An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Case Rep Womens Health

- v.33; 2022 Jan

A case report of successful vaginal delivery in a patient with severe uterine prolapse and a review of the healing process of a cervical incision

Associated data.

The incidence of severe uterine prolapse during childbirth is approximately 0.01%. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, no reports detail the healing process of the cervix during uterine involution. This report describes successful vaginal delivery and the healing process of postpartum uterine prolapse and cervical tears in a patient with severe uterine prolapse.

Case presentation

A patient in her 40s (gravida 3, para 1, abortus 1) with severe uterine prolapse successfully delivered a live female baby weighing 3190 g at 38 + 5 weeks of gestation by assisted vaginal delivery. Uterine prolapse had improved to approximately 2° by 2 months postoperatively. On postpartum day 4, during the healing process of cervical laceration, the thread loosened in a single layer of continuous sutures due to uterine involution, and poor wound healing was observed. The wound was subsequently re-sutured with a two-layer single ligation suture (Gambee suture + vertical mattress suture). However, on postpartum day 11, a large thread ball was hindering the healing of the muscle layer, which improved with re-suturing.

Although vaginal delivery in a patient with severe uterine prolapse is possible in some cases, the cervix should be sutured, while considering cervical involution after delivery.

- • Pregnancies with complete uterine prolapse are exceedingly rare.

- • When suturing the uterus, involution after delivery should be considered.

- • This is the first report on the healing process of cervical canal lacerations.

1. Introduction

Pregnancies complicated by uterine prolapse are rare, and cases of severe uterine prolapse are rarer [ 1 ]. Recommendations regarding the management of this infrequent but potentially fatal condition are scarce [ 1 ]. Pregnancies with severe uterine and cervical prolapse have been reported; however, the delivery method is complicated in most cases, and few reports of successful vaginal delivery despite severe cervical edema have been reported in the literature [ 2 ]. This report describes a case of vaginal delivery in a patient with severe uterine prolapse and presents the first description of the healing process after a Duhrssen incision performed on a prolapsed cervix.

2. Case Presentation

A 43-year-old woman, gravida 3, para 1, abortus 1, implanted with frozen-thawed embryos was diagnosed with high-risk pregnancy at her previous hospital. Her obstetric history included a term, vaginal singleton delivery (3298 g, male neonate) 4 years earlier, which was complicated by a retained placenta. The placenta was removed manually. Thereafter, no uterine prolapse was observed.

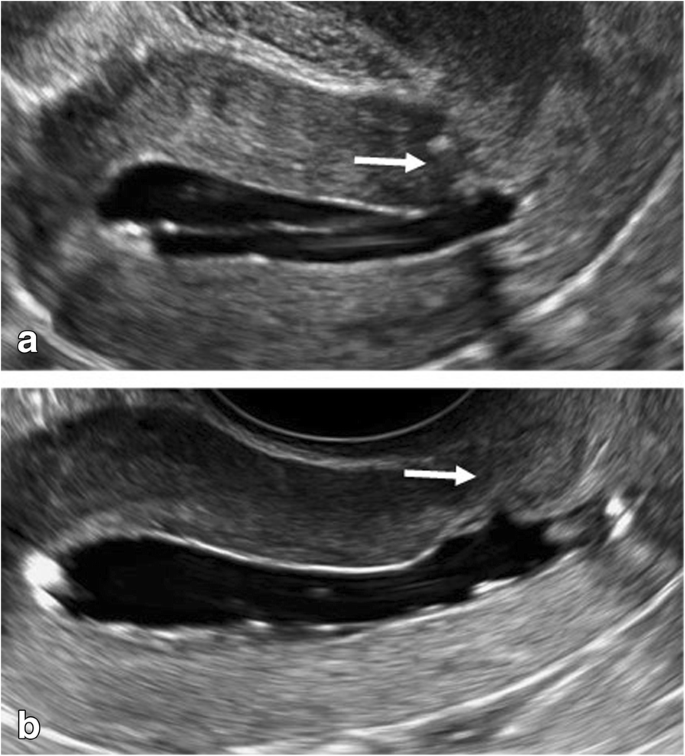

She had been undergoing treatment for hypertension and dermatomyositis since 2018. She had been prescribed nifedipine CR 20 mg/day for the hypertension and steroids (prednisolone) 4.0 mg/day and tacrolimus 3.4 mg/day for the dermatomyositis. As the symptoms of dermatomyositis improved in 2019, the pregnancy was approved. She had also undergone sub-plasmalemmal myomectomy 10 years previously. She was otherwise fit and had a normal body mass index; she did not smoke and had no allergies. During the index pregnancy, at the 19-week check-up, her cervix was found to have descended. Subsequent regular ultrasound scans at 24, 26, 30, 32, and 34 weeks of gestation demonstrated normal fetal morphology, with normal and concordant fetal growth. An ultrasound scan at 36 weeks showed that the cervical canal was very long (8.8 cm) and closed ( Fig. 1 ). A 95-mm self-removable donut-shaped pessary (donut support for 3° prolapse/procidentia; CooperSurgical Milex™, 75 Corporate Drive Trumbull, CT 06611 USA) appeared to drop out spontaneously. Color Doppler imaging with 3D transvaginal ultrasonography revealed cervical edema ( Fig. 2 ). Color Doppler examination did not reveal any obvious blood flow. She was admitted to hospital at 37 + 2 weeks due to a worsening skin rash over the perineum and difficulty in washing. Her blood pressure was stable, her general condition was good, and there were no abnormal clinical or biochemical findings suggestive of an infection.

Photographs at the onset of uterine prolapse at 36 weeks of gestation.

Cervical edema and cervical length of 8.8 cm, color Doppler with 3D transvaginal ultrasonography.

A, Sagittal section; B, Coronal section; C, Transverse section; D, Color Doppler.

In the pre-induction state of the cervix, the Bishop scoring system showed that the cervical os was dilated by 4 cm, effaced 0%, station −3, soft, and anterior 7 points. Induction with oxytocin was commenced at 38 weeks and 4 days of gestation for planned delivery, but there were no effective contractions. The next day, the cervix was dilated by 6 cm and effaced 30%.

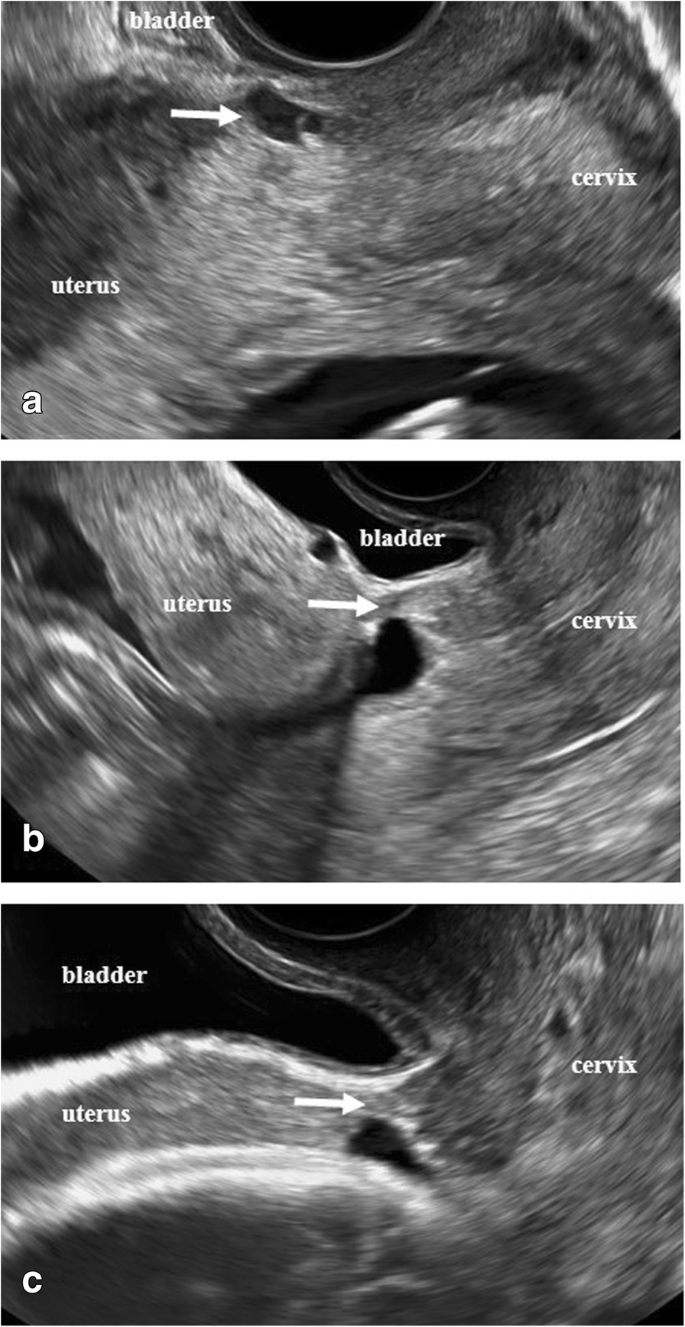

With the patient's consent, we performed an artificial rupture of the membranes, which led to labor progression. After an intramuscular injection of butyl scopolamine, her cervix was softened for a short time. The cervix was completely prolapsed outside the vagina, but the station had reached +1 in relation to the pubic symphysis. The 95-mm donut-type pessary was easily removed from the soft birth canal, and vacuum extraction delivery (Kiwi®) was deemed feasible. Cervix-holding forceps were used, and a Duhrssen incision was made under visualization as labor progressed. A cervical Duhrssen incision of approximately 5 cm was made, and the length of the incision was extended to 10 cm. We did not perform a perineal incision. After three traction cycles, a live female neonate weighing 3190 g was delivered, with Apgar scores of 8/9 (1st and 5th minutes) and a pH of 7.319. The delivery was complicated with a retained placenta and massive postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), with blood loss of 2500 mL. The cervix was sutured, as usual, using 0 Vicryl® sutures in one continuous layer from 5 mm above the upper edge of incision, and the surface of the suture appeared to be fine. However, on discharge examination on the 4th day post-delivery, a complete breakdown of the repair of approximately 5 cm of the cervical canal was identified at the introitus. After she was returned to the operating theatre, debridement was performed; the first layer was sutured with a single ligation using the Gambee suture (2–0 Vicryl®), and the second layer was sutured with an end-to-end single ligation using the mattress suture technique (2–0 Vicryl®). On the 7th day after re-suturing (11th day after delivery), the uterus was markedly involuted, and uterine prolapse somewhat improved, but the ligature threads were collected in one place and became a single ball of threads. All sutures were removed, and the wound was re-sutured with two Z-sutures using a 3–0 Vicryl® thread. Sutures were removed 1 month postpartum, and complete wound healing was confirmed. Two months post-surgery, uterine prolapse had improved to a 2° prolapse. The healing process of cervical laceration and cervical canal prolapse is shown in Fig. 3 .

Healing process of cervical laceration and cervical canal prolapse.

A: Cervical laceration suture surface on the day of delivery.

B: On postpartum day 4, suture failure was noted due to a continuous 1-layer suture (0 mesh thread (Vicryl®), absorbable thread).

C: On postpartum day 4, stitches were removed and debridement was performed.

D: On postpartum day 4, re-suture and first-layer Gambee suture (2–0 mesh thread, absorbable (Vicryl®)) were performed.

E: On postpartum day 4, re-suture and second-layer horizontal mattress suture (2–0 mesh thread, absorbable (Vicryl®)) were performed.

F: On postpartum day 11, the thread had formed into a ball, which interfered with viability. The wound was re-sutured using a single ligation due to suture failure (3–0 mesh thread, absorbable (Vicryl®)).

G: On postpartum day 28, uterine prolapse improved to 2°–3°, and the wound became viable.

3. Discussion

Uterine and cervical prolapse are rare in pregnancy. Uterine prolapse during pregnancy is a precarious event, with an incidence of 1 in 10,000–15,000 pregnancies [ 3 ]. It can be associated with minor cervical desiccation and ulceration or devastating maternal fatalities. Complications include urinary retention, preterm labor, premature delivery, fetal demise, maternal sepsis, and urinary retention [ 1 ].

Prolapse development in pregnancy is likely due to an escalation of the physiological changes in pregnancy, leading to a weakening of pelvic organ support [ 4 ]. Increased cortisol and progesterone levels during pregnancy may contribute to uterine relaxation. In our case, the patient did not have any congenital risk factors. However, she had developed dermatomyositis after her last delivery and had been prescribed prednisolone 4 mg/day which she had taken consistently since before pregnancy. In a previously reported case study, pessary insertion resulted in the temporary improvement of uterine prolapse [ 5 , 6 ], but, in our case, a 95-mm donut pessary (CooperSurgical Milex™) easily slipped out of the soft birth canal. According to a case review of pregnancies with uterine prolapse reported by Kana et al. [ 7 ], since 1997, vaginal delivery could be performed in only 2 of 16 patients with cervical edema, and none of them was diagnosed with complete uterine prolapse. Jeong et al. [ 8 ] reported that, since 2002, only 1 of 14 patients with uterine prolapse was able to be delivered vaginally. These results suggest that this study reports a valuable case of vaginal delivery. In fact, the two cases reported recently were both delivered by cesarean section [ 9 , 10 ].

We performed vaginal delivery, and a Duhrssen incision was stitched with minimal blood loss. In active labor, a prolapsed cervix that is enlarged and edematous can be managed with a topical concentrated magnesium solution to treat cervical dystocia and lacerations [ 11 ]. Verma et al. reported that two incisions approximately 3 cm long each were made at 2 o'clock and 10 o'clock positions on the cervix using tissue-cutting scissors [ 12 ]. In contrast, our approach involves using one incision that is approximately 5 cm long at the 6 o'clock position on the cervix using tissue-cutting scissors. Cervical laceration suturing was performed, and we observed that a single layer of continuous sutures had lost tension and was loose due to the significant involution of the cervix. Moreover, the external os was found outside the vagina; thus, the wound could not be covered, and thread traction could not prevent incision separation at 6 o'clock. After debridement, Gambee sutures and horizontal mattress sutures were used to re-suture the wound, but on postpartum examination on day 11, the ligature thread from the single ligation suture had formed a ball of threads. We re-sutured the wound using 3–0 Vicryl® sutures, and the wound was stabilized. The cervix was edematous and markedly dilated; therefore, any sutures are likely to be extruded as the cervix involutes and the edema improves. A technique that results in the end-to-end apposition of the incision is more likely to succeed as it allows for clot formation and healing by primary intention with less reliance on suture tension. Nevertheless, the majority of such cases have been managed by cesarean section. This vaginal delivery resulted in a prolonged process of labor induction, cervical incision (which likely induced long-term cervical incompetence), three trips to the operating room, a retained placenta, and a massive PPH; however, direct causality of the last two factors is unknown. Avoiding cesarean section in this case resulted in an unavoidable burden on the patient after delivery. Although we do not necessarily recommend vaginal delivery, we report it as an option. An extensive literature search listing the keywords “healing process, cervical canal lacerations, single ligation suture, and continuous sutures” revealed that this is the first report on the healing process of cervical canal lacerations.

4. Conclusion

Vaginal delivery of a pregnancy complicated by severe uterine prolapse is possible in some cases. Given the paucity of data on the management and pregnancy outcomes of patients with uterine anomalies, such cases should be considered high risk, and individualized care should be given to patients to optimize outcomes. Moreover, when suturing the uterus cervix, uterus cervical involution after delivery should be considered. This case report adds to the literature as it highlights the management of a rare obstetric condition.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Video of assisted vaginal delivery and salvage from cervical dystocia in uterocervical prolapse: Duhrssen incision

Supplementary material

Contributors

Jota Maki was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, was the main author, conducted the literature review, and drafted the manuscript, and was involved in the patient’s treatment, from outpatient care to hospitalization and discharge.

Tomohiro Mitoma was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, was involved in the case, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Sakurako Mishima was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, and reviewed the draft.

Akiko Ohira was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, and reviewed the draft.

Kazumasa Tani was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, and reviewed the draft.

Eriko Eto was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, was involved in the case, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Kei Hayata was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, and reviewed the draft.

Hisashi Masuyama was responsible for the conceptualization of the case report, was involved in the case, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

All authors approved the final version of the paper and take full responsibility for the work.

This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Patient consent

The patient provided informed consent for the publication of this report and all accompanying images.

Provenance and peer review

This case report was not commissioned and was peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

We thank the obstetrics surgeons and other healthcare personnel involved in the treatment of patients at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Okayama University Hospital.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this case report.

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 21 June 2018

Normal vaginal delivery at term after expectant management of heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy: a case report

- Olga Vikhareva 1 , 2 ,

- Ekaterina Nedopekina 1 , 2 &

- Andreas Herbst 1 , 2

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 12 , Article number: 179 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

8 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Heterotopic pregnancy with a combination of a caesarean scar pregnancy and an intrauterine pregnancy is rare and has potentially life-threatening complications.

Case presentation

We describe the case of a 27-year-old white woman who had experienced an emergency caesarean delivery at 39 weeks for fetal distress with no postpartum complications. This is a report of the successful expectant management of a heterotopic scar pregnancy. The gestational sac implanted into the scar area was non-viable. The woman was treated expectantly and had a normal vaginal delivery at 37 weeks of gestation.

Expectant management under close monitoring can be appropriate in small non-viable heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancies.

Peer Review reports

Heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy (CSP), in which one gestational sac is located in the caesarean scar area and the other one is a normal intrauterine pregnancy, is rare and may have potentially life-threatening complications. The correct management of this condition is unclear. It is a challenge to manage a heterotopic CSP with preservation of the intrauterine pregnancy minimizing the risks for mother and child.

Transvaginal sonography is a valuable diagnostic tool in the management of such pregnancies [ 1 ]. Currently, we offer women with one previous caesarean section participation in an ongoing study of transvaginal ultrasound examinations in each trimester. The study provides support to identify patients with high risk of uterine rupture/potential placental complications to make an individual plan for pregnancy surveillance and delivery.

We have not found previous reports on successful expectant management of spontaneous heterotopic CSP with the preservation of intrauterine pregnancy resulting in a normal vaginal delivery.

We describe the case of a 27-year-old white woman who had experienced an emergency caesarean delivery at 39 weeks for fetal distress with no postpartum complications. As part of our ongoing study “Vaginal delivery after caesarean section”, she underwent saline contrast sonohysterography 6 months after the caesarean section. The caesarean scar had a small indentation and the remaining myometrium over the defect was 7.5 mm (Fig. 1a ).

Saline contrast sonohysterography images. The arrows indicate the caesarean section scar 6 months after the index caesarean ( a ) and 6 months after the end of the heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy by vaginal delivery ( b ). The thickness of the remaining myometrium appeared almost unchanged

In the current pregnancy, she had a dating scan at around 11 weeks with no remarks. She came for a transvaginal ultrasound examination at around 13 weeks as part of our study. This scan revealed a duplex pregnancy with one viable intrauterine fetus with normal anatomy and placenta located high on the anterior wall and a small gestational sac (8 mm) with a yolk sac without embryo was located in the caesarean scar (Fig. 2a ). There was no extensive vascularity surrounding the sac. One corpus luteum was found in each of the two ovaries. She was asymptomatic.

Transvaginal sonographic images. The arrows indicate the appearance of the cesarean scar area at the presence of the scar pregnancy at 13 + 2 ( a ) and after reabsorption of the scar pregnancy at 22 + 0 ( b ) and at 30 + 2 ( c ) weeks of gestation

She was informed that not enough evidence existed to advise a specific management of this condition. After discussion with her and her husband, expectant management was chosen with a new ultrasound examination after 5 weeks.

She came to our ultrasound department at 18 weeks, 22 weeks, and 30 weeks of gestation. She remained asymptomatic. The ectopic gestational sac was not visualized with transvaginal or transabdominal scans at the 18 weeks examination (Fig. 2b ). The niche in the scar and the thickness of the thinnest part of the remaining myometrium appeared unchanged at all visits. The intrauterine pregnancy developed normally with no signs of abnormal placentation. At 30 weeks of gestation the ultrasound appearance of the scar area did not indicate any contraindications for vaginal delivery. The thickness of the lower uterine segment (LUS) was 4.9 mm (Fig. 2c ). In agreement with our patient, vaginal delivery was planned. The staff of the labor ward was fully informed.

She was admitted to the labor ward with irregular contractions in week 37 + 0. Her cervix dilated to 3 cm with no further progress. Due to that oxytocin augmentation was administered for 3 hours. The duration of active labor was 6.5 hours. A healthy male neonate weighing 2985 g was delivered, with Apgar scores 9–10 at 1 and 5 minutes and umbilical cord pH 7.27. The placenta delivered spontaneously and total blood loss was 250 ml. The postpartum period was without any complications, and she was discharged home the next day.

At a follow-up visit 6 months postpartum, saline contrast sonohysterography showed no signs of the previous CSP, and the remaining myometrium over the hysterotomy scar defect was 5.7 mm (Fig. 1b ).

Ethical approval for the ongoing study was obtained by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Lund University, Sweden, reference number 2013/176. Our patient has given permission for publication of this case report in a scientific journal.

Discussion and conclusions

Management of heterotopic CSP with an intrauterine gestation is a challenge. Treatment options for CSP include expectant management, and medical or surgical termination [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ].

The use of methotrexate has been reported in management of ectopic gestations, but in heterotopic pregnancies with preservation of intrauterine pregnancy this may cause a teratogenic effect with fetal anomalies [ 5 , 6 ].

A few case reports have described treatment of heterotopic CSP viable pregnancies with local injection of potassium chloride. This method is commonly used for fetal reduction in multiple pregnancy [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Treatment with potassium chloride is associated with an increased risk of abdominal pain, pregnancy loss, excessive vaginal bleeding, prematurity, need for subsequent surgery, and spontaneous rupture of membranes and subsequent chorioamnionitis [ 1 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ].

Laparoscopic treatment can be an option for removal of an ectopic scar pregnancy, but there is increased risk of hemorrhage and miscarriage [ 7 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

Michaels et al. suggested that expectant management can be appropriate in early gestations with no heartbeat, often resulting in complete absorption of the trophoblast [ 10 ]. Our patient had no bleeding or abdominal pain. The gestational sac located in the scar was non-viable with no extensive vascularity.

It is difficult to study possible changes in the tissues of the caesarean scar area after reabsorption of CSP. With ultrasound one can appreciate the thickness of LUS during the pregnancy, but not the quality of the myometrium.

Interestingly, it was found that our patient had a small defect in the uterine scar detected at ultrasound 6 months after caesarean section. Jurkovic et al. reported 18 cases of CSP over a 4-year period [ 1 ]. They observed that the majority of scars were well-healed. These data suggest that the size of a defect in the scar does not increase the risk of CSP; however, more studies are needed.

Our patient had a “normal” dating scan at 11 weeks. The early diagnosis of a heterotopic CSP is easy to miss, in particular with presence of an intrauterine viable embryo. Serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is of little value as long as an intrauterine pregnancy is ongoing. Transvaginal ultrasound is the best tool for diagnosis and management of such pregnancies. In our ongoing study “Vaginal delivery after caesarean section” we assess multiple parameters: scar area/scar pregnancy/potential placental complications. These ultrasound characteristics and clinical evaluation together with close monitoring provide support for the obstetrician in management of these women.

The literature is sparse and we still lack evidence and strong clinical guidelines to manage heterotopic pregnancies. Each woman diagnosed with scar implantation should receive an individual approach.

Abbreviations

Caesarean scar pregnancy

Human chorionic gonadotropin

Lower uterine segment

Jurkovic D, Hillaby K, Woelfer B, Lawrence A, Salim R, Elson CJ. First trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into the lower uterine segment Cesarean section scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21(3):220–7.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Osborn DA, Williams TR, Craig BM. Cesarean scar pregnancy: sonographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings, complications, and treatment. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:1449–56.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Uysal F, Usal A, Adam G. Cesarean scar pregnancy: diagnosis, management, and follow-up. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:1295–300.

Litwicka K, Greco E. Caesarean scar pregnancy: a review of management options. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23:415–21.

Jordan RL, Wilson JG, Schumacher HJ. Embryotoxicity of the folate antagonist methotrexate in rats and rabbits. Teratology. 1977;15(1):73–9.

Timor-Tritsch IE. Is it safe to use methotrexate for selective injection in heterotopic pregnancy? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:193–4.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A. Unforeseen consequences of the increasing rate of cesarean deliveries: early placenta accreta and cesarean scar pregnancy. A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(1):14–29.

Mohammed ABF, Farid I, Ahmed B, Ghany EA. Obstetric and neonatal outcome of multifetal pregnancy reduction. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2015;20(3):176–81.

Article Google Scholar

AlShelaly UE, Al-Mousa NH, Kurdi WI. Obstetric outcomes in reduced and non-reduced twin pregnancies. Saudi Med J. 2015;36(9):1122–5.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Michaels AY, Washburn EE, Pocius KD, Benson CB, Doubilet PM, Carusi DA. Outcome of cesarean scar pregnancies diagnosed sonographically in the first trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34(4):595–9.

Salomon LJ, Fernandez H, Chauveaud A, Doumerc S, Frydman R. Successful management of a heterotopic Caesarean scar pregnancy: potassium chloride injection with preservation of the intrauterine gestation: case report. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(1):189–91.

Monteagudo A, Minior VK, Stephenson C, Monda S, Timor-Tritsch IE. Non-surgical management of live ectopic pregnancy with ultrasound-guided local injection: a case series. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25(3):282–8.

Wang CJ, Chao AS, Yuen LT, Wang CW, Soong YK, Lee CL. Endoscopic management of cesarean scar pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):494.e1-4.

Ash A, Smith A, Maxwell D. Caesarean scar pregnancy. BJOG. 2007;114(3):253–63.

Demirel LC, Bodur H, Selam B, Lembet A, Ergin T. Laparoscopic management of heterotopic cesarean scar pregnancy with preservation of intrauterine gestation and delivery at term: case report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1293.e5-7.

Download references

Availability of data and materials

Data are available in internal digitalized record systems of Skåne University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Skåne University Hospital Malmö, Lund University, Box 117, 221 00, Lund, Sweden

Olga Vikhareva, Ekaterina Nedopekina & Andreas Herbst

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Skåne University Hospital, Lund University, Jan Waldenströms gata 47, SE-20502, Malmö, Sweden

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors EN, AH, and OV contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. The first draft was written by EN and OV and all the authors revised it critically and approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Olga Vikhareva .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval was obtained by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Lund University, Sweden, reference number 2013/176.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Vikhareva, O., Nedopekina, E. & Herbst, A. Normal vaginal delivery at term after expectant management of heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy: a case report. J Med Case Reports 12 , 179 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-018-1713-0

Download citation

Received : 13 February 2018

Accepted : 08 May 2018

Published : 21 June 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-018-1713-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Heterotopic caesarean scar pregnancy

- Expectant management

- Vaginal delivery

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

LEE T. DRESANG, MD, AND NICOLE YONKE, MD, MPH

Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(3):202-208

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Most of the nearly 4 million births in the United States annually are normal spontaneous vaginal deliveries. In the first stage of labor, normal birth outcomes can be improved by encouraging the patient to walk and stay in upright positions, waiting until at least 6 cm dilation to diagnose active stage arrest, providing continuous labor support, using intermittent auscultation in low-risk deliveries, and following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for group B streptococcus prophylaxis. Most women with a low transverse uterine incision are candidates for a trial of labor after cesarean delivery and should be counseled accordingly. Pain management during labor includes complementary modalities and systemic opioids, epidural anesthesia, and pudendal block. Outcomes in the second stage of labor can be improved by using warm perineal compresses, allowing women more time to push before intervening, and offering labor support. Delayed pushing increases the length of the second stage of labor and does not affect the rate of spontaneous vaginal delivery. A tight nuchal cord can be clamped twice and cut before delivery of the shoulders, or the baby may be delivered using a somersault maneuver in which the cord is left nuchal and the distance from the cord to placenta minimized by pushing the head toward the maternal thigh. After delivery, skin-to-skin contact with the mother is recommended. Beyond 35 weeks' gestation, there is no benefit to bulb suctioning the nose and mouth. Postpartum maternal and neonatal outcomes can be improved through delayed cord clamping, active management to prevent postpartum hemorrhage, careful examination for external anal sphincter injuries, and use of absorbable synthetic suture for second-degree perineal laceration repair. Practices that will not improve outcomes and may result in negative outcomes include discontinuation of epidurals late in labor and routine episiotomy.

Out of the nearly 4 million births in the United States in 2013, approximately 3 million were vaginal deliveries. 1 Accurate pregnancy dating is essential for anticipating complications and preparing for delivery. A woman's estimated due date is 40 weeks from the first day of her last menstrual period. If ultrasonography is performed, the due date calculated by the first ultrasound will either confirm or change the due date based on the last menstrual period ( Table 1 ) . 2 If reproductive technology was used to achieve pregnancy, dating should be based on the timing of embryo transfer. 2

When describing how a pregnancy is dated, “by last menstrual period” means ultrasonography has not been performed, “by X-week ultrasonography” means that the due date is based on ultrasound findings only, and “by last menstrual period consistent with X-week ultrasound findings” means ultrasonography confirmed the estimated due date calculated using the last menstrual period.

Table 2 defines the classifications of terms of pregnancies. 3 Maternity care clinicians can learn more from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO) course ( https://www.aafp.org/also ). Emergency medical technicians, medical students, and others with limited maternity care experience may benefit from the AAFP Basic Life Support in Obstetrics course ( https://www.aafp.org/blso ), which offers a module on normal labor and delivery. The Global ALSO manual ( https://www.aafp.org/globalalso ) provides additional training for normal delivery in low-resource settings.

Onset of Labor

Labor begins when regular uterine contractions cause progressive cervical effacement and dilation. The risk of infection increases after rupture of membranes, which may occur before or during labor. Induction is recommended for a term pregnancy if the membranes rupture before labor begins. 4 Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated if the patient is positive for group B streptococcus at the 35- to 37-week screening or within five weeks of screening if performed earlier in pregnancy, or if the patient has group B streptococcus bacteriuria in the current pregnancy or had a previous infant with group B streptococcus sepsis. 5 If the group B streptococcus status is unknown at the time of labor, the patient should receive prophylaxis if she is less than 37 weeks' gestation, the membranes have been ruptured for 18 hours or more, she has a low-grade fever of at least 100.4°F (38°C), or an intrapartum nucleic acid amplification test result is positive. 5

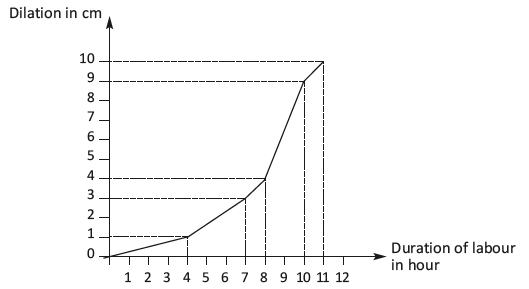

The First Stage of Labor

The first stage of labor begins with regular uterine contractions and ends with complete cervical dilation (10 cm). Reanalysis of data from the National Collaborative Perinatal Project (including 39,491 deliveries between 1959 and 1966) and new data from the Consortium on Safe Labor (including 98,359 deliveries between 2002 and 2008) have led to reevaluation of the normal labor curve. Latent labor lasting many hours is normal and is not an indication for cesarean delivery. 6 – 8 Active labor with more rapid dilation may not occur until 6 cm is achieved. Cesarean delivery for failure to progress in active labor is indicated only if the woman is 6 cm or more dilated with ruptured membranes, and she has no cervical change for at least four hours of adequate contractions (more than 200 Montevideo units per intrauterine pressure catheter) or inadequate contractions for at least six hours. 8 If possible, the membranes should be ruptured before diagnosing failure to progress. Labor can be significantly longer in obese women. 9 Walking, an upright position, and continuous labor support in the first stage of labor increase the likelihood of spontaneous vaginal delivery and decrease the use of regional anesthesia. 10 , 11

Most women who have had a prior cesarean delivery with a low transverse uterine incision are candidates for labor after cesarean delivery (LAC) and should be counseled accordingly. 12 A recent AAFP guideline concludes that planned labor and vaginal delivery are an appropriate option for most women with a previous cesarean delivery. 13 Women who may want more children should be encouraged to try LAC because the risk of pregnancy complications increases with increasing number of cesarean deliveries. 12 The risk of uterine rupture with cesarean delivery is less than 1%, and the risk of the infant dying or having permanent brain injury is approximately one in 2,000 (the same as for vaginal delivery in primiparous women). 14 Based on the clinical scenario, women with two prior cesarean deliveries may also try LAC. 12 Contraindications to vaginal delivery are outlined in Table 3 .

In low-risk deliveries, intermittent auscultation by handheld Doppler ultrasonography has advantages over continuous electronic fetal monitoring. Although continuous electronic fetal monitoring is associated with a decrease in the rare outcome of neonatal seizures, it is associated with an increase in cesarean and assisted vaginal deliveries with no other improvement in neonatal outcomes. 15 When electronic fetal monitoring is employed, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development definitions and categories should be used ( Table 4 ) . 16

Pain management includes nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic methods. 17 Nonpharmacologic approaches include acupuncture and acupressure 18 ; other complementary and alternative therapies, including audioanalgesia, aromatherapy, hypnosis, massage, and relaxation techniques 19 ; sterile water injections 17 ; continuous labor support 11 ; and immersion in water. 20 Pharmacologic analgesia includes systemic opioids, nitrous oxide, epidural anesthesia, and pudendal block. 17 , 21 Although epidurals provide better pain relief than systemic opioids, they are associated with a significantly longer second stage of labor; an increased rate of oxytocin (Pitocin) augmentation; assisted vaginal delivery; and an increased risk of maternal hypotension, urinary retention, and fever. 22 Cesarean delivery for abnormal fetal heart tracings is more common in women with epidurals, but there is no significant difference in overall cesarean delivery rates compared with women who do not have epidurals. 22 Discontinuing an epidural late in labor does not increase the likelihood of vaginal delivery and increases inadequate pain relief. 23

The Second Stage of Labor

The second stage begins with complete cervical dilation and ends with delivery. The fetal head comes below the pubic symphysis and then extends. Pushing can begin once the cervix is fully dilated. Although delayed pushing or “laboring down” shortens the duration of pushing, it increases the length of the second stage and does not affect the rate of spontaneous vaginal delivery. 24 Arrest of the second stage of labor is defined as no descent or rotation after two hours of pushing for a multiparous woman without an epidural, three hours of pushing for a multiparous woman with an epidural or a nulliparous woman without an epidural, and four hours of pushing for a nulliparous woman with an epidural. 8 A prolonged second stage in nulliparous women is associated with chorioamnionitis and neonatal sepsis in the newborn. 25

If the fetus is in the occipitotransverse or occipitoposterior position in the second stage, manual rotation to the occipitoanterior position decreases the likelihood of operative vaginal and cesarean delivery. 26 Fetal position can be determined by identifying the sagittal suture with four suture lines by the anterior (larger) fontanelle and three by the posterior fontanelle. The position of the ears can also be helpful in determining fetal position when a large amount of caput is present and the sutures are difficult to palpate. Bedside ultrasonography is helpful when position is unclear by examination findings.

Women may push in any position that they prefer. Potential positions include on the back, side, or hands and knees; standing; or squatting. Women without epidurals who deliver in upright positions (kneeling, squatting, or standing) have a significantly reduced risk of assisted vaginal delivery and abnormal fetal heart rate pattern, but an increased risk of second-degree perineal laceration and an estimated blood loss of more than 500 mL. 27 Flexing the hips and legs increases the pelvic inlet diameter, allowing more room for delivery.

Second stage warm perineal compresses have been associated with a reduction in third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations. 28 Studies have not shown benefit to keeping hands on vs. hands off the fetal head and maternal perineum during delivery. 29 Although not well studied, shorter pushes as the head is crowning are encouraged by many clinicians in an attempt to decrease perineal lacerations. Also, delivering between contractions may decrease perineal lacerations. 30 Routine episiotomy should not be performed. Episiotomy is associated with more severe perineal trauma, increased need for suturing, and more healing complications. 31

Once the infant's head is delivered, the clinician can check for a nuchal cord. The cord may be wrapped around the neck one or more times. If the nuchal cord is loose, it can be gently pulled over the head if possible or left in place if it does not interfere with delivery. A tight nuchal cord can be clamped twice and cut before delivery of the shoulders, although this may be associated with increased neonatal complications, including hypovolemia, anemia, shock, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, cerebral palsy, and death according to case reports. The tight nuchal cord itself may contribute to some of these outcomes, however. 32 Another option for a tight nuchal cord is the somersault maneuver (carefully delivering the anterior and posterior shoulder, and then delivering the body by somersault while the head is kept next to the maternal thigh). After delivery, the cord can be removed from the neck. 32 A video of the somersault maneuver is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WaJ6sZ4nfnQ . More research on the safety and effectiveness of this maneuver is needed.

After delivery of the head, gentle downward traction should be applied with one gloved hand on each side of the fetal head to facilitate delivery of the shoulders. After the anterior shoulder delivers, the clinician pulls up gently, and the rest of the body should deliver easily. The vigorous newborn should be placed directly in contact with the mother's skin and covered with a blanket. Skin-to-skin contact is associated with decreased time to the first feeding, improved breastfeeding initiation and continuation, higher blood glucose level, decreased crying, and decreased hypothermia. 33 After delivery, quick drying of the newborn helps prevent hypothermia and stimulates crying and breathing. Beyond 35 weeks' gestation, there is no benefit to bulb suctioning the nose and mouth; earlier gestational ages have not been studied. 34

Delayed cord clamping, defined as waiting to clamp the umbilical cord for one to three minutes after birth or until cord pulsation has ceased, is associated with benefits in term infants, including higher birth weight, higher hemoglobin concentration, improved iron stores at six months, and improved respiratory transition. 35 Benefits are even greater with preterm infants. 36 However, delayed cord clamping is associated with an increase in jaundice requiring phototherapy. 35 Delayed cord clamping is indicated with all deliveries unless urgent resuscitation is needed. It is not necessary to keep the newborn below the level of the placenta before cutting the cord. 37 The cord should be clamped twice, leaving 2 to 4 cm of cord between the newborn and the closest clamp, and then the cord is cut between the clamps.

The Third Stage of Labor

The third stage begins after delivery of the newborn and ends with the delivery of the placenta. The average length of the third stage of labor is eight to nine minutes. 38

The greatest risk in the third stage is postpartum hemorrhage, which was recently redefined as 1,000 mL or more of blood loss or signs and symptoms of hypovolemia. 39 The median blood loss with vaginal delivery is 574 mL. 40 Blood loss is often underestimated by as much as 30%, and underestimation increases with increasing blood loss. 41 The risk of hemorrhage increases after 18 minutes and is six times greater after 30 minutes. 38 Postpartum hemorrhage is most commonly caused by atony (70% of cases). 42 Other causes include vaginal or cervical lacerations, uterine inversion, retained products of conception, and coagulopathy. 42 Table 5 lists risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage. 42

Active management of the third stage of labor (AMTSL), which is recommended by the World Health Organization, 43 is associated with a reduction in the risk of hemorrhage, both greater than 500 mL and greater than 1,000 mL, maternal hemoglobin level of less than 9 g per dL (90 g per L) after delivery, need for maternal blood transfusion, and need for more uterotonics in labor or in the first 24 hours after delivery. 44 However, AMTSL is also associated with an increase in postpartum maternal diastolic blood pressure, emesis, and use of analgesia and a decrease in neonatal birth weight. 44 Although AMTSL has traditionally consisted of oxytocin (10 IU intramuscularly or 20 IU per L intravenously at 250 mL per hour) and early cord clamping, the most important component now appears to be the administration of oxytocin. 43 , 44 Early cord clamping is no longer a component because it does not decrease postpartum hemorrhage and may be associated with neonatal harm. 35 , 44 Delayed cord clamping may avoid interfering with early transplacental transfusion and avoid the increase in maternal blood pressure and decrease in fetal weight associated with traditional AMTSL. 44 More research is needed regarding the effects of individual components of AMTSL. 44

Cervical, vaginal, and perineal lacerations should be repaired if there is bleeding. Second-degree laceration repairs are best performed in a continuous manner with absorbable synthetic suture. Compared with interrupted sutures, continuous repair of second-degree perineal lacerations is associated with less analgesia use, less short-term pain, and less need for suture removal. 45 Compared with catgut (chromic) sutures, synthetic sutures (polyglactin 910 [Vicryl], polyglycolic acid [Dexon]) are associated with less pain, less analgesia use, and less need for resuturing. However, synthetic sutures are associated with increased need for unabsorbed suture removal. 46

There are no quality randomized controlled trials assessing repair vs. nonrepair of second-degree perineal lacerations. 47 External anal sphincter injuries are often unrecognized, which can lead to fecal incontinence. 48 Knowledge of perineal anatomy and careful visual and digital examination can increase external anal sphincter injury detection. 48

Data Sources : A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using key terms including labor and obstetric, delivery and obstetric, labor stage and first, labor stage and second, labor stage and third, doulas, anesthesia and epidural, and postpartum hemorrhage. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. We also searched the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, the National Guideline Clearinghouse database, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Search dates: September 4, 2014, and April 23, 2015.

This article is one in a series on “Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO),” initially established by Mark Deutchman, MD, Denver, Colo. The coordinator of this series is Larry Leeman, MD, MPH, ALSO Managing Editor, Albuquerque, N.M.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(1):1-65.

Committee opinion no 611: method for estimating due date. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):863-866.

Spong CY. Defining “term” pregnancy: recommendations from the Defining “Term” Pregnancy Workgroup. JAMA. 2013;309(23):2445-2446.

Practice bulletins no. 139: premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(4):918-930.

Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease—revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-10):1-36.

Laughon SK, Branch DW, Beaver J, Zhang J. Changes in labor patterns over 50 years. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):419.e1-9.

Zhang J, Landy HJ, Branch DW, et al.; Consortium on Safe Labor. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1281-1287.

Spong CY, Berghella V, Wenstrom KD, Mercer BM, Saade GR. Preventing the first cesarean delivery: summary of a joint Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1181-1193.

Kominiarek MA, Zhang J, Vanveldhuisen P, Troendle J, Beaver J, Hibbard JU. Contemporary labor patterns: the impact of maternal body mass index. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(3):244.e1-8.

Lawrence A, Lewis L, Hofmeyr GJ, Styles C. Maternal positions and mobility during first stage labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD003934.

Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD003766.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 115: vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 1):450-463.

American Academy of Family Physicians. Clinical practice guideline: planning for labor and vaginal birth after cesarean. January 2015. https://www.aafp.org/pvbac . Accessed April 23, 2015.

Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, et al.; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(25):2581-2589.

Alfirevic Z, Devane D, Gyte GM. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD006066.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 106: intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring: nomenclature, interpretation, and general management principles. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(1):192-202.

Schrock SD, Harraway-Smith C. Labor analgesia. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85(5):447-454.

Smith CA, Collins CT, Crowther CA, Levett KM. Acupuncture or acupressure for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7:CD009232.

Smith CA, Collins CT, Cyna AM, Crowther CA. Complementary and alternative therapies for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD003521.

Cluett ER, Burns E. Immersion in water in labour and birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD000111.

Ullman R, Smith LA, Burns E, Mori R, Dowswell T. Parenteral opioids for maternal pain relief in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;9:CD007396.

Anim-Somuah M, Smyth RM, Jones L. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD000331.

Torvaldsen S, Roberts CL, Bell JC, Raynes-Greenow CH. Discontinuation of epidural analgesia late in labour for reducing the adverse delivery outcomes associated with epidural analgesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;4:CD004457.

Tuuli MG, Frey HA, Odibo AO, et al. Immediate compared with delayed pushing in the second stage of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(3):660-668.

Laughon SK, Berghella V, Reddy UM, Sundaram R, Lu Z, Hoffman MK. Neonatal and maternal outcomes with prolonged second stage of labor [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol . 2014;124(4):842]. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):57-67.

Le Ray C, Deneux-Tharaux C, Khireddine I, Dreyfus M, Vardon D, Goffinet F. Manual rotation to decrease operative delivery in posterior or transverse positions. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(3):634-640.

Gupta JK, Hofmeyr GJ, Shehmar M. Position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD002006.

Aasheim V, Nilsen AB, Lukasse M, Reinar LM. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD006672.

Albers LL, Sedler KD, Bedrick EJ, Teaf D, Peralta P. Midwifery care measures in the second stage of labor and reduction of genital tract trauma at birth: a randomized trial. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50(5):365-372.

Bowe NL. Intact perineum: a slow delivery of the head does not adversely affect the outcome of the newborn. J Nurse Midwifery. 1981;26(2):5-11.

Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:CD000081.

Mercer JS, Skovgaard RL, Peareara-Eaves J, et al. Nuchal cord management and nurse-midwifery practice. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50(5):373-379.

Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N, Dowswell T. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD003519.

Kelleher J, Bhat R, Salas AA, et al. Oronasopharyngeal suction versus wiping of the mouth and nose at birth. Lancet. 2013;382(9889):326-330.

McDonald SJ, Middleton P, Dowswell T, Morris PS. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping of term infants on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD004074.

Committee on Obstetric Practice, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 543: timing of umbilical cord clamping after birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1522-1526.

Vain NE, Satragno DS, Gorenstein AN, et al. Effect of gravity on volume of placental transfusion. Lancet. 2014;384(9939):235-240.

Magann EF, Evans S, Chauhan SP, Lanneau G, Fisk AD, Morrison JC. The length of the third stage of labor and the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):290-293.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstetric data definitions. 2014. http://www.acog.org/-/media/Departments/Patient-Safety-and-Quality-Improvement/2014reVITALizeObstetricDataDefinitionsV10.pdf . Accessed April 23, 2015.

Stafford I, Dildy GA, Clark SL, Belfort MA. Visually estimated and calculated blood loss in vaginal and cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(5):519.e1-7.

Al Kadri HM, Al Anazi BK, Tamim HM. Visual estimation versus gravimetric measurement of postpartum blood loss: a prospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283(6):1207-1213.

Anderson JM, Etches D. Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(6):875-882.

Tunçalp O, Souza JP, Gülmezoglu M World Health Organization. New WHO recommendations on prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;123(3):254-256.

Begley CM, Gyte GM, Devane D, McGuire W, Weeks A. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD007412.

Kettle C, Dowswell T, Ismail KM. Continuous and interrupted suturing techniques for repair of episiotomy or second-degree tears. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD000947.

Kettle C, Dowswell T, Ismail KM. Absorbable suture materials for primary repair of episiotomy and second degree tears. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;6:CD000006.

Elharmeel SM, Chaudhary Y, Tan S, et al. Surgical repair of spontaneous perineal tears that occur during childbirth versus no intervention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;8:CD008534.

Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones PW. Occult anal sphincter injuries—myth or reality?. BJOG. 2006;113(2):195-200.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2015 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 131. Normal Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

- Introduction

- Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- Indications

- Contraindications

- Initial Assessment

- Patient Preparation

- Alternative Techniques

- Complications

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

The Emergency Physician will, on occasion, be required to handle the delivery of an infant when an Obstetrician or Family Physician is not available. The management of normal labor and delivery requires a basic understanding of the mechanisms of labor, the assessment and treatment of the mother, the safe delivery of the infant, and careful observation of both in the immediate postpartum period.

Labor is defined as repetitive uterine contractions leading to cervical change (dilation and effacement). The mechanisms of labor, also known as the cardinal movements of labor, describe the changes in the position of the fetal head as it travels through the birth canal. The safe delivery of the infant is the ultimate goal of labor.

Pelvic Anatomy

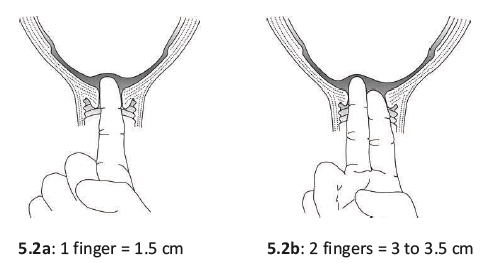

A successful vaginal delivery is dependent on the adequacy of the female pelvis. Through the use of clinical pelvimetry, physicians are able to make an assessment if adequate space exists for the passage of the fetus during prenatal visits. In theory, the most useful planes to measure are the pelvic inlet and the midplane. Evaluating the pelvic inlet is done by measuring the diagonal conjugate ( Figures 131-1 A & B ). When assessing the midplane, a measurement is taken of the ischial interspinous or bi-ischial diameter ( Figure 131-1 C ). Inadequate measurements indicate potential problems that may result in fetal entrapment, shoulder dystocia, or prolonged labor. 1

Figure 131-1.

Measure pelvic distances to determine if there may be difficulties during the delivery. A. The pelvic conjugate diameters. B. Measuring the diagonal conjugate. C. The ischial interspinous distance.

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Best of the Blogs

Pop-up div successfully displayed.

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

Labour and Delivery Care Module: 5. Conducting a Normal Delivery

Study session 5 conducting a normal delivery, introduction.

In the previous study sessions of this Module, you were introduced to the definition, signs, symptoms and stages of labour and the use of the partograph. You also learned about care of the woman in labour. In this session, you will learn how to assist the woman in the second stage of a normal labour and how to deliver the baby. The second stage is the part of labour when the mother pushes the baby out of the uterus and down the vagina, and the baby is born. Second stage begins when the cervix is completely dilated and ends when the baby is delivered.

During the second stage, the mother’s passive control during the long hours of the first stage of labour is replaced by intense physical effort and exertion for a comparatively short period. The mother and her support person require stamina, courage and confidence from the birth attendant. A healthy outcome for the mother and her baby depends upon your competence in providing quality care and the successful partnership between you and the mother.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 5

When you have studied this session you should be able to:

5.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold . (SAQs 5.1, 5.2 and 5.3)

5.2 Describe the signs of second stage labour and explain what is happening to the mother and the baby as it moves down the birth canal. (SAQs 5.1 and 5.2)

5.3 Describe how you would assess if the second stage is progressing normally and identify the warning signs that sufficient progress is not being made. (SAQs 5.1 and 5.2)

5.4 Describe how you would conduct the normal delivery of a healthy baby and give it immediate newborn care. (SAQs 5.3 and 5.4)

5.5 Explain how you would support bonding between mother and newborn after the delivery. (SAQ 5.5)

5.1 Recognising the signs of second stage labour

The only positive sign in diagnosing second stage of labour is full dilatation of the cervix. The only way you can be certain the cervix is dilated all the way is to do a vaginal examination. But remember: repeated vaginal exams can cause infection. It is better not to do a vaginal exam frequently (less than 4 hours interval) unless:

- When you count the fetal heart beat it is outside the normal range (outside 120–160 beats per minute).

- There is a sudden gush of amniotic fluid, which may indicate that there is a risk for cord prolapse or placental abruption.

- You detect signs of second stage of labour beginning before the next scheduled vaginal examination. (See Box 5.1 for signs of second stage.)

With experience, you can usually tell when the mother is ready to push without doing a vaginal exam.

Box 5.1 Signs of second stage

If the mother has two or more of these signs, she is probably in second stage of labour:

- She feels an uncontrollable urge to push (she may say she needs to pass stool)

- She may hold her breath or grunt during contractions

- She starts to sweat

- Her mood changes — she may become sleepy or more focused

- Her external genitals or anus begin to bulge out during contractions

- She feels the baby’s head begin to move into the vagina

- A purple line appears between the mother’s buttocks as they spread apart from the pressure of the baby’s head.

5.1.1 What happens during second stage of labour?

During second stage, when the baby is high in the vagina, you can see the mother’s genitals bulge during contractions. Her anus may open a little. Between contractions, her genitals relax (Figure 5.1).

Each contraction (and each push from the mother) moves the baby further down. Between contractions, the mother’s uterus relaxes and pulls the baby back up a little (but not as far as it was before the contraction).

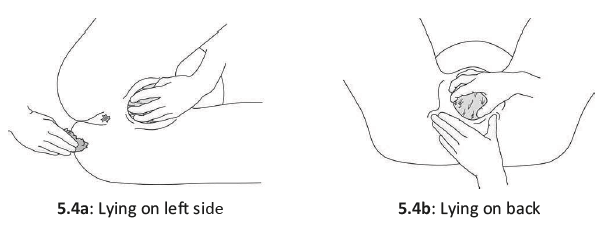

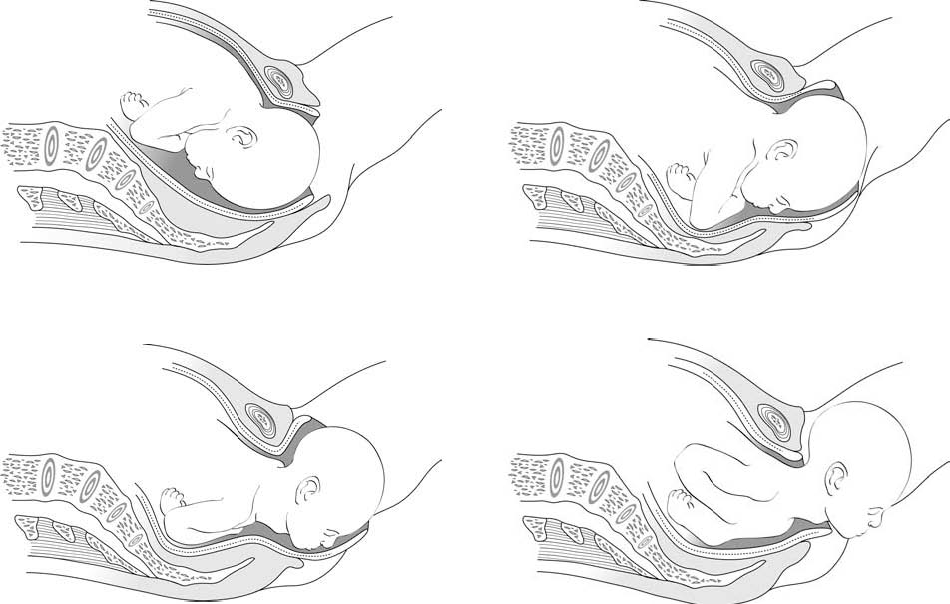

After a while, you can see a little of the baby’s head coming down the vagina during contractions. The baby moves like an ocean tide: in and out, in and out, but each time closer to birth (Figures 5.2a–d).

When the baby’s head stretches the vaginal opening to about the size of the palm of your hand (Figure 5.3), the head will stay at the opening - even between contractions. This is called crowning . Once the head is born, the rest of the body usually slips out easily with one or two pushes.

5.1.2 How does the baby move through the birth canal?

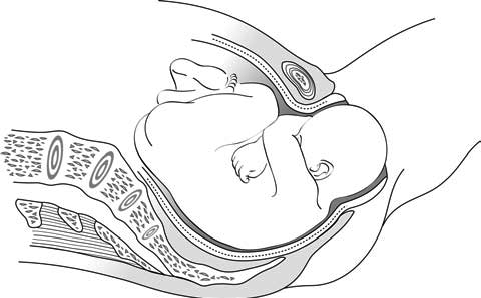

Figure 5.4 shows the movement of the baby through the birth canal. Babies move this way if they are positioned head-first, with their backs toward their mother’s bellies. But many babies do not face this way. A baby who faces the mother’s front, or who is breech, moves in a different way. Watch each birth closely to see how babies in different positions move.

5.2 Help the mother and baby have a safe birth

Continue to check the mother’s vital signs as you have been doing during the first stage of labour.

5.2.1 Check the baby’s heart beat

The baby’s heartbeat is harder to hear in second stage because the heart is usually lower in the mother’s belly. If you are experienced, you may be able to hear the baby’s heart between contractions. You can hear it best very low in the mother’s belly, near the pubic bone (Figure 5.5). It is OK for the heartbeat to be as slow as 100 beats a minute during a pushing contraction. But it should come right back up to the normal rate as soon as the contraction is over.

What is the normal fetal heatbeat?

Between 120 and 160 beats per minute.

If the baby’s heartbeat does not come back up within 1 minute, or stays slower than 100 beats a minute for more than a few minutes, the baby may be in trouble. Ask the mother to change position (to lie on her side), and check the baby’s heartbeat again. If it is still slow, ask the mother to stop pushing for a few contractions. Make sure she takes deep, long breaths so that the baby will get adequate oxygen.

5.2.2 Support the mother’s pushing

When the cervix is fully dilated, the mother’s body will push the baby out. Some healthcare providers get very excited during the pushing stage. They yell at mothers, ‘Push! Push!’ but mothers do not usually need much help to push. Their bodies push naturally, and when they are encouraged and supported, women will usually find the way to push that feels right and gets the baby out.

If a mother has difficulty pushing, do not scold or threaten her. And never insult or hit a woman to make her push. Upsetting or frightening her can slow the birth. Instead, explain how to push well (Figure 5.6). Each contraction is a new chance. Praise her for trying.

Tell the mother when you see her outer genitals bulge. Explain that this means the baby is coming down. When you see the head, let the mother touch it. This may also help her to push better.

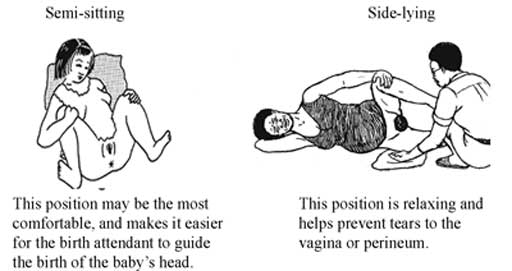

Let the mother choose the position that feels good to her. You already learned about different positions in first stage in Study Session 3. But note that it is not good for the mother to lie flat on her back during a normal birth. Lying flat can squeeze the blood vessels that bring blood to the baby and the mother, and can make the birth slower.

5.2.3 Watch for warning signs

Watch the speed of each birth. If the birth is taking too long, take the woman to a hospital. This is one of the most important things you can do to prevent serious problems or even death of women in labour.

First babies may take a full 2 hours of strong contractions and good pushing to be born. Second and later babies usually take less than 1 hour of pushing. Watch how fast the baby’s head is moving down through the birth canal. As long as the baby continues to move down (even very slowly), and the baby’s heartbeat is normal, and the mother has strength, then the birth is normal and healthy. The mother should continue to push until the head crowns.

But pushing for a long time with no progress can cause serious problems, including fistula, uterine rupture (you will learn about this in Study Session 10 of this Module), or even death of the baby or mother. If you do not see the mother’s genitals bulging after 30 minutes of strong pushing, or if the mild bulging does not increase, the head may not be coming down. If the baby is not moving down at all after 1 hour of pushing, the mother needs help.

Therefore, refer immediately if the woman stayed (couldn’t deliver) in the second stage for more than:

- 1 hour with no good progress (multigravida woman)

- 2 hours with no good progress (primigravida).

5.3 Conducting delivery of the baby

Your skill and judgment are crucial factors in minimising trauma for the mother and ensuring a safe delivery for the baby. These qualities are acquired through experience but certain basic principles must be applied whatever the expertise you have. These are:

- Observation of progress of the labour

- Prevention of infection

- Emotional and physical comfort of the mother

- Anticipation of normal events

- Recognition of abnormal labour or fetal distress.

5.3.1 Prevent tears in the vaginal opening

The birth of the baby’s head may tear the mother’s vaginal opening. But you can prevent tears by supporting the vagina during the birth. In some communities, circumcision of girls (also called female genital cutting) is common. This harmful traditional practice causes scars that may not stretch enough to let the baby out or the scar may tear as the baby is born.

5.3.2 Delivery of the head

Wash your hands well and put on sterile gloves and other protective materials.

Clean the perineal area using antispetic and (if you have them) put clean drapes (cloths) over the mother’s thighs.

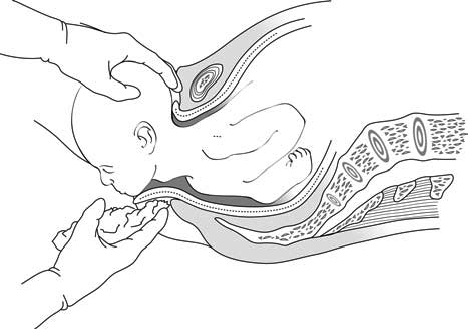

Press one hand firmly on the perineum (the skin between the opening of the vagina and the anus). This hand will keep the baby’s chin close to its chest — making it easier for the head to come out (Figure 5.8). Use a piece of cloth or gauze to cover the mother’s anus; some faeces (stool) may be pushed out with the baby’s head.

Use your other hand to apply gentle downward pressure on the top of the baby’s head to keep the baby’s head flexed (bent downwards).

Once the head has crowned, the head is born by the extension of the face, which appears at the perineum.

Clear the baby’s nose and mouth. When the head is born, and before the rest of the body comes out, you may need to help the baby breathe by clearing its mouth and nose. If the baby has some mucus or water in its nose or mouth, wipe it gently with a clean cloth wrapped around your finger.

5.3.3 Check if the cord is around the baby’s neck

If there is a rest between the birth of the head and the birth of the shoulders, feel for the cord around the baby’s neck.

- If the cord is wrapped loosely around the neck, loosen it so it can slip over the baby’s head or shoulders.

- If the cord is very tight, or if it is wrapped around the neck more than once, try to loosen it and slip it over the head.

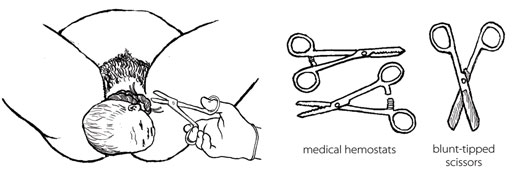

- If you cannot loosen the cord, and if the cord is preventing the baby from coming out, you may have to clamp and cut it.

If you can, use medical hemostats (clamps) and blunt-tipped scissors for clamping and cutting the cord in this situation. If you do not have them, use clean string and a new razor. Clamp or tie in two places and cut in between (Figure 5.9). Be very careful not to cut the mother or the baby’s neck.

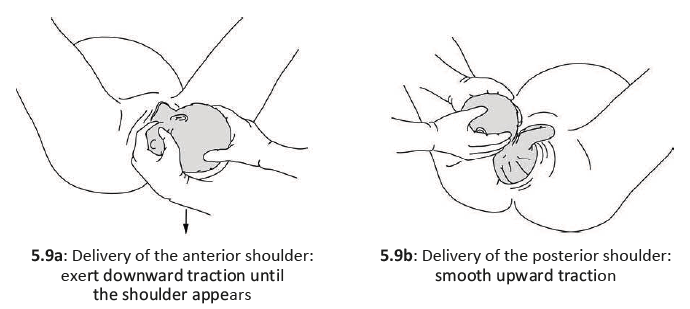

5.3.4 Delivery of the shoulders

After the baby’s head is born and he or she turns to face the mother’s leg, wait for the next contraction. Ask the mother to give a gentle push as soon as she feels the contraction. Usually, the baby’s shoulders will slip right out. To prevent tearing, try to bring out one shoulder at a time (Figure 5.10).

5.3.5 Delivery of the baby’s body

After the shoulders are born, the rest of the body usually slides out without any trouble. Remember that new babies are wet and slippery. Be careful not to drop the baby!

Put the baby on the mother’s abdomen, dry the baby with a clean cloth and then put a new, clean blanket over him or her to keep the baby warm. Be sure the top of the baby’s head is covered with a hat or blanket. If everything seems OK, give the baby the chance to breastfeed right away. You do not have to wait until the placenta comes out or the cord is cut.

5.3.6 Cutting the cord

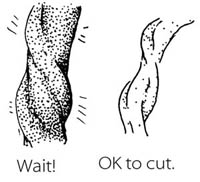

Most of the time, there is no need to hurry to cut the cord right away. Leaving the cord attached will help the baby to have enough iron in his or her blood, because some of the blood in the placenta drains along the cord and into the baby. It will also keep the baby on the mother’s belly which is the best place to be right now. Wait until the cord stops pulsing and looks like it is mostly empty of blood.

BUT if the mother is known to be HIV-infected or her HIV status is not known, it is better to cut the cord soon after you have dried the baby and made sure that he or she is warm.

Use a sterile string or sterile clamp to tightly tie or clamp the cord about two finger widths from the baby’s belly. (The baby’s risk of getting tetanus is greater when the cord is cut far from the body.) Tie a square knot (Figure 5.11).

Put another sterile string or clamp one finger from the first knot. And, if you do not have a clamp on the cord on the mother’s side, add a third knot two fingers from the second knot. Putting a double knot on the cord reduces the risk of bleeding.

Cut after the second tie (e.g. the first tie is approximately 3 cm from the baby’s abdomen and the second is approximately 5 cm). Cut after the 5 cm tie with a sterile razor blade or sterile scissors.

5.4 Immediate care of the newborn baby

Essential newborn care includes the following actions. But note that you will learn about resuscitation of the newborn who is not breathing adequately in Study Session 6.

5.4.1 Clean childbirth and cord care

Principles of cleanliness are essential in both home and health post childbirth to prevent infection to the mother and baby. These are:

- Clean your hands

- Clean the mother’s perineum

- Nothing unclean introduced vaginally

- Clean delivery surface

- Cleanliness in cord clamping and cutting.

The stump of the umbilical cord must be kept clean and dry to prevent infection. Wash it with soap and clean water only if it is soiled. Remember:

- Do not apply dressings or substances of any kind

- If the cord bleeds, re-tie it.

It usually falls off 4–7 days after birth, but until this happens, place the cord outside the nappy to prevent contamination with urine/faeces.

5.4.2 Check the newborn

Most babies are alert and strong when they are born. Other babies start slow, but as the first few minutes pass, they breathe and move better, get stronger, and become less blue. Immediately after delivery, clear airways and stimulate the baby while drying. To see how healthy the baby is, watch for:

- Breathing: babies should start to breathe normally within seconds after birth. Babies who cry after birth are usually breathing well. But many babies breathe well and do not cry at all.

- Colour: the baby’s skin should be a normal colour – not pale or bluish.

- Muscle tone: the baby should move his or her arms and legs vigorously.

All of these things should be checked simultaneously within the first minute after birth. You will learn about this in detail in Study Session 6 of this Module.

5.4.3 Warmth and bonding

Newborn babies are at increased risk of getting extremely cold. The mother and the baby should be kept skin-to-skin contact, covered with a clean, dry blanket. This should be done immediately after the birth, even before you cut the cord.

The mother’s body will keep the baby warm, and the smell of the mother’s milk will encourage him or her to suck. Be gentle with a new baby. The first hour is the best time for the mother and baby to be together, and they should not be separated. This time together will also help to start breastfeeding as early as possible.

5.4.4 Early breastfeeding

If everything is normal after the birth, the mother should breastfeed her baby right away (Figure 5.12). She may need some help getting started. The first milk to come from the breast is yellowish and is called colostrum . Some women think that colostrum is bad for the baby and do not breastfeed in the first day after the birth. But colostrum is very important! It is full of protein and helps to protect the baby from infections.

- Breastfeeding makes the uterus contract. This helps the placenta come out, and it may help prevent heavy bleeding.

- Breastfeeding helps the baby to clear fluid from his nose and mouth and breathe more easily.

- Breastfeeding is a good way for the mother and baby to begin to know each other.

- Breastfeeding comforts the baby.

- Breastfeeding can help the mother relax and feel good about her new baby.

If the baby does not seem able to breastfeed, see if it has a lot of mucus in his or her nose. To help the mucus drain, lay the baby across the mother’s chest with its head lower than its body. Stroke the baby’s back from the waist up to the shoulders. After draining the mucus, help the mother to put the baby to the breast again. You will learn a lot more about breastfeeding in the next Module in this curriculum on Postnatal Care .

Summary of Study Session 5

In Study Session 5 you learned that:

- The second stage of labour begins when the cervix is completely dilated and ends when the baby is delivered. Close attention, skilled care and prompt action are needed from you for a safe clean birth.

- The signs of second stage are when the mother feels an uncontrollable urge to push, she holds her breath or grunts during contractions, she starts to sweat, her mood changes, her external genitals or anus begin to bulge out during contractions, she feels the baby’s head begin to move into the vagina, a purple line appears between her buttocks.

- Check the mother’s vital signs, the fetal heart beat and the descent of the baby’s head at intervals to ensure that labour is progressing normally.

- Watch for warning signs that labour is not progressing sufficiently during the second stage and take appropriate action to refer the mother.

- Support the mother’s pushing during the time of actual delivery.

- If the cord is trapped around the baby’s neck, cut it before the body is delivered — but make sure the mother pushes hard to get the baby out fast.

- Maintain cleanliness throughout the entire process of labour and delivery to prevent infection to the mother and baby.

- Keep the newborn baby warm and make sure it is breathing well.

- Initiate early breast feeding.