Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

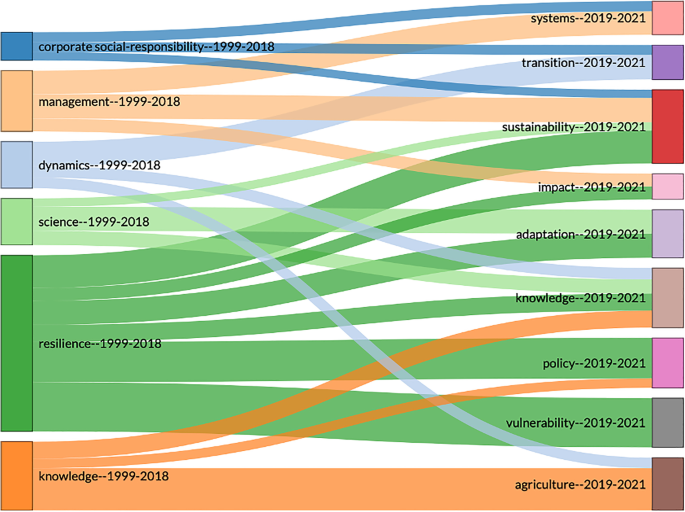

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

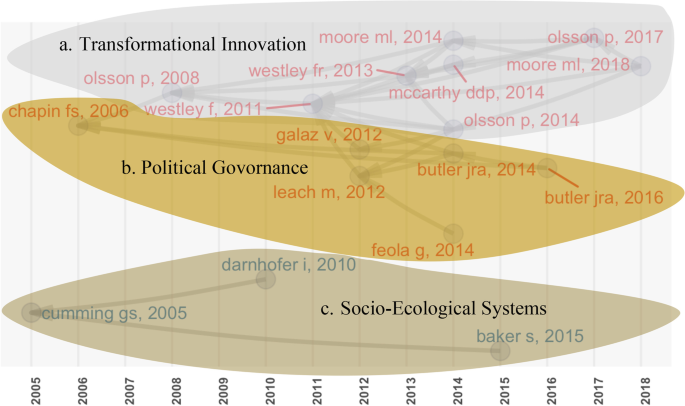

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Teesside University Student & Library Services

- Learning Hub Group

Research Methods

Secondary research.

- Primary Research

What is Secondary Research?

Advantages and disadvantages of secondary research, secondary research in literature reviews, secondary research - going beyond literature reviews, main stages of secondary research, useful resources, using material on this page.

- Quantitative Research This link opens in a new window

- Qualitative Research This link opens in a new window

- Being Critical This link opens in a new window

- Subject LibGuides This link opens in a new window

Secondary research

Secondary research uses research and data that has already been carried out. It is sometimes referred to as desk research. It is a good starting point for any type of research as it enables you to analyse what research has already been undertaken and identify any gaps.

You may only need to carry out secondary research for your assessment or you may need to use secondary research as a starting point, before undertaking your own primary research .

Searching for both primary and secondary sources can help to ensure that you are up to date with what research has already been carried out in your area of interest and to identify the key researchers in the field.

"Secondary sources are the books, articles, papers and similar materials written or produced by others that help you to form your background understanding of the subject. You would use these to find out about experts’ findings, analyses or perspectives on the issue and decide whether to draw upon these explicitly in your research." (Cottrell, 2014, p. 123).

Examples of secondary research sources include:.

- journal articles

- official statistics, such as government reports or organisations which have collected and published data

Primary research involves gathering data which has not been collected before. Methods to collect it can include interviews, focus groups, controlled trials and case studies. Secondary research often comments on and analyses this primary research.

Gopalakrishnan and Ganeshkumar (2013, p. 10) explain the difference between primary and secondary research:

"Primary research is collecting data directly from patients or population, while secondary research is the analysis of data already collected through primary research. A review is an article that summarizes a number of primary studies and may draw conclusions on the topic of interest which can be traditional (unsystematic) or systematic".

Secondary Data

As secondary data has already been collected by someone else for their research purposes, it may not cover all of the areas of interest for your research topic. This research will need to be analysed alongside other research sources and data in the same subject area in order to confirm, dispute or discuss the findings in a wider context.

"Secondary source data, as the name infers, provides second-hand information. The data come ‘pre-packaged’, their form and content reflecting the fact that they have been produced by someone other than the researcher and will not have been produced specifically for the purpose of the research project. The data, none the less, will have some relevance for the research in terms of the information they contain, and the task for the researcher is to extract that information and re-use it in the context of his/her own research project." (Denscombe, 2021, p. 268)

In the video below Dr. Benedict Wheeler (Senior Research Fellow at the European Center for Environment and Human Health at the University of Exeter Medical School) discusses secondary data analysis. Secondary data was used for his research on how the environment affects health and well-being and utilising this secondary data gave access to a larger data set.

As with all research, an important part of the process is to critically evaluate any sources you use. There are tools to help with this in the Being Critical section of the guide.

Louise Corti, from the UK Data Archive, discusses using secondary data in the video below. T he importance of evaluating secondary research is discussed - this is to ensure the data is appropriate for your research and to investigate how the data was collected.

There are advantages and disadvantages to secondary research:

Advantages:

- Usually low cost

- Easily accessible

- Provides background information to clarify / refine research areas

- Increases breadth of knowledge

- Shows different examples of research methods

- Can highlight gaps in the research and potentially outline areas of difficulty

- Can incorporate a wide range of data

- Allows you to identify opposing views and supporting arguments for your research topic

- Highlights the key researchers and work which is being undertaken within the subject area

- Helps to put your research topic into perspective

Disadvantages

- Can be out of date

- Might be unreliable if it is not clear where or how the research has been collected - remember to think critically

- May not be applicable to your specific research question as the aims will have had a different focus

Literature reviews

Secondary research for your major project may take the form of a literature review . this is where you will outline the main research which has already been written on your topic. this might include theories and concepts connected with your topic and it should also look to see if there are any gaps in the research., as the criteria and guidance will differ for each school, it is important that you check the guidance which you have been given for your assessment. this may be in blackboard and you can also check with your supervisor..

The videos below include some insights from academics regarding the importance of literature reviews.

Secondary research which goes beyond literature reviews

For some dissertations/major projects there might only be a literature review (discussed above ). For others there could be a literature review followed by primary research and for others the literature review might be followed by further secondary research.

You may be asked to write a literature review which will form a background chapter to give context to your project and provide the necessary history for the research topic. However, you may then also be expected to produce the rest of your project using additional secondary research methods, which will need to produce results and findings which are distinct from the background chapter t o avoid repetition .

Remember, as the criteria and guidance will differ for each School, it is important that you check the guidance which you have been given for your assessment. This may be in Blackboard and you can also check with your supervisor.

Although this type of secondary research will go beyond a literature review, it will still rely on research which has already been undertaken. And, "just as in primary research, secondary research designs can be either quantitative, qualitative, or a mixture of both strategies of inquiry" (Manu and Akotia, 2021, p. 4) .

Your secondary research may use the literature review to focus on a specific theme, which is then discussed further in the main project. Or it may use an alternative approach. Some examples are included below. Remember to speak with your supervisor if you are struggling to define these areas.

Some approaches of how to conduct secondary research include:

- A systematic review is a structured literature review that involves identifying all of the relevant primary research using a rigorous search strategy to answer a focused research question.

- This involves comprehensive searching which is used to identify themes or concepts across a number of relevant studies.

- The review will assess the q uality of the research and provide a summary and synthesis of all relevant available research on the topic.

- The systematic review LibGuide goes into more detail about this process (The guide is aimed a PhD/Researcher students. However, students on other levels of study may find parts of the guide helpful too).

- Scoping reviews aim to identify and assess available research on a specific topic (which can include ongoing research).

- They are "particularly useful when a body of literature has not yet been comprehensively reviewed, or exhibits a complex or heterogeneous nature not amenable to a more precise systematic review of the evidence. While scoping reviews may be conducted to determine the value and probable scope of a full systematic review, they may also be undertaken as exercises in and of themselves to summarize and disseminate research findings, to identify research gaps, and to make recommendations for the future research." (Peters et al., 2015) .

- This is designed to summarise the current knowledge and provide priorities for future research.

- "A state-of-the-art review will often highlight new ideas or gaps in research with no official quality assessment." (Baguss, 2020) .

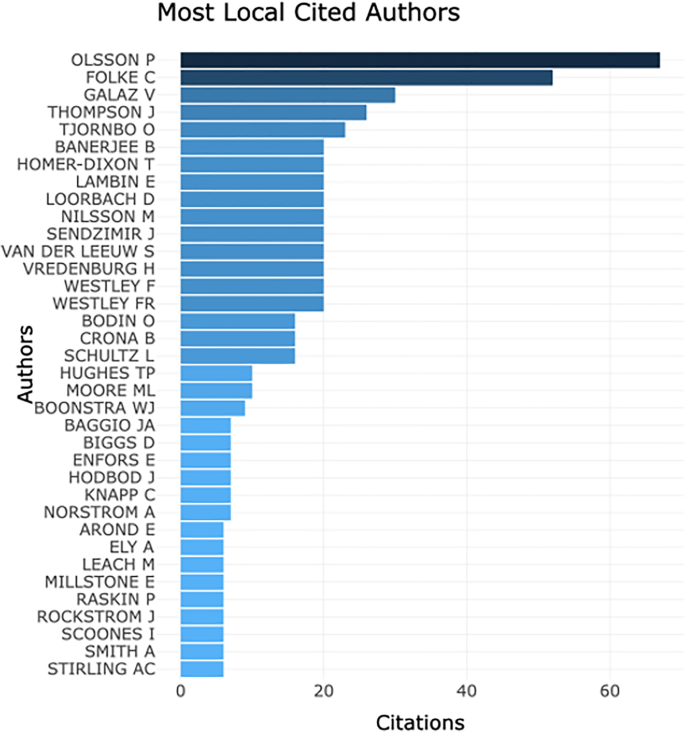

- "Bibliometric analysis is a popular and rigorous method for exploring and analyzing large volumes of scientific data." (Donthu et al., 2021)

- Quantitative methods and statistics are used to analyse the bibliographic data of published literature. This can be used to measure the impact of authors, publications, or topics within a subject area.

The bibliometric analysis often uses the data from a citation source such as Scopus or Web of Science .

- This is a technique used to combine the statistic results of prior quantitative studies in order to increase precision and validity.

- "It goes beyond the parameters of a literature review, which assesses existing literature, to actually perform calculations based on the results collated, thereby coming up with new results" (Curtis and Curtis, 2011, p. 220)

(Adapted from: Grant and Booth, 2009, cited in Sarhan and Manu, 2021, p. 72 )

- Grounded Theory is used to create explanatory theory from data which has been collected.

- "Grounded theory data analysis strategies can be used with different types of data, including secondary data." ( Whiteside, Mills and McCalman, 2012 )

- This allows you to use a specific theory or theories which can then be applied to your chosen topic/research area.

- You could focus on one case study which is analysed in depth, or you could examine more than one in order to compare and contrast the important aspects of your research question.

- "Good case studies often begin with a predicament that is poorly comprehended and is inadequately explained or traditionally rationalised by numerous conflicting accounts. Therefore, the aim is to comprehend an existent problem and to use the acquired understandings to develop new theoretical outlooks or explanations." ( Papachroni and Lochrie, 2015, p. 81 )

Main stages of secondary research for a dissertation/major project

In general, the main stages for conducting secondary research for your dissertation or major project will include:

Click on the image below to access the reading list which includes resources used in this guide as well as some additional useful resources.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License .

- << Previous: Primary Research

- Next: Quantitative Research >>

- Last Updated: Aug 11, 2022 3:41 PM

- URL: https://libguides.tees.ac.uk/researchmethods

Understanding research and critical appraisal

- Introduction

What is secondary research?

Secondary research study designs.

- Primary research

- Critical appraisal of research papers

- Useful terminology

- Further reading and helpful resources

The aim of secondary research is to produce a more or less systematic appraisal and/or synthesis of the existing primary research on a topic. There are numerous types of reviews which aim to summarise or synthesise the evidence on a topic, but here we will focus on two: meta-analyses and systematic reviews.

For a fuller discussion of the range of review types, their features and uses, see: Sutton, A. et al . (2019) 'Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements', Health Information and Libraries Journal , 36 (3), pp. 202-222. doi:10.1111/hir.12276

Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis is a statistical synthesis of the results from multiple individual studies, usually randomised controlled trials (RCTs),

Carrying out a meta-analysis of studies allows results from multiple studies looking at the effect of an intervention to be combined, allowing for greater precision in the estimation of effects, and clarity over the direction and size of an effect. A meta-analysis can provide more conclusive evidence for or against the effectiveness of an intervention than individual studies alone.

A good meta-analysis should always be based on a systematic review of studies, and requires some homogeneity of participants, settings, interventions and outcome measures in the studies included.

Systematic review

A systematic review is not simply a literature review. A systematic review is a study which aims to synthesise all of the available primary research on a specific topic. The first step in a systematic review is a thorough search of all appropriate sources, including subject related databases, clinical trial registers and grey literature, in order to identify all of the relevant evidence. These searches should ideally be carried out by a librarian or information specialist in the field, or by others with a similar level of expertise. The systematic review itself should be carried out by two or more researchers, as a means of reducing possible bias.

All identified studies are screened for inclusion or exclusion according to strict criteria set out at the start of the study, and the data from those studies selected for inclusion is analysed and synthesised. Part of this process is an attempt to identify any potential source of bias in existing findings. A systematic review will offer a summary of the available research findings, and offer conclusions on the basis of these, taking into account any flaws or limitations in the original studies.

A systematic review can offer more generalisability and consistency of research findings than the individual studies on which it is based.

Systematic reviews may employ quantitative, qualitative (experiential), or mixed-methods approaches.

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Primary research >>

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 4:38 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sgul.ac.uk/researchdesign

Secondary Research Guide: Definition, Methods, Examples

Apr 3, 2024

8 min. read

The internet has vastly expanded our access to information, allowing us to learn almost anything about everything. But not all market research is created equal , and this secondary research guide explains why.

There are two key ways to do research. One is to test your own ideas, make your own observations, and collect your own data to derive conclusions. The other is to use secondary research — where someone else has done most of the heavy lifting for you.

Here’s an overview of secondary research and the value it brings to data-driven businesses.

Secondary Research Definition: What Is Secondary Research?

Primary vs Secondary Market Research

What Are Secondary Research Methods?

Advantages of secondary research, disadvantages of secondary research, best practices for secondary research, how to conduct secondary research with meltwater.

Secondary research definition: The process of collecting information from existing sources and data that have already been analyzed by others.

Secondary research (aka desk research ) provides a foundation to help you understand a topic, with the goal of building on existing knowledge. They often cover the same information as primary sources, but they add a layer of analysis and explanation to them.

Users can choose from several secondary research types and sources, including:

- Journal articles

- Research papers

With secondary sources, users can draw insights, detect trends , and validate findings to jumpstart their research efforts.

Primary vs. Secondary Market Research

We’ve touched a little on primary research , but it’s essential to understand exactly how primary and secondary research are unique.

Think of primary research as the “thing” itself, and secondary research as the analysis of the “thing,” like these primary and secondary research examples:

- An expert gives an interview (primary research) and a marketer uses that interview to write an article (secondary research).

- A company conducts a consumer satisfaction survey (primary research) and a business analyst uses the survey data to write a market trend report (secondary research).

- A marketing team launches a new advertising campaign across various platforms (primary research) and a marketing research firm, like Meltwater for market research , compiles the campaign performance data to benchmark against industry standards (secondary research).

In other words, primary sources make original contributions to a topic or issue, while secondary sources analyze, synthesize, or interpret primary sources.

Both are necessary when optimizing a business, gaining a competitive edge , improving marketing, or understanding consumer trends that may impact your business.

Secondary research methods focus on analyzing existing data rather than collecting primary data . Common examples of secondary research methods include:

- Literature review . Researchers analyze and synthesize existing literature (e.g., white papers, research papers, articles) to find knowledge gaps and build on current findings.

- Content analysis . Researchers review media sources and published content to find meaningful patterns and trends.

- AI-powered secondary research . Platforms like Meltwater for market research analyze vast amounts of complex data and use AI technologies like natural language processing and machine learning to turn data into contextual insights.

Researchers today have access to more market research tools and technology than ever before, allowing them to streamline their efforts and improve their findings.

Want to see how Meltwater can complement your secondary market research efforts? Simply fill out the form at the bottom of this post, and we'll be in touch.

Conducting secondary research offers benefits in every job function and use case, from marketing to the C-suite. Here are a few advantages you can expect.

Cost and time efficiency

Using existing research saves you time and money compared to conducting primary research. Secondary data is readily available and easily accessible via libraries, free publications, or the Internet. This is particularly advantageous when you face time constraints or when a project requires a large amount of data and research.

Access to large datasets

Secondary data gives you access to larger data sets and sample sizes compared to what primary methods may produce. Larger sample sizes can improve the statistical power of the study and add more credibility to your findings.

Ability to analyze trends and patterns

Using larger sample sizes, researchers have more opportunities to find and analyze trends and patterns. The more data that supports a trend or pattern, the more trustworthy the trend becomes and the more useful for making decisions.

Historical context

Using a combination of older and recent data allows researchers to gain historical context about patterns and trends. Learning what’s happened before can help decision-makers gain a better current understanding and improve how they approach a problem or project.

Basis for further research

Ideally, you’ll use secondary research to further other efforts . Secondary sources help to identify knowledge gaps, highlight areas for improvement, or conduct deeper investigations.

Tip: Learn how to use Meltwater as a research tool and how Meltwater uses AI.

Secondary research comes with a few drawbacks, though these aren’t necessarily deal breakers when deciding to use secondary sources.

Reliability concerns

Researchers don’t always know where the data comes from or how it’s collected, which can lead to reliability concerns. They don’t control the initial process, nor do they always know the original purpose for collecting the data, both of which can lead to skewed results.

Potential bias

The original data collectors may have a specific agenda when doing their primary research, which may lead to biased findings. Evaluating the credibility and integrity of secondary data sources can prove difficult.

Outdated information

Secondary sources may contain outdated information, especially when dealing with rapidly evolving trends or fields. Using outdated information can lead to inaccurate conclusions and widen knowledge gaps.

Limitations in customization

Relying on secondary data means being at the mercy of what’s already published. It doesn’t consider your specific use cases, which limits you as to how you can customize and use the data.

A lack of relevance

Secondary research rarely holds all the answers you need, at least from a single source. You typically need multiple secondary sources to piece together a narrative, and even then you might not find the specific information you need.

To make secondary market research your new best friend, you’ll need to think critically about its strengths and find ways to overcome its weaknesses. Let’s review some best practices to use secondary research to its fullest potential.

Identify credible sources for secondary research

To overcome the challenges of bias, accuracy, and reliability, choose secondary sources that have a demonstrated history of excellence . For example, an article published in a medical journal naturally has more credibility than a blog post on a little-known website.

Assess credibility based on peer reviews, author expertise, sampling techniques, publication reputation, and data collection methodologies. Cross-reference the data with other sources to gain a general consensus of truth.

The more credibility “factors” a source has, the more confidently you can rely on it.

Evaluate the quality and relevance of secondary data

You can gauge the quality of the data by asking simple questions:

- How complete is the data?

- How old is the data?

- Is this data relevant to my needs?

- Does the data come from a known, trustworthy source?

It’s best to focus on data that aligns with your research objectives. Knowing the questions you want to answer and the outcomes you want to achieve ahead of time helps you focus only on data that offers meaningful insights.

Document your sources

If you’re sharing secondary data with others, it’s essential to document your sources to gain others’ trust. They don’t have the benefit of being “in the trenches” with you during your research, and sharing your sources can add credibility to your findings and gain instant buy-in.

Secondary market research offers an efficient, cost-effective way to learn more about a topic or trend, providing a comprehensive understanding of the customer journey . Compared to primary research, users can gain broader insights, analyze trends and patterns, and gain a solid foundation for further exploration by using secondary sources.

Meltwater for market research speeds up the time to value in using secondary research with AI-powered insights, enhancing your understanding of the customer journey. Using natural language processing, machine learning, and trusted data science processes, Meltwater helps you find relevant data and automatically surfaces insights to help you understand its significance. Our solution identifies hidden connections between data points you might not know to look for and spells out what the data means, allowing you to make better decisions based on accurate conclusions. Learn more about Meltwater's power as a secondary research solution when you request a demo by filling out the form below:

Continue Reading

How To Do Market Research: Definition, Types, Methods

What Are Consumer Insights? Meaning, Examples, Strategy

Market Intelligence 101: What It Is & How To Use It

The 13 Best Market Research Tools

Consumer Intelligence: Definition & Examples

9 Top Consumer Insights Tools & Companies

What Is Desk Research? Meaning, Methodology, Examples

Research Basics

- What Is Research?

- Types of Research

- Secondary Research | Literature Review

- Developing Your Topic

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Evaluating Sources

- Responsible Conduct of Research

- Additional Help

What is Secondary Research?

Secondary research, also known as a literature review , preliminary research , historical research , background research , desk research , or library research , is research that analyzes or describes prior research. Rather than generating and analyzing new data, secondary research analyzes existing research results to establish the boundaries of knowledge on a topic, to identify trends or new practices, to test mathematical models or train machine learning systems, or to verify facts and figures. Secondary research is also used to justify the need for primary research as well as to justify and support other activities. For example, secondary research may be used to support a proposal to modernize a manufacturing plant, to justify the use of newly a developed treatment for cancer, to strengthen a business proposal, or to validate points made in a speech.

The following guides, published by the library, offer more information on how to do secondary research or a literature review:

- << Previous: Types of Research

- Next: Developing Your Topic >>

- Last Updated: Dec 21, 2023 3:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.iit.edu/research_basics

Library Research Skills for Biologists

- Choose your own research adventure

- The cycle of scholarly communication

- Primary literature

Secondary literature

- Tertiary literature

- QUIZ 01: Stages of scholarly communication

- Popular writing

- Popular science writing

- Scholarly writing

- Quiz 02: Activity Break

- Keywords = search terms

- ACTIVITY BREAK - Identify search terms

- Combining concepts

- Phrase searching

- Quiz 03: Boolean operators

- What is Summon?

- Refine your search

- Reference books

- Finding a book from a citation

- Print book location

- Using print books effectively

- What if an article is not available at UBC?

- Why use advanced tools?

- Article indexes

- Subject headings

- Web of Science

- Finding government information using Summon

- Finding government information using Google

- Research Guides

- What is plagiarism?

- Common knowledge

- Paraphrasing vs. summarizing

- What is citing?

- How to cite your sources

- Tools for managing research literature

- Evaluating sources

- Evaluation tools

How can I use this?

Secondary Sources are useful for both gaining a broad knowledge of a topic area (e.g review papers), and for understanding how certain discoveries or projects were received by the scholarly community. They give you opinions, analysis, and a discussion of impact which you can use to place primary sources in context.

What is secondary literature?

When other writers summarize or review the theories and results of original scientific research, their publications are known as Secondary Literature . These publication types serve to synthesize the findings to date and present the ideas to a wider audience. Examples of secondary literature include:

- Review articles

- Edited volumes

- Books summarizing research in an area

- Abstracts and Indexes - Tools used to find articles in scholarly journals

Secondary literature is not as current as the primary literature but it is often more descriptive and is useful for finding introductory material.

Insulin: Discussing the experiment and finding papers

References cited.

[1] Grodsky, G.M. 1970. Insulin and the pancreas. Vitamins & Hormones , 28: 37-101.

- << Previous: Primary literature

- Next: Tertiary literature >>

- Last Updated: Mar 1, 2024 3:23 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ubc.ca/tutorial-biology

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Secondary Sources

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

In the social sciences, a secondary source is usually a scholar book, journal article, or digital or print document that was created by someone who did not directly experience or participate in the events or conditions under investigation. Secondary sources are not evidence per se, but rather, provide an interpretation, analysis, or commentary derived from the content of primary source materials and/or other secondary sources.

Value of Secondary Sources

To do research, you must cite research. Primary sources do not represent research per se, but only the artifacts from which most research is derived. Therefore, the majority of sources in a literature review are secondary sources that present research findings, analysis, and the evaluation of other researcher's works.

Reviewing secondary source material can be of valu e in improving your overall research paper because secondary sources facilitate the communication of what is known about a topic. This literature also helps you understand the level of uncertainty about what is currently known and what additional information is needed from further research. It is important to note, however, that secondary sources are not the subject of your analysis. Instead, they represent various opinions, interpretations, and arguments about the research problem you are investigating--opinions, interpretations, and arguments with which you may either agree or disagree with as part of your own analysis of the literature.

Examples of secondary sources you could review as part of your overall study include: * Bibliographies [also considered tertiary] * Biographical works * Books, other than fiction and autobiography * Commentaries, criticisms * Dictionaries, Encyclopedias [also considered tertiary] * Histories * Journal articles [depending on the discipline, they can be primary] * Magazine and newspaper articles [this distinction varies by discipline] * Textbooks [also considered tertiary] * Web site [also considered primary]

- << Previous: Primary Sources

- Next: Tiertiary Sources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 1:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Employee Exit Interviews

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

Market Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Secondary Research

Try Qualtrics for free

Secondary research: definition, methods, & examples.

19 min read This ultimate guide to secondary research helps you understand changes in market trends, customers buying patterns and your competition using existing data sources.

In situations where you’re not involved in the data gathering process ( primary research ), you have to rely on existing information and data to arrive at specific research conclusions or outcomes. This approach is known as secondary research.

In this article, we’re going to explain what secondary research is, how it works, and share some examples of it in practice.

Free eBook: The ultimate guide to conducting market research

What is secondary research?

Secondary research, also known as desk research, is a research method that involves compiling existing data sourced from a variety of channels . This includes internal sources (e.g.in-house research) or, more commonly, external sources (such as government statistics, organizational bodies, and the internet).

Secondary research comes in several formats, such as published datasets, reports, and survey responses , and can also be sourced from websites, libraries, and museums.

The information is usually free — or available at a limited access cost — and gathered using surveys , telephone interviews, observation, face-to-face interviews, and more.

When using secondary research, researchers collect, verify, analyze and incorporate it to help them confirm research goals for the research period.

As well as the above, it can be used to review previous research into an area of interest. Researchers can look for patterns across data spanning several years and identify trends — or use it to verify early hypothesis statements and establish whether it’s worth continuing research into a prospective area.

How to conduct secondary research

There are five key steps to conducting secondary research effectively and efficiently:

1. Identify and define the research topic

First, understand what you will be researching and define the topic by thinking about the research questions you want to be answered.

Ask yourself: What is the point of conducting this research? Then, ask: What do we want to achieve?

This may indicate an exploratory reason (why something happened) or confirm a hypothesis. The answers may indicate ideas that need primary or secondary research (or a combination) to investigate them.

2. Find research and existing data sources

If secondary research is needed, think about where you might find the information. This helps you narrow down your secondary sources to those that help you answer your questions. What keywords do you need to use?

Which organizations are closely working on this topic already? Are there any competitors that you need to be aware of?

Create a list of the data sources, information, and people that could help you with your work.

3. Begin searching and collecting the existing data

Now that you have the list of data sources, start accessing the data and collect the information into an organized system. This may mean you start setting up research journal accounts or making telephone calls to book meetings with third-party research teams to verify the details around data results.

As you search and access information, remember to check the data’s date, the credibility of the source, the relevance of the material to your research topic, and the methodology used by the third-party researchers. Start small and as you gain results, investigate further in the areas that help your research’s aims.

4. Combine the data and compare the results

When you have your data in one place, you need to understand, filter, order, and combine it intelligently. Data may come in different formats where some data could be unusable, while other information may need to be deleted.

After this, you can start to look at different data sets to see what they tell you. You may find that you need to compare the same datasets over different periods for changes over time or compare different datasets to notice overlaps or trends. Ask yourself: What does this data mean to my research? Does it help or hinder my research?

5. Analyze your data and explore further

In this last stage of the process, look at the information you have and ask yourself if this answers your original questions for your research. Are there any gaps? Do you understand the information you’ve found? If you feel there is more to cover, repeat the steps and delve deeper into the topic so that you can get all the information you need.

If secondary research can’t provide these answers, consider supplementing your results with data gained from primary research. As you explore further, add to your knowledge and update your findings. This will help you present clear, credible information.

Primary vs secondary research

Unlike secondary research, primary research involves creating data first-hand by directly working with interviewees, target users, or a target market. Primary research focuses on the method for carrying out research, asking questions, and collecting data using approaches such as:

- Interviews (panel, face-to-face or over the phone)

- Questionnaires or surveys

- Focus groups

Using these methods, researchers can get in-depth, targeted responses to questions, making results more accurate and specific to their research goals. However, it does take time to do and administer.

Unlike primary research, secondary research uses existing data, which also includes published results from primary research. Researchers summarize the existing research and use the results to support their research goals.

Both primary and secondary research have their places. Primary research can support the findings found through secondary research (and fill knowledge gaps), while secondary research can be a starting point for further primary research. Because of this, these research methods are often combined for optimal research results that are accurate at both the micro and macro level.

Sources of Secondary Research

There are two types of secondary research sources: internal and external. Internal data refers to in-house data that can be gathered from the researcher’s organization. External data refers to data published outside of and not owned by the researcher’s organization.

Internal data

Internal data is a good first port of call for insights and knowledge, as you may already have relevant information stored in your systems. Because you own this information — and it won’t be available to other researchers — it can give you a competitive edge . Examples of internal data include:

- Database information on sales history and business goal conversions

- Information from website applications and mobile site data

- Customer-generated data on product and service efficiency and use

- Previous research results or supplemental research areas

- Previous campaign results

External data

External data is useful when you: 1) need information on a new topic, 2) want to fill in gaps in your knowledge, or 3) want data that breaks down a population or market for trend and pattern analysis. Examples of external data include:

- Government, non-government agencies, and trade body statistics

- Company reports and research

- Competitor research

- Public library collections

- Textbooks and research journals

- Media stories in newspapers

- Online journals and research sites

Three examples of secondary research methods in action

How and why might you conduct secondary research? Let’s look at a few examples:

1. Collecting factual information from the internet on a specific topic or market

There are plenty of sites that hold data for people to view and use in their research. For example, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, or Wiley Online Library all provide previous research on a particular topic. Researchers can create free accounts and use the search facilities to look into a topic by keyword, before following the instructions to download or export results for further analysis.

This can be useful for exploring a new market that your organization wants to consider entering. For instance, by viewing the U.S Census Bureau demographic data for that area, you can see what the demographics of your target audience are , and create compelling marketing campaigns accordingly.

2. Finding out the views of your target audience on a particular topic

If you’re interested in seeing the historical views on a particular topic, for example, attitudes to women’s rights in the US, you can turn to secondary sources.

Textbooks, news articles, reviews, and journal entries can all provide qualitative reports and interviews covering how people discussed women’s rights. There may be multimedia elements like video or documented posters of propaganda showing biased language usage.

By gathering this information, synthesizing it, and evaluating the language, who created it and when it was shared, you can create a timeline of how a topic was discussed over time.

3. When you want to know the latest thinking on a topic

Educational institutions, such as schools and colleges, create a lot of research-based reports on younger audiences or their academic specialisms. Dissertations from students also can be submitted to research journals, making these places useful places to see the latest insights from a new generation of academics.

Information can be requested — and sometimes academic institutions may want to collaborate and conduct research on your behalf. This can provide key primary data in areas that you want to research, as well as secondary data sources for your research.

Advantages of secondary research

There are several benefits of using secondary research, which we’ve outlined below:

- Easily and readily available data – There is an abundance of readily accessible data sources that have been pre-collected for use, in person at local libraries and online using the internet. This data is usually sorted by filters or can be exported into spreadsheet format, meaning that little technical expertise is needed to access and use the data.

- Faster research speeds – Since the data is already published and in the public arena, you don’t need to collect this information through primary research. This can make the research easier to do and faster, as you can get started with the data quickly.

- Low financial and time costs – Most secondary data sources can be accessed for free or at a small cost to the researcher, so the overall research costs are kept low. In addition, by saving on preliminary research, the time costs for the researcher are kept down as well.

- Secondary data can drive additional research actions – The insights gained can support future research activities (like conducting a follow-up survey or specifying future detailed research topics) or help add value to these activities.

- Secondary data can be useful pre-research insights – Secondary source data can provide pre-research insights and information on effects that can help resolve whether research should be conducted. It can also help highlight knowledge gaps, so subsequent research can consider this.

- Ability to scale up results – Secondary sources can include large datasets (like Census data results across several states) so research results can be scaled up quickly using large secondary data sources.

Disadvantages of secondary research

The disadvantages of secondary research are worth considering in advance of conducting research :

- Secondary research data can be out of date – Secondary sources can be updated regularly, but if you’re exploring the data between two updates, the data can be out of date. Researchers will need to consider whether the data available provides the right research coverage dates, so that insights are accurate and timely, or if the data needs to be updated. Also, fast-moving markets may find secondary data expires very quickly.

- Secondary research needs to be verified and interpreted – Where there’s a lot of data from one source, a researcher needs to review and analyze it. The data may need to be verified against other data sets or your hypotheses for accuracy and to ensure you’re using the right data for your research.

- The researcher has had no control over the secondary research – As the researcher has not been involved in the secondary research, invalid data can affect the results. It’s therefore vital that the methodology and controls are closely reviewed so that the data is collected in a systematic and error-free way.

- Secondary research data is not exclusive – As data sets are commonly available, there is no exclusivity and many researchers can use the same data. This can be problematic where researchers want to have exclusive rights over the research results and risk duplication of research in the future.

When do we conduct secondary research?

Now that you know the basics of secondary research, when do researchers normally conduct secondary research?

It’s often used at the beginning of research, when the researcher is trying to understand the current landscape . In addition, if the research area is new to the researcher, it can form crucial background context to help them understand what information exists already. This can plug knowledge gaps, supplement the researcher’s own learning or add to the research.

Secondary research can also be used in conjunction with primary research. Secondary research can become the formative research that helps pinpoint where further primary research is needed to find out specific information. It can also support or verify the findings from primary research.

You can use secondary research where high levels of control aren’t needed by the researcher, but a lot of knowledge on a topic is required from different angles.

Secondary research should not be used in place of primary research as both are very different and are used for various circumstances.

Questions to ask before conducting secondary research

Before you start your secondary research, ask yourself these questions:

- Is there similar internal data that we have created for a similar area in the past?

If your organization has past research, it’s best to review this work before starting a new project. The older work may provide you with the answers, and give you a starting dataset and context of how your organization approached the research before. However, be mindful that the work is probably out of date and view it with that note in mind. Read through and look for where this helps your research goals or where more work is needed.

- What am I trying to achieve with this research?

When you have clear goals, and understand what you need to achieve, you can look for the perfect type of secondary or primary research to support the aims. Different secondary research data will provide you with different information – for example, looking at news stories to tell you a breakdown of your market’s buying patterns won’t be as useful as internal or external data e-commerce and sales data sources.

- How credible will my research be?

If you are looking for credibility, you want to consider how accurate the research results will need to be, and if you can sacrifice credibility for speed by using secondary sources to get you started. Bear in mind which sources you choose — low-credibility data sites, like political party websites that are highly biased to favor their own party, would skew your results.

- What is the date of the secondary research?

When you’re looking to conduct research, you want the results to be as useful as possible , so using data that is 10 years old won’t be as accurate as using data that was created a year ago. Since a lot can change in a few years, note the date of your research and look for earlier data sets that can tell you a more recent picture of results. One caveat to this is using data collected over a long-term period for comparisons with earlier periods, which can tell you about the rate and direction of change.

- Can the data sources be verified? Does the information you have check out?

If you can’t verify the data by looking at the research methodology, speaking to the original team or cross-checking the facts with other research, it could be hard to be sure that the data is accurate. Think about whether you can use another source, or if it’s worth doing some supplementary primary research to replicate and verify results to help with this issue.

We created a front-to-back guide on conducting market research, The ultimate guide to conducting market research , so you can understand the research journey with confidence.

In it, you’ll learn more about:

- What effective market research looks like

- The use cases for market research

- The most important steps to conducting market research

- And how to take action on your research findings

Download the free guide for a clearer view on secondary research and other key research types for your business.

Related resources

Market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, qualitative research questions 11 min read, qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

A typology of secondary research in Applied Linguistics

Secondary research is burgeoning in the field of Applied Linguistics, taking the form of both narrative literature review and especially more systematic research synthesis. Clearly purposed and methodologically sound secondary research contributes to the field because it provides useful and reliable summaries in a given domain, facilitates research dialogues between sub-fields, and reduces redundancies in the published literature. It is important to understand that secondary research is an umbrella term that includes numerous types of literature review. In this commentary, we present a typology of 13 types of well-established and emergent types of secondary research in Applied Linguistics. Employing a four-dimensional analytical framework, focus, review process, structure, and representation of text of the 13 types of secondary research are discussed, supported by examples. This article ends with recommendations for conducting secondary research and calls for further inquiry into field-specific methodology of secondary research.

1 Secondary research in Applied Linguistics: commentary or research?

Secondary research, or literature review, refers to a scholarly review of a body of literature on a selected topic ( Ellis 2015 ). In the field of Applied Linguistics, and elsewhere in the social and natural sciences, there are two main types of secondary research: traditional and systematic ( Norris and Ortega 2007 ). Traditional (i.e., narrative-based) reviews bring together findings on the topic under investigation while providing a connection between the reported research and the macroscopic research terrain. While traditional reviews are often composed in a manner which aims to “tell a story” ( Norris and Ortega 2006 , p. 5), they also tend to include a critique of the literature at hand (an alternative name of some traditional reviews is “ critical reviews ”). This is especially true in traditional reviews which are published as stand-alone journal articles in which researchers identify strengths and weaknesses of existing studies on a topic. Unlike systematic reviews, traditional reviews do not generally extract data in any formalized way from primary studies. Finally, such reviews usually also make suggestions for future research directions based on the reviewers’ expert knowledge and/or based on gaps identified in the literature.

The other main family of secondary research is best characterized by a formal set of methods that are applied to the review process. Such ‘systematic reviews’, or research syntheses, have gained widespread popularity in Applied Linguistics research in recent years, especially those that aggregate quantitative findings ( Chong et al. 2023 ). In addition to systematic reviews, a growing body of papers concerning their methodology can also be found (e.g., Chong and Plonsky 2021 ; Chong and Reinders 2021 ; Chong and Reinders 2022 ; Li and Wang 2018 ; Macaro 2020 ; Norris and Ortega 2006 ; Plonsky and Brown 2015 ; Plonsky and Oswald 2015 ) and several new contributions are underway (e.g., Norris and Plonsky In Preparation ; Sterling and Plonsky In Preparation ). Indeed, Norris and Ortega’s (2007) prediction that research syntheses “will continue to thrive in our field” (p. 812) has been borne out. Unlike traditional or narrative reviews, systematic research syntheses refer to a “protocol-driven and quality-focused approach” ( Bearman et al. 2012 , p. 625) to aggregate research evidence to enlighten theory, research, policy, and practice.

In parallel to primary research, systematic research syntheses can be broadly divided into two major types: qualitative and quantitative . Qualitative research synthesis, also called “qualitative evidence synthesis” (e.g., Chong and Reinders 2020 ), assembles qualitative research evidence to “reveal deep insights into disparate literature for future research” ( Chen 2016 , p. 387). Another purpose of qualitative research synthesis is to strengthen and deepen qualitative evidence by unraveling “multidimensions, varieties, and complexities” ( Çiftçi and Savas 2017 , p. 4) amongst studies.

Quantitative research syntheses, as the name indicates, rely on quantitative data as a means to understand a given domain. The most well-known synthesis of this type is likely meta-analysis, which involves the statistical aggregation of effect sizes across studies (e.g., In’nami and Kozumi 2009 ). However, a number of other types of quantitative syntheses exist such as bibliometric reviews (see below). Figure 1 presents a visual of the basic breakdown of secondary research types introduced thus far.

Major types of secondary research.

Whilst traditional literature reviews continue to appear in Applied Linguistics journals and other outlets such as book chapters and monographs, systematic research syntheses are gaining prominence. Such growth can be attributed to several factors. First, the status of research synthesis has changed in recent years from a kind of ‘state-of-the-art’ think piece or commentary to a valuable form of empirical research necessary to consolidate and advance understanding of a given domain. To be sure, the systematicity, rigor, and transparency associated with research syntheses has greatly diminished the presence of bias and allowed for greater trust to be placed in secondary results. Secondly, reviews are no longer only produced by senior scholars who offer their authoritative opinions but also by more junior scholars as well as by synthesists working alongside researchers who specialize in the topic of the review (e.g., Visonà and Plonsky 2020 ). Such collaborations between experts in the substantive domain, on one hand, and in research syntheses on the other, bring a powerful synergy to the task of systematically reviewing a given body of work. A third reason for growth in the prominence of research synthesis is its place as “a cornerstone of the evidence-based practice and policy movement” ( Dixon-Woods et al. 2007 , p. 375) in education, medicine, and many other applied fields. Fourth, systematic research syntheses facilitate “epistemological diversity” ( Norris and Ortega 2007 , p. 813). Through more systematic and comprehensive literature searches (see Plonsky and Brown 2015 ), systematic research syntheses give voice to research findings published not only in prominent journals (mostly published in English) but also local and regional journals as well as other less visible yet valuable sources, such as masters and doctoral theses.

Despite the growth and prominence of secondary research, we have noticed a lack of consistency in naming conventions in the synthetic literature in applied linguistics as well as in other disciplines (e.g., Sutton et al. 2019 ). More importantly, underlying this inconsistency appears to be a misunderstanding of the different approaches to synthesis and their corresponding techniques and goals. One outcome of such inconsistency is confusion among authors, reviewers, editors, and readers ( Chong et al. 2022 ). Perhaps more serious is the implicit message sent to readers regarding this type of work that almost anything goes and by any name. Consequently, we see an urgent need to clarify not only the labels but the characteristics and accepted norms for conducting systematic research syntheses in Applied Linguistics.

2 A typology of secondary research in Applied Linguistics

In the previous section, we established that secondary research in Applied Linguistics has experienced a shift from the narrative tradition to a more systematic, empirical approach. While the development of systematic research synthesis is gaining momentum, it is unlikely that traditional literature reviews will be replaced entirely. Rather, in our view, it benefits the whole research field that the two families of secondary research co-exist, serving different purposes to advance our understanding. With this in mind, and to provide structure and guidance to future synthetic efforts, we address the following question in the remainder of this paper: “ What are the different types of secondary research in Applied Linguistics ?”

A number of taxonomies or typologies have been proposed to standardise conventions and practices of secondary research, for example, in healthcare ( Grant and Booth 2009 ), health sciences ( Littell 2018 ), medical sciences ( Munn et al. 2018 ), and social sciences ( Cooper 1988 ). With the proliferation of secondary research in Applied Linguistics in recent years, we believe the development of a field-specific typology is necessary. At the outset, however, a few disclaimers are warranted. Firstly, this typology is not a result of a comprehensive and fully systematic literature search, although considerations were given as to what reviews to include as examples in the typology (see below). Secondly, given the nature of this article (which is a commentary), analysis of the included reviews will indubitably represent, to a certain extent, our own views, biases, and experiences as primary and secondary/synthetic researchers. Thirdly, this typology is not to be seen as conclusive or definitive. Owing to the dynamic development of secondary research in Applied Linguistics, we regard this typology as a work in progress and invite contributions and revisions which build upon it. Finally, the purpose of presenting this preliminary typology is not to prescribe best practices in secondary research. Rather, we hope but to offer an overview of this versatile and emergent set of methodological techniques as a means to standardize some of the naming and methodological conventions being employed. We also seek to expose the field to some of the potential approaches to and outcomes of secondary research that might otherwise be unfamiliar or overlooked.