Business Math: A Step-by-Step Handbook

(0 reviews)

Jean-Paul Olivier

Copyright Year: 2017

Last Update: 2021

Publisher: Lyryx

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Table of Contents

PART 1: Mathematic Fundamentals for Business

- Chapter 1: How To Use This Textbook

- Chapter 2: Back to the Basics

- Chapter 3: General Business Management Applications

PART 2: Applications in Human Resources, Economics, Marketing, and Accounting

- Chapter 4: Human Resource & Economic Applications

- Chapter 5: Marketing and Accounting Fundamentals

- Chapter 6: Marketing Applications

- Chapter 7: Accounting Applications

PART 3: Applications in Finance, Banking, and Investing: Working With Single Payments

- Chapter 8: Simple Interest: Working With Single Payment & Applications

- Chapter 9: Compound Interest: Working With Single Payments

- Chapter 10: Compound Interest: Applications Involving Single Payments

PART 4: Applications in FInance, Banking, and Investing: Working With A Continuous Series of Payments (Annuities)

- Chapter 11: Compound Interest: Annuities

- Chapter 12: Compound Interest: Special Applications of Annuities

PART 5: Applications in Finance, Banking, and Investing: Amortization and Special Concepts

- Chapter 13: Understanding Amortization & Its Applications

- Chapter 14: Bonds and Sinking Funds

- Chapter 15: Making Good Decisions

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Business Mathematics was written to meet the needs of a twenty-first century student. It takes a systematic approach to helping students learn how to think and centers on a structured process termed the PUPP Model (Plan, Understand, Perform, and Present). This process is found throughout the text and in every guided example to help students develop a step-by-step problem-solving approach.

This textbook simplifies and integrates annuity types and variable calculations, utilizes relevant algebraic symbols, and is integrated with the Texas Instruments BAII+ calculator. It also contains structured exercises, annotated and detailed formulas, and relevant personal and professional applications in discussion, guided examples, case studies, and even homework questions.

About the Contributors

Jean-Paul Olivier has been teaching Business and Financial Mathematics, as well as Business Statistics and Quantitative Methods for the past 21 years. He is a dedicated instructor interested in helping his students succeed through multi-media teaching involving PowerPoints, videos, whiteboards, in-class discussions, readings, online software, and homework practice. He regularly facilitates these quantitative courses and leads a team of instructors. You may have met Jean-Paul at various mathematical and statistical symposiums held throughout Canada (and the world). He has contributed to various mathematical publications for the major publishers with respect to reviews, PowerPoint development, online algorithmic authoring, technical checks, and co-authoring of textbooks. This text represents Jean-Paul’s first venture into solo authoring

Contribute to this Page

- Math Article

Business Mathematics

Business Mathematics consists of Mathematical concepts related to business. It comprises mainly profit, loss and interest. Maths is the base of any business. Business Mathematics financial formulas, measurements which helps to calculate profit and loss , the interest rates, tax calculations, salary calculations, which helps to finish the business tasks effectively and efficiently.

Table of contents:

- Related Topics

- Important Terms

- Problems and Solutions

Business Mathematics is highly related to the Statistics concepts which give solutions to business problems. In business, we deal with the exchange of money or products, which have a monetary value. Each business leads to some profit and some loss. To identify these factors, we have to study the primary topics of Maths such as formulas to find a profit, loss, their percentages, discount, etc. Even Though, the requirement of this subject does not contain pure Maths, it needs Mathematical thinking and some Maths formulas . Here, we will discuss what is Business Mathematics, terminologies, and important formulas with problems and solutions.

What is Business Mathematics?

Business Math always deals with profit or loss. The cost of a product is fixed by taking into consideration it’s profit, margin, cash discount, trade discount, etc. Business mathematics is used by commercial companies to record and manage business works. Commercial businesses use maths in departments of accounting, inventory management, marketing, sales forecasting and financial analysis.

Business Mathematics Topics

The most important topics covered in Business Mathematics are:

- Profit and Loss

- Simple and Compound Interest

- Interest Rates

- Markups and markdowns

- Taxes and Tax Laws

- Discount Factor

- Depreciation

- Future and Present Values

- Financial Statements

Business Mathematics Basic Terms

- Selling Price: The market price is taken to sell a product.

- Cost Price: The original price of the product is the cost price.

- Profit: If the selling price is more than the cost price, the difference in the prices is the profit.

- Loss: If the selling price is less than the cost price, the difference in the prices is the loss.

- Discount: The reduced amount in the selling price of a product.

- Simple Interest: Simple interest is that interest which is counted against the capital amount or the portion of the main amount that remains unpaid.

- Compound Interest: Compound interest is the investment rate that increases exponentially.

Business Mathematics Formulas

Here, the 9 basic Business Mathematics formulas that we cannot ignore. They are:

Net Income Formula:

Net Income = Revenue – Expense

Accounting Equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

Equity = Assets – Liabilities

Cost of Goods Sold Formula:

COGS = Beginning inventory + Purchase during the period – Ending inventory

Break-Even point Formula:

Break-Even Point = Fixed cost / (Sales Price per unit – variable cost per unit)

Current Ratio Formula:

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities

Profit Margin Formula:

Profit Margin = (Net Income/ Revenue) × 100

Return of Investment (ROI) Formula:

ROI = [(Invest gain – Cost of Investment)/ Cost of Investment] × 100

Markup Formula:

Markup Percentage = [(Revenue- COGS)/COGS] × 100

Selling Price using Markup = (COGS × markup percentage) + COGS

COGS = Cost of goods sold

Inventory Shrinkage Formula:

Inventory Shrinkage = [(Recorded Inventory – Actual Inventory)/ Recorded Inventory] × 100

Business Mathematics Example

While doing business, one can earn a good profit or face loss. The price of a product is fixed, taking into consideration it’s cost price, profit, margin, trade discount, cash discount, etc. The price marked on the commodity is called marked price or catalogue price. For trading purposes, the manufacturer proposes a discount on the MRP to the buyer. This is called a trade discount. In addition to the trade discount, if the buyer pays cash against goods, he gets another cut called cash discount. The price of the object after subtracting the trade discount and cash discount is called the selling price. Thus, we have, Selling price = Cost price – Dis counts. Let us discuss the most important concept called “Profit and Loss” here.

Profit and Loss:

A profit is the earned amount received by a business on selling a product whereas loss is the amount which is less than the actual price of the product. The formula for profit and loss is given based on the selling price and cost price of a commodity.

Both these measures have their percentage value also and they are given by;

Business Mathematics Problems and Solutions

Question 1: A music system was bought for Rs.10,500 and sold at Rs.9,500. Find the amount of profit or loss.

Solution: Given,

Cost Price of the music system = Rs.10,500

Selling Price of the music system = Rs. 9,500

We can see here, C.P. is greater than S.P. Therefore, there is a loss in this business.

Hence, we need to calculate the loss amount.

Loss = C.P. – S.P.

Loss = 10,500 – 9,500 = Rs.1,000/-.

Question 2: A pair of shoes is bought at Rs 200 and sold at a profit of 10%. Find the selling price of the shoes.

Profit = 10% of Rs.200

P = (10/100) × 200 = Rs. 20

S.P. = C.P. + Profit

S.P. = 200 + 20 = Rs.220/-

Question 3: If the cost price of an article including 20% for taxes is Rs. 186, then find the original cost of the article excluding taxes.

Let x be the original price of an article.

Tax = 20% of x = (20/100) × x = 0.2x

According to the given statement,

Original cost + tax = New cost price

x + 0.2x = Rs. 186

1.2x = Rs. 186

x = Rs. 186/1.2

x = Rs. 155

Therefore, the cost of the article without taxes = Rs. 155

Keep Visiting BYJU’S – The Learning App and register with the app to get all the Mathematics related topics to learn with ease.

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

What to Know About Business Math

- Math Tutorials

- Pre Algebra & Algebra

- Exponential Decay

- Worksheets By Grade

No matter what your career, business math will give you indispensable real-world knowledge to help you take control of your finances. Take the first step in making better choices with your money by getting familiar with business mathematics.

What Is Business Math?

Business math is a type of mathematics course that is meant to teach people about money and provide them with the tools they need to make informed financial decisions. Business math not only teaches about the specifics of finances related to owning and operating a business but also offers helpful advice and information related to personal finance. These classes prepare any consumer to manage their finances responsibly and profitably by explaining everything they need to know about accounting, economics, marketing, financial analysis, and more. Business math will help to make the ins and outs of money and commerce make sense, even to the most math-averse individuals, using relevant and authentic applications.

Why Take Business Math?

Business math is not just for business owners, contrary to what its name might suggest. A number of different professionals utilize business math-related skills every day.

Bankers, accountants, and tax consultants all need to become well-acquainted with every aspect of corporate and personal finance in order to deliver appropriate advice and problem solve with customers. Real estate and property professionals also employ business mathematics often when calculating their commission, navigating the mortgage process, and managing taxes and fees upon closing a deal.

When it comes to professions that deal more with capital allocation, such as investment consulting and stockbroking, understanding investment growths and losses and making long-term financial predictions is a fundamental part of the daily job. Without business math, none of these jobs could function.

For those that do own a business, business math is even more important. Business math can help these individuals to be successful by providing them with a solid understanding of how to manage goods and services to make a profit. It teaches them how to juggle discounts, markups, overhead, profits, inventory management, payroll, revenue, and all of the other complexities of running a business so that their career and finances can flourish.

Topics Covered in Business Math

Economics, accounting, and other consumer math subjects likely to be taught in a business mathematics course include:

- Depreciation

- Discount Factor

- Financial Statements (personal or business)

- Future and Present Values

- Interest rates

- Investment and Wealth Management

- Markups and Markdowns

- Mortgage Finance and Amortization

- Product inventory

- Taxes and Tax Laws

- Simple and Compound Interest

Mathematical Skills That Will Prepare You for Business Math

If you decide that a business math course will help further your career or if you would just like to be more financially savvy, a strong understanding of the following mathematical concepts will help to prepare you for this course.

- Be comfortable reading, writing, and making estimates for whole numbers up to 1,000,000.

- Be able to add, subtract, multiply, and divide any integers (using a calculator if needed).

Fractions, Decimals, and Percentages

- Be able to add, subtract, multiply, and divide fractions, simplifying as needed.

- Be able to calculate percentages.

- Be able to convert between fractions, decimals, and percentages.

Basic Algebra

- Be able to solve equations with one or more variables.

- Be able to calculate proportions .

- Be able to solve multi-operational equations.

- Be able to correctly apply values and variables to any given formula (e.g. when given the formula for calculating simple interest, I=Prt, be able to input the correct values for P=principal, r=interest rate, and t=time in years to solve for I=interest). These formulas do not need to be memorized.

- Be able to solve for the mean, median and mode of a data set

- Be able to interpret and understand the significance of the mean, median, and mode.

- Be able to interpret different types of graphs and charts such as bar and line graphs, scatter plots, and pie charts to understand the relationships between different variables.

- 7th Grade Math Course of Study

- The Typical 10th Grade Math Curriculum

- Math Glossary: Mathematics Terms and Definitions

- Eighth Grade Math Concepts

- Compound Interest Worksheets

- Lesson Plan: Adding and Multiplying Decimals

- Two-Digit Multiplication Worksheets to Practice With

- The Horse Problem: A Math Challenge

- Exponents and Bases

- Fifth Grade Math - 5th Grade Math Course of Study

- Words Used to Discuss Money

- 5 Business Jobs You Can Do Without a Business Degree

- Algebra: Using Mathematical Symbols

- Calculating the Mean, Median, and Mode

- Report Card Comments for Math

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4: Business Math

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 35415

- 4.1: Ratio and Proportion Examples and applications of ratios are limitless: speed is a ratio that compares changes in distance with respect to time, acceleration is a ratio that compares changes in speed with respect to time, and percentages compare the part with the whole. We’ve already studied one classic ratio, the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter, which gives us the definition of π.

- 4.2: Introduction to Ratios and Rates We use ratios to compare two numeric quantities or quantities with the same units.

- 4.3: Introduction to Proportion In this section, we equate ratio and rates in a construct called a proportion.

- 4.4: Percent

- 4.5: Percent, Decimals, Fractions So, when you hear the word “percent,” think “parts per hundred.”

- 4.6: Solving Basic Percent Problems

- 4.7: General Applicants of Percent

- 4.8: Percent Increase or Decrease A person’s salary can increase by a percentage. A town’s population can decrease by a percentage. A clothing firm can discount its apparel. These are the types of applications we will investigate in this section.

- 4.9: Interest

- 4.10: Pie Charts

- Exam Prep >

- Prepare for Business School >

- Business School & Careers >

- Explore Programs >

- Connect with Schools >

- How to Apply >

- Help Center >

Every journey needs a plan. Use our Career Guide to get where you want to be.

Creating an account on mba.com will give you resources to take control of your graduate business degree journey and guide you through the steps needed to get into the best program for you.

- About the Exam

- Register for the Exam

- Plan for Exam Day

- Prep for the Exam

- About the Executive Assessment

- Register for the Executive Assessment

- Plan for Assessment Day

- Prepare for the Assessment

- NMAT by GMAC

- Shop GMAT Focus Official Prep

- About GMAT Focus Official Prep

- Prep Strategies

- Personalized Prep Plan

- GMAT Focus Mini Quiz

- Executive Assessment Exam Prep

- NMAT by GMAC Exam Prep

Prepare For Business School

- Business Fundamentals

- Skills Insight

Business School & Careers

- Why Business School

- Student Experience

- Business Internships

- B-School Go

- Quiz: Are You Leadership Material?

- MBA Return on Investment (ROI) Calculator

- Estimate Your Salary

- Success Stories

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Women in Business

Explore Programs

- Top Business School Programs

- Quiz: Which Post Graduate Program is Right for You?

- Quiz: Find the Best Program for Your Personality

- Business School Rankings

- Business Master's Programs

- MBA Programs

- Study Destinations

- Find Programs Near Me

- Find MBA Programs

- Find Master's Programs

- Find Executive Programs

- Find Online Programs

Connect with Schools

- About GradSelect

- Create a GradSelect Profile

- Prep Yourself for B-School

- Quiz: Can You Network Like An MBA?

- Events Calendar

- School Events

- GMAC Tours Events

- In-Person Events

- Online Events

How to Apply

- Apply to Programs

- The Value of Assessments

- Admissions Essays

- Letters of Recommendation

- Admissions Interviews

- Scholarships and Financing

- Quiz: What's Your Ideal Learning Style?

Help Center

- Create Account

- Exams & Exam Prep

How to Master GMAT Problem Solving

Stacey Koprince - Manhattan Prep

Stacey Koprince is an mba.com Featured Contributor and the content and curriculum lead and an instructor for premier test prep provider Manhattan Prep .

The GMAT™ exam feels like a math test, especially GMAT Problem Solving problems. They read just like textbook math problems we were given in school; the only obvious difference is that the GMAT Quant section gives us five possible answer choices.

It’s true that you have to know certain math rules and formulas and concepts, but actually, the GMAT is really not a math test. First of all, the test doesn’t care whether you can calculate the answer exactly (e.g., 42). It cares only that you pick the right answer letter (e.g., B)—and that’s not at all the same thing as saying that you have to calculate the answer exactly, as you did in school.

More than that, the GMAT test-writers are looking for you to display quantitative and critical reasoning skills (the section is literally called Quantitative Reasoning ); in other words, they really want to see whether you can think logically about quant topics. They’re not interested in testing whether you can do heavy-duty math on paper without a calculator. And here’s the best part: They build the problems accordingly and you can use that fact to make GMAT Problem Solving problems a whole lot more straightforward to solve. I’ll show you how in this article!

GMAC’s team (aka, the people who make the GMAT) gave me three random problems to work through with you. I had no say in the problems; I didn’t get to choose what I liked. Nope, these three are it, and every single one illustrates this principle: The GMAT is really a test of your quantitative reasoning skills, not your ability to be a textbook math whiz.

GMAT Quant is not a math test

Okay, let’s prove that claim I just made. Grab your phone and set the timer for 6 minutes. (If you’ve been granted 1.5x time on the GMAT, set it for 9 minutes. If you’ve been granted 2x time on the GMAT, set it for 12 minutes.)

Do the below 3 problems under real GMAT conditions:

- Do them in order. Don’t go back.

- Pick an answer before you move to the next one. (Don’t just say you’re not sure and move on. Make the guess, as you have to do on the real test.)

- Have an answer for all the problems by the time your timer dings—even if your answers are random guesses.

Problem #1: Fellows in the org

According to the table above, the number of fellows was approximately what percent of the total membership of Organization X?

(A) 9% (B) 12% (C) 18% (D) 25% (E) 35%

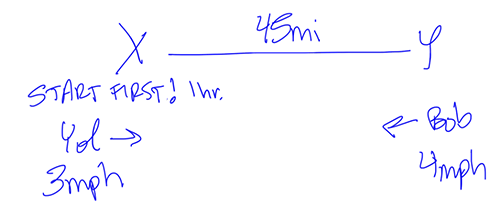

Problem #2: Yolanda and Bob

One hour after Yolanda started walking from X to Y, a distance of 45 miles, Bob started walking along the same road from Y to X. If Yolanda’s walking rate was 3 miles per hour and Bob’s was 4 miles per hour, how many miles had Bob walked when they met?

(A) 24 (B) 23 (C) 22 (D) 21 (E) 19.5

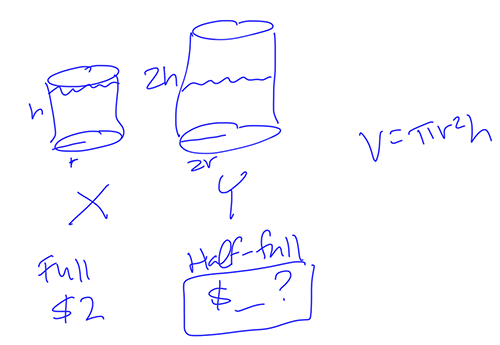

Problem #3: Oil cans

Two oil cans, X and Y, are right circular cylinders, and the height and the radius of Y are each twice those of X. If the oil in can X, which is filled to capacity, sells for $2, then at the same rate, how much does the oil in can Y sell for if Y is filled to only half its capacity?

(A) $1 (B) $2 (C) $3 (D) $4 (E) $8

Time’s up! Do you have an answer for each problem? If not, make a random guess—but do choose an answer for every problem.

You probably want me to tell you the three correct answers so you’ll know whether you got them right. But I’m not going to.

We’re going to review these in the same way that I want you to review them when you’re studying on your own—and that means *not* looking up the correct answer right away.

- How confident are you about this problem?

- Did/do you have another idea for how to solve? Try it now.

- Were you straining to remember some rule or formula? Look it up and try again.

- Still stuck? Okay, look at the correct answer. Does knowing that give you any ideas? Push them as far as you can.

- Stuck again? Start to read the explanation. Stop as soon as the explanation gives you a new idea. Push it as far as you can before you come back to the explanation again.

Basically, push your own thinking and learning as far as you can on your own. Use the correct answer and explanation only as a series of hints to help unstick yourself when you get stuck.

Okay, let’s dive in!

GMAT Problem Solving #1: Estimate

We’re going to use the UPS solving process: Understand, Plan, Solve. (A mathematician named George Polya came up with this.) Use this rubric to approach any quant-based problem you ever have to figure out in your life!

The basic idea is this: Don’t just jump to solve. (That’s panic-solving! We’ve all been there. It does not end well.) Understand the info first. Come up with a plan based on what you see. Only then, solve.

And if you don’t understand or can’t come up with a good plan? On the GMAT, bail! Pick your favorite letter and move on. UPS can help you know what to do and what not to do.

Glance at the answers. Yes, before you even read the problem!

The answers indicate that this is a percent problem and they’re also pretty decently spread apart. One is a little less than 10% and another is a little greater than 10%, so that’s one nice split. The remaining three are a little less than 20%, exactly 25%, and about 33%, otherwise known as one-third. Those are all “benchmark,” or common, percentages, so now I know I can probably estimate to get to my answer. Excellent.

And then the problem actually includes the word approximately ! Definitely going to estimate on this one.

Start building a habit of glancing at the answers on every single Problem Solving problem during the Understand phase, before you even think about starting to solve. (And yes, I really do glance at the answers before I even read the question stem!)

Here are some examples of the types of answer-choice characteristics that indicate there’s a good chance you’ll be able to estimate at least a little:

- The answers are really spread out (e.g., 10, 100, 300, 600, 900)

- Some are positive and some are negative

- Some are less than 1 and some are greater than 1

- They’re spread out on a percent scale (0 to 100) or on a probability scale (0 to 1)—less than half, greater than half, etc.

Next, there’s a table with a bunch of categories and each category is associated with a specific number. What does the question ask?

It wants to know the Fellows as a percent of the total. That’s a fraction with fellows on the top and the total of all members on the bottom:

The Fellows category is already listed in the table. Great, that’s the numerator.

What about the total? That means adding up all the numbers in the table without a calculator or Excel. Rolling my eyes. And that’s how I know that I will not be doing “textbook math” here. Pay attention to those feelings of annoyance! There’s some other easier, faster path to take. Use your Plan phase to find it.

I need the Total. I can estimate. Look at the collection of numbers. Can you group any into pairs that will add up to “nicer” numbers—numbers that end in zeros?

Here’s one way:

- Honorary is a tiny number compared to the rest. Ignore it.

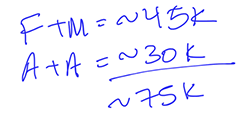

- Fellows are a little under 10,000 and Members are a bit over 35,000. Group them.

- Associates are a little less than 28,000 or a little more than 2,000 away from 30,000. And Affiliates are a little over 2,000! Combine those two groups.

We’re already spilling into the solve stage on this one. Fellows and Members together are about 45,000. Associates and Affiliates together are about 30,000. Altogether, there are 75,000 members:

That goes on the bottom of the fraction. Fellows go on top. They’re about 9,200, so let’s call that 9,000. Make a note on your scratch paper that you’re underestimating —just in case you need to use that to choose your final answer. I use a down-arrow to remind myself.

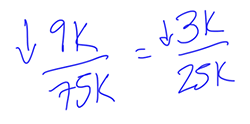

How to simplify 9 out of 75? Both of those numbers are divisible by 3.

Ok, 3 out of 25: what percent is that? We normally see percentages as “out of 100.” Hmm.

If you multiply the denominator by 4, that gets you to “out of 100.” And whatever you do to the denominator, you have to do to the numerator, so the fraction turns into 12 out of 100, or 12%.

12% is in the answers; the next closest greater value (since we slightly underestimated) is 18%. That’s too far away, so the only answer that makes sense is (B).

Notice how the numbers looked really ugly to start out, but as soon as you started estimating, they combined and simplified really nicely? It’s not just luck. The test-writers know you don’t have access to a calculator, so they’re building the problems to work out nicely if you use these types of approaches. They actually want to reward you for using the kind of quantitative reasoning that you’d want to use at work and in business school.

You can certainly solve GMAT Problem Solving problems using traditional textbook math approaches. You’ll just do a lot more work that way. And using textbook approaches won’t actually help train your brain for the kind of analytical thinking about quant that you’ll need to do in business school or in the working world.

Free GMAT™ Prep from the Makers of the Exam

The best way to jumpstart your prep is to familiarize yourself with the testing platform and take practice tests with real GMAT exam questions.

GMAT Problem Solving #2: Logic (and draw!) it out

One hour after Yolanda started walking from X to Y, a distance of 45 miles, Bob started walking along the same road from Y to X. If Yolanda’s walking rate was 3 miles per hour and Bob’s was 4 miles per hour, how many miles had Bob walked when they met?

The answers are real values and on the smaller side. They’re pretty clustered, so probably won’t be estimating on this one. Four of the five are integers. I wonder whether I can work backwards on this one (i.e., just try some of the answers)?

This problem is what I call a Wall of Text—a story problem. Get ready to sketch this out. Take your time understanding the setup; if you don’t “get” the story, you’ll never find the right answer. (And if you don’t get the story, that’s your clue to guess and move on.)

There are two people, 45 miles apart, and they’re walking towards each other. Normally, I’d only write initials for the two people, but annoyingly, Yolanda shares her initial with one of the locations.

The first sentence has a critical piece of info that’s easy to gloss over: Yolanda starts first, an hour before Bob.

It’s super annoying that they don’t start at the same time. I don’t know what to do about that yet, but I’m noting it because I want to think about that when I get to my Plan stage. Again, pay attention to whatever annoys you about the problem! That’s why I put START FIRST in all-caps on my scratch paper.

Next, Yolanda walks a little slower than Bob. Add that to your diagram.

Finally, the problem asks who walked further by the time they meet—and how far that person walked. If Yolanda and Bob had started at the same time, then I’d know Bob walked farther, since he’s walking faster, but Yolanda started first, so I can’t tell at a glance. Still annoyed by that detail.

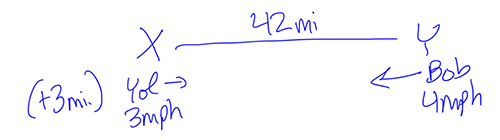

The two people have to cover 45 miles collectively in order to meet somewhere in the middle. Glance at the answers again. There are two sets of pairs that add to 45: (A) 24 and (D) 21 and (B) 23) and (C) 22.

On a problem like this one, the most common trap answer is going to be solving for the wrong person (in this case, Yolanda instead of Bob). So the correct answer is going to fall into one of those pairs, because then the most common trap answer will also be built into the problem. The other pair will represent some common error when solving for Bob—and then also mistakenly solving for Yolanda instead. But answer (E) 19.5 doesn’t have a pairing, so it has no built-in trap. If you have to guess, don’t guess the unpaired answer, (E).

Once I subtract the 3 miles that Yolanda walked alone, the two of them together have 42 more miles to cover before they meet. I did note the extra 3 miles she walked off to the side just in case.

Bingo. Now I know how I’m going to solve this problem, because now it’s a more straightforward rate problem.

From here, you can do the classic “write some equations and solve” approach to rates problems. But I’m going to challenge you to keep going with this Logic It Out approach we’re already using—both because it really is easier and because it’s what you would use in the real world. You’re not getting ready to take the GMAT because you want to become a math professor. You’re doing this to be able to think about quant topics in a business context. So make your GMAT studies do double-duty and get you ready for b-school (and work!) as well.

Back to Bob and Yolanda. They’re 42 miles apart and walking towards each other. Every hour, Yolanda’s going to cover 3 miles and Bob’s going to cover 4 miles, so they’re going to get 7 miles closer together. Together, they’re walking 7 miles per hour.

When two people (or cars or trains) are moving directly towards each other, you can add their rates and that will tell you the combined rate at which they’re getting closer together. (You can do the same thing if the two people are moving directly away from each other—in this case, the combined rate is how fast they’re getting farther apart.)

One more thing to note: The distance still to cover is great enough (42 miles) compared to their combined rate (just 7 mph) that Bob is going to “overcome” the 3 miles that Yolanda walked on her own first. So Bob covered a greater distance than Yolanda did. The answer is going to be one of the two greater numbers in the pairs: (A) 24 or (B) 23.

So Yolanda and Bob are getting closer together at a rate of 7 miles each hour and they have a total of 42 miles to cover until they meet. How long is it going to take them?

Divide 42 by 7. They’re going to meet each other after 6 hours on the trail. At this point, Bob has spent a total of 6 hours walking, but not Yolanda! She started first, so she spent a total of 6 + 1 = 7 hours walking. The question asks how far Bob walked: 4 miles per hour for 6 hours, or a total of (4)(6) = 24 miles.

The correct answer is (A).

If you’d solved for Yolanda first, you’d have gotten (3 miles per hour)(7 hours) = 21 miles. That’s in the answer choices, but it’s less than half of the total distance, so she wasn’t the one who walked farther. In other words, answer (D) is a trap.

Even if you do know how to solve the problem, it’s important to have done that earlier thinking to realize that the answer must be (A) or (B). That way, when you solve for Yolanda, you won’t accidentally fall for answer (D), since Yolanda’s distance is in the answer choices.

When the problem talks about two people or two angles in a triangle or two whatevers and the problem also tells you what they add up to, the non-asked-for person/angle is almost always going to show up in the answer choices as a trap. You do the math correctly, but you accidentally solve for x when they asked you for y . We’ve all made that mistake.

Noticing that detail earlier in your process is a great way to avoid accidentally falling for the trap answer during your Solve phase.

(Have Polya and I sold you yet on using the UPS process? I hope so.)

Should I Retake the GMAT?

Should you retake the GMAT, and does retaking the GMAT look bad? Manhattan Prep’s Stacey Koprince answers the most common retake the GMAT questions.

GMAT Problem Solving #3: Draw it out; Do arithmetic, not algebra; Choose smart numbers

Glance at the answers. Small integers. Kind of close together, so estimation might not be in the cards, but perhaps working backwards (try the answer choices) could work, depending on how the problem itself is set up. (I don’t know yet because I haven’t actually read the problem.)

Now I’m part-way into the first sentence and see the word cylinders . Overall, I’m not a fan of geometry and I really dislike 3D geometry in particular. So as soon as I see that word, part of my brain is thinking, “If this is a hard one, I’m out.”

But I’m going to finish reading it before I decide. Let’s see. Two cylinders, and then they give me some relative info about the height and radius. They’re probably going to ask me something about volume, since the volume formula uses those measures, and scanning ahead: yep, volume.

So now I know I need to jot down the volume formula and I’m also going to draw two cylinders and label them.

I’m going to make sure I note really clearly what I’m trying to solve for. On geometry problems in particular, it’s really easy to solve for something other than the thing they asked you for. And on this one, I’m also making an extra note that the larger cylinder is only half full. I both wrote that down and drew little water lines in the cylinders to cement that fact in my brain.

This is a complex problem, so just pause for a second here. Do you understand everything they told you, including what they asked you to find? If not, this is an excellent time to pick your favorite letter and move on.

If you are going to continue, don’t jump straight to solving. Plan first. (And if you can’t come up with a good plan, that’s another reason to get out.)

The thing that’s annoying me: They keep talking about the dimensions for the two cylinders but they never provide real numbers for any of those dimensions. And boom, now I know how I’m going to solve. When they talk about something but never give you any real numbers for that thing, you’re allowed to pick your own values. Then you can do arithmetic vs. algebra—and we’re all better at working with real numbers than with variables.

My colleagues and I call this Choosing Smart Numbers. The “Smart” part comes from thinking about what kinds of numbers would work nicely in the problem—make the math a lot less annoying to do.

We usually avoid choosing the numbers 0 or 1 when choosing smart numbers because those numbers can do funny things (e.g., multiplying with a 0 in the mix will always return 0, regardless of the other numbers involved).

And if we have to choose for more than one value, we choose different values. Finally, as I mentioned earlier, we’re looking to choose values that will work nicely in the problem. (Most of the time, this means choosing smallish values.)

Finally, before I start solving, I’m going to ask myself two things: What am I solving for and how much work do I really need to do?

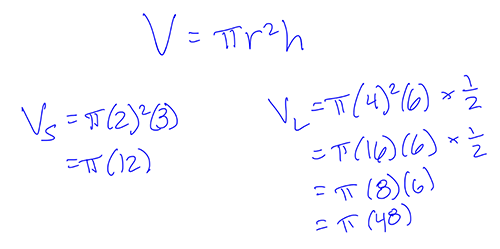

I’m trying to figure out how much oil is in the larger (but only half-full!) cylinder. I know that the full capacity of the smaller cylinder costs $2 and that the oil is charged at the same rate for the larger one. So if I can figure out the relative amount of oil in the larger cylinder, I can figure out how much more (or less) it will cost. For example, if it turns out that the larger cylinder contains twice as much oil as the smaller one, then the cost will also be twice as much.

In the volume formula, the radius has to be squared while the height is only multiplied, so I want to make the radius a lower value. I’m going to choose r = 2 and h = 3.

Use those values to find the relative volumes of the two cylinders. Reminder yet again: The larger cylinder is only half full, so multiply that volume by one-half:

What’s the relative difference between the two? They both contain pi, so ignore that value. The difference is 12 to 48—if you multiply 12 by 4, you get 48.

So the money will also get multiplied by 4: Since the oil in the smaller cylinder costs $2, the oil in the larger one costs (2)(4) = $8. The correct answer is (E).

GMAT Exam 8-Week Study Plan

Reduce your test anxiety by leveraging a solid plan for prep. Follow this link to download the free 8-week study planner.

Understand, plan, solve on GMAT Quant

Whenever you solve any GMAT Problem Solving (PS) or Data Sufficiency (DS) problem, follow the Understand, Plan, Solve process. Print out this summary and keep it by you when you’re studying:

- Glance at the answers (on PS) or the statements (on DS) and the question stem. Anything jump out—an ugly equation, a diagram, an indication that you might be able to estimate, etc?

- Read the question stem. Focus just on understanding what it’s telling you and what it’s asking you.

- Jot down what it’s asking, along with any other useful info (equations, etc.). Don’t solve! Just jot (write or sketch).

- Reflect on what you know so far. Lost? Guess and move on. But if you do understand everything, then consider what your best plan is. Can you estimate anywhere? How heavily? Can you use a real number and just do arithmetic? Is there a way to draw or logic it out? What are they really asking you? This reflection is how I realized I just needed a relative value on the Oil Cylinders problem.

- Organize your thoughts and your scratch work to get set up for the Solve stage. Maybe you need to redraw or add something to your diagram, as I did for Yolanda and Bob. Maybe you need to group the data or equations a little differently, as I did on the Membership problem.

- Don’t have a plan you feel pretty good* about? Forget it—guess and move on. (*You don’t have to feel 100% confident. But you want to feel like it’s a decent plan. If you don’t, let it go.)

- Be systematic. You’re almost there. Write your work down. Don’t try to compress steps or work more quickly than is comfortable for you. Keep your scratch paper organized.

- Don’t do more work than you have to. Estimate when you can. Keep an eye on the answers as you work. Eliminate impossible answers as you go. Stop as soon as only one answer letter is left.

- Be willing to bail. Even if you understand and have a decent plan, you still might get stuck. Don’t start trying some other plan at that point. Something’s not working with this one; guess and go spend your time on a better opportunity later in the test.

Finally, remember your overall goal here: You want to go to business school. The point is not to show how much of a mathematics scholar you are. The point is to learn how to think logically about quant topics—with, yes, some amount of actual textbook math tossed in there.

Actively look for the Logic It Out / Draw It Out / Quick and Dirty approaches. They’ll not only save you time and stress on GMAT Problem Solving and Data Sufficiency, but they’ll also help train your brain for quant discussions in business school and in the boardroom.

Want more strategies to improve your GMAT Problem Solving skills? Sign up for Manhattan Prep’s free GMAT Starter Kit and check out the section on Foundations of Math.

Happy studying!

She’s been teaching people to take standardized tests for more than 20 years and the GMAT is her favorite (shh, don’t tell the other tests). Her favorite teaching moment is when she sees her students’ eyes light up because they suddenly thoroughly get how to approach a particular problem.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Share Podcast

Do You Understand the Problem You’re Trying to Solve?

To solve tough problems at work, first ask these questions.

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

Problem solving skills are invaluable in any job. But all too often, we jump to find solutions to a problem without taking time to really understand the dilemma we face, according to Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg , an expert in innovation and the author of the book, What’s Your Problem?: To Solve Your Toughest Problems, Change the Problems You Solve .

In this episode, you’ll learn how to reframe tough problems by asking questions that reveal all the factors and assumptions that contribute to the situation. You’ll also learn why searching for just one root cause can be misleading.

Key episode topics include: leadership, decision making and problem solving, power and influence, business management.

HBR On Leadership curates the best case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, to help you unlock the best in those around you. New episodes every week.

- Listen to the original HBR IdeaCast episode: The Secret to Better Problem Solving (2016)

- Find more episodes of HBR IdeaCast

- Discover 100 years of Harvard Business Review articles, case studies, podcasts, and more at HBR.org .

HANNAH BATES: Welcome to HBR on Leadership , case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, hand-selected to help you unlock the best in those around you.

Problem solving skills are invaluable in any job. But even the most experienced among us can fall into the trap of solving the wrong problem.

Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg says that all too often, we jump to find solutions to a problem – without taking time to really understand what we’re facing.

He’s an expert in innovation, and he’s the author of the book, What’s Your Problem?: To Solve Your Toughest Problems, Change the Problems You Solve .

In this episode, you’ll learn how to reframe tough problems, by asking questions that reveal all the factors and assumptions that contribute to the situation. You’ll also learn why searching for one root cause can be misleading. And you’ll learn how to use experimentation and rapid prototyping as problem-solving tools.

This episode originally aired on HBR IdeaCast in December 2016. Here it is.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Welcome to the HBR IdeaCast from Harvard Business Review. I’m Sarah Green Carmichael.

Problem solving is popular. People put it on their resumes. Managers believe they excel at it. Companies count it as a key proficiency. We solve customers’ problems.

The problem is we often solve the wrong problems. Albert Einstein and Peter Drucker alike have discussed the difficulty of effective diagnosis. There are great frameworks for getting teams to attack true problems, but they’re often hard to do daily and on the fly. That’s where our guest comes in.

Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg is a consultant who helps companies and managers reframe their problems so they can come up with an effective solution faster. He asks the question “Are You Solving The Right Problems?” in the January-February 2017 issue of Harvard Business Review. Thomas, thank you so much for coming on the HBR IdeaCast .

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Thanks for inviting me.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, I thought maybe we could start by talking about the problem of talking about problem reframing. What is that exactly?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Basically, when people face a problem, they tend to jump into solution mode to rapidly, and very often that means that they don’t really understand, necessarily, the problem they’re trying to solve. And so, reframing is really a– at heart, it’s a method that helps you avoid that by taking a second to go in and ask two questions, basically saying, first of all, wait. What is the problem we’re trying to solve? And then crucially asking, is there a different way to think about what the problem actually is?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, I feel like so often when this comes up in meetings, you know, someone says that, and maybe they throw out the Einstein quote about you spend an hour of problem solving, you spend 55 minutes to find the problem. And then everyone else in the room kind of gets irritated. So, maybe just give us an example of maybe how this would work in practice in a way that would not, sort of, set people’s teeth on edge, like oh, here Sarah goes again, reframing the whole problem instead of just solving it.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: I mean, you’re bringing up something that’s, I think is crucial, which is to create legitimacy for the method. So, one of the reasons why I put out the article is to give people a tool to say actually, this thing is still important, and we need to do it. But I think the really critical thing in order to make this work in a meeting is actually to learn how to do it fast, because if you have the idea that you need to spend 30 minutes in a meeting delving deeply into the problem, I mean, that’s going to be uphill for most problems. So, the critical thing here is really to try to make it a practice you can implement very, very rapidly.

There’s an example that I would suggest memorizing. This is the example that I use to explain very rapidly what it is. And it’s basically, I call it the slow elevator problem. You imagine that you are the owner of an office building, and that your tenants are complaining that the elevator’s slow.

Now, if you take that problem framing for granted, you’re going to start thinking creatively around how do we make the elevator faster. Do we install a new motor? Do we have to buy a new lift somewhere?

The thing is, though, if you ask people who actually work with facilities management, well, they’re going to have a different solution for you, which is put up a mirror next to the elevator. That’s what happens is, of course, that people go oh, I’m busy. I’m busy. I’m– oh, a mirror. Oh, that’s beautiful.

And then they forget time. What’s interesting about that example is that the idea with a mirror is actually a solution to a different problem than the one you first proposed. And so, the whole idea here is once you get good at using reframing, you can quickly identify other aspects of the problem that might be much better to try to solve than the original one you found. It’s not necessarily that the first one is wrong. It’s just that there might be better problems out there to attack that we can, means we can do things much faster, cheaper, or better.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, in that example, I can understand how A, it’s probably expensive to make the elevator faster, so it’s much cheaper just to put up a mirror. And B, maybe the real problem people are actually feeling, even though they’re not articulating it right, is like, I hate waiting for the elevator. But if you let them sort of fix their hair or check their teeth, they’re suddenly distracted and don’t notice.

But if you have, this is sort of a pedestrian example, but say you have a roommate or a spouse who doesn’t clean up the kitchen. Facing that problem and not having your elegant solution already there to highlight the contrast between the perceived problem and the real problem, how would you take a problem like that and attack it using this method so that you can see what some of the other options might be?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Right. So, I mean, let’s say it’s you who have that problem. I would go in and say, first of all, what would you say the problem is? Like, if you were to describe your view of the problem, what would that be?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: I hate cleaning the kitchen, and I want someone else to clean it up.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: OK. So, my first observation, you know, that somebody else might not necessarily be your spouse. So, already there, there’s an inbuilt assumption in your question around oh, it has to be my husband who does the cleaning. So, it might actually be worth, already there to say, is that really the only problem you have? That you hate cleaning the kitchen, and you want to avoid it? Or might there be something around, as well, getting a better relationship in terms of how you solve problems in general or establishing a better way to handle small problems when dealing with your spouse?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Or maybe, now that I’m thinking that, maybe the problem is that you just can’t find the stuff in the kitchen when you need to find it.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Right, and so that’s an example of a reframing, that actually why is it a problem that the kitchen is not clean? Is it only because you hate the act of cleaning, or does it actually mean that it just takes you a lot longer and gets a lot messier to actually use the kitchen, which is a different problem. The way you describe this problem now, is there anything that’s missing from that description?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: That is a really good question.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Other, basically asking other factors that we are not talking about right now, and I say those because people tend to, when given a problem, they tend to delve deeper into the detail. What often is missing is actually an element outside of the initial description of the problem that might be really relevant to what’s going on. Like, why does the kitchen get messy in the first place? Is it something about the way you use it or your cooking habits? Is it because the neighbor’s kids, kind of, use it all the time?

There might, very often, there might be issues that you’re not really thinking about when you first describe the problem that actually has a big effect on it.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: I think at this point it would be helpful to maybe get another business example, and I’m wondering if you could tell us the story of the dog adoption problem.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Yeah. This is a big problem in the US. If you work in the shelter industry, basically because dogs are so popular, more than 3 million dogs every year enter a shelter, and currently only about half of those actually find a new home and get adopted. And so, this is a problem that has persisted. It’s been, like, a structural problem for decades in this space. In the last three years, where people found new ways to address it.

So a woman called Lori Weise who runs a rescue organization in South LA, and she actually went in and challenged the very idea of what we were trying to do. She said, no, no. The problem we’re trying to solve is not about how to get more people to adopt dogs. It is about keeping the dogs with their first family so they never enter the shelter system in the first place.

In 2013, she started what’s called a Shelter Intervention Program that basically works like this. If a family comes and wants to hand over their dog, these are called owner surrenders. It’s about 30% of all dogs that come into a shelter. All they would do is go up and ask, if you could, would you like to keep your animal? And if they said yes, they would try to fix whatever helped them fix the problem, but that made them turn over this.

And sometimes that might be that they moved into a new building. The landlord required a deposit, and they simply didn’t have the money to put down a deposit. Or the dog might need a $10 rabies shot, but they didn’t know how to get access to a vet.

And so, by instigating that program, just in the first year, she took her, basically the amount of dollars they spent per animal they helped went from something like $85 down to around $60. Just an immediate impact, and her program now is being rolled out, is being supported by the ASPCA, which is one of the big animal welfare stations, and it’s being rolled out to various other places.

And I think what really struck me with that example was this was not dependent on having the internet. This was not, oh, we needed to have everybody mobile before we could come up with this. This, conceivably, we could have done 20 years ago. Only, it only happened when somebody, like in this case Lori, went in and actually rethought what the problem they were trying to solve was in the first place.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, what I also think is so interesting about that example is that when you talk about it, it doesn’t sound like the kind of thing that would have been thought of through other kinds of problem solving methods. There wasn’t necessarily an After Action Review or a 5 Whys exercise or a Six Sigma type intervention. I don’t want to throw those other methods under the bus, but how can you get such powerful results with such a very simple way of thinking about something?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: That was something that struck me as well. This, in a way, reframing and the idea of the problem diagnosis is important is something we’ve known for a long, long time. And we’ve actually have built some tools to help out. If you worked with us professionally, you are familiar with, like, Six Sigma, TRIZ, and so on. You mentioned 5 Whys. A root cause analysis is another one that a lot of people are familiar with.

Those are our good tools, and they’re definitely better than nothing. But what I notice when I work with the companies applying those was those tools tend to make you dig deeper into the first understanding of the problem we have. If it’s the elevator example, people start asking, well, is that the cable strength, or is the capacity of the elevator? That they kind of get caught by the details.

That, in a way, is a bad way to work on problems because it really assumes that there’s like a, you can almost hear it, a root cause. That you have to dig down and find the one true problem, and everything else was just symptoms. That’s a bad way to think about problems because problems tend to be multicausal.

There tend to be lots of causes or levers you can potentially press to address a problem. And if you think there’s only one, if that’s the right problem, that’s actually a dangerous way. And so I think that’s why, that this is a method I’ve worked with over the last five years, trying to basically refine how to make people better at this, and the key tends to be this thing about shifting out and saying, is there a totally different way of thinking about the problem versus getting too caught up in the mechanistic details of what happens.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: What about experimentation? Because that’s another method that’s become really popular with the rise of Lean Startup and lots of other innovation methodologies. Why wouldn’t it have worked to, say, experiment with many different types of fixing the dog adoption problem, and then just pick the one that works the best?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: You could say in the dog space, that’s what’s been going on. I mean, there is, in this industry and a lot of, it’s largely volunteer driven. People have experimented, and they found different ways of trying to cope. And that has definitely made the problem better. So, I wouldn’t say that experimentation is bad, quite the contrary. Rapid prototyping, quickly putting something out into the world and learning from it, that’s a fantastic way to learn more and to move forward.

My point is, though, that I feel we’ve come to rely too much on that. There’s like, if you look at the start up space, the wisdom is now just to put something quickly into the market, and then if it doesn’t work, pivot and just do more stuff. What reframing really is, I think of it as the cognitive counterpoint to prototyping. So, this is really a way of seeing very quickly, like not just working on the solution, but also working on our understanding of the problem and trying to see is there a different way to think about that.

If you only stick with experimentation, again, you tend to sometimes stay too much in the same space trying minute variations of something instead of taking a step back and saying, wait a minute. What is this telling us about what the real issue is?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, to go back to something that we touched on earlier, when we were talking about the completely hypothetical example of a spouse who does not clean the kitchen–

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Completely, completely hypothetical.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Yes. For the record, my husband is a great kitchen cleaner.

You started asking me some questions that I could see immediately were helping me rethink that problem. Is that kind of the key, just having a checklist of questions to ask yourself? How do you really start to put this into practice?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: I think there are two steps in that. The first one is just to make yourself better at the method. Yes, you should kind of work with a checklist. In the article, I kind of outlined seven practices that you can use to do this.

But importantly, I would say you have to consider that as, basically, a set of training wheels. I think there’s a big, big danger in getting caught in a checklist. This is something I work with.

My co-author Paddy Miller, it’s one of his insights. That if you start giving people a checklist for things like this, they start following it. And that’s actually a problem, because what you really want them to do is start challenging their thinking.

So the way to handle this is to get some practice using it. Do use the checklist initially, but then try to step away from it and try to see if you can organically make– it’s almost a habit of mind. When you run into a colleague in the hallway and she has a problem and you have five minutes, like, delving in and just starting asking some of those questions and using your intuition to say, wait, how is she talking about this problem? And is there a question or two I can ask her about the problem that can help her rethink it?

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Well, that is also just a very different approach, because I think in that situation, most of us can’t go 30 seconds without jumping in and offering solutions.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Very true. The drive toward solutions is very strong. And to be clear, I mean, there’s nothing wrong with that if the solutions work. So, many problems are just solved by oh, you know, oh, here’s the way to do that. Great.

But this is really a powerful method for those problems where either it’s something we’ve been banging our heads against tons of times without making progress, or when you need to come up with a really creative solution. When you’re facing a competitor with a much bigger budget, and you know, if you solve the same problem later, you’re not going to win. So, that basic idea of taking that approach to problems can often help you move forward in a different way than just like, oh, I have a solution.

I would say there’s also, there’s some interesting psychological stuff going on, right? Where you may have tried this, but if somebody tries to serve up a solution to a problem I have, I’m often resistant towards them. Kind if like, no, no, no, no, no, no. That solution is not going to work in my world. Whereas if you get them to discuss and analyze what the problem really is, you might actually dig something up.

Let’s go back to the kitchen example. One powerful question is just to say, what’s your own part in creating this problem? It’s very often, like, people, they describe problems as if it’s something that’s inflicted upon them from the external world, and they are innocent bystanders in that.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Right, or crazy customers with unreasonable demands.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Exactly, right. I don’t think I’ve ever met an agency or consultancy that didn’t, like, gossip about their customers. Oh, my god, they’re horrible. That, you know, classic thing, why don’t they want to take more risk? Well, risk is bad.

It’s their business that’s on the line, not the consultancy’s, right? So, absolutely, that’s one of the things when you step into a different mindset and kind of, wait. Oh yeah, maybe I actually am part of creating this problem in a sense, as well. That tends to open some new doors for you to move forward, in a way, with stuff that you may have been struggling with for years.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, we’ve surfaced a couple of questions that are useful. I’m curious to know, what are some of the other questions that you find yourself asking in these situations, given that you have made this sort of mental habit that you do? What are the questions that people seem to find really useful?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: One easy one is just to ask if there are any positive exceptions to the problem. So, was there day where your kitchen was actually spotlessly clean? And then asking, what was different about that day? Like, what happened there that didn’t happen the other days? That can very often point people towards a factor that they hadn’t considered previously.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: We got take-out.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: S,o that is your solution. Take-out from [INAUDIBLE]. That might have other problems.

Another good question, and this is a little bit more high level. It’s actually more making an observation about labeling how that person thinks about the problem. And what I mean with that is, we have problem categories in our head. So, if I say, let’s say that you describe a problem to me and say, well, we have a really great product and are, it’s much better than our previous product, but people aren’t buying it. I think we need to put more marketing dollars into this.

Now you can go in and say, that’s interesting. This sounds like you’re thinking of this as a communications problem. Is there a different way of thinking about that? Because you can almost tell how, when the second you say communications, there are some ideas about how do you solve a communications problem. Typically with more communication.

And what you might do is go in and suggest, well, have you considered that it might be, say, an incentive problem? Are there incentives on behalf of the purchasing manager at your clients that are obstructing you? Might there be incentive issues with your own sales force that makes them want to sell the old product instead of the new one?

So literally, just identifying what type of problem does this person think about, and is there different potential way of thinking about it? Might it be an emotional problem, a timing problem, an expectations management problem? Thinking about what label of what type of problem that person is kind of thinking as it of.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: That’s really interesting, too, because I think so many of us get requests for advice that we’re really not qualified to give. So, maybe the next time that happens, instead of muddying my way through, I will just ask some of those questions that we talked about instead.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: That sounds like a good idea.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: So, Thomas, this has really helped me reframe the way I think about a couple of problems in my own life, and I’m just wondering. I know you do this professionally, but is there a problem in your life that thinking this way has helped you solve?

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: I’ve, of course, I’ve been swallowing my own medicine on this, too, and I think I have, well, maybe two different examples, and in one case somebody else did the reframing for me. But in one case, when I was younger, I often kind of struggled a little bit. I mean, this is my teenage years, kind of hanging out with my parents. I thought they were pretty annoying people. That’s not really fair, because they’re quite wonderful, but that’s what life is when you’re a teenager.

And one of the things that struck me, suddenly, and this was kind of the positive exception was, there was actually an evening where we really had a good time, and there wasn’t a conflict. And the core thing was, I wasn’t just seeing them in their old house where I grew up. It was, actually, we were at a restaurant. And it suddenly struck me that so much of the sometimes, kind of, a little bit, you love them but they’re annoying kind of dynamic, is tied to the place, is tied to the setting you are in.

And of course, if– you know, I live abroad now, if I visit my parents and I stay in my old bedroom, you know, my mother comes in and wants to wake me up in the morning. Stuff like that, right? And it just struck me so, so clearly that it’s– when I change this setting, if I go out and have dinner with them at a different place, that the dynamic, just that dynamic disappears.

SARAH GREEN CARMICHAEL: Well, Thomas, this has been really, really helpful. Thank you for talking with me today.

THOMAS WEDELL-WEDELLSBORG: Thank you, Sarah.

HANNAH BATES: That was Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg in conversation with Sarah Green Carmichael on the HBR IdeaCast. He’s an expert in problem solving and innovation, and he’s the author of the book, What’s Your Problem?: To Solve Your Toughest Problems, Change the Problems You Solve .

We’ll be back next Wednesday with another hand-picked conversation about leadership from the Harvard Business Review. If you found this episode helpful, share it with your friends and colleagues, and follow our show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. While you’re there, be sure to leave us a review.

We’re a production of Harvard Business Review. If you want more podcasts, articles, case studies, books, and videos like this, find it all at HBR dot org.

This episode was produced by Anne Saini, and me, Hannah Bates. Ian Fox is our editor. Music by Coma Media. Special thanks to Maureen Hoch, Adi Ignatius, Karen Player, Ramsey Khabbaz, Nicole Smith, Anne Bartholomew, and you – our listener.

See you next week.

- Subscribe On:

Latest in this series

This article is about leadership.

- Decision making and problem solving

- Power and influence

- Business management

Partner Center

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.1: Simple Interest: Principal, Rate, Time

Simple interest: principal, rate, time, simple interest.

In a simple interest environment, you calculate interest solely on the amount of money at the beginning of the transaction (amount borrowed or lent).

Assume $1,000 is placed into an account with 12% simple interest for a period of 12 months. For the entire term of this transaction, the amount of money in the account always equals $1,000. During this period, interest accrues at a rate of 12%, but the interest is never placed into the account. When the transaction ends after 12 months, the $120 of interest and the initial $1,000 are then combined to total $1,120.

A loan or investment always involves two parties—one giving and one receiving. No matter which party you are in the transaction, the amount of interest remains unchanged. The only difference lies in whether you are earning or paying the interest.

The Formula

[latex]\colorbox{LightGray}{Formula 8.1}\; \color{BlueViolet}{\text{Simple Interest:}\; I=Prt}[/latex]

I is Interest Amount. The interest amount is the dollar amount of interest that is paid or received.

P is Present Value or Principal . The present value is the amount borrowed or invested at the beginning of a period.

r is Simple Interest Rate. The interest rate is the rate of interest that is charged or earned during a specified time period. It is expressed as a percent.

t is Time Period. The time period or term is the length of the financial transaction for which interest is charged or earned.

Important Notes

Recall that algebraic equations require all terms to be expressed with a common unit. This principle remains true for Formula 8.1 , particularly with regard to the interest rate and the time period. For example, if you have a 3% annual interest rate for nine months, then either

- The time needs to be expressed annually as [latex]\frac{9}{12}[/latex] of a year to match the yearly interest rate, or

- The interest rate needs to be expressed monthly as [latex]\frac{3\%}{12}=0.25\%[/latex] per month to match the number of months. It does not matter which you do so long as you express both interest rate and time in the same unit. If one of these two variables is your algebraic unknown, the unit of the known variable determines the unit of the unknown variable. For example, assume that you are solving Formula 8.1 for the time period. If the interest rate used in the formula is annual, then the time period is expressed in number of years.

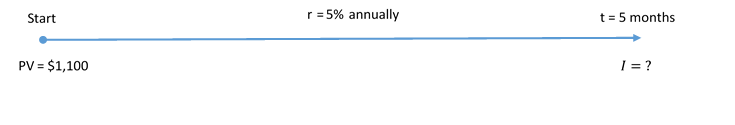

Example 8.1.1: How Much Interest is Owed?

Julio borrowed $1,100 from Maria five months ago. When he first borrowed the money, they agreed that he would pay Maria 5% simple interest. If Julio pays her back today, how much interest does he owe her?

Step 1 : Given information:

P = $1,100; r = 5%; per year; t = 5 months

Step 2 : The rate is annual, and the time is in months. Convert the time period from months to years; [latex]t=\frac{5}{12}[/latex]

Step 3 : Solve for the amount of interest, I.

[latex]\begin{align} I&=Prt\\ &=\$1,\!100 \times 5\% \times \frac{5}{12}\\ &=\$1,\!100 \times 0.05 \times 0.41\overline{6}\\ &=\$22.92 \end{align}[/latex]

For Julio to pay back Maria, he must reimburse her for the $1,100 principal borrowed plus an additional $22.92 of simple interest as per their agreement.

Solving for P, r or t

Four variables are involved in the simple interest formula , which means that any three can be known, requiring you to solve for the fourth missing variable. To reduce formula clutter, the triangle technique illustrated in the video below will help you remember how to rearrange the simple interest formula as needed.

Concept Check

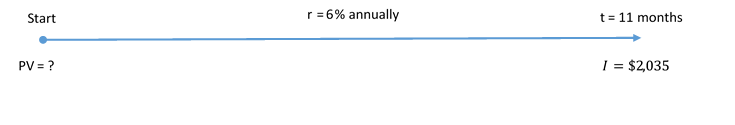

Example 8.1.2: what did you start with.

What amount of money invested at 6% annual simple interest for 11 months earns $2,035 of interest?

Step 1 : Given information:

r = 6%; t = 11 months; I = $2,035

Step 2 : Convert the time from months to an annual basis to match the interest rate; [latex]t=\frac{11}{12}[/latex]

Step 3: Solve for the present value, P.

[latex]\begin{align} P&=\frac{I}{rt}\\ &=\frac{\$2,\!035}{6\% \times \frac{11}{12}}\\ &=\frac{\$2,\!035}{0.06 \times 0.91\overline{6}}\\ &=\$37,\!000 \end{align}[/latex]

To generate $2,035 of simple interest at 6% over a time frame of 11 months, $37,000 must be invested.

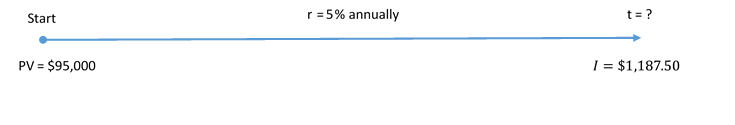

Example 8.1.3: How long?

For how many months must $95,000 be invested to earn $1,187.50 of simple interest at an interest rate of 5%?

P = $95,000; I = $1,187.50; r = 5%; per year

Step 2: Convert the interest rate to a “per month” format; [latex]r=\frac{0.05}{12}[/latex]

Step 3: Solve for the time period, t.

[latex]\begin{align} t&=\frac{I}{Pr}\\ &=\frac{\$1,\!187.50}{\$95,\!000 \times \frac{0.05}{12}}\\ &=\frac{\$1,\!187.50}{\$95,\!000 \times 0.0041\overline{6}}\\ &=3 \; \text {months} \end{align}[/latex]

For $95,000 to earn $1,187.50 at 5% simple interest, it must be invested for a three-month period.

In each of the exercises that follow, try them on your own. Full solutions are available should you get stuck.

- If you want to earn $1,000 of simple interest at a rate of 7% in a span of five months, how much money must you invest? ( Answer: 34,285.71)

- If you placed $2,000 into an investment account earning 3% simple interest, how many months does it take for you to have $2,025 in your account? (Answer: 5 months)

- A $3,500 investment earned $70 of interest over the course of six months. What annual rate of simple interest did the investment earn? ( Answer: 4%)

Time and Dates

In the examples of simple interest so far, the time period was given in months. While this is convenient in many situations, financial institutions and organizations calculate interest based on the exact number of days in the transaction, which changes the interest amount. To illustrate this, assume you had money saved for the entire months of July and August, where [latex]t = \frac{2}{12}[/latex] or [latex]t = 0.16666...=0.1\overline{6}[/latex] of a year. However, if you use the exact number of days, the 31 days in July and 31 days in August total 62 days. In a 365-day year that is [latex]t =\frac{62}{365}[/latex] or t = 0.169863 of a year. Notice a difference of 0.003196 (0.169863 – 0.16) occurs. Therefore, to be precise in performing simple interest calculations, you must calculate the exact number of days involved in the transaction.

Using The BA 2+ Plus Date Function to Calculate the Exact Number of Days

In the video below we’ll demonstrate how to use the BA2+ Date Function.

When solving for t, decimals may appear in your solution. For example, if calculating t in days, the answer may show up as 45.9978 or 46.0023 days; however, interest is calculated only on complete days. This occurs because the interest amount (I) used in the calculation has been rounded off to two decimals. Since the interest amount is imprecise, the calculation of t is imprecise. When this occurs, round t off to the nearest integer.

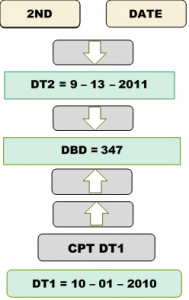

Example 8.1.4: Time Using Dates

On September 13, 2011, Aladdin decided to pay back the Genie on his loan of $15,000 at 9% simple interest. If he paid the Genie the principal plus $1,283.42 of interest, on what day did he borrow the money from the Genie?

Step 1: Given variables: P = $15,000; I = $1,283.42; r = 9% per year; End Date = September 13, 2011

Step 2: The time is in days, but the rate is annual. Convert the rate to a daily rate; [latex]r=\frac{9\%}{365}[/latex]

Step 3: Solve for the time, t

[latex]\begin{align} t&=\frac{I}{Pr}\\ &=\frac{\$1,\!283.42}{\$15,\!000 \times \frac{0.09}{365}}\\ &= 346.998741=347\; \text{days} \end{align}[/latex]

Step 4 : Use the DATE function to calculate the start date (DT1). Use the time in days.

Calculator Instructions

- Brynn borrowed $25,000 at 1% per month from a family friend to start her entrepreneurial venture on December 2, 2011. If she paid back the loan on June 16, 2012, how much simple interest did she pay? ( Answer: 1,619.18)

- If $6,000 principal plus $132.90 of simple interest was withdrawn on August 14, 2011, from an investment earning 5.5% interest, on what day was the money invested? ( Answer: March 20, 2011)

Image Descriptions

Figure 8.1.1: Timeline showing PV =$1,100 at the Start with an arrow pointing to the end (right) where I = ? when t=5 months. r = 5% annually [ Back to Figure 8.1.1 ]

Figure 8.1.2: Timeline showing PV = ? at the Start with an arrow pointing to the end (right) where I = $2,035 when t=11 months. r = 6% annually [ Back to Figure 8.1.2 ]

Figure 8.1.3: Timeline showing PV =$95,000 at the Start with an arrow pointing to the end (right) where I = $1,187.50 when t=?. r = 5% annually [ Back to Figure 8.1.3 ]

Figure 8.1.4: Calculator Instructions to use the Date Function. Instructions are: 2ND DATE, Down Arrow, DT2 = 9-13-2011, Down Arrow, DBD = 347, Up Arrow, Up Arrow, CPT DT1, DT1 = 10-01-2010 [ Back to Figure 8.1.4 ]

Business Math: A Step-by-Step Handbook Abridged Copyright © 2022 by Sanja Krajisnik; Carol Leppinen; and Jelena Loncar-Vines is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Directories

Search form

You are here.

- Summer 2024

MATH 111 AA: Algebra with Applications

- News Feed

- Alumni Update

- Mailing List

- Share full article

For more audio journalism and storytelling, download New York Times Audio , a new iOS app available for news subscribers.

- April 10, 2024 • 22:49 Trump’s Abortion Dilemma

- April 9, 2024 • 30:48 How Tesla Planted the Seeds for Its Own Potential Downfall

- April 8, 2024 • 30:28 The Eclipse Chaser

- April 7, 2024 The Sunday Read: ‘What Deathbed Visions Teach Us About Living’

- April 5, 2024 • 29:11 An Engineering Experiment to Cool the Earth

- April 4, 2024 • 32:37 Israel’s Deadly Airstrike on the World Central Kitchen

- April 3, 2024 • 27:42 The Accidental Tax Cutter in Chief