How to Write a Memoir: Examples and a Step-by-Step Guide

Zining Mok | January 29, 2024 | 25 Comments

If you’ve thought about putting your life to the page, you may have wondered how to write a memoir. We start the road to writing a memoir when we realize that a story in our lives demands to be told. As Maya Angelou once wrote, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.”

How to write a memoir? At first glance, it looks easy enough—easier, in any case, than writing fiction. After all, there is no need to make up a story or characters, and the protagonist is none other than you.

Still, memoir writing carries its own unique challenges, as well as unique possibilities that only come from telling your own true story. Let’s dive into how to write a memoir by looking closely at the craft of memoir writing, starting with a key question: exactly what is a memoir?

How to Write a Memoir: Contents

What is a Memoir?

- Memoir vs Autobiography

Memoir Examples

Short memoir examples.

- How to Write a Memoir: A Step-by-Step Guide

A memoir is a branch of creative nonfiction , a genre defined by the writer Lee Gutkind as “true stories, well told.” The etymology of the word “memoir,” which comes to us from the French, tells us of the human urge to put experience to paper, to remember. Indeed, a memoir is “ something written to be kept in mind .”

A memoir is defined by Lee Gutkind as “true stories, well told.”

For a piece of writing to be called a memoir, it has to be:

- Nonfictional

- Based on the raw material of your life and your memories

- Written from your personal perspective

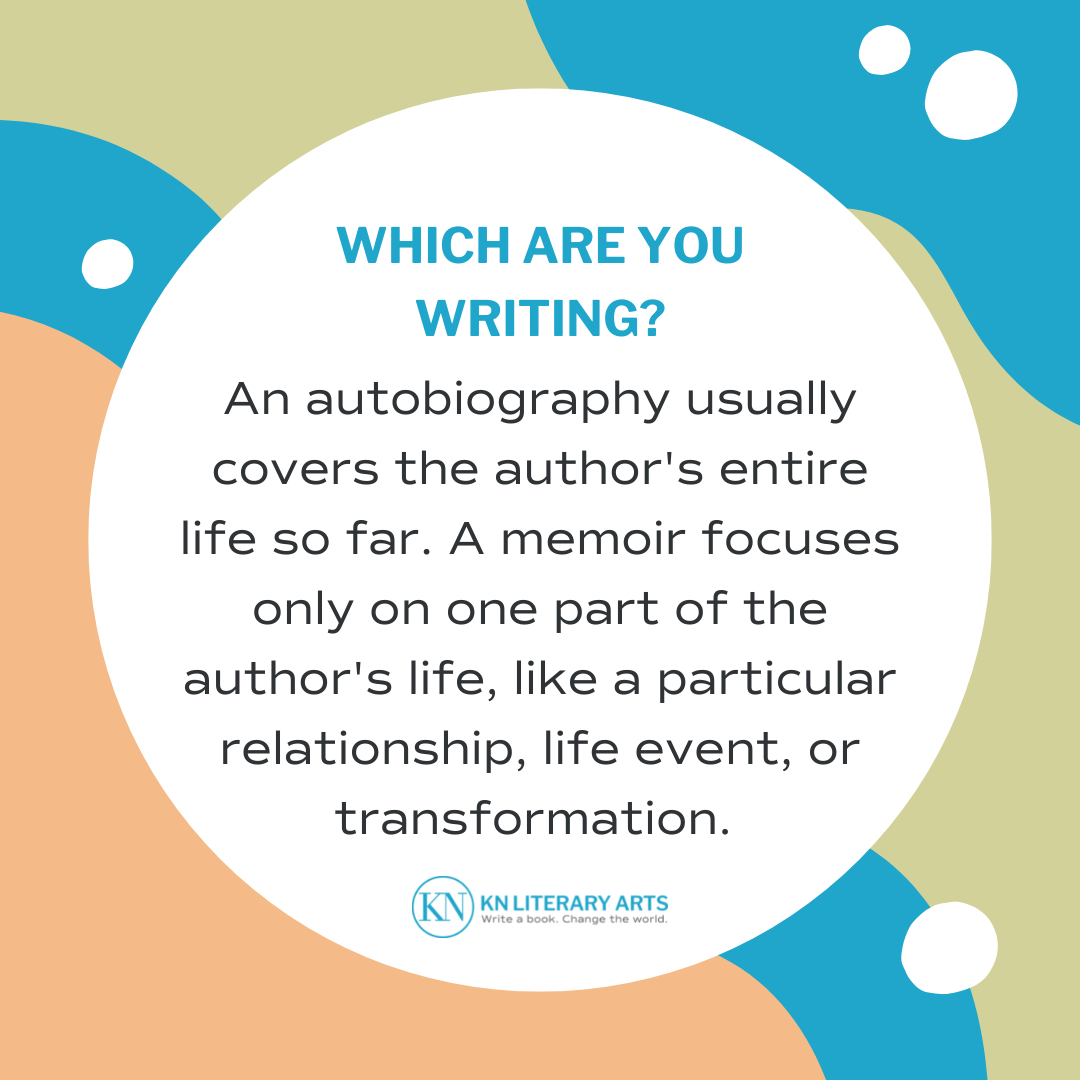

At this point, memoirs are beginning to sound an awful lot like autobiographies. However, a quick comparison of Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love , and The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin , for example, tells us that memoirs and autobiographies could not be more distinct.

Next, let’s look at the characteristics of a memoir and what sets memoirs and autobiographies apart. Discussing memoir vs. autobiography will not only reveal crucial insights into the process of writing a memoir, but also help us to refine our answer to the question, “What is a memoir?”

Memoir vs. Autobiography

While both use personal life as writing material, there are five key differences between memoir and autobiography:

1. Structure

Since autobiographies tell the comprehensive story of one’s life, they are more or less chronological. writing a memoir, however, involves carefully curating a list of personal experiences to serve a larger idea or story, such as grief, coming-of-age, and self-discovery. As such, memoirs do not have to unfold in chronological order.

While autobiographies attempt to provide a comprehensive account, memoirs focus only on specific periods in the writer’s life. The difference between autobiographies and memoirs can be likened to that between a CV and a one-page resume, which includes only select experiences.

The difference between autobiographies and memoirs can be likened to that between a CV and a one-page resume, which includes only select experiences.

Autobiographies prioritize events; memoirs prioritize the writer’s personal experience of those events. Experience includes not just the event you might have undergone, but also your feelings, thoughts, and reflections. Memoir’s insistence on experience allows the writer to go beyond the expectations of formal writing. This means that memoirists can also use fiction-writing techniques , such as scene-setting and dialogue , to capture their stories with flair.

4. Philosophy

Another key difference between the two genres stems from the autobiography’s emphasis on facts and the memoir’s reliance on memory. Due to memory’s unreliability, memoirs ask the reader to focus less on facts and more on emotional truth. In addition, memoir writers often work the fallibility of memory into the narrative itself by directly questioning the accuracy of their own memories.

Memoirs ask the reader to focus less on facts and more on emotional truth.

5. Audience

While readers pick up autobiographies to learn about prominent individuals, they read memoirs to experience a story built around specific themes . Memoirs, as such, tend to be more relatable, personal, and intimate. Really, what this means is that memoirs can be written by anybody!

Ready to be inspired yet? Let’s now turn to some memoir examples that have received widespread recognition and captured our imaginations!

If you’re looking to lose yourself in a book, the following memoir examples are great places to begin:

- The Year of Magical Thinking , which chronicles Joan Didion’s year of mourning her husband’s death, is certainly one of the most powerful books on grief. Written in two short months, Didion’s prose is urgent yet lucid, compelling from the first page to the last. A few years later, the writer would publish Blue Nights , another devastating account of grief, only this time she would be mourning her daughter.

- Patti Smith’s Just Kids is a classic coming-of-age memoir that follows the author’s move to New York and her romance and friendship with the artist Robert Maplethorpe. In its pages, Smith captures the energy of downtown New York in the late sixties and seventies effortlessly.

- When Breath Becomes Air begins when Paul Kalanithi, a young neurosurgeon, is diagnosed with terminal cancer. Exquisite and poignant, this memoir grapples with some of the most difficult human experiences, including fatherhood, mortality, and the search for meaning.

- A memoir of relationship abuse, Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House is candid and innovative in form. Machado writes about thorny and turbulent subjects with clarity, even wit. While intensely personal, In the Dream House is also one of most insightful pieces of cultural criticism.

- Twenty-five years after leaving for Canada, Michael Ondaatje returns to his native Sri Lanka to sort out his family’s past. The result is Running in the Family , the writer’s dazzling attempt to reconstruct fragments of experiences and family legends into a portrait of his parents’ and grandparents’ lives. (Importantly, Running in the Family was sold to readers as a fictional memoir; its explicit acknowledgement of fictionalization prevented it from encountering the kind of backlash that James Frey would receive for fabricating key facts in A Million Little Pieces , which he had sold as a memoir . )

- Of the many memoirs published in recent years, Tara Westover’s Educated is perhaps one of the most internationally-recognized. A story about the struggle for self-determination, Educated recounts the writer’s childhood in a survivalist family and her subsequent attempts to make a life for herself. All in all, powerful, thought-provoking, and near impossible to put down.

While book-length memoirs are engaging reads, the prospect of writing a whole book can be intimidating. Fortunately, there are plenty of short, essay-length memoir examples that are just as compelling.

While memoirists often write book-length works, you might also consider writing a memoir that’s essay-length. Here are some short memoir examples that tell complete, lived stories, in far fewer words:

- “ The Book of My Life ” offers a portrait of a professor that the writer, Aleksandar Hemon, once had as a child in communist Sarajevo. This memoir was collected into Hemon’s The Book of My Lives , a collection of essays about the writer’s personal history in wartime Yugoslavia and subsequent move to the US.

- “The first time I cheated on my husband, my mother had been dead for exactly one week.” So begins Cheryl Strayed’s “ The Love of My Life ,” an essay that the writer eventually expanded into the best-selling memoir, Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail .

- In “ What We Hunger For ,” Roxane Gay weaves personal experience and a discussion of The Hunger Games into a powerful meditation on strength, trauma, and hope. “What We Hunger For” can also be found in Gay’s essay collection, Bad Feminist .

- A humorous memoir structured around David Sedaris and his family’s memories of pets, “ The Youth in Asia ” is ultimately a story about grief, mortality and loss. This essay is excerpted from the memoir Me Talk Pretty One Day , and a recorded version can be found here .

So far, we’ve 1) answered the question “What is a memoir?” 2) discussed differences between memoirs vs. autobiographies, 3) taken a closer look at book- and essay-length memoir examples. Next, we’ll turn the question of how to write a memoir.

How to Write a Memoir: A-Step-by-Step Guide

1. how to write a memoir: generate memoir ideas.

how to start a memoir? As with anything, starting is the hardest. If you’ve yet to decide what to write about, check out the “ I Remember ” writing prompt. Inspired by Joe Brainard’s memoir I Remember , this prompt is a great way to generate a list of memories. From there, choose one memory that feels the most emotionally charged and begin writing your memoir. It’s that simple! If you’re in need of more prompts, our Facebook group is also a great resource.

2. How to Write a Memoir: Begin drafting

My most effective advice is to resist the urge to start from “the beginning.” Instead, begin with the event that you can’t stop thinking about, or with the detail that, for some reason, just sticks. The key to drafting is gaining momentum . Beginning with an emotionally charged event or detail gives us the drive we need to start writing.

3. How to Write a Memoir: Aim for a “ shitty first draft ”

Now that you have momentum, maintain it. Attempting to perfect your language as you draft makes it difficult to maintain our impulses to write. It can also create self-doubt and writers’ block. Remember that most, if not all, writers, no matter how famous, write shitty first drafts.

Attempting to perfect your language as you draft makes it difficult to maintain our impulses to write.

4. How to Write a Memoir: Set your draft aside

Once you have a first draft, set it aside and fight the urge to read it for at least a week. Stephen King recommends sticking first drafts in your drawer for at least six weeks. This period allows writers to develop the critical distance we need to revise and edit the draft that we’ve worked so hard to write.

5. How to Write a Memoir: Reread your draft

While reading your draft, note what works and what doesn’t, then make a revision plan. While rereading, ask yourself:

- What’s underdeveloped, and what’s superfluous.

- Does the structure work?

- What story are you telling?

6. How to Write a Memoir: Revise your memoir and repeat steps 4 & 5 until satisfied

Every piece of good writing is the product of a series of rigorous revisions. Depending on what kind of writer you are and how you define a draft,” you may need three, seven, or perhaps even ten drafts. There’s no “magic number” of drafts to aim for, so trust your intuition. Many writers say that a story is never, truly done; there only comes a point when they’re finished with it. If you find yourself stuck in the revision process, get a fresh pair of eyes to look at your writing.

7. How to Write a Memoir: Edit, edit, edit!

Once you’re satisfied with the story, begin to edit the finer things (e.g. language, metaphor , and details). Clean up your word choice and omit needless words , and check to make sure you haven’t made any of these common writing mistakes . Be sure to also know the difference between revising and editing —you’ll be doing both. Then, once your memoir is ready, send it out !

Learn How to Write a Memoir at Writers.com

Writing a memoir for the first time can be intimidating. But, keep in mind that anyone can learn how to write a memoir. Trust the value of your own experiences: it’s not about the stories you tell, but how you tell them. Most importantly, don’t give up!

Anyone can learn how to write a memoir.

If you’re looking for additional feedback, as well as additional instruction on how to write a memoir, check out our schedule of nonfiction classes . Now, get started writing your memoir!

25 Comments

Thank you for this website. It’s very engaging. I have been writing a memoir for over three years, somewhat haphazardly, based on the first half of my life and its encounters with ignorance (religious restrictions, alcohol, and inability to reach out for help). Three cities were involved: Boston as a youngster growing up and going to college, then Washington DC and Chicago North Shore as a married woman with four children. I am satisfied with some chapters and not with others. Editing exposes repetition and hopefully discards boring excess. Reaching for something better is always worth the struggle. I am 90, continue to be a recital pianist, a portrait painter, and a writer. Hubby has been dead for nine years. Together we lept a few of life’s chasms and I still miss him. But so far, my occupations keep my brain working fairly well, especially since I don’t smoke or drink (for the past 50 years).

Hi Mary Ellen,

It sounds like a fantastic life for a memoir! Thank you for sharing, and best of luck finishing your book. Let us know when it’s published!

Best, The writers.com Team

Hello Mary Ellen,

I am contacting you because your last name (Lavelle) is my middle name!

Being interested in genealogy I have learned that this was my great grandfathers wife’s name (Mary Lavelle), and that her family emigrated here about 1850 from County Mayo, Ireland. That is also where my fathers family came from.

Is your family background similar?

Hope to hear back from you.

Richard Lavelle Bourke

Hi Mary Ellen: Have you finished your memoir yet? I just came across your post and am seriously impressed that you are still writing. I discovered it again at age 77 and don’t know what I would do with myself if I couldn’t write. All the best to you!! Sharon [email protected]

I am up to my eyeballs with a research project and report for a non-profit. And some paid research for an international organization. But as today is my 90th birthday, it is time to retire and write a memoir.

So I would like to join a list to keep track of future courses related to memoir / creative non-fiction writing.

Hi Frederick,

Happy birthday! And happy retirement as well. I’ve added your name and email to our reminder list for memoir courses–when we post one on our calendar, we’ll send you an email.

We’ll be posting more memoir courses in the near future, likely for the months of January and February 2022. We hope to see you in one!

Very interesting and informative, I am writing memoirs from my long often adventurous and well travelled life, have had one very short story published. Your advice on several topics will be extremely helpful. I write under my schoolboy nickname Barnaby Rudge.

[…] How to Write a Memoir: Examples and a Step-by-Step Guide […]

I am writing my memoir from my memory when I was 5 years old and now having left my birthplace I left after graduation as a doctor I moved to UK where I have been living. In between I have spent 1 year in Canada during my training year as paediatrician. I also spent nearly 2 years with British Army in the hospital as paediatrician in Germany. I moved back to UK to work as specialist paediatrician in a very busy general hospital outside London for the next 22 years. Then I retired from NHS in 2012. I worked another 5 years in Canada until 2018. I am fully retired now

I have the whole convoluted story of my loss and horrid aftermath in my head (and heart) but have no clue WHERE, in my story to begin. In the middle of the tragedy? What led up to it? Where my life is now, post-loss, and then write back and forth? Any suggestions?

My friend Laura who referred me to this site said “Start”! I say to you “Start”!

Hi Dee, that has been a challenge for me.i dont know where to start?

What was the most painful? Embarrassing? Delicious? Unexpected? Who helped you? Who hurt you? Pick one story and let that lead you to others.

I really enjoyed this writing about memoir. I ve just finished my own about my journey out of my city then out of my country to Egypt to study, Never Say Can’t, God Can Do It. Infact memoir writing helps to live the life you are writing about again and to appreciate good people you came across during the journey. Many thanks for sharing what memoir is about.

I am a survivor of gun violence, having witnessed my adult son being shot 13 times by police in 2014. I have struggled with writing my memoir because I have a grandson who was 18-months old at the time of the tragedy and was also present, as was his biological mother and other family members. We all struggle with PTSD because of this atrocity. My grandson’s biological mother was instrumental in what happened and I am struggling to write the story in such a way as to not cast blame – thus my dilemma in writing the memoir. My grandson was later adopted by a local family in an open adoption and is still a big part of my life. I have considered just writing it and waiting until my grandson is old enough to understand all the family dynamics that were involved. Any advice on how I might handle this challenge in writing would be much appreciated.

I decided to use a ghost writer, and I’m only part way in the process and it’s worth every penny!

Hi. I am 44 years old and have had a roller coaster life .. right as a young kid seeing his father struggle to financial hassles, facing legal battles at a young age and then health issues leading to a recent kidney transplant. I have been working on writing a memoir sharing my life story and titled it “A memoir of growth and gratitude” Is it a good idea to write a memoir and share my story with the world?

Thank you… this was very helpful. I’m writing about the troubling issues of my mental health, and how my life was seriously impacted by that. I am 68 years old.

[…] Writers.com: How to Write a Memoir […]

[…] Writers.com: “How to Write a Memoir” […]

I am so grateful that I found this site! I am inspired and encouraged to start my memoir because of the site’s content and the brave people that have posted in the comments.

Finding this site is going into my gratitude journey 🙂

We’re grateful you found us too, Nichol! 🙂

Firstly, I would like to thank you for all the info pertaining to memoirs. I believe am on the right track, am at the editing stage and really have to use an extra pair of eyes. I’m more motivated now to push it out and complete it. Thanks for the tips it was very helpful, I have a little more confidence it seeing the completion.

Well, I’m super excited to begin my memoir. It’s hard trying to rely on memories alone, but I’m going to give it a shot!

Thanks to everyone who posted comments, all of which have inspired me to get on it.

Best of luck to everyone! Jody V.

I was thrilled to find this material on How to Write A Memoir. When I briefly told someone about some of my past experiences and how I came to the United States in the company of my younger brother in a program with a curious name, I was encouraged by that person and others to write my life history.

Based on the name of that curious program through which our parents sent us to the United States so we could leave the place of our birth, and be away from potentially difficult situations in our country.

As I began to write my history I took as much time as possible to describe all the different steps that were taken. At this time – I have been working on this project for 5 years and am still moving ahead. The information I received through your material has further encouraged me to move along. I am very pleased to have found this important material. Thank you!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of memoir

Examples of memoir in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'memoir.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Middle French memoire , from memoire memory, from Latin memoria

1571, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Dictionary Entries Near memoir

memorabilia

Cite this Entry

“Memoir.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/memoir. Accessed 4 Apr. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of memoir, more from merriam-webster on memoir.

Nglish: Translation of memoir for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of memoir for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about memoir

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

The tangled history of 'it's' and 'its', more commonly misspelled words, why does english have so many silent letters, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - mar. 29, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

What Is a Memoir?

More focused than an autobiography, a memoir is an intimate look at a moment in time.

By Jessica Dukes

The memoir genre satisfies two of our most human desires: to be known, and to know others. Here’s how we define memoir, its history and types, and how to get started writing your own.

"Memoir" Definition

A memoir is a narrative, written from the perspective of the author, about an important part of their life. It’s often conflated with autobiography, but there are a few important differences. An autobiography is also written from the author’s perspective, but the narrative spans their entire life. Although it’s subjective, it primarily focuses on facts – the who-what-when-where-why-how of their life’s entire timeline. Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery is an example of autobiography – the story begins with his childhood as a slave, proceeds through his emancipation and education, and ends in his present life as an entrepreneur.

To define memoir, we loosen the constraints of an autobiography. Memoir authors choose a pivotal moment in their lives and try to recreate the event through storytelling. The author’s feelings and assumptions are central to the narrative. Memoirs still include all the facts of the event, but the author has more flexibility here because she is telling a story as she remembers it, not as others can prove or disprove it. (In fact, “memoir” comes from the French “mémoire” or “memory.”) In Night , the Nobel Prize-winning title, Elie Wiesel tells his own story about one period of his life – how he survived his teenage years at Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

History of the Memoir

In A.D. 397, St. Augustine of Hippo began writing The Confessions of Saint Augustine , telling the world of his sins: “It was foul, and I loved it. I loved my own undoing.” Ever since, we’ve been hooked on the idea that we can get to know a stranger so intimately, even (and especially) a famous one. Although Confessions is technically an autobiography in structure, the intimacy of his narrative was a new phenomenon. From there, we can draw a straight line to all memoirs that followed.

Like a family tree, once a memoir type emerges, it gives rise to a number of sub-categories. In his book, Memoir: A History , Ben Yagoda gives a string of examples connecting Augustine’s Confessions to the modern success of spiritual memoirs. Thus, Anne Lamott’s Traveling Mercies: Some Thoughts on Faith and Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love are a part of a long literary tradition. In turn, the success of books like Eat Pray Love fuels the demand for other “schtick lit” titles like The Happiness Project by Gretchen Rubin and Julie & Julia: My Year of Cooking Dangerously by Julie Powell. Also, let’s note that Julie & Julia/i> follows the long tradition of “My year of…” memoirs, which includes beloved titles like Henry David Thoreau’s Walden .

Types of Memoir

There is no finite number of memoir sub-categories, just as there are no finite types of experiences we have as thinking, feeling human beings. So, what does memoir mean today? Most of them fall into several large types, but with a definite chance of overlap.

Transformation memoirs are written after an author has endured a great challenge. These stories almost always include a theme of redemption, whether it’s achieved or missing. For example:

In Finding Freedom , Erin French first discovers her love for cooking as a young girl in her father’s diner in Freedom, Maine. But in early adulthood, she struggles through prescription drug addiction, a daunting custody battle for her son, and multiple rock-bottoms, until she ultimately finds renewal through her community and love for food, opening the critically acclaimed restaurant The Lost Kitchen.

Here We Are: American Dreams, American Nightmares is Aarti Namdev Shahani’s family immigrant story, of how an unknown dealing with a drug cartel led to her father being sent to Rikers Island, and a study in how difficult it is to make it in America.

Educated is Tara Westover’s incredible account of how she overcame a childhood spent in survivalist camps in rural Idaho and worked her way into Harvard and Cambridge universities.

Confessional memoirs are unapologetically bold. The author shares painful or difficult secrets about themselves or their family and how it has affected them. For example:

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Confessions shocked readers in that it was a secular coming-of-age story, and because it contained unexpected details of his life, like his sexual preferences.

Running with Scissors is Augusten Burroughs’ childhood laid bare. His mother left him to be raised by her psychiatrist who lived in squalor, never sent him to school, and never protected him from the pedophile living in the back yard.

Professional or celebrity memoirs cover important moments in the author’s rise to fame and success. Some examples include:

I Am Malala by Malala Yousafzai details her horrible attack by the Taliban, her recovery, and her decision to fight for girls’ education worldwide.

Just Kids by Patti Smith is a beautiful recollection of her friendship with Robert Mapplethorpe in the years before they became famous.

Travel memoirs let us escape with the author and learn about a time and place through their experiences. For example:

Cheryl Strayed’s Wild takes us on her emotional solo journey along the Pacific Crest Trail as she grieves the loss of her mother and her marriage.

A Year in Provence is Peter Mayle’s heartwarming account of the year that he threw caution to the wind and moved his family into a crumbling, 200-year-old farmhouse in the French countryside.

How to Write a Memoir

Is there a part of your life that is begging to be turned into a story? It might be time for you to write a memoir. Here’s how to get started.

First, choose a pivotal moment in your life. It can be as broad as “my childhood” or as narrow as “that time I went to prison.” (Hey, it worked for Piper Kerman.)

Consider why this time period is important. What struggles did you endure? What lessons did you learn? What universal truths will capture a reader’s imagination?

Start gathering your memories, as many as you can. List the people you experienced this moment in time with, how they looked, and the conversations you had with them. Capture your feelings about every event and don’t hold back. The best memoirs bare it all.

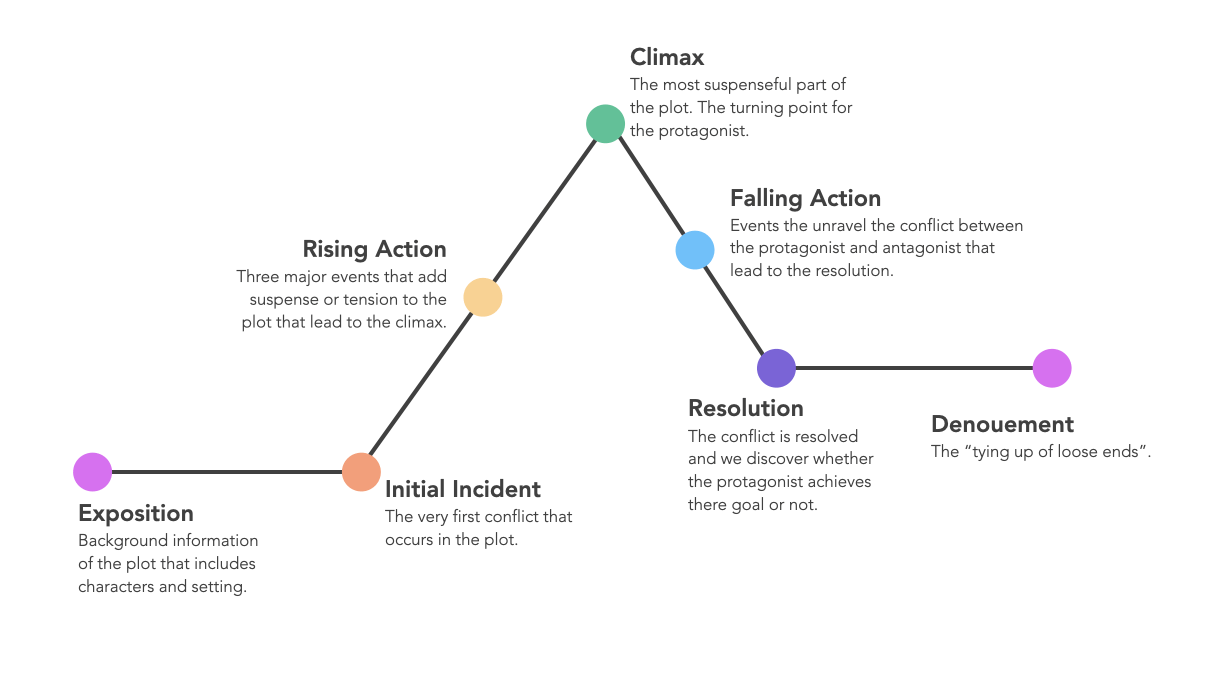

Now, structure your memoir like a novel. There should be a clear story arc. The retelling of your memories should include descriptions of settings, and three-dimensional characters that readers will care about. Recreate dialogue as faithfully as you can.

Ultimately, readers want to know “how.” How did you survive this situation? How are you now? Most importantly, how have you changed? If memoirs have one thing in common, it’s an author who shares the lessons of his or her life for the greater good of all.

Share with your friends

Related articles.

11 Page-Turning Mysteries and Thrillers Set on Remote Islands

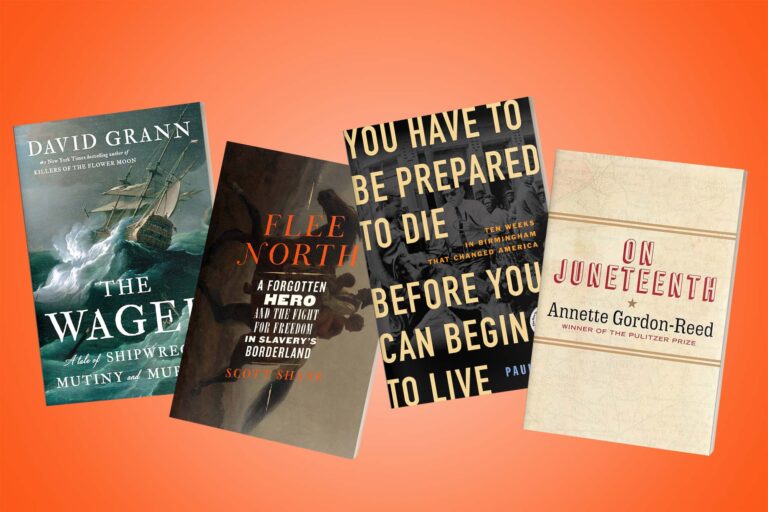

11 Riveting Next Reads for Your History Book Club

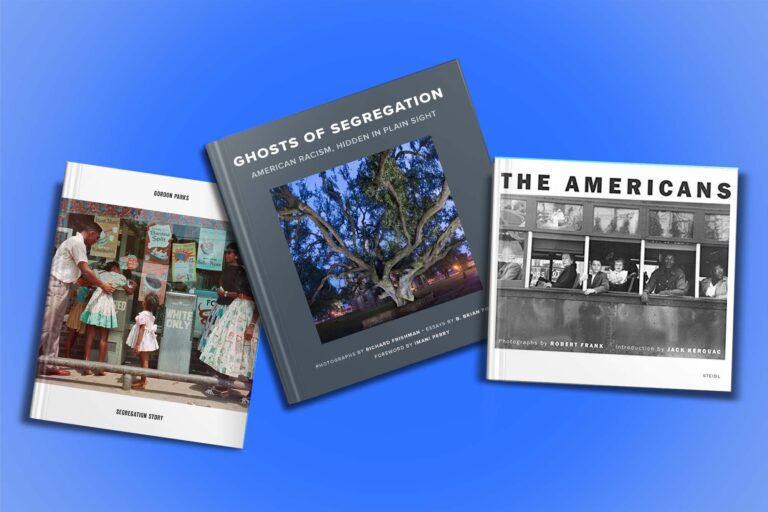

10 Eye-Opening Photography Books About America

Celadon delivered.

Subscribe to get articles about writing, adding to your TBR pile, and simply content we feel is worth sharing. And yes, also sign up to be the first to hear about giveaways, our acquisitions, and exclusives!

" * " indicates required fields

Connect with

Sign up for our newsletter to see book giveaways, news, and more.

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

A memoir is a form of creative nonfiction in which an author recounts experiences from his or her life. Memoirs usually take the form of a narrative ,

The terms memoir and autobiography are commonly used interchangeably, and the distinction between these two genres is often blurred. In the Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms , Murfin and Ray say that memoirs differ from autobiographies in "their degree of outward focus. While [memoirs] can be considered a form of autobiographical writing, their personalized accounts tend to focus more on what the writer has witnessed than on his or her own life, character, and developing self." In his own first volume of memoirs, Palimpsest (1995), Gore Vidal makes a different distinction. "A memoir," he says, "is how one remembers one's own life, while an autobiography is history, requiring research , dates, facts double-checked. In a memoir it isn't the end of the world if your memory tricks you and your dates are off by a week or a month as long as you honestly try to tell the truth" ( Palimpsest: A Memoir , 1995).

"The one clear difference," says Ben Yagoda, "is that while 'autobiography' or 'memoirs' usually cover the full span of [a] life, 'memoir' has been used by books that cover the entirety or some portion of it" ( Memoir: A History, 2009).

See Examples and Observations below. Also see:

- Autobiography

- Eudora Welty's Sketch of Miss Duling

- Family Sketches in Kate Simon's "Bronx Primitive"

- First-Person Point of View

- Harry Crews's Sketch of His Stepfather

- Hypotaxis in James Baldwin's "Notes of a Native Son"

- Letting Go by Phoebe Yates Pember

- Literary Nonfiction

- Pete Hamill on Stickball in New York

Etymology From the Latin, "memory"

Examples and Observations

- "[O]nce you begin to write the true story of your life in a form that anyone would possibly want to read, you start to make compromises with the truth." (Ben Yagoda, Memoir: A History . Riverhead, 2009)

- Zinsser on the Art and Craft of Memoir "A good memoir requires two elements—one of art, the other of craft. The first is integrity of intention. . . . Memoir is how we try to make sense of who we are, who we once were, and what values and heritage shaped us. If a writer seriously embarks on that quest, readers will be nourished by the journey, bringing along many associations with quests of their own. "The other element is carpentry. Good memoirs are a careful act of construction. We like to think that an interesting life will simply fall into place on the page. It won't. . . . Memoir writers must manufacture a text, imposing narrative order on a jumble of half-remembered events." (William Zinsser, "Introduction." Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir . Mariner, 1998)

- Rules for the Memoirist "Here are some basic rules of good behavior for the memoirist : - Say difficult things. Including difficult facts. - Be harder on yourself than you are on others. The Golden Rule isn't much use in memoir. Inevitably you will not portray others just as they would like to be portrayed. But you can at least remember that the game is rigged: only you are playing voluntarily. - Try to accept the fact that you are, in company with everybody else, in part a comic figure. - Stick to the facts." (Tracy Kidder and Richard Todd, Good Prose: The Art of Nonfiction . Random House, 2013)

- Memoir and Memoirs "Like many people today, I confused 'the memoir' with 'memoirs.' It was easy to do back then, when the literary memoir was not basking in the popularity it currently enjoys. The term memoirs was used to describe something closer to autobiography than the essay -like literary memoir. These famous person memoirs rarely stuck to one theme or selected out one aspect of a life to explore in depth, as the memoir does. More often, 'memoirs' (always preceded by a possessive pronoun : 'my memoirs,' 'his memoirs') were a kind of scrapbook in which pieces of a life were pasted. Of course, the boundary between these genres was not—and still is not—as clearly delineated as I have made it sound." (Judith Barrington, Writing the Memoir: From Truth to Art , 2nd ed. Eighth Mountain, 2002)

- Roger Ebert on the Stream of Writing "The British satirist Auberon Waugh once wrote a letter to the editor of the Daily Telegraph asking readers to supply information about his life between birth and the present, explaining that he was writing his memoirs and had no memories from those years. I find myself in the opposite position. I remember everything. All my life I've been visited by unexpected flashes of memory unrelated to anything taking place at the moment. . . . When I began writing this book, memories came flooding to the surface, not because of any conscious effort but simply in the stream of writing. I started in a direction and the memories were waiting there, sometimes of things I hadn't consciously thought about since. . . . In doing something I enjoy and am expert at, deliberate thought falls aside and it is all just there . I think of the next word no more than the composer thinks of the next note." (Roger Ebert, Life Itself: A Memoir . Grand Central Publishing, 2011)

- Fred Exley's "Note to the Reader" in A Fan's Notes : A Fictional Memoir "Though the events in this book bear similarity to those of that long malaise, my life, many of the characters and happenings are creations solely of the imagination. . . . In creating such characters, I have drawn freely from the imagination and adhered only loosely to the pattern of my past life. To this extent, and for this reason, I ask to be judged a writer of fantasy." (Fred Exley, A Fan's Notes: A Fictional Memoir . Harper & Row, 1968)

- The Lighter Side of Memoirs "All those writers who write about their childhood! Gentle God, if I wrote about mine you wouldn't sit in the same room with me." (Dorothy Parker)

Pronunciation: MEM-war

- How to Define Autobiography

- Point of View in Grammar and Composition

- What You Should Know About Travel Writing

- What Are the Different Types and Characteristics of Essays?

- How to Find Trustworthy Sources

- Creative Nonfiction

- What Is Academese?

- Interior Monologues

- Biographies: The Stories of Humanity

- Postscript (P.S.) Definition and Examples in Writing

- 40 Topics to Help With Descriptive Writing Assignments

- Definition and Examples of Paragraphing in Essays

- Defining Nonfiction Writing

- What Is an Autobiography?

- What Is a Graphic Memoir?

- revision (composition)

Looking to publish? Meet your dream editor, designer and marketer on Reedsy.

Find the perfect editor for your next book

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Feb 17, 2023

What is a Memoir? An Inside Look at Life Stories

A memoir is a narrative written from the author's perspective about a particular facet of their own life. As a type of nonfiction , memoirs are generally understood to be factual accounts — though it is accepted that they needn't be objective, merely a version of events as the author remembers them.

The term comes from the French word “mémoire,” which means “memory,” or “reminiscence.” To give you a touchstone before we go any further, here are a couple of famous memoir examples , some of which you might recognize:

- Walden by Henry David Thoreau;

- Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt;

- Becoming by Michelle Obama;

- Eat, Pray, Love by Elizabeth Gilbert; and

- Wild by Cheryl Strayed.

You’d be forgiven for mistaking any of these popular memoirs for a novel — since, just like novels, they have a plot, characters, themes, imagery, and dialogue . We like to think of memoirs as nonfiction by name and fiction by nature.

A quick biography of the memoir

To trace the memoir back to its origins, we’ll need to don our best togas and hitch a chariot ride back to ancient Rome. That’s right, memoirs have been around since at least the first century BC when Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic Wars offered not only a play-by-play of each battle but a peek into the mind of one of Rome’s most dynamic leaders.

“I came, I saw, I conquered, my dudes!”

During the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, memoirs continued to be written by the ruling classes, who interpreted historical events they played a role in or closely observed. The gentry — who had the luxuries of free time, literacy, and spare funds — would document the events and machinations of court, as well as the many military crusades. It was the French who particularly excelled, with diplomats, knights, and historians, such as Philippe de Comminnes and Blaise de Montluc, seizing the opportunity to cement their legacy.

From the 17th century, memoirs began to revolve around people rather than events, though typically, the focus was not on the author’s own life but on the people around him. Once again, the French took the lead — namely, Duc de Saint-Simon, who has received literary fame for his penetrating character sketches of the court of Louis XIV. (Think diary entries packed with petty intrigue and rumor-mongering.)

NEW REEDSY COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Enroll in our course and become an author in three months.

From Julius Caesar to Julia Roberts

As time wore on, this elite posse of memoirists came to include noted professionals, such as politicians and businessmen (it was still always men), who wanted to publish accounts of their own public exploits. The exception to this model was Henry David Thoreau's 1854 memoir Walden — an account of his two years in a Massachusetts cabin, finding fulfillment in the wilderness.

In his book Memoir: A History , Ben Yagoda sketches a family tree pinning Walden as a precursor to the modern success of spiritual and “schtick lit” memoirs like Eat, Pray, Love and Gretchen Ruben’s The Happiness Project , as well as the long literary tradition of “My year of…” memoirs that gave us Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking . Yagoda also traces the roots of these spiritual memoirs back even further to The Confessions of St Augustine written in A.D. 397, in which Augustine admits to a sinful youth spent munching stolen pears ( gasp) before finding the path to Christianity.

“I ate, I prayed, I loved, my dudes!” (image: Sony Pictures)

Yagoda’s point? Once a memoir type emerges, it’ll keep spawning subgenres. For example, traces of the professional memoir and the fragmentary diary can be found in Adam Kay’s medical bestseller This is Going to Hurt. One thing that all memoirs have in common, however, is that they allow us to get to know a stranger on an intimate level — a prospect that appeals to our nosy side and will likely never get old.

MEET GHOSTWRITERS

Find a ghost you can trust

Your mission? A fantastic book. Find the perfect writer to complete it on Reedsy.

Is a memoir the same as an autobiography?

Memoirs and autobiographies are usually found on the same shelves of the bookstore, and so are often conflated in the minds of authors. But we’re here to tell you they’re not the same thing. While both are accounts of the writer's experiences, autobiographies span their entire life, providing the who-what-where-when-why of each stage, in chronological order.

Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom is an example of an autobiography: it details his childhood, his years as a freedom fighter, as well as those spent in prison, and finally, the complex negotiations that led to his release and the beginning of the end of apartheid.

A memoir, on the other hand, is more selective with its timeline. The constraints of the autobiography are loosened, and authors can intimately explore a pivotal moment or a particular facet of their life, allowing their thoughts and feelings to take control of the narrative. For example, journalist Ronan Farrow's Catch and Kill chronicles his investigation leading up to the #MeToo movement, while William Finnegan’s Barbarian Days is a soaring ode to his one great love and obsession — surfing.

Memoir’s emphasis on storytelling is sometimes said to differentiate it from autobiography, but there are much more important differences to be aware of. After all, a good autobiography ought to weave a narrative, too.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

They’re not just for celebrities

These days, most bestselling memoirs tend to be written by celebrities (or their ghostwriters ). Naturally, publishers are keen to capitalize on a well-known person's platform and existing fanbase to sell books — but that doesn't mean you need to be a reality star or a newsmaking criminal to tell your story.

"You have to give people a reason to care about you," says Paul Carr, the author of three published traditionally published memoirs . "They need a reason to relate to your story — for your story to resonate with them."

While most people reading this article are probably not household names, there may be some aspects of your life that can be told in a way that touches on universal human experiences. Or perhaps your story is something that can help people improve their lives in big and small ways.

Even if your memoir doesn't have broad commercial potential, there can be other reasons for writing one:

- To recall and cement the memory of a certain time in your life;

- To leave behind an important story or lesson for your family;

- To document your travels or a once-in-a-lifetime trip;

- To open up about something painful or difficult; or simply,

- To tell a powerful story that will resonate with readers.

If there's someone out there who will benefit from reading your story — whether it's millions of fans or your immediate family — you may find that to be enough of a reason to pick up your pen and start to write.

In the next article in our series about memoirs, we offer up 21 examples of memoirs that might inspire you to write your own.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Structure your memoir for maximum impact

Use our free template to plan an unputdownable memoir.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write Action

I. What is a Memoir?

“Memoir” comes from the French word for memory . It’s a genre of literature where the author writes about his or her memories, usually going back to childhood. Memoirs are typically written by celebrities, world leaders, pro athletes, etc. But anyone can write a memoir, and sometimes they turn out to be great works of literature even when the author hasn’t led a particularly unusual life.

Memoirs usually cover the entire span of the author’s life, but in some cases, they just cover the important parts.

II. Examples and Explanation

Saint Augustine’s Confessions is one of the most influential works of Christian theology, and it’s also a memoir. In the book, Augustine tells the story of his life and of how he found God after spending his youth wallowing in sin. The book has inspired countless people to recommit to their faith, and influenced the Western philosophical understanding of concepts like love, morality, and independence.

Tom Burgenthal, a Holocaust survivor who went on to become a judge on the International Court of Justice, wrote a memoir about his time in Auschwitz. In the book, Burgenthal tells the remarkable story of how he survived the death camp as a ten-year-old boy, and how this experience inspired him to work for the International Court to prevent other children from ever going through such horrors .

III. The Importance of Memoir

A memoir can serve all sorts of functions. The main one, of course, is just to tell a good story. A good memoir, like a good life, can be funny, sad, inspiring, absurd, and deeply relatable. By writing your stories down and figuring out their common themes , you can understand how you got to where you are today. In addition to telling a good story, memoirs can also send many messages:

- They can help support a particular political view (see “Propaganda,” section 6) or inspire the readers to change their view.

- If the public has a negative opinion on the author, writing a memoir can give him a chance to defend himself.

- On the other hand, writing a memoir is an easy way for a famous person to raise their profile and stay in the public eye.

IV. Examples in Literature

Commentaries on the Gallic Wars , by Julius Caesar, is one of the first major works of memoir. In the book, Caesar talks about his experiences fighting in Gaul. This was definitely a propagandistic memoir: Caesar presents himself as a conquering hero triumphantly marching through barbarian lands. This was intended to get people on his side against his enemies – both his external enemies (the Gauls) and the internal enemies who opposed his rise to the throne.

The philosopher Rousseau wrote an incredibly bizarre memoir about his experiences as a young man in France. Rousseau was an eccentric who frequently violated the rules of polite society in pretty extreme ways. Because he was a philosopher, many people expect Rousseau’s memoir to be a dry read, but they’re in for a shock! Some people see this as a kind of philosophical propaganda as well – Rousseau wanted people to disrespect authority and throw away their “civilized” lives in a return to “nature.” His memoir was an example of someone living exactly that way.

V. Examples in Popular Culture

David Sedaris, brother of the actress Amy Sedaris, writes hilarious memoirs about his bizarre family and the experiences he’s been through. His books (with titles like Me Talk Pretty One Day and Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim ) are structured with individual stories rather than a unified flow, but their common elements are humor, cynicism, and the surrealism.

In the comic book Watchmen , one of the major events in the story is when Nite Owl publishes Under the Hood , his memoirs of being a superhero. In the memoirs, Nite Owl reveals some uncomfortable details about his fellow superheroes, and this causes some of the major controversies in the book.

VI. Related Terms (with examples)

- Autobiography

While there are some subtle differences between memoir and autobiography, they’re basically the same thing. In both cases, the author is telling his or her life story, though in the case of a memoir it might be more a collection of isolated incidents, whereas in an autobiography the memories are all united into a single story. In addition, autobiography covers the author’s entire life, while a memoir may only cover one especially important or interesting portion of it.

Propaganda is art or literature with a deliberate political slant. Not all memoirs are propaganda, but many are – they’re written with the intent of getting a particular political message across. For example, when presidents write their memoirs it’s to influence how history will think of them: these authors are trying to persuade the reader that they made the right decision while in office, and so their memoirs have a propagandistic side.

An anecdote is a short story about something that you’ve seen or experienced. A memoir might be described as a collection of anecdotes. However, there are other uses of anecdote, including in essays . An anecdote can help frame your argument or illustrate a particular point. Be careful, though! While anecdotes are useful for illustration, they’re not the same thing as data, and generally should not be used as evidence for what’s happening in society (unless no data is available).

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Definition of Memoir

Memoir is a written factual account of somebody’s life. It comes from the French word mémoire , which means “ memory,” or “reminiscence . ” This literary technique tells a story about the experiences of someone’s life. A literary memoir is usually about a specific theme , or about a part of someone’s life. It is a story with a proper narrative shape, focus, and subject matter, involving reflection on some particular event or place.

Memoirs are often associated with popular personalities, such as celebrities, sportsmen, soldiers, singers, and writers. It allows making a connection with what the audience finds captivating, interesting, appealing, and engaging.

Memoir and Autobiography

Memoir falls under the category of autobiography , but is used as its sub- genre . The major difference between memoir and autobiography is that a memoir is a centralized and more specific storytelling, while an autobiography spans the entire life of a person with intricate details such as the childhood, family history, education, and profession. A memoir is specific and focused, telling the story of somebody’s life, focusing on an important event that occurred at a specific time and place.

Examples of Memoir in Literature

Example #1: a moveable feast (by ernest hemingway).

Ernest Hemingway was an acclaimed celebrity during the times when the public treated American writers like movie stars. His memoir A Moveable Feast was published after his death in 1964. This memoir is a collection of stories about his time spent in Paris as a writer in 1920s, before attaining popularity. During these days, he was acquainted with many other famous writers, including Ezra Pound , F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Gertrude Stein.

Example #2: Speak Memory (By Vladimir Nabokov)

This memoir is about the description of Nabokov’s childhood, and the years he spent before moving to America in 1940; however, it is not the exact reason of writing this memoir. More notably, this book is about a tale of his art, as it serves as a model of that art. In addition, it includes themes, imagery , and symbols that build up a structure in the minds of readers besides making up the book. Like always, Nabokov’s prose writing is flawless, brilliant, and overwhelming, while his playful writing style makes his work seem fascinating.

Example #3: Homage to Catalonia (By George Orwell)

This is Orwell’s gripping tale of his days during the Spanish Civil War. He has described it with his typical trademark of journalistic wink, which is one of his best works. Honest and unwavering, Orwell narrates his personal experience without inducing any agenda, recording different things from that era as he saw them. Philip Mairet said of this account that the work shows ]people a heart of innocence living in revolutionary days.

Example #4: Maus (By Art Spiegelman)

Although we can find many deeply affecting memoirs to make this list, Maus is one of the most well-liked memoirs, with its distressing story covered with perfect illustrations by Spiegelman. We might think that imagining different characters appearing with animal faces would make the story horrible and less intense and more irritating, it is rather the opposite. If we know the comic style, we learn that blank iconic faces and the outlook of the mice in this memoir allows the audience to put themselves in their shoes, to understand the story more easily.

Function of Memoir

Memoir has been around since ancient times. Perhaps Julius Caesar, who wrote and depicted his personal experiences about epic battles, was the first memoirist. Later, it became a popular and acclaimed literary genre. Memoir serves to preserve history through a person’ eyes. Through memoir, celebrities also tell harsh sides of their careers. Rock stars tell their fans about tough days spent in distress, drug addicts reveal their struggle in seeking normal life, soldiers write war experiences, people who are mentally ill describe ups and downs to achieve clarity, and authors tell particular events that happened before their eyes. Hence, the function of memoir is to provide a window for the audience to have a look into the lives of other people.

Post navigation

- Scriptwriting

What is a Memoir — Definition, Examples in Literature & Film

M ost movies tell a story with a beginning, middle, and end. Many of those narrative features tell the story of a single individual that can span a certain amount of time, ranging from a few days to a few decades. Some of those focused narrative movies are also memoirs, which can include original and adapted screenplays. But what is a memoir and how can you identify one?

Memoir Definition

Let's define memoir.

Autobiographies are fairly common and known quantities in the world of literature. Memoirs are, too, but they are not as broad as autobiographies tend to be. This is key to understanding a memoir vs autobiography and how they tell their stories, which we go over below in our memoir definition.

MEMOIR DEFINITION

What is a memoir.

A memoir is a non-fiction story set in the author’s past during a specific period of their life. The name “memoir” comes from “memorie/memoria/memory,” as memoirs are essentially reminiscences of the author. A memoir is told completely through the author’s point of view. This means that facts can be embellished, with an emphasis on feelings and emotions.

Memoir Characteristics:

- Narrative tales set in a character’s past

- Stories set during a short period of time (as opposed to a lifetime)

- A greater emphasis on feelings, emotions, and perspectives versus factual storytelling

Memoir Meaning

History with examples.

Writing memoirs used to be something only a privileged few were able to indulge in, as they had the time and money to sit around and reminisce. Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic Wars and Commentaries on the Civil War are two very early memoir examples, with Caesar writing about the two respective wars, how they went, and his role in them.

While serving as memoirs, they also serve as historical records, which is something many other memoirs end up being. Thus, in these early examples, we can see both the personal and historical reasons for jotting down one’s specific memories.

As time went on, other people, be them important politicians or simply chroniclers of their era, were writing memoirs. Some of these included Sarashina Nikki of the Japanese Heian period (8th to 12th century); there were also several European memoir examples from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance .

The 18th and 19th centuries brought us closer to what we could consider more modern examples of memoirs. While these centuries were full of memoirs written by privileged politicians or aristocrats, there was at least one that broke the mold a bit.

Henry David Thoreau’s Walden is one of the most popular and well-known memoir examples in literature. Focusing on the two years, two months, and two days the author spent in a cabin, the memoir has Thoreau cover many subjects. These include living on your own to identifying plant life around him, among many other things.

You can learn more about who Thoreau was in the video below.

What is a memoir • Henry David Thoreau's memoir meaning

As access to writing materials and typing increased, and as the world became a bit more modern, more “regular” memoirs started to pop up. This was especially true during some of our darkest times, specifically the two world wars. From these great wars came memoirs from soldiers, victims, and survivors, including those in the trenches of World War I or in the concentration camps of World War II.

Closer to the 21st century, memoirs became even bigger as normal everyday people began jotting down their memories. In many cases, these memories were to preserve the history of a person or their family, as they would otherwise be lost without being written down.

In other cases, memoirs have served as forms of expression from the individual writers, detailing events in their life and the impact it had.

Related Posts

- What is an Adapted Screenplay? →

- The Best Book-to-Film Adaptations →

- How to Develop and Write a Script Adaptation →

Memoir Examples

Memoir vs. autobiography.

Reading the memoir definition, you may be wondering what exactly makes it different from an autobiography. Both are just chatting about yourself, right?

Both forms may indeed be chatting about oneself, but there is a difference between a memoir and an autobiography. A memoir is a look at a specific period from the writer’s life, or a sequence of specific periods that have thematic links. An autobiography, meanwhile, is the writer’s entire life (up until writing, of course).

Autobiographies also tend to be more rigorously fact-checked, while a memoir can be a bit more fast and loose with the facts as the writer weaves a story.

Of course, there are exceptions to this rule; sometimes an autobiography has some elements that aren’t totally truthful, but that’s usually frowned upon.

While they’re distinct in definition, the two terms occasionally overlap since their qualifications are a bit subjective.

Types of Memoirs

Because “memoir” is a pretty general term, there are many different ways the writing style can manifest. Over the years, a few categories for the genre have cropped up, though there are various schools of thought on the subject.

Personal Memoir

When you think of a memoir, this is probably the type that comes to mind. In this memoir, an author tackles a formative, personal experience from their life.

“I was small-boned and skinny, but more than able to make up for that with sheer meanness.”

— Mary Karr, The Liar's Club

There’s no limit to what this experience could be, but examples may be meeting a first love, enduring an illness, or navigating a relationship with a parent.

Portrait Memoir

With a portrait memoir, the subject is someone other than the author. Of course, the memoir is still through the eyes of the author, and they probably play a big role in the narrative, but the real focus lies with someone else.

“My father had lost most of the sight in his right eye by the time he’d reached eighty-six, but otherwise he seemed in phenomenal health for a man his age when he came down with what the Florida doctor diagnosed, incorrectly, as Bell’s palsy…”

— Philip Roth, Patrimony

This might be a parent (the amount of memoirs about parents, particularly complicated dads, could fill the Pacific Ocean), a best friend, a sibling, a teacher — really anyone who the author knows intimately. The film Aftersun loosely falls into the Complicated Dad subcategory of the portrait memoir.

Political Memoirs

This memoir is usually written by, you guessed it, politicians. It can be a personal memoir in form, but often with the larger goal of ingratiating themselves to the reader to get their vote or support their platform.

“Of all the rooms and halls and landmarks that make up the White House and its grounds, it was the West Colonnade that I loved best.”

— Barack Obama, A Promised Land

Political memoirs can also be written by people who aren’t politicians but are trying to further a political goal, like an activist. Some political memoir examples: Che Guevara's The Motorcycle Diaries , Michelle Obama’s Becoming , or Tony Blair’s A Journey .

Public Memoir

This type of memoir is a bit similar to the political memoir because it’s written by a person who’s already famous. But the public memoir usually doesn’t have a political ax to grind (at least, that’s not a requirement), it’s just a memoir by someone who’s well-known.

“Plainly, due to my high and solitary place in the world—am I not the Living Buddha (0r is that Richard Gere?)—and to my cold nature and to my refusal to conform to warm mature family values, I am doomed to be the eternal outsider…”

— Gore Vidal, Palimpsest

This celebrity will write about being famous and hanging out with other famous people, and they’ll make the GDP of a small country in book sales.

Travel Memoir

People like traveling, but it’s expensive and usually exhausting. So sometimes, we prefer to read about someone else who’s spending the money and traveling around the world.

“When you’re traveling in India—especially through holy sites and Ashrams—you see a lot of people wearing beads around their necks.”

— Elizabeth Gilbert, Eat, Pray, Love

A travel memoir can take a lot of different forms, but there’s one constant: the writer is moving around.

Writing Memoirs

How to write a memoir.

If these categories didn’t already make it clear, there’s no one way to write a memoir. It can be a straight-forward narrative or an avant-garde collection of scenes. But, hey, a few helpful tips can’t hurt.

You can learn a bit more about writing memoirs in the video below.

How to write a memoir

Know the “why”.

The most important question to ask yourself when you’re about to write the next great memoir is, “Why will people care about this?” If you don’t have a good answer, you may be writing a journal entry — which is totally fine; journaling is great and important in its own right.

But with a memoir, it’s crucial to have a greater purpose. This personal story may mean a lot to you (and if it doesn't, why are you writing it down at all?). But if someone doesn’t know you, why should they care that your sophomore year girlfriend broke up with you because she didn’t believe in your dream of becoming the premiere soft serve ice cream provider of Illinois?

There are many reasons a reader might care. Maybe your story in a larger sense is about young love and big dreams — we can all relate to that. Maybe the story is filled with drama: she broke up with you by pushing you into a vat of soft serve extract, and you spent months trying to get the solution out of your hair. Or maybe you’re the founder of Dairy Queen, and this is a glimpse into how it all started.

Beginning, Middle, End

It may seem obvious, but this fundamental rule of storytelling can be tricky when writing a memoir. The nature of a memoir means that there is going to be a story before and after the memoir ends.

My story goes something like this…

There’s no one way to find the beginning and end points of your memoir, but primarily, this should be rooted in the first piece of advice: have you achieved the “why”? If so, end it.

Don’t Get Stuck on Facts

This doesn’t mean lie. But if you feel the need to inform the reader of every detail of the story, it’s going to become a pretty dull read. It might all be true, but the “why” will have left the building.

Life doesn’t work in story arcs — things are messy, beginnings aren’t really beginnings and ends aren’t really ends. Of course, you want your memoir to reflect that to a certain extent, but you also want it to be readable. So omitting facts and cleaning up narrative elements (even if it’s not the complete and total truth) becomes crucial to the memoir style. The truth lies in the grand strokes, the emotions and characters.

Memoir Movies

Memoirs in cinema.

Memoirs have definitely been around longer than cinema, but movies about people and their lives (specifically biographies, aka biopics ) have been pretty common since the medium’s inception. Some of these movies could even count as memoir-esque, like Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), which, instead of chronicling Abraham Lincoln’s tenure as president (or his entire life), examines his time as a lawyer in the 1830s.

What is a memoir • Young Mr. Lincoln

So while there have been plenty of biographies, many of the most well-known movies based on memoirs have been fairly recent. One of the most high profile of these is Eat, Pray, Love , a 2006 memoir by Elizabeth Gilbert that turned into a 2010 movie starring Julia Roberts.

Eat, Pray, Love • A pinnacle in memoir movies

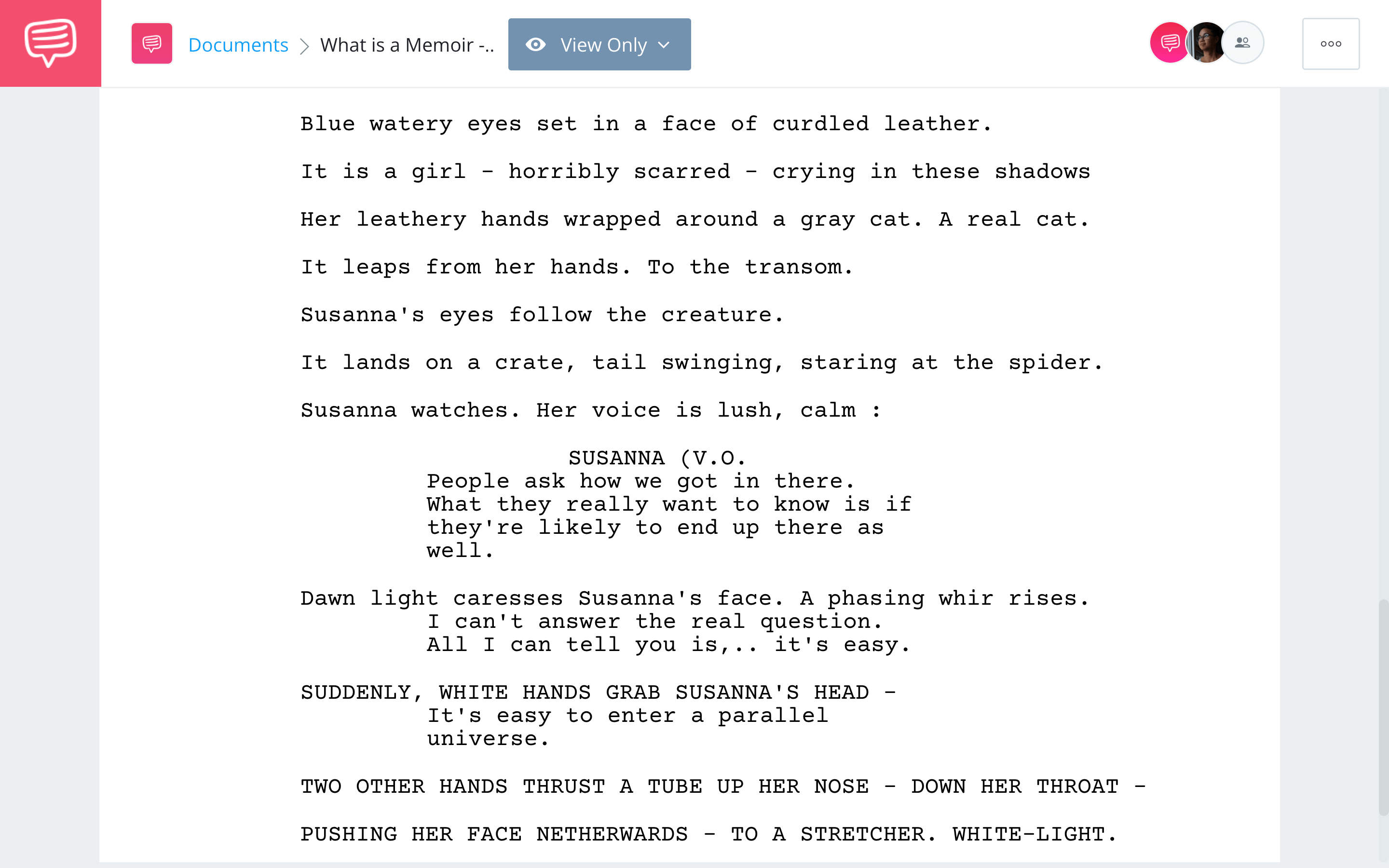

But even before that we had Girl, Interrupted , a 1993 memoir by Susanna Kaysen which made it into a film in 1999 starring Winona Ryder and Angelina Jolie. The opening lines of the film even retain the memoir feel.

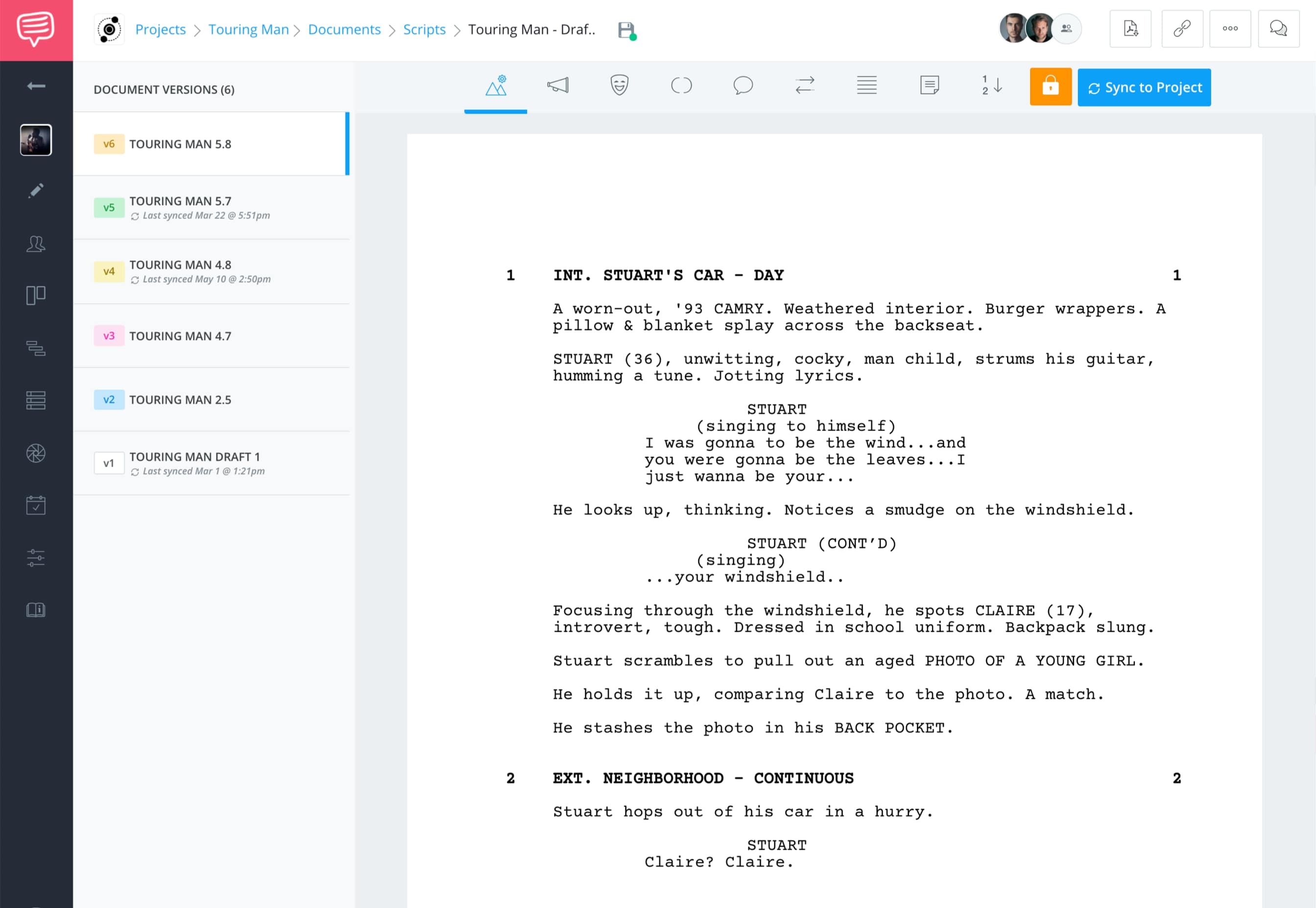

Take a look at them below, with the script that we imported into StudioBinder’s screenwriting software .

Girl, Interrupted • Read the entire opening

The voiceover feels like Kaysen answering the “why do we care” question that we outlined in our tips section.

And then of course there was The Basketball Diaries , a Jim Carroll memoir from 1978 that turned into a Leonardo DiCaprio movie in 1995. Here's the opening scene and credits.

Memoir movies • The Basketball Diaries

From 2009’s Julie & Julia (based on two separate memoirs) to The Theory of Everything 2014’s (the Stephen Hawking memoir written by his wife Jane Hawking) to 2018’s Beautiful Boy (based on two memoirs about the same subject), there has been no shortage of memoir based films in the last two decades.

Memoir movies • The Theory of Everything

Some are more successful and acclaimed than others, but like novels, there are plenty out there for filmmakers to adapt. And don’t forget there are also movies based on true events that weren’t chronicled in memoirs before, so if you want to adapt a moment in your life as a script for a movie, go for it.

How to Write an Adaptation

Now that we have covered memoirs and movies based on memoirs, it’s time to look at how you might go about adapting one. We cover the step-by-step process of adapting a book for the screen, all with examples and even some quotes.

Up Next: Writing an Adaptation →

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards..

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.

Learn More ➜

T he sitcom has been a staple of television for nearly 80 years. need a tight APP intro here that transitions to below..

The XYZ Script

Click to view and download the entire XYZ script PDF below.

Click above to read and download the entire XYZ script PDF

WHO WROTE THE XYZ SCRIPT?

Written by jonathan nolan, chris nolan, and david s. goyer.

VERY short bio about the screenwriter and a bit of history or trivia about this script. Perhaps the awards, accolades, or careers it's launched. This adds credibility and importance to the whole post. The image to the left should be swapped out with a SQUARE cropping of an image of the writer (400px compressed JPG). Make sure it's a polished photoshoot image like the one of Chazelle here. Cap this block at 10 lines.

Story beats in the XYZ script

Marshmallow pie sweet roll gummies candy icing. Marshmallow pie sweet roll gummies candy icing.Marshmallow pie sweet roll gummies candy icing. Marshmallow pie sweet roll gummies candy icing.

Script Teardown

Script structure of "movie title", 1. exposition (beginning).

Write a brief description here. Try to keep this approximately 2-3 sentences or about 15-30 words.

2. INCIDITING INCIDENT

3. climax of act one, 4. obstacles (rising action), 5. midpoint (big twist), 6. disaster & crisis, 7. climax of act two, 8. climax of act three, 9. obstacles (descending action), 10. denouement (wrap up), 11. resolution, xyz script takeaway #1, writing style / unique execution / or searched scene.

This section will be a scene study of something novel. It could be an example of a general writing style, or unique execution, formatting of something specific (e.g. pre-laps, musical sequences, suspense, twist reveals, etc), dialogue scene. If, in your SEO research you find people searching for a particular scene, then that's a hint it should become a scene study section and keyword used in the heading.

You can have anywhere from 1-3 sections like this in the post.

Embed the video from Youtube and set it up, letting the reader know what to focus on in the video.

Scene Study: Tommy buys a dozen red roses

After the embed, set up the script tie-in. Call out what they should focus on and provide a good reason on why they should click the app tie-in. In many cases this would be to read the entire scene. In other cases, you could add something clever in the comments or script notes, or versions.

Also, since the app link opens a script at Scene 1, you'll want to let them know what scene number they should scroll down to.

Read the Flower Shop Scene — Scroll to Scene XX

Marshmallow pie sweet roll gummies candy icing. Marshmallow pie sweet roll gummies candy icing. I love candy canes soufflé I love jelly beans biscuit. Marshmallow pie sweet roll gummies candy icing.

Marshmallow pie sweet roll gummies candy icing. I love candy canes soufflé I love jelly beans biscuit. Marshmallow pie sweet roll gummies candy icing.

- Start breaking down your script →

- Learn how to analyze and break down a script →

- FREE Download: Script Breakdown Sheet Template →

Setup the next logical script for this reader to review. Keep in mind the style, genre, and writer of the above script. For example, a Tarantino script should have an Up Next to another Tarantino script (ideally), or another pulp-y script (e.g. Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels), or a similar genre, or dialogue-heavy script by another relevant auteur (e.g. PT Anderson).

Up Next: Article Name →

Write and produce your scripts all in one place..

Write and collaborate on your scripts FREE . Create script breakdowns, sides, schedules, storyboards, call sheets and more.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- What is Film Distribution — The Ultimate Guide for Filmmakers

- What is a Fable — Definition, Examples & Characteristics

- Whiplash Script PDF Download — Plot, Characters and Theme

- What Is a Talking Head — Definition and Examples

- What is Blue Comedy — Definitions, Examples and Impact

- 0 Pinterest

Learn how to become the author you were meant to be

- Self-Publishing

- Author Spotlight

Everything You Need to Know About Writing a Memoir

Table of contents, introduction, what types of memoirs are there, preparing to write a memoir, how to choose a theme for your memoir, how to create a memoir outline, publishing your memoir.

Today I’m talking about a captivating, life-changing, beautiful story. Yours .

It’s a story about the most meaningful parts of your life. The people you’ve met along the way, who each gave you something extraordinary. The life lessons you could only learn through experience. A tale of love and loss, time and place, luck and opportunity.

It’s a story only you can tell. And yes, you should tell it.

A well-written memoir can have blockbuster-worthy plot lines, yet it’s so much more than a paperback by the pool. Real-life experience—life, family, trauma, loss, love—are powerful and profound when shared firsthand with others.

The art of storytelling has been a proven tool throughout human history, one that can be just as powerful for the storyteller as it is for all who listen. It’s practically hard-coded in our DNA.

You’re reading this article, which means there is a fairly good chance you have a personal story that aches to be released. Your first step in writing a memoir is to understand and own your motivations for doing so. If financial gain is at the top of your list, I’d encourage you to discover a stronger driving force. Money is a mercurial muse. Even if you don’t make a dime, writing your memoir could be a deeply rewarding experience—one that may rival the actual story itself. (More on this in a bit.)

Writing your memoir will also be a process, and—if I’m honest—a sometimes painful one. After over 20 years of working with authors, I’ve walked through memoir-writing with the most well-intentioned writers. I’ve witnessed them flying through a manuscript, alight with memory. I’ve watched them take themselves by surprise as writing their story reveals new insight into who they really are and who they’ve become.

I’ve also seen them run headlong into writer’s block as they struggle with too many words, feelings, and outside opinions. I’ve seen them come up empty at the end of their stories because they’ve chased the wrong plotline. I’ve seen them get in their own way, rush the process, and make unfortunate technical mistakes that erase their life’s work with a press of a button or a crash of a server.

And that’s why I’m writing this article. To walk you through the most critical steps of bringing your story to life, from figuring out where to start to finding someone to help you publish (those of you who are further along in this process are welcome to jump ahead).

After you settle into your true motivations, the next step is to get absolutely clear about what you want to achieve with your story.

Will it be a personal processing tool for you? Are you hoping to translate your experiences into words of wisdom for others? Are you looking to account for every single detail of your life? (That’s a whole other story—more on that below.)

The Teaching Memoir

Some life lessons leave a legacy. Whether it’s a cautionary tale or an invitation to live life to the fullest, a teaching memoir story weaves in wisdom while challenging and equipping readers to overcome their own obstacles. These books are a type of “ practical nonfiction ” and are some of my favorites. There is something special about empowering your readers to find answers, healing, and even peace—and knowing your life experiences will help them. It’s like you were born to do it.

The Personal Memoir

While some may argue that every story is a teaching experience, if your deepest desire is to focus on retelling your journey during a specific period, a sequence of events, or an overarching theme of your life, you’re writing a personal memoir. Personal memoirs are a powerful invitation to readers to join you on your adventure and experience your unique perspective. You’re simply (read: not always easily!) recounting your experiences as vibrantly as you lived them—to entertain your readers, to move and inspire them, and to honor the life you’ve had.

They may still learn something—but that lesson is theirs, not yours.

The Difference Between a Memoir and an Autobiography

Capturing every detail of your life from birth through the present might be your passion project—but that makes it an autobiography, not a memoir. An autobiography is a biographical summary of your entire life written by the only person with all the intimate details (psst…that’s you). While occasionally anecdotal, this long-spanning story is more fact and detail-driven, preserving your legacy for generations to come.