Discussion Tools

Case studies.

- Current Events

- Email Discussion

- Guest Faculty

- Journal Publications

- Question-based Lectures

- Role Playing

- Student Teaching

- appropriate selection of case(s) (topic, relevance, length, complexity)

- method of case presentation (verbal, printed, before or during discussion)

- format for case discussion (Email or Internet-based, small group, large group)

- leadership of case discussion (choice of discussion leader, roles and responsibilities for discussion leader)

- outcomes for case discussion (answers to specific questions, answers to general questions, written or verbal summaries)

Leading Case Discussions

- Reading the case aloud.

- Defining, and re-defining as needed, the questions to be answered.

- Encouraging discussion that is "on topic".

- Discouraging discussion that is "off topic".

- Keeping the pace of discussion appropriate to the time available.

- Eliciting contributions from all members of the discussion group.

- Summarizing both majority and minority opinions at the end of the discussion.

How should cases be analyzed?

- Who are the affected parties (individuals, institutions, a field, society) in this situation?

- What interest(s) (material, financial, ethical, other) does each party have in the situation? Which interests are in conflict?

- Were the actions taken by each of the affected parties acceptable (ethical, legal, moral, or common sense)? If not, are there circumstances under which those actions would have been acceptable? Who should impose what sanction(s)?

- What other courses of action are open to each of the affected parties? What is the likely outcome of each course of action?

- For each party involved, what course of action would you take, and why?

- What actions could have been taken to avoid the conflict?

Is there a right answer?

- Bebeau MJ with Pimple KD, Muskavitch KMT, Borden SL, Smith DH (1995): Moral Reasoning in Scientific Research: Cases for Teaching and Assessment. Indiana University. http://poynter.indiana.edu/mr/mr-main.shtml

- Elliott D, Stern JE (1997): Research Ethics - A Reader. University Press of New England, Hanover, NH.

- Cases and Scenarios, Online Ethics Center for Engineering and Research, National Academy of Engineering http://www.onlineethics.org/Resources/Cases.aspx

- Foran J (2002): Case Method Website: Teaching the Case Method: Materials for a New Pedagogy, University of California, Santa Barbara. http://www.soc.ucsb.edu/projects/casemethod

- Herreid CF: National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science, State University of New York at Buffalo. This comprehensive site offers methodology, a case study collection, case study teachers, workshops, and links to additional resources. http://ublib.buffalo.edu/libraries/projects/cases/case.html

- Korenman SG, Shipp AC (1994): Teaching the Responsible Conduct of Research through a Case Study Approach: A Handbook for Instructors. Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington, DC.

- Macrina FL (2005): Scientific Integrity: An Introductory Text with Cases. 3rd edition, American Society for Microbiology Press, Washington, DC.

- National Academy of Sciences (1995): On Being a Scientist: Responsible Conduct in Research. 2nd Edition. Publication from the Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy, National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine. National Academy Press, Washington DC. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=4917

- National Academy of Sciences (2009): On Being a Scientist: Responsible Conduct in Research. 3rd Edition. Publication from the Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy, National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine. National Academy Press, Washington DC. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12192

- Penslar RL, ed. (1995): Research Ethics: Cases and Materials. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN.

- Pimple KD (2002): Using Small Group Assignments in Teaching Research Ethics, The Poynter Center, Indiana University, Bloomington. http://poynter.indiana.edu/tre/kdp-groups.pdf

- Schrag B, ed. (1996): Research Ethics: Cases and Commentaries, Volumes 1-6, Association for Practical and Professional Ethics, Bloomington, Indiana. http://www.onlineethics.org/cms/15333.aspx

- Terms of Use

- Site Feedback

McCombs School of Business

- Español ( Spanish )

Videos Concepts Unwrapped View All 36 short illustrated videos explain behavioral ethics concepts and basic ethics principles. Concepts Unwrapped: Sports Edition View All 10 short videos introduce athletes to behavioral ethics concepts. Ethics Defined (Glossary) View All 58 animated videos - 1 to 2 minutes each - define key ethics terms and concepts. Ethics in Focus View All One-of-a-kind videos highlight the ethical aspects of current and historical subjects. Giving Voice To Values View All Eight short videos present the 7 principles of values-driven leadership from Gentile's Giving Voice to Values. In It To Win View All A documentary and six short videos reveal the behavioral ethics biases in super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff's story. Scandals Illustrated View All 30 videos - one minute each - introduce newsworthy scandals with ethical insights and case studies. Video Series

Case Studies UT Star Icon

Case Studies

More than 70 cases pair ethics concepts with real world situations. From journalism, performing arts, and scientific research to sports, law, and business, these case studies explore current and historic ethical dilemmas, their motivating biases, and their consequences. Each case includes discussion questions, related videos, and a bibliography.

A Million Little Pieces

James Frey’s popular memoir stirred controversy and media attention after it was revealed to contain numerous exaggerations and fabrications.

Abramoff: Lobbying Congress

Super-lobbyist Abramoff was caught in a scheme to lobby against his own clients. Was a corrupt individual or a corrupt system – or both – to blame?

Apple Suppliers & Labor Practices

Is tech company Apple, Inc. ethically obligated to oversee the questionable working conditions of other companies further down their supply chain?

Approaching the Presidency: Roosevelt & Taft

Some presidents view their responsibilities in strictly legal terms, others according to duty. Roosevelt and Taft took two extreme approaches.

Appropriating “Hope”

Fairey’s portrait of Barack Obama raised debate over the extent to which an artist can use and modify another’s artistic work, yet still call it one’s own.

Arctic Offshore Drilling

Competing groups frame the debate over oil drilling off Alaska’s coast in varying ways depending on their environmental and economic interests.

Banning Burkas: Freedom or Discrimination?

The French law banning women from wearing burkas in public sparked debate about discrimination and freedom of religion.

Birthing Vaccine Skepticism

Wakefield published an article riddled with inaccuracies and conflicts of interest that created significant vaccine hesitancy regarding the MMR vaccine.

Blurred Lines of Copyright

Marvin Gaye’s Estate won a lawsuit against Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams for the hit song “Blurred Lines,” which had a similar feel to one of his songs.

Bullfighting: Art or Not?

Bullfighting has been a prominent cultural and artistic event for centuries, but in recent decades it has faced increasing criticism for animal rights’ abuse.

Buying Green: Consumer Behavior

Do purchasing green products, such as organic foods and electric cars, give consumers the moral license to indulge in unethical behavior?

Cadavers in Car Safety Research

Engineers at Heidelberg University insist that the use of human cadavers in car safety research is ethical because their research can save lives.

Cardinals’ Computer Hacking

St. Louis Cardinals scouting director Chris Correa hacked into the Houston Astros’ webmail system, leading to legal repercussions and a lifetime ban from MLB.

Cheating: Atlanta’s School Scandal

Teachers and administrators at Parks Middle School adjust struggling students’ test scores in an effort to save their school from closure.

Cheating: Sign-Stealing in MLB

The Houston Astros’ sign-stealing scheme rocked the baseball world, leading to a game-changing MLB investigation and fallout.

Cheating: UNC’s Academic Fraud

UNC’s academic fraud scandal uncovered an 18-year scheme of unchecked coursework and fraudulent classes that enabled student-athletes to play sports.

Cheney v. U.S. District Court

A controversial case focuses on Justice Scalia’s personal friendship with Vice President Cheney and the possible conflict of interest it poses to the case.

Christina Fallin: “Appropriate Culturation?”

After Fallin posted a picture of herself wearing a Plain’s headdress on social media, uproar emerged over cultural appropriation and Fallin’s intentions.

Climate Change & the Paris Deal

While climate change poses many abstract problems, the actions (or inactions) of today’s populations will have tangible effects on future generations.

Cover-Up on Campus

While the Baylor University football team was winning on the field, university officials failed to take action when allegations of sexual assault by student athletes emerged.

Covering Female Athletes

Sports Illustrated stirs controversy when their cover photo of an Olympic skier seems to focus more on her physical appearance than her athletic abilities.

Covering Yourself? Journalists and the Bowl Championship

Can news outlets covering the Bowl Championship Series fairly report sports news if their own polls were used to create the news?

Cyber Harassment

After a student defames a middle school teacher on social media, the teacher confronts the student in class and posts a video of the confrontation online.

Defending Freedom of Tweets?

Running back Rashard Mendenhall receives backlash from fans after criticizing the celebration of the assassination of Osama Bin Laden in a tweet.

Dennis Kozlowski: Living Large

Dennis Kozlowski was an effective leader for Tyco in his first few years as CEO, but eventually faced criminal charges over his use of company assets.

Digital Downloads

File-sharing program Napster sparked debate over the legal and ethical dimensions of downloading unauthorized copies of copyrighted music.

Dr. V’s Magical Putter

Journalist Caleb Hannan outed Dr. V as a trans woman, sparking debate over the ethics of Hannan’s reporting, as well its role in Dr. V’s suicide.

East Germany’s Doping Machine

From 1968 to the late 1980s, East Germany (GDR) doped some 9,000 athletes to gain success in international athletic competitions despite being aware of the unfortunate side effects.

Ebola & American Intervention

Did the dispatch of U.S. military units to Liberia to aid in humanitarian relief during the Ebola epidemic help or hinder the process?

Edward Snowden: Traitor or Hero?

Was Edward Snowden’s release of confidential government documents ethically justifiable?

Ethical Pitfalls in Action

Why do good people do bad things? Behavioral ethics is the science of moral decision-making, which explores why and how people make the ethical (and unethical) decisions that they do.

Ethical Use of Home DNA Testing

The rising popularity of at-home DNA testing kits raises questions about privacy and consumer rights.

Flying the Confederate Flag

A heated debate ensues over whether or not the Confederate flag should be removed from the South Carolina State House grounds.

Freedom of Speech on Campus

In the wake of racially motivated offenses, student protests sparked debate over the roles of free speech, deliberation, and tolerance on campus.

Freedom vs. Duty in Clinical Social Work

What should social workers do when their personal values come in conflict with the clients they are meant to serve?

Full Disclosure: Manipulating Donors

When an intern witnesses a donor making a large gift to a non-profit organization under misleading circumstances, she struggles with what to do.

Gaming the System: The VA Scandal

The Veterans Administration’s incentives were meant to spur more efficient and productive healthcare, but not all administrators complied as intended.

German Police Battalion 101

During the Holocaust, ordinary Germans became willing killers even though they could have opted out from murdering their Jewish neighbors.

Head Injuries & American Football

Many studies have linked traumatic brain injuries and related conditions to American football, creating controversy around the safety of the sport.

Head Injuries & the NFL

American football is a rough and dangerous game and its impact on the players’ brain health has sparked a hotly contested debate.

Healthcare Obligations: Personal vs. Institutional

A medical doctor must make a difficult decision when informing patients of the effectiveness of flu shots while upholding institutional recommendations.

High Stakes Testing

In the wake of the No Child Left Behind Act, parents, teachers, and school administrators take different positions on how to assess student achievement.

In-FUR-mercials: Advertising & Adoption

When the Lied Animal Shelter faces a spike in animal intake, an advertising agency uses its moral imagination to increase pet adoptions.

Krogh & the Watergate Scandal

Egil Krogh was a young lawyer working for the Nixon Administration whose ethics faded from view when asked to play a part in the Watergate break-in.

Limbaugh on Drug Addiction

Radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh argued that drug abuse was a choice, not a disease. He later became addicted to painkillers.

U.S. Olympic swimmer Ryan Lochte’s “over-exaggeration” of an incident at the 2016 Rio Olympics led to very real consequences.

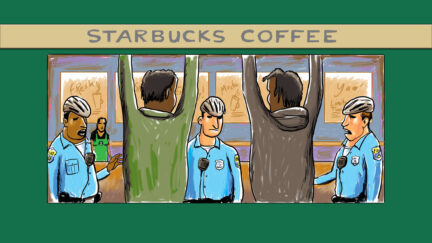

Meet Me at Starbucks

Two black men were arrested after an employee called the police on them, prompting Starbucks to implement “racial-bias” training across all its stores.

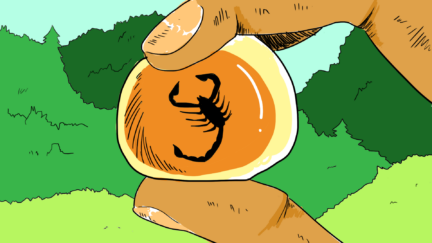

Myanmar Amber

Buying amber could potentially fund an ethnic civil war, but refraining allows collectors to acquire important specimens that could be used for research.

Negotiating Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy lawyer Gellene successfully represented a mining company during a major reorganization, but failed to disclose potential conflicts of interest.

Pao & Gender Bias

Ellen Pao stirred debate in the venture capital and tech industries when she filed a lawsuit against her employer on grounds of gender discrimination.

Pardoning Nixon

One month after Richard Nixon resigned from the presidency, Gerald Ford made the controversial decision to issue Nixon a full pardon.

Patient Autonomy & Informed Consent

Nursing staff and family members struggle with informed consent when taking care of a patient who has been deemed legally incompetent.

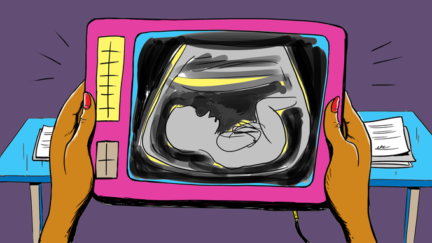

Prenatal Diagnosis & Parental Choice

Debate has emerged over the ethics of prenatal diagnosis and reproductive freedom in instances where testing has revealed genetic abnormalities.

Reporting on Robin Williams

After Robin Williams took his own life, news media covered the story in great detail, leading many to argue that such reporting violated the family’s privacy.

Responding to Child Migration

An influx of children migrants posed logistical and ethical dilemmas for U.S. authorities while intensifying ongoing debate about immigration.

Retracting Research: The Case of Chandok v. Klessig

A researcher makes the difficult decision to retract a published, peer-reviewed article after the original research results cannot be reproduced.

Sacking Social Media in College Sports

In the wake of questionable social media use by college athletes, the head coach at University of South Carolina bans his players from using Twitter.

Selling Enron

Following the deregulation of electricity markets in California, private energy company Enron profited greatly, but at a dire cost.

Snyder v. Phelps

Freedom of speech was put on trial in a case involving the Westboro Baptist Church and their protesting at the funeral of U.S. Marine Matthew Snyder.

Something Fishy at the Paralympics

Rampant cheating has plagued the Paralympics over the years, compromising the credibility and sportsmanship of Paralympian athletes.

Sports Blogs: The Wild West of Sports Journalism?

Deadspin pays an anonymous source for information related to NFL star Brett Favre, sparking debate over the ethics of “checkbook journalism.”

Stangl & the Holocaust

Franz Stangl was the most effective Nazi administrator in Poland, killing nearly one million Jews at Treblinka, but he claimed he was simply following orders.

Teaching Blackface: A Lesson on Stereotypes

A teacher was put on leave for showing a blackface video during a lesson on racial segregation, sparking discussion over how to teach about stereotypes.

The Astros’ Sign-Stealing Scandal

The Houston Astros rode a wave of success, culminating in a World Series win, but it all came crashing down when their sign-stealing scheme was revealed.

The Central Park Five

Despite the indisputable and overwhelming evidence of the innocence of the Central Park Five, some involved in the case refuse to believe it.

The CIA Leak

Legal and political fallout follows from the leak of classified information that led to the identification of CIA agent Valerie Plame.

The Collapse of Barings Bank

When faced with growing losses, investment banker Nick Leeson took big risks in an attempt to get out from under the losses. He lost.

The Costco Model

How can companies promote positive treatment of employees and benefit from leading with the best practices? Costco offers a model.

The FBI & Apple Security vs. Privacy

How can tech companies and government organizations strike a balance between maintaining national security and protecting user privacy?

The Miss Saigon Controversy

When a white actor was cast for the half-French, half-Vietnamese character in the Broadway production of Miss Saigon , debate ensued.

The Sandusky Scandal

Following the conviction of assistant coach Jerry Sandusky for sexual abuse, debate continues on how much university officials and head coach Joe Paterno knew of the crimes.

The Varsity Blues Scandal

A college admissions prep advisor told wealthy parents that while there were front doors into universities and back doors, he had created a side door that was worth exploring.

Providing radiation therapy to cancer patients, Therac-25 had malfunctions that resulted in 6 deaths. Who is accountable when technology causes harm?

Welfare Reform

The Welfare Reform Act changed how welfare operated, intensifying debate over the government’s role in supporting the poor through direct aid.

Wells Fargo and Moral Emotions

In a settlement with regulators, Wells Fargo Bank admitted that it had created as many as two million accounts for customers without their permission.

Stay Informed

Support our work.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Published on October 18, 2021 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from people.

The goals of human research often include understanding real-life phenomena, studying effective treatments, investigating behaviors, and improving lives in other ways. What you decide to research and how you conduct that research involve key ethical considerations.

These considerations work to

- protect the rights of research participants

- enhance research validity

- maintain scientific or academic integrity

Table of contents

Why do research ethics matter, getting ethical approval for your study, types of ethical issues, voluntary participation, informed consent, confidentiality, potential for harm, results communication, examples of ethical failures, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research ethics.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe for research subjects.

You’ll balance pursuing important research objectives with using ethical research methods and procedures. It’s always necessary to prevent permanent or excessive harm to participants, whether inadvertent or not.

Defying research ethics will also lower the credibility of your research because it’s hard for others to trust your data if your methods are morally questionable.

Even if a research idea is valuable to society, it doesn’t justify violating the human rights or dignity of your study participants.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Before you start any study involving data collection with people, you’ll submit your research proposal to an institutional review board (IRB) .

An IRB is a committee that checks whether your research aims and research design are ethically acceptable and follow your institution’s code of conduct. They check that your research materials and procedures are up to code.

If successful, you’ll receive IRB approval, and you can begin collecting data according to the approved procedures. If you want to make any changes to your procedures or materials, you’ll need to submit a modification application to the IRB for approval.

If unsuccessful, you may be asked to re-submit with modifications or your research proposal may receive a rejection. To get IRB approval, it’s important to explicitly note how you’ll tackle each of the ethical issues that may arise in your study.

There are several ethical issues you should always pay attention to in your research design, and these issues can overlap with each other.

You’ll usually outline ways you’ll deal with each issue in your research proposal if you plan to collect data from participants.

Voluntary participation means that all research subjects are free to choose to participate without any pressure or coercion.

All participants are able to withdraw from, or leave, the study at any point without feeling an obligation to continue. Your participants don’t need to provide a reason for leaving the study.

It’s important to make it clear to participants that there are no negative consequences or repercussions to their refusal to participate. After all, they’re taking the time to help you in the research process , so you should respect their decisions without trying to change their minds.

Voluntary participation is an ethical principle protected by international law and many scientific codes of conduct.

Take special care to ensure there’s no pressure on participants when you’re working with vulnerable groups of people who may find it hard to stop the study even when they want to.

Informed consent refers to a situation in which all potential participants receive and understand all the information they need to decide whether they want to participate. This includes information about the study’s benefits, risks, funding, and institutional approval.

You make sure to provide all potential participants with all the relevant information about

- what the study is about

- the risks and benefits of taking part

- how long the study will take

- your supervisor’s contact information and the institution’s approval number

Usually, you’ll provide participants with a text for them to read and ask them if they have any questions. If they agree to participate, they can sign or initial the consent form. Note that this may not be sufficient for informed consent when you work with particularly vulnerable groups of people.

If you’re collecting data from people with low literacy, make sure to verbally explain the consent form to them before they agree to participate.

For participants with very limited English proficiency, you should always translate the study materials or work with an interpreter so they have all the information in their first language.

In research with children, you’ll often need informed permission for their participation from their parents or guardians. Although children cannot give informed consent, it’s best to also ask for their assent (agreement) to participate, depending on their age and maturity level.

Anonymity means that you don’t know who the participants are and you can’t link any individual participant to their data.

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information—for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, and videos.

In many cases, it may be impossible to truly anonymize data collection . For example, data collected in person or by phone cannot be considered fully anonymous because some personal identifiers (demographic information or phone numbers) are impossible to hide.

You’ll also need to collect some identifying information if you give your participants the option to withdraw their data at a later stage.

Data pseudonymization is an alternative method where you replace identifying information about participants with pseudonymous, or fake, identifiers. The data can still be linked to participants but it’s harder to do so because you separate personal information from the study data.

Confidentiality means that you know who the participants are, but you remove all identifying information from your report.

All participants have a right to privacy, so you should protect their personal data for as long as you store or use it. Even when you can’t collect data anonymously, you should secure confidentiality whenever you can.

Some research designs aren’t conducive to confidentiality, but it’s important to make all attempts and inform participants of the risks involved.

As a researcher, you have to consider all possible sources of harm to participants. Harm can come in many different forms.

- Psychological harm: Sensitive questions or tasks may trigger negative emotions such as shame or anxiety.

- Social harm: Participation can involve social risks, public embarrassment, or stigma.

- Physical harm: Pain or injury can result from the study procedures.

- Legal harm: Reporting sensitive data could lead to legal risks or a breach of privacy.

It’s best to consider every possible source of harm in your study as well as concrete ways to mitigate them. Involve your supervisor to discuss steps for harm reduction.

Make sure to disclose all possible risks of harm to participants before the study to get informed consent. If there is a risk of harm, prepare to provide participants with resources or counseling or medical services if needed.

Some of these questions may bring up negative emotions, so you inform participants about the sensitive nature of the survey and assure them that their responses will be confidential.

The way you communicate your research results can sometimes involve ethical issues. Good science communication is honest, reliable, and credible. It’s best to make your results as transparent as possible.

Take steps to actively avoid plagiarism and research misconduct wherever possible.

Plagiarism means submitting others’ works as your own. Although it can be unintentional, copying someone else’s work without proper credit amounts to stealing. It’s an ethical problem in research communication because you may benefit by harming other researchers.

Self-plagiarism is when you republish or re-submit parts of your own papers or reports without properly citing your original work.

This is problematic because you may benefit from presenting your ideas as new and original even though they’ve already been published elsewhere in the past. You may also be infringing on your previous publisher’s copyright, violating an ethical code, or wasting time and resources by doing so.

In extreme cases of self-plagiarism, entire datasets or papers are sometimes duplicated. These are major ethical violations because they can skew research findings if taken as original data.

You notice that two published studies have similar characteristics even though they are from different years. Their sample sizes, locations, treatments, and results are highly similar, and the studies share one author in common.

Research misconduct

Research misconduct means making up or falsifying data, manipulating data analyses, or misrepresenting results in research reports. It’s a form of academic fraud.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement about data analyses.

Research misconduct is a serious ethical issue because it can undermine academic integrity and institutional credibility. It leads to a waste of funding and resources that could have been used for alternative research.

Later investigations revealed that they fabricated and manipulated their data to show a nonexistent link between vaccines and autism. Wakefield also neglected to disclose important conflicts of interest, and his medical license was taken away.

This fraudulent work sparked vaccine hesitancy among parents and caregivers. The rate of MMR vaccinations in children fell sharply, and measles outbreaks became more common due to a lack of herd immunity.

Research scandals with ethical failures are littered throughout history, but some took place not that long ago.

Some scientists in positions of power have historically mistreated or even abused research participants to investigate research problems at any cost. These participants were prisoners, under their care, or otherwise trusted them to treat them with dignity.

To demonstrate the importance of research ethics, we’ll briefly review two research studies that violated human rights in modern history.

These experiments were inhumane and resulted in trauma, permanent disabilities, or death in many cases.

After some Nazi doctors were put on trial for their crimes, the Nuremberg Code of research ethics for human experimentation was developed in 1947 to establish a new standard for human experimentation in medical research.

In reality, the actual goal was to study the effects of the disease when left untreated, and the researchers never informed participants about their diagnoses or the research aims.

Although participants experienced severe health problems, including blindness and other complications, the researchers only pretended to provide medical care.

When treatment became possible in 1943, 11 years after the study began, none of the participants were offered it, despite their health conditions and high risk of death.

Ethical failures like these resulted in severe harm to participants, wasted resources, and lower trust in science and scientists. This is why all research institutions have strict ethical guidelines for performing research.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. These principles include voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, potential for harm, and results communication.

Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from others .

These considerations protect the rights of research participants, enhance research validity , and maintain scientific integrity.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe.

Anonymity means you don’t know who the participants are, while confidentiality means you know who they are but remove identifying information from your research report. Both are important ethical considerations .

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information—for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, or videos.

You can keep data confidential by using aggregate information in your research report, so that you only refer to groups of participants rather than individuals.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement but a serious ethical failure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/research-ethics/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, data collection | definition, methods & examples, what is self-plagiarism | definition & how to avoid it, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Resources Home

- All Publications

- Digital Resources

- The BERA Podcast

- Research Intelligence

- BERA Journals

- BERA Blog Home

- About the blog

- Blog special issues

- Blog series

- Submission policy

- Opportunities Home

- Awards and Funding

- Communities Home

- Special Interest Groups

- Early Career Researcher Network

- Events Home

- BERA Conference 2024

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Past Conferences

- BERA Membership

Publication series

Research Ethics Case Studies

BERA’s Research Ethics Case Studies series, edited by Jodie Pennacchia, presents illustrative case studies designed to complement BERA’s Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research , fourth edition (2018) by giving concrete examples of how those guidelines can be applied during the research process.

For a full account of ethical best-practice as recommended by BERA we suggest that researchers refer to our Ethical Guidelines , which these case studies are intended to illustrate without themselves offering guidance or recommendations.

Annotations in the margins of each case study document in the series indicate where, among the numbered paragraphs of BERA’s Ethical Guidelines , readers can find our full advice on the issues raised (hyperlinks to the relevant passages are included).

So far BERA has published three entries in this series:

- Twitter, data collection & informed consent

- Researcher wellbeing & international fieldwork

- Anticipating the application & unintended consequences of practitioner research

Lecturer in Youth Work at Nottingham Trent University

Dr Jodie Pennacchia is a researcher in the policy-sociology of education and youth. She began her career working in learning support roles in mainstream and alternative schools, and has undertaken research across a range of educational contexts....

Content in this series

Research ethics case studies: 1. twitter, data collection & informed consent.

BERA’s Research Ethics Case Studies series begins by looking at the ethical issues that can arise when using social media as a means to recruit participants or gather data. To what extent are...

Resources for research 5 Sep 2019

BERA Research Ethics Case Studies: 3. Anticipating the application & unintended consequences of practitioner research

This third entry in BERA’s Research Ethics Case Studies series considers the unintended consequences of practitioner research – or, by extension, any research project that involves multiple...

Research Ethics Case Studies: 2. Researcher wellbeing & international fieldwork

Focussing on an early-career researcher embarking on her first academic role, this second entry in BERA’s Research Ethics Case Studies series considers the ethical issues that arise not only...

More related content

Blog post 20 Mar 2024

Publishing opportunity Open

Blog post 29 Feb 2024

Blog post 16 Feb 2024

News 19 Mar 2024

BERA in the news 14 Mar 2024

News 7 Mar 2024

News 5 Mar 2024

Site Search

- How to Search

- Advisory Group

- Editorial Board

- OEC Fellows

- History and Funding

- Using OEC Materials

- Collections

- Research Ethics Resources

- Ethics Projects

- Communities of Practice

- Get Involved

- Submit Content

- Open Access Membership

- Become a Partner

Using Case Studies in Teaching Research Ethics

An essay exploring how to effectively use case studies to teach research ethics.

It is widely believed that discussing case studies is the most effective method of teaching the responsible conduct of research (Kovac 1996; Macrina and Munro 1995), probably because discussing case studies is an effective way to get students involved in the issues. (I use the word “student” to cover all those who study, including faculty members and other professionals.)

Case studies are stories, 1 and narrative – the telling of stories – is a fundamental human tool for organizing, understanding, and explaining experience. Alasdair MacIntyre offers an amusing example of how one might make sense of a nonsensical event by embedding it into a story.

I am standing waiting for a bus and the young man standing next to me suddenly says, ‘The name of the common wild duck is Histrionicus histrionicus histrionicus.’ There is no problem as to the meaning of the sentence he uttered; the problem is, how to answer the question, what was he doing in uttering it? Suppose he just uttered such sentences at random intervals; this would be one possible form of madness. We would render his act of utterance intelligible if one of the following turned out to be true: He has mistaken me for someone who yesterday had approached him in the library and asked: ‘Do you by any chance know the Latin name of the common wild duck?’ Or he has just come from a session with his psychotherapist who has urged him to break down his shyness by talking to strangers. ‘But what shall I say?’ ‘Oh, anything at all.’ Or he is a Soviet spy waiting at a prearranged rendez-vous and uttering the ill-chosen code sentence which will identify him to his contact. In each case the act of utterance becomes intelligible by finding its place in a narrative. [MacIntyre 1981:195-196, italics in original] 2

Just as unintelligible actions invite us to put them into a story, stories invite us to interpret them. Stories imply causality, intention, and meaning; in the forms of parables, fables, and allegories, stories are favored vehicles for moral and religious instruction worldwide.

An in-depth discussion of a case is the closest approximation to actually confronting an ethical problem that can easily be set up in a classroom. Experience is the best teacher, but we can’t predict whether or when our students will face an actual ethical conflict in research, and we would not want to wish such an experience on them. Although a good case discussion is not the same as dealing with a real ethical problem, it can be an approximation of such an experience, just as watching a film about the decline and death of an aged friend can be a highly affecting approximation of the actual experience. Watching the film The Dresser can bring a person to real tears; discussing a case can bring a student to genuine ethical development.

The value of case study discussion can be illustrated with an anecdote. In the first year of the Teaching Research Ethics Workshop, we might have spent a bit too much time talking about using case studies and how to lead case study discussions. By Wednesday (the workshop began on a Sunday that year), one participant complained, saying something like, “Aren’t you going to talk about anything but cases? I’ve used them and students get bored with them.”

We spent less time on case studies thereafter, but I mention the incident because of an evaluation we did in the third year of the workshop. We hired an external evaluator to talk to past workshop participants about its impact on them. I asked our evaluator to talk to several specific participants, including the one who had complained about case studies. To my complete surprise, the report showed that this participant “identified mastery of the case study approach as having had the greatest direct impact” on his teaching. The other past participants interviewed made similar comments.

Like all teaching techniques, case study discussion can be done well or poorly, and I hope to provide some guidance to help you avoid the worst pitfalls. I will assume that you already know how to lead a discussion and limit my comments to considerations pertaining directly to using case studies in research ethics. My comments are rooted in what has worked for me with the assumption that most of it will work for you, too – but probably not all of it. Teaching is an art, and success depends a great deal on the skills and personality of the teacher.

Much of what follows might sound dogmatic, but that should be taken as a stylistic quirk. I could add all the hedges and exceptions of which I can think, but that would only muddy things. Use your own judgment and take the advice for what it’s worth. Also note that this is general advice; some cases are designed to be used in a particular way (see Bebeau et al. 1995).

Preparing to lead a case study discussion is much the same as preparing to teach anything – figure out what you want to accomplish, how much time you can spend on it, and the like.

In the classroom, start by laying out ground rules. In many settings this step does not have to be overt – if it is a group you have been meeting with already, and you have established a tone of respect and openness, there’s no need to go over this again. If the group has not established this kind of rapport, then it is important to make it clear that everyone’s opinion will be heard – and challenged – respectfully.

You might also want to offer your students some strategies and tactics before plunging into the discussion.

Strategies cover the broad direction for the discussion. For example, you can tell your students that you want them to:

- Decide which of two positions to defend – “Should Peterson copy the notes? Why or why not?”

- Solve a problem – “What should Peterson do?”

- Take a role – “What would you do if you were Peterson?” • Think about how the problem could have been avoided – “What went wrong here?”

Clearly these are not mutually exclusive, and there are probably other strategies you could use.

It is often also helpful to suggest some tactics . Sometimes students see a case study (or ethics) as an inchoate mass – or as too well integrated to analyze. It can be useful to give them some specific things to dig out of the case.

For example, in Moral Reasoning in Scientific Research: Cases for Teaching and Assessment , which I developed along with Mickey Bebeau, Karen Muskavitch, and several other colleagues (Bebeau et al. 1995), we suggest that students try to identify (a) the ethical issues and points of conflict, (b) the interested parties, (c) the likely consequences of the proposed course of action, and (d) the moral obligations of the protagonist.

Lucinda Peach (included in Penslar 1995) offers a different approach, suggesting the value of paying attention to six factors: facts; interpretations of the facts; consequences; obligations; rights; and virtues (or character). I have found it particularly helpful to point out the distinction between the facts presented in the case and the interpretations of facts that are sometimes made unconsciously.

When the time comes to start the actual discussion, I always distribute a copy of the case study to all students, and I often also display it using an overhead projector. If a case is at all complex or subtle, or has more than one or two characters, it is very difficult to take part in the discussion without having the case on hand for reference.

I usually ask one or more students to volunteer to read the case aloud . If there are several characters in the case, I often take the part of narrator and ask students to read the parts of the characters. Reading the case aloud ensures that everyone finishes at the same time; asking students to take part gets their voices heard early.

Then I give students a chance to ask any questions of factual clarification they might have. The answers might already be in the case, but they aren’t always. I don’t always answer all of these questions at this point, saying instead, “Let’s make sure we get to that when we discuss the case.” For example, if a student were to ask: “What kind of student is Peterson? Is she any good?” I would want to wait until the discussion period, when I would respond by asking, “What difference does it make?” (Not to imply that it doesn’t make a difference, but to see why the students think it does.)

I often then give students a few minutes to write some thoughts – perhaps to answer the strategic question, or identify the tactical elements I had already outlined. I usually don’t collect the papers; 3 the object here is to give students a chance to collect their thoughts and make a commitment, however tentative, to a few of them. Ideas that remain only half-formed in the mind often fly away when the discussion begins, but the written ideas are there for the students’ reference.

If the group isn’t too large, I find it very useful to go around the room and ask every student to make one short response to the case. When the strategy is to defend a position, I first ask them each to answer the first question – “Should Peterson copy the notes?” – yes or no. I tally their answers on the board. Then I go around again and ask each student to offer one reason for their answer. (If the responses are unbalanced – say 10 yes and 2 no – I give the students who said “no” the chance to state their case first.) In larger groups, I get a random sample of responses.

Then I plunge into the discussion, trying to be as quiet as I can and to get the students to talk as much as possible. My part is to keep things orderly, to clarify points in the case (including relevant rules and regulations), and to gently direct the discussion toward profitable paths. I usually write main points on the board.

Finally, the case should be brought to some kind of closure . Sometimes this means describing what I take to be the areas of agreement and disagreement and the relative weight of each (“Almost everyone agrees on X, but we’re still pretty divided on Y”). Sometimes it even includes a pronouncement: “It would be wrong for Peterson to copy the notes.” But I would generally qualify the pronouncement by describing some of Peterson’s other options.

Case study discussion can work even if you use it only once, but the more often a group discusses cases, the better. Using case studies is not the only technique for teaching responsible science, but it is, I think, one of the best.

Works Cited

Barnbaum, Deborah R., and Michael Byron. 2001. Research Ethics: Text and Readings . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bebeau, Muriel J., et al. 1995. Moral Reasoning in Scientific Research : Cases for Teaching and Assessment. Bloomington, IN.: Poynter Center. http://poynter.indiana.edu/mr-main.shtml

Elliott, Deni, and Judy E. Stern, eds. 1997. Research Ethics: A Reader . Hanover, CT: University Press of New England.

Harris, Charles E. Jr., Michael S. Pritchard, and Michael J. Rabins. 1995. Engineering Ethics: Concepts and Cases . Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

King, Nancy M. P., Gail E. Henderson, and Jane Stein, eds. 1999. Beyond Regulations: Ethics in Human Subjects Research . Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Kovac, Jeffrey. 1996. “Scientific ethics in chemical education.” Journal of Chemical Education 73(10): 926-928.

MacIntyre, Alasdair. 1981. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory . Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Macrina, Francis L. 2000. Scientific Integrity: An Introductory Text with Cases . 2nd ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press.

Macrina, Francis L. and Cindy L. Munro. 1995. “The case-study approach to teaching scientific integrity in nursing and the biomedical sciences.” Journal of Professional Nursing 11(1): 40- 44.

Orlans, F. Barbara, et al. 1998. The Human Use of Animals: Case Studies in Ethical Choice . New York: Oxford University Press. Penslar, Robin Levin. 1995. Research Ethics: Cases and Materials. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Seebauer, Edmund G., and Robert L. Barry. 2001. Fundamentals of Ethics for Scientists and Engineers . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schrag, Brian, ed. 1997-2002. Research Ethics: Cases and Commentaries . Six volumes. Bloomington, IN: Association for Practical and Professional Ethics.

Appendix: Types of case studies

I don’t know of any thorough typology of case studies, but it is clear that case studies take many forms. Here are some of the forms that I have come across. The list is not intended to be exhaustive, and the descriptive names are my own – they should not be construed as definitive or in common use.

Illustrative cases are perhaps the most common form. They are included in textbooks written specifically for instruction in the responsible conduct of research and are generally found at the end of each chapter to illustrate the chapter’s major points. For examples, see Barnbaum and Byron 2001; Elliott and Stern 1997; Harris, Pritchard, and Rabins 1995; Macrina 2000; and Seebauer and Barry 2001.

Historical case studies start with a particular controversy, event, or series of related events. Good examples can be found in The Human Use of Animals (Orlans et al. 1998). The first case, “Baboon-human liver transplants: The Pittsburgh case,” describes an operation performed in 1992 at the University of Pittsburgh to replace a dying man’s defective liver with a healthy liver from a baboon. The case itself is presented in two pages, followed by about a page of historical context. The bulk of the chapter, about eight pages, consists of commentary on the ethical issues raised by the case. (See also King et.al 1999.) Historical cases are good because they are real, not made up, and students cannot dismiss them by saying, “That would never happen.” On the other hand, though, some students will view historical cases as settled and over with; the very fact that they have been written up can seem to imply that the issues raised have all be solved.

Historical synopses are shorter, often focusing on a well-known event. Fundamentals of Ethics for Scientists and Engineers (Seebauer and Barry 2001), for example, includes sixteen “real-life cases,” generally one or two pages long with a few questions for discussion. The first three cases are titled “Destruction of the Spaceship Challenger,” “Toxic Waste at Love Canal,” and “Dow Corning Corp. and Breast Implants.”

Journalistic case studies are historical case studies written by journalists for mass consumption. A recent example, “The Stuttering Doctor’s ‘Monster Study’,” can be found in the New York Times Magazine (Reynolds 2003). It is the story of Wendell Johnson’s research in the late 1930’s that involved inducing stuttering in orphans. Journalistic accounts generally are written in a more literary, less academic style – they are often more passionate and viscerally engaging than case studies prepared by philosophers and ethicists.

Cases with commentary present the case study first and then follow it with one or more commentaries. The six-volume series Research Ethics: Cases and Commentaries (Schrag 1996- 2002) presents a short case (about two-four pages) followed by a commentary by the case’s author and a second commentary by another expert. (See also King et.al 1999.)

Dramatic cases are formatted like a script, which allows the characters’ voices to carry most of the story. I find them very good for conveying subtleties.

Trigger tapes are short videos intended to trigger discussion. Among the best available are the five videos in the series “Integrity in Scientific Research” (see http://www.aaas.org/spp/video/ ).

Finally, a series of casuistic cases presents several very short, related cases, each one in some way a variation or elaboration of one or more of the previous cases in the series. The first one or two cases are generally straightforward, presenting, for example, a clear-cut case of cheating and a clear-cut case of acceptable sharing of information. Later cases are less straightforward, pushing the boundaries that make the earlier cases clear-cut. Excellent examples can be found in Penslar 1995 (see, e.g., Chapters 5 and 6). This book also includes examples of many of the other kinds of case studies described here.

- 1 Some of the many forms case studies can take are described in the Appendix.

- 2 The young man is mistaken, by the way. Ducks belong to the family Anatidae, not Histrionicus.

- 3 I do collect the papers when I use Moral Reasoning in Scientific Research; it’s part of the method outlined in the booklet.

Portions of this paper are adapted from a presentation at the Planning Workshop for a Guide for Teaching Responsible Science, sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences, the National Science Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health, February 1997.

Copyright 2003, 2007, Kenneth D. Pimple, Ph.D. All rights reserved.

Permission is hereby granted to reproduce and distribute copies of this work for nonprofit educational purposes, provided that copies are distributed at or below cost, and that the author, source, and copyright notice are included on each copy. This permission is in addition to rights of reproduction granted under Sections 107, 108, and other provisions of the U.S. Copyright Act.

Also available at the TeachRCR.us site.

Related Resources

Submit Content to the OEC Donate

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Award No. 2055332. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Case Studies for Ethics in Academic Research in the Social Sciences

- Leisa Reinecke Flynn - The University of Southern Mississippi, USA

- Ronald E. Goldsmith - Florida State University, USA

- Description

Discuss and learn about the ethical choices faced in academic research in the social sciences

This book provides a basis for class discussion about the responsible conduct of social science research. These 16 brief research ethics cases describe situations in which ethical dilemmas arise and present students with the opportunity to think through the different implications for researchers. The cases emphasize different types of ethical dilemmas involving faculty, students, participants, and stakeholders. Included are the original cases, complete with learning objectives, teaching notes, and questions for discussion.

"…the cases presented are exceptionally well thought-out and presented at an appropriate level for graduate students." - T. Gregory Barrett , University of Arkansas

"This book fills a gap in the literature…The broad range of topics covers many issues of concern to all social scientists." - Sue Ann Taylor , American University

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

“The authors do a great job of providing very thought-provoking cases covering a broad array of ethical issues in a variety of social science research settings.”

“These thorough case studies provide an effective gateway for entering into class discussions that can reveal contemporary approaches and understandings of the ethical issues involved in the conduct and publication of social science research. I think the cases presented are exceptionally well thought-out and presented at an appropriate level for graduate students.”

“This book fills a gap in the literature. It is readable. It is a good teaching tool. The broad range of topics covers many issues of concern to all social scientists. Topics overlooked in most textbooks are included here (e.g., consulting, misdeeds, mentor/student relationships, data management, conflict of interests). The case study approach is an excellent way of adding the material to courses on ethics, research methods, or professional practice. The questions provide an opportunity for critical thinking and debate.”

KEY FEATURES:

- The first case book to focus exclusively on ethical dilemmas within the world of social science academia

- Presents brief original cases (including learning objectives, teaching notes, and discussion questions)

- Includes coverage of the protection of human subjects, mentor relationships, promotion and tenure, and peer review

Sample Materials & Chapters

ch 4 & 5

For instructors

Select a purchasing option.

This title is also available on SAGE Research Methods , the ultimate digital methods library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Microbiol Biol Educ

- v.15(2); 2014 Dec

Cautionary Tales: Ethics and Case Studies in Science

Ethical concerns are normally avoided in science classrooms in spite of the fact that many of our discoveries impinge directly on personal and societal values. We should not leave the ethical problems for another day, but deal with them using realistic case studies that challenge students at their ethical core. In this article we illustrate how case studies can be used to teach STEM students principles of ethics.

INTRODUCTION

Americans consider morality the most essential part of self ( 11 ).

This may be true of other cultures as well. All societies have elaborate rules of conduct that are often codified into law. Some of these imperatives seem hardwired. Human infants younger than a year and a half will look longer at visual displays showing violations of social rules ( 2 ). It is part of our primate heritage; individuals are punished if they stray far from acceptable behavior. Capuchin monkeys will reject a reward if they think they are being treated unfairly; they have a clear sense of right and wrong which depends on the social situation ( 3 ). Aesop would agree—he penned many a story where animals behaved badly and paid the penalty.

If morality and ethics are so central to our beings, what are our responsibilities as STEM educators to pass along the standards of society? And if we accept this challenge, what is the best way to instruct our youthful comrades in their quest for knowledge? I argue in this article that we should accept this obligation and that case study teaching is an ideal way to deliver the message.

Case-study teaching has a long and honorable lineage ( 4 ). In academic circles we find it used 100 years ago in Harvard Law School. The instructor would bring in a true criminal or civil case that had been adjudicated and conduct a class discussion with future lawyers, asking them to justify the rationale for the final decision—challenging them every step of the way. This provided students a real-world problem as part of their training for a real world ahead. The method was soon adopted by the Harvard Business School and various schools across the country, where it is now the standard. Medical schools have their own version of the method called Problem-Based Learning. Again the idea was to use real world problems to train physicians, but in this case students work in small groups to analyze patient problems and provide diagnoses. The idea of using similar strategies to teach basic sciences to undergraduates is largely due to the efforts of faculty at the University of Delaware and the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science, where there are hundreds of cases now published http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/ .

Research has shown that minorities and women undergraduates respond well to cases ( 5 , 8 ). Among this group, cases have been shown to increase students’ understanding of science by encouraging them to make connections between science concepts and situations they may encounter in their lives ( 7 ). In addition, the case method promotes the internalization of learning and the development of analytical and decision-making skills, as well as proficiency in oral communication and teamwork ( 6 ). The method, moreover, is a flexible teaching tool. Cases can take many different forms and be taught in many different ways, ranging from the classical discussion method used in business and law schools, to the arguably strongest approaches, Problem-Based Learning and the Interrupted Case Method, with their emphasis on small-group, cooperative learning strategies ( 4 ).

The method seems ideal for teaching ethics to STEM students. We have plenty of precedents to guide us. We have legal ethics, business ethics, medical ethics, bioethics, geoethics, environmental ethics, teaching ethics, research ethics, engineering ethics, and so on. And, of course, there are religious ethics, with each faith describing canons of behavior not to be breached. Some of them are commonly held community values, such as “thou shalt not steal, lie, or cheat.” Others are more specific, such as the research tenet, “thou should replicate experiments.” While some of these “rules” are so entrenched that they are tantamount to absolutes, others are more fragile and malleable; they are subject to the changing moral landscape. Policies about smoking in public places have rapidly shifted ( 12 ). Decrees against interracial marriage, once laws of the land, are now anachronisms, as are statues against same-sex marriage ( 1 , 10 ). Such shifts in the moral topography offer wonderful opportunities for case studies as they challenge students at their central core of beliefs. There are hundreds of these case studies now available for teachers in repositories such as the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu ), where you can find moral dilemmas depicted in cases on evolution, genetic engineering, nutrition, euthanasia, cloning, and organic farming.

Case studies can be used to show students acceptable standards of behavior within a given profession—the do’s and don’ts—and the disastrous consequences that can occur if the rules are not obeyed. We learn of breaches of research ethics such as fraud, plagiarism, and sloppy book-keeping that ruin careers. We come to know cautionary tales, like Dr. Andrew Wakefield, who misrepresented the medical histories of 12 patients and claimed that his research results showed that vaccinations caused autism. He was eventually discredited and Britain stripped him of his medical license. Unfortunately, this sensational allegation has resulted in thousands of people refusing to have their children vaccinated, with a subsequent striking rise in measles.

In the past, these stories were neglected in the STEM classroom. Questions of right or wrong belonged elsewhere—in the home, in a philosophy class, in a church or tabernacle. In the science classroom we learned how to make petroleum, shoot rockets, synthesize drugs, manipulate DNA, and clone animals, not whether we should do so. Then came the Second World War. The academic community ran squarely into two striking examples of the deep entanglement of science and ethics. Suddenly, there was a public debate about whether Truman’s decision to drop the atom bomb on Japan with the loss of millions of lives was ethical. The sensational trials of generals and scientists implicated in the atrocities at the Nazi concentration camps came to light during the Nuremberg Trials and patient bills of rights were drafted. Today our IRB committees and other ethical bodies monitor our experimental protocols involving research into issues of genetic engineering, stem cell research, three-parent embryos, etc. So my argument is that we should not ignore these disputes in the science classroom; this is where the technology is coming from—the STEM laboratories and the people in charge.

This is especially true as scientists have gained technological expertise; we see more clearly than ever how science and technological decisions can wreak havoc in our lives. Think about science in the courtroom, the public policy decisions on health and insurance, the intrusion of listening devices and the tracking of our e-mails and phone calls, the science of warfare and the use of chemical weapons and drones, the use of chemical fertilizers and organic farming, and possible designer babies. Very little that we humans do is not filled with moral or ethical conundrums. No more should we eschew these quandaries in our classrooms. When we discuss DNA genomes, we should not only speak of how the technology can be used to track potential criminals, but also how it can lead to social and personal dilemmas when we identify parentage, plot evolutionary lineages, discover genetically modified food, and detect mutations that might lead to lethal disease and the loss of insurance. How better to deal with such contentious matters than to use case studies? Case studies are stories with an educational message, and as such they are perfect vehicles to integrate science with societal and policy issues. They are ideal because of their interdisciplinary nature. They deal with real issues that students will face in the future. And people love stories.

RESOURCES FOR ETHICS CASES

There are several STEM case repositories in the world; arguably the largest is the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science, with over 500 case studies published over the past 25 years. Its greatest strength is in the fields of biology and health-related professions. Over 100 cases are catalogued as having ethical issues, ranging in suitability from middle school student classes to faculty seminars.

We seldom find pure instances of ethical transgressions, where issues of fraud, fabrication, or plagiarism are discussed. Rather, ethical issues are more apt to be a sidebar to the main thrust of a case concentrated on a health or environmental problem. And even in these cases, an individual may not be wrestling with problems involving societal standards. Instead, they grapple with whether it is prudent to make one decision versus another. It may be as simple as whether or not to have an operation or whether it is healthy to use drugs to lose weight.

Let me give you a flavor of the kinds of issues and cases that are available:

Personal dilemma

Often such cases involve medical issues, as we see in “A Right to Her Genes” ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/collection/detail.asp?case_id=316&id=316 ). In this true story, students examine the case of a woman, Michelle, with a family predisposition to cancer, who is considering genetic testing. The woman wishes to get some information to confirm this predisposition from a reluctant aunt so that she can better decide whether to remove her breasts and/or ovaries prophylactically. The aunt is illiterate and poor and had previously been estranged from the rest of the family. A genetic counselor is involved to help educate the aunt and hopefully obtain consent to get a DNA sample from her. Michelle must decide for herself what course of action she should take.

In “Spirituality and Health Care: A Request for Prayer” ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/collection/detail.asp?case_id=434&id=434 ), a fourth-year medical student making hospital rounds with an attending physician is asked by a family member of a patient to pray with her. The case allows medical students to explore issues related to patients’ religious beliefs as they think through how they might respond to different expectations and requests they may receive from patients and their families in their professional career.

Social ethics

These are cases where protagonists must decide how they will respond to evolving social standards. “SNPs and Snails and Puppy Dog Tails, and That’s What People Are Made Of” ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/collection/detail.asp?case_id=337&id=337 ) deals with questions of genome privacy. Students work together to research six lobbying groups’ views in this area and then present their insights before a mock meeting of a U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee voting on the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. In working through the case, students learn about single nucleotide polymorphisms, common molecular biology techniques, and current legislation governing genome privacy.

“A Case of Cheating?” ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/collection/detail.asp?case_id=399&id=399 ) involves two international students who are accused of cheating at the end of the semester, and the teacher must decide how to handle the accusation so that all students see that justice is done. The case raises cultural questions in the context of the use of peer evaluation and cooperative learning strategies.

Medical ethics

Patient rights are a common concern in medical cases, whether they are the central issue of the case or a sidebar to teaching students about a particular disease syndrome. It is the central theme of the infamous “Bad Blood” case involving black men in Tuskegee, Alabama, in the 1920s ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/collection/detail.asp?case_id=371&id=371 ). They had contracted syphilis, and public health officials studying the progress of the debilitating disease originally did not have an effective treatment. Twenty years later, the antibiotic penicillin was discovered, yet treatment was withheld to maintain the integrity of the study, whose purpose was to follow the progression of the disease. The study was immediately stopped when this transgression was made public.

Often there are competing concerns, as when a person is confronted with a decision where their personal morality may be at odds with the decrees of a society or institution. “The Plan: Ethics and Physician Assisted Suicide” ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/collection/detail.asp?case_id=436&id=436 ) is based on an article published in 1991 in the New England Journal of Medicine in which Dr. Timothy E. Quill described his care for a patient suffering from acute leukemia, including how he prescribed a lethal dose of barbiturates knowing that the woman intended to commit suicide. As a consequence of the article’s publication, a grand jury was convened to consider a charge of manslaughter against Dr. Quill. Students read the case and then, as part of a classroom-simulated trial, discuss physician-assisted suicide in terms of fundamental medical ethics principles.

Research ethics

Courses in experimental design are frequently part of psychology curricula. They seldom are part of the typical undergraduate programs in other STEM fields, although there is an excellent resource in the text Research Ethics ( 9 ). Apparently, students in STEM disciplines are supposed to absorb the proper canons of behavior by observation and osmosis.

“A Rush to Judgment” ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/collection/detail.asp?case_id=250&id=250 ) deals with a typical psychological experiment, where a faculty professor is inattentive to his student assistants, one of whom is misrepresenting the results of an experiment. Another student is confronted with a moral dilemma of whether to report this infraction at a potential cost to herself. Involved in the case is a consideration of proper research protocol when dealing with human participants: informed consent, freedom from harm, freedom from coercion, anonymity, and confidentiality. Students are referred to the American Psychological Association's Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct.

“How a Cancer Trial Ended in Betrayal” ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/collection/detail.asp?case_id=233&id=233 ) begins with a quote from a news item.

Birmingham, Alabama —After Bob Lange spent 8 weeks rubbing an experimental cream, BCX-34, from a prominent biotech company BioCryst on the fiery patches on his body, researchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham told him the drug was defeating the killer inside him. He felt grateful. “I believed it,” he recalls. “I actually thought I might be cured.” But it was a lie. The drug had no effect on Lange’s rare and potentially fatal skin cancer. And the two key people testing the drug knew it. Lange and 21 other patients were victims of fraud—a scheme made possible by the close tie between the university and the state’s most prominent biotech company. — The Baltimore Sun , June 24, 2001

The authors of this fascinating case state that the learning objectives are to learn the basics of scientific research in a clinical trial; to learn the principles of the scientific method; and to consider the ethical issues involved in clinical trials. Ethical potholes litter the road when universities travel with businesses, and millions of dollars and fame are at stake.

Socio-environmental ethics

Conflicting concerns are the norm when dealing with the environmental problems that beset our world. They not only involve scientific principles, but invariably policy and hurly burly politics as well.

“One Glass for Two People: A Case of Water Use Rights in the Eastern United States” ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/collection/detail.asp?case_id=603&id=603 ) focuses on the growing issue of water use. Approximately 1.3 million people in North and South Carolina depend on the Catawba-Wateree River for water and electricity. The river is also important for recreation and real estate development. To meet growing water demands, elected officials in Concord and Kannapolis, NC, petitioned their state government to approve an inter-basin transfer of 25 million gallons of water a day from the Catawba River. Other towns in North Carolina and South Carolina that are part of the Catawba-Wateree watershed fought this request for water transfer. For this exercise, students are divided into teams that take the role of different stakeholders trying to negotiate a settlement to this lawsuit. In the course of the debate, students address fundamental legal, ethical, and environmental questions about water use.

“Ecotourism: Who Benefits?” ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/collection/detail.asp?case_id=359&id=359 ) critically examines the costs and the benefits of visiting fragile, pristine, and relatively undisturbed natural areas. Although ecotourism has among its goals to provide funds for ecological conservation as well as economic benefit and empowerment to local communities, it can result in the exploitation of the natural resources (and communities) it seeks to protect. Students assess ecotourism in Costa Rica by considering the viewpoints of a displaced landowner, banana plantation worker, environmentalist, state official, U.S. trade representative, and national park employee.

Legal ethics