Making local economies prosperous and resilient: The case for a modern Economic Development Administration

- Full report

Subscribe to Infrastructure at Metro

Amy liu , amy liu vice president - metropolitan policy program, adeline m. and alfred i. johnson chair in urban and metropolitan policy @amy_liuw brad mcdearman , brad mcdearman nonresident senior fellow - brookings metro xavier de souza briggs , xavier de souza briggs senior fellow - brookings metro @xavbriggs mark muro , mark muro senior fellow - brookings metro @markmuro1 anthony f. pipa , anthony f. pipa senior fellow - global economy and development , center for sustainable development @anthonypipa adie tomer , and adie tomer senior fellow - brookings metro @adietomer jennifer s. vey jennifer s. vey nonresident senior fellow - brookings metro @jvey1.

June 27, 2022

- 31 min read

Congress has recently shown serious interest in reauthorizing the Economic Development Administration (EDA), a Department of Commerce agency last authorized in 2004. Congressional appropriators will also have their turn in adequately resourcing the agency, following the extraordinary demands of the pandemic and other impacts to local economies over the past two years.

The urgency and importance of congressional attention cannot be overstated. America’s global economic standing is under threat as digital disruption, the race for talent, and widening inequality both within and across regions challenge the nation’s competitiveness. Meanwhile, the U.S. economy regularly confronts recessions, extreme weather events, supply chain breakdowns, and other shocks that disproportionately impact some local economies and further test the nation’s collective ability to adapt and maintain economic resilience over the long run.

In response, the country needs to marshal the economic assets that cluster in specialized ways across the regions that make up the U.S. economy—be they leading industries, research universities, entrepreneurs, or workers. These assets are critical if the nation hopes to, for instance, reduce its reliance on imports and boost supply chain resilience with greater homegrown capabilities in computer chip, renewable energy, and medical equipment design and production. Furthermore, regions with strong innovation, economic diversification, and civic capacities are more able to adapt and bounce back from economic disruptions. For these reasons, the federal government has a vested interest in spurring place-based regional economic development. To do that, it has the EDA—the one federal agency whose sole charge is to promote economic revitalization in communities of any scale, rural or urban, across the country. In short, the EDA’s role is essential if the U.S. is to compete globally and prosper locally.

The concern is that the EDA is not properly resourced or equipped to meet its vital mission and nationwide mandate. The agency is tasked to do too much with too little—its chronically small annual budget, combined with unpredictable special appropriations, positions the agency as marginal when, in fact, the opposite is true. The EDA is the nation’s indispensable agency for supporting economic growth and resilience for communities large and small, as their leaders respond regularly to new opportunities and threats. But the policy and budget process does not yet treat it accordingly.

Congress can do its part. It can use reauthorization, now decades overdue, to elevate and modernize the EDA. It can give the agency the tools and resources to match its mandate, so it can successfully help communities and the nation adapt and rise to the immense challenges of the 21st century economy, including the range of economic disruptions today and those to come. EDA reauthorization deserves bipartisan attention and action.

To inform this process, this brief provides a rationale and framework for EDA reauthorization. It is organized in three sections. First, it expands on the case for a federal role in regional economic development. It then shows why only the legislative process can better equip the EDA to improve America’s capacity to innovate, compete, and expand economic opportunity for more people in more places. The brief closes with how: We recommend that the EDA become a $4 billion agency with a sharper purpose and set of roles and capabilities that match that mission. We believe this framework for EDA reauthorization and future appropriations would set the agency and its community partners up for success in today’s—and tomorrow’s—economy.

The authors of this brief have worked for decades with local, state, tribal, and national leaders on economic development planning, strategies, and execution. We are attuned to the demands placed on economic development actors across urban and rural communities, small and large regions, tribal nations, and downtowns and Main Streets. We are familiar with the complexity of implementation in areas such as innovation, talent development, finance, community economic development, placemaking, infrastructure, and regional and environmental planning. We came together to test a simple proposition: That despite our diverse backgrounds and experiences in economic development, we could agree on the importance of making the EDA a high-performing federal partner in spurring innovation and economic renewal for every region of the country and a policy framework for how to make that happen.

The case for a federal role in regional economic development

There are several reasons the federal government needs to proactively engage and support place-based economic development.

First, the path to national economic success will not come from a top-down, one-size-fits-all solution. That’s because the U.S. is not one monolithic economy, but a network of regional economies. Each is anchored by metropolitan areas and surrounding micropolitan and rural areas with their own unique industry specializations, labor and housing markets, and institutional capacities and relationships. Public, private, educational, and civic partners in each region often come together to help their businesses, industries, and workers adapt to new economic challenges or opportunities. Some regions benefit from a robust civic infrastructure; others suffer from weakened civic capacity reflecting years of economic disinvestment, siloed mandates, and talent flight. In short, any federal approach to bottom-up economic growth and renewal must unleash regions’ varied assets and governing capabilities.

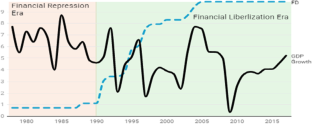

Second, while the economic geography of the U.S. has always been highly varied, what’s alarming is the extent to which it has become a winner-take-most economy from region to region. Since 2005, a handful of metropolitan areas have captured a predominant market share of the nation’s high-value innovation jobs, while hundreds of other communities lag behind. Indeed, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) finds that the average income gap between the most and least productive regions within wealthy nations grew an astonishing 60% over the past two decades.

This uneven economic landscape is a national problem, not simply a local one, as it concentrates the country’s competitive advantages in too few places while leaving large swaths of the U.S. underperforming their economic potential. There are twin costs to this extreme imbalance: Workers and industries in high-growth markets suffer from an unaffordable cost of living (especially high housing costs) and sharp inequality between communities within their regions, while other urban and rural regions struggle to generate income, wealth, and economic security. The result is that too few communities and regions are economically dynamic, prosperous, and inclusive.

A third reason for federal engagement is that in the wake of the pandemic, promising market forces are creating a valuable window to advance federal efforts to expand economic opportunity. While the aforementioned trends of regional divergence have largely continued since the onset of COVID-19, some cities and metro areas are beginning to grow tech jobs after years of job losses or stagnation. These places are buoyed by the movement of workers out of some of the largest metro areas and into smaller metro areas and rural towns, thanks to the flexibility of remote and hybrid work. Meanwhile, the future of work is reinventing downtowns, Main Streets, and other commercial corridors throughout regions. The geography of economic growth and opportunity is shifting, and rather than fuel more economic winners and losers from these dynamics, the federal government can use improved policies and investments to better enable leaders in every region, office, and commercial corridor to adapt and keep pace with the changing rules of the digital economy. In other words, the time is ripe to make wider and more resilient geographic prosperity a real possibility.

Lastly, the federal government is uniquely capable of making the scale of investments required to help local actors adapt to external forces—from natural disasters to technological shifts—and unleash the economic potential of places. Despite their best intentions, local interventions alone are inadequate to address economic shocks and the yawning gaps of growth and opportunity across the U.S. map. However, for now, the U.S. invests significantly less than other OECD member nations in helping its lagging regions adapt and develop. Our federal government also coordinates less consistently with subnational units of government—states, territories, tribes, and localities—on critical policymaking such as industry regulation, which can have far-reaching and disparate effects on different regional economies.

How changes in place-based economic development inform today’s federal support

To best understand the federal role, the federal government must first recognize how local economic development has changed and become even more resource- and capacity-intensive.

For decades, the primary focus of local economic development efforts has been to market their regions for business attraction, which was viewed as the most effective way to create jobs and grow a regional economy. Regions would provide the marketing and coordination, and states would provide incentives to secure the deal. Sometimes, the federal government would make public works or other infrastructure investments in regions to support the location and expansion of businesses—reinforcing the transactional, project-based nature of traditional economic development practice.

While incentives-driven business attraction remains one part of local economic development, numerous studies have found that it has not solved many of today’s local economic challenges. Rather, an increasing number of local leaders are going beyond measures of job growth to instead prioritize job quality, productivity, income growth, or other qualify-of-life measures, especially in smaller communities where job creation is not a realistic objective.

To achieve these broader aims, leaders are moving away from singularly focused transactions and toward more holistic, integrated approaches. This includes investments in strategic initiatives such as helping existing firms and industries grow, innovate, and develop diverse talent; creating an inclusive, homegrown entrepreneurship ecosystem; rebuilding Main Streets, downtowns, or other neighborhood corridors as flywheels for broader market-based growth and wealth creation; and centering talent and housing affordability in economic competitiveness and inclusion. Finally, both regional and community actors are investing in good governance by bringing local leaders and institutions together to solve problems and create the conditions in which workers, families, businesses, and other key partners are willing and able to stay and invest in the community.

As they do, local leaders are also increasingly mindful of ways to help vulnerable populations or protect the environment as sources of economic growth. For instance, local leaders are responding to the dislocating effects of disruptive technologies, especially to support Black, Latino or Hispanic, and other disadvantaged workers and entrepreneurs who are most vulnerable to automation and business closures in “high-risk” sectors such as food service, logistics, and retail. Regional leaders are aware of the costs of climate risk for businesses and communities and, conversely, the significant growth opportunities in building a low-carbon future.

Both large urban centers and rural areas are pursuing these broader approaches to economic development, despite the false urban-rural binary that permeates the political and policy discourse. In fact, rural leaders share similar challenges to their urban counterparts. For instance, rural communities are becoming more racially and economically diverse , while they grapple with educational quality, inadequate incomes for workers and their families, and challenges in health care access, cost, and outcomes. The extractive nature of many rural economies leaves too little wealth and economic decisionmaking to the communities themselves. Just like urban areas, rural towns have hidden assets and innovation ready to be leveraged but too often overlooked. And rural and urban regions are interdependent in ways that dated economic development paradigms and practices barely acknowledge, let alone build on.

That’s why economic development leaders from across the urban and rural continuum, such as in Indianapolis , Birmingham, Ala. , and Wytheville, Va. , have stepped up to create high-quality, entrepreneurial, and inclusive growth in their communities.

But this kind of inclusive economic development is hard work—and even pioneers in the field face many barriers to implementation . Local leaders typically lack the resources and organizational capacity to plan well, coordinate across actors, and respond to a patchwork of rural , tribal, and place-based programs alongside other state or philanthropic resources.

This reality prompted one of the authors of this brief to make the case for vigorous federal engagement to promote more centers of innovation and opportunity across the American landscape. Specifically, the report on growth centers from Brookings and the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation argues that absent robust federal action, few if any places (outside of the top U.S. metro areas) will be able to transform themselves into vibrant economies with self-sustaining innovation growth paths. The federal government is uniquely capable of investing at scale in targeted places to counter regional divergence and promote spillover benefits.

Another Brookings report makes the case that the most successful and promising cluster initiatives in the U.S. are industry-driven, university-fueled, and government-funded . In each of the cases in the report, significant government funding—from local, state, and federal sources—gave the initiatives early credibility and provided the scale required to have real impact. Without government investment, it is likely that none of the profiled initiatives, from Milwaukee’s water tech cluster to central New York’s unmanned aerial systems, would have even made it out of the starting gate.

Both reports reveal that public and private sector leaders in many U.S. regions have identified unique, high-potential opportunities, but also gaps in their local economies that are holding them back. They need adequate resources to grow and connect their economic and other assets in ways that can place them on a new economic trajectory.

The federal government has a critical and unique role in such place-based economic development. It can assess federal budgets, trade and regulatory proposals, and other policies for differential impacts on regions of the country based on their distinct economic realities, as the United Kingdom and other advanced economies do. In addition to the OECD analysis mentioned above, there is a compelling research base here in the U.S. to support such regional equity analyses in national policymaking. To cite one costly example, the U.S. could have approached airline industry deregulation differently if regional economic disparities and likely impacts had been considered rigorously and creatively. The federal government needs to build out and fully exercise this ability if it wants the U.S. to remain a world leader in innovation and become one in inclusive economic growth.

The EDA’s broad and under-resourced mandate

If place-based economic development is critical to our nation’s economic future, then the EDA is well positioned as the lead federal agency to fulfill that mandate. Though larger federal agencies provide grants, loans, and other supports for local development, the EDA is the agency tasked to: 1) work most directly with all types of regions across the country specifically on economic revitalization; and 2) bring rigorous economic analysis to help local regions make the most promising choices.

For these reasons, it is crucial that Congress reauthorize the EDA. More than that, Congress must use the process to elevate and modernize the agency. The dramatic shifts in the economy and economic development over the past several decades require the lead federal agency on economic development to be a meaningful partner to the regional entities that steward American competitiveness. And it should do so by reflecting the leading edge of practice in communities.

The EDA was established by the Public Works and Economic Development Act of 1965 to help industrial areas (urban), agricultural communities (rural), and mining towns deal with economic distress. For these reasons, the EDA’s most consistent and best-resourced mandate has been in public works projects and infrastructure development, as documented in a recently published overview of the EDA by the Urban Institute. That mandate reflects a classic—but now dated—understanding of the federal role in local economic development to promote large-scale, place-targeted capital investments in major public works, such as the Erie Canal and the many projects made possible through the Tennessee Valley Authority.

The EDA’s last reauthorization—in 2004—highlighted Congress’ understanding of the critical and evolving role of the federal government in place-based economic revitalization. The 2004 reforms recognized the need to expand the EDA’s mandate and mission to include promoting growth and competitiveness through better local economic planning; investments in economic innovation through university centers, new technologies, and broadband; brownfields remediation to prepare land for forward-looking, cluster-based development; assistance to respond to economic dislocation and adjustment triggered by growing global trade; and post-disaster assistance for economic recovery.

Unfortunately, that extensive mandate—meant to serve thousands of communities nationwide, on a fair and inclusive basis—has been supported with very modest congressional appropriations, averaging approximately $283 million annually since fiscal year 2011. To put that in perspective, the city of Alexandria, Va., home to 159,000 residents in 2020, approved an annual budget of $761.5 million that year. The EDA is forced to spread itself thin across its wide-ranging mandates and geographic remit, and it often lacks the funds to waive or reduce matching-fund requirements for smaller, poorer jurisdictions that most need help strengthening their economic and fiscal base.

The EDA’s budget is not only routinely inadequate—it is also unpredictable. For instance, in FY 2008, its budget more than doubled in absolute terms to reflect supplemental funding for Gulf Coast disaster recovery. In FY 2018, the agency was proposed for elimination due to arguments over government waste and redundancy. In stark contrast, in FY 2021, the agency received $1.5 billion through the CARES Act, followed by an additional $3 billion through the American Rescue Plan Act—10 times its typical annual appropriation over the past decade.

On the plus side, these one-time appropriations and supplemental programs have allowed the EDA to experiment with new economic development initiatives, such as the recent Build Back Better Regional Challenge grant program. But this seesaw has also left the agency with an impossible task of delivering an expansive mix of new and existing programs—from targeted public works projects in rural areas to broad regional innovation grants to economic adjustment assistance for coal communities—all on a miniscule and unpredictable annual budget.

In sum, the EDA enters reauthorization as an under-resourced agency. It is tasked to do too much with too little, employing a mix of new and outdated programs. It is time for Congress to reach the same awareness of needed change as it did in 2004 and reauthorize and modernize the EDA once again.

The proposal: A framework for modernizing the EDA

Reforming a federal agency through the legislative process is often hard, if not impossible, as competition between interest groups and agendas can produce a something-for-everyone patchwork and only incremental change. Fortunately, a group of national economic development groups and associations has unified to support EDA reauthorization. This EDA Stakeholder Coalition, which features diverse local membership representing all parts of the country, issued a statement for congressional leaders that includes nine shared priorities for the agency. There are many strong, tested programmatic ideas among the list that we reinforce below.

However, our proposal addresses two first-order questions: What specific roles and functions are most important for the EDA now, given the changing context for its work and the range of places its tools must target? And in what ways should the EDA organize itself to deliver on those functions effectively? To answer these, we offer an organizing framework for legislators to consider so the EDA is equipped with the proper purpose, roles, and capabilities.

The roles of a modern EDA

The EDA has a laudable, aspirational mission. From its website :

Mission: To lead the federal economic development agenda by promoting innovation and competitiveness, preparing American regions for growth and success in the worldwide economy.

The U.S. Economic Development Administration’s investment policy is designed to establish a foundation for sustainable job growth and the building of durable regional economies throughout the United States. This foundation builds upon two key economic drivers — innovation and regional collaboration. Innovation is key to global competitiveness, new and better jobs, a resilient economy, and the attainment of national economic goals. Regional collaboration is essential for economic recovery because regions are the centers of competition in the new global economy and those that work together to leverage resources and use their strengths to overcome weaknesses will fare better than those that do not. EDA encourages its partners around the country to develop initiatives that advance new ideas and creative approaches to address rapidly evolving economic conditions.

Unfortunately, the EDA is not currently structured or resourced to effectively carry out a mission of innovation and competitiveness across the nation’s wide range of regional economies. So let’s clarify the roles and core competencies the EDA must have to meet its mission.

To start, targeting and tailoring are crucial. The EDA’s overarching objective—given its place-based mission—is to unleash the latent economic potential in U.S. regions. To sharpen this purpose, the EDA must recognize that it demands expertise in both innovation and renewal. The former helps larger regions stay on the leading edge of discovery, development, and dynamism. The latter helps economically distressed places of all sizes stabilize or revitalize, putting them on the path to inclusive growth, a better business environment, and a better quality of life for residents. The paths to innovation and renewal have different starting points and, ultimately, different outcomes. They require different strategies, tools, and resources, and their programs are deployed at different scales, such as a region versus a Main Street.

So then, what functions does the EDA require? To successfully unleash regions’ latent economic potential, the EDA must play four essential roles: thought leader, resource provider, capacity builder, and coordinator of federal support for local economic development. These roles complement the key roles of state, local, and public and private sector actors.

- Thought leader: The EDA should be the intellectual home for regional economic analysis and state-of-the-art economic development policy and practice in the U.S. This will inform and guide its own work and expand the sharing of best practices and new ideas across local markets; both are critical to driving better outcomes.

- Resource provider: The EDA should provide large, flexible funding in the form of regular challenge grants to urban and rural regions, so leaders can pursue comprehensive approaches to economic transformation. This is true not just for high-growth regional markets but smaller rural communities as well.

- Capacity builder: The EDA can use its expertise and targeted assistance to build the capacity of local and regional intermediaries to plan and implement effective economic development strategies and use federal and state resources more effectively. Such intermediaries play a vital role in strengthening critical assets and aligning actors, and this EDA role helps them access the training and resources they need.

- Federal coordinator: The EDA can serve as the convener agency working with multiple federal agencies to coordinate, align, or help administer cross-agency federal responses to regional innovation and renewal. Doing so would optimize the use of limited government funding. This function is well precedented in existing law and agency practice, but it needs to be affirmed by Congress and consistently supported by the executive branch.

Funding and the signature activities to fulfill the EDA’s roles

Today, the EDA’s programs are primarily organized around the following specialized investment areas: public works, infrastructure, and facilities; research and technical assistance; economic adjustment grants and disaster recovery; innovation and entrepreneurship; economic development planning; and trade adjustment assistance and consultant services for firms. Together, these wide-ranging programs have been funded at just $283 million per year on average. Through reauthorization, the EDA should emerge as a financially robust agency, with its suite of existing programs anchored by signature initiatives supporting the four key roles described above.

To start, the EDA ought to operate with a dependable annual budget of at least $4 billion, which is commensurate with its vital mission and nationwide mandate. The agency received a $3 billion appropriation in the American Rescue Plan Act—a level we believe should be maintained given widespread demand for the new programs these resources were able to deliver. This would provide the EDA with the consistent scale of resources required to have real impact on local economies, and enable the agency to recruit, train, and retain the staff needed at both headquarters and regional offices to carry out its essential roles. This would also give the EDA the budget space to waive or reduce matching-fund requirements for the jurisdictions that most need help strengthening their economic and fiscal base. An investment of $4 billion in the EDA would match that of its popular complement, the Community Development Block Grant; the Biden administration’s FY 2023 budget request for that program is $3.8 billion.

With those resources, the EDA could implement a set of signature activities that advance the four roles of a modern, place-focused economic development agency. An inventory of existing EDA programs demonstrates critical gaps and the opportunity to prioritize broader, more flexible offerings over narrow, categorical ones that tackle the spectrum of local interests in innovation and renewal. This structure would also allow the EDA to move beyond organizing tactically with a large number of independent programs to organizing strategically around clear national priorities that empower local communities to achieve measurable outcomes (for example, a more competitive and resilient domestic manufacturing base). Most existing programs, and the recommendations of the EDA Stakeholder Coalition, align with those functions. Below are the signature initiatives that could deliver coherently on those functions to ensure a measurable return on the taxpayer’s larger investment in the agency:

- Thought leader: Issue a regular report on the economic health and challenges of U.S. regions and serve as a clearinghouse of state-of-the art strategies.

Given its mandate and resources, the EDA can and should be the go-to resource on the nation’s economic geography, thanks to its on-the-ground knowledge from regional field offices, its expertise in industry clusters, and its access to critical statistical agencies such as the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Census Bureau, also housed in the Department of Commerce.

To anchor this work, every four years, the EDA should produce a signature “State of U.S. Regions” report connecting national competitiveness, economic security, and broad-based geographic opportunity. This report would support improved federal decisionmaking and strategy, build awareness of new ideas across U.S. regions (and the globe), and monitor progress with innovative new initiatives. Additional reporting could address, for example, the health of the labor market, industry clusters, entrepreneurship, and wealth creation by race, gender, and region. This would give local and national leaders a picture of changing market conditions and how national place-based policies can solve problems or facilitate emerging competitive advantages in key sectors in different parts of the country. T hrough this process , the EDA could develop a unified definition of “economic distress” to guide programs that are aimed at supporting distressed places across all federal agencies. Further, the EDA could provide case studies of emerging practices, such as how economic developers are addressing talent needs, how-to guides informed by the work of pioneering intermediaries in the field, and workshops and conferences in which leaders can learn from one another. In this regard, the EDA would be mimicking and aligning itself with leading economic development entities that have strong market research teams—not solely for branding and marketing campaigns, but for helping leaders and partners make well-informed decisions and strategies.

In short, to be an expert on how economic development can best address innovation and renewal, the EDA must have robust in-house staff capacity and expertise of its own, at headquarters and in the field offices, so it can bring that collective knowledge to the field.

- Resource provider: Make permanent the provision of large-scale, flexible challenge grants to boost innovation and competitiveness.

A core function of the EDA should be to manage a rotating set of large-scale competitive challenge grant programs to make flexible, transformative funding available to U.S. regions for pursuing promising innovations and strategies.

The key is to enable the EDA to routinely administer high-demand “big bet” competitions, which have thus far been operated only from one-time supplemental appropriations, as outlined above. This proposal highlights the importance of scale (high-dollar, flexible challenge grants) in driving real, tangible change across regions. As the aforementioned research on growth centers shows, it is critical to help midsized metro areas with high potential for success plug into the innovation economy’s tendency to concentrate in particular places with a critical density of assets. These competitive grants should also reward key outcomes that go beyond traditional job creation metrics. With its thought leadership function, the EDA can then capture lessons and evaluations from innovative practices and share them with other regions to inspire more evidence-driven strategies . Meanwhile, the EDA could support components of non-winning grant applications with existing, targeted EDA programs—for example, in public works or university innovation.

To that end, the $3 billion for the EDA in the American Rescue Plan Act is a model approach. The funding enabled the agency to design and announce a set of grant competitions to meet nationally significant economic recovery priorities, including tech-enabled industry growth, a skilled workforce, travel and tourism, and prosperous Indigenous and coal communities. What’s notable here is that competitive grants can be deployed to support innovation and renewal across large regions as well as smaller urban and rural communities. That approach to allocating resources is inclusive, targeted, tailored, and intensive enough in each economic region to make a meaningful difference.

Within that $3 billion package, the $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge grant program demonstrates the promise of scale and flexibility in promoting global competitiveness. The funding—focused on a planning grant round and then implementation grants of $50 million to $100 million in selected regions—sufficiently empowers local leaders to implement smart, holistic regional cluster initiatives that create lasting economic competitiveness. It is flexible in that it rewards a suite of initiatives identified by multisector leaders (e.g., applied research, workforce training, entrepreneurship, community development) that create the conditions for industry clusters to succeed. What’s more, the program articulates clear and meaningful outcomes such as long-run industry competitiveness, quality jobs, racial and economic equity, and bridging urban and rural divides. As one of our local partners shared, “These targeted investments to fill [key intervention] gaps is one capability that EDA has that maybe no one else does. If this is the direction the EDA is going, then bravo.”

Future EDA challenge grant programs could reward transformative initiatives that connect urban and rural economies through supply chains and other linkages (a core insight from development economists worldwide ); or address specific areas of innovation needs as surfaced by EDA regional clusters research ; or that leverage anchor institutions such as regional public universities to spearhead economic development in distressed places. . The main point is that categorical, capital-intensive project funding will not yield projects that accelerate or reinvent a region’s economic trajectory. Regions need well-resourced challenge grants like Build Back Better to become the norm, because that is what it takes to generate impact.

State and regional stakeholders agree. The EDA received over 500 applications for the Build Back Better Regional Challenge from all 50 states and five territories, for just 60 planning grants and even fewer implementation grants. That’s an indication of the hunger for large-scale economic growth programs and of what’s right about this program’s design.

- Capacity builder: Strengthen the capacity of local and regional intermediaries so they can effectively take on efforts related to both innovation and renewal .

The EDA should have a set of capacity-building programs that meet the needs of large regions and lagging communities. On the former, large metro areas ought not be dismissed as “high-capacity” places that can take care of themselves, when the reality is that organizing cross-sector, multijurisdictional regional competitiveness strategies toward greater equity and inclusion is complex, labor-intensive work. Meanwhile, many rural Main Streets, small towns, and urban corridors do not have the institutions or capacity to plan, design, or kick-start new initiatives to reverse or stem economic distress. In short, the EDA should adopt a flexible, locally responsive approach to capacity building that reflects the continuum of challenges across communities.

To do this, Congress could equip the EDA to administer two broad sets of capacity-building programs.

First, the EDA could offer grants to local, regional, and national intermediaries with the goal of increasing the capacity of local and regional entities to plan, develop, implement, and manage multisector economic revitalization strategies. This includes direct investment in organizations to hire and train staff and use market research. It also includes enabling smaller communities to participate and link up to regional strategies; this could prioritize giving lagging local economies the capacity to compete for large-scale funding, such as the challenge grants described above. Furthermore, via its thought leadership role, the EDA could provide or co-sponsor seminars and training programs for economic development professionals on the latest trends and practices. In short, to move regions out of distress, the EDA should invest in the capability of “backbone” organizations and other implementers to collectively execute high-quality visions and strategies that endure and adapt over time.

Second, the EDA should administer an efficient national corps of deployable talent—for example, a “fellows” program that places qualified economic development professionals in local and regional organizations. These fellows could help local organizations develop regional planning strategies, organize civic planning processes in preparation for competitive grants, put together competitive grant applications, and design and execute key initiatives.

- Federal coordinator: Formalize the EDA’s capacity to coordinate with other federal agencies to ensure federal investment in local economies is cohesive and maximizes benefits.

Federal programs are too often siloed, burdensome to access and use, and not responsive enough to the varied economic conditions and institutional capacities at the local level. There are two ways in which Congress should empower the EDA to be a more effective coordinator of federal support for local economic development.

The first way involves formally elevating the EDA’s role to bring greater coherence to interagency federal place-based economic development when appropriate. This is not a new role for the EDA, given its interagency collaboration on disaster recovery and manufacturing communities . This might include elevating the EDA head from an assistant secretary to an under secretary within Commerce, so its leadership is on par with that of the International Trade Administration or National Institute of Standards and Technology, and more able to convene other cabinet-level agencies. Congress could formally establish and resource the EDA’s small Economic Development Integration office to further the agency’s capacity to coordinate federal programs in its headquarters and field offices. Congress could also expand the EDA’s role as coordinator to include serving as a delivery partner with other agencies eager to benefit from its place-based economic expertise.

Second, Congress could support an EDA planning coordination program to maximize the alignment of federally mandated regional plans, so that required objectives actually map toward achieving coordinated, desired outcomes in communities. Currently, at least three other federal agencies—Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Labor, and Transportation—plus the EDA require regions to produce detailed long-range or consolidated plans. It is commendable that the EDA has worked with other agencies on cross-agency recognition of these plans (e.g., a consolidated plan submitted to HUD can count for the EDA’s program requirements, and vice-versa). However, there is little coordination between the processes driven by multiple agency requirements, resulting in regional plans that often operate on parallel but disconnected tracks, sometimes with contradictory or competing priorities. Yet leaders on the ground know that effective, inclusive regional economic development requires that workforce, housing, land use, and transportation goals and investments work in concert. Grants for this EDA coordination program would increase the capacity of EDA staff and regional entities to regularly convene regional actors, coordinate with the public, align goals and investments, and revise formal plans accordingly. The EDA, HUD, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Transportation, and the Government Accountability Office have all affirmed the need to better coordinate federally funded regional and local planning efforts to ensure federal investments are more strategic, aligned, and effective. Not surprisingly, some of the most promising cross-agency work currently underway is both targeted and outcome driven—for example, seeking to accelerate economic innovation, diversification, and the creation of good jobs in coal and power plant communities.

Beyond these four key roles, the EDA could employ some core principles to inform the design and implementation of its programs, policies, and partnerships. This is what the agency, at its best, already strives to be: flexible , to best meet the unique needs of different communities and regions; locally led , to increase the probability of success and better ensure it avoids favoring some communities over others; equitable and sustainable , to demonstrate that embracing diversity, equity, inclusion, and climate resilience is key to unleashing economic opportunity and boosting U.S. competitiveness; and outcome-driven , to reward local and regional initiatives that identify clear outcomes and measures to gauge progress on those outcomes.

Conclusion

As the U.S. confronts a range of economic shocks and intense global competition for leadership in innovation and economic growth, it is vital that policymakers remember that the nation’s competitiveness depends on the capacities of regions, both urban and rural, to innovate, prosper, and become more economically resilient.

Today, America’s competitive advantages are concentrated in too few places. But there is a way to unleash the economic promise of more places, expand opportunity at home and competitiveness broadly, and make the economy work for all regions and all groups of people. With the EDA, the federal government has an indispensable agency whose sole mission is to revitalize local economies. But for now, the agency is tasked to do too much with too little, with a remit to renew distressed regions and accelerate innovation in others. Doing both effectively is crucial, and it is possible with the right support.

For these reasons, the EDA’s reauthorization and future budget appropriations must go beyond the status quo in order to modernize and equip the agency to do transformative work.

Brookings Metro Global Economy and Development

Center for Sustainable Development

Glencora Haskins, Mayu Takeuchi, Julia Bauer, Patrick Rochford

March 15, 2024

Jenny Schuetz, Eve Devens

March 4, 2024

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Case Studies in Economic Development Third Edition

Related Papers

Babar Chohan

Social Studies. The views stated therein are those of the author and not necessarily those

Tuyền Nguyễn

Anyone who undertakes to produce a volume of surveys in economic development must confront the question: does the world really need another one? There have been four volumes in the present series alone, going back to 1988 (Chenery and Srinivasan, eds.), with the latest collection published in 2008 (Schultz and Strauss, eds.). The field changes over time and, one hopes, knowledge accumulates. So one motive is the desire to cover the more recent advances. And indeed, economic development has been one of the most dynamic and innovative fields within economics in recent years. But we had another motive as well. We envisaged this Handbook to have a somewhat different focus from earlier ones. In particular, rather than just surveying the " state of the literature " in various subfields, what we sought to accomplish is to present critical and analytical surveys of what we know (and don't know) in different policy areas. We asked the authors of each chapter to answer the questions: " What kind of policy guidance does the literature offer in this particular area of development? Where are the gaps? What can we say with certainty that we know? What are the weaknesses of the literature from a policy perspective? What kind of research do we need to undertake to answer burning policy questions of the day? To what extent does actual policy practice correspond to the prescriptions that follow from solid research? " We thus envisioned that the audience for this volume would not only be graduate students and other

Bitew Moges

Ravi Kanbur

Social Change

Vibhuti Patel

Pranab Bardhan

Economic Record

Joseph J. Capuno

SSRN Electronic Journal

Flavia Anghel

Maria Basurto

Author(s): Basurto, Maria Pia | Advisor(s): Robinson, Jonathan | Abstract: This dissertation consists of three self-contained chapters on development economics. The dissertation is focused primarily on one of the largest input subsidy program in the world in terms of how beneficiaries are whether households hide income. As a separate project, I also look at the impact of star students on their siblings test scores in the context of a Peruvian high-achievers national boarding school. In the first chapter, entitled “Measuring Sensitive Questions: Income Hiding and Subsidy Allocation ”, I document the extent to which villagers hide income from local leaders and other villagers as a strategic behavior in the context of a large scale agricultural subsidy in Malawi (FISP). My main contribution is methodological. I use three different measures of income hiding to asses the extent of this practice: direct questions, list randomization, and, willingness to pay to hide income. I find that inc...

RELATED PAPERS

천안출장샵《sod 27, net》천안출장안마《톡:N ω3 0》천안콜걸샵 ど 천안출장마사지 ど 천안일본인출장 ど 천안유흥업소 ど 천안모텔출장만남 ど 천안여대생알바

YadrZQ pplz

Revista Chilena de Estudios Medievales

Néri de Barros Almeida

Heidi Schnackenberg

Jatmika Yullandari

Journal of Korean Tunnelling and Underground Space Association

Sooho Chang

Ana Amélia Camarano

Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences

Lindsay Anderson

BioMed Research International

Mathieu Bélanger

Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society

Peter Minnett

Advanced Optical Materials

Ki-Hun Jeong

Icidca Sobre Los Derivados De La Cana De Azucar

Gayathri Ravi

Research in Learning Technology

Daniel Khalil

J Comput Sci Syst Biol

clelia di serio

satish bhairannawar

Proceedings of the International Association of Hydrological Sciences

Jiri Jakubinsky

Joao Dos Santos Vila Da Silva

Journal of Medical Case Reports

hendrik andrianto

Journal of evolution of medical and dental sciences

Uma Patnaik

Multidisciplinary cancer investigation

Alvaro Ronco

ToscanaNovecento. Portale di Storia Contemporanea

Giovanni Brunetti

Journal of Medical Microbiology

DergiPark (Istanbul University)

Sadullah Girgin

Jeramie Adams

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Sustainable, inclusive housing growth: A case study on Columbus, Ohio

Over the past two decades, the Columbus region has enjoyed outsize population and economic growth compared with leading peer cities and the US average. 1 In this article, “Columbus” refers to the Columbus metropolitan statistical area unless otherwise specified. See “Ohio Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs),” Ohio Department of Job and Family Services, Office of Workforce Development, accessed June 22, 2023. Yet growth has come at a cost—specifically by outpacing the region’s supply of available housing. Home and rental prices have soared as stock has been depleted, making homeownership—and sometimes even having a roof over one’s head—increasingly out of reach for many people, particularly those from historically marginalized communities.

About the authors

This article is a collaborative effort by Brandon Carrus , Seth Myers , Brian Parro, Duwain Pinder , and Ben Safran, representing views from McKinsey’s Social Sector Practice.

In just this past decade, the increase in housing prices and rents has dramatically outpaced household income. Additionally, the region’s population of people experiencing homelessness (PEH) has grown faster than those of its US peers in recent years. The region’s challenges have a disproportionate impact on historically marginalized populations (such as Black and Hispanic residents), who have a dramatically lower likelihood of being a homeowner and a much higher likelihood of experiencing homelessness. Amid ongoing rapid growth, the need for affordable housing and support services for PEH will only continue to increase unless significant action is taken. 2 HUD defines affordable housing as “housing on which the occupant is paying no more than 30 percent of gross income for housing costs, including utilities.” See “Glossary of terms to affordable housing,” HUD, accessed June 22, 2023.

Columbus is a microcosm of the United States’ housing insecurity plight. While many major cities are receiving national press coverage for this issue, housing insecurity is a humanitarian challenge facing communities of all sizes across the country. The National Association for Home Builders estimates that about 70 percent of US households cannot afford a new home at the national median price. 3 NAHBNow , “Nearly 7 out of 10 households can’t afford a new median-priced home,” blog entry by National Association of Home Builders, February 15, 2022. In 2022, US home vacancy rates were at their lowest levels since 1987, 4 “Home vacancy rate for the United States,” US Census Bureau, retrieved from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED) June 22, 2023. and the country is estimated to have a shortage of 6.5 million housing units. 5 Anna Bahney, “The US housing market is short 6.5 million homes,” CNN, March 8, 2023. Renters are also facing increased pressure nationally: 23 percent spend at least half of their income on housing costs, 6 Katherine Schaeffer, “Key facts about housing affordability in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, March 23, 2022. rendering them “severely rent burdened” as defined by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). 7 “Rental burdens: Rethinking affordability measures,” PD&R Edge, accessed June 22, 2023.

As in many regions in the United States, the primary contributors to the housing shortage in Columbus are embedded within deeply vexing economic and social issues, including stagnating incomes, racial gaps in homeownership, and access to financing and services.

As Columbus charts a growth strategy for the decades ahead, addressing housing and homelessness will be an essential component in realizing the goal of prosperity for all. Today, Columbus is projected to have a shortage of as much as 110,000 housing units by 2032. 8 Vogt Strategic Insights, “Analysis of housing need for the Columbus region,” Building Industry Association of Central Ohio, August 30, 2022. Without an increase in the supply of housing, Columbus may struggle to continue on a growth trajectory. Specifically, we have identified four priority interventions designed to work in concert to increase housing stock, keep rents affordable, and help more people, including historically marginalized populations, access the housing market:

- Tap into existing housing capacity potential. Public–private collaboration on policies can identify land available for housing either as underused property or as part of broader rezoning efforts to increase the supply of homes, which is a requirement for sustained economic growth.

- Reduce the cost of new construction. Promising cost-reduction opportunities include simplifying the permit process and engaging builders with expertise in cost-effective construction methods.

- Support homebuyers and renters. Local government and policy makers can expand resources and consider policies that support public- and private-sector initiatives to improve homeownership rates, assist with rental affordability, and reduce the risk of homelessness.

- Prioritize tackling homelessness. Alleviating homelessness requires increasing awareness of currently available resources for PEH and expanding relief funds to assist residents with affordable housing, healthcare support, training for employment, and other resources critical to reducing homelessness.

Many local leaders are well aware of the challenges that can result from booming growth. The policy-neutral research presented in this article is intended to complement the work already under way by leaders in the city of Columbus and surrounding areas to inform decision making about the housing shortage, affordable housing, and homelessness. 9 For example, see Bonnie Meibers, “Columbus details plan to build, preserve and invest in inclusive affordable housing,” Columbus Business First , June 27, 2022; Bonnie Meibers, “Columbus City Council announces 12-part plan to combat affordable housing shortage,” Columbus Business First , March 16, 2023; Bonnie Meibers, “The Punch List: Columbus lays out new solutions to housing crisis,” Columbus Business First , October 24, 2022; Mark Ferenchik, “Worthington considering asking for $1.1M affordable housing bond issue on November ballot,” Columbus Dispatch , January 16, 2023. In the process, we believe the Columbus region’s approach to housing could both build on and inform the economic development strategies of other regions across the country—with successes offering a potential blueprint for progress.

The fastest-growing region in the Midwest

From 2000 to 2021, the Columbus Region’s population increased by a third, adding more than 500,000 people and becoming the fastest-growing metropolitan statistical area (MSA) in the Midwest. 10 “Resident population in Columbus, OH (MSA) [COLPOP],” US Census Bureau, retrieved from FRED April 7, 2023. Includes MSAs with populations greater than one million. Midwest defined as Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. See “Resident population in Columbus,” retrieved April 7, 2023; Factbook 2020 , City of Columbus, accessed June 22, 2023. In September 2022, Columbus was named the fifth-hottest housing market in the United States, driven by the speed of home sales and demand. 11 “CAGDP1 County and MSA gross domestic product (GDP) summary,” US Bureau of Economic Analysis, accessed May 12, 2023; “Table 1.1.6. Real Gross Domestic Product, Chained Dollars,” US Bureau of Economic Analysis, accessed May 12, 2023.

This growth was precipitated by, and continues to benefit from, the region’s mounting economic strength: from 2008 through 2021, Columbus outpaced national GDP growth by almost ten percentage points. 12 “Total gross domestic product for Columbus, OH (MSA) [NGMP18140],” US Bureau of Economic Analysis, retrieved from FRED June 23, 2023; “Gross domestic product [GDP],” US Bureau of Economic Analysis, retrieved from FRED June 23, 2023. Growth has also been bolstered by more-recent major commercial investments from a range of industries, including semiconductors, financial services, and biopharmaceuticals. 13 “Intel breaks ground in Ohio,” JobsOhio, accessed June 22, 2023; “Project announcements,” One Columbus, accessed June 22, 2023; “Western Alliance Bank expands into the Columbus Region, creating 150 new jobs at new technology hub,” One Columbus, January 9, 2023; “Discover plans to open a customer care center in Whitehall to bring high-quality jobs and enhance equity in the Columbus Region,” One Columbus, November 18, 2022.

Growing pains: Coping with rapid growth

The population influx has measurably strained Columbus’s residential real estate and rental markets, particularly for people of color. Increasing housing supply is a critical enabler for the region’s continued growth trajectory.

Increasing housing supply is a critical enabler for the region’s continued growth trajectory.

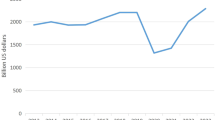

Rapidly rising home prices. Although the region remains relatively affordable compared with leading peers, home prices have skyrocketed in relation to incomes. Data from Zillow reveal that roughly a decade ago, the growth of median household incomes in Columbus and the value of the city’s “lower tier” housing stock began to diverge (Exhibit 1). In the ten years since then, lower-tier housing prices within the city’s boundaries increased at 1.9 times the growth of median household income—an unsustainable divergence. 14 Zillow Home Value Index (ZHVI) All Homes - Bottom Tier Time Series, accessed April 19, 2023. A cavalry in the form of new-housing construction may be slow to arrive: from 2004 to 2022, annual construction of new single-family homes in Columbus fell by 34 percent, and it has yet to return to pre-2004 levels. 15 “B19013 Median household income in the past 12 months,” ACS 5-Year Estimates 2016–21, American Community Survey, US Census Bureau. In fact, for every 100 net new jobs in the region, only 65 new housing permits were issued. 16 Analysis of housing need for the Columbus region , Vogt Strategic Insights, August 30, 2022.

Rent increases outpacing wage increases. Renters in Columbus have also seen a price surge.

Rent prices in Columbus increased by about 35 percent between December 2016 and December 2021, exceeding median household income growth in that period by 11 percentage points (Exhibit 2). As a result, by 2021, approximately 40 percent of renters in Columbus were spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent, meeting HUD’s definition of “rent burdened.” 17 “Gross rent as a percentage of household income,” 2021: ACS 5-Year Estimates, American Community Survey, US Census Bureau. And renters account for a significant percentage of residents: as of 2021, nearly 40 percent of total households in the metro area were rentals, which is comparable to other fast-growing US regions such as Austin (around 41 percent) and Miami (about 40 percent) but much higher than similar sized regions such as Pittsburgh (around 29 percent) and Indianapolis (about 32 percent). 18 “B25008 Total population in occupied housing units by tenure,” 2021: ACS 1-Year Estimates, American Community Survey, US Census Bureau.

More people experiencing homelessness.

Columbus outpaced its US peers in the growth of its PEH population from 2008 through 2022 (Exhibit 3), and early reports indicate homelessness was up 22 percent in January 2023 compared with January 2022. 19 “Columbus region leaders introduce new action on homelessness: Funding for programs and services introduced as data shows increase in homeless count,” Community Shelter Board, June 6, 2023. McKinsey research on homelessness in the Bay Area indicates that homelessness is a result of a range of disparate triggers, including economic issues (such as job loss, raised rent, or foreclosure), health factors (such as substance abuse or mental illness), and social factors (for example, incarceration or domestic violence). 20 For more, see “ The ongoing crisis of homelessness in the Bay Area: What’s working, what’s not ,” McKinsey, March 23, 2023. A brief but significant drop in the number of PEH in Columbus in 2021 is likely attributable to additional support during the pandemic (for example, eviction moratoriums and stimulus payments). Still, as of 2022, Columbus had the fastest-growing PEH population among its peers.

Columbus outpaced its US peers in the growth of its PEH population from 2008 through 2022, and early reports indicate homelessness was up 22 percent in January 2023 compared with January 2022.

Disproportionate effect on historically marginalized communities. The racial disparities that plague many leading US regions are also starkly apparent in Columbus. Some historically marginalized groups are less likely to be homeowners: one-third of the region’s Black households own their homes, compared with more than two-thirds of White households (Exhibit 4). Black household incomes in the region are also about 42 percent lower than those of White households. 21 “S1903 Median income in the past 12 months (in 2021 inflation-adjusted dollars),” 2021: ACS 1-Year Estimates, American Community Survey, US Census Bureau.

In addition, Black residents account for 16 percent of Columbus’s general population but 60 percent of the homeless population. 22 “DP05 ACS demographic and housing estimates,” 2021: ACS 5-Year Estimates Data Profiles, American Community Survey, US Census Bureau; “PIT and HIC data since 2007,” HUD Exchange, February 2023. And even when people in these communities have housing, Black households are almost five times more likely to be overcrowded (more than one occupant per room) than White households. 23 “B25014B Occupants per room (Black or African American alone householder),” 2021: ACS 5-Year Estimates, American Community Survey, US Census Bureau; “B25014A Occupants per room (White alone householder),” 2021: ACS 5-Year Estimates, American Community Survey, US Census Bureau. These disparate experiences in different communities are reflected in other metrics of financial and housing stability, including income and the ability to pass on generational wealth. 24 “B19013B Median household income in the past 12 months (in 2021 inflation-adjusted dollars) (Black or African American alone householder),” 2021: ACS 5-Year Estimates, American Community Survey, US Census Bureau; “B19013A Median household income in the past 12 months (in 2021 inflation-adjusted dollars) (White alone householder),” 2021: ACS 5-Year Estimates, American Community Survey, US Census Bureau; Jung Hyun Choi, Laurie Goodman, and Jun Zhu, Intergenerational homeownership: The impact of parental homeownership and wealth on young adults’ tenure choices , Urban Institute, October 2018.

These disproportionate effects have wide-ranging impact, including on overall economic growth. PolicyLink and the USC Equity Research Institute estimate that the racial gap in Columbus is costing the region’s economy $10 billion annually. 25 Erica Thompson and Mark Williams, “Racial inequities costs Columbus economy $10 billion a year, report finds,” Columbus Dispatch , updated May 12, 2022.

Four interventions to address Columbus’s housing challenges

Housing is a critical enabler for economic growth—and Columbus’s housing challenges are no secret. Local leaders, organizations, and partnerships have long worked to improve housing security directly. Advocates and organizations have all published research on housing and homelessness, including the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission, the Coalition on Housing and Homelessness in Ohio, the Affordable Housing Trust for Columbus & Franklin County, the Center for Social Innovation, and the Community Shelter Board of Columbus. 26 Healthy Beginnings at Home: Final report , CelebrateOne and the Health Policy Institute of Ohio, June 2021; Regional Housing Strategy final report: Central Ohio , Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission, September 2020; Annual report 2021: Preserving, creating & facilitating , Affordable Housing Trust for Columbus and Franklin County, 2021; Columbus, Ohio: Initial findings from quantitative and qualitative research , Supporting Partnerships for Anti-Racist Communities (SPARC), Center for Social Innovation, May 2018. Yet the latest estimates show that the region could need as many as 110,000 housing units beyond the current run rate by 2032 to cover expected job growth. This would require more than doubling the construction rate, from around 8,300 units per year to as many as 19,300 per year. 27 Analysis of housing need for the Columbus region , Vogt Strategic Insights, August 30, 2022.

After reviewing the available research, examining the actions taken by other local governments, and drawing on our experience in the real estate and public sectors, we have identified four key interventions that can augment existing efforts to address Columbus’s housing challenge: tap into existing housing capacity potential, reduce the cost of new construction, support homebuyers and renters, and prioritize tackling homelessness.

Tap into existing housing capacity potential

Zoning regulates how land is used, where residential or commercial buildings may be constructed, and the density of new developments, making it a key lever in changing a city’s residential landscape. The city of Columbus spans 220 square miles of central Ohio, and it has 50 more square miles of single-family zoning than multifamily zoning. 28 Nicholas Julian, “Zoning in Columbus: Single-family vs. multifamily,” Ohio Housing Finance Agency, April 2, 2019; “QuickFacts: Columbus city, Ohio,” US Census Bureau, accessed June 22, 2023. Increasing density and creating housing “hot spots” are both potential options for Columbus to address current housing supply challenges.

Increased housing density. Zoning has a direct impact on housing density. In Washington, DC, for example, areas zoned for detached single-family units typically consist of up to 1,200 units per square mile, 29 Yesim Sayin, “Single-family zoning and neighborhood characteristics in the District of Columbia,” D.C. Policy Center, July 17, 2019. compared with up to 40,000 units per square mile in large multifamily buildings. But zoning in most US cities largely restricts higher-density homes. Three-quarters of the land in US cities is barred from development for anything other than detached single-family homes—and where multifamily buildings are allowed, height and lot size requirements hurt the economic calculus for development. 30 Jenny Schuetz, “To improve housing affordability, we need better alignment of zoning, taxes, and subsidies,” Brookings Institution, January 7, 2020. Specific zoning adjustments could contribute directly to closing the housing gap, not just in the city limits but also in the surrounding suburbs. For example, a recent analysis by the Columbus Dispatch found that zoning contributed to the lack of affordable housing options in Upper Arlington, New Albany, and suburbs in Delaware County. 31 Jim Weiker, “Columbus suburbs offer few affordable housing options,” Columbus Dispatch , May 4, 2023. High-density zoning can be a meaningful part of a community’s housing ecosystem to enable future growth.

‘Housing hot spots’ created by reusing and rezoning underused property. To help alleviate the shortage of homes in the near term, municipalities can also identify potentially high-impact housing areas by reviewing the zoning of properties that meet criteria for vacant or underutilized land, homes with room for more units, and more. This approach has been used elsewhere to great effect. An analysis of three counties in California found room for more than five million new units, 32 Jonathan Woetzel, Jan Mischke, Shannon Peloquin, and Daniel Weisfield, “ Closing California’s housing gap ,” McKinsey Global Institute, October 24, 2016. and separate efforts are under way in New York City and Los Angeles to rezone underused commercial zones for residential or mixed use—making more space available for housing construction without needing to expand a city’s footprint. 33 “Mayor Adams unveils recommendations to convert underused offices into homes,” City of New York, January 9, 2023; “Adequate sites for housing,” 2021–2029 Housing Element , Los Angeles City Planning, November 2021.

Reduce the cost of new construction

A priority for the Columbus region will be reducing the cost of new construction to accelerate the pace of development. Programs that accelerate construction, reduce permit fees, or otherwise defray development costs are common levers to help reduce the cost of affordable housing. Several approaches can be prioritized to address the challenges facing Columbus and other US regions.

Innovative, cost-saving construction techniques and builders. As in many areas of the United States, inflation drove up the cost of building materials, labor, and financing in Columbus by as much as 18 percent between 2021 and 2022. 34 “How much does it cost to build a house in Columbus?,” Home Builder Digest , accessed June 23, 2023. Innovative, low-cost approaches such as modular and prefabricated construction can help; in our experience, when applied at large scale, these techniques can reduce the cost of construction materials by up to 20 percent and decrease build time by 20 to 50 percent without sacrificing build quality. 35 Modular construction: From projects to products , McKinsey, June 18, 2019. This is especially true with projects featuring repeatable elements, such as schools and affordable housing.

Columbus, specifically, can establish itself as a center of excellence for modular and prefabricated construction by leveraging the region’s transportation network (such as railroads and highways) to efficiently transport modular units into the region. The region can further attract builders that use these construction techniques by offering tax incentives, investing in land and modular units at scale, reskilling the labor force, and streamlining the approval process to help drive affordable housing growth. These and other approaches could improve the economics for these kinds of construction projects almost immediately once implemented. For example, Portland, Oregon, made changes to its design review process to allow mixed-use and multifamily projects to go directly to the permit process, saving developers time and money by decreasing their financing costs. Local governments in the Columbus region can further improve the economics of housing development by producing and holding off-the-shelf design schematics that can easily be used by prospective housing-unit developers.

Reduced development costs. Identifying parcels of public land for housing development could defray the overall cost of new projects in addition to rezoning efforts. Some cities, including Copenhagen, London, New York City, and Stockholm, have established professional management of their publicly owned land, allowing them to identify suitable city-owned sites for affordable developments. 36 “ Affordable housing in Los Angeles: Delivering more—and doing it faster ”, McKinsey Global Institute, November 21, 2019.

Accelerating the construction permit process could help reduce lengthy permit timelines that both create delays and increase developers’ costs. Under Columbus’s permit approval system, new-construction permits can take six to nine months. In fast-growing metro areas elsewhere in the United States, permits can take as little as a few weeks—a disparity that the City of Columbus is reviewing as part of its longer-term affordable-housing initiatives. 37 Allen Henry, “Columbus to overhaul zoning code for first time in 70 years,” NBC4 WCMH-TV, October 20, 2021. The Affordable Housing Trust in Columbus has launched the Emerging Developers Accelerator Program to provide education and funding for minority developers. 38 Jim Weiker, “New program seeks to build ranks of minority and female developers,” Columbus Dispatch , updated May 18, 2022. Yet the holding costs due to the lengthy time horizon between initial plans and selling the first house keep many potential developers out of the business.

Reduced development finance costs and fees. Financing costs and government taxes tend to be a heavy burden on housing developers. Legal agreements and public financing tools, such as joint powers authorities (JPAs) and tax increment financing (TIF) programs, provide incentives for public and private partners to collaborate in the development of affordable housing. In instances where traditional incentives and subsidies are unable to produce the desired outcomes, JPAs enable the city, partnered with a developer, to issue bonds and use its property tax exemption to purchase a property or finance the creation of a new development process. As part of the acquisition process, the JPA agrees to restrict the rent of a set number of units in line with affordable-housing standards. This approach is unlike traditional affordable-housing projects in that long-term ownership rests with the city, with an option to purchase the property back from the JPA after a set period.

JPAs are eligible for significant tax exemptions on their properties, with the added benefit that these savings are passed on to renters. Bond financing can also be tax-exempt given that governmental bodies have the authority to issue tax-exempt bonds for facilities that provide a public benefit. 39 “Portantino bill creating regional affordable housing trust passes assembly local government committee,” Senator Anthony J. Portantino, California State Senate, June 9, 2022; Brennon Dixson et al., The ABCs of JPAs , SPUR and the Terner Center for Housing Innovation, June 2022. In California, the Burbank-Glendale-Pasadena Regional Housing Trust is leveraging these benefits to address barriers to building nearly 3,000 affordable-housing units in the region. 40 “Newsom signs Portantino bill creating Pasadena-Glendale-Burbank affordable housing trust,” Pasadena Star-News , August 24, 2022. The JPA will be allowed to request and receive private and state funding allocations, as well as authorize and issue bonds, to help finance affordable-housing projects.

As another option, TIF districts enable cities to freeze property tax revenue at current levels and use incremental tax revenue generated from a development to reimburse the developer’s costs over time. In 2018, for example, the City of Chicago approved TIF measures for The 78, a $7 billion mixed-use project to transform a former railroad property into 13 million square feet of residential, commercial, and institutional construction with a 20 percent commitment for affordable-housing units. According to plans, this TIF district will reimburse around $551 million in future increments for the construction of new infrastructure related to this project, including a new subway station, street improvements and extensions, and riverfront renovations. 41 “The 78,” Department of Planning and Development, City of Chicago, accessed June 23, 2023.

Support homebuyers and renters

In conjunction with initiatives that improve the supply of affordable housing, Columbus can explore approaches that improve an individual’s ability to pay for housing. The region can take these approaches in tandem to reduce the risk that demand will outpace supply and drive up prices on housing, making it even more unaffordable.

Homebuyer assistance from the public sector. Increasing investment in housing programs could help broaden the range of homes applicants can consider purchasing. For example, the City of Columbus’s Housing Division currently offers homebuyer assistance under its American Dream Downpayment Initiative (ADDI), which provides eligible first-time homebuyers with a loan of up to 6 percent of the purchase price (or up to $7,500) to put toward their down payment. 42 “American Dream Downpayment Initiative (ADDI) Program,” City of Columbus, accessed June 23, 2023. This loan is forgiven after five years if the resident meets certain requirements, including maintaining residency and not selling the property.

In Cleveland, Cuyahoga County’s Down Payment Assistance Program covers up to 10 percent of a home’s purchase price (or up to $16,600). 43 “Cuyahoga County Down Payment Assistance Program,” CHN Housing Capital, accessed June 23, 2023. This higher amount is especially significant given that the median sale price for a home in Columbus was $250,000 in December 2022, compared with $175,000 in Cuyahoga County and $115,000 in Cleveland itself. 44 “Columbus housing market,” Redfin, accessed June 23, 2023. The down payment program available in Cleveland provides greater assistance in real dollars in an area where those dollars can go further than in Columbus. Beyond affordable housing, assistance in the form of microloans and flexible funding programs have been shown to enable this transition. 45 Interval House, “How flexible funding can create stability and prevent homelessness,” Long Beach Community Foundation, accessed June 23, 2023.

Increasing the amount of assistance available could help broaden the options available to prospective homebuyers who could benefit from programs such as these, especially for historically marginalized communities that tend to have much lower rates of homeownership.

Rental assistance from the public sector. Some 54,000 households in the Columbus region are spending more than half their monthly incomes on rent, making rental assistance a cornerstone of the effort to improve housing affordability in the region. 46 Homeport website, US Department of Homeland Security and the United States Coast Guard, accessed June 23, 2023. Today, the State of Ohio and Franklin County have a number of rental assistance programs, including specific funds to help families, seniors, and veterans. 47 “Rent assistance providers,” Rentful, accessed June 23, 2023. Alternative programs, including flexible funding that allows for short-term, flexible financial assistance, could help stabilize individuals’ housing needs. 48 “How flexible funding can create stability,” accessed June 23, 2023.