Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples

What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples

Published on February 4, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

A case-control study is an experimental design that compares a group of participants possessing a condition of interest to a very similar group lacking that condition. Here, the participants possessing the attribute of study, such as a disease, are called the “case,” and those without it are the “control.”

It’s important to remember that the case group is chosen because they already possess the attribute of interest. The point of the control group is to facilitate investigation, e.g., studying whether the case group systematically exhibits that attribute more than the control group does.

Table of contents

When to use a case-control study, examples of case-control studies, advantages and disadvantages of case-control studies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions.

Case-control studies are a type of observational study often used in fields like medical research, environmental health, or epidemiology. While most observational studies are qualitative in nature, case-control studies can also be quantitative , and they often are in healthcare settings. Case-control studies can be used for both exploratory and explanatory research , and they are a good choice for studying research topics like disease exposure and health outcomes.

A case-control study may be a good fit for your research if it meets the following criteria.

- Data on exposure (e.g., to a chemical or a pesticide) are difficult to obtain or expensive.

- The disease associated with the exposure you’re studying has a long incubation period or is rare or under-studied (e.g., AIDS in the early 1980s).

- The population you are studying is difficult to contact for follow-up questions (e.g., asylum seekers).

Retrospective cohort studies use existing secondary research data, such as medical records or databases, to identify a group of people with a common exposure or risk factor and to observe their outcomes over time. Case-control studies conduct primary research , comparing a group of participants possessing a condition of interest to a very similar group lacking that condition in real time.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Case-control studies are common in fields like epidemiology, healthcare, and psychology.

You would then collect data on your participants’ exposure to contaminated drinking water, focusing on variables such as the source of said water and the duration of exposure, for both groups. You could then compare the two to determine if there is a relationship between drinking water contamination and the risk of developing a gastrointestinal illness. Example: Healthcare case-control study You are interested in the relationship between the dietary intake of a particular vitamin (e.g., vitamin D) and the risk of developing osteoporosis later in life. Here, the case group would be individuals who have been diagnosed with osteoporosis, while the control group would be individuals without osteoporosis.

You would then collect information on dietary intake of vitamin D for both the cases and controls and compare the two groups to determine if there is a relationship between vitamin D intake and the risk of developing osteoporosis. Example: Psychology case-control study You are studying the relationship between early-childhood stress and the likelihood of later developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Here, the case group would be individuals who have been diagnosed with PTSD, while the control group would be individuals without PTSD.

Case-control studies are a solid research method choice, but they come with distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of case-control studies

- Case-control studies are a great choice if you have any ethical considerations about your participants that could preclude you from using a traditional experimental design .

- Case-control studies are time efficient and fairly inexpensive to conduct because they require fewer subjects than other research methods .

- If there were multiple exposures leading to a single outcome, case-control studies can incorporate that. As such, they truly shine when used to study rare outcomes or outbreaks of a particular disease .

Disadvantages of case-control studies

- Case-control studies, similarly to observational studies, run a high risk of research biases . They are particularly susceptible to observer bias , recall bias , and interviewer bias.

- In the case of very rare exposures of the outcome studied, attempting to conduct a case-control study can be very time consuming and inefficient .

- Case-control studies in general have low internal validity and are not always credible.

Case-control studies by design focus on one singular outcome. This makes them very rigid and not generalizable , as no extrapolation can be made about other outcomes like risk recurrence or future exposure threat. This leads to less satisfying results than other methodological choices.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

A case-control study differs from a cohort study because cohort studies are more longitudinal in nature and do not necessarily require a control group .

While one may be added if the investigator so chooses, members of the cohort are primarily selected because of a shared characteristic among them. In particular, retrospective cohort studies are designed to follow a group of people with a common exposure or risk factor over time and observe their outcomes.

Case-control studies, in contrast, require both a case group and a control group, as suggested by their name, and usually are used to identify risk factors for a disease by comparing cases and controls.

A case-control study differs from a cross-sectional study because case-control studies are naturally retrospective in nature, looking backward in time to identify exposures that may have occurred before the development of the disease.

On the other hand, cross-sectional studies collect data on a population at a single point in time. The goal here is to describe the characteristics of the population, such as their age, gender identity, or health status, and understand the distribution and relationships of these characteristics.

Cases and controls are selected for a case-control study based on their inherent characteristics. Participants already possessing the condition of interest form the “case,” while those without form the “control.”

Keep in mind that by definition the case group is chosen because they already possess the attribute of interest. The point of the control group is to facilitate investigation, e.g., studying whether the case group systematically exhibits that attribute more than the control group does.

The strength of the association between an exposure and a disease in a case-control study can be measured using a few different statistical measures , such as odds ratios (ORs) and relative risk (RR).

No, case-control studies cannot establish causality as a standalone measure.

As observational studies , they can suggest associations between an exposure and a disease, but they cannot prove without a doubt that the exposure causes the disease. In particular, issues arising from timing, research biases like recall bias , and the selection of variables lead to low internal validity and the inability to determine causality.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-control-study/

Schlesselman, J. J. (1982). Case-Control Studies: Design, Conduct, Analysis (Monographs in Epidemiology and Biostatistics, 2) (Illustrated). Oxford University Press.

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is an observational study | guide & examples, control groups and treatment groups | uses & examples, cross-sectional study | definition, uses & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Asthma & Allergies

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Breast Cancer

- Cardiovascular Health

- Environment & Sustainability

- Exercise & Fitness

- Headache & Migraine

- Health Equity

- HIV & AIDS

- Human Biology

- Men's Health

- Mental Health

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Parkinson's Disease

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Sexual Health

- Ulcerative Colitis

- Women's Health

- Nutrition & Fitness

- Vitamins & Supplements

- At-Home Testing

- Men’s Health

- Women’s Health

- Latest News

- Medical Myths

- Honest Nutrition

- Through My Eyes

- New Normal Health

- 2023 in medicine

- Why exercise is key to living a long and healthy life

- What do we know about the gut microbiome in IBD?

- My podcast changed me

- Can 'biological race' explain disparities in health?

- Why Parkinson's research is zooming in on the gut

- Health Hubs

- Find a Doctor

- BMI Calculators and Charts

- Blood Pressure Chart: Ranges and Guide

- Breast Cancer: Self-Examination Guide

- Sleep Calculator

- RA Myths vs Facts

- Type 2 Diabetes: Managing Blood Sugar

- Ankylosing Spondylitis Pain: Fact or Fiction

- Our Editorial Process

- Content Integrity

- Conscious Language

- Health Conditions

- Health Products

What is a case-control study in medical research?

A case-control study is a type of medical research investigation often used to help determine the cause of a disease, particularly when investigating a disease outbreak or rare condition.

If public health scientists want a quick and easy way to highlight clues about the cause of a new disease outbreak, they can compare two groups of people: Cases, the term for people who already have the disease, and controls, or people not affected by the disease.

Other terms used to describe case-control studies include epidemiological, retrospective, and observational.

What is a case-control study?

A case-control study is a way of carrying out a medical investigation to confirm or indicate what is likely to have caused a condition.

They are usually retrospective, meaning that the researchers look at past data to test whether a particular outcome can be linked back to a suspected risk factor and prevent further outbreaks.

Prospective case-control studies are less common. These involve enrolling a specific selection of people and following that group while monitoring their health. Cases emerge as people who develop the disease or condition under investigation as the study progresses. Those unaffected by the disease form the control group.

To test for specific causes, the scientists need to create a hypothesis about possible causes of the outbreak or disease. These are known as risk factors.

They compare how often the people in the group of cases had been exposed to the suspected cause against how often members of the control group had been exposed. If more participants in the case group experience the risk factor, this suggests that it is a likely cause of the disease.

Researchers might also uncover likely risk factors not mentioned in their hypothesis by studying the medical and personal histories of the people in each group. A pattern may emerge that links the condition to certain factors.

If a specific risk factor has already been identified for a disease or condition, such as age, sex, smoking, or eating red meat, the researchers can use statistical methods to adjust the study to account for that risk factor, helping them to identify other possible risk factors more easily.

Case-control research is a vital tool used by epidemiologists, or researchers who look into the factors affecting health and illness of populations.

Just one risk factor could be investigated for a particular outcome. A good example of this is to compare the number people with lung cancer who have a history of smoking with the number who do not. This will indicate the link between lung cancer and smoking.

Why is it useful?

There are multiple reasons for the use of case-control studies.

Relatively quick and easy

Case-control studies are usually based on past data, so all of the necessary information is readily available, making them quick to carry out. Scientists can analyze existing data to look at health events that have already happened and risk factors that have already been observed.

A retrospective case-control study does not require scientists to wait and see what happens in a trial over a period of days, weeks, or years.

The fact that the data is already available for collation and analysis means that a case-control study is useful when quick results are desired, perhaps when clues are sought for what is causing a sudden disease outbreak.

A prospective case-control study may also be helpful in this scenario as researchers can collect data on suspected risk factors while they monitor for new cases.

The time-saving advantage offered by case-control studies also means they are more practical than other scientific trial designs if the exposure to a suspected cause occurs a long time before the outcome of a disease.

For example, if you wanted to test the hypothesis that a disease seen in adulthood is linked to factors occurring in young children, a prospective study would take decades to carry out. A case-control study is a far more feasible option.

Does not need large numbers of people

Numerous risk factors can be evaluated in case-control studies since they do not require large numbers of participants to be statistically meaningful. More resources can be dedicated to the analysis of fewer people.

Overcomes ethical challenges

As case-control studies are observational and usually about people who have already experienced a condition, they do not pose the ethical problems seen with some interventional studies.

For example, it would be unethical to deprive a group of children of a potentially lifesaving vaccine to see who developed the associated disease. However, analyzing a group of children with limited access to that vaccine can help determine who is at most risk of developing the disease, as well as helping to guide future vaccination efforts.

Limitations

While a case-control study can help to test a hypothesis about the link between a risk factor and an outcome, it is not as powerful as other types of study in confirming a causal relationship.

Case-control studies are often used to provide early clues and inform further research using more rigorous scientific methods.

The main problem with case-control studies is that they are not as reliable as planned studies that record data in real time, because they look into data from the past.

The main limitations of case-control studies are:

‘Recall bias’

When people answer questions about their previous exposure to certain risk factors their ability to recall may be unreliable. Compared to people not affected by a condition, individuals with a certain disease outcome may be more likely to recall a certain risk factor, even if it did not exist, because of a temptation to make their own subjective links to explain their condition.

This bias may be reduced if data about the risk factors – exposure to certain drugs, for example – had been entered into reliable records at the time. But this may not be possible for lifestyle factors, for example, because they are usually investigated by questionnaire.

An example of recall bias is the difference between asking study participants to recall the weather at the time of the onset of a certain symptom, versus an analysis of scientifically measured weather patterns around the time of a formal diagnosis.

Finding a measurement of exposure to a risk factor in the body is another way of making case-control studies more reliable and less subjective. These are known as biomarkers. For example, researchers may look at results of blood or urine tests for evidence of a specific drug, rather than asking a participant about drug use.

Cause and effect

An association found between a disease and a possible risk does not necessarily mean one factor directly caused the other.

In fact, a retrospective study can never definitively prove that a link represents a definite cause, as it is not an experiment. There are, though, questions that can be used to test the likelihood of a causal relationship, such as the extent of the association or whether there is a ‘dose response’ to increasing exposure to the risk factor.

One way of illustrating the limitations of cause-and-effect is to look at associations found between a cultural factor and a particular health effect. The cultural factor itself, such as a certain type of exercise, may not be causing the outcome if the same cultural group of cases shares another plausible common factor, such as a certain food preference.

Some risk factors are linked to others. Researchers have to take into account overlaps between risk factors, such as leading a sedentary lifestyle, being depressed, and living in poverty.

If researchers conducting a retrospective case-control study find an association between depression and weight gain over time, for example, they cannot say with any certainty that depression is a risk factor for weight gain without bringing in a control group containing people who follow a sedentary lifestyle.

‘Sampling bias’

The cases and controls selected for study may not truly represent the disease under investigation.

An example of this occurs when cases are seen in a teaching hospital, a highly specialized setting compared with most settings in which the disease may occur. The controls, too, may not be typical of the population. People volunteering their data for the study may have a particularly high level of health motivation.

Other limitations

There are other limitations to case-control studies. While they are good for studying rare conditions, as they do not require large groups of participants, they are less useful for examining rare risk factors, which are more clearly indicated by cohort studies.

Finally, case-control studies cannot confirm different levels or types of the disease being investigated. They can look at only one outcome because a case is defined by whether they did or did not have the condition.

Last medically reviewed on May 16, 2018

- Public Health

- Clinical Trials / Drug Trials

- Pharma Industry / Biotech Industry

How we reviewed this article:

- Introduction to study designs – case-control studies. (n.d.) https://www.healthknowledge.org.uk/e-learning/epidemiology/practitioners/introduction-study-design-ccs

- Mann, C. J. (2003). Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional , and case-control studies. Emergency Medicine Journal, 20 , 54-60 http://emj.bmj.com/content/emermed/20/1/54.full.pdf

- Prospective vs. retrospective studies. (n.d.) https://www.statsdirect.com/help/default.htm#basics/prospective.htm

Share this article

Latest news

- High blood pressure during middle age could increase dementia risk

- Is prescribing beta-blockers following a heart attack necessary?

- Early-onset cancer: Faster biological aging may be driving rates in young adults

- Weight-loss drugs like Wegovy may help treat heart failure in diabetes, obesity

- A 'balanced' diet is better than a vegetarian one in supporting brain health

Related Coverage

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are a reliable type of research. Medical experts base guidelines for the best medical treatments on them.

A randomized controlled trial is one of the best ways of keeping the bias of the researchers out of the data and making sure that a study gives the…

Another year has come and gone, and we are about to step into a new decade. But what have the past 12 months meant for medical research?

Clinical trials are carried out to ensure that medical practices and treatments are safe and effective. People with a health condition may choose to…

The past 12 months have seen discoveries, breakthroughs, and innovations in medical research. MNT take you on a journey through 2017's highlights.

- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

Case-control and Cohort studies: A brief overview

Posted on 6th December 2017 by Saul Crandon

Introduction

Case-control and cohort studies are observational studies that lie near the middle of the hierarchy of evidence . These types of studies, along with randomised controlled trials, constitute analytical studies, whereas case reports and case series define descriptive studies (1). Although these studies are not ranked as highly as randomised controlled trials, they can provide strong evidence if designed appropriately.

Case-control studies

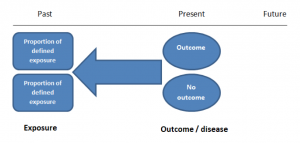

Case-control studies are retrospective. They clearly define two groups at the start: one with the outcome/disease and one without the outcome/disease. They look back to assess whether there is a statistically significant difference in the rates of exposure to a defined risk factor between the groups. See Figure 1 for a pictorial representation of a case-control study design. This can suggest associations between the risk factor and development of the disease in question, although no definitive causality can be drawn. The main outcome measure in case-control studies is odds ratio (OR) .

Figure 1. Case-control study design.

Cases should be selected based on objective inclusion and exclusion criteria from a reliable source such as a disease registry. An inherent issue with selecting cases is that a certain proportion of those with the disease would not have a formal diagnosis, may not present for medical care, may be misdiagnosed or may have died before getting a diagnosis. Regardless of how the cases are selected, they should be representative of the broader disease population that you are investigating to ensure generalisability.

Case-control studies should include two groups that are identical EXCEPT for their outcome / disease status.

As such, controls should also be selected carefully. It is possible to match controls to the cases selected on the basis of various factors (e.g. age, sex) to ensure these do not confound the study results. It may even increase statistical power and study precision by choosing up to three or four controls per case (2).

Case-controls can provide fast results and they are cheaper to perform than most other studies. The fact that the analysis is retrospective, allows rare diseases or diseases with long latency periods to be investigated. Furthermore, you can assess multiple exposures to get a better understanding of possible risk factors for the defined outcome / disease.

Nevertheless, as case-controls are retrospective, they are more prone to bias. One of the main examples is recall bias. Often case-control studies require the participants to self-report their exposure to a certain factor. Recall bias is the systematic difference in how the two groups may recall past events e.g. in a study investigating stillbirth, a mother who experienced this may recall the possible contributing factors a lot more vividly than a mother who had a healthy birth.

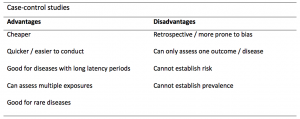

A summary of the pros and cons of case-control studies are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of case-control studies.

Cohort studies

Cohort studies can be retrospective or prospective. Retrospective cohort studies are NOT the same as case-control studies.

In retrospective cohort studies, the exposure and outcomes have already happened. They are usually conducted on data that already exists (from prospective studies) and the exposures are defined before looking at the existing outcome data to see whether exposure to a risk factor is associated with a statistically significant difference in the outcome development rate.

Prospective cohort studies are more common. People are recruited into cohort studies regardless of their exposure or outcome status. This is one of their important strengths. People are often recruited because of their geographical area or occupation, for example, and researchers can then measure and analyse a range of exposures and outcomes.

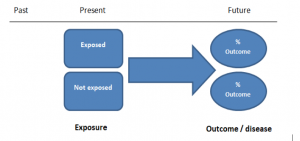

The study then follows these participants for a defined period to assess the proportion that develop the outcome/disease of interest. See Figure 2 for a pictorial representation of a cohort study design. Therefore, cohort studies are good for assessing prognosis, risk factors and harm. The outcome measure in cohort studies is usually a risk ratio / relative risk (RR).

Figure 2. Cohort study design.

Cohort studies should include two groups that are identical EXCEPT for their exposure status.

As a result, both exposed and unexposed groups should be recruited from the same source population. Another important consideration is attrition. If a significant number of participants are not followed up (lost, death, dropped out) then this may impact the validity of the study. Not only does it decrease the study’s power, but there may be attrition bias – a significant difference between the groups of those that did not complete the study.

Cohort studies can assess a range of outcomes allowing an exposure to be rigorously assessed for its impact in developing disease. Additionally, they are good for rare exposures, e.g. contact with a chemical radiation blast.

Whilst cohort studies are useful, they can be expensive and time-consuming, especially if a long follow-up period is chosen or the disease itself is rare or has a long latency.

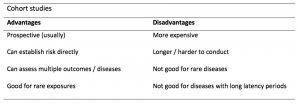

A summary of the pros and cons of cohort studies are provided in Table 2.

The Strengthening of Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement (STROBE)

STROBE provides a checklist of important steps for conducting these types of studies, as well as acting as best-practice reporting guidelines (3). Both case-control and cohort studies are observational, with varying advantages and disadvantages. However, the most important factor to the quality of evidence these studies provide, is their methodological quality.

- Song, J. and Chung, K. Observational Studies: Cohort and Case-Control Studies . Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.  2010 Dec;126(6):2234-2242.

- Ury HK. Efficiency of case-control studies with multiple controls per case: Continuous or dichotomous data . Biometrics . 1975 Sep;31(3):643–649.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies.  Lancet 2007 Oct;370(9596):1453-14577. PMID: 18064739.

Saul Crandon

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

No Comments on Case-control and Cohort studies: A brief overview

Very well presented, excellent clarifications. Has put me right back into class, literally!

Very clear and informative! Thank you.

very informative article.

Thank you for the easy to understand blog in cohort studies. I want to follow a group of people with and without a disease to see what health outcomes occurs to them in future such as hospitalisations, diagnoses, procedures etc, as I have many health outcomes to consider, my questions is how to make sure these outcomes has not occurred before the “exposure disease”. As, in cohort studies we are looking at incidence (new) cases, so if an outcome have occurred before the exposure, I can leave them out of the analysis. But because I am not looking at a single outcome which can be checked easily and if happened before exposure can be left out. I have EHR data, so all the exposure and outcome have occurred. my aim is to check the rates of different health outcomes between the exposed)dementia) and unexposed(non-dementia) individuals.

Very helpful information

Thanks for making this subject student friendly and easier to understand. A great help.

Thanks a lot. It really helped me to understand the topic. I am taking epidemiology class this winter, and your paper really saved me.

Happy new year.

Wow its amazing n simple way of briefing ,which i was enjoyed to learn this.its very easy n quick to pick ideas .. Thanks n stay connected

Saul you absolute melt! Really good work man

am a student of public health. This information is simple and well presented to the point. Thank you so much.

very helpful information provided here

really thanks for wonderful information because i doing my bachelor degree research by survival model

Quite informative thank you so much for the info please continue posting. An mph student with Africa university Zimbabwe.

Thank you this was so helpful amazing

Apreciated the information provided above.

So clear and perfect. The language is simple and superb.I am recommending this to all budding epidemiology students. Thanks a lot.

Great to hear, thank you AJ!

I have recently completed an investigational study where evidence of phlebitis was determined in a control cohort by data mining from electronic medical records. We then introduced an intervention in an attempt to reduce incidence of phlebitis in a second cohort. Again, results were determined by data mining. This was an expedited study, so there subjects were enrolled in a specific cohort based on date(s) of the drug infused. How do I define this study? Thanks so much.

thanks for the information and knowledge about observational studies. am a masters student in public health/epidemilogy of the faculty of medicines and pharmaceutical sciences , University of Dschang. this information is very explicit and straight to the point

Very much helpful

Subscribe to our newsletter

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

Cluster Randomized Trials: Concepts

This blog summarizes the concepts of cluster randomization, and the logistical and statistical considerations while designing a cluster randomized controlled trial.

Expertise-based Randomized Controlled Trials

This blog summarizes the concepts of Expertise-based randomized controlled trials with a focus on the advantages and challenges associated with this type of study.

An introduction to different types of study design

Conducting successful research requires choosing the appropriate study design. This article describes the most common types of designs conducted by researchers.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples

What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples

Published on 4 February 2023 by Tegan George .

A case-control study is an experimental design that compares a group of participants possessing a condition of interest to a very similar group lacking that condition. Here, the participants possessing the attribute of study, such as a disease, are called the ‘case’, and those without it are the ‘control’.

It’s important to remember that the case group is chosen because they already possess the attribute of interest. The point of the control group is to facilitate investigation, e.g., studying whether the case group systematically exhibits that attribute more than the control group does.

Table of contents

When to use a case-control study, examples of case-control studies, advantages and disadvantages of case-control studies, frequently asked questions.

Case-control studies are a type of observational study often used in fields like medical research, environmental health, or epidemiology. While most observational studies are qualitative in nature, case-control studies can also be quantitative , and they often are in healthcare settings. Case-control studies can be used for both exploratory and explanatory research , and they are a good choice for studying research topics like disease exposure and health outcomes.

A case-control study may be a good fit for your research if it meets the following criteria.

- Data on exposure (e.g., to a chemical or a pesticide) are difficult to obtain or expensive.

- The disease associated with the exposure you’re studying has a long incubation period or is rare or under-studied (e.g., AIDS in the early 1980s).

- The population you are studying is difficult to contact for follow-up questions (e.g., asylum seekers).

Retrospective cohort studies use existing secondary research data, such as medical records or databases, to identify a group of people with a common exposure or risk factor and to observe their outcomes over time. Case-control studies conduct primary research , comparing a group of participants possessing a condition of interest to a very similar group lacking that condition in real time.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Case-control studies are common in fields like epidemiology, healthcare, and psychology.

You would then collect data on your participants’ exposure to contaminated drinking water, focusing on variables such as the source of said water and the duration of exposure, for both groups. You could then compare the two to determine if there is a relationship between drinking water contamination and the risk of developing a gastrointestinal illness. Example: Healthcare case-control study You are interested in the relationship between the dietary intake of a particular vitamin (e.g., vitamin D) and the risk of developing osteoporosis later in life. Here, the case group would be individuals who have been diagnosed with osteoporosis, while the control group would be individuals without osteoporosis.

You would then collect information on dietary intake of vitamin D for both the cases and controls and compare the two groups to determine if there is a relationship between vitamin D intake and the risk of developing osteoporosis. Example: Psychology case-control study You are studying the relationship between early-childhood stress and the likelihood of later developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Here, the case group would be individuals who have been diagnosed with PTSD, while the control group would be individuals without PTSD.

Case-control studies are a solid research method choice, but they come with distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of case-control studies

- Case-control studies are a great choice if you have any ethical considerations about your participants that could preclude you from using a traditional experimental design .

- Case-control studies are time efficient and fairly inexpensive to conduct because they require fewer subjects than other research methods .

- If there were multiple exposures leading to a single outcome, case-control studies can incorporate that. As such, they truly shine when used to study rare outcomes or outbreaks of a particular disease .

Disadvantages of case-control studies

- Case-control studies, similarly to observational studies, run a high risk of research biases . They are particularly susceptible to observer bias , recall bias , and interviewer bias.

- In the case of very rare exposures of the outcome studied, attempting to conduct a case-control study can be very time consuming and inefficient .

- Case-control studies in general have low internal validity and are not always credible.

Case-control studies by design focus on one singular outcome. This makes them very rigid and not generalisable , as no extrapolation can be made about other outcomes like risk recurrence or future exposure threat. This leads to less satisfying results than other methodological choices.

A case-control study differs from a cohort study because cohort studies are more longitudinal in nature and do not necessarily require a control group .

While one may be added if the investigator so chooses, members of the cohort are primarily selected because of a shared characteristic among them. In particular, retrospective cohort studies are designed to follow a group of people with a common exposure or risk factor over time and observe their outcomes.

Case-control studies, in contrast, require both a case group and a control group, as suggested by their name, and usually are used to identify risk factors for a disease by comparing cases and controls.

A case-control study differs from a cross-sectional study because case-control studies are naturally retrospective in nature, looking backward in time to identify exposures that may have occurred before the development of the disease.

On the other hand, cross-sectional studies collect data on a population at a single point in time. The goal here is to describe the characteristics of the population, such as their age, gender identity, or health status, and understand the distribution and relationships of these characteristics.

Cases and controls are selected for a case-control study based on their inherent characteristics. Participants already possessing the condition of interest form the “case,” while those without form the “control.”

Keep in mind that by definition the case group is chosen because they already possess the attribute of interest. The point of the control group is to facilitate investigation, e.g., studying whether the case group systematically exhibits that attribute more than the control group does.

The strength of the association between an exposure and a disease in a case-control study can be measured using a few different statistical measures , such as odds ratios (ORs) and relative risk (RR).

No, case-control studies cannot establish causality as a standalone measure.

As observational studies , they can suggest associations between an exposure and a disease, but they cannot prove without a doubt that the exposure causes the disease. In particular, issues arising from timing, research biases like recall bias , and the selection of variables lead to low internal validity and the inability to determine causality.

Sources for this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2023, February 04). What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-control-studies/

Schlesselman, J. J. (1982). Case-Control Studies: Design, Conduct, Analysis (Monographs in Epidemiology and Biostatistics, 2) (Illustrated). Oxford University Press.

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is an observational study | guide & examples, control groups and treatment groups | uses & examples, cross-sectional study | definitions, uses & examples.

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

The shaded area indicates the upper and lower limits of the 95% CIs.

DOAC indicates direct oral anticoagulant; IRR, incidence rate ratio; and VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

eMethods 1. Interaction

eMethods 2. Time-Conditional Propensity Score-Matched Analysis

eFigure. Flowchart of Patient Selection in Study Cohort and Case-Control Selection

eTable 1. ICD-10 Codes Used to Define Major Bleeding

eTable 2. Crude and Adjusted IRRs of Major Bleeding Associated With the Continuous Duration of Concomitant Use of SSRIs With OACs, Compared With OAC Use Alone

eTable 3. Crude and Adjusted IRRs of Major Bleeding Associated With Concomitant Use of SSRIs With OACs, Stratified by Age, Sex, History of Bleeding, and History of Chronic Kidney Disease

eTable 4. Crude and Adjusted IRRs of Major Bleeding Associated With Concomitant Use of Strong and Moderate SSRIs With OACs

eTable 5. Crude and Adjusted IRRs of Any Bleeding Associated With Concomitant Use of SSRIs With OACs, Compared With OAC Use Alone

eTable 6. Assessment of Additive and Multiplicative Interaction Between SSRIs and OACs, With Respect to Major Bleeding

eTable 7. Crude and Adjusted IRRs of Major Bleeding Associated With Concomitant Use of SSRIs With OACs, Varying the Exposure Assessment Window

eTable 8. Crude and Adjusted IRRs of Major Bleeding Associated With Concomitant Use of SSRIs With OACs, With Covariates Measured Prior to Cohort Entry

eTable 9. Crude and Adjusted IRRs of Major Bleeding Associated With Concomitant Use of SSRIs With OACs, After Multiple Imputation of Missing BMI and Smoking Values

eTable 10. Crude and Adjusted IRRs of Major Bleeding Associated With Concomitant Use of SSRIs With OACs, Compared With OAC Use Alone, by Type of OAC and Excluding Patients With Valvular AF

eTable 11. Adjusted HRs of Major Bleeding Associated With Concomitant Use of SSRIs With OACs Compared With OAC Use Alone, in a Time-Conditional Propensity Score-Matched Analysis

eTable 12. Crude and Adjusted IRRs of Major Bleeding Associated With Concomitant Use of SSRIs With OACs, With Adjustment for Additional Comedications Interacting With OACs

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Rahman AA , Platt RW , Beradid S , Boivin J , Rej S , Renoux C. Concomitant Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors With Oral Anticoagulants and Risk of Major Bleeding. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e243208. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3208

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Concomitant Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors With Oral Anticoagulants and Risk of Major Bleeding

- 1 Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

- 2 Centre for Clinical Epidemiology, Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

- 3 Department of Pediatrics, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

- 4 Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

- 5 Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

- 6 Department of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Question Is there an association between concomitant use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and oral anticoagulants (OACs) and the risk of major bleeding among patients with atrial fibrillation compared with OAC use alone?

Findings In this nested case-control study comprising 42 190 cases with major bleeding matched to 1 156 641 controls, concomitant SSRI and OAC use was associated with a 33% increased risk of major bleeding compared with OAC use alone; this risk was highest in the first few months of concomitant use and was substantially lower after 6 months.

Meaning This study suggests that concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs may be a risk factor for bleeding and should be closely monitored, particularly within the initial months of treatment.

Importance Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed antidepressants associated with a small increased risk of major bleeding. However, the risk of bleeding associated with the concomitant use of SSRIs and oral anticoagulants (OACs) has not been well characterized.

Objectives To assess whether concomitant use of SSRIs with OACs is associated with an increased risk of major bleeding compared with OAC use alone, describe how the risk varies with duration of use, and identify key clinical characteristics modifying this risk.

Design, Setting, and Participants A population-based, nested case-control study was conducted among patients with atrial fibrillation initiating OACs between January 2, 1998, and March 29, 2021. Patients were from approximately 2000 general practices in the UK contributing to the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. With the use of risk-set sampling, for each case of major bleeding during follow-up, up to 30 controls were selected from risk sets defined by the case and matched on age, sex, cohort entry date, and follow-up duration.

Exposures Concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs (direct OACs and vitamin K antagonists [VKAs]) compared with OAC use alone.

Main Outcomes and Measures The main outcome was incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of hospitalization for bleeding or death due to bleeding.

Results There were 42 190 patients with major bleeding (mean [SD] age, 74.2 [9.3] years; 59.8% men) matched to 1 156 641 controls (mean [SD] age, 74.2 [9.3] years; 59.8% men). Concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs was associated with an increased risk of major bleeding compared with OACs alone (IRR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.24-1.42). The risk peaked during the initial months of treatment (first 30 days of use: IRR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.37-2.22) and persisted for up to 6 months. The risk did not vary with age, sex, history of bleeding, chronic kidney disease, and potency of SSRIs. An association was present both with concomitant use of SSRIs and direct OACs compared with direct OAC use alone (IRR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.12-1.40) and concomitant use of SSRIs and VKAs compared with VKA use alone (IRR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.25-1.47).

Conclusions and Relevance This study suggests that among patients with atrial fibrillation, concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs was associated with an increased risk of major bleeding compared with OAC use alone, requiring close monitoring and management of risk factors for bleeding, particularly in the first few months of use.

Antidepressant medications are among the most frequently prescribed class of drugs worldwide, with up to 19% of individuals aged 60 years or older in the US reporting use of an antidepressant over the past 30 days. 1 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most widely used antidepressant medications and are often recommended over other classes of antidepressants for the treatment of major depressive disorder due to their comparable efficacy and favorable safety profile. 2 , 3 However, SSRIs have been shown to increase the risk of major bleeding, 4 - 14 possibly owing to their inhibition of platelet activation during hemostasis. 2 Although the absolute risk remains low for most individuals who use SSRIs, 11 , 12 , 15 coprescription with drugs such as oral anticoagulants (OACs) may be consequential. Concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs is common given the prevalence of mental health disorders. 16

Some observational studies have assessed the association between concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs and the risk of major bleeding. However, some had notable limitations, including exposure misclassification, 17 possible informative censoring, 18 , 19 residual confounding, 19 - 21 and limited statistical power. 20 , 22 - 24 Gaps in evidence that may inform the coprescription of SSRIs and OACs include whether the risk varies with demographic or clinical characteristics or between direct OACs (DOACs) and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs). In addition, data on the risk of specific types of major bleeding are limited. 25

To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted a population-based, nested case-control study to assess whether the concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs was associated with the risk of major bleeding compared with OAC use alone among patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). We also assessed whether the risk varied by duration of use, relevant demographic and other risk factors, potency of SSRIs, and OAC type.

In this population-based, nested case-control study, we used the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD GOLD and Aurum databases), a large primary care database of electronic medical records that contains demographic and lifestyle information, medical diagnoses, prescriptions, and referrals for more than 60 million patients from more than 2000 general practices. 26 , 27 These data are representative of the UK population in terms of age, sex, and race and ethnicity. 26 , 27 Drug prescriptions issued by the general practitioner are automatically recorded at the time of prescription. 26 , 27 Quality control audits of the CPRD are regularly conducted to ensure the accuracy and completeness of data. 26 , 27 The CPRD was linked with the Hospital Episodes Statistics repository, which contains details of inpatient and day case admissions, 28 and the Office for National Statistics database, which contains electronic death certificates. 29 The study protocol was approved by the CPRD Research Data Governance (No. 22_001906) and the Research Ethics Board of the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal, Canada, which also waived the need for patient informed consent as the data were deidentified. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( STROBE ) reporting guideline. 30

We conducted a population-based study with a nested case-control approach to analysis because of its computational efficiency compared with a full-cohort analysis given the time-varying nature of both medications of interest, the size of the cohort, and the long duration of follow-up. 31 We first identified all patients aged 18 years or older with an incident diagnosis of AF between January 2, 1998, and March 29, 2021, and at least 1 year of registration with the practice before AF diagnosis. From this base cohort, we selected those with a prescription for an OAC (apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, rivaroxaban, or warfarin) after AF diagnosis, with the date of first prescription defined as study cohort entry. We excluded patients who received OACs any time before cohort entry or SSRIs 6 months prior to cohort entry. We also excluded patients with hyperthyroidism in the year prior to cohort entry because AF in association with hyperthyroidism rarely requires long-term oral anticoagulation. Patients meeting these criteria were followed up until a first major bleeding event, death, end of registration with the practice, or end of the study period (March 29, 2021), whichever occurred first.

We identified cases as patients with a first recorded diagnosis of major bleeding during follow-up, defined as hospitalization with a primary diagnosis of major bleeding or death with bleeding as the primary cause, using relevant International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision ( ICD-10 ) codes (eTable 1 in Supplement 1 ); elective hospitalizations were not considered. ICD-10 codes for bleeding have shown good positive predictive values between 81% and 95%. 32 - 34 The index date was the date of hospital admission. For each case, we randomly selected up to 30 controls among the cohort members from the risk sets defined by the case. Each risk set, at each case’s index date, included all individuals who did not experience major bleeding and thus were still at risk up to that point in follow-up time, matched on age, sex, calendar date of cohort entry (±6 months), and duration of follow-up. Thus, as per the risk-set sampling approach, cases were eligible for selection as controls prior to becoming a case, and patients may have been selected as controls for multiple cases. 35 , 36 The index date for controls was the date resulting in the same duration of follow-up for cases and controls.

We identified prescriptions of SSRIs (citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, or sertraline) and OACs for all cases and their matched controls between cohort entry and the index date. Exposure was defined in 4 mutually exclusive categories: concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs, OAC use alone, nonuse, and other use. We considered patients as concomitant users of SSRIs and OACs if the duration of their last prescription for both medications covered or ended 30 days before the index date. Similarly, we considered patients as users of OACs alone if their last prescription for an OAC covered or ended 30 days before the index date, without a prescription for an SSRI in this period—this was the reference category. Users of SSRIs alone, non-SSRI antidepressants alone, or non-SSRI antidepressants concomitantly with SSRIs and/or OACs were classified separately (other use). Finally, nonusers were those not exposed to any medications of interest on or 30 days before the index date.

We adjusted all models for the following comorbidities based on substantive knowledge, measured at or earlier than 365 days (1 year) before the index date: smoking, alcohol abuse, body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) (<25, 25-29.9, or ≥30.0), depression, hypertension, diabetes, stroke or transient ischemic attack, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, disorders of hemostasis, cancer (other than nonmelanoma skin cancer), liver disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anemia, and venous thromboembolism. We also included history of bleeding at any time before cohort entry and the time between incident AF diagnosis and first OAC prescription. Diabetes and hypertension were defined using diagnostic codes or relevant medications. All models were also adjusted for use of the following drugs measured between 365 days (1 year) and 730 days (2 years) prior to the index date: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, thiazide diuretics, other diuretics, antiplatelets, lipid-lowering drugs (including statins), antipsychotics, non-SSRI antidepressants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitors, and H 2 receptor blockers. We considered the number of hospitalizations in the year before cohort entry as a surrogate marker for overall health. Finally, we adjusted for socioeconomic status using the Index of Multiple Deprivation, categorized in deciles. 37

We used conditional logistic regression to compute odds ratios of major bleeding associated with concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs compared with OAC use alone, adjusting for the covariates listed. In a nested case-control approach, odds ratios are unbiased estimators of incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with very limited loss in precision. 36 In secondary analyses, we assessed whether the risk of major bleeding varied according to age, sex, chronic kidney disease, history of bleeding, type of OAC (DOACs or VKAs), and potency of SSRIs (strong or moderate serotonin reuptake inhibitors based on the dissociation constant). 38 Next, among patients continuously exposed to OACs and concomitantly exposed to SSRIs and OACs at the index date, we investigated whether the risk of major bleeding varied with the duration of continuous concomitant use of SSRIs in 3 prespecified categories (≤30 days, 31-180 days, or >180 days) compared with OAC use alone. These categories were selected because SSRIs were reported to exert antiplatelet action as early as 2 to 3 weeks after initiation. 39 , 40 We defined continuous exposure to SSRIs and OACs separately, allowing a 30-day grace period between consecutive prescriptions where patients were still considered exposed. Patients were then considered concomitant users on any given day if exposed to both drugs on that day. In addition, we used a restricted cubic spline with 5 interior knots to produce a smooth curve of the IRR as a function of continuous duration of use. We also estimated the risk in specific anatomical locations, including gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage, and other major bleeding. We assessed the risk of any bleeding associated with concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs. For this analysis, we repeated the selection of cases and controls already described, with cases defined using relevant diagnostic codes in primary electronic medical records. Finally, we assessed whether an interaction was present between SSRIs and OACs with respect to the risk of major bleeding on both the additive and multiplicative scales (eMethods 1 in Supplement 1 ). In other words, we assessed whether the joint association of the 2 exposures departed from the sum or product of their individual associations with the risk of bleeding, although an additive interaction has been described as most indicative of biological or mechanistic interaction. 41 , 42

We performed 4 sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the results. First, to explore potential exposure misclassification, we considered only prescriptions that covered the index date and, next, those that covered or ended within 15 days before the index date. Second, to account for the potential adjustment for covariates affected by exposure, all covariates were measured at or prior to cohort entry. Third, we implemented multiple imputation by chained equations for missing values of BMI and smoking, combining results from 5 imputed datasets. 43 Fourth, we repeated the analysis by type of OAC, excluding patients with a history of valvular surgery or rheumatic valvular disease before cohort entry because DOACs are not indicated for patients with valvular AF. 44 - 46

We conducted a supplementary time-conditional propensity score–matched analysis to further explore the potential for residual confounding. 47 , 48 In brief, among the base cohort of patients with incident AF initiating OACs, we matched each patient initiating SSRIs to a patient using OACs alone up to that point in time with the same age (±1 year), sex, calendar date of OAC initiation (±1 year), and time-conditional propensity score (eMethods 2 in Supplement 1 ). Finally, we conducted a post hoc analysis, repeating the primary analysis with additional adjustment for the following comedications reported to interact with OACs, measured between 1 and 2 years before the index date: clarithromycin, erythromycin, penicillin, azole antifungals, quinidine, amiodarone, dronedarone, propafenone, allopurinol, oral corticosteroids, tamoxifen, valproic acid, cyclosporin, tacrolimus, disulfiram, methylphenidate, and sulfamethoxazole. All analyses were performed with a 2-sided hypothesis test, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant, without adjustment for multiple comparisons, using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

After applying all eligibility criteria, the cohort included 331 305 patients (mean [SD] age, 73.7 [10.8] years; 57.1% men) with incident AF initiating OACs (eFigure in Supplement 1 ). During a mean (SD) follow-up of 4.6 (4.0) years, 42 391 patients were hospitalized with major bleeding, yielding an incidence rate of 27.9 per 1000 person-years (95% CI, 27.7-28.2 per 1000 person-years). Among those, 42 190 cases (mean [SD] age, 74.2 [9.3] years; 59.8% men) were matched to 1 156 641 controls (mean [SD] age, 74.2 [9.3] years; 59.8% men). As anticipated, risk factors for major bleeding were more prevalent among cases than controls ( Table 1 ).

Concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs was associated with an increased risk of major bleeding compared with OAC use alone (IRR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.24-1.42) ( Table 2 ). The risk was the highest during the first 30 days of continuous use (IRR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.37-2.22), and decreased thereafter (eTable 2 in Supplement 1 ). This trend was also observed when modeling the IRR flexibly as a spline of the duration of continuous use ( Figure 1 ). The risk did not vary according to age, sex, history of major bleeding, chronic kidney disease ( Figure 2 ; eTable 3 in Supplement 1 ), or potency of SSRIs (eTable 4 in Supplement 1 ). The risk of major bleeding was associated with concomitant use of SSRIs and DOACs compared with DOACs alone (IRR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.12-1.40) and with concomitant use of SSRIs and VKAs compared with VKAs alone (IRR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.25-1.47) ( Table 3 ). With respect to types of major bleeding, the association was present for intracranial hemorrhage, gastrointestinal bleeding, and other major bleeding ( Table 2 ). Last, concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs was also associated with the risk of any bleeding (IRR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.16-1.28) compared with OAC use alone (eTable 5 in Supplement 1 ).

In the assessment of interaction, a small superadditive interaction may have been present, although the estimate was not statistically significant (relative excess risk due to interaction [RERI], 0.10; 95% CI, −0.07 to 0.27) (eTable 6 in Supplement 1 ). Based on the estimated RERI, the interaction may be associated with approximately 5% of all major bleeding. In addition, there was limited evidence of a multiplicative interaction. Results from sensitivity analyses were consistent with those of the primary analysis (eTables 7-10 in Supplement 1 ). Finally, the association remained in the time-conditional propensity score–matched analysis, although slightly attenuated (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.08-1.40) (eTable 11 in Supplement 1 ), and was consistent in the post hoc analysis (eTable 12 in Supplement 1 ).

In this population-based, nested case-control study, the concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs was associated with a 33% increased risk of major bleeding. The association was the strongest for the first few months of concomitant use. The overall risk remained consistent regardless of age, sex, potency of SSRIs, history of major bleeding, or chronic kidney disease as well as type of OAC. Concomitant use was individually associated with gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage, and other major bleeding. Interaction between SSRIs and OACs, if any, was limited.

In light of these findings, the risk of major bleeding may be a pertinent safety consideration for patients using SSRIs and OACs concomitantly. This finding has been echoed in the summary of product characteristics for different OACs, which describes SSRIs as interacting drugs given that they independently increase the risk of bleeding. Although clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder have acknowledged the risk of bleeding associated with SSRIs, the potential for interaction with OACs was either not discussed or based on very limited evidence. 49 , 50 Likewise, guidelines from Canadian, US, and European cardiology associations for the management of AF suggest consideration of drug-drug interactions when prescribing OACs, 44 - 46 with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs being the only class of drugs cited. 45 Although the European Heart Rhythm Association lists SSRIs as drugs with pharmacodynamic interactions with DOACs, no evidence was cited. 51

The risk of major bleeding associated with the concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs has been assessed in previous observational studies, although results were inconsistent. 7 , 17 - 20 , 22 - 24 , 52 Limitations of previous studies included residual confounding, 19 , 20 , 22 , 24 varying exposure definitions, limited statistical power, 20 , 22 - 24 and the assessment of the concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs being a secondary objective. 7 , 18 In line with our results, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 8 observational studies suggested an increased risk of major bleeding associated with the concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs (hazard ratio, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.14-1.58) compared with OAC use alone. 25 However, several knowledge gaps were identified, including the risk of major bleeding in important patient subgroups. The present study confirmed that compared with OACs alone, concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs increased the risk of major bleeding among patients 60 years of age or older and among both sexes. One study previously assessed this association in these patient subgroups; however, statistical power was limited. 22 Furthermore, we showed that the association remained similar irrespective of patients’ history of major bleeding or chronic kidney disease, both important factors in the HAS-BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal Renal/Liver Function, Stroke, Bleeding History or Predisposition, Labile International Normalized Ratio, Elderly [>65 Years], Drugs/Alcohol Concomitantly) score for major bleeding risk. 53 Our findings also suggested that the concomitant use of SSRIs with both DOACs and VKAs was associated with an increased risk of major bleeding, with a possible lower risk with DOACs, although 95% CIs overlapped. A cohort study of patients from the ROCKET-AF (Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared With Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Embolism and Stroke Trial in Atrial Fibrillation) trial suggested that the concomitant use of SSRIs and warfarin may increase the risk of major bleeding compared with rivaroxaban; however, the results were limited by high uncertainty and potential for selection bias and confounding. 20 In another nested case-control study of nursing home residents, similar increases in risk were associated with the concomitant use of SSRIs and DOACs and of SSRIs and VKAs; however, statistical power was low. 23

The increased risk of major bleeding with the concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs may occur through multiple mechanisms of action. During hemostasis, serotonin is released by platelets to enhance platelet activation and aggregation and prime them to interact with coagulation factors. 54 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors block the serotonin reuptake transporter on platelet membranes and reduce serotonin content within platelets by up to 80% to 90%, 39 , 40 decreasing the potency of hemostasis over time. In addition, some SSRIs, such as fluoxetine and fluvoxamine, inhibit the 1A2 and 2C9 isozymes of the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme, which play a key role in the metabolism of warfarin. 55 Nonetheless, the interaction analysis suggests that the joint association of SSRIs and OACs is mainly owing to their individual risks of major bleeding; hence, any additional risk posed by pharmacokinetic interaction is likely minimal.

Although the increased risk of major bleeding does not suggest withholding treatment with either SSRIs or OACs, measures can be taken to mitigate this risk. Studies suggest that DOACs have lower potential for pharmacokinetic interactions with SSRIs than VKAs, and guidelines also recommend them over VKAs for the management of nonvalvular AF. 44 - 46 , 55 , 56 Taken together with the findings in this study, DOACs may also be preferred for patients concomitantly using SSRIs. On the other hand, the risk of major bleeding was similar between SSRIs with more potent inhibition and SSRIs with less potent serotonin inhibition; thus; changing the SSRI may not be associated with bleeding risk. Finally, coprescription of proton pump inhibitors has also been suggested to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding. 51 , 57 Overall, risk factors for bleeding should be monitored and managed to improve the safety of the concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs. 51 Close monitoring is particularly essential within the first few months of concomitant use.

This study has notable strengths. First, the selection of a large study population from routine care settings enhanced generalizability and provided sufficient statistical power to generate precise estimates in primary and secondary analyses. Second, selection bias was unlikely because we analyzed a well-defined cohort and used a nested case-control approach. Third, the assessment of additive and multiplicative interactions provided evidence suggesting that any biological interaction between use of SSRIs and OACs and the risk of major bleeding may only be marginally synergistic. 42

This study also has some limitations. Residual confounding may affect the results given the observational nature of the study. The baseline risk for major bleeding may differ between patients concomitantly using SSRIs and those who were not. To mitigate potential bias, we adjusted for several potential confounders, including some lifestyle risk factors (such as BMI, smoking, and alcohol abuse). Furthermore, the results remained consistent in the time-conditional propensity score–matched analysis and in a post hoc analysis adjusted for additional comedications. Another consideration is that prescriptions recorded in the CPRD are those issued by general practitioners; hence, misclassification of exposure is possible if patients do not follow the treatment regimen. Prescriptions also do not include those issued by specialists, although AF as well as mild and moderate depression are managed mainly by general practitioners in the UK. 58 , 59 To explore the potential for misclassification, we varied the exposure assessment window in sensitivity analyses, which produced results consistent with the main results. Finally, outcome misclassification through inaccurate recording of bleeding in the Hospital Episodes Statistics repository may occur. In addition, the physician’s judgment may be influenced by knowledge of patient treatment. To mitigate bias, we considered only primary diagnoses and did not include elective hospitalizations.

In this large population-based, nested case-control study of patients with AF, the concomitant use of SSRIs and OACs was associated with an increased risk of major bleeding compared with OACs alone. To minimize the risk of bleeding, individual modifiable risk factors should be controlled, and patients should be closely monitored, particularly during the first few months of concomitant use.

Accepted for Publication: January 26, 2024.

Published: March 22, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3208

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2024 Rahman AA et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Christel Renoux, MD, PhD, Centre for Clinical Epidemiology, Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, Jewish General Hospital, 3755 Côte Sainte Catherine H 416.1, Montreal, QC H3T 1E2, Canada ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions: Mr Rahman and Dr Renoux had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Rahman, Platt, Boivin, Rej, Renoux.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Rahman, Platt, Beradid, Rej, Renoux.

Drafting of the manuscript: Rahman, Boivin, Renoux.

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Rahman, Platt, Beradid, Rej, Renoux.

Statistical analysis: Rahman, Beradid, Renoux.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Renoux.

Supervision: Platt, Boivin, Rej, Renoux.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Platt reported receiving personal fees from Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Nant Pharma, and Pfizer outside the submitted work. Dr Rej reported receiving a Clinician-Scientist Salary Award from Fonds de Recherche Quebec Sante; receiving grants from Mitacs; serving on a steering committee for AbbVie; and holding shares in Aifred outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding/Support: Mr Rahman was supported by a Tomlinson Doctoral Fellowship from McGill University, a Canada Graduate Scholarship–Doctoral from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and a stipend from the Drug Safety and Effectiveness Cross-Training Program.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 2 .

Additional Contributions: The authors would like to thank Sophie Dell’Aniello, MSc, Centre for Clinical Epidemiology, Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, Jewish General Hospital, for providing technical support in the analysis of data. She was not compensated for her contribution.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- 100 years of the AJE

- Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- About American Journal of Epidemiology

- About the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

- Journals Career Network

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

Cohort Studies Versus Case-Control Studies on Night-Shift Work and Cancer Risk: The Importance of Exposure Assessment

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Kyriaki Papantoniou, Johnni Hansen, Cohort Studies Versus Case-Control Studies on Night-Shift Work and Cancer Risk: The Importance of Exposure Assessment, American Journal of Epidemiology , Volume 193, Issue 4, April 2024, Pages 577–579, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwad227

- Permissions Icon Permissions