Nigerian Literature: A Rich Cultural Heritage

- Post author: Applied Worldwide Nigeria

- Post published: June 30, 2023

- Post category: People

Nigeria has a vibrant literary tradition that reflects the country’s diverse history, culture, and identity. Nigerian literature encompasses a range of genres, from novels and short stories to poetry and drama. It has produced a number of celebrated writers who have gained international recognition for their works. In this blog, we will explore the origins and evolution of Nigerian literature, its major themes and genres, and its significant contributions to the world of literature.

Origins and Evolution of Nigerian Literature

Nigerian literature has a rich and diverse history that spans several centuries. Oral literature, which was the primary form of literary expression in Nigeria before the advent of written literature, has its roots in the country’s diverse ethnic and linguistic communities. Folk tales, legends, proverbs, and songs were the primary means of transmitting cultural values and traditions from one generation to another.

The advent of written literature in Nigeria can be traced back to the colonial period. The first literary works in Nigeria were produced by European missionaries and explorers who wrote about their experiences in the country. The first Nigerian novel, “The Palm-Wine Drinkard” by Amos Tutuola , was published in 1952. It was followed by other notable works such as “Things Fall Apart” by Chinua Achebe and “The Interpreters” by Wole Soyinka.

Nigerian Literature Themes and Genres

Nigerian literature addresses a wide range of themes that reflect the country’s complex social, political, and economic realities. Some of the prominent themes in Nigerian literature include colonialism, postcolonialism, identity, corruption, gender, and social injustice. These themes are explored through various genres such as novels, poetry, drama, and short stories.

Novels are the most popular genre in Nigerian literature. They provide a medium for exploring complex social and political issues. And are often used to critique government policies and societal norms. Chinua Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart,” for instance, explores the impact of colonialism on Nigerian society and culture. It depicts the struggle of a traditional Igbo community to maintain its cultural identity in the face of colonialism and Christianity.

Poetry is another popular genre in Nigerian literature. It is used to explore themes such as love, nature, and social issues. Some notable Nigerian poets include Christopher Okigbo, Wole Soyinka, and Chinua Achebe. Okigbo’s poetry often dealt with the themes of war, love, and African identity. While Soyinka’s poetry explored issues such as political corruption and social injustice.

Drama is another significant genre in Nigerian literature. It is used to explore social and political issues and to critique government policies and societal norms. Wole Soyinka’s play, “Death and the King’s Horseman,” for instance, explores the tension between traditional African beliefs and British colonialism. It depicts the conflict between a traditional Yoruba community and British colonial authorities over the burial of the king’s horseman.

Nigerian Literature and History

Nigerian literature has been greatly influenced by the country’s history, culture, and politics. From the pre-colonial era to the present day, Nigerian literature has undergone numerous transformations, reflecting the changing social, economic, and political realities of the country. In this article, we will explore the development of Nigerian literature, its key themes and genres, and some of its most prominent writers.

Pre-Colonial Era

Before the arrival of Europeans in Nigeria, there existed a rich tradition of oral literature that was passed down from generation to generation. These oral traditions, which include myths, legends, and folktales, were used to teach moral lessons and preserve the history of the community. One of the most well-known examples of pre-colonial Nigerian literature is the epic poem, “The Song of Ogun”. This poem tells the story of the Yoruba god of iron and war.

Colonial Era

The colonial era marked a significant turning point in Nigerian literature. With the arrival of European missionaries and administrators, English became the dominant language of education and communication. Many Nigerian writers, such as Amos Tutuola and Chinua Achebe, began to write in English. Using the language to challenge colonial stereotypes and highlight the struggles of ordinary Nigerians.

One of the most influential works of Nigerian literature from this period is Chinua Achebe’s novel, “Things Fall Apart”. It tells the story of Okonkwo, a traditional Igbo leader whose life is disrupted by the arrival of European colonizers. Achebe’s novel is often cited as a landmark in postcolonial literature and has been translated into over 50 languages.

Post-Independence Era

Nigeria gained independence from Britain in 1960, ushering in a period of political and social upheaval. Nigerian writers continued to use literature as a means of exploring the complexities of Nigerian society. With many focusing on themes such as corruption, social inequality, and the impact of colonialism.

One of the most notable writers of this period is Wole Soyinka , who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986. Soyinka’s works, such as “The Lion and the Jewel” and “Death and the King’s Horseman,” are known for their political and social commentary. As well as their use of traditional Yoruba culture and mythology.

Contemporary Nigerian Literature

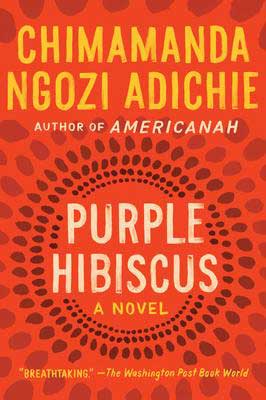

In recent years, Nigerian literature has gained international recognition, with many Nigerian writers winning prestigious awards and accolades. Some of the most notable contemporary Nigerian writers include Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Who has won numerous awards for her novels “Purple Hibiscus,” “Half of a Yellow Sun,” and “Americanah”; and Ben Okri, whose novel “The Famished Road” won the Booker Prize in 1991.

Contemporary Nigerian literature continues to explore themes such as identity, race, gender, and globalization, reflecting the complex realities of a rapidly changing society. Many writers are also experimenting with new forms and styles of writing, such as graphic novels, poetry collections, and experimental fiction.

Nigerian literature has a rich and diverse history, reflecting the complexities of Nigerian society and its ongoing struggles for independence, social justice, and equality. From the pre-colonial era to the present day, Nigerian writers have used literature to challenge stereotypes, explore political and social issues, and celebrate the cultural richness of the country. With the growing international recognition of Nigerian literature, the future looks bright for this dynamic and constantly evolving field.

Share this article:

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

You Might Also Like

Social Media Manager of the Decade: Abdulazeez Omope

What Queen Elizabeth II’s Death Exposes about Nigeria

Nigeria after the Lekki Massacre of 20.10.20

Youths and Political Thuggery in Nigeria and its Consequences

Tips and Strategies For Effective Remote Work

Attaining Justice in Nigeria: Organizing for a Just Nation

The rise of incels in nigeria: who are incels.

- Search for:

You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

My Top Ten Nigerian Books

I’ve always been a huge fan of Nigerian literature. A few years back I even went on a course to learn Igbo. I started seriously reading Nigerian literature during my PhD studies on Nigerian and Zimbabwean contemporary fiction—a course, incidentally, which I never finished, because I began writing my own novel instead. The brevity, freshness, and unique storytelling style of Nigerian authors made me fall in love with the country’s literature and, in turn, taught me to believe in myself and my own writing style.

With over 500 languages and over 240 ethnic groups, Nigeria is a mesmerising place for any writer to write about, and the country boasts some of the greatest authors in African literature. The first person from an African country to win the Nobel Prize for Literature was Nigerian playwright and poet Wole Soyinka in 1986. Nigerian Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart , published in 1958, is still one of the most widely read book in African literature. The first African author to win the Orange Prize for Fiction was Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie with her novel Half of a Yellow Sun in 2007, and the first Booker Prize awarded to an African author went to Nigerian Ben Okri’s The Famished Road in 1991. Evidently, Nigeria has a very rich literary tradition, which continues to this day.

Here are some of my recent favourites:

Jude Dibia’s Blackbird (2011) A powerful novel about love, jealousy, and the fragility of life. Dibia caught my attention with his first book, Walking With Shadows , a brave and sensitive novel about homosexuality in Nigeria. Blackbird goes further in exploring what makes us human, how far we are prepared to go to for the people we love, and whether the sacrifices we make are ever truly worth it.

Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani’s I Do Not Come To You By Chance (2010) Have you ever wondered who’s really behind all those Nigerian scam emails promising you untold riches? Meet Kingsley Ibe and the dangerous yet fascinating world of Nigerian 419 scams. This book is incredibly funny—at times I laughed out loud reading it—but it also shows the industry’s darker side, exploring why people might decide to enter the criminal world in the first place.

Helon Habila’s Oil on Water (2011) Oil on Water is Habila’s third novel and tells the story of two journalists in pursuit of the kidnapped European wife of an oil executive. It is a pessimistic but must-read novel that highlights the ongoing tragedy of the environmental degradation of the Niger delta and the Ogoni people.

Chika Unigwe’s On Black Sisters Street (2010) An unsettling novel about four Nigerian prostitutes living in Antwerp. Before she wrote it, Unigwe approached a number of women working as prostitutes to tell her their life stories, and the book reflects this underlying reality in its raw and vivid language. Unigwe tells a story of courage and hope and manages not to stereotype her female characters as victims.

Mohammed Umar’s Amina (2006) Set in northern Nigeria, Amina is one of those rare books which offer a glimpse into a world under Islamic rule. This novel has been translated to over 40 languages, and it tells the story of one woman’s transformation into a leader of a movement to bring much needed social change. There are very few Northern Nigerians who write in English and Amina is a great place to start.

Lola Shoneyin’s The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives (2011) Baba Segi has four wives. But his fourth, the young, ambitious and college-educated Bolanle, has still not had a baby. Imagine Nigerian Big Love, but so much better!

Chris Abani’s The Virgin of Flames (2007) Set in East Los Angeles the book follows part-Salvadorian, part-Nigerian mural artist Black and his obsession with transsexual stripper Sweet Girl. Black’s friends include Iggy the tattoo artists and Bomboy the Rwandan butcher. Unforgettable characters that will keep you awake at night.

Sarah Ladipo Manyika’s In Dependence (2008) I fell in love with Manyika’s characters: Tayo, a Nigerian on scholarship in Oxford and Vanessa, a British colonial officer’s daughter. A touching and bittersweet cross-cultural love story set in the 1960s.

Richard Ali’s City of Memories (2012) Ali’s first novel tackles the big question of what love really means, set during the time of religious and ethnic upheavals in Northern-Central Nigeria. A beautiful book of self-discovery by a young author to watch.

Uwem Akpan’s Say You Are One of Them (2010) A collection of five short stories, each written from the point of view of a child, and each set in a different African country. It is not an easy book to read, and the stories will haunt you long after you finish them.

About A. M. Bakalar

A. M. Bakalar was born and raised in Poland. She lived in Germany, France, Sicily and Canada before she moved to the UK in 2004. Her first novel, Madame Mephisto , was among readers’ recommendations for the Guardian First Book Award. She is the first Polish woman to publish a novel in English since Poland joined the EU in 2004. A. M. Bakalar lives with her partner—a drum and bass musician—in London. She is currently at work on her second novel.

- More Posts(7)

Nigerian novels Nigerian writers reading list

You may also like

2023: the year of translated fiction, i am woman. hear what i want for christmas, the booker prize: controversies, diversity, and the power of recognition, other people’s epiphanies.

This is an amazing list! I shall now proceed on a reading pilgrimage through it. Read a couple and they are my best books ever (I do not come to by chance, Oil on water, Baba Segi’s wives and Say you are one of them) and have been looking for more Nigerian books since.

My Top Ten Nigerian Books | Litro https://t.co/MZIQipGQUE #Nigeria

What about ‘Biyi Bandele-Thomas? He wrote a number of stunning novels such as The Man Who Came in From the Back of Beyond, The Sympathetic Undertaker and Other Dreams, The Street and Burma Boy.

Triatlantic Books, founded in 1996 with links in the US and Nigeria, is on a mission to make a difference by bringing authors across the Atlantic to an ever wider interaction through the world of books.

Our commitment is to works that contribute to knowledge and to the future of a Global African civilization, with emphasis on policy-relevant research and science, literature, art and culture, politics, biography and nation-building, instructional, professional and informational how-to books and other works of relevance.

Our authors get the chance to be pitched to International reprint and translation rights experts and we keep titles in print as long as there is an interested audience. Generous royalties & terms, once accepted. Our books are distributed via various sources, from Amazon.com and B&N to conventional bookstore distribution networks.

At Triatlantic Books, our task is that of the total publishing function, namely:

Acquisitions and Editorial review;

Layout graphics and cover design;

Copyright, ISBN, and other requirements & industry specifications;

Press releases, announcements and search for reviews;

Marketing – getting out to bookstores

Online promotion, various outlets

Participating with author for book signing events – readings, launchings, etc;

Open to International reprint and translation rights

Generous royalties and terms

For more information visit us @ http://www.triatlanticbooksonline.com

Regards,Triatlantic Books Ltd

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

New online writing courses

Privacy overview.

British Council

The changing face of nigerian literature, by emma shercliff, 09 december 2015 - 16:54.

Emma Shercliff

How is Nigeria's literary scene changing? Emma Shercliff, a publisher based in the nation's capital, Abuja, takes a look.

Despite a vibrant literary scene, Nigerian-based authors are not well known outside Nigeria

When I was last in the UK, I conducted a survey among dozens of my friends, colleagues and acquaintances in the UK publishing industry, asking, 'How many Nigerian authors can you name?'. Most people managed to identify Chinua Achebe, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie or Ben Okri, but not a single one of them mentioned an author based in Nigeria.

In recent times, the most widely read Nigerian novelists writing in English are those such as Helon Habila and Teju Cole, who now reside in the West. Despite first being discovered and published by Nigerian publishing houses, they have received affirmation at home by being published in the UK and US. However, there is an incredibly vibrant literary scene in Nigeria itself. It is gaining recognition, and a new BBC radio documentary, Writing a New Nigeria , profiles 15 authors, all of whom currently reside and write in the country.

Nigerian-based publishing houses are providing an outlet for new writers

Nigerian literary greats Amos Tutuola and Chinua Achebe were first published by UK publishing houses, Faber and Heinemann, in 1952 and 1958 respectively. This was the beginning of a long tradition of novels written by African authors being published in the West before being imported back to the author's country of origin. The celebrated Heinemann African Writers Series, established in London in 1962, had an enormous influence on the (predominantly male-authored) African literary canon, publishing more than 350 titles between 1962 and 2000. Popular novels, such as those published as part of Macmillan's Pacesetters series, were widely distributed and read throughout Africa in the 1980s and 1990s, although they were actually conceived, edited and illustrated in the UK. It has only been over the past ten years that a new generation of publishing houses – such as Kachifo, Cassava Republic and Parresia Publishers – have started publishing contemporary fiction in Nigeria. This is providing an outlet for a new generation of writers in a literary landscape still dominated by large educational publishing houses.

Nigerian authors are choosing to write for Nigerian audiences

Novelists Igoni Barrett, Lola Shoneyin and Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani have all found success in the West, yet these authors remain grounded in Nigeria. Their works tackle weighty issues of identity, corruption and polygamy, and use humour and irony to great effect.

Poets such as Titilope Sonuga, Dike Chukwumerije, Dami Ajayi and Efe Paul Azino are writing firmly for a Nigerian audience. Their poems take on Nigeria's political, economic and social concerns, and often reflect contemporary events with an immediacy impossible in other forms. For example, Titilope Sonuga's powerful poem Hide and Seek was a direct response to the violence taking place in Northern Nigeria, and the kidnapping of 270 schoolgirls from Chibok in April 2014. She asks 'What do we do with all these bodies? How do we know whose arm goes where?', and states that her poem was written 'For the children of the Yobe Massacre, for the people of the Nyanya bombings, for the 200-plus girls still waiting and for all the nameless, faceless victims of a nation in crisis'.

More Northern Nigerian novelists are writing in English about unknown aspects of the country

Perhaps one of the most exciting literary developments of the past year is the emergence of novelists from the North, such as Elnathan John and Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, who are writing in English about aspects of Nigeria that are as unknown to their fellow countrymen in Lagos, Ibadan and Enugu as they are to readers in the West. In this region, there is a strong tradition of authors writing in Hausa, but their work is rarely circulated outside the North, so outside exposure marks a departure from tradition in this case.

Ibrahim's novel Season of Crimson Blossoms is set in a conservative Hausa society and tells the story of an illicit relationship between a 55-year-old widow and a 25-year-old street gang leader. As Ibrahim explains in the BBC documentary, his aims were clear:

'It’s about telling people that there’s a lot more happening in the North than Boko Haram, than people killing people. It’s about humans, who have universal concerns, people who want to love, who suffer from heartbreaks, who have desires and ambitions and hopes...'.

Elnathan John's debut novel Born on a Tuesday , which has just been released in Nigeria and will be published in the UK in April 2016, looks at the personal stories behind the headlines. In the same documentary, he talks about the implications of story-telling. John argues that certain groups of people in Nigeria, such as Almajiri boys who receive Koranic education away from home, or poor people who roam the streets begging for food, are often reduced to numbers and figures, and their humanity forgotten. However, he says that telling stories is one way of providing 'some sort of nuanced approach' to how we talk about fundamentalism, culture, the relationship between the two, and also about violence and conflict.

As Nigerian writers and publishers become more confident, the literary landscape is moving its attention away from the West

The literary landscape in Nigeria is changing. The conversation about Nigerian writing, and, more widely, African writing, is taking place on the continent, without affirmation from the West. A series of readings, launches and festivals held in Nigeria over the past few months have generated much debate and excitement. The recent Ake Festival, held in Abeokuta, drew celebrated novelists Taiye Selasi and Helon Habila, as well as celebrated poet Niyi Osundare, to converse in Nigeria itself. In East Africa, the Kwani Litfest (Nairobi), Storymoja Festival (Nairobi) and Writivism Festival (Kampala) are now drawing in writers and guests from around the world.

Publishers are seeking to reflect authentic voices from the African continent

There is also an increased confidence among publishers. Rather than feeling the need to explain or mediate writing for the West, African publishers are seeking to reflect the authentic voice of the continent. Abubakar Adam Ibrahim's debut novel Season of Crimson Blossoms is peppered with Hausa; Eghosa Imasuen's Fine Boys has smatterings of pidgin throughout. Working with a publisher based in the country allows for a greater level of cultural understanding that is often much harder to achieve with an overseas publishing house. Author Elnathan John gives the example of working with an American editor who asked him what a 'go-slow' was. Every Nigerian knows the answer: it means a hold-up or traffic jam. He says, 'I use "go-slow" as an English word. Without apologies'.

Lagos-based publisher and author Eghosa Imasuen objects to the way in which Nigerian English has hitherto been represented on the page. As he explains in the documentary, the italicisation of words can be quite political: ' egusi ' would be italicised, but not the French word 'escargot'. He also objects to how things are explained unnecessarily for international audiences. For example, if you write 'He dipped his hand into the eba', a phrase will follow to explain that eba is 'that yellow globular mashed potato clone made from Cassava chippings'. When he talks about this his frustration is evident: 'You're like arrghhh, don't explain it, they can Google it!'

Bringing Nigerian writing to the UK without taking away the autonomy of Nigerian writers and publishers

Cassava Republic Press is one example of a publishing house that is breaking the mould. In a reversal from the traditional model, Cassava – now firmly established in Nigeria – has announced plans to establish a base in London from which to publish and distribute African authors. Publisher Bibi Bakare-Yusuf plans to bring Nigerian writing to the UK, strengthening the bonds between the two publishing landscapes, but without taking away the autonomy of Nigerian writers and publishers. A lack of distribution networks and myriad logistical challenges such as customs charges, poor road networks, and the high cost of transportation have until now prevented printed books from being more widely distributed out of Nigeria. Establishing a base in London will open up possibilities of distributing more titles more widely, including to East and Southern Africa.

Online literary magazines are bridging the void left by physical distribution challenges

Digital developments are also changing the landscape. Online literary magazines, such as Saraba Magazine and Jalada , are bridging the void left by physical distribution challenges. Their content, such as Jalada 's 2014 sex anthology, showcases confident African writing that needs no affirmation by the West. Ankara Press offers inspiring and entertaining stories by and for Africans, published in Nigeria, but available for purchase from anywhere on the globe.

The face of Nigerian, and African, literature is changing – the challenge is to keep your finger on the pulse.

Listen to Writing a New Nigeria , a two-part documentary programme produced by BBC Radio 4 as part of UK/Nigeria 2015-16, a major season of arts work in Nigeria.

Visit our literature site to find out more about our offer for writers and literature fans.

You may also be interested in:

- Five Nigerian novelists you should read

- How Nollywood became the second largest film industry

- The best cultural things to do in Lagos

View the discussion thread.

British Council Worldwide

- Afghanistan

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Czech Republic

- Hong Kong, SAR of China

- Korea, Republic of

- Myanmar (Burma)

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- North Macedonia

- Northern Ireland

- Occupied Palestinian Territories

- Philippines

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- South Africa

- South Sudan

- Switzerland

- United Arab Emirates

- United States of America

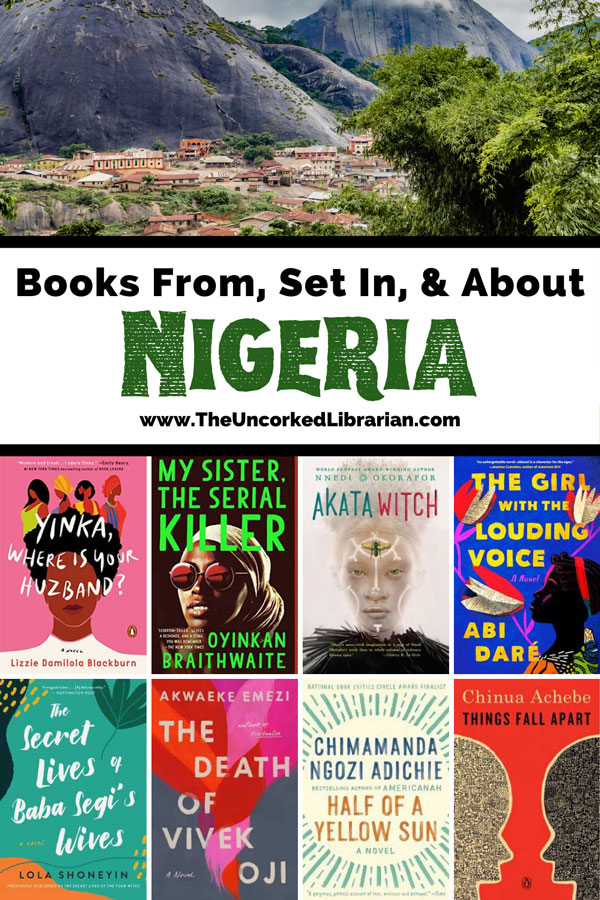

15 Of The Best Nigerian Books

Erika Hardison

Erika Hardison is a writer, social media junkie, podcaster, publisher and aspiring novelist from Chicago currently residing in New Jersey. When she's not bridging the gap between Black feminism and superheroes on FabulizeMag.com, she's spending sleepless nights as a new mom with her talkative toddler playing and giggling under the covers.

View All posts by Erika Hardison

When was the last time you read a novel by a Nigerian author? If you haven’t, here is the perfect opportunity to familiarize yourself with some of the best Nigerian books by new and well-known writers from Nigeria.

I was only a teen when I was introduced to Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart . It was an unusual book to me as a teen but it opened my eyes and mind to actively pursue literature from Black people who didn’t live in America. I think it’s important for people, especially Black and POC to embrace and educate themselves about cultures that differ from their own.

Throughout my adult years, I try to read books by authors who live in different parts of the world. However, when it comes to reading works from authors who are from Africa, it seems that Nigeria has the most visibility when it comes to seeking such material and content.

I love Nigerian customs and culture. Whether it’s the food, music, or clothing, every opportunity I’ve had to learn more about Nigeria and its history has been informative and delightful.

Whether you enjoy romance, sci-fi, mysteries or anything else in between, you’ll be able to find something you like. Even Netflix has a dedicated Nollywood category where viewers can stream an assortment of Nigerian shows based on the category they like.

This list is just a small sample of a growing number of Nigerian books and authors you should become familiar with. With a mix of upcoming and classics, you should be able to find some of the best Nigerian books to add to your TBR pile.

The Best Nigerian Books

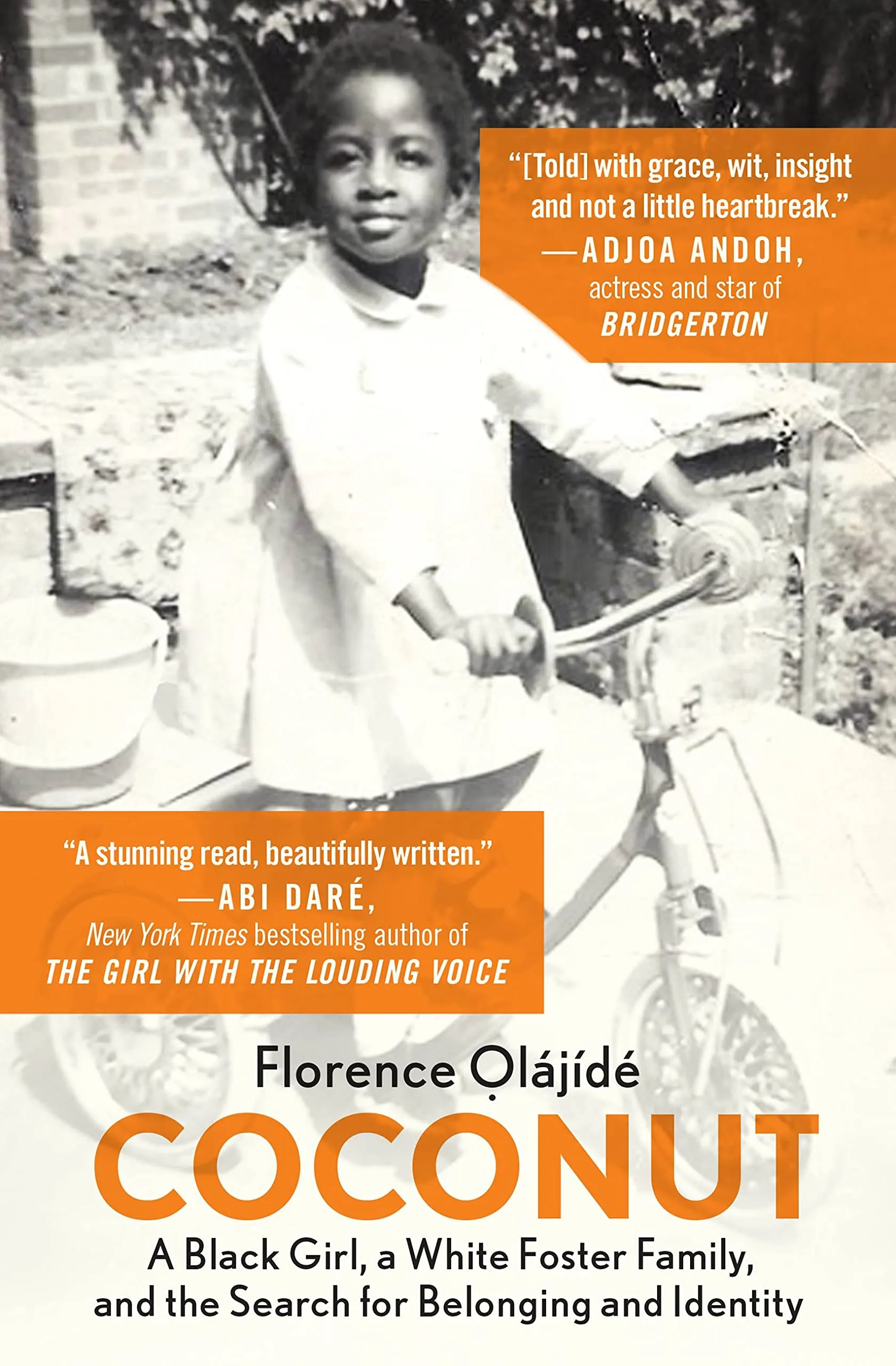

Coconut: A Black Girl, a White Foster Family, and the Search for Belonging and Identity by Florence Oòlaìjiìdeì

Set in the 1960s, the family-based memoir follows the childhood of Florence who grows up in London. Her parents, both Nigerian, relocated for work to give their family a better life. However, with her parents working, she was placed with a foster family and saw her parents only occasionally. When her parents decided to move back to Nigeria, Florence didn’t feel she fit in because of her English mannerisms and her inability to speak Yoruba. Her memoir showcases her struggles with trying to fit in in different cultures despite both of them being her own.

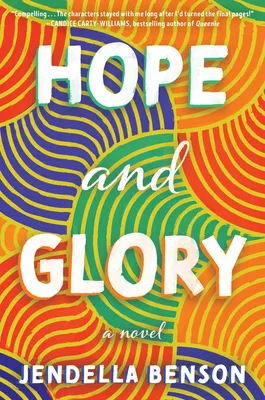

Hope and Glory by Jendella Benson

Glory is a British Nigerian who has been living in Los Angeles living her best life. But once she gets word of her father’s death, she’s finds herself flying back to Europe. Once she arrives, her family drama is on full display. There’s a deep, dark secret that’s been brewing in her family and Glory has the ability to keep her family from drifting apart.

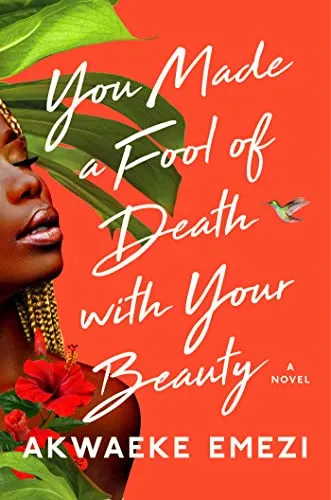

You Made a Fool of Death with Your Beauty by Akwaeke Emezi (May 24)

Feyi has suffered enough. After losing the love of her life in a terrible accident years ago, she is determined to find happiness again, moving to New York City to start over and further her art career. While with her friend she meets a man that she considers having a casual affair with. After all, he seems perfect, until she meets his sophisticated dad and you know what they say — the apple doesn’t fall too far from the tree.

A Coastline Is an Immeasurable Thing: A Memoir Across Three Continents by Mary-Alice Daniel (Nov 29)

This beautiful and poetic memoir follows the journey of Daniel’s family from Nigeria to England and America. Daniel recalls the culture shock she endured leaving Nigeria for England. From the weather changes, the cultural differences and the racism, Daniel felt she would never fit in. But Daniel found love and home in America when she traveled to California. Her resilience to life her life as a Nigerian, British, and American girl growing up under fundamentalist Christian and Islamic cultural influences gives hope to all Black diaspora people who want to take their culture to new places to call home.

The Legacy of Molly Southbourne (The Molly Southbourne Trilogy Book 3) by Tade Thompson (May 17)

This bloody sci-fi horror thriller is the conclusion to the Molly Southbourne series. If you haven’t read the first two, don’t worry because these novellas are a scary delight to get through. In this conclusion, Molly Southbourne is gone, but her spirit and sisters are still wandering about as they try to find peace and move on from their deadly past. However, the truth lives in Molly’s blood and there is no escaping no matter how hard they try.

Where the Children Take Us: How One Family Achieved the Unimaginable by Zain E. Asher (April 26)

CNN news anchor Asher delivers an emotional memoir that serves as a dedication to her mother. Asher relives her childhood as she reflects the sacrifices and the strength her mother displayed after her father succumbed to fatal injuries in a car accident. Her mother challenged her and her siblings by using tough love and Nigerian parenting techniques that groomed her children for success. From creating a book club to cutting out newspaper clippings of inspirational Black people, Asher makes her mother a superhero in her inspiring memoir.

Notes from a Young Black Chef by Kwame Onwuachi with Joshua David Stein

Top Chef star Kwame Onwuachi adapted his book for a YA audience last year because he wanted to inspire younger readers as well. Onwuachi grew up in the Bronx and even though his father is Nigerian, he was in for a bit of a shock when his mother sent him to Nigeria with his grandpa. This memoir serves as a testament to how culture, food and perseverance can overcome any challenges and it can be delicious, too!

Wahala: A Novel by Nikki May

A challenging story that covers race and class and how it impacts a group of friends. These friends are biracial mixed with Nigerian and they view the world through their rose-tinted glasses. Bound by Eurocentric ideas of beauty such as “good hair,” this novel sheds light on how marginalized groups can still benefit from privilege.

Operation Sisterhood by Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich

If you’re an only child, you probably have thought about how your life would be different if you had siblings. For Bo, that reality came true once her mother started dating Bill and they moved to Harlem, New York. Now Bo and her mother are living with Bill and his daughter as well as another couple and their twin daughters. Bo’s newfound sisterhood is making their family closer and their community stronger.

Lightseekers by Femi Kayode

There’s a lot of Nigerian literary fiction available now, but have you ever considered trying out a Nigerian political thriller? This book is a fast-paced story about university students being killed and a government official assigning a criminal psychologist named Dr. Taiwo on the case. Dr. Taiwo isn’t a cop and he’s only there to determine the motive of the perpetrators, but he finds himself going down a rabbit hole of political corruption and conspiracies — now his life in is danger.

The Sweetest Remedy by Jane Igharo

Igharo delivers a Nollywood-style romance that involves a young woman named Hannah. Hannah doesn’t know much about her Nigerian father, except that he’s dead and now she’s on a flight preparing to meet the family she’s never met before. She quickly realizes that her father had wealth but the chaos leading to her father’s funeral reveals family secrets while Hannah continues to struggle how she can navigate Nigerian culture.

The How: Notes on the Great Work of Meeting Yourself by Yrsa Daley-Ward

Yrsa Daley-Ward is half Jamaican and half Nigerian, and her poetry book doubles as an exploration of self-help book about self-love. From Beyoncé to Instagram, she has had her powerful words reposted and shared countless of times. While Daley-Ward has penned beautiful and thoughtful words across social media, she continues to uplift others with her words of affirmations and encouragement.

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe

Published in 1958, Things Fall Apart is one of the most celebrated books in African and world literature. One of the main characters of this story is Okonkwo who embodies a lot of negative traits that he tries to justify as a positive. Now on the verge of being colonized by the British, Okonkwo looks to his ancestors for their wisdom to help him survive.

Yinka, Where Is Your Huzband? by Lizzie Damilola Blackburn

Yinka considers herself a success. She has a good job, graduated from a prestigious school, and has the best friends she can ask for. But that doesn’t stop her mother from always asking her where is her huzband ? For Yinka’s mother, her life isn’t complete unless she gets married and have children. That makes Yinka reevaluate her life as she learns that before anyone else can love her she has to love herself first.

The Carnivorous City (Lagos Noir) by Toni Kan

This book reminds of the the lyrics by Goya Menor and Nektunez called Ameno Amapiano. “You want to bamba? You want to chill with the big boys?” are the lyrics and I feel this song would be the perfect song if this book has a soundtrack. Soni is well-known for being a boss and gangster in Lagos but now that he’s gone missing. Now his brother Abel is back home and is looking for him. Abel finds himself caught between criminals with old beef with his brother and corrupt public servants that want to cash in on his family’s misfortunes.

Did you enjoy this list? If so, check out this informative round-up of Nigerian feminist reads to add to your TBR.

You Might Also Like

Postcolonial Literatures in the Local Literary Marketplace pp 81–140 Cite as

Nigeria: Nigerian Literature and/as the Market

- Jenni Ramone 4

- First Online: 07 August 2020

256 Accesses

Part of the book series: New Comparisons in World Literature ((NCWL))

This chapter argues that the Nigerian market, a place for meeting, negotiation, reflection, and trade, is also central to the meaning of reading and the contingent position of the Nigerian author within their local literary marketplace. The chapter asks what reading means in Nigerian literature noting the significance of education and the market, in Helon Habila’s Waiting for an Angel , Chinua Achebe’s No Longer At Ease , Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus and Half of a Yellow Sun, Chihundu Onuzo’s Welcome to Lagos , Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani’s I Do Not Come to you by Chance , Chris Abani’s Graceland , and Ben Okri’s The Famished Road and Dangerous Love . Onitsha Market Literature illustrates the central position of the market in Nigerian literature and literary culture.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Abani, Chris. 2005. Graceland . New York: Picador.

Google Scholar

Achebe, Chinua. 1960. No Longer at Ease . London: Heinemann.

Achebe, Chinua. 2010 [1966]. Chike and the River . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. 2006. Half of a Yellow Sun . London: Harper Perennial.

———. 2009. Jumping Monkey Hill. In The Thing Around Your Neck , 95–114. London: Fourth Estate.

———. 2013 [2004]. Purple Hibiscus . London: Fourth Estate.

———. 2015. Apollo. The New Yorker , 13 April.

Anafulu, Joseph C. 1973. Onitsha Market Literature: Dead or Alive? Research in African Literatures. 4 (2): 165–171.

Armah, Ayi Kwei. 1988 [1969]. The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born . Oxford: Heinemann.

Armah, Ayi Kwei. 2008. The Beautyful Ones are Not Yet Born . San Francisco: Per Ankh.

Barris, Ken. 2011. To See the Mountain. In Caine Prize: To See the Mountain and Other Stories , 83–92. Oxford: New Internationalist.

Bastian, Misty L. 1992. The World as Marketplace: Historical, Cosmological, and Popular Constructions of the Onitsha Marketplace . Unpublished thesis. https://www.academia.edu/12562318/The_World_as_Marketplace . Accessed 12 February 2018.

Bejjit, Nourdin. 2018. A Colonial Affair: Heinemann Educational Books and the African Market. Publishing Research Quarterly 34 (2): 275–287.

Bello, Hakeem. 2014. The Interpreters: Ritual, Violence, and Social Regeneration in the Writing of Wole Soyinka . Ibadan: Kraft.

Block de Behar, Lisa, Paola Mildonian, Jean-Michel Djian, Djelal Kadir, Alfons Knauth, Dolores Romero Lopez, and Marcio Seligmann Silva. 2009. Comparative Literature: Sharing Knowledges for Preserving Cultural Diversity . Vol. III. Oxford: EOLSS Publications (UNESCO).

Boehmer, Elleke. 2018. Postcolonial Poetics . London: Palgrave.

Brown, Aaron. 2018. Family Politics: Negotiating the Family Unit as Creative Force in Chigozie Obioma’s The Fishermen and Ben Okri’s The Famished Road . In Art, Creativity, and Politics in Africa and the Diaspora , ed. Abimbola Adelakun and Toyin Falola, 69–82. London: Palgrave.

Bruner, David K. 1985. Review: Veronica My Daughter and Other Onitsha Market Plays and Stories. World Literature Today 55 (1): 166.

Carroll, Lewis. 1982 [1895]. What the Tortoise Said to Achilles. In The Penguin Complete Lewis Carroll , 1104–1108. Penguin: Harmondsworth.

Chipasula, Stella, and Frank Mkalawile Chipasula. 1995. The Heinemann Book of African Women’s Poetry . London: Heinemann African Writers Series.

Clarke, Simon. 1995. Marx and the Market . Centre for Social Theory, University of California, Los Angeles. https://homepages.warwick.ac.uk/~syrbe/pubs/LAMARKW.pdf . Accessed 21 Mar 2019.

Cormaroff, John, and Jean Cormaroff. 1999. Alien-Nation: Zombies, Immigrants, and Millennial Capitalism. Codesria 3&4: 17–28.

Currey, James. 2003. Chinua Achebe, the African Writers Series and the Establishment of African Literature. African Affairs. 102 (409): 575–585.

———. 2008. Africa Writes Back: The African Writers Series and the Launch of African Literature . London: James Currey.

Dalley, Hamish. 2013. The Idea of ‘Third Generation Nigerian Literature’: Conceptualizing Historical Change and Territorial Affiliation in the Contemporary Nigerian Novel. Research in African Literatures 44 (4): 15–34.

Dodson, Don. 1973. The Role of the Publisher in Onitsha Market Literature. Research in African Literatures 4 (2): 172–188.

Dunning, Stefanie. 2001. Parallel Perversions: Interracial and Same Sexuality in James Baldwin’s Another Country. Melus 26 (4): 95–112.

Ekwensi, Cyprian. 1987 [1961]. Jagua Nana . London: Heinemann African Writers Series.

Esonwanne, Uzoma. 2008. Interviews with Amaka Igwe, Tunde Kelani, and Kenneth Nnebue. Research in African Literatures 39 (4): 24–39.

Eze Goes to School. 2012–2013. http://www.naijastories.com/tag/eze-goes-to-school/ . Accessed 20 November 2015.

Falola, Toyin, and Matthew M. Heaton. 2008. A History of Nigeria . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Furniss, Graham. 2000. Documenting Kano ‘Market’ Literature. Africa Bibliography 1998: vii–xxiii.

Garuba, Harry. 2003. Explorations in Animist Minimalism. Public Culture. 15 (2): 261–286.

Green, James. 1995. The Publishing History of Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative. Slavery & Abolition. 16 (3): 362–375.

Griffiths, Gareth. 2000. African Literatures in English . Harlow: Longman.

Griswold, Wendy. 2000. Bearing Witness: Readers, Writers, and the Novel in Nigeria . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Griswold, Wendy, and Misty Bastian. 1987. Continuities and Reconstructions in Cross-Cultural Literary Transmission: The Case of the Nigerian Romance Novel. Poetics 16 (3): 327–351.

Habila, Helon. 2002. Waiting for an Angel . Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Henderson, Richard N. 1975. An African Popular Literature: A Study of the Onitsha Market Pamphlets by Emmanuel Obiechina. American Anthropologist 77 (4): 962–964.

Henderson, Helen Kreider. 1997. Onitsha Women. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 810 (1): 215–243.

Huggan, Graham. 2001. The Postcolonial Exotic: Marketing the Margins . London: Routledge.

Ibrahim, Abubakar Adam. 2012. The Whispering Trees . Lagos: Parresia.

Ike, Chukwuemeka. 2007. Contemporary Nigerian Youth and the Reading Culture. Matatu: Journal for African Culture and Society 33 (1): 339–342.

Kochan, Donald J. 2006. The Blogosphere and the New Pamphleteers. Nexus: A Journal of Opinion 11: 99–129.

Kolawole, Samuel. 2009. The Book Chain and National Development . http://www.samuelkolawole.com/images/Building%20A%20Virile%20Society.pdf .

McEwan, Neil. 1983. Africa and the Novel . London: Macmillan.

McNally, David. 2011. Monsters of the Market: Zombies, Vampires and Global Capitalism . Leiden: Brill.

Newell, Stephanie. 1996. From the Brink of Oblivion: The Anxious Masculinism of Nigerian Market Literatures. Research in African Literatures 27 (3): 50–68.

———. 2005. Devotion and Domesticity: The Reconfiguration of Gender in Popular Christian Pamphlets from Ghana and Nigeria. Journal of Religion in Africa 35 (3): 296–323.

———. 2006. West African Literature: Ways of Reading . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o. 1986. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature . London: James Currey.

Nwaubani, Adaobi Tricia. 2010. I Do Not Come to You by Chance . London: Phoenix.

Nwoga, Donatus. 1965. Onitsha Market Literature. Transition 19: 26–33.

Nzekwu, Onuora. 1971 [1963]. Eze Goes to School . Lagos: African Universities Press.

Obiechina, Emmanuel. 1973. An African Popular Literature: A Study of Onitsha Market Pamphlets . London: Cambridge University Press.

Ogene, Mbanefo S. 2017. Onitsha Market Literature: An Accepted Literary Subgenre or Fossilized Specie? A Formalist Approach to Ogali Ogali’s Veronica My Daughter. Studies in Literature and Language 14 (5): 1–5.

Okoye, Ifeoma. 1984. Men Without Ears . London: Longman.

Okpalaenwe, Elizabeth Ngozi. 2011. The Lost Friend. In Caine Prize: To See the Mountain and Other Stories , 160–169. Oxford: New Internationalist.

Okri, Ben. 1986. Incidents at the Shrine . London: Penguin.

———. 1991. The Famished Road . London: Jonathan Cape.

———. 1996. Dangerous Love . London: Phoenix House.

Olowu, Dele. 1992. Urban Local Government Finance in Nigeria: The Case of Onitsha Local Government. Public Administration Development 12 (1): 39–52.

Onitsha Market Literature. University of Kansas Libraries. http://onitsha.diglib.ku.edu/index.htm . Accessed 20 November 2015.

Onuzo, Chihundu. 2017. Welcome to Lagos . London: Faber.

Onwukwe, Chimdinma Adriel. 2016. Equiano’s Travels (Part One). Adrielnaline , 23 May. https://adrielzjournal2013.wordpress.com/2016/05/23/equianos-travels-part-one/ . Accessed 22 March 2019.

Osundare, Niyi. 1983. Songs of the Market Place . Ibadan: New Horn.

Owusu, Martin. 1973. The Sudden Return and Other Plays . London: Heinemann.

Phillips, Delores B. 2012. ‘What Do I Have to Do with All This?’ Eating, Excreting, and Belonging in Chris Abani’s Graceland . Postcolonial Studies 15 (1): 105–125.

Povey, John. 1973. Review of Onitsha Market Literature by Emmanuel N. Obiechina. African Arts 6 (4): 86.

Primorac, Ranka. 2012. Reasons for Reading in Postcolonial Zambia. Journal of Postcolonial Writing 48 (5): 497–511.

Ramone, Jenni. 2017. The Bloomsbury Introduction to Postcolonial Writing: New Contexts, New Narratives, New Debates . London: Bloomsbury.

Raynaud, Claudine. 2012. The Text as Riddle and Death’s Many Ways: Ben Okri’s The Famished Road . Études anglaises. 65: 331–346. https://www.cairn.info/revue-etudes-anglaises-2012-3-page-331.htm# . Accessed 23 February 2019.

Soyinka, Wole. 1965. The Interpreters . London: Andre Deutsch.

Terry, Olufemi. 2011. Dark Triad. In Caine Prize: To See the Mountain and Other Stories , 204–214. Oxford: New Internationalist.

Uchendu, Victor C. 1965. The Igbo of Southeast Nigeria . New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Udobang, Wana. 2015. Writing a New Nigeria, Episode 1. BBC Radio 4 , 3 December. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06qm3mk . Accessed 20 March 2016.

Ugochukwu, Francoise. 2009. Review of Stephanie Newell, West African Literature: Ways of Reading . Africa 79 (2): 311–312.

Whitlock, Gillian. 2000. The Intimate Empire: Reading Women’s Autobiography . London: Cassell.

Whitsitt, Novian. 2002. Islamic-Hausa Feminism and Kano Market Literature: Qur'anic Reinterpretation in the Novels of Balaraba Yakubu. Research in African Literatures 33 (2): 119–136.

Wilkinson, Janet. 1992. Ben Okri. In Talking with African Writers , 76–89. London: Heinemann.

Winch, Peter. 1958. The Idea of a Social Science and its Relation to Philosophy . London: Routledge.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of English, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Jenni Ramone

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jenni Ramone .

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Ramone, J. (2020). Nigeria: Nigerian Literature and/as the Market. In: Postcolonial Literatures in the Local Literary Marketplace. New Comparisons in World Literature. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-56934-9_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-56934-9_3

Published : 07 August 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-137-56933-2

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-56934-9

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

A brief History Of Nigerian Literature in English: The preamble

I was a palm-wine drinkard since I was a boy of ten years of age. I had no other work than to drink palm wine in my life. In those days, we did not know other money except cowries, so that everything was very cheap, and my father was the richest man in our town.

That passage is what is is now regarded as the first paragraph in Nigerian Literature. But is it really? To do justice to the question, one needs to first differentiate between Nigerian literature and Nigerian Literature in English.

Nigerian literature is ANY body of imaginative work by a Nigerian, made for Nigerians, while Nigerian literature in English is any piece of imaginative work written in English. The palm wine drinkard might have been the first Nigerian literature in English, but definitely not the first piece of literature in the country.

Imperialism no doubt was behind the notion that Nigerian societies before the colonial masters were primitive and lacked sensibilities. The European on stepping on the shores of the continent wrote about its inhabitants lacking artistic talents, or any ability to create arts even though the opposite was staring them in the face. To them, Nigerians only got engaged in making literature after the 1882 ordinance that mandated English to be taught in Nigerian schools.

Literature, therefore, is more than an imaginative epistle

African literature as a whole and Nigerian literature in particular was not birthed by the presence of the colonial masters, but rather, existed in myths, folktales, legends, songs and other various forms centuries before Europeans invaded the continent. That period is what is known as the classical period of Nigerian literature. Literature is a vehicle of ideologies; a composition of language that serves as a cultural representation of a people. Literature, therefore, is more than an imaginative epistle.

Nigerian literature before the 19th centuries was in form of orature. And as is the case in any society, literature comes first in orality, and only much later did it metamorphosize into written form, and Nigeria is no different. Although it has to be said that recording Nigerian oral literature is a tad difficult as its practitioners were, more often than not, members of a cult who jealously guarded certain knowledge.

Ruth Finnegan’s book Oral literature in Africa (1970) is an eye opener, and states, without mincing words, that African and Nigerian literature were in vibrant stages before the whites arrived, and that Africans had organised, and developed replacements for the written form. Songs were sung at weddings; poetry were read to praise gods; tales were performed at town gatherings; each family had their own peculiar poetry, and stories were told to praise legends. Nigerian Oral literature were a source of entertainment, philosophies, and beliefs, and involved verbal storytelling perfected to an art form.

Folktales were dramatic replacements for the novel. They are an imaginative form of narrative literature woven around well liked characters, sometimes even animals, as they relate with the physical world, or sometimes, the supernatural world. In the Eastern and Western part of the country, the tortoise is a star of many such tales. These stories, maybe not written, nonetheless have characters, plot, beginning and end, and even epiphanies. The same applied to myths – which were tales about death, afterlife, or creation and the supernatural. Sometimes, it looks like an earlier version of today’s science fiction.

The Europeans brought their own literature, written in books, and that, combined with the return of Samuel Ajayi Crowther made Nigerians see the need to record their stories and culture, and thus the beginning of Nigerian literature in a written format. And even as a written form, Nigerian literature didn’t start in 1952 when Amos Tutuola published the Palmwine Drinkard.

By the 1930’s, the Hausas already had a writing competition in place, and winning entries, including Shehu Umar by Abubakar Tafawa Balewa were published.

Hausa literature dates back centuries before the palm wine Drinkard. Infact, it got to a peak after Usman Dan Fodio and Islamic scholars brought Arabic into Hausa territory. By the 1930’s, the Hausas already had a writing competition in place, and winning entries, including Shehu Umar by Abubakar Tafawa Balewa were published. The stories were written in Ajami – a mixture of Arabic and Hausa.

Samuel Ajayi Crowther translated the Bible into Igbo (He also translated the Bible into Yoruba), and that was the first body of written work in the Igbo language. It took until 1933 before the first novel in Igbo – Umenuko, by Pita Uwana, was published. The population boom in the 40’s also saw a rise in publishing houses in the East. Cypwian Ekwensi was one of many writers of the Onitsha literary scene with stories like When love whispers; a love story, and Ikolo the wrestlers and other Igbo tales. Another popular work was Chika Okonyia’s Tragic Niger Tales. The Onitsha literary scene will eventually produce over 200 works.

In the mid to late 1800’s, Itan Segilola Eleyinjuege by Isaac B. Thomas was written, but wasn’t published until 1930. It is actually regarded by many to be the first piece of written literature in the country.

In the mid to late 1800’s, Itan Segilola Eleyinjuege by Isaac B. Thomas was written, but wasn’t published until 1930. It is actually regarded by many to be the first piece of written literature in the country. It preceded D.O Fagunwa’s Ogboju-ode Ninu Igbo Irunmole(1930) by at least nine years. Fagunwa’s story would later be translated to Yoruba by Wole Soyinka (The forest of A Thousand Daemons)

Although The Palmwine Drinkard might well be the first Nigerian literature in English, it still had it roots in Oral literature. It was written in a vernacular style that made it look as if it was meant to be performed and not read, and the story borrowed from orasure, as it was already a popular one passed down for generations. It must be said though that the former reason no doubt was connected to Fagunwa’s limited education.

Although The Palmwine Drinkard might well be the first Nigerian literature in English, it still had it roots totally meshed in Oral literature.

The story became a bit controversial for the above reasons, as some Nigerian critics failed to see it as a body of imaginative work, and others were ashamed of the grammar and use-of English. The book was accepted overseas, receiving numerous rave reviews and was subsequently heralded, quite wrongly, as the first piece of literature in Nigeria.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

© 2019 Mainland Book Cafe. All Rights Reserved.

- Folio Nigeria

“‘Our Literature Has Died Again’: Nigerian Writing in the Era of the Nomadists”

Kanyinsola olorunnisola.

- August 17, 2023

Two years ago, I wrote an essay that may haunt me for the rest of my life. It left undeniable evidence of my anti-patriotism, my emotional treason against the green-and-white, backed by coldblooded remorselessness. I may have embraced the darkly comical aphorism that “the best way to be a Nigerian is to be a Nigerian in the diaspora.” That, and the social critic Ayo Sogunro’s quotable summary: Everything in Nigeria is going to kill you .

When I started that essay, I was a cliche: a church rat, a cart-pulling mule, another Lagos writer bending over for some non-literary industry that wanted nothing more than to undo him. I worked late-nights for garri grains, with no likelihood that my talents would ever earn me a satisfactory life, let alone the kind of celebrity I read about in foreign newspapers and magazines, the kind enjoyed by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie , by Ben Okri , by Nnedi Okorafor, all to varying extents. I wanted nothing more than to get out of my fuckfest of a country.

By the time the essay came out, I was stuffing my jeans and shirts into a Ghana-must-go, about to become a different kind of cliché: just one of thousands of young Nigerians who decided to jápa, to leave behind the country that birthed and bruised them, to seek new homes in various forms of elsewhere. My own elsewhere was the United States.

I joined the newly infamous coterie of Nigerian writers who found refuge within the grand, slave-built walls of American universities, in hopes of securing the much-loved, much-loathed M.F.A. degree. I had become what the culture critic Oris Aigbokhaevbolo, in a provocative essay entitled “ The Death of Nigerian Literature ,” called “the Nigerian literary immigrant.” And, given the notorious population of writers in a country of over 200 million, who knows how many of us there are?

To be a Nigerian Literary Immigrant is to be a traitor of sorts, some now imply. It is to be a new kind of punching bag. Your association with Western culture is taken as a blemish on your authenticity, and you will have to read fellow writers wonder aloud if the literature you create should be considered part of the national canon.

The authenticity debate used to make me insecure. In my first days here, another African student insinuated that Americans relate to my work because I erase my cultural context. My first instinct was to get defensive, to talk about how my novel-in-progress is influenced almost entirely by pre-colonial West African spirituality and aesthetics. But I soon realized that that comment was not personal, at least not entirely personal. It reflected a specific artistic anxiety in which people equated external influence with loss.

It is an old anxiety. In 1963, when Obi Wali lamented “ The Dead End of African Literature ,” bemoaning how the bulk of it was produced mainly in colonial languages, a rigorous discourse followed. But Aigbokhaevbolo’s essay, which has significantly different concerns from Wali’s, has been followed by a curious indulgence here and a tepid pushback there or, well, tweets or, worst, agreements, no matter how reasoned . Because there has been no actual counter-argument, that narrative continues. Our literature has died again. The glory days are behind us again. We are always headed for doom . K’ọ́lọ́un ṣàánú.

This tedious obsession, this puritan misinterpretation of belonging and authenticity, should not be taken as the definitive story.

The “search for a better life has resulted in both the depletion of Nigerian writers and Nigerian writing,” Aigbokhaevbolo argues, and links this to the emigration of writers with whom he “shot the breeze” at places like Freedom Park, Lagos. But such a claim as the death of an entire country’s literature needs to be backed by more than a single writer’s immediate vicinity and experience. It seems to have stemmed from at least two questionable premises: that the critic’s own limited circle in Lagos represents the entire literary industry; and that the writers abroad, more specifically the M.F.A. crowd, are not doing much writing.

The first premise and its eventual argument are nearsighted and dismissive. Let me introduce a rather controversial idea: the literary scene exists beyond Lagos! Nigerian writers are doing more work than we have seen in a long time. There are lively literary communities in Ibadan , in Nsukka , in Awka , in digital spaces undefined by geography.

Recent years have seen the rise of new organisations. We have seen 20.35 Africa , whose anthology series is bridging gaps in the conversation around African poetry, and Agbowó , a literary and arts hub with a magazine that publishes bi-annual issues. There is Isele , which runs its own prizes . There is A Long House , which publishes contemplations of Blackness and administers an editorial fellowship. SprinNG , which I co-founded in Ibadan, raises money to support young Nigerian writers through its Women Authors Prize, an advancement fellowship, a writing fellowship, and an M.F.A. Academy.

Open Country Mag has changed African literary journalism with its longform Profiles, features, and reviews, and is solving decades-old infrastructure gaps with its The Next Generation series and a curatorial fellowship , and this year collaborated with bookstore Rovingheights to publish the first ever formal bestseller list in Nigerian literature . There is Za! , whose debut issue delves into African spirituality. And there is Efiko Mag , run by Aigbokhaevbolo himself, which gave us the essay I am responding to.

These platforms are presenting work that deserve critical attention. Some of the writers who run them live in Nigeria. Most of the rest who now live elsewhere founded them while in Nigeria. How could one pronounce our literature dead with this beating heart?

Aigbokhaevbolo’s second premise assumes that Nigerian literary emigration is a unique development that equals abandonment of the industry, and so has been negative for productivity. It is not. The emigration of writers is not a Nigerian phenomenon. There is nowhere in the world in which writing is a stable lucrative path, not like medicine, not like tech. To commit to a literary career is to stare directly into an abyss, to witness its dark nothingness and still fling yourself right into its mouth, hoping to find some semblance of light. Masochist stuff, really. God help us. So from everywhere else writers are emigrating to the West, which has the structure to support it in small ways. This is a positive thing, and it has led to a circumstance in which Nigerian writers in M.F.A. programs are writing more than they ever did but are not publishing their work at the rate you would expect if you were not within the system.

And it makes perfect sense.

Back in Nigeria, I existed in this nonspace of seeking recognition. I wanted to publish as much as possible so I could get readership. There was a restlessness, a need to keep doing and to keep showing that I could publish in this and that place, that I could have an enviable bio.

But then came the M.F.A., a major currency for a young writer, which gives you permission to slow down and calm yourself, to pay attention to the creation and perfection of the work rather than its immediate publication. Weekly workshops taught me to be more critical of my work, to keep producing in silence until I was truly ready to share the work. The small-small publications here and there that I had once chased to give my career some appearance of progression no longer cut it. I had to dream bigger. And to achieve that, I needed to sit down and work myself to the bone, workshop the work to death. Weekly phone calls with writer-friends all over the U.S. confirm that I am not alone in this experience, and that it pays dividends.

Since their respective inhabitations of the Literary Immigrant identity, we have seen the releases of, among others, Arinze Ifeakandu ‘s God’s Children Are Little Broken Things , Romeo Oriogun ‘s Sacrament of Bodies and Nomad , Logan February ‘s Fuckboys , Gbenga Adeoba’s Exodus , and Ukamaka Olisakwe ‘s Ogadinma, or Everything Will Be All Right . We have been told to anticipate Ugochukwu Damian Okpara’s In Gorgeous Display , Pemi Aguda’s Ghostroots and The Suicide Mothers , Chukwuebuka Ibeh’s Blessings , yours truly’s Shakespeares in the Ghetto , to name a few.

Look at Open Country Mag ‘s annual anticipated and notable book lists and see the slow increase in the number of writers who left Nigeria for an M.F.A. and now have books ready. So the claims that “the Nigerian writer is not heavily involved in the production of literary writing anymore,” and that “to be a Nigerian writer these days is not to be a writer at all,” ignores all the good writing that is already here. One should at least buy and read them before declaring our literature dead.

What is most curious is that Aigbokhaevbolo does not mention the names of writers that belong to this non-productive group. Perhaps if he had been committed to specificity, to the rigor of naming and identifying, to being more microscopic than abstract, he would have realized the flaws in his argument.

This convenient omission is shared by another recent lamentation, this time by the poet Ernest Ogunyemi, a former staff writer for this magazine . His essay, “ Is Contemporary Nigerian Poetry Nigerian? “, is an otherwise necessary critique that suffers from far too many moments of puerility. One feels as though they just read literary criticism deployed as a smokescreen for a diss. Perhaps intended to be inflammatory, it got a predictable level of attention. But no response has actually engaged its gripe with contemporary poetry. Perhaps critics do not see the potentially striking points that an actually edited version of the essay would have made?

It is another return of the authenticity question. À fi authenticity yíì náà! Ogunyemi proposes an essentialism that doubles as a petitio principii fallacy, identifying a Nigerian poem through its “placement of Nigerian things” and “Nigerianness” in its lines, as though there were a singular definition of “Nigerian,” as though a Nigerian identity were not in itself rooted in a colonialist fantasy, as though Nigerianness as a cultural or aesthetic signifier were not a nonsensical facade when queried to its existential limits. That stance betrays the critic’s belief in his own conception of Nigerian as the center, and that everything else that does not fit into that is inauthentic. What else could prompt phrasing like “an American poem written by a Nigerian”?

I am a sworn Afrocentrist. But while I would also love to see more cultural lore, spirituality, and code-mixing in our poetry, no one’s intellectual allegiance should be enough to invalidate the inclusion of others’ poetry within such a broad description as “Nigerianness.” You are either Nigerian or you are not; and the poetry you put out automatically has a claim within Nigerian writing. The Nigerianness of a poem is in the Nigerianness of its poet, no matter how they navigate or evade said Nigerianness. This is true of poetry, even though it would be debatable with fiction and nonfiction.

While Ogunyemi’s essay would have come out better if he were guided by a capable editor, no one should pretend that some of its arguments have no merits. He writes that “Nigerian poets are not interested in Nigeria,” that “the world around us is not interesting to us.” I agree to an extent. There is not enough poetry about both the mundane and sociopolitical realities of life back home. Not enough poems about Tinubu, about fuel scarcity, about the sweet palm oil stench of Oje market in Ibadan. We need to encourage more of those. But that certainly does not mean that whomever chooses to not do this is not writing Nigerian poetry. They simply have other concerns that are just as valid.

Aigbokhaevbolo makes good points as well. The most interesting is that there is silence around what happens when writers leave for their M.F.A.s. A disturbing, numbing silence. But the silence is not because Literary Immigrants are not writing at all; it is simply because they are not writing or talking much about their lives after migration. Like most people, before applying for my M.F.A., I had no idea what to expect, how to go about the process. I resorted to reading American writers’ accounts on blogs, unsure how much of their advice was relevant to my situation.

But things are changing. The writer Ucheoma Onwutuebe has detailed her experience; later, she joined a panel conversation of M.F.A. students, moderated by me for SprinNG and attended by 169 people, to discuss the academic, literary, and emotional aspects of immigration. The poet Itiola Jones, who is American Nigerian, recently hosted a two-day SprinNG session on how to apply for M.F.A.s. As more writers speak and write about their own experiences, that gap will be filled.

A truce then with Aigbokhaevbolo and Ogunyemi. There is sense in their overall arguments; they have hit sore points that our literary culture lacks the range to appreciate thoroughly, but they have done it from incomplete perspectives. Where Aigbokhaevbolo does not acknowledge the existence of Nigerian works that do not appeal to his peculiar interests, Ogunyemi denies the validity of works that do not fit into his limited definition.

Ogunyemi is taking a Nativist position. (He belongs to what I now call the Tiwani School, after a Yoruba phrase loosely translatable as Na we get am ). For literary Nativists, including the influential Obi Wali, writing must prioritize culturally locatable aesthetics and indigenous linguistic elements. But Nativism is insufficient in a changing world, and even less for the literary culture of a formerly colonized country.

What makes culture criticism more intellectually interesting is the ability to not only identify trends and shifts but to name them, so that we can track their progress, their push-and-pull against other current traditions, their evolution. Until a development is named, we are trapped in unproductive conversations that never go beyond “authenticity.”

But naming is rather rare in Nigerian and African literature today. The most recent effort was by Otosirieze , the founder and editor of this magazine, who, in his introduction to the 2018 anthology Selves: An Afro Anthology of Creative Nonfiction , christened a crop of young African nonfiction writers “ The Confessional Generation ,” due to their being “unshackled, unspooling confessions in a hitherto unconventional manner.” It was the first time that anyone had pinpointed what is now a noticeable embrace, in African literature, of Americanisms.

So now we have the Nativists, on the one hand, and on the other, the specific category of writers that Aigbokhaevbolo and Ogunyemi’s essays deny legitimacy. Like their critics, these writers are part of the Fourth Generation of Nigerian literature. Like that of the Confessional writers, their approach demands a more specific term, a definition separate from those working in the tradition erroneously deemed the pinnacle of authenticity. We need to understand them as a literary subculture, like the Beat Generation and the New Negro Movement in the U.S., like the Oulipo in France.

Context: In recent years, disillusionment with the Nigerian identity has become more pronounced, with most Nigerians hoping to exist almost anywhere else. Seven out of every 10 Nigerians living in the country are making plans to leave. Desperate Nigerians are taking to sea to escape. (The Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act of 2014 has led to a more stifling life for a lot of queer women and men in an already bigoted society; in 2017, seven out of every 10 Nigerian asylum requests in Ontario, Canada were based on sexual persecution). It is a brain drain owed to a host of calamities: failed leadership, insecurity, inflation, unemployment.

Like the rest of their leaving compatriots, some of the leaving writers are disillusioned and express little patriotism toward a birth country that has failed to offer them the flourish they deserve. What we are seeing is that they have become the voices of the entire non-literary generation: the Jápa Generation. These writers are nomads in their work, many untethered to any space in aesthetic. Existentially speaking, they are always on the road, comfortably in flux. These writers, I call the Nomadic Generation.

(An American antecedent: In the 1920s, a number of American writers — disillusioned with their country’s post-war realities of crass materialism, censorship, economic uncertainty, and intellectual drought — migrated to Paris, then seen as the cultural capital of the Western world, where fashion, music, dance, art, and literature flourished. These writers are today referred to as the Lost Generation, a term introduced to the zeitgeist by Ernest Hemingway, who credited Gertrude Stein with coming up with it. The books that came out it? Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence , F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby , and Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises , with its defense of his disadvantaged generation’s resilience.)

We Nomadists have a keen obsession with the idea of home, locating it in its nonexistence, in the futile and tragic search for it. In “Seafarers,” Adeoba situates us within the imagery of the liminal as an ironic replacement for home:

Bordered by kelp— brown murals supple as wool— and a cloud of winged witnesses, our boat is somewhere in the middle of the Mediterranean, miles and miles from the coast near Tobruk in Libya, where we had camped until the smugglers and the sea spoke of its fidelity.

In “The Sea Dreams of Us,” Oriogun presents the body, the one physical thing that we can all lay claim to, as a more reliable marker of heritage than allegiance to one’s country, to the arbitrary borders of nationhood:

The girl laughs at the sea, saying, our bodies are countries outside of borders. We watch the night, the return of boats, the sky above Accra. The horizon beckons, the ship waits with our journey. What have you given up? I ask her. Exile is also silence—she says.

In “my mother makes memories crawl on my skin,” Okpara expresses his bitterness at his countrymen’s contribution to his stifling, his inability to express sexual want without fear of consequence:

i pay the conductor whose eyes hold beauty & charm whose arms i want to make a home he takes the money i begin to wonder where the pain aches more & if i could run my tongue on him in search of the fire that burns i know he finds joy elsewhere other than home . . . a passenger starts to pray he asks god for journey mercies i bite my lips & pray that god neglects their prayers like he does mine.

I call these writers Nomadists because of their complication of nationalism and their geographical movements in search of fresh pasture for the livestock that is their art. They are unencumbered by any ties to nationhood because of, among other things, the absence of an urgent postcolonial reality, military rule, or the pressure to be in conversation with previous generations. They have no inclination toward a nationalist aesthetic, not for the sake of a country that has failed them and their parents. One might argue that the rebelliousness of the Fourth Generation of Nigerian literature peaks with the Nomadists.

The Fourth Generation writers are shapeshifters, always rejecting or renegotiating terms that do not suit them. No previous generation had been so thoroughly defined by its appetite for adventure and resistance to definition. They are also changing our understanding of genres. In their hands, speculative fiction has become more integral to Nigerian literature. (One could argue that it is exactly their disillusionment with Nigerianness that leads many of them to seek out fashioned worlds that ignore or significantly alter the reality of what it is to be Nigerian.)

They have an unbound ability to explore territories for artistic inspiration. It is what has allowed them to be confessional. It is what has enabled them to center queer desire, queer life, queer be-ing in a way that had never been done before. And it is why the Nomadists among them now produce poetry that could be attributed to poets of almost any other nationality — how they are able to give voice to their larger generation’s jápa ambitions. (For a fuller understanding of this variety, one need only look at Open Country Mag ‘s The Next Generation series.)

We can, and should, have several traditions and subcultures within the same period in Nigerian literature. The Nativists and the Nomadists have different approaches and that is what makes our literature alive. But the Nativists have to acknowledge that the Nomadists are as Nigerian and are making a different and indispensable contribution by reflecting society.

I want us to deepen this conversation about subcultures. Not all writers in jápa mode are disconnected enough from nationalistic concerns to be called Nomadist. But do the ones who are consider themselves so? Why not publish an anthology under whatever name they deem themselves? I am interested in the new trends, the shifts, that this generation will contribute to the evolution of our literature. There is uncertainty about the path they will take us on — getting published is an uncertain path and there are challenges of building infrastructure at home — but it is dizzying. The future of Nigerian literature is positively terrifying. Our literature is alive.

I suppose what is dying is the enthusiasm paid toward the work we are creating. No one is obligated to read what or who does not interest them. But there is a fine line between dismissing people’s work and erasing it entirely. So we need to actually engage the work we are critiquing, and our critiques need to go beyond binaries. We need to think clearer about how we are thinking about Nigerian literature. ♦

Edited by Otosirieze.

More Essays & Fiction from Open Country Mag

— River Spirit by Leila Aboulela

— “ The Nigerian Oppression, as Chinua Achebe Would See It ”: Emmanuel Esomnofu

— The Quality of Mercy by Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu

— Between Starshine and Clay by Sarah Ladipo Manyika

— “ Revel, Again, in the Beautiful Absurd ”: Ernest Ogunyemi

— Black and Female by Tsitsi Dangarembga

— Sankofa by Chibundu Onuzo

— We Once Belonged to the Sea by Diriye Osman

— “Creating a New Tradition in African Poetry”: 20.35 Africa VI : Introduction

— Biracial Britain: A Different Way of Looking at Race by Remi Adekoya

— The Fugitives by Jamal Mahjoub

I joined the infamous coterie of Nigerian writers who found refuge within the grand, slave-built walls of American universities, in hopes of securing the much-loved, much-loathed M.F.A. degree.

To be a Nigerian Literary Immigrant is to be a traitor of sorts, some now imply. It is to be a new kind of punching bag. Your association with Western culture is a blemish on your authenticity, and fellow writers wonder if the literature you create should be considered part of the national canon.

Aigbokhaevbolo’s essay has been followed mostly by tepid pushbacks or, well, tweets or, worst, agreements: Our literature has died again. The glory days are always behind us.

The emigration of writers is not a Nigerian thing. From everywhere else writers are emigrating to the West, which has the structure to support it in small ways. This is a positive thing.