Distance Learning

Using technology to develop students’ critical thinking skills.

by Jessica Mansbach

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is a higher-order cognitive skill that is indispensable to students, readying them to respond to a variety of complex problems that are sure to arise in their personal and professional lives. The cognitive skills at the foundation of critical thinking are analysis, interpretation, evaluation, explanation, inference, and self-regulation.

When students think critically, they actively engage in these processes:

- Communication

- Problem-solving

To create environments that engage students in these processes, instructors need to ask questions, encourage the expression of diverse opinions, and involve students in a variety of hands-on activities that force them to be involved in their learning.

Types of Critical Thinking Skills

Instructors should select activities based on the level of thinking they want students to do and the learning objectives for the course or assignment. The chart below describes questions to ask in order to show that students can demonstrate different levels of critical thinking.

*Adapted from Brown University’s Harriet W Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning

Using Online Tools to Teach Critical Thinking Skills

Online instructors can use technology tools to create activities that help students develop both lower-level and higher-level critical thinking skills.

- Example: Use Google Doc, a collaboration feature in Canvas, and tell students to keep a journal in which they reflect on what they are learning, describe the progress they are making in the class, and cite course materials that have been most relevant to their progress. Students can share the Google Doc with you, and instructors can comment on their work.

- Example: Use the peer review assignment feature in Canvas and manually or automatically form peer review groups. These groups can be anonymous or display students’ names. Tell students to give feedback to two of their peers on the first draft of a research paper. Use the rubric feature in Canvas to create a rubric for students to use. Show students the rubric along with the assignment instructions so that students know what they will be evaluated on and how to evaluate their peers.

- Example: Use the discussions feature in Canvas and tell students to have a debate about a video they watched. Pose the debate questions in the discussion forum, and give students instructions to take a side of the debate and cite course readings to support their arguments.

- Example: Us e goreact , a tool for creating and commenting on online presentations, and tell students to design a presentation that summarizes and raises questions about a reading. Tell students to comment on the strengths and weaknesses of the author’s argument. Students can post the links to their goreact presentations in a discussion forum or an assignment using the insert link feature in Canvas.

- Example: Use goreact, a narrated Powerpoint, or a Google Doc and instruct students to tell a story that informs readers and listeners about how the course content they are learning is useful in their professional lives. In the story, tell students to offer specific examples of readings and class activities that they are finding most relevant to their professional work. Links to the goreact presentation and Google doc can be submitted via a discussion forum or an assignment in Canvas. The Powerpoint file can be submitted via a discussion or submitted in an assignment.

Pulling it All Together

Critical thinking is an invaluable skill that students need to be successful in their professional and personal lives. Instructors can be thoughtful and purposeful about creating learning objectives that promote lower and higher-level critical thinking skills, and about using technology to implement activities that support these learning objectives. Below are some additional resources about critical thinking.

Additional Resources

Carmichael, E., & Farrell, H. (2012). Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Online Resources in Developing Student Critical Thinking: Review of Literature and Case Study of a Critical Thinking Online Site. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice , 9 (1), 4.

Lai, E. R. (2011). Critical thinking: A literature review. Pearson’s Research Reports , 6 , 40-41.

Landers, H (n.d.). Using Peer Teaching In The Classroom. Retrieved electronically from https://tilt.colostate.edu/TipsAndGuides/Tip/180

Lynch, C. L., & Wolcott, S. K. (2001). Helping your students develop critical thinking skills (IDEA Paper# 37. In Manhattan, KS: The IDEA Center.

Mandernach, B. J. (2006). Thinking critically about critical thinking: Integrating online tools to Promote Critical Thinking. Insight: A collection of faculty scholarship , 1 , 41-50.

Yang, Y. T. C., & Wu, W. C. I. (2012). Digital storytelling for enhancing student academic achievement, critical thinking, and learning motivation: A year-long experimental study. Computers & Education , 59 (2), 339-352.

Insight Assessment: Measuring Thinking Worldwide

http://www.insightassessment.com/

Michigan State University’s Office of Faculty & Organizational Development, Critical Thinking: http://fod.msu.edu/oir/critical-thinking

The Critical Thinking Community

http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766

Related Posts

Up Up and Away: How Superheroes Can Save Online Discussions

Is Technology Driving Online Education Off A Cliff?

Zaption: October 2015 Online Learning Webinar

All You Need is an Oven and a Knife

9 responses to “ Using Technology To Develop Students’ Critical Thinking Skills ”

This is a great site for my students to learn how to develop critical thinking skills, especially in the STEM fields.

Great tools to help all learners at all levels… not everyone learns at the same rate.

Thanks for sharing the article. Is there any way to find tools which help in developing critical thinking skills to students?

Technology needs to be advance to develop the below factors:

Understand the links between ideas. Determine the importance and relevance of arguments and ideas. Recognize, build and appraise arguments.

Excellent share! Can I know few tools which help in developing critical thinking skills to students? Any help will be appreciated. Thanks!

- Pingback: EDTC 6431 – Module 4 – Designing Lessons That Use Critical Thinking | Mr.Reed Teaches Math

- Pingback: Homepage

- Pingback: Magacus | Pearltrees

Brilliant post. Will be sharing this on our Twitter (@refthinking). I would love to chat to you about our tool, the Thinking Kit. It has been specifically designed to help students develop critical thinking skills whilst they also learn about the topics they ‘need’ to.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Search Search Search …

- Search Search …

How to Teach Critical Thinking in the Digital Age: Effective Strategies and Techniques

In today’s rapidly evolving digital landscape, the ability to think critically has become increasingly important for individuals of all ages. As technology advances and information becomes more readily available, it is essential for teachers to adapt their methods to effectively teach critical thinking skills in the digital age.

However, the task of teaching critical thinking can prove challenging. Research from Daniel Willingham , a professor of psychology at the University of Virginia, suggests that students may struggle to apply these skills across different subjects and contexts. Nonetheless, with the right strategies and resources, educators can successfully incorporate critical thinking into their digital learning experiences , empowering their students to navigate the complex world of information.

The Importance of Critical Thinking in the Digital Age

In the digital age, we are constantly surrounded by information from various sources, making it essential for individuals to develop critical thinking skills in order to effectively evaluate the credibility and relevance of the content they consume. Furthermore, critical thinking helps people think through problems and apply the right information when developing solutions.

One of the challenges that the digital age presents is the need to differentiate factual and fake information. With the rise of social media and digital platforms, it becomes increasingly easy for false or misleading information to spread quickly. As a result, being able to discern between reliable and unreliable sources becomes an essential skill (The Tech Edvocate) .

In addition, critical thinking skills are vital in the workforce, as employees are expected to be effective problem solvers, innovative thinkers, and strong communicators. Possessing strong critical thinking skills prepares individuals to thrive in a constantly changing environment, as they can adapt to new situations, understand different perspectives, and make educated decisions.

Teaching critical thinking from a young age is crucial. Educators can use various strategies and techniques to integrate critical thinking in their lessons, such as using open-ended questions, encouraging students to evaluate sources, and promoting group work where students can learn from each other (Forbes) .

Challenges Faced in Teaching Critical Thinking Online

Teaching critical thinking skills online can be a challenging task for educators due to numerous obstacles. This section discusses the challenges of teaching critical thinking, focusing on difficulties such as information overload and technology distractions.

Information Overload

In the digital age, online students have access to an overwhelming amount of information. This can lead to difficulty in focusing on critical thinking exercises and applying those skills to new subject areas, as students struggle to navigate the vast online landscape of resources and materials.

Information overload can impede the development of effective critical thinking skills, as students find it more difficult to discern credible resources and make informed judgments. Educators must guide students in selecting appropriate resources and actively engage them in critical reflection on the information they encounter.

Technology Distractions

Another challenge in teaching critical thinking online is the presence of technology distractions. Online learners have to manage their time and attention across multiple devices and platforms, which can detract from their engagement with the learning material.

These distractions impact students’ ability to concentrate on critical thinking tasks and apply learned strategies. Additionally, constant multitasking can reduce the effectiveness of online learning, as students must split their focus between different tasks without giving their full attention to any one subject.

To mitigate technology distractions, educators can incorporate strategies such as limiting the use of technology during specific times, promoting time management skills, and offering engaging multimedia content. They can also foster a structured and supportive online learning environment, which encourages students to practice critical thinking throughout their coursework.

Techniques for Teaching Critical Thinking

Asking open-ended questions.

One effective technique for teaching critical thinking is to ask open-ended questions. These questions require more thought and exploration than simple yes or no answers, prompting students to critically analyze the issue at hand. Incorporating open-ended questions into lessons can encourage a deeper level of engagement and understanding in various subjects.

Debate and Discussion

Another valuable method for teaching critical thinking skills is to promote debate and discussion in the classroom. Through debates and discussions, students learn to listen to diverse perspectives, analyze arguments, and develop their own informed opinions. Encouraging students to express their ideas and engage with their peers in a respectful and thoughtful manner can foster a culture of critical thinking in the classroom.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

Using case studies and real-world applications can help students develop critical thinking skills by connecting the material with real-life scenarios. When students analyze case studies, they can practice solving complex problems and applying the theoretical concepts they have learned to make informed decisions. Additionally, incorporating real-world examples and applications in lessons can make the learning experience more engaging and relevant for students.

Teaching Argument Evaluation

Teaching students how to evaluate arguments is an essential aspect of fostering critical thinking skills. By teaching them to identify the strengths and weaknesses of different arguments, students can better understand the nuances of logic and reasoning. This skill is especially crucial in the digital age, where students are often exposed to various sources of information, both reliable and unreliable. By developing their argument evaluation skills, students will be better equipped to navigate and assess the credibility of information they encounter online and in everyday life.

Digital Tools for Enhancing Critical Thinking

Teaching critical thinking in the digital age can be facilitated by leveraging digital tools that promote active learning and deeper engagement. This section explores various digital tools that can enhance critical thinking skills in students, including interactive learning platforms and collaboration and communication tools.

Interactive Learning Platforms

Interactive learning platforms help students develop critical thinking skills by engaging them in challenging activities that require problem-solving, analysis, and evaluation. These platforms often incorporate game-based elements and multimedia content to stimulate interest and maintain motivation.

For example, digital storytelling can be used to promote reflection, analysis, and synthesis skills in students. By creating and sharing their stories, students can critically assess their beliefs, values, and experiences, while comparing and contrasting them with their peers’ perspectives.

Collaboration and Communication Tools

Collaborative tools, such as online discussion forums, video conferencing, and shared documents, facilitate opportunities for students to exchange ideas, brainstorm solutions, and develop arguments on various topics. These tools foster critical thinking by encouraging students to analyze and evaluate different perspectives.

For instance, implementing project-based learning activities encourages students to work together, research, analyze data, and propose solutions to real-world problems. Through this collaborative process, students refine their critical thinking skills while learning how to communicate effectively and resolve conflicts.

Another example is the use of video conferencing tools, such as Zoom or Google Meet, for online debates or panel discussions. These sessions enable students to take a deep dive into topics and engage in structured discussions that challenge their assumptions and hone their critical thinking abilities.

Overall, integrating digital tools in the teaching process can effectively promote critical thinking in students, preparing them to thrive in the digital age.

Assessing Students’ Critical Thinking Skills

Assessing students’ critical thinking skills in the digital age requires a combination of formative and summative assessment methods. This section will outline these methods and explain how they can effectively be applied in the classroom.

Formative Assessment Methods

Formative assessment methods focus on continuous feedback and monitoring of students’ progress during the learning process. These methods aim to identify areas where students may require additional support or instruction. Some formative assessment methods for critical thinking skills include:

- Think-Pair-Share: An activity in which students think about the topic or question, discuss their thoughts with a partner, and then share their ideas with the whole class. This encourages students to evaluate different perspectives and revise their thinking accordingly.

- Questioning Techniques: Employing open-ended and higher-order questioning strategies can stimulate students’ critical thinking skills, prompting them to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information. Examples of these questions can be found here .

- Peer Review: Students provide feedback on each other’s work by identifying strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement. This encourages self-reflection and fosters a collaborative learning environment.

Summative Assessment Methods

Summative assessments measure students’ critical thinking skills at the end of a unit, course, or academic year. These assessments aim to determine students’ level of competence and measure their growth over time. Some summative assessment methods for critical thinking include:

- Performance-Based Assessments: These assessments require students to apply their critical thinking skills to complete a task or solve a problem. Examples include case studies, debates, and presentations.

- Essay Examinations: Essay exams provide an opportunity for students to demonstrate their critical thinking skills through written analysis, synthesis, and evaluation of information.

- Digital Assessments: Digital assessments can be used to assess critical thinking skills by incorporating multimedia elements, interactive features, and real-time feedback. Examples can be found at ExamSoft .

By integrating both formative and summative assessment methods, educators can provide a comprehensive and accurate understanding of students’ critical thinking abilities in the digital age.

Continuous Improvement and Adaptation

In the digital age, it is crucial for educators to promote continuous improvement and adaptation in the development of critical thinking skills. As technology and information evolve rapidly, teachers must actively engage students in reflecting on their learning process and adjusting their strategies accordingly.

A useful approach to foster continuous improvement is to encourage students to set goals, reflect on their progress and actively seek feedback. This process can be facilitated through digital tools such as online discussions, project-based learning, and gamification .

Furthermore, educators can:

- Implement mini research assignments that challenge students to investigate topics further and engage in self-guided exploration.

- Introduce debates or collaborative projects that require students to apply critical reasoning and consider multiple perspectives.

- Use active learning methods such as brainstorming sessions, trainings, and case studies to encourage students to analyze and evaluate information before drawing conclusions.

Taking advantage of digital resources, teachers can create an environment where students continuously refine their critical thinking abilities and adapt to the ever-changing digital landscape. By implementing these strategies, educators will better prepare students to effectively navigate and contribute to the digital age.

In the digital age, teaching critical thinking skills requires the incorporation of effective instructional strategies and innovative technologies. Engaging learners in activities such as data collection, analysis , and group discussions promotes a dynamic learning environment where students can develop and sharpen their thinking abilities.

Teachers should consider multiple methods to facilitate the development of critical thinking. By integrating different teaching approaches , educators can create a rich and diverse educational experience for their students. This may include the use of various digital tools, such as collaborative platforms, serious games, and immersive technologies, which enhance the learning process and keep the students motivated and engaged.

Adaptability and continuous professional improvement are essential aspects for educators striving to foster critical thinking skills in a digital age. By staying up-to-date with current trends and research , as well as incorporating new instructional approaches and technologies, teachers will be better equipped for navigating and succeeding in the rapidly evolving educational landscape.

Ultimately, empowering learners with robust critical thinking skills will not only prepare them for academic success but also help them become responsible digital citizens who can make informed decisions in a highly interconnected world. By embracing the opportunities that digital technologies provide and adapting teaching practices accordingly, educators can truly make a lasting impact on their students’ lives.

You may also like

Best Approach to Problem Solving: Efficient Strategies for Success

Problem-solving is a crucial skill in all aspects of life, from personal interactions to navigating complex work situations. It is essential for […]

Critical Thinking and Logic – A Brief Walkthrough

Shelter, food, clothing, and water – these are usually considered as the most important necessities to live decently and sufficiently. In order […]

Unleash Your True Mental Power with These 10 Critical Thinking Habits

Critical thinking is an extremely useful skill no matter where you are in life. Whether you are with the top decision-making bodies […]

Critical Thinking job interview questions

In all areas of work the applicants have their own reasons for applying for a position, and the main aim of the […]

Undividing Digital Divide pp 37–48 Cite as

Today’s Two Important Skills: Digital Literacy and Critical Thinking

- Semahat Aysu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6431-9983 4

- First Online: 15 March 2023

424 Accesses

Part of the book series: SpringerBriefs in Education ((BRIEFSEDUCAT))

Digital literacy of students and their skills to use the new technologies effectively and efficiently both for their learning and their future career is the concern of our age since the fast and vast information makes people adapt themselves to continuously changing life.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Akayoğlu, S., Satar, H. M., Dikilitaş, K., Cirit, N. C., & Korkmazgil, S. (2020). Digital literacy practices of Turkish pre-service EFL teachers. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 36 (1), 85–97.

Google Scholar

Ata, R., & Yıldırım, K. (2019). Exploring Turkish pre-service teachers’ perceptions and views of digital literacy. Education Sciences, 9 (40). https://doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9010040 .

Ayyildiz, P., Yilmaz, A., & Baltaci, H. S. (2021). Exploring digital literacy levels and technology integration competence of Turkish academics. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 7 (1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.12973/ijem.7.1.15 .

Bevort, E., & Breda, I. (2008). Adolescents and the internet: Media appropriation and perspectives on education. In P. C. Rivoltella (Ed.), Digital literacy: Tools and methodology for information society (pp. 140–165). IGI Publishing.

Chapter Google Scholar

Boyd, D. (2016). What would Paulo Freire think of blackboard: Critical pedagogy in an age of online learning. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 7 (1), 165–186.

Brooks-Young, S. (2007). Digital-age literacy for teachers: Applying technology standards to everyday practice. ISTE Publications.

Cottrell, S. (2005). Critical thinking skills: Developing effective analysis and argument. Palgrave Macmillan.

Erol, S., & Aydin, E. (2021). Digital literacy status of Turkish teachers. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 13 (2), 620–633.

Facione, P. A. (1990). The California critical thinking skills test-college level. Technical report: Experimental validation and content validity. California Academic Press (ERIC Document No: TM 015818).

Goldberg, I., Kingsbury, J., Bowell, T., & Howard, D. (2015). Measuring critical thinking about deeply held beliefs: Can the California critical thinking dispositions inventory help? Inquiry: Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines, 30 (1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.5840/inquiryct20153016 .

Gökdaş, F., & Çam, A. (2022). Examination of digital literacy levels of science teachers in the distance education process. Educational Policy Analysis and Strategic Research, 17 (2), 208–224. https://doi.org/10.29329/epasr.2022.442.9 .

Halpern, D. F. (2003). Thought and knowledge: An introduction to critical thinking. Lawrence.

Hall, R., Atkins, L., & Fraser, J. (2014). Defining a self-evaluation digital literacy framework for secondary educators: The DigiLit Leicester project. Research in Learning Technology, 22 (21440) . https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v22.21440

Hobbs, R. (2010). Digital and media literacy: A plan of action. The Aspen Institute. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp content/uploads/2010/11/Digital_and_Media_Literacy.pdf

Hinrichsen, J., & Coombs, A. (2013). The five resources of critical digital literacy: A framework for curriculum integration. Research in Learning Technology, 21 (21334). https:// doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v21.21334 .

Kong, S. C. (2014). Developing information literacy and critical thinking skills through domain knowledge learning in digital classrooms: An experience of practicing flipped classroom strategy. Computers and Education, 78 , 160–173.

Article Google Scholar

Linuma, M. (2016). Learning and teaching with technology in the knowledge society: New literacy, collaboration and digital content . Springer.

List, A. (2019). Defining digital literacy development: An examination of preservice teachers’ beliefs. Computers and Education, 138, 146–158.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2014). Critical thinking: Tools for taking charge of your learning and your life. Pearson.

Porat, E., Blau, I., & Bark, A. (2018). Measuring digital literacies: Junior high-school students’ perceived competencies versus actual performance. Computers and Education, 126 , 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.06.030

Purnama, S., Maulidya, U., Machali, I., Wibowo, A., & Narmaditya, B. S. (2021). Does digital literacy influence students’ online risk? Evidence from Covid-19 (Vol. 7). Heliyon. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07406 .

Saxena, P., Gupta, S. K., Mehrotra, D., Kamthan, S., Sabir, H., Katiyar, P., & Prasad, S. V. S. (2018). Assessment of digital literacy and use of smart phones among Central Indian dental students. Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research, 8 , 40–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobcr.2017.10.001 .

Setiawardani, W., Robandi, B., & Djohar, A. (2021). Critical pedagogy in the era of the industrial revolution 4.0 to improve digital literacy students welcoming society 5.0 in Indonesia. Journal of Elementary Education, 5 (1), 107–118.

Sharkey, J., & Brandt, D. S. (2008). Integrating technology literacy and information literacy. In P. C. Rivoltella (Ed.), Digital literacy: Tools and methodology for information society (pp. 85–97). IGI Publishing.

Shopova, T. (2014). Digital literacy of students and its improvement at the university. Journal on Efficiency and Responsibility in Education and Science (ERIES Journal), 7 (2), 26–32.

Talib, S. (2018). Social media pedagogy: Applying an interdisciplinary approach to teach multimodal critical digital literacy. E-Learning and Digital Media, 15 (2), 55–66. https:// doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753018756904 .

Techataweewan, W., & Prasertsin, U. (2018). Development of digital literacy indicators for Thai undergraduate students using mixed method research. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 29 , 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2017.07.001 .

The European Parliament and the Council of the EU. (2006). Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 on key competences for lifelong learning. Official Journal of the European Union, 39 , 10–18.

UNESCO. (2008). Towards information literacy indicators. UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

Waddell, M., & Clariza, E. (2018). Critical digital pedagogy and cultural sensitivity in the library classroom: Infographics and digital storytelling. C&RL News , 228–232.

Welsh, T. S., & Wright, M. S. (2010). Information literacy in the digital age: An evidence-based approach. Chandos Publishing.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Foreign Languages, Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University, Tekirdağ, Turkey

Semahat Aysu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Semahat Aysu .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Anafatalar Kampusu Eğitim, Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Çanakkale, Türkiye

Dinçay Köksal

Eğitim Fakültesi, Mersin University, Mersin, Türkiye

Ömer Gökhan Ulum

Eğitim Fakültesi, Inonu University, Battalgazi/Malatya, Türkiye

Gülten Genç

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Aysu, S. (2023). Today’s Two Important Skills: Digital Literacy and Critical Thinking. In: Köksal, D., Ulum, Ö.G., Genç, G. (eds) Undividing Digital Divide. SpringerBriefs in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25006-4_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25006-4_4

Published : 15 March 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-25005-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-25006-4

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Chapter 4: Critical Approaches to Digital Literacy

Maha Bali and Cheryl Brown

Using the Internet is probably a daily activity for many of you, but sometimes it’s such second nature we don’t stop to think about what underlies the information we use. In this chapter, we help you think about issues of equity in the online context and explore who predominantly contributes to the information we read. We look at who is and who isn’t represented in the digital space and how everyday platforms we use are themselves skewed towards particular viewpoints and preconceptions. We provide you with some strategies and tools to be critical in understanding the platforms you use and the information you read. We also foreground some of the negative and positive aspects of social media in constraining and enabling different people’s voices.

Chapter Topics:

Introduction, thinking about context, learning to be critical.

- Voices: Who Is Represented in Digital Space and Who Isn’t?

Critical Digital Literacies: Digital Platforms

Questioning digital platforms, positioning yourself online.

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Develop a critical awareness of online contexts.

- Appraise online content.

- Develop critical questioning skills.

- Understand how some individuals or groups may be marginalized online.

- Recognize issues of access to information sources.

- Understand bias of digital platforms.

- Reflect on positionality and information privilege.

- Develop increased self-awareness of biases.

One of the most important elements of being online is the ability to be critically aware of where content comes from and who has authored it. You should be able to ask questions that will enable you to better understand context. In chapter 2, you explored the history of literacy and who traditionally has had access to the ability to read and write. Although digital technology and, specifically, the Internet have to some extent increased access to information, it is still inequitable.

There is an old saying: “Knowledge is power” (it’s so old that no one really knows who said it first). In many cultures knowledge used to be very closely guarded by elders or experts. It may have been locked away for safekeeping in libraries (such as the Library of Alexandria), where only privileged people like rulers and scribes could access it.

Technology has contributed to changes in who owns and can access information. So much so that some people believe the Internet can be credited with facilitating the coming together of our global community (in that it allows people to access information and engage with the world unhindered by distance). However, it has also contributed to the fragmentation of society as it is a place for conflict and disagreement as well as new forms of exclusion.

In the following sections, you will learn some strategies and habits to help you take a critical look at whatever you find online. However, we don’t usually verify every single piece of information we find online, so keep in mind that contextual knowledge can be the driver that motivates you to dig deeper.

Activity 4.1: Demonstrate Context

Imagine someone asks you to watch a video of US president Donald Trump standing by a wall in the White House, near the image above, telling ABC’s David Muir the following: “But when you look at this tremendous sea of love—I call it a sea of love—it’s really something special that all these people travelled here from all parts of the country, maybe the world, but all parts of the country. Hard for them to get here.”

- If your teacher showed you this video, would you believe it?

- If you received this video on social media (e.g., Facebook, WhatsApp) would you think it was real?

- What would make you doubt the authenticity of the scene?

- How would you verify its authenticity, or its lack of authenticity?

- Before reading the text below, try to verify the authenticity of the video above and keep track of the steps you took to do so.

The trick about that video is that you need to have a lot of contextual awareness to be suspicious of its authenticity: You need to recognize that the picture Trump is pointing at is of the Muslim Kaaba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, and that it is a picture of Muslims in pilgrimage. You need to connect that with a knowledge that Trump has repeatedly used negative rhetoric against Islam and Muslims, and that calling this a “Sea of Love” sounds out of sync with his usual rhetoric. Someone who does not have this contextual knowledge may not seek to verify the authenticity of the video; and someone who has this contextual knowledge, but is not habitually skeptical, or does not know how to verify audiovisual material, may simply believe it and move on.

Once you’ve finished trying to verify the authenticity of the video above, see this blog post for the full video .

One of the pitfalls in critical thinking is that sometimes we find ourselves compelled to confirm our own biases. Confirmation bias is the tendency to selectively search for and interpret information in a way that confirms your own pre-existing beliefs and ideas. In other words, you interpret new information such that it becomes compatible with your existing beliefs, and if it can’t be interpreted thus, you either choose to ignore it or call it an exception ( Aryasomayajula , 2017).

Information and knowledge have significant roles in supporting and maintaining the power structures of the modern world. We should be aware that just because information may be available and accessible, doesn’t mean it is equitable and without bias. In principle it is possible that as long as people have the resources to access the Internet, they are in a position to make their voices heard. However, in reality, a vast majority of Internet users are not really able to make themselves heard and their concerns receive little attention. Perhaps it’s more accurate to suggest that the Internet offers ordinary people the potential for power. Regardless, it is more likely used for specific purposes by those who already have power, whether symbolic, political, or social.

Activity 4.2: Equity and Bias

Watch this video by Binna Kandola on Diffusion Bias , and try a couple of these Implicit Association Tests to explore some of your own hidden biases. There may be several reasons why some online content contains misinformation:

- Ignorance; sometimes people just get things wrong or make mistakes with no malice or ulterior motive (unintentional).

- The desire to present a one-sided view based on personal beliefs (religious, political, cultural).

- The desire to promote a message that supports commercial gain (advertising, commercial bias).

- Deliberately spreading propaganda by a ruling body or organization (usually political).

- Who is represented in digital space and who isn’t?

- Who is able to participate?

- Who has access to what already exists?

- Even when multiple perspectives are side by side, which voices are considered authoritative? Who sets the standard for what is considered credible?

Trying to figure out whether a source has expertise, authority, and trustworthiness is not always easy. Mike Caulfield, in his book Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers (2017), offers a useful outline for the fact-checking process. If you’re in doubt about something you’ve found online:

- Look around to see if someone else has already fact-checked the claim or provided a synthesis of research.

- Go “upstream” to the original source: Most Web content is not original. Get to the original source to understand the trustworthiness of the information.

- Read laterally: Once you get to the source of a claim, read what other people have said about the source (publication, author, etc.). The truth is in the network.

- Circle back: If you get lost, or hit dead ends, or find yourself going down an increasingly confusing rabbit hole, back up and start over knowing what you know now. You’re likely to take a more informed path with different search terms and better decisions about what paths to follow.

Activity 4.3: How to Be Critical

What is the purpose of a website? Is it to provide information? To sell you something? To share ideas? Explore the following three websites about different aspects of digital literacy to find out who owns or produces the content:

- “ Developing Digital Literacy Skills “

- “ Critical Digital Literacy: Ten Key Readings for Our Distrustful Media Age ”

- “ Digital Literacy “

Keep in mind:

- There is often a page called About or About Us which should give you some clues about the intent of the authors and the content.

- There is often a link to a Terms and Conditions page that highlights legal aspects of content ownership and how you can use that content.

- There may be a Testimonials or Reviews page that tells you what other people think of the services or content.

- There may be a Help or Support page to enable you to get the best out of the site.

- If there is a Cart at the top of the page or a page called Prices, the site may be trying to sell you something.

- Contact pages often tell you where the producer is based by providing an address or map.

Check the authority of the author or producer:

- See if you can find out who the author is. Is it an individual or an organization?

- Is the author a recognized expert in the field? Are they affiliated or connected to any organization? If so, is the organization credible?

- Is the organization or body producing the information reputable?

- Does the author provide sources for their information? Can you go and check out these original sources?

- Can you contact the author or organization for clarification of any content?

Look at the content:

- How old is the information or content? Is the information current? Is the source (website) updated regularly? Does it need to be?

- Can you tell why the content has been published? Are the goals of the publisher clearly stated?

- Is the content factual or does it contain opinions? Is the content biased in any way?

- Does the content provide links or information to other sites? Are these authoritative? Do they present alternative views or information?

- Can you check the accuracy of the content against other sources?

- Does the site try to get you to register or sign up to receiving other content by email?

- Does the website contain advertising? (This could affect the content.)

Questions adapted from McGill (2017) and Caulfield (2017), CC-BY-SA.

Activity 4.4: Spot the Fake

Use the points in the bulleted lists in Activity 4.3: How to be Critical to see if you can complete the following activities.

- Website A: Fangtooth

- Website B: Warty Frogfish

- Website C: Tree Octopus

- How long did it take you to spot the fake? How did you know the website was fake? Did you do any checks on other sites to verify the information contained in the sites? Does the fake website have links to true information? [See the end of this activity for the answer]:

- Is the article “ Australian Birds Have Weaponized Fire ” coming from a reputable source? Can the National Post be trusted?

- Return to the National Post article and locate the link to the original scientific study. Is this a reputable journal? What can you determine about it? How about the authors of the study – do they have relevant expertise?

- Note what the paper says and covers and compare it to what the reporting source covers. Are the facts of the news story correct? Are there elements of the work the news story leaves out? Do your findings surprise you?

Answer: C) The Tree Octopus is fake

Activity adapted from Caulfield (2018), CC-BY

Asking Critical Questions

Asking questions is always a good idea. It will make you a better learner and thinker. Critical questioning means going deeper into your questioning and not just asking Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How, but instead asking more descriptive questions like “ Who benefits from this?” “ What is getting in the way of action?” “ Why has it been this way for so long?” or “How can we change this for our good?”

For more descriptive questions, see the Global Digital Citizen Foundation’s “ Ultimate Cheatsheet for Critical Thinking .”

Critical thinking isn’t only about being skeptical. In the words of the Global Digital Citizen Foundation, critical thinking is “ clear, rational, logical, and independent thinking.” It’s about “practising mindful communication and problem-solving with freedom from bias or egocentric tendency.” There are also feminist approaches to thinking critically that involve empathy and contextuality, and trying to adopt the viewpoint and frame of reference of the “other” while refraining from judging them ( Thayer-Bacon; Belenkey et al.) .

Activity 4.5: Ask Critical Questions

Here are two news articles about Digital Literacy

- “ Digital Literacy Is ‘Hot’ but Not Important “

- “ Digital Literacy ‘as Important as Reading and Writing “

Use some of the critical-questioning prompts from the Global Citizen Cheatsheet to practice critical inquiry. Ask questions of these articles and try to take your inquiry and thinking to a critical level.

Voices: Who Is Represented in Digital Space and Who Isn’t?

The Internet has provided a vehicle for people to transcend geography and political borders by interacting with information and communities from across the world. The notion of global citizenship has taken on a new meaning in educational contexts as a world view, or a set of values, that prepares students for a global or world society. It is an acknowledgement that your nation or place of residence is only part of the world and that you are part of a global society.

As a student and a global citizen it is important that you are aware of yourself and your place in the world, and of others’ places in the world, in order to begin to become aware of other people’s perspectives. A tool like Gapminder —a non-profit resource for global data and statistics—can be useful in helping you do this. Gapminder allows students and teachers to look at the world from social, economic, and environmental perspectives. Gapminder works on the premise that by having a data-based view of the world you can “fight the most devastating myths by building a fact-based world view that everyone understands.” It’s described by the Geographical Association of the UK as an “invaluable resource for making sense of contested concepts like uneven development, inequality and change.” This is particularly valuable given how commercial social media services and search engines have contributed to the spread of misinformation.

As useful as Gapminder can be as an online resource, with so much data and so many visualizations, we must also always question the sources of data, how the data sets were chosen, and the biases in the methodological approaches used in this statistical modelling style, etc. That is, no data or information is neutral and “merely a fact”; rather, data and information are “chosen facts” that can suggest a certain picture of a situation. Gapminder is one useful tool. But it should not be the only tool you use.

Activity 4.6: Evaluate Graphical Representations of the World

The intention of this activity is to give you a sense and opinion of how the world has been visually depicted and how this representation is actually an altered form of reality. Think about where you are geographically located. To what extent are, or have, common visualizations of the world (e.g., maps) shaped your beliefs about where you are from in relation to other countries?

Below are two versions of the world map, the Mercator Projection and the Gall-Peter Projection.

- What differences in perspective are shown by these two projections?

- We Have Been Misled By a Flawed World Map for 500 Years

- The Most Popular Map of the World is Highly Misleading

- Dymaxion Map

- Peirce Quincuncial

- Can you find any earlier maps of the world (e.g., from the ancient, pre-modern, or medieval periods)? How did “we” represent “ourselves” in the past? Who is responsible for this representation of “us”?

The aim of this activity is to help you evaluate the different ways in which representations of particular places and positions in the global system occur. What implications do these different ways of representing ourselves and others have for our own biases?

The Mercator map is the most popular map; it is used by Google, Wikipedia, the UN, and in many other popular depictions of the world. However, the Mercator map distorts perception of the size of continents, departing from their actual land-mass size, and rendering North America and Greenland as larger than Africa, for example. What does this do to our ability to frame and understand importance, dominance, and geopolitical relationships, specifically in light of the historical power configurations among developing countries (mostly minimized, marginalized, in the Mercator projection)?

So far in this chapter we have mainly focused on developing a critical approach to the actual information we find online. The following section introduces a new focus: on maintaining a critical perspective on the digital platforms we use every day, such as Google, Facebook, and others. It is important to recognize how digital platforms can be used in digital citizenship and activism. At the same time, it is also important to recognize that not all people around the world have equal access to these platforms, and that some people risk more than others by using these platforms.

On Bias in Google and Wikipedia

Two spaces many of us use as a first step when searching for information are Google and Wikipedia

- Go to Google Images , and look up the term “professor.” What do you notice about the search results? Do many of the results have anything in common?

- Now search for images of “Egypt” and compare what you find with what happens when you look up images of “Cairo.” What do you notice about the difference between the search results?

You may find that most results for “Egypt” show historical monuments from the time of the Pharaohs such as the pyramids and the Sphinx while many results for “Cairo” show the modern-day city with modern buildings and bridges. The former reinforces stereotypes about Egypt as a place where people live in the desert and ride camels, missing the modern-day Egypt in favour of showing famous historical images.

Bias in Search Algorithms

As you’ll read more about in Chapter 5 , search algorithms are not “neutral.” Google’s algorithm specifically depends on proxies of popularity, which means that the top search results Google returns to us are biased. They are biased in the sense that content produced by marginal people or representing marginal views may be less visible, but also that “ where content shows up in search engine results is also tied to the amount of money and optimization that is in play around that content .” Even more alarming, Zeynep Tufecki has reported that the money-making recommender algorithm of YouTube (which is owned by Google) increasingly shows users more inflammatory content because it keeps them on the site longer and therefore exposes them to more ads.

Bias in Wikipedia Content and Editing

Wikipedia is often celebrated as a democratic digital space, an encyclopedia of crowd-sourced information that can be edited by anyone in the world. The credibility of information on Wikipedia is now considered less of a problem than when the site first began, as editors frequently check up on pages and highlight areas that require additional citation, occasionally removing information not supported by credible sources. Research has shown that these frequently edited articles on Wikipedia are likely to be on par with articles on Encyclopedia Britannica in terms of accuracy and neutrality.

- Bias in Wikipedia content standards : While anyone can contribute articles and make changes to Wikipedia, they must meet the standards that have been set by the organization. While some of these standards serve to remove bias, for example by ensuring that people don’t create biographical entries for themselves or their friends, others, such as the requirement that all content be sourced from previously published material, means that pages about marginalized people for whom there isn’t much existing information on the web, make the cut less often. The requirement that all facts be cited by a “credible” and “verifiable” source also impacts the content that is available in different languages. If you are writing an article for Wikipedia in your native language and can’t find a credible reference to link to, you may have to resort to a reference for it in a different language. However, this assumes such references exist or are accessible to you.

- Differences in Wikipedia content based on language and region: One notable example is the comparison between the English and Arabic Wikipedia pages for the Arab–Israeli War in October 1973. While both articles relay mostly the same facts, the Arabic version states that Egypt won that war, while the English version lists the result as a victory for the Israeli military. The Wikipedia articles don’t balance these perspectives in both languages: each version of Wikipedia tells a different version of history. Both articles cite their sources, which shows that history is told from the writer’s perspective. There is more than one version of history, but what matters here is to clarify how the wisdom of the crowd does not ensure the different versions coexist in any one Wikipedia article.

Research studies such as Reagle and Rhue’s look at gender bias on Wikipedia versus on Britannica (2011), highlight how Wikipedia reproduces gender, racial, and other biases. There has been a lot of coverage of gender bias in Wikipedia specifically (see “Wikipedia’s Hostility To Women ,” in The Atlantic, October 21, 2015). Wikipedia has its own article on gender bias on Wikipedia , which starts by showing that as of 2011, 90% of Wikipedia’s volunteer editors were male.

Gender imbalance on Wikipedia is usually discussed in terms of the number of Wikipedia articles on female figures versus the number on male figures, as well as the length of articles on female figures or topics of female interest versus the length of those on male figures and topics. It is also important to note that within controversial topics (e.g., GamerGate ) that involve gender sensitivity, the number and strength of male editors often results in a male view being the one disseminated on Wikipedia, rather than one balanced by the inclusion of females’ views. Beyond the numbers, there has been evidence of harassment of some female editors, gender imbalance , and hostility towards women , and even though Wikipedia has had several projects to try to counter the gender imbalance and increase women’s contributions in Wikipedia, several have not fared well .

Activity 4.8: Comparing Wikipedia Pages

If you are bilingual or multilingual, open two Wikipedia pages, in two different languages, on the same historical, political, or potentially controversial topic :

- Check out the Wikipedia page for the topic in each language.

- Are the pages direct translations or do they tell different stories?

If you are not bilingual or multilingual, try using Google Translate to see if different Wikipedia translations on the same topic are identical or different (sometimes just looking at the length is an indication). Google Translate is not 100% accurate, but it is relatively good for translations between English, French, German, and Spanish (Of course, those are the dominant Western languages, but they are also the ones that are easier to translate from English versus, say, Chinese or Arabic).

While many of us enjoy free-to-use platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and many other services, we should also be aware that these are commercial providers, with profit-making intentions, which may not (and often do not) have their users’ best interests in mind and may make ethically questionable choices.

Activity 4.9: Critiquing Digital Platforms

Watch this video by Chris Gilliard on platform capitalism .

In late 2017, Chris Gilliard posted a tweet asking:

What’s the most absurd/invasive thing that tech platforms do or have done that sounds made-up but is actually true? — Should old surveillance be forgot (@hypervisible) December 29, 2017

Try answering that question yourself before reading the responses.

If you go return to Chris’s tweet, you will find several links to reports of outrageous and ethically problematic things tech platforms have done. Examples include:

- When Facebook used their algorithm to selectively manage people’s timelines and manipulate their emotions and moods .

- When an unsubscribe service sold user emails to Uber .

Can you remember an instance of a digital platform doing something invasive or unethical? Why did it matter to you? In what ways did the platform infringe upon the rights of groups or individuals? What is the worst thing that has happened directly to you or to someone you know? What, in your view, is the most dangerous thing tech platforms can do?

Activity 4.10: Investigate Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policies

Have you ever read the Terms and Conditions or Privacy Policies of platforms you use? Some of them have extremely long and virtually unreadable policies, but others are much more straightforward.

Choose two of the platforms you use often and compare their Terms of Service or Privacy Policies.

- What did you learn?

- By using the platform are you taking risks that you had not previously been aware of?

- Can you determine, for example, if you retain the copyright for material you post to one of these platforms? (Squires, D.)

Activity 4.11: Surveillance and Online Safety

Read this article on how Facebook’s mistranslation of a Palestinian’s update resulted in him being arrested .

- Why do you think this happened?

- What kind of questions does it raise about who holds power in digital platforms?

- What does this incident tell us about how digital platforms work, and about what they prioritize?

- What kinds of issues does it raise about surveillance and privacy online?

- What kind of biases does it reveal?

- How does it connect to issues of race and racial profiling online and offline? Would a similar Facebook update by a person of greater privilege have created the same kind of reaction?

Activity 4.12: Reflecting on Digital Activism

Read the following article: “ How Young Activists Deploy Digital Tools for Social Change .”

Note how Nabela Noor, a young American Muslim, started out as a YouTube personality doing non-activist videos related to makeup. However, Islamophobic discourses surrounding the election of Trump spurred her into using YouTube to respond. In this way, social media empowered Noor to have a voice in a space where young Muslim voices were largely unheard in the dominant discourse. But it is also important to note that she would not have been able to do this without her previous digital literacy and following on YouTube, and definitely not without access to YouTube (which is banned altogether in some countries) and a good Internet connection (a privilege some people in rural US and Canadian towns don’t have; the same applies to many in the global South).

Note how the other activist in the article, the young Esra’a Al-Shafei from Bahrain, talks about her pathway to online activism advocating for the rights of marginalized people in the Arab region. Note how she does not show her face on camera, for her own safety.

Many other forms of digital activism have been seen in recent years, such as the roles of Twitter and Facebook in the Arab Spring (however, the real revolution took place in the streets). But using social media for activism can be dangerous, and risky. Some political bloggers get arrested or worse.

Twitter has had a central role in campaigns such as #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo. This brief video, “ How #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo Went From Hashtags to Movements ” featuring Tarana Burke (the founder of #MeToo) and Patrisse Cullors (the founder of #BlackLivesMatter) shows how the movements started and grew, and also what both founders consider to be a new model of activism.

While these campaigns allow people to gather and work together and find supporters, they also make them more vulnerable to personal and systemic harassment, which can occasionally move outside the screen and spill into their everyday lives. Moreover, social media has been used to amplify extremist ideologies such as white supremacy, sometimes affording anonymity to people who spread hatred and violence that can lead to physical harm. This PBS podcast suggests approaches to fight back against these online aggressions.

Think of some examples of social media use for activism, and ask yourself:

- Who has the privilege and luxury to be a digital activist?

- In what ways does digital activism reproduce patterns of offline activism, especially in terms of whose voices get heard?

- How does digital activism counter patterns of offline privilege and activism, allowing new forms of activism and previously marginalized voices to be heard?

Positionality is the notion that your culture, ethnicity, gender, and many other aspects of your life (for example, education, religion, heritage, age, ability, language, etc.) influence your beliefs and values.

We felt that since this chapter reminds us to recognize the influence of the author and context on texts we encounter online, we should make our own positionality explicit: We are both scholars from the global South.

Maha is Egyptian and is an associate professor of practice at the Center for Learning and Teaching at the American University in Cairo (AUC) in Egypt. Since 2003, her work has involved supporting faculty in their teaching, including integration of technology. She also teaches undergraduate students, and recently designed and taught a course on digital literacies. Maha has a strong interest in equity and social justice issues, and her PhD from the University of Sheffield focused on the development of critical thinking for students at AUC. She identifies very much with her postcolonial hybridity, because even though she was born in Kuwait as an Egyptian to Egyptian parents, and grew up in Kuwait, she went through British and American education, lived briefly in the US and UK as an adult, and works at an American institution. All of this makes her more aware of postcolonial issues and global inequalities and inequity. Being a woman, a mom (to a girl), and a feminist also makes her very aware of gender issues. This is why you will find many examples across the text that mention postcolonial, language (especially Arabic), and gender issues with the digital world.

Cheryl is South African and an associate professor of e-learning in the School of Education Studies and Leadership at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand. Cheryl has lived and worked in South Africa, Australia, and, recently, New Zealand. A common interest of hers has centred around access to ICTs (Information and Communication Technologies) and how they facilitate or inhibit students’ participation in learning. In the past few years she has explored more closely the role technological devices (for example, cell phones and laptops) play in students’ learning in a developing context and in the development of students’ digital literacy practices. In her PhD, she explored how inequity influences students’ digital experience and therefore their digital identities. As a mother to two boys who have grown up with access to technology she feels it’s important to develop a healthy and critical awareness of both digital opportunities and challenges.

Activity 4.13: Reflect on Your Positionality

Think about who you are and about your past experiences in the world, the things you’re passionate about, and the things that trigger pain or anger.

- How might these things shape your view of the world, the ways in which you approach new information, and the ways you choose to use digital platforms?

- What might your biases be?

- What might your fears be?

- How might they influence your digital literacy?

Activity 4.14: Self-Test

What have you learned through undertaking the activities in this chapter? Has the process of working through critical approaches to digital literacy changed:

- the way you access information online?

- your social media presence?

- the way you search online?

- how you evaluate information online?

- the websites you regularly use?

- your understanding of who contributes to information on the Internet?

- how you personally interact and engage with people online?

- what information you will contribute online?

Make a list of the changes you plan to make in how you will use the Internet in the future.

Is there any personal action you can take to increase representation and equality on the Internet?

Media Attributions

- Chapter Header Image © Pixelkult

- Figure 4.1 Kaaba © Turki Al-Fassam is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 4.2 Mercator_projection © Strebe is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 4.3 Gall–Peters Projection © Strebe is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

The objective analysis and evaluation of an issue in order to form a judgement.

The tendency to selectively search for and interpret information in a way that confirms one’s own pre-existing beliefs and ideas.

Information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote a political cause or a particular point of view.

The notion that personal values, views, identity, and location in time and space influence how one understands the world.

Chapter 4: Critical Approaches to Digital Literacy Copyright © by Maha Bali and Cheryl Brown is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Top Courses

- Online Degrees

- Find your New Career

- Join for Free

Solving Problems with Creative and Critical Thinking

This course is part of People and Soft Skills for Professional and Personal Success Specialization

Taught in English

Some content may not be translated

Instructor: IBM Skills Network Team

Financial aid available

19,751 already enrolled

(221 reviews)

Recommended experience

Beginner level

No Previous Experience Required! This course can be taken by anyone regardless of professional experience.

What you'll learn

Utilize critical and creative thinking to solve issues.

Describe the 5-step process of effectively solving problems.

Analyze a problem and identify the root cause.

Explore possible solutions and employ the problem solving process.

Skills you'll gain

- Critical Thinking

- Creative Thinking

- Professional Development

- Problem Solving

- Soft skills

Details to know

Add to your LinkedIn profile

See how employees at top companies are mastering in-demand skills

Build your subject-matter expertise

- Learn new concepts from industry experts

- Gain a foundational understanding of a subject or tool

- Develop job-relevant skills with hands-on projects

- Earn a shareable career certificate

Earn a career certificate

Add this credential to your LinkedIn profile, resume, or CV

Share it on social media and in your performance review

There is 1 module in this course

In order to find a solution, one needs to be able to analyze a problem. This short course is designed to teach you how to solve and analyze problems effectively with critical and creative thinking.

Through the use of creative and critical thinking you will learn how to look at a problem and find the best solution by analyzing the different ways you can solve a problem. By taking this quick course you will gain the skills you need to find the root cause of a problem through the use of a five-step method. You will learn the process you must go through in order to find the problem, which leads to finding a solution. You will gain the necessary skills needed for critical and creative thinking which will be the foundation for successfully solving problems. This course provides fundamental skills that you will need to use in your day to day work. The course is suitable for anyone – students, career starters, experienced professionals and managers - wanting to develop problem solving skills regardless of your background. By taking this course you will be gaining some of the essential skills you need in order to be successful in your professional life. This course is part of the People and Soft Skills for Professional and Personal Success Specialization from IBM.

This module will help you to develop skills and behaviors required to solve problems and implement solutions more efficiently in an agile manner by using a systematic five-step process that involves both creative and critical thinking.

What's included

31 videos 11 readings 12 quizzes

31 videos • Total 30 minutes

- Why do you need to focus on solving problems? • 1 minute • Preview module

- The problem-solving process • 1 minute

- How can you solve problems in an agile way? • 0 minutes

- Let’s begin with the first topic • 0 minutes

- The problem-solving process-Identify • 0 minutes

- Write a problem statement • 0 minutes

- How do you find out if a problem is worth solving? • 0 minutes

- Recap • 0 minutes

- Let’s move to the second topic • 1 minute

- The problem-solving process: Analyze • 1 minute

- How do you use “The 5 Whys”? • 1 minute

- The root cause! • 0 minutes

- Many tools can help with root cause analysis • 0 minutes

- Let’s move to the third topic • 0 minutes

- The problem-solving process: Explore • 0 minutes

- Brainstorming rules • 1 minute

- Brainstorm to solve Georgia’s problem • 0 minutes

- Let’s move to the fourth topic • 0 minutes

- The problem-solving process: Select • 2 minutes

- Let’s find five solutions for one problem • 1 minute

- Use these factors to identify who should choose a solution • 0 minutes

- Use the Ease and effectiveness matrix to select the best solution • 0 minutes

- Recap • 1 minute

- Let’s move to the fifth topic • 0 minutes

- What will success look like? • 0 minutes

- How will you measure a solution’s effectiveness? • 0 minutes

- If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it • 0 minutes

- Build an implementation plan • 0 minutes

- Review the five-step problem-solving process • 2 minutes

11 readings • Total 36 minutes

- Critical and creative thinking are required to solve problems • 5 minutes

- What will you learn from the course? • 2 minutes

- Let’s help Georgia! • 5 minutes

- Is Georgia’s problem worth solving? • 4 minutes

- Recap • 2 minutes

- Brainstorm to get plenty of ideas • 5 minutes

- Let’s find five solutions for one problem • 2 minutes

- Who should chose a solution in Georgia's problem? • 2 minutes

- How will you work out the best possible solution? • 4 minutes

- Plan to implement the solution for Georgia • 3 minutes

- Congratulations and Next Steps. • 2 minutes

12 quizzes • Total 116 minutes

- Graded Quiz: Solving Problems with Critical and Creative Thinking • 20 minutes

- Practice Quiz: What do you think? • 5 minutes

- Practice Quiz: What do you think? • 3 minutes

- Practice Quiz: The “5 Whys” for Georgia • 20 minutes

- Practice Quiz: Which type of solution will work for Georgia? • 3 minutes

- Practice Quiz: Who should choose the solution in each case? • 10 minutes

- Practice Quiz: Who should choose a solution to Georgia’s problem? • 10 minutes

- Practice Quiz: Using the Ease and Effectiveness Matrix • 10 minutes

- Practice Quiz: Let’s use the Ease and effectiveness matrix for Georgia’s problem • 10 minutes

- Practice Quiz: What do you think success will look like? • 5 minutes

- Practice Quiz: What do you think? • 10 minutes

- Practice Quiz: Solving Problems with Critical and Creative Thinking • 10 minutes

Instructor ratings

We asked all learners to give feedback on our instructors based on the quality of their teaching style.

IBM is the global leader in business transformation through an open hybrid cloud platform and AI, serving clients in more than 170 countries around the world. Today 47 of the Fortune 50 Companies rely on the IBM Cloud to run their business, and IBM Watson enterprise AI is hard at work in more than 30,000 engagements. IBM is also one of the world’s most vital corporate research organizations, with 28 consecutive years of patent leadership. Above all, guided by principles for trust and transparency and support for a more inclusive society, IBM is committed to being a responsible technology innovator and a force for good in the world. For more information about IBM visit: www.ibm.com

Recommended if you're interested in Personal Development

People and Soft Skills Assessment

Developing Interpersonal Skills

People and Soft Skills for Professional and Personal Success

Specialization

Coursera Project Network

Generando un Data Lake House con Azure Synapse Analytics

Guided Project

Why people choose Coursera for their career

Learner reviews

Showing 3 of 221

221 reviews

Reviewed on Sep 29, 2022

It is not only a highly insightful course but the way it is put together makes it extremely easy to understand.

Reviewed on Oct 5, 2023

As Critical and creative thinking forms the foundation for successful problem-solving, this course equips you with the basic essential skills that are invaluable in your day-to-day work.

Reviewed on Feb 23, 2023

Great course with good instructors, thanks to Coursera for this excellent initiative.

New to Personal Development? Start here.

Open new doors with Coursera Plus

Unlimited access to 7,000+ world-class courses, hands-on projects, and job-ready certificate programs - all included in your subscription

Advance your career with an online degree

Earn a degree from world-class universities - 100% online

Join over 3,400 global companies that choose Coursera for Business

Upskill your employees to excel in the digital economy

Frequently asked questions

When will i have access to the lectures and assignments.

Access to lectures and assignments depends on your type of enrollment. If you take a course in audit mode, you will be able to see most course materials for free. To access graded assignments and to earn a Certificate, you will need to purchase the Certificate experience, during or after your audit. If you don't see the audit option:

The course may not offer an audit option. You can try a Free Trial instead, or apply for Financial Aid.

The course may offer 'Full Course, No Certificate' instead. This option lets you see all course materials, submit required assessments, and get a final grade. This also means that you will not be able to purchase a Certificate experience.

What will I get if I subscribe to this Specialization?

When you enroll in the course, you get access to all of the courses in the Specialization, and you earn a certificate when you complete the work. Your electronic Certificate will be added to your Accomplishments page - from there, you can print your Certificate or add it to your LinkedIn profile. If you only want to read and view the course content, you can audit the course for free.

What is the refund policy?

If you subscribed, you get a 7-day free trial during which you can cancel at no penalty. After that, we don’t give refunds, but you can cancel your subscription at any time. See our full refund policy Opens in a new tab .

Is financial aid available?

Yes. In select learning programs, you can apply for financial aid or a scholarship if you can’t afford the enrollment fee. If fin aid or scholarship is available for your learning program selection, you’ll find a link to apply on the description page.

More questions

Ed Tip: Problem-Solving and Critical Thinking

Students can use these graphic organizers to analyze concepts, solve problems, and think critically about the content they are exploring.

Problem-solving and critical thinking are essential life skills and, as teachers, we need to push our students beyond recall and comprehension to these types of higher-order thinking experiences. The templates in this collection are versatile tools to help prompt complex analysis and critical thinking in nearly any content area. The graphic organizers provide thought structures that can help students organize and make sense out of concepts as they process their thinking. With repeated opportunities to practice these skills in our classrooms, students can internalize these thought processes and become confident and effective critical thinkers.

At AVID Open Access, we’ve created multiple templates to help you and your students structure critical thinking thought processes. These activities may be completed digitally or printed to complete offline. A benefit of choosing to use these digitally is that multimedia (images, videos, links) can be added quite easily. The digital versions of the templates also have placeholders for text and images where appropriate. If you find a Google version that you like, click the “Use Template” button to generate your own version that can be edited and shared as needed. You may also download a PowerPoint version if you are a Microsoft user.

The templates may be completed digitally or printed to complete offline. If you choose to use these in a digital format, you will find placeholders for text and images integrated into the templates. If you find a Google version you like, click the “Use Template” button to generate your own version that can be edited and shared as needed. You may also download a PowerPoint version if you are a Microsoft user.

Templates from AVID Open Access

A/B Partner Talk

- Google Slides

- Microsoft PowerPoint

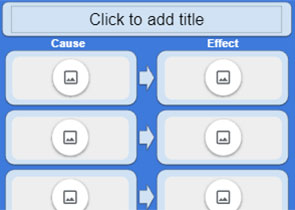

Cause and Effect #1 (Single Cause and Effect)

Cause and Effect #2 (Multiple Causes)

Cause and Effect #3 (Multiple Effects)

Cause and Effect #4 (Pictures)

Debate Preparation

- Google Docs

- Microsoft Word

Making Predictions

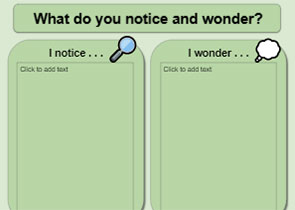

Notice and Wonder

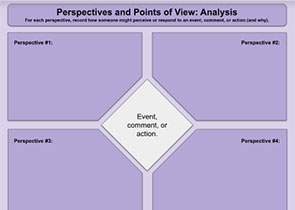

Perspectives and Points of View

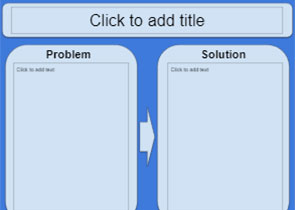

Problem Solution #1

Problem Solution #2 (Multiple Pictures)

Problem Solution #3 (Multiple Solutions)

Problem Solution #4 (Multiple Problems and Solutions)

Pro-Con Analysis

Spider Gram 1-4

Spider Gram 1-8

Online digital tools to use for problem-solving and critical thinking.

- AllSides for Schools : articles supporting multiple perspectives on an issue