How to Write a Short Story: The Short Story Checklist

Rosemary Tantra Bensko and Sean Glatch | November 17, 2023 | 7 Comments

The short story is a fiction writer’s laboratory: here is where you can experiment with characters, plots, and ideas without the heavy lifting of writing a novel. Learning how to write a short story is essential to mastering the art of storytelling . With far fewer words to worry about, storytellers can make many more mistakes—and strokes of genius!—through experimentation and the fun of fiction writing.

Nonetheless, the art of writing short stories is not easy to master. How do you tell a complete story in so few words? What does a story need to have in order to be successful? Whether you’re struggling with how to write a short story outline, or how to fully develop a character in so few words, this guide is your starting point.

Famous authors like Virginia Woolf, Haruki Murakami, and Agatha Christie have used the short story form to play with ideas before turning those stories into novels. Whether you want to master the elements of fiction, experiment with novel ideas, or simply have fun with storytelling, here’s everything you need on how to write a short story step by step.

The Core Elements of a Short Story

There’s no secret formula to writing a short story. However, a good short story will have most or all of the following elements:

- A protagonist with a certain desire or need. It is essential for the protagonist to want something they don’t have, otherwise they will not drive the story forward.

- A clear dilemma. We don’t need much backstory to see how the dilemma started; we’re primarily concerned with how the protagonist resolves it.

- A decision. What does the protagonist do to resolve their dilemma?

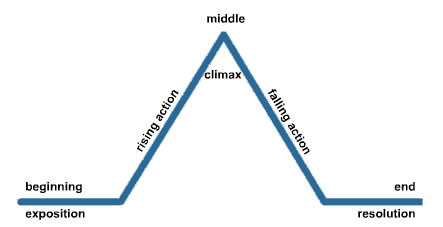

- A climax. In Freytag’s Pyramid , the climax of a story is when the tension reaches its peak, and the reader discovers the outcome of the protagonist’s decision(s).

- An outcome. How does the climax change the protagonist? Are they a different person? Do they have a different philosophy or outlook on life?

Of course, short stories also utilize the elements of fiction , such as a setting , plot , and point of view . It helps to study these elements and to understand their intricacies. But, when it comes to laying down the skeleton of a short story, the above elements are what you need to get started.

Note: a short story rarely, if ever, has subplots. The focus should be entirely on a single, central storyline. Subplots will either pull focus away from the main story, or else push the story into the territory of novellas and novels.

The shorter the story is, the fewer of these elements are essentials. If you’re interested in writing short-short stories, check out our guide on how to write flash fiction .

How to Write a Short Story Outline

Some writers are “pantsers”—they “write by the seat of their pants,” making things up on the go with little more than an idea for a story. Other writers are “plotters,” meaning they decide the story’s structure in advance of writing it.

You don’t need a short story outline to write a good short story. But, if you’d like to give yourself some scaffolding before putting words on the page, this article answers the question of how to write a short story outline:

https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-story-outline

How to Write a Short Story Step by Step

There are many ways to approach the short story craft, but this method is tried-and-tested for writers of all levels. Here’s how to write a short story step by step.

1. Start With an Idea

Often, generating an idea is the hardest part. You want to write, but what will you write about?

What’s more, it’s easy to start coming up with ideas and then dismissing them. You want to tell an authentic, original story, but everything you come up with has already been written, it seems.

Here are a few tips:

- Originality presents itself in your storytelling, not in your ideas. For example, the premise of both Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Ostrovsky’s The Snow Maiden are very similar: two men and two women, in intertwining love triangles, sort out their feelings for each other amidst mischievous forest spirits, love potions, and friendship drama. The way each story is written makes them very distinct from one another, to the point where, unless it’s pointed out to you, you might not even notice the similarities.

- An idea is not a final draft. You will find that exploring the possibilities of your story will generate something far different than the idea you started out with. This is a good thing—it means you made the story your own!

- Experiment with genres and tropes. Even if you want to write literary fiction , pay attention to the narrative structures that drive genre stories, and practice your storytelling using those structures. Again, you will naturally make the story your own simply by playing with ideas.

If you’re struggling simply to find ideas, try out this prompt generator , or pull prompts from this Twitter .

2. Outline, OR Conceive Your Characters

If you plan to outline, do so once you’ve generated an idea. You can learn about how to write a short story outline earlier in this article.

If you don’t plan to outline, you should at least start with a character or characters. Certainly, you need a protagonist, but you should also think about any characters that aid or inhibit your protagonist’s journey.

When thinking about character development, ask the following questions:

- What is my character’s background? Where do they come from, how did they get here, where do they want to be?

- What does your character desire the most? This can be both material or conceptual, like “fitting in” or “being loved.”

- What is your character’s fatal flaw? In other words, what limitation prevents the protagonist from achieving their desire? Often, this flaw is a blind spot that directly counters their desire. For example, self hatred stands in the way of a protagonist searching for love.

- How does your character think and speak? Think of examples, both fictional and in the real world, who might resemble your character.

In short stories, there are rarely more characters than a protagonist, an antagonist (if relevant), and a small group of supporting characters. The more characters you include, the longer your story will be. Focus on making only one or two characters complex: it is absolutely okay to have the rest of the cast be flat characters that move the story along.

Learn more about character development here:

https://writers.com/character-development-definition

3. Write Scenes Around Conflict

Once you have an outline or some characters, start building scenes around conflict. Every part of your story, including the opening sentence, should in some way relate to the protagonist’s conflict.

Conflict is the lifeblood of storytelling: without it, the reader doesn’t have a clear reason to keep reading. Loveable characters are not enough, as the story has to give the reader something to root for.

Take, for example, Edgar Allan Poe’s classic short story The Cask of Amontillado . We start at the conflict: the narrator has been slighted by Fortunato, and plans to exact revenge. Every scene in the story builds tension and follows the protagonist as he exacts this revenge.

In your story, start writing scenes around conflict, and make sure each paragraph and piece of dialogue relates, in some way, to your protagonist’s unmet desires.

4. Write Your First Draft

The scenes you build around conflict will eventually be stitched into a complete story. Make sure as the story progresses that each scene heightens the story’s tension, and that this tension remains unbroken until the climax resolves whether or not your protagonist meets their desires.

Don’t stress too hard on writing a perfect story. Rather, take Anne Lamott’s advice, and “write a shitty first draft.” The goal is not to pen a complete story at first draft; rather, it’s to set ideas down on paper. You are simply, as Shannon Hale suggests, “shoveling sand into a box so that later [you] can build castles.”

5. Step Away, Breathe, Revise

Whenever Stephen King finishes a novel, he puts it in a drawer and doesn’t think about it for 6 weeks. With short stories, you probably don’t need to take as long of a break. But, the idea itself is true: when you’ve finished your first draft, set it aside for a while. Let yourself come back to the story with fresh eyes, so that you can confidently revise, revise, revise .

In revision, you want to make sure each word has an essential place in the story, that each scene ramps up tension, and that each character is clearly defined. The culmination of these elements allows a story to explore complex themes and ideas, giving the reader something to think about after the story has ended.

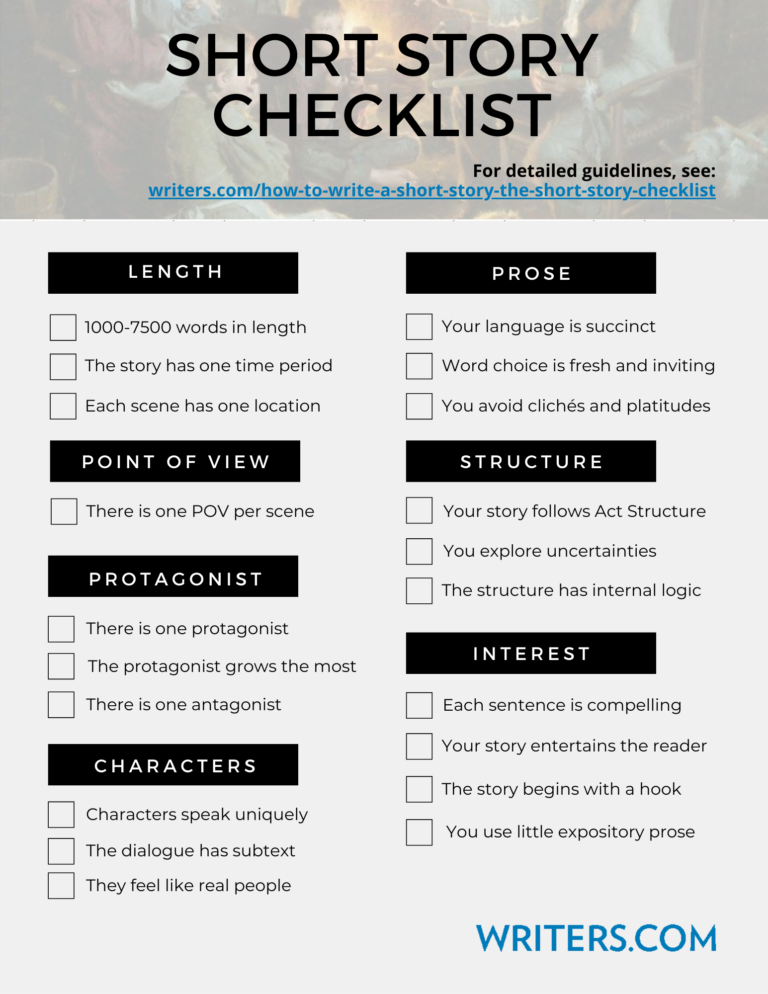

6. Compare Against Our Short Story Checklist

Does your story have everything it needs to succeed? Compare it against this short story checklist, as written by our instructor Rosemary Tantra Bensko.

Below is a collection of practical short story writing tips by Writers.com instructor Rosemary Tantra Bensko . Each paragraph is its own checklist item: a core element of short story writing advice to follow unless you have clear reasons to the contrary. We hope it’s a helpful resource in your own writing.

Update 9/1/2020: We’ve now made a summary of Rosemary’s short story checklist available as a PDF download . Enjoy!

Click to download

How to Write a Short Story: Length and Setting

Your short story is 1000 to 7500 words in length.

The story takes place in one time period, not spread out or with gaps other than to drive someplace, sleep, etc. If there are those gaps, there is a space between the paragraphs, the new paragraph beginning flush left, to indicate a new scene.

Each scene takes place in one location, or in continual transit, such as driving a truck or flying in a plane.

How to Write a Short Story: Point of View

Unless it’s a very lengthy Romance story, in which there may be two Point of View (POV) characters, there is one POV character. If we are told what any character secretly thinks, it will only be the POV character. The degree to which we are privy to the unexpressed thoughts, memories and hopes of the POV character remains consistent throughout the story.

You avoid head-hopping by only having one POV character per scene, even in a Romance. You avoid straying into even brief moments of telling us what other characters think other than the POV character. You use words like “apparently,” “obviously,” or “supposedly” to suggest how non-POV-characters think rather than stating it.

How to Write a Short Story: Protagonist, Antagonist, Motivation

Your short story has one clear protagonist who is usually the character changing most.

Your story has a clear antagonist, who generally makes the protagonist change by thwarting his goals.

(Possible exception to the two short story writing tips above: In some types of Mystery and Action stories, particularly in a series, etc., the protagonist doesn’t necessarily grow personally, but instead his change relates to understanding the antagonist enough to arrest or kill him.)

The protagonist changes with an Arc arising out of how he is stuck in his Flaw at the beginning of the story, which makes the reader bond with him as a human, and feel the pain of his problems he causes himself. (Or if it’s the non-personal growth type plot: he’s presented at the beginning of the story with a high-stakes problem that requires him to prevent or punish a crime.)

The protagonist usually is shown to Want something, because that’s what people normally do, defining their personalities and behavior patterns, pushing them onward from day to day. This may be obvious from the beginning of the story, though it may not become heightened until the Inciting Incident , which happens near the beginning of Act 1. The Want is usually something the reader sort of wants the character to succeed in, while at the same time, knows the Want is not in his authentic best interests. This mixed feeling in the reader creates tension.

The protagonist is usually shown to Need something valid and beneficial, but at first, he doesn’t recognize it, admit it, honor it, integrate it with his Want, or let the Want go so he can achieve the Need instead. Ideally, the Want and Need can be combined in a satisfying way toward the end for the sake of continuity of forward momentum of victoriously achieving the goals set out from the beginning. It’s the encounters with the antagonist that forcibly teach the protagonist to prioritize his Needs correctly and overcome his Flaw so he can defeat the obstacles put in his path.

The protagonist in a personal growth plot needs to change his Flaw/Want but like most people, doesn’t automatically do that when faced with the problem. He tries the easy way, which doesn’t work. Only when the Crisis takes him to a low point does he boldly change enough to become victorious over himself and the external situation. What he learns becomes the Theme.

Each scene shows its main character’s goal at its beginning, which aligns in a significant way with the protagonist’s overall goal for the story. The scene has a “charge,” showing either progress toward the goal or regression away from the goal by the ending. Most scenes end with a negative charge, because a story is about not obtaining one’s goals easily, until the end, in which the scene/s end with a positive charge.

The protagonist’s goal of the story becomes triggered until the Inciting Incident near the beginning, when something happens to shake up his life. This is the only major thing in the story that is allowed to be a random event that occurs to him.

How to Write a Short Story: Characters

Your characters speak differently from one another, and their dialogue suggests subtext, what they are really thinking but not saying: subtle passive-aggressive jibes, their underlying emotions, etc.

Your characters are not illustrative of ideas and beliefs you are pushing for, but come across as real people.

How to Write a Short Story: Prose

Your language is succinct, fresh and exciting, specific, colorful, avoiding clichés and platitudes. Sentence structures vary. In Genre stories, the language is simple, the symbolism is direct, and words are well-known, and sentences are relatively short. In Literary stories, you are freer to use more sophisticated ideas, words, sentence structures and underlying metaphors and implied motifs.

How to Write a Short Story: Story Structure

Your plot elements occur in the proper places according to classical Act Structure so the reader feels he has vicariously gone through a harrowing trial with the protagonist and won, raising his sense of hope and possibility. Literary short stories may be more subtle, with lower stakes, experimenting beyond classical structures like the Hero’s Journey. They can be more like vignettes sometimes, or even slice-of-life, though these types are hard to place in publications.

In Genre stories, all the questions are answered, threads are tied up, problems are solved, though the results of carnage may be spread over the landscape. In Literary short stories, you are free to explore uncertainty, ambiguity, and inchoate, realistic endings that suggest multiple interpretations, and unresolved issues.

Some Literary stories may be nonrealistic, such as with Surrealism, Absurdism, New Wave Fabulism, Weird and Magical Realism . If this is what you write, they still need their own internal logic and they should not be bewildering as to the what the reader is meant to experience, whether it’s a nuanced, unnameable mood or a trip into the subconscious.

Literary stories may also go beyond any label other than Experimental. For example, a story could be a list of To Do items on a paper held by a magnet to a refrigerator for the housemate to read. The person writing the list may grow more passive-aggressive and manipulative as the list grows, and we learn about the relationship between the housemates through the implied threats and cajoling.

How to Write a Short Story: Capturing Reader Interest

Your short story is suspenseful, meaning readers hope the protagonist will achieve his best goal, his Need, by the Climax battle against the antagonist.

Your story entertains. This is especially necessary for Genre short stories.

The story captivates readers at the very beginning with a Hook, which can be a puzzling mystery to solve, an amazing character’s or narrator’s Voice, an astounding location, humor, a startling image, or a world the reader wants to become immersed in.

Expository prose (telling, like an essay) takes up very, very little space in your short story, and it does not appear near the beginning. The story is in Narrative format instead, in which one action follows the next. You’ve removed every unnecessary instance of Expository prose and replaced it with showing Narrative. Distancing words like “used to,” “he would often,” “over the years, he,” “each morning, he” indicate that you are reporting on a lengthy time period, summing it up, rather than sticking to Narrative format, in which immediacy makes the story engaging.

You’ve earned the right to include Expository Backstory by making the reader yearn for knowing what happened in the past to solve a mystery. This can’t possibly happen at the beginning, obviously. Expository Backstory does not take place in the first pages of your story.

Your reader cares what happens and there are high stakes (especially important in Genre stories). Your reader worries until the end, when the protagonist survives, succeeds in his quest to help the community, gets the girl, solves or prevents the crime, achieves new scientific developments, takes over rule of his realm, etc.

Every sentence is compelling enough to urge the reader to read the next one—because he really, really wants to—instead of doing something else he could be doing. Your story is not going to be assigned to people to analyze in school like the ones you studied, so you have found a way from the beginning to intrigue strangers to want to spend their time with your words.

Where to Read and Submit Short Stories

Whether you’re looking for inspiration or want to publish your own stories, you’ll find great literary journals for writers of all backgrounds at this article:

https://writers.com/short-story-submissions

Learn How to Write a Short Story at Writers.com

The short story takes an hour to learn and a lifetime to master. Learn how to write a short story with Writers.com. Our upcoming fiction courses will give you the ropes to tell authentic, original short stories that captivate and entrance your readers.

Rosemary – Is there any chance you could add a little something to your checklist? I’d love to know the best places to submit our short stories for publication. Thanks so much.

Hi, Kim Hanson,

Some good places to find publications specific to your story are NewPages, Poets and Writers, Duotrope, and The Submission Grinder.

“ In Genre stories, all the questions are answered, threads are tied up, problems are solved, though the results of carnage may be spread over the landscape.”

Not just no but NO.

See for example the work of MacArthur Fellow Kelly Link.

[…] How to Write a Short Story: The Short Story Checklist […]

Thank you for these directions and tips. It’s very encouraging to someone like me, just NOW taking up writing.

[…] Writers.com. A great intro to writing. https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-short-story […]

Hello: I started to write seriously in the late 70’s. I loved to write in High School in the early 60’s but life got in the way. Around the 00’s many of the obstacles disappeared. Since then I have been writing more, and some of my work was vanilla transgender stories. Here in 2024 transgender stories have become tiresome because I really don’t have much in common with that mind set.

The glare of an editor that could potentially pay me is quite daunting, so I would like to start out unpaid to see where that goes. I am not sure if a writer’s agent would be a good fit for me. My work life was in the Trades, not as some sort of Academic. That alone causes timidity, but I did read about a fiction writer who had been a house painter.

This is my first effort to publish since the late 70’s. My pseudonym would perhaps include Ahabidah.

Gwen Boucher.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Plot and Structure: How to Use Structure and Subplot to Add Suspense

by Joslyn Chase | 22 comments

You can't write a great story if you don't master plot and structure. But what is the best structure for a novel? How do you plot a novel?

Working on structuring a nonfiction book? Check out our nonfiction book structure guide here .

Figuring out your plot structure is essential for your story's success. Even if you have an exciting idea for a story, great characters, and a memorable setting, you still need to put your protagonist through events that have high and escalating stakes, and structure them for maximum effect.

If you want to write a great story, you need to include the elements of suspense . You can do this by using writing techniques and devices like:

- engaging your reader on a deep level,

- making your reader care about your characters,

- sequence of events

- cliffhangers

- planting clues

- foreshadowing

But without a sound plot and structure, you risk failing to thrill your readers. Today, we’ll look at dramatic structure and learn how you can build an effective plan for your entire plot. By planning for success, you can create a story packed with suspense, with all the right twists in all the right places.

Definition of Plot and Structure

What is story plot? What is the best structure for a novel?

Plot is the series of events that make up your story, including the order in which they occur and how they relate to each other. Structure (also known as narrative structure), is the overall design or layout of your story.

While plot is specific to your story and the particular events that make up that story, dramatic structure is more universal and deals with the mechanics of the story—how the chapters or scenes are broken up, how conflict is introduced and amplified, where the climax is placed, how the resolution plays out, and so on.

You can think of plot and structure like the DNA of your story. Every story takes on a plot, and every piece of writing has a structure. While plot is unique to your story, an understanding of effective structures and devices can help you develop better stories and hone your craft.

Searching for Structure

From the beginning of my writer’s journey, I knew story structure had to be a vital part of creating successful stories. But I wasn’t sure how to best construct a story, which of the many models would produce the best results for me.

I started writing short stories using a nine-point, three act structure consisting of hook, backstory, and trigger in act one. Crisis, struggle, and epiphany in act two. And plan, climax, and resolution in the final act.

This worked fine. At first. But as I expanded into longer writing forms like novellas and novels, I realized I needed something more. And something better-suited to the types of suspense fiction I like to write.

I explored several models of story structure, including the Algis Budrys seven-point story structure of simply putting a character in a setting with a problem and then employing try/fail cycles until the climax where he succeeds or ultimately fails before ending with a validation.

I found a lot to like in Syd Field's model for storytelling. I tried the Lester Dent Master Plot Formula for dramatic writing and found it works quite well for writing an exciting short story. But again, these models weren’t a perfect fit for me. My search continued.

Hitting Paydirt

Just as I began writing my first novel, I stumbled upon Shawn Coyne’s Story Grid and I knew at once that it would be a game-changer for me. I wrote Nocturne In Ashes and Steadman’s Blind using Shawn’s Five Commandments of story to structure each scene and the overall shape of the books.

Following this pattern, I learned an incredible amount about how to hit all the right points in a three-act structure and make sure each scene is vital and has a turning point. But my writing process is still evolving. Though I would never trade my experience with the Story Grid structure which really helped me get a handle on the micro view of storytelling, I was still looking for something ideally suited for writing mysteries and thrillers.

Let me tell you about what I’ve been using lately!

Six Elements of Plot That Strengthen Story Structure

When Joe Bunting published The Write Structure , I purchased it right away. However, it sat on my virtual reading shelf for a couple of months before I cracked it open and began reading.

Once I finally got started, I was delighted to find that The Write Structure resonated with me in so many ways and I knew I could use this pattern to write anything from a short story to a full-length novel and make it shine.

The book is filled with great tips, techniques, and advice for writers, backed up by examples and Joe’s own experience as a best-selling author. He takes you step-by-step through the six elements of a plot that will guide you in writing a stellar story and shows you how to develop each element effectively.

These are the six plot elements, as set forth in The Write Structure:

The Exposition is where you introduce your hero and establish the story setting, your hero’s world. By focusing on the core value at stake from the very beginning, you confirm genre for your readers and introduce dramatic tension by setting up conflict and forcing your character to act on a choice.

In most types of suspense fiction, the story will turn on a core value of Life vs. Death or perhaps a Fate Worse than Death. Often, the internal value at stake is Good vs. Evil. Crime stories, on some level, usually deal with issues of justice and good guys vanquishing bad guys while lives are in danger.

During this exposition phase, use specific details and descriptive elements to sink your reader deep into the story and make them care about your hero and worry over what will happen next.

Inciting Incident

Once your reader is grounded in the story world and emotionally invested in your character, something needs to happen to interrupt the established pattern and rock your character’s world in some way. An Inciting Incident begins the story arc that will eventually culminate in the climactic scene and ending resolution of your story.

The inciting incident should be inspired by, and reinforce, the core value at stake in the story. In a crime story, this event—whether coincidental or triggered by a story character—works best when it reflects a conflict between life and death or something worse.

The way you pace your story and deliver information to your reader is paramount to your story’s success, right from the very beginning.

Rising Action

Rising Action is where you raise the stakes and ratchet up the tension in a buildup toward the dilemma. These are the try/fail cycles, the struggle to understand the antagonistic force and find a way to defeat it through trial and error.

When thriller writer, Lee Child, was asked to divulge his recipe for creating suspense, he said it’s not so much about the ingredients as it is about making your family hungry, making them wait. This is where you spin out uncertainty and worry, making your reader hungry for the payoff.

I've written several articles about how to increase tension in a story's plot by focusing on the elements of suspense. The writing techniques I've taught in these articles, such as how to create cliffhangers, write an action scene, and plant clues and red herrings, will help you develop rising action in your story. Learn more about how to use these powerful techniques in your stories by reading each article (linked in the previous sentence).

All of these writing skills will help you keep the story pace moving along through the middle, where many writers flounder.

Now we get to the crux of the story, where the rubber meets the road. The Dilemma boils down to a choice your protagonist must make—a difficult and crucial choice.

There are two types of choices that create the most conflict and drama. The first is often called the Best Bad Choice, where there is no happy alternative and your character is forced to choose from a menu of unsavory options.

For instance: Does Katniss cut down a tracker jacker nest and kill some of the tributes, or does she wait for the tributes to kill her?

The other variety of tough choices involves having to decide between conflicting goods, otherwise called an Irreconcilable Goods Decision. In this scenario, someone benefits while someone else is harmed. There is no win/win.

For example: Does Kramer hire someone to take care of his son in order to work a prestigious job, or does he step down from his career to be a reliable parent?

The dilemma is the heart of your story. It’s where your hero demonstrates his true character development. If you’ve created a sympathetic protagonist readers care about, they will be desperate to learn how he chooses and what happens as a result of that choice.

Your hero faces a difficult choice in the dilemma, but the Climax is where she acts on that choice and reaps the consequences of that action. This is the payoff you’ve been building toward since the beginning. This is the summit readers want to reach when they open a book.

This is also where your hero gains or ultimately loses what she seeks. In suspense fiction, that sought-after objective is usually solving a crime and bringing the perpetrator to justice. Or it might be revenge, rescue, or the acquisition of wealth or power.

Whatever it is, it centers on the conflict between the core values at stake—life or death. The events in your story have transformed and prepared your protagonist for this final confrontation.

Now it’s showtime.

Knowing your story's climax also helps to hone your skills of foreshadowing . You’ll be able to properly place your setups and readers won’t feel cheated.

It’s also a good idea to make sure you’ve honored reader expectations and delivered a story suited to what suspense fans crave.

Writers are sometimes tempted to skip writing the Denouement of the plot, or give it short shrift.

Don’t. If you want readers to look back fondly on your story and pick up your next book, give them the closure they desire.

Readers need a moment to savor the climax and feel the release of tension. If you’ve done a good job creating compelling characters, readers won’t want to say goodbye right away. Let them spend a little more time together.

This is where you validate your protagonist’s arc and reflect on how she’s changed. Even if the world around her is back to normal, she’s not the same person who started the story.

This is also where you wrap up any loose ends and it’s the perfect place to bring secondary plotlines to a close. Read below to learn more about subplots.

A Sound Structure for Suspense

The Write Structure addresses the complexities involved in putting together a story that works on multiple levels to engage an audience, and it does so in a user-friendly way. Instead of overwhelming, it simplifies the process so that you can actually create a plan for your own full-length book in just eighteen sentences.

In The Write Structure, you’ll learn the nitty gritty details about how to craft these six elements in your story to develop your idea into a full-blown, living, breathing creation that readers will love. The process gives you the tools to create the right structure for your book while still leaving plenty of room for flexibility and creativity.

Perhaps my favorite aspect of the process is how it can be geared toward a particular genre—in our case, that means mysteries, thrillers, and adventure stories. In my opinion, that makes The Write Structure an excellent model for writing suspense fiction.

Plot AND Structure: Don't Forget Subplots

If you use the six elements of plot, you'll develop a sound structure for your suspense story—or any story. However, these vital scenes in the structure won't uphold a story that can stretch the length of the novel. In order to develop the plot, you need secondary storylines, or subplots, too.

How do you use subplots?

What Are Subplots?

A plot is a series of linked moments, a chain of events with one leading into the next. In a short story , you’re better off sticking with a single plotline in most cases. Anything longer than a short story, however, is enriched by weaving in one or more secondary plotlines, or subplots.

You can see this clearly in just about any television episode. There’s an A plot and a B plot. The A plot is the main story. The B plot forms a supporting storyline that plays off the A plot and may highlight theme or act as a foil or contrast to the A plot.

Sometimes the plotlines tie together at the end. Other times, they simply run parallel and the secondary plotline has its own conclusion, usually in one of the last scenes in the book.

Here's an example of how a subplot may operate to support the main plot.

Mr. Monk Goes to The Circus

In the television show, Monk, there’s an episode where Monk solves the murder of a circus ringmaster. That’s the A plot.

The B plot is introduced when Monk and his nurse, Sharona, go to the circus to investigate.

Here’s a clip from the episode:

The B plot comes into play when Sharona encounters the elephant and freaks out. We learn she’s terrified of elephants due to a traumatic scene she once witnessed at a zoo.

- Monk is oblivious to her distress—his only concern is that she isn’t responding to his needs. Sharona gets upset because she has to deal constantly with his phobias and idiosyncrasies, yet he has zero compassion for her over her fear of elephants. He enrages her by telling her to “suck it up.”

- Sharona starts a campaign to teach Monk a lesson. This campaign manifests at various points throughout the A plot when she refuses to hand him a wipe, drinks from his water bottle, coughs in his face, and messes up his orderly magazines. When he protests, she tells him to “suck it up.”

- Monk sends her flowers. He calls her to talk about the issue and when she finally opens up and begins sharing her feelings, Monk gets distracted and hangs up on her to follow a lead from the A plot.

- Monk discusses the problem with his therapist, Dr. Kroger. Of course, Kroger understands why Sharona’s angry, but he refuses to explain it to Monk, insisting that Monk will have to figure it out for himself—the answer is inside him.

- Monk and Sharona continue arguing. Just as she’s telling Monk he’ll never get it, Monk tells Sharona’s son to put his bicycle away, saying, “Let’s give your mother a break.” She points out that he was showing empathy at that point. It’s a start.

- Monk arranges for Sharona to confront her fear by meeting with the elephant and his master, unaware that the killer plans to use the elephant as a murder weapon to eliminate a witness. Sharona watches as this event in the A plot plays out and the elephant crushes his master’s skull, killing him.

- This makes things worse and now Monk feels really bad. He pampers Sharona, tucking a blanket around her and trying to make her cocoa, but she ends up doing all the work, as usual.

- In the story’s climax— the A plot —the culprit tries to escape and is stopped by the elephant. Sharona comes face to face with the creature and Monk soothes and empathizes with her. Then over-empathizes and won’t shut up with the empathizing. Sharona remarks that she’s created a monster.

- Sharona feeds carrots to the elephant and tells Monk she’s over it—maybe there’s hope for him. But Monk is still Monk and we know he’ll be back next week, still victim to a thousand debilitating foibles, to solve another baffling crime. (This is the Denouement.)

Do you see how the secondary plotline plays off the main plotline, intersecting it in some spots, adding dimension to the story’s climax, and providing the perfect ending? This is what subplots do.

Including subplots will elevate the tension and create depth to your main plotline.

Do You Really Need Subplots?

You don’t need to include a secondary plotline in your novel. But if you don’t, you’re passing up a great vehicle for adding depth, interest, emotion, tension, and excitement to your story. That said, it’s essential that readers understand who the book is about.

There should be one main character—your hero—whose story carries the most weight and whose arc comprises the main plotline. Readers should not be confused about who this is, so take care not to overwhelm that main arc when developing your secondary plots.

A secondary plotline can center on just about anything, including a character, setting, theme, motif, or problem. It can enter the story at any point and leave at any point—no need for it to run through the entire story unless that’s what serves the story best.

Every subplot, however, should be tied up by story’s end. The only reason you might consider leaving a secondary plotline open at the end of the story is so that it can function as a lead-in to the sequel.

For example, in my thriller novel, Nocturne In Ashes, the main story arc about stopping a serial killer is wrapped up in the end. But one of my subplots involved a police detective’s efforts to gain entry into an elite private security organization. That story line left a dangling thread to be picked up in the sequel.

One more thing—secondary plotlines must relate somehow to the main plotline and not exist just to take up space or add complexity. They must have a valid story reason to be there.

Joe Bunting’s book, The Write Structure, also addresses how to handle subplots in structuring your story.

A Plan for Your Book Sets You Up for Success

Ultimately, the best way to structure your book is to find a process that works for you and the types of fiction you want to write. That may entail exploring and adapting, learning and growing as you move through your own writer’s journey and learn the craft of writing.

You may not want to use the same plan for every story. I still structure my short fiction differently than my full-length books and I decide project by project how I’m going to do it.

I do think it’s important to make some kind of plan before you begin writing. When all is said and done, if you produce a story with all the right elements to attract and hold readers all the way to the end, you have a well-structured story.

You can get there by making a plan to guide you—like signposts along your journey. Or you can stumble around through rewrite after rewrite until you finally arrive. Either way, structure is what you need to make it work.

Why not embrace plot and structure and make it your traveling companion on the road to success?

Want to learn more about plot? Check out The Write Structure which helps writers make their plot better and write books readers love. It's only $5.99 for a limited time. Check out The Write Structure here.

How about you? Do you use the six elements of plot and subplots in your stories? Tell us about it in the comments .

Using your current writing project, formulate a possible secondary plotline for your story. Write a paragraph to describe how the plotline begins in relation to the main plotline, and another paragraph to explain how it ends. Write one more paragraph to outline some points along the way.

If you don’t have a work in progress, practice by watching an episode of your favorite television series and outlining the B plot, like I did with Monk.

Write for fifteen minutes . When you’re finished, if you’d like to share your work, post it in the comments. And please provide feedback for your fellow writers as well!

Joslyn Chase

Any day where she can send readers to the edge of their seats, prickling with suspense and chewing their fingernails to the nub, is a good day for Joslyn. Pick up her latest thriller, Steadman's Blind , an explosive read that will keep you turning pages to the end. No Rest: 14 Tales of Chilling Suspense , Joslyn's latest collection of short suspense, is available for free at joslynchase.com .

22 Comments

I plot using Scapple, a Scrivner product – 10 bucks. It allows me to make mind maps of my developing stories. After I decide to go forward I make a paragraph for each mind map spot. Usually I don’t end up actually keeping to the plan as the story takes off at some point and has a mind of its own, but the plotting before prevents mind boggling sequence of events problems in the editing phase.

While I do agree Scapple is ok – there is freeware and open source software for the casual or pro writer. I’ve always done brainstorming and mind maps physically. I’d rather spend money on an actual blackboard or even smartscreen, than purchase software that limits the visible map field to the size of your screen. Most advice giving writers are in it for the money, and when a fellow as me that is financially secure looks for advice, all I see are price tags on creativity. I’d rather smith them myself through trial and failure, as anyone who is passionate about the craft, should.

My WIP uses the narrative arc plot structure. The exposition is where the narrator (Alex) meets her new neighbor (Alicia) and the two discover a dead body. Rising action is the process of solving the mystery. Climax is when they identify the killer and confront her. The very brief falling action is the loose ends being tied up. And the resolution is when their friendship is cemented at the end of the adventure.

The two doors also works. The disturbance is when they discover the corpse and the first point of no return is when Alex decides to help Alicia investigate the murder. The second is a moment when they’re in the woods at midnight, making their way to an abandoned theater to look for clues, and they have to leave the path. Alex is apprehensive but decides to follow Alicia. The literal act of stepping off the path metaphorically represents the moment when Alex decides to leave her old self behind.

Taking a moment to actually think about the physical plot structure can help when you’re trying to sequence events. It’s something I’ll try to be more aware of when I’m planning.

I have a character, a girl who was kidnapped after birth from a king. She was kidnapped by a servant of the king 13 years ago from when my story is set. My story is set in a sort of modern dystopia in a fiction location but the main character is a detective who finds her only in convenience of her misbehaving on the streets. She doesn’t know she is the daughter of a king and the servant who is kept in hiding doesn’t tell her.

However there are multiple POV”s and I don’t know how to develop a simple plot where she finally finds out where she is from. Does anyone have any suggestions???

Hey, I don’t know if you realize this, but you posted this as a reply to my comment instead of making your own comment on the post. You might want to do that so more people see it.

And to give some advice, I would say reexamine which POV’s you’re using in your story. If you’re trying to tell a narrative about this girl’s birth, the narrators should be people who are somehow related to her life or the kidnapping. You may have to sacrifice some of your narrators if they’re getting in the way of telling the story. Kill your darlings, as they say!

Personally, I like to let the story offer hints on how to tell it. I’ve done multiple pov tales where the story’s scenes come alive with great dialog and interaction. I’ve been told by a smart person, he said get out of the way and let the story flow. It’s sometimes hard to get out of the way, wanting to control the story that wants to be written. If the story is inspiring, exciting and you can’t wait to share it… get out of the way and let it out. I’ve been told by so many all these restrictions… don’t do this, you can’t do that, you should do this or that isn’t how it’s done.

Have you read the great literature from the masters? Even Tolkien was long winded with descriptions and details. It would have been impossible to make such grand movies without all of it. But it isn’t the sort of writing you’ll find today by the modern masters. King,Rowling, Brown, and many more are of a different type, their writing is more urgent and filled with emotions and actions.

So find the voice inside, the one that’s uniquely your own and tell the story within raging to be born… set your mind free and let your story take wing.

Well I won’t be sharing my practice today, which was option one, because I plan on doing this idea for NaNoWriMo and don’t want to spoil it. 😉 but I will share how I began developing my plot for another WIP First I started with a first draft. I wrote the whole thing without a care about character development, grammar or other things you worry about in the editing process. That draft SUCKED. I can tell you as much. For a while I let it simmer not looking at it and content with the fact that I had completed a book even if it was only a first draft. After about a month or so i picked it up again. I laughed and laughed like there was no tomorrow. there were errors all over the place and It was simply hilarious to me at the time. I set it down again for about a year but that dint’ stop me from thinking about it. Unknowingly i went through the processes mentioned in the blog post. That first draft has nothing to do with the novel I have now, besides the fact the some of the characters are the same. Well there’s my experience with this post. Thanks for sharing it with us Matt Herron!

Number 3, I choose you!

My character, Jade, has to make a decision between life and death. Not for herself. The main villain is a fallen angel called Dark, and has a kind of traumatizing back story. Jade feels pity toward him, but he’s the main villain, and doing destruction and causing mayhem.

At one point, Dark goes out of control, and starts planning to kill everyone Jade loves. Jade get made, like anyone else would, and get confused on what to do. So she decides to talk to him, and see if he’s willing to stop. (Jade prefers the kind approach, or is at least trying it.) The conversation goes terribly wrong, including it getting interrupted several times, due to another group of bad guys destroying thing.

Jade then actually has to make a choice between killing Dark or letting him live. For an entire chapter (In its rough draft state), she just thinks about her options, and then talks to her friends about it. Of course they say kill him, but what’s right isn’t always popular, and what’s popular isn’t always right.

Jade thinks that killing Dark would be wrong, but Dark isn’t the most stable or good thing in the universe. At all. And there’s really no way to fix him, or help him heal. Jade would end up looking for information of Dark, to get a better feeling toward what he’s feeling, but finds that his record aren’t clean. He’s as bad as it gets.

But Jade actually wants him to live, even to understand him. Understand the pain, and the sorrow. She looks up his back story, finding it’s full of terrible stuff. She feels pity toward him, and wants to help him. One problem; she doesn’t know how.

Yeah, I know. I probably wrote this terribly. But, we all did at one point.

If you ever wrote this story I’d like to read it. It sounds interesting. What’s the title?

You know, they tell you a script is linear. You go with that cause you’re green. And these people appear to be experts. There’s all kinds of them. Turns out a script is not linear at all. It resembles the graph representing Google stock. Not only that, but you can put your own graph line in there and loop it back to the second scene. And you can explode a line on the rebound. So, to all you experts, you are hindering creativity. There’s no absolute way to write.

Yep. Because reality usually doesn’t follow a simple line. I think this is helpful to some degree though.

It’s more like a big ball of wibbly wobbly scripts wiptsy, really….

And a bit of wibbly wobbly, timey wimey stuff

I agree, but there still needs to be structure. I learned that the hard way.

I think the three act structure can be fatal especially if you don’t understand it (like how I didn’t!) There can be multiple turning points in a story, and it might look like a cubic graph–or sin or cos–or maybe the stock exchange. The three act structure is just a very rough template for the main climax, but there can–and should be–many.

This is the simplest explanation I ever read about plot structure. It gave me a better understanding of the subject matter. Well done!

Hears some advice for you kids: the bad writers borrow, the great writers steal!

Here’s my advice, kids: the bad writers borrow, the great writers steal!

What is the series of related events that gives the story its structure? Plot, exposition, or setting?

Characters, Theme, Plot, and Genre are the elements of structure.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Learn Creative Writing with Scrivener • M.G. Herron - […] A Writer’s Cheatsheet to Plot and Structure […]

- Links for Writers November 2014 | A while in the woods - […] A Writer’a Cheatsheet to Plot and Structure by Matt Herron at The Write […]

- Only Think Thoughts Connected to Actions You Desire | outoftheclosetwriting - […] https://thewritepractice.com/plot-structure/ […]

- 3 Ways to NOT Fail at NaNoWriMo - […] Outline. An annotated outline of your main plot points or ideas is your first chance to think through what your book…

- An Author’s Journal | Angela B. Chrysler - […] November 3 – Another awesome link! This goes back to my days in 11th grade English. For those of…

- Components of a Story | Hoag Library - […] Writer’s Cheatsheet […]

- How to Use Scrivener to Start and Finish a Rough Draft - […] to the important pieces of Scrivener’s user interface; you’re familiar with the essential plot and structure principles, including why…

- Attack of the Middles – the Miscontents - […] A Writer’s Cheatsheet to Plot and Structure […]

- A Writer’s Cheatsheet to Plot and Structure | Toni Kennedy : A Writing Life - […] A Writer’s Cheatsheet to Plot and Structure […]

- Plotting! - Rachel MareeRachel Maree - […] A Writer’s Cheat Sheet to Plot and Structure […]

- How to Write Spoken Word – Smart Writing Tips - […] But this type of writing isn’t as foreign as you might think. It can follow the same pattern as…

- How to Write a Good Plot | - […] https://thewritepractice.com/plot-structure/ […]

- An Author's Journal - Brain to Books - […] November 3 – Another awesome link! This goes back to my days in 11th grade English. For those of…

- Writing a Story From Start to Finish | World of Writing - […] of plotting stories. One of the resources the Facebook Writers pointed to was an article outlining the Three Act…

- Structure, Showing, Description and Setting | Writing Craft Elements | A Youth and the Sea - […] most, if not all, people agree should be present in a story. These can be summed up nicely in…

- 7 Tips Menulis Buku Agar Diterima Penerbit - […] daftar isi dan tentukan hal-hal apa saja yang akan kamu bahas dengan sistematis, yaitu dari bab awal, pertengahan sampai…

- The Only Climax Development Resources You Will Ever Need – Chimera-Ocean - […] 5. The Write Practice […]

- NaNo Plot Week: Plot Structure Resources – Just another WordPress site - […] A Writer’s Cheatsheet to Plot and Structure […]

- NaNoWriMo Prep Resources - […] Plot Structure from The Write Practice. […]

- Guia 9: Pirâmide de Freytag – Toca do Escritor - […] A Writer’s Cheatsheet to Plot and Structure […]

- Writing Links Round Up 7/8-7/12 – B. Shaun Smith - […] A Writer’s Cheatsheet to Plot and Structure […]

- How Studying Plot Structure Makes Editing Smoother • Megan Cutler - […] most commonly used plot structure in media today is the Three Act Structure. It consists of a beginning (usually…

- How to Write a Book Using Microsoft Word - […] and uncluttered. There are a ton of apps and programs out there that will allow you to keep your…

- How to Write Your Memoir Like a Novel – Magic Reading - […] For a quick guide, Matt Heron has a great Writer’s Cheat Sheet to Plot and Structure here. […]

- 100 Writing Practice Lessons & Exercises - […] to write a good story? Our top plot and structure lessons will […]

- Character Development: Create Characters that Readers Love - […] get them out of trouble, and provides chances for reflection. A mainstay of the hero’s journey plot structure, in…

- What Is Plot? The 5 Elements of Plot and How to Use Them - […] how do you achieve this amazing plot structure? There are a few simple questions to ask yourself about every…

- What Is a Narrative Device: 9 Types of Narrative Devices - […] do you tell a story? Not how do you construct a story, or how do you structure and plot…

- 9 Types of Narrative Devices – Lederto.com Blog - […] do you tell a story? Not how do you construct a story, or how do you structure and plot…

- How will you utilize the advice from this post? - […] do you tell a story? Not how do you construct a story, or how do you structure and plot…

- The Pros and Cons of Plotters and Pantsers - […] A Writer’s Cheatsheet to Plot and Structure […]

- How the Rising Action Works in a Story: Definition and Examples of This Dramatic Structure Element - […] Pyramid is one of the most common frameworks for story structure. Formulated by Gustav Freytag in 1863, this concept,…

- The Incomplete Story of the 2008 Housing Crisis – (Im)Possibilities - […] Source:https://thewritepractice.com/plot-structure/ […]

- Tips on How to Be a Specialist – Writers Corp Blog - […] rollercoaster gives us a great analogy for the structure of a story. Imagine you set off on this rollercoaster. You…

- Five Act Structure: Definition, Origin, Examples, and Whether You Should Use It In Your Writing - - […] and climax, but does so in a simplified, less arbitrary way. It also fits better with other plot structures,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

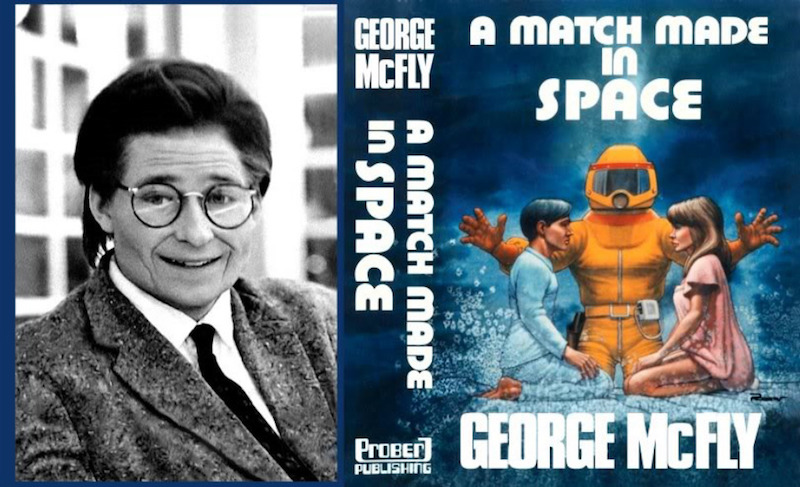

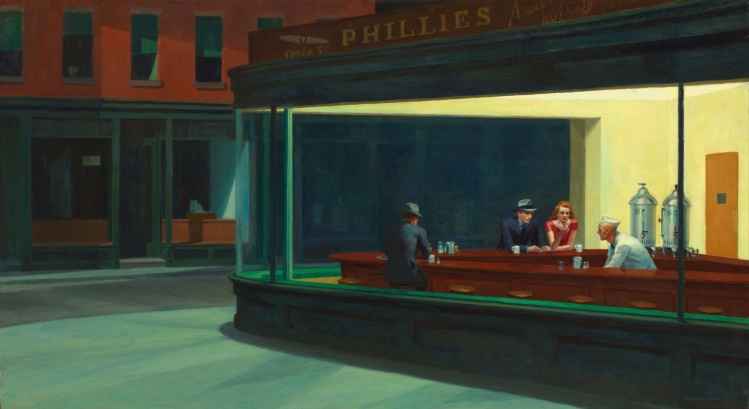

50 Fictional Writers, Ranked

The best and worst from literature, film, & tv.

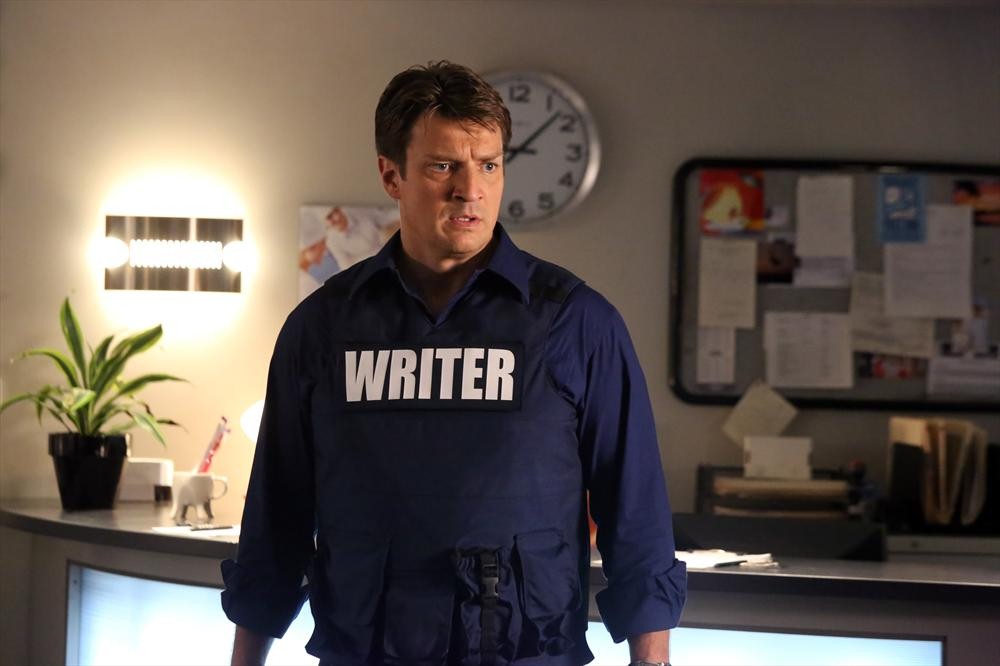

Everyone knows that writers love to write about writers. In fact, if an alien had to guess which profession was most common on earth based on our media alone—well, honestly it would probably be Detective, or Cop or something, but Writer would be up there too. So which fictional writers should we most avidly promote to our future alien overlords? I have no idea, but here I’ve taken a look at 50 favorite writers from film, literature and TV (and their many intersections). I’ve limited the list to fictional writers of literature—that is, I have excluded both journalists (yes, even Rory) and screenwriters. This is really only because I had to draw the line somewhere or wind up writing this list for the rest of time, and no one wants that, least of all my family. I also excluded biopics and other works in which real-world authors appear with their real-world names, though if a fictional character is simply based on a real writer, I found that to be admissible. As far as the rankings go, well, it’s not always easy to tell who is a good writer and who isn’t, especially when we’re talking about imaginary abilities. Besides, most fictional writers are either extremely bad or extremely good—at least according to their creators. Let’s just say I’ve gone with my gut.

Author bio: Tom Selleck is a crime writer who has had writer’s block for four years, and starts haunting local courtrooms to look for material. There he finds and falls for a young woman accused of murder and offers to be her alibi—and also starts writing about her, of course. Roger Ebert, who gave this movie .5 stars, sums up Blackwood’s writing style this way :

One of the minor curiosities of the movie is why the Selleck character is such a bad writer. His prose is a turgid flow of cliche and stereotype, and when we catch a glimpse of his computer screen, we can’t help noticing that he writes only in capital letters. Although the movie says he’s rich because of a string of best sellers, on the evidence this is the kind of author whose manuscripts are returned with a form letter.

Representative excerpt: “Despite the dozens of ravishing creatures begging to be part of his life, Swift had lived alone since his wife . . . was incinerated several years before, when the microwave went berserk during a thunderstorm.”

Author bio: The high school guidance counselor who is only semi-secretly writing the Next Great American Romance Novel during work hours: Undulating with desire, Adrian removes her red crimson cape at the sight of Reginald’s stiff and . . . Judith!

Literary wisdom: “Quivering member. I like that.”

Author bio: Spike goes through a hell of a transition over the many years of his life and undeath—and I don’t just mean the vampire thing, or the soul thing. As a youth, William the Bloody was mocked for his “bloody awful poetry.” Later, he worked out his feelings by killing a lot of people. But in the very last episode of Angel , facing destruction, Spike finally gets his standing ovation. It’s . . . surprisingly touching! If only that made the poetry better.

Classic slam poem:

My soul is wrapped in harsh repose Midnight descends in raven-colored clothes But soft. Behold! A sunlight beam Cutting a swath of glimmering gleam My heart expands, ’tis grown a bulge in it Inspired by your beauty . . . effulgent.”

Author bio: Of course Riverdale ‘s resident misfit gets the job of being the writer—a charming little meta-intrusion. Jughead claims that he is writing “Riverdale’s very own In Cold Blood .” Well, as you can see from the excerpt below, In Cold Blood it ain’t , but his hat is cute.

Opening lines: “Our story is about a town, a small town, and the people who live in the town. From a distance, it presents itself like so many other small towns all over the world. Safe. Decent. Innocent. Get closer, though, and you start seeing the shadows underneath. The name of our town is Riverdale.”

Author bio: Jimmy is a British writer and extreme narcissist living in Los Angeles and working on following up his poorly received Congratulations, You’re Dying with a new project, “the first truly literary erotic novel since Portnoy’s Complaint .” Apparently, it has a few too many descriptions of semen on stockings.

Literary wisdom: “Writing is very seldom actual writing. Maybe on the outside it looks as though I’m drinking and playing darts and eating craisins out of a bag in my pocket, but this is part of the process. It’s all writing. And I need you to respect my process.”

Author bio: In the first season of The Affair , Noah is a semi-successful (read: one okay book out) novelist who . . . has an affair. His first book is called A Person Who Visits a Place , to which I can only say . . . lol. In the second season, he publishes a novel, Descent , that gets him nominated for a PEN/Faulkner award, hailed as “the new bad boy of American letters,” and turns him into a bestseller—which is not even the most far-fetched part. The actual most far-fetched part is that he successfully gets a woman’s number with the line “Is there a green light at the end of your dock, Daisy?”, or maybe that his publicist drops the bomb that . . . Jonathan Franzen wants to meet him. Cool!

Excerpt from Descent : “They were driving fast. Out of the corner of his eye, he saw an old boat painted blue, resting on the side of the road, dilapidated, rotting as if the air itself was corrosive.”

Author bio: Shouldn’t really be on this list, because she’s a whiny newspaper columnist who writes one column a week and somehow lives a lavish, fashionista lifestyle. I guess she eventually turns her columns into a memoir-ish book (and at least according to Wikipedia, she goes on to write several more, with horrible, horrible names like MEN-hattan and I Do! Do I? ), and I don’t want to get emails about how I missed her, so here she is.

One of the many things Carrie wonders: “I used to think those people who sat alone at Starbucks writing on their laptops were pretentious posers. Now I know–they’re people who have recently moved in with someone. As I looked around, I wondered how many of them were mid-fight, like myself.”

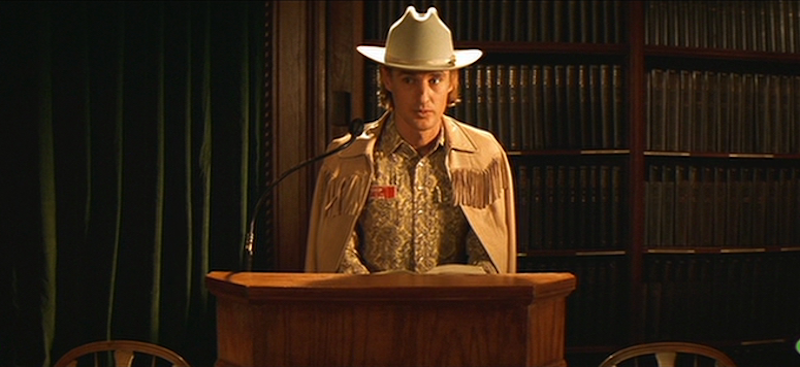

Author bio: Assistant professor of English literature at Brooks College, who hit the big-time with his second novel, Old Custer . Literary legend has it that Anderson wrote Cash to be a sort of fusion of Cormac McCarthy and Jay McInerney. (Plus fringe, I suppose.) Grew up with a family of geniuses. Especially not a genius. No, she didn’t even have to think about it.

Elevator pitch: “Well, everyone knows Custer died at Little Bighorn. What this book presupposes is . . . maybe he didn’t?”

Author bio: Rory isn’t here, so you’ll have to content yourself with Rory’s Best Boyfriend, who also happened to be a writer—coincidence? I think not. After escaping Stars Hollow, Jess writes a novel (which sounds suspiciously Beat-ish), and publishes it with a small press—years later, it is he who suggests that Rory write her memoir. A novelist and a muse!

Literary repartee: “Hey, I’ve read Jane Austen . . . and I think she would have liked Bukowski.”

Author(s) bio: In middle age, Bernard is a writer gone to seed—but Joan is a writer on the ascendant. Needless to say, they get divorced.

Harsh but fair: “What is it about high school? You read all the worst books by good writers.”

Author bio: Misanthropic, young, narcissistic Philip has sold his second novel, and is primed to become a Famous and Important writer. But waiting for it to get published is intolerable to him, and every person or responsibility making demands on his time drives him to anger. Enter his idol, legendary writer Ike Zimmerman, who offers him respite at his summer home. This is not a film that will make you like writers, but if you already know a few, you’re likely to laugh at them.

Advice from Ike: “You’ll need a country retreat if you want to get anything done.”

Author bio: Former therapist and cultist who emerges to write a tell-all book about it (this being more or less the opposite of a vow of silence, I’d say). Her publisher wants more “feeling” but I think he’s probably just being sexist.

The bottom line: “They believe the world ended.”

Author bio: An American writer of pulp Westerns who gets mighty involved in his attempt to clear a friend’s name in Allied-occupied Vienna.

Telling exchange:

POPESCU: Can I ask is Mr. Martins engaged in a new book? MARTINS: Yes, it’s called The Third Man . POPESCU: A novel, Mr. Martins? MARTINS: It’s a murder story. I’ve just started it. It’s based on fact. POPESCU: Are you a slow writer, Mr. Martins? MARTINS: Not when I get interested. POPESCU: I’d say you were doing something pretty dangerous this time. MARTINS: Yes? POPESCU: Mixing fact and fiction. MARTINS: Should I make it all fact? POPESCU: Why no, Mr. Martins. I’d say stick to fiction, straight fiction. MARTINS: I’m too far along with the book, Mr. Popescu. POPESCU: Haven’t you ever scrapped a book, Mr. Martins? MARTINS: Never.

Author bio: A punk literary poet of the ’90s—or so everyone thinks, anyway. Willing to help out needy and deluded young writers by publishing their work in his new anthology: Shit Poems: An Anthology of Bad Verse .

Literary wisdom: “Love . . . love until you hate. Then learn to hate your love. Then forgive your hate for loving it.”

Author bio: The totally together author of a “disturbingly popular” but soon-to-be-cancelled young adult series who—while on deadline, mind you—decides to jet off on a bizarre pilgrimage to her childhood home, hoping to win back her (married) ex-boyfriend and (presumably) her own long-past young adult life.

Key excerpt: “Just as Kendall hit send , a message from Ryan popped up like magic. It couldn’t be denied, they had textual chemistry .”

Author bio: All through Girls , people wondered: is Hannah Horvath supposed to be a good writer ? She doesn’t seem like a good writer—but she gets into the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. She writes an e-book—but it disintegrates. She gets a job writing advertorials for GQ —but she fails at that. She gets published in the Modern Love column, and in the end, she gets a pretty unlikely job! So, maybe?

So say we all: “My persona’s very witty and narcissistic.”

Author bio: Your typical alcoholic writer type, who accepts a winter position at the Overlook in the hopes of fixing up his life—and (of course) finding time to work. It does not go that well!

Authorial compulsion: “He would write it because the Overlook had enchanted him—could any other explanation be so simple or so true? He would write it for the reason he felt that all great literature, fiction and nonfiction, was written: truth comes out, in the end it always comes out. He would write it because he felt he had to.”

Author bio: Accidentally inseminated virgin with dreams of writing—who makes her dreams come true, getting an MFA, getting a job at a publishing house, getting discovered, and publishing her first novel, a historical romance based on her own life called Snow Falling , which (like several other fictional novels on this list) you can read (as ghostwritten by Caridad Pineiro)—Nicole Chung even reviewed it at The Washington Post . But that first book was met with middling reviews in-world too, and in season four, Jane fixates on bad reviews and suffers from writer’s block. Life isn’t easy when you’re a writer . . . or when you’re constantly beset by telenovela-style drama at every turn.

The strangely familiar opening to Snow Falling : “Josephine Galena Valencia always did things the right way and in the right order. At the ripe old age of twenty-three Josephine had finalized her master plan, and nothing was going to keep her from accomplishing it: find a job as a tutor, finish a novel, and marry Martin. Or so she thought . . . ”

Author bio: An obvious alter ego for Louisa May Alcott herself, Jo is a strong-willed tomboy who loves to read and write. She writes plays and short stories in her youth, and later goes to seek success as a writer in New York City. In the end, she gives up writing and gets married (though to the man of her choice, not to the man she is “supposed” to be with, which I guess makes it fine), but then again, later, in Jo’s Boys , Alcott tells us that Jo “fell back on the long-disused pen as the only thing she could do to fill up the gaps in the income. A book for girls being wanted by a certain publisher, she hastily scribbled a little story describing a few scenes and adventures in the lives of herself and her sisters . . . and with very slight hope of success, sent it out to seek its fortune.” Well, it certainly found its fortune.

Words to live by: “I like good strong words that mean something.”

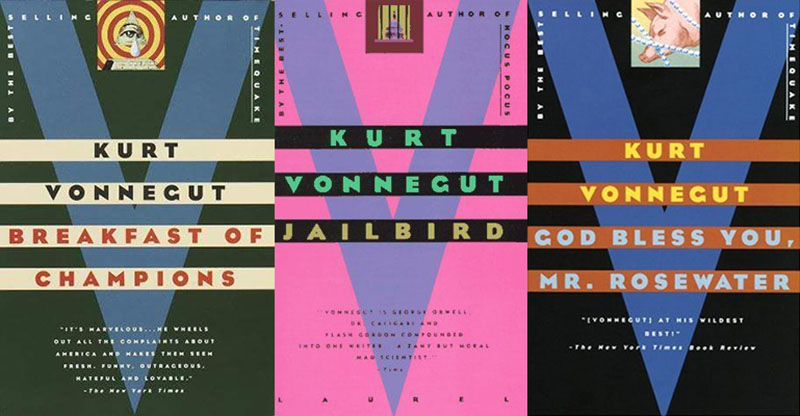

Author bio: Prolific but mostly unsuccessful writer of cheap sci-fi novels (including Venus on the Half-Shell , which was adapted from the fragment in God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater into a full-length novel by Philip José Farmer), named in homage to Theodore Sturgeon (who was much more successful than Trout), but whose personal details change mysteriously from book to book.

When the tupelo Goes poop-a-lo I’ll come back to youp-a-lo

Author bio: As the author of The Philosophy of Time Travel , she is probably the only person who truly understands this movie.

Essential wisdom: “Every creature on this earth dies alone.”

Author bio: A writer who always kills her main characters, but is suffering from writer’s block when it comes to how to kill her most recent one, is astonished to find that he is a flesh-and-blood Will Ferrell (however that works), but decides for the integrity of the novel—her masterpiece!—she’s going to have to kill him anyway. It is only after Will Ferrell accepts his fate, self-sacrificing in the name of art, that Eiffel loses her nerve and only seriously injures him instead—at the expense of her novel’s brilliance. His watch, however, does in fact die a horrible death.

On her murderous novel: “Like anything worth writing, it came inexplicably and without method.”

Author bio: Once a farm girl, Gabrielle ran away to join the mighty Xena on her travels, and eventually became a good fighter as well as a bard—telling stories, singing, and writing down all of their adventures on scrolls (when Xena doesn’t use her paper for wiping with)—though often with some amount of epic embellishment. Gabrielle’s scrolls were eventually rediscovered by the descendants of her, Xena, and Joxer in the 1940s, and then in 1996, were used to pitch a cool television show called Xena: Warrior Princess . . .

Notable excerpt: “I sing of the wrath of Callisto, the pain of Gabrielle, and the courage of Xena and the inevitable mystery of a friendship as immortal as the gods.”

Author bio: A 13-year-old girl who has elaborate fantasies about butts, making out, zombies, and her friends, and often writes erotic fan fiction (or erotic friend fiction) about one, or several, or all of these at once.

An excerpt from “Buttloose,” a piece of Erotic Friend Fiction: “It was lunchtime at Wagstaff. Touching butts had been banned by the horrible headmaster Frond. Suddenly, Tina Belcher appeared in the doorway. She knew what she had to do. She grabbed Jimmy Jr.’s butt, and changed the world.”

Author bio: An inmate in Litchfield Penitentiary, and author of a popular (in Litchfield) erotic science fiction series entitled The Time Hump Chronicles , which stars a time-traveling robo-doll named Edwina, who must choose between that “wuss” Gilly and the dual-penised Space Admiral Rodcocker, whose semen is remarkably high in protein. It becomes so popular that the other inmates begin hounding her for more, and even writing their own fan fiction. And it’s not just the other inmates—real life writer Alyssa Cole recreated (created?) some of the Chronicles here .

Summary: “It’s not just sex, it’s love. It’s two people connecting . . . with four other people, and aliens.”

Author bio: Purvis is a home-schooled teenager who writes science fiction stories. When he goes to a youth writer’s conference, he gets to meet his literary idol, Dr. Ronald Chevalier. He even shows him his manuscript— Yeast Lords —which Chevalier promptly steals, rewrites, and publishes as his own. Two other kids he meets at the conference steal his story too—well, they buy it, but not without some shady business—and turn adapt it into a terrible low-budget film. After assaulting his one-time hero, Purvis is in jail. But never fear: his mom is on her way to save the day.

Excerpt from Yeast Lords : “The Nad Lab was a cold white room. Bronco, the last of the Yeast Lords, lay spread eagle, strapped to a medical pod. Someone had stolen his yeast and he had gone totally apeshit.”

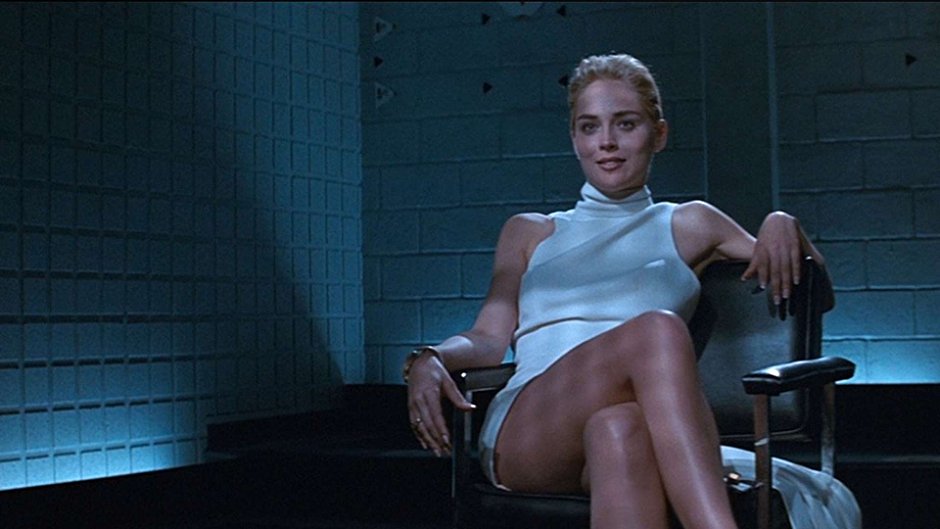

Author bio: A Very Sexy crime novelist who is being investigated for a murder that oddly parallels one from her fiction. She continues to write novels that very closely hew to the illegal and murderous events of her life, but no one really catches her because she is not wearing underwear.

The kiss-off: “I finished my book. Didn’t you hear me? Your character’s dead. Good-bye. What do you want? Flowers? I’ll send you an autographed copy.”

Author bio: A rare human in this universe, who majored in literature and equine studies at Boston University. She is the author of Secretariat: a Life , The Rise and Fall of Strongheart , and Tracing Zippo Pine Bar , a New York Times bestseller, and was also the ghostwriter BoJack Horseman’s autobiography, One Trick Pony , which won a Golden Globe for Best Comedy or Musical, even though it was a book.

Explanation for leaking: “I know you’re mad and you have every right to be, but you gotta read some of these comments. People love you! And they’re gonna love you even more when they read the rest of my book!”

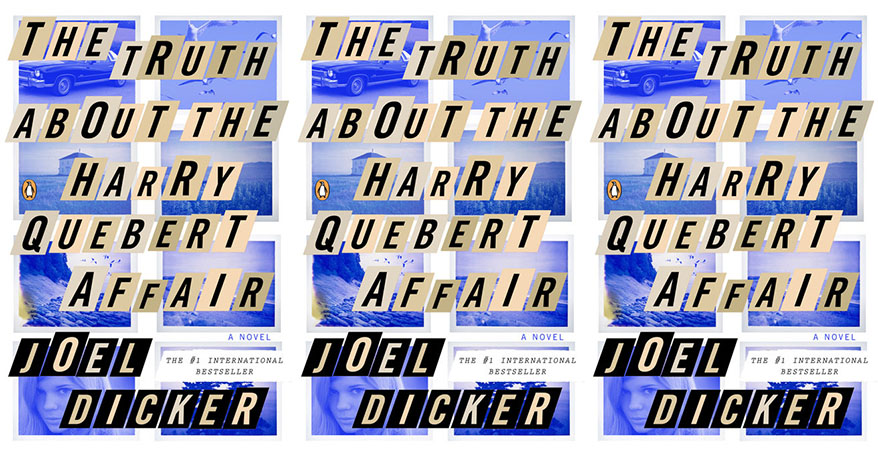

Author bio: We’ve heard it before: a celebrated debut novelist who can’t get his second book off the ground—until he goes to visit his old mentor and professor, who may or may not have killed a teenage girl! Marcus will solve the mystery and mine it for ideas at the same time.

Marcus on writer’s block: “My terror of the blank page did not hit me suddenly; it crept over me bit by bit, as if my brain were slowly freezing up. I told myself that inspiration would return tomorrow, or the day after, or perhaps the day after that. But the days and weeks and months went by, and inspiration never returned. . . I began to understand that glory was a Gorgon whose visage could turn you to stone if you failed to continue performing.”

Author bio: A professor in Pittsburgh desperately trying to write a follow-up to his award-winning debut, published seven years previous, but failing to kill his darlings—like, any of them. (Not to mention the fact that his private life is disintegrating, nor the surrealist crime with which he becomes involved.)

Fatal flaw: “Motivation, inspiration were not the problem; on the contrary I was always cheerful and workmanlike at the typewriter and had never suffered from what’s called writer’s block; I didn’t believe in it. The problem, if anything, was precisely the opposite. I had too much to write: too many fine and miserable buildings to construct and streets to name and clock towers to set chiming, too many characters to raise up from the dirt like flowers whose petals I peeled down to the intricate frail organs within, too many terrible genetic and fiduciary secrets to dig up and bury and dig up again, too many divorces to grant, heirs to disinherit, trysts to arrange, letters to misdirect into evil hands, innocent children to slay with rheumatic fever, women to leave unfulfilled and hopeless, men to drive to adultery and theft, fires to ignite at the hearts of ancient houses. It was about a single family and it stood, as of that morning, at two thousand six hundred and eleven pages, each of them revised and rewritten a half dozen times. And yet for all of those years, and all of those words expended in charting the eccentric paths of my characters through the violent blue heavens I had set them to cross, they had not even reached their zeniths. I was nowhere near the end.”

Author bio: When we first meet Briony, she is a 13-year-old who likes to write; when we last hear from her, she is a novelist in her late 70s. What passes between first appears to be merely the story of her life and her family’s life, but in the final pages, all is revealed: it is she who is the author of what we have just read—and things did not turn out quite the way she said.

On her fixed-up autofiction: “I like to think that it isn’t weakness or evasion, but a final act of kindness, a stand against oblivion and despair, to let my lovers live and to unite them at the end. I gave them happiness, but I was not so self-serving as to let them forgive me. Not quite, not yet.”

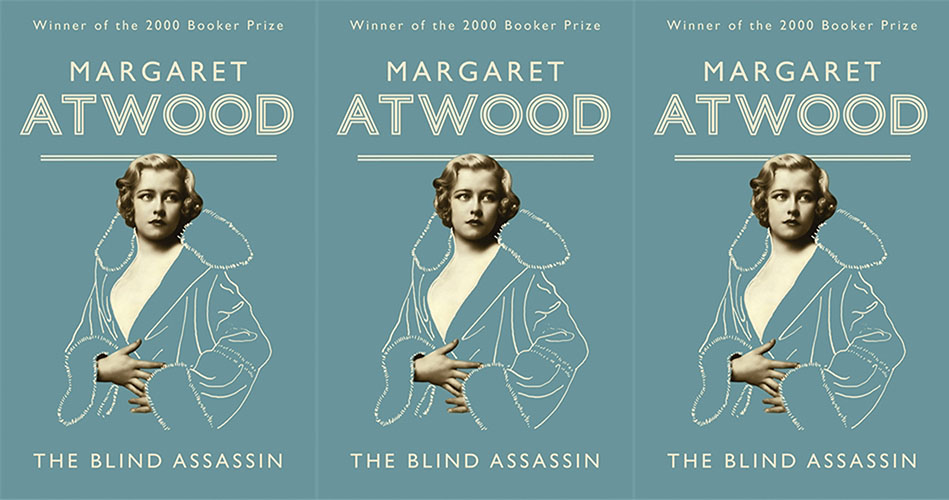

Author bio: The very unhappily married true author of the novel-within-a-novel, about young Communist Alex Thomas (himself a science fiction author), which she published under her sister’s name—but won’t go to her grave without making the truth known.

On writing her abusive husband: “I’ve failed to convey Richard, in any rounded sense. He remains a cardboard cutout. I know that. I can’t truly describe him, I can’t get a precise focus: he’s blurred, like the face in some wet, discarded newspaper.”