- Writing Prompts

150+ Story Starters: Creative Sentences To Start A Story

The most important thing about writing is finding a good idea . You have to have a great idea to write a story. You have to be able to see the whole picture before you can start to write it. Sometimes, you might need help with that. Story starters are a great way to get the story rolling. You can use them to kick off a story, start a character in a story or even start a scene in a story.

When you start writing a story, you need to have a hook. A hook can be a character or a plot device. It can also be a setting, something like “A young man came into a bar with a horse.” or a setting like “It was the summer of 1969, and there were no cell phones.” The first sentence of a story is often the hook. It can also be a premise or a situation, such as, “A strange old man in a black cloak was sitting on the train platform.”

Story starters are a way to quickly get the story going. They give the reader a place to start reading your story. Some story starters are obvious, and some are not. The best story starters are the ones that give the reader a glimpse into the story. They can be a part of a story or a part of a scene. They can be a way to show the reader the mood of a story. If you want to start a story, you can use a simple sentence. You can also use a question or an inspirational quote. In this post, we have listed over 150 story starters to get your story started with a bang! A great way to use these story starters is at the start of the Finish The Story game .

If you want more story starters, check out this video on some creative story starter sentences to use in your stories:

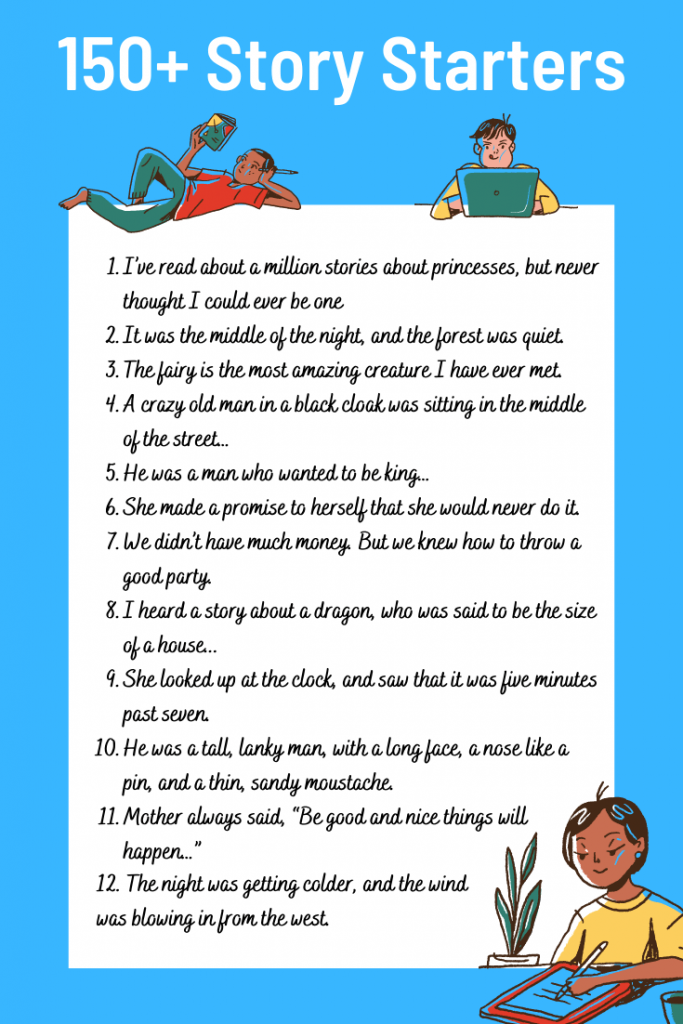

150+ Creative Story Starters

Here is a list of good sentences to start a story with:

- I’ve read about a million stories about princesses but never thought I could ever be one.

- There was once a man who was very old, but he was wise. He lived for a very long time, and he was very happy.

- What is the difference between a man and a cat? A cat has nine lives.

- In the middle of the night, a boy is running through the woods.

- It is the end of the world.

- He knew he was not allowed to look into the eyes of the princess, but he couldn’t help himself.

- The year is 1893. A young boy was running away from home.

- What if the Forest was actually a magical portal to another dimension, the Forest was a portal to the Otherworld?

- In the Forest, you will find a vast number of magical beings of all sorts.

- It was the middle of the night, and the forest was quiet. No bugs or animals disturbed the silence. There were no birds, no chirping.

- If you wish to stay in the Forest, you will need to follow these rules: No one shall leave the Forest. No one shall enter. No one shall take anything from the Forest.

- “It was a terrible day,” said the old man in a raspy voice.

- A cat is flying through the air, higher and higher, when it happens, and the cat doesn’t know how it got there, how it got to be in the sky.

- I was lying in the woods, and I was daydreaming.

- The Earth is a world of wonders.

- The fairy is the most amazing creature I have ever met.

- A young girl was sitting on a tree stump at the edge of a river when she noticed a magical tree growing in the water.

- My dancing rat is dressed in a jacket, a tie and glasses, which make him look like a person.

- In the darkness of the night, I am alone, but I know that I am not.

- Owls are the oldest, and most intelligent, of all birds.

- My name is Reyna, and I am a fox.

- The woman was drowning.

- One day, he was walking in the forest.

- It was a dark and stormy night…

- There was a young girl who could not sleep…

- A boy in a black cape rode on a white horse…

- A crazy old man in a black cloak was sitting in the middle of the street…

- The sun was setting on a beautiful summer day…

- The dog was restless…”

- There was a young boy in a brown coat…

- I met a young man in the woods…

- In the middle of a dark forest…

- The young girl was at home with her family…

- There was a young man who was sitting on a …

- A young man came into a bar with a horse…

- I have had a lot of bad dreams…

- He was a man who wanted to be king…

- It was the summer of 1969, and there were no cell phones.

- I know what you’re thinking. But no, I don’t want to be a vegetarian. The worst part is I don’t like the taste.

- She looked at the boy and decided to ask him why he wasn’t eating. She didn’t want to look mean, but she was going to ask him anyway.

- The song played on the radio, as Samual wiped away his tears.

- This was the part when everything was about to go downhill. But it didn’t…

- “Why make life harder for yourself?” asked Claire, as she bit into her apple.

- She made a promise to herself that she would never do it.

- I was able to escape.

- I was reading a book when the accident happened.

- “I can’t stand up for people who lie and cheat.” I cried.

- You look at me and I feel beautiful.

- I know what I want to be when I grow up.

- We didn’t have much money. But we knew how to throw a good party.

- The wind blew on the silent streets of London.

- What do you get when you cross an angry bee and my sister?

- The flight was slow and bumpy. I was half asleep when the captain announced we were going down.

- At the far end of the city was a river that was overgrown with weeds.

- It was a quiet night in the middle of a busy week.

- One afternoon, I was eating a sandwich in the park when I spotted a stranger.

- In the late afternoon, a few students sat on the lawn reading.

- The fireflies were dancing in the twilight as the sunset.

- In the early evening, the children played in the park.

- The sun was setting and the moon was rising.

- A crowd gathered in the square as the band played.

- The top of the water tower shone in the moonlight.

- The light in the living room was on, but the light in the kitchen was off.

- When I was a little boy, I used to make up stories about the adventures of these amazing animals, creatures, and so on.

- All of the sudden, I realized I was standing in the middle of an open field surrounded by nothing but wildflowers, and the only thing I remembered about it was that I’d never seen a tree before.

- It’s the kind of thing that’s only happened to me once before in my life, but it’s so cool to see it.

- They gave him a little wave as they drove away.

- The car had left the parking lot, and a few hours later we arrived home.

- They were going to play a game of bingo.

- He’d made up his mind to do it. He’d have to tell her soon, though. He was waiting for a moment when they were alone and he could say it without feeling like an idiot. But when that moment came, he couldn’t think of anything to say.

- Jamie always wanted to own a plane, but his parents were a little tight on the budget. So he’d been saving up to buy one of his own.

- The night was getting colder, and the wind was blowing in from the west.

- The doctor stared down at the small, withered corpse.

- She’d never been in the woods before, but she wasn’t afraid.

- The kids were having a great time in the playground.

- The police caught the thieves red-handed.

- The world needs a hero more than ever.

- Mother always said, “Be good and nice things will happen…”

- There is a difference between what you see and what you think you see.

- The sun was low in the sky and the air was warm.

- “It’s time to go home,” she said, “I’m getting a headache.”

- It was a cold winter’s day, and the snow had come early.

- I found a wounded bird in my garden.

- “You should have seen the look on my face.”

- He opened the door and stepped back.

- My father used to say, “All good things come to an end.”

- The problem with fast cars is that they break so easily.

- “What do you think of this one?” asked Mindy.

- “If I asked you to do something, would you do it?” asked Jacob.

- I was surprised to see her on the bus.

- I was never the most popular one in my class.

- We had a bad fight that day.

- The coffee machine had stopped working, so I went to the kitchen to make myself a cup of tea.

- It was a muggy night, and the air-conditioning unit was so loud it hurt my ears.

- I had a sleepless night because I couldn’t get my head to turn off.

- I woke up at dawn and heard a horrible noise.

- I was so tired I didn’t know if I’d be able to sleep that night.

- I put on the light and looked at myself in the mirror.

- I decided to go in, but the door was locked.

- A man in a red sweater stood staring at a little kitten as if it was on fire.

- “It’s so beautiful,” he said, “I’m going to take a picture.”

- “I think we’re lost,” he said, “It’s all your fault.”

- It’s hard to imagine what a better life might be like

- He was a tall, lanky man, with a long face, a nose like a pin, and a thin, sandy moustache.

- He had a face like a lion’s and an eye like a hawk’s.

- The man was so broad and strong that it was as if a mountain had been folded up and carried in his belly.

- I opened the door. I didn’t see her, but I knew she was there.

- I walked down the street. I couldn’t help feeling a little guilty.

- I arrived at my parents’ home at 8:00 AM.

- The nurse had been very helpful.

- On the table was an array of desserts.

- I had just finished putting the last of my books in the trunk.

- A car horn honked, startling me.

- The kitchen was full of pots and pans.

- There are too many things to remember.

- The world was my oyster. I was born with a silver spoon in my mouth.

- “My grandfather was a World War II veteran. He was a decorated hero who’d earned himself a Silver Star, a Bronze Star, and a Purple Heart.

- Beneath the menacing, skeletal shadow of the mountain, a hermit sat on his ledge. His gnarled hands folded on his gnarled knees. His eyes stared blankly into the fog.

- I heard a story about a dragon, who was said to be the size of a house, that lived on the top of the tallest mountain in the world.

- I was told a story about a man who found a golden treasure, which was buried in this very park.

- He stood alone in the middle of a dark and silent room, his head cocked to one side, the brown locks of his hair, which were parted in the middle, falling down over his eyes.

- Growing up, I was the black sheep of the family. I had my father’s eyes, but my mother’s smile.

- Once upon a time, there was a woman named Miss Muffett, and she lived in a big house with many rooms.

- When I was a child, my mother told me that the water looked so bright because the sun was shining on it. I did not understand what she meant at the time.

- The man in the boat took the water bottle and drank from it as he paddled away.

- The man looked at the child with a mixture of pity and contempt.

- An old man and his grandson sat in their garden. The old man told his grandson to dig a hole.

- An old woman was taking a walk on the beach. The tide was high and she had to wade through the water to get to the other side.

- She looked up at the clock and saw that it was five minutes past seven.

- The man looked up from the map he was studying. “How’s it going, mate?”

- I was in my room on the third floor, staring out of the window.

- A dark silhouette of a woman stood in the doorway.

- The church bells began to ring.

- The moon rose above the horizon.

- A bright light shone over the road.

- The night sky began to glow.

- I could hear my mother cooking in the kitchen.

- The fog began to roll in.

- He came in late to the class and sat at the back.

- A young boy picked up a penny and put it in his pocket.

- He went to the bathroom and looked at his face in the mirror.

- It was the age of wisdom and the age of foolishness. We once had everything and now we have nothing.

- A young man died yesterday, and no one knows why.

- The boy was a little boy. He was not yet a man. He lived in a house in a big city.

- They had just returned from the theatre when the phone rang.

- I walked up to the front of the store and noticed the neon sign was out.

- I always wondered what happened to Mary.

- I stopped to say hello and then walked on.

- The boy’s mother didn’t want him to play outside…

- The lights suddenly went out…

- After 10 years in prison, he was finally out.

- The raindrops pelted the window, which was set high up on the wall, and I could see it was a clear day outside.

- My friend and I had just finished a large pizza, and we were about to open our second.

- I love the smell of the ocean, but it never smells as good as it does when the waves are crashing.

- They just stood there, staring at each other.

- A party was in full swing until the music stopped.

For more ideas on how to start your story, check out these first-line writing prompts . Did you find this list of creative story starters useful? Let us know in the comments below!

Marty the wizard is the master of Imagine Forest. When he's not reading a ton of books or writing some of his own tales, he loves to be surrounded by the magical creatures that live in Imagine Forest. While living in his tree house he has devoted his time to helping children around the world with their writing skills and creativity.

Related Posts

Comments loading...

How to Start a Story: 10 Ways to Get Your Story Off to a Great Start

by Joslyn Chase | 0 comments

Perhaps you’ve heard the old publishing proverb: The first page sells the book; the last page sells the next book. I’m convinced there’s a mammoth grain of truth in that. The beginning and the end of any story are critical elements that you really want to nail. Today, we’re going to focus on how to start a story—in other words, how you can craft a spectacular beginning that will hold readers spellbound and get them to turn that first all-important page.

Whether you’re pitching to an agent, a publisher, or direct to the reader, your opening lines form the basis for how they’ll judge the rest of your story. You have about a sixty-second window of influence before that initial judgment solidifies. It follows that this is a good place to invest your time and effort.

Granted, a compelling opening is not an easy task to accomplish. Besides grabbing the reader's attention, you want to ground readers in a setting, establish voice, hint at theme, and introduce a protagonist readers can get behind. To do this, you need to answer specific questions for your reader, while at the same time planting others.

Story Revolves Around Questions

Cultivating questions for your reader is what keeps them turning the pages, but you’ll lose them if you don’t provide answers, as well. If you want your reader to commit to your story, it’s best to establish a few essentials right up front.

- Whose story is it? You’re asking your reader to spend serious time with your protagonist. They’ll want to know who they’ll be rooting for.

- What kind of story is it? Readers go into a book looking for a particular type of reading experience and you need to let them know they’ve come to the right place.

- When and where is the story happening? Setting is hugely important to selling your reader. I did a workshop with top editor Kristine Kathryn Rusch, and one of the most frequent critiques she gave writers was: “There’s no setting. You lost me on setting.”

- What’s the story behind the story? When readers think story, they think plot. Writers know the real story is internal—not what happens, but how those events affect the characters. While you won’t necessarily lay your hero open on the first page of your story, hinting at his internal struggle gets the reader on his side.

- Why should the reader care? The most glorious descriptions or action-packed drama won’t hook your reader if you don’t give them a reason to care about your character. Answering the four questions above will help do this, but you’ll need to give more.

10 Compelling Ways to Start a Story

You’ve got to command reader attention and answer some important questions, but what does that look like on the page? How do you structure your opening to accomplish those objectives?

Have you heard of modeling? Life coaches and success gurus talk about it a lot. It involves finding someone who’s wildly effective at doing what you want to do and studying their methods to duplicate their success. If in doubt, go to the opening pages of bestselling books in your chosen genre and see how the masters did it.

Beyond that, there are so many ways to go. Here are ten ways to start a story you might consider:

1. Strong Voice

Example: “Mae Mobley was born on a early Sunday morning in August 1960. A church baby we like to call it. Taking care a white babies, that’s what I do, along with all the cooking and the cleaning. I done raised seventeen kids in my lifetime. I know how to get them babies to sleep, stop crying, and go in the toilet bowl before they mamas even get out a bed in the morning.” The Help, Kathryn Stockett

Example: “I smiled when I saw the dead girl. Just for a moment. Reflex, I suppose.” The Snow Angel, Doug Allyn

2. Relevant Anecdote

Example: “When Ella Brady was six she went to Quentins. It was the first time anyone had called her Madam. A woman in a black dress with a lace collar had led them to the table. She had settled Ella’s parents in and then held out a chair for the six-year-old. ‘You might like to sit here, Madam, it will give you a full view of everything,’ she said. Ella was delighted.” Quentins, Maeve Binchy

Example: “I hope this video camera works. Anyway, this (click) is a blowup of a model’s eye, the bluest I’ve ever seen. The only other time I remember seeing that exact color of blue was the day my sister Nicole drowned. It was everwhere: in the water, in the sky, Nicole’s skin. Blue, I remember, and coughing.” Forgetting The Girl, Peter Moore Smith

3. Intriguing Mystery

Example: “Who am I? And how, I wonder, will this story end?” The Notebook, Nicholas Sparks

Example: “People’s lives—their real lives, as opposed to their simple physical existences—begin at different times. The real life of Thad Beaumont, a young boy who was born and raised in the Ridgeway section of Bergenfield, New Jersey, began in 1960. Two things happened to him that year. The first shaped his life; the second almost ended it.” The Dark Half, Stephen King

4. Uneasy Suspense

Example: “The smell of newly rotting flesh hit Jakaya Makinda. He stopped his Land Rover, grabbed his binoculars off the seat beside him, and trained them in the direction of the odor’s source.” Death in the Serengeti , David H. Hendrickson

I used this as an example of Uneasy Suspense, but Hendrickson kicked it off with a startling first sentence and infused it with setting, layering the effect.

Example: “Water gushed out of the corroded faucet into the chipped, porcelain tub, pooling at the bottom with a few tangled strands of long, brown hair. The water was easily 120 degrees. So hot that Katelyn Berkley could hardly stand to dip her painted green toenails into it. The scalding water instantly turned her pale skin mottled shades of crimson.” Envy, Gregg Olsen

5. Stirring Theme

Example: “I became what I am today at the age of twelve, on a frigid overcast day in the winter of 1975. I remember the precise moment, crouching behind a crumbling mud wall, peeking into the alley near the frozen creek. That was a long time ago, but it’s wrong what they say about the past, I’ve learned, about how you can bury it. Because the past claws its way out.” The Kite Runner, Khaled Hosseini

I used this excerpt as an example of stirring theme, but it is bursting with other elements and could be placed under setting, suspense, voice, character, world tilting off-center, and an enthralling first sentence.

Example: “Sometimes it’s overwhelming: the burden of knowing that the man you most admire isn’t real. Then the depression that you’ve fought all your life creeps in, the anxiety. The borders of your life contract, stifling, suffocating.” The Adventure of the Laughing Fisherman, Jeffery Deaver

This one’s got a pretty kicking first sentence, too.

6. Dynamic Setting

Example: “Out of a cloudless sky on a windless November day came a sudden shadow that swooped across the bright aqua Corvette. Tommy Phan was standing beside the car, in pleasantly warm autumn sunshine, holding out his hand to accept the keys from Jim Shine, the salesman, when the fleeting shade touched him. He heard a brief thrumming like frantic wings. Glancing up, he expected to glimpse a sea gull, but not a single bird was in sight.” Tick Tock, Dean Koontz

This is also a nice instance of uneasy suspense.

Example: “They were parked on Union, in front of her place, their knees locked in conference around the stick shift, Janna and Justin talking, necking a little, the windows just beginning to steam.” Shared Room on Union, Steven Heighton

7. Quirky or Startling Opening Sentence

Example: “The world had teeth and it could bite you with them anytime it wanted.” The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon, Stephen King

Example: “As soon as he stepped into the dim apartment he knew he was dead.” Garden of Beasts, Jeffery Deaver

Both of these examples also instill suspense, as they suggest danger and leave the reader anxious to find out more.

8. Compelling Character

Example: “First the colors. Then the humans. That’s usually how I see things. Or at least, how I try.” The Book Thief, Markus Zusak

What kind of character is this you ask yourself, compelled to go on.

Example: “Everyone knows this kid. He is dirty and dumb and sits in a corner, lonely, but not alone. His face has an involuntary twitch, and when he makes eye contact, his lids and cheeks squeeze his eyes shut. We call him Blinky. Blinky rolls with it, though, smiles big and toothy when kids shout his name across the schoolyard.” A Bottle of Scotch and a Sharp Buck Knife, Scott Grand

I chose this for character, but it’s got a big dose of voice in it, as well.

9. Tilting World

Example: “The ravens were the first sign. As the horse-drawn wagon traveled down the rutted track between rolling fields of barley, a flock of ravens rose up in a black wash. They hurled themselves into the blue of the morning and swept high in a panicked rout, but this was more than the usual startled flight. The ravens wheeled and swooped, tumbled and flapped. Over the road, they crashed into each other and rained down out of the skies. Small bodies struck the road, breaking wing and beak. They twitched in ruts. Wings fluttered weakly. But most disturbing was the silence of it all.” The Doomsday Key, James Rollins

Is there any doubt the world in this story is twisting off its axis?

Example: “On the afternoon I met my new neighbor, a woman others in the cul-de-sac would dub ‘Ramba,’ I wasn’t looking for trouble. In fact, I wasn’t looking for anything other than to enter my first full month of retirement with a small military pension and dreams of a hop to Florida or Hawaii once a year until my expiration date arrived.” Many Dogs Have Died Here, James Mathews

Nothing explicit occurs off the bat, but Mathews sets up for the punch. This poor sucker’s world is tilting.

10. Engaging Dialogue

Example: “'You look like crap, Pen.' Pendleton Rozier, my longtime mentor, opened the door wide, then coughed into the crook of his elbow. ‘If only I felt that good.’” Rule Number One, Alan Orloff

Example: “'Which is even weirder yet,’ Gowan said. ‘But that ain’t the best part.’ At approximately which point, Kramer didn’t want to hear any more. It had been a mistake to let Gowan get started. He went outside into the mild March evening to take a leak and get away from Gowan for a little while before hitting the sack. ‘Seriousy, I got the skinny on ‘em,’ Gowan said, unzipping and joining him at the edge of the porch.” Spring Rite, Tom Berdine

You’ll notice writing voice and character here, too.

Invest in a Great Beginning

Spending the time and effort to craft a superb opening for your story is a good investment. However, worrying over it can hold you up. If you’re spinning your wheels over how to start a story, just get something down and move on.

Then, when you’ve reached the end of your story and you have a better understanding of the theme, tone, and characters, you can go back and fine tune or start from scratch to design your perfect beginning.

Beautiful Bookends

In fact, doing so may afford you the opportunity to bookend your story with a beginning and ending that reflect on each other, enclosing your entire story in a nice, thematic package that’s very satisfying to readers.

For instance, my thriller novel Nocturne In Ashes opens with the protagonist, a concert pianist, bombing her comeback performance. Then at the end, after surviving a series of harrowing experiences and battling her inner flaw, she’s gained the confidence she needed and nails the Beethoven that was her downfall.

I’ve touched on some ideas to get you off to a great start, but there are many other types of openings to explore. If you’re having trouble, hit the library and see how others have done it. You’re sure to find something that works for your story. And have fun!

How about you? Do you struggle with how to start a story? What book openings have made an impression on you? Tell us about it in the comments section .

Using one of the types of openings outlined above, write the beginning for a story idea you have in mind, or choose from one of these prompts:

Stella is nervous about meeting her ex-husband for dinner.

Darren takes his son on a hunting trip, determined to teach him how to be a man.

Cheryl wants to try out for the girls’ softball team, but the captain is her ex-best-friend.

Write for fifteen minutes and when you’re finished, post your work in the practice box below. And if you post, be sure to leave feedback for your fellow readers!

Joslyn Chase

Any day where she can send readers to the edge of their seats, prickling with suspense and chewing their fingernails to the nub, is a good day for Joslyn. Pick up her latest thriller, Steadman's Blind , an explosive read that will keep you turning pages to the end. No Rest: 14 Tales of Chilling Suspense , Joslyn's latest collection of short suspense, is available for free at joslynchase.com .

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Rejected Book: 3 Reasons Editors Reject Manuscripts - […] strong opening is critical to grabbing the editor’s attention and giving your story a hope of making the first…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

- How to write a story

- How to write a novel

- How to write poetry

- How to write a script

- How to write a memoir

- How to write a mystery

- Creative journaling

- Publishing advice

- Story starters

- Poetry prompts

- For teachers

Great Story Beginnings

by N. Strauss

Story beginnings are important, and in terms of getting published, they’re THE most important part of a story. On this page, you'll learn how to start a story in a way that hooks readers and sets up the right expectations.

Skip to topic: - Facing the blank page - Hooking your reader - Conflict - Character arcs - Setting expectations - Examples - Mistakes to avoid

How to write story beginnings

The beginning of a story is where the reader (or editor) decides whether to keep reading. The beginning also sets the reader's expectations for the story’s middle and ending.

But don't let the importance of your story beginning intimidate you or make it hard to start writing. Some writers freeze up at the sight of a blank page; they feel that everything has to be perfect right away. It doesn't. Remember: even though the beginning is the first part of your story most people will read, it doesn't have to be the first part that you write. And you can always go back and improve your beginning later.

Your first task is to get something—anything—onto that blank page. If it doesn't come out right, then let it come out wrong. No problem. You’ll fix it afterward.

Unless you're very lucky, the perfect story beginning may not occur to you until you're at the revision stage. Then it is time to turn the first page, the first paragraph, the first line of your story into an invitation that the reader can't refuse.

Hooking your reader

How can you capture the reader's attention right away? Here are some strategies to consider:

1) Make the reader wonder about something. For example, let's say you mention that your character is terrified of going to school that day, but you don't say why (yet). The missing information raises a question in the reader's mind and provokes curiosity. The reader will want to read on to find an answer to the question.

2) Start with a problem or conflict. This could be a small problem; for example, your character is about to miss their bus home. Even a small problem gives your main character something to do and creates some activity and momentum right away.

3) Start at an exciting point in the story. Don't be afraid to start your story right in the middle of the action. But provide enough clues to orient your readers and make sure they can follow what's happening.

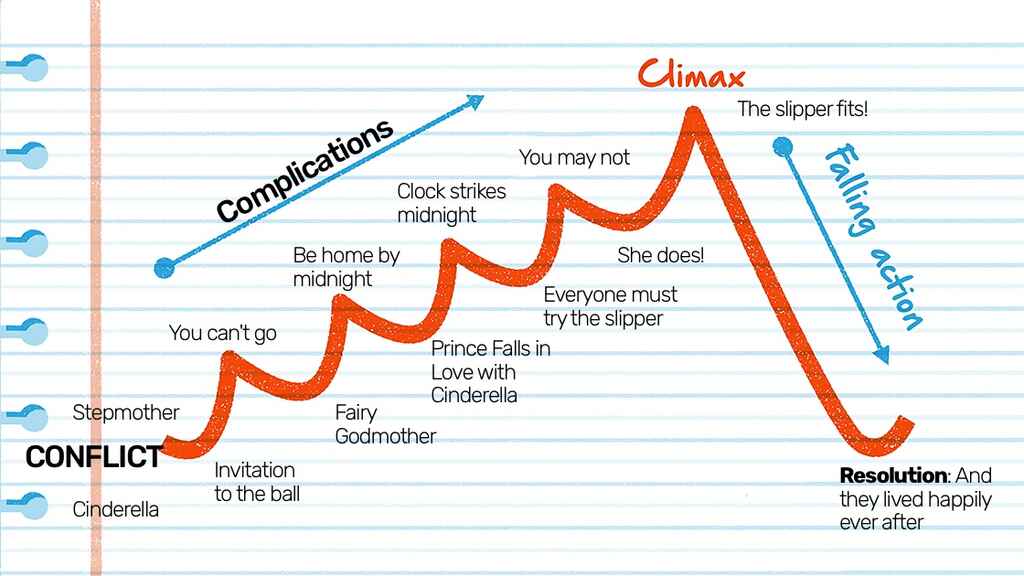

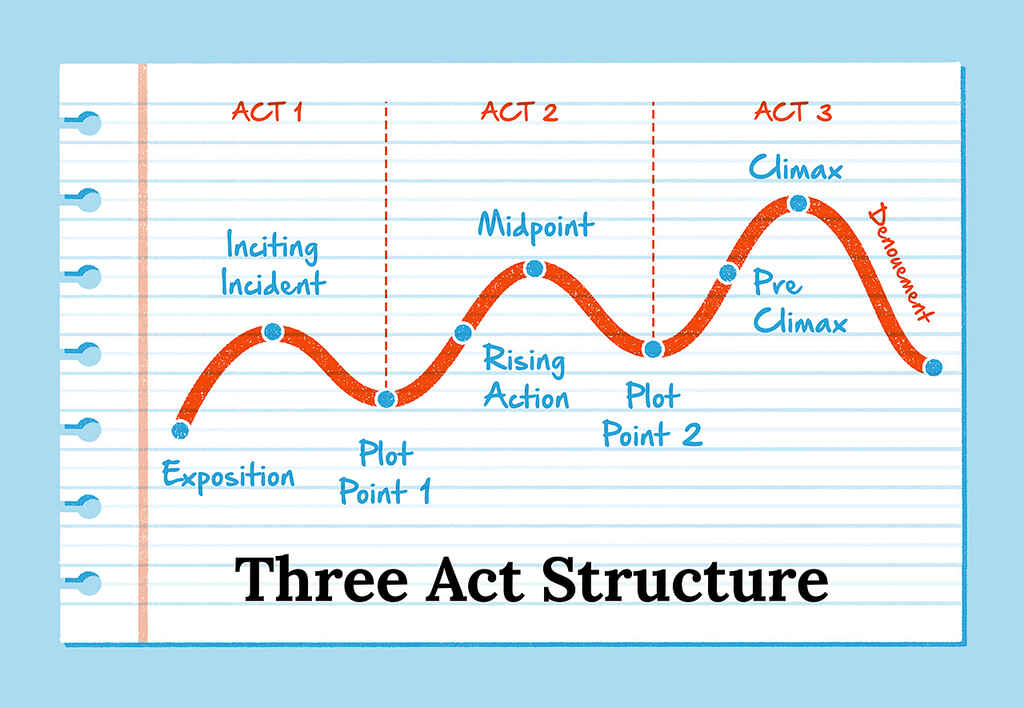

Story beginnings and conflict

A traditional story plot is centered around a character struggling to overcome a problem or reach a goal. This struggle is the story conflict and gives the story momentum.

Readers turn pages to find out if the character will succeed or fail in their struggle.

The first part of a story sets up the main conflict.

Often, a novel opens with a character in their ordinary life before something happens to shake up the character's world.

For example, your character is nervously rushing to get ready for an important job interview when she gets a text message from a phone number she doesn't recognize. "Your husband doesn't love you," the message says. "He loves me." (The story conflict will center on the breakdown of the character's marriage. The text message just kicked it off.)

In a short story, you don't have much room, so you'll normally want to kick off the conflict right away. The first line of a short story might be: Her phone pinged.

Or, even better: "Your husband doesn't love you."

Or, the short story might start weeks after the character received that text message. The tension has been building between her and her husband, and things have finally reached a breaking point. The first line of the story is: She hurled her wine glass against the wall.

If you're writing a novel, you have more room, so you might spend some time showing the character's marriage before it's shattered by the text message. Then, when the text message arrives out of the blue, readers will understand what it means for the character.

Tip: If you don't start the main story conflict right away, you can keep the reader's interest by introducing mini-conflicts. For example, before the main character gets the text message about her husband's affair, she might be worried she'll be late to her job interview. The opening line might be: I'll never make it, she thought, glancing at the oven clock.

Story beginnings and character arcs

Another job of your story beginning is to introduce your main characters.

When I say 'introduce', I DON'T mean writing a formal introduction like this:

Olga was an attractive 35-year-old bank teller with a warm, extroverted personality, though she could also be impulsive and had a quick temper that sometimes got her in trouble...

That kind of introduction is a bit boring, and it doesn't make readers feel like they know the character.

Instead, you can SHOW the character doing and saying things that reveal what they're like.

Does Olga have trouble controlling her temper? Instead of saying so, you can show losing her temper during a job interview, sabotaging her chances of getting the job.

Readers will get to know your character the same way we get to know people in real life—by watching them in action.

The first part of a story is a chance to show:

- character flaws that will cause the story conflict, or make it worse

- character strengths that will allow them to overcome challenges during the story

- aspects of the character (habits, behaviors, beliefs, ways of thinking) that will change by the story's end.

Stories are generally more satisfying when the character evolves or changes in some way over the course of events. There's a "Before" version of the character who enters the story conflict, and an "After" version who emerges.

During the beginning of the story, you can show a "Before" version of the character in a way that will stand in contrast with the "After" version.

Setting readers' expectations

So, we've already talked about several tasks of your story beginning, including hooking readers' interest, introducing your main character and their world, and setting up your story conflict.

You don't have to accomplish all of this in your opening line! But you can keep these tasks in mind as you're writing the first part of your story.

Another task of your beginning is to set readers' expectations for the rest of the story.

What kind of story is it going to be? If it's a horror novel, readers will read with one set of expectations, and if it's a romantic comedy they'll read with another.

Readers who believe they've signed up for a romantic comedy will be upset if all of the characters are brutally slaughtered by a serial killer.

Does your story take place in the real world, or in a version of the world where magic exists? If there's magic, what rules and limitations does the magic have?

Let's say you're writing a World War II novel. Your hero, an American spy, is captured by the Germans, but escapes by summoning a dragon and flying away on its back.

If the dragon rescue occurs on Page 1, that's fine.

Also fine if it occurs on Page 254 but readers have known all along that the hero is a famous dragon tamer.

On the other hand, imagine that the novel reads as a realistic portrayal of World War II until Page 254, when there's a surprise dragon rescue. Readers will feel betrayed, like you've switched the rules on them.

They won't believe in the dragon rescue because you haven't trained them to believe in it.

As a writer, you get to set the rules of the game. But readers want to understand the rules, or else the game doesn't feel fair.

Examples of story beginnings

Let's look at some examples of story beginnings and the work each one is doing.

Example: BELOVED

BELOVED by Toni Morrison is a novel about characters who are literally haunted by the trauma of slavery. Here are the first two sentences.

"124 was spiteful. Full of a baby's venom."

In the first pages of BELOVED, readers learn that 124 is a house belonging to a formerly enslaved woman in 1873 Cincinnati. The house is haunted by the ghost of the woman's dead child.

This story beginning:

- provokes curiosity

- establishes the rules of this story's world (ghosts exist).

- immediately set up conflict.

Example: ELEGY FOR APRIL

Here's the opening sentence of Benjamin Black's mystery novel, ELEGY FOR APRIL:

"It was the worst of winter weather, and April Latimer was missing."

In one sentence, Black both sets up the novel's atmosphere and lets us know what the story's going to be about. The novel's first pages show April's friend Phoebe searching for April in foggy weather. Phoebe's actions start the plot moving right away, while Black's evocative descriptions of the fog create a sense of mood. Black introduces characters important to the story by showing them in action.

Example: "Gryphon"

Charles Baxter's short story "Gryphon" is about an eccentric and possibly sinister substitute teacher who disrupts the main character's world. Here's the first line:

"On Wednesday afternoon, between the geography lesson on ancient Egypt's hand-operated irrigation system and an art project that involved drawing a model city next to a mount, our fourth-grade teacher, Mr. Hibler, developed a cough."

In one sentence, Baxter shows the main character's ordinary world before the substitute teacher disrupts it—and shows the event that will set the plot in motion: a cough, that will get worse and cause Mr. Hibler to stay home, setting the stage for the substitute teacher's arrival.

Example: KLARA AND THE SUN

Here's the first line of Kazuo Ishiguro's novel KLARA AND THE SUN:

"When we were new, Rosa and I were mid-store, on the magazines table side, and could see through more than half of the window."

This sentence provokes curiosity because it's strange. "When we were new." What does that mean?

Quickly, readers gather that the novel is written from the point of view of a robot named Klara in a future version of our world.

The opening pages show Klara's daily existence in the robot store before Klara is sold to a family and the story's real conflict begins.

Example: "Ship in a Bottle"

Elizabeth Strout's short story "Ship in a Bottle" is about an 11-year-old girl named Winnie, who is forced to choose sides in a conflict between her sister Julie and her mother, Anita. Here's the story's opening line (Anita is speaking to Julie):

"You'll have to organize your days," Anita Harwood was saying, wiping at the kitchen counter.

By starting with dialogue, Strout pulls us right into the scene. She also introduces the character of Anita, showing her trying to control Julie's life. And she immediately sets up the conflict between Anita and Julie.

Example: SPINNING SILVER

Naomi Novik's novel SPINNING SILVER is based on the fairy tale "Rumpelstiltskin". Here's the first sentence:

"The real story isn't half as pretty as the one you've heard."

The novel's opening page goes on to remind us of the traditional version of "Rumpelstiltskin". It lets us know what kind of novel this is going to be—a fairy-tale retelling. And it provokes our curiosity by hinting that the "Rumpelstiltskin" we know has been sanitized in some way. Now we're wondering what the REAL story is...

Mistakes to avoid

Here are some common problems to watch out for as you’re revising your story beginning:

1) Starting with background information. For example, inexperienced writers sometimes start out with little biographies of their main characters. These story beginnings feel a little bit like Wikipedia articles about people who don't exist. They are not very interesting to read. Don't feel like you have to provide all of the information upfront. You can start your story with a scene or action and gradually weave in background details when/if they become necessary for the reader's understanding.

2) Starting too early in the story. If your story seems to take a long time to get interesting, consider starting right at the interesting point. You might have to lop off a few pages. Don't feel bad about throwing away part of your draft—those pages you throw away are not wasted work. They are part of a necessary process of exploration that showed you where your story has to go.

TIP: Someone once said that most short story manuscripts can be improved by cutting the first page, and most novel manuscripts by cutting the first chapter. See if you can improve your beginning by cutting.

3) Starting a different story. The creative process often leads writers down unexpected paths. You start out with a certain story in mind then are surprised at where it leads. As a result, the story's beginning (even if it seemed perfect when you wrote it) may not be an ideal fit with the rest of the story. When that happens, ask yourself: which version of the story do you like better? The version you started out writing? Or the version you ended up with? Based on your answer to this question, you know which part of the story you have to rewrite.

Click here to get our free fiction-writing course, Beginnings, Middles, and Endings.

How to Start a Story - Next Steps

Join our free email group for more writing tips and ideas. You might also enjoy:

- Our 8-week course, Story Structure

- How to Craft a Story Plot

- How to Write a Mystery

- How to Write a Novel Outline

- How to Write a Novel

About the author

N. Strauss taught creative and expository writing at the University of Michigan before moving to the Czech Republic and then Spain. She has an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from the University of Michigan and a B.A. in English from Oberlin College. In 2009, she founded Creative Writing Now in collaboration with the author Linda Leopold Strauss, who has taught writing courses for the Institute of Children's Literature and published children's books with Scholastic, Holiday House, Houghton Mifflin, and others.

© 2009-2024 William Victor, S.L., All Rights Reserved.

Terms - Returns & Cancellations - Affiliate Disclosure - Privacy Policy

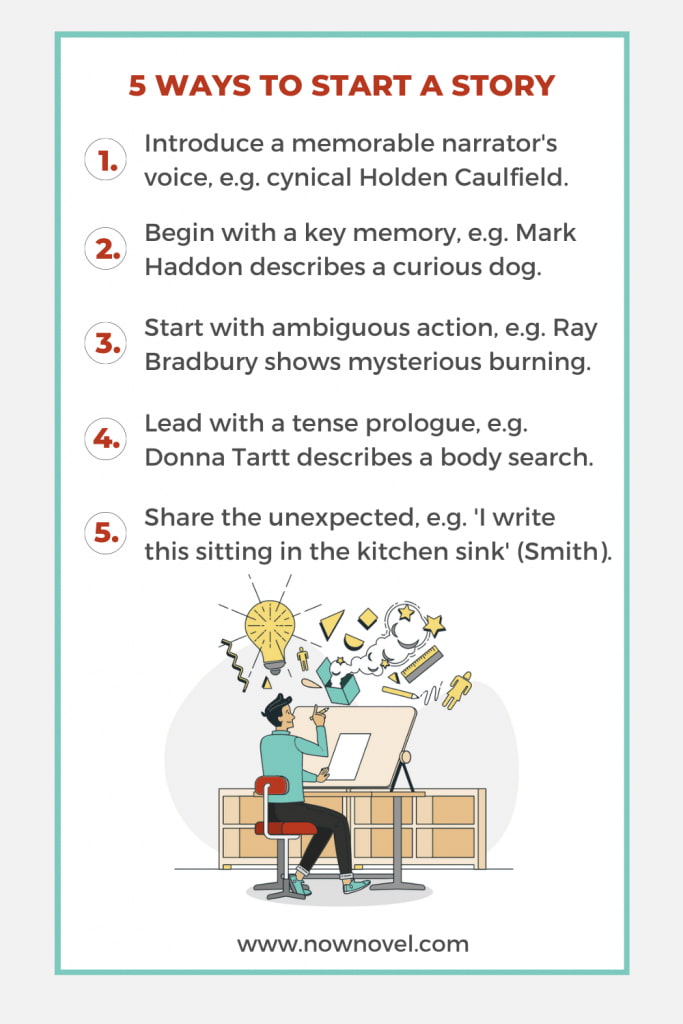

5 ways to start a story: Choosing a bold beginning

Great authors show us there are many ways to start a story. You could begin a novel with a narrator/character introducing himself, like Salinger’s Holden Caufield or Dickens’ David Copperfield. Or you could begin in the thick of action, as Ray Bradbury’s does in his classic novel, Fahrenheit 451.

- Post author By Jordan

- 46 Comments on 5 ways to start a story: Choosing a bold beginning

Great authors show us there are many ways to start a story. You could begin a novel with a narrator/character introducing himself, like Salinger’s Holden Caufield or Dickens’ David Copperfield. Or you could begin in the thick of action, as Ray Bradbury’s does in his classic novel, Fahrenheit 451 .

Have a read of the opening page or pages of authors you love, and explore how each starts a story, and notice how each is distinct from the other. A Stephen King novel will begin very differently from a Lianne Moriarty story, for example. Is there any bad writing? What makes it so, and what can you learn from it? Have they used active voice or passive voice? How does this change the opening? Compare a few to get a sense of the differences, and how each author’s distinct style comes through.

Before you begin, write down your story idea or your story structure. This doesn’t have to be a outline, but merely a few lines, stating the premise of that story.

Ways to start a story that engage your reader

These five types of story beginnings work:

Introduce readers to a memorable narrator-protagonist

Begin with crucial memories, start with ambiguous action, lead with a purposeful prologue, open with the unexpected.

Watch the summary video on ways to begin stories now, then read discussion of the story beginnings below:

This is how to start a story about a character coming of age or grappling with internal conflict . These novels typically use first person narration. From the first line, the reader gets to know a characterful narrator. Decide whether you will use a first person narrator, or another point of view.

For example, Salinger’s Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye (1951) has a strong voice and clear, disaffected teen persona:

‘If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.’ J.D. Salinger, Catcher in the Rye (1951)

This opening is effective because we get a strong sense of the character’s personality in his terse use of curse words, slang and adjectives (‘crap’, ‘lousy’). Being addressed directly by the narrator creates a sense of closeness and familiarity. This effect is similar to Charlotte Bronte’s ‘Reader, I married him’ in Jane Eyre .

Another strong example of this story opening type, the protagonist/narrator introduction, is Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955). Nabokov begins his entire novel with his depraved anti-hero, Humbert Humbert, musing on the name of Lolita, the young object of his obsession:

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta. Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita (1955)

Nabokov’s opening is strong because personality and character psychology are present from the first line.

When you start a story with your main character introducing themselves, remember to:

- Give them a distinctive voice: The grandiose language of Humbert Humbert fits the character, as do Salinger’s teen’s own cynical words.

- Show what matters to your character/narrator from the start: Holden values authenticity (‘if you want to know the truth’). We get a visceral sense of Humbert’s creepy obsession with Lolita through his rapture at even saying her name.

Often novels open with narrators recalling memories that are core to the plot. This can be part of the writing process and is of the ways to start a story that builds on a strong hook that is closely linked to your main plot. Tweet This

Starting with memories requires knowing your character well, such as how their backstory guides their goals, motivations and potential conflicts.

This is especially common in novels where a single, unforgettable event casts its shadow over the rest of the book (e.g. the murder in a murder mystery).

Framing an event in your story through a character’s memory gives it weight. It’s also a crucial part of character development. When you begin your novel with your main character remembering an earlier scene, it’s thus important to choose the right scene. As novel writing coach Romy Sommer says:

An issue I see with a lot of beginner writers is they tend to write the backstory as the story itself… that backstory is usually you as the writer writing it for yourself so you can understand the characters. ‘Understanding Character Arcs: How to create characters’, webinar preview here.

Consider that you might be describing too much of a character’s everyday life. While some details are good, remember that doing so should also serve the story, but not bog it it down in too many details.

Choose a scene that shows a dilemma or choice, or a powerfully emotional experience that is bound to have consequences for your character.

For example, Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time opens with the 15-year-old narrator Christopher finding his neighbour’s murdered dog:

It was 7 minutes after midnight. The dog was lying on the grass in the middle of the lawn in front of Mrs Shears’ house. Its eyes were closed. It looked as if it was running on its side, the way dogs run when they think they’re chasing a cat in a dream. But the dog was not running or asleep. The dog was dead. There was a garden fork sticking out of the dog. Mark Haddon, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time (2003)

Haddon’s opening is effective because it builds up to the revelation that the dog was killed violently. It’s effective because it raises questions we want answered.

When you begin with your narrator recalling a key memory, remember to:

- Choose a scene that immediately starts giving the reader keys to understanding: Haddon’s narrator proceeds to hug the bleeding dog, for example, so that we start to realise that Christopher is unusual in some way.

- Show the reader the memory: Haddon does not just say ‘Christopher found his neighbour’s dog, killed with a garden fork.’ We discover the dog through Christopher’s eyes, and this increases the scene’s impact.

Make a Strong Start to your Book

Join Kickstart your Novel and get professional feedback on your first three chapters and story synopsis, plus workbooks and videos.

A little bit of mystery or confusion at the start of your novel can help to reel readers in.

At the same time, make sure your opening isn’t so mystifying that the reader bails in frustration.

Even if the purpose or reasons for your ambiguous opening aren’t clear at first, the action itself must sustain readers’ interest until there is more clarity.

Consider the opening of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 :

It was a pleasure to burn. It was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venemous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history.’ Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451 (1953)

The first sentence is ambiguous – who, or what, is burning? The next slowly fills in context: We learn a character is using kerosene to burn something, to destroy ‘history’, but we still don’t know what exactly. We only learn by the end of the paragraph that the character Montag is burning books.

This way of beginning a story is effective because Bradbury prolongs a mixture of suspense and confusion, yet the character’s action itself is clear.

If you begin a book with ambiguous, teasing action:

- Give the reader answers to at least one (or some) of the ‘5 w’s’. We might not immediately know who is doing the burning (or what they’re burning), but Bradbury gives us a strong why : Pleasure. The relish with which Montag burns the books is clear

- By the end of the first paragraph, give the reader a little more clarity, as Bradbury does

‘Prologue’ literally means the ‘before word’. This separate introductory or prefatory section in a novel has several uses:

- Giving broad historical context that paves the way for the main story

- Showing a scene or event preceding the main narrative, whose consequences ripple through the following story

Donna Tartt uses the second type of prologue to excellent effect in her mystery novel The Secret History . Her prologue tells us that a character is murdered, that the narrator is somehow complicit, and that he will narrate the events that led up to the murder in the coming narrative.

This teaser makes it clear that motive, rather than identity, is the main mystery behind the killing.

Tartt’s prologue wastes no time in revealing key information that shapes our expectations for the main story:

The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation. He’d been dead for ten days before they found him, you know. Donna Tartt, The Secret History (1992).

By immediately framing the story around Bunny’s murder and its aftermath, Tartt’s prologue directs our attention to the ground the coming story will cover. Not the fact of Bunny’s death but the swirl of events that spin out from this crime. It marks out a path into reading and making sense of the story.

Do you want to include a prologue in your book ? Ask:

Do the events in the first part of your book need telling explaining prior events?

If yes, why?

In Tartt’s case, giving away key events in the prologue is smart, structurally. Because the identity of the murder victim (and at least one person responsible) is revealed early, the main narrative of the story is free to focus on character motivations and consequences and not just crime-solving.

Would your story flow better if you told earlier events via character flashbacks or a prologue?

Try writing a scene as a prologue, then write the same scene as a flashback. Which fits the scene better?

If you’re unsure how to start your novel, our writing coaches will help you get on track.

The most memorable story openings surprise us and make us pause for a moment.

Take Bradbury’s beginning to Fahrenheit 451 above, ‘It was a pleasure to burn.’ It’s unexpected.

This is partially because of its inner contradiction. We know that getting a burn from a hot plate is painful, and the idea of pleasure is thus surprising.

The ambiguity of ‘it’ means we don’t know initially whether the narrator is describing an odd pleasure in burning himself or burning something else.

Examples from famous books reveal this has always been one of the popular ways to start a story. For example, Dodie Smith opens I Capture the Castle (1949):

‘I write this sitting in the kitchen sink.’

The narrator Cassandra’s choice of sitting place is unusual, intriguing us to read the next sentence. Whichever way you choose to begin your novel, getting the reader to read the second sentence is the first, crucial feat.

Start your own novel now: brainstorm story themes, settings and characters and get helpful feedback from the Now Novel community.

Related Posts:

- How to start a fantasy story: 6 intriguing ways

- Writing a story from beginning to end: How to take…

- How to start a scene: 5 ways to reel readers in

- Tags ways to start a story. story beginnings

Jordan is a writer, editor, community manager and product developer. He received his BA Honours in English Literature and his undergraduate in English Literature and Music from the University of Cape Town.

46 replies on “5 ways to start a story: Choosing a bold beginning”

I feel you have made some excellent choices to illustrate the point of today’s lesson. Each extract is a finely crafted piece of flash fiction as it stands.

Glad you enjoyed the choices, Bob (and thanks for sharing on Twitter).

looking for a way to start my Wattpad story besides starting it with dialougue

Thank you for reading the blog 🙂

This is really interesting thanks <3

It’s a pleasure, Akane-chan, thanks for reading our blog!

Me, deciding how to start my story, brough me here. This gave an idea on how I would want start it. Thanks.

I’m glad to hear that, Daniel! It’s our pleasure, thanks for reading our articles. Good luck with your story.

How do I introduce a death flashback at the beginning of my story???

Hi Karthik, thank you for asking. If it’s a death flashback would that mean your viewpoint character is remembering their death from the afterlife? I’d suggest starting just before the event leading to their death so that the scene is already at a high point of tension. Good luck! We have some advice on writing flashbacks here: https://www.nownovel.com/blog/incorporate-flashbacks-into-a-story/

I’m writing a story where the female lead is posing as a male at this all boy’s school, where he missing father used to attend. I’m unsure if I should start with a history of the school, he family life and motives, a group of males figuring her out or a point in the story where said males already know of her true identity. Any tips?

Hi Eiseley, I would say starting with a high-stakes, high-tension moment (your protagonist’s identity being found out, for example) would be a good beginning – you can always circle back to how it is they came to be attending the school in disguise.

[…] http://www.education.com/lesson-plan/finding-the-moral/http://www.mensaforkids.org/teach/lesson-plans/the-art-of-storytelling/http://www.literacyideas.com/latest/2018/2/3/5-fun-ways-to-use-fables-in-your-literacy-lessonshttp://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/kids-storieshttps://www.nownovel.com/blog/ways-to-start-story-examples/ […]

“it was too late “she sigh. the act was already done .. do not know how to start this short story and include this sentence

Hi Shebekie, you’re getting there! I’d suggest editing to: ‘It was too late. She sighed – the deed was already done.’ To continue it, you could tease out the mystery surrounding the nature of the character’s deed further. For example, you could imply potential consequences (e.g. ‘Now she’d have to tell the others’).

Hi I’m trying to find out how to correctly start my sorry without boring the audience. The story is about a teenage boy transferring to a new high school which he finds a girl that is unloving and careless so he’s trying to win her heart over and prove that she can truly be loved.

Hi Darhnell, thank you for sharing that. I would say you have a good starting point in your MC transferring to a new high school, as that’s a situation that would likely be full of surprise, change, trepidation, anxiety, new friends (or new foes), etc. So showing the first time your character enters the new school, for example, or how he feels in the lead-up to arrival, would be one way to start.

Or you could start in medias res (in the middle of the action) with a significant moment during his first day at the new school. For example, his first interaction with the girl, circling back to how he got there later in the chapter. These are just some ideas. I hope this helps!

Hi, nice tips. I was wondering how to start a short story for 2 boys named Luke and Max stranded in their canoes. They were set on a research expedition on the animals in Antarctica but they got lost and couldn’t find anything. They are trying to head home by following the North star so they could reach their lab in Argentina. Pls, help me start. I was going with the idea of saying. “It was 7 minutes after midnight in Antarctica. The water swayed from ice-burg to ice-burg leaving a sparkling coat. Luke and Max were vigorously paddling their canoes towards the north start hoping at any moment they could get back to their warm and cpzy lab back in Argentina”

Hi Bob, thank you for the feedback and for sharing your idea. Not being much of an astronomer myself I had to check regarding Polaris (the North Star) and apparently it is only visible under certain conditions south of the equator, so perhaps they’d need another navigational technique. A compass, perhaps?

If it is after midnight and they are that far south, hypothermia would be a major risk, so perhaps the boys don’t get that far south to begin with? You can of course bend the rules of physics and geography in fiction if you want to tell a fantastical story. There are a few typos (‘ice-burg’ for ‘iceberg’, ‘start’ for ‘star’ and so forth) but other than that it is a suspenseful situation for an opening. Some readers may question the science behind some of the details mentioned though.

Beginning in the middle of the action is interesting, just make sure the exposition of the story continues to explain why the boys are there in the first place. I hope this is helpful!

Wow so good ways to start a story

Thank you, Priyank. Good luck with your own!

im writing a creative story about an orphan girl and im trying to craete the story but i need help any chance you would help me

Hi Ivokjuca, happily! What do you need help with? Please feel free to mail us at [email protected] too with your challenge.

Thank you very much for the tips… i was wondering how to start my story which i am writing about an incident of my life which is a complete secret to date. i hope this will help me start my piece

Hi Rashmi, it’s a pleasure! Good luck with starting your story and developing it further.

Thank you very much for the tips. it is really very helpful for me. Keep Sharing.

Thank you for your feedback, Anu! We will do so.

[…] https://www.nownovel.com/blog/ways-to-start-story-examples/ […]

Thanks a lot for this. It helped me a lot.

It’s a pleasure, thank you for reading our articles.

Hi there! I am a young writer (13 to be exact), and I am brainstorming for a way to start my first novel. Can you perhaps give me some inspiration? My novel is about three teenagers: Claire Minch, Samuel Ploy, and Sheila Crover. They live on a technologically advanced planet called Gyn, where the whole world’s population receives warnings from their future selves, or so they thought. In the end, I want it to state that instead of being warned by their future selves, the warnings are given by a Krewd (Demon) who has been leading them down the wrong path all along. Please give me some advice. I have been all over the internet, bt nothing really sparked my imagination for the start of my novel.

Hi Anani, thank you for sharing that (it’s great you’re working hard on your writing by the way).

It’s an interesting idea. Given the interesting warning system you described, starting with one of the warnings could be one way to go. How are the warnings broadcast, and is there a schedule (e.g. do they know when the warnings are going to come, do they each get their warnings at the same time, and is it transmitted via tech or something they just hear?).

Keep asking questions, as you will know best what to choose. Are you looking for inspiration for any particular character or part of the story?

I hope the questions I asked help!

It’s always good to read and learn about stories

That it is, Mark 🙂 Thanks for reading our blog.

I am trying to write a thriller and romantic story pls help me

Hi Nish, with pleasure. What aspect of the story would you like help with? Do you have a firm story idea developed already? What about it is giving you trouble? You can find all our articles on writing romantic stories here .

This tips were quite helpful. Though, I still have a few holes on how to start my story.

Thank you for sharing that, Georgina. What are there holes around? You might find this article on how to avoid plot holes helpful.

As a student and teacher of English, I had to read, write and teach a number of stories. I learnt about the essential plot parts, techniques, character-development and so on. The problem with me, while writing my own stories, I forgot mostly what I had learnt about story writing. I thought I was writing some really interesting stories though. I started sending my stories to online, offline magazines, started participating in Flash Fiction Contests where I had my fellow writers commenting on my stories. I felt that I could consider myself to be a competent writer. But aren’t competent, capable writers supposed to have name and fame? Aren’t they supposed to be rich? Even after having written over 500 short stories, forget about being rich, I wasn’t even earning a penny? If I don’t get published, if I don’t get paid by writing, am I going to die an unfulfilled writer? These questions have become paramount in my mind lately. In my early 60s, I am not sure any more if writing is the thing for someone like me with very little economic freedom. Writing is reaching a point in my retired life when it is not sheer fun anymore. My question to you is, would you still advise me to continue writing? Do you still think that there is a flicker of light at the end of the tunnel? Stay blessed.

Hi Rathin, thank you for sharing this personal account of your writing path. I would say it depends on your aims. To make money from writing, it is crucial to approach it as a business and do careful market research, invest time in marketing your work, and use every available resource (social media, Amazon author pages (if you’re listing work there), Goodreads, and other places such as book fairs to build an audience interested in what you have to say.

This being said, writing is lucrative for very few writers and many support their writing with side hustles. Fame and riches are goals beyond one’s immediate control, there being so many variable factors involved in earning them, so I would always advocate writing for passion and the pleasure of creation and communication above money or fame.

It is challenging to have ‘very little economic freedom’ as you describe, as that makes writing more of a luxury if it isn’t contributing income. Approaching it as a pleasure and an escape into creation rather than putting financial pressure on the process may be best for keeping the joy of it alive, though (one can do commercial writing such as copywriting for money as it tends to pay better per hours invested). I hope this is helpful, it is of course a highly subjective perspective.

This was so helpfull. And i think i know how i can start my story! But how will i switch from a prologue to a chapter

Hi Cliffton, thank you for sharing your kind feedback. I’m glad you have an idea about how you want to start your story. That’s a broad question, what information do you plan to share in your prologue? Many effective prologues do a little worldbuilding while creating a little curiosity, then the first chapter picks up with immediate, scene-level action or a character’s voice (the prologue giving more of a general sense of a situation, place or mood). There are so many ways to use a prologue – the main thing is to make it as interesting and curiosity rousing as chapter 1. Here’s something I wrote on prologues you may find useful.

Thanks for this useful tips.

Thanks George, glad you found them useful.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Pin It on Pinterest

Writer's Edit

A newsletter for novel writers looking for inspiration and advice on their creative journey.

15 Awesome Ideas To Get Your Story Started (With Examples)

There are many great ways to start a story .

Depending on the genre, you might begin mysteriously and gradually build to a climax. Or you might start with an image or description to orient the reader in the story’s setting.

Whatever you choose, it needs to engage your reader immediately and encourage them to keep turning pages.

Let’s take a look at some exciting ways to start a story. Who knows? You may become inspired to write the next bestseller!

Before You Start Writing

Most of the time, you need to have an idea of your key story elements before you can write the opening lines.

To avoid wasting time or writing yourself into a corner, it’s wise to have at least a rough idea of what your characters are like and what the plot will involve.

Sound plot and character development are essential in every story, so try to have their foundations in place before you begin.

Know Your Characters

Try to get to know your characters a little before you start writing.

Who is your main character (or characters)? What will they accomplish during the novel? How might they grow and change throughout the story?

Who are the supporting characters? How will they contribute to the story?

When you know who your characters are, you’ll have a better idea of how you want to begin (and continue) the story.

Plan Your Plot

A good novel also has an interesting, well-paced, believable plot.

Whether you’re a plotter, a pantser or somewhere in between, you need to have at least some idea of what your plot will entail before you dive in to write.

You also need to be ready to move the plot along quickly through your opening sequence, or your reader will not be interested in continuing with your book.

Think of any good movie or TV show that jumps right into the plot before the opening credits roll. A lead-in scene often throws viewers directly into the story by creating mystery or questions.

Without an idea of the overarching plot, you’ll find it hard to come up with such a compelling opening scene.

Idea #1: Create a Hook

A great way to start a story is to draw the reader in with a hook – something that will create intrigue.

‘I’ve often wondered what happened to Steve – did he find the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow?’

Now you’re wondering what happened to Steve as well, and you want to know why he thought he could find that elusive pot of gold.

You’re also wondering what happened before the above musing, and how it all started.

Beginning your novel with a hook encourages the reader to keep reading , if only to find the answers to the questions the first sentence created.

Idea #2: Start with Dialogue

You might have seen advice about never starting a novel with a dialogue opening. But in certain cases it works, such as when you want to introduce a character quickly without a lot of explanation.

‘”Mistakes are a part of life,” she told me, “but what you did this time is inexcusable!”‘

Dialogue at the beginning of a novel can potentially confuse the reader, as the characters are not yet known, nor is the situation.

But this particular dialogue shows readers that the story starts in a place of conflict , inviting them to read on to find out how a simple mistake went too far.

Dialogue that introduces your plot without explanation can entice your reader to discover the story behind it.

Idea #3: Ask a Question

Questions are a great way to open a novel, especially when the answer (and the story that follows) could go in many different directions.

A questioning beginning has the effect of appealing directly to the reader. If they want to find out more, they have no choice but to read on.

‘What would you do if you knew the exact moment you would die?’

The story that comes after such a question is bound to contain surprising twists and turns.

Dealing with a universal subject such as death , it also suggests that the story will take the reader on an emotional roller coaster until the end.

Idea #4: Write Something Unexpected

‘I never knew the impact of the purple pen until it exploded in my face.’

Starting your novel with an unexpected statement takes your reader off guard and makes them wonder how your character got to this point.

The unexpected can create a sense of mystery and suspense . It can also subvert readers’ expectations.

Think about how people might expect the story to start, then surprise them by taking it in another direction entirely.

Once you have them in your grasp with the unexpected, they’ll be more invested in continuing the story.

Idea #5: Begin with an Action Sequence

Action creates excitement and propels your novel forward. Starting with an action scene can be dangerous, though, as you might leave yourself nowhere to go.

You don’t want to have a big action scene at the beginning that overshadows the rest of the story.

An action sequence should lead to the story, but not take away from the big showdown later.

‘Her heart in her throat, she sat in the car, watching the men frantically searching for a way in. She fumbled with a phone hastily sending a one-word text to her husband: HELP .’

This kind of opening sets the scene and creates a future segue into more significant action.

When the woman’s husband comes out, he will inevitably have a showdown with the men harassing the woman. But why are they in that situation? How will they get out of it? What other action scenes will happen?

Start small, build suspense and add more action as you get closer to the showdown.

Idea #6: One-Word Sentences

‘Run.’

A one-word sentence like this piece of dialogue will send chills down most people’s spines and implies so much with a single word. Who is running, and why?

The sentence creates mystery and intrigue. You don’t know why someone is telling another person to run.

Are authorities working to uncover a crime syndicate? Is someone coming to kill the main character?

It sets up an intense scene that propels the reader forward.

Idea #7: Start with Something Unusual

A random or unusual opening immediately catches a reader’s attention, setting your writing and story apart as something unique .

‘The light did not flicker; she did.’

This opening makes you do a double-take. ‘What does that mean?’ you wonder.

It’s the beginning of what promises to be an unusual story, making your reader take note and read on to find out what you meant.

It could be the beginning of a supernatural story where a girl disappears and reappears every time a light switch is flicked. Or it could just be a metaphor.

No one knows until they read further. An ambiguous opening has so many possibilities.

But remember: unusual turns of phrase throughout a book can be confusing to the reader, so don’t overdo the experimental language.

Idea #8: Write an Intense Opening

Intense doesn’t mean you have to start with something showy or spectacular, like a car going off a cliff in a fiery explosion.

Rather than beginning the story in the thick of the action, you can start in the aftermath. Think of a smoldering fire that is barely burning, but still red-hot.

“Ashes rained from the sky for days. Not a single sign of vegetation remained, and we were hungry – no, starving for any morsel of food.”

This opening to what might be a firsthand account of surviving a volcanic eruption is intense enough to propel readers to find out more.

It describes the consequences of what has happened rather than the event itself, leading into what promises to be a compelling post-apocalyptic narrative.

Idea #9: Establish a Genre-Appropriate Atmosphere

The opening of a novel should create the atmosphere you want for your readers .

“The moment we stepped into the room, the putrid smell of death assaulted our senses.”

Immediately, you know that something terrible has happened, and what follows will most likely involve bone-chilling horror or intriguing mystery.

Or perhaps you’re writing an adventure novel, and need to evoke the thrills and dangers of seeking hidden treasure in your first sentence:

“As we entered what we thought was the treasure chamber, we discovered that we had been given the wrong map.”

The above begs several questions: who gave them the wrong map and why? What treasure were they seeking, and where have they found themselves instead?

Idea #10: Start in the Middle of a Scene

Many good stories start in the middle of the scene for a good reason: it generates momentum right from the start, so you don’t lose your reader before the conflict begins.

“Police cars barricaded the street. Ambulances and fire trucks raced to the scene. The house was surrounded, and yet… nothing. No communication. No one knew if the hostages were alive or dead.”

Starting in the middle of a scene drops readers right into the exciting part, giving them questions they want to read on to answer.

Readers want to know who is being held hostage, who is holding them, why they aren’t communicating, and how the situation will be resolved.

Rather than starting with a long lead-up to this key scene, readers get to delve right in, gleaning details along the way.

Idea #11: Disorient the Reader

Another great way to start a story is to disorient your readers. Throw them off-balance and make them re-read the opening lines more than once.

A great example is from George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four :

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.”

The clocks striking thirteen creates a sense of something not quite right, suggesting to readers that an intriguing world unlike our own lies beyond this first sentence.

To add further impact, introduce plot twists later in the story that make readers reevaluate the book’s opening words.

They’ll return to that section in amazement to understand what just happened and how their expectations were subverted.

Idea #12: Mysterious Beginnings

There’s nothing better to start a novel than with a puzzle for your readers to solve.

Starting with a mysterious beginning or an unanswered question gives readers a chance to mull it over and meditate on it before it’s answered later in your novel.

“The door was never opened, yet everything was out of place. Someone had been here, but who?”

The above example raises all the important questions: Who, What, Where, When, and Why (plus the bonus question: How). You’ll have the rest of the novel to delve into the answers.

Who went into the house? What were they looking for? How did they get in if the door was never opened?

The underlying feeling of a mysterious opening sequence is tension and foreboding, which lends itself particularly well to a crime novel or a murder mystery .

Idea #13: Prologue with Purpose

Often, starting a novel with an explanation or precursor to the main events can discourage your audience.

But if you do it right, writing a prologue can create suspense that keeps your audience’s attention.

For example, if you start with a chase scene where the protagonist searches for a hidden doorway but is murdered before he finds it, you’ve placed the driving force of your story in centre stage.

The most common prologues provide context for the main story through a past event. Once this is in place, you are free to flesh out the story, exploring why it happened and its consequences.

Idea #14: A Startling Start

Starting your story with a dangerous element, like many opening scenes in James Bond movies, can startle the reader into continuing.

“As soon as she sat down in his car, she knew she made a disastrous mistake.”