- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.6: Solving Absolute Value Equations and Inequalities

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 6238

Learning Objectives

- Review the definition of absolute value.

- Solve absolute value equations.

- Solve absolute value inequalities.

Absolute Value Equations

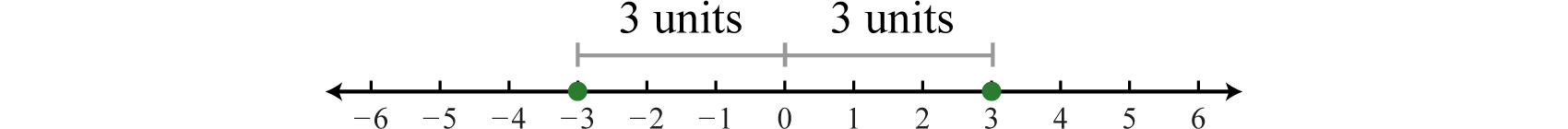

Recall that the absolute value 63 of a real number \(a\), denoted \(|a|\), is defined as the distance between zero (the origin) and the graph of that real number on the number line. For example, \(|−3|=3\) and \(|3|=3\).

In addition, the absolute value of a real number can be defined algebraically as a piecewise function.

\(| a | = \left\{ \begin{array} { l } { a \text { if } a \geq 0 } \\ { - a \text { if } a < 0 } \end{array} \right.\)

Given this definition, \(|3| = 3\) and \(|−3| = − (−3) = 3\).Therefore, the equation \(|x| = 3\) has two solutions for \(x\), namely \(\{±3\}\). In general, given any algebraic expression \(X\) and any positive number \(p\):

\(\text{If}\: | X | = p \text { then } X = - p \text { or } X = p\)

In other words, the argument of the absolute value 64 \(X\) can be either positive or negative \(p\). Use this theorem to solve absolute value equations algebraically.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\):

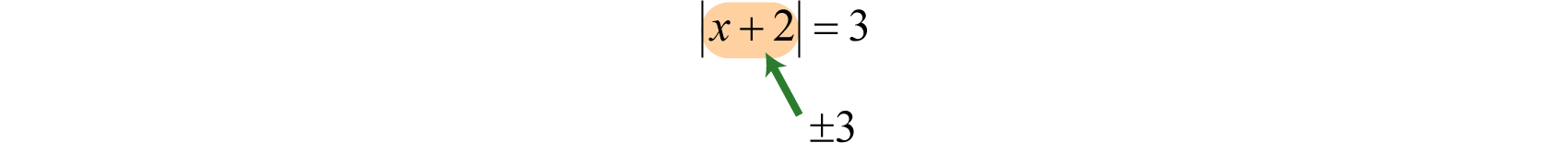

Solve: \(|x+2|=3\).

In this case, the argument of the absolute value is \(x+2\) and must be equal to \(3\) or \(−3\).

Therefore, to solve this absolute value equation, set \(x+2\) equal to \(±3\) and solve each linear equation as usual.

\(\begin{array} { c } { | x + 2 | = 3 } \\ { x + 2 = - 3 \quad \quad\text { or } \quad\quad x + 2 = 3 } \\ { x = - 5 \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad x = 1 } \end{array}\)

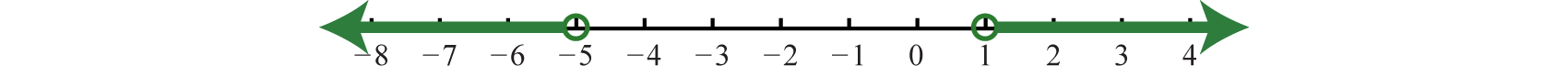

The solutions are \(−5\) and \(1\).

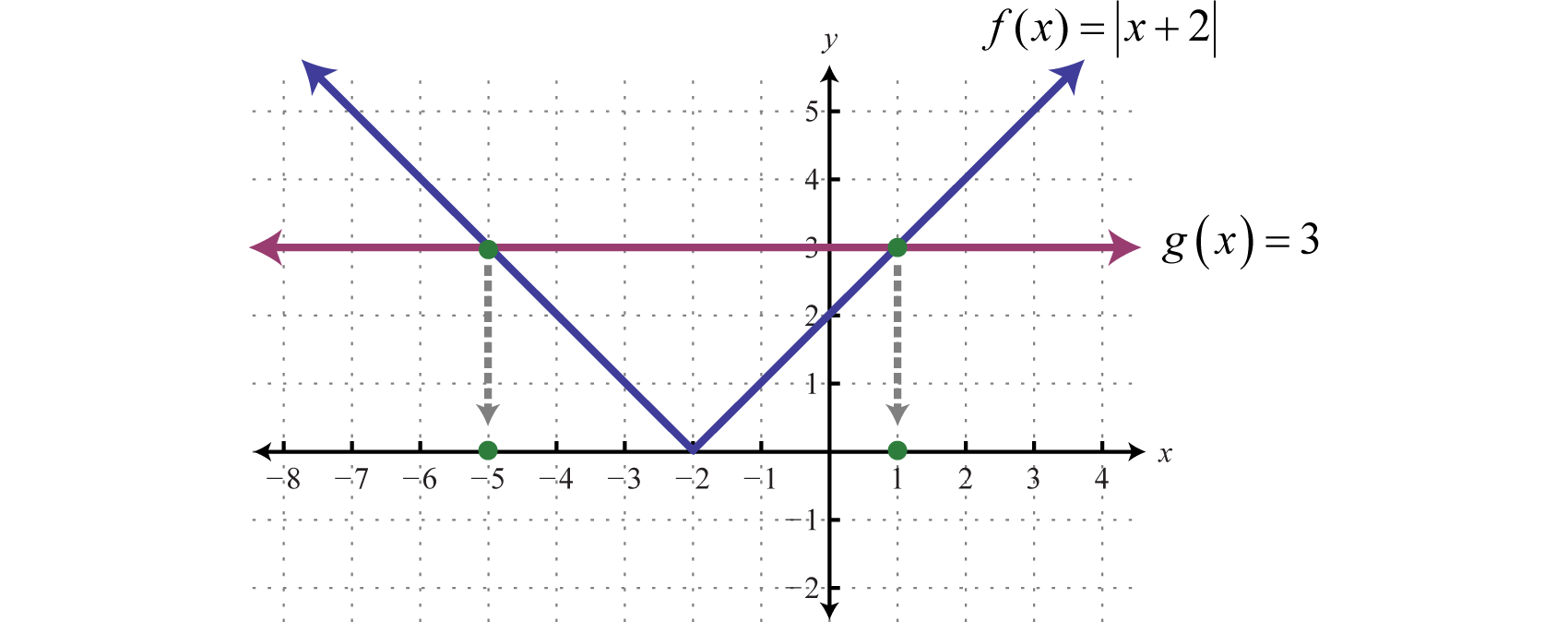

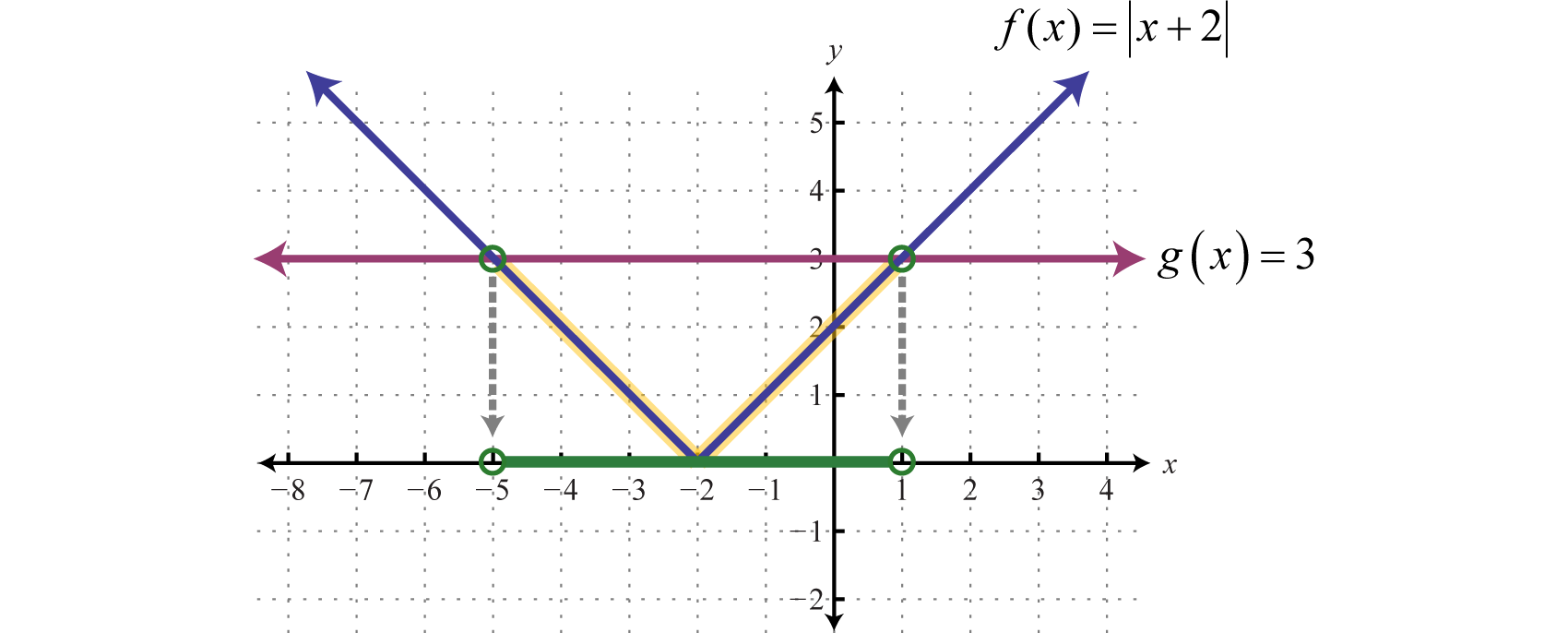

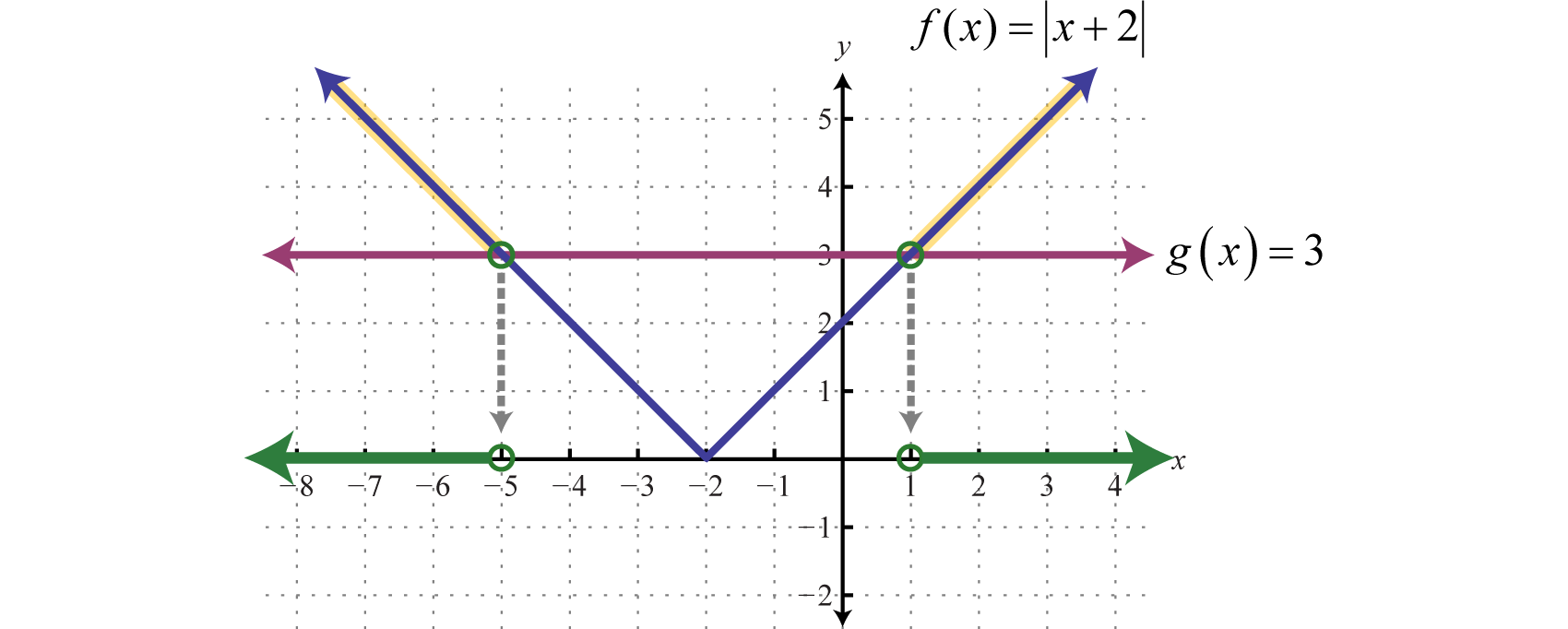

To visualize these solutions, graph the functions on either side of the equal sign on the same set of coordinate axes. In this case, \(f (x) = |x + 2|\) is an absolute value function shifted two units horizontally to the left, and \(g (x) = 3\) is a constant function whose graph is a horizontal line. Determine the \(x\)-values where \(f (x) = g (x)\).

From the graph we can see that both functions coincide where \(x = −5\) and \(x = 1\). The solutions correspond to the points of intersection.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\):

Solve: \(| 2 x + 3 | = 4\).

Here the argument of the absolute value is \(2x+3\) and can be equal to \(-4\) or \(4\).

\(\begin{array} { r l } { | 2 x + 3 | } & { = \quad 4 } \\ { 2 x + 3 = - 4 } & { \text { or }\quad 2 x + 3 = 4 } \\ { 2 x = - 7 } & \quad\quad\:\: { 2 x = 1 } \\ { x = - \frac { 7 } { 2 } } & \quad\quad\:\: { x = \frac { 1 } { 2 } } \end{array}\)

Check to see if these solutions satisfy the original equation.

The solutions are \(-\frac{7}{2}\) and \(\frac{1}{2}\).

To apply the theorem, the absolute value must be isolated. The general steps for solving absolute value equations are outlined in the following example.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\):

Solve: \(2 |5x − 1| − 3 = 9\).

Step 1 : Isolate the absolute value to obtain the form \(|X| = p\).

\(\begin{aligned} 2 | 5 x - 1 | - 3 & = 9 \:\:\:\color{Cerulean} { Add\: 3\: to\: both\: sides. } \\ 2 | 5 x - 1 | & = 12 \:\:\color{Cerulean} { Divide\: both\: sides\: by\: 2 } \\ | 5 x - 1 | & = 6 \end{aligned}\)

Step 2 : Set the argument of the absolute value equal to \(±p\). Here the argument is \(5x − 1\) and \(p = 6\).

\(5 x - 1 = - 6 \text { or } 5 x - 1 = 6\)

Step 3 : Solve each of the resulting linear equations.

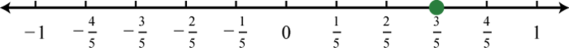

\(\begin{array} { r l } { 5 x - 1 = - 6 \quad\:\:\text { or } \quad\quad5 x - 1 } & { \:\:\:\:\:\:= 6 } \\ { 5 x = - 5 }\quad\:\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\: & { 5 x = 7 } \\ { x = - 1 } \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\:\:& { x = \frac { 7 } { 5 } } \end{array}\)

Step 4 : Verify the solutions in the original equation.

The solutions are \(-1\) and \(\frac{7}{5}\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Solve: \(2 - 7 | x + 4 | = - 12\).

www.youtube.com/v/G0EjbqreYmU

Not all absolute value equations will have two solutions.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\):

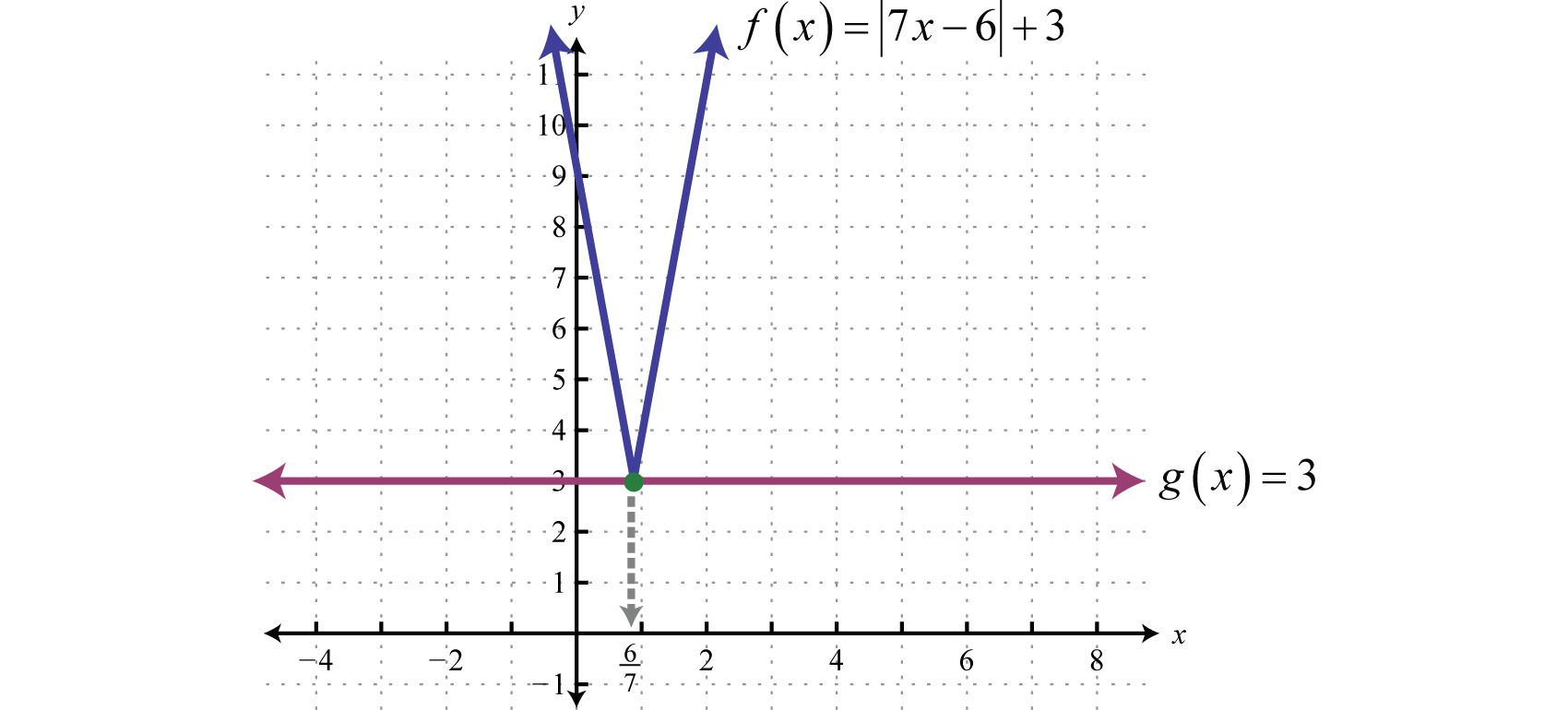

Solve: \(| 7 x - 6 | + 3 = 3\).

Begin by isolating the absolute value.

\(\begin{array} { l } { | 7 x - 6 | + 3 = 3 \:\:\:\color{Cerulean} { Subtract\: 3\: on\: both\: sides.} } \\ { \quad | 7 x - 6 | = 0 } \end{array}\)

Only zero has the absolute value of zero, \(|0| = 0\). In other words, \(|X| = 0\) has one solution, namely \(X = 0\). Therefore, set the argument \(7x − 6\) equal to zero and then solve for \(x\).

\(\begin{aligned} 7 x - 6 & = 0 \\ 7 x & = 6 \\ x & = \frac { 6 } { 7 } \end{aligned}\)

Geometrically, one solution corresponds to one point of intersection.

The solution is \(\frac{6}{7}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\):

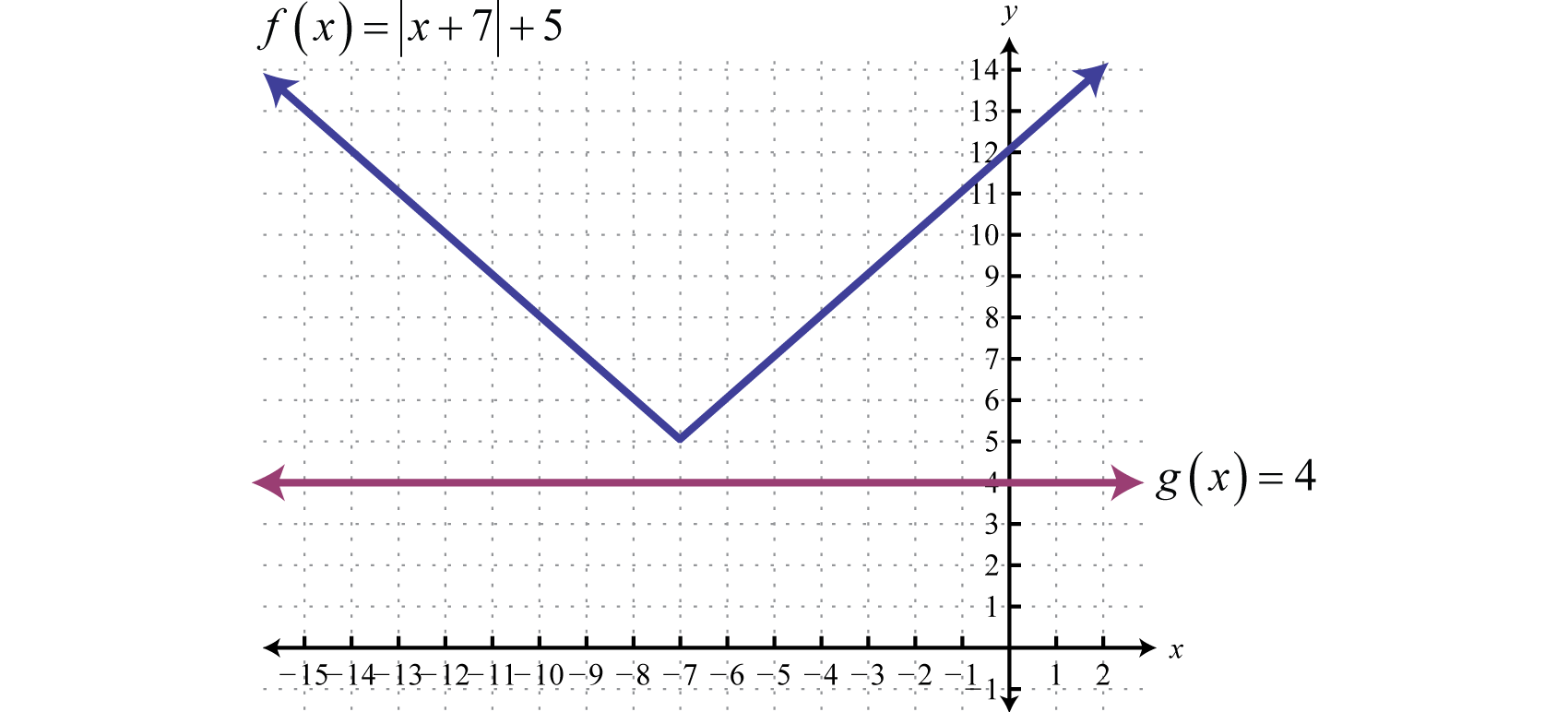

Solve: \(|x+7|+5=4\).

\(\begin{aligned} | x + 7 | + 5 & = 4 \:\:\color{Cerulean} { Subtract \: 5\: on\: both\: sides.} \\ | x + 7 | & = - 1 \end{aligned}\)

In this case, we can see that the isolated absolute value is equal to a negative number. Recall that the absolute value will always be positive. Therefore, we conclude that there is no solution. Geometrically, there is no point of intersection.

There is no solution, \(Ø\).

If given an equation with two absolute values of the form \(| a | = | b |\), then \(b\) must be the same as \(a\) or opposite. For example, if \(a=5\), then \(b = \pm 5\) and we have:

\(| 5 | = | - 5 | \text { or } | 5 | = | + 5 |\)

In general, given algebraic expressions \(X\) and \(Y\):

\(\text{If} | X | = | Y | \text { then } X = - Y \text { or } X = Y\).

In other words, if two absolute value expressions are equal, then the arguments can be the same or opposite.

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\):

Solve: \(| 2 x - 5 | = | x - 4 |\).

Set \(2x-5\) equal to \(\pm ( x - 4 )\) and then solve each linear equation.

\(\begin{array} { c } { | 2 x - 5 | = | x - 4 | } \\ { 2 x - 5 = - ( x - 4 ) \:\: \text { or }\:\: 2 x - 5 = + ( x - 4 ) } \\ { 2 x - 5 = - x + 4 }\quad\quad\quad 2x-5=x-4 \\ { 3 x = 9 }\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad \quad\quad x=1 \\ { x = 3 \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\:\:\:\:} \end{array}\)

To check, we substitute these values into the original equation.

As an exercise, use a graphing utility to graph both \(f(x)= |2x-5|\) and \(g(x)=|x-4|\) on the same set of axes. Verify that the graphs intersect where \(x\) is equal to \(1\) and \(3\).

The solutions are \(1\) and \(3\).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Solve: \(| x + 10 | = | 3 x - 2 |\).

www.youtube.com/v/CskWmsQCBMU

Absolute Value Inequalities

We begin by examining the solutions to the following inequality:

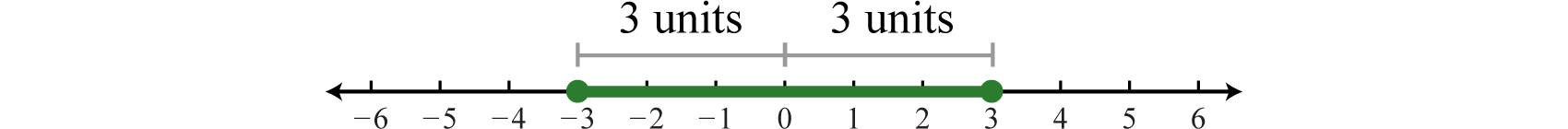

\(| x | \leq 3\)

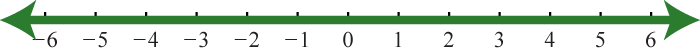

The absolute value of a number represents the distance from the origin. Therefore, this equation describes all numbers whose distance from zero is less than or equal to \(3\). We can graph this solution set by shading all such numbers.

Certainly we can see that there are infinitely many solutions to \(|x|≤3\) bounded by \(−3\) and \(3\). Express this solution set using set notation or interval notation as follows:

\(\begin{array} { c } { \{ x | - 3 \leq x \leq 3 \} \color{Cerulean} { Set\: Notation } } \\ { [ - 3,3 ] \quad \color{Cerulean}{ Interval \:Notation } } \end{array}\)

In this text, we will choose to express solutions in interval notation. In general, given any algebraic expression \(X\) and any positive number \(p\):

\(\text{If} | X | \leq p \text { then } - p \leq X \leq p\).

This theorem holds true for strict inequalities as well. In other words, we can convert any absolute value inequality involving " less than " into a compound inequality which can be solved as usual.

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\):

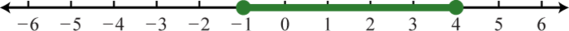

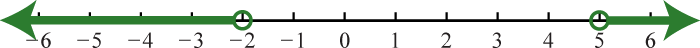

Solve and graph the solution set: \(|x+2|<3\).

Bound the argument \(x+2\) by \(−3\) and \(3\) and solve.

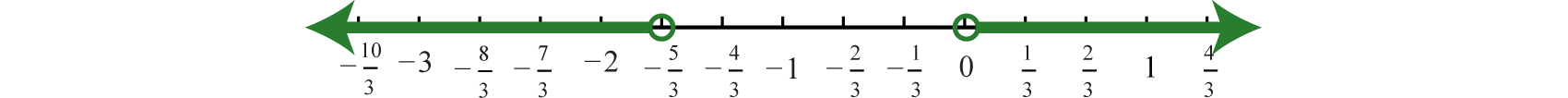

\(\begin{array} { c } { | x + 2 | < 3 } \\ { - 3 < x + 2 < 3 } \\ { - 3 \color{Cerulean}{- 2}\color{Black}{ <} x + 2 \color{Cerulean}{- 2}\color{Black}{ <} 3 \color{Cerulean}{- 2} } \\ { - 5 < x < 1 } \end{array}\)

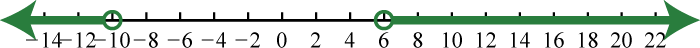

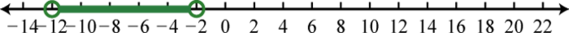

Here we use open dots to indicate strict inequalities on the graph as follows.

Using interval notation, \((−5,1)\).

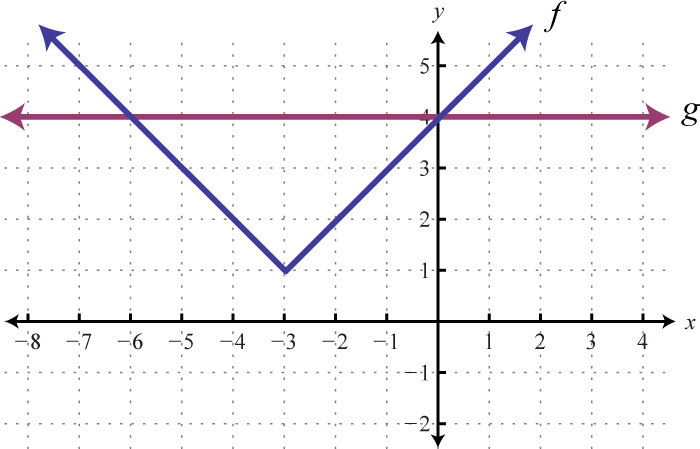

The solution to \(| x + 2 | < 3\) can be interpreted graphically if we let \(f ( x ) = | x + 2 |\) and \(g(x)=3\) and then determine where \(f ( x ) < g ( x )\) by graphing both \(f\) and \(g\) on the same set of axes.

The solution consists of all \(x\)-values where the graph of \(f\) is below the graph of \(g\). In this case, we can see that \(|x + 2| < 3\) where the \(x\)-values are between \(−5\) and \(1\). To apply the theorem, we must first isolate the absolute value.

Example \(\PageIndex{8}\):

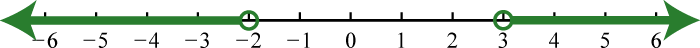

Solve: \(4 |x + 3| − 7 ≤ 5\).

\(\begin{array} { c } { 4 | x + 3 | - 7 \leq 5 } \\ { 4 | x + 3 | \leq 12 } \\ { | x + 3 | \leq 3 } \end{array}\)

Next, apply the theorem and rewrite the absolute value inequality as a compound inequality.

\(\begin{array} { c } { | x + 3 | \leq 3 } \\ { - 3 \leq x + 3 \leq 3 } \end{array}\)

\(\begin{aligned} - 3 \leq x + 3 \leq & 3 \\ - 3 \color{Cerulean}{- 3} \color{Black}{ \leq} x + 3 \color{Cerulean}{- 3} & \color{Black}{ \leq} 3 \color{Cerulean}{- 3} \\ - 6 \leq x \leq 0 \end{aligned}\)

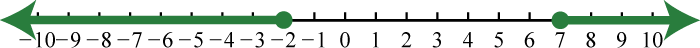

Shade the solutions on a number line and present the answer in interval notation. Here we use closed dots to indicate inclusive inequalities on the graph as follows:

Using interval notation, \([−6,0]\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Solve and graph the solution set: \(3 + | 4 x - 5 | < 8\).

Interval notation: \((0, \frac{5}{2})\)

www.youtube.com/v/sX6ppL2Fbq0

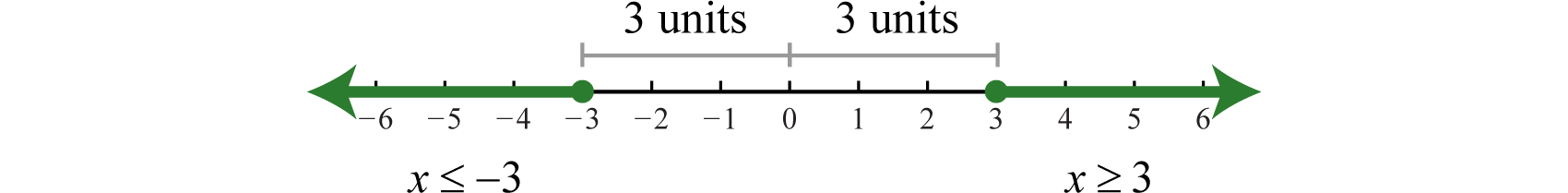

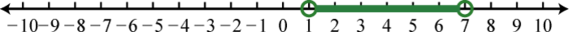

Next, we examine the solutions to an inequality that involves " greater than ," as in the following example:

\(| x | \geq 3\)

This inequality describes all numbers whose distance from the origin is greater than or equal to \(3\). On a graph, we can shade all such numbers.

There are infinitely many solutions that can be expressed using set notation and interval notation as follows:

\(\begin{array} { l } { \{ x | x \leq - 3 \text { or } x \geq 3 \} \:\:\color{Cerulean} { Set\: Notation } } \\ { ( - \infty , - 3 ] \cup [ 3 , \infty ) \:\:\color{Cerulean} { Interval\: Notation } } \end{array}\)

In general, given any algebraic expression \(X\) and any positive number \(p\):

\(\text{If} | X | \geq p \text { then } X \leq - p \text { or } X \geq p\).

The theorem holds true for strict inequalities as well. In other words, we can convert any absolute value inequality involving “ greater than ” into a compound inequality that describes two intervals.

Example \(\PageIndex{9}\):

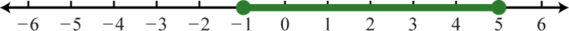

Solve and graph the solution set: \(|x+2|>3\).

The argument \(x+2\) must be less than \(−3\) or greater than \(3\).

\(\begin{array} { c } { | x + 2 | > 3 } \\ { x + 2 < - 3 \quad \text { or } \quad x + 2 > 3 } \\ { x < - 5 }\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\: x>1 \end{array}\)

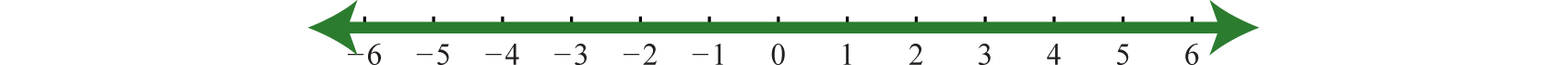

Using interval notation, \((−∞,−5)∪(1,∞)\).

The solution to \(|x + 2| > 3\) can be interpreted graphically if we let \(f (x) = |x + 2|\) and \(g (x) = 3\) and then determine where \(f(x) > g (x)\) by graphing both \(f\) and \(g\) on the same set of axes.

The solution consists of all \(x\)-values where the graph of \(f\) is above the graph of \(g\). In this case, we can see that \(|x + 2| > 3\) where the \(x\)-values are less than \(−5\) or are greater than \(1\). To apply the theorem we must first isolate the absolute value.

Example \(\PageIndex{10}\):

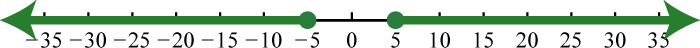

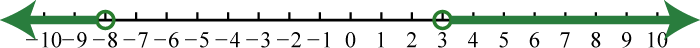

Solve: \(3 + 2 |4x − 7| ≥ 13\).

\(\begin{array} { r } { 3 + 2 | 4 x - 7 | \geq 13 } \\ { 2 | 4 x - 7 | \geq 10 } \\ { | 4 x - 7 | \geq 5 } \end{array}\)

\(\begin{array} &\quad\quad\quad\quad\:\:\:|4x-7|\geq 5 \\ 4 x - 7 \leq - 5 \quad \text { or } \quad 4 x - 7 \geq 5 \end{array}\)

\(\begin{array} { l } { 4 x - 7 \leq - 5 \text { or } 4 x - 7 \geq 5 } \\ \quad\:\:\:\:{ 4 x \leq 2 } \quad\quad\quad\:\:\: 4x\geq 12\\ \quad\:\:\:\:{ x \leq \frac { 2 } { 4 } } \quad\quad\quad\quad x\geq 3 \\ \quad\quad{ x \leq \frac { 1 } { 2 } } \end{array}\)

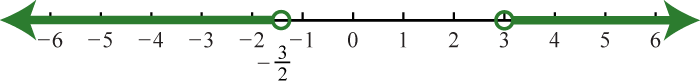

Shade the solutions on a number line and present the answer using interval notation.

Using interval notation, \((−∞,\frac { 1 } { 2 }]∪[3,∞)\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Solve and graph: \(3 | 6 x + 5 | - 2 > 13\).

Using interval notation, \(\left( - \infty , - \frac { 5 } { 3 } \right) \cup ( 0 , \infty )\)

www.youtube.com/v/P6HjRz6W4F4

Up to this point, the solution sets of linear absolute value inequalities have consisted of a single bounded interval or two unbounded intervals. This is not always the case.

Example \(\PageIndex{11}\):

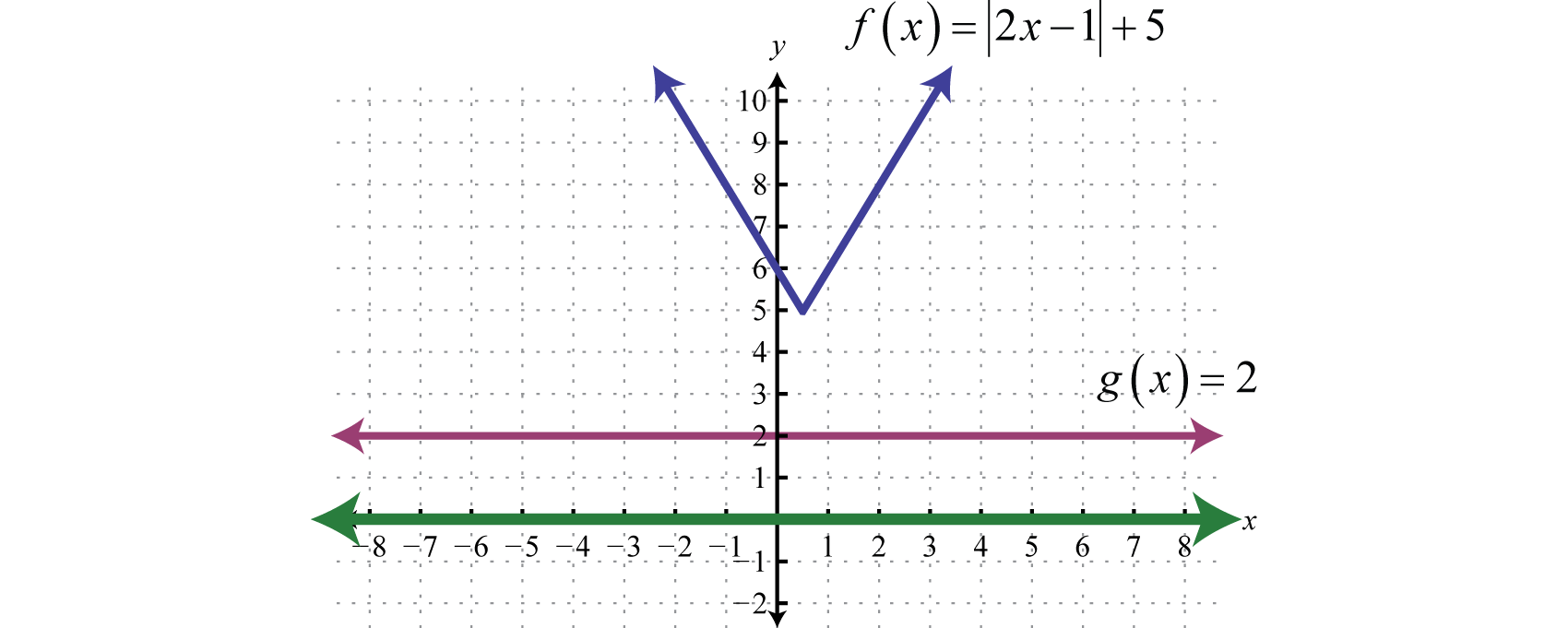

Solve and graph: \(|2x−1|+5>2\).

\(\begin{array} { c } { | 2 x - 1 | + 5 > 2 } \\ { | 2 x - 1 | > - 3 } \end{array}\)

Notice that we have an absolute value greater than a negative number. For any real number x the absolute value of the argument will always be positive. Hence, any real number will solve this inequality.

Geometrically, we can see that \(f(x)=|2x−1|+5\) is always greater than \(g(x)=2\).

All real numbers, \(ℝ\).

Example \(\PageIndex{12}\):

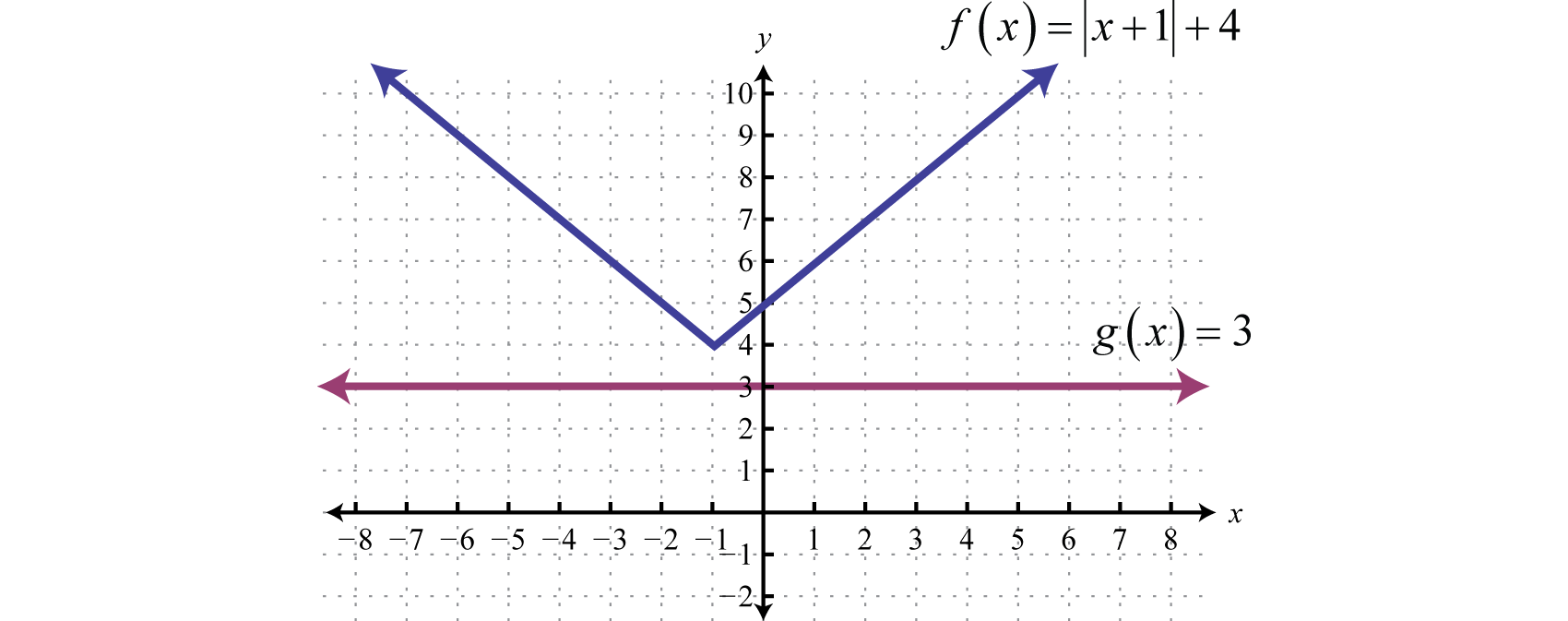

Solve and graph: \(|x+1|+4≤3\).

\(\begin{array} { l } { | x + 1 | + 4 \leq 3 } \\ { | x + 1 | \leq - 1 } \end{array}\)

In this case, we can see that the isolated absolute value is to be less than or equal to a negative number. Again, the absolute value will always be positive; hence, we can conclude that there is no solution.

Geometrically, we can see that \(f(x)=|x+1|+4\) is never less than \(g(x)=3\).

Answer : \(Ø\)

In summary, there are three cases for absolute value equations and inequalities. The relations \(=, <, \leq, > \) and \(≥\) determine which theorem to apply.

Case 1: An absolute value equation:

Case 2: an absolute value inequality involving " less than .", case 3: an absolute value inequality involving " greater than .", key takeaways.

- To solve an absolute value equation, such as \(|X| = p\), replace it with the two equations \(X = −p\) and \(X = p\) and then solve each as usual. Absolute value equations can have up to two solutions.

- To solve an absolute value inequality involving “less than,” such as \(|X| ≤ p\), replace it with the compound inequality \(−p ≤ X ≤ p\) and then solve as usual.

- To solve an absolute value inequality involving “greater than,” such as \(|X| ≥ p\), replace it with the compound inequality \(X ≤ −p\) or \(X ≥ p\) and then solve as usual.

- Remember to isolate the absolute value before applying these theorems.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

- \(|x| = 9\)

- \(|x| = 1\)

- \(|x − 7| = 3\)

- \(|x − 2| = 5\)

- \(|x + 12| = 0\)

- \(|x + 8| = 0\)

- \(|x + 6| = −1\)

- \(|x − 2| = −5\)

- \(|2y − 1| = 13\)

- \(|3y − 5| = 16\)

- \(|−5t + 1| = 6\)

- \(|−6t + 2| = 8\)

- \(\left| \frac { 1 } { 2 } x - \frac { 2 } { 3 } \right| = \frac { 1 } { 6 }\)

- \(\left| \frac { 2 } { 3 } x + \frac { 1 } { 4 } \right| = \frac { 5 } { 12 }\)

- \(|0.2x + 1.6| = 3.6\)

- \(|0.3x − 1.2| = 2.7\)

- \(| 5 (y − 4) + 5| = 15\)

- \(| 2 (y − 1) − 3y| = 4\)

- \(|5x − 7| + 3 = 10\)

- \(|3x − 8| − 2 = 6\)

- \(9 + |7x + 1| = 9\)

- \(4 − |2x − 3| = 4\)

- \(3 |x − 8| + 4 = 25\)

- \(2 |x + 6| − 3 = 17\)

- \(9 + 5 |x − 1| = 4\)

- \(11 + 6 |x − 4| = 5\)

- \(8 − 2 |x + 1| = 4\)

- \(12 − 5 |x − 2| = 2\)

- \(\frac{1}{2} |x − 5| − \frac{2}{3} = −\frac{1}{6}\)

- \(\frac { 1 } { 3 } \left| x + \frac { 1 } { 2 } \right| + 1 = \frac { 3 } { 2 }\)

- \(−2 |7x + 1| − 4 = 2\)

- \(−3 |5x − 3| + 2 = 5\)

- \(1.2 |t − 2.8| − 4.8 = 1.2\)

- \(3.6 | t + 1.8| − 2.6 = 8.2\)

- \(\frac{1}{2} |2 (3x − 1) − 3| + 1 = 4\)

- \(\frac{2}{3} |4 (3x + 1) − 1| − 5 = 3\)

- \(|5x − 7| = |4x − 2|\)

- \(|8x − 3| = |7x − 12|\)

- \(|5y + 8| = |2y + 3|\)

- \(|7y + 2| = |5y − 2|\)

- \(|5 (x − 2)| = |3x|\)

- \(|3 (x + 1)| = |7x|\)

- \(\left| \frac { 2 } { 3 } x + \frac { 1 } { 2 } \right| = \left| \frac { 3 } { 2 } x - \frac { 1 } { 3 } \right|\)

- \(\left| \frac { 3 } { 5 } x - \frac { 5 } { 2 } \right| = \left| \frac { 1 } { 2 } x + \frac { 2 } { 5 } \right|\)

- \(|1.5t − 3.5| = |2.5t + 0.5|\)

- \(|3.2t − 1.4| = |1.8t + 2.8|\)

- \(|5 − 3 (2x + 1)| = |5x + 2|\)

- \(|3 − 2 (3x − 2)| = |4x − 1|\)

1. \(−9, 9\)

3. \(4, 10\)

5. \(−12\)

7. \(Ø\)

9. \(−6, 7\)

11. \(−1, \frac{7}{5}\)

13. \(1, \frac{5}{3}\)

15. \(−26, 10\)

17. \(0, 6\)

19. \(0, \frac{14}{5}\)

21. \(−\frac{1}{7}\)

23. \(1, 15\)

25. \(Ø\)

27. \(−3, 1\)

29. \(4, 6\)

31. \(Ø\)

33. \(−2.2, 7.8\)

35. \(−\frac{1}{6}, \frac{11}{6}\)

37. \(1, 5\)

39. \(−\frac{5}{3}, −\frac{11}{7}\)

41. \(\frac{5}{4} , 5\)

43. \(−\frac{1}{13} , 1\)

45. \(−4, 0.75\)

47. \(0, 4\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Solve and graph the solution set. In addition, give the solution set in interval notation.

- Solve for \(x: p |ax + b| − q = 0\)

- Solve for \(x: |ax + b| = |p + q|\)

1. \(x = \frac { - b q \pm q } { a p }\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{7}\)

- \(|x| < 5\)

- \(|x| ≤ 2\)

- \(|x + 3| ≤ 1\)

- \(|x − 7| < 8\)

- \(|x − 5| < 0\)

- \(|x + 8| < −7\)

- \(|2x − 3| ≤ 5\)

- \(|3x − 9| < 27\)

- \(|5x − 3| ≤ 0\)

- \(|10x + 5| < 25\)

- \(\left| \frac { 1 } { 3 } x - \frac { 2 } { 3 } \right| \leq 1\)

- \(\left| \frac { 1 } { 12 } x - \frac { 1 } { 2 } \right| \leq \frac { 3 } { 2 }\)

- \(|x| ≥ 5\)

- \(|x| > 1\)

- \(|x + 2| > 8\)

- \(|x − 7| ≥ 11\)

- \(|x + 5| ≥ 0\)

- \(|x − 12| > −4\)

- \(|2x − 5| ≥ 9\)

- \(|2x + 3| ≥ 15\)

- \(|4x − 3| > 9\)

- \(|3x − 7| ≥ 2\)

- \(\left| \frac { 1 } { 7 } x - \frac { 3 } { 14 } \right| > \frac { 1 } { 2 }\)

- \(\left| \frac { 1 } { 2 } x + \frac { 5 } { 4 } \right| > \frac { 3 } { 4 }\)

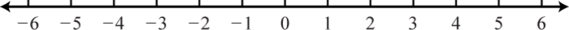

1. \(( - 5,5 )\);

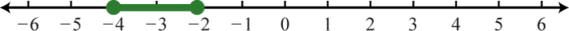

3. \([ - 4 , - 2 ]\);

5. \(\emptyset\);

7. \([ - 1,4 ]\);

9. \(\left\{ \frac { 3 } { 5 } \right\}\);

11. \([ - 1,5 ]\);

13. \(( - \infty , - 5 ] \cup [ 5 , \infty )\);

15. \(( - \infty , - 10 ) \cup ( 6 , \infty )\);

17. \(\mathbb { R }\);

19. \(( - \infty , - 2 ] \cup [ 7 , \infty )\);

21. \(\left( - \infty , - \frac { 3 } { 2 } \right) \cup ( 3 , \infty )\);

23. \(( - \infty , - 2 ) \cup ( 5 , \infty )\);

Exercise \(\PageIndex{8}\)

Solve and graph the solution set.

- \(|3 (2x − 1)| > 15\)

- \(|3 (x − 3)| ≤ 21\)

- \(−5 |x − 4| > −15\)

- \(−3 |x + 8| ≤ −18\)

- \(6 − 3 |x − 4| < 3\)

- \(5 − 2 |x + 4| ≤ −7\)

- \(6 − |2x + 5| < −5\)

- \(25 − |3x − 7| ≥ 18\)

- \(|2x + 25| − 4 ≥ 9\)

- \(|3 (x − 3)| − 8 < −2\)

- \(2 |9x + 5| + 8 > 6\)

- \(3 |4x − 9| + 4 < −1\)

- \(5 |4 − 3x| − 10 ≤ 0\)

- \(6 |1 − 4x| − 24 ≥ 0\)

- \(3 − 2 |x + 7| > −7\)

- \(9 − 7 |x − 4| < −12\)

- \(|5 (x − 4) + 5| > 15\)

- \(|3 (x − 9) + 6| ≤ 3\)

- \(\left| \frac { 1 } { 3 } ( x + 2 ) - \frac { 7 } { 6 } \right| - \frac { 2 } { 3 } \leq - \frac { 1 } { 6 }\)

- \(\left| \frac { 1 } { 10 } ( x + 3 ) - \frac { 1 } { 2 } \right| + \frac { 3 } { 20 } > \frac { 1 } { 4 }\)

- \(12 + 4 |2x − 1| ≤ 12\)

- \(3 − 6 |3x − 2| ≥ 3\)

- \(\frac{1}{2} |2x − 1| + 3 < 4\)

- 2 |\frac{1}{2} x + \frac{2}{3} | − 3 ≤ −1\)

- \(7 − |−4 + 2 (3 − 4x)| > 5\)

- \(9 − |6 + 3 (2x − 1)| ≥ 8\)

- \(\frac { 3 } { 2 } - \left| 2 - \frac { 1 } { 3 } x \right| < \frac { 1 } { 2 }\)

- \(\frac { 5 } { 4 } - \left| \frac { 1 } { 2 } - \frac { 1 } { 4 } x \right| < \frac { 3 } { 8 }\)

1. \(( - \infty , - 2 ) \cup ( 3 , \infty )\);

3. \(( 1,7 )\);

5. \(( - \infty , 3 ) \cup ( 5 , \infty )\);

7. \(( - \infty , - 8 ) \cup ( 3 , \infty )\);

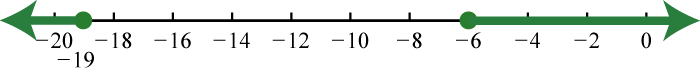

9. \(( - \infty , - 19 ] \cup [ - 6 , \infty )\);

11. \(\mathbb { R }\);

13. \(\left[ \frac { 2 } { 3 } , 2 \right]\);

15. \(( - 12 , - 2 )\);

17. \(( - \infty , 0 ) \cup ( 6 , \infty )\);

19. \([ 0,3 ]\);

21. \(\frac { 1 } { 2 }\);

23. \(\left( - \frac { 1 } { 2 } , \frac { 3 } { 2 } \right)\);

25. \(\left( 0 , \frac { 1 } { 2 } \right)\);

27. \(( - \infty , 3 ) \cup ( 9 , \infty )\);

Exercise \(\PageIndex{9}\)

Assume all variables in the denominator are nonzero.

- Solve for \(x\) where \(a, p > 0: p |ax + b| − q ≤ 0\)

- Solve for \(x\) where \(a, p > 0: p |ax + b| − q ≥ 0\)

1. \(\frac { - q - b p } { a p } \leq x \leq \frac { q - b p } { a p }\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{10}\)

Given the graph of \(f\) and \(g\), determine the \(x\)-values where:

(a) \(f ( x ) = g ( x )\)

(b) \(f ( x ) > g ( x )\)

(c) \(f ( x ) < g ( x )\)

1. (a) \(−6, 0\); (b) \((−∞, −6) ∪ (0, ∞)\); (c) \((−6, 0)\)

3. (a) \(Ø\); (b) \(ℝ\); (c) \(Ø\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{11}\)

- Make three note cards, one for each of the three cases described in this section. On one side write the theorem, and on the other write a complete solution to a representative example. Share your strategy for identifying and solving absolute value equations and inequalities on the discussion board.

- Make your own examples of absolute value equations and inequalities that have no solution, at least one for each case described in this section. Illustrate your examples with a graph.

1. Answer may vary

63 The distance from the graph of a number \(a\) to zero on a number line, denoted \(|a|\).

64 The number or expression inside the absolute value.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

For example, should you want to solve the equation \(|2x − 4| = 6\), you could divide both sides by 2 and apply the quotient property of absolute values. Distance Revisited Recall that for any real number x, the absolute value of x is defined as the distance between the real number x and the origin on the real line.

Step 2: Set the argument of the absolute value equal to ± p. Here the argument is 5x − 1 and p = 6. 5x − 1 = − 6 or 5x − 1 = 6. Step 3: Solve each of the resulting linear equations. 5x − 1 = − 6 or 5x − 1 = 6 5x = − 5 5x = 7 x = − 1 x = 7 5. Step 4: Verify the solutions in the original equation. Check x = − 1.