- Post Your Writing

- Read & Review

- Search Writer Search Posting

- Posting View

How to Use Paragraphs in Creative Writing

Status: Finished

Article by: SolN

Genre: Other

Writing Tips & Site Help

Regular Reviews : 0

In-Line Reviews : 0

Get Organizer Tools

Content Summary

Send Reading Invitation Mail

Writing membership feature.

This feature is only available to Writing Members . Please upgrade to Writing Membership and you can print this chapter.

Submitted: May 07, 2015

A A A | A A A

Points: 0.64

You have to login to receive points for reviewing this content.

The Use of Paragraphs

Many beginner writers are not sure how to create paragraphs. Often, stories, or chapters of books are one long paragraph, or sometimes several long paragraphs. Readers do not like long paragraphs as long blocks of text are intimidating and make it difficult for a reader to process the text.

What is a paragraph? A paragraph is a collection of sentences that are grouped together around an idea. Often, the first sentence of the paragraph will highlight the idea and then the rest of the sentences will explain and expand upon this. Once the focus shifts to a new idea, then it is time for a new paragraph.

In fiction writing, you should consider starting a new paragraph when any of the following occurs:

- There is a change in perspective.

- There is a shift in location.

- A different character speaks (you should create a new paragraph anytime someone different says something).

- There is a change in focus or thought.

One way to think about a paragraph is like a movie script. Anytime the scene shifts, or the topic changes, or a character speaks, it's a new paragraph.

Paragraphs can be as short as one word or as long as many pages. There is no standard size but if your paragraph has grown beyond a quarter of a page, it may be a sign that you need to split it.

Let's take a look at an example:

Here's an excerpt from Static Mayhem by Edward Aubrey, a published book workshopped on TheNextBigWriter. First, I have removed all of the paragraphs:

He stopped singing. It would have been difficult to continue over the din of his heartbeat, anyway. Aware of safety concerns for the first time in a long while, he focused on the drive. A radio station existed and transmitted. He allowed that thought to develop before he added the logical implication. That station had an operator. Another person had survived. Despite the evidence of his eyes, there must be something left of Springfield, or maybe Hartford, that included a radio tower. The trip across the Vermont border ruled out Hartford as too far away for adequate reception. That left Springfield, which he could reach in about an hour if he turned around and hightailed it. If he decided he wanted to. He was halfway through concocting a search plan when the song ended. "Hi," said the radio. It was a female voice. He turned it up. His hand was trembling. "Hi," he said. His throat felt tight. Moisture nagged at the outer edges of his eyes. "You're still listening to Claudia. That was ‘Here Comes the Sun' by the Beatles. I'd like to take a moment to repeat my message for anyone listening who hasn't heard it yet. This is an open invitation for any survivors to meet me here in Chicago." Harrison missed the next bit, which was drowned out by the scream of his tires against the pavement and his own screams. The car started to spin. It almost started to roll when its momentum ran out. It stood balanced on the two driver's side wheels for what must have been far shorter time than it seemed before it flopped back down onto all four wheels with an unceremonious thud. "… further instructions. I'll be broadcasting until midnight, Eastern Daylight Time, for those of you still keeping track. Remember, come to Chicago. Tell your friends." Harrison identified the initial chords of a Fleetwood Mac song whose title he could not recall as he attempted to refocus himself. His reflex to stomp on the brakes did not feel productive. "Chicago," he said, just to hear it out loud, "is a thousand miles away."

It's pretty difficult to read, isn't it? Now, let's put the paragraphs in:

He stopped singing. It would have been difficult to continue over the din of his heartbeat, anyway. Aware of safety concerns for the first time in a long while, he focused on the drive. A radio station existed and transmitted. He allowed that thought to develop before he added the logical implication. That station had an operator.

Another person had survived.

Despite the evidence of his eyes, there must be something left of Springfield, or maybe Hartford, that included a radio tower. The trip across the Vermont border ruled out Hartford as too far away for adequate reception. That left Springfield, which he could reach in about an hour if he turned around and hightailed it. If he decided he wanted to. He was halfway through concocting a search plan when the song ended.

"Hi," said the radio. It was a female voice.

He turned it up. His hand was trembling. "Hi," he said. His throat felt tight. Moisture nagged at the outer edges of his eyes.

"You're still listening to Claudia. That was ‘Here Comes the Sun' by the Beatles. I'd like to take a moment to repeat my message for anyone listening who hasn't heard it yet. This is an open invitation for any survivors to meet me here in Chicago."

Harrison missed the next bit, which was drowned out by the scream of his tires against the pavement and his own screams. The car started to spin. It almost started to roll when its momentum ran out. It stood balanced on the two driver's side wheels for what must have been far shorter time than it seemed before it flopped back down onto all four wheels with an unceremonious thud.

"… further instructions. I'll be broadcasting until midnight, Eastern Daylight Time, for those of you still keeping track. Remember, come to Chicago. Tell your friends."

Harrison identified the initial chords of a Fleetwood Mac song whose title he could not recall as he attempted to refocus himself. His reflex to stomp on the brakes did not feel productive.

"Chicago," he said, just to hear it out loud, "is a thousand miles away."

This makes the text much, much easier to read. Notice how anytime there is a new person speaking, it is in a new paragraph. Notice also how he puts "Another person had survived" into its own paragraph to emphasize the point.

Paragraphs can be employed to stress certain words or phrases that you as the author want to make sure your reader sees. Readers are apt to miss sentences buried within long blocks of text.

This lesson was taken from my class an Introduction to Creative Writing.

© Copyright 2024 SolN . All rights reserved.

Write a Regular Review:

Regular reviews are a general comments about the work read. Provide comments on plot, character development, description, etc.

Write an In-line Review:

In-line reviews allow you to provide in-context comments to what you have read. You can comment on grammar, word usage, plot, characters, etc.

Read about the difference between regular and in-line reviews.

Upgrade To Premium Membership

Please upgrade to Premium Membership to view and comment on in-line reviews. As a basic member, you can only view the in-line reviews you have posted for other authors.

Connections with SolN

SolN is a member of:

Experiencing other login problems? We can help.

Use letters, numbers, apostrophes, periods, and hyphens.

13 Guidelines for When to Start a New Paragraph in Your Story

by Zoe M. McCarthy | Writing | 4 comments

“Paragraphs help readers make sense of the thousands of pieces of information a writer folds into a story.” —Beth Hill

by ardelfin

Does your editor or critique partner often suggest breaking up your paragraphs?

After researching online articles, I found:

- One hard-and-fast rule and 12 guidelines as to when to start a new paragraph. click to tweet

First, know:

- Fiction paragraphs are less structured than those in non-fiction. click to tweet

For fiction, you’ll construct your paragraphs for setups, punches, and other desired effects. For example, the one-word paragraph.

THE RULE: Always start a new paragraph when you switch speakers in dialog.

GUIDELINES: Start a new paragraph when

by mconnors

- a new character thinks something,

- a new idea enters,

- a new event happens,

- a new setting occurs,

- the reader needs a break from a long paragraph,

- the “camera” moves. Ray Bradbury suggested, as in movies, every time the camera angle changes, start a new paragraph,

- a portion of information isn’t closely related to another and needs to be distanced,

- a change in emphasis or tone is needed in a topic,

- the time moves forward or backward,

- a description of one thing ends and something else is described,

- a special effect is needed to add humor or drama.

EXAMPLE USING TIPS (Tip numbers in parentheses)

“How are we going to handle this one?” Jack said. (1, Rule)

Sandy nodded toward him. “You’re the expert.” (2)

When had he dealt with similar situations? How about the Haiti op? (10)

The pompous Haitian general had questioned Jack’s men. Jack had stuck up for his men’s reason for disobeying orders, but he’d conceded the general’s wisdom for questioning them. The general had respected that, and he’d sent Jack’s team away unharmed. (10)

If they were caught today, would that tactic work on the warlord? But Sandy wasn’t one of his men. (1, 7)

Sandy snapped her fingers in his face. “So, what’re we going to do? The warlord knows me.” (2, 7)

He couldn’t take Sandy out of the op. She was the only one who knew what to look for inside the warlord’s files. (3, 8, 11)

Sandy’s mother had told him about Sandy’s photographic memory. If he could get Sandy inside to scan the pertinent files in the warlord’s underground cave, that could give him all the information he needed. (4)

Rat-tat-tat. (9, 12)

The sound was close. (1, Rule)

Sandy grabbed his arm. “Was that gunfire?” (Rule)

“Yeah. We gotta put distance between the warlord’s goons and us.” (4, 7)

They swept up their gear and moved out. (5, 7)

On the other side of the village, Jack scanned the area. They needed a hiding place. (9, 12)

Do you have other tips for when to start a new paragraph?

Newsletter Signup

Please subscribe to my newsletter, Zoe’s Zigzags, and receive a free short story.”

Follow Blog Via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

My RSS Feeds

Recent Posts

25 tips for becoming a writer , 7 tips for using personal anecdotes in your stories, write the word your character would say.

- Consider Status in Dealings Between Characters

- When to Use a Hyphen in a Compound Adjective

American Christian Fiction Writers

You may also like

These twenty-five tips address general, story, character, and writing concerns that writers hear over and over.

Image by yogesh more from Pixabay Zoe McCarthy’s book, Tailor Your Fiction Manuscript in 30 Days, is a fresh and...

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay A concise, detailed, step by step resource for all writers. — Jamie West,...

Here’s my 2 cents to go with guideline #6, Zoe. When I wrote for the local newspaper in northern New York, I was taught to keep paragraphs short – 1-3 sentences if possible. The reason was that when they are printed in column form, even 3 sentences can appear quite long. They need to be broken up to keep the reader from feeling overwhelmed. Sentences within the paragraphs should also be shorter and more direct for the same reason.

Another tip is similar for writing on the Internet – such as in blogs. Keep paragraphs short and have white space in between. It acts as a rest for the eyes and helps to keep the reader reading.

Bonnie, so nice to have some real life examples. Thanks.

Chiming in on #6: Even in novels, many readers skip over long paragraphs. Breaking long ones into shorter paragraphs keeps things “hopping” visually, and leads the reader forward, generating a sense of action or building tension. The days of lengthy, descriptive paragraphs, a la Charles Dickens, are long gone. We love our words, but have to continually cut out extra modifiers, tighten writing, shorten sentences and paragraphs. This is an example of how hard that is to do!

Jane, your last sentence made me laugh. Thanks for your comment and the chuckle.

Pin It on Pinterest

Helping Writers Become Authors

Write your best story. Change your life. Astound the world.

- Start Here!

- Story Structure Database

- Outlining Your Novel

- Story Structure

- Character Arcs

- Archetypal Characters

- Scene Structure

- Common Writing Mistakes

- Storytelling According to Marvel

- K.M. Weiland Site

Critique: How to Use Paragraph Breaks to Guide the Reader’s Experience

As you may remember (or not) from school, a paragraph break in technical writing is meant to indicate a new thought. (I have clear memories of being required to find and underline the “topic sentence” that was the organizing thought of each new paragraph; it was a boring exercise, but looking back, I realize how well it’s served me.)

In fiction, we use the paragraph break a little differently (<—topic sentence!!!). Not only do our paragraph breaks signal a new thought, they can also be used to orient readers within the overall action: Who is acting? Who is speaking?

In ye olden days, what constituted a cohesive paragraph, even in fiction, was considerably more permissive. If you read the classics, you know it’s not uncommon to encounter paragraphs that last pages . These days, readers prefer to see more white space on the page. They want to read quickly, an ability aided by an author’s skillful use of “turn signals.”

Use paragraph breaks almost like punctuation, so you can guide your readers’ experience of your story’s action and pacing.

Learning From Each Other: New WIP Excerpt Analysis

Today’s post is the second in an ongoing series in which I am analyzing the excerpts you all have so kindly sent in. My approach to these critiques is a little different from those you normally see on writing blogs. Instead of editing each piece, I’m focusing on one particular lesson that can be drawn from each excerpt, so we can deep-dive into the logic and process of various useful techniques.

Today, my thanks to Erik Börjesson for sharing the following excerpt from his fantasy Rose of the Winds :

“Hey!” The squirrel leaped from the branch in a streak of red. She ran after it, weaving through a clung of sap trees and jumped over a thorn bush; the world passed her in streaks of colours and shapes. Where she was going was of no concern, what mattered was the squirrel and little more. The squirrel’s coat of brown and red blended in with the canopy of the trees as if it was wearing camoflauge. She held the camera with white fingers, its leather strap chafing her neck, a drop of sweat streaked down her forehead. A low branch came up ahead. Clara lunged to her knees, sliding over the forest floor, showering browned leaves and clods of dirt in her wake, her head barely missing the branch. She stopped, panting, her heart beating in her throat. Clara looked for the squirrel, turning around in circles. She finally spotted it clinging to the grey trunk of an ashtree. Quick as lightning, Clara bent down on one knee and focused in on the squirrel. Snap. “Gotcha.” She smiled a wicked smile and wiped the sweat from her forehead. The squirrel retreated to the safety of the canopy, relieved that the chase was over. Clara stood up and brushed the cakes of mud off her blue jeans; though, some of it still clung to them. She turned to leave, but then stopped. Where was the trail? It felt like something cold and nasty had turned her guts inside out. She looked around for something familiar. She spotted the low branch and went back and under it; she soldiered on. Next was a thorn bush. Clara walked and walked but found no bush. Was the tree with the low branch really the same one she had passed?

Even in this in medias res excerpt, Erik does a great job with forward momentum, thanks mostly to the character’s goal. She wants something, and that is the entire point of the scene. As the scene goes on (there’s a subsequent section I haven’t shared due to length constraints), it’s also clear he has a great grasp on scene structure . We start out with Clara’s goal to take a picture of the squirrel, encounter conflict as the squirrel runs away, and reach a “yes, but…” outcome when she succeeds in her goal, only to then have to react to the realization that she is lost. So good job, Erik!

However, today, I would like to use this opportunity to explore the how, when, and why of paragraph breaks. For starters, here is how I would edit the excerpt to add a significant number of paragraph breaks. You’ll immediately notice how much more white space this provides, which makes the piece less formidable, easier to read, and clearer in its presentation of action.

The squirrel leaped from the branch in a streak of red.

She ran after it, weaving through a clung of sap trees and jumped over a thorn bush; the world passed her in streaks of colours and shapes. Where she was going was of no concern, what mattered was the squirrel and little more.

The squirrel’s coat of brown and red blended in with the canopy of the trees as if it was wearing camouflage.

She held the camera with white fingers, its leather strap chafing her neck. A drop of sweat streaked down her forehead.

A low branch came up ahead.

Clara lunged to her knees, sliding over the forest floor, showering browned leaves and clods of dirt in her wake, her head barely missing the branch. She stopped, panting, her heart beating in her throat. She looked for the squirrel, turning around in circles.

She finally spotted it clinging to the grey trunk of an ash tree. Quick as lightning, she bent down on one knee and focused in on the squirrel.

“Gotcha.” She smiled a wicked smile and wiped the sweat from her forehead.

The squirrel retreated to the safety of the canopy, relieved that the chase was over.

Clara stood up and brushed the cakes of mud off her blue jeans, though some of it still clung to them. She turned to leave, but then stopped.

Where was the trail? It felt like something cold and nasty had turned her guts inside out. She looked around for something familiar. She spotted the low branch and went back and under it; she soldiered on. Next was a thorn bush. Clara walked and walked but found no bush. Was the tree with the low branch really the same one she had passed?

3 Rules of Paragraph Breaks

When and how you break for a new paragraph is as much a stylistic choice as anything else. Pacing will be a major consideration as well. Faster, choppier pacing does much better with shorter paragraphs—sometimes paragraphs of even just a single word. Slower, more leisurely—or more academic—pacing will usually do better with longer paragraphs, although you shouldn’t hesitate to break up dense sections of text when possible to make them more readable.

Truly, there are many rules of writing good paragraphs (some of which I talked about in this post: 8 Paragraph Mistakes You Don’t Know You’re Making ). But today I want to talk about three of the most important.

1. New Speaker = New Paragraph

Perhaps one of fiction’s most important rules for paragraphs is that of a “new line for every speaker.”

In a dialogue exchange between two or more characters, the different speakers should be separated by paragraph breaks.

Don’t do this :

“I’m not going with you,” Horace said. Judith glared. “Oh, yes, you are!”

“I’m not going with you,” Horace said.

Judith glared. “Oh, yes, you are!”

This instantaneously signals to readers the speaker is shifting. As a result, readers are able to keep up with the back and forth of the dialogue almost instinctively, especially if the author also skillfully includes dialog tags (he said) and action beats (she glared) to clarify who is saying what .

You will also want to insert a paragraph break into the midst of a single speaker’s dialogue if you are interspersing the dialogue with a second character’s non-verbal reactions. This brings me to an oft-overlooked and but equally important second rule…

2. New Actor = New Paragraph

Maybe you wondered why I ended up adding so many paragraph breaks to Erik’s scene when it has so little dialogue—and no conversational exchanges whatsoever.

The reason is that actors within narrative are treated the same as speakers . Usually, when characters exchange actions, the rules are the same as when they exchange dialogue. In Erik’s example, Clara acts, then the squirrel acts. We have two actors in this scene, which means each should get a new paragraph. The paragraph breaks give readers immediate signals about who is the doing the acting.

The exceptions to this rule all of which hark back to those grade-school adages about topic sentences. Sometimes, in some paragraphs, the emphasis will need to remain on a primary actor, rather than bouncing between the actions/reactions of multiple actors. For example, you may need to briefly indicate a response from a second character, but you’ll maintain a cohesive paragraph because the emphasis remains on a singular character or on a cooperative action or movement.

For example:

The servant unlocked the padlock with a great squeaking. The portcullis stuck when he tried to raise it, and the knights had help him lift it off the ground. They ducked under, and the manservant guided them across the courtyard, through the dusty shambles of the main foyer, and up two flights of stairs.

3. New Parts of Narrative = New Paragraph

Even in a scene which features or emphasizes one primary actor, paragraph breaks are often useful for guiding readers through the different types of action that character might be performing . These might include:

- Physical action: He revved the car.

- Physical reaction: His heart hammered.

- Dialogue: “You crazy driver!” she yelled.

- Indirect internal narrative: If these crazy people didn’t get out of the way, he was just going to run them over.

- Direct internal narrative: If these crazy people don’t get out of the way, I’m just going to run them over.

- Observation/description: Street lights blinked past.

Keep in mind these differentiated parts of the narrative will not always require their own paragraph break. An intimate sense of your pacing will help you decide when a break is best and when it isn’t. One good rule of thumb, however, is that if you spend more than two sentences on any one narrative type, it’s probably best to think about breaking for a new paragraph.

We might assemble the above examples like this:

He revved the car.

“You crazy driver!” she yelled.

His heart hammered. If these crazy people didn’t get out of the way, he was just going to run them over.

Street lights blinked past.

When set up like this, the man, the woman, and the street lights each ground themselves on new lines within their own topic sentences. The man’s indirect thought about running people over is introduced and grouped with his own related physical reaction.

An understanding of motivation-reaction units (MRUs) will help you ground your instincts for ordering the various parts of narrative. A proper MRU starts with the motivation or cause, then lines up the resulting effect as another string of causes and effects: feeling > thought > action > speech. Once you can differentiate between the roles of various sentences, you will have a better feel for when to break between them.

Paragraph breaks are important both as a tool for pacing your narrative and for subtly guiding readers through the nuances of your expanding story. Used skillfully, they create an inviting presentation of text that pulls readers in, keeps them grounded, and urges their eyes and imaginations forward through the prose.

My thanks to Erik for sharing his excerpt, and my best wishes for his story’s success. Stay tuned for more analysis posts in the future!

You can find further excerpt analyses linked below:

- 5 Ways to Successfully Start a Book With a Dream

- How to Use Paragraph Breaks to Guide the Reader’s Experience

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you prefer to err on the side of more or fewer paragraph breaks in your writing? Why do think this is? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music ).

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family !)

Sign Up Today

Related Posts

K.M. Weiland is the award-winning and internationally-published author of the acclaimed writing guides Outlining Your Novel , Structuring Your Novel , and Creating Character Arcs . A native of western Nebraska, she writes historical and fantasy novels and mentors authors on her award-winning website Helping Writers Become Authors.

I favor breaking paragraphs because large paragraphs tend to make me feel I’m getting lost in them and I don’t want my reader feeling lost. Then there’s another part of me that says, “I don’t have time for all of this.”

The exception to this may be a writer with the gift of literary gab like F. Scott Fitzgerald. I started reading ‘This Side of Paradise’ and was pulled into his large paragraphs by his gab. However there was a part of me that was wondering if he couldn’t have broken them up into smaller paragraphs?

But who am I to question a master of English?

By the way, I enjoyed the article and will copy and paste it into my Writing Tips folder.

Fitzgerald came out of a previous literary era that still favored longer paragraphs. If he wrote today, chances are he’d have been a little more liberal with his breaks.

An author/writing teacher named Randy Ingermanson describes MRUs as ‘public clips’ and ‘private clips,’ and that terminology/way of thinking has really helped me a lot. Public clips relate anything that is focused outside the viewpoint character, things that are observable by all. Private clips are focused on the main character, their actions, dialogue, and internal stuff.

I like that!

I use the change in paragraph style that predominantly alines with a change in character or scene. This article was a good refresher for those who still struggle. Thanks Katie.

As always, character is a deciding factor.

I noticed KM used a trio of asterisks to break up her work. In my writing, I add a pair of blank lines, a centered hashtag, and two additional lines. Then I continue with my next related paragraph.

What you’re referencing is a scene break. It’s an extra visual clue, beyond the simple line break, to tell readers that a new scene has begun.

If I can jump in here, much as I like sizable paragraphs, I’d almost go back to the big clunkers if it would keep writers from doing this:

Where was that boy? I stared ocean of people in the city square with its dizzying currents. I clutched my briefcase, tight. “Boy? Hello? Where’d you go?”

I was all alone.

In the world’s largest city.

Please, save the dramatic line breaks for breathtaking reveals. Otherwise it just seems like the writer is begging me believe the scene is dramatic — like they’re super insecure about it.

I agree one hundred percent. Less is usually more for that technique.

I agree. I have problem with emphasis like this, but, as you say, it should be used with moderation and saved for the most appropriate moments.

Excellent analysis and explanation of effective use of paragraph breaks. I would have edit the example pretty much the same way.

Thanks for stopping by!

Another reason for deciding how long paragraphs should be is to consider your market. A magazine using columns is going to need *very* short paragraphs – 100 words will seem enormous; an e-reader set on a normal font size will be overwhelmed by paragraphs of much more than 150 words; a paperback can take more without it becoming intrusive because of the size of the page and the amount of white space margins.

But I agree, pacing wins.

Definitely. Something I notice even in my own writing is how much bigger the paragraphs get when I look at my blog on my phone versus my computer. :p

I cosign everything you write here, and your examples are perfect. The errors you pointed out, and the rules you give, are exactly the “tells” between a book produced by indies who haven’t taken the time to learn formatting, and one produced by commercial tradpublishers. That said, I’ve seen academic publishers violate all these guidelines, which makes for a jarring experience, and turns a good story into a chore to read.

Folks, the guidelines are not pickiness. Best practices for layout has been studied in detail. My paper actually laid out the print pages on the basis of most readers (they had metrics) reading from left to right rather than top to bottom. A features editor who was in the minority of those who read top-to-bottom actually argued about layout with another features editor!

Bottom line, what you see on the published page isn’t an accident, nor the result of publishers all deciding to be weirdly uptight. Formatting conventions are based on the underlying desire to keep people reading, and are adhered to by people whose paychecks depend on fulfilling this desire.

Readers may not know the technical terms for the guidelines, but they instinctively know what’s correct when they see it. No matter how good your story, you absolutely can make reading it a chore by violating the norms, so it’s best to learn what they are. A good style guide — think “Words Into Type” (used by Baen) or Chicago Manual of Style (used by many other American publishers) or “New Hart’s Rules” (used by British publishers) can point to other conventions.

Besides, don’t you want to be able to induce tension and thrills and restfulness in a reader?

What you say here is not only an appropriate revelation for formatting and punctuation, but also for the sound reasons underlying almost all conventional fiction techniques. This is exactly why it’s important for writers to understand the reasons behind the “rules” before deciding to break them.

In a way, not knowing the rules is like leaving money on the table, which is yet another reason why this blog is such a great resource.

I agree–and thanks! 🙂

The first time I read through the piece, before it was broken up, I thought the squirrel was the one with the camera. (Oops.) The White Rabbit has a pocket watch in `Alice in Wonderland’ and Mrs. Beaver has a sewing machine in `The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe’. A squirrel with a camera wasn’t a huge stretch for me. 🙂

Sounds like a good writing prompt. 🙂

Ah, yes, paragraph breaks & topic sentences… It’s always a good thing to be reminded of what we learned in school! Thank you for the refresher course! I still read & love the classics, but I do like a fair bit of white space on the page.

I like how the paragraph breaks are used in this excerpt to control the pacing of the scene, especially when you have two characters playing off each other with lightning-fast action.

Erik, well done! I loved being in the woods with Clara chasing down that shot of the squirrel. (Squirrels are awesome – so much fun to write about! 😉

Totally agree about squirrels. I get happy every time I see one. 🙂

Can I split the main character/protagonist so that my POV character is not the one pursuing the overall story goal? I was just wondering if this ever goes over very well, or if it is even possible.

Definitely possible. See this post: Protagonist and Main Character— Same Person? The Answer May Transform Your Story!

In fiction I tend towards paragraph breaks between every thought, sometimes I have the opposite issue with white space where I wonder if I need to smoodge some paragraphs together to slow the pacing a little

Too many paragraph breaks can create a very choppy style. If that’s not what you’re going for, you can use the mentioned rules in “reverse” to figure out which sentences more naturally belong grouped together within the same paragraph.

I’ve always been told white space is our friend – meaning, use lots of paragraph breaks. I know for me when I read a book I’m turn away from long winded paragraphs. In the first example it felt very long-winded, but I had no problem with the way you put it after.

I usually go through my WIP and look for places that the paragraphs are too long and would turn the reader off. Turning the reader off is not something I want to do.

Thanks, Janice

One of the best rules of thumb for any writer is to treat readers how the writers themselves would like to be treated. Trying to read our own writings with that more objective eye can be extremely helpful even in making relatively “small” decisions like the paragraph breaks we’re talking about today.

Thanks! This gives me a lot to consider

I didn’t even try to read the first excerpt. The great wall of text looked very uninviting. Broken into paragraphs, I could just glance and see and get drawn in. I could immediately see what was going on and didn’t experience the whole “this looks like an investment of time that I don’t want to make” reaction. Anyway, I always err on the side of too many paragraph breaks, and appreciate it when others do too.

Interesting, isn’t it? Especially, since both examples contain the same number of words.

Another great post with helpful information.

I prefer more paragraph breaks, probably due to my short attention span. And the breaks provide a visual illusion, making a large amount of words appear less.

Text books should use this technique!

And I’m enjoying your book, “Wayfarer.”

Aw, thank you. That makes me happy. 🙂

It is a balancing act for me between paragraphs that are too long and too many smaller ones. I write a paragraph that may not seem that long on my screen, but then remember that it will appear longer on a book page. Not only that, but the struggle of too little or too much dialogue. I often wonder, have my characters been talking too long? Is there anything I can change from dialogue to exposition?

Dialogue is the workhorse of fiction. As long as it’s presented in a lively, entertaining, quasi-realistic fashion, it’s better to overuse it a little than underuse it.

This is a great series. Thank you for doing this.

Glad you’re enjoying it!

In your examples, each paragraph was left justified (i.e. not indented,) and a space between paragraphs. I have always liked this way of writing and find it easy to read. But I was told that you indent each of your paragraphs, and leave no spaces between them. Thus the indent indicates the paragraph break. I just looked back at one of your Kindle novels, (I have most of them,) and that is how the book is structured. Is it okay to write a novel using this left justification/white space approach, or would the editor scream at you? (Your latest book is in my queue to purchase soon.)

Keep in mind that the examples here are posted on the web, where there are different conventions than for published print. Some media share formatting rules, but not always. For instance, you still have to begin every sentence with a capital letter no matter what medium you publish in 🙂

For print and Kindle, especially with fiction, you really do have to indent the paragraph and not put breaking spaces between them. It’s unfriendly to put breaking spaces between paragraphs in your fiction (whether e-book or print) for two reasons:

1) Readers have been trained their whole lives to expect that paragraph break = scene break. If you violate the norm, then you’re forcing the reader to guess if you’re being quirky, or if you just don’t know how to format the books.

2) Traditionally, if a scene break occurred in a middle of a page in print, the paragraph break was sufficient to indicate the shift. This is insufficient on an ebook, because an e-reader’s settings might mean the scene break occurs at the end or beginning of a “page.” The print solution was to use either *** or a fleuron, at the beginning/end of the page, but for e-books some publishers wrongly omit those clues, which jars the reader. If you combine this omission with a practice of giving every paragraph a paragraph break, then you make it even worse for your reader.

The thing about conventional formatting is that it allows the reader to ignore formatting and just concentrate on the story, which is the goal. It’s a bad idea to force people to stop and guess how they’re supposed to read the story — “Huh, why did this scene just change? The characters are still having their conversation, and from the same character’s point of view. Did I miss something?”

If you hire an editor, or submit to an anthology, etc., they’ll let you know what their manuscript guidelines are, which typically won’t be the same formatting as the version typeset for publishing. FYI, traditional manuscript formatting used double spaced lines, as indicated in the classic “Writer’s Digest Guide to Manuscript Formatting” — just ignore the typewriter part 🙂 I can’t help but consider that double spaced lines were easy on the eyes …

This has to do with the medium in which the piece is published. Online publications usually format the way you see here, with a line between each left-justified paragraph. Printed material, however, will eliminate the extra lines between paragraphs and indent the first line. Glad you mentioned this!

Thanks for reading!

This is a great post for fine-tuning the awareness writers bring to their craft, and the examples nailed it. After breaking up the paragraphs, this scene had so much more life. Now I’m thinking about short chapters vs. long ones. I believe some of the same concepts apply.

The same principles of pacing apply. Shorter almost always contributes to a faster (and sometimes) choppier feel.

Interesting and helpful, as always. Thank you!

Glad you enjoyed it!

On a slightly different subject: It has long been said that the final sentence of one paragraph should relate to the first sentence of the next paragraph. I have noticed in recent years that there is a fashion to carry this to an extreme, so that what I would have called the “topic sentence” is moved up, from (where I would think) it belongs, to the end of the preceding paragraph.

Yeah, well, it’s the Wild West out there. 😉 The ultimate point of any technique is to make the writer’s intent as clear as possible to readers.

This was very informative. Thank you!

Thanks for commenting!

I just read a book by the Spanish author Javier Marias called The Infatuations. Very loooong paragraphs, sometimes extending beyond single pages. The text was pretty much stream-of-consciousness from the point of view of the female lead character. She was constantly analyzing and rethinking her own thoughts–almost like describing a multi-faceted diamond, turning it ever so slightly with each new thought and description. The thing is, the book is actually a murder mystery, and completely fascinating (to me.) It was written fairly recently, but the author clearly decided to treat it as if it were written much earlier–say by a contemporary of Proust! I know that lack of white space is a turnoff for many readers, but I had to agree with this author’s choice for this book. Beyond that, thank you for explaining the rules of paragraph-breaks! I was pretty much doing those things already, but now I know why!

Yes, stream of consciousness often contributes to very long paragraphs. I want to say (but could be mistaken) that one of Faulkner’s book is a single paragraph.

Thanks again for reminding a fiction writer that refamiliarizing ourselves with grammar and style rules can be useful! Though, sitting down and using a style manual is daunting.

By the way, with the writers block thing… be kind to yourself. You probably know how to deal with it.

I’m not convinced writers block is a real thing. It’s often not knowing well enough what you’re trying to say or it is your mind and body telling you to care for other parts of your life for a while.

Allow yourself to be slothsome or distracted for a while. Not everything needs tight control.

The best advice I was ever given (was not to lower my standards) but to write about why I wasn’t able to write. What stopped me or caused me problems. I would ramble on about plot issues, character issues or personal issues and how they affected my writing. Eventually some writing excitement would rekindle.

Thanks. It’s been an interesting month, but I made a big breakthrough shortly after recording the podcast. I’m sure I’ll be blogging about in the near future!

I had never broken it down like this (though I knew the first rule about the different speakers by heart). I worked off instinct, but thinking about the individual cogs is useful, especially when it comes to recommending certain tactics to others, since you can explain your reasoning.

Thanks so much!

I like cogs. 🙂

This is a great post. Thanks so much for it and all that you do for us.

I’m struggling a bit with internal narrative — specifically when to use direct internal narrative and when to use the indirect version. Have you done a post on this? If so, could you please point me in the direction of it?

You might find this post helpful: 5 Ways to Write Character Thoughts Worth More Than a Penny .

Basically, I would choose one method to use predominantly (I recommend indirect thoughts since they flow better with the overall narrative) and use the other only for purposeful emphasis in certain, brief situations.

Thanks so much Katy. That’s largely what I’ve been doing but I worried it might be a no-no to mix the two 🙂 That blog post is super helpful. Thanks heaps for taking the time to help me!

Glad to be of help!

Thanks for this. I was starting to wonder if sometimes I was putting in too many paragraph breaks. What you illustrate here confirms I’m doing it right. I’ve had no formal training, except for an online writing course, so I work mostly on instinct. Cheers.

Great insight on using paragraphs to drive the action! You rock, girlfriend! 🙂

Thanks for stopping by! 🙂

Thanks for explaining this so succinctly. I have read other explanations of MRUs that only confused me but now I think I understand.

This is a powerful post for me. It goes against everything I was taught in AP English 35 years ago. Of course, back then we were studying the classics. I have written a lot of articles for an Internet marketing company, and I used similar “rules” and made sure there was plenty of white space.

I’ve had a hard time transitioning the concept of paragraphs in fiction being only 1, 2, or 3 sentences. (I’m new to fiction writing.) My critique group has been urging me to do so, telling me that readers like white space. This is true, but it has felt like I’m dumbing down the paragraph structure.

Reading your rules and reasoning behind the rules makes it easier for me to “go along with the current trend.” I have to, regardless of whether I like it or not. But now, I’ll like it better since I understand it better. Thank you!

Am a little late (catching up on my emails) It’s funny every time I read one of your postings like this one I feel it should be kept hush-hush and hidden under the covers while reading it. Ah-hah-aha all mine! Sneaky, sneaky, sneaky! Lol!

quite a few other writers on different sites I go to don’t even try to learn anything new it floors me, I mean how can you not want to get better? ;-;

Anyway, thank you for this article I’ll learn it and apply it. <3 (She's so generous isn't she?) <3

[…] writers in the revision process, K. M. Weiland examines how to use paragraph breaks to guide the reader’s experience, and Janice Hardy warns us about red flag telling words that often spell trouble in our writing and […]

[…] Read more…. […]

[…] Critique: How to Use Paragraph Breaks to Guide the Reader’s Experience […]

[…] topic is pacing and line breaks. I came across this article which helped me to realise that I’ve not been writing awkwardly by doing things like […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Novel Outlining

- Storytelling Lessons From Marvel

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Write Your Best Book

Check out my latest novel!

( affiliate link )

Free E-Book

Subscribe to Blog Updates

Subscribe to blog posts rss, sign up for k.m. weiland’s e-letter and get a free e-book, love helping writers become authors.

Return to top of page

Copyright © 2016 · Helping Writers Become Authors · Built by Varick Design

Paragraphs in Fiction – What You Need to Know

Paragraph marks in a document published in 1500.

Have you thought about paragraphs lately?

If you’re a blogger or a copywriter, chances are good you think about them regularly. One, two, or three sentences—four is stretching it. And if you believe all blog post “paragraphs” should consist of one sentence only, you don’t have much to think about.

If you’re an essayist or academic writer, on the other hand, you probably focus on topic sentences, supporting evidence, and final sentences that serve as transitions to the next paragraph.

What about paragraphs in fiction?

If you’re like a lot of creative writers, paragraphs are the least of your concerns, at least early on. Maybe you start a new one by instinct or because it feels right. Or you might make a conscious choice, knowing that a change of location, time, or a new focus character needs a new passage.

But there’s more to paragraphs in novels than that.

Keep in mind that fiction writing is creative writing, and that means art more than science. So there really are no rules. But by getting a better understanding of the history and purpose of paragraphs and how to craft them for the effect you want, you’ll improve your writing. And what writer doesn’t want that ?

Paragraphs are tools

Long blocks of text are difficult for most readers to manage. But by breaking up text into sections with closely related ideas, readers are alerted to a shift when they see a paragraph marker—an indentation or a double space between paragraphs in many non-fiction articles, especially online. And as readers, our brains are trained to know that something will be different in a new paragraph, and we anticipate the change with little effort.

Paragraph markers are like stop signs; in fact, they’re considered punctuation just like commas, semi-colons, and periods. And they used to have their own symbol: the pilcrow (¶). It was used before indentation became a paragraph marker back in the 1600s, when the printing press was invented. And before that, sentences just went on and on.

We still use pilcrows behind the scenes in word processing software. Editors and proofreaders use them, too, for indicating a new paragraph is needed when marking a document by hand.

Paragraphs control the pace

Pacing refers to how quickly or slowly a story moves forward. It’s about the speed and rhythm of the storytelling and crafting each sentence, paragraph, and chapter for the desired effect. Pacing is also about the reading experience: Is it so slow that readers get bored? Is it so fast that readers get exhausted after a few chapters?

Let’s take movies as an example. Most start on the slow side so you get the information you need like the setting, characters, and main conflict or problem to overcome. Novels are the same way.

Now think of an action or fight scene. The pace picks up because the camera doesn’t linger in one position for long. Instead, the shots shift rapidly from one character to the next, or they zoom in and out for close-ups of characters and specific moves.

Imagine an entire movie paced like that.

In Atomic Blonde , notice the slow build-up in this fight scene. Picture it as a few paragraphs that describe the setting and provide dialogue. Notice how it’s evenly paced and relaxed with just a hint of suspense.

Then, suddenly, the camera delivers a burst of quick shots like short sentences. Pow! Bam! Wam! All the bad guys—down.

Short, choppy shots (and short, choppy paragraphs) convey action, excitement, or danger. Viewers or readers take in quick bites of information, and the fast pace amplifies the emotional reaction. Sentences are short. A few stand alone.

“Off with his head!”

In a novel, as the action winds down and the scene ends, longer sentences , longer paragraphs, and more description let readers catch their breath.

Paragraphs convey information that drives the plot

Paragraphs are categorized by the purpose they serve, but what they’re called depends on the authority you consult. Here are the most common types of paragraphs.

Expository paragraphs or exposition

The expository paragraph focuses on setting, characters, and mood.

In All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr, page after page of exposition greets us. In the paragraph below, notice the setting description. A single-sentence paragraph sets the mood, and the next paragraph introduces a character.

Beneath the lobby of the Hotel of Bees, a corsair’s cellar has been hacked out of the bedrock. Behind crates and cabinets and pegboards of tools, the walls are bare granite. Three massive hand-hewn beams, hauled here from some ancient Breton forest and craned into place centuries ago by teams of horses, hold up the ceiling. A single lightbulb casts everything in a wavering shadow. Werner Pfennig sits on a folding chair in front of a workbench, checks his battery level, and puts on headphones.. . .

The sentence concerning the lightbulb could be part of the longer paragraph, but separating it adds impact, don’t you think? And notice that the character introduction starts a new paragraph.

Narrative paragraphs

Narrative paragraphs tell the story from the narrator’s point of view (POV): 1st person (I, we), 3rd person (he, she, they), and occasionally 2nd person, in which the narrator addresses the reader (you) directly. These paragraphs tell the story and move it toward the ultimate challenge or battle: the climax.

Narrative paragraphs are also called “action paragraphs,” although action, in this case, doesn’t mean fights or battles.

Here’s an example of a narrative paragraph from All the Light We Cannot See.

Marie-Laure LeBlanc stands alone in her bedroom smelling a leaflet she cannot read. Sirens wail. She closes the shutters and relatches the window. Every second the airplanes draw closer; every second is a second lost. She should be rushing downstairs. She should be making for the corner of the kitchen where a little trapdoor opens into a cellar full of dust and mouse-chewed rugs and ancient trunks long unopened.

Dialogue paragraphs

You might think dialogue hardly counts as a paragraph, especially when it’s short. But conversations between characters can form the bulk of a novel, and the way you manage dialogue is important.

Dialogue paragraphs have three parts: the words spoken (or the quote sentence), the dialogue tag (he said, she said), and the unspoken actions or thoughts that add meaning to the quote.

In this example, once again from All the Light We Cannot See , there is no dialogue tag since it’s already clear who is speaking.

The guide hangs his cane on his wrist and rubs his hands together. “It’s a long story. Do you want to hear a long story?”

Here are two successive dialogue paragraphs that include tags but no additional information.

“Are you sure this is true?” asks a girl. “Hush,” said the boy.

And here is a dialogue paragraph with all three elements:

“I think,” Werner says, feeling as though some cupboard in the sky has just opened, “we just found a radio.”

Sometimes dialogue is lengthy, with only one character speaking. In this case, you can break up long paragraphs at strategic spots for easier reading.

Browse through a few of your favorite novels and see if you can spot different paragraph types.

When to start a new paragraph

You could consider writing an entire novel with only one long paragraph as David Albahari did in Leeches . But most of us will do much better sticking to tradition.

Here are some common reasons for starting a new paragraph:

- Something changes or a new topic is introduced

- Time or location changes

- A character enters a scene

- Break up a lengthy speech or monologue (including interior monologues)

- Create emphasis

Paragraphs might not seem like a big deal as you draft your story. But if you think about it, you build an entire novel with paragraphs. It’s like a movie that readers see in their minds, and if you don’t shoot each scene well, you won’t have the blockbuster, er, bestseller you’re hoping for.

Questions and comments are always welcome!

Image credit: Wikimedia Commmons. Villanova, Rudimenta Grammaticæ. Published 1500 in Valencia (Spain).

Just a quick note to tell you that I have a passion for the topic “Paragraphs in Fiction” at hand. I am going to share the post on my social media pages to see my friends and followers. I hope people can get a lot of information through this posting. Thanks and have a good day!

Thank you. I’m a baby fiction writer with dyslexia and due to it I often struggle with particular things, one of which being when to start paragraphs. This was extremely helpful for me. My current work of fiction is nearing the end of its first draft and soon I’ll be trying to edit it and work in paragraphs where needed. So I have saved this for future reference. Thank you a bunch!

Leave a Comment

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Previous Post: How to Write the First Line and Paragraph of Your Novel

Next Post: What Causes Writer’s Block and How to Beat It

Get Updates and The Writer's Guide—Free

- Content Creation and Blogging

- Creative writing

- Editing and Proofreading

- General writing

- SEO and Content Optimization

- Tech Tools and Tips

- The Business of Writing

- Writer's Toolbox

- Writing Techniques and Tips

- Mastering the Art of Content Writing: Tips for Beginners

- From Blank Page to Brilliance: 47 ChatGPT Prompts for Writing

- Blog vs. Blog Post: What’s the Difference?

- What stops you from writing? + 10 writing prompts

- Self-Editing Skills Improve by Reading the News

- Free Writer Tools Plus Low-cost Options

- Need Writing Motivation? Camp NaNoWriMo Is the Answer

- How to Focus When You Feel Frazzled

- Why Writers Should Read + Reading Lists

- What Are Filter Words?

- Are -ing words really that bad?

- Writer’s Voice: What it is and how to develop yours

- What’s the difference between editing and proofreading?

- How to get 5 important writing skills without college

- Why Write a Short Story?

- How to write blog posts faster with an outline

- The Em Dash and How to Use It Correctly

- How to focus on writing: 5 tips that work

- 10 Essential Editing Tips

- Are you making this terrible punctuation mistake?

- 15 Writing Mistakes That Make You Look Like a Beginner

- That or Which: When to Use Them and Why It Matters

- Jazz up your sentences with these 5 tips

- What is a Sentence? Here’s What You Need to Know

- Kill Your Adjectives — Well, Most of Them

- Get Started in Screenwriting and Write That Box Office Hit

Copyright © 2015-2024 Leah McClellan

- Term 1 Professional Development

- Term 2 Professional Development

- Term 3 Professional Development

- Term 4 Professional Development

- School Visits

- PD via Skype

- Professional Development On Demand

- VCE English Essays

- How To Teach VCE Texts

- The How To Teach Series

- Shakespeare Units

- Geography Units

- History Units

- How To Teach Popular Texts

- English Units

- PD On Demand

- Subscribe to our blog

- The Senior English Writing Handbook (New edition)

- The Student Guide To Writing Better Sentences 1

- The Student Guide To Writing Better Sentences 2

- The VM Literacy Handbook 1

- The VM Literacy Handbook 2

- Class Set Orders

- Smashing VCE Study Book

- The Senior English Writing Handbook

- The Student Guide to Writing Better Sentences

- Romeo and Juliet Textbook

- Macbeth Textbook

- Wordsworth Textbook

View Cart Checkout

- No products in the cart.

Subtotal: $ 0.00

Creative Paragraphs

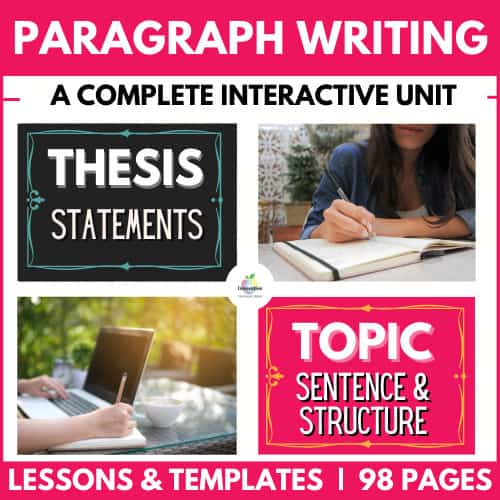

We can spend a lot of time when we teach analytic and persuasive writing in teaching paragraph structure. You’ve all heard of one of these and will probably have your own variations:

- TEE – topic sentence, evidence, explanation

- TEEL – topic sentence,evidence, explanation, link

- PEE – point, evidence, explanation

But how do we approach teaching paragraphs in creative writing? Like any writing, creative writing needs to be chunked into units to help the reader better make sense of what is happening or being described. But unlike other types of writing, we don’t want students to follow formulaic patterns – we want them to be…well…creative. And that’s the catch 22 of teaching creative writing, isn’t it? How to give students strategies for being creative without leading them to be formulaic. The key is to show students different models and to encourage them to experiment. Below is a resource you can provide to students to show them different models of creative writing. Download the handout here: Creative Paragraphs

Along with giving them handouts like the one below, you can also engage in paragraph creation activities. Here is a version of one of our favourite very short stories (only one and a bit pages) call Francis with no paragraphs: Francis No Paragraphs . After explaining some ‘rules’ about paragraphing, ask students to read through the story and divide it into paragraphs. Stress that there is no right or wrong, but they will need to have reasons for their divisions. Compare what students come up with and then compare it to the paragraphing the original author used: Francis

Like any paragraph, creative paragraphs should be about one idea. However, unlike other types of writing, creative paragraphs can be:

- Long or short (sometimes even just one sentence)

- Have topic sentences in different places or no clear topic sentence at all

Start with the main idea: A beginning sentence that is like a topic sentence – it explicitly states the topic of the rest of the paragraph

It was an empty and lonely place. Everywhere you looked, all you could see were grey houses, dead lawns and rubbish blown about by the wind. One building had the words ‘get out now’ scrawled all over it. Cars with open doors creaking in the wind butted up against each other in the middle of the road as if they were discarded toys. Not a single human sound could be heard.

Show the main idea: A series of sentences which clearly describe, narrate or discuss the same thing without ever clearly stating it

Everywhere you looked, all you could see were grey houses, dead lawns and rubbish blown about by the wind. One building had the words ‘get out now’ scrawled all over it. Another had a great vine that had nearly completely swallowed it up. In the middle of the main road, cars with open doors creaking in the wind butted up against each other as if they were discarded toys left by some child. Not a single human sound could be heard.

Finish with the main idea: The topic sentence is at the end rather than the beginning

Everywhere you looked, all you could see were grey houses, dead lawns and rubbish blown about by the wind. One building had the words ‘get out now’ scrawled all over it. Another had a great vine that had nearly completely swallowed it up. In the middle of the main road, cars with open doors creaking in the wind butted up against each other as if they were discarded toys left by some child. It was an empty and lonely place.

Have one short, main idea: Paragraphs only need to be one sentence long, especially if the follow and emphasise an idea in a preceding paragraph

Everywhere you looked, all you could see were grey houses, dead lawns and rubbish blown about by the wind. One building had the words ‘get out now’ scrawled all over it. Another had a great vine that had nearly completely swallowed it up. In the middle of the main road, cars with open doors creaking in the wind butted up against each other as if they were discarded toys left by some child.

It was an empty and lonely place.

Author: tickinglogin

Related posts.

Two useful vocabulary websites November 18, 2020

Strategies to teach students to organise and sequence ideas October 21, 2020

Collaboration and group work in the remote English classroom May 7, 2020

Virtual Communication with Students April 20, 2020

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Fiction Writing Basics

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource discusses some terms and techniques that are useful to the beginning and intermediate fiction writer, and to instructors who are teaching fiction at these levels. The distinction between beginning and intermediate writing is provided for both students and instructors, and numerous sources are listed for more information about fiction tools and how to use them. A sample assignment sheet is also provided for instructors. This resource covers the basics of plot, character, theme, conflict, and point-of-view.

Plot is what happens in a story, but action itself doesn’t constitute plot. Plot is created by the manner in which the writer arranges and organizes particular actions in a meaningful way. It’s useful to think of plot as a chain reaction, where a sequence of events causes other events to happen.

When reading a work of fiction, keep in mind that the author has selected one line of action from the countless possibilities of action available to her. Trying to understand why the author chose a particular line of action over another leads to a better understanding of how plot is working in a story

This does not mean that events happen in chronological order; the author may present a line of action that happens after the story’s conclusion, or she may present the reader with a line of action that is still to be determined. Authors can’t present all the details related to an action, so certain details are brought to the forefront, while others are omitted.

The author imbues the story with meaning by a selection of detail. The cause-and-effect connection between one event and another should be logical and believable, because the reader will lose interest if the relation between events don’t seem significant. As Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren wrote in Understanding Fiction , fiction is interpretive: “Every story must indicate some basis for the relation among its parts, for the story itself is a particular writer’s way of saying how you can make sense of human experience.”

If a sequence of events is merely reflexive, then plot hasn’t come into play. Plot occurs when the writer examines human reactions to situations that are always changing. How does love, longing, regret and ambition play out in a story? It depends on the character the writer has created.

Because plot depends on character, plot is what the character does. Plot also fluctuates, so that something is settled or thrown off balance in the end, or both. Traditionally, a story begins with some kind of description that then leads to a complication. The complication leads up to a crisis point where something must change. This is the penultimate part of the story, before the climax, or the most heightened moment of a story.

In some stories, the climax is followed by a denouement, or resolution of the climax. Making events significant in plot begins with establishing a strong logic that connects the events. Insofar as plot reveals some kind of human value or some idea about the meaning of experience, plot is related to theme.

Character can’t be separated from action, since we come to understand a character by what she does. In stories, characters drive the plot. The plot depends on the characters' situations and how they respond to it. The actions that occur in the plot are only believable if the character is believable. For most traditional fiction, characters are divided into the following categories:

- Protagonist : the main or central character or hero (Harry Potter)

- Antagonist : opponent or enemy of the protagonist (Dark Lord Voldemort)

- Foil Character : a character(s) who helps readers better understand another character, usually the protagonist. For example in the Harry Potter series, Hermione and Ron are Harry's friends, but they also help readers better understand the protagonist, Harry. Ron and Hermione represent personalities that in many ways are opposites - Ron is a bit lazy and insecure; Hermione is driven and confident. Harry exists in the middle, thus illustrating his inner conflict and immaturity at the beginning of the book series.

Because character is so important to plot and fiction, it’s important for the writer to understand her characters as much as possible. Though the writer should know everything there is to know about her character, she should present her knowledge of the characters indirectly, through dialogue and action. Still, sometimes a summary of a character’s traits needs to be given. For example, for characters who play the supporting cast in a story, direct description of the character’s traits keeps the story from slowing down.

Beginning and intermediate level writers frequently settle for creating types, rather than highly individualized, credible characters. Be wary of creating a character who is a Loser With A Good Heart, The Working Class Man Who Is Trapped By Tough Guy Attitudes, The Lonely Old Lady With A Dog, etc. At the same time, keep in mind that all good characters are, in a sense, types.

Often, in creative writing workshops from beginning to advanced levels, the instructor asks, “Whose story is this?” This is because character is the most important aspect of fiction. In an intermediate level workshop, it would be more useful to introduce a story in which it is more difficult to pick out the main character from the line-up. It provides an opportunity for intermediate level fiction writers to really explore character and the factors that determine what is at stake, and for whom.

Conflict depends on character, because readers are interested in the outcomes of people’s lives, but may be less interested in what’s at stake for a corporation, a bank, or an organization. Characters in conflict with one another make up fiction. Hypothetically, a character can come into conflict with an external force, like poverty, or a fire. But there is simply more opportunity to explore the depth and profundity in relationships between people, because people are so complex that conflict between characters often gets blurred with a character’s conflict with herself

The short story, as in all literary forms, including poetry and creative nonfiction, depends on the parts of the poem or story or essay making some kind of sense as a whole. The best example in fiction is character. The various aspects of a character should add up to some kind of meaningful, larger understanding of the character. If the various aspects of a character don’t add up, the character isn’t believable. This doesn’t mean that your characters have to be sensible. Your characters may have no common sense at all, but we have to understand the character and why she is that way. The character’s motives and actions have to add up, however conflicted, marginalized or irrational they may be.

Perfect Paragraph Writing: The Ultimate Guide

Perfect paragraph writing is easy

A glance around any shopping mall crowded with teenagers on school break would suggest that our young people spend a reasonable amount of time writing. Sure, most of this writing is done with their thumb on a screen, but it’s still writing.

Yes, but tapping out a 280-character Tweet isn’t the ideal route to constructing well-organized writing pieces. To prepare our students to write coherently, they need to understand how to organize their ideas on paper. The ability to write strong paragraphs is an essential part of this.

Unfortunately, recent studies show that surprisingly few college graduates can achieve this, despite writing and communications skills being the most requested job requirements across all industries – including engineering and IT. Clearly, there is a pressing need for a strong focus on writing skills in the classroom.

For the most part, we live in a post-illiterate world. We can all read and write. This is undoubtedly a great thing, but it can lead to complacency for some of our students. At times there is an unwillingness to learn the craft of writing. A reluctance to learn how to organize writing in favor of just plunging in. The cost of this devil-may-care approach is, most often, clarity and coherence.

Fortunately, teaching what appears to be an apparently amorphous skill, such as writing, can be broken down into transparent step-by-step processes, and this includes how to write well-structured, coherent paragraphs.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING PARAGRAPH WRITING

This complete PARAGRAPH WRITING UNIT takes students from zero to hero over FIVE STRATEGIC LESSONS to improve PARAGRAPH WRITING SKILLS through PROVEN TEACHING STRATEGIES.

BE SURE TO READ OUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO SENTENCE STRUCTURE

Before you can master paragraph writing, you will need a good understanding of constructing meaningful sentences.

We have a complete guide to sentence structure for teachers and students. Click here to view.

WHAT IS A PARAGRAPH? A DEFINITION

To teach our students how to effectively write paragraphs we need to clearly define what a paragraph is. Assuming your students understand how to construct a solid sentence, paragraphs are the next step to creating a lucid piece of writing. They are the main building blocks in the construction of a comprehensible text.

Paragraphs are a group of single sentences united by a single topic or idea that help keep writing organized. They help the writer organize their thoughts during the writing process and further help the reader follow the thread of those thoughts in the reading. How paragraphs are used will depend, to some extent, on the genre of writing the students are engaged in, but any piece of writing longer than a few sentences will generally benefit from being organized into paragraphs.

A simple way to help students to recognize paragraphs is to have them count the number of paragraphs on a page, either in a book or projected onto the whiteboard. Have them note too, that there are two ways to delineate a paragraph: indentation or skipping a line. Both methods are fine, just ensure the student chooses one method and sticks to it. If you indent there is no need to skip a line – and vice versa.

Writing starts with planning. It’s a bit like gazing at a beautiful cathedral or temple we visit on vacation. Once it was obscured by scaffolding and busy workers that were eventually peeled away to reveal the beauty beneath. The planning stage of writing serves the same purpose as architectural blueprints, that is: to foresee the problems of construction and solve them before building begins. It is often helpful to consider paragraphs as distinct units in the planning process. Now, let’s take a look at the structure of paragraphs and how they work.

HOW TO STRUCTURE A PARAGRAPH

The three-part structure of an essay – introduction, body, and conclusion is echoed in the underlying structure of most paragraphs. There are two concepts essential to understanding in the writing of the perfect paragraph:

i. Thesis Statement: The thesis statement represents the main idea of the text as a whole and usually occurs in the opening paragraph.

ii. Topic Sentence: The first sentence of each paragraph thereafter usually introduces a single central idea in support of the previously mentioned thesis statement.

The topic sentence also serves the purpose of unifying the other sentences in the paragraph, while further setting up the order of those sentences. While the majority of paragraphs will contain a topic sentence and that topic sentence will come first, there are, as always, some exceptions. A narration of the sequence of events may not require the use of a topic sentence or changing paragraphs because of a change of speaker in dialogue, for example.

Subsequent sentences following the topic sentence should all relate back to the topic sentence and either discuss the point raised or support that point through the provision of evidence and examples. A good acronym that conveys this is P.E.E.L.

Point: Make the central argument or express the main idea in the topic sentence.

Evidence: Back up the point made by providing evidence or reasons. Evidence may take the form of quotations from a text or authority, reference to historical events, use of statistics etc.

Explanation: Explain the point and how the evidence provided supports it.

Link: Provide a bridge into the next paragraph at the end of the current paragraph by using a transition that links to the next paragraph and the main idea or thesis statement.

WHEN TO BEGIN A NEW PARAGRAPH

One of the more common difficulties for students is to recognize when it is time to begin a new paragraph. This often occurs because the student fails to distinguish between the thesis statement and the topic sentence. While the thesis (or more broadly, the theme) will remain consistent throughout the piece of writing, each paragraph should focus on a different point in support of that thesis.

Another useful way to determine when to start a new paragraph is to note that a new paragraph is necessary when there is a change of focus on a:

Person: This could be a character in a story or an important figure in history, for example. This could also refer to a change in speaker when writing dialogue. When there is a significant shift in focus from one person to another in a piece of writing, it’s time to indent or skip a line!

Place: As with a changing focus on a person, a shift from one location to another is most often best noted with a corresponding change in paragraphing. Instruct students that a move to a new paragraph in their writing is symbolic of the physical change of place – this will help them remember to start a new paragraph.

Time: Important shifts in time most often require a new paragraph too. These changes in time may be a mere matter of minutes or a significant movement through different historical periods. If the change in time opens up new material to the reader, students must mark this in their paragraphing.

Topic: Though usually united by the thesis statement or similar, a piece of writing will often explore clearly differentiated topics in its course. Usually, these topics will become apparent during the planning process. Each clearly identified topic will require at least one dedicated paragraph.

HOW LONG IS A PARAGRAPH? / HOW MANY SENTENCES IN A PARAGRAPH?

The question of how many sentences are in a paragraph, or how long is a paragraph is a common one. Unfortunately, there is no definitive answer to this question as quality paragraphs are measured in the ideas and concepts addressed rather than sentences and word counts.

Analytics of millions of paragraphs tell us that most paragraphs are approximately 100 – 200 words in length and are made up of 3 – 5 sentences but it must be stressed that this is purely a statistical coincidence and nothing more.

Excellent paragraphs can range from 12 words to 12 sentences when written correctly as you will discover from this guide.

HOW TO WRITE AN INTRODUCTION PARAGRAPH

Your introductory paragraph should contain the thesis statement. The Thesis statement usually appears at the middle or end of the introductory paragraph of a paper, providing a concise summary of the main point or claim of the piece of writing.

Your thesis statement should not exceed one sentence and is a guiding light for your essay or piece of writing.

The last sentence of an introduction paragraph should also contain a “hook” driving the reader to the next paragraph and onwards throughout your piece of writing as a whole.

Daily Quick Writes For All Text Types

Our FUN DAILY QUICK WRITE TASKS will teach your students the fundamentals of CREATIVE WRITING across all text types. Packed with 52 ENGAGING ACTIVITIES

HOW TO WRITE A CONCLUSION PARAGRAPH

The purpose of your conclusion is to wrap up your piece of writing as a whole. In your conclusion, you should summarize what you initially stated in your thesis statement without just repeating it word for word.