- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 24 October 2019

A scoping review of the literature on the current mental health status of physicians and physicians-in-training in North America

- Mara Mihailescu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6878-1024 1 &

- Elena Neiterman 2

BMC Public Health volume 19 , Article number: 1363 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

26k Accesses

56 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

This scoping review summarizes the existing literature regarding the mental health of physicians and physicians-in-training and explores what types of mental health concerns are discussed in the literature, what is their prevalence among physicians, what are the causes of mental health concerns in physicians, what effects mental health concerns have on physicians and their patients, what interventions can be used to address them, and what are the barriers to seeking and providing care for physicians. This review aims to improve the understanding of physicians’ mental health, identify gaps in research, and propose evidence-based solutions.

A scoping review of the literature was conducted using Arksey and O’Malley’s framework, which examined peer-reviewed articles published in English during 2008–2018 with a focus on North America. Data were summarized quantitatively and thematically.

A total of 91 articles meeting eligibility criteria were reviewed. Most of the literature was specific to burnout ( n = 69), followed by depression and suicidal ideation ( n = 28), psychological harm and distress ( n = 9), wellbeing and wellness ( n = 8), and general mental health ( n = 3). The literature had a strong focus on interventions, but had less to say about barriers for seeking help and the effects of mental health concerns among physicians on patient care.

Conclusions

More research is needed to examine a broader variety of mental health concerns in physicians and to explore barriers to seeking care. The implication of poor physician mental health on patients should also be examined more closely. Finally, the reviewed literature lacks intersectional and longitudinal studies, as well as evaluations of interventions offered to improve mental wellbeing of physicians.

Peer Review reports

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.” [ 41 ] One in four people worldwide are affected by mental health concerns [ 40 ]. Physicians are particularly vulnerable to experiencing mental illness due to the nature of their work, which is often stressful and characterized by shift work, irregular work hours, and a high pressure environment [ 1 , 21 , 31 ]. In North America, many physicians work in private practices with no access to formal institutional supports, which can result in higher instances of social isolation [ 13 , 27 ]. The literature on physicians’ mental health is growing, partly due to general concerns about mental wellbeing of health care workers and partly due to recognition that health care workers globally are dissatisfied with their work, which results in burnout and attrition from the workforce [ 31 , 34 ]. As a consequence, more efforts have been made globally to improve physicians’ mental health and wellness, which is known as “The Quadruple Aim.” [ 34 ] While the literature on mental health is flourishing, however, it has not been systematically summarized. This makes it challenging to identify what is being done to improve physicians’ wellbeing and which solutions are particularly promising [ 7 , 31 , 33 , 37 , 38 ]. The goal of our paper is to address this gap.

This paper explores what is known from the existing peer-reviewed literature about the mental health status of physicians and physicians-in-training in North America. Specifically, we examine (1) what types of mental health concerns among physicians are commonly discussed in the literature; (2) what are the reported causes of mental health concerns in physicians; (3) what are the effects that mental health concerns may have on physicians and their patients; (4) what solutions are proposed to improve mental health of physicians; and (5) what are the barriers to seeking and providing care to physicians with mental health concerns. Conducting this scoping review, our goal is to summarize the existing research, identifying the need for a subsequent systematic review of the literature in one or more areas under the study. We also hope to identify evidence-based interventions that can be utilized to improve physicians’ mental wellbeing and to suggest directions for future research [ 2 ]. Evidence-based interventions might have a positive impact on physicians and improve the quality of patient care they provide.

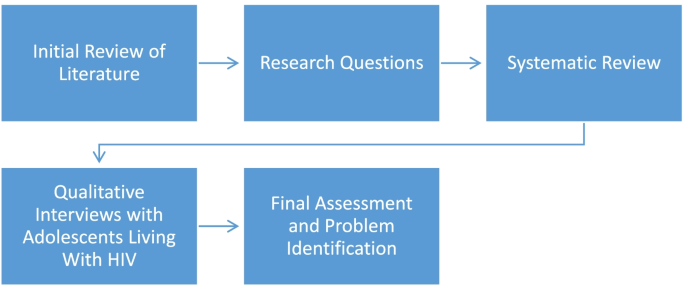

A scoping review of the academic literature on the mental health of physicians and physicians-in-training in North America was conducted using Arksey and O’Malley’s [ 2 ] methodological framework. Our review objectives and broad focus, including the general questions posed to conduct the review, lend themselves to a scoping review approach, which is suitable for the analysis of a broader range of study designs and methodologies [ 2 ]. Our goal was to map the existing research on this topic and identify knowledge gaps, without making any prior assumptions about the literature’s scope, range, and key findings [ 29 ].

Stage 1: identify the research question

Following the guidelines for scoping reviews [ 2 ], we developed a broad research question for our literature search, asking what does the academic literature tell about mental health issues among physicians, residents, and medical students in North America ? Burnout and other mental health concerns often begin in medical training and continue to worsen throughout the years of practice [ 31 ]. Recognizing that the study and practice of medicine plays a role in the emergence of mental health concerns, we focus on practicing physicians – general practitioners, specialists, and surgeons – and those who are still in training – residents and medical students. We narrowed down the focus of inquiry by asking the following sub-questions:

What types of mental health concerns among physicians are commonly discussed in the literature?

What are the reported causes of mental health problems in physicians and what solutions are available to improve the mental wellbeing of physicians?

What are the barriers to seeking and providing care to physicians suffering from mental health problems?

Stage 2: identify the relevant studies

We included in our review empirical papers published during January 2008–January 2018 in peer-reviewed journals. Our exclusive focus on peer-reviewed and empirical literature reflected our goal to develop an evidence-based platform for understanding mental health concerns in physicians. Since our focus was on prevalence of mental health concerns and promising practices available to physicians in North America, we excluded articles that were more than 10 years old, suspecting that they might be too outdated for our research interest. We also excluded papers that were not in English or outside the region of interest. Using combinations of keywords developed in consultation with a professional librarian (See Table 1 ), we searched databases PUBMed, SCOPUS, CINAHL, and PsychNET. We also screened reference lists of the papers that came up in our original search to ensure that we did not miss any relevant literature.

Stage 3: literature selection

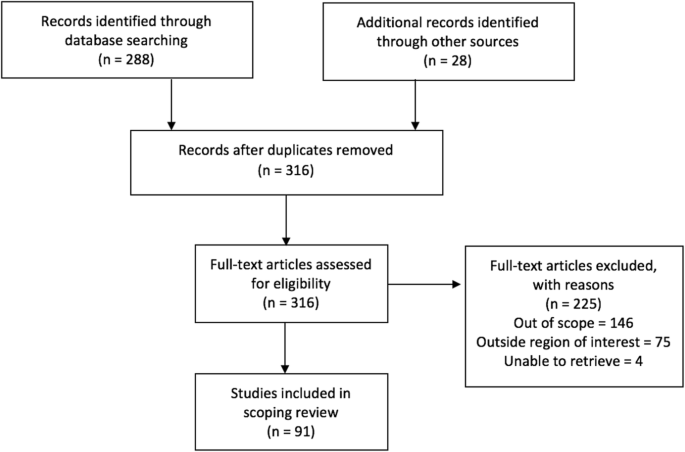

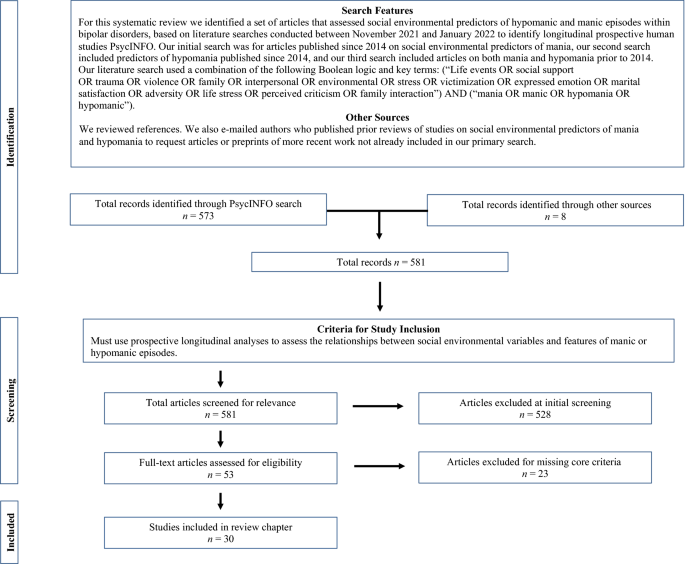

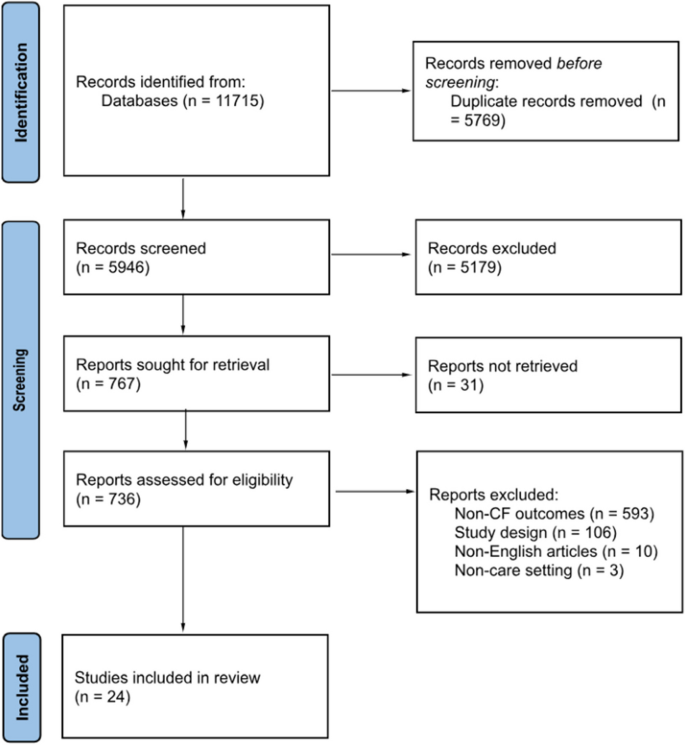

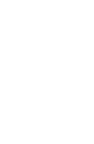

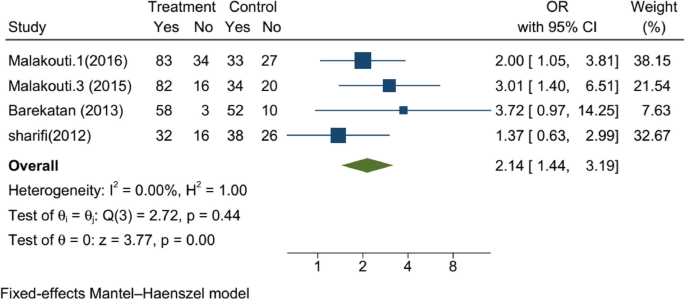

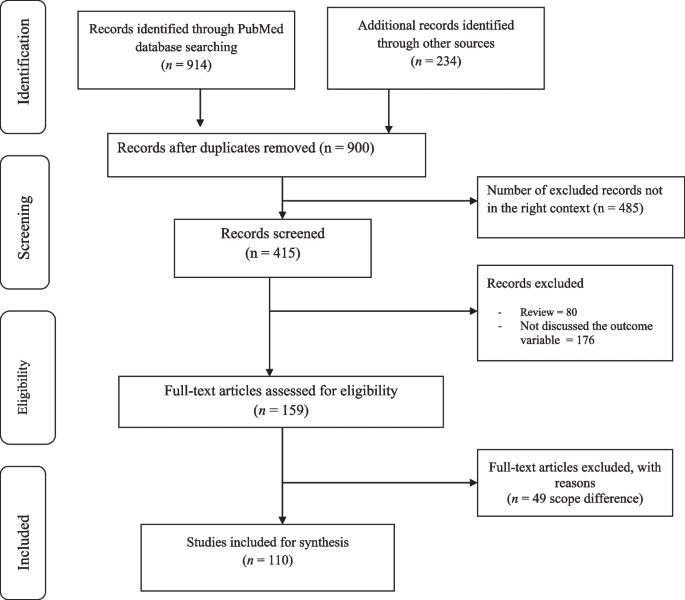

Publications were imported into a reference manager and screened for eligibility. During initial abstract screening, 146 records were excluded for being out of scope, 75 records were excluded for being outside the region of interest, and 4 papers were excluded because they could not be retrieved. The remaining 91 papers were included into the review. Figure 1 summarizes the literature search and selection.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Stage 4: charting the data

A literature extraction tool was created in Microsoft Excel to record the author, date of publication, location, level of training, type of article (empirical, report, commentary), and topic. Both authors coded the data inductively, first independently reading five articles and generating themes from the data, then discussing our coding and developing a coding scheme that was subsequently applied to ten more papers. We then refined and finalized the coding scheme and used it to code the rest of the data. When faced with disagreements on narrowing down the themes, we discussed our reasoning and reached consensus.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The data was summarized by frequency and type of publication, mental health topics, and level of training. The themes inductively derived from the data included (1) description of mental health concerns affecting physicians and physicians-in-training; (2) prevalence of mental health concerns among this population; (3) possible causes that can explain the emergence of mental health concerns; (4) solutions or interventions proposed to address mental health concerns; (5) effects of mental health concerns on physicians and on patient outcomes; and (6) barriers for seeking and providing help to physicians afflicted with mental health concerns. Each paper was coded based on its relevance to major theme(s) and, if warranted, secondary focus. Therefore, one paper could have been coded in more than one category. Upon analysis, we identified the gaps in the literature.

Characteristics of included literature

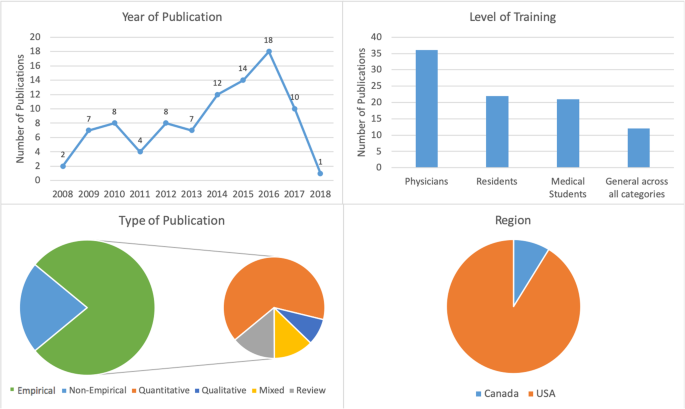

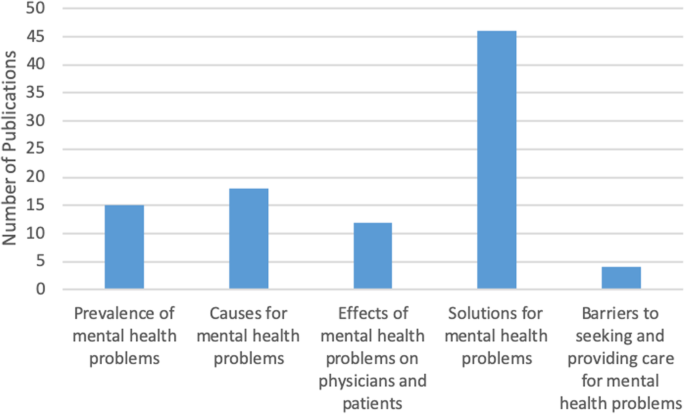

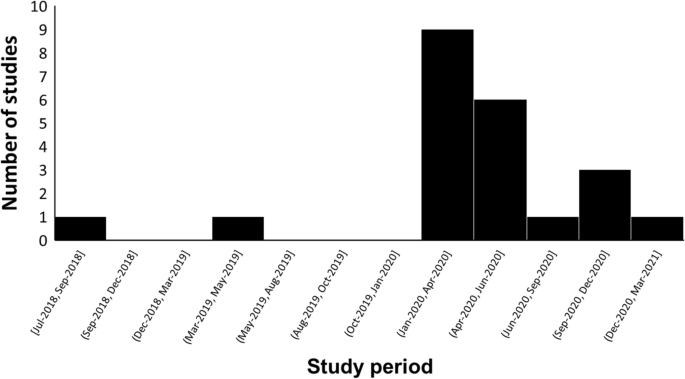

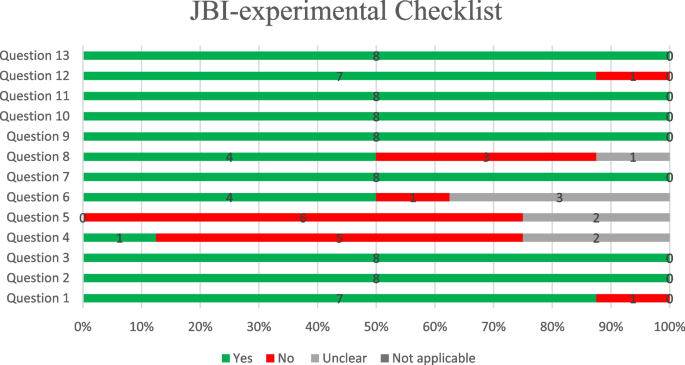

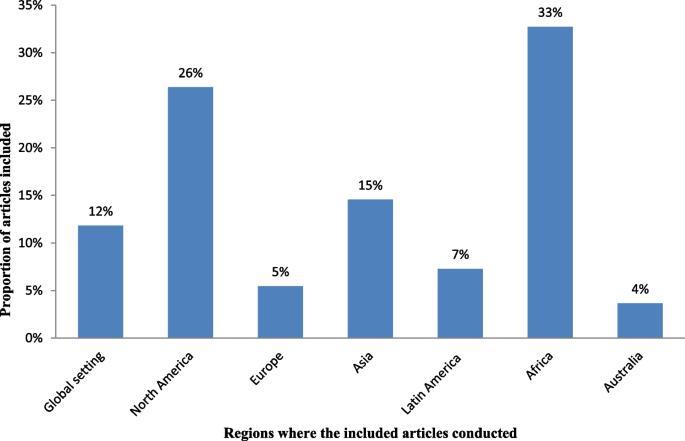

The initial search yielded 316 records of which 91 publications underwent full-text review and were included in our scoping review. Our analysis revealed that the publications appear to follow a trend of increase over the course of the last decade reflecting the growing interest in physicians’ mental health. More than half of the literature was published in the last 4 years included in the review, from 2014 to 2018 ( n = 55), with most publications in 2016 ( n = 18) (Fig. 2 ). The majority of papers ( n = 36) focused on practicing physicians, followed by papers on residents ( n = 22), medical students ( n = 21), and those discussing medical professionals with different level of training ( n = 12). The types of publications were mostly empirical ( n = 71), of which 46 papers were quantitative. Furthermore, the vast majority of papers focused on the United States of America (USA) ( n = 83), with less than 9% focusing on Canada ( n = 8). The frequency of identified themes in the literature is broken down into prevalence of mental health concerns ( n = 15), causes of mental health concerns ( n = 18), effects of mental health concerns on physicians and patients ( n = 12), solutions and interventions for mental health concerns ( n = 46), and barriers to seeking and providing care for mental health concerns ( n = 4) (Fig. 3 ).

Number of sources by characteristics of included literature

Frequency of themes in literature ( n = 91)

Mental health concerns and their prevalence in the literature

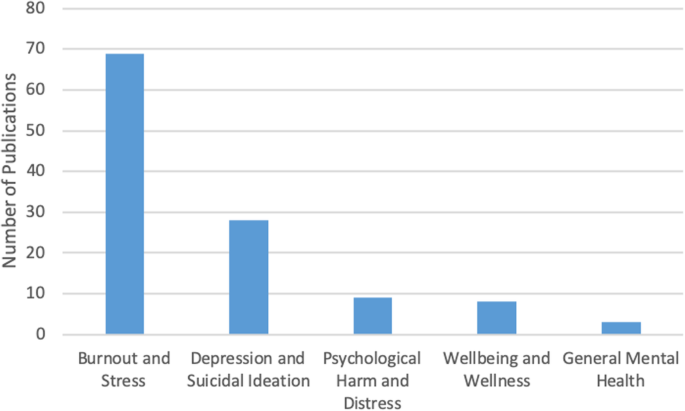

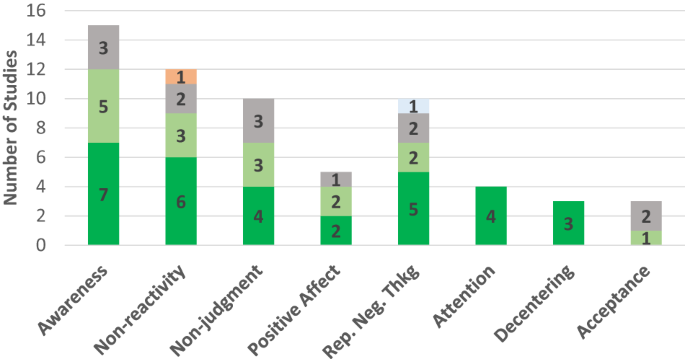

In this thematic category ( n = 15), we coded the papers discussing the prevalence of specific mental health concerns among physicians and those comparing physicians’ mental health to that of the general population. Most papers focused on burnout and stress ( n = 69), which was followed by depression and suicidal ideation ( n = 28), psychological harm and distress ( n = 9), wellbeing and wellness ( n = 8), and general mental health ( n = 3) (Fig. 4 ). The literature also identified that, on average, burnout and mental health concerns affect 30–60% of all physicians and residents [ 4 , 5 , 8 , 9 , 15 , 25 , 26 ].

Number of sources by mental health topic discussed ( n = 91)

There was some overlap between the papers discussing burnout, depression, and suicidal ideation, suggesting that work-related stress may lead to the emergence of more serious mental health problems [ 3 , 12 , 21 ], as well as addiction and substance abuse [ 22 , 27 ]. Residency training was shown to produce the highest rates of burnout [ 4 , 8 , 19 ].

Causes of mental health concerns

Papers discussing the causes of mental health concerns in physicians formed the second largest thematic category ( n = 18). Unbalanced schedules and increasing administrative work were defined as key factors in producing poor mental health among physicians [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 13 , 15 , 27 ]. Some papers also suggested that the nature of the medical profession itself – competitive culture and prioritizing others – can lead to the emergence of mental health concerns [ 23 , 27 ]. Indeed, focus on qualities such as rigidity, perfectionism, and excessive devotion to work during the admission into medical programs fosters the selection of students who may be particularly vulnerable to mental illness in the future [ 21 , 24 ]. The third cluster of factors affecting mental health stemmed from structural issues, such as pressure from the government and insurance, fragmentation of care, and budget cuts [ 13 , 15 , 18 ]. Work overload, lack of control over work environment, lack of balance between effort and reward, poor sense of community among staff, lack of fairness and transparency by decision makers, and dissonance between one’s personal values and work tasks are the key causes for mental health concerns among physicians [ 20 ]. Govardhan et al. conceptualized causes for mental illness as having a cyclical nature - depression leads to burnout and depersonalization, which leads to patient dissatisfaction, causing job dissatisfaction and more depression [ 19 ].

Effects of mental health concerns on physicians and patients

A relatively small proportion of papers (13%) discussed the effects of mental health concerns on physicians and patients. The literature prioritized the direct effect of mental health on physicians ( n = 11) with only one paper focusing solely on the indirect effects physicians’ mental health may have on patients. Poor mental health in physicians was linked to decreased mental and physical health [ 3 , 14 , 15 ]. In addition, mental health concerns in physicians were associated with reduction in work hours and the number of patients seen, decrease in job satisfaction, early retirement, and problems in personal life [ 3 , 5 , 15 ]. Lu et al. found that poor mental health in physicians may result in increased medical errors and the provision of suboptimal care [ 25 ]. Thus physicians’ mental wellbeing is linked to the quality of care provided to patients [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 10 , 17 ].

Solutions and interventions

In this largest thematic category ( n = 46) we coded the literature that offered solutions for improving mental health among physicians. We identified four major levels of interventions suggested in the literature. A sizeable proportion of literature discussed the interventions that can be broadly categorized as primary prevention of mental illness. These papers proposed to increase awareness of physicians’ mental health and to develop strategies that can help to prevent burnout from occurring in the first place [ 4 , 12 ]. Some literature also suggested programs that can help to increase resilience among physicians to withstand stress and burnout [ 9 , 20 , 27 ]. We considered the papers referring to the strategies targeting physicians currently suffering from poor mental health as tertiary prevention . This literature offered insights about mindfulness-based training and similar wellness programs that can increase self-awareness [ 16 , 18 , 27 ], as well as programs aiming to improve mental wellbeing by focusing on physical health [ 17 ].

While the aforementioned interventions target individual physicians, some literature proposed workplace/institutional interventions with primary focus on changing workplace policies and organizational culture [ 4 , 13 , 23 , 25 ]. Reducing hours spent at work and paperwork demands or developing guidelines for how long each patient is seen have been identified by some researchers as useful strategies for improving mental health [ 6 , 11 , 17 ]. Offering access to mental health services outside of one’s place of employment or training could reduce the fear of stigmatization at the workplace [ 5 , 12 ]. The proposals for cultural shift in medicine were mainly focused on promoting a less competitive culture, changing power dynamics between physicians and physicians-in-training, and improving wellbeing among medical students and residents. The literature also proposed that the medical profession needs to put more emphasis on supporting trainees, eliminating harassment, and building strong leadership [ 23 ]. Changing curriculum for medical students was considered a necessary step for the cultural shift [ 20 ]. Finally, while we only reviewed one paper that directly dealt with the governmental level of prevention, we felt that it necessitated its own sub-thematic category because it identified the link between government policy, such as health care reforms and budget cuts, and the services and care physicians can provide to their patients [ 13 ].

Barriers to seeking and providing care

Only four papers were summarized in this thematic category that explored what the literature says about barriers for seeking and providing care for physicians suffering from mental health concerns. Based on our analysis, we identified two levels of factors that can impact access to mental health care among physicians and physicians-in-training.

Individual level barriers stem from intrinsic barriers that individual physicians may experience, such as minimizing the illness [ 21 ], refusing to seek help or take part in wellness programs [ 14 ], and promoting the culture of stoicism [ 27 ] among physicians. Another barrier is stigma associated with having a mental illness. Although stigma might be experienced personally, literature suggests that acknowledging the existence of mental health concerns may have negative consequences for physicians, including loss of medical license, hospital privileges, or professional advancement [ 10 , 21 , 27 ].

Structural barriers refer to the lack of formal support for mental wellbeing [ 3 ], poor access to counselling [ 6 ], lack of promotion of available wellness programs [ 10 ], and cost of treatment. Lack of research that tests the efficacy of programs and interventions aiming to improve mental health of physicians makes it challenging to develop evidence-based programs that can be implemented at a wider scale [ 5 , 11 , 12 , 18 , 20 ].

Our analysis of the existing literature on mental health concerns in physicians and physicians-in-training in North America generated five thematic categories. Over half of the reviewed papers focused on proposing solutions, but only a few described programs that were empirically tested and proven to work. Less common were papers discussing causes for deterioration of mental health in physicians (20%) and prevalence of mental illness (16%). The literature on the effects of mental health concerns on physicians and patients (13%) focused predominantly on physicians with only a few linking physicians’ poor mental health to medical errors and decreased patient satisfaction [ 3 , 4 , 16 , 24 ]. We found that the focus on barriers for seeking and receiving help for mental health concerns (4%) was least prevalent. The topic of burnout dominated the literature (76%). It seems that the nature of physicians’ work fosters the environment that causes poor mental health [ 1 , 21 , 31 ].

While emphasis on burnout is certainly warranted, it might take away the attention paid to other mental health concerns that carry more stigma, such as depression or anxiety. Establishing a more explicit focus on other mental health concerns might promote awareness of these problems in physicians and reduce the fear such diagnosis may have for doctors’ job security [ 10 ]. On the other hand, utilizing the popularity and non-stigmatizing image of “burnout” might be instrumental in developing interventions promoting mental wellbeing among a broad range of physicians and physicians-in-training.

Table 2 summarizes the key findings from the reviewed literature that are important for our understanding of physician mental health. In order to explicitly summarize the gaps in the literature, we mapped them alongside the areas that have been relatively well studied. We found that although non-empirical papers discussed physicians’ mental wellbeing broadly, most empirical papers focused on medical specialty (e.g. neurosurgeons, family medicine, etc.) [ 4 , 8 , 15 , 19 , 25 , 28 , 35 , 36 ]. Exclusive focus on professional specialty is justified if it features a unique context for generation of mental health concerns, but it limits the ability to generalize the findings to a broader population of physicians. Also, while some papers examined the impact of gender on mental health [ 7 , 32 , 39 ], only one paper considered ethnicity as a potential factor for mental health concerns and found no association [ 4 ]. Given that mental health in the general population varies by gender, ethnicity, age, and sexual orientation, it would be prudent to examine mental health among physicians using an intersectional analysis [ 30 , 32 , 39 ]. Finally, of the empirical studies we reviewed, all but one had a cross-sectional design. Longitudinal design might offer a better understanding of the emergence and development of mental health concerns in physicians and tailor interventions to different stages of professional career. Additionally, it could provide an opportunity to evaluate programs’ and policies’ effectiveness in improving physicians’ mental health. This would also help to address the gap that we identified in the literature – an overarching focus on proposing solutions with little demonstrated evidence they actually work.

This review has several limitations. First, our focus on academic literature may have resulted in overlooking the papers that are not peer-reviewed but may provide interesting solutions to physician mental health concerns. It is possible that grey literature – reports and analyses published by government and professional organizations – offers possible solutions that we did not include in our analysis or offers a different view on physicians’ mental health. Additionally, older papers and papers not published in English may have information or interesting solutions that we did not include in our review. Second, although our findings suggest that the theme of burnout dominated the literature, this may be the result of the search criteria we employed. Third, following the scoping review methodology [ 2 ], we did not assess the quality of the papers, focusing instead on the overview of the literature. Finally, our research was restricted to North America, specifically Canada and the USA. We excluded Mexico because we believed that compared to the context of medical practice in Canada and the USA, which have some similarities, the work experiences of Mexican physicians might be different and the proposed solutions might not be readily applicable to the context of practice in Canada and the USA. However, it is important to note that differences in organization of medical practice in Canada and the USA do exist, as do differences across and within provinces in Canada and the USA. A comparative analysis can shed light on how the structure and organization of medical practice shapes the emergence of mental health concerns.

The scoping review we conducted contributes to the existing research on mental wellbeing of American and Canadian physicians by summarizing key knowledge areas and identifying key gaps and directions for future research. While the papers reviewed in our analysis focused on North America, we believe that they might be applicable to the global medical workforce. Identifying key gaps in our knowledge, we are calling for further research on these topics, including examination of medical training curricula and its impact on mental wellbeing of medical students and residents, research on common mental health concerns such as depression or anxiety, studies utilizing intersectional and longitudinal approaches, and program evaluations assessing the effectiveness of interventions aiming to improve mental wellbeing of physicians. Focus on the effect physicians’ mental health may have on the quality of care provided to patients might facilitate support from government and policy makers. We believe that large-scale interventions that are proven to work effectively can utilize an upstream approach for improving the mental health of physicians and physicians-in-training.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

United States of America

World Health Organization

Ahmed N, Devitt KS, Keshet I, Spicer J, Imrie K, Feldman L, et al. A systematic review of the effects of resident duty hour restrictions in surgery: impact on resident wellness, training, and patient outcomes. Ann Surg. 2014;259(6):1041–53.

Article Google Scholar

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Atallah F, McCalla S, Karakash S, Minkoff H. Please put on your own oxygen mask before assisting others: a call to arms to battle burnout. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(6):731.e1.

Baer TE, Feraco AM, Tuysuzoglu Sagalowsky S, Williams D, Litman HJ, Vinci RJ. Pediatric resident burnout and attitudes toward patients. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):e20162163. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2163 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Blais R, Safianyk C, Magnan A, Lapierre A. Physician, heal thyself: survey of users of the Quebec physicians health program. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(10):e383–9.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Brennan J, McGrady A. Designing and implementing a resiliency program for family medicine residents. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;50(1):104–14.

Cass I, Duska LR, Blank SV, Cheng G, NC dP, Frederick PJ, et al. Stress and burnout among gynecologic oncologists: a Society of Gynecologic Oncology Evidence-based Review and Recommendations. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143(2):421–7.

Chan AM, Cuevas ST, Jenkins J 2nd. Burnout among osteopathic residents: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2016;116(2):100–5.

Chaukos D, Chad-Friedman E, Mehta DH, Byerly L, Celik A, McCoy TH Jr, et al. Risk and resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):189–94.

Compton MT, Frank E. Mental health concerns among Canadian physicians: results from the 2007-2008 Canadian physician health study. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(5):542–7.

Cunningham C, Preventing MD. Burnout. Trustee. 2016;69(2):6–7 1.

PubMed Google Scholar

Daskivich TJ, Jardine DA, Tseng J, Correa R, Stagg BC, Jacob KM, et al. Promotion of wellness and mental health awareness among physicians in training: perspective of a national, multispecialty panel of residents and fellows. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(1):143–7.

Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: a potential threat to successful health care reform. JAMA. 2011;305(19):2009–10.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Epstein RM, Krasner MS. Physician resilience: what it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):301–3.

Evans RW, Ghosh K. A survey of headache medicine specialists on career satisfaction and burnout. Headache. 2015;55(10):1448–57.

Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, Sharek PJ, Lewin D, Chiang VW, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7642):488–91.

Fargen KM, Spiotta AM, Turner RD, Patel S. The importance of exercise in the well-rounded physician: dialogue for the inclusion of a physical fitness program in neurosurgery resident training. World Neurosurg. 2016;90:380–4.

Gabel S. Demoralization in Health Professional Practice: Development, Amelioration, and Implications for Continuing Education. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2013 Spring. 2013;33(2):118–26.

Google Scholar

Govardhan LM, Pinelli V, Schnatz PF. Burnout, depression and job satisfaction in obstetrics and gynecology residents. Conn Med. 2012;76(7):389–95.

Jennings ML, Slavin SJ. Resident wellness matters: optimizing resident education and wellness through the learning environment. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1246–50.

Keller EJ. Philosophy in medical education: a means of protecting mental health. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(4):409–13.

Krall EJ, Niazi SK, Miller MM. The status of physician health programs in Wisconsin and north central states: a look at statewide and health systems programs. WMJ. 2012;111(5):220–7.

Lemaire JB, Wallace JE. Burnout among doctors. BMJ. 2017;358:j3360.

Linzer M, Bitton A, Tu SP, Plews-Ogan M, Horowitz KR, Schwartz MD, et al. The end of the 15-20 minute primary care visit. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1584–6.

Lu DW, Dresden S, McCloskey C, Branzetti J, Gisondi MA. Impact of burnout on self-reported patient care among emergency physicians. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(7):996–1001.

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422.

McClafferty H, Brown OW. Section on integrative medicine, committee on practice and ambulatory medicine, section on integrative medicine. Physician health and wellness. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):830–5.

Miyasaki JM, Rheaume C, Gulya L, Ellenstein A, Schwarz HB, Vidic TR, et al. Qualitative study of burnout, career satisfaction, and well-being among US neurologists in 2016. Neurology. 2017;89(16):1730–8.

Peterson J, Pearce P, Ferguson LA, Langford C. Understanding scoping reviews: definition, purpose, and process. JAANP. 2016;29:12–6.

Przedworski JM, Dovidio JF, Hardeman RR, Phelan SM, Burke SE, Ruben MA, et al. A comparison of the mental health and well-being of sexual minority and heterosexual first-year medical students: a report from the medical student CHANGE study. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):652–9.

Ripp JA, Privitera MR, West CP, Leiter R, Logio L, Shapiro J, et al. Well-being in graduate medical education: a call for action. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):914–7.

Salles A, Mueller CM, Cohen GL. Exploring the relationship between stereotype perception and Residents’ well-being. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(1):52–8.

Shiralkar MT, Harris TB, Eddins-Folensbee FF, Coverdale JH. A systematic review of stress-management programs for medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):158–64.

Sikka R, Morath J, Leape L. The quadruple aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(10):608–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004160 .

Tawfik DS, Phibbs CS, Sexton JB, Kan P, Sharek PJ, Nisbet CC, et al. Factors Associated With Provider Burnout in the NICU. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):608. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-4134 Epub 2017 Apr 18.

Turner TB, Dilley SE, Smith HJ, Huh WK, Modesitt SC, Rose SL, et al. The impact of physician burnout on clinical and academic productivity of gynecologic oncologists: a decision analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146(3):642–6.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272.

Williams D, Tricomi G, Gupta J, Janise A. Efficacy of burnout interventions in the medical education pipeline. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):47–54.

Woodside JR, Miller MN, Floyd MR, McGowen KR, Pfortmiller DT. Observations on burnout in family medicine and psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):13–9.

World Health Organization. (2001). Mental disorders affect one in four people.

World Health Organization. Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice (Summary Report). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Not Applicable

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Telfer School of Management, University of Ottawa, 55 Laurier Ave E, Ottawa, ON, K1N 6N5, Canada

Mara Mihailescu

School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, ON, N2L 3G1, Canada

Elena Neiterman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.M. and E.N. were involved in identifying the relevant research question and developing the combinations of keywords used in consultation with a professional librarian. M.M. performed the literature selection and screening of references for eligibility. Both authors were involved in the creation of the literature extraction tool in Excel. Both authors coded the data inductively, first independently reading five articles and generating themes from the data, then discussing their coding and developing a coding scheme that was subsequently applied to ten more papers. Both authors then refined and finalized the coding scheme and M.M. used it to code the rest of the data. M.M. conceptualized and wrote the first copy of the manuscript, followed by extensive drafting by both authors. E.N. was a contributor to writing the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mara Mihailescu .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mihailescu, M., Neiterman, E. A scoping review of the literature on the current mental health status of physicians and physicians-in-training in North America. BMC Public Health 19 , 1363 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7661-9

Download citation

Received : 29 April 2019

Accepted : 20 September 2019

Published : 24 October 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7661-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Mental illness

- Medical students

- Scoping review

- Interventions

- North America

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Recommendation 22 Literature Review Summary

- Mental health literacy encompasses knowledge about mental health symptoms, interventions, and resources available, as well as positive attitudes and willingness to intervene when others are struggling.

- Literacy campaigns targeted at mental health have been positively received in post-secondary institutions, though it is unclear how they might affect behavioural outcomes.

- Mental health training can improve knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy. However, improvements often diminish over time, and it is unclear how actual gatekeeping behaviours are affected.

- Barriers to participating in training programs include lack of awareness, time constraints, resource limitations, and uncertainty about the benefits of training.

Literature Review Findings

Mental health literacy is broadly defined as knowledge of mental health symptoms, interventions, and resources available, as well as positive attitudes and self-efficacy toward helping others in need. Many students were aware of counselling services and symptoms related to depression, but fewer recognized other campus resources and types of mental health conditions. Health promotion and prevention of mental health issues were under-recognized; students only endorsed help-seeking actions when symptoms were severe. Additionally, students experiencing high levels of depression and distress were less likely to recognize symptoms of mental illness than others.

Various mental health literacy campaigns have been implemented in post-secondary settings. Feedback collected through focus groups and surveys tended to be positive, though response rates were often low and outcomes following exposure were minimal. Campaigns utilizing visual promotion materials are more effective when they are designed appealingly and with a student audience in mind. There is also a need for campaigns targeted at groups at higher risk of experiencing mental distress, such as LGBTQ+ and racialized student groups.

Mental health training programs are associated with short-term increases in self-reported knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy. However, there is mixed evidence supporting changes to actual behaviours; (quasi-)experimental studies found few differences in skills following training. Training programs that included components such as experiential learning exercises and scenarios tailored to post-secondary settings were the most effective at improving outcomes. Limitations of studies on training programs include low participation and response rates, lack of long-term follow-up assessments, and the use of instruments that have not been empirically validated.

Faculty, staff and students described barriers to participating in training programs, such as lack of awareness about training opportunities, limited time and resources, and uncertainty about the benefits of training given the role of the person. Support from peers and leaders in the community was a strong enabling factor for participating in training.

Implications for Practice

Mental health literacy campaigns need to be embedded into a larger policy and service framework that emphasizes health promotion and prevention as well as intervention and crisis management. Tailored campaigns for high risk groups, such as minority student populations and those experiencing high levels of mental distress, are recommended.

As part of a mental health literacy strategy, training programs need to be available to all members of the university community. Training programs that are specialized for post-secondary settings, incorporate experiential exercises, and which receive institutional resources and ongoing support, are likely to have the most impact.

- Contact Waterloo

- Maps & Directions

- Accessibility

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations .

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 75, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.307-398

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 75, NO. 3 pp.203-304

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 75, NO. 2 pp.107-201

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 75, NO. 1 pp.1-71

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

E-Mental Health: A Rapid Review of the Literature

- Shalini Lal , Ph.D. , and

- Carol E. Adair , Ph.D.

Search for more papers by this author

The authors conducted a review of the literature on e-mental health, including its applications, strengths, limitations, and evidence base.

The rapid review approach, an emerging type of knowledge synthesis, was used in response to a request for information from policy makers. MEDLINE was searched from 2005 to 2010 by using relevant terms. The search was supplemented with a general Internet search and a search focused on key authors.

A total of 115 documents were reviewed: 94% were peer-reviewed articles, and 51% described primary research. Most of the research (76%) originated in the United States, Australia, or the Netherlands. The review identified e-mental health applications addressing four areas of mental health service delivery: information provision; screening, assessment, and monitoring; intervention; and social support. Currently, applications are most frequently aimed at adults with depression or anxiety disorders. Some interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in early trials. Many believe that e-mental health has enormous potential to address the gap between the identified need for services and the limited capacity and resources to provide conventional treatment. Strengths of e-mental health initiatives noted in the literature include improved accessibility, reduced costs (although start-up and research and development costs are necessary), flexibility in terms of standardization and personalization, interactivity, and consumer engagement.

Conclusions

E-mental health applications are proliferating and hold promise to expand access to care. Further discussion and research are needed on how to effectively incorporate e-mental health into service systems and to apply it to diverse populations.

Innovations in information and communication technology (ICT) are transforming the landscape of health service delivery. This emerging field, often referred to as “e-health,” includes key features, such as electronic, efficient, enhancing quality, evidence based, empowering, encouraging, education, enabling, extending, ethics, and equity ( 1 ). E-health is a broader concept than telehealth (and telemedicine), which involves the use of ICT to connect patients and providers in real time across geographical distances ( 2 ) for the delivery of typical care and where the use of real-time video is the main modality ( 3 ).

Interest is also increasing in the application of ICT in mental health care. For example, the first international e-mental health summit was held in 2009 in Amsterdam, and a summit-specific issue of the Journal of Medical Internet Research was published ( 4 ). Christensen and colleagues ( 5 ) defined e-mental health as “mental health services and information delivered or enhanced through the Internet and related technologies.” However, there is no agreement on a field-specific definition. Some scholars consider e-mental health to include only initiatives delivered directly to mental health service users ( 6 ) and only on the Internet ( 6 , 7 ) (as opposed to, for example, delivery via stand-alone computers or video seminars). Others adopt a wider definition that includes frontline delivery activities related to screening, mental health promotion and prevention, provision of treatment, staff training, administrative support (for example, patient records), and research ( 4 ).

Because of the growth of the e-mental health field, it is difficult for policy makers and practitioners to stay abreast of available applications and the evidence for their effectiveness. In response to a request from a Canadian executive-level policy maker, we conducted a rapid review of the literature on e-mental health. In this article, we report briefly on the review methods and summarize key findings.

Rapid reviews are an emerging type of knowledge synthesis used to inform health-related policy decisions and discussions, especially when information needs are immediate ( 8 – 11 ). Rapid reviews streamline systematic review methods—for example, by focusing the literature search ( 8 ) while still aiming to produce valid conclusions. The requirements for the review, which was undertaken with a two-week deadline, were for a short (maximum eight pages) but in-depth synthesis of the current state of the science on the topic. The personnel available was one senior (doctoral-level) mental health services researcher (CEA). Later, a second (doctoral-level) mental health services researcher (SL) validated the conclusions by screening all titles and abstracts, extracting and synthesizing additional data, and reviewing the findings.

The overarching review question was: What is currently known on the topic of e-mental health? (Even though telepsychiatry is typically included in e-mental health definitions, we did not include this subtopic because its literature is already well developed with several systematic reviews and reviews of reviews.)

Several secondary questions were developed and refined as the review progressed: What types of e-mental health initiatives have been developed? What are the strengths and benefits of e-mental health? What are the concerns with and barriers to use of e-mental health? What is the state of the evidence for the effectiveness of e-mental health? How has e-mental health been integrated in service systems and policy?

The rapid review method used is similar to Khangura and colleagues’ ( 10 ) seven-step process. Briefly, the search focused on English, peer-reviewed full abstracts in MEDLINE from 2005 to 2010 and used the MESH terms mental disorders and internet and the following non-MESH key words: e-mental health, e-therapy, computer, computer-based therapy, computer-based treatment, web-based therapy, web-based treatment. We excluded search terms related to telehealth because that is a distinct, and well-established subset of the e-health field that mainly considers the use of telecommunications to connect service providers and patients across geographical distances ( 3 ) (as opposed to delivering automated, self-management interventions, for example). The search was run in MEDLINE because of time constraints and because it is the most widely searched database for health-related topics, has comprehensive coverage (more than 5,500 journals), and has substantial capture of the content of health services research and overlap with similar sources.

The initial search (December 2010) yielded 158 titles or abstracts. Similar keywords were also used in a brief on-line grey literature search, which retrieved additional relevant documents, such as a list of in-progress trials, a policy report, and recent conference proceedings. Two experts on e-mental health were also contacted by e-mail for comment on the appropriateness of the identified literature and additional articles. Final searches focused on the work of prominent authors (for example, Christensen, Hickie, and Titov). These searches yielded an additional 50 titles and abstracts, resulting in 208 titles and abstracts screened for duplicates and relevancy.

Further details on the rapid review method and our search and selection strategy are provided in an online data supplement to this article.

General description of the literature

The screening process resulted in 115 documents, which were reviewed. Of these, 108 (94%) had been peer reviewed. Publication dates were from 2000 to 2010, with most (N=91, 79%) published between 2007 and 2010, which confirmed an expected increase in the volume of literature on the topic over time. Of the 115 documents, 59 (51%) reported primary empirical studies, of which 25 (42%) were conducted in the United States, 13 (22%) in Australia, and seven (12%) in the Netherlands.

Types of e-mental health initiatives

The review identified e-mental health applications addressing four areas of mental health service delivery: information provision ( 6 , 12 ); screening, assessment, and monitoring ( 13 – 20 ); intervention ( 21 – 24 ); and social support ( 25 ). Many applications addressed several areas of mental health service delivery concurrently ( 26 – 29 ). [A table listing examples of these e-mental health programs and initiatives is provided in the online data supplement . It summarizes information on the purpose of the application, the health conditions and populations targeted, and the components and technologies used.]

With respect to information provision, there is an identified need to ensure the quality of information about mental health. Therefore, tools such as the Brief DISCERN ( 13 ) have been developed to help users assess the quality of mental health–related content on Web sites.

Screening and assessment tools have been available for many years on stand-alone computers, but more recent developments are Internet-based screening tools to provide broader access to individuals for self-assessment (particularly to underserved or hard-to-reach groups) or for use by professionals in specific settings (for example, primary care) ( 30 ). For example, Diamond and colleagues ( 16 ) described an Internet-based behavioral health screening tool for adolescents and young adults in primary care. It requires minimal time to complete; addresses a broad spectrum of psychiatric symptoms, risk behaviors, and patient strengths; is automatically scored online; and allows results to be integrated into the patient’s electronic medical record and into system-level performance measurement.

Social support in e-mental health occurs through several types of Web-based formats, including discussion groups, bulletin boards, chat rooms, blogs, and social media. For example, Scharer ( 25 ) reported on a pilot study that examined the effectiveness of an online electronic bulletin board to provide social support to parents of children with mental illness. Parents made use of the bulletin board over a four-month period, actively posting messages to each other about their children’s illness or about the group.

E-mental health interventions were classified in our review by stage (promotion, prevention, early intervention, active treatment, maintenance, and relapse prevention), type of relationship (for example, between a professional and a consumer, between consumers, and between professionals), and treatment or therapy modality (for example, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT] and psychoeducation). Treatments identified were self-led or led by a therapist or were a combination (for example, self-led and therapist guided). Interventions were provided as the primary therapy or adjunct to conventional in-person therapy and were delivered to individuals or groups or both. For example, MoodGYM is an exemplary Web-based, interactive intervention that has been developed and evaluated in several randomized controlled trials ( 27 , 31 – 33 ). Its purpose is to enhance coping skills in relation to depression, and it includes assessments, workbooks, games, online exercises, and feedback. MoodGYM is freely available to the public and has been translated into several languages.

Most of the interventions studied were situated on a specific point of the continuum of care (for example, prevention, mental health promotion, or intervention) and used a single format; however, a few incorporated several types of approaches. For example, Tillfors and colleagues ( 34 ) investigated whether an Internet-delivered self-help intervention in conjunction with minimal e-mail contact was as effective as adding in-person group sessions to the Internet intervention. They found that adding in-person group sessions did not result in significant differences in outcomes.

Typically, e-mental health interventions mimicked traditional treatment approaches in that they often addressed single disorders; none were designed for individuals with comorbid mental and substances use disorders. The most frequent disorders addressed by the 59 empirical studies were depression or anxiety (18 studies, 31%). Several interventions focused on mental health promotion or prevention, including early identification (eight studies, 14%). Most interventions were developed specifically for adults (40 studies, 68%), followed by interventions targeting adolescents or young adults (11 studies, 19%). Recent e-mental health initiatives reflect the shift in the mid-2000s to Web 2.0 technologies (that is, more interactive, multimedia, and user-driven technologies) ( 35 ).

Strengths and benefits

Many authors believe that e-mental health has enormous potential to address the gap between the identified need for mental health services in the population and the limited capacity and resources to provide conventional treatment services ( 13 , 30 ). Strengths of e-mental health initiatives noted in the literature include improved accessibility, reduced costs (although start-up and research and development costs are necessary), flexibility in terms of standardization and personalization, interactivity, and consumer engagement ( 5 , 30 , 34 – 38 ). E-health technologies are considered to be particularly promising for rural and remote populations. They are also promising for subpopulations that have other barriers to access (attitudinal, financial, or temporal) or that avoid treatment because of stigma. For example, by using Internet-based social support, individuals can share their perspectives freely while preserving their anonymity. Further details and examples of benefits are summarized in a box on the next page.

Concerns and barriers

Some concerns and barriers are associated with using e-mental health. There are concerns that e-mental health will replace important and needed conventional services; divert attention away from improvements to or funding for conventional services; and be costly to develop, deploy, and evaluate ( 5 ). Another issue raised in the literature is related to the financial interests of developers and researchers, which may produce a risk of publication bias ( 39 ). Others have highlighted the limited evidence base for interventions, lack of quality control and care standards, and slow uptake by or reluctance among health care professionals ( 39 , 40 ). Some question the ability of professionals to establish therapeutic relationships on line and the feasibility of online treatment for certain population groups (for example, patients with severe depression) ( 39 ). Emmelkamp ( 39 ) described “technological phobia,” whereby professionals may be unfamiliar with technology and anxious about its use in professional care. Concerns have also been expressed about the potential to further marginalize individuals who have physical, financial, or cognitive barriers in terms of access to conventional services. Finally, some are concerned that the availability of e-mental health services may lead some individuals to postpone seeking needed conventional care or that some will receive inappropriate or harmful care when there is insufficient quality control over content ( 7 ).

Ethical and liability concerns have been cited. For example, when participants are from outside the regulatory jurisdiction, ethical responsibilities cannot be met; other concerns are that participants cannot be reliably identified and that privacy cannot be guaranteed for typed or recorded communications ( 5 , 34 , 37 , 38 , 41 ). To address these issues, several professional organizations (for example, the American Psychological Association) have developed guidelines ( 38 ), and an international organization to set standards has been established—the International Society for Mental Health Online. Even so, adherence has been found to be lacking, and concerns remain ( 7 , 39 , 42 , 43 ). At the same time, remedies for the above-mentioned concerns are emerging. Technology for the protection of security and confidentiality has improved, and some efforts are being made to review Web site content for quality ( 35 , 44 , 45 ). In Australia, a Web portal called Beacon has been set up that provides quality ratings for mental health Web sites and recommends evidence-based interventions ( 46 ).

Consumer engagement, reach, and response

A handful of recent studies have shed some light on the role of e-mental health providing prevention or intervention programming for particular groups of individuals, such as youths, socioeconomically diverse populations, rural and remote populations, the general public, and patients. One study investigated the preferences for e-mental health services in an online Australian sample (N=218) ( 47 ). Among individuals in the general population who were already using the Internet, a large majority (77%) expressed a preference for face-to-face services, but less than 10% indicated that they would not use e-mental health services. The authors highlighted the importance of raising public awareness, knowledge, and understanding about e-mental health services. More than 50% of the sample expressed the need to learn more about e-mental health services and about issues related to confidentiality.

More than 90% of youths now use the Internet, and it is seen as a promising medium for reaching that age group ( 28 , 48 ). In a large population-based sample of 2,000 young people aged 12 to 25 in Australia, 77% reported seeking information about mental health problems whether or not they had the problem themselves ( 49 ). In another study among military personnel, who are predominantly younger males, one-third of 352 respondents who reported that they were not willing to talk to a counselor in person indicated that they would be willing to use technology to address their concerns ( 50 ).

Preliminary research has also indicated that mental health service users value the use of e-mental health. A qualitative study of 36 participants found that their primary motive for Internet use was to access social support and their secondary motive was for information ( 51 ). Respondents noted that hearing about other individuals’ experiences helped them to feel less isolated and more hopeful. Respondents also liked the convenience, privacy, and anonymity of the Internet. On the other hand, several authors have documented low access to and use of the Internet among persons with more serious mental illnesses, such as those with co-occurring substance use and serious mental illness ( 52 , 53 ). Cost, lack of training, and impairment (in cognition, concentration, executive function, and motor control) can present barriers for individuals with serious mental illness, further disenfranchising them from services ( 54 ). However, evidence is emerging that with a user-friendly interface, high levels of engagement and positive outcomes can be obtained in online interventions for individuals with serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and their families ( 26 ). Nonetheless, access to and attitudes toward technology, as well as socioeconomic factors, need to be taken into account in planning Internet-based interventions for specific population groups ( 55 ).

Evidence base for e-mental health

Although evaluation of some interventions is limited, an encouraging amount of rigorous research is available, depending on the developmental stage of the intervention. Research on Web-based interventions has both opportunities and challenges. Studies are relatively inexpensive to conduct, and large samples can be used. Interventions are easily standardized, randomized or controlled designs are feasible (often with wait list controls), and data are easily collected. Challenges include low rates of completion because of the relative ease with which participants can drop out of studies. In addition, it is difficult to study both the intervention and the mode of delivery; contamination of the control group is possible because participants can access similar services elsewhere on the Web; the ability to conduct double-blind studies is limited; and biases related to using self-report measures are a problem ( 56 – 58 ). Increasingly, resources for optimizing practice and evaluation are available; for example, guidelines for program design and for study methods have been published ( 36 , 59 ).

In the past five years, several reviews, including systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials, have documented the progress made; effectiveness has been demonstrated in particular for interventions (both therapist assisted and self-directed) addressing depression and anxiety disorders ( 57 , 59 , 60 ). For example, a systematic review of meta-analyses of the efficacy of Internet-based self-help for depression and anxiety disorders reported that these interventions are effective and that effect sizes are comparable to those observed in similar interventions delivered in person ( 60 ). Systematic reviews of Internet-based CBT interventions (prevention and treatment) for anxiety and depression among adults have found that they are as effective as or more effective than treatment as usual ( 57 ). Preliminary evidence has also been reported for the effectiveness of Internet-based interventions to address issues such as stress, insomnia, and substance abuse ( 61 ). There are still some interventions for which evidence is weak or contrary, such as one CBT-based program for individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder ( 62 ), and not all studies evaluating the effectiveness of Internet-based interventions for depression and anxiety have found positive results ( 62 , 63 ). Lower effect sizes have generally been found for interventions targeting alcohol and smoking cessation compared with those for anxiety and depression ( 61 ). There are some indications that programs work best for individuals with mild to moderate disorders; however, this group has been the focus of most research. Despite the popularity of online support groups, concerns about the encouragement of maladaptive behaviors, or support for continuing such behaviors, have surfaced—for example, in a recent survey of members of an eating disorders forum ( 64 ).

Systematic reviews are also beginning to appear that address e-health interventions for children and youths. For example, Stinson and colleagues ( 65 ) found that symptoms improved in seven of nine identified self-management interventions. A recent narrative review of Internet-based prevention and treatment programs for anxiety and depression among children and adolescents concluded that there was early support for effectiveness but a need for more rigorous research as well as interventions specifically targeting children ( 66 ). Recent innovations, such as those that embed prevention and early-intervention content in online games, need more evaluation. A study of one such program found a nonsignificant worsening effect on support seeking, avoidance, and resilience outcomes, especially among males ( 29 ). An interactive fantasy gaming approach has also been developed by Sally Merry, M.D., of Auckland, New Zealand (personal communication, Merry S, Dec. 2010). A recently published randomized controlled trial demonstrated its effectiveness among adolescents seeking help for depression in primary care settings ( 67 ).

In the area of substance use and abuse, a systematic review of Internet-based interventions for young people found small positive effects for programs aimed at alcohol abuse; the effects were of similar magnitude to those of brief in-person interventions, but the Internet-based interventions had the advantage of much broader delivery ( 68 ). However, programs aimed at preventing subsequent development of alcohol-related problems among those who were nondrinkers at baseline were generally not effective.

More research is needed on individual or subgroup predictors of differential outcomes of e-mental health interventions ( 21 , 69 ). Moreover, even though there is some preliminary evidence supporting the lower cost of using e-mental health approaches, true cost-effectiveness studies are just beginning to appear in the literature ( 70 ).

E-mental health, systems, and policy

Most of the literature reviewed described the development, implementation, and evaluation of single interventions in isolation. One very important question that has been given limited attention is how e-mental health interventions might best be situated in relation to an array of related services for a broad population. In a rare exception, van Straten and colleagues ( 71 ) discussed a stepped-care approach for depression in primary care wherein interventions advance from watchful waiting through self-guided but supported intervention (including Web-based formats), brief face-to-face psychotherapy, and finally longer-term face-to-face psychotherapy with consideration of antidepressant medication. To ensure continuity of care, a care manager monitors patient status at all levels and makes decisions about necessary transitions. Treatments at all levels are evidence based. These authors described trials of two different e-mental health interventions, including one for younger adults, and most important, how they fit within the full stepped-care model. Data on cost-effectiveness of the full model are unavailable, but the authors suggested that the incidence of new cases of depression and anxiety could be halved by introducing this model.

Andrews and Titov ( 72 ) described the promotion of Internet-based treatment programs (a virtual clinic) connected to a hospital in Sydney, Australia. The programs are considered to be cost-effective alternatives to medication or face-to-face CBT treatment. Programs are offered for major depression, social phobia, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Programs are available free or at very low cost directly to the public; general practitioners and other mental health professionals can use these programs in addition to or instead of conventional care. Trial results show high levels of patient adherence and strong reductions in symptoms with very little investment of clinician time. The authors discuss how e-mental health programs might fit in a broader health service delivery context (for example, in U.S. health maintenance organizations, health care trusts in the United Kingdom, and regional health authorities in Canada). They suggest that the programs could be the first level of treatment for the proportion of the population that desires Internet-based treatment; however, with the support of a small team, individuals who need more support could be identified and referred for more intensive intervention.

An approach that reaches out to the total population but that is not fully connected to conventional services has been described by Bennett and colleagues ( 27 ). At its center is “e-hub,” which is an online self-help mental health service available free to the public. The service provides automated Web interventions for several needs, such as symptoms of depression, anxiety, and social anxiety, and an online bulletin board. Programs focus on the prevention and early-intervention end of the spectrum. There is no therapist involvement in the interventions, and the bulletin board is moderated by trained consumers under the supervision of a clinical psychologist. Interested individuals can contact the e-hub by e-mail. The organizers report a high volume of use by individuals with and without mental disorders, some over a lengthy period. The service is considered most suitable for those who prefer to receive help anonymously, prefer self-help, or reside in rural or remote areas. Quality control processes are included.

No peer-reviewed articles had a central focus on policy-level discussions about e-mental health. However, the gray literature search yielded one major report on the topic from Australia, E-Mental Health in Australia: Implications of the Internet and Related Technologies for Policy ( 5 ). Although the report was published in 2004, much of the content is relevant for other countries, because many are only at the beginning stages of e-mental health implementation. The report describes the advantages of e-mental health initiatives and barriers to implementation (as described above). Five major recommendations for moving forward are included related to access, ethical issues, quality and effectiveness, technology, and funding.

Articles and studies identified by the rapid review but not discussed here are listed in References ( 73 – 103 ).

The purpose of this rapid review was to synthesize and describe what is currently known on the topic of e-mental health. On the basis of the findings, several considerations for future research and practice in the field of e-mental health are evident. First, it is important to consider the fit of e-mental health initiatives within the context of the existing service system and to ensure that they complement—and not detract from—needs for direct care. Second, it is important to select interventions and initiatives on the basis of available evidence regarding both design features and effectiveness and to build research and evaluation into any new initiatives. Third, it is important to consider the needs of the population as well as the greatest potential for benefit when choosing or investing in e-mental health initiatives—for example, the intervention’s suitability for a diverse group of participants (in age, ethnocultural status, literacy, and disability) should be considered. Fourth, it is important to ensure that ethical and quality issues are addressed. Fifth, the extent to which interventions have or can be applied in cross-cultural and international contexts is an important consideration. Sixth, the involvement of consumers, as well as other relevant key stakeholder groups (such as families and caregivers, service providers, and policy makers), in the development and deployment of initiatives is paramount. Seventh, further research is needed in relation to conditions other than common disorders, such as psychotic disorders. Eighth, more rigorously conducted research is needed, such as randomized controlled trials, and it is important to understand which groups of individuals will benefit the most from such interventions and to take into account cross-cultural and international factors (for example, cultural adaptations).

It is important to acknowledge the limits of rapid review. They include focusing the search on one electronic database source (although we used the database that contains by far the largest number of health and medical journals). The search was also complemented by gray literature searches on the Internet, focused author searches, and brief key-informant consultations. A second limitation of our review is that only one author (CEA) initially screened the titles and abstracts from the total set of documents retrieved, although this author is knowledgeable about the content area and has experience conducting systematic reviews. However, the second author (SL) rescreened all extracted titles and abstracts from the total set. This rescreening uncovered additional nuances in various content areas, identified further studies for review, and provided the opportunity for incorporating more detailed information in this article (for example, technologies and components of e-mental health initiatives described in the online data supplement ). Some minor errors in the initial review were also uncovered. Although the initial review was well received by its sponsors and was reported to inform key policy discussions, the effectiveness of rapid reviews in terms of their ultimate impact on health policy decisions and service outcomes remains to be systematically considered.

This rapid review identified a small but rich set of information on the topic of e-mental health, which was found to be highly useful for its specific intended policy discussion. The apparent promise and pitfalls of e-mental health and the increasing interest of policy makers in its potential for service system transformation indicate that careful monitoring of the evidence base is warranted.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

While conducting this review, Dr. Lal was partially supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from Knowledge Translation Canada. Dr. Adair conducted the initial review while under contract with the Mental Health Commission of Canada. The authors acknowledge Jayne Barker, Ph.D., and Janice Popp, M.S.W., for their assistance in refining the research questions to serve a policy purpose. The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors.

The authors report no competing interests.

1 Eysenbach G : What is e-health? Journal of Medical Internet Research 3:E20, 2001 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

2 Sood S, Mbarika V, Jugoo S, et al. : What is telemedicine? A collection of 104 peer-reviewed perspectives and theoretical underpinnings . Telemedicine and e-Health 13:573–590, 2007 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

3 Wade VA, Karnon J, Elshaug AG, et al. : A systematic review of economic analyses of telehealth services using real time video communication . BMC Health Services Research 10:233, 2010 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

4 Riper H, Andersson G, Christensen H, et al. : Theme issue on e-mental health: a growing field in Internet research . Journal of Medical Internet Research 12:e74, 2010 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

5 Christensen H, Griffiths K, Evans K : E-Mental Health in Australia: Implications of the Internet and Related Technologies for Policy . Canberra, Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, 2002 Google Scholar

6 Lambousis E, Politis A, Markidis M, et al. : Development and use of online mental health services in Greece . Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 8(suppl 2):51–52, 2002 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

7 Ybarra ML, Eaton WW : Internet-based mental health interventions . Mental Health Services Research 7:75–87, 2005 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

8 Watt A, Cameron A, Sturm L, et al. : Rapid reviews versus full systematic reviews: an inventory of current methods and practice in health technology assessment . International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 24:133–139, 2008 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

9 Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H : Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews . Implementation Science 5:56, 2010 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

10 Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, et al. : Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach . Systematic Reviews 1:10, 2012 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

11 Konnyu KJ, Kwok E, Skidmore B, et al. : The effectiveness and safety of emergency department short stay units: a rapid review . Open Medicine 6:e10–e16, 2012 Medline , Google Scholar

12 Santor DA, Poulin C, LeBlanc JC, et al. : Online health promotion, early identification of difficulties, and help seeking in young people . Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 46:50–59, 2007 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

13 Khazaal Y, Chatton A, Cochand S, et al. : Brief DISCERN, six questions for the evaluation of evidence-based content of health-related Websites . Patient Education and Counseling 77:33–37, 2009 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

14 Becker J, Fliege H, Kocalevent R-D, et al. : Functioning and validity of a Computerized Adaptive Test to measure anxiety (A-CAT) . Depression and Anxiety 25:E182–E194, 2008 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

15 Chinman M, Hassell J, Magnabosco J, et al. : The feasibility of computerized patient self-assessment at mental health clinics . Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 34:401–409, 2007 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

16 Diamond G, Levy S, Bevans KB, et al. : Development, validation, and utility of Internet-based, behavioral health screen for adolescents . Pediatrics 126:e163–e170, 2010 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

17 Donker T, van Straten A, Marks I, et al. : A brief Web-based screening questionnaire for common mental disorders: development and validation . Journal of Medical Internet Research 11:e19, 2009 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

18 Gringras P, Santosh P, Baird G : Development of an Internet-based real-time system for monitoring pharmacological interventions in children with neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders . Child: Care, Health and Development 32:591–600, 2006 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

19 Gualtieri CT : An Internet-based symptom questionnaire that is reliable, valid, and available to psychiatrists, neurologists, and psychologists . Medscape General Medicine 9:3, 2007 Medline , Google Scholar

20 Heron KE, Smyth JM : Ecological momentary interventions: incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments . British Journal of Health Psychology 15:1–39, 2010 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

21 Spek V, Nyklícek I, Cuijpers P, et al. : Predictors of outcome of group and Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy . Journal of Affective Disorders 105:137–145, 2008 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

22 Bergström J, Andersson G, Ljótsson B, et al. : Internet- versus group-administered cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder in a psychiatric setting: a randomised trial . BMC Psychiatry 10:54, 2010 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar