This website may not work correctly because your browser is out of date. Please update your browser .

- UNICEF webinar: Comparative case studies

Resource link

What does a non-experimental evaluation look like? How can we evaluate interventions implemented across multiple contexts, where constructing a control group is not feasible?

Comparative case studies can be used to answer questions about causal attribution and contribution when it is not feasible or desirable to create a comparison group or control group. They are particularly useful for understanding and explaining how context influences the success of an intervention and how better to tailor the intervention to the specific context to achieve intended outcomes.

This webinar on comparative case studies was presented by Dr. Delwyn Goodrick, with a Q&A session between the presenter and audience at the end.

Can comparative case studies be used as a standalone tool or should they be complementary to regular evaluations?

How do you ensure that case studies are representative for the population and not anomalies? How do you make sure to avoid bias in selecting the case studies?

Do you think there is any scope for negotiating the realization of comparative case studies within an RCT? Or is it the case that a consultancy which proposed conducting an RCT won't be able to conduct a comparative case study?

Are comparative case studies about comparing results between countrie s or within the same communities?

The findings, interpretations and opinions expressed in the webinars are those of the presenters and do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The presenters are independent impact evaluation experts who were commissioned by UNICEF to prepare the webinars and use their own knowledge and judgement on key issues and to provide advice. The questions and comments reflected in the Q & A materials are based on those submitted by UNICEF staff as part of this capacity-building initiative. They do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of UNICEF.

The webinars were commissioned by UNICEF and UNICEF is entitled to all intellectual property and other proprietary rights which bear a direct relation to the contract under which this work was produced. The materials on this page are subject to a Creative Commons license CC BY-NC ( Attribution-NonCommercial ) and may be used and reproduced in line with the conditions of this licence.

Goodrick, D. (2015, August). Comparative Case Study . Impact evaluation webinars for UNICEF [Webinar]. Retrieved from: https://youtu.be/SgLSR55BxHg

Related pages

Project page.

- UNICEF Impact Evaluation Project

Methodological breif

This guide, written by Delwyn Goodrick for UNICEF, focuses on the use of comparative case studies in impact evaluation.

This is part of a series

- UNICEF Impact Evaluation series

- Overview of impact evaluation

- Overview: Strategies for causal attribution

- Overview: Data collection and analysis methods in impact evaluation

- Theory of change

- Evaluative criteria

- Evaluative reasoning

- Participatory approaches

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) video guide

- Quasi-experimental design and methods

- Comparative case studies

- Developing and selecting measures of child well-being

- Interviewing

- UNICEF webinar: Overview of impact evaluation

- UNICEF webinar: Overview of data collection and analysis methods in Impact Evaluation

- UNICEF webinar: Theory of change

- UNICEF webinar: Overview: strategies for causal inference

- UNICEF webinar: Participatory approaches in impact evaluation

- UNICEF webinar: Randomized controlled trials

- UNICEF Webinar: Quasi-experimental design and methods

'UNICEF webinar: Comparative case studies' is referenced in:

Back to top

© 2022 BetterEvaluation. All right reserved.

Content Search

Methodological briefs: impact evaluation no. 9, comparative case studies, attachments.

Delwyn Goodrick

Comparative case studies involve the analysis and synthesis of the similarities, differences and patterns across two or more cases that share a common focus or goal in a way that produces knowledge that is easier to generalize about causal questions – how and why particular programmes or policies work or fail to work. They may be selected as an appropriate impact evaluation design when it is not feasible to undertake an experimental design, and/or when there is a need to explain how the context influences the success of programme or policy initiatives. Comparative case studies usually utilize both qualitative and quantitative methods and are particularly useful for understanding how the context influences the success of an intervention and how better to tailor the intervention to the specific context to achieve the intended outcomes.

Related Content

Craf’d invests $3.5 million in data to transform crisis response and save lives, gender equality funding data is a mess. how do we fix it, climate change: the partnership with asian & pacific small island developing states, project 21: monitoring regional de protection (afrique centrale et de l'ouest) - p21 methodology note (version 2, april 2023).

- Open access

- Published: 29 September 2021

Closing the know-do gap for child health: UNICEF’s experiences from embedding implementation research in child health and nutrition programming

- Debra Jackson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3307-632X 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- A. S. M. Shahabuddin 1 ,

- Alyssa B. Sharkey 1 ,

- Karin Källander 1 ,

- Maria Muñiz 4 ,

- Remy Mwamba 1 ,

- Elevanie Nyankesha 1 ,

- Robert W. Scherpbier 1 ,

- Andreas Hasman 5 ,

- Yarlini Balarajan 5 ,

- Kerry Albright 6 ,

- Priscilla Idele 6 &

- Stefan Swartling Peterson 7 , 8 , 9

Implementation Science Communications volume 2 , Article number: 112 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

3689 Accesses

7 Citations

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

UNICEF operates in 190 countries and territories, where it advocates for the protection of children’s rights and helps meet children’s basic needs to reach their full potential. Embedded implementation research (IR) is an approach to health systems strengthening in which (a) generation and use of research is led by decision-makers and implementers; (b) local context, priorities, and system complexity are taken into account; and (c) research is an integrated and systematic part of decision-making and implementation. By addressing research questions of direct relevance to programs, embedded IR increases the likelihood of evidence-informed policies and programs, with the ultimate goal of improving child health and nutrition.

This paper presents UNICEF’s embedded IR approach, describes its application to challenges and lessons learned, and considers implications for future work.

From 2015, UNICEF has collaborated with global development partners (e.g. WHO, USAID), governments and research institutions to conduct embedded IR studies in over 25 high burden countries. These studies focused on a variety of programs, including immunization, prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, birth registration, nutrition, and newborn and child health services in emergency settings. The studies also used a variety of methods, including quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods.

UNICEF has found that this systematically embedding research in programs to identify implementation barriers can address concerns of implementers in country programs and support action to improve implementation. In addition, it can be used to test innovations, in particular applicability of approaches for introduction and scaling of programs across different contexts (e.g., geographic, political, physical environment, social, economic, etc.). UNICEF aims to generate evidence as to what implementation strategies will lead to more effective programs and better outcomes for children, accounting for local context and complexity, and as prioritized by local service providers. The adaptation of implementation research theory and practice within a large, multi-sectoral program has shown positive results in UNICEF-supported programs for children and taking them to scale.

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

Embedded implementation research (IR) is an approach to support health systems strengthening in which research is made integral to decision-making for program improvement. There are a variety of approaches and frameworks for embedded and implementation research described in the literature, but none specifically highlight use by a large multi-lateral organization as an approach globally to address program challenges and bottlenecks.

UNICEF’s mandate is to protect, promote, and fulfil children’s rights. The adaptation of implementation research theory and practice within UNICEF, a large, multi-sectoral organization, has shown positive results for improving programs for children. Since 2015, UNICEF has worked in collaboration with global development partners, governments and research partners to conduct embedded IR studies in over 25 high burden countries. This paper highlights the approach taken by a large multi-lateral organization to embed implementation research to improve policy and programming for children.

Introduction: need for actionable knowledge to improve programs for children

Significant progress in maternal and child health has been achieved over recent decades. Global under-five mortality dropped by more than half since 1990 [ 1 ]. Global maternal mortality fell 38% since 2000 [ 2 ]. Despite these achievements, unacceptable inequities in intervention coverage and child mortality remain, both among and within countries. Attention is needed to improve the quality of health and nutrition services and address systems challenges. Also, the contexts in which children live are changing [ 3 , 4 ]. In 2030, children will live in a world that is more urban, mobile, interconnected, and with an aging population. Income growth will shift some children into wealthier, but not necessarily healthier environments. Fragility is also expected to persist in countries struggling with extreme poverty, conflict, and weak governance. Emergencies, including public health emergencies and those stemming from environmental causes and climate change, are expected to increase in frequency [ 5 ].

Leroy et al. [ 6 ] noted that research on development of new interventions in child health and nutrition could potentially reduce under-five child mortality by 22%, whereas if existing proven interventions were fully implemented, these programs could reduce under-five mortality by 63%. They note the paradox that the majority of research funding focuses on new interventions (97%), rather than addressing implementation challenges (3%). This paradox demonstrates the urgent need to focus on implementation research (IR) to identify barriers and effective strategies to implementation of existing proven interventions. Evidence of the effect of long-term consistent investments in embedded IR on improved service coverage and efficient use of routine health system resources has recently emerged from Ghana [ 7 , 8 ] and Latin America and the Caribbean [ 9 ].

This paper presents UNICEF’s embedded IR approach, its application to maternal, child and nutrition programs, and present experiences to date; describes challenges and lessons learned; and considers implications for future work. The authors are all UNICEF staff who have developed and implemented the approach across the organization.

- Embedded implementation research

Implementation research is part of the broader field of implementation science. Rapport et al. define Implementation Science as “the scientific study of methods translating research findings into practical, useful outcomes,” but also note that the science is currently “contested and complex” [ 10 ]. Eccles and Mittman in the launch of the journal Implementation Science defined implementation research as “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services and care” [ 11 ], while Peters et al. [ 12 , 13 ] note that “The basic intent of implementation research is to understand not only what is and isn’t working, but how and why implementation is going right or wrong, and testing approaches to improve it.” This form of research addresses implementation bottlenecks, identifies optimal approaches for a particular setting, and promotes the uptake of research findings. Further, Ghaffar and colleagues [ 14 ] argued that IR should be ‘embedded’ in programming in partnership with policymakers and implementers, integrated in different settings and take into account context-specific factors to ensure relevance in policy priority-setting and decision-making. This view is further supported by Langlois and colleagues [ 9 ]. Churuca et al. note that “Embedded implementation research involves a knowledgeable researcher working with, or within, the team responsible for change, adoption, or take-up” and go on to describe four approaches of “embedded” research: dichotomized research-practice, collaborative linking-up, partially embedded, and deep immersion, describing the researcher-implementer relationship [ 15 ].

Varying definitions of operational, implementation and health systems research often cause confusion for both researchers and program managers. For example, the distinction between operations research and IR has been debated [ 16 ] as the two types of research are often similar in intent and scope. Definitions are often progressive without clear delineations, so many times operational, implementation, and health system research overlap [ 17 ]. Similar issues exist across other terms, such as formative research, process evaluation, and translational research.

UNICEF’s approach

Working in 190 countries and territories, UNICEF advocates for the protection of children’s rights, meets children’s basic needs, and expands their opportunities to reach their full potential. UNICEF’s comparative advantage is to work across sectors and across the life-cycle to protect these rights, focusing particularly on protecting the most disadvantaged and vulnerable children. UNICEF’s strategic plan 2018-20219 describes research as a “how” strategy to achieve targets [ 18 ]. UNICEF notes that in some situations while substantial evidence exists on what needs to be done, there are evidence gaps when it comes to identifying viable approaches for sustainable, full implementation and scale-up [ 19 ] of responses to improve programs for children.

As a large multi-lateral organization with a primary mandate of improving programs for children, UNICEF approached implementation research based on practical approaches and frameworks from the literature, with a focus on ‘how’ as defined in the strategic plan. UNICEF uses definitions outlined by Remme et al. [ 17 ], where operational research is a subset of IR, which is a subset of broader health systems research. In addition, UNICEF has primarily adapted taxonomy as described by Peters et al. and others [ 12 , 13 , 14 ] and has further defined embedded IR as “the integration of research within existing program implementation and policymaking to improve outcomes and overcome implementation bottlenecks,” and primarily uses either the” collaborative linking-up” or “partially-embedded” approaches for establishing the relationship of researcher and implementer as defined by Churucca et al. [ 15 ] UNICEF is adapting these innovative approaches for health systems strengthening in which research is made integral to decision-making. It includes (a) positioning research within existing programs and systems, building a new evidence ecosystem, and drawing siloed sectors together; (b) meaningful engagement and leadership roles for decision-makers and implementers within the research team; and (c) when possible, aligning research activities with program implementation cycles. Embedding increases the likelihood of evidence-informed policies and programs. Embedding IR into the policymaking and systems strengthening process amplifies ownership of evidence, recognizes decisions are not made on evidence alone, and also takes societal context and values into account.

Peters et al. note that research on innovations encompasses basic science through translation to sustainable implementation of new or existing evidence-based programs [ 12 ]. IR in UNICEF focuses on the latter stages of this continuum, i.e., issues ranging from how a program works in real-world settings to systems integration and scale-up, including decision-making, policy development, and creating an enabling environment for implementation.

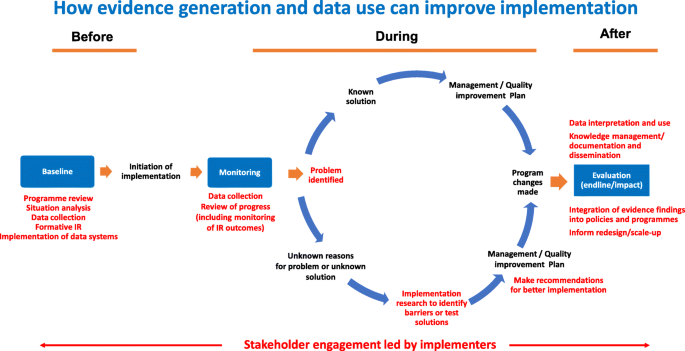

IR to support UNICEF programs is generally located within monitoring, evaluation, and knowledge translation or learning, as a basis for program innovation, systems strengthening and implementation. IR does not take the place of routine data collection, monitoring and evaluation, but is a complement to it. Figure 1 provides a conceptual model for how IR fits into the overall evidence and learning cycle for program management. Implementation research can also be associated quality improvement programming as part of learning and evaluation [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. UNICEF uses IR at various stages of program implementation, including formative and initial implementation stages and throughout the program cycle. We see IR as particularly useful for understanding challenges or bottlenecks which might be found while monitoring implementation of the program. This is a practical applied adaptation of IR suited for the needs of UNICEF. Recognizing that implementation science and implementation research has a variety of approaches and methods [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ], UNICEF sought to apply IR within our program support cycles in collaboration with governments and implementing partners. While the broader field of implementation science is critical, we needed to adapt the approach to fit the targeted and very focused needs of our country programs.

Where implementation research fits in program knowledge and learning cycle

Embedded implementation research at UNICEF: experiences 2015–2019

UNICEF, in partnership with the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research (The Alliance) and the Special Program for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR), has adapted an embedded IR approach for systems strengthening for country-based programs for children. As part of the UNICEF Health Systems Strengthening Approach [ 23 ], the research seeks to catalyze a shift in the way evidence is generated and used within countries to inform policy and decision-making. By bringing together (a) in-country decision-makers at national, sub-national, and local levels; (b) country-based researchers; and (c) global development partners, it puts local decision-makers and implementers in the driving seat in the research process, while identifying clear roles for different stakeholders.

The UNICEF approach aims to enhance ownership of the research among local implementers, similar to the co-production and collaborative approach to health systems research recently highlighted by Redman et al. on behalf of the “Co-production of Knowledge Collection Steering Committee” [ 24 ]. Although it may influence local or higher-level policy, it is primarily designed to prioritize research on questions of local relevance, build capacity to conduct local IR to generate feasible recommendations in “real-time” and underwrite policy and system strengthening. IR can also be considered during program initiation to answer questions on the acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of alternative delivery strategies, as well as blending with evaluation, using “effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs” [ 12 , 25 ], to address program effectiveness.

UNICEF works with both global and local partners to identify priorities on implementation barriers needing resolution through systematic and inclusive IR processes. Programs, through IR, can learn why implementation barriers and contextual variances mean that interventions work well in one context, but not in another. In addition, it can be used to test new approaches or innovations from pilot through scale-up across different contexts (e.g., geographic, political, physical environment, social, economic). Implementation research can also document failures, where an intervention success could not be replicated given local context, which is equally valuable to prevent wastage of funds before investing in scale-up.

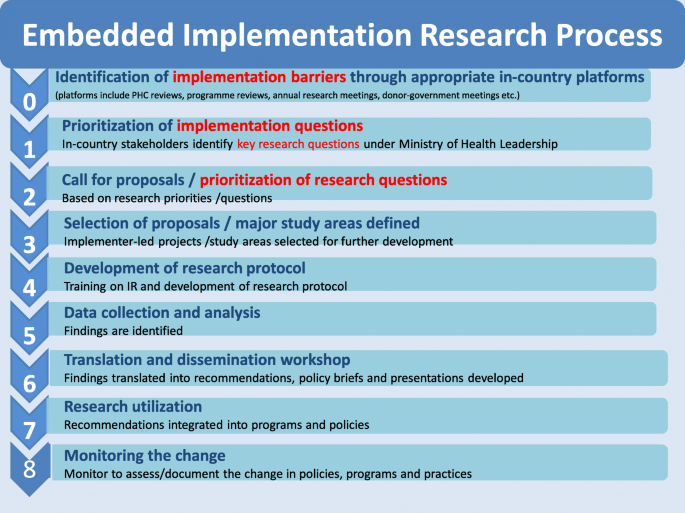

UNICEF’s embedded IR approach generally starts with sensitization of national stakeholders including Ministry of Health and policymakers to what IR is and what the potential benefits are (Table 1 ). Implementation barriers, often previously identified through national, sub-national, or local program reviews, or monitoring and evaluation, are reviewed, summarized, and prioritized. In collaboration with national stakeholders and policymakers, implementation barriers are then transformed into priority research questions and potential related IR studies are identified. A research team comprising a partnership between national policy-makers, local decision-makers, and implementers (e.g. program managers, district managers, front-line health workers), and in-country researchers is convened. Through this process, UNICEF staff, in partnership with implementation researchers or research institutions (global or local), provide technical support and training to develop protocols, ensure ethical research standards are maintained, conduct studies, and support communication of results, recommendations, and use of the findings for policy and program changes. Figure 2 provides an example of the UNICEF embedded IR process.

UNICEF embedded implementation research process

Figure 3 shows countries where UNICEF has worked with partners to embed IR within existing programming activities. In collaboration with in-country researchers, policy-makers and program implementers, UNICEF has been supporting IR projects globally since 2015. The research has varied from formative early stages of programming, through initial implementation, to full implementation. Methodological approaches varied by study and included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods. Study questions have addressed a wide variety of multi-sectoral topics (e.g., immunization, child health days, birth registration, newborn and child health in humanitarian settings, prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV) and health system challenges (e.g., information systems, human resources, supply chain, demand for services, community engagement, integration).

Countries participating in UNICEF-supported embedded implementation research since 2015

Measuring embedded implementation research success

UNICEF’s selected measure of success for embedded IR is that the research findings are used for policy and/or program changes. This near-real-time use of findings is key. Dissemination and publication of the results alone does not count as “use,” and policy or program changes should be documented, no matter how small or local. Selected examples can be found in Table 2 Case studies. Informal feedback suggests that from two-thirds to three-quarters of the IR studies successfully resulted in a documented policy or program change. Reasons for lack of use of findings suggested were limited time and resources and lack of formal follow-up after the research.

In addition to monitoring program results, we have also documented government implementers’ and local research partners’ [ 26 ] experiences in the program. Results suggest positive responses to participation in the process. Table 3 cites two quotes from a project in Pakistan, one from before the IR and one after, which exemplify the common responses seen from participants, and in particular highlight the co-production of knowledge.

Funding embedded implementation research at UNICEF

To date, UNICEF-supported IR studies have been funded almost exclusively through projects, as part of the program monitoring or learning agenda. Studies are typically short-term and require limited funding. For example, five HIV-related IR studies in 2017 cost US$15–35,000 each for data collection and analysis and were completed within 5 months. Projects to date range from $10,000 to $70,000 (usually $20,000-$40,000) and 5 to 18 months (usually 12 months). This near real-time aspect of embedded IR is recognized as one of the advantages as research results can be available within planning cycles for decision making and program adaptation. While the research projects themselves generally require limited funding, building local capacity to run the studies, both for the implementers and local researchers, often requires additional resources beyond the actual research costs for training and technical assistance during the studies, consistent with building capacity of research co-production as discussed by Agyebong and colleagues [ 8 ].

Key challenges and considerations in developing UNICEF’s embedded IR approach

IR has been recognized as critical to strengthen health systems [ 14 , 27 , 28 ]. However, the concept of embedding research into real-world policy, practice, and implementation is somewhat new in the field of global children’s programming, and uptake of the approach has challenges. For example, we have found that in-country partners, including local and national-level government counterparts, and some donors, need to be convinced about the value of IR. By engaging stakeholders in this approach, we have seen a recognition of the use of IR for program planning and enthusiasm for continuation of the implementer-researcher partnerships and research co-production after completion of the initial IR project. Also, for IR to be truly country driven, donors and partners have to trust that countries can identify the most relevant implementation barriers, transforming them into questions to investigate. This will require adaptations for review of research proposals, which may be more undefined regarding objectives and methods, given that these will be defined as a first step of the research process. Greater emphasis on domestic resource mobilization for embedding IR into the decision-making process and into routine program funding is needed. This problem can be overcome by advocacy, showcasing the value IR brings, building the capacity of partners on IR, and engaging them early and throughout the research activities so as to address their stated priorities, gaps in knowledge, and improve policy and ownership. Weighing opportunity costs between investing in service delivery and/or implementation research requires continued focus, as turnover of leadership and staff can reverse gains made in many contexts.

Another challenge is that in some cases, our partner implementers and researchers have been overly ambitious or wanted to pursue larger scale research. However, our experiences show that time-limited, small-scale and relatively inexpensive IR studies can lead to important learnings that have translated into changes in policies or approaches. We saw that the IR brought these two communities closer together with the benefits of greater relevance of research to programming, introduction of new methods, and faster implementations of specific solutions. To build incentives for researchers to do IR, showing how their research led to policy and practice change and not just traditional peer reviewed publications could be valued by universities as a component for promotion or research funding. Recent programs that promote and fund partnerships for implementation and health systems research, such as those by the Australian and UK Medical Research Councils and the Doris Duke Foundation African Health Initiative, have been a welcome contribution to the funding landscape [ 29 , 30 ].

Assessment of research quality and how the results are contributing to the existing evidence base also needs to be addressed. Many IR studies while being used locally for in country program improvements may not be published in peer-review literature, but nevertheless could contribute to expanding the evidence base on implementation strategies. Therefore, publishing in on-line platforms, such as the TDR Gateway ( https://www.who.int/tdr/publications/tdr-gateway/en/ ) or similar sites, will allow for quality-assurance and rapid wider dissemination.

UNICEF has built on the work of The Alliance, TDR, and others, to adopt an innovative embedded IR approach to meet country program needs to assure the right to health and well-being “For Every Child.” Implementation research at UNICEF is now supported across several sectors and by the Office of Research, suggesting a sustainable future for the approach. In addition, program staff from more than 25 countries have received training on this approach and how to support it with their partners during program implementation. IR has also been added to the UNICEF-University of Melbourne-Nossal Institute Health Systems Research Massive Open Online Course ( https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/health-systems-strengthening ). We have also seen an expansion of global partners and universities supporting this research, such as the Implementation Research and Delivery Science Coalition ( https://www.harpnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Coalition-Statement.pdf ) and several TDR Postgraduate programs ( https://www.who.int/tdr/capacity/strengthening/postgraduate/en/ ) in Bangladesh, Zambia, and Ethiopia, have developed partnerships with local UNICEF country programs.

Embedding research into local systems and service delivery can address concerns of implementers and support selection of effective implementation strategies, taking into account local context and systems complexity to address implementation barriers. UNICEF embedded IR seeks to understand how to overcome these barriers within maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent programs—in and beyond the health sector. In addition, it can be used to test applicability of approaches in different contexts (e.g., geographic, political, physical environment, social, economic). Ultimately, the aim of these activities is to build embedded IR capacity and accelerate large-scale adoption, effective implementation, and dissemination of successful approaches that generate results for women and children.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). Levels and trends in child mortality: report 2019. New York: UNICEF; 2019. https://data.unicef.org/resources/levels-and-trends-in-child-mortality/ Accessed 23 Dec 2019

Google Scholar

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the UN Population Division. Trends in maternal mortality: 2000 to 2017. Geneva: WHO; 2019. https://data.unicef.org/resources/trends-maternal-mortality-2000-2017/ Accessed 23 Dec 2019

UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2019: children, food and nutrition. New York: UNICEF; 2019. https://data.unicef.org/resources/state-of-the-worlds-children-2019/ Accessed 23 Dec 2019

UNICEF. Strategy for Health 2016-2030. New York: UNICEF; 2016. https://www.unicef.org/media/58166/file Accessed 23 Dec 2019

Watts N, et al. Strengthening health resilience to climate change. Technical Briefing for the World Health Organization Conference on Health and Climate. Geneva: WHO; 2015. https://www.who.int/phe/climate/conference_briefing_1_healthresilience_27aug.pdf

Leroy JL, et al. Current priorities in health research funding and lack of impact on the number of child deaths per year. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(2):219–23. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.083287 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kanmiki EW, Akazili J, Bawah AA, Phillips JF, Awoonor-Williams JK, Asuming PO, et al. Cost of implementing a community based primary health care strengthening program: the case of the Ghana Essential Health Interventions Program in northern Ghana. PLOS One. 2019;14(2):e0211956. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211956 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ayebong I, et al. Strengthening capacities and resource allocation for co-production of health research in low and middle income countries. BMJ. 2021;372:n166. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n166 .

Article Google Scholar

Langlois EV, et al. Embedding implementation research to enhance health policy and systems: a multi-country analysis from ten settings in Latin America and the Caribbean. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17:85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0484-4 .

Rapport F, et al. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24:117–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12741 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to implementation science. Implement Sci. 2006;1(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-1 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Peters DH, Tran NT, Adam T. Implementation research in health: a practical guide. Geneva: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research WHO; 2013. ISBN9789241506212

Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, Agyepong IA, Tran N. Implementation research: what it is and how to do it. BMJ. 2013;347:f6753. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f6753 PMID: 24259324. https://www.bmj.com/content/347/bmj.f6753/article-info .

Ghaffar A, Langlois EV, Rasanathan K, Peterson S, Adedokun L, Tran NT. Strengthening health systems through embedded research. Bull World Health Org. 2017;95(2):87. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.189126 .

Churuca K, et al. The time has come: embedded implementation research for health care improvement. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019;25(3):373–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13100 .

Monks T. Operational research as implementation science: definitions, challenges and research priorities. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0444-0 .

Remme JHF, Adam T, Becerra-Posada F, D'Arcangues C, Devlin M, Gardner C, et al. Defining Research to Improve Health Systems. PLoS Med. 2010;7(11):e1001000. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001000 .

UNICEF. Strategic Plan 2018-2021: Executive Summary. New York: UNICEF; 2017. https://www.unicef.org/publications/index_102552.html

Côté-Boileau E, Denis JL, Callery B, Sabean M. The unpredictable journeys of spreading, sustaining and scaling healthcare innovations: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17:84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0482-6 .

Kao LS. Implementation science and quality improvement. In: Dimick J, Greenberg C, editors. Success in Academic Surgery: Health Services Research. Success in Academic Surgery. London: Springer; 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-4718-3_8 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Balasubramanian, et al. Learning evaluation: blending quality improvement and implementation research methods to study healthcare innovations. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0219-z .

Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice book by Ross C. Brownson, Graham A. Colditz, and Enola K. Proctor https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199751877.001.0001/acprof-9780199751877 . Accessed 14 Sept 2021.

UNICEF. The UNICEF Health Systems Strengthening Approach. New York: UNICEF; 2016. https://www.unicef.org/media/60296/file [Accessed 7 Oct 2020]

Redman, et al. On behalf of the Co-production of Knowledge Collection Steering Committee. Co-production of knowledge: the future. BMJ. 2021;372:n434. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n434 .

Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 .

UNICEF. GAVI IR Report Implementation Research for Immunization Summary Report of Global Activities supported by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance 2015–2018. New York: UNICEF; 2018. https://www.technet-21.org/media/com_resources/trl/4982/multi_upload/UNICEF%20Implementation%20Research%20for%20Immunisation%20Report%20to%20Gavi%20July%202018.pdf [Accessed 7 Oct 2020]

Khalid F. Implementation research: from silos to synergy – an emerging story from Pakistan. New York: UNICEF; 2017. https://www.unicef.org/pakistan/stories/implementation-research-silos-synergy-emerging-story-pakistan Accessed 23 Dec 2019

Alonge O, Rodriguez DC, Brandes N, et al. How is implementation research applied to advance health in low-income and middle-income countries? BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4:e001257.

Theobald S, Brandes N, Gyapong M, el-Saharty S, Proctor E, Diaz T, et al. Implementation research: new imperatives and opportunities in global health. Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2214–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32205-0 .

Pratt B, Hyder AA. Designing research funding schemes to promote global health equity: An exploration of current practice in health systems research. Dev World Bioeth. 2018;18(2):76–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12136 Epub 2016 Nov 23. PMID: 27878976. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27878976/ .

Carbone NB, Njala J, Jackson DJ, Eliya MT, Chilangwa C, Tseka J, et al. “I would love if there was a young woman to encourage us, to ease our anxiety which we would have if we were alone”: Adapting the Mothers2Mothers Mentor Mother Model for adolescent mothers living with HIV in Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(6):e0217693. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217693 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The development of the UNICEF embedded IR approach would not have been possible without our many partners. In particular the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research (The Alliance) and the Special Program for Research in Tropical Diseases (TDR), former UNICEF staff, including Theresa Diaz and Kumanan Rasanathan at the World Health Organization and Mickey Chopra at the World Bank, and our many funders who have supported embedded IR as part of their partnerships with UNICEF, including Gavi, GFF, USAID, SIDA, Global Affairs Canada, Wellcome Trust, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. We must also acknowledge our UNICEF regional and country offices as well as our country-based government, implementing and research partners who have taken on this approach with enthusiasm.

None specific to this article.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Implementation Research and Delivery Science Unit, Health Section, Programme Division, UNICEF, New York, New York, USA

Debra Jackson, A. S. M. Shahabuddin, Alyssa B. Sharkey, Karin Källander, Remy Mwamba, Elevanie Nyankesha & Robert W. Scherpbier

Takeda Chair in Global Child Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, UK

Debra Jackson

School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

Health Section, East and Southern Africa Regional Office, UNICEF, Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

Maria Muñiz

Nutrition Section, Programme Division, UNICEF, New York, New York, USA

Andreas Hasman & Yarlini Balarajan

Office of Research Innocenti, UNICEF, Florence, Florence, Italy

Kerry Albright & Priscilla Idele

Office of the Associate Director for Health, Programme Division, UNICEF, New York, New York, USA

Stefan Swartling Peterson

Uppsala University, Women’s and Children’s Health (IMCH) and Karolinska Institutet, Uppsala, Sweden

Makerere University School of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors discussed conceptualization of this manuscript, participated in the described studies as principal or co-investigators, and contributed to writing of the manuscript. DJ wrote the 1st draft. ABS and ASM wrote descriptions of studies and created graphics. MM, RM, EN, KK, RS, SS, KA, PI, YB, and AH all contributed to review and editing of manuscript. All authors have reviewed final version and approved submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Debra Jackson .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

All research discussed in this manuscript underwent ethical approval by local accredited ethical review committees in each country. There are no specific ethical considerations for this methodologic manuscript.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Jackson, D., Shahabuddin, A.S.M., Sharkey, A.B. et al. Closing the know-do gap for child health: UNICEF’s experiences from embedding implementation research in child health and nutrition programming. Implement Sci Commun 2 , 112 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00207-9

Download citation

Received : 22 November 2020

Accepted : 25 August 2021

Published : 29 September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00207-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Child health and well-being

Implementation Science Communications

ISSN: 2662-2211

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Sign up for our newsletter

- Evidence & Evaluation

- Evaluation guidance

- Impact evaluation with small cohorts

- Get started with small n evaluation

Comparative Case Study

Share content.

A comparative case study (CCS) is defined as ‘the systematic comparison of two or more data points (“cases”) obtained through use of the case study method’ (Kaarbo and Beasley 1999, p. 372). A case may be a participant, an intervention site, a programme or a policy. Case studies have a long history in the social sciences, yet for a long time, they were treated with scepticism (Harrison et al. 2017). The advent of grounded theory in the 1960s led to a revival in the use of case-based approaches. From the early 1980s, the increase in case study research in the field of political sciences led to the integration of formal, statistical and narrative methods, as well as the use of empirical case selection and causal inference (George and Bennett 2005), which contributed to its methodological advancement. Now, as Harrison and colleagues (2017) note, CCS:

“Has grown in sophistication and is viewed as a valid form of inquiry to explore a broad scope of complex issues, particularly when human behavior and social interactions are central to understanding topics of interest.”

It is claimed that CCS can be applied to detect causal attribution and contribution when the use of a comparison or control group is not feasible (or not preferred). Comparing cases enables evaluators to tackle causal inference through assessing regularity (patterns) and/or by excluding other plausible explanations. In practical terms, CCS involves proposing, analysing and synthesising patterns (similarities and differences) across cases that share common objectives.

What is involved?

Goodrick (2014) outlines the steps to be taken in undertaking CCS.

Key evaluation questions and the purpose of the evaluation: The evaluator should explicitly articulate the adequacy and purpose of using CCS (guided by the evaluation questions) and define the primary interests. Formulating key evaluation questions allows the selection of appropriate cases to be used in the analysis.

Propositions based on the Theory of Change: Theories and hypotheses that are to be explored should be derived from the Theory of Change (or, alternatively, from previous research around the initiative, existing policy or programme documentation).

Case selection: Advocates for CCS approaches claim an important distinction between case-oriented small n studies and (most typically large n) statistical/variable-focused approaches in terms of the process of selecting cases: in case-based methods, selection is iterative and cannot rely on convenience and accessibility. ‘Initial’ cases should be identified in advance, but case selection may continue as evidence is gathered. Various case-selection criteria can be identified depending on the analytic purpose (Vogt et al., 2011). These may include:

- Very similar cases

- Very different cases

- Typical or representative cases

- Extreme or unusual cases

- Deviant or unexpected cases

- Influential or emblematic cases

Identify how evidence will be collected, analysed and synthesised: CCS often applies mixed methods.

Test alternative explanations for outcomes: Following the identification of patterns and relationships, the evaluator may wish to test the established propositions in a follow-up exploratory phase. Approaches applied here may involve triangulation, selecting contradicting cases or using an analytical approach such as Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). Download a Comparative Case Study here Download a longer briefing on Comparative Case Studies here

Useful resources

A webinar shared by Better Evaluation with an overview of using CCS for evaluation.

A short overview describing how to apply CCS for evaluation:

Goodrick, D. (2014). Comparative Case Studies, Methodological Briefs: Impact Evaluation 9 , UNICEF Office of Research, Florence.

An extensively used book that provides a comprehensive critical examination of case-based methods:

Byrne, D. and Ragin, C. C. (2009). The Sage handbook of case-based methods . Sage Publications.

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

Comparative Case Studies: Methodological Briefs - Impact Evaluation No. 9

- Author & abstract

- 8 Citations

- Related works & more

Corrections

- Delwyn Goodrick

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Matern Child Nutr

- v.18(Suppl 3); 2022 May

Countries' experiences scaling up national breastfeeding, protection, promotion and support programmes: Comparative case studies analysis

Sonia hernández‐cordero.

1 Instituto de Investigaciones para el Desarrollo con Equidad (EQUIDE), Universidad Iberoamericana, México City Mexico

Rafael Pérez‐Escamilla

2 Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven Connecticut, USA

Paul Zambrano

3 Alive & Thrive Southeast Asia/FHI 360, Manila Philippines

Isabelle Michaud‐Létourneau

4 Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, School of Public Health, Université de Montréal, Montreal Quebec, Canada

Vania Lara‐Mejía

Bianca franco‐lares, associated data.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request after receiving collaborative approval from the coauthors.

Scaling up effective interventions, policies and programmes can improve breastfeeding (BF) outcomes. Furthermore, considerable interest exists in learning from relatively recent successful efforts that can inform further scaling up, with appropriate adaptations, across countries. The purpose of this four‐country case studies analysis was to examine why and how improvements in BF practices occurred across four contrasting countries; Burkina Faso, the Philippines, Mexico and the United States of America. Literature reviews and key informant interviews were conducted to document BF trends over time, in addition to why and how BF protection, promotion and support policies and programmes were implemented at a national level. A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted. The ‘Breastfeeding Gear Model’ and RE‐AIM (Reach; Effectiveness; Adoption; Implementation; and Maintenance) frameworks were used to understand and map the factors facilitating or hindering the scale up of the national programmes and corresponding improvements in BF practices. Each of the studied countries had different processes and timing to implement and scale up programmes to promote, protect and support breastfeeding. However, in all four countries, evidence‐based advocacy, multisectoral political will, financing, research and evaluation, and coordination were key to fostering an enabling environment for BF. Furthermore, in all countries, lack of adequate maternity protection and the aggressive marketing of the breast‐milk substitutes industry remains a strong source of negative feedback loops that are undermining investments in BF programmes. Country‐specific best practices included innovative legislative measures (Philippines), monitoring and evaluation systems (United States of America), engagement of civil society (Mexico) and behavior change communication BF promotion (Burkina Faso) initiatives. There is an urgent need to improve maternity protection and to strongly enforce the WHO Code of Marketing of Breast‐Milk Substitutes.

The purpose of these four‐country comparative case studies was to examine why and how improvements in breastfeeding (BF) practices occurred across four contrasting countries: Burkina Faso, the Philippines, Mexico and the United States of America. Advocacy, political will, evaluation, multisectoral coordination, monitoring and funding are key to the successful scaling up and impact of national BF programmes. There is an urgent need to improve maternity protection and regulation of the marketing of breast‐milk substitutes.

Key messages

- The effective scale up of national breastfeeding (BF) policies and programs has been identified as a global health priority.

- There is a need to systematically conduct and compare case studies to understand drivers for the successful dissemination and scale up of national breastfeeding policies and programmes.

- Implementation science frameworks were key to systematically identify key drivers for the scale up of BF protection, promotion, and support policies and programmes in Burkina Faso, Mexico, the Philippines and the United States.

- Advocacy, multisectoral political will, financing, monitoring and evaluation, and coordination were key for enabling the BF environments.

- In all countries, there was a strong need to improve maternity protection and to tighten regulation and enforcement of the WHO Code of Marketing of Breast‐Milk Substitutes.

1. INTRODUCTION

The contribution of breastfeeding (BF) to child survival, health and development, as well as maternal health and national development, has been well documented (Victora et al., 2016 ). Protecting, promoting and supporting BF is highly cost‐effective (United Nations Children's Fund [UNICEF] & World Health Organization [WHO], 2017 ; Walters et al., 2019 ). Hence, scaling up national BF policies and programmes effectively has been identified as a global health priority (Pérez‐Escamilla & Hall Moran, 2016 ). Unfortunately, only 48.6% of infants younger than 6 months are exclusively breastfed in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Neves et al., 2021 ).

There is evidence that optimal BF behaviors, including exclusive BF (EBF), can rapidly improve when countries implement effective programmes (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2012 ). The scaling up of BF programmes could prevent an estimated 823,000 child deaths and 20,000 breast cancer deaths every year (Rollins et al., 2016 ). Also, it could reduce morbidity (Sankar et al., 2015 ; Victora et al., 2016 ) and improve children's educational potential and, probably, their income as adults (Victora et al., 2015 ).

The 2019 edition of The State of the World's Children reported an average global increase in EBF from 35% in 2005 to 42% by 2017, with some countries showing greater increases (United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), 2019 ). These findings have been recently confirmed (Neves et al., 2021 ). However, despite this increase, most countries are still far from reaching the 2025 EBF target of World Health Assembly Resolution 65.6, which aims to increase the rate of EBF in the first 6 months up to at least 50% (WHO, 2012 ). Therefore, there is an urgent need to better understand how successful scaling up efforts in countries has happened, in spite of having contrasting political, economic, social, cultural and health care systems contexts. Comparative case studies that are systematically conducted and analyzed are needed to generate this crucial evidence for informing the successful global dissemination, scale up, and maintenanc of effective national BF programmes. The objective of these case studies was to identify key facilitators and barriers for BF scale up at the national level across four countries with contrasting contexts, but where the rate of EBF improvement has been substantial during the past decade.

We developed and followed a systematic methodology in the development of this comparative four‐country case study, as outlined in the following section.

2.1. Country selection

The inclusion criteria for country selection were (i) located in one of the following regions of the world: Asia, North America, Latin America or Sub‐Saharan Africa, and (ii) having positive EBF trends over the last decade. Among all countries that met the criteria mentioned above, those with the highest rate of change in EBF were identified (Table 1 ). Subsequently, one country was selected, per region of the world covered, based on (iii) a close consensus among the first three authors; (iv) the willingness of key informants (KIs) to participate and (v) the availability of the following information: BF policy documents; evidence of exisiting programmes to promote, protect and support BF at the national or sub‐national level; peer‐reviewed publications describing EBF trends and BF programmes, or policies. As a result, the countries selected were Burkina Faso, the Philippines, Mexico and the United States of America.

EBF change rate among children under 6 months, by country

Abbreviation: EBF, exclusive breastfeeding.

2.2. Case studies development

The country's case studies were designed to present information regarding BF outcomes trends over time, and the implementation of policies, programmes or actions to promote, protect and support BF at the national or sub‐national level. We used a variety of approaches to access, document and synthesize the information, including: (1) a literature review to identify reports and peer‐reviewed articles describing the process of implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies, programmes and actions; and (2) KI interviews as needed to confirm and/or gather new information. Barriers and facilitators were identified using qualitative thematic analysis and then mapped to the Breastfeeding Gear Model (BFGM) (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2012 ) and RE‐AIM frameworks. RE‐AIM assesses (1) Reach: number of people impacted; (2) Effectiveness: impact; (3) Adoption: inclusion in the policy process; (4) Implementation: fidelity, adaptations and costs; and (5) Maintenance: extent to which it becomes part of the organization's standard practices (Jilcott et al., 2007 ).

2.2.1. Literature review

We conducted a literature review of the academic and grey literature addressing the diffusion, dissemination, uptake and sustainability of BF programmes, policies and interventions in the four countries included. English and Spanish documents published between January 2010 and March 2021 were included. The search was performed in five electronic databases, including EBSCO, PubMed Central, Web of Science, SCOPUS and ScienceDirect. The key terms used included: ‘((exclusive breastfeeding OR breastfeeding promotion OR breastfeeding programmes) AND (breastfeeding program OR breastfeeding protection OR nutrition policy) AND (Scale‐up OR Sustainability) AND (Mexico OR Burkina Faso OR Philippines OR US))’.

2.2.2. Key Informants interviews

We selected the key informants (KIs) based on their extensive knowledge of the BF environment in each country. We conducted in‐depth semistructured interviews remotely (Appendix S1 ) with individuals representing several sectors (society, academia, government authorities and international organizations) working on the protection, promotion and support of BF in each of the countries. The interview guide was developed similarly to previous case studies implemented by our team for the 2017 Lancet Early Childhood Development Series (Richter et al., 2017 ). Before the interview, a consent form (Appendix S2 ) was emailed to all interviewees for their written approval. The interviews were conducted through the Zoom platform by two authors (V. L.‐M. and S. H.‐C.), during the months of June to August 2021. Authorization to the interview was requested. The study was approved by the International Review Board of Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City.

2.2.3. Qualitative thematic analysis

The case studies were analyzed using thematic analysis and as stated before, mapped to two frameworks, the BFGM and RE‐AIM. The BFGM is a Health Care Complex Adaptive Systems framework that has been successfully tested in eight countries across five world regions to identify or strengthen policies needed to enable the BF environments (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2012 ). We used the RE‐AIM implementation framework to identify the drivers for improvements in BF practices in each country. The RE‐AIM framework has been successfully used by our team in other recent case studies analyses of evidence‐based obesity policies and programmes (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2021 ). The BFGM allowed for these findings to be integrated into a pragmatic dynamic systems model.

2.3. Data analysis

Data were extracted from the articles and reports identified through the literature review using a structured extraction form with the following information fields: (i) study design; (ii) population and intervention or program characteristics; (iii) key impact outcomes; and (iv) program or intervention effectiveness. To understand the policy and program implementation features in each country, B. F.‐L. and V. L.‐M. extracted data using RE‐AIM (Jilcott et al., 2007 ). The extraction was performed by country and type of intervention. KIs provided needed information that was not available from the literature review.

KI interviews were transcribed verbatim with an online program ( Happyscribe ). Coauthors V. L.‐M. and B. F.‐L. checked the transcripts for accuracy before importing them into Deedose (version 9.0.17). The codes were based on the BFGM components or ‘gears': (i) advocacy; (ii) political will; (iii) legislation; (iv) funding and resources; (v) training and programmes implementation; (vi) behavior change communication campaigns; (vii) research and evaluation; and (viii) coordination (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2012 ). Coding was carried out by V. L.‐M. and B. F.‐L. in Dedoose (version 9.0.17) using the codebook developed for this study (Appendix S3 ). Finally, the four‐country case studies were first analyzed by country based on the RE‐AIM framework and the BFGM and then were compared across countries to identify common key facilitators and barriers based on an iterative consensus approach coordinated by S. H.‐C. and R. P.‐E.

3.1. Literature review

The academic literature searches provided an initial sample of 62 unique articles published in peer‐reviewed journals. The titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion leading to 29 articles that were fully reviewed to determine eligibility, and 25 were included for data extraction (Figure 1 ). The main reasons for exclusion were lack of information on policies, programmes, or interventions to promote BF and unavailability of the full text. Regarding the grey literature, four documents and official web pages from international organizations were found. A total of 12 articles were not detected through electronic searches but were identified and shared by KIs. Therefore, we retained a total of 41 sources of information for final data extraction.

PRISMA diagram for literature review of policies, programmes, or interventions implemented in the countries selected. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses.

3.2. Key Informants interviews

In all countries, high‐level KIs were identified in the organizations or institutions selected a priori for this study. The detailed descriptive characteristics of the KIs' are included in Appendix S4 . A total of 18 KIs were interviewed, with Government being the most represented sector (Table 2 ). The majority of the KIs were women (14 out of 18), with an average age of 48.6 years, and 4.7 years in their current employment. Interviews lasted 45 min, on average.

Key informants by sector, four‐country breastfeeding case studies

3.3. Four‐country case studies

The four‐country case studies are summarized below, highlighting similarities and differences between countries. The detailed findings of the study (Boxes 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 and corresponding Supporting Information Materials) and illustrative quotes from the KIs (Table 3 ) are provided in the following sections.

Burkina Faso case study

Mexico case study, philippines case study, united states case study.

Representative quotes from in‐depth interviews based on the Breatsfeeding Gear Model (BFGM) a

Abbreviation: BFGM, Breastfeeding Gear Model.

3.3.1. Case study #1: Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso is a low‐income country in West Africa with a population of approximately 20,903,000 people (The World Bank, 2020a ). According to The National Nutrition Survey, EBF increased by 26.1 percentage points: from 38.2% in 2012 to 64.3% in 2020 (Ministère de la santé, 2020 ). The Directorate of Nutrition (DN) has been central for the coordination of BF policies and programmes among the Ministry of Health itself and International and local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). The PTF Nutrition (Technical and Financial Partners), created in 2012, has been a key channel for close coordination between the DN and PTF, which has allowed nutrition to become a priority in the country, helping to mobilize funding and define policy objectives (Box 1 ).

In Burkina Faso, an initiative called ‘Stronger with Breast milk Only’ (SWBO) (SBWO, 2021 ) and a programme called GASPA (Groupes d'Apprentissage et de Suivi des Pratiques optimales d'Alimentation, for its acronym in French) have been key to foster an enabling environment for BF. SWBO is an initiative that includes an awareness campaign that promotes giving babies breast milk only, on‐demand and stopping the practice of giving water and other liquids and foods, from birth until the first 6 months of life. GASPA facilitates support groups for mothers and the target beneficiaries for this program are pregnant women, mothers with infants 0–6 months and mothers with infants 6–24 months. From the KIs' perspective, the above‐mentioned initiatives were successful as a result of a combination of several factors, such as the evidence collected earlier (formative research) and the identification of adaptations needed during implementation. The case of Burkina Faso highlights the importance of community mobilization across RE‐AIM dimensions: reach, effectiveness and adoption, implementation and maintenance (Appendix S5 ). Regarding legislation and policies, since 2004, pregnant women in Burkina Faso have been eligible for fully paid maternity leave for 14 weeks, which can be taken between 4 and 8 weeks before the expected date of childbirth. On the other hand, according to WHO (WHO, 2020a ), Burkina Faso is moderately aligned with the International Code of Marketing of Breast‐milk Substitutes (the Code), which was recently updated in the country (March 2021) via the national decree no. 93‐279/PRES/SASF/MICM on the marketing and practices related to breast‐milk substitutes (BMS) products. The decree aligns with the World Health Assembly 69.9 resolution: ‘Ending inappropriate promotion of foods for infants and young children’ to regulate the marketing of BMS or any kind of milk specifically marketed for feeding infants and young children up to 3 years of age (WHO, 2016 ). Over the last decade, infant and child feeding practices became a strong priority for the government (political will), which appears to be reflected in the support that the SWBO initiative has received from the previous and current Minister of Health who publicly expressed their commitment. Following the nutritional crisis in some countries of the Sahel region (Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali), many International NGOs came to provide support and, as a result, nutrition activities were strengthened to prevent malnutrition. Before 2007, there was no specific nutrition directorate, so all the nutrition activities were under the Family Health Directorate. International Organizations' advocacy was essential for consolidating the creation of the DN, housed in the Ministry of Health, which currently coordinates all activities related to infant health and nutrition, including BF.

The work of the DN appeared to be a catalyst for the implementation of different endeavours to support BF, such as the revision of maternity legislation, the development of mass communication strategies for behavioral change and the enactment of policies in favor of BF. The Burkina Faso government developed a National Infant and Young Child Feeding Scale Up Plan (2012–2025), in partnership with Alive and Thrive (A&T), UNICEF, among other international agencies and NGOs (Scaling Up Nutrition, 2021 ). This is a multilevel strategic plan aimed at improving infant and young child feeding practices across sectors and at all levels, from the health system to the community, to standardize health and nutrition messages (Programme delivery/Coordination). It includes training of traditional leaders and midwives and the creation of mother‐to‐mother support groups, through the GASPA described above.

Coordination also appears to have been carried out effectively by different actors at several levels. In the case of the SWBO initiative, in 2020, a tripartite alliance composed of the DN, A&T and UNICEF, organized a national launch of the SWBO‐related campaign and subsequently supported subnational launches in the various regions. It helped to achieve combining different program components at both the community and health services levels to raise awareness of the importance of EBF (SBWO, 2021 ). Considering the SWBO campaign—a mass campaign to foster behaviour change—the SWBO initiative fits well within the BFGM ‘promotion’ gear. It is worth mentioning that the support of international organizations has been key to sustainability through the financing of multiple actions.

Burkina Faso has been making substantial efforts to improve its EBF rate. However, some challenges or negative feedback loops were identified. Although BF is a priority for the government, it currently lacks a specific government budget for BF, representing a risk to the sustainability of currently implemented actions to protect, promote and support BF. With respect to the Code, in spite of the current revision of the legislation, it has not yet fully incorporated all provisions related to it, and there is still contact between the BMS industry with health professionals for event sponsorship. Likewise, with regard to maternity leave, it is still not aligned with the International Labour Organization (ILO) Recommendation No. 191 (ILO, 2000 ), which encourages member countries to extend maternity leave to at least 18 weeks (Box 1 ).

3.3.2. Case study #2: Mexico

Mexico is an upper‐middle‐income country, in Latin America and the Caribbean region, with a population of 127,792,000 people in 2020 (OECD, 2021 ). Over the past decade, Mexico has doubled its EBF rate, from 14.5% in 2012 to 28.6% by 2018 (González‐Castell, 2020 ; WHO, 2020b ).

Between 2006 and 2018 the government invested in national policies and programmes to promote, protect and support BF; those identified through the literature review and mentioned by KIs were included in this analysis (Appendix S5 ). Although the current administration that came into power in 2018 has not continued with these efforts, Mexico was included because it has strong documentation of EBF improvements and implementation of large‐scale BF programmes during the timeframe of interest for our study. The Integrated Strategy for Attention to Nutrition (EsIAN, for its acronym in Spanish) was a pilot program within Prospera's conditional cash transfer program that aimed to strengthen health and nutrition by addressing the nutritional transition in Mexico and improving the health and nutrition of beneficiaries, with a strong focus on the first 1000 days (Hernández‐Licona et al., 2019 ). The three components of the EsIAN strategy were: (i) nutrition supplementation for pregnant and lactating women (tablets with micronutrients) and children aged 6–59 months (micronutrient powders, fortified porridge and milk), (ii) improved health care systems (specifically, equipment and quality of nutrition counseling) and (iii) behavior change communication and training, designed to promote infant feeding practices according to international recommendations. Moreover, the National Breastfeeding Strategy, implemented between 2014 and 2018, was a national policy that integrated different actions to promote, protect and support BF. Its specific aim was to increase the prevalence of girls and boys who are breastfed from birth through 2 years of age. It is noteworthy that the policy included strong intersectoral coordination including the health care system, the labor sector and communities. In addition, the strategy directly focused on the need to strengthen the dissemination and monitoring of compliance of the Code.

Regarding the legal status of the Code, Mexico is moderately aligned (WHO, 2020a ), but does not have a well defined and clear monitoring system nor sanctions. With regard to maternal employment, according to the ILO, female employees have been eligible for paid maternity leave of 12 weeks with full pay since 2009 (ILO, 2017 ). In the implementation research area, the Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly (BBF) Toolbox has been applied in Mexico three times since 2016 (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2022 ). Briefly, BBF is based on metrics to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the different components of the BFGM (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2012 ) to assess the country's readiness to scale up and make the corresponding evidence‐informed policy recommendations to enable the BF environment (González de Cosío et al., 2018 ). A result of the BBF multisectoral process since 2016 (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2012 ) is the strong advocacy for improving maternity leave benefits in Mexico for women employed in both the formal and informal economy (Vilar‐Compte et al., 2019 ).

Mexico's effort to improve infant feeding practices was initiated after the sharp decrease in BF practices shown by the National Health and Nutrition Survey in 2012 (Monitoring and evaluation) (Gutiérrez et al., 2012 ). This brought to the attention of key actors including civil society organizations the urgent need to act in favor of improving BF practices in the country. International organizations, Civil Society, Academia and Government allies started to identify strategies and opportunities to improve BF practices, a process that was strongly advanced by the BBF initiative as it has allowed them to work in a coordinated manner.

In the context of the sharp decline in BF practices in the country and evidence‐based BF advocacy, BF made its way into the government's agenda. In 2014, the Secretary of Health in Mexico promoted the reform of the ‘Ley General de Salud’ (Health General Law), which stipulates the mandatory set of actions that are needed to increasing EBF and the duration of any type of BF, including training of health professionals. As a result of this amendment, the 2013–2018 National Development Plan included the need to promote BF through actions to increase the duration of BF and EBF through BF promotion and support programmes and BF training of health personnel. It is in this context that the National Breastfeeding Strategy (ENLM, for its acronym in Spanish) was launched by the Secretary of Health and was implemented from 2014 to 2018 as the national breastfeeding policy (Secretaría de Salud, 2013 ). The ENLM had important limitations, such as not having an assigned budget, the lack of clarity on the proposed indicators for its evaluation and the lack of an implementation and impact evaluation strategy based on a proper study design. Nevertheless, KIs considered that the Strategy did advance the cause of BF in Mexico because it included actions and guidelines for health services nationwide to engage in promoting, protecting and supporting BF. In the same vein, various initiatives for amending laws and regulations emerged; for instance, the development of ‘Norm project 050’ ('Proyecto de norma 050') in 2018. Even though it has not yet been ratified, this norm is important because it sets out more specific criteria on actions that need to be taken for strengthening the protection, promotion and support of BF through 2 years of age, with a strong focus on supporting EBF during the first 6 months of life. This standard was proposed to be mandatory at the national level for health service personnel in the public, social and private sectors of the National Health System who were involved with maternal and child health care services, as well as for all persons, companies or institutions that had contact with mothers of infants and young children. BF women and those involved in the care, feeding and development of children (Diario Oficial de la Federación (DOF), 2018 ).

In Mexico, social mobilization, well coordinated work among various sectors and actors and evidence‐based advocacy represented a major step forward in the promotion, protection and support of BF. However, there are still major challenges to further improving BF practices in Mexico, especially due to the loss of political will as a result of the presidential transition (e.g., the government that came to power in 2018 has abandoned many of the BF policies and programmes that probably explain the doubling of EBF during the previous decade).

During the last decade, another important challenge identified was the lack of sufficient budget allocation to implement, monitor and evaluate strategies and initiatives to protect, promote and support BF, in accordance with the National Breastfeeding Strategy and other initiatives that were in place until recently. Finally, marketing of BMS is a common practice in Mexico, and very prominent via different communication channels including social media, in the context of a lack of enforcement of the WHO Code (Box 2 ).

3.3.3. Case study #3: Philippines