Iliad Summary and Analysis of Books 5-8

Athena temporarily gives Diomedes , son of King Tydeus of Argos, unmatched battle prowess. Diomedes battles fiercely, and Athena convinces Ares that they both should stand aside and let the mortals battle it out on their own. The battle is fierce, deaths reported by the speaker, as different Trojans and Greeks fight. Diomedes is hit by one of Pandarus' arrows. His friend Sthenalus tends to the wound, and Diomedes prays for revenge. Athena gives him another wave of strength, as well as a special gift: the mist is lifted from his eyes, and he can now temporarily recognize the gods fighting among the mortals. Athena warns him to face no god head-on, unless it is Aphrodite . Diomedes leaps into battle, slaughtering warrior after warrior.

Aeneas , Trojan warrior and mortal son of Anchises and Aphrodite, asks Pandarus to strike Diomedes down with an arrow, but Pandarus despairs of having failed to kill both Menelaus and Diomedes. Aeneas urges him to ride with him in his chariot to strike down Diomedes. The two men charge for the Achaean hero, and Sthenalus urges Diomedes to retreat. He does not, reminding Sthenalus that if they win they'll take the chariot and horses as a prize. Trojan horses are the world's finest, given to Troy by Zeus , and Aeneas' horses are particularly good specimens. Pandarus is killed, but before Diomedes can kill Aeneas, Aphrodite whisks him away. Aeneas' chariot is captured by the Greeks. Aphrodite is wounded by Diomedes and drops her son, but Apollo picks him up and carries him away. With the help of Iris and Ares' chariot, the wounded Aphrodite returns to Olympus. She complains to her mother, Dione, about what has happened to her. Dione reminds her of times when other immortal gods have had to suffer at the hands of mortals. She comforts her with the knowledge that no mortal who fights the gods gets away with it. Hera and Athena mock Aphrodite, and Zeus comforts her.

Apollo tries to carry Aeneas to safety, but three times Diomedes makes a fierce attack on Apollo. On the fourth try, Apollo warns him in a terrifying voice not to defy the gods. Diomedes backs down. Apollo carries Aeneas to his temple, where the goddesses Leto and Artemis tend to him, and Apollo makes a doppleganger of Aeneas to replace him temporarily in battle. Apollo urges Ares to stop Diomedes. Ares takes mortal form to rally the Trojans. Sarpedon , a Trojan ally, insults Hector and goads him into new heights of valor. Hector rallies the troops, and Apollo brings Aeneas back from his temple, fully healed. The battle rages, more killings described by Homer , and Ares now aids Hector. Diomedes, because of Athena's gift, can see the god, and so he warns the Achaeans to fall back. Battles follow, including a notable encounter in which Hector wounds Odysseus . Hector drives the Achaeans back, and Hera, watching the battle, tells Athena that they must stop Ares. The goddesses prepare for battle. Hera takes mortal form to rally the Argives. Athena goes to stand beside Diomedes, telling him that because Ares has broken his vow to leave the battlefield she will help Diomedes to bring him down. Diomedes and Athena wound Ares, who ascends to Olympus and complains to Zeus. Zeus scolds and insults him, but calls for a healer. Hera and Athena, satisfied, return to Olympus.

The gods choose champions, but their decisions are not arbitrary. The will of the gods in this case has something to do with the characters of mortals. Diomedes is the chosen champion of Athena; he is not beloved for nothing, but because he is a strong warrior, faithful to the gods and loyal to his commander. We first saw him in the last book, when he patiently bore the abuse of Agamemnon and encouraged Sthenalus to do the same. This brief moment establishes his character's loyalty and respect for the chain of command, preparing us for his re-introduction in this section as the chosen champion of the goddess Athena.

With gods behind them, single warriors seem worth more than whole armies. Diomedes smashes through the Trojan ranks with Athena's help, just as later Hector drives the Achaeans back with Ares by his side. Homer writes not exactly of real men, but of heroes. (It was the work of the Athenian tragedians centuries later to tear Homer's heroes down to human scale.) His vision of battle is one where single men, when inspired or chosen, can drive back the entire opposing army. In Homer, war is not pure chaos or mass violence; war is an arena in which individual warriors make all the difference. The armies fail or succeed because of the actions of single men. Homer glorifies the place of an individual's valor and strength.

His heroes are of a stronger race of men: many times throughout the Iliad, men perform astonishing feats of strength. Diomedes wounds Aeneas by throwing a giant boulder at him, "a huge thing which no two men could carry / such as men are now, but by himself he lightly hefted it" (5. 303-4). (Incidentally, this line shows that either Homer was writing long after the events he was supposedly portraying or at least that there are lines that were added to the Iliad long after the supposed time of the Trojan War.) Homer writes about a heroic past, one where men are supposedly stronger than any living during Homer's own time. Homeric heroes talk to gods, and are chosen by them; with some help, they can even fight against the gods on the battlefield and win.

Aeneas is one of the gods' favorites. Both Aphrodite and Apollo are determined that he should not die, spiriting him away and shielding him with their own bodies. He is destined to be one of the few survivors of Troy, and, long after Homer's time, the Romans claimed descent from him. Aeneas' treatment reveals how single-minded the gods can be once they have made a decision; or, alternatively, his treatment shows how the gods must act under the dictates of fate.

We see here gods who can be wounded. They bleed ichor, blood of the gods, but they cannot die. Greek divinities have limits on their power: although Aprhodite is unmatched in the realm of love (her power will later master Zeus himself) in battle she is vulnerable. On the other hand, it is impossible for a mortal to oppose a god without divine help. Aphrodite is an exception because she has no battle prowess, but even in her case Diomedes wounds her after he has been given great strength by Athena. And when Diomedes wounds Ares, he is only able to do so because Athena drives and directs the spear.

The brutal fighting continues, with more blow-by-blow description of the battle. At one point, Menelaus overcomes Adrestus and is about to kill him, but the man catches Menelaus by the knees (position of the suppliant) and begs for his life. A customary alternative to slaying an enemy is capturing him and holding him for ransom. Menelaus is about to do as the young man asks, but Agamemnon tells his brother that they are here to kill the Trojansall of them, until no trace of their people remains on the earth. Menelaus kills him, and Nestor calls out to the men to waste no time on plunder: they shall kill now, and loot the bodies later at their leisure.

Helenus, son of Priam and a skilled seer, tells Hector and Aeneas that they must rally the troops lest the soldiers are driven back through the gates. He also tells Hector to return to Troy and gather all of the elder noblewomen together to make a special sacrifice at the temple of Athena. They must pray to the goddess to hold back Diomedes. Hector does as his brother asks.

Glaucos , of the Lycians (Trojan allies), comes face to face with Diomedes in battle. Diomedes asks who he is, not wanting to fight against a god, and, in grand epic fashion, Glaucos recounts his genealogy and the deeds of his ancestors. Diomedes realizes that their families have a history of friendship, and the two agree to be friends. They will avoid each other on the battlefield, since there are plenty of other warriors for the two of them to kill. They swear an oath of friendship and a permanent open offer of hospitality, exchanging armor to seal the oath. Diomedes, however, gets the better end of the deal: Diomedes gets Glaucos' golden armor, while Glaucos is stuck with Diomedes' bronze armor.

Meanwhile, Hector goes back into the city, where all of the women come running around him to ask about their fathers, sons, husbands, brothers, and friends. His only response is to tell them to pray. He enters the palace of Priam, the layout of which is described here briefly, and he meets his mother Hecuba and his sister Laodice. His mother wants him to rest and offer prayer, but Hector brushes aside her requests and gives her the instructions of Helenus. The old noblewomen make the offering as instructed, but when the priestess prays that Diomedes might be defeated and Troy saved, Athena turns her head away. The women then pray to Zeus himself.

Meanwhile, Hector searches for Paris , with whom he is increasingly angry. He finds Paris gearing up for battle. He harshly rebukes his brother, but Paris makes excuses for himself and his lateness, saying that he will soon be ready to return to battle. He is gearing up now on the urges of his wife Helen . Helen, disgusted and angry with Paris, asks Hector to rest for a moment. Hector refuses and goes to see his wife and son. He cannot find them in the house, but a servant informs him that his wife Andromache has gone to watch the fighting from atop the city walls. Andromache is attended by a nurse who carries Hector's infant son. Hector goes back to the Scaean Gates, searching for her, and Andromache rushes to meet him there. She weeps for fear that Hector's status as the greatest Trojan warrior will mean his death. She has lost both parents and all her brothers, her father and seven brothers all killed by Achilles in previous campaigns. She wants Hector to stay away from the front lines and set up a defensive force for blocking a weak point in the city walls. He refuses, and tells her that he must not be called a coward; he must win glory for himself and his line. He also confides in her that he knows Troy will fall. The thought that troubles him most is that Andromache will be hauled away and made captive in a Greek man's house; he will die before he hears the sound of her being dragged away. He holds his infant son, praying for the child to one day rule and be greater than his father. Andromache goes back into their house, where she and the handmaidens mourn for Hector, because they do not expect to see him alive again.

Paris meets up with Hector near the gates, and Hector takes a softer tone with his brother than before. He recognizes that Paris, when he does fight, is a capable warrior, but explains that he cannot stand it when Paris hangs back from battle. Hector then speaks wishfully of a day when the Achaeans will be driven away forever and the Trojans can give thanks to the gods.

This section orders and structures events in a moving and powerful way. There are three important events in Book 6: the consideration and then rejection of Adrestus' plea for mercy, the meeting on the battlefield between Glaucos and Diomedes, and the return of Hector to the city. The structure creates some remarkable effects. The first part establishes the level of brutality with which this war will be fought. It emphasizes that there will be no mercy for the Trojans, and the Achaeans are fighting a war that will end in the destruction of a whole people. With that fact established, the third part is emotionally wrenching. Hector, beloved of his people, is returning to look on a city that will be no more. The characters and people of Troy, depicted in this section with great sympathy, are doomed. The second important event, the interaction and exchange between Glaucos and Diomedes, creates a space for non-martial virtues in the midst of war. The poignancy of an offer of friendship in the middle of a battlefield provides relief from the gruesome descriptions of combat and warriors' deaths. The friendship between Diomedes and Glaucos suggests an alternative course of action for the peoples for whom they are fighting, but the other events of this section make it clear that this alternative will not be pursued. These three events reward a closer look.

Agememnon brings us face to face with one of the Iliad's themes. The brutality of men, even noble men, on both sides, shows us that this war was not fought with mercy or restraint. Although Menelaus considers Adrestus' pleas for mercy, his more bloodthirsty brother convinces him that they are here to bring total destruction on the people of Troy. Nestor's announcement moments later is not accidental: he drives the Achaeans to forsake looting the bodies for now. Once all of the Trojans are dead, he argues, they can loot at their leisure. By this point, even an audience unfamiliar with the myth knows without a shred of ambiguity that for the Trojans defeat means annihilation. If the Achaeans are defeated, they return home and suffer dishonor and the pain of wasted effort. The Trojans, if defeated, pay a much higher price. The Acheans have come not to conquer, but to destroy.

This chilling opening sequence is relieved by the exchange between Glaucos, a Lycian ally of the Trojans, and Diomedes. Amidst the brutality of war, these two men carve out a small space for more gentle values. The realization that their families have a history of friendship motivates the men to come to a separate peace between the two of them. The fact that Glaucos is Lycian rather than Trojan gives him a chance to actually survive the war. The scene is beautiful, affirming a place for friendship even under the most extreme and violent conditions imposed by war. However, the end puts a twist on the exchange: has Diomedes intentionally swindled Glaucos out of his golden armor? It is improbable that the proposal of friendship was a way for Diomedes to get a pricier suit of armor; after all, as champion of Athena, Diomedes probably could have killed Glaucos and taken the armor. But the possibility remains that Diomedes has swindled a man to whom he has just proposed friendship, complicating this short scene. It is as if the war makes it difficult to create any pure space for the gentler virtue of friendship. Even when swearing solemn oaths of friendship and making a separate peace, Glaucos would have been better off if he had kept his wits about him.

Within the city walls of Troy, the Trojans are depicted with tremendous sympathy. The concern of the women for the fighting men is poignant; there is also something deeply saddening about the moment in the temple when Athena refuses to heed their desperate prayers. Although the Trojans are not of the same culture as the Achaeans, Homer has made them worship the same gods. The plan of the palace and Priam's number of sons makes it clear that the royal family is in the style of the Near East rather than Greece, but the city would still have been recognized by Greece as a powerful symbol of civilization and its benefits. Civilization here is made fragile, shown to be vulnerable before more brutal forces. They are a pious people; Zeus has said earlier that their offerings are rich and constant. They are also a compassionate people. The elders and especially Priam treat Helen better than she deserves, and she knows it. But the Trojans are also a doomed people, and Homer is no romanticist about the relations between states. Troy is home to a refined civilization with a gentle and pious citizenry, but brute strength is the only way to protect oneself from an invader.

We are also given a much richer characterization of Hector. Note that although Helenus is the prince who knows what must be done to stop Diomedes, Hector is the man with the authority and stature to carry out Helenus' plan. And when Hector returns through the Scaean Gates, the women of Troy turn to him for comfort and news. He is the man to whom his people turn for support; at a few words from him, the women pray for Troy as ordered. Helen also holds him in esteem, and the contrast between the ridiculous, self-absorbed Paris and his tougher brother could not be clearer. There is also a strong contrast between the flawed marriage of Paris and Helen and the deep bond between Andromache and Hector. In Andromache's lament, there is foreshadowing of Hector's destiny. Like all of the other men close to Andromache, he will fall before Achilles in battle. Here, we see that Hector knows that his city is doomed, but he must go on. We see him as a great husband and father, a compassionate man full of love and devotion to his city. Despite some deep foreboding that Troy is lost, he prays that his son might grow to greatness. This moment has greater weight because earlier in Book 6 Agamemnon has made clear that not even the unborn will survive. At the end of Book 6, standing beside his cowardly brother Paris, Hector faces the battlefield and speaks words of hope, although by now the audience knows that there is none.

Paris and Hector return to battle with renewed determination, and Glaucos, too, fights fiercely. Seeing their strength, Athena comes down from Olympus to aid the Achaeans. Apollo intercepts her, proposing that they bring about peace for a day. He proposes that Hector call for one of the Achaeans to meet him is single combat. Athena agrees, and Apollo proposes the idea to Hector. Hector comes between the ranks and gives the command for his men to seat themselves, and Agamemnon does likewise with the Achaean soldiers. Hector proposes that a man meet him in single combat. The loser will be stripped of his armor, which will be a trophy for the victor, but the body will be given proper respect and burial. No one meets the challenge initially, so Menelaus takes the offer. Homer reveals here that Menelaus would certainly have died if Agamemnon had not interceded. Agamemnon convinces his brother that to fight Hector is madness, and Menelaus sits down. Nestor scolds the Achaeans, telling a story of his own valor from the days of his youth, and in response nine men step forward: Agamemnon, Diomedes, the two Aeantes, Idomenus , Meriones , Eurypylos, Thoas, and Odysseus. Nestor has them throw lots, and Great Ajax wins. After trading words, Hector and Ajax fight. The two men fight fiercely, and Ajax seems to be winning, but the fight is stopped by the heralds Idaios and Talthybios, messengers of Zeus and of mortals. They argue that night is falling and that Zeus loves both men, and therefore the duel should stop. The two men stop fighting, trade gifts, and return to their sides.

That night, after sacrifices and feasting, Nestor suggests that they burn their dead and build fortifications. Among the Trojans, Antenor tells Paris that he should give back Helen and all of the other treasures he stole from the house of Menelaus. Paris refuses, suggesting instead that he give back the treasures he stole from Menelaus (except for Helen) plus other valuables from among his own goods. Priam wants to send messengers relaying Paris' offer and also asking for a temporary truce so that both sides can bury their dead. In the morning, the herald Idaeus carries out Priam's orders. Diomedes responds that the Achaeans should not accept Paris' giftseven if he should offer Helen. The Trojans must die. The troops cry out their agreement with him. Agamemnon heeds his men but grants the temporary truce. Both sides, with great sorrow, bury their dead. The Achaeans take advantage of the truce and build a great wall, along with a ditch and a line of sharpened stakes, and on Olympus Poseidon objects that in building the wall they have dedicated no offering to the gods. Zeus promises him that once the war is over Poseidon can destroy the wall. That night, shipments of wine come to the Achaeans from Euneus, son of Jason, and the Achaeans drink. Zeus plans horror for them, however, and the Achaeans can feel it. They pour wine in offering to Zeus and are unable to celebrate freely.

Although the fight between Ajax and Hector ends in a technical draw, the direction of the duel clearly indicates that Hector would have lost. Throughout the Iliad, it is clear that the best Achaean warriors are far greater than their Trojan counterparts. From among their ranks there are a number of mighty fighters, including Agamemnon, Diomedes, the Aeantes, Odysseus, Patroclus , and of course, Achilles. On the Trojan side, the champions include Sarpedon, Aeneas, and Hector, but none of the great Trojan warriors gets through the Iliad without being soundly defeated by an Achaean champion. Even when the Trojans are winning, the victory is somehow qualified. This pattern reflects Homer's pride in the heroes of his own culture, but it may also reflect the fact that many members of the nobility in Homer's audience traced their ancestry to various Achaean heroes in the Iliad. The epic had to include celebration of these heroes in order for Homer to please his crowd.

Hector's pride (activated by Apollo's suggestion) leads him to suggest the duel for no purpose other than the pursuit of glory. But we see here also the force of Hector's personality. When he orders his men to sit down, putting himself in a dangerous position between the two armies, we see the power of his charisma in action. Agamemnon, himself a mighty king, follows Hector's lead. Hector is respected not only by the Trojans, but by the Achaeans as well. Although he is more vulnerable on the battlefield than Ajax or Achilles, as a leader his charisma is unmatched.

Zeus calls the gods to assembly and warns them not to take part in the Trojan War; any god who does so will be hurled into Tartarus, a deep pit far below Hades. Zeus himself descends to the earth and watches the battle, and at midday he shifts the balance of war to favor the Trojans. He also throws his lightning and terrifies the Achaean soldiers, who begin to retreat. Nestor becomes stuck when one of the horses drawing his chariot has been wounded, and Hector closes in for the kill. Diomedes sees Nestor's plight and calls to the fleeing Odysseus, who does not heed him. Diomedes rescues Nestor, taking him into his own chariot and trusting Nestor's horses to two henchmen. The two men charge Hector, and Diomedes spears Hector's chariot driver. Hector finds a new charioteer and the two great warriors seem prepared to clash, but Zeus's lightning strikes the ground between them. Nestor tells Diomedes that Zeus clearly no longer favors him, and they must flee. Diomedes is anxious about fleeing from Hector, but he is persuaded by Nestor's arguments. Zeus sends thundering signs from the mountain of Ida to let the Trojans know that the tide of war favors them. Hector calls out to his men, saying that they shall overcome the fortifications and burn the ships of the Achaeans, but first they must win Nestor's shield and Diomedes armor. Hera, watching from Olympus, is angered, but she is unable to persuade Poseidon that the gods should unite, overrule Zeus, and aid the Achaeans.

Hector is raging forward, pinning the Achaeans behind their own fortifications, and Agamemnon, stirred by Hera, tries to rally the troops. The commander-in-chief is horrified by the defeats being dealt to his men, and prays, weeping, to Zeus. Zeus heeds his prayer, sending an eagle with a fawn in its talons. The fawn releases the eagle by the altar the Achaeans built for Zeus, and so the Achaeans take heart and turn to fight the Trojans. Teucer , Great Ajax's half-brother and master archer, strikes down warrior after warrior with his arrows, taking occasional shelter behind his brother's massive shield. He cannot hit Hector, however, though he kills Hector's chariot driver. Hector leaps down and throws a great rock at Teucer, injuring him badly. With Great Ajax providing cover, he is carried back to the ships. Hector drives the Achaeans back behind their fortifications again.

Hera fumes with Athena over the fate of the Achaeans, and Athena tells Hera that they should both prepare for battle. As they come down from Olympus, Zeus sends Iris to warn them that if they do not turn back, Zeus will harm Athena horribly. Hera speaks first, saying that the two goddesses should leave the mortals to their fate rather than allow an immortal to be harmed, and so they return, grieving for the men whom they cannot help. Zeus returns to Olympus also, where Hera and Athena sit apart and plan pain for the Trojans. Hera and Zeus exchange harsh words, but Zeus promises that Hector will have even greater victory until the death of Patroclus stirs Achilles to rejoin the fight.

Night falls, and Hector proposes that they light fires and watch the Achaeans, so as to attack them if they try to escape. The people of the city should light fires and keep careful watch as well, because the army will be camped on the field. Hector is sure that the next day will bring great victories, including the death of Diomedes. The Trojans sacrifice oxen and sheep, but, unbeknownst to the Trojans, the gods do not partake of the offerings.

It is established here that no god can oppose Zeus. Even if the Olympians were to band together, he would still be able to overpower them. We also see more of Hera's and Athena's unreasoning hatred of Troy, the motivation for which is never explained in a satisfactory way. In Book 24, the beauty contest of the goddesses and Paris' fateful decision is offered as the reason for Athena's and Hera's hate, but by then the contest seems frivolous compared to the scale of carnage in the Trojan War. For Poseidon, once forced to toil in a humiliating manner under Laomedon, Priam's father, a more understandable motive exists, but the two goddesses are far more constant defenders of the Achaean forces.

But now we see Hector at the height of his strength, backed by Zeus, turning back the Achaeans, almost, as Homer depicts it, single-handedly. It would be a mistake to say that Hector is the least proud of the heroes of the Iliad; as Lattimore has pointed out, Hector's pride takes the form of a great fear of looking like a coward. We have seen other instances of pride. In Book 7, he risks himself in a duel with Ajax for the sake of pure glory; here in Book 8 he is determined not only to win, but to heap ignominy on the Achaeans should they try to escape. He is now fully confident in his ability to beat the Argives, boastfully wishing that his becoming immortal were as certain as the great defeat he is about to deal against the Achaeans. But Homer tells us at the end of Book 8 that the gods do not accept the sacrifice of the Trojans. Even as the Trojans reach their high tide, we are reminded of their certain destruction.

Iliad Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Iliad is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Nestor seems like a minor character in The Iliad, but he actually plays a significant role in the development of the epic’s plot. What are some of the ways in which the aged king propels the action of the story? What effect does he have on the epic as a w

Nestor seems like a minor characterin the iliad but he actually plays a significants role in the development of the epics plot. What are some of the ways in which the aged king propels the action of the story? What affects does he have on the epic...

Which side does the warrior Diomedes fight for during the Trojan War?

Diomedes fights against the Trojans in the war.

Identify the speaker and context of the following quotation in Homer's epic.

Hector utters these words when Achilles hurls his spear to kill Hector and misses.

Study Guide for Iliad

Iliad study guide contains a biography of Homer, literature essays, a complete e-text, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Iliad

- Iliad Summary

- Character List

- Books 1-4 Summary and Analysis

Essays for Iliad

Iliad literature essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Iliad.

- To Obey or Disobey: The Role of Obedience in the Iliad and Genesis 1-25

- Criteria for Heroes

- The Success of King Priam's Request

- The Consistency of Cruelty in Combat

- Homeric Formalism

Lesson Plan for Iliad

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to Iliad

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- Iliad Bibliography

E-Text of Iliad

Iliad E-Text contains the full text of Iliad

- Books 13-16

- Books 17-20

Wikipedia Entries for Iliad

- Introduction

- Greek gods and the Iliad

- Date and textual history

The Iliad Book 5 Summary

- In order to make sure the Trojans get a good thumping, Athene gives extra power and courage to Diomedes.

- In the heat of the battle, Diomedes is approached by two Trojans, Phegeus and Idaios. We are told that these guys are the sons of some guy called Dares, who is a priest of the god Hephaistos (we met this god back in Book 1 ).

- Phegeus and Idaios throw their spears at Diomedes but both miss.

- When Diomedes throws his spear, however, he kills Phegeus. He would kill Idaios too, except that the god Hephaistos swoops down from the sky and carries the Trojan to safety. Hephaistos does this so the boys' father will not be completely heartbroken at losing two sons.

- Elsewhere on the battlefield, Athene convinces Ares to back off for a while and let the mortals duke it out for themselves. Ares—who's apparently a pushover—agrees.

- Various gruesome depictions of warfare follow. When a character is killed, we usually get a little backstory on where they come from, what they do in peacetime, etc.

- Meanwhile, Diomedes is seriously on the warpath.

- Pandaros, the Trojan archer, decides to take Diomedes out. He lets fly an arrow and hits him in the right shoulder.

- Proud of his shot, Pandaros urges the Trojans on.

- Diomedes calls Sthenelaos to come pull out the arrow. Sthenelaos is happy to oblige.

- After the arrow has been removed, Diomedes prays to Athene to be able to spear the guy who shot him.

- Athene comes to him, tells him she has instilled his father's strength in him. As an added bonus, she also takes away the mist from his eyes, so that he can tell who's a mortal and who's a god. She tells him that if any god challenges him, he should maintain eye contact and back away slowly. Any god, that is, except for Aphrodite. Athene tells Diomedes that if he sees the goddess of love, he should go on the attack.

- Diomedes roars back into action, and kills various opponents.

- Meanwhile, the Trojan warrior Aineias (you can read more about his subsequent adventures in Virgil's Aeneid —or on Shmoop's coverage of the Aeneid ) is looking for Pandaros.

- When he finds him, Aineias says, "Why don't you take another shot at Diomedes?"

- Archers can be a prickly bunch, however, and now Pandaros gets all defensive. He says that some god must be helping Diomedes. Then he starts complaining about the bad luck he's been having—it's not even lunchtime, he's already shot Menelaos and Diomedes, and they're both still alive.

- Aineias suggest they team up in one chariot. That way, they can speed in for an attack against Diomedes, and then easily speed back out again if the going gets rough.

- Pandaros says, "You've got yourself a deal. You drive, I'll spear."

- When Aineias and Pandaros are getting in range of Diomedes, Sthenelaos catches sight of them and warns the Achaian warrior.

- Diomedes says, "No worries. You go for the horses, I'll take out one of these jokers."

- Just at that moment, Pandaros starts taunting Diomedes, and throws his spear at him. Once again, however, Pandaros is close but no cigar. The spear goes through Diomedes's shield but fails to pierce his breastplate.

- When Diomedes throws his own spear, he hits Pandaros in the face, killing him.

- To protect his fallen comrade, Aineias leaps down from his chariot. Seeing his chance, Diomedes picks up a huge rock and throws it at Aineias. It crushes his hip and he sinks to the ground.

- Now Diomedes is going in for the kill. Luckily for Aineias, however, his mommy is there to protect him. This is lucky because his mom just happens to be the goddess Aphrodite. She wraps him in her cloak to protect him from enemy weapons, and starts to carry him away.

- While Sthenelaos steals the fallen Trojans' horses, Diomedes uses his Athene-brand super-vision and attacks Aphrodite, stabbing her in the wrist.

- Because Aphrodite is incapacitated, Apollo swoops down, wraps Aineias in a mist of invisibility, and continues carrying him to safety.

- In the meantime, Diomedes mocks Aphrodite for her generally meddlesome nature.

- Without even making a comeback, Aphrodite flees the scene. Iris, the messenger of the gods, comes down to lead her to safety on Mount Olympos.

- Once she gets there, Aphrodite runs into her mother, Dione, and complains about her rough treatment at the hands of Diomedes. She is astonished that the Achaians dare to make war on the gods!

- Dione, who's been around the block a few times, doesn't think it's such a big deal. She reminds Aphrodite of past occasions in which gods have suffered physical violence at the hands of mortals.

- Then, Dione wipes the ichor (this is what gods have instead of blood) from Aphrodite's wrist and heals her wound.

- Now that the injury is healed, it's time for some insult. Hera and Athene start making fun of Aphrodite in front of Zeus.

- Zeus tells Aphrodite she was asking for it, and should stay away from fighting in the future.

- Back on the battlefield, Diomedes is still going after Aineias, who is still being carried off by the god Apollo.

- Apollo successfully defends Aineias from Diomedes's attacks, and issues the Achaian warrior a stern warning not to mess with the gods.

- Diomedes backs off and Apollo successfully ferries Aineias out of the battle, and deposits him in his own temple on a sacred mountain. There Apollo's mother and sister, the goddesses Leto and Artemis, heal Aineias's wounds.

- So that nobody suspects anything, Apollo creates a ghostly replica of Aineias which he sends down to keep fighting. The Trojans rally around this replica.

- Now Apollo calls on Ares, god of war, to go after Diomedes. Apollo enters the fray and incites the Trojans to keep on slugging.

- At this point, Sarpedon, the commander of the Lykians, a tribe allied with the Trojans, starts taunting Hektor because he isn't in the thick of the action. Sarpedon says, "We Lykians are busting our butts for you Trojans; how come you aren't putting in some effort for yourselves?"

- Hektor feels like he just got burned. He jumps out of his chariot and starts whipping his men into order, and leads them on a counterattack.

- Now Apollo sends the real Aineias—who by this point is fully recovered—back into the battle.

- Everyone is too busy to ask him what happened.

- The battle rages on. Losses are suffered on both sides.

- Suddenly, Menelaos rejoins the battle.

- Meanwhile, Ares is sticking close by Hektor, protecting him from harm and helping him kick some tail.

- Because Diomedes can see the god helping Hektor, he warns the other Achaians to steer clear of the Trojan hero.

- In the midst of the fray, there is an encounter between two warriors who are both descended from Zeus. Tlepolemos, who is fighting for the Achaians, is the son of Herakles (better known by his Roman name, Hercules), and is therefore Zeus's grandson. Sarpedon, whom we've already met, is Zeus's son.

- These estranged relatives start by hurling insults at each other, and then graduate to hurling spears, both at the same time.

- Sarpedon hits Tlepolemos in the neck, killing him. Tlepolemos's spear hits Sarpedon in the thigh.

- While Sarpedon is helped off the scene by his entourage, the Achaians drag Tlepolemos's body back among their ranks.

- Now, Odysseus is wondering whether he should go after Sarpedon, or whether he should just attack the Lykians who serve under him. Because it isn't fated for Odysseus to kill Sarpedon, the goddess Athene makes him decide to give the Lykians a licking.

- Odysseus doesn't make much progress, however, because Hektor makes a counterattack against him.

- In the meantime, Sarpedon is carried off to safer ground, where his wound is dressed. His spirit briefly leaves his body, but then returns. He is alive.

- Understandably, the Achaians are backing away from the tag-team of Hektor and Ares, who are currently killing opponents left and right.

- Up on Olympos, Hera and Athene don't like the looks of this. They decide to put a stop to Ares's rampage themselves.

- In describing the goddesses' preparations, Homer not only includes a segment of Pimp My Chariot , but also works in an Extreme Makeover: Hoplite Warrior Edition .

- As the goddesses are riding away from Olympos, Hera asks for and receives Zeus's permission to whoop Ares's behind.

- Once they arrive on the ground, Hera starts insulting the Achaians to egg them on. Athene goes to find Diomedes, who is nursing his wound from Pandaros's arrow.

- Athene starts by insulting him, calling him a wuss and half the man his father was.

- Diomedes says, "I'm only hanging back because of what you said. You said don't fight any gods except for Aphrodite. I stabbed her alright, but now Hektor has Ares backing him up. What am I supposed to do?"

- Now Athene reveals her true colors: "Forget Ares," she says, "we can take him."

- Athene knocks Sthenelaos out of his chariot and mounts beside Diomedes. The two of them drive on towards Ares; Athene helps Diomedes spear the god in the gut.

- After letting out a shriek as loud as an entire army, Ares runs crying up to Olympos. There, he starts whining to Zeus about what Diomedes did to him. He also complains about how Athene helped out Diomedes.

- Zeus scolds him, basically saying, "You can dish it out but you can't take it."

- The king of the gods says he would have banished Ares long ago—he just has a soft spot for his son. He calls Apollo to come heal Ares's wounds.

- Then Hebe, the goddess of youth, washes Ares and decks him out with some stylish new duds. Ares sits down and relaxes.

- Hera and Athene come back to Olympos.

Tired of ads?

Cite this source, logging out…, logging out....

You've been inactive for a while, logging you out in a few seconds...

W hy's T his F unny?

Table of Contents

- Book 1: The Rage of Achilles

- Book 2: The Great Gathering of Armies

- Book 3: Helen Reviews the Champions

- Book 4: The Truce Erupts in War

- Book 5: Diomedes Fights the Gods

- Book 6: Hector Returns to Troy

- Book 7: Ajax Duels with Hector

- Book 8: The Tide of Battle Turns

- Book 9: The Embassy to Achilles

- Book 10: Marauding Through the Night

- Book 11: Agamemnon’s Day of Glory

- Book 12: The Trojans Storm the Rampart

- Book 13: Battling for the Ships

- Book 14: Hera Outflanks Zeus

- Book 15: The Achaean Armies at Bay

- Book 16: Patroclus Fights and Dies

- Book 17: Menelaus’ Finest Hour

- Book 18: The Shield of Achilles

- Book 19: The Champion Arms for Battle

- Book 20: Olympian Gods in Arms

- Book 21: Achilles Fights the River

- Book 22: The Death of Hector

- Book 23: Funeral Games for Patroclus

- Book 24: Achilles and Priam

Book 5 - Diomedes Fights the Gods

Diomedes' wild fight.

The fifth book begins by continuing to narrate the story of the battle that started when Pandarus broke the truce in Book 4. In the fourth book Agamemnon had implied that Diomedes was acting cowardly when he stood behind his troops. As this book begins we are told that Athena has granted Diomedes “strength and daring.” He consequently achieves a number of kills. He kills Phegus with his spear and would have killed his brother, Idaeus, except that Hephaestus carries him to safety. Their father, Dares, had been Hephaestus’s priest. Meanwhile, Athena asks Ares, the god of war, to keep out of the fighting and let the mortals fight it out. Ares sits out of the fight with Athena and the Achaeans begin to drive the Trojans back, as a series of hand-to-hand combats results in the deaths of several men.

But Diomedes stands out in this battle, fighting wildly so that it is difficult to see upon which side he fights. The Trojans panic under his attack. But Pandarus again uses his skill with the bow and wounds Diomedes in the shoulder. Diomedes calls for Sthenelus to withdraw the arrow from him. He does, and then Diomedes prays to Athena for the chance to kill Pandarus. In answer to his prayer Athena gives Diomedes the power to distinguish between mortals and gods on the battlefield. She warns him to fight none of the gods except Aphrodite. Diomedes returns to the fighting and is once again ferocious, killing several men, including a front line captain, Hypiron, as well as Abas and Polyidus and brothers Xanthus and Thoon, along with brothers Echemmon and Chromius. Aenaes, seeing what is happening, demands that Pandarus target Diomedes. Pandarus says he is unsure whether Diomedes is a man or god, but tells Aeneas that he fights with a god beside him. He explains he has already shot Diomedes. Pandarus regrets not following his father’s advice to bring a chariot to Troy. He has already wounded Menelaus and now Diomedes, and neither man has died. He feels his bow is worthless.

Diomedes Kills Pandarus

Aeneas offers Pandarus the choice to either drive his chariot or fight the Greeks hand to hand. Pandarus leaves Aeneas to drive the chariot, while he elects to fight hand to hand. Sthenelus sees Aeneas and Pandarus bearing down upon Diomedes in the chariot and gives him a warning. Diomedes refuses to retreat from the chariot, even though he is on foot. He tells Sthenelus that if he can kill Aeneas and Pandarus, he wants Sthenelus to steal Aeneas’s horses. Pandarus is emboldened when he sees Diomedes standing his ground. He thrusts at Diomedes with his spear and pierces his shield. But he fails to wound Diomedes. Diomedes throws a spear at Pandarus which hits him between the eyes and kills him. Aeneas, fearing Pandarus’s corpse will be taken, jumps from his chariot to protect it. But Diomedes throws a boulder at him, which breaks Aeneas’s hip, bringing him down.

Apollo Intervenes to Save Aeneas

Aeneas is saved by Aphrodite, his mother, who flings her robe in front of him to deflect weapons. Meanwhile, Sthenelus fulfils his promise to capture Aeneas’s horses, while Diomedes hunts Aphrodite through the battle. She is still protecting Aeneas when Diomedes wounds her with his spear in her wrist, causing her to drop Aeneas. Apollo immediately takes up Aeneas to protect him, and chastises Aphrodite, telling her to leave the battle. Iris leads her from the battle and she sees Ares sitting on a cloudbank with his horses. Aphrodite begs him to lend her the horses so she can return to Olympus. He does so and she returns to Dione, her mother. She tells Dione what has happened and seeks her comfort. Dione recalls other incidents when Ares, Hera and Hades suffered wounds at the hands of mortals, as well as Heracles’s attempt to shoot arrows at Olympus. She reflects that Diomedes will not have long to live if he attacks the gods. Dione heals Aphrodite’s wound. Hera and Athena, who see this, mock her to Zeus, suggesting that Aphrodite has been luring other Greek women to lust after Trojans. Zeus tells Aphrodite that she should not concern herself with matters of war. Meanwhile, on the battlefield, Diomedes sees that Apollo is protecting Aeneas, but even so he still attempts to kill him. Apollo warns Diomedes to back off. Diomedes retreats and Apollo sweeps Aeneas from the battle to the top of Mt Pergamus. There he heals Aeneas. Meanwhile, Apollo creates a copy of Aeneas so that the Trojans may gather around it and continue the fight. Back at the battle, Apollo tells Ares that Diomedes must be removed from the battle, since he is attacking gods and men alike. Instead, Ares wades into the battle to spur the Trojans on while Apollo returns to Pergamus.

The Battle Rages On

Sarpedon, a Trojan ally, taunts Hector, calling his family cowards because, except for Hector, they hide behind Troy’s walls while allies like Sarpedon fight with nothing personally to defend. Hector is shamed into action by Sarpedon and leads his men in a renewed resistance. Ares, wishing to help the Trojans, clouds the battle in night. Meanwhile, Apollo returns Aeneas to the battle, which raises the spirits of his men.

On the Achaean side, Diomedes and Odysseus spur the Greeks on to attack, while Agamemnon urges the men to be courageous, saying that courageous action, in this instance, is in fact safer. He makes his point by spearing Aeneas’s comrade in arms, Deicoon, whom he kills. Seeing this, Aeneas kills two Argive captains. Menelaus, in turn, bursts through the front line, driven on by rage encouraged by Ares, who hopes to see Menelaus killed by Aeneas. But Antilochus, fearing Menelaus will be killed – which would make the whole campaign pointless, since its stated purpose is to return Helen to Menelaus – enters the fight on Menelaus’s side. Aeneas is forced to drop back. Together, they now begin killing other Trojans, Pylaemenes, and Mydon, whom Antilochus runs down with his own horses and chariot after he falls when his elbow is hit by a rock, thrown by Antilochus. Hector, spotting them, rushes in with his shock troops backing him, and Diomedes perceives that Hector is now supported by Ares. He warns his troops not to engage Hector.

Hector kills Menesthes and Anchialus, and Greater Ajax defends their bodies. Ajax kills Amphius but fails to strip his body of armour due to the relentless attack of the Trojans. Meanwhile, Tlepolemus, Heracles’s son, taunts Sarpedon that he is no great fighter and not worthy of the great fighters who have preceded him: that his support will be of little consequence for Troy. Sarpedon is defiant against Tlepolemus’s taunts. The two men attack each other, but each receives a spear wound. Sarpedon is ushered from the battle and Tlepolemus is also carried away. Odysseus, frustrated that he cannot end Sarpedon, kills several men in a rage as he tries to get nearer. When Hector intervenes to stop Odysseus’s onslaught, Sarpedon begs him for protection. But Hector moves on and Sarpedon dies as the spear is removed from his flesh.

Athena Joins Diomedes Against Ares

Meanwhile, the Argives give ground under the onslaught of Hector and Ares. Seeing the deaths of several Argive solders, Hera urges Athena to act to stem the tide of Ares’ attack. Hera’s chariot is fitted out to take Athena into the battle. She mounts the chariot with Hera. As they are leaving Olympus they come across Zeus. Hera asks Zeus to not interfere if she strikes at Ares. Zeus agrees. Hera drives her chariot down to Troy and causes grass to grow beside the Simois River so that her horses might graze. She then speaks to the Greeks and shames them for their having given ground. She says that when Achilles fought no Trojans ventured from the gates of Troy: now they may get as far as the Greek ships.

While Hera speaks to the troops Athena finds Diomedes. He has given the order not to fight Hector and Ares. Athena reminds him of the glory of his father at Thebes, essentially trying to shame him into more action. But Diomedes points out that his inaction is due to her own command, that he should not engage any god in battle except for Aphrodite. So Athena now urges Diomedes to fight Ares. She says he promised to fight against the Trojans, yet here he is, now fighting on their side. Athena throws Sthenelus from the chariot so she can ride with Diomedes. They charge Ares as he strips Periphas of his armour. But Ares sees only Diomedes in the chariot, since Athena is wearing “the dark helmet of Death”, and he attacks back. But Diomedes, aided by Athena, gives Ares a terrible wound. He flees to Olympus where he shows Zeus his wound. He expresses his anger that Athena acts against him, and that Zeus does nothing about it. But Zeus is not willing to placate Ares. Zeus tells Ares that he hates him because he loves strife and battles. Zeus says that he only tolerates Ares in Olympus for the sake of his mother, Hera. Nevertheless, Zeus orders that Ares be healed. Hera and Athena returns to Olympus, having stopped Ares murderous rampage.

There is always a sense of the anthropomorphic nature of Greek gods. Not only do the gods engage in conflict between each other, but their interference in human affairs, as we see happening in The Iliad , means their stories are intertwined and that the conflict between gods is not only worked out in their own sphere, but the human world too. For a start, conflict between the gods is the catalyst for the whole Trojan campaign as we receive it according to the story told by Homer. Although the story of the judgement of Paris does not appear in The Iliad , and is only mentioned late in the poem, it was well known to ancient Greek audiences. In short, Paris was asked to judge the most beautiful of three goddesses, Athena, Aphrodite and Hera at a wedding, so that the winner might be given a golden apple which Eris, the goddess of discord, left at the wedding as revenge for not being invited. Aphrodite bribed Paris to win the contest by presenting him Helen, wife of Menelaus, which legend has it, is the casus belli for the Trojan War.

Book 5 of The Iliad illustrates, as no book has done before it, how the dispute of the gods is played out in the human world. The following notes on three characters attempts to consider the key characters a little beyond the surface of what the narrative immediately offers: that is, to deliberately read against the perspective the text seems to offer.

Ares and Diomedes

In Book 5 the story is primarily told from the perspective of certain characters: Athena and Diomedes, as well as Zeus late in the book. The narrative seems to privilege their discourse over that of Ares whom Zeus describes in a series of negative epithets as, “lying, two-faced” and “incorrigible”. Zeus abhors Ares for his love of “battles [and] the bloody grind of war” and says he has an “uncontrollable rage.”

For modern readers, Ares may represent the carnage and violence of war beyond the character, and this is certainly a well-supported reading, given the swathes of Greek and Trojan dead left lying side by side at the end of Book 4, and the chaotic and violent scenes portrayed in this book. What reasonable person would not abhor war? But as a character – someone with motivations which are complex and in conflict with others – rather than as an anthropomorphised state, Ares is less obviously to blame for what we are, on the surface, invited to believe is his fault.

At the start, his chaotic and destructive nature is initially better ascribed to Diomedes. Athena urges Ares to remain out of the conflict at the beginning of this book, suggesting that his involvement will heighten the stakes of the battle to a level of horror not normally expected even in ordinary warfare. As a result, Ares does sit it out. In fact, Book 5 begins by telling us that:

- Then Pallas Athena granted Tydeus’ son Diomedes

- strength and daring – so the fighter would shine forth

- and tower over the Argives and win himself great glory.

- She set the man ablaze, his shield and helmet flaming

- with tireless fire like the star that flames at harvest . . .

Diomedes, from the start, is an instrument of Athena. The power she gives him is meant to turn the tide of battle against the Trojans and asking Ares to sit it out means she wants Diomedes to wreak havoc unopposed. It is Diomedes who rages through the battle so fiercely that it is difficult to tell which side he fights upon. Ares acts because Apollo tells him that Diomedes needs to be removed from the battle, but instead of doing this, Ares chooses to support the Trojans, which only seems to escalate the bloodshed, especially when he lends his force to Hector. Ares actions in the latter half of the book seem to reflect the brutal fight that Diomedes engages in the earlier sections. Athena raised the stakes of the battle which brought Ares back to the conflict.

Hera’s determination that Ares needs to be stopped does not address the problem that Athena first set in motion this heightened conflict by favouring Diomedes. It is a point Ares makes himself when making an appeal to Zeus.

When Ares appeals to Zeus at the end of the book he makes a case that Athena is the real problem. Having been born from Zeus’s forehead she represents a part of Zeus’s power and intellect, so this is not a wise argument, even though it seems sound. He points out that Athena’s enabling of Diomedes is what heightened the conflict and caused the wounding of Aphrodite. But it is clear that Zeus despises Ares, whatever his arguments might be, which may be explained as displaced anger against Hera, Ares’s mother: “You have your mother’s uncontrollable rage”. Zeus will allow Ares to remain in Olympus for the sake of Hera, but it seems Ares’s position has been defined by a rage Zeus cannot openly express against his wife. It is an interesting psychological position. Since we see the conflict in Book 5 from the point of view of Diomedes and Athena, we are invited to see Ares as the real villain. But these insights provide a means by which we can read against the narrative.

Aphrodite is treated with an open level of contempt in Book 5. This is in contrast to the sympathetic treatment Homer gives Helen in Book 3. In fact, Athena explicitly encourages Diomedes to hunt Aphrodite in the battle. Later Athena upbraids Diomedes for not solving another problem that has emerged – that of Ares. But Diomedes rightly points out he has been forbidden to fight any god except Aphrodite, and Athena has provided him with the means to hunt her: the ability to distinguish between mortals and gods on the field of battle. It is clear that Athena is using Diomedes as her instrument of revenge. Athena’s antipathy is reflected in Diomedes words to Aphrodite after he wounds her:

- “Daughter of Zeus, give up the war, your lust for carnage!”

- So, it’s not enough that you lure defenceless women

- to their ruin? Haunting the fighting are you?

Aphrodite appears on the field of battle to protect her wounded son, Aeneas, and by the account of the action she would seem to be courageous:

- Round her beloved son her glistening arms went streaming,

- flinging her shining robe before him, only a fold

Even so, Aphrodite is the subject of abuse and mockery in this book. Homer’s narrative reflects Diomedes’s contempt just before he stabs Aphrodite, calling her a “coward goddess”. And when Aphrodite seeks comfort from her mother, Dione, Athena and Hera overhear the conversation and mock her to Zeus:

- . . . Our goddess of love -

- I’d swear she’s just been rousing another Argive,

- those men the goddess loves to such despair.

- Stroking one of the Argive women’s rippling gowns

Their reference to “another Argive” implies a woman in addition to Helen, who is implicitly said to “pant and lust for Trojans”. Yet this salacious representation is not the reality of Helen as we have seen from Book 3. Helen is a dignified and sad woman. And the representation of Aphrodite in this book plays to misogynistic clichés against women and desire. Yet while we are invited to side against Aphrodite and Ares through their representations, it is the actions of Athena and Hera that seem more worthy of the schoolyard in this book: petty and vengeful. This reading is against the reading invited by the narrative, which is mostly from the point of view of Athena and Diomedes. But it is Athena’s actions – her use of Diomedes as a weapon – which heightens the conflict and brings Ares into battle on the Trojan side

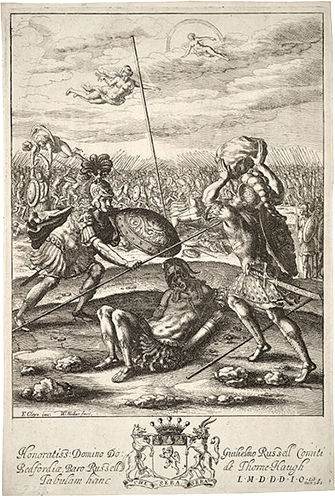

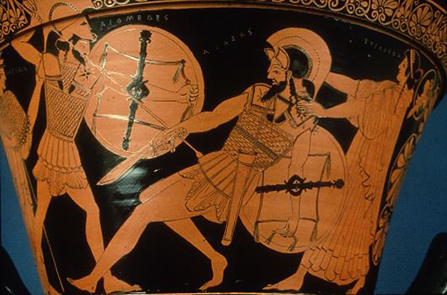

Representations in Art

- Aeneas sprang down with his shield and heavy spear,

- fearing the Argives might just drag away the corpse,

- somehow, somewhere. Aeneas straddled the body -

- proud in his fighting power like some lion -

- shielded the corpse with spear and round buckler,

- burning to kill off any man who met him face-to-face

- and he loosed a bloodcurdling cry. Just as Diomedes

- hefted a boulder in his hands, a tremendous feat -

- no two men could hoist it, weak as men are now,

- but all on his own he raised it high with ease,

- flung it and struck Aeneas' thigh where the hipbone

- turns inside the pelvis, the joint they call the cup -

- it smashed the socket, snapped both tendons too

- and the jagged rock tore back the skin in shreds.

- Athena levered Sthenelus out the back of the car.

- A twist of her wrist and the man hit the ground,

- springing aside as the goddess climbed on board

- blazing to fight beside the shining Diomedes.

- The big oaken axle groaned beneath the weight,

- bearing a great man and a terrifying goddess -

- and Pallas Athena seized the reins and whip,

- lashing the racing horses straight at Ares.

- study guides

- lesson plans

- homework help

The Iliad - Book 5 Summary & Analysis

Book 5 Summary

(read more from the Book 5 Summary)

FOLLOW BOOKRAGS:

116 pages • 3 hours read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more. For select classroom titles, we also provide Teaching Guides with discussion and quiz questions to prompt student engagement.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Books 13-16

Books 17-20

Books 21-24

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Books 5-8 Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Book 5 summary: “diomedes fights the gods”.

Athena lures Ares away from the battlefield under the guise of avoiding Zeus’s wrath. The Achaeans take the upper hand. The poet catalogues both Achaean victors and Trojan victims, including personal details about each life lost. Scamandrius, for example, learned to hunt and kill wild animals from Artemis herself; Phereclus’s grandfather was a blacksmith beloved by Athena.

Athena fills Diomedes with “strength and daring” so he can “win himself great glory” (164). He rages through the ranks like a rushing stream, “sweeping away the dikes” (167). Pandarus boasts after wounding Diomedes, who prays to Athena to avenge him. She answers, removing the mist from his eyes so that he can recognize gods who enter the battle. She warns him not to fight any immortal but Aphrodite.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,350+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,950+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By these authors

The Odyssey

Homer, Transl. Emily Wilson

Featured Collections

Ancient Greece

View Collection

Books & Literature

Mortality & Death

Novels & Books in Verse

Everything you need for every book you read.

The Iliad recounts a brief but crucial period of the Trojan War, a conflict between the city of Troy and its allies against a confederation of Greek cities, collectively known as the Achaeans. The conflict began when Paris , the son of Troy’s king Priam , seized a willing Helen , the most beautiful woman in the world, from the Achaean king Menelaus . The Achaeans raised a massive army and sailed to Troy, bent on winning Helen back by force.

As the story begins, the war is in its ninth year. The Achaeans have recently sacked a nearby city, taking several beautiful women captive along with a lot of treasure. Chryses , a priest of Apollo from the sacked city, approaches the Achaean camp and asks Agamemnon , the leader of the Achaeans, to release his daughter, who is one of the captives, from slavery. Agamemnon refuses. Chryses prays to Apollo to punish the Achaeans, and Apollo rains down a plague on the Achaean army.

The plague ravages the Achaean army. Desperate for an answer, the Achaeans ask the prophet Calchas about the plague’s cause. Calchas instructs Agamemnon to give back Chryses’ daughter. Agamemnon agrees reluctantly, but demands that he be given Briseis , the captive girl given to the warrior Achilles, as compensation. Achilles is enraged by Agamemnon’s demand and refuses to fight for Agamemnon any longer.

Achilles, the greatest of the Achaean fighters, desires revenge on Agamemnon. He calls to his mother Thetis, an immortal sea-nymph, and asks her to beseech Zeus to turn the tide of the war against the Achaeans. Since Achilles is fated to die a glorious death in battle, an Achaean collapse will help give Achilles glory, allowing him to come to their aid. Zeus assents to Thetis’ request.

On the battlefield, Paris and Menelaus agree to duel to end the war. Menelaus is victorious, but the Trojans break the agreement sworn to beforehand. The armies plunge into a battle that lasts several days. In the fighting, many soldiers distinguish themselves, including the Achaean Diomedes and Priam’s son Hector . The tide of battle turns several times, but the Trojan forces under Hector eventually push the Achaeans back to the fortifications they have built around their ships.

Meanwhile, a surrogate conflict is being waged between the gods on behalf of the Trojans and Achaeans. Athena , Hera , and Poseidon support the Achaean forces, while Apollo , Aphrodite , and Ares support the Trojans. As the battle rages on, the gods give strength and inspiration to their respective champions. Eventually Zeus, planning to shape the conflict by himself so that he may fulfill his promise to Thetis, bans intervention in the war by the other gods. Zeus helps engineer the Trojan advance against the Achaeans.

Under immense pressure, the elderly Achaean captain Nestor proposes that an embassy be sent to Achilles in order to convince him to return to battle. Achilles listens to their pleas but ultimately refuses, stating that he will not stir until the Trojans to attack his own ships. After a prolonged struggle, the Trojans finally break through the Achaean fortress, threatening to burn the ships and slaughter the Achaeans.

Achilles’ inseparable comrade Patroclus , fearing the destruction of the Achaean forces, asks Achilles if he can take his place in battle. Achilles eventually agrees, and as the first Achaean ship begins to burn, Patroclus leads out Achilles’ army, dressed in Achilles’ armor in order to frighten the Trojans. Patroclus fights excellently, and the Trojans are repulsed from the ships. However, Patroclus disobeys Achilles’ order to return after driving back the Trojans. He pursues the Trojans all the way to the gates of Troy. Zeus, planning this sequence of events all along, allows Apollo to knock Patroclus over. Hector then kills Patroclus as he lies on the ground, and a battle breaks out over Patroclus’ body. Hector strips Achilles’ armor from Patroclus, but Menelaus and others manage to save the body.

When Achilles learns of Patroclus’ death, he is stricken with grief. Desiring revenge on Hector and the Trojans, Achilles reconciles with Agamemnon. His mother Thetis visits the smith god Hephaestus , who forges new, superhuman armor for Achilles, along with a magnificent shield that depicts the entire world. Meanwhile, the Trojans camp outside their city’s walls, underestimating Achilles’ fury. The next day, Achilles dons his armor and launches into battle, slaughtering numerous Trojans on the plains of Troy. Achilles also fights the river god Xanthus , who becomes upset with Achilles for killing so many Trojans in his waters.

The Trojans flee from the rage of Achilles and hide inside the walls of Troy. Hector alone remains outside the wall, determined to stand fast against Achilles, but as Achilles approaches him, Hector loses his nerve and begins to run. Achilles chases Hector around the walls of Troy four times, but eventually Hector turns and faces Achilles. With the help of Athena, Achilles kills Hector. He attaches Hector’s corpse to his chariot and drags the body back to the Achaean camp as revenge for Patroclus’ death.

Achilles, still grieving, holds an elaborate funeral for Patroclus, which is followed by a series of commemorative athletic games. After the games, Achilles continues to drag Hector’s body around Patroclus’ corpse for nine days. The gods, wishing to see Hector buried properly, send Priam, escorted by Hermes , to ransom Hector’s body. Priam pleads with Achilles for mercy, asking Achilles to remember his own aging father. Achilles is moved by Priam’s entreaty and agrees to give back Hector’s body. Priam returns to Troy with Hector, and the Trojans grieve for their loss. A truce is declared while the Trojans bury Hector.

About this Edition

The acts of diomed.

Diomed, assisted by Pallas, performs wonders in this day’s battle. Pandarus wounds him with an arrow, but the goddess cures him, enables him to discern gods from mortals, and prohibits him from contending with any of the former, excepting Venus. AEneas joins Pandarus to oppose him; Pandarus is killed, and AEneas in great danger but for the assistance of Venus; who, as she is removing her son from the fight, is wounded on the hand by Diomed. Apollo seconds her in his rescue, and at length carries off AEneas to Troy, where he is healed in the temple of Pergamus. Mars rallies the Trojans, and assists Hector to make a stand. In the meantime AEneas is restored to the field, and they overthrow several of the Greeks; among the rest Tlepolemus is slain by Sarpedon. Juno and Minerva descend to resist Mars; the latter incites Diomed to go against that god; he wounds him, and sends him groaning to heaven.

The first battle continues through this book. The scene is the same as in the former.

But Pallas now Tydides’ soul inspires, [143] Fills with her force, and warms with all her fires, Above the Greeks his deathless fame to raise, And crown her hero with distinguish’d praise. High on his helm celestial lightnings play, His beamy shield emits a living ray; The unwearied blaze incessant streams supplies, Like the red star that fires the autumnal skies, When fresh he rears his radiant orb to sight, And, bathed in ocean, shoots a keener light. Such glories Pallas on the chief bestow’d, Such, from his arms, the fierce effulgence flow’d: Onward she drives him, furious to engage, Where the fight burns, and where the thickest rage.

The sons of Dares first the combat sought, A wealthy priest, but rich without a fault; In Vulcan’s fane the father’s days were led, The sons to toils of glorious battle bred; These singled from their troops the fight maintain, These, from their steeds, Tydides on the plain. Fierce for renown the brother-chiefs draw near, And first bold Phegeus cast his sounding spear, Which o’er the warrior’s shoulder took its course, And spent in empty air its erring force. Not so, Tydides, flew thy lance in vain, But pierced his breast, and stretch’d him on the plain. Seized with unusual fear, Idaeus fled, Left the rich chariot, and his brother dead. And had not Vulcan lent celestial aid, He too had sunk to death’s eternal shade; But in a smoky cloud the god of fire Preserved the son, in pity to the sire. The steeds and chariot, to the navy led, Increased the spoils of gallant Diomed.

Struck with amaze and shame, the Trojan crew, Or slain, or fled, the sons of Dares view; When by the blood-stain’d hand Minerva press’d The god of battles, and this speech address’d:

“Stern power of war! by whom the mighty fall, Who bathe in blood, and shake the lofty wall! Let the brave chiefs their glorious toils divide; And whose the conquest, mighty Jove decide: While we from interdicted fields retire, Nor tempt the wrath of heaven’s avenging sire.”

Her words allay the impetuous warrior’s heat, The god of arms and martial maid retreat; Removed from fight, on Xanthus’ flowery bounds They sat, and listen’d to the dying sounds.

Meantime, the Greeks the Trojan race pursue, And some bold chieftain every leader slew: First Odius falls, and bites the bloody sand, His death ennobled by Atrides’ hand:

As he to flight his wheeling car address’d, The speedy javelin drove from back to breast. In dust the mighty Halizonian lay, His arms resound, the spirit wings its way.

Thy fate was next, O Phaestus! doom’d to feel The great Idomeneus’ protended steel; Whom Borus sent (his son and only joy) From fruitful Tarne to the fields of Troy. The Cretan javelin reach’d him from afar, And pierced his shoulder as he mounts his car; Back from the car he tumbles to the ground, And everlasting shades his eyes surround.

Then died Scamandrius, expert in the chase, In woods and wilds to wound the savage race; Diana taught him all her sylvan arts, To bend the bow, and aim unerring darts: But vainly here Diana’s arts he tries, The fatal lance arrests him as he flies; From Menelaus’ arm the weapon sent, Through his broad back and heaving bosom went: Down sinks the warrior with a thundering sound, His brazen armour rings against the ground.

Next artful Phereclus untimely fell; Bold Merion sent him to the realms of hell. Thy father’s skill, O Phereclus! was thine, The graceful fabric and the fair design; For loved by Pallas, Pallas did impart To him the shipwright’s and the builder’s art. Beneath his hand the fleet of Paris rose, The fatal cause of all his country’s woes; But he, the mystic will of heaven unknown, Nor saw his country’s peril, nor his own. The hapless artist, while confused he fled, The spear of Merion mingled with the dead. Through his right hip, with forceful fury cast, Between the bladder and the bone it pass’d; Prone on his knees he falls with fruitless cries, And death in lasting slumber seals his eyes.

From Meges’ force the swift Pedaeus fled, Antenor’s offspring from a foreign bed, Whose generous spouse, Theanor, heavenly fair, Nursed the young stranger with a mother’s care. How vain those cares! when Meges in the rear Full in his nape infix’d the fatal spear; Swift through his crackling jaws the weapon glides, And the cold tongue and grinning teeth divides.

Then died Hypsenor, generous and divine, Sprung from the brave Dolopion’s mighty line, Who near adored Scamander made abode, Priest of the stream, and honoured as a god. On him, amidst the flying numbers found, Eurypylus inflicts a deadly wound; On his broad shoulders fell the forceful brand, Thence glancing downwards, lopp’d his holy hand, Which stain’d with sacred blood the blushing sand. Down sunk the priest: the purple hand of death Closed his dim eye, and fate suppress’d his breath.

Thus toil’d the chiefs, in different parts engaged. In every quarter fierce Tydides raged; Amid the Greek, amid the Trojan train, Rapt through the ranks he thunders o’er the plain; Now here, now there, he darts from place to place, Pours on the rear, or lightens in their face. Thus from high hills the torrents swift and strong Deluge whole fields, and sweep the trees along, Through ruin’d moles the rushing wave resounds, O’erwhelm’s the bridge, and bursts the lofty bounds; The yellow harvests of the ripen’d year, And flatted vineyards, one sad waste appear! [144] While Jove descends in sluicy sheets of rain, And all the labours of mankind are vain.

So raged Tydides, boundless in his ire, Drove armies back, and made all Troy retire. With grief the leader of the Lycian band Saw the wide waste of his destructive hand: His bended bow against the chief he drew; Swift to the mark the thirsty arrow flew, Whose forky point the hollow breastplate tore, Deep in his shoulder pierced, and drank the gore: The rushing stream his brazen armour dyed, While the proud archer thus exulting cried:

“Hither, ye Trojans, hither drive your steeds! Lo! by our hand the bravest Grecian bleeds, Not long the deathful dart he can sustain; Or Phoebus urged me to these fields in vain.” So spoke he, boastful: but the winged dart Stopp’d short of life, and mock’d the shooter’s art. The wounded chief, behind his car retired, The helping hand of Sthenelus required; Swift from his seat he leap’d upon the ground, And tugg’d the weapon from the gushing wound; When thus the king his guardian power address’d, The purple current wandering o’er his vest:

“O progeny of Jove! unconquer’d maid! If e’er my godlike sire deserved thy aid, If e’er I felt thee in the fighting field; Now, goddess, now, thy sacred succour yield. O give my lance to reach the Trojan knight, Whose arrow wounds the chief thou guard’st in fight; And lay the boaster grovelling on the shore, That vaunts these eyes shall view the light no more.”

Thus pray’d Tydides, and Minerva heard, His nerves confirm’d, his languid spirits cheer’d; He feels each limb with wonted vigour light; His beating bosom claim’d the promised fight. “Be bold, (she cried), in every combat shine, War be thy province, thy protection mine; Rush to the fight, and every foe control; Wake each paternal virtue in thy soul: Strength swells thy boiling breast, infused by me, And all thy godlike father breathes in thee; Yet more, from mortal mists I purge thy eyes, [145] And set to view the warring deities. These see thou shun, through all the embattled plain; Nor rashly strive where human force is vain. If Venus mingle in the martial band, Her shalt thou wound: so Pallas gives command.”

With that, the blue-eyed virgin wing’d her flight; The hero rush’d impetuous to the fight; With tenfold ardour now invades the plain, Wild with delay, and more enraged by pain. As on the fleecy flocks when hunger calls, Amidst the field a brindled lion falls; If chance some shepherd with a distant dart The savage wound, he rouses at the smart, He foams, he roars; the shepherd dares not stay, But trembling leaves the scattering flocks a prey; Heaps fall on heaps; he bathes with blood the ground, Then leaps victorious o’er the lofty mound. Not with less fury stern Tydides flew; And two brave leaders at an instant slew; Astynous breathless fell, and by his side, His people’s pastor, good Hypenor, died; Astynous’ breast the deadly lance receives, Hypenor’s shoulder his broad falchion cleaves. Those slain he left, and sprung with noble rage Abas and Polyidus to engage; Sons of Eurydamus, who, wise and old, Could fate foresee, and mystic dreams unfold; The youths return’d not from the doubtful plain, And the sad father tried his arts in vain; No mystic dream could make their fates appear, Though now determined by Tydides’ spear.

Young Xanthus next, and Thoon felt his rage; The joy and hope of Phaenops’ feeble age: Vast was his wealth, and these the only heirs Of all his labours and a life of cares. Cold death o’ertakes them in their blooming years, And leaves the father unavailing tears: To strangers now descends his heapy store, The race forgotten, and the name no more.

Two sons of Priam in one chariot ride, Glittering in arms, and combat side by side. As when the lordly lion seeks his food Where grazing heifers range the lonely wood, He leaps amidst them with a furious bound, Bends their strong necks, and tears them to the ground: So from their seats the brother chiefs are torn, Their steeds and chariot to the navy borne.

With deep concern divine AEneas view’d The foe prevailing, and his friends pursued; Through the thick storm of singing spears he flies, Exploring Pandarus with careful eyes. At length he found Lycaon’s mighty son; To whom the chief of Venus’ race begun:

“Where, Pandarus, are all thy honours now, Thy winged arrows and unerring bow, Thy matchless skill, thy yet unrivall’d fame, And boasted glory of the Lycian name? O pierce that mortal! if we mortal call That wondrous force by which whole armies fall; Or god incensed, who quits the distant skies To punish Troy for slighted sacrifice; (Which, oh avert from our unhappy state! For what so dreadful as celestial hate)? Whoe’er he be, propitiate Jove with prayer; If man, destroy; if god, entreat to spare.”

To him the Lycian: “Whom your eyes behold, If right I judge, is Diomed the bold: Such coursers whirl him o’er the dusty field, So towers his helmet, and so flames his shield. If ’tis a god, he wears that chief’s disguise: Or if that chief, some guardian of the skies, Involved in clouds, protects him in the fray, And turns unseen the frustrate dart away. I wing’d an arrow, which not idly fell, The stroke had fix’d him to the gates of hell; And, but some god, some angry god withstands, His fate was due to these unerring hands. Skill’d in the bow, on foot I sought the war, Nor join’d swift horses to the rapid car. Ten polish’d chariots I possess’d at home, And still they grace Lycaon’s princely dome: There veil’d in spacious coverlets they stand; And twice ten coursers wait their lord’s command. The good old warrior bade me trust to these, When first for Troy I sail’d the sacred seas; In fields, aloft, the whirling car to guide, And through the ranks of death triumphant ride. But vain with youth, and yet to thrift inclined, I heard his counsels with unheedful mind, And thought the steeds (your large supplies unknown) Might fail of forage in the straiten’d town; So took my bow and pointed darts in hand And left the chariots in my native land.

“Too late, O friend! my rashness I deplore; These shafts, once fatal, carry death no more. Tydeus’ and Atreus’ sons their points have found, And undissembled gore pursued the wound. In vain they bleed: this unavailing bow Serves, not to slaughter, but provoke the foe. In evil hour these bended horns I strung, And seized the quiver where it idly hung. Cursed be the fate that sent me to the field Without a warrior’s arms, the spear and shield! If e’er with life I quit the Trojan plain, If e’er I see my spouse and sire again, This bow, unfaithful to my glorious aims, Broke by my hand, shall feed the blazing flames.”