Effective problem-solving is a broad and multifaceted topic with many points of interest. Here are a few additional points of interest on this topic:

The role of emotional intelligence in effective problem-solving. Emotional intelligence, which involves the ability to recognize and manage emotions in oneself and others, can be an important factor in effective problem-solving.

The impact of culture on problem-solving approaches. Different cultures may have different problem-solving approaches, and understanding these differences can be important for effective problem-solving in a global context.

The role of technology in problem-solving. Technology, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, is increasingly being used to enhance problem-solving abilities and improve outcomes.

The relationship between problem-solving and innovation. Effective problem-solving is often a key component of innovation, and innovation can lead to improved problem-solving approaches and outcomes.

The importance of ethical considerations in problem-solving. Effective problem-solving requires consideration of ethical implications and potential consequences, and ethical decision-making should be a key consideration in problem-solving efforts.

These points of interest highlight the complexity and richness of effective problem-solving as a topic. By exploring these additional areas of interest, we can develop a deeper understanding of problem-solving and improve our abilities to solve problems in a range of contexts.

Subsections of This Topic

Effective problem-solving is a vast topic that encompasses many different subtopics and approaches. Here are a few examples of the different subsections of problem-solving:

Root cause analysis - Root cause analysis is a problem-solving approach that involves identifying the underlying cause of a problem and addressing it directly, rather than just treating the symptoms.

Creative thinking - Creative thinking is a problem-solving approach that involves generating new and innovative solutions to a problem, often through techniques like brainstorming and analogical thinking.

Design thinking - Design thinking is a problem-solving approach that involves a human-centered, iterative process of problem-solving that emphasizes empathy, collaboration, and experimentation.

Lean problem-solving - Lean problem-solving is a problem-solving approach that involves eliminating waste and inefficiencies in a process or system, often through the use of tools like the Kaizen method.

Six Sigma - Six Sigma is a problem-solving approach that involves using data and statistical analysis to identify and eliminate defects and improve performance.

By understanding these different subsections of problem-solving, we can develop a more nuanced and effective approach to problem-solving in a range of contexts. Each subsection offers a unique set of tools and approaches that can be used to identify and solve problems more effectively and efficiently.

Effective problem-solving is an essential skill for success in both personal and professional contexts. By developing our problem-solving abilities, we can overcome challenges, achieve our goals, and make a positive impact on the world around us.

Throughout this article, we have explored various aspects of effective problem-solving, including its history, famous problem-solvers, principles, advantages, and disadvantages. We have also discussed some of the myths and controversies surrounding problem-solving, as well as some of the different subsections of the topic.

Ultimately, effective problem-solving requires a combination of knowledge, skills, and experience. By developing our critical and creative thinking skills, building our knowledge base, collaborating with others, and practicing problem-solving in different contexts, we can become more effective problem-solvers and achieve greater success in our personal and professional lives.

Effective problem-solving is not always easy, and there may be challenges and setbacks along the way. But by being mindful of the potential misunderstandings, controversies, and downsides of problem-solving, we can approach this important skill in a more nuanced and effective way, and achieve better outcomes.

In conclusion, effective problem-solving is a skill that can be developed and honed with practice and effort. By being mindful of the various aspects of problem-solving and continuously working to improve our abilities, we can become more effective problem-solvers and achieve greater success in all areas of our lives.

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

- 3 Questions: How history helps us solve today's issues

3 Questions: How history helps us solve today's issues

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

Science and technology are essential tools for innovation, and to reap their full potential, we also need to articulate and solve the many aspects of today’s global issues that are rooted in the political, cultural, and economic realities of the human world. With that mission in mind, MIT's School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences has launched The Human Factor — an ongoing series of stories and interviews that highlight research on the human dimensions of global challenges. Contributors to this series also share ideas for cultivating the multidisciplinary collaborations needed to solve the major civilizational issues of our time.

Malick Ghachem is an attorney and a professor of history at MIT who explores questions of slavery and abolition, criminal law, and constitutional history. He is the author of "The Old Regime and the Haitian Revolution" (Cambridge University Press, 2012), a history of the law of slavery in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) between 1685 and 1804. He teaches courses on the Age of Revolution, slavery and abolition, American criminal justice, and other topics. MIT SHASS Communications recently asked him to share his thoughts on how history can help people craft more effective public policies for today's world. Q: Your new research focuses on economic globalization and political protest in Haiti, a country with a complex social, political, and economic history. What lessons can we learn from Haiti's history that can inform more effective public policies? A: I think the most important lesson for public policy may be that we cannot ignore the distant past — and in the case of Haiti, by "distant past" I mean only so far back as the 18th century. (With apologies to colleagues who study the yet more distant centuries of ancient and medieval history!) Public policy has a short-term memory, however, and this is especially true of economic policy, which tends to look back only so far as the early 20th century to understand, for example, how a financial crisis comes about and what it entails.

Haiti showcases the decisive present-day impact and legacies of a history that goes back more than 300 years, to the rise of the slave plantation system. My current work tells the story of a planter rebellion in the 1720s against the French Indies Company, an event that ended the era of slave-trading monopolies in Saint-Domingue (as Haiti was known under French rule) and left large-scale sugar planters in effective control of the colony.

Some of the key political and social cleavages that have characterized Haitian life ever since date back to this period. A history of Haiti that begins with the revolutionary years leading up to Haitian independence in 1804, or any period thereafter, will necessarily lack a handle on just how deeply rooted are Haiti’s current circumstances.

We can see this on any number of levels. Colonial history continues to hamper prospects for broad-based education in Haiti, as my colleague Michel DeGraff’s work on the linguistic politics of French vs. Haitian Kreyòl powerfully demonstrates. The environment is another example. Part of the resistance to accepting the reality of climate change (whether in Haiti or elsewhere) is a reluctance to acknowledge that history in this deep sense matters. Yet it is clear that deforestation in Haiti begins no later than the 17th century, when French settlers began using trees for purposes of lumber and fuel. By the time of Haiti’s independence, the lack of forest cover had already left many parts of the country vulnerable to flooding.

That historical perspective, in turn, suggests one of the difficulties that besets even the most well-intentioned relief work in Haiti today. Such work tends to focus on repairing the immediate damage caused by the latest “natural” catastrophe, whether an earthquake, a hurricane-induced flood, or an outbreak of contagious disease. These tragedies rightly call upon the generous aid of first-responders, but after the sense of emergency passes, the eyes of the world often turn elsewhere.

An understanding of how these tragedies draw on the full weight of Haitian history encourages and even demands a longer-term commitment to the problems at hand. And it suggests that effective responses to what seem like essentially medical, environmental, or legal problems must cut across conventional categories of policy analysis and understandings of responsibility. Take the case of United Nations liability for the cholera outbreak in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake.

The natural impulse of human rights lawyers in that context was to file suit against the U.N., which then spent several years digging in its heels and denying its role in the outbreak. But the U.N.’s position in Haiti is a legacy of the much deeper impact that individual nations/states — most notably, France and the United States — have had on Haitian affairs over the course of three centuries. Framing responsibility in narrowly legal or chronological terms runs head-on into this reality and limits rather than expands our sense of the potential remedies.

Q: What connections do you see between economic conditions (including globalization and monetary policy) and the ability of a people or a culture to make innovations in science, technology, and public policy?

A: Waking up hungry each morning does not leave one with great deal of energy for scientific (or any other kind of) work during the day. The resources that make possible scientific and technological innovation are the same ones that sustain the relatively high standard of daily living many of us enjoy in the United States.

Haiti’s economy has long existed in a state of colonial dependency upon one or another foreign power; today it is the United States. The country’s economy is also beset by many woes, among them an ongoing currency crisis that makes the Haitian gourde an increasingly ineffective form of money. This fact places a premium on access to U.S. dollars, which elites and companies enjoy at the expense of workers paid in the local currency.

This is a crisis of sovereignty that takes the form of a monetary crisis. The earliest such currency crisis dates back (again) to the 1720s, and it’s one dimension of my current research. One of the two key triggers of the revolt against the Indies Company was a suspicion that the Company intended to eliminate the use of local Spanish silver coins, on which most colonists depended for their livelihood. The lack of a reliable and stable currency remained a problem throughout the colonial period and continues to severely constrict the economic horizons of many Haitians today.

Q: As MIT President Reif has said, solving the great challenges of our time will require multidisciplinary problem-solving — bringing together expertise and ideas from the sciences, technology, the social sciences, arts, and humanities. Can you share why you believe it is critical for any effort to address the well-being of human populations, and the planet itself, to incorporate tools and perspectives from the field of history? Also, what challenges do you see to multi-disciplinary collaborations — and how can we overcome them?

A: President Reif’s observation is correct and important. We also need to appreciate that, even within the world of the social sciences and the humanities, there are deep and abiding differences about how best to understand and implement public policy.

Let’s take the case of development economics. There is a growing literature, associated mostly with political economy and the new institutional economics, that seeks to explain the disparities in wealth and income between more and less “developed” nations. These works tend to suggest that there is a unifying model, theory, or historical pattern that accounts for the disparities: political corruption, institutional competence, the rule of law, protection of private property, etc. These phenomena are all important, but the particular forms they take can really only be understood on a case-by-case basis.

It’s important to do the unglamorous, nitty-gritty, heavily historical work of understanding the local and the particular — which requires much more patience that even those social scientists who speak of “path dependence” tend to exhibit. I believe that this kind of sustained patience for understanding the local in historical contexts is itself a tool of public policy, a way of seeing and talking about the world, and (if wielded correctly) an instrument of power and justice.

One of the principal ways historians can contribute to problem-solving work at MIT and elsewhere is by helping to identify what the real problem is in the first place. When we can understand and articulate the roots and sources of a problem, we have a much better chance of solving it.

Interview prepared by MIT SHASS Communications Editorial team: Kathryn O'Neill, Emily Hiestand (series editor)

Share this news article on:, related links.

- Malick Ghachem

- MIT History

- Online course: (21H.319) Race, Crime, and Citizenship in American Law

- Book: "The Old Regime and the Haitian Revolution"

- Article: "Election Insights: Malick Ghachem on Criminal Justice Reform"

- Article: "Black Histories Matter"

Related Topics

- International development

- Education, teaching, academics

Related Articles

Analyzing the 2016 election: Insights from 12 MIT scholars

SHASS welcomes six new faculty members

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

A faster, better way to prevent an AI chatbot from giving toxic responses

Read full story →

Has remote work changed how people travel in the US?

Physicist Netta Engelhardt is searching black holes for universal truths

MIT community members gather on campus to witness 93 percent totality

Extracting hydrogen from rocks

When an antibiotic fails: MIT scientists are using AI to target “sleeper” bacteria

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

Unable to find any suggestions for your query...

The Essex website uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are consenting to their use. Please visit our cookie policy to find out which cookies we use and why. View cookie policy.

How historians can help with current and future issues

Improving how history is used in current thinking and decision-making

Historians have much to offer when it comes to helping inform society how to deal with the issues of today and the future. But they need to be open to taking their research and expertise in unexpected directions to address these priorities.

Here, Dr Alix Green highlights the great value historians can offer through collaboration and explains how her engagement with business archivists is helping business leaders understand how looking at their past can help then in the future.

Is history just old news, irrelevant to the issues of the present and future? When researchers get together to talk about problem-solving or meeting the grand challenges of today’s society, historians are rarely considered as serious contributors. But people use history all the time – it’s how we make sense of the world, from the incidental stuff of everyday life to major decisions of international consequence (think war, peace and Brexit).

So, what if we took this human habit of ‘thinking with history’ seriously? Could we help improve the process, make it more informed, rigorous – and useful? The idea that historical training makes for sound political judgement goes back to the foundations of the academic discipline in the late nineteenth century. As J.R. Seeley, the first Regius Professor of History at Cambridge, put it in 1870: “If [history] is an important study to every citizen, it is the one important study to the legislator and ruler.” More recently, historians have used examples such as the Cuban Missile Crisis, Suez and Iraq as case studies of political leaders using, abusing or ignoring history.

The need to collaborate

While historians may lament that policymakers are rarely receptive to their advice, perhaps we also need to question our model of engagement. Given that history is part of how people reason and make decisions, surely we need to work with them to understand that process – rather than telling them what they should or shouldn’t be thinking?

In other words, we have to collaborate. We have to be interested not (just) in a historical topic but in how and why that topic matters for a present-day group or organisation. We have to be open to taking our research in unexpected directions in response to our collaborators’ needs, to shape a project through genuine dialogue, to ask questions of the sources that advance our agenda as scholars but also help our partners address their priorities.

Some historians have been engaged in this kind of close collaboration for decades, usually not with leaders and public figures but with local community groups, charities and museums: public engagement at the level of lived experience. This work doesn’t get much attention, recognition or reward but it’s no less meaningful in terms of knowledge deepened, skills sharpened and experience gained.

Thinking with history more effectively

I think we can build on this model. We can collaborate not just on producing historical outputs, such as exhibitions, films or tours, but also on improving how history is used in those processes of thinking and decision-making.

So, what does this look like?

Business archives hold a wealth of business intelligence, irreplicable and unique to the organisation. Business archivists can identify how the collections under their care could inform the present-day work of the company and help their colleagues ‘think with history’ more effectively. But, working alone or in small teams and with limited budgets, they usually don’t have the capacity to do so.

This is where collaboration with a historian can help. I recently worked with the John Lewis Partnership Heritage Centre on a project looking at the history of the company’s pay policy , a topic that the Heritage Services Manager, Judy Faraday, and I co-designed through extensive dialogue with the Personnel Leadership Team (PLT). Presenting our findings was not just about sharing historical insights. We had two larger goals. The first was to enlarge the frame of reference for executive thinking. As one PLT member commented, the work helped them to be “braver… having courage in what we’ve managed to achieve previously will really start to influence the context in which we make decisions”.

Demonstrating the value of archives

Our second goal was to demonstrate the value of the archives to the company. “In the past the role of the archive has always been very reactive,” Judy explained. The project proved there was a different way of working, with the business archivist “very much in the driving seat when it comes to linking up the agenda of the business with the academic research that can be undertaken”. This shift in the balance of power allowed the archives to position itself more effectively as a business resource.

Co-designed projects in history could work in all kinds of settings and organisations, but there’s a broader point to be made about academics doing public engagement, too often a tick-box exercise or a token effort. Yes, we do need to share our work with wider audiences in the conventional sense and, for some research, that linear model is entirely appropriate. There are many opportunities, however, to work differently. With “engagement” a truly two-way process of conversation and collaboration – beginning at the very earliest stages of research design – there is surely greater potential for influencing, shaping and transforming how knowledge is produced, interpreted and applied in the world beyond the university.

Historians, along with our colleagues in the humanities, have much to offer a whole range of partners and audiences – our expertise complements that of other professions and academic disciplines. But we also need to step forward more confidently as public scholars and make that case for our engagement.

About the Author:

Dr Alix Green

Senior Lecturer, University of Essex

Related posts

Turning around the lives of young people

Dr Jo Barton

05 December 2019

Categories: Public Engagement, Research

The research impact agenda: driven by suspicion?

Dr Geoff Cole

13 February 2020

- Course Finder

- Undergraduate study

- Postgraduate study

- Short courses and CPD

- International students

- Study online

- Apprenticeships

- Summer Schools

- Essex living

- Essex Sport

- Colchester Campus

- Southend Campus

- Loughton Campus

- Student facilities

- Student services

- Research excellence

- Research showcase

- Media requests

- Research Excellence Framework (REF)

- Research institutes and centres

- Departments

- How to pay your fees

- General - [email protected]

- Undergraduate - [email protected]

- Postgraduate - [email protected]

- +44 (0) 1206 873333

- University of Essex

- Wivenhoe Park

- Colchester CO4 3SQ

- Accessibility

- Our privacy statements

- Our transparency return

- Modern slavery and human trafficking

7 Great Creative Thinkers in History

Creativity can be an advantage in every field of work, not just the arts. Here’s our list of some of the best creative thinkers from history for their innovative and curious nature.

Thomas Edison

An icon for innovation with a collection of patents for over 1,000 inventions. His approach towards joint thinking collaborating with other innovators and always thinking positive came to light in his work and problem solving thinking.

“I have not failed, I have just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” – Thomas Edison

Isaac Newton

Greater knowledge came from Newtons achievements and understanding in science, finding inspiration from his home life surroundings and a now famous yet simple apple tree.

“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” – Isaac Newton

Walt Disney

He built an entertainment empire by turning his dreams and goals into reality, through ’Imagineering’ his own term combining imagination and engineering.

“It’s kind of fun to do the impossible.” – Walt Disney

Walt Disney isn’t the only one who is known for animation take a look at our award nominated animation.

Albert Einstein

He constantly challenged notions not only his own but those that came before him, to reach revolutionary new ideas.

“Logic will get you from A to B. Imagination will take you everywhere.” – Albert Einstein

An entrepreneur and visionary in technology changing the way people use computers in their everyday lives introducing the personal computer revolution introducing the ipod, iphone and ipad. He was an innovator funding the creation of pixar, initiating a development in the visual effects industry with the first computer-animated film.

“Creativity is just connecting things.” – Steve Jobs

Marie Curie

The first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person and only woman to win a Nobel Prize twice in two different fields. She paved the way for women in science with her discoveries and breakthrough ideas. Her determination and dedication had a profound effect on her work and ultimately her life.

“Be less curious about people and more curious about ideas.” - Marie Curie

Leonardo Di Vinci

An inventor, painter, sculptor, scientist, architect, mathematician, anatomist, writer and engineer. Considered to be one of the best talented painters of all time his sketches, notes and scientific diagrams shows his forward thinking mentality with inventions for flight, musical instruments and mechanical engineering.

“Learning never exhausts the mind.” – Leonardo Di Vinci

Feeling inspired? Check out our services to see how we can help your company be more creative.

Spread the word, share the love, pass it on. If you like this article, feel free to share using the handy link below.

Wanna get in touch?

Creative Director

More from Think!

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By clicking "Accept", you agree to our use of cookies.

- Forgot your Password?

First, please create an account

Problem solving like a historian.

- Introduction

- Secondary Sources

- Primary Sources

- Sources in Action

before you start Why do you think it’s important to study past economic challenges in U.S. history?

1. Introduction

We often hear about “the economy” in the news as if it’s a mysterious and unpredictable force in our lives, but an economy is simply a system of how money changes hands and how goods and services are bought and sold. The economy is an essential part of society, so understanding what it is and how it impacts our daily lives allows us to adapt to economic changes using agility and problem solving.

In this challenge, we’ll explore present-day economic concerns by relating them to economic crises in U.S. history and exploring possible preparations and solutions. We will examine past economic downturns—the Great Recession of 2008, the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Energy Crisis of the early 1970s, and the bursting of the dot-com bubble in the early 2000s—to understand how they affected people’s lives and how people survived them. Those who lived through these particularly challenging times had to be agile—adaptable, resourceful, and quick-thinking—to support themselves and their families through economic hardship.

As an important step in looking to the past to find solutions in the present, we’ll also examine how historians approach problem solving by using reliable sources to inform their solutions. And like historians, we too will learn how to evaluate potential sources to make sure they’re both trustworthy and closely related to what we’re investigating. Evaluating a source allows you to understand and apply information more effectively, making the source a powerful tool for problem solving.

Economy The system according to which money is acquired and spent and goods and services are bought and sold. Economic Crisis A sudden downturn in the financial health of a country, usually due to a decrease in production, an increase in unemployment, or uncontrolled inflation or deflation.

2. Problem Solving like a Historian

Historians also use their problem solving skill to find answers to questions they have about the past. But historians solve problems in a particular way: they investigate sources that contain information about the topic they’re studying so they can come up with the best possible answers.

Problem solving like a historian means using relevant and reliable information to come up with the best solution you can. Let’s look at some of the sources historians use when they investigate the past.

A historical source is a document or other item that provides information about the past. Historians use sources to answer questions about the past and, in some cases, to apply what they’ve learned to the future. Sources help paint a picture of an event and provide insights into how people thought and acted at the time.

- Primary sources are objects that were created at the time being studied.

- Secondary sources are created at a later date.