Organizational Change Process: Toyota Motor Case Study

Introduction.

Currently, the car industry is undergoing a major shift in priorities: if earlier, the main stakeholders of a company were rather concerned with stability and profit, nowadays, predictable earnings growth does not suffice. Car building has grown an overwhelmingly competitive sector where innovation reigns supreme. A Japanese multinational company headquartered in Tokyo, Toyota seems to be excelling in both sales numbers and putting forward innovative ideas and projects. On the one hand, the world’s second-largest car manufacturer has succeeded in striking a balance between meeting customers’ needs and making them interested in purchasing new models.

For instance, Toyota has produced and introduced the world’s first and best-sold hybrid car, Prius, successfully. Furthermore, year after year, the Japanese manufacturer ranks among the most innovative companies for its thoughtful consideration of fuel efficiency and safety standards. On the other hand, some experts are convinced that the company might be on its way to long stagnation due to its rigid bureaucratic structure. This essay will discuss what an organizational change consultant could suggest Toyota do regarding making meaningful changes and reinventing itself.

Planned Change

Lewin’s planned change model.

When a company considers changing its course of action, managers and OD consultants may entertain the idea of applying Lewin’s planned change model. Nothing is as compelling and motivating as soaring sales statistics. In 2018, alongside other large Japanese car manufacturers, Toyota saw a substantial decrease in sales numbers: for instance, there was an 18.6% decline in Camrys sales (Bomey, 2018).

All points are taken into consideration, one may conclude that Toyota cannot and should not rely on its reputation as the main driving force behind sales. Instead, launching a change model might be more preferable, which provides a clear rationale for Lewin’s Planned change model.

Lewin’s planned change model implementation usually takes three steps. At the first stage, a company needs to do a so-called defreezing in which it makes major changes to the prevailing paradigm and vision among all corporate levels (Hussain et al., 2018).

In the case of Toyota, both the managing board and employees should realize that fixing faulty features and avoiding recalls is a short-term solution. Once decision-makers have found a long-term solution, they introduce a change, which constitutes the second stage. Lastly, if the outcome is positive, a company should proceed with refreezing, stabilizing the structure, and making meaningful patterns for future action.

Action Research Model

Akin to the planned change model, the implementation of the action research model consists of three stages. The action research model goes into detail as to how an organizational change consultant should interact with a company that hired him or her to make the collaboration mutually beneficial. The first stage is communication, during which the clients share what they find troublesome about the company at the moment, and the consultant provides feedback (Willis & Edwards, 2014). The end goal of the first stage is to define causal relations between a company’s past decisions and current challenges. For instance, in the case of Toyota, an organization development consultant could examine how new design solutions or lack thereof affected sales numbers.

The next step would be data collection and problem diagnosis by the consultant. The findings of the second stage would determine objectives and, hence, the action plan. An essential subpart of the second stage is defining what action behaviors would be most effective in achieving the set goals (Willis & Edwards, 2014). Lastly, an OD consultant would do further research on the outcomes and gather data to decide whether the right course of action was taken.

It is imperative to maintain continuous two-way communication with the client and react to his or her feedback promptly. If a company and an OD consultant aim at long-term cooperation, the data gathered at all stages will help to make a new plan. Long-term cooperation would be preferable in the case of Toyota since such large companies need more time to make incremental changes.

Collecting Data

If a company wishes to elaborate a workable organizational development plan, it is imperative to gather and evaluate both qualitative and quantitative data for assessment. Furthermore, one needs to outline the advantages and disadvantages of the chosen research methodology. One of the most popular methods to collect data is conducting a survey among employees (Transparency International, 2014).

One of the pressing issues a survey could target could be the turnover rate at Toyota (Glassdoor, 2019). A high turnover rate leads to the necessity to train new employees while those who quit prematurely did not unlock their potential fully (Oladele, 2016). One may contend that Toyota owes its success to inbred leadership, in which managers are promoted within the company.

The data drawn from the first survey could be further processed using statistical methods to put together a clear picture of employees’ satisfaction in the workplace. A cross-sectional survey is a good method of assessing a situation in a given time span. However, it is important to evaluate the findings critically as they might be susceptible to voluntary basis: the most troubled and dissatisfied employees are more likely to come forward. At the same time, since participation would not be mandatory, a 100% outreach would not be possible, and thus, some of the voices would not be heard.

Another essential survey would take place among the top management of Toyota. In alignment with the action research model, an OD consultant would have to draw an extensive body of data from the company’s key figures. The second cross-sectional survey would aim at defining the company’s prevailing paradigm to establish what could be changed to guide Toyota on the way to innovation.

What an OD consultant would seek to attain through the series of such insightful interviews is to define what innovation means in the context of Toyota Company. Analyzing qualitative data of such kind would involve seeking similarities in responses to expose patterns. By doing that, it would be possible to seek customized solutions, which is not readily workable if a company uses a broad nebulous notion.

One of the responsibilities of the OD consultant at this stage would be to develop questions for participants. The first survey conducted by an OD consultant would be on the intention behind the high turnover rate. A study by Cohen, Black, and Goodman (2016) showed that a turnover intention rate is not a good predictor of an actual turnover rate. The questionnaire could contain yes/ no questions or Likert-scale statements in which the respondents would have to reply to what extent they agree with the statements provided.

For instance, “I feel valued and affirmed at work” or “I’m engaged in meaningful work (Society for Human Resource Management, 2016).” Thus, the survey would not include questions as to whether an employee plans to resign but rather whether he or she is satisfied with their work conditions and overall environment.

As for the second survey, an OD consultant could conduct a series of in-depth interviews to gather qualitative data about the managers’ shared and personal views. Based on a report by Coad et al. (2014), an OD consultant could develop an array of open-end questions. For example, “What is innovation?”, “Do you consider Toyota an innovative company?”, or “How do you see the company’s growth and development in the next five years?” What could also be useful is encouraging managers to reflect on the failures of the year 2009 since it had a rather difficult psychological effect on Toyota.

Feeding Back Diagnostic Data

Force-field analysis.

Lewin’s force-field analysis is a simplistic at first glance yet a profound strategy for determining primary contributing factors to the company’s growth or decline. According to Lewin, there are two categories of factors: driving forces and resisting forces (McGrath & Bates, 2017). One of the main difficulties emphasized by McGrath and Bates (2017) is that some factors may be both driving and resisting forces. That is why it is imperative to gather data to put each factor in context. In the case of Toyota, the force field may look as follows (see table 1).

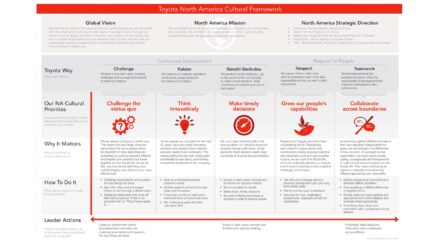

Organizational Culture

Assuming that the company aims at making a major change, the OD consultant should find the most effective ways to present what he or she discovered. Due to the great number of employees – more than 369,000 (Statista, 2018), it is impossible to communicate the highlights of the diagnosis personally. To solve the issue, distribution and communication could be delegated to the managers of each department.

When possible, it would be best to organize discussion groups where information would not be presented in the form of a lecture but a conversation. The ability to contribute encourages people to memorize and take action. As for the main points to be presented, it is crucial that an OD consultant employs objective, numerical data as well as summarizes the managers’ views on innovation.

Organizational Change Interventions

Action plan – short-term.

As for the actions that the company could take on an immediate basis, a short-term plan for Toyota would include practices that would directly address the issues exposed in the survey findings. For instance, once employee engagement and motivation are examined, human resource development specialists could start working on the most pressing problems. Since ethical implications would be taken into consideration, the survey would be fully anonymous.

This means that HRD specialists would not be able to approach specific employees to have a conversation about their challenges and intentions. Instead, the company could address the factors defined in the findings directly. For instance, if it is subpar working conditions in particular quarters that were found to be demotivating, they should be improved. As for further fostering engagement and innovation, HRD specialists could hold brainstorming sessions within general employee meetings, starting shortly after the data has been analyzed. In the meetings, employees could put forward their ideas as to how the company could be changed in a meaningful way (Dawson & Adriopoulous, 2017).

Further, the managers’ views should be consolidated and summarized in the form of a clear mission statement with a short-term and long-term objective. The statement should be published within the company as well as posted online on the official website and other social media resources of the company.

Action Plan – Long-term

The question arises as to what measures the company could take to aid its development in the long perspective. It is obvious that the company needs a continuous assessment of employees’ needs. For this reason, it is only reasonable to conduct subsequent surveys to detect other problems that might be discouraging employees from releasing their full potential. Thus, Toyota would handle the issue of the high turnover rate in several steps.

Overall, it is crucial to foster an atmosphere in which supervisors do not judge new ideas, and constructive criticism is welcome. One of the long-term methods of supporting innovation at the company level could be holding technology startup contests. Since Toyota is a large company, it has enough resources at its disposal to fund the best ideas aimed at sustainability, safety, and fuel efficiency. As for further development of the mission statement, once managers have singled out particular objectives, they need to diagnose each of them.

Toyota is a company with a long, rich history that has been a trailblazer in the car manufacturing industry and set bars for other companies for many years. As of now, despite formal achievements, such as growing yearly revenues, some experts claim that the company is becoming increasingly stagnant. The situation is calling for a thoughtful diagnosis and assessment, which can be conducted by an organizational development consultant.

It is crucial to implement one of the existent strategies such as planned change or action research models. A series of surveys should be carried out and gathered data should help to elaborate an action plan. While choosing the course of action, Toyota should take into account such driving forces as rich resources, loyal customer base, and experience in launching innovative projects. On the other hand, customers reluctant to changes, recent controversies such as massive recalls, and training staff should not be dismissed.

Bomey, N. (2018). Honda, Toyota, Nissan car sales plunge, but SUVs rise U.S. auto sales likely up in August . USA Today. Web.

Coad, A., Cowling, M., Nightingale, P., Pellegrino, G., Savona, M., & Siepel, J. (2014). Innovative firms and growth: UK Innovation Survey . Web.

Cohen, G., Blake, R. S., & Goodman, D. (2016). Does turnover intention matter? Evaluating the usefulness of turnover intention rate as a predictor of actual turnover rate. Review of Public Personnel Administration , 36 (3), 240-263.

Dawson, P., & Andriopoulous, C. (2017). Managing change, creativity, and organisation (3d ed.). New York City, NY: SAGE.

Glassdoor. (2019). Toyota North America. Web.

Hussain, S. T., Lei, S., Akram, T., Haider, M. J., Hussain, S. H., & Ali, M. (2018). Kurt Lewin’s change model: A critical review of the role of leadership and employee involvement in organizational change. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge , 3 (3), 123-127.

McGrath, J., & Bates, B. (2017). The little book of big management theories:… And how to use them. Pearson, UK: Business & Economics.

Oladele, J. A. (2016). Labour turnover: Causes, consequences, and prevention. Fountain University Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 5 (1), 105-112.

Shannon, J. (2019). Toyota recalls 1.7 million more vehicles for risk of shrapnel from exploding airbags . USA Today. Web.

Society for Human Resource Management. (2016). Employee job satisfaction and engagement. Revitalizing a changing workforce . Web.

Statista. (2018). Consolidated number of Toyota Motor Corporation employees from FY 2012 to FY 2018 . Web.

Toyota Global. (2018). Financial highlights . Web.

Transparency International. (2014). Transparency in corporate reporting. Assessing the world’s largest companies. Web.

Willis, J. W., & Edwards, C. (2014). Action research: Models, methods, and examples. Charlotte, NC: Education.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, June 25). Organizational Change Process: Toyota Motor. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-case-of-toyota-organizational-change/

"Organizational Change Process: Toyota Motor." IvyPanda , 25 June 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/the-case-of-toyota-organizational-change/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Organizational Change Process: Toyota Motor'. 25 June.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Organizational Change Process: Toyota Motor." June 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-case-of-toyota-organizational-change/.

1. IvyPanda . "Organizational Change Process: Toyota Motor." June 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-case-of-toyota-organizational-change/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Organizational Change Process: Toyota Motor." June 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-case-of-toyota-organizational-change/.

- Grunewald’s OD for Execution of Strategic Change

- Organizational Development Consultants in Business

- Organizational Development Practitioner: Roles and Style

- Choice Hotels International and Lewin's Change Model

- Articles on the Future of Organizational Design

- Quay International Convention Centre's Organizational Development

- Organizational Development of The Exley Chemical Company, The OD Letters, The Sundale Club

- OD Application: Harley-Davidson's Plant Run by Work Teams

- Organisation Development Initiative: West Bravenhurst NHS Trust

- “Applying Organization Development Tools in Scenario Planning” by T.Marshall

- Apple Production Operation Process

- Organization Design and Development

- Business Environment and Organizational Activities

- Organizational Behavior Issues in the US and the UAE

- Effective Organizational Change in Education

Resilience Tested: Toyota Crisis Management Case Study

Crisis management is organization’s ability to navigate through challenging times.

The renowned Japanese automaker Toyota faced such challenge which shook the automotive industry and put a dent in the previously pristine reputation of the brand.

The Toyota crisis, characterized by sudden acceleration issues in some of its vehicles, serves as a compelling case study for examining the importance of effective crisis management.

Toyota crisis management case study gives background of the crisis, analyze Toyota’s initial response, explore their crisis management strategy, evaluate its effectiveness, and draw valuable lessons from this pivotal event.

By understanding how Toyota tackled this crisis, we can glean insights that will help organizations better prepare for and respond to similar challenges in the future.

Let’s start reading

Brief history of Toyota as a company

Toyota, one of the world’s largest automobile manufacturers, has a rich history that spans over eight decades. The company was founded by Kiichiro Toyoda in 1937 as a spinoff of his father’s textile machinery business.

Initially, Toyota focused on producing automatic looms, but Kiichiro had a vision to expand into the automotive industry. Inspired by a trip to the United States and Europe, he saw the potential for automobiles to transform society and decided to steer the company in that direction.

In 1936, Toyota built its first prototype car, the A1, and in 1937, they officially established the Toyota Motor Corporation. The company faced numerous challenges in its early years, including the disruption caused by World War II, which halted production.

However, Toyota persisted and resumed operations after the war, embarking on a journey that would eventually lead to global recognition.

Toyota’s breakthrough came in the 1960s with the introduction of the compact and affordable Toyota Corolla, which quickly gained popularity worldwide. This success laid the foundation for Toyota’s reputation for producing reliable, fuel-efficient, and high-quality vehicles.

Throughout the following decades, Toyota expanded its product lineup, launching models like the Camry, Prius (the world’s first mass-produced hybrid car), and the Land Cruiser, among others.

Toyota’s commitment to continuous improvement and efficiency led to the development and implementation of the Toyota Production System (TPS), often referred to as “lean manufacturing.” TPS revolutionized the automotive industry by minimizing waste, improving productivity, and enhancing quality.

Over the years, Toyota successfully implemented many change initiatives.

By the turn of the 21st century, Toyota had firmly established itself as a global automotive powerhouse, consistently ranking among the top automakers in terms of sales volume.

However, the company would soon face a significant challenge in the form of the sudden acceleration crisis, which tested Toyota’s crisis management capabilities and had far-reaching implications for the brand.

Description of the sudden acceleration crisis

The sudden acceleration crisis was a pivotal event in Toyota’s history, which unfolded in the late 2000s and early 2010s. It involved a series of incidents where Toyota vehicles experienced unintended acceleration, leading to accidents, injuries, and even fatalities. Reports emerged of vehicles accelerating uncontrollably, despite drivers attempting to apply the brakes or shift into neutral.

The crisis gained significant media attention and scrutiny , as it posed serious safety concerns for Toyota customers and raised questions about the company’s manufacturing processes and quality control. The issue affected a wide range of Toyota models, including popular ones such as the Camry, Corolla, and Prius.

Investigations revealed that the unintended acceleration was attributed to various factors. One prominent cause was a design flaw in the accelerator pedal assembly, where the pedals could become trapped or stuck in a partially depressed position. Additionally, electronic throttle control systems were also identified as potential contributors to the issue.

The sudden acceleration crisis had severe consequences for Toyota. It tarnished the company’s reputation for reliability and safety, and public trust in the brand was significantly eroded. Toyota faced a wave of lawsuits, regulatory investigations, and recalls, as it scrambled to address the issue and restore consumer confidence.

The crisis prompted Toyota to launch one of the largest recalls in automotive history, affecting millions of vehicles worldwide. The company took steps to redesign and replace the faulty accelerator pedals and improve the electronic throttle control systems to prevent future incidents. Toyota also faced criticism for its initial response, with accusations of a lack of transparency and timely communication with the public.

The sudden acceleration crisis served as a wake-up call for Toyota, highlighting the importance of effective crisis management and the need for proactive measures to address safety concerns promptly.

Toyota crisis management case study helps us to understand how company’s respond to this crisis and set a precedent for handling future challenges in the years to come.

Timeline of events leading up to the crisis

To understand the timeline of events leading up to the sudden acceleration crisis at Toyota, let’s explore the key milestones:

- Early 2000s: Reports of unintended acceleration incidents begin to surface, with some drivers claiming their Toyota vehicles experienced sudden and uncontrolled acceleration. These incidents, although relatively isolated, raised concerns among consumers.

- August 2009: A tragic incident occurs in California when a Lexus ES 350, a Toyota brand, accelerates uncontrollably, resulting in a high-speed crash that claims the lives of four people. The incident receives significant media attention, highlighting the potential dangers of unintended acceleration.

- September 2009: The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) launches an investigation into the sudden acceleration issue in Toyota vehicles. The probe focuses on floor mat entrapment as a possible cause.

- November 2009: Toyota announces a voluntary recall of approximately 4.2 million vehicles due to the risk of floor mat entrapment causing unintended acceleration. The recall affects several popular models, including the Camry and Prius.

- January 2010: Toyota expands the recall to an additional 2.3 million vehicles, citing concerns over sticking accelerator pedals. This brings the total number of recalled vehicles to nearly 6 million.

- February 2010: In a highly publicized event, Toyota halts sales of eight of its models affected by the accelerator pedal recall, causing a significant disruption to its production and sales.

- February 2010: The U.S. government launches a formal investigation into the safety issues related to unintended acceleration in Toyota vehicles. Congressional hearings are held, during which Toyota executives are questioned about the company’s handling of the crisis.

- April 2010: Toyota faces a $16.4 million fine from the NHTSA for failing to promptly notify the agency about the accelerator pedal defect, violating federal safety regulations.

- Late 2010 and 2011: Toyota faces a wave of lawsuits from affected customers seeking compensation for injuries, deaths, and vehicle damages caused by unintended acceleration incidents.

- 2012 onwards: Toyota continues to address the sudden acceleration crisis by implementing various measures, including improving quality control processes, enhancing communication with regulators and customers, and establishing an independent quality advisory panel.

Toyota’s initial denial and dismissal of the problem

During the early stages of the sudden acceleration crisis, one notable aspect was Toyota’s initial response, which involved a degree of denial and dismissal of the problem. This response contributed to the escalation of the crisis and further eroded public trust in the company. Let’s delve into Toyota’s initial reaction to the issue:

- Downplaying the Problem: In the initial stages, Toyota downplayed the reports of unintended acceleration incidents, attributing them to driver error or mechanical issues. The company maintained that their vehicles were safe and reliable, asserting that the incidents were isolated and not indicative of a systemic problem.

- Lack of Transparency: Toyota faced criticism for its perceived lack of transparency regarding the issue. The company was accused of withholding information and failing to disclose potential safety risks to the public and regulatory agencies promptly. This lack of transparency fueled suspicions and raised questions about the company’s commitment to addressing the problem.

- Slow Response: Toyota’s response to the growing concerns regarding unintended acceleration was relatively slow, leading to accusations of negligence. Critics argued that the company should have acted more swiftly and decisively to investigate and address the issue before it escalated into a full-blown crisis.

- Reluctance to Acknowledge Defects: Initially, Toyota resisted the notion that there were inherent defects in their vehicles that could lead to unintended acceleration. The company’s reluctance to accept responsibility and acknowledge the problem further strained its relationship with consumers, regulators, and the media.

- Impact on Customer Trust: Toyota’s initial denial and dismissal of the problem had a significant impact on customer trust. As more incidents were reported and investigations progressed, customers began to question the integrity of the brand and its commitment to safety. This led to a decline in sales and a tarnishing of Toyota’s once-sterling reputation for reliability.

Lack of transparency and communication with the public

One critical aspect of Toyota’s initial response to the sudden acceleration crisis was the perceived lack of transparency and ineffective communication with the public. This deficiency in open and timely communication further intensified the crisis and eroded trust in the company. Let’s explore the key issues related to transparency and communication:

- Delayed Public Announcement: Toyota faced criticism for the delay in publicly acknowledging the safety concerns surrounding unintended acceleration. As reports of incidents surfaced and investigations commenced, there was a perception that Toyota withheld information and failed to promptly address the issue. This lack of transparency fueled public skepticism and eroded confidence in the company.

- Insufficient Explanation: When Toyota did address the sudden acceleration issue, their explanations and communications were often vague and lacking in detail. Customers and the public were left with unanswered questions and a sense that the company was not providing comprehensive information about the problem and its resolution.

- Ineffective Recall Communication: Toyota’s communication regarding the recalls linked to unintended acceleration was criticized for its inadequacy. Some customers reported confusion and frustration with the recall process, including unclear instructions and delays in obtaining necessary repairs. This lack of clarity and efficiency in communicating recall information further strained the company’s relationship with its customers.

- Limited Engagement with Stakeholders: Toyota’s engagement with key stakeholders, such as regulatory bodies, industry experts, and affected customers, was perceived as insufficient. The company’s communication efforts were criticized for being reactive rather than proactive, lacking a comprehensive plan to engage stakeholders and address their concerns promptly.

- Perception of Cover-up: The lack of transparency and ineffective communication led to a perception that Toyota was attempting to cover up the severity of the sudden acceleration issue. This perception further damaged the company’s credibility and fueled public skepticism about the company’s commitment to consumer safety.

Impact on the company’s reputation and customer trust

The sudden acceleration crisis had a profound impact on Toyota’s reputation and customer trust, which were previously regarded as key strengths of the company. Let’s explore the repercussions of the crisis on these crucial aspects:

- Reputation Damage: Toyota’s reputation as a manufacturer of reliable and safe vehicles took a significant hit due to the sudden acceleration crisis. The widespread media coverage of incidents and recalls associated with unintended acceleration eroded the perception of Toyota’s quality and reliability. The crisis challenged the long-standing perception of Toyota as a leader in automotive excellence.

- Loss of Customer Trust: The crisis shattered the trust that customers had placed in Toyota. The incidents of unintended acceleration and the subsequent recalls created doubts about the safety of Toyota vehicles. Customers who had been loyal to the brand for years felt betrayed and concerned about the potential risks associated with owning or purchasing a Toyota vehicle.

- Sales Decline: The erosion of customer trust and the negative publicity surrounding the sudden acceleration crisis resulted in a significant decline in sales for Toyota. Consumers were hesitant to buy Toyota vehicles, leading to a loss of market share. Competitors seized the opportunity to capitalize on Toyota’s weakened position and gain a foothold in the market.

- Legal Consequences: Toyota faced a wave of lawsuits from individuals and families affected by incidents related to unintended acceleration. These lawsuits not only had financial implications but also further damaged the company’s reputation as it faced allegations of negligence and failure to ensure the safety of its vehicles.

- Regulatory Scrutiny: The sudden acceleration crisis brought increased regulatory scrutiny upon Toyota. Government agencies, such as the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), conducted investigations into the issue, which further dented the company’s reputation. Toyota had to cooperate with regulatory bodies and demonstrate its commitment to rectifying the problems to restore trust.

- Long-Term Brand Perception: The sudden acceleration crisis left a lasting impression on how Toyota is perceived by consumers. Despite the company’s efforts to address the issue and improve safety measures, the crisis served as a reminder that even renowned brands can face significant challenges. It highlighted the importance of transparency, accountability, and a proactive approach to crisis management.

Recognition and acceptance of the crisis

In the face of mounting evidence and public scrutiny, Toyota eventually recognized and accepted the severity of the sudden acceleration crisis. The company’s acknowledgment of the crisis marked a significant turning point in their approach to addressing the issue. Let’s explore how Toyota recognized and accepted the crisis:

- Admitting the Problem: As the number of reported incidents increased and investigations progressed, Toyota eventually acknowledged that there was a problem with unintended acceleration in some of their vehicles. This admission was a crucial step towards recognizing the crisis and accepting the need for immediate action.

- Apology and Responsibility: Toyota’s top executives, including the company’s President at the time, issued public apologies for the safety issues and the negative impact on customers. The company took responsibility for the unintended acceleration problem, acknowledging that there were defects in their vehicles and accepting accountability for the consequences.

- Collaboration with Authorities: Toyota actively collaborated with regulatory bodies, such as the NHTSA, and other government agencies involved in investigating the sudden acceleration issue. This collaboration demonstrated a commitment to resolving the crisis and addressing the concerns of the authorities.

- Openness to Independent Investigation: In an effort to ensure transparency and unbiased assessment of the crisis, Toyota welcomed independent investigations into the unintended acceleration incidents. The company engaged external experts and formed advisory panels to evaluate their manufacturing processes, safety systems, and quality control measures.

- Recall and Repair Initiatives: Toyota initiated a massive recall campaign to address the safety issues associated with unintended acceleration. The company implemented comprehensive repair programs aimed at fixing the defects and improving the safety features in affected vehicles. These initiatives were crucial in demonstrating Toyota’s commitment to rectifying the problems and ensuring customer safety.

- Internal Process Evaluation : Toyota conducted internal evaluations and reviews of their manufacturing processes and quality control systems. They identified areas for improvement and implemented changes to prevent similar issues from arising in the future. This internal introspection showed a dedication to learning from the crisis and strengthening their processes.

Appointment of crisis management team

In response to the sudden acceleration crisis, Toyota recognized the need for a dedicated crisis management team to effectively handle the situation. The appointment of such a team was crucial in coordinating the company’s response, managing communications, and implementing appropriate strategies to address the crisis.

Toyota appointed experienced and senior executives to lead the crisis management team. These individuals had a deep understanding of the company’s operations, values, and stakeholder relationships. They were entrusted with making critical decisions and guiding the organization through the crisis.

The crisis management team comprised representatives from various functions and departments within Toyota, ensuring a comprehensive approach to addressing the crisis. Members included executives from engineering, manufacturing, quality control, legal, public relations, and other relevant areas. This cross-functional representation facilitated a holistic understanding of the issues and enabled effective collaboration.

Implementation of recall and repair programs

In response to the sudden acceleration crisis, Toyota implemented extensive recall and repair programs to address the safety concerns associated with unintended acceleration. These programs aimed to rectify the defects, enhance the safety features, and restore customer confidence.

Toyota identified the models and production years that were potentially affected by unintended acceleration issues. This involved a thorough examination of reported incidents, investigations, and collaboration with regulatory agencies. By pinpointing the specific vehicles at risk, Toyota could direct their efforts towards addressing the problem efficiently.

Toyota launched a comprehensive communication campaign to reach out to affected customers. The company sent notifications via mail, email, and other channels to inform them about the recall and repair programs. The communication highlighted the potential risks, steps to take, and the importance of addressing the issue promptly.

Toyota actively engaged its dealership network to support the recall and repair initiatives. Dealerships were provided with detailed information, training, and necessary resources to assist customers in scheduling appointments, conducting inspections, and performing the required repairs. This collaboration between the company and its dealerships aimed to ensure a seamless and efficient recall process.

Toyota developed a structured repair process to address the unintended acceleration issue in the affected vehicles. This involved inspecting and, if necessary, replacing or modifying components such as the accelerator pedals, floor mats, or electronic control systems. The company ensured an adequate supply of replacement parts to minimize delays and facilitate timely repairs.

Collaboration with regulatory bodies and industry experts

During the sudden acceleration crisis, Toyota recognized the importance of collaborating with regulatory bodies and industry experts to address the safety concerns and restore confidence in their vehicles. This collaboration involved working closely with relevant agencies and seeking external expertise to investigate the issue and implement necessary improvements.

Let’s delve into Toyota’s collaboration with regulatory bodies and industry experts:

- Regulatory Engagement: Toyota actively engaged with regulatory bodies, such as the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) in the United States and other similar agencies globally. The company cooperated with these organizations by providing them with relevant data, participating in investigations, and adhering to their guidelines and recommendations. This collaboration aimed to ensure a thorough and unbiased assessment of the sudden acceleration issue.

- Joint Investigations: Toyota collaborated with regulatory bodies in conducting joint investigations into the unintended acceleration incidents. These investigations involved sharing data, conducting extensive testing, and evaluating potential causes and contributing factors. By working together with the regulatory authorities, Toyota aimed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the problem and find effective solutions.

- Advisory Panels and External Experts: Toyota sought the expertise of external industry experts and formed advisory panels to provide independent assessments of the sudden acceleration issue. These panels consisted of experienced engineers, scientists, and safety specialists who analyzed the data, evaluated the vehicle systems, and offered recommendations for improvement. Their insights and recommendations helped guide Toyota’s response and ensure a thorough and impartial evaluation.

- Safety Standards Compliance: Toyota collaborated with regulatory bodies to ensure compliance with safety standards and regulations. The company actively participated in discussions and consultations to contribute to the development of robust safety standards for the automotive industry. By actively engaging with regulatory bodies, Toyota aimed to demonstrate its commitment to maintaining high safety standards and fostering an environment of continuous improvement.

- Sharing Best Practices: Toyota collaborated with industry peers and participated in industry forums and conferences to share best practices and learn from others’ experiences. By engaging with other automotive manufacturers, Toyota aimed to gain insights into safety practices, quality control measures, and crisis management strategies. This exchange of knowledge and collaboration helped Toyota strengthen their approach to safety and crisis management.

Final Words

Toyota crisis management case study serves as a valuable reminder to all automobiles companies on managing crisis. The sudden acceleration crisis presented a significant challenge for Toyota, testing the company’s crisis management capabilities and resilience. While Toyota demonstrated strengths in their crisis management strategy, such as a swift response, transparent communication, and a customer-focused approach, they also faced weaknesses and shortcomings. Initial denial, lack of transparency, and communication issues hampered their crisis response.

The crisis had profound financial consequences for Toyota, including costs associated with recalls, repairs, legal settlements, fines, and a decline in market value. Legal settlements were reached to address claims from affected customers, shareholders, and other stakeholders seeking compensation for damages and losses. The crisis also resulted in reputation damage that required significant efforts to rebuild trust and restore the company’s standing.

About The Author

Tahir Abbas

Related posts.

The Role of Social Media in Crisis Management

What is the Purpose of Change Management?

Role of Leadership in Change Management

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Contradictions That Drive Toyota’s Success

- Hirotaka Takeuchi,

- Norihiko Shimizu

Stable and paranoid, systematic and experimental, formal and frank: The success of Toyota, a pathbreaking six-year study reveals, is due as much to its ability to embrace contradictions like these as to its manufacturing prowess.

Reprint: R0806F

Toyota has become one of the world’s greatest companies only because it developed the Toyota Production System, right? Wrong, say Takeuchi, Osono, and Shimizu of Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo. Another factor, overlooked until now, is just as important to the company’s success: Toyota’s culture of contradictions.

TPS is a “hard” innovation that allows the company to continuously improve the way it manufactures vehicles. Toyota has also mastered a “soft” innovation that relates to human resource practices and corporate culture. The company succeeds, say the authors, because it deliberately fosters contradictory viewpoints within the organization and challenges employees to find solutions by transcending differences rather than resorting to compromises. This culture generates innovative ideas that Toyota implements to pull ahead of competitors, both incrementally and radically.

The authors’ research reveals six forces that cause contradictions inside Toyota. Three forces of expansion lead the company to change and improve: impossible goals, local customization, and experimentation. Not surprisingly, these forces make the organization more diverse, complicate decision making, and threaten Toyota’s control systems. To prevent the winds of change from blowing down the organization, the company also harnesses three forces of integration: the founders’ values, “up-and-in” people management, and open communication. These forces stabilize the company, help employees make sense of the environment in which they operate, and perpetuate Toyota’s values and culture.

Emulating Toyota isn’t about copying any one practice; it’s about creating a culture. And because the company’s culture of contradictions is centered on humans, who are imperfect, there will always be room for improvement.

No executive needs convincing that Toyota Motor Corporation has become one of the world’s greatest companies because of the Toyota Production System (TPS). The unorthodox manufacturing system enables the Japanese giant to make the planet’s best automobiles at the lowest cost and to develop new products quickly. Not only have Toyota’s rivals such as Chrysler, Daimler, Ford, Honda, and General Motors developed TPS-like systems, organizations such as hospitals and postal services also have adopted its underlying rules, tools, and conventions to become more efficient. An industry of lean-manufacturing experts have extolled the virtues of TPS so often and with so much conviction that managers believe its role in Toyota’s success to be one of the few enduring truths in an otherwise murky world.

- Hirotaka Takeuchi is a professor in the strategy unit of Harvard Business School.

- EO Emi Osono ( [email protected] ) is an associate professor;

- NS and Norihiko Shimizu ( [email protected] ) is a visiting professor at Hitotsubashi University’s Graduate School of International Corporate Strategy in Tokyo. This article is adapted from their book Extreme Toyota: Radical Contradictions That Drive Success at the World’s Best Manufacturer , forthcoming from John Wiley & Sons.

Partner Center

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7.2 Case in Point: Toyota Struggles With Organizational Structure

The Toad – Labadie Toyota Building – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Toyota Motor Corporation (TYO: 7203) has often been referred to as the gold standard of the automotive industry. In the first quarter of 2007, Toyota (NYSE: TM) overtook General Motors Corporation in sales for the first time as the top automotive manufacturer in the world. Toyota reached success in part because of its exceptional reputation for quality and customer care. Despite the global recession and the tough economic times that American auto companies such as General Motors and Chrysler faced in 2009, Toyota enjoyed profits of $16.7 billion and sales growth of 6% that year. However, late 2009 and early 2010 witnessed Toyota’s recall of 8 million vehicles due to unintended acceleration. How could this happen to a company known for quality and structured to solve problems as soon as they arise? To examine this further, one has to understand about the Toyota Production System (TPS).

TPS is built on the principles of “just-in-time” production. In other words, raw materials and supplies are delivered to the assembly line exactly at the time they are to be used. This system has little room for slack resources, emphasizes the importance of efficiency on the part of employees, and minimizes wasted resources. TPS gives power to the employees on the front lines. Assembly line workers are empowered to pull a cord and stop the manufacturing line when they see a problem.

However, during the 1990s, Toyota began to experience rapid growth and expansion. With this success, the organization became more defensive and protective of information. Expansion strained resources across the organization and slowed response time. Toyota’s CEO, Akio Toyoda, the grandson of its founder, has conceded, “Quite frankly, I fear the pace at which we have grown may have been too quick.”

Vehicle recalls are not new to Toyota; after defects were found in the company’s Lexus model in 1989, Toyota created teams to solve the issues quickly, and in some cases the company went to customers’ homes to collect the cars. The question on many people’s minds is, how could a company whose success was built on its reputation for quality have had such failures? What is all the more puzzling is that brake problems in vehicles became apparent in 2009, but only after being confronted by United States transportation secretary Ray LaHood did Toyota begin issuing recalls in the United States. And during the early months of the crisis, Toyota’s top leaders were all but missing from public sight.

The organizational structure of Toyota may give us some insight into the handling of this crisis and ideas for the most effective way for Toyota to move forward. A conflict such as this has the ability to paralyze productivity but if dealt with constructively and effectively, can present opportunities for learning and improvement. Companies such as Toyota that have a rigid corporate culture and a hierarchy of seniority are at risk of reacting to external threats slowly. It is not uncommon that individuals feel reluctant to pass bad news up the chain within a family company such as Toyota. Toyota’s board of directors is composed of 29 Japanese men, all of whom are Toyota insiders. As a result of its centralized power structure, authority is not generally delegated within the company; all U.S. executives are assigned a Japanese boss to mentor them, and no Toyota executive in the United States is authorized to issue a recall. Most information flow is one-way, back to Japan where decisions are made.

Will Toyota turn its recall into an opportunity for increased participation for its international manufacturers? Will decentralization and increased transparency occur? Only time will tell.

Case written based on information from Accelerating into trouble. (2010, February 11). Economist . Retrieved March 8, 2010, from http://www.economist.com/opinion/displaystory.cfm?story_id=15498249 ; Dickson, D. (2010, February 10). Toyota’s bumps began with race for growth. Washington Times , p. 1; Maynard, M., Tabuchi, H., Bradsher, K., & Parris, M. (2010, February 7). Toyota has pattern of slow response on safety issues. New York Times , p. 1; Simon, B. (2010, February 24). LaHood voices concerns over Toyota culture. Financial Times . Retrieved March 10, 2010, from http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/11708d7c-20d7-11df-b920-00144feab49a.html ; Werhane, P., & Moriarty, B. (2009). Moral imagination and management decision making. Business Roundtable Institute for Corporate Ethics . Retrieved April 30, 2010, from http://www.corporate-ethics.org/pdf/moral_imagination.pdf ; Atlman, A. (2010, February 24). Congress puts Toyota (and Toyoda) in the hot seat. Time . Retrieved March 11, 2010, from http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1967654,00.html .

Discussion Questions

- What changes in the organizing facet of the P-O-L-C framework might you make at Toyota to prevent future mishaps like the massive recalls related to brake and accelerator failures?

- Do you think Toyota’s organizational structure and norms are explicitly formalized in rules, or do the norms seem to be more inherent in the culture of the organization?

- What are the pros and cons of Toyota’s structure?

- What elements of business would you suggest remain the same and what elements might need revising?

- What are the most important elements of Toyota’s organizational structure?

Principles of Management Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Strategic Management - a Dynamic View

Organizational Identity, Corporate Strategy, and Habits of Attention: A Case Study of Toyota

Submitted: 20 April 2018 Reviewed: 24 August 2018 Published: 31 December 2018

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.81117

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Strategic Management - a Dynamic View

Edited by Okechukwu Lawrence Emeagwali

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

1,958 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

This chapter links organizational identity as a cohesive attribute to corporate strategy and a competitive advantage, using Toyota as a case study. The evolution of Toyota from a domestic producer, and exporter, and now a global firm using a novel form of lean production follows innovative tools of human resources, supply chain collaboration, a network identity to link domestic operations to overseas investments, and unparalleled commercial investments in technologies that make the firm moving from a sustainable competitive position to one of unassailable advantage in the global auto sector. The chapter traces the strategic moves to strength Toyota’s identity at all levels, including in its overseas operations, to build a global ecosystem model of collaboration.

- institutional identity

- lean management

- learning symmetries

- habits of attention

Author Information

Charles mcmillan *.

- Schulich School of Business, York University, Toronto, Canada

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

(Article for Lawrence Emeagwali (Ed.), Strategic Management . London, 2018)

October 18, 2018.

“There is no use trying” said Alice, “we cannot believe impossible things.”—Lewis Carroll

1. Introduction

Few organizations combine the institutional benefits of longevity and tradition with the disruptive startup advantages of novelty and suspension of path dependent behavior. This chapter provides a case study of Toyota Corporation, an organization with an explicit philosophy that embodies “…standardized work and kaizen (that) are two sides of the same coin. Standardized work provides a consistent basis for maintaining productivity, quality and safety at high levels. Kaizen furnishes the dynamics of continuing improvement and the very human motivation of encouraging individuals to take part in designing and managing their own jobs” ([ 1 ], p. 38). Toyota’s philosophy, combining a model that is “stable and paranoid, systematic experimental, formal and frank” [ 2 ], often called the Toyota Way, evolved from the founding of Toyoda Automatic Loom Works, founded in 1911, setting up an auto division in 1933, and Toyota Motor Company in 1937 [ 3 ].

What is unique about Toyota and its pioneering lean production, described colloquially as just-in-time (JIT), embraces a deliberative philosophy that establishes a corporate identity for safety, quality, and aspirational performance goals. Going forward, with plants and distribution centers around the world, Toyota cultivates a direct involvement of employees, suppliers, and other organizations, called the Toyota Group, as a network identity that extends boundary members of the firm’s eco-system that also embodies detailed performance measures to strengthen and reinforce identity enhancement. These identity attributes creating novel and seemingly contradictory configurations, both at home and now in global markets. Toyota provides a framework to link identity as a cohesive attribute for problem-solving with explicit, data-driven benchmarks, a DNA that encompasses observation, analysis, hypothesis testing from the shop floor to the executive suite [ 3 , 4 ].

The concept of identity has a long pedigree in the social sciences, dating from classical writers like Adam Smith, Karl Marx, Max Weber, and Emile Durkheim, focusing on individual identities separate and distinct from larger social systems arising from the division of labor. However, identity in organizations is a relatively new construct, based on claims that are “central, distinctive, and enduring” [ 5 ]. Despite the growing literature on organizational identity [ 6 , 7 ], there is less consensus given the multiple disciplinary focus, the levels of analysis, well as minimum empirical work linking organizational identity to corporate strategy. In some cases, identity linkages touch on outcomes like brand equity, reputation, visual media like social networking and the gap between defining what the organization is today and what it wants to become, despite the high failure rate of firms [ 8 ]. Indeed, there is little reason to doubt that “the concept of organizational identity is suffering an identity crisis” ([ 9 ], p. 206).

Despite the growing literature on organization identity, encompassing diverse constructs and methodologies [ 6 , 7 ], often at different organizational levels (individuals, groups and senior management), has limited empirical study linking individual and group identity both to corporate strategy and corporate performance. Various accounts of social experiences, concentrating on a sense of insider and outsider to frame a mutual identity mindset that shapes organizational identity, apply personal histories and narratives, but leave open the distinction between corporate identity and organizational identity [ 10 ]. Identity producing mechanisms flowing from purposeful actions vary by context, such as universities and faith-based organizations to technology and engineering organizations with complicated role activities grounded in socio-technical design [ 11 ]. Compelling cases of identity as a tool for organizational integration, or the impact of cleavage and conflict owing to human diversity policies, personality characteristics of key actors, and sub-unit identity images advance understanding of behavior within organizations, but often ignores how both strategic choice and external forces impact these internal mindsets. Many scholars associate internal identity issues to external stakeholders using sundry communication tools (e.g., [ 12 ]) but the literature has few studies that explain what organizational identity features are truly different and give a competitive advantage in contested markets over time. To advance hypothesis testing and to encourage conceptual development in both theory and practice, there must be a linkage to identity as a construct that provides insights to an organization’s competitive advantage.

This chapter addresses the issues linking strategic choices and capabilities to Toyota’s identity as a case study. Toyota’s strategic positioning and high-performance outcomes amplify identity tools at three levels, its employees (both in Japan and its factories overseas), its suppliers, and its customers. Depicted as a best practice company [ 13 ], Toyota is seen as a model to emulate in sectors as diverse as hospitals and retailing. This chapter has three objectives: first, by examining Toyota’s transformation as a leading domestic producer to a top global company, the firm’s core identity has changed little despite numerous internal and external changes; second, Toyota as a case study illustrates the capacity to have multiple images in different contexts, without sacrificing its core identity; and third, the chapter offers recommendations for empirical studies of organizational identity.

2. Organizational identification and identity

In their seminal article, Stuart and Whetten [ 5 ] put forward the concept of organizational identity constituting a set of “claims” and specified what was central, distinctive and enduring, but recognizing that organizations can have multiple identities and claims that can be contradictory, ambiguous, or even unrelated. While some authors have attempted to provide more clarity, Pratt addresses the construct of identity and its generality, stating it was “often overused and under specified” beyond general statements about “who are we?” and “who do we want to become?”

Historically, identity and identification are described in classical writings focusing on societies, social systems, and their constituent parts. Such examples as Adam Smith in economics on the division of labor, Babbage on the division of work tasks, Marx on division of social class, Max Weber on the division of status and occupation, and Durkheim on differentiated social structures, each contributed to current views of how individuals, groups, and teams become a cohesive collective in a complex organization. More specifically, Durkheim’s [ 14 ] analysis of the division of labor and differentiated social structures with distinct socio-psychological values and impacts required variations in role homogeneity in sub-systems. 1 His views influenced subsequent writers as diverse as Freud in psychiatry and Harold Laswell in political theory, whose study of world politics includes a chapter entitled “Nations and Classes: The Symbols of Identification.”

Simon [ 15 ] introduced identification to organization theory, describing it as follows: “the process of identification permits the broad organizational arrangements to govern the decisions of the persons who participate in the structure” (p. 102). More specifically, “a person identifies himself with a group when, in making a decision, he evaluates the several alternatives of choice in terms of their consequences for the specified group” in contrast to personal motivation, where “his evaluation is based upon an identification with himself or his family” ([ 16 ], p. 206). Both the fault lines of identity, based on status, perverse incentives, class or occupation, as well as group identification [ 17 ] impact organizational performance by variations in shared goals and preferences, as well as forms of interaction and feedback, often enhanced or lessoned by recruitment patterns and work rules and incentives.

Identity and identification as reference points in organizations also flow from the configuration of roles, role structures, and “clusters of activities” where “a person has an occupational self-identity and is motivated to behave in ways which affirm and enhance the value attributes of that identity” ([ 18 ], p. 179). Theories of social identity assume individual identity is partitioned into ingroups and outgroups is social situations and organizational life, often with an implicit cost–benefit calculation, but acts of altruistic behavior, where behavioral norms benefit the welfare of others, often seen in “collectivist societies,” strengthens organizational identity [ 19 ]. Other approaches take a social constructionist approach, emphasizing social and cultural perspectives [ 20 ], where sense-making comes from stories and narratives of everyday experience [ 21 ], thereby, “…in linking identity and narrative in an individual, we link an individual [career] story to a particular cultural and historical narrative of a group” [ 22 ]. Going further, Dutton et al. [ 23 ] speculate that organizational identification is a process of self-categorization cultivated by distinctive, central, and enduring attributes that get reflected in corporate image, reputation, or strategic vision. Alvesson [ 24 ] describes the need for identity alignment: “…by strengthening the organization’s identity—its experienced distinctiveness, consistency, and stability—it can be assumed that individual identities and identification will be strengthen with what they are supposed to be doing at their work place.”

While some studies [ 25 ] purport to focus on managerial strategies that project images as a tool to shape distinctive identities with stakeholders, the reality is that organizational identities without corresponding integration of individual, sub-unit, or group identification may lead to behavioral frictions, and detachment via lower compliance and cues of detachment. Conflict and cleavages affect group-binding identification, often persisting as conformity of opinion, forms of social interaction, and group loyalties, as well as enhancing internal legitimacy for desired outcomes. While both individuals and groups may have multiple and loosely connected identities, there remains lingering organizations dysfunctions that exacerbate cleavage and conflict, such as hypocrisy, selective amnesia, or disloyalty [ 18 ]. Psychological exit comes from unsatisfactory outcomes, a form of weakening organizational identity and strengthening group identity to give voice for remedial actions [ 26 ]. In the extreme, such sub-identities found in groups and sub-units compete with other forms of identification and may lead to organizational dysfunctions [ 17 ].

Akerlof and Kranton [ 27 ] view organizational identity, with emphasis on why firms must transform workers from outsiders to insiders, as a form of motivational capital. In short, a distinctive identity is a distinctive competence. To quote Likert [ 28 ]. “the favorable attitudes towards the organization and the work are not those of easy complacency but are the attitudes of identification with the organization and its objectives and a high sense of involvement in achieving them” (p. 98). Other theorists suggest variations in organizational identity impact sense-making and interpretative processes [ 29 ], internalization of learning [ 10 ] and processes linking shared values and modes of performance [ 30 ].

Identity and identification cues, viewed as the mental perceptions of individual self-awareness, social interactions and experiences, and self-esteem have many antecedents, such as social class [ 31 ], demographic factors like age, race, religion, or sex [ 32 ], and national culture and identity [ 33 ]. Studies emphasizing social construction perspectives stem from individual accounts, often defined in social narratives, histories, and biographies rooted in time and place [ 34 ]. As Hammack [ 22 ] emphasizes, “…in linking identity and narrative in an individual, we link an individual story to a particular cultural and historical narrative of a group” (p. 230). At a general level, organizational culture depicts the set of norms and values that are widely shared and strongly held throughout the organization [ 35 ], and refers to the “unspoken code of communication among members of an organization” [ 36 ] and aids and supplements task coordination and group identity. In this way, individual employees better understand the premises of decision choices in problem solving at the organizational level. In complex organizations, identity is linked to the strategic capacity of choice opportunities and implementation dynamics of priorities and preferences. As Thoenig and Paradieise [ 37 ] emphasize, “strategic capacity lies to a great extent in how much its internal subunits … shape its identity, define its priorities approve its positions, prepare the way for general agreement to be adopted on its roadmap and provide a framework for the decisions and acts of all its components” (p. 299).

Such diverse views leave open how organizational identity, or shared central vision, confers competitive advantage in contested spaces. As a starting hypothesis, a shared identity strengthens coordination across diverse groups applying common norms, codes and protocols, hence improving shared learning skills. In a similar vein, individual cleavages and loyalties are lessoned by shared interactions and information sharing that mobilize learning tools. Further, organizational identity strengthens individual identities via performance success that promotes a shared set of preferences, expectation, and habits of rule setting.

3. Organizational performance at Toyota

By any standards—shareholder value, product innovation, employee satisfaction measured by low turnover and lack of strike action, market capitalization—Toyota has been astonishingly successful, both against rival incumbents in the auto sector, but as a organizational pioneer in transportation with just-in-time thinking. Against existing rivals at home, or in an industry with firms pursuing growth by alliances and acquisition (Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi, VW-Porsche), facing receivership and saved by public funding (GM and Chrysler), exiting as a going concern (British Leyland) or new startups (Tesla). Toyota’s performance is unrivaled. Toyota remains a firm committed to organic development, steady and consistent market share in all key international markets, and cultivating a shared identity within its eco-system around measurable outcomes of product safety, quality, and consumer value.

As shown in Figure 1 , despite many forms of competitive advantages, such as size, high domestic market share, being part of a larger group, or diversification, there are many times when the side expected to win actually is less profitable and may actually lose. Toyota’s growth and expansion, despite the turbulent 2009 recall and temporary retreats [ 38 , 39 ], comes with consistent profitability and market share growth. In this organizational transformation, Toyota has replicated its identity of “safety, quality, and value” outside its home market, often depicted by foreigners as “inscrutable,” closed, and Japan Inc. [ 40 ]. Strategically, this organizational identity framework is multipurpose, allowing shared alignment of identities with domestic employees, suppliers and supervisors, but also incorporating these identity attributes first to foreign operations in North America and subsequently to Europe and Asia. Toyota management considers the firm as a learning organization, where learning symmetries take place at all levels, vertically and horizontally.

Operating Profits versus Firm Revenues in the Auto Sector.

Unlike many corporate design models of multinationals, where foreign subsidiaries passively replicate the production systems of the home market (a miniature replica effect) or seek out decision-attention from head-quarters [ 41 ] Toyota is evolving as a global enterprise. In this model, Toyota’s foreign subsidies and trade blocks (e.g., NAFTA and Europe), solve key problems and translate the protocols for headquarters and its global network of factories, distribution outlets, and service and maintenance dealerships. In this way, Toyota’s training protocols, network learning systems, and using foreign subsidies to develop new technologies (e.g., Toyota Canada pioneering cold weather technologies for ignitions engineering), i.e., a learning chain that mobilizes employee identity to network identity, including its global supply chain collaboration [ 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ].

To illustrate the complexity of contemporary auto production and the need to evolve both organizational design around supply chains, and the nature of complementarities in production, firms like Toyota must realign engineering and technological systems to novel role configurations for a diverse workforce. A car (or truck) has over 5000 parts, components, and sub-assemblies, where factories are linked to diverse supply chains with tightly-knit communications and transport linkages, often across national boundaries, to produce a factory production cycle of 1 minute per vehicle, or even less. Parts or components like steel, for instance, are not commodities, undifferentiated only by price, and Japanese steel producers produced the high carbon steel that was more resistant to water, hence rust. This production cycle demands very high quality and safety of each part and component, plus the precision engineering processes to assemble them. This alignment determines not only the standards of quality and safety of the finished vehicle but the image and reputation of the company, plus an indispensable need to retain price value of the brand in the aftermarket sales cycle.

To this contemporary production system, reshaped and refined since Toyota first introduced in 1956 what Womack et al. [ 46 ] termed “the machine that changed the world,” auto production now faces a steady, relentless, and inexorable technology disruption. This shift in engines and fuel consumption technologies, away from diesel and gasoline-powered vehicles, to new dominant technologies, such as electric vehicles, fuel-cells, battery, hydrogen, or hybrid, each requiring massive changes to traditional parts and components suppliers, and the layout of factory assembly. Successful firms thus require forward-looking strategic intent and novel organizational configurations both to exploit existing systems based on gasoline vehicles, or novel organizational systems to explore new technologies and processes. Strategies differ widely. Tesla as a new startup has dedicated factories and labs using lithium battery technology. To gain equivalent scale of Toyota, GM, and Volkswagen, i.e., over 10 million vehicles per year, Nissan and Renault joined with Mitsubishi as a new alliances and equity investment partner.

By contrast, both Ford and GM are retreating from large markets like Europe, Japan, or India with direct-foreign investment strategies. Even more intrusive to existing production programs and protocols are new demands for data analytics, artificial intelligence, robotic and associated Internet and social media technologies. Both incumbent firms, new startups, and suppliers are developing futuristic technologies in drivers’ facial recognition, driving habits, and consumer disabilities, from wheel chairs to hearing that impact cars of the future, and impose threats to existing distinctive competences and corporate identity. Not all firms can manage simultaneously the processes of exploitation of existing organizational programs, and the exploration of product innovation and assembly [ 47 ]. Toyota is an exception.

The Toyota production system is transformational, an organizational philosophy around two core ideas, kaizen or principles of continuous improvement, and nemawashi , or consensus decision-making that allow network effects across its global factories, research labs, its supplier organizations, and related parts of the global eco-system, from universities to global shipping firms. In the firm’s century-old evolution, starting as a leading textile firm that still exists but migrating to auto manufacturing as only the second largest by unit sales (behind Nissan), Toyota has emerged as the top producer both at home and globally, measured by market share, and a leading player in markets like North America, Europe, Latin America, India and China, where many rivals have a low market share presence (e.g., Europe firms in the US, American firms in Europe).

Strategies of corporate retreat in key markets (GM in Europe, GM and Ford in India, Ford in Japan), suggest home market advantages are the new testing ground for first-mover disadvantage [ 48 ] when firms face massive technology disruption. To cite an example, during the 1990s, four major automakers, Toyota, GM, Honda, and Ford, took the lead in the development of hybrid technologies, with GM the leader with 23 patents in hybrid vehicles (vs. 17 for Toyota, 16 for Ford, and 8 for Honda). By 2000, however, Honda and Toyota were the clear leaders, with Honda had filed 170 patents, and Toyota with 166 in hybrid drivetrain technology, far ahead pf Ford with 85 and GM at 56. Today, Fords’ hybrid is a license from Toyota.

4. Toyota identity as a social construct

The auto sector symbolizes the development of post-war multinationals largely based on firm-specific capabilities and proprietary advantages. This organizational evolution includes changing work mechanisms characterized as machine theory by management [ 49 ], a catch-all phrase to describe scientific management techniques espoused by Frederick Taylor from his 1911 book with that title. He first learned time management at Philips Executer Academy and became an early practitioner of what became known as kaizen, continuous improvement, working with Henry Gantt [ 50 ], studying all aspects of work, tools, machine speeds, workflow design, the conversion of raw materials into finished products, and payment systems. The Taylor studies, later dubbed Fordism [ 51 ], was an approach to eliminate waste and unnecessary movements, or “soldiering”—a deliberate restriction of worker output.

Taylor’s disciples in the engineering profession spread his message beyond America, to Europe, as well as to Japan and Russia, where even Lenin and Trotsky developed an interest after the Revolution of 1917. In appearances before Congressional committees, and in other forums, Taylor’s theories faced withering criticisms and great resistance by American union movement a “dehumanizing of the worker” and a tool for profits at the expense of the worker. [ 50 , 52 ]. In Japan, however, Taylorism and scientific management had wide acceptance, starting with Yukinori Hoshino’s translation of Principles of Scientific Management with the title, The Secret of Saving Lost Motion, which sold 2 million copies. Several firms adopted scientific management practices, including standard motions, worker bonuses, and Japanese authors published best sellers on similar notions of work practices, including one entitled Secrets for Eliminating Futile Work and Increasing Production [ 3 ].

After 1945 in Japan, given the wartime devastation of Japan’s industrial capacity, resource scarcity—food, building supplies, raw materials of all sorts, electric power—had a profound and lasting impact on Japanese society, even more so when the American military supervised the Occupation and displayed abundance of everyday goods—big cars, no shortage of food, long leisure hours, and consumer spending using American dollars. As Japanese firms slowly rebuilt, the corporate ethos promoted efficient use of everything, and waste became a watchword for inefficiency. Japanese executives visited US factories, the Japanese media documented US success stories. American management practices were widely emulated, and US consultants—notably Peter Drucker, W. Juran, and W. Edwards Deming—had an immense following and their books, papers and personal appearances were publicized, translated and widely-read, even by high school students. While American firms emphasized a marketing philosophy where the customer is king, Japanese firms remained committed to production, helped in part by trading firms, led by the nine giant Soga Sosha , to distribute and sell both at home and abroad. US human resource practices also showed a stark contrast with Japanese practices. In the US, the rise of the trade union movement and national legislation from Roosevelt’s New Deal, meant that management-worker relations for firms and factories were contractual, setting out legal norms, and negotiated commitments for pay, seniority, promotion, job rotation and skills differentials, so that worker identity was less towards the firm, more to the trade union, and what incentives and compensation union leadership could deliver [ 53 ].