Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Very Young Children: First Case Reports on Stability and Developmental Considerations

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Tulane University School of Medicine, 1430 Tulane Ave., #8448, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA.

- PMID: 30345136

- PMCID: PMC6174746

- DOI: 10.1155/2018/7093178

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is purported to start in early childhood but concerns about attenuation of anxiety symptoms over time and the development of emerging cognitive and emotional processing capabilities pose multiple challenges for accurate detection. This paper presents the first known case reports of very young children with GAD to examine these developmental challenges at the item level. Three children, five-to-six years of age, were assessed with the Diagnostic Infant and Preschool Assessment twice in a test-retest reliability study. One case appeared to show attenuation of the worries during the test-retest period based on caregiver report but not when followed over two years. The other two cases showed stability of the full complement of diagnostic criteria. The cases were useful for demonstrating that the current diagnostic criteria appear adequate for this developmental period. The challenges of accurate assessment of young children that might cause missed diagnoses are discussed. Future research on the underlying dysregulation of negative emotionality and long-term follow-ups are needed to better understand the etiology, treatment, and course of GAD in this age group.

Publication types

- Case Reports

- Membership & Supporters

- Facebook Support

- Social Events

- Support Groups

- Fact sheets

- Health Tips

- Personal Stories

- Books & CD's

- Lectures & Workshops

- Participate in Research

- Who does what?

- Find a Therapist

- Product Search

- Shopping Cart

- Terms & Conditions

Hannah, an anxious child

Hannah (not a real person) was a 10-year-old girl from a close, supportive family who was described as 'anxious from birth'. She had been a shy, reserved young girl at pre-school, but she integrated well in grade 1 and began making friends and succeeding academically. She complained several times of severe abdominal pain that was worst in the morning and never present at night. She had missed about 20 days of school during the previous year because of the pain. She also avoided school excursions, fearing the bus would crash. She had difficulty falling asleep and frequently asked her parents for their reassurance.

Hannah was worried that she and members of her family might die. She was unable to sleep at all before a test. She could not tolerate having her parents on a different floor of the house from herself, and she insisted on securing the house to an unnecessary extent in the evenings, fearing intruders. Her insecurity, need for constant reassurance, and school absenteeism were frustrating and upsetting for her parents.

Hannah had no personal history of traumatic events. She exhibits symptoms typical of childhood anxiety disorder, which is thought to occur in about 10% of children, equally in boys and girls before puberty. This type of disorder is diagnosed when anxiety is sufficient to interfere with daily functioning, for example Hannah's school attendance and sleep. These effects can increase and interfere to a progressively greater extent with age-appropriate functioning at home, at school and with peers, and also places sufferers at risk of developing mood disorders or substance abuse disorders in the future.

Many children experience fears; fears that are developmentally normal. Children with anxiety disorders, however, experience persistent fears or other symptoms of anxiety for months. Children can experience all the anxiety disorders experienced by adults. However, they can also experience separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism (failure to speak in certain social situations, thought to be related to social anxiety), which are unique to children. The duration of Hannah's difficulties and the symptoms, including inability to sleep, attend school regularly, go on school excursions, or face tests without extreme distress are all developmentally inappropriate, suggesting an anxiety disorder.

There is a range of common symptoms seen in anxious children. Symptoms involving thoughts include worrying, requests for reassurance, 'what if.' questions, and upsetting obsessive thoughts. Common symptoms involving behaviours include difficulty in separation, avoiding feared situations, tantrums when faced with fear, 'freezing' or mutism in feared situations, and repetitive rituals, or compulsions. Common symptoms involving feelings include panic attacks, hyperventilation, stomachaches, headaches and insomnia.

To screen quickly for one or more anxiety disorders in children, four questions are often useful:

- Does the child worry or ask for parental reassurance almost every day?

- Does the child consistently avoid certain age-appropriate situations or activities, or avoid doing them without a parent?

- Does the child frequently have stomachaches, headaches, or episodes of hyperventilation?

- Does the child have daily repetitive rituals?

These questions address the main thoughts, behaviours and feelings related to anxiety seen in children.

Megan Rodgers wishes to acknowledge an article entitled 'Childhood Anxiety Disorders' written by Dr Manassis, a Staff Psychiatrist at the Hospital for Sick Children and the Center for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Ontario, on which this article is based.

Written by Megan Rodgers ADAVIC Volunteer June 2004

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Call for papers

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 32, Issue 6

- Very early family-based intervention for anxiety: two case studies with toddlers

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5603-6959 Dina R Hirshfeld-Becker 1 , 2 ,

- Aude Henin 1 , 2 ,

- Stephanie J Rapoport 1 ,

- Timothy E Wilens 2 , 3 and

- Alice S Carter 4

- 1 Child CBT Program, Department of Psychiatry , Massachusetts General Hospital , Boston , Massachusetts , USA

- 2 Department of Psychiatry , Harvard Medical School , Boston , Massachusetts , USA

- 3 Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry , Massachusetts General Hospital , Boston , Massachusetts , USA

- 4 Department of Psychology , University of Massachusetts Boston , Boston , Massachusetts , USA

- Correspondence to Dr Dina R Hirshfeld-Becker; dhirshfeld{at}partners.org

Anxiety disorders represent the most common category of psychiatric disorder in children and adolescents and contribute to distress, impairment and dysfunction. Anxiety disorders or their temperamental precursors are often evident in early childhood, and anxiety can impair functioning, even during preschool age and in toddlerhood. A growing number of investigators have shown that anxiety in preschoolers can be treated efficaciously using cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) administered either by training the parents to apply CBT strategies with their children or through direct intervention with parents and children. To date, most investigators have drawn the line at offering direct CBT to children under the age of 4. However, since toddlers can also present with impairing symptoms, and since behaviour strategies can be applied in older preschoolers with poor language ability successfully, it ought to be possible to apply CBT for anxiety to younger children as well. We therefore present two cases of very young children with impairing anxiety (ages 26 and 35 months) and illustrate the combination of parent-only and parent–child CBT sessions that comprised their treatment. The treatment was well tolerated by parents and children and showed promise for reducing anxiety symptoms and improving coping skills.

- childhood anxiety disorders

- preschoolers

- cognitive behavioural therapy

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2019-100156

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Anxiety disorders affect as many as 30% of children and adolescents and contribute to social and academic dysfunction. These disorders or their temperamental precursors 1 are often evident in early childhood, with 10% of children ages 2–5 already exhibiting anxiety disorders. 2 Anxiety symptoms in toddlerhood 3 and preschool age 4 show moderate persistence and map on to the corresponding Diagnostic and Statistic Manual anxiety disorders. 5 6 Well-meaning parents, particularly those with anxiety disorders themselves, may respond to a child’s distress around separating from parents or being around unfamiliar children by decreasing the child’s exposure to these situations, for example, by not having the child start preschool or by not leaving the child with a childcare provider to go to work or socialise. In the short term, such responses may impair concurrent family function, strain the parent–child relationship, and reduce the child’s opportunity for increased autonomy, learning and social development. 7 These avoidant strategies may initiate a trajectory where the child takes part in fewer and fewer activities, leading to social and academic dysfunction. 8

Members of our research team began championing the idea of early intervention with young anxious children over two decades ago, with the aim of teaching children and their parents cognitive–behavioural strategies to manage anxiety before their symptoms became too debilitating. 8 Although cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) has since emerged as the psychosocial treatment of choice for treating and preventing anxiety, 9 10 at that time, most protocols that had been empirically tested were aimed at children ages 7 through early adolescence, with only a few enrolling children as young as age 6. 11 We developed and tested a parent–child CBT intervention (called ‘Being Brave’) and reported efficacy in children as young as 4 years. 12 13 The treatment involved teaching parents about fostering adaptive coping and implementing graduated exposures to feared situations, and modelling how to teach children basic coping skills and conduct exposures with reinforcement. In parallel, a growing number of investigators confirmed that anxiety in preschoolers could be treated efficaciously using CBT administered either by training parents to apply CBT strategies with their children or through direct intervention with children. 14 15 Early family-based intervention using cognitive–behavioural strategies was shown to reduce rates of later anxiety and to attenuate the onset of depression in adolescence in girls. 16

The question remains as to whether early intervention can be extended even younger. With few exceptions, 17 18 most investigators do not offer direct CBT for anxiety to children under age 3 or 4, 15 and none to our knowledge have treated anxiety disorders with CBT in children under age 2.7. 15 However, we reasoned that since toddlers can also present with impairing symptoms, and since behaviour strategies can be feasibly applied even in preschoolers with poor language ability, 19 it ought to be possible to apply family-based CBT for anxiety to toddlers as well. We therefore present two cases of anxious children, ages 26 and 35 months, treated with parent and child CBT.

Recruitment

Parents of children ages 21–35 months were recruited for a pilot intervention study (a maximum of three cases) using advertisements to the community. To be included, children had to be rated by a parent as above a standard deviation on the Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire Fear or Shyness Scale 20 and could not have global developmental delays, autism spectrum disorder or a primary psychiatric disorder other than anxiety.

Children were evaluated for behavioural inhibition using a 45 min observational protocol. 21 Parents completed a structured diagnostic interview about the child (Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present and Lifetime) that has been used with parents of children as young as 2 years; 22 23 an adapted Coping Questionnaire, 24 in which parents assessed the child’s ability to cope with their six most feared situations; and questionnaires assessing child symptoms (Child Behavior Checklist 1-1/2-5 (CBCL), 25 subscales from the Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (ITSEA) 26 ), family function (Family Life Impairment Scale 27 ) and parental stress (Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 28 ). These assessments were repeated following the intervention, with the exception of the behavioural observation for the child initially rated ‘not inhibited’. The clinician rated the global severity of the child’s anxiety on a 7-point severity scale (Clinician Global Impression of Anxiety 29 ) at baseline and rated global severity and improvement of anxiety postintervention. Participant engagement in session and adherence to between-session assignments were rated by the clinician at each visit, and parents completed a post-treatment questionnaire rating the intervention.

Children were treated by the first author, a licensed child psychologist, using the ‘Being Brave’ programme. 13 It includes six parent-only sessions, eight or more parent–child sessions and a final parent-only session on relapse prevention. An accompanying parent workbook reinforces the information presented. Parent-only sessions focus on factors maintaining anxiety; monitoring the child’s anxious responses and their antecedents and consequences; restructuring parents’ anxious thoughts; identifying helpful/unhelpful responses to child anxiety; modelling adaptive coping; playing with the child in a non-directive way; protecting the child from danger rather than anxiety; using praise to reinforce adaptive coping; and planning and implementing graduated exposure. Child–parent sessions teach the child basic coping skills; and focus on planning, rehearsing and performing exposure exercises, often introduced as games, with immediate reinforcement. All parent–child sessions were preserved from the original protocol, but two sessions teaching the child about the CBT model, relaxation and coping plans were omitted, as were two sessions in which the (older) child does a summary project and celebrates gains. Up to six child–parent sessions focusing on exposure practice were included.

In the cases that follow, identifying details are disguised to protect participants’ privacy. Parents of both children provided written consent for the publication of de-identified case reports.

Background information

‘J’ was a 35-month-old girl, the third of three children of married parents. She had congenital medical problems requiring multiple surgeries, and she continued to undergo regular follow-up procedures. J met the criteria for separation anxiety disorder with marked severity, mild social phobia and mild specific phobia. Although she was able to attend her familiar day care if handed directly to a teacher and attend a gymnastics class with a friend while her mother waited in the hall, J showed great distress if apart from her mother at home. If her mother left her sight (eg, to use the bathroom), J would sob, cry and try to open the door to get in. If her mother went out and left her with a family member, J would fuss, cry and try to come along, and would continually ask to video-call her, so her mother would cut her outings short. J also had fears of doctors’ visits, of riding in the car seat, and of walking independently up and down a staircase at home. She would approach new children only with assistance from her mother, and she was afraid to take part in gymnastics performances.

J also had some mood symptoms possibly related to her medical issues. She would intermittently have days when she was much more clingy, had uncharacteristically low energy, would want to be held, and would say ‘ow, ow’ if put down to stand. She also had difficulty staying asleep and would periodically wake up with respiratory difficulties.

‘K’ was a 26-month-old boy, the only child of married parents. He met the criteria for moderate separation anxiety disorder. Although able to go to a day care he had been attending since infancy, he showed distress at drop-off particularly at the start of each week, crying for 15 min. He feared being apart from his mother in the house: he could not tolerate his mother leaving the room even to change clothes and would cry if his mother left the playroom while K played with his father. He would get distressed if his father took him on outings without his mother. He could not be dropped off at a childcare centre at his parents’ gym, leading to their avoiding exercise. He slept in his own crib, rocked to sleep by a parent, but would wake in a panic (alert but distressed) two to three times per month, crying for over an hour until his parents took him into their bed. K also was very particular about where objects were placed in the playroom and would fuss if they were put in the wrong place. He got anxious about deviations in routine (eg, taking a different path on a walk) and had trouble throwing things away (eg, used Band-Aids).

Intervention Feasibility and Outcomes

To demonstrate feasibility, the application of the treatment protocol with both participants is summarised in table 1 . Both participants completed the treatment, in 11 and 10 sessions, respectively. For each, session engagement was rated ‘moderately’ or ‘completely engaged’ at all but one session, and homework adherence was rated as ‘moderate work’ to ‘did everything assigned’ at all but one session.

- View inline

Application of treatment protocol with both participants

The quantitative results of the treatment are presented in table 2 . Both children were rated by the clinician as having shown ‘much improvement’ (Clinician Global Impression of Anxiety-Improvement 1 or 2), and both showed changes in quantitative measures of anxiety and family function. In both families, parents rated their satisfaction with the treatment as ‘extremely satisfied’, and felt that they would ‘definitely’ recommend the intervention to a friend. They rated all strategies introduced in the intervention as ‘very-’ or ‘moderately helpful’ and rated the change in their ability to help their child handle anxiety as ‘moderately-’ to ‘very much improved’.

Quantitative changes in diagnoses, coping ability, symptoms and family function in both participants

These pilot cases demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of parent–child CBT for toddlers with anxiety disorders. The two participating families completed the treatment protocol and were consistently engaged with in-session exercises and adherent to between-session skills practice. The cases demonstrate that basic coping skills and exposure practice can be conducted with toddlers.

Although efficacy cannot be determined from uncontrolled case studies, the cases did show promising preliminary results. Both children showed a decrease in number of anxiety disorders, both were rated by the clinician (and parents) as either ‘moderately-’ or ‘much improved’ in their overall anxiety, and both showed increases in their parent-rated ability to cope with their most feared situations. Participant 2 improved on all symptom measures as well. Most significantly, his ITSEA general anxiety, separation distress, inhibition to novelty, negative emotionality, compliance and social relatedness scores and his CBCL total score, internalising score and somatic complaints scale score normalised from clinical to non-clinical range. Participant 1 had a more complicated clinical presentation, and whereas her diagnoses and coping scores improved, her parent-rated symptom scores were more mixed, perhaps related to medical problems which impacted sleep. Beyond changes in the children’s behaviour, family life impairment was reduced for both families, and parental stress was decreased out of clinical range for participant 1. Notably, both children also showed gains in areas of competence, including prosocial peer relations and mastery motivation.

This work extends previous research demonstrating that very young children experience impairing levels of anxiety that are amenable to CBT. Previous studies have found that CBT is as efficacious with older preschool-age children with anxiety disorders as it is with school-aged youth, 14 15 with approximately two-thirds of treated youth demonstrating clinically significant improvement. There is increasing recognition that anxiety disorders start early in childhood, and that there are significant advantages to intervening proximally to their onset, before anxiety symptoms crystallise and impairment accumulates. For example, one study of 1375 consecutive referrals (mean age 10.7) to a paediatric psychopharmacology clinic found that the median age of onset of a child’s first anxiety disorder was 4 years. 30 Children seeking treatment for anxiety often present in middle childhood, for symptoms which began much earlier, exposing the child and family to undue stress for years. By teaching parents and very young children skills to manage anxiety, we hope to give families important tools to navigate the developmental transitions inherent in this age range, and to help children develop a sense of mastery during a critical developmental period. Of course, a larger controlled trial is needed to further evaluate this intervention and its efficacy over time.

Assessing and treating toddlers require a developmentally informed approach. Anxiety and other symptoms may present differently in younger children, and because of limited language and cognitive abstraction capabilities toddlers are not as able to describe their fears and worries. Because some forms of anxiety (eg, separation anxiety, stranger anxiety) are normative, determination of clinically significant levels of anxiety requires an understanding of typical development in toddlerhood and the ability to conduct a detailed assessment with parents and the child using measures normed for this age group (such as the ITSEA and CBCL 1-1/2-5). Similarly, implementing CBT with toddlers and preschoolers requires age-appropriate modifications of empirically supported techniques. The adaptations we used included increased parental involvement in planning exposures, decreased focus on child cognitive restructuring (beyond framing the practice as ‘being brave’ and redirecting the child’s attention to rewarding aspects of the situation), and adaptations to exposure exercises to maximise child participation and motivation (practising at times when the child was rested and not irritable, incorporation of games and reinforcers, and allowing the child maximal choice about when/how to carry out the exposure). The cases we presented demonstrate that existing interventions can be effectively adapted and implemented with children as young as 2 years of age. By sharing the information gleaned from our research, we hope to inform providers who may be less familiar with treating children in this age range and increase their confidence in intervening with very young children.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Jordan Holmen for assistance with data checking.

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR ,

- Biederman J ,

- Henin A , et al

- Briggs-Gowan MJ ,

- Carter AS ,

- Bosson-Heenan J , et al

- Finsaas MC ,

- Bufferd SJ ,

- Dougherty LR , et al

- Spence SH ,

- McDonald C , et al

- Briggs-Gowan MJ , et al

- Biederman J

- Cowdrey FA , et al

- Banneyer KN ,

- Price K , et al

- Labellarte MJ ,

- Ginsburg GS ,

- Walkup JT , et al

- Mazursky H , et al

- Yang L , et al

- Kennedy SJ ,

- Ingram M , et al

- Bezonsky R , et al

- Chronis-Tuscano A ,

- O'Brien KA , et al

- Driscoll K ,

- Schonberg M ,

- Carter AS , et al

- Putnam SP ,

- Gartstein MA ,

- Rothbart MK

- Rosenbaum JF ,

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR , et al

- Kaufman J ,

- Birmaher B ,

- Brent D , et al

- Axelson DA , et al

- Kendall PC ,

- Hudson JL ,

- Gosch E , et al

- Achenbach TM

- Jones SM , et al

- Lovibond PF ,

- Lovibond SH

- Hammerness P ,

- Harpold T ,

- Petty C , et al

- Hembree-Kigin T ,

Dina Hirshfeld-Becker earned her undergraduate degree from Harvard and her doctorate in clinical psychology from Boston University, and completed post-doctoral training at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr Hirshfeld-Becker is currently co-founder and co-director of the Child Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Program in the Department of Psychiatry at MGH and an associate professor of psychology in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. The Child CBT Program offers short-term empirically supported CBT with youths ages 3-24, research in novel treatment adaptations, and clinical training in CBT, including on-line training courses. She pioneered the development and empirical evaluation of one of the first manualized cognitive-behavioral intervention protocols for anxiety in 4- to 7-year-old children, the “Being Brave” program, and has been exploring its use with children with autism spectrum disorder and with younger toddlers and their parents. Dr Hirshfeld-Becker has published numerous articles, reviews, and chapters. Her main research interests include the etiology, development, and treatment of childhood psychiatric disorders, particularly anxiety disorders, and in the study of early risk factors for these disorders.

Contributors DRHB designed the study with input from ASC, AH and TEW. DRHB developed the intervention and treated the cases, and DRHB, SJR and AH collected, scored, analysed and tabulated the data. DRHB wrote the first draft of the manuscript, SJR drafted parts of the Results section, and AH made significant additions to the Discussion section. AH, ASC and TEW revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. DRHB incorporated all of their edits and finalised the document. All authors approved the final version and are accountable for ensuring accuracy and integrity of the work.

Funding This work was supported by a private philanthropic donation by Mrs. Eleanor Spencer.

Competing interests DRHB and AH receive or have received research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). ASC reports receipt of royalties from MAPI Research Trust on the sale of the ITSEA, one of the instruments included in the manuscript. TEW receives or has received grant support from the NIH (NIDA), and is or has been a consultant for Alcobra, Neurovance/Otsuka, Ironshore and KemPharm. TEW has published a book, Straight Talk About Psychiatric Medications for Kids (Guilford Press); and co/edited books: ADHD in Adults and Children (Cambridge University Press), Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry (Elsevier), and Massachusetts General Hospital Psychopharmacology and Neurotherapeutics (Elsevier). TEW is co/owner of a copyrighted diagnostic questionnaire (Before School Functioning Questionnaire), and has a licensing agreement with Ironshore (BSFQ Questionnaire). TEW is Chief of the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and (Co)Director of the Center for Addiction Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. He serves as a clinical consultant to the US National Football League (ERM Associates), US Minor/Major League Baseball, Phoenix House/Gavin Foundation and Bay Cove Human Services.

Patient consent for publication Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Ethics approval All procedures were approved by our hospital’s institutional review board (Partners Human Research Committee, 2018P000376), and parents provided informed consent for themselves and their child.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

GAD-Specific Cognitive Behavioral Treatment for Children and Adolescents: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 25 April 2019

- Volume 43 , pages 1051–1064, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sean Perrin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5468-4706 1 , 2 nAff3 ,

- Denise Bevan 1 nAff4 ,

- Susanna Payne 1 &

- Derek Bolton 1 , 2

13k Accesses

14 Citations

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) designed to target generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in youth was examined in a pilot feasibility trial. Participants (aged 10–18 years) were randomized to either 10 weeks of individual CBT (n = 20) or supported wait-list (n = 20). Diagnostic status (primary outcome) was assessed blindly at post-treatment for both groups, and at a 3-month follow-up for treated participants. Two participants failed to complete CBT and retained their GAD during the trial. Intention-to-treat analyses revealed large between-group differences in favor of CBT at post-treatment for remission from GAD (80% vs 0%) and comorbid disorders (83% vs 0%), and for all secondary outcomes (child and parent-reported). All gains were maintained at 3-month follow-up in the CBT group. Consistent with the treatment model, significant pre- to post-treatment reductions in several cognitive processes were found for CBT but not wait-listed participants, with these gains maintained at follow-up. Further investigations are warranted. Trial registry: ISRCTN.com Identifier ISRCTN50951795

Similar content being viewed by others

Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Metacognitive Therapy: Moderators of Treatment Outcomes for Children with Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Monika Walczak, Sonja Breinholst, … Barbara Hoff Esbjørn

Evaluation of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Efficacy in the Treatment of Separation Anxiety Disorder in Childhood and Adolescence: a Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

Ludovica Giani, Marcella Caputi, … Simona Scaini

Effectiveness of an Individualized Case Formulation-Based CBT for Non-responding Youths with Anxiety Disorders

Irene Lundkvist-Houndoumadi, Mikael Thastum & Esben Hougaard

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

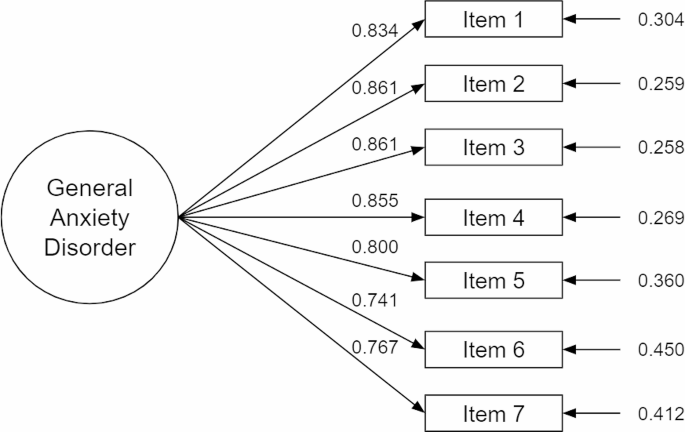

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) is a chronic condition characterized by excessive and uncontrollable worry about a number of events and activities, accompanied by > 3 somatic symptoms (one for children) and clinically significant distress or impairment for no less than 6 months [American Psychological Association (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013 ]. The 12-month prevalence of GAD in children and adolescents aged 6–18 years (hereafter youth) in the community is 1–3%, with affected individuals experiencing high rates of comorbidity, functional impairments, and a chronic course (Copeland et al. 2014 ). GAD is also one of the most commonly occurring comorbid disorders in youth seeking treatment for anxiety (Kendall et al. 2010 ). The evidence for the efficacy of transdiagnostic and GAD-specific treatments for GAD in youth is now briefly reviewed.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the two most studied treatments for youth with GAD, either as a primary disorder or comorbid to another anxiety disorder (Wang et al. 2017 ). The most frequently evaluated CBT approaches, including the coping cat (CC) program (Kendall 1990 ), are transdiagnostic for anxiety disorders, not disorder-specific. The preponderance of transdiagnostic CBT programs for childhood anxiety reflects a general consensus that while specific anxiety disorders can be identified in youth, comorbidity is the rule rather than exception, and can be effectively treated with a broad-based protocol focused on ‘anxiety’ (cf., Hudson et al. 2015 ; Kendall et al. 2010 ; Waite and Creswell 2014 ).

Meta-analytic studies find that SSRIs and transdiagnostic CBT programs are superior to no treatment for youth with anxiety disorders, most frequently a combination of GAD, separation anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobias (James et al. 2013 ; Wang et al. 2017 ). Approximately 60% achieve remission from at least one of their comorbid anxiety disorders, with gains maintained up to 36-weeks. As outcomes for GAD are not reported, the effectiveness of transdiagnostic approaches for this this condition remain unclear (Ewing et al. 2015 ). However, there is some evidence for the efficacy of the transdiagnostic approach Cool Kids (Lyneham et al. 2003 ). Hudson et al. ( 2015 ) combined data from controlled and uncontrolled trials (at total of 848 participants) of this approach and observed a 57.6% remission rate for GAD at 3–12 months post-treatment. This is consistent with response rates for GAD reported in several early cases studies involving treatments based on the CC approach (Eisen and Silverman 1993 , 1999; Kane and Kendall 1989 ).

An empirical question arises whether outcomes for childhood GAD specifically can be improved by drawing upon models of GAD, most often developed with adults, to modify existing transdiagnostic CBT programs, or to develop new GAD-specific treatments. As an example of the former, Waters et al. (Waters et al. 2008 ) administered five sessions of CC (Kendall 1990 ) followed by five sessions of interpersonal therapy for adolescent depression (IPT-A; Mufson et al. 1994 ), to four adolescents with a primary diagnosis of GAD. All four participants were free of GAD at post-treatment, with clinically significant improvements on self-report measures of trait anxiety, depression, and interpersonal skills. The authors added IPT-A interventions based on the observation that excessive reassurance seeking from family members is common in those with GAD, and that interpersonal difficulties (generally) are more frequent in individuals with GAD compared to those with other anxiety disorders, and are associated with poorer outcomes from traditional CBT (Borkovec et al. 2002 , 2003 ; Uhmann et al. 2010 ).

As an alternative approach to modifying existing transdiagnostic CBT programs for childhood anxiety, efforts have been made to develop and test GAD-specific CBT approaches (reviewed below) that draw upon a model of worry and GAD in adults (Laval model), developed by Dugas et al. ( 1998 ). Central to the model is the trait-like phenomenon intolerance of uncertainty (IU), originally described as “cognitive, emotional and behavioral reactions to uncertainty in everyday life situations” (Freeston et al. 1994 , p. 792). The definition has evolved over time to include: “an individual’s dispositional incapacity to endure the aversive response triggered by the perceived absence of salient, key, or sufficient, information, and sustained by the associated perception of uncertainty” (Carleton 2016 , p. 31). When confronted with uncertainty, persons high in IU may engage strategies that make bouts of excessive worrying more likely or more difficult to stop (Dugas et al. 1998 ). These strategies, also mentioned in other models of GAD, include: a tendency to view uncertain outcomes as ‘threats’ that will either be difficult to prevent or to cope with if they occur ( Negative Problem Orientation –NPO); the use of distraction and suppression to reduce intrusive images of the feared outcomes and distress ( Cognitive Avoidance –CA); and dysfunctional appraisals about the nature of worries, including the belief that worrying may be necessary to prevent or lessen the impact of the feared outcomes ( Positive Beliefs About Worry –PBW).

There is now a growing body of research on the applicability of the Laval model, and in particular—the central role played by IU, to the severity of childhood worry and anxiety. Laugesen et al. ( 2003 ) found that scores on measures of IU, CA, PBW, and NPO contributed significantly to the variance in total worry, with scores on the four measures correctly classifying 72.8% of adolescents (aged 14–18 years) into moderate and high worry groups. Using measures of IU, CA, and PBW, Fialko et al. ( 2012 ) fit a path model wherein IU acted as a higher-order vulnerability factor for CA and PBW, with the three variables together influencing the severity of self-reported worry and anxiety in adolescents (aged 13–19 years). The model fit in children (aged 7–12 years) had a similar hierarchical structure but without positive beliefs about worry. Donovan et al. ( 2016 ) found that IU, CA, NPO, PBW, and negative beliefs about worry accounted for 59% of the variance in worry in children (aged 8–12 year). However, only negative beliefs about worry and CA were unique predictors, accounting for 25% and 14% of the variance. In a longitudinal study of adolescents (mean age 12.5 years), Dugas et al. ( 2012 ) found that IU and worry interacted in a bidirectional and reciprocal relationship, with changes in IU producing changes in worry and vice versa. A recent meta-analysis of 31 studies examining the relationship between IU and worry, found that IU accounted for 39.7% of the variance in child worry and 35% of the variance in child anxiety (Osmanagaoglu et al. 2018 ). This (non-exhaustive) review, suggests that processes from the Laval model of worry may be important targets for intervention in the treatment of youth with GAD.

As originally developed for use with adults, the GAD-specific treatment based on the Laval model involved modules targeting IU, PBW, NPO, and CA through worry-awareness training, exposure to situations involving uncertainty, modification of maladaptive beliefs about worries and the nature of everyday problems, and imaginal exposure to the content of worries (Dugas and Robichaud 2007 ). Trials of this treatment in adults report remission rates from GAD in the range of 70–88%, with gains maintained up to 24-months (Ladouceur et al. 2000 , 2004 ; Dugas et al. 2003 , 2010 ). Consistent with the assumptions of the Laval model of worry, changes in IU during treatment for adults with GAD has been found to be associated with changes in worry; whether the treatment was based on the Laval model (Ladouceur et al. 2000 ) or not (Bomyea et al. 2015 ; Torbit and Laposa 2016 ).

To date, three case series have been conducted that evaluate GAD-specific CBT approaches that target the four cognitive processes from the Laval model. Leger et al. ( 2003 )administered an average of 13.2 sessions of CBT to four adolescents (aged 14–18 years; no drop-outs), 43% of whom were free of their GAD diagnosis at post-treatment, declining to 28.6% at the 12-month follow-up. Payne et al. ( 2011 ) modified this treatment for use with children and younger adolescents. After an average of 9.7 sessions (and no drop-outs), 81% of the 16 participants (aged 7–17 years) were free of their GAD diagnosis, with 59% losing their comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders, and large effect size reductions in child-reported worry and anxiety. Wahlund et al. ( 2019 ) administered a 12-session, IU-focused CBT program to 12 adolescents (aged 13–18 years; no drop-outs) with excessive worry, nine of whom had GAD. The adolescent-focused sessions were supplemented by an internet-delivered program for parents designed to teach them about worry, IU, and helpful parenting behaviors. At post-treatment, 58.3% of the adolescents were rated as much or very much improved by independent clinicians, rising to 66% at the three-month follow-up. Moderate to large effect sizes were observed for adolescent-and parent-reported worry, anxiety, depression and global functioning at post-treatment (maintained at follow-up). Moderate to large effect-size reductions were also reported for self-report measures of IU, NPO, CA, and PBW, although the pre-to-post-treatment changes for PBW were non-significant.

To date, there has been one RCT of a GAD-specific treatment for youth. Holmes et al. ( 2014 ) evaluated the efficacy of a group-based, child- and parent-focused, CBT program targeting the four cognitive processes from the Laval model, as well as perfectionism and sleep difficulties. Participants were 42 children aged 7–12 years with a primary diagnosis of GAD, randomized to 10-weeks of the group treatment plus two 90-min booster sessions, or a 12-week wait-list. Parents completed a parallel, 7-session group. Three of the 20 participants (15%) in the CBT condition dropped out. Based on intention-to-treat analyses, 52.9% of the children in the CBT group were free of their GAD (and 17.6% free of all diagnoses) at post-treatment, rising to 80% at three-month follow-up. None of the children in the wait-list group lost their GAD or comorbid diagnoses. At post-treatment, there were no significant within-subject or between-group changes on child-report measures of IU, CA, NPO, and PBW. However, at follow-up, and relative to baseline, significant reductions in the moderate to large range were observed for treated participant’s scores on the measures of IU, CA, NPO–but not PBW.

The current study was designed as a randomized controlled, pilot feasibility trial with the primary aim of assessing the tolerability and efficacy of a child-friendly adaptation of the GAD-specific CBT approach described in Dugas and Robichaud ( 2007 ). This would be only the second randomized control trial of a GAD-specific treatment with children and the first to include adolescents. As such, the design incorporated a delayed-treatment (wait-list) condition as the control group. Based on the results of a previous uncontrolled trial of the current treatment approach (Payne et al. 2011 ), as well as outcomes reported in the literature for GAD-specific treatments for youth (described above), we anticipated that the current treatment would be well tolerated (i.e., < 10% drop-outs), and would yield differences in GAD remission relative to wait-list controls in excess of 50% at post-treatment. Based on the results from the two GAD-specific treatment trials that administered measures of IU, CA, NPO, and PBW (Holmes et al. 2014 ; Wahlund et al. 2019 ), we anticipated moderate to large effect-size differences for the four cognitive measures between CBT and wait-list at post-treatment, and between pre-treatment and post-treatment/follow-up for treated participants.

Participants

The 40 participants (aged 10–18 years) were recruited from standard referrals to the 10 child and adolescent mental health services and a specialist child anxiety disorders clinic affiliated with the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (United Kingdom). The Trust serves a catchment area of approximately 1.3 million inhabitants from diverse socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds. Referrals may be initiated by the parent (or adolescent), family doctor, school, or social services; all clinical care is free of charge.

Inclusion criteria for the trial were as follows: (1) Aged 10–18 years; (2) referred for treatment of anxiety; (3) a current, primary diagnosis of DSM-IV GAD; (4) no other psychiatric problems in need of more urgent treatment (including self-injurious thoughts/behaviors or substance use/abuse); (5) no concurrent psychological or pharmacological treatment for any disorder; and (6) the absence of moderate to severe learning difficulties as evidenced in the medical or school records or as reported by the referrer/parent at the pre-trial screening. No other inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied. All participants were fluent in English.

The study was planned as a Phase 0/1 RCT with the participants randomly allocated, in equal proportions (no stratification), to either 10 weeks of either individual, GAD-specific cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) or a supported wait-list (WL). Participants in both groups completed primary and secondary outcome measures at pre- and post-treatment/wait-list. Wait-listed participants who still required treatment at the end of the 10-week wait-list were provided immediate treatment in the clinic, either the GAD-specific CBT tested in this trial or another appropriate treatment (these data are not included in this study). CBT participants (only) were reassessed at a 3-month follow-up.

Following referral, an initial phone screening was carried out to determine if the primary complaint was GAD, and if positive, written information about the trial was sent to the family, along with a date for a face-to-face assessment with the trial coordinator. All participants attended the face-to-face assessment with at least one parent. If all inclusion criteria were met at the face-to-face assessment, the trial coordinator contacted the lead author who accessed an online, random allocation programme created by King’s College London Clinical Trials Unit for the purposes of this trial. The trial coordinator revealed the allocation to the family and told them they could withdraw from the trial at any time without negatively impacting their access to treatment. At all stages, clinical need overrode the trial protocol.

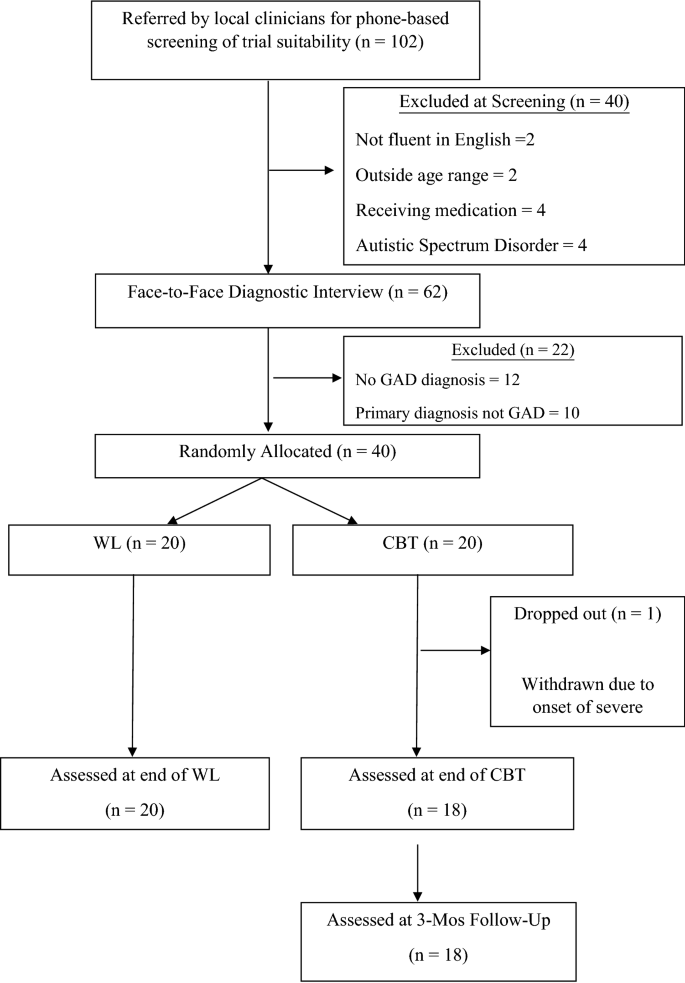

Figure 1 presents the CONSORT diagram of participant flow through the trial. Complete data were available for 38 of the 40 study participants (95%). All WL participants (n = 20) completed the 10-week wait-list, including all diagnostic interviews, secondary outcome measures, and cognitive process measures at pre- and post-wait-list. All but two of the CBT participants (both adolescents) completed treatment. One CBT participant dropped out after four sessions because they wanted to focus on social anxiety and not GAD, and another was removed from the trial after four sessions because of the onset of suicidal thoughts in response to a family crisis that began after the trial treatment had commenced. This crisis was unrelated to the participant’s GAD or treatment. While both non-completers were out of the trial, they continued to receive treatment in the clinic where the trial was carried out. The investigators were aware that they continued to suffer from GAD at the time that their (per-protocol) post-treatment and 3-month follow-up assessments would have occurred. Thus, their pre-treatment data (all) was carried forward to post-treatment and follow-up. Data for all primary, secondary, and cognitive process measures administered at pre-, post-treatment, and 3-month-follow-up were available for the remaining 18 CBT participants.

CONSORT flow chart

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was defined as the difference in the proportion of participants with a GAD diagnosis in the CBT versus WL groups at post-treatment/wait-list. GAD was assessed with the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Child and Parent Report Version (ADIS-C/P; Silverman and Nelles 1998 ). All participants, and at least one parent/primary caregiver, were interviewed separately with ADIS-C/P and the information combined to arrive at the diagnostic profile and the clinician’s separate severity ratings (0–8) for GAD and any comorbid disorders. ADIS-C/P interviews were carried out by fully qualified, doctoral-level clinical psychologists with extensive training in the use of the ADIS-C/P in clinical and research contexts. Assessors of the primary outcome at post-treatment, and for CBT participants only—the 3-month follow-up, were independent of the trial and the clinic where the trial was carried out. The assessors were blinded to the participant’s treatment allocation and history. Participants (and their parents) were given written instructions just prior to the post-treatment/wait-list and follow-up assessments not to disclose their treatment history.

Secondary Outcomes

In order to assess a broader range of outcomes than remission from GAD, several child-, parent-, and clinician-completed measures of symptoms, overall functioning, and quality of life, were administered to all participants at pre- and post-treatment/wait-list, and for CBT participants (only) at the 3-month-follow-up. The secondary outcome measures have been validated for use with children and adolescents, have excellent psychometric properties, and are routinely used in trials of anxiety disordered youth. The secondary outcome measures were as follows: (1) Worry Severity (child-report): Penn State Worry Questionnaire for Children (PSWQ-C; Chorpita et al. 1997 ); (2) Anxiety/GAD Symptoms (child and parent-report): Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders—Child and Parent Report Version (SCARED-C/P; Birmaher et al. 1997 ); (3) Depression (child and parent-report): Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-Child and Parent Report Versions (MFQ-C/P; Angold et al. 1995 ); (4) Conduct Problems, Peer Difficulties, Overall Impairment (parent-report): Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire-Parent Version (SDQ-P; Goodman 1997 ); (5) Global Functioning (clinician-report): Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; Shaffer et al. 1983 ); and (6) Quality of Life (child- report): Pediatric Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (PQ- LES-Q; Endicott et al. 2006 ).

Cognitive Processes from the Laval Model of Worry

At the time this trial was planned, measures of the four cognitive processes from the Laval model of worry (IU, CA, NPO, PBW), adapted and formally validated for use with children and adolescents, did not exist. For the purposes of this trial, a five-item version of each of the four self-report measures used by Dugas et al. ( 1998 ) to assess IU, CA, NPO, and PBW in adults were created (Fialko et al. 2009 ; Fialko et al. 2012 ). Briefly, for each of the four scales, five items were chosen from the original questionnaire based on these items having the highest item-total correlations, or item-subscale/factor loadings for measures with subscales. The five-item scales were then given to clinically-referred and non-referred children and adolescents, and small changes made to increase comprehensibility. The five-item measures of IU, CA, and PBW were also administered to 515 British youth (aged 7–19 years) and found to have high levels of internal consistency, similar factor structures as the full-length originals, and to correlate (positively) in the moderate to large range with self-reported worry and anxiety (Fialko et al. 2012 ). Swedish-language versions of the same five-item cognitive process measures used in this trial were found to be sensitive to the effects of an IU-focused CBT program for excessive worry in adolescents (aged 13–18 years) (Wahlund et al. 2019 ).

Intolerance of Uncertainty (IU) was assessed using the child-report, Brief Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (Brief-IUS; Fialko et al. 2012 ). The scale is comprised of the following five-items from the 27-item IUS for adults (Freeston et al. 1994 ): Not knowing what may happen next makes my life horrible; I can’t be relaxed if I don’t know what will happen tomorrow; When I am not sure about something, I can’t get on with it; When I am not sure what will happen next, I can’t do things very well; Not knowing what may happen next can make me scared or sad. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale (1 = Not all like me; 5 = Completely like me); higher total scores indicate higher IU. The internal reliability coefficients for the Brief-IUS for the 40 participants in this study were: pre-treatment/wait-list α = .89; post-treatment/wait-list α = .95.

Cognitive Avoidance (CA) was assessed using the Brief Cognitive Avoidance Questionnaire (Brief-CAQ; Fialko et al. 2012 ), comprised of the following 5-items from the 25-item CAQ for adults (Sexton and Dugas 2008 ): There are things that I would rather not think about; I have thoughts that I try to avoid; To avoid thinking about things that upset me, I force myself to think about something else; I avoid doing anything that reminds me of things I don’t want to think about; When I have a scary picture in my mind, I say things to myself in my head to replace the picture. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale (1 = Never; 5 = always); higher total scores indicate higher CA. Internal reliability coefficients for the Brief-CAQ for the 40 participants in this study were: pre-treatment/wait-list α = .83; post-treatment/wait-list α = .90.

Positive Beliefs About Worry (PBW) were assessed using the Brief Why Worry Scale-II (Brief-WW-II; Fialko et al. 2012 ) comprised of the following 5-items from the 25-item WW-II for adults (Holowka et al. 2000 ): If I worry in advance, I will be less upset if something bad happens; Worrying can stop bad things from happening; Worrying helps me find a better way to do things; Worry helps me to get started on things I must do; The fact that I worry shows that I am a good person. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale (1 = Not all true of me; 5 = Completely true of me); higher total scores indicate higher PBW. Internal reliability coefficients for the Brief-WW-II for the 40 participants in this study were: pretreatment/wait-list α = .77; post-treatment/wait-list α = .79.

Negative Problem Orientation (NPO) was measured with the Brief Negative Problem Orientation Questionnaire (Brief-NPOQ, unpublished measure), comprised of five-items drawn from the 12-item NPOQ for adults (Robichaud and Dugas, 2005 ): I often doubt my ability to solve problems; Often my problems seem unmanageable; When I try to solve a problem I often question my own ability; I often get the impression that my problems can’t be solved; My first reaction to a problem is to question my own ability . Each item is rated on a 5-point scale (1 = Not all true of me; 5 = Completely true of me); higher scores indicate higher NPO. This scale has not been formally validated. However, the five items overlap with those from five-item measure of NPO used in the trial by Holmes et al. ( 2014 ), which found the NPO measure to be sensitive to the effects of a GAD-specific treatment based on the Laval model in children (aged 7–12 years). Internal reliability coefficients for the scale in the 40 participants in the present study were: pre-treatment/wait-list α = .93; post-treatment/wait-list α = .96.

Treatment Protocol

Cognitive behavioral therapy for gad.

The treatment was a child-friendly adaptation of the CBT for GAD approach described in Dugas and Robichaud ( 2007 ). As described by Dugas and Robichaud ( 2007 ), treatment proceeds sequentially through six stages/modules: (1) worry awareness training; (2) planned exposure to uncertainty; (3) modification of dysfunctional beliefs about worry; (4) modified problem-solving training; (5) imaginal exposure to unpleasant images or worries; and 6) relapse prevention. The treatment was successfully piloted with seven adolescents (aged 14–18 years) with GAD by Leger et al. ( 2003 ).

The modular approach and same interventions as described in Dugas and Robichaud ( 2007 ) were retained in the current trial, but the treatment was modified with the aims of making it less abstract and more engaging for children and younger adolescents who might not immediately grasp the relevant processes/concepts (IU, CA, NPO, PBW). To achieve these aims, the therapist would always use language commensurate with the young person’s age and vocabulary. Second, at the start of each module, therapist-led explanations about the cognitive processes and module were kept very brief, always confined to the beginning of a single session. It was explained to the young person that they would learn the relevant concepts more easily through the discussion of a recent worry, behavioral experiments, and imaginal exercises.

Third, the therapist would then elicit a concrete, specific and personalized example of the young person’s worrying from the past week, and use this example to help them notice “real-time” instances of the cognitive process to be targeted in that module, or if necessary because the child could not identify the cognitive process relevant to that module, a cognitive process from another module. For example, if during an exploration of concrete episodes of worry during the third module, the child was unable to identify any dysfunctional beliefs about their worries, the therapist could shift the focus to appraisals about uncertainty, negative problem orientation, cognitive avoidance, or their tolerance for uncertainty and distress related to feared outcomes. In practice, most participants (regardless of age) were able to progress through the modules as described in Dugas and Robichaud ( 2007 ). However, some participants (both children and adolescents) were not able to identify dysfunctional beliefs about worry, and rather than repeatedly engaging the participant in Socratic questioning or other exercises to elicit such beliefs, the therapist had the flexibility to move to the next or previous modules as needed.

Just prior to session 1, the child completed the self-report measure of worry (PSWQ-C), followed by a discussion about the nature of worry/GAD and its treatment, the role played by the four cognitive processes play in the maintenance of worry/GAD, and the importance of self-guided exposure to situations involving uncertainty. Thereafter, each session began with the child completing the worry measure and a brief review of their progress over the past week. From session two onwards, the therapist proceeded through the modules in the sequence described above, but in every session the therapist would elicit a concrete episode of worry from the past week that was then tied to behavioral experiments and imaginal exposures, as described in Dugas and Robichaud ( 2007 ), and with the purpose of: (a) increasing awareness about worry; (b) increasing tolerance for uncertainty; (c) reducing cognitive avoidance; (c) modifying positive beliefs about worry; (d) helping the young person distinguish between genuine problems from worries and to modify negative beliefs about their ability to solve their problems; and (e) testing the young person’s tolerance for uncertainty and feelings of fear in the event of a possible but unlikely feared outcome.

Homework tasks largely followed those described in Dugas and Robichaud ( 2007 ): (1) increasing worry awareness by pausing several times each day to reflect upon, write down, and distinguish between worries about current problems versus hypothetical situations; (2) to plan confrontations each day with situations that involve uncertainty and normally trigger worries (e.g. raising your hand in class when you are not 100% sure of the answer); (3) reducing requests for reassurance from parents/others; (4) practicing behavioral experiments to test dysfunctional beliefs about IU, CA, NPO, and PBW; and (5) engaging in self-guided exposures to the content of worries to test their ability to tolerate uncertainty and the distress. Homework assignments were always discussed in session and reflected experiments/exposures practiced in the session.

Parents were invited to join session one and asked to provide praise/rewards to their child for attempting to complete homework assignments. They were not asked to guide the child in homework exercises or to challenge their child’s maladaptive beliefs about uncertainty, the likelihood of feared outcomes, the child’s problem-solving abilities, or the worries themselves. The concept of secondary gain was introduced such that requests from the child for reassurance about worries can sometimes result in parents trying to alleviate their child’s distress through the provision of rewards or allowing the child to escape from activities that may have prompted a bout of excessive worrying. The child and parents were encouraged to be aware of these contingencies, and the parents to refrain from rewarding avoidance and reassurance seeking. No further guidance was provided to the parents about dealing with their child’s worries or reassurance-seeking.

Sessions 2–10 were one-to-one with the participant, not all of whom were brought to the clinic by their parents for every session. Where there was time and the child agreed, the parents were invited to join for the last 5–10 min of the session to discuss progress. If the therapist or parents wanted a separate meeting one could be scheduled, however, no such meetings were requested by the parents or deemed necessary by the trial therapists. Prior to the start of session 5 (mid-treatment), the child and parents completed several of the baseline symptom questionnaires and progress in treatment discussed with the child and parent separately and together during the session.

Therapist Training and Treatment Adherence

All treatment was provided by two of the authors (Payne and Bevan) under the supervision of the lead author. Both trial therapists were fully qualified doctoral-level clinical psychologists at the time of the trial. Their core professional training focused on cognitive and behavioral interventions. Both had 2–3 years of post-doctoral experience providing CBT interventions to children and/or adults with GAD and other anxiety disorders, under supervision from internationally recognized experts in CBT for child/adult anxiety.

Prior to the trial, Payne and the lead author attended a 1-day clinical workshop by Dugas on the CBT for GAD approach described in Dugas and Robichaud ( 2007 ). After the treatment manual was adapted by the authors for use with children and adolescents (described above), it was successfully piloted with 16, clinically-referred youth (aged 7–18 years) with a primary diagnosis of GAD (Payne et al. 2011 ), with Payne as the sole therapist under the supervision of the lead author. Prior to treating cases in the current trial, Bevan was provided with training in the treatment model/manual by Payne and the lead author, and then observed Payne treat five young people with GAD using the manual. Bevan then treated five youth with GAD who were not included in the current trial using the treatment manual under observation/supervisions from Payne and the lead author.

Treatment adherence was monitored through supervision with the lead author with reference to the trial manual. When permission was given by the participant/parent, a video was made of the therapy session for the purposes of supervision. The videos were used in supervision to facilitate therapist adherence to the manual. Video-recordings were not available for all sessions and were not formally rated for adherence.

Treatment Credibility and Engagement

At the end of session 2, CBT participants were given a 4-item measure of treatment credibility and therapeutic engagement to complete at home and return to the trial coordinator by post. The participants were told the therapist would not see the completed measure or be informed of the child’s views. The measure was developed for the purpose of this trial and based on the widely-used, 6-item Credibility Expectancy Questionnaire developed by Devilly and Borkovec ( 2000 ) used in clinical trials with adults. Prior to the trial, the 4-item measure was administered to 10 children and adolescents (aged 10–14) receiving CBT for an anxiety disorder and feedback obtained on the comprehensibility of the items and the rating scale. As a result of the feedback we added the phrase (‘makes sense’) to the first item (see below). The first three questions address treatment credibility: “Does this treatment seem logical (make sense) to you?” (1 = Not at all, 10 = Makes complete sense); “How certain are you that this treatment will be helpful for your problems?” (1 = Not at all certain, 10 = Completely certain); “How confident would you feel recommending this treatment to a friend with the same type of problems as you?” (1 = Not at all confident, 10 = Completely confident).

The last question addresses therapeutic engagement: “Some people think that the following things are important in therapy sessions: (1) Your therapist is warm and supportive; (2) Your therapist is helping you; (3) You and your therapist get on well; (4) You feel your therapist listens to what you have to say and treats what you say as important; (5) You and your therapist are working together as a team; (6) You and your therapist share the same way of thinking about the problem; (7) You feel that what your therapist is suggesting will be helpful. Overall, how much do you think this has been happening in your sessions so far? Please circle the number that you think is closest to how you feel” (1 = Not at all, 10 = Very much) .”

At the end of session 2, CBT participants rated the therapy as: logical/sensible (M = 8.0, SD = 1.5, Min/Max = 5/10); likely to succeed (M = 8.3, SD = 1.6, Range = 6/10); recommendable to a friend with the same problem (M = 8.5, SD = 1.5, Range = 4/10); and the therapist as warm/engaged (M = 8.9, SD = 1.0, Range = 7/10). The internal reliability coefficient for total scores on the 4-item scale in the treated participants (N = 20) was α = .78.

Wait-List Condition

At the time of allocation, wait-listed participants were provided information about the prevalence of worry and GAD, 10 copies of the self-report measure of worry (PSWQ-C), along with pre-paid envelopes addressed to the trial coordinator, and the date of their first treatment appointment after the 10-week wait-list ended. No information about causes or maintaining factors in relation to worry/GAD, or anxiety broadly, were discussed or presented in written form. The wait-listed participants were asked to complete the worry measure at the end of each week and to return it by post to the trial coordinator. No other measures were completed by the wait-listed participants during weeks 2–9 of the wait-list. The participant and their parents were told that they would receive one phone call per week from the trial coordinator to ask them how they were coping, to remind them of the date of the upcoming treatment appointment, and to complete/return the weekly worry measure. No advice about managing worries or any other difficulties were provided during these phone calls.

Statistical Analyses

Sample size was calculated a priori based on the difference between the proportion of participants in the CBT and WL group with GAD being > 50%, with < 10% drop-outs. To achieve a proportional difference this size, with 80% power, and p = 0.05, required a minimum of 14 participants per group. To account for possible drop-outs, recruitment was set at 20 participants per group. All analyses and reporting were planned on the ‘intention-to-treat’ (ITT) principle. Data for the primary outcome variable was missing for only two trial participants both in the CBT group. However, as both continued to receive treatment from the clinic where the trial was carried out, their status with respect to the primary outcome was known to the authors. With this information, and in consultation with a clinical trials unit, we used a last-observation-carried-forward strategy (LOCF).

For categorical outcomes, 2 × 2 chi squares were used to assess the proportion of CBT and WL participants remitted from their GAD diagnosis (primary outcome) and any comorbid disorders (secondary outcome) at post-treatment. For the remaining secondary outcomes (continuous), we were primarily interested in group differences at post-treatment and carried out one-way analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) with group (CBT vs WL) as the between factor, post-treatment scores as the dependent variable, and pre-treatment scores on the same measure as the covariate.

Within-subject analyses were carried out for participants in the CBT group as they underwent a further assessment at 3-month follow-up. The presence versus absence of GAD and any comorbid disorders at post-treatment versus 3-month-follow-up were examined using 2 × 2 chi squares. For all continuously-measured secondary outcomes and the cognitive process measures, one-way, repeated measure analyses of variance (ANOVA) with three timepoints (pre-, post-treatment, 3-month follow-up), and simple contrasts, were carried out. Between-group and within-subject effect sizes for all (continuous) outcomes and cognitive process measures are reported as partial eta-squared (ɳ 2 = sum of squares for the measure/sum of squares for the measure + sum of squares for error). Partial eta squared (ɳ 2 ) = .02, .13 and .26 reflect small, medium, and large effect sizes (Cohen 1988 ).

Baseline Characteristics of CBT and WL Participants

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics separately for participants in the CBT and WL groups. Between-group comparisons for the CBT and WL on the baseline characteristics in Table 1 were evaluated using 2 × 2 Chi squares and t-tests. No significant between-group differences were observed for any of the listed variables (or for the mean number of disorders), except that more CBT participants had comorbid Separation Anxiety Disorder (χ 2 (1) = 4.8, p = .028).

Not reported in Table 1 , there were no between-group differences in respect of the proportion of participants aged 10-12 years (CBT = 55%; WL = 35%) or the mean number of current DSM-IV diagnoses (including GAD) (CBT = 1.7 (SD = .73); WL = 1.6 (SD = .59). Youth with moderate to severe learning difficulties were excluded from the study. Two participants had a statement of special educational need, one tied to a comorbid diagnosis of ADHD (randomized to CBT) and one tied to a motor disorder (randomized to WL). No other participants had a diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorder or statement of educational need. No standardized measure of socioeconomic status was used in the study. Reflecting the socioeconomic diversity of the catchment area from which all participants were recruited, 10 of the 40 participants (25%) were living in a home where the parents were receiving either income or housing benefits (6 in CBT, 4 in WL).

Primary and Secondary Outcomes (Assessor/Clinician-Rated)

Table 2 present the proportion of participants in the CBT and WL groups meeting criteria for GAD at pre- and post-treatment (primary outcome), and for CBT participants (only) at the 3-month follow-up, and secondary assessor/clinician-rated secondary outcomes. At post-treatment/WL, CBT participants were more likely than WL participants to have remitted from their GAD diagnosis, as well from the comorbid disorders that were preset at pre-treatment/WL. Significant between group differences at post-treatment/WL, in the large range ( ɳ 2 > .26), were found for assessor’s blinded ratings of GAD severity (ADIS-C/P) and clinician-rated global functioning (CGAS). Age and gender of the participant at pre-treatment were unrelated to likelihood of remission GAD (or comorbid diagnoses) at post-treatment or 3-month follow-up for treated participants.

Within-subject analyses were carried out for the CBT participants (pre-, post-treatment, and follow-up). As noted above, significant pre-to-post treatment reductions were observed in the proportion of CBT participants with a GAD diagnosis. No further changes occurred in this variable between post-treatment and month follow-up. Significant time effects, in the large range, were observed for GAD severity (ADIS-C/P; F(2,18) = 44.8, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .78) and Global functioning (CGAS: F(2,18) = 34.6, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .77). Post-hoc comparisons (Bonferroni) revealed significant differences between pre- and post-treatment, between pre-treatment and follow-up only (all p’s = .000).

Secondary Outcomes (Child/Parent-Report)

Table 3 presents results for the secondary outcomes (child- and parent-reports). Significant differences, in the large range of effect sizes, were observed between the CBT and WL groups at post-treatment/WL for all secondary outcomes except conduct problems (parent-report). The results of the within subject analyses for CBT participants on the child/parent-report secondary outcomes and cognitive measures are not reported in Table 3 . A significant effect for time was observed for all child-reported outcomes, including: worry (PSWQ-C: F(2, 18) = 61.1, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .76); total anxiety (SCARED-C: F(2, 38) = 39.8, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .67); GAD symptoms (SCARED-C-GAD: F(2, 38) = 37.0, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .61); depression (MFQ-C: F(2, 38) = 24.4, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .60); and quality of life (PQ-LES-Q: F(2,38) = 26.9, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .59). Post-hoc comparisons (Bonferroni) revealed significant differences between pre- and post-treatment, and between pre-treatment and follow-up only (all p’s = .000).

Significant time effects were also observed for parent-reported, secondary outcomes including: total anxiety (SCARED-P Total: F(2, 38) = 29.1, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .61); GAD symptoms (SCARED-P-GAD: F(2, 38) = 20.5, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .52); depression (MFQ-P: F(2, 38) = 20.5, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .52); difficulties with peers (SDQ-P-Peer: F(2, 38) = 31.1, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .62); overall impairment (SDQ-P-Impairment: F(2, 38) = 30.9, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .62). No time effect was found for parent-reported conduct problems (SDQ-P-Behavioral: F(2, 38) = 2.5, p = .09, ɳ 2 = .12). Again, post hoc comparisons (Bonferroni) revealed significant differences between pre- and post-treatment, and between pre-treatment and follow-up only (all p’s = .000).

Cognitive Process Measures

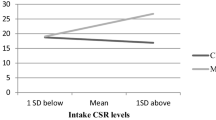

Table 4 presents results for the cognitive process measures (child-report). Significant differences, in the large range of effect sizes, were observed between the CBT and WL groups at post-treatment/WL for intolerance of uncertainty, cognitive avoidance, and negative problem orientation, but not positive beliefs about worry. For the within-subject analyses (not reported in Table 4 ) for the CBT participants, significant effects for time was observed for intolerance of uncertainty (Brief-IUS: F(2, 18) = 19.9, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .62), cognitive avoidance (Brief-CAQ: F(2, 18) = 10.9, p = .001, ɳ 2 = .41), and negative problem orientation (Brief-NPO: F(2, 18) = 19.4, p = .000, ɳ 2 = .61), but not positive beliefs about worry (Brief-WW-II: F(2, 18) = 7.1, p = .06, ɳ 2 = .27). For intolerance of uncertainty, cognitive avoidance, and negative problem orientation, post hoc comparisons (Bonferroni) revealed significant differences between pre- and post-treatment, and between pre-treatment and follow-up only (all p’s = .000).

This study was designed as a randomized controlled, pilot feasibility trial with the aim of assessing the tolerability and efficacy of an individual, child-focused, GAD-specific CBT under randomized controlled conditions. The treatment is based on (and targets) four cognitive processes from the Laval model of worry: intolerance of uncertainty, cognitive avoidance, negative problem orientation, and positive beliefs about worry. The secondary aim was to assess whether changes in these four processed occurred for the treated versus the wait-listed participants. This is only the second controlled trial of GAD-specific CBT with children and the first with adolescents. It is the third trial to report change scores on measures of the four cognitive processes from the Laval model.

The treatment was well tolerated with only two non-completers, both adolescents. One of whom removed themselves from the trial because they wanted to focus more on their symptoms of social anxiety disorder. The other was removed from the trial due to an acute onset suicidal depression relating to a family crisis, not their GAD diagnosis or treatment. Using a measure developed for this trial, the participants reported that the treatment was highly credible, and they felt able to engage well with their therapist. Including the present study, three trials have been carried out with children between seven and 12 years of age using GAD-specific CBT targeting the four cognitive processes from the Laval model, with less than 15% drop-outs, and high rates of recovery (Holmes et al. 2014 ; Payne et al. 2011 ). While further research is needed, the findings from the three trials suggest that children and adolescents are able to engage with a treatment focused largely on cognitive processes associated with worry and GAD severity.

For the primary outcome variable, measured according to intention-to-treat, a large and significant difference was observed between the CBT and wait-listed participants for GAD remission (80% vs 0%, respectively) There was a slight but non-significant increase in the proportion of CBT participants with GAD at follow-up (85%), suggesting that improvements at the diagnostic threshold level were largely maintained. These findings are similar to the intention-to-treat outcomes for GAD remission reported for post-treatment in our uncontrolled pilot of the same treatment (81%; Payne et al. 2011 ), and at the 3 month-follow up (80%; intention-to-treat) in the randomized controlled trial of a group-based treatment (Holmes et al. ( 2014 ). The present findings for GAD remission rates are also comparable to those reported in trials of adults with GAD treated with the CBT approach (Dugas and Robichaud 2007 ) on which the current treatment is based (70–88%; Ladouceur et al. 2000 , 2004 ; Dugas et al. 2003 , 2010 ).

Consistent with Payne et al. ( 2011 ) and Holmes et al. ( 2014 ), the effects of the present treatment were not limited to remission from GAD. Significant reductions were observed in the rate of comorbid disorders, as well as moderate to large effects for child- and parent-reported worry, anxiety, depression, peer problems, overall impairment, and quality of life. These gains were maintained at the 3-month follow-up for treated participants.