- Professional development

- Planning lessons and courses

Planning a writing lesson

Writing, unlike speaking, is not an ability we acquire naturally, even in our first language - it has to be taught. Unless L2 learners are explicitly taught how to write in the new language, their writing skills are likely to get left behind as their speaking progresses.

But teaching writing is not just about grammar, spelling, or the mechanics of the Roman alphabet. Learners also need to be aware of and use the conventions of the genre in the new language.

What is genre?

Generating ideas

Focusing ideas

Focus on a model text

Organising ideas

- Peer evaluation

A genre can be anything from a menu to a wedding invitation, from a newspaper article to an estate agent's description of a house. Pieces of writing of the same genre share some features, in terms of layout, level of formality, and language. These features are more fixed in formal genre, for example letters of complaint and essays, than in more 'creative' writing, such as poems or descriptions. The more formal genre often feature in exams, and may also be relevant to learners' present or future 'real-world' needs, such as university study or business. However, genre vary considerably between cultures, and even adult learners familiar with a range of genre in their L1 need to learn to use the conventions of those genre in English.

Stages of a writing lesson

I don't necessarily include all these stages in every writing lesson, and the emphasis given to each stage may differ according to the genre of the writing and / or the time available. Learners work in pairs or groups as much as possible, to share ideas and knowledge, and because this provides a good opportunity for practising the speaking, listening and reading skills.

This is often the first stage of a process approach to writing. Even when producing a piece of writing of a highly conventional genre, such as a letter of complaint, using learners' own ideas can make the writing more memorable and meaningful.

- Before writing a letter of complaint, learners think about a situation when they have complained about faulty goods or bad service (or have felt like complaining), and tell a partner.

- As the first stage of preparing to write an essay, I give learners the essay title and pieces of scrap paper. They have 3 minutes to work alone, writing one idea on each piece of paper, before comparing in groups. Each group can then present their 3 best ideas to the class. It doesn't matter if the ideas aren't used in the final piece of writing, the important thing is to break through the barrier of ' I can't think of anything to write.'

This is another stage taken from a process approach, and it involves thinking about which of the many ideas generated are the most important or relevant, and perhaps taking a particular point of view.

- As part of the essay-writing process, students in groups put the ideas generated in the previous stage onto a 'mind map'. The teacher then draws a mind-map on the board, using ideas from the different groups. At this stage he / she can also feed in some useful collocations - this gives the learners the tools to better express their own ideas.

- I tell my students to write individually for about 10 minutes, without stopping and without worrying about grammar or punctuation. If they don't know a particular word, they write it in their L1. This often helps learners to further develop some of the ideas used during the 'Generating ideas' stage. Learners then compare together what they have written, and use a dictionary, the teacher or each other to find in English any words or phrases they wrote in their L1.

Once the students have generated their own ideas, and thought about which are the most important or relevant, I try to give them the tools to express those ideas in the most appropriate way. The examination of model texts is often prominent in product or genre approaches to writing, and will help raise learners' awareness of the conventions of typical texts of different genres in English.

- I give learners in groups several examples of a genre, and they use a genre analysis form to identify the features and language they have in common. This raises their awareness of the features of the genre and gives them some language 'chunks' they can use in their own writing. Genre analysis form 54k

- reason for writing

- how I found out about the job

- relevant experience, skills and abilities

- closing paragraph asking for an interview

- Learners are given an essay with the topic sentences taken out, and put them back in the right place. This raises their awareness of the organisation of the essay and the importance of topic sentences.

Once learners have seen how the ideas are organised in typical examples of the genre, they can go about organising their own ideas in a similar way.

- Students in groups draft a plan of their work, including how many paragraphs and the main points of each paragraph. These can then be pinned up around the room for comment and comparison.

- When preparing to write an essay, students group some of the ideas produced earlier into main and supporting statements.

In a pure process approach, the writer goes through several drafts before producing a final version. In practical terms, and as part of a general English course, this is not always possible. Nevertheless, it may be helpful to let students know beforehand if you are going to ask them to write a second draft. Those with access to a word processor can then use it, to facilitate the redrafting process. The writing itself can be done alone, at home or in class, or collaboratively in pairs or groups. Peer evaluation

Peer evaluation of writing helps learners to become aware of an audience other then the teacher. If students are to write a second draft, I ask other learners to comment on what they liked / didn't like about the piece of work, or what they found unclear, so that these comments can be incorporated into the second draft. The teacher can also respond at this stage by commenting on the content and the organisation of ideas, without yet giving a grade or correcting details of grammar and spelling.

When writing a final draft, students should be encouraged to check the details of grammar and spelling, which may have taken a back seat to ideas and organisation in the previous stages. Instead of correcting writing myself, I use codes to help students correct their own writing and learn from their mistakes. Error correction code 43k

By going through some or all of these stages, learners use their own ideas to produce a piece of writing that uses the conventions of a genre appropriately and in so doing, they are asked to think about the audience's expectations of a piece of writing of a particular genre, and the impact of their writing on the reader.

If you have any ideas that you feel have successfully helped your students to develop their writing why not add them as a comment below and share them.

Further reading

A process genre approach to teaching writing by Badger, Richards and White. ELT Journal Volume 54(2), pp. 153-160 Writing by T Hedge. Oxford University Press. Writing by C Tribble. Oxford University Press Process writing by R White and V Arndt. Longman

Really innovative

- Log in or register to post comments

It was very informative and…

It was very informative and helpful

Interesting article.

Useful information

This is a very nice and…

This is a very nice and informative article.

Thanks for this amazing article

Planning a Writing Lesson Plan

I believe this will make the lesson not only productive but also interesting. Thank you.

Thanks for a very interesting

Thanks for a very interesting and useful article.

Ideas first, then language

Thanks for sharing the plan~

I found in my class that it is always 'Ideas firt, then language follows', similar to L1 writing.

Dear Catherine,

I found your article very useful and I love the advice you give. When I ask my students to write an essay, I tend to correct their mistakes for them and after reading the article I realized that I should be doing it the way you suggested. I learned from my mistakes by finding them out and correcting them not having them corrected for me.

Thank you for a wonderful article.

I am grateful for you for this great article

Research and insight

Browse fascinating case studies, research papers, publications and books by researchers and ELT experts from around the world.

See our publications, research and insight

Implementing the Writing Process

About this Strategy Guide

This strategy guide explains the writing process and offers practical methods for applying it in your classroom to help students become proficient writers.

Research Basis

Strategy in practice, related resources.

The writing process—prewriting, drafting, revising and editing, rewriting, publishing—mirrors the way proficient writers write. In using the writing process, your students will be able to break writing into manageable chunks and focus on producing quality material. The final stage, publishing, ensures that students have an audience. Students can even coach each other during various stages of the process for further emphasis on audience and greater collaboration during editing. Studies show that students who learn the writing process score better on state writing tests than those who receive only specific instruction in the skills assessed on the test. This type of authentic writing produces lifelong learners and allows students to apply their writing skills to all subjects. Success in writing greatly depends on a student’s attitude, motivation, and engagement. The writing process takes these elements into account by allowing students to plan their writing and create a publishable, final draft of their work of which they can be proud. It addresses students’ need for a real audience and to take the time to draft and redraft their work. You can help your students think carefully about each stage of their writing by guiding them through the writing process repeatedly throughout the year and across various content areas.

The writing process involves teaching students to write in a variety of genres, encouraging creativity, and incorporating writing conventions. This process can be used in all areas of the curriculum and provides an excellent way to connect instruction with state writing standards. The following are ways to implement each step of the writing process:

- Prewriting—This step involves brainstorming, considering purpose and goals for writing, using graphic organizers to connect ideas, and designing a coherent structure for a writing piece. For kindergarten students, scribbling and invented spelling are legitimate stages of writing development; the role of drawing as a prewriting tool becomes progressively less important as writers develop. Have young students engage in whole-class brainstorming to decide topics on which to write. For students in grades 3-5, have them brainstorm individually or in small groups with a specific prompt, such as, “Make a list of important people in your life,” for example. Online graphic organizers might help upper elementary students to organize their ideas for specific writing genres during the prewriting stage. Examples are the Essay Map , Notetaker , or Persuasion Map .

- Drafting—Have students work independently at this stage. Confer with students individually as they write, offering praise and suggestions while observing areas with which students might be struggling and which might warrant separate conference time or minilessons.

- Revising and Editing—Show students how to revise specific aspects of their writing to make it more coherent and clear during minilessons. You can model reading your own writing and do a think aloud about how you could add more details and make it clearer. Teach students to reread their own work more than once as they think about whether it really conveys what they want to their reader. Reading their work aloud to classmates and other adults helps them to understand what revisions are needed. Your ELLs will develop greater language proficiency as they collaborate with their peers when revising.

- Rewriting—Have students incorporate changes as they carefully write or type their final drafts.

Rubrics help to make expectations and grading procedures clear, and provide a formative assessment to guide and improve your instruction. The Sample Writing Rubric , for example, can be used for upper elementary students.

As you work with your students to implement the writing process, they will begin to master writing and take it into all aspects of life. Peer review, with clear guidelines for students to give feedback on each other’s work, motivates students, allows them to discuss their writing with their peers, and makes the work load a little lighter for you. The Peer Edit with Perfection! PowerPoint Tutorial is a useful tool to teach students how to peer review and edit. You can also have students can edit their own work using a checklist, such as the Editing Checklist . Editing is when students have already revised content but need to correct mistakes in terms of spelling, grammar, sentence structure, punctuation, and word choice. Use minilessons, small-group lessons, or individual conferencing if necessary to make sure that students have made thoughtful changes to their writing content before moving on to the final draft.

- Publishing—Encourage students to publish their works in a variety of ways, such as a class book, bulletin board, letters to the editor, school newsletter, or website. The ReadWriteThink Printing Press tool is useful for creating newspapers, brochures, flyers and booklets. Having an authentic audience beyond the classroom gives student writing more importance and helps students to see a direct connection between their lives and their literacy development.

- Lesson Plans

- Student Interactives

- Calendar Activities

It's not easy surviving fourth grade (or third or fifth)! In this lesson, students brainstorm survival tips for future fourth graders and incorporate those tips into an essay.

Students are encouraged to understand a book that the teacher reads aloud to create a new ending for it using the writing process.

While drafting a literary analysis essay (or another type of argument) of their own, students work in pairs to investigate advice for writing conclusions and to analyze conclusions of sample essays. They then draft two conclusions for their essay, select one, and reflect on what they have learned through the process.

The Essay Map is an interactive graphic organizer that enables students to organize and outline their ideas for an informational, definitional, or descriptive essay.

The Persuasion Map is an interactive graphic organizer that enables students to map out their arguments for a persuasive essay or debate.

The Stapleless Book can be used for taking notes while reading, making picture books, collecting facts, or creating vocabulary booklets . . . the possibilities are endless!

Students examine the different ways that they write and think about the role writing plays in life.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

The Writing Process

The Writing Process Explained

Understanding the writing process provides a student with a straightforward step-by-step procedure that they can follow. It means they can replicate the process no matter what type of nonfiction text they are asked to produce.

In this article, we’ll look at the 5 step writing process that guides students from prewriting to submitting their polished work quickly and easily.

While explaining each stage of the process in detail, we’ll suggest some activities you can use with your students to help them successfully complete each stage.

THE STAGES OF THE WRITING PROCESS

The five steps of the writing process are made up of the following stages:

- Pre-writing: In this stage, students brainstorm ideas, plan content, and gather the necessary information to ensure their thinking is organized logically.

- Drafting: Students construct ideas in basic sentences and paragraphs without getting caught up with perfection. It is in this stage that the pre-writing process becomes refined and shaped.

- Revising: This is where students revise their draft and make changes to improve the content, organization, and overall structure. Any obvious spelling and grammatical errors might also be improved at this stage.

- Editing: It is in this stage where students make the shift from improving the structure of their writing to focusing on enhancing the written quality of sentences and paragraphs through improving word choice, punctuation, and capitalization, and all spelling and grammatical errors are corrected. Ensure students know this is their final opportunity to alter their writing, which will play a significant role in the assessment process.

- Submitting / Publishing: Students can share their writing with the world, their teachers, friends, and family through various platforms and tools.

Be aware that this list is not a definitive linear process, and it may be advisable to revisit some of these steps in some cases as students learn the craft of writing over time.

Daily Quick Writes For All Text Types

Our FUN DAILY QUICK WRITE TASKS will teach your students the fundamentals of CREATIVE WRITING across all text types. Packed with 52 ENGAGING ACTIVITIES

STAGE ONE: THE WRITING PROCESS

GET READY TO WRITE

The prewriting stage covers anything the student does before they begin to draft their text. It includes many things such as thinking, brainstorming, discussing ideas with others, sketching outlines, gathering information through interviewing people, assessing data, and researching in the library and online.

The intention at the prewriting stage is to collect the raw material that will fuel the writing process. This involves the student doing 3 things:

- Understanding the conventions of the text type

- Gathering up facts, opinions, ideas, data, vocabulary, etc through research and discussion

- Organizing resources and planning out the writing process.

By the time students have finished the pre-writing stage, they will want to have completed at least one of these tasks depending upon the text type they are writing.

- Choose a topic: Ensure your students select a topic that is interesting and relevant to them.

- Brainstorm ideas: Once they have a topic, brainstorm and write their ideas down, considering what they already know about the topic and what they need to research further. Students might want to use brainstorming techniques such as mind mapping, free writing, or listing.

- Research: This one is crucial for informational and nonfiction writing. Students may need to research to gather more information and use reliable sources such as books, academic journals, and credible websites.

- Organize your ideas: This can be challenging for younger students, but once they have a collection of ideas and information, help them to organize them logically by creating an outline, using headings and subheadings, or grouping related ideas.

- Develop a thesis statement: This one is only for an academic research paper and should clearly state your paper’s main idea or argument. It should be specific and debatable.

Before beginning the research and planning parts of the process, the student must take some time to consider the demands of the text type or genre they are asked to write, as this will influence how they research and plan.

PREWRITING TEACHING ACTIVITY

As with any stage in the writing process, students will benefit immensely from seeing the teacher modelling activities to support that stage.

In this activity, you can model your approach to the prewriting stage for students to emulate. Eventually, they will develop their own specific approach, but for now, having a clear model to follow will serve them well.

Starting with an essay title written in the center of the whiteboard, brainstorm ideas as a class and write these ideas branching from the title to create a mind map.

From there, you can help students identify areas for further research and help them to create graphic organizers to record their ideas.

Explain to the students that while idea generation is an integral part of the prewriting stage, generating ideas is also important throughout all the other stages of the writing process.

STAGE TWO: THE WRITING PROCESS

PUT YOUR IDEAS ON PAPER

Drafting is when the student begins to corral the unruly fruits of the prewriting stage into orderly sentences and paragraphs.

When their writing is based on solid research and planning, it will be much easier for the student to manage. A poorly executed first stage can see pencils stuck at the starting line and persistent complaints of ‘writer’s block’ from the students.

However, do encourage your students not to get too attached to any ideas they may have generated in Stage 1. Writing is thinking too and your students need to leave room for their creativity to express itself at all stages of the process.

The most important thing about this stage is for the student to keep moving. A text is written word-by-word, much as a bricklayer builds a wall by laying brick upon brick.

Instill in your students that they shouldn’t get too hung up on stuff like spelling and grammar in these early stages.

Likewise, they shouldn’t overthink things. The trick here is to get the ideas down fast – everything else can be polished up later.

DRAFTING TEACHING ACTIVITY

As mentioned in the previous activity, writing is a very complex process and modeling goes a long way to helping ensure our students’ success.

Sometimes our students do an excellent job in the prewriting stage with understanding the text purpose, the research, and the planning, only to fall flat when it comes to beginning to write an actual draft.

Often, students require some clear modeling by the teacher to help them transition effectively from Stage 1 to Stage 2.

One way to do this for your class is to take the sketches, notes, and ideas one of the students has produced in Stage 1, and use them to model writing a draft. This can be done as a whole class shared writing activity.

Doing this will help your students understand how to take their raw material and connect their ideas and transition between them in the form of an essay.

STAGE THREE: THE WRITING PROCESS

POLISH YOUR THINKING

In Stage two, the emphasis for the student was on getting their ideas out quickly and onto the paper.

Stage three focuses on refining the work completed earlier with the reader now firmly at the forefront of the writer’s mind.

To revise, the student needs to cast a critical eye over their work and ask themselves questions like:

- Would a reader be able to read this text and make sense of it all?

- Have I included enough detail to help the reader clearly visualize my subject?

- Is my writing concise and as accurate as possible?

- Are my ideas supported by evidence and written in a convincing manner?

- Have I written in a way that is suitable for my intended audience?

- Is it written in an interesting way?

- Are the connections between ideas made explicit?

- Does it fulfill the criteria of the specific text type?

- Is the text organized effectively?

The questions above represent the primary areas students should focus on at this stage of the writing process.

Students shouldn’t slip over into editing/proofreading mode just yet. Let the more minor, surface-level imperfections wait until the next stage.

REVISING TEACHING ACTIVITY

When developing their understanding of the revising process, it can be extremely helpful for students to have a revision checklist to work from.

It’s also a great idea to develop the revision checklist as part of a discussion activity around what this stage of the writing process is about.

Things to look out for when revising include content, voice, general fluency, transitions, use of evidence, clarity and coherence, and word choice.

It can also be a good idea for students to partner up into pairs and go through each other’s work together. As the old saying goes, ‘two heads are better than one’ and, in the early days at least, this will help students to use each other as sounding boards when making decisions on the revision process.

STAGE FOUR: THE WRITING PROCESS

CHECK YOUR WRITING

Editing is not a different thing than writing, it is itself an essential part of the writing process.

During the editing stage, students should keep an eagle eye out for conventional mistakes such as double spacing between words, spelling errors, and grammar and punctuation mistakes.

While there are inbuilt spelling and grammar checkers in many of the most popular word processing programs, it is worth creating opportunities for students to practice their editing skills without the crutch of such technology on occasion.

Students should also take a last look over the conventions of the text type they are writing.

Are the relevant headings and subheadings in place? Are bold words and captions in the right place? Is there consistency across the fonts used? Have diagrams been labelled correctly?

Editing can be a demanding process. There are lots of moving parts in it, and it often helps students to break things down into smaller, more manageable chunks.

Focused edits allow the student the opportunity to have a separate read-through to edit for each of the different editing points.

For example, the first run-through might look at structural elements such as the specific structural conventions of the text type concerned. Subsequent run-throughs could look at capitalization, grammar, punctuation , the indenting of paragraphs, formatting, spelling, etc.

Sometimes students find it hard to gain the necessary perspective to edit their work well. They’re simply too close to it, and it can be difficult for them to see what is on the paper rather than see what they think they have put down.

One good way to help students gain the necessary distance from their work is to have the student read their work out loud as they edit it.

Reading their work out loud forces the student to slow down the reading process and it forces them to pay more attention to what’s written on the page, rather than what’s in their head.

It’s always helpful to get feedback from someone else. If time permits, get your students to ask a friend or other teacher to review their work and provide feedback. They may catch errors or offer suggestions your students haven’t considered.

All this gives the student a little more valuable time to catch the mistakes and other flaws in their work.

WRITING CHECKLISTS FOR ALL TEXT TYPES

EDITING TEACHING ACTIVITY

Students must have a firm understanding of what they’re looking to correct in the editing process to edit effectively. One effective way to ensure this understanding is to have them compile an Editing Checklist for use when they’re engaged in the editing process.

The Editing Checklist can be compiled as a whole-class shared writing activity. The teacher can scribe the students’ suggestions for inclusion on the checklist onto the whiteboard. This can then be typed up and printed off by all the students.

A fun and productive use of the checklist is for the students to use it in ‘editing pairs’.

Each student is assigned an editing partner during the editing stage of a writing task. Each student goes through their partner’s, work using the checklist as a guide, and then gives feedback to the other partner. The partner, in turn, uses the feedback in the final edit of their work.

STAGE FIVE: THE WRITING PROCESS

HAND IN YOUR WRITING

Now, it’s time for our students’ final part of the writing process. This is when they hand in their work to their teacher – aka you !

At this point, students should have one final reread of their work to ensure it’s as close to their intentions as possible, and then, finally, they can submit their work.

Giving the work over to an audience, whether that audience comes in the form of a teacher marking an assignment, publishing work in print or online, or making a presentation to classmates, can be daunting. It’s important that students learn to see the act of submitting their work as a positive thing.

Though this is the final stage of the writing process, students should be helped to see it for all it is. It is another step in the journey towards becoming a highly-skilled writer. It’s a further opportunity for the student to get valuable feedback on where their skills are currently at and a signpost to help them to improve their work in the future.

When the feedback comes, whether that’s in the form of teacher comments, grades, reviews, etc it should be absorbed by the student as a positive part of this improvement process.

Submitting TEACHING Activity

This activity is as much for the teacher as it is for the student.

Sometimes, our students think of feedback as a passive thing. The teacher makes some comments either in writing or orally and the student listens and carries on largely as before. We must help our students to recognize feedback as an opportunity for growth.

Feedback should be seen as a dialogue that helps our students to take control of their own learning.

For this to be the case, students need to engage with the feedback they’ve been given, to take constructive criticisms on board, and to use these as a springboard to take action.

One way to help students to do this lies in the way we format our feedback to our students. A useful format in this vein is the simple 2 Stars and a Wish . This format involves giving feedback that notes two specific areas of the work that the student did well and one that needs improvement. This area for improvement will provide a clear focus for the student to improve in the future. This principle of constructive criticism should inform all feedback.

It’s also helpful to encourage students to process detailed feedback by noting specific areas to focus on. This will give them some concrete targets to improve their writing in the future.

VIDEO TUTORIAL ON THE WRITING PROCESS

And there we have it. A straightforward and replicable process for our students to follow to complete almost any writing task.

But, of course, the real writing process is the ongoing one whereby our students improve their writing skills sentence-by-sentence and word-by-word over a whole lifetime.

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES RELATED TO THE WRITING PROCESS

7 Evergreen Writing Activities for Elementary Students

Text Types and Different Styles of Writing: The Complete Guide

Top 5 Essay Writing Tips

7 ways to write great Characters and Settings | Story Elements

6 Simple Writing Lessons Students Will Love

Literacy Lines

Home » Literacy Lines » Stages of the Writing Process

Stages of the Writing Process

Beginning in the 1960’s, Hayes and Flower (1980) researched the steps that proficient writers take in order to better understand how to teach writing. They initially developed a model of the writing process with three stages: planning , translating , and reviewing . Over the years, the model was informed by new research and modified to include four stages (Hayes, 1996, 2004): Pre-Writing, Text Production, Revising, Editing. Today, it is accepted practice that students be taught to follow the stages of the writing process when they write.

One of the Common Core anchor writing standards focuses on the writing process : Develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach. The Institute of Education Sciences research guide Teaching Elementary School Students to Be Effective Writers (Graham et al., 2012) recommends teaching students to use the writing process for a variety of purposes, noting, “It is a process that requires that the writer think carefully about the purpose for writing, plan what to say, plan how to say it, and understand what the reader needs to know.” The report goes on to explain, “Writing is not a linear process, like following a recipe to bake a cake. It is flexible; writers should learn to move easily back and forth between components of the writing process, often altering their plans and revising their text along the way. Components of the writing process include planning, drafting, sharing, evaluating, revising, and editing.” (pp 12, 14)

Teaching the Stages of the Writing Process

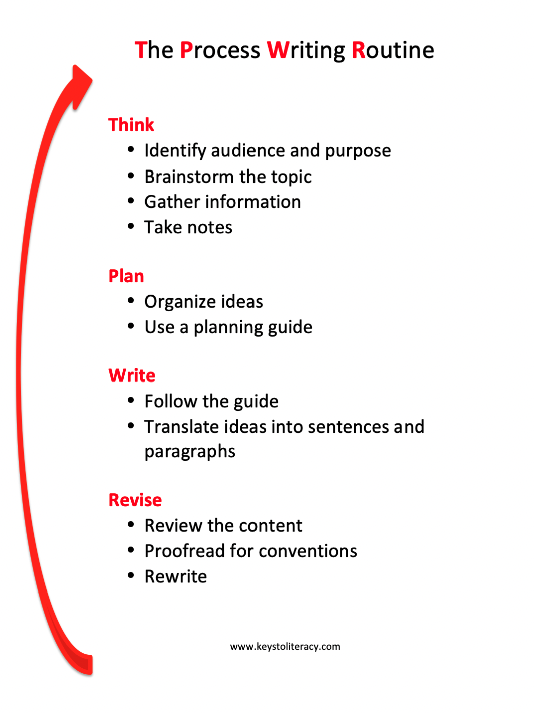

Ten years ago I proposed a model for teaching the writing process that includes four stages: THINK , PLAN , WRITE , REVISE . The title of this model, T he P rocess W riting R outine , is designed to help students recall the stages of the writing process by linking the four stages to the first letters of the words in the title. The graphic below shows the four stages with details about the tasks associated with each stage. One of the modules in the Keys to Content Writing professional development course is focused on the stages of the writing process Click here to access a copy of this handout from the free resources section of the Keys to Literacy website.

As the IES guide notes, writers repeat and revisit the stages several times as they develop a piece of writing. For example, students may realize while they are writing a first draft of an informational piece that they need to go back to the THINK stage to gather more information about the topic. While revising the draft, they may determine that they need to go back to the PLAN stage to reorganize the content. The arrow serves as a reminder that writing stages are overlapping parts of a process that may be repeated multiple times as writing unfolds.

It is helpful to provide a visual reminder of the writing process to students such as displaying The Process Writing Routine in a classroom anchor chart, as a handout for students to keep in their notebooks, or as a digital resource file. The poster shown below is available from Keys to Literacy .

Too often, students assume the focus of their attention should be on writing. They do not spend sufficient time at the THINK and PLAN stages, or they skip them altogether. The amount of time spent on each stage will vary depending on the writing task, but a common recommendation is to spend 40% of the time reading, gathering ideas and information, and taking notes (THINK and PLAN); 20% of the time draft writing (WRITE); and 40% of the time rewriting and revising, including editing for conventions (REVISE). Students need to learn that in most cases, spending more time at the THINK and PLAN stages will produce a better writing draft and save time at the REVISE stage.

Introducing the Stages to Young Students

I have simplified the stages for young students in the primary grades, as shown below and addressed in one of the modules in the Keys to Early Writing professional development course. The more basic model combines the first two stages and includes visual cues. A copy of this graphic is available at the free resources section of the Keys to Literacy website.

Students in kindergarten and grade 1 may not be developmentally ready to formally revise their work and instead may focus their editing on adding more to their drawings, labels, phrases, or sentences. View the suggestions below for introducing young students to the stages of the writing process.

- Generating Ideas and Organizing: What do I want to say? How will I present what I want to say?

- Using Drawing and Words: How can I use drawings, words, and sentences to communicate what I want to say?

- Improving: Can I add more detail to my drawing or words?

Teaching Students Strategies for Each Stage of the Writing Process

Research consistently confirms that teaching strategies to students for planning, revising, and editing their writing pieces can have a dramatic effect on the quality of their writing (Graham & Perin, 2007; Graham et al., 2012; Graham et al., 2017). Strategy instruction involves explicitly teaching generic processes such as peer collaboration or note taking, or strategies for accomplishing specific types of writing tasks such as writing a summary or a story. Some strategies incorporate a scaffold such as a graphic organizer or a writing template. The following earlier blog posts provide instructional suggestions for writing strategies:

- Teaching Text Structure to Support Writing and Comprehension

- The Might Paragraph

- Teaching Handwriting

- The Power of Transition Words

- Syntactic Awareness: Teaching Sentence Structure Part 1

- Syntactic Awareness: Teaching Sentence Structure Part 2

- Explicit Instruction of Note Taking Skills

- Patterns of Organization

RELATED RESOURCES

- Vide o: Teach Students to Use the Writing Process for a Variety of Purposes (Institute of Education Sciences)

- The Writing Process (University of Kansas Writing Center)

- Stages of the Writing Process (Purdue Online Writing Lab)

- Graham, S., Bollinger, A., Booth Olson, C., D’Aoust, C., MacArthur, C., McCutchen, D., & Olinghouse, N. (2012). Teaching elementary school students to be effective writers: A practice guide (NCEE 2012- 4058). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- Graham, S., Bruch, J., Fitzgerald, J., Friedrich, L., Furgeson, J., Greene, K., Kim, J., Lyskawa, J., Olson, C.B., & Smither Wulsin, C. (2016). Teaching secondary students to write effectively (NCEE 2017-4002). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve the writing of adolescents in middle and high schools – A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

- Sedita, J. (2020). Keys to Early Writin g. Rowley, MA: Keys to Literacy.

- Sedita, J. (2020). Keys to Content Writing. Rowley, MA: Keys to Literacy.

- Joan Sedita

Leave a Reply

Cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Subscribe by Email

- Adolescent Literacy

- Brain and Literacy

- Close Reading

- College and Career Ready

- Common Core

- Complex Text

- Comprehension Instruction

- Content Literacy

- Decoding and Fluency

- Differentiated Fluency

- Differentiated Instruction

- Digital Literacies

- Disciplinary Literacy

- Elementary Literacy

- English Language Learners

- Grammar and Syntax

- High School Literacy

- Interventions

- Learning Disabilities – Dyslexia

- Middle School Literacy

- MTSS (Multi-Tiered Systems of Support)

- PK – Grade 3 Literacy

- Professional Development

- RTI (Response to Intervention)

- Special Education

- Teacher Education

- Teacher Evaluation

- Text Structures

- Uncategorized

- Vocabulary Instruction

- Writing Instruction

Posts by Author

- Becky DeSmith

- Donna Mastrovito

- Brad Neuenhaus

- Shauna Cotte

- Sue Nichols

- Amy Samelian

- Colleen Yasenchock

- Maureen Murgo

- melissa powers

- Sande Dawes

- Stephanie Stollar

ACCESSING KEYS TO LITERACY PD DURING SCHOOL CLOSURES

We are closely monitoring the covid-19 situation and the impact on our employees and the schools where we provide professional development., during this time period when onsite, face-to-face training and coaching is not possible, we offer multiple options for accessing our literacy pd content and instructional practices., if you are a current or new partner, explore our website or contact us to learn more about:.

- Live virtual training, coaching

- Facilitated and asynchronous online courses

- Free webinars and resources

[email protected] 978-948-8511

Shared Teaching

Systematic Teaching for First and Second Grade

The 5 Steps in the Writing Process

April 19, 2023 | Leave a Comment

What is the writing process?

Before we can set up our blueprint for writing, students need to understand the question, “What is the writing process?” In my class, I use planning, writing, revising, editing, and finally publishing as the 5 steps in the writing process.

By teaching students the writing process, students are aware of what their next steps will be when it comes to writing. I also teach my students that not every piece of writing needs to be revised, edited, and published. We pick and choose what goes through this process – just like our favorite published authors.

Since my class moves through the stages of the writing process at the same time, I like to keep process posters for student reference near my writing center. I know many teachers that use clothespins with student names to track where their students are in the writing process. I find this to be a lot to manage in my second grade class. You can read more about why I choose to have the class complete the stages together in my post What Is Writer’s Workshop?

Step 1: Plan

The first in the 5 steps of the writing process is the planning stage. Often this is also called the pre-writing step. I like to say we are making a plan because it makes more sense to me. For the planning stage I am teaching my students a variety of ways to make a plan.

Some of the ways we might plan:

Circle maps

Graphic organizers

Often I will model how to plan my own writing as a whole class lesson. Students will then plan their own writing independently using the same process I modeled. I strongly encourage my writers to use their own ideas and not just copy what I do. Copying is very common in kindergarten through second grade classrooms. Especially for your less seasoned writers.

Step 2: Write

During the second stage of the writing process, the writing or drafting step, students begin to put their ideas and plans into sentences and (hopefully) paragraphs. Encourage students that spelling doesn’t matter as much as getting their ideas down.

I have found that students struggling with writing often get stuck in this stage because they have trouble forming their letters or figuring out spelling. This has them taking forever to put something on the page or acting out because they just can’t do what you’re asking.

In the beginning of the school year I recommend building in some mini lessons about how to put words on paper. Even with second graders, some of your students might need this refresher after summer and because they’re new to you, they need to learn your expectations during writing time.

Step 3: Revise

After the planning and writing stages of the writing process comes revision. Teaching how to revise can be tricky with your young learners. I teach students that when we revise we are making our story better by adding details or moving, removing, or changing words. Most students naturally want to fix spelling errors at this point but I try to help them resist. Once it’s further in the year and they know to fix errors with their red writing editing pen, then I will let them.

Using writing partners during the revision stage is a crucial part of getting your students to understand the writing process. Having a partner to read their writing to can really go a long way in helping them identify any confusing parts or unclear ideas. A well-trained partner can also ask questions to help add details.

Step 4: Edit

The fourth stage of the writing process is editing. During the editing stage, students can finally focus on their mechanics of writing, or their spelling and punctuation. I encourage students to use phonetic spelling and reference our sound wall to help spell words.

Their writing partner can also help offer spelling suggestions. For first and second grade, I do not expect perfect spelling unless it is a word or pattern we have practiced and the majority of the class should know. All my students from the first day of school to the last know my expectation on capitals and periods. In other words, everyone is expected to start a sentence with a capital and end with a period. This is one of my non-negotiables for their writing.

Related Post: Editing and Revising Teaching Methods

Step 5: Publish

The last of the 5 steps of the writing process is to publish. As I mentioned earlier, I do not ask students to publish every piece of writing – that would get old pretty fast for kids! Instead, I look for breaks in my writing unit to publish. Ideally a break would be when we switch to a different style of writing. For example, in my opinion writing unit students publish an opinion paragraph, a book report, and a persuasive letter. In between publishing we are practicing several versions of these styles of writing.

Publishing is a great way to celebrate your students’ hard work and getting them proud of their new writing skills. Varying the way students publish their writing is also a great way to keep them excited and engaged during writing time.

Some ways to publish a writing piece:

Use fancy borders on their paper

Use large butcher paper for oversized stories

Make a slide show

I hope you found some clarity on teaching the 5 steps in the writing process. Using these stages is a great way to help further develop your students’ writing skills. Breaking down the writing process and cycling through it as you move through your lessons will help your students be more confident. Best of all, their upper elementary teachers will be blown away by how thoughtfully your students can plan, write, revise, edit, and publish a piece of writing!

Do you still have questions about the writing process? Let me know below.

Leave your comments cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Shared Ideas

Teaching writing | Steps of the writing process

by Kim Kautzer | May 14, 2018 | Reluctant or Struggling Writers , Teaching Homeschool Writing

T he steps of the writing process free struggling or reluctant writers from self-imposed torture. But reluctant writers aren’t the only ones who benefit. To end up with a well-written final draft, your eager, motivated writers need to take their compositions through these steps as well.

Small Steps Ensure Greater Success

Provide Structure. Though it may sound freeing, writing about “whatever you want” can actually frustrate struggling writers, so start by recommending concrete topics they can choose from. Instead of saying “write about a food,” suggest they use their five senses to describe a taco, a cinnamon roll, or an ice cream sundae.

Set Limits. Position kids for success by setting boundaries for the composition. For example, put a cap on length. This helps your struggling 12-year-old son relax a bit (“You only have to write five to seven sentences.”) But it also helps your wordy, rabbit-trailing 15-year-old daughter write more concisely (“You may only write ONE paragraph using five to seven sentences.”)

See how this works to the advantage of both kinds of writers? You’re offering the writing-phobic child safe boundaries while establishing clear limits for the rambler.

Introduce the Writing Process. Teach your kids that writing is a process , not a one-time event . If they’re trained in the process of writing, they’ll learn to view the final draft as simply one of several steps in an evolving work. And when the steps seem doable, even the most intimidated writer stands a chance at accomplishment.

Make a Plan. As you take your kids through the steps of the writing process , provide a schedule to follow. Don’t allow your procrastinators to do all the steps in one day; there’s wisdom in letting a composition rest between revisions.

Also, don’t impose the demands of the writing process on every single composition—it’s enough for one writing project at a time to go through several revisions. Break up such assignments into these five manageable steps:

1. Brainstorming

Brainstorming gets ideas flowing so your student has something to say. He might brainstorm for a how-to composition by listing the steps of the process. If he’s writing a descriptive paragraph, he must carefully study the subject for interesting details. For a narrative, he’ll want to list events in order. Whatever the topic, suggest a brainstorming method—mind map, list, or outline, for instance—that’s best for the kind of composition he’s writing.

2. Sloppy Copy

This is the just-get-it-on-paper rough draft . Perfection is not the goal. As the student writes, he’ll draw from the many ideas gathered during brainstorming. If he still can’t think of things to say, he may need to brainstorm even more. Have him skip lines so there’s room to edit later.

3. Self-Editing and Revising

I’m sure it’s no news to you that students don’t like to edit their papers . But here’s the problem: by not proofreading their own papers thoroughly , they place themselves in a no-win situation.

- They’re too lazy to edit their own work carefully,

- They really believe there’s nothing they need to change; or

- They simply assume you’ll point out their errors, so why should they bother self-editing at all?

Yet your suggestions for improvement make them feel picked on!

Self-editing is one of the most important steps of the writing process and shouldn’t be neglected. Why? It helps the student take more responsibility for his own progress.

Provide some sort of checklist as a guide to help him identify errors in content, style, and mechanics. As he compares his rough draft to the checklist, he makes corrections and improvements. The rewritten paper he turns in to you—his first revision—will then be ready for your inspection.

4. Parent Editing

Every paper benefits from a second opinion. Only after your child has had a chance to self-edit and rewrite should you offer your own advice. Don’t let this scare you! The more you edit and revise your kids’ papers, the easier it will become. You’ll soon become skilled at spotting things like repeated words, passive writing, and awkward sentence structure.

Using your own checklist helps you be objective and lets you comment on the work without squashing your child. Not only that, it takes the pressure and guesswork out of editing. And because he knows what you expect, he’ll usually respond more positively to your suggestions.

Along with tips, include plenty of positive feedback . Find ways to bless his efforts; then make gentle suggestions that encourage growth without crushing his spirit.

5. Final Draft

Now for the last step in the process —the final draft—where the student makes corrections based on your comments and puts the finishing touches on his paper. When he compares this polished version to his very first draft, what a difference he’ll see! And though he may never love the process that has brought him to this point, at least he’ll learn to respect it.

Inch by Inch, It’s a Cinch

Teaching writing doesn’t have to be hard. But as you’ve surely discovered, if you feel inadequate and insecure, writing may not be happening in your home. Recognize the need to seek out a program that offers strong parent support. Clear lesson instructions and checklists, as well as editing and grading tips, will help you feel more prepared to teach and evaluate this subject—and when you feel confident, your kids will definitely pick up on it!

Let’s Stay Connected!

Subscribe to our newsletter.

- Gift Guides

- Reluctant or Struggling Writers

- Special Needs Writers

- Brainstorming Help

- Editing & Grading Help

- Encouragement for Moms

- Writing Games & Activities

- Writing for All Subjects

- Essays & Research Papers

- College Prep Writing

- Grammar & Spelling

- Writing Prompts

Recent Posts

- An exciting announcement!

- 10 Stumbling Blocks to Writing in Your Homeschool

- Help kids with learning challenges succeed at homeschool writing

- How to correct writing lessons without criticizing your child

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Four Strategies for Effective Writing Instruction

- Share article

(This is the first post in a two-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is the single most effective instructional strategy you have used to teach writing?

Teaching and learning good writing can be a challenge to educators and students alike.

The topic is no stranger to this column—you can see many previous related posts at Writing Instruction .

But I don’t think any of us can get too much good instructional advice in this area.

Today, Jenny Vo, Michele Morgan, and Joy Hamm share wisdom gained from their teaching experience.

Before I turn over the column to them, though, I’d like to share my favorite tool(s).

Graphic organizers, including writing frames (which are basically more expansive sentence starters) and writing structures (which function more as guides and less as “fill-in-the-blanks”) are critical elements of my writing instruction.

You can see an example of how I incorporate them in my seven-week story-writing unit and in the adaptations I made in it for concurrent teaching.

You might also be interested in The Best Scaffolded Writing Frames For Students .

Now, to today’s guests:

‘Shared Writing’

Jenny Vo earned her B.A. in English from Rice University and her M.Ed. in educational leadership from Lamar University. She has worked with English-learners during all of her 24 years in education and is currently an ESL ISST in Katy ISD in Katy, Texas. Jenny is the president-elect of TexTESOL IV and works to advocate for all ELs:

The single most effective instructional strategy that I have used to teach writing is shared writing. Shared writing is when the teacher and students write collaboratively. In shared writing, the teacher is the primary holder of the pen, even though the process is a collaborative one. The teacher serves as the scribe, while also questioning and prompting the students.

The students engage in discussions with the teacher and their peers on what should be included in the text. Shared writing can be done with the whole class or as a small-group activity.

There are two reasons why I love using shared writing. One, it is a great opportunity for the teacher to model the structures and functions of different types of writing while also weaving in lessons on spelling, punctuation, and grammar.

It is a perfect activity to do at the beginning of the unit for a new genre. Use shared writing to introduce the students to the purpose of the genre. Model the writing process from beginning to end, taking the students from idea generation to planning to drafting to revising to publishing. As you are writing, make sure you refrain from making errors, as you want your finished product to serve as a high-quality model for the students to refer back to as they write independently.

Another reason why I love using shared writing is that it connects the writing process with oral language. As the students co-construct the writing piece with the teacher, they are orally expressing their ideas and listening to the ideas of their classmates. It gives them the opportunity to practice rehearsing what they are going to say before it is written down on paper. Shared writing gives the teacher many opportunities to encourage their quieter or more reluctant students to engage in the discussion with the types of questions the teacher asks.

Writing well is a skill that is developed over time with much practice. Shared writing allows students to engage in the writing process while observing the construction of a high-quality sample. It is a very effective instructional strategy used to teach writing.

‘Four Square’

Michele Morgan has been writing IEPs and behavior plans to help students be more successful for 17 years. She is a national-board-certified teacher, Utah Teacher Fellow with Hope Street Group, and a special education elementary new-teacher specialist with the Granite school district. Follow her @MicheleTMorgan1:

For many students, writing is the most dreaded part of the school day. Writing involves many complex processes that students have to engage in before they produce a product—they must determine what they will write about, they must organize their thoughts into a logical sequence, and they must do the actual writing, whether on a computer or by hand. Still they are not done—they must edit their writing and revise mistakes. With all of that, it’s no wonder that students struggle with writing assignments.

In my years working with elementary special education students, I have found that writing is the most difficult subject to teach. Not only do my students struggle with the writing process, but they often have the added difficulties of not knowing how to spell words and not understanding how to use punctuation correctly. That is why the single most effective strategy I use when teaching writing is the Four Square graphic organizer.

The Four Square instructional strategy was developed in 1999 by Judith S. Gould and Evan Jay Gould. When I first started teaching, a colleague allowed me to borrow the Goulds’ book about using the Four Square method, and I have used it ever since. The Four Square is a graphic organizer that students can make themselves when given a blank sheet of paper. They fold it into four squares and draw a box in the middle of the page. The genius of this instructional strategy is that it can be used by any student, in any grade level, for any writing assignment. These are some of the ways I have used this strategy successfully with my students:

* Writing sentences: Students can write the topic for the sentence in the middle box, and in each square, they can draw pictures of details they want to add to their writing.

* Writing paragraphs: Students write the topic sentence in the middle box. They write a sentence containing a supporting detail in three of the squares and they write a concluding sentence in the last square.

* Writing short essays: Students write what information goes in the topic paragraph in the middle box, then list details to include in supporting paragraphs in the squares.

When I gave students writing assignments, the first thing I had them do was create a Four Square. We did this so often that it became automatic. After filling in the Four Square, they wrote rough drafts by copying their work off of the graphic organizer and into the correct format, either on lined paper or in a Word document. This worked for all of my special education students!

I was able to modify tasks using the Four Square so that all of my students could participate, regardless of their disabilities. Even if they did not know what to write about, they knew how to start the assignment (which is often the hardest part of getting it done!) and they grew to be more confident in their writing abilities.

In addition, when it was time to take the high-stakes state writing tests at the end of the year, this was a strategy my students could use to help them do well on the tests. I was able to give them a sheet of blank paper, and they knew what to do with it. I have used many different curriculum materials and programs to teach writing in the last 16 years, but the Four Square is the one strategy that I have used with every writing assignment, no matter the grade level, because it is so effective.

‘Swift Structures’

Joy Hamm has taught 11 years in a variety of English-language settings, ranging from kindergarten to adult learners. The last few years working with middle and high school Newcomers and completing her M.Ed in TESOL have fostered stronger advocacy in her district and beyond:

A majority of secondary content assessments include open-ended essay questions. Many students falter (not just ELs) because they are unaware of how to quickly organize their thoughts into a cohesive argument. In fact, the WIDA CAN DO Descriptors list level 5 writing proficiency as “organizing details logically and cohesively.” Thus, the most effective cross-curricular secondary writing strategy I use with my intermediate LTELs (long-term English-learners) is what I call “Swift Structures.” This term simply means reading a prompt across any content area and quickly jotting down an outline to organize a strong response.

To implement Swift Structures, begin by displaying a prompt and modeling how to swiftly create a bubble map or outline beginning with a thesis/opinion, then connecting the three main topics, which are each supported by at least three details. Emphasize this is NOT the time for complete sentences, just bulleted words or phrases.

Once the outline is completed, show your ELs how easy it is to plug in transitions, expand the bullets into detailed sentences, and add a brief introduction and conclusion. After modeling and guided practice, set a 5-10 minute timer and have students practice independently. Swift Structures is one of my weekly bell ringers, so students build confidence and skill over time. It is best to start with easy prompts where students have preformed opinions and knowledge in order to focus their attention on the thesis-topics-supporting-details outline, not struggling with the rigor of a content prompt.

Here is one easy prompt example: “Should students be allowed to use their cellphones in class?”

Swift Structure outline:

Thesis - Students should be allowed to use cellphones because (1) higher engagement (2) learning tools/apps (3) gain 21st-century skills

Topic 1. Cellphones create higher engagement in students...

Details A. interactive (Flipgrid, Kahoot)

B. less tempted by distractions

C. teaches responsibility

Topic 2. Furthermore,...access to learning tools...

A. Google Translate description

B. language practice (Duolingo)

C. content tutorials (Kahn Academy)

Topic 3. In addition,...practice 21st-century skills…

Details A. prep for workforce

B. access to information

C. time-management support

This bare-bones outline is like the frame of a house. Get the structure right, and it’s easier to fill in the interior decorating (style, grammar), roof (introduction) and driveway (conclusion). Without the frame, the roof and walls will fall apart, and the reader is left confused by circuitous rubble.

Once LTELs have mastered creating simple Swift Structures in less than 10 minutes, it is time to introduce complex questions similar to prompts found on content assessments or essays. Students need to gain assurance that they can quickly and logically explain and justify their opinions on multiple content essays without freezing under pressure.

Thanks to Jenny, Michele, and Joy for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones are not yet available). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

elttguide.com

- Premium Content

- Publications

- Lesson Plans

4 Stages To Teach Paragraph Writing In The Classroom

Writing is a productive skill that enables students to express their feelings, thoughts, and knowledge. Students can improve their writing skills by practicing and repetition. their writing product should be monitored from the beginning of writing to the production of the final copy.

Here are the four essential stages to follow during the writing activity:

1. Pre-writing (Brainstorming and Organizing Ideas):

It’s the planning stage of writing during which you determine the topic and elicit all possible ideas to tackle when writing about this topic. You can write these ideas randomly on the board and you may use ideas’ maps to show them all. Then, with the help of students, you should organize the ideas telling students which idea to tackle first, second, etc. until the last one.

E.g. if the topic is “loyalty”, you can organize the ideas as follows:

- What loyalty means.

- Why it is important.

- Examples of loyalty.

- How to develop it.

2. Writing (Creating the First Draft):

In this stage, ask students to write the paragraph and tackle the ideas that were agreed upon in the first stage. Ask them just to focus on writing and expressing their feelings, thoughts, and knowledge without fear of making mistakes whether in spelling or in grammar. It is better here to specify a certain time to finish writing and stick to it.

3. Revising (Sharing for Editing):

Students, in this stage, share their writing products with one another. Sharing here is a good way for students to recognize writing as an effective tool of communication. Students make discussions with each other about their writing. They make corrections and give feedback to each other. You may show a revising checklist for students to depend on when reviewing the writing pieces in this stage.

4. Re-writing (Producing the Final Copy):

In this stage, students get their writing products with corrections. Ask students to rewrite the paragraph making the corrections needed. At last, they should deliver you the final copy of their writing to grade and give them any other feedback later.

Want to know how to teach writing using the process approach?!

Here is my book:

Teaching the Writing Process to ESL/EFL Learners.

I created this eBook because many teachers asked me for some material to help them approach their students’ writing in a more effective way so I have written this eBook which is considered as a practical guide to teaching the five stages of the writing process in the classroom.

In this eBook, teachers can find lesson plans, activities, tips, and ideas to apply in the classroom to improve and enhance their students’ writing skills.

This guide leads the teachers through the five-stage process of writing by providing them with the steps to focus on in each stage.

It took me long nights and weekends to create this information product only for teachers who are struggling in teaching writing in the classroom.

I tried my best to write something practical or at least something that bridges the gap between theory and application. What a good feeling that was when I proved success achieving that by including step-by-step procedures, examples and ready-for-print lesson plans for teachers to follow while teaching the writing process in the classroom.

So, if you have been feeling a bit STUCK in teaching writing in the classroom and wondering what the solution is, this eBook is for you.

This eBook is for all teachers whether those who are getting started teaching writing classes or those who have some experience in teaching writing in the classroom.

Even if you have been unable to teach writing and gave up, this eBook will help you!

Get The Book Now

Thanks for reading.

Liked This Article?

Share It With Your Networks.

You can also join my email list not only to be notified of the latest updates on elttguide.com but also to get TWO of my products : Quick-Start Guide To Teaching Listening In The Classroom & Quick-Start Guide To Teaching Grammar In The Classroom For FREE!

Join My Email List Now (It’s FREE)!

Want to continue your elt professional development.

I offer various ELT publications on teaching English as a foreign language.

In these publications, I put the gist of my experience in TEFL for +20 years with various learners and in various environments and cultures.

The techniques and tips in these publications are sure-fire teaching methods that worked for me well and they can work for you, as well, FOR SURE.

Go ahead and get a look at these publications to know more about each one of them and the problem & challenge each one focuses on to overcome.

Then, you can get what you have an interest in. It is very easy and cheap. You can afford it and you’ll never regret it if you decide to get one of them, FOR SURE.

Now, click to get a look at my Publications

If you like it, share it on:.

Inspirational piece of work.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Subscribe to My Newsletter

Affiliate disclosure.

This website might have affiliate links, and if you buy something by clicking on them, the website owner could earn some money. To learn more, read the full disclosure.

Study TEFL/TESOL Online

Get 15% Discount

Visit My Video Channel

Articles Categories

- Back To School

- Brain-based ELT

- Classroom Management

- CLT Communicative Language Teaching

- Correcting Mistakes

- Develop Students' Speaking Skills

- Developing Critical Thinking

- Developing Life Skills

- ELT Snippets

- ELTT Questions & Answers

- For IELTS Exam

- Guest Posts

- Job Interview Preparation

- Lanaguage Teaching Approaches

- Learning How to Learn

- Lesson Planning

- Low Achiever Students

- Online Courses

- Printables Library

- Professional Development

- Talk on Supervision

- Teach Conversations

- Teach Grammar

- Teach Language Functions

- Teach Listening Activities

- Teach Pronunciation

- Teach Reading

- Teach Vocabulary

- Teach Writing

- Teacher Wellness

- Teaching Aids

- TEFL Essential Skills

- TEFL to Young Learners

- Testing and Assessment

- The ELT Insider

- Uncategorized

- Using Technology in EFL Classes

The Write Stuff Teaching

Helping Teachers Inspire Learners

Best Tips for Teaching Early Writing

From the moment a child first grips a crayon and scribbles on a piece of paper, the journey of early writing development begins. This exciting and pivotal phase lays the foundation for a child’s future literacy skills and paves the way for their ability to communicate effectively. Teaching writing can be tricky but it doesn’t have to be if you look at the 5 stages of writing and the activities that you can do in your classroom to make this a fun and skill-based routine.

Stage 1: Pre-Writing Skills:

Before children can form letters and words, they engage in activities that develop the necessary motor skills for writing. These pre-writing activities include scribbling, drawing, and manipulating objects. Encouraging fine motor development through activities like coloring, playing with playdough, and using scissors helps strengthen the muscles required for writing. Building these foundational skills aids in hand-eye coordination and the ability to hold a pencil or pen with control.

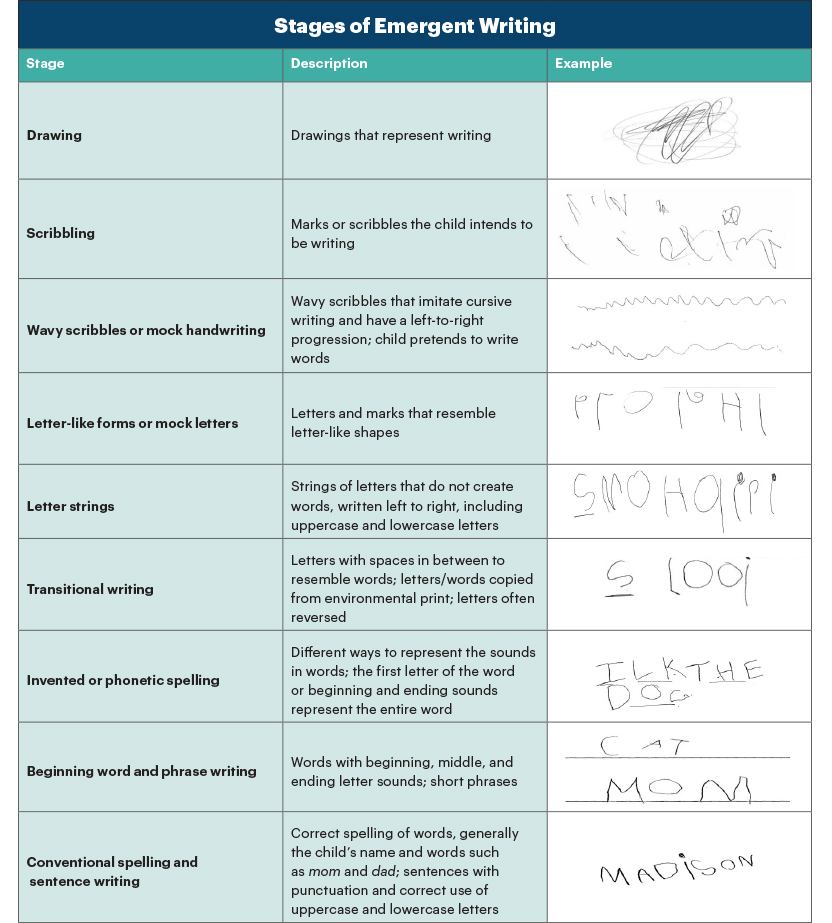

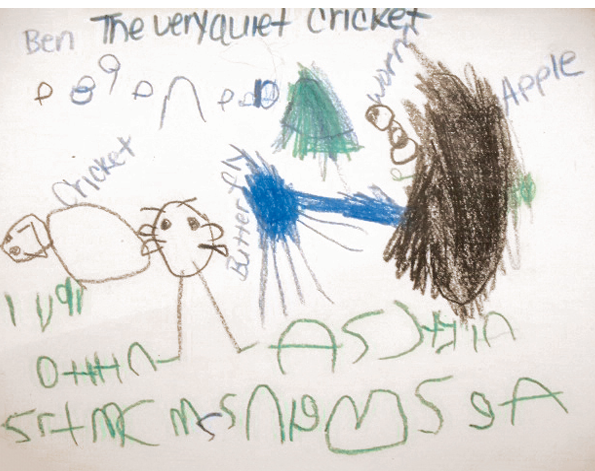

Stage 2: Emergent Writing

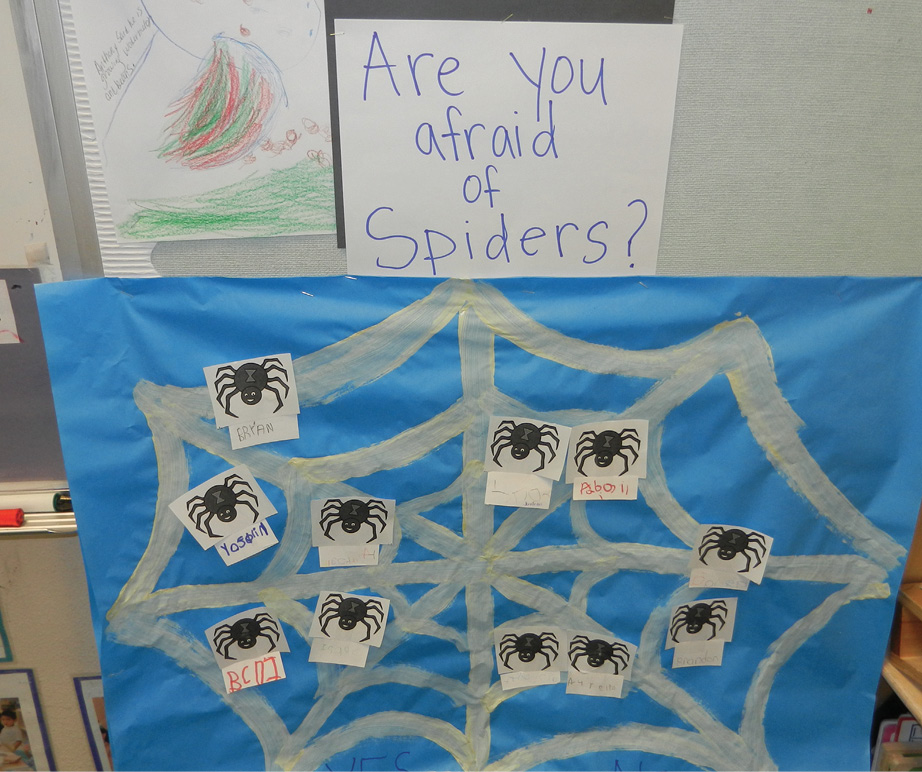

During the emergent writing stage, children start experimenting with letter-like forms, and strings of symbols, and imitating writing they have seen. They may scribble strings of shapes or letters and assign meaning to their marks. At this stage, it is essential to provide a print-rich environment. Try such things as labelling objects around the house and reading books together. Encouraging their efforts and engaging in conversations about their writing helps foster their confidence and reinforces the purpose of written language.

Stage 3: Letter Formation and Phonemic Awareness

As children begin to understand that letters represent specific sounds, they develop phonemic awareness. This awareness allows them to segment words into individual sounds and recognize the corresponding letters. Providing opportunities for letter recognition and formation through activities like tracing letters, playing with alphabet blocks, and singing letter songs can be valuable during this stage. Additionally, engaging in rhyming games, phonemic awareness exercises, and wordplay activities strengthens their understanding of the relationship between spoken and written language.

Stage 4: Early Spelling and Writing

At this stage, children start using invented or phonetic spelling. They may spell words as they hear them, using their developing knowledge of letter-sound relationships. Encouraging their attempts at writing and celebrating their progress helps build their confidence and motivation. Providing opportunities for dictation, where children express their thoughts and ideas while an adult writes them down, allows them to see the connection between spoken and written language. This stage is also an excellent time to introduce simple sentence structure and basic punctuation.

Stage 5: Developing Writing Fluency and Skills

As children gain more experience and practice, their writing skills become more refined. They begin to apply grammar rules, use punctuation correctly, and organize their ideas more coherently. Encouraging regular writing activities , such as journaling, storytelling, and creative writing exercises, nurtures their development and fosters a love for writing. Offering constructive feedback, suggesting new vocabulary words, and discussing various writing styles further enhance their growth.

Teaching Writing in the Classroom

Early writing development is an exciting and crucial phase in a child’s literacy journey. By supporting pre-writing skills, fostering emergent writing, nurturing letter formation and phonemic awareness, and encouraging early spelling and writing, we provide children with the tools they need to become confident writers. Remember, it is vital to create a positive and supportive environment where children feel safe to explore their creativity and express themselves through writing. By investing time and effort in this early stage, we help cultivate a lifelong love for the written word and set our children up for success in their academic and personal endeavors.

Are you reading this post as a 2nd or 3rd-grade teacher? Have a look at writing instruction for more fluent writers here .

Be sure to check out the early number sense skills post too.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

subscribe via email

EnglishPost.org

The Stages of the Writing Process

Writing is a form of communication that allows students to put their feelings and ideas on paper, to organize their knowledge and beliefs into convincing arguments, and to convey meaning through well-constructed text. In its most advanced form, written expression can be as vivid as a work of art.

Process writing as a classroom activity incorporates the four basic writing stages:

Let’s explore each one of them

Table of Contents

#1 Planning

#2 drafting, #3 revising.

Pre-writing is any type of activity that encourages learners to write. Before you start writing, consider the following things:

- Make your understand the type of essay you are about to write.

- Decide the topic you will write about and narrow it down.

- Consider your audience.

- List some sources that cover information about your topic.