Writing your thesis and conducting a literature review

- Writing your thesis

- Your literature review

- Defining a research question

- Choosing where to search

Search strings

- Limiters and filters

- Developing inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Managing your search results

- Screening, evaluating and recording

- Snowballing and grey literature

- Further information and resources

The next step is to create your search strings. Each search string will represent a theme/concept of your research. Search strings are a combination of keywords that are synonymous or related terms, along with acronyms and variant spellings. Your aim is to capture as much of the relevant literature as possible and search strings will help you do that.

There are a number of tools and search operators that you can use to improve the efficacy of your search strings.

- Acronyms - If your keyword is also known by an acronym then both the full spelling and acronym should be searched, e.g., (“Armoured Fighting Vehicle” OR AFV).

- Wildcard - If your keyword can be spelt differently, e.g., UK/US variants, then use a wildcard to capture both variations, e.g., defen?e will return papers with both defense and defence spellings.

- Truncation - If your keyword could have several variant endings, then truncate it, e.g., technolog* will return papers with technology, technological, technologies, etc.

- Phrase-searching – if your keyword has two or more words, then you should enclose the keywords within double quotation marks. If you do not, the database/search engine will put an invisible ‘AND’ operator between each word, e.g., systems engineering will be read by the database/search engine as systems AND engineering. This means that both systems and engineering must appear in the search results, but not necessarily together in the context of systems engineering. To ensure systems engineering is returned in your results as a phrase, search for “systems engineering”.

Note: Not all databases search using the same syntax, check the search tips of the database to check they accept wildcards, truncation, phrase-searching, etc. and adjust your search string accordingly.

Combining your keywords and search strings: search operators

- OR - is used to combine synonyms, related terms, acronyms, etc. within search strings, e.g., (“Armo?red Fighting Vehicle*” OR AFV OR tank* OR “Infantry Fighting Vehicle*”) will return results where any one of these keywords appears. Using the OR operator expands your search results.

- AND – is used to combine search strings of different concepts/themes, e.g., (“Armo?red Fighting Vehicle*” OR AFV OR tank* OR “Infantry Fighting Vehicle*” OR IFV OR “Armo?red Personnel Carrier*” OR APC) AND (protect* OR securit* OR IED OR "improvised explosive device*") will return results where any one keyword from the first search string and any one keyword from the second search strings appears in the document. Using the AND operator will narrow down your search results.

- NOT/AND NOT – is used to eliminate keywords that you do not wish to appear in your search results, e.g., tank* NOT water will exclude results which contain the keyword water. Use this operator with caution, for example it is unlikely to exclude all results that mention water.

Watch this Boolean operators video to learn more about using them to connect your keywords and other commands such as quotation marks, question marks and asterisks which will all help you to improve your search results.

- Covid W/3 (PPE OR “personal protective equipment”) will return results where Covid appears within three words of PPE or “personal protective equipment”, regardless of the order of the words.

- Covid PRE/3 (PPE OR “personal protective equipment”) will return results where Covid appears first within three words of PPE or “personal protective equipment”.

Further guidance from Kings College London on advanced search techniques.

Search strategy

A search strategy is simply your search strings combined to address each of your review questions, to answer your overarching research topic. Search strings are usually combined with a Boolean operator or a proximity operator, as described above.

- << Previous: Keywords

- Next: Limiters and filters >>

- Last Updated: Feb 21, 2024 2:01 PM

- URL: https://library.cranfield.ac.uk/writing-your-thesis

- Search this site

- Systematic literature review

- Narrative Review

- Scoping Review

- Systematic Review

- Rapid Review

- Research question

Building your search string

- Optimal use of a literature database

- Fine-tuning your query

- Additional search methods

- Applications for literature review

- Support & contact

Combining keywords with Boolean operators

Conducting a good search requires a bit more than just putting single search terms in a search bar. In order to retrieve specific and targeted information about your topic, you need to logically combine search terms with each other. To do that, you use Boolean operators:

- AND: if you are looking for references in which both search terms appear;

- OR: if you are looking for references containing at least one of the search terms;

- NOT: if you are looking for references in which a particular search term does not occur.

Note: Be careful when using NOT; it may exclude relevant articles by inadvertently (false negatives). A suggestion here is: run the search with and without the NOT, and see the difference by comparing the results in your Search History: how many results are omitted? Are the results that are omitted relevant to your search or not? Based on this, you can decide whether or not the NOT is a useful addition to your search string.

How to build a search string:

- collect search terms and keywords by subtopic;

- combine them with OR;

- place the keywords between parentheses;

- put an AND between the subtopics

Generic example: (... OR ... OR ... OR ... OR ...) AND (... OR ... OR ... OR ...) AND (... OR ... OR ... OR ... OR ...)

With this, you have created a basic search string that you can use for multiple databases. For some databases, you can fine-tune the search string by adding thesaurus terms and/or search fields (see below).

More tips and suggestions

Several techniques exist for fine-tuning your search string. Note that databases often have their own 'rules'. It is advisable to check per database which 'rules' apply to the syntax of your query. These can be found in the HELP or FAQ section of the database in question.

Exact word combination If you only want to find search results that contain the search terms in exactly that order, place your search terms inside double quotation marks ("....."), e.g. "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder."

Pro tip: an exact word combination is actually a strict version of the Boolean AND operator, where the search terms must also occur in that particular order. Therefore, the order of the search terms is not arbitrary, but set by you.

Truncation is a technique that can be used to expand your search; the end of a search term is replaced by a truncation mark, also known as a wildcard. Doing so allows you to efficiently find word variants and thus expand your search. For example:

- child* = child, children, childhood, childhood, child-friendly, childs, child-like

- industr* = industry, industries, industrial

- genetic* = genetic, genetics

Truncation symbols may vary by database, but frequently used symbols include *, !, ? or #.

A wildcard is a symbol that replaces a letter of a word. This is especially useful when a word can be spelled several ways (but mean the same thing), such as in a British variant as an American variant. For example

- wom!n = woman, women

- colo?r = color, color

- latin?= latina, latinx, latine, latino, latines

Search fields When you enter your basic search string into the search bar, your search terms will generally be checked to see if they appear anywhere in the text of the article. This can potentially create a lot of noise. Limiting your search to a to specific search fields will make it more focused. Advanced Search allows you to search only certain fields, e.g. title and/or abstract, keywords, or subject.

For example, "language development disorder"[abstract] AND "primary school"[abstract] AND "teaching materials"[abstract].

Note that each database has its own configuration and search fields, so always tailor your search to the database!

Minilecture Smart search

Useful links and resources

- Useful links

See this link for a great visualization of a search string from a scoping paper .

If you have questions, please contact the Information Specialist Research of your research center , or go to support & contact for more information and advice.

[anchornavigation]

- University of Michigan Library

- Research Guides

Systematic Reviews

- Search Strategy

- Work with a Search Expert

- Covidence Review Software

- Types of Reviews

- Evidence in a Systematic Review

- Information Sources

Developing an Answerable Question

Creating a search strategy, identifying synonyms & related terms, keywords vs. index terms, combining search terms using boolean operators, a sr search strategy, search limits.

- Managing Records

- Selection Process

- Data Collection Process

- Study Risk of Bias Assessment

- Reporting Results

- For Search Professionals

Validated Search Filters

Depending on your topic, you may be able to save time in constructing your search by using specific search filters (also called "hedges") developed & validated by researchers in the Health Information Research Unit (HiRU) of McMaster University, under contract from the National Library of Medicine. These filters can be found on

- PubMed’s Clinical Queries & Health Services Research Queries pages

- Ovid Medline’s Clinical Queries filters or here

- Embase & PsycINFO

- EBSCOhost’s main search page for CINAHL (Clinical Queries category)

- HiRU’s Nephrology Filters page

- American U of Beirut, esp. for " humans" filters .

- Countway Library of Medicine methodology filters

- InterTASC Information Specialists' Sub-Group Search Filter Resource

- SIGN (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network) filters page

Why Create a Sensitive Search?

In many literature reviews, you try to balance the sensitivity of the search (how many potentially relevant articles you find) & specificit y (how many definitely relevant articles you find ), realizing that you will miss some. In a systematic review, you want a very sensitive search: you are trying to find any potentially relevant article. A systematic review search will:

- contain many synonyms & variants of search terms

- use care in adding search filters

- search multiple resources, databases & grey literature, such as reports & clinical trials

PICO is a good framework to help clarify your systematic review question.

P - Patient, Population or Problem: What are the important characteristics of the patients &/or problem?

I - Intervention: What you plan to do for the patient or problem?

C - Comparison: What, if anything, is the alternative to the intervention?

O - Outcome: What is the outcome that you would like to measure?

Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis.

5-SPICE: the application of an original framework for community health worker program design, quality improvement and research agenda setting.

A well constructed search strategy is the core of your systematic review and will be reported on in the methods section of your paper. The search strategy retrieves the majority of the studies you will assess for eligibility & inclusion. The quality of the search strategy also affects what items may have been missed. Informationists can be partners in this process.

For a systematic review, it is important to broaden your search to maximize the retrieval of relevant results.

Use keywords: How other people might describe a topic?

Identify the appropriate index terms (subject headings) for your topic.

- Index terms differ by database (MeSH, or Medical Subject Headings , Emtree terms , Subject headings) are assigned by experts based on the article's content.

- Check the indexing of sentinel articles (3-6 articles that are fundamental to your topic). Sentinel articles can also be used to test your search results.

Include spelling variations (e.g., behavior, behaviour ).

Both types of search terms are useful & both should be used in your search.

Keywords help to broaden your results. They will be searched for at least in journal titles, author names, article titles, & article abstracts. They can also be tagged to search all text.

Index/subject terms help to focus your search appropriately, looking for items that have had a specific term applied by an indexer.

Boolean operators let you combine search terms in specific ways to broaden or narrow your results.

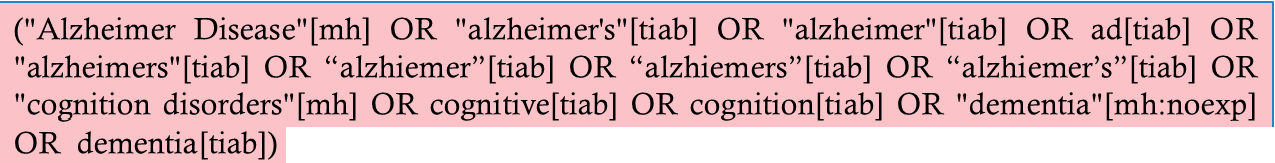

An example of a search string for one concept in a systematic review.

In this example from a PubMed search, [mh] = MeSH & [tiab] = Title/Abstract, a more focused version of a keyword search.

A typical database search limit allows you to narrow results so that you retrieve articles that are most relevant to your research question. Limit types vary by database & include:

- Article/publication type

- Publication dates

In a systematic review search, you should use care when applying limits, as you may lose articles inadvertently. For more information, see, particularly regarding language & format limits. Cochrane 2008 6.4.9

Discover our blogs

Defence and Security

Energy and Sustainability

Environment

Manufacturing and Materials

School of Management

Transport Systems

Systematic Literature Review – Identifying your search terms and constructing your search strings

Our previous posts on the systematic review have looked at getting started and selecting your sources . In this post we will look at the next fundamental stage:

- Identifying your search terms and constructing your search strings

Identifying your search terms

Having decided which sources you need to search, the next step in the systematic literature review process is to identify your search terms or keywords:

- These may be individual words such as customer, or phrases like “ customer research management”. Note: if phrases are not inserted inside double quotation marks, each word will be searched for individually rather than as a phrase, e.g., customer AND service AND management instead of “customer service management”.

- Your search terms should consist of not just the words which are included in your research question, but also synonyms (e.g. customer OR consumer), spelling variants , and any relevant concepts .

- Spelling variants such as o rganization and organisation can be dealt with by using the wildcard symbol (‘?’) in place of a single letter. For example, a search for ‘ organi?ation’ will look for both spellings of the word. Note: not all sources accept the wildcard symbol. Check the search tips of your resource for guidance.

- Use the truncation symbol (‘*’) at the end of a whole or partial word to search for variant word endings. For example, strateg * will find strategy, strategies, strategic etc. Note: not all sources accept the truncation symbol. Check the search tips of your resource for guidance.

When choosing your keywords, remember that the aim is to identify all relevant literature without making the search so broad that you retrieve lots of irrelevant material. For example, the synonyms for customer in the example below have been combined into a search string using the word OR:

(consumer OR customer OR client OR user)

Note that words such as individual or subject have not been included as these words are homographs and would produce a lot of irrelevant material. Homographs are words that are spelled the same but have more than one meaning. You should also only use ‘sensible synonyms’. For example, in gender studies you would not search using terms such as ‘gentleman’ or ‘lady’. These terms are unlikely to be used by the scholars in your field.

Constructing your search strings

Once you have chosen your keywords and phrases, they can be combined into search strings. Some examples of search strings are given below:

String 1 (“supply chain*” OR “supply network*” OR “demand chain*” OR “demand network*” OR “value chain*” OR “value network*”)

String 2 (“lead time compression” OR “lead time reduction” OR “cycle time compression” OR “cycle time reduction” OR “dwell time compression” OR “dwell time reduction”)

String 3 (agil* OR “quick response” OR speed*)

Note that each search string only contains synonyms or related terms.

Now that you have created your search strings, you are ready to construct your search strategies.

Other blog posts you may find useful

- Systematic Literature Review – Where do I begin?

- Systematic Literature Review – Selecting your Sources

Because of the complexity of this process, we recommend that before embarking on a systematic literature review you speak with your Librarian who will be happy to provide guidance.

Feature image from Pixabay

Mandy Smith

Written By: Mandy Smith

Mandy has worked for Cranfield Library Service since 2004 and is a Research Support Librarian supporting researchers and research students at Cranfield Defence and Security and the School of Management. She teaches a range of study skills as well as helping researchers use the resources they need to find information. She provides advice and support on REF and funder compliance, open access publishing and other research-related topics.

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like….

Mandy Smith 2024-03-28T16:52:22+00:00 28/03/2024 | Tags: barrington , knl , literature search , slr , SOMLibrary , systematic review , web-mirc-articles |

Our previous posts on the systematic review have looked at getting started and selecting your sources. In this post we will look at the next fundamental stage: Identifying your search terms and constructing your search ...

Navigating the World of Robotics: My Journey at Cranfield University

Alice Kirkaldy 2024-03-28T11:51:36+00:00 28/03/2024 | Tags: alumni , postgraduate life , robotics |

Hey there, I'm Manideep, and I'm thrilled to share my experience pursuing an MSc in Robotics at Cranfield University. Let me take you through my journey and how Cranfield became the ...

Exploring safer and smarter airports with the Applied Artificial Intelligence MSc group design project

Antonia Molloy 2024-03-26T15:14:10+00:00 26/03/2024 | Tags: AAI , aerospace , applied artificial intelligence , Applied Artificial Intelligence MSc , engineering , group design project , manufacturing , smart airports |

Artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have experienced rapid development in recent years, spanning from large language models (LLMs) to generative artificial intelligence (GAI). These cutting-edge advancements have significantly impacted various aspects of ...

My aerospace manufacturing journey at Cranfield University

Alice Kirkaldy 2024-03-25T17:51:26+00:00 25/03/2024 | Tags: aerospace manufacturing , alumni , student experience , student journey |

Hey there, I'm Abhishek and I wanted to share my journey into aerospace manufacturing, guided by my experiences at Cranfield University. Let's dive into how this remarkable institution shaped my career ...

Changes to Library Services over Easter, 29 March – 1 April

Karyn Meaden-Pratt 2024-03-25T12:27:41+00:00 25/03/2024 | Tags: barrington , easter , knl , opening hours , SOMLibrary |

Libraries on the Cranfield site Both Kings Norton Library and the School of Management Library (Building 111, first floor) will be open 24/7 over the Easter weekend. You will be able to use the study ...

How to present well as a group

Karyn Meaden-Pratt 2024-03-18T17:36:02+00:00 22/03/2024 | Tags: barrington , group projects , knl , presentation skills , SOMLibrary , study skills |

You will have put a lot of work into your research or project and want to show everyone what you have achieved or discovered, so you need to impart this knowledge as clearly as possible. ...

Sign up for more information about studying master’s and research degrees at Cranfield

Privacy overview.

Systematic Review

- Systematic reviews

Being systematic

Search terms, choosing databases, finding additional resources.

- Search techniques

- Systematically search databases

- Appraisal & synthesis

- Reporting findings

- Systematic review tools

Searching literature systematically is useful for all types of literature reviews!

However, if you are writing a systematic literature review the search needs to be particularly well planned and structured to ensure it is:

- comprehensive

- transparent

These help ensure bias is eliminated and the review is methodologically sound.

To achieve the above goals, you will need to:

- create a search strategy and ensure it is reviewed by your research group

- document each stage of your literature searching

- report each stage of quality appraisal

Identify the key concepts in your research question

The first step in developing your search strategy is identifying the key concepts your research question covers.

- A preliminary search is often done to understand the topic and to refine your research question.

Identify search terms

Use an iterative process to identify useful search terms for conducting your search.

- Brainstorm keywords and phrases that can describe each concept you have identified in your research question.

- Create a table to record these keywords

- Select your keywords carefully

- Check against inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Repeated testing is required to create a robust search strategy for a systematic review

- Run your search on your primary database and evaluate the first page of records to see how suitable your search is

- Identify reasons for irrelevant results and adjust your keywords accordingly

- Consider whether it would be useful to use broader or narrower terms for your concepts

- Identify keywords in relevant results that you could add to your search to retrieve more relevant resources

Using a concept map or a mind map may help you clarify concepts and the relationships between or within concepts. Watch these YouTube videos for some ideas:

- How to make a concept map (by Lucidchart)

- Make sense of this mess world - mind maps (by Sheng Huang)

Example keywords table:

Research question: What is the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and depression in mothers during the perinatal period?

Revise your strategy/search terms until :

- the results match your research question

- you are confident you will find all the relevant literature on your topic

See Creating search strings for information on how to enter your search terms into databases.

Example search string (using Scopus's Advanced search option) for the terms in the above table:

(TITLE-ABS-KEY("advserse childhood experienc*" OR ACE OR "childhood trauma") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY("perinatal depress*" OR "postpartum depress*" OR "postnatal depress*" OR "maternal mental health" OR "maternal psychological distress") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(mother* OR women*))

See Subject headings for information on including these database specific terms to your search terms.

Systematic reviewers usually use several databases to search for literature. This ensures that the searching is comprehensive and biases are minimised.

Use both subject-specific and multidisciplinary databases to find resources relevant to your research question:

- Subject-specific databases: in-depth coverage of literature specific to a research field.

- Multi-disciplinary databases: literature from many research fields - help you find resources from disciplines you may not have considered.

Check for databases in your subject area via the Databases tab > Find by subject on the library homepage .

Find the key databases that are often used for systematic reviews in this guide.

Test searches to determine database usefulness. You can consult your Liaison Librarians to finalise the list of databases for your review.

Recommendations:

For all systematic reviews we recommend using Scopus , a high-quality, multidisciplinary database:

- Scopus is an abstract and citation database with links to full text on publisher websites or in other databases.

- Scopus indexes a curated collection of high quality journals along with books and conference proceedings.

- Research outputs are across a range of fields - science, technology, medicine, social science, arts and humanities.

For systematic reviews within the health/biomedical field, we recommend including Medline as one of the databases for your review:

MEDLINE (via Ebsco, via Ovid, via PubMed)

- Medline is the National Library of Medicine’s (NLM) article citation database.

- Medline is hosted individually on a variety of platforms (EBSCO, OVID) and comprises the majority of PubMed.

- Articles in Medline are indexed using MeSH headings. See Subject headings for more information on MeSH.

Note: PubMed contains all of Medline and additional citations, e.g. books, manuscripts, citations that predate Medline.

To ensure your search is comprehensive you may need to search beyond academic databases when conducting a systematic review, particularly to find grey literature (literature not published commercially and outside traditional academic sources such as journals).

Google Scholar

Google Scholar contains academic resources across disciplines and sources types. These come from academic publishers, professional societies, online repositories, universities and web sites.

Use Google Scholar

- as an additional tool to locate relevant publications not included in high-level academic databases

- for finding grey literature such as postgraduate theses and conference proceedings

You can limit your search to the type of websites by using site:ac . nz; site:edu

Note that Google Scholar searches are not as replicable or transparent as academic database searches, and may find large numbers of results.

Other sources of grey literature

- Grey literature checklist (health related grey literature)

- OpenGrey

- Public health Ontario guide to appraising grey literature

- Institutional Repository for Information Sharing (IRIS)

- Google search: use it for finding government reports, policies, theses, etc. You can limit your search to a particular type of websites by including site : govt.nz, site: . gov, site: . ac . nz, site: . edu, in your search

Watch our Finding grey literature video (3.49 mins) online.

- << Previous: Planning

- Next: Search techniques >>

- Last Updated: Mar 13, 2024 9:39 AM

- URL: https://aut.ac.nz.libguides.com/systematic_reviews

Conducting a Literature Review

- Getting Started

- Developing a Question

- Searching the Literature

- Identifying Peer-Reviewed Resources

- Managing Results

- Analyzing the Literature

- Writing the Review

Need Help? Ask Your librarian!

Search Strategies

- Boolean Operators

Once you have identified the key concepts of your research question (see "Developing a Question"), you can use those concepts to develop keywords for your search strategy. The following tips and techniques will help you design a precise and relevant search strategy.

Keywords are any words you might use to search the record of an article, book, or other material in library databases. The database searches through the metadata (such as title, authors, publication, abstract, etc.) to find resources that contain the word you searched, and may also search through the full text of the material.

Keywords are most successful when you're searching for the words that the authors use to describe the research topic, as most databases will search for those specific words within the record of the article. To increase your chance of returning relevant results, consider all of the words that might be used to describe the research you're trying to find, and try some of these out in sample searches to determine which words return the best results.

Search Tips - Keywords

- Search for singular and plural terms together: (physician OR physicians)

- Search for both the American and British spelling of words: (behavior OR behaviour)

- Search for synonyms of terms together: (teenager OR adolescent)

- Search for phrases inside of quotation marks: ("young adult")

Use Boolean operators to combine keywords for more precise search results.

AND - If the term must be included in your search:

influenza AND vaccine

OR - If terms are interchangeable, i.e. synonyms. Place OR'd terms within parentheses:

(influenza OR flu) AND vaccine

NOT - If a term should not be included in your search. This Boolean operator is rarely necessary for literature reviews.

(influenza OR flu) AND vaccine NOT H1N1

Note how we've used parentheses in the examples above. Search strings like these are similar to mathematical equations, where you perform the actions within the parentheses before proceeding from left to right to run the search. For example, using the search [(influenza OR flu) AND vaccine] will find results that have a term relating to influenza/flu, as well as the term vaccine.

If we moved the parentheses, it would be a very different search. [influenza OR (flu AND vaccine)] will provide results that use the term influenza, as well as results that use both the terms flu and vaccine. This means you would get results having to do with influenza but perhaps nothing to do with vaccination.

Here are a few examples of how this search would be different depending on the arrangement of booleans and keywords. The area highlighted in pink represents the search results that would be returned with this search.

Truncation allows you to quickly include all variations of a word in your search. Use the root of the keyword and add an asterisk (*). For example:

nurs* = nurse, nurses, nursing, nursery

IMPORTANT: Notice that "nursery" is also retrieved in the above search. Truncation will save you from having to include a large number of synonyms, but it will also add a certain number of irrelevant results. You can limit this effect by using the NOT Boolean operator, i.e. NOT nursery.

Wild cards allow you to replace a letter in a keyword to retrieve all variations of the spelling. For example:

p?ediatric = pediatric, paediatric

Free-Text vs. Thesaurus Searching

While you can search any word as a keyword, databases also contain an official list of the terms they use to describe the subject of each article, called Subject Headings. You can look up Subject Headings in the thesaurus of the database, using the thesaurus's search box to pull up the recommended Subject Heading for a given keyword. When searching specifically for Subject Headings, the database will only search the Subject Headings field within the record of each article (ie, not the title, abstract, etc.). This is a much more targeted method of searching, and is an excellent addition to your search strategy.

A strong search strategy will use both free-text (keyword) searching and thesaurus searching, to ensure that all relevant articles have been retrieved by the search. The lists below outline the strengths and weaknesses of both types of search strategies.

Free-Text Searching

- Natural language words describing your topic

- More flexible search strategy - can use any term in any combination

- Database looks for keywords anywhere in the record - not necessarily connected together

- May yield too many or too few results

- May yield many irrelevant results

Thesaurus Searching

- Pre-defined "controlled vocabulary" words used to describe the content of each item in a database

- Less flexible search strategy - need to know the exact controlled vocabulary term

- Database looks for subjects only in the subject heading or descriptor field, where the most relevant words appear

- If too many results, you can use subheadings to focus on one aspect of a broader topic

- Results are usually very relevant to the topic

MIT Libraries. Database Search Tips: Keywords vs. Subjects. https://libguides.mit.edu/c.php?g=175963&p=1160804

Each database has their own thesaurus. You will need to adapt your search strategy for each database to take advantage of their unique thesaurus.

PubMed uses MeSH terms (Medical Subject Headings). You can learn more about finding and using MeSH terms here:

- The Basics of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) in MEDLINE/PubMed: A Tutorial

CINAHL uses CINAHL Headings. You can learn more about finding and use these terms here:

- Using CINAHL/MeSH Headings

In other databases, look for a link with the terms "headings", "subject headings", or "thesaurus" to find the appropriate thesaurus terms for your search.

Citation Searching

Citation searching is a search strategy that allows you to search either forward or backwards time through the literature based on an identified relevant article:

You can search forward in time by using databases that allow you to search for other articles that have cited the identified relevant article. (Web of Science and Google Scholar can do this automatically.)

- Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics)

- Google Scholar

You can search backward in time by reviewing the reference list of the identified relevant article for additional article citations.

For more information about how to perform citation searches, check out this guide from the University of Toledo Libraries:

- How To: Cited Reference Searches in Web of Science Guide from the University of Toledo

Retrieving Materials

Select a database.

When searching for articles, it is best to use an appropriate subject database rather than the SearchIT catalog. Be sure to select your database from the Spokane Academic Library homepage to ensure that you will have access to full-text articles.

"Find It @ WSU" Button in PubMed

When you have found an article that you would like to read in its entirety, look for the "Find It @ WSU" Button. This button will take you to the article entry in the SearchIT catalog.

Here's what that looks like in PubMed.

"Find It @ WSU" Button in CINAHL

"Find It @ WSU" Button in PsycINFO

Accessing the Full-Text Article

After selecting the "Find It @ WSU" Button, you will be taken to the article entry in SearchIT. Select the link under the Access Options box to be directed to the full-text article.

If an article is not available in the WSU Libraries collection, you can request the article through interlibrary loan by selecting the link under "Access Options".

See the Using Interlibrary Loan section for more information.

- << Previous: Developing a Question

- Next: Identifying Peer-Reviewed Resources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 11:04 AM

- URL: https://libguides.libraries.wsu.edu/litreview

Systematic Reviews

- Introduction

- Review Process: Step by Step

- 1. Planning a Review

- 2. Defining Your Question & Criteria

- 3. Standards & Protocols

Designing Your Search Strategy

Search strategy checklists, pre-search tips, search strategies: filters & hedges, search terms, search strategies: and/or, phrase searching & truncation.

- 5. Locating Published Research

- 6. Locating Grey Literature

- 7. Managing & Documenting Results

- 8. Selecting & Appraising Studies

- 9. Extracting Data

- 10. Writing a Systematic Review

- Tools & Software

- Guides & Tutorials

- Accessing Resources

- Research Assistance

A well designed search strategy is essential to the success of your systematic review. Your strategy should be specific, unbiased, reproducible and will typically include subject headings along with a range of keywords/phrases for each of your concepts.

Your searches should be designed to capture as many studies as possible that meet your criteria.

Chapter 4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions provides detailed guidance for searching and study selection; see Supplement 3.8 Adapting search strategies across databases / sources for translating your search across databases.

Systematic Reviews: Constructing a Search Strategy and Searching for Evidence from the Joanna Briggs Institute provides step-by-step guidance using PubMed as an example database.

General Steps:

- Locate previous/ relevant searches

- Identify your databases

- Develop your search terms and design search

- Evaluate and modify your search

- Document your search ( PRISMA-S Checklist)

- Translate your search for other databases

- Step by Step Systematic Review Search Checklist from MD Anderson Center Library

- PRESS Peer Review Checklist for Search Strategies

Conduct a preliminary set of scoping searches in various databases to test out your search terms (keywords and subject headings) and locate additional terms for your concepts.

Try building a "gold set" of relevant references to help you identify search terms. Sources for this gold set may include:

- Recommended key papers

- Papers by known authors in the field

- Results of preliminary searches from key databases such

- Reviewing references and "cited by" articles lists for key papers

- Articles that have been published in authoritative journals

Hedges/ Filters

- PubMed Special Queries

Hedges are search strings created by experts to help you retrieve specific types of studies or topics; a hedge will filter your results by adding specific search terms, or specific combinations of search terms, to your search.

Hedges can be good starting points but you may need to modify the search string to fit your research. Resources for hedges:

- University of Texas, School of Public Health (study type)

- McMaster University Health Information Research Unit

- The InterTASC Information Specialists' Sub-Group Search Filter Resource

- Pubmed Search Strategies blog

- PubMed Special Queries Topic-Specific PubMed Queries; includes keyword and search strategy examples.

Example: Health Disparities & Minority Health Search Strategies

- Subject Headings

- Keywords Vs. Subject Headings

- Locating Subject Headings

- Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Keyword & Subject Headings Logic Grid

You can use your PICOTS concepts as preliminary search terms. The important terms in this question:

In adults , is screening for depression and feedback of results to providers more effective than no screening and feedback in improving outcomes of major depression in primary care settings?

...might include:

Major depression

Primary Care

(From Lackey, M. (2013). Systematic reviews: Searching the literature [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://guides.lib.unc.edu/ld.php?content_id=258919 )

Your search will include both keywords and subject headings. Controlled vocabulary systems, such as the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) or Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) , use pre-set terms that are used to tag resources on similar subjects. See boxes below for more information on finding and using subject terms.

Not all databases will have subject heading searching and for those that do, the subject heading categories may differ between databases. This is because databases classify articles using different criteria.

Using the keywords from our example, here are some MeSH terms for:

Adults : Adult (A person having attained full growth or maturity. Adults are of 19 through 44 years of age. For a person between 19 and 24 years of age, YOUNG ADULT is available.)

Screening : Mass Screening (Organized periodic procedures performed on large groups of people for the purpose of detecting disease.)

Major depression : Depressive Disorder, Major (Marked depression appearing in the involution period and characterized by hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, and agitation.)

Here is a LCSH subject term for:

Depression : Depression, mental (Dejection ; Depression, Unipolar ; Depressive disorder ; Depressive psychoses ; Melancholia ; Mental depression ; Unipolar depression)

- Most EBSCO databases have a tool to help you discover subject terms . See Academic Search Complete > Subject Terms and Academic Search Complete > Subject Terms: Thesaurus

- Most ProQuest databases have a tool to help you discover subject terms: See PsycInfo > Thesaurus

- When you find a useful article, look at the article's Subject Headings (or Subject or Subject Terms) , and record them as possible terms to use in a subject term search.

Here is an example of the subject terms listed for a systematic review found in PsycINFO, " Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force " (2016).

MeSH are standardized terms that describe the main concepts of PubMed/MedLine articles. Searching with MeSH can increase the precision of your search by providing a consistent way to retrieve articles that may use different terminology or spelling variations.

Note: new articles will not have MeSH terms; the indexing process may take up to a few weeks for newly ingested articles.

Use the MeSH database to locate and build a search using MeSH.

To search the MeSH database:

- Search for 1 concept at a time.

- If you do not see a relevant MeSH in the results, search again with a synonym or related term.

- Click on the MeSH term to view to the complete record, subheadings, broader and narrower terms.

Build a search from the results list or from the MeSH term record to specify subheadings.

- Select the box next to the MeSH term or subheadings that you wish to search and click Add to Search Builder.

- You may need to switch AND to OR , depending on how you would like to combine terms.

- Repeat the above steps to add additional MeSH terms. When your search is ready, click Search PubMed.

Logic Grid with Keywords and Index Terms or Subject Headings from Systematic Reviews: Constructing a Search Strategy and Searching for Evidence.

Bhuiyan, M. U., Stiboy, E., Hassan, M. Z., Chan, M., Islam, M. S., Haider, N., Jaffe, A., & Homaira, N. (2021). Epidemiology of COVID-19 infection in young children under five years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine , 39 (4), 667–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.11.078

- Boolean Logic: AND, OR, NOT

- Phrase Searching " "

- Truncation *

- Proximity Searching

AND, OR, NOT

Join together search terms in a logical manner.

AND - narrows searches, used to join dissimilar terms OR - broadens searches, used to join similar terms

NOT - removes results containing specified keywords

#1 "major depression" AND "primary care"

#2 screen* OR feedback

#3 (screen* OR feedback)

AND “major depression”

AND “primary care”

"major depression" NOT suicide

" " To search for specific phrases, enclose them in quotation marks . The database will search for those words together in that order.

“ primary care ”

“ major depression ”

Truncate a word in order to search for different forms of the same word. Many databases use the asterisk * as the truncation symbol.

Add the truncation symbol to the word screen * to search for screen, screens, screening, etc.

You do have to be careful with truncation. If you add the truncation symbol to the word minor* , the database will search for minor, minors, minority, minorities, etc.

Not all databases support proximity searching. You can use these strategies in ProQuest databases such as Sociological Abstracts .

pre/# is used to search for terms in proximity to each other in a specific order; # is replaced with the number of words permitted between the search terms.

Sample Search: parent* pre/2 educational (within 2 words & in order )

- This would retrieve articles with no more than two words between parent* and educational (in this order) e.g. " Parent practices and educational achievement" OR " Parents on Educational Attainment" OR " Parental Values, Educational Attainment" etc.

w/# is used to search for terms in proximity to each other in any order ; # is replaced with the number of words permitted between the search terms.

Sample Search: parent* w/3 educational (within 3 words & in any order )

- This would retrieve articles with no more than three words between parent* and educational (in any order) e.g. "Educational practices of parents" OR "Parents value motivation and education" OR "Educational attainments of Latino parents"

- << Previous: 3. Standards & Protocols

- Next: 5. Locating Published Research >>

- Last Updated: Feb 26, 2024 2:04 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ucmerced.edu/systematic-reviews

Help us improve our Library guides with this 5 minute survey . We appreciate your feedback!

- UOW Library

- Key guides for students

Literature Review

How to search effectively.

- Find examples of literature reviews

- How to write a literature review

- Grey literature

The Literature searching interactive tutorial includes self-paced, guided activities to assist you in developing effective search skills..

1. Identify search words

Analyse your research topic or question.

- What are the main ideas?

- What concepts or theories have you already covered?

- Write down your main ideas, synonyms, related words and phrases.

- If you're looking for specific types of research, use these suggested terms: qualitative, quantitative, methodology, review, survey, test, trend (and more).

- Be aware of UK and US spelling variations. E.g. organisation OR organization, ageing OR aging.

- Interactive Keyword Builder

- Identifying effective keywords

2. Connect your search words

Find results with one or more search words.

Use OR between words that mean the same thing.

E.g. adolescent OR teenager

This search will find results with either (or both) of the search words.

Find results with two search words

Use AND between words which represent the main ideas in the question.

E.g. adolescent AND “physical activity”

This will find results with both of the search words.

Exclude search words

Use NOT to exclude words that you don’t want in your search results.

E.g. (adolescent OR teenager) NOT “young adult”

3. Use search tricks

Search for different word endings.

Truncation *

The asterisk symbol * will help you search for different word endings.

E.g. teen* will find results with the words: teen, teens, teenager, teenagers

Specific truncation symbols will vary. Check the 'Help' section of the database you are searching.

Search for common phrases

Phrase searching “...........”

Double quotation marks help you search for common phrases and make your results more relevant.

E.g. “physical activity” will find results with the words physical activity together as a phrase.

Search for spelling variations within related terms

Wildcards ?

Wildcard symbols allow you to search for spelling variations within the same or related terms.

E.g. wom?n will find results with women OR woman

Specific wild card symbols will vary. Check the 'Help' section of the database you are searching.

Search terms within specific ranges of each other

Proximity w/#

Proximity searching allows you to specify where your search terms will appear in relation to each other.

E.g. pain w/10 morphine will search for pain within ten words of morphine

Specific proximity symbols will vary. Check the 'Help' section of the database you are searching.

4. Improve your search results

All library databases are different and you can't always search and refine in the same way. Try to be consistent when transferring your search in the library databases you have chosen.

Narrow and refine your search results by:

- year of publication or date range (for recent or historical research)

- document or source type (e.g. article, review or book)

- subject or keyword (for relevance). Try repeating your search using the 'subject' headings or 'keywords' field to focus your search

- searching in particular fields, i.e. citation and abstract. Explore the available dropdown menus to change the fields to be searched.

When searching, remember to:

Adapt your search and keep trying.

Searching for information is a process and you won't always get it right the first time. Improve your results by changing your search and trying again until you're happy with what you have found.

Keep track of your searches

Keeping track of searches saves time as you can rerun them, store references, and set up regular alerts for new research relevant to your topic.

Most library databases allow you to register with a personal account. Look for a 'log in', 'sign in' or 'register' button to get started.

- Literature review search tracker (Excel spreadsheet)

Manage your references

There are free and subscription reference management programs available on the web or to download on your computer.

- EndNote - The University has a license for EndNote. It is available for all students and staff, although is recommended for postgraduates and academic staff.

- Zotero - Free software recommended for undergraduate students.

- Previous: How to write a literature review

- Next: Where to search when doing a literature review

- Last Updated: Mar 13, 2024 8:37 AM

- URL: https://uow.libguides.com/literaturereview

Insert research help text here

LIBRARY RESOURCES

Library homepage

Library SEARCH

A-Z Databases

STUDY SUPPORT

Academic Skills Centre

Referencing and citing

Digital Skills Hub

MORE UOW SERVICES

UOW homepage

Student support and wellbeing

IT Services

On the lands that we study, we walk, and we live, we acknowledge and respect the traditional custodians and cultural knowledge holders of these lands.

Copyright & disclaimer | Privacy & cookie usage

University Libraries University of Nevada, Reno

- Skill Guides

- Subject Guides

Systematic, Scoping, and Other Literature Reviews: Searching

- Project Planning

Searching the Literature

Systematic and other major reviews involve a comprehensive search of the literature to ensure all studies that meet the predetermined criteria are identified. Typically key subject databases are searched first, after which the team might turn to less conventional search venues and explore what is known as grey literature - essentially any research that is shared outside of traditional publishing and distribution venues. Examples of grey literature include white papers, working papers, reports, government documents, and policy documents. And after screening the results found through these means, engaging in citation searching is recommended.

Review teams should develop search strategies that incorporate a mix of keywords and controlled vocabulary specific to the databases they're searching. Controlled vocabulary like the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) used by PubMed and MEDLINE are standardized words and phrases that help enable the organization and retrieval of information in databases and other online venues.

Each research question is different, so the terms you'' use and the number and types of databases you'll search - as well as other online publication venues - will vary. Some standards and guidelines specify that certain databases (e.g., MEDLINE, EMBASE) should be searched regardless. Your subject librarian can help you select appropriate databases to search and develop search strings for each of those databases.

Commonly Searched Databases

Since systematic reviews began in the health sciences, searching PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials is standard practice. These databases are listed below.

However, if you are conducting a review of the literature in another discipline, you will need to search the databases specific to that discipline. To begin, consult the library's complete list of databases or speak with your librarian.

- PubMed PubMed is the National Library of Medicine's interface for MEDLINE, and also includes in-process and pre-1966 citations and other resources outside of MEDLINE. While basic PubMed is free to all Internet users, this link adds "Find it" buttons to individual citations that connect to the University of Nevada, Reno Libraries' journal subscriptions and document delivery services for full-text options.

- MEDLINE via Ovid Updated daily, MEDLINE on the Ovid platform offers searchers seamless and up-to-the-minute access to over 23 million of the latest bibliographic citations and author abstracts from more than 5,600 biomedicine and life sciences journals in nearly 40 languages (60 languages for older journals). English abstracts are included in more than 80% of the records. Coverage dating back to 1946.

- Embase An Elsevier database that covers the same subjects as PubMed/MEDLINE, with an additional focus on drugs and pharmacology, medical devices, clinical medicine, and basic science relevant to clinical medicine. 1947 - present (selectively back to 1902).

- Cochrane Library The Cochrane Library contains the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Cochrane Clinical Answers that offer different types of high-quality, independent evidence to inform healthcare decision-making.

Search Development Tools

Several online tools exist to help you identify controlled vocabulary, develop better search strings, and "translate" a search string developed for one database into one that works in another database. The tools listed below can assist you with one or more of these tasks. However, they are primarily aimed at and designed for teams and databases working in the health sciences.

- Yale MeSH Analyzer

- PubMed PubReMiner

- MeSH on Demand

Grey Literature Search Tools

As noted above, searching the grey literature is also a key component of a good systematic review strategy. However, where to to search for such sources can vary a lot depending on the topic or field. Many researchers make use of the resources listed below. Please consult your librarian for more target assistance.

- Google Advanced Search

- OpenGrey "The System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe used to give open access to 700.000 bibliographical references of grey literature (paper) produced in Europe and allowed to export records and locate the documents."

- govinfo "govinfo provides free public access to official publications from all three branches of the Federal Government."

Citation Searching

Citation searching is a method of searching the literature using citations rather than going to a database and conducting a search using keywords. It can help you better understand the scholarly landscape within your discipline and determine how your own work fits within that landscape. There are two types of citation searching: backward searching and forward searching.

Backward Citation Searching

When reading a work that’s very relevant to your research, you may want to examine the reference list closely to see which previously published works influenced the author(s). If you tracked down those cited works, you’d be engaging in what is known as backward citation searching.

Forward Citation Searching

Conversely, you may want to determine whether and by whom a given work has been cited after its publication – essentially, you’re wanting to know if other, newer works have included it in their reference lists. This is called forward citation searching.

The resources listed below can help you with citation searching.

- Web of Science This collection contains over 21,000+ journals from 1900-present and includes: Science Citation Index , Social Sciences Citation Index , Arts and Humanities Citation Index and others. Search by subject, author, or cited reference. An excellent current awareness and bibliography-building tool.

- citationchaser

- ResearchRabbit

- << Previous: Project Planning

- Next: Screening >>

Making Literature Reviews Work: A Multidisciplinary Guide to Systematic Approaches pp 145–200 Cite as

Search Strategies for [Systematic] Literature Reviews

- Rob Dekkers 4 ,

- Lindsey Carey 5 &

- Peter Langhorne 6

- First Online: 11 August 2022

1833 Accesses

3 Citations

After setting review questions as discussed in the previous chapter, the search for relevant publications is the next step of a literature review.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

JEL is the abbreviation of the ‘Journal of Economics Literature’, published by the American Economic Association, which launched this coding system.

Actually, Schlosser et al. ( 2006 , p. 571 ff.) call it ‘traditional pearl growing.’ The term ‘classical’ pearl growing has been adopted to ensure consistency throughout the book.

The wording ‘topical bibliography’ by Schlosser et al. ( 2006 , p. 574) has been replaced with ‘topical survey’ in order to connect better to the terminology in this book.

Webster and Watson ( 2002 , p. xvi) call it forward searching and backward searching rather than snowballing. See Table 5.3 for the nomenclature used in the book for search strategies.

Aguillo IF (2012) Is Google Scholar useful for bibliometrics? A webometric analysis. Scientometrics 91(2):343–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0582-8

Bardia A, Wahner-Roedler DL, Erwin PL, Sood A (2006) Search strategies for retrieving complementary and alternative medicine clinical trials in oncology. Integr Cancer Ther 5(3):202–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735406292146

Bates MJ (1989) The design of browsing and berrypicking techniques for the online search interface. Online Rev 13(5):407–424

Google Scholar

Bates MJ (2007) What is browsing—really? A model drawing from behavioural science research. Inform Res 20(4). http://informationr.net/ir/12-4/paper330.html

Benzies KM, Premji S, Hayden KA, Serrett K (2006) State-of-the-evidence reviews: advantages and challenges of including grey literature. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 3(2):55–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2006.00051.x

Bernardo M, Simon A, Tarí JJ, Molina-Azorín JF (2015) Benefits of management systems integration: a literature review. J Clean Prod 94:260–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.01.075

Beynon R, Leeflang MM, McDonald S, Eisinga A, Mitchell RL, Whiting P, Glanville JM (2013) Search strategies to identify diagnostic accuracy studies in MEDLINE and EMBASE. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (9). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.MR000022.pub3

Bolton JE (1971) Small firms—report of the committee of inquiry on small firms (4811). London

Boluyt N, Tjosvold L, Lefebvre C, Klassen TP, Offringa M (2008) Usefulness of systematic review search strategies in finding child health systematic reviews in MEDLINE. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 162(2):111–116. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.40

Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, Gerhardus A, Wahlster P, van der Wilt GJ, Rehfuess E (2018) Structured methodology review identified seven (RETREAT) criteria for selecting qualitative evidence synthesis approaches. J Clinic Epidemiol 99:41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.03.003

Chesbrough H (2012) Open innovation: where we’ve been and where we’re going. Res Technol Manag 55(4):20–27. https://doi.org/10.5437/08956308X5504085

Chesbrough HW (2003) Open innovation: the new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

Conn VS, Valentine JC, Cooper HM, Rantz MJ (2003) Grey literature in meta-analyses. Nurs Res 52(4):256–261

de la Torre Díez I, Cosgaya HM, Garcia-Zapirain B, López-Coronado M (2016) Big data in health: a literature review from the year 2005. J Med Syst 40(9):209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-016-0565-7

Dekkers R, Hicks C (2019) How many cases do you need for studies into operations management? Guidance based on saturation. In: Paper presented at the 26th EurOMA conference, Helsinki

Dekkers R, Koukou MI, Mitchell S, Sinclair S (2019) Engaging with open innovation: a Scottish perspective on its opportunities, challenges and risks. J Innov Econ Manag 28(1):193–226. https://doi.org/10.3917/jie.028.0187

Dieste O, Grimán A, Juristo N (2009) Developing search strategies for detecting relevant experiments. Empir Softw Eng 14(5):513–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-008-9091-7

Eady AM, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB (2008) PsycINFO search strategies identified methodologically sound therapy studies and review articles for use by clinicians and researchers. J Clin Epidemiol 61(1):34–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.09.016

Egger M, Zellweger-Zähner T, Schneider M, Junker C, Lengeler C, Antes G (1997) Language bias in randomised controlled trials published in English and German. The Lancet 350(9074):326–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02419-7

Eisenhardt KM (1989) Agency theory: an assessment and review. Acad Manag Rev 14(1):57–74. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1989.4279003

Finfgeld-Connett D, Johnson ED (2013) Literature search strategies for conducting knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews. J Adv Nurs 69(1):194–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06037.x

Frederick JT, Steinman LE, Prohaska T, Satariano WA, Bruce M, Bryant L, Snowden M (2007) Community-based treatment of late life depression: an expert panel-informed literature review. Am J Prev Med 33(3):222–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.035

Glanville J, Kaunelis D, Mensinkai S (2009) How well do search filters perform in identifying economic evaluations in MEDLINE and EMBASE. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 25(4):522–529. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462309990523

Godin K, Stapleton J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hanning RM, Leatherdale ST (2015) Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: a case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Syst Rev 4(1):138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0

Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A (2006) Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med 5(3):101–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6

Greenhalgh T, Peacock R (2005) Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ 331(7524):1064–1065. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68

Grégoire G, Derderian F, le Lorier J (1995) Selecting the language of the publications included in a meta-analysis: is there a Tower of Babel bias? J Clin Epidemiol 48(1):159–163

Gross T, Taylor AG, Joudrey DN (2015) Still a lot to lose: the role of controlled vocabulary in keyword searching. Catalog Classific Q 53(1):1–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2014.917447

Grosso G, Godos J, Galvano F, Giovannucci EL (2017) Coffee, caffeine, and health outcomes: an umbrella review. Annu Rev Nutr 37(1):131–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064941

Gusenbauer M, Haddaway NR (2020) Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res Synthesis Methods 11(2):181–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1378

Haddaway NR, Bayliss HR (2015) Shades of grey: two forms of grey literature important for reviews in conservation. Biol Cons 191:827–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.08.018

Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, Kirk S (2015) The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS One 10(9):e0138237. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

Harari MB, Parola HR, Hartwell CJ, Riegelman A (2020) Literature searches in systematic reviews and meta-analyses: a review, evaluation, and recommendations. J Vocat Behav 118:103377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103377

Harzing A-WK, van der Wal R (2008) Google Scholar as a new source for citation analysis. Ethics Sci Environ Politics 8(1):61–73. https://doi.org/10.3354/esep00076

Hausner E, Guddat C, Hermanns T, Lampert U, Waffenschmidt S (2016) Prospective comparison of search strategies for systematic reviews: an objective approach yielded higher sensitivity than a conceptual one. J Clin Epidemiol 77:118–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.05.002

Hausner E, Waffenschmidt S, Kaiser T, Simon M (2012) Routine development of objectively derived search strategies. Syst Rev 1(1):19. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-19

Havill NL, Leeman J, Shaw-Kokot J, Knafl K, Crandell J, Sandelowski M (2014) Managing large-volume literature searches in research synthesis studies. Nurs Outlook 62(2):112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2013.11.002

Hildebrand AM, Iansavichus AV, Haynes RB, Wilczynski NL, Mehta RL, Parikh CR, Garg AX (2014) High-performance information search filters for acute kidney injury content in PubMed, Ovid Medline and Embase. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29(4):823–832. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gft531

Hinckeldeyn J, Dekkers R, Kreutzfeldt J (2015) Productivity of product design and engineering processes—unexplored territory for production management techniques? Int J Oper Prod Manag 35(4):458–486. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-03-2013-0101

Hopewell S, Clarke M, Lefebvre C, Scherer R (2007) Handsearching versus electronic searching to identify reports of randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):MR000001. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.mr000001.pub2

Isckia T, Lescop D (2011) Une analyse critique des fondements de l’innovation ouverte. Rev Fr Gest 210(1):87–98

Jackson JL, Kuriyama A (2019) How often do systematic reviews exclude articles not published in English? J Gen Intern Med 34(8):1388–1389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04976-x

Jennex ME (2015) Literature reviews and the review process: an editor-in-chief’s perspective. Commun Assoc Inf Syst 36:139–146. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.03608

Jensen MC, Meckling WH (1976) Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ Econ 3(4):305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

Jüni P, Holenstein F, Sterne J, Bartlett C, Egger M (2002) Direction and impact of language bias in meta-analyses of controlled trials: empirical study. Int J Epidemiol 31(1):115–123. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/31.1.115

Kennedy MM (2007) Defining a literature. Educ Res 36(3):139. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x07299197

Koffel JB (2015) Use of recommended search strategies in systematic reviews and the impact of librarian involvement: a cross-sectional survey of recent authors. PLoS One 10(5):e0125931. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125931

Koffel JB, Rethlefsen ML (2016) Reproducibility of search strategies is poor in systematic reviews published in high-impact pediatrics, cardiology and surgery journals: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 11(9):e0163309. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163309

Lawal AK, Rotter T, Kinsman L, Sari N, Harrison L, Jeffery C, Flynn R (2014) Lean management in health care: definition, concepts, methodology and effects reported (systematic review protocol). Syst Rev 3(1):103. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-103

Levay P, Ainsworth N, Kettle R, Morgan A (2016) Identifying evidence for public health guidance: a comparison of citation searching with Web of Science and Google Scholar. Res Synthesis Methods 7(1):34–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1158

Li L, Smith HE, Atun R, Tudor Car L (2019) Search strategies to identify observational studies in MEDLINE and Embase. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.MR000041.pub2

Linton JD, Thongpapanl NT (2004) Ranking the technology innovation management journals. J Prod Innov Manag 21(2):123–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0737-6782.2004.00062.x

Lokker C, McKibbon KA, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Straus SE (2010) Finding knowledge translation articles in CINAHL. Studies Health Technol Inform 160(2):1179–1183

Lu Z (2011) PubMed and beyond: a survey of web tools for searching biomedical literature. Database. https://doi.org/10.1093/database/baq036

MacSuga-Gage AS, Simonsen B (2015) Examining the effects of teacher—directed opportunities to respond on student outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Educ Treat Child 38(2):211–239. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2015.0009

Mahood Q, Van Eerd D, Irvin E (2014) Searching for grey literature for systematic reviews: challenges and benefits. Res Synthesis Methods 5(3):221–234. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1106

Marangunić N, Granić A (2015) Technology acceptance model: a literature review from 1986 to 2013. Univ Access Inf Soc 14(1):81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-014-0348-1

Mc Elhinney H, Taylor B, Sinclair M, Holman MR (2016) Sensitivity and specificity of electronic databases: the example of searching for evidence on child protection issues related to pregnant women. Evid Based Midwifery 14(1):29–34

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C (2016) PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol 75:40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021

McManus RJ, Wilson S, Delaney BC, Fitzmaurice DA, Hyde CJ, Tobias S, Hobbs FDR (1998) Review of the usefulness of contacting other experts when conducting a literature search for systematic reviews. Br Med J 317(7172):1562–1563 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7172.1562

Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi (2014) PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res 14(1):579. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0

Mitnick BM (1973) Fiduciary rationality and public policy: the theory of agency and some consequences. In: Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American political science association, New Orleans, LA

Morrison A, Polisena J, Husereau D, Moulton K, Clark M, Fiander M, Rabb D (2012) The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 28(2):138–144. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462312000086

Neuhaus C, Daniel HD (2008) Data sources for performing citation analysis: an overview. J Document 64(2):193–210. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410810858010

O’Mara-Eves A, Thomas J, McNaught J, Miwa M, Ananiadou S (2015) Using text mining for study identification in systematic reviews: a systematic review of current approaches. Syst Rev 4(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-5

Ogilvie D, Foster CE, Rothnie H, Cavill N, Hamilton V, Fitzsimons CF, Mutrie N (2007) Interventions to promote walking: systematic review. BMJ 334(7605):1204. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39198.722720.BE

Onetti A (2019) Turning open innovation into practice: trends in European corporates. J Bus Strateg 42(1):51–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBS-07-2019-0138

Papaioannou D, Sutton A, Carroll C, Booth A, Wong R (2010) Literature searching for social science systematic reviews: consideration of a range of search techniques. Health Info Libr J 27(2):114–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00863.x

Pappas C, Williams I (2011) Grey literature: its emerging importance. J Hosp Librariansh 11(3):228–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/15323269.2011.587100

Pearson M, Moxham T, Ashton K (2011) Effectiveness of search strategies for qualitative research about barriers and facilitators of program delivery. Eval Health Prof 34(3):297–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278710388029

Piggott-McKellar AE, McNamara KE, Nunn PD, Watson JEM (2019) What are the barriers to successful community-based climate change adaptation? A review of grey literature. Local Environ 24(4):374–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2019.1580688

Piller F, West J (2014) Firms, users, and innovations: an interactive model of coupled innovation. In: Chesbrough HW, Vanhaverbeke W, West J (eds) New frontiers in open innovation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 29–49

Poole R, Kennedy OJ, Roderick P, Fallowfield JA, Hayes PC, Parkes J (2017) Coffee consumption and health: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. BMJ 359:j5024. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5024

Priem RL, Butler JE (2001) Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Acad Manag Rev 26(1):22–40. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4011928

Relevo R (2012) Effective search strategies for systematic reviews of medical tests. J Gener Internal Med 27(1):S28–S32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1873-8

Rethlefsen ML, Farrell AM, Osterhaus Trzasko LC, Brigham TJ (2015) Librarian co-authors correlated with higher quality reported search strategies in general internal medicine systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 68(6):617–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.025

Rewhorn S (2018) Writing your successful literature review. J Geogr High Educ 42(1):143–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2017.1337732

Rietjens JA, Bramer WM, Geijteman EC, van der Heide A, Oldenmenger WH (2019) Development and validation of search filters to find articles on palliative care in bibliographic databases. Palliat Med 33(4):470–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216318824275

Rogers M, Bethel A, Abbott R (2018) Locating qualitative studies in dementia on MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO: a comparison of search strategies. Res Synthesis Methods 9(4):579–586. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1280

Rosenstock TS, Lamanna C, Chesterman S, Bell P, Arslan A, Richards M, Zhou W (2016) The scientific basis of climate-smart agriculture: a systematic review protocol. CGIAR, Copenhagen

Ross SA (1973) The economic theory of agency: the principal’s problem. Am Econ Rev 63(2):134–139

Rosumeck S, Wagner M, Wallraf S, Euler U (2020) A validation study revealed differences in design and performance of search filters for qualitative research in PsycINFO and CINAHL. J Clin Epidemiol 128:101–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.09.031

Rowley J, Slack F (2004) Conducting a literature review. Manag Res News 27(6):31–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170410784185

Rudestam K, Newton R (1992) Surviving your dissertation: a comprehensive guide to content and process. Sage, London

Salgado EG, Dekkers R (2018) Lean product development: nothing new under the sun? Int J Manag Rev 20(4):903–933. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12169

Savoie I, Helmer D, Green CJ, Kazanjian A (2003) BEYOND MEDLINE: reducing bias through extended systematic review search. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 19(1):168–178. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462303000163

Schlosser RW, Wendt O, Bhavnani S et al (2006) Use of information-seeking strategies for developing systematic reviews and engaging in evidence-based practice: the application of traditional and comprehensive Pearl growing. A review. Int J Language Commun Disorders 41(5):567–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820600742190

Schryen G (2015) Writing qualitative IS literature reviews—guidelines for synthesis, interpretation, and guidance of research. Commun Assoc Inf Syst 34:286–325. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.03712

Shishank S, Dekkers R (2013) Outsourcing: decision-making methods and criteria during design and engineering. Product Plan Control Manage Oper 24(4–5):318–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2011.648544

Silagy CA, Middleton P, Hopewell S (2002) Publishing protocols of systematic reviews comparing what was done to what was planned. JAMA 287(21):2831–2834. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.21.2831

Soldani J, Tamburri DA, Van Den Heuvel W-J (2018) The pains and gains of microservices: a systematic grey literature review. J Syst Softw 146:215–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.09.082

Stevinson C, Lawlor DA (2004) Searching multiple databases for systematic reviews: added value or diminishing returns? Complement Ther Med 12(4):228–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2004.09.003

Swift JK, Wampold BE (2018) Inclusion and exclusion strategies for conducting meta-analyses. Psychother Res 28(3):356–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1405169

Swift JK, Callahan JL, Cooper M, Parkin SR (2018) The impact of accommodating client preference in psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol 74(11):1924–1937. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22680