- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Critical Reviews

How to Write an Article Review

Last Updated: September 8, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. There are 13 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 3,086,875 times.

An article review is both a summary and an evaluation of another writer's article. Teachers often assign article reviews to introduce students to the work of experts in the field. Experts also are often asked to review the work of other professionals. Understanding the main points and arguments of the article is essential for an accurate summation. Logical evaluation of the article's main theme, supporting arguments, and implications for further research is an important element of a review . Here are a few guidelines for writing an article review.

Education specialist Alexander Peterman recommends: "In the case of a review, your objective should be to reflect on the effectiveness of what has already been written, rather than writing to inform your audience about a subject."

Things You Should Know

- Read the article very closely, and then take time to reflect on your evaluation. Consider whether the article effectively achieves what it set out to.

- Write out a full article review by completing your intro, summary, evaluation, and conclusion. Don't forget to add a title, too!

- Proofread your review for mistakes (like grammar and usage), while also cutting down on needless information. [1] X Research source

Preparing to Write Your Review

- Article reviews present more than just an opinion. You will engage with the text to create a response to the scholarly writer's ideas. You will respond to and use ideas, theories, and research from your studies. Your critique of the article will be based on proof and your own thoughtful reasoning.

- An article review only responds to the author's research. It typically does not provide any new research. However, if you are correcting misleading or otherwise incorrect points, some new data may be presented.

- An article review both summarizes and evaluates the article.

- Summarize the article. Focus on the important points, claims, and information.

- Discuss the positive aspects of the article. Think about what the author does well, good points she makes, and insightful observations.

- Identify contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies in the text. Determine if there is enough data or research included to support the author's claims. Find any unanswered questions left in the article.

- Make note of words or issues you don't understand and questions you have.

- Look up terms or concepts you are unfamiliar with, so you can fully understand the article. Read about concepts in-depth to make sure you understand their full context.

- Pay careful attention to the meaning of the article. Make sure you fully understand the article. The only way to write a good article review is to understand the article.

- With either method, make an outline of the main points made in the article and the supporting research or arguments. It is strictly a restatement of the main points of the article and does not include your opinions.

- After putting the article in your own words, decide which parts of the article you want to discuss in your review. You can focus on the theoretical approach, the content, the presentation or interpretation of evidence, or the style. You will always discuss the main issues of the article, but you can sometimes also focus on certain aspects. This comes in handy if you want to focus the review towards the content of a course.

- Review the summary outline to eliminate unnecessary items. Erase or cross out the less important arguments or supplemental information. Your revised summary can serve as the basis for the summary you provide at the beginning of your review.

- What does the article set out to do?

- What is the theoretical framework or assumptions?

- Are the central concepts clearly defined?

- How adequate is the evidence?

- How does the article fit into the literature and field?

- Does it advance the knowledge of the subject?

- How clear is the author's writing? Don't: include superficial opinions or your personal reaction. Do: pay attention to your biases, so you can overcome them.

Writing the Article Review

- For example, in MLA , a citation may look like: Duvall, John N. "The (Super)Marketplace of Images: Television as Unmediated Mediation in DeLillo's White Noise ." Arizona Quarterly 50.3 (1994): 127-53. Print. [10] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- For example: The article, "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS," was written by Anthony Zimmerman, a Catholic priest.

- Your introduction should only be 10-25% of your review.

- End the introduction with your thesis. Your thesis should address the above issues. For example: Although the author has some good points, his article is biased and contains some misinterpretation of data from others’ analysis of the effectiveness of the condom.

- Use direct quotes from the author sparingly.

- Review the summary you have written. Read over your summary many times to ensure that your words are an accurate description of the author's article.

- Support your critique with evidence from the article or other texts.

- The summary portion is very important for your critique. You must make the author's argument clear in the summary section for your evaluation to make sense.

- Remember, this is not where you say if you liked the article or not. You are assessing the significance and relevance of the article.

- Use a topic sentence and supportive arguments for each opinion. For example, you might address a particular strength in the first sentence of the opinion section, followed by several sentences elaborating on the significance of the point.

- This should only be about 10% of your overall essay.

- For example: This critical review has evaluated the article "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS" by Anthony Zimmerman. The arguments in the article show the presence of bias, prejudice, argumentative writing without supporting details, and misinformation. These points weaken the author’s arguments and reduce his credibility.

- Make sure you have identified and discussed the 3-4 key issues in the article.

Sample Article Reviews

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/grammarpunct/proofreading/

- ↑ https://libguides.cmich.edu/writinghelp/articlereview

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548566/

- ↑ Jake Adams. Academic Tutor & Test Prep Specialist. Expert Interview. 24 July 2020.

- ↑ https://guides.library.queensu.ca/introduction-research/writing/critical

- ↑ https://www.iup.edu/writingcenter/writing-resources/organization-and-structure/creating-an-outline.html

- ↑ https://writing.umn.edu/sws/assets/pdf/quicktips/titles.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_works_cited_periodicals.html

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548565/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/593/2014/06/How_to_Summarize_a_Research_Article1.pdf

- ↑ https://www.uis.edu/learning-hub/writing-resources/handouts/learning-hub/how-to-review-a-journal-article

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

About This Article

If you have to write an article review, read through the original article closely, taking notes and highlighting important sections as you read. Next, rewrite the article in your own words, either in a long paragraph or as an outline. Open your article review by citing the article, then write an introduction which states the article’s thesis. Next, summarize the article, followed by your opinion about whether the article was clear, thorough, and useful. Finish with a paragraph that summarizes the main points of the article and your opinions. To learn more about what to include in your personal critique of the article, keep reading the article! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Prince Asiedu-Gyan

Apr 22, 2022

Did this article help you?

Sammy James

Sep 12, 2017

Juabin Matey

Aug 30, 2017

Oct 25, 2023

Vanita Meghrajani

Jul 21, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

How to Write an Article Review: Template & Examples

An article review is an academic assignment that invites you to study a piece of academic research closely. Then, you should present its summary and critically evaluate it using the knowledge you’ve gained in class and during your independent study. If you get such a task at college or university, you shouldn’t confuse it with a response paper, which is a distinct assignment with other purposes (we’ll talk about it in detail below).

Our specialists will write a custom essay specially for you!

In this article, prepared by Custom-Writing experts, you’ll find:

- the intricacies of article review writing;

- the difference between an article review and similar assignments;

- a step-by-step algorithm for review composition;

- a couple of samples to guide you throughout the writing process.

So, if you wish to study our article review example and discover helpful writing tips, keep reading.

❓ What Is an Article Review?

- ✍️ Writing Steps

📑 Article Review Format

🔗 references.

An article review is an academic paper that summarizes and critically evaluates the information presented in your selected article.

The first thing you should note when approaching the task of an article review is that not every article is suitable for this assignment. Let’s have a look at the variety of articles to understand what you can choose from.

Popular Vs. Scholarly Articles

In most cases, you’ll be required to review a scholarly, peer-reviewed article – one composed in compliance with rigorous academic standards. Yet, the Web is also full of popular articles that don’t present original scientific value and shouldn’t be selected for a review.

Just in 1 hour! We will write you a plagiarism-free paper in hardly more than 1 hour

Not sure how to distinguish these two types? Here is a comparative table to help you out.

Article Review vs. Response Paper

Now, let’s consider the difference between an article review and a response paper:

- If you’re assigned to critique a scholarly article , you will need to compose an article review .

- If your subject of analysis is a popular article , you can respond to it with a well-crafted response paper .

The reason for such distinctions is the quality and structure of these two article types. Peer-reviewed, scholarly articles have clear-cut quality criteria, allowing you to conduct and present a structured assessment of the assigned material. Popular magazines have loose or non-existent quality criteria and don’t offer an opportunity for structured evaluation. So, they are only fit for a subjective response, in which you can summarize your reactions and emotions related to the reading material.

All in all, you can structure your response assignments as outlined in the tips below.

✍️ How to Write an Article Review: Step by Step

Here is a tried and tested algorithm for article review writing from our experts. We’ll consider only the critical review variety of this academic assignment. So, let’s get down to the stages you need to cover to get a stellar review.

Receive a plagiarism-free paper tailored to your instructions. Cut 20% off your first order!

Read the Article

As with any reviews, reports, and critiques, you must first familiarize yourself with the assigned material. It’s impossible to review something you haven’t read, so set some time for close, careful reading of the article to identify:

- Its topic.

- Its type.

- The author’s main points and message.

- The arguments they use to prove their points.

- The methodology they use to approach the subject.

In terms of research type , your article will usually belong to one of three types explained below.

Summarize the Article

Now that you’ve read the text and have a general impression of the content, it’s time to summarize it for your readers. Look into the article’s text closely to determine:

- The thesis statement , or general message of the author.

- Research question, purpose, and context of research.

- Supporting points for the author’s assumptions and claims.

- Major findings and supporting evidence.

As you study the article thoroughly, make notes on the margins or write these elements out on a sheet of paper. You can also apply a different technique: read the text section by section and formulate its gist in one phrase or sentence. Once you’re done, you’ll have a summary skeleton in front of you.

Evaluate the Article

The next step of review is content evaluation. Keep in mind that various research types will require a different set of review questions. Here is a complete list of evaluation points you can include.

Get an originally-written paper according to your instructions!

Write the Text

After completing the critical review stage, it’s time to compose your article review.

The format of this assignment is standard – you will have an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. The introduction should present your article and summarize its content. The body will contain a structured review according to all four dimensions covered in the previous section. The concluding part will typically recap all the main points you’ve identified during your assessment.

It is essential to note that an article review is, first of all, an academic assignment. Therefore, it should follow all rules and conventions of academic composition, such as:

- No contractions . Don’t use short forms, such as “don’t,” “can’t,” “I’ll,” etc. in academic writing. You need to spell out all those words.

- Formal language and style . Avoid conversational phrasing and words that you would naturally use in blog posts or informal communication. For example, don’t use words like “pretty,” “kind of,” and “like.”

- Third-person narrative . Academic reviews should be written from the third-person point of view, avoiding statements like “I think,” “in my opinion,” and so on.

- No conversational forms . You shouldn’t turn to your readers directly in the text by addressing them with the pronoun “you.” It’s vital to keep the narrative neutral and impersonal.

- Proper abbreviation use . Consult the list of correct abbreviations , like “e.g.” or “i.e.,” for use in your academic writing. If you use informal abbreviations like “FYA” or “f.i.,” your professor will reduce the grade.

- Complete sentences . Make sure your sentences contain the subject and the predicate; avoid shortened or sketch-form phrases suitable for a draft only.

- No conjunctions at the beginning of a sentence . Remember the FANBOYS rule – don’t start a sentence with words like “and” or “but.” They often seem the right way to build a coherent narrative, but academic writing rules disfavor such usage.

- No abbreviations or figures at the beginning of a sentence . Never start a sentence with a number — spell it out if you need to use it anyway. Besides, sentences should never begin with abbreviations like “e.g.”

Finally, a vital rule for an article review is properly formatting the citations. We’ll discuss the correct use of citation styles in the following section.

When composing an article review, keep these points in mind:

- Start with a full reference to the reviewed article so the reader can locate it quickly.

- Ensure correct formatting of in-text references.

- Provide a complete list of used external sources on the last page of the review – your bibliographical entries .

You’ll need to understand the rules of your chosen citation style to meet all these requirements. Below, we’ll discuss the two most common referencing styles – APA and MLA.

Article Review in APA

When you need to compose an article review in the APA format , here is the general bibliographical entry format you should use for journal articles on your reference page:

- Author’s last name, First initial. Middle initial. (Year of Publication). Name of the article. Name of the Journal, volume (number), pp. #-#. https://doi.org/xx.xxx/yyyy

Horigian, V. E., Schmidt, R. D., & Feaster, D. J. (2021). Loneliness, mental health, and substance use among US young adults during COVID-19. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 53 (1), pp. 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2020.1836435

Your in-text citations should follow the author-date format like this:

- If you paraphrase the source and mention the author in the text: According to Horigian et al. (2021), young adults experienced increased levels of loneliness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic.

- If you paraphrase the source and don’t mention the author in the text: Young adults experienced increased levels of loneliness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic (Horigian et al., 2021).

- If you quote the source: As Horigian et al. (2021) point out, there were “elevated levels of loneliness, depression, anxiety, alcohol use, and drug use among young adults during COVID-19” (p. 6).

Note that your in-text citations should include “et al.,” as in the examples above, if your article has 3 or more authors. If you have one or two authors, your in-text citations would look like this:

- One author: “According to Smith (2020), depression is…” or “Depression is … (Smith, 2020).”

- Two authors: “According to Smith and Brown (2020), anxiety means…” or “Anxiety means (Smith & Brown, 2020).”

Finally, in case you have to review a book or a website article, here are the general formats for citing these source types on your APA reference list.

Article Review in MLA

If your assignment requires MLA-format referencing, here’s the general format you should use for citing journal articles on your Works Cited page:

- Author’s last name, First name. “Title of an Article.” Title of the Journal , vol. #, no. #, year, pp. #-#.

Horigian, Viviana E., et al. “Loneliness, Mental Health, and Substance Use Among US Young Adults During COVID-19.” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs , vol. 53, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1-9.

In-text citations in the MLA format follow the author-page citation format and look like this:

- According to Horigian et al., young adults experienced increased levels of loneliness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic (6).

- Young adults experienced increased levels of loneliness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic (Horigian et al. 6).

Like in APA, the abbreviation “et al.” is only needed in MLA if your article has 3 or more authors.

If you need to cite a book or a website page, here are the general MLA formats for these types of sources.

✅ Article Review Template

Here is a handy, universal article review template to help you move on with any review assignment. We’ve tried to make it as generic as possible to guide you in the academic process.

📝 Article Review Examples

The theory is good, but practice is even better. Thus, we’ve created three brief examples to show you how to write an article review. You can study the full-text samples by following the links.

📃 Men, Women, & Money

This article review examines a famous piece, “Men, Women & Money – How the Sexes Differ with Their Finances,” published by Amy Livingston in 2020. The author of this article claims that men generally spend more money than women. She makes this conclusion from a close analysis of gender-specific expenditures across five main categories: food, clothing, cars, entertainment, and general spending patterns. Livingston also looks at men’s approach to saving to argue that counter to the common perception of women’s light-hearted attitude to money, men are those who spend more on average.

📃 When and Why Nationalism Beats Globalism

This is a review of Jonathan Heidt’s 2016 article titled “When and Why Nationalism Beats Globalism,” written as an advocacy of right-wing populism rising in many Western states. The author illustrates the case with the election of Donald Trump as the US President and the rise of right-wing rhetoric in many Western countries. These examples show how nationalist sentiment represents a reaction to global immigration and a failure of globalization.

📃 Sleep Deprivation

This is a review of the American Heart Association’s article titled “The Dangers of Sleep Deprivation.” It discusses how the national organization concerned with the American population’s cardiovascular health links the lack of high-quality sleep to far-reaching health consequences. The organization’s experts reveal how a consistent lack of sleep leads to Alzheimer’s disease development, obesity, type 2 diabetes, etc.

✏️ Article Review FAQ

A high-quality article review should summarize the assigned article’s content and offer data-backed reactions and evaluations of its quality in terms of the article’s purpose, methodology, and data used to argue the main points. It should be detailed, comprehensive, objective, and evidence-based.

The purpose of writing a review is to allow students to reflect on research quality and showcase their critical thinking and evaluation skills. Students should exhibit their mastery of close reading of research publications and their unbiased assessment.

The content of your article review will be the same in any format, with the only difference in the assignment’s formatting before submission. Ensure you have a separate title page made according to APA standards and cite sources using the parenthetical author-date referencing format.

You need to take a closer look at various dimensions of an assigned article to compose a valuable review. Study the author’s object of analysis, the purpose of their research, the chosen method, data, and findings. Evaluate all these dimensions critically to see whether the author has achieved the initial goals. Finally, offer improvement recommendations to add a critique aspect to your paper.

- Scientific Article Review: Duke University

- Book and Article Reviews: William & Mary, Writing Resources Center

- Sample Format for Reviewing a Journal Article: Boonshoft School of Medicine

- Research Paper Review – Structure and Format Guidelines: New Jersey Institute of Technology

- Article Review: University of Waterloo

- Article Review: University of South Australia

- How to Write a Journal Article Review: University of Newcastle Library Guides

- Writing Help: The Article Review: Central Michigan University Libraries

- Write a Critical Review of a Scientific Journal Article: McLaughlin Library

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Short essays answer a specific question on the subject. They usually are anywhere between 250 words and 750 words long. A paper with less than 250 words isn’t considered a finished text, so it doesn’t fall under the category of a short essay. Essays of such format are required for...

High school and college students often face challenges when crafting a compare-and-contrast essay. A well-written paper of this kind needs to be structured appropriately to earn you good grades. Knowing how to organize your ideas allows you to present your ideas in a coherent and logical manner This article by...

If you’re a student, you’ve heard about a formal essay: a factual, research-based paper written in 3rd person. Most students have to produce dozens of them during their educational career. Writing a formal essay may not be the easiest task. But fear not: our custom-writing team is here to guide...

Narrative essays are unlike anything you wrote throughout your academic career. Instead of writing a formal paper, you need to tell a story. Familiar elements such as evidence and arguments are replaced with exposition and character development. The importance of writing an outline for an essay like this is hard...

A précis is a brief synopsis of a written piece. It is used to summarize and analyze a text’s main points. If you need to write a précis for a research paper or the AP Lang exam, you’ve come to the right place. In this comprehensive guide by Custom-Writing.org, you’ll...

A synthesis essay requires you to work with multiple sources. You combine the information gathered from them to present a well-rounded argument on a topic. Are you looking for the ultimate guide on synthesis essay writing? You’ve come to the right place! In this guide by our custom writing team,...

Do you know how to make your essay stand out? One of the easiest ways is to start your introduction with a catchy hook. A hook is a phrase or a sentence that helps to grab the reader’s attention. After reading this article by Custom-Writing.org, you will be able to...

Critical thinking is the process of evaluating and analyzing information. People who use it in everyday life are open to different opinions. They rely on reason and logic when making conclusions about certain issues. A critical thinking essay shows how your thoughts change as you research your topic. This type...

Process analysis is an explanation of how something works or happens. Want to know more? Read the following article prepared by our custom writing specialists and learn about: process analysis and its typesa process analysis outline tipsfree examples and other tips that might be helpful for your college assignment So,...

A visual analysis essay is an academic paper type that history and art students often deal with. It consists of a detailed description of an image or object. It can also include an interpretation or an argument that is supported by visual evidence. In this article, our custom writing experts...

Want to know how to write a reflection paper for college or school? To do that, you need to connect your personal experiences with theoretical knowledge. Usually, students are asked to reflect on a documentary, a text, or their experience. Sometimes one needs to write a paper about a lesson...

A character analysis is an examination of the personalities and actions of protagonists and antagonists that make up a story. It discusses their role in the story, evaluates their traits, and looks at their conflicts and experiences. You might need to write this assignment in school or college. Like any...

Article Review

Article Review Writing: A Complete Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

People also read

Learn How to Write an Editorial on Any Topic

Best Tips on How to Avoid Plagiarism

How to Write a Movie Review - Guide & Examples

A Complete Guide on How to Write a Summary for Students

Write Opinion Essay Like a Pro: A Detailed Guide

Evaluation Essay - Definition, Examples, and Writing Tips

How to Write a Thematic Statement - Tips & Examples

How to Write a Bio - Quick Tips, Structure & Examples

How to Write a Synopsis – A Simple Format & Guide

How to Write a Comparative Essay – A Complete Guide

Visual Analysis Essay - A Writing Guide with Format & Sample

List of Common Social Issues Around the World

Writing Character Analysis - Outline, Steps, and Examples

11 Common Types of Plagiarism Explained Through Examples

A Detailed Guide on How to Write a Poem Step by Step

Detailed Guide on Appendix Writing: With Tips and Examples

Struggling to write a review that people actually want to read? Feeling lost in the details and wondering how to make your analysis stand out?

You're not alone!

Many writers find it tough to navigate the world of article reviews, not sure where to start or how to make their reviews really grab attention.

No worries!

In this blog, we're going to guide you through the process of writing an article review that stands out. We'll also share tips, and examples to make this process easier for you.

Let’s get started.

- 1. What is an Article Review?

- 2. Types of Article Reviews

- 3. Article Review Format

- 4. How to Write an Article Review? 10 Easy Steps

- 5. Article Review Outline

- 6. Article Review Examples

- 7. Tips for Writing an Effective Article Review

What is an Article Review?

An article review is a critical evaluation and analysis of a piece of writing, typically an academic or journalistic article.

It goes beyond summarizing the content; it involves an in-depth examination of the author's ideas, arguments, and methodologies.

The goal is to provide a well-rounded understanding of the article's strengths, weaknesses, and overall contribution to the field.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Types of Article Reviews

Article reviews come in various forms, each serving a distinct purpose in the realm of academic or professional discourse. Understanding these types is crucial for tailoring your approach.

Here are some common types of article reviews:

Journal Article Review

A journal article review involves a thorough evaluation of scholarly articles published in academic journals.

It requires summarizing the article's key points, methodology, and findings, emphasizing its contributions to the academic field.

Take a look at the following example to help you understand better.

Example of Journal Article Review

Research Article Review

A research article review focuses on scrutinizing articles with a primary emphasis on research.

This type of review involves evaluating the research design, methodology, results, and their broader implications.

Discussions on the interpretation of results, limitations, and the article's overall contributions are key.

Here is a sample for you to get an idea.

Example of Research Article Review

Science Article Review

A science article review specifically addresses articles within scientific disciplines. It includes summarizing scientific concepts, hypotheses, and experimental methods.

The type of review assesses the reliability of the experimental design, and evaluates the author's interpretation of findings.

Take a look at the following example.

Example of Science Article Review

Critical Review

A critical review involves a balanced critique of a given article. It encompasses providing a comprehensive summary, highlighting key points, and engaging in a critical analysis of strengths and weaknesses.

To get a clearer idea of a critical review, take a look at this example.

Critical Review Example

Article Review Format

When crafting an article review in either APA or MLA format, it's crucial to adhere to the specific guidelines for citing sources.

Below are the bibliographical entries for different types of sources in both APA and MLA styles:

How to Write an Article Review? 10 Easy Steps

Writing an effective article review involves a systematic approach. Follow this step-by-step process to ensure a comprehensive and well-structured analysis.

Step 1: Understand the Assignment

Before diving into the review, carefully read and understand the assignment guidelines.

Pay attention to specific requirements, such as word count, formatting style (APA, MLA), and the aspects your instructor wants you to focus on.

Step 2: Read the Article Thoroughly

Begin by thoroughly reading the article. Take notes on key points, arguments, and evidence presented by the author.

Understand the author's main thesis and the context in which the article was written.

Step 3: Create a Summary

Summarize the main points of the article. Highlight the author's key arguments and findings.

While writing the summary ensure that you capture the essential elements of the article to provide context for your analysis.

Step 4: Identify the Author's Thesis

In this step, pinpoint the author's main thesis or central argument. Understand the purpose of the article and how the author supports their position.

This will serve as a foundation for your critique.

Step 5: Evaluate the Author's Evidence and Methodology

Examine the evidence provided by the author to support their thesis. Assess the reliability and validity of the methodology used.

Consider the sources, data collection methods, and any potential biases.

Step 6: Analyze the Author's Writing Style

Evaluate the author's writing style and how effectively they communicate their ideas.

Consider the clarity of the language, the organization of the content, and the overall persuasiveness of the article.

Step 7: Consider the Article's Contribution

Reflect on the article's contribution to its field of study. Analyze how it fits into the existing literature, its significance, and any potential implications for future research or applications.

Step 8: Write the Introduction

Craft an introduction that includes the article's title, author, publication date, and a brief overview.

State the purpose of your review and your thesis—the main point you'll be analyzing in your review.

Step 9: Develop the Body of the Review

Organize your review by addressing specific aspects such as the author's thesis, methodology, writing style, and the article's contribution.

Use clear paragraphs to structure your analysis logically.

Step 10: Conclude with a Summary and Evaluation

Summarize your main points and restate your overall assessment of the article.

Offer insights into its strengths and weaknesses, and conclude with any recommendations for improvement or suggestions for further research.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Article Review Outline

Creating a well-organized outline is an essential part of writing a coherent and insightful article review.

This outline given below will guide you through the key sections of your review, ensuring that your analysis is comprehensive and logically structured.

Refer to the following template to understand outlining the article review in detail.

Article Review Format Template

Article Review Examples

Examining article review examples can provide valuable insights into the structure, tone, and depth of analysis expected.

Below are sample article reviews, each illustrating a different approach and focus.

Example of Article Review

Sample of article review assignment pdf

Tips for Writing an Effective Article Review

Crafting an effective article review involves a combination of critical analysis, clarity, and structure.

Here are some valuable tips to guide you through the process:

- Start with a Clear Introduction

Kick off your article review by introducing the article's main points and mentioning the publication date, which you can find on the re-title page. Outline the topics you'll cover in your review.

- Concise Summary with Unanswered Questions

Provide a short summary of the article, emphasizing its main ideas. Highlight any lingering questions, known as "unanswered questions," that the article may have triggered. Use a basic article review template to help structure your thoughts.

- Illustrate with Examples

Use examples from the article to illustrate your points. If there are tables or figures in the article, discuss them to make your review more concrete and easily understandable.

- Organize Clearly with a Summary Section

Keep your review straightforward and well-organized. Begin with the start of the article, express your thoughts on what you liked or didn't like, and conclude with a summary section. This follows a basic plan for clarity.

- Constructive Criticism

When providing criticism, be constructive. If there are elements you don't understand, frame them as "unanswered questions." This approach shows engagement and curiosity.

- Smoothly Connect Your Ideas

Ensure your thoughts flow naturally throughout your review. Use simple words and sentences. If you have questions about the article, let them guide your review organically.

- Revise and Check for Clarity

Before finishing, go through your review. Correct any mistakes and ensure it sounds clear. Check if you followed your plan, used simple words, and incorporated the keywords effectively. This makes your review better and more accessible for others.

In conclusion , writing an effective article review involves a thoughtful balance of summarizing key points, and addressing unanswered questions.

By following a simple and structured approach, you can create a review that not only analyzes the content but also adds value to the reader's understanding.

Remember to organize your thoughts logically, use clear language, and provide examples from the article to support your points.

Ready to elevate your article reviewing skills? Explore the valuable resources and expert assistance at MyPerfectWords.com.

Our team of experienced writers is here to help you with article reviews and other school tasks.

So why wait? Get our essay writing service today!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Dr. Barbara is a highly experienced writer and author who holds a Ph.D. degree in public health from an Ivy League school. She has worked in the medical field for many years, conducting extensive research on various health topics. Her writing has been featured in several top-tier publications.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

The Tech Edvocate

- Advertisement

- Home Page Five (No Sidebar)

- Home Page Four

- Home Page Three

- Home Page Two

- Icons [No Sidebar]

- Left Sidbear Page

- Lynch Educational Consulting

- My Speaking Page

- Newsletter Sign Up Confirmation

- Newsletter Unsubscription

- Page Example

- Privacy Policy

- Protected Content

- Request a Product Review

- Shortcodes Examples

- Terms and Conditions

- The Edvocate

- The Tech Edvocate Product Guide

- Write For Us

- Dr. Lynch’s Personal Website

- The Edvocate Podcast

- Assistive Technology

- Child Development Tech

- Early Childhood & K-12 EdTech

- EdTech Futures

- EdTech News

- EdTech Policy & Reform

- EdTech Startups & Businesses

- Higher Education EdTech

- Online Learning & eLearning

- Parent & Family Tech

- Personalized Learning

- Product Reviews

- Tech Edvocate Awards

- School Ratings

3 Ways to Clean a Painting

How to date a mormon guy: 6 steps, how to know if someone blocked you on pinterest: 5 steps, 3 ways to make a bathroom in minecraft, 3 ways to use dmso, 6 ways to update minecraft, how to drive a car if you’re autistic, how to use kik, how to feed a snake frozen food, 3 effective ways to study for the toefl exam, how to write an article review (with sample reviews) .

An article review is a critical evaluation of a scholarly or scientific piece, which aims to summarize its main ideas, assess its contributions, and provide constructive feedback. A well-written review not only benefits the author of the article under scrutiny but also serves as a valuable resource for fellow researchers and scholars. Follow these steps to create an effective and informative article review:

1. Understand the purpose: Before diving into the article, it is important to understand the intent of writing a review. This helps in focusing your thoughts, directing your analysis, and ensuring your review adds value to the academic community.

2. Read the article thoroughly: Carefully read the article multiple times to get a complete understanding of its content, arguments, and conclusions. As you read, take notes on key points, supporting evidence, and any areas that require further exploration or clarification.

3. Summarize the main ideas: In your review’s introduction, briefly outline the primary themes and arguments presented by the author(s). Keep it concise but sufficiently informative so that readers can quickly grasp the essence of the article.

4. Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses: In subsequent paragraphs, assess the strengths and limitations of the article based on factors such as methodology, quality of evidence presented, coherence of arguments, and alignment with existing literature in the field. Be fair and objective while providing your critique.

5. Discuss any implications: Deliberate on how this particular piece contributes to or challenges existing knowledge in its discipline. You may also discuss potential improvements for future research or explore real-world applications stemming from this study.

6. Provide recommendations: Finally, offer suggestions for both the author(s) and readers regarding how they can further build on this work or apply its findings in practice.

7. Proofread and revise: Once your initial draft is complete, go through it carefully for clarity, accuracy, and coherence. Revise as necessary, ensuring your review is both informative and engaging for readers.

Sample Review:

A Critical Review of “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health”

Introduction:

“The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health” is a timely article which investigates the relationship between social media usage and psychological well-being. The authors present compelling evidence to support their argument that excessive use of social media can result in decreased self-esteem, increased anxiety, and a negative impact on interpersonal relationships.

Strengths and weaknesses:

One of the strengths of this article lies in its well-structured methodology utilizing a variety of sources, including quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews. This approach provides a comprehensive view of the topic, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the effects of social media on mental health. However, it would have been beneficial if the authors included a larger sample size to increase the reliability of their conclusions. Additionally, exploring how different platforms may influence mental health differently could have added depth to the analysis.

Implications:

The findings in this article contribute significantly to ongoing debates surrounding the psychological implications of social media use. It highlights the potential dangers that excessive engagement with online platforms may pose to one’s mental well-being and encourages further research into interventions that could mitigate these risks. The study also offers an opportunity for educators and policy-makers to take note and develop strategies to foster healthier online behavior.

Recommendations:

Future researchers should consider investigating how specific social media platforms impact mental health outcomes, as this could lead to more targeted interventions. For practitioners, implementing educational programs aimed at promoting healthy online habits may be beneficial in mitigating the potential negative consequences associated with excessive social media use.

Conclusion:

Overall, “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health” is an important and informative piece that raises awareness about a pressing issue in today’s digital age. Given its minor limitations, it provides valuable

3 Ways to Make a Mini Greenhouse ...

3 ways to teach yourself to play ....

Matthew Lynch

Related articles more from author.

How to Get a Building Permit in Florida

How to Grill Filet Mignon: 14 Steps

How to Sign a Painting: 10 Steps

9 Ways to Write a Sitcom

How to Bathe a Turtle

15 Ways to Care for Cattle

How to Write an Article Review: Tips and Examples

Did you know that article reviews are not just academic exercises but also a valuable skill in today's information age? In a world inundated with content, being able to dissect and evaluate articles critically can help you separate the wheat from the chaff. Whether you're a student aiming to excel in your coursework or a professional looking to stay well-informed, mastering the art of writing article reviews is an invaluable skill.

Short Description

In this article, our research paper writing service experts will start by unraveling the concept of article reviews and discussing the various types. You'll also gain insights into the art of formatting your review effectively. To ensure you're well-prepared, we'll take you through the pre-writing process, offering tips on setting the stage for your review. But it doesn't stop there. You'll find a practical example of an article review to help you grasp the concepts in action. To complete your journey, we'll guide you through the post-writing process, equipping you with essential proofreading techniques to ensure your work shines with clarity and precision!

What Is an Article Review: Grasping the Concept

A review article is a type of professional paper writing that demands a high level of in-depth analysis and a well-structured presentation of arguments. It is a critical, constructive evaluation of literature in a particular field through summary, classification, analysis, and comparison.

If you write a scientific review, you have to use database searches to portray the research. Your primary goal is to summarize everything and present a clear understanding of the topic you've been working on.

Writing Involves:

- Summarization, classification, analysis, critiques, and comparison.

- The analysis, evaluation, and comparison require the use of theories, ideas, and research relevant to the subject area of the article.

- It is also worth nothing if a review does not introduce new information, but instead presents a response to another writer's work.

- Check out other samples to gain a better understanding of how to review the article.

Types of Review

When it comes to article reviews, there's more than one way to approach the task. Understanding the various types of reviews is like having a versatile toolkit at your disposal. In this section, we'll walk you through the different dimensions of review types, each offering a unique perspective and purpose. Whether you're dissecting a scholarly article, critiquing a piece of literature, or evaluating a product, you'll discover the diverse landscape of article reviews and how to navigate it effectively.

.webp)

Journal Article Review

Just like other types of reviews, a journal article review assesses the merits and shortcomings of a published work. To illustrate, consider a review of an academic paper on climate change, where the writer meticulously analyzes and interprets the article's significance within the context of environmental science.

Research Article Review

Distinguished by its focus on research methodologies, a research article review scrutinizes the techniques used in a study and evaluates them in light of the subsequent analysis and critique. For instance, when reviewing a research article on the effects of a new drug, the reviewer would delve into the methods employed to gather data and assess their reliability.

Science Article Review

In the realm of scientific literature, a science article review encompasses a wide array of subjects. Scientific publications often provide extensive background information, which can be instrumental in conducting a comprehensive analysis. For example, when reviewing an article about the latest breakthroughs in genetics, the reviewer may draw upon the background knowledge provided to facilitate a more in-depth evaluation of the publication.

Need a Hand From Professionals?

Address to Our Writers and Get Assistance in Any Questions!

Formatting an Article Review

The format of the article should always adhere to the citation style required by your professor. If you're not sure, seek clarification on the preferred format and ask him to clarify several other pointers to complete the formatting of an article review adequately.

How Many Publications Should You Review?

- In what format should you cite your articles (MLA, APA, ASA, Chicago, etc.)?

- What length should your review be?

- Should you include a summary, critique, or personal opinion in your assignment?

- Do you need to call attention to a theme or central idea within the articles?

- Does your instructor require background information?

When you know the answers to these questions, you may start writing your assignment. Below are examples of MLA and APA formats, as those are the two most common citation styles.

Using the APA Format

Articles appear most commonly in academic journals, newspapers, and websites. If you write an article review in the APA format, you will need to write bibliographical entries for the sources you use:

- Web : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Year, Month, Date of Publication). Title. Retrieved from {link}

- Journal : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Publication Year). Publication Title. Periodical Title, Volume(Issue), pp.-pp.

- Newspaper : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Year, Month, Date of Publication). Publication Title. Magazine Title, pp. xx-xx.

Using MLA Format

- Web : Last, First Middle Initial. “Publication Title.” Website Title. Website Publisher, Date Month Year Published. Web. Date Month Year Accessed.

- Newspaper : Last, First M. “Publication Title.” Newspaper Title [City] Date, Month, Year Published: Page(s). Print.

- Journal : Last, First M. “Publication Title.” Journal Title Series Volume. Issue (Year Published): Page(s). Database Name. Web. Date Month Year Accessed.

Enhance your writing effortlessly with EssayPro.com , where you can order an article review or any other writing task. Our team of expert writers specializes in various fields, ensuring your work is not just summarized, but deeply analyzed and professionally presented. Ideal for students and professionals alike, EssayPro offers top-notch writing assistance tailored to your needs. Elevate your writing today with our skilled team at your article review writing service !

.jpg)

The Pre-Writing Process

Facing this task for the first time can really get confusing and can leave you unsure of where to begin. To create a top-notch article review, start with a few preparatory steps. Here are the two main stages from our dissertation services to get you started:

Step 1: Define the right organization for your review. Knowing the future setup of your paper will help you define how you should read the article. Here are the steps to follow:

- Summarize the article — seek out the main points, ideas, claims, and general information presented in the article.

- Define the positive points — identify the strong aspects, ideas, and insightful observations the author has made.

- Find the gaps —- determine whether or not the author has any contradictions, gaps, or inconsistencies in the article and evaluate whether or not he or she used a sufficient amount of arguments and information to support his or her ideas.

- Identify unanswered questions — finally, identify if there are any questions left unanswered after reading the piece.

Step 2: Move on and review the article. Here is a small and simple guide to help you do it right:

- Start off by looking at and assessing the title of the piece, its abstract, introductory part, headings and subheadings, opening sentences in its paragraphs, and its conclusion.

- First, read only the beginning and the ending of the piece (introduction and conclusion). These are the parts where authors include all of their key arguments and points. Therefore, if you start with reading these parts, it will give you a good sense of the author's main points.

- Finally, read the article fully.

These three steps make up most of the prewriting process. After you are done with them, you can move on to writing your own review—and we are going to guide you through the writing process as well.

Outline and Template

As you progress with reading your article, organize your thoughts into coherent sections in an outline. As you read, jot down important facts, contributions, or contradictions. Identify the shortcomings and strengths of your publication. Begin to map your outline accordingly.

If your professor does not want a summary section or a personal critique section, then you must alleviate those parts from your writing. Much like other assignments, an article review must contain an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Thus, you might consider dividing your outline according to these sections as well as subheadings within the body. If you find yourself troubled with the pre-writing and the brainstorming process for this assignment, seek out a sample outline.

Your custom essay must contain these constituent parts:

- Pre-Title Page - Before diving into your review, start with essential details: article type, publication title, and author names with affiliations (position, department, institution, location, and email). Include corresponding author info if needed.

- Running Head - In APA format, use a concise title (under 40 characters) to ensure consistent formatting.

- Summary Page - Optional but useful. Summarize the article in 800 words, covering background, purpose, results, and methodology, avoiding verbatim text or references.

- Title Page - Include the full title, a 250-word abstract, and 4-6 keywords for discoverability.

- Introduction - Set the stage with an engaging overview of the article.

- Body - Organize your analysis with headings and subheadings.

- Works Cited/References - Properly cite all sources used in your review.

- Optional Suggested Reading Page - If permitted, suggest further readings for in-depth exploration.

- Tables and Figure Legends (if instructed by the professor) - Include visuals when requested by your professor for clarity.

Example of an Article Review

You might wonder why we've dedicated a section of this article to discuss an article review sample. Not everyone may realize it, but examining multiple well-constructed examples of review articles is a crucial step in the writing process. In the following section, our essay writing service experts will explain why.

Looking through relevant article review examples can be beneficial for you in the following ways:

- To get you introduced to the key works of experts in your field.

- To help you identify the key people engaged in a particular field of science.

- To help you define what significant discoveries and advances were made in your field.

- To help you unveil the major gaps within the existing knowledge of your field—which contributes to finding fresh solutions.

- To help you find solid references and arguments for your own review.

- To help you generate some ideas about any further field of research.

- To help you gain a better understanding of the area and become an expert in this specific field.

- To get a clear idea of how to write a good review.

View Our Writer’s Sample Before Crafting Your Own!

Why Have There Been No Great Female Artists?

Steps for Writing an Article Review

Here is a guide with critique paper format on how to write a review paper:

.webp)

Step 1: Write the Title

First of all, you need to write a title that reflects the main focus of your work. Respectively, the title can be either interrogative, descriptive, or declarative.

Step 2: Cite the Article

Next, create a proper citation for the reviewed article and input it following the title. At this step, the most important thing to keep in mind is the style of citation specified by your instructor in the requirements for the paper. For example, an article citation in the MLA style should look as follows:

Author's last and first name. "The title of the article." Journal's title and issue(publication date): page(s). Print

Abraham John. "The World of Dreams." Virginia Quarterly 60.2(1991): 125-67. Print.

Step 3: Article Identification

After your citation, you need to include the identification of your reviewed article:

- Title of the article

- Title of the journal

- Year of publication

All of this information should be included in the first paragraph of your paper.

The report "Poverty increases school drop-outs" was written by Brian Faith – a Health officer – in 2000.

Step 4: Introduction

Your organization in an assignment like this is of the utmost importance. Before embarking on your writing process, you should outline your assignment or use an article review template to organize your thoughts coherently.

- If you are wondering how to start an article review, begin with an introduction that mentions the article and your thesis for the review.

- Follow up with a summary of the main points of the article.

- Highlight the positive aspects and facts presented in the publication.

- Critique the publication by identifying gaps, contradictions, disparities in the text, and unanswered questions.

Step 5: Summarize the Article

Make a summary of the article by revisiting what the author has written about. Note any relevant facts and findings from the article. Include the author's conclusions in this section.

Step 6: Critique It

Present the strengths and weaknesses you have found in the publication. Highlight the knowledge that the author has contributed to the field. Also, write about any gaps and/or contradictions you have found in the article. Take a standpoint of either supporting or not supporting the author's assertions, but back up your arguments with facts and relevant theories that are pertinent to that area of knowledge. Rubrics and templates can also be used to evaluate and grade the person who wrote the article.

Step 7: Craft a Conclusion

In this section, revisit the critical points of your piece, your findings in the article, and your critique. Also, write about the accuracy, validity, and relevance of the results of the article review. Present a way forward for future research in the field of study. Before submitting your article, keep these pointers in mind:

- As you read the article, highlight the key points. This will help you pinpoint the article's main argument and the evidence that they used to support that argument.

- While you write your review, use evidence from your sources to make a point. This is best done using direct quotations.

- Select quotes and supporting evidence adequately and use direct quotations sparingly. Take time to analyze the article adequately.

- Every time you reference a publication or use a direct quotation, use a parenthetical citation to avoid accidentally plagiarizing your article.

- Re-read your piece a day after you finish writing it. This will help you to spot grammar mistakes and to notice any flaws in your organization.

- Use a spell-checker and get a second opinion on your paper.

The Post-Writing Process: Proofread Your Work

Finally, when all of the parts of your article review are set and ready, you have one last thing to take care of — proofreading. Although students often neglect this step, proofreading is a vital part of the writing process and will help you polish your paper to ensure that there are no mistakes or inconsistencies.

To proofread your paper properly, start by reading it fully and checking the following points:

- Punctuation

- Other mistakes

Afterward, take a moment to check for any unnecessary information in your paper and, if found, consider removing it to streamline your content. Finally, double-check that you've covered at least 3-4 key points in your discussion.

And remember, if you ever need help with proofreading, rewriting your essay, or even want to buy essay , our friendly team is always here to assist you.

Need an Article REVIEW WRITTEN?

Just send us the requirements to your paper and watch one of our writers crafting an original paper for you.

What Is A Review Article?

How to write an article review, how to write an article review in apa format, related articles.

.webp)

Get Started

Take the first step and invest in your future.

Online Programs

Offering flexibility & convenience in 51 online degrees & programs.

Prairie Stars

Featuring 15 intercollegiate NCAA Div II athletic teams.

Find your Fit

UIS has over 85 student and 10 greek life organizations, and many volunteer opportunities.

Arts & Culture

Celebrating the arts to create rich cultural experiences on campus.

Give Like a Star

Your generosity helps fuel fundraising for scholarships, programs and new initiatives.

Bragging Rights

UIS was listed No. 1 in Illinois and No. 3 in the Midwest in 2023 rankings.

- Quick links Applicants & Students Important Apps & Links Alumni Faculty and Staff Community Admissions How to Apply Cost & Aid Tuition Calculator Registrar Orientation Visit Campus Academics Register for Class Programs of Study Online Degrees & Programs Graduate Education International Student Services Study Away Student Support Bookstore UIS Life Dining Diversity & Inclusion Get Involved Health & Wellness COVID-19 United in Safety Residence Life Student Life Programs UIS Connection Important Apps UIS Mobile App Advise U Canvas myUIS i-card Balance Pay My Bill - UIS Bursar Self-Service Email Resources Bookstore Box Information Technology Services Library Orbit Policies Webtools Get Connected Area Information Calendar Campus Recreation Departments & Programs (A-Z) Parking UIS Newsroom Connect & Get Involved Update your Info Alumni Events Alumni Networks & Groups Volunteer Opportunities Alumni Board News & Publications Featured Alumni Alumni News UIS Alumni Magazine Resources Order your Transcripts Give Back Alumni Programs Career Development Services & Support Accessibility Services Campus Services Campus Police Facilities & Services Registrar Faculty & Staff Resources Website Project Request Web Services Training & Tools Academic Impressions Career Connect CSA Reporting Cybersecurity Training Faculty Research FERPA Training Website Login Campus Resources Newsroom Campus Calendar Campus Maps i-Card Human Resources Public Relations Webtools Arts & Events UIS Performing Arts Center Visual Arts Gallery Event Calendar Sangamon Experience Center for Lincoln Studies ECCE Speaker Series Community Engagement Center for State Policy and Leadership Illinois Innocence Project Innovate Springfield Central IL Nonprofit Resource Center NPR Illinois Community Resources Child Protection Training Academy Office of Electronic Media University Archives/IRAD Institute for Illinois Public Finance

Request Info

How to Review a Journal Article

- Request Info Request info for.... Undergraduate/Graduate Online Study Away Continuing & Professional Education International Student Services General Inquiries

For many kinds of assignments, like a literature review , you may be asked to offer a critique or review of a journal article. This is an opportunity for you as a scholar to offer your qualified opinion and evaluation of how another scholar has composed their article, argument, and research. That means you will be expected to go beyond a simple summary of the article and evaluate it on a deeper level. As a college student, this might sound intimidating. However, as you engage with the research process, you are becoming immersed in a particular topic, and your insights about the way that topic is presented are valuable and can contribute to the overall conversation surrounding your topic.

IMPORTANT NOTE!!

Some disciplines, like Criminal Justice, may only want you to summarize the article without including your opinion or evaluation. If your assignment is to summarize the article only, please see our literature review handout.

Before getting started on the critique, it is important to review the article thoroughly and critically. To do this, we recommend take notes, annotating , and reading the article several times before critiquing. As you read, be sure to note important items like the thesis, purpose, research questions, hypotheses, methods, evidence, key findings, major conclusions, tone, and publication information. Depending on your writing context, some of these items may not be applicable.

Questions to Consider

To evaluate a source, consider some of the following questions. They are broken down into different categories, but answering these questions will help you consider what areas to examine. With each category, we recommend identifying the strengths and weaknesses in each since that is a critical part of evaluation.

Evaluating Purpose and Argument

- How well is the purpose made clear in the introduction through background/context and thesis?

- How well does the abstract represent and summarize the article’s major points and argument?

- How well does the objective of the experiment or of the observation fill a need for the field?

- How well is the argument/purpose articulated and discussed throughout the body of the text?

- How well does the discussion maintain cohesion?

Evaluating the Presentation/Organization of Information

- How appropriate and clear is the title of the article?

- Where could the author have benefited from expanding, condensing, or omitting ideas?

- How clear are the author’s statements? Challenge ambiguous statements.

- What underlying assumptions does the author have, and how does this affect the credibility or clarity of their article?

- How objective is the author in his or her discussion of the topic?

- How well does the organization fit the article’s purpose and articulate key goals?

Evaluating Methods

- How appropriate are the study design and methods for the purposes of the study?

- How detailed are the methods being described? Is the author leaving out important steps or considerations?

- Have the procedures been presented in enough detail to enable the reader to duplicate them?

Evaluating Data

- Scan and spot-check calculations. Are the statistical methods appropriate?

- Do you find any content repeated or duplicated?

- How many errors of fact and interpretation does the author include? (You can check on this by looking up the references the author cites).

- What pertinent literature has the author cited, and have they used this literature appropriately?

Following, we have an example of a summary and an evaluation of a research article. Note that in most literature review contexts, the summary and evaluation would be much shorter. This extended example shows the different ways a student can critique and write about an article.

Chik, A. (2012). Digital gameplay for autonomous foreign language learning: Gamers’ and language teachers’ perspectives. In H. Reinders (ed.), Digital games in language learning and teaching (pp. 95-114). Eastbourne, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Be sure to include the full citation either in a reference page or near your evaluation if writing an annotated bibliography .

In Chik’s article “Digital Gameplay for Autonomous Foreign Language Learning: Gamers’ and Teachers’ Perspectives”, she explores the ways in which “digital gamers manage gaming and gaming-related activities to assume autonomy in their foreign language learning,” (96) which is presented in contrast to how teachers view the “pedagogical potential” of gaming. The research was described as an “umbrella project” consisting of two parts. The first part examined 34 language teachers’ perspectives who had limited experience with gaming (only five stated they played games regularly) (99). Their data was recorded through a survey, class discussion, and a seven-day gaming trial done by six teachers who recorded their reflections through personal blog posts. The second part explored undergraduate gaming habits of ten Hong Kong students who were regular gamers. Their habits were recorded through language learning histories, videotaped gaming sessions, blog entries of gaming practices, group discussion sessions, stimulated recall sessions on gaming videos, interviews with other gamers, and posts from online discussion forums. The research shows that while students recognize the educational potential of games and have seen benefits of it in their lives, the instructors overall do not see the positive impacts of gaming on foreign language learning.

The summary includes the article’s purpose, methods, results, discussion, and citations when necessary.

This article did a good job representing the undergraduate gamers’ voices through extended quotes and stories. Particularly for the data collection of the undergraduate gamers, there were many opportunities for an in-depth examination of their gaming practices and histories. However, the representation of the teachers in this study was very uneven when compared to the students. Not only were teachers labeled as numbers while the students picked out their own pseudonyms, but also when viewing the data collection, the undergraduate students were more closely examined in comparison to the teachers in the study. While the students have fifteen extended quotes describing their experiences in their research section, the teachers only have two of these instances in their section, which shows just how imbalanced the study is when presenting instructor voices.

Some research methods, like the recorded gaming sessions, were only used with students whereas teachers were only asked to blog about their gaming experiences. This creates a richer narrative for the students while also failing to give instructors the chance to have more nuanced perspectives. This lack of nuance also stems from the emphasis of the non-gamer teachers over the gamer teachers. The non-gamer teachers’ perspectives provide a stark contrast to the undergraduate gamer experiences and fits neatly with the narrative of teachers not valuing gaming as an educational tool. However, the study mentioned five teachers that were regular gamers whose perspectives are left to a short section at the end of the presentation of the teachers’ results. This was an opportunity to give the teacher group a more complex story, and the opportunity was entirely missed.

Additionally, the context of this study was not entirely clear. The instructors were recruited through a master’s level course, but the content of the course and the institution’s background is not discussed. Understanding this context helps us understand the course’s purpose(s) and how those purposes may have influenced the ways in which these teachers interpreted and saw games. It was also unclear how Chik was connected to this masters’ class and to the students. Why these particular teachers and students were recruited was not explicitly defined and also has the potential to skew results in a particular direction.

Overall, I was inclined to agree with the idea that students can benefit from language acquisition through gaming while instructors may not see the instructional value, but I believe the way the research was conducted and portrayed in this article made it very difficult to support Chik’s specific findings.

Some professors like you to begin an evaluation with something positive but isn’t always necessary.

The evaluation is clearly organized and uses transitional phrases when moving to a new topic.

This evaluation includes a summative statement that gives the overall impression of the article at the end, but this can also be placed at the beginning of the evaluation.

This evaluation mainly discusses the representation of data and methods. However, other areas, like organization, are open to critique.

404 Not found

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Article review writing format, steps, examples and illustration PDF Compiled by Mohammed Yismaw

2021, Article review writing format, steps, examples and illustration PDF Compiled by Mohammed Yismaw

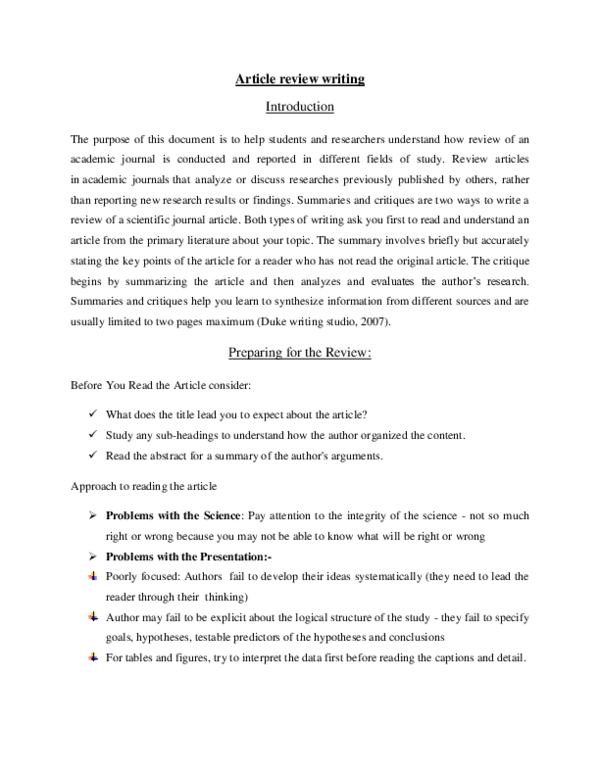

The purpose of this document is to help students and researchers understand how a review of an academic journal is conducted and reported in different fields of study. Review articles in academic journals that analyze or discuss researches previously published by others, rather than reporting new research results or findings. Summaries and critiques are two ways to write a review of a scientific journal article. Both types of writing ask you first to read and understand an article from the primary literature about your topic. The summary involves briefly but accurately stating the key points of the article for a reader who has not read the original article. The critique begins by summarizing the article and then analyzes and evaluates the author’s research. Summaries and critiques help you learn to synthesize information from different sources and are usually limited to two pages maximum.

Related Papers

Harald von Kortzfleisch , Christoph Kahle

Neue Technologien und Innovationen stellen heutzutage wichtige Schlüsselelemente der Wachstums und Erfolgssicherung von Unternehmen dar. Durch einen in Geschwindigkeit und Intensität immer schneller zunehmenden Wettbewerb nehmen Innovationen eine immer zentralere Rolle im Praxisalltag von Unternehmen ein. Dieser technische Fortschritt treibt auch in der Wissenschaft das Thema des Innovationsmanagements in den letzten Jahrzehnten immer stärker voran und wird dort ausgiebig diskutiert. Die Bedeutung von Innovationen wächst dabei ebenfalls aus der Sicht der Kunden, welche heutzutage viel differenzierter als früher Produkte und Dienste nachfragen und somit Unternehmen vor neue Herausforderungen stellen. Ãberdies stellen Innovationen heute ein entscheidendes Bindeglied zwischen Marktorientierung und erhofften Unternehmenserfolg dar. Seit einigen Jahren lässt sich eine Ãffnung der Unternehmensgrenzen für externe Quellen wie Kunden, Zulieferer, Universitäten oder teilweise auch M...

SSRN Electronic Journal

Helmut Krcmar

Dominic Lindner

Alexandra Waluszewski

Research Policy

Nuria Gonzalez Alvarez

Creativity and Innovation Management

Matti Pihlajamaa

Firms tap into user knowledge to learn about the users’ needs. While users have been recognized as a valuable source of knowledge for innovation, few studies have investigated how their knowledge is integrated into innovation processes in the context of complex products and systems (CoPS). The purpose of this study is to reveal the practices of CoPS manufacturers to facilitate user knowledge utilization for innovation. We investigate two case companies, a medical device manufacturer and an aircraft manufacturer, and report on seven managerial practices for utilizing user knowledge. We adopt the absorptive capacity model in structuring our findings and elaborate three of the model's sub-capabilities (recognition of the value of user knowledge, acquisition of user knowledge, and assimilation/transformation of user knowledge) by proposing that each is associated with a distinct managerial goal and related practices: (1) Sensitizing the organization to the innovation potential of user knowledge, (2) identifying and gaining access to suitable user knowledge, and (3) analyzing and interpreting user knowledge and integrating it into product development. Our study contributes to the innovation management literature by analyzing the capabilities required to utilize user knowledge throughout the CoPS innovation process.

Information & Management