- Search the database

- V International Research Conference - Hamburg 2022

- IV International Research Conference - Santiago de Chile 2019

- III Gestalt Therapy Research Conference - Paris 2017

- Rome Seminars 2014

Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy

Gestalt therapy applied: a case study with an inpatient diagnosed with substance use and bipolar disorders, valerie dominitz.

The aim of the present paper is to open the discourse regarding the unmet needs of specific patients, especially those with substance use disorder and/or personality disorder where ‘multimorbidities’, and/or ‘overdiagnosis’ and/or ‘diagnosis overlap’ are frequent. An additional aim is to review the main therapeutic purpose and concepts of Gestalt therapy which might be appropriate in the treatment of these patients often characterized by their difficulties in being aware and in contact in the ‘here and now’. Methods I first start with an overview of Gestalt therapy concepts. Then, I illustrate Gestalt's ‘here and now’ and awareness concepts applied during 18 sessions with an inpatient diagnosed with substance use and bipolar disorders. In addition, the patient had to face an open criminal charge, was regarded as having an antisocial personality disorder and argued suffering from post‐traumatic stress disorder. Results After this two‐month therapy period, the patient entered for the first time a daily rehabilitation program in the community, where he was doing well (this after a few prior hospitalizations). The awareness development in the ‘here and now’ through which different contact styles and cycles of experiences are experienced is a process that allowed the patient to start experiencing contact with himself, his true needs and his environment. This contributed to his well‐being improvement, led and supported his rehabilitation and reinsertion within the society and decrease his relapses, either with drugs or criminal activities.

APA citation

Dominitz, V . (2017). Gestalt therapy applied: A case study with an inpatient diagnosed with substance use and bipolar disorders . Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy , 24 , 36-47, . https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2016

- linkedin-in

Gestalt Therapy Applied: A Case Study with an Inpatient Diagnosed with Substance Use and Bipolar Disorders

Affiliation.

- 1 Private Practice, Tel Aviv, Israel.

- PMID: 27098212

- DOI: 10.1002/cpp.2016

Aim: The aim of the present paper is to open the discourse regarding the unmet needs of specific patients, especially those with substance use disorder and/or personality disorder where 'multimorbidities', and/or 'overdiagnosis' and/or 'diagnosis overlap' are frequent. An additional aim is to review the main therapeutic purpose and concepts of Gestalt therapy which might be appropriate in the treatment of these patients often characterized by their difficulties in being aware and in contact in the 'here and now'.

Methods: I first start with an overview of Gestalt therapy concepts. Then, I illustrate Gestalt's 'here and now' and awareness concepts applied during 18 sessions with an inpatient diagnosed with substance use and bipolar disorders. In addition, the patient had to face an open criminal charge, was regarded as having an antisocial personality disorder and argued suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Results: After this two-month therapy period, the patient entered for the first time a daily rehabilitation program in the community, where he was doing well (this after a few prior hospitalizations). The awareness development in the 'here and now' through which different contact styles and cycles of experiences are experienced is a process that allowed the patient to start experiencing contact with himself, his true needs and his environment. This contributed to his well-being improvement, led and supported his rehabilitation and reinsertion within the society and decrease his relapses, either with drugs or criminal activities. Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Key practitioner message: People with substance use disorder (where 'multimorbidities', 'overdiagnosis' or 'diagnosis overlap' are frequent), people with personality disorder(s) or people who have difficulties in defining what really disturbs them are the same people who could benefit of GT encouraging awareness and contact development in the 'here and now'. Gestalt therapy should not be regarded as a practitioner's toolbox but as a therapeutic process allowing awareness and I-boundaries development in the 'here and now' through authentic and genuine relationships. The therapist's awareness and contact with themselves and their environment are reflected in the therapist's relaxed but awake and aware state of mind as well as their wise, spontaneous and mindful approach.

Keywords: Awareness; Bipolar Disorder BP; Gestalt Therapy; Personality Disorder PD; Substance Use Disorder SUD; Therapeutic Relationship.

Copyright © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Publication types

- Case Reports

- Antisocial Personality Disorder / diagnosis

- Antisocial Personality Disorder / psychology

- Antisocial Personality Disorder / therapy

- Bipolar Disorder / diagnosis*

- Bipolar Disorder / psychology

- Bipolar Disorder / therapy*

- Child Abuse / diagnosis

- Child Abuse / psychology

- Child Abuse / therapy

- Combined Modality Therapy

- Comorbidity

- Diagnosis, Dual (Psychiatry)

- Follow-Up Studies

- Gestalt Therapy*

- Hospitalization*

- Illicit Drugs*

- Life Change Events

- Quetiapine Fumarate / therapeutic use

- Substance-Related Disorders / diagnosis*

- Substance-Related Disorders / psychology

- Substance-Related Disorders / therapy*

- Illicit Drugs

- Quetiapine Fumarate

- Mental Health Academy

- Case Studies

- Communication Skills

- Counselling Microskills

- Counselling Process

- Children & Families

- Ethical Issues

- Sexuality & Gender Issues

- Neuropsychology

- Practice Management

- Relationship Counselling

- Social Support

- Therapies & Approaches

- Workplace Issues

- Anxiety & Depression

- Personality Disorders

- Self-Harming & Suicide

- Effectiveness Skills

- Stress & Burnout

- Diploma of Counselling

- Diploma of Financial Counselling

- Diploma of Community Services (Case Management)

- Diploma of Youth Work

- Bachelor of Counselling

- Bachelor of Human Services

- Master of Counselling

A Case for Gestalt Therapy

Author: Jane Barry

Komiko is from a second-generation Asian family. She has lived in Australia all her life, yet her Asian roots are deep. She has been raised according to traditional Asian culture and in addition, she and her family are devout Catholics. Komiko has never questioned her upbringing before, yet now at the age of 26 she is struggling with value conflicts relating to her religion, culture and sex-role expectations and has come to counselling in order to allay some of her confusion.

A précis of the sessions is as follows. For ease of writing the Professional Counsellor is abbreviated to “C”.

Background Information

Komiko had a strict and formal upbringing with her parents and the various Catholic schools that she attended. She was taught to always honour and respect her elders, such as her parents, teachers and priests. Because of this she explains that she has never really felt independent of figures of authority, and has usually acted out the role of a willing child. She states that she seeks the approval of those in authority and whenever she attempts to assert her own will, she experiences guilt and self-doubt.

She has always followed closely the rules and morals of the Catholic Church, through her school and adult life. Komiko has never been married, nor has she had a long-term relationship or experienced sexual intimacy. She states that this is primarily because of the codes she has learned to live by, however there have been times when she has wanted to break away from these. She is interested in living away from her parents and experiencing a relationship out of wedlock, however she is afraid that if she does so, her parents will not accept her decisions.

Although Komiko is frightened to break away from the codes and rules that she has learned, she is seriously considering their validity and realism. She has noticed a change in her own beliefs about morality, and how she no longer accepts her family’s and church’s beliefs without question. She wonders about the importance of her own individual conscience, and following her changing beliefs. The questions she asks herself include: What if I am wrong? Who am I to decide what is moral or immoral? What will I discover if I follow my own path? Will I lose my self-respect or be able to survive the guilt I feel if I don’t follow the teachings of my church and parents?

Generally, Komiko would like to be less dependent, less socially inhibited, less emotionally reserved and be more assertive and able to make important decisions in her life. Instead she finds that she is extremely self-conscious and always considers how she should and should not act. She wonders if she has the strength to act in opposition to what she has learned from her culture, her parents and her church.

Session Content

After drawing out Komiko’s story and beliefs, “C” considers some of the core issues that she is facing. “C” summarises the nature of Komiko’s struggle as follows:

Child roles vs Adult roles:

- Catholic morals vs non-Catholic morals

- Asian influences vs Western influences

Whilst listening to Komiko, “C” considers briefly her own opinions about these conflicts. “C” is a Western, non-Catholic woman and realises her own biases in these arguments may lead her to influence Komiko away from traditional, Asian and Catholic codes of living. “C” also considers that Komiko may be looking to “C” as someone in authority to grant her permission to act more in accordance with her own views.

“C” started with a warm up exercise with Komiko. “C” asked Komiko to summarise the way she was feeling about herself. Komiko stated that she felt self-conscious, weak willed, lacking in assertiveness and dependent. “C” discussed these opinions further with Komiko and asked her questions such as “How are you dependent? Who is responsible for your self-consciousness? What do you take responsibility for?”

Komiko became aware of her passivity through this exercise, and her tendency to allow others to dictate how she should live. “C” then asked Komiko to use the “I take responsibility for.” exercise where she repeated out-loud, all of the current feelings that she was responsible for. “C” then encouraged Komiko to take responsibility for the goals she wanted to achieve.

Komiko said:

- I am responsible for my self-consciousness.

- I am responsible for my dependency.

- I am responsible for my independence.

- I am responsible for my decision making.

“C” added some responsibilities of her own:

- I am responsible for helping you explore your blockages.

- I am responsible for allowing you to make your own choices.

- I will not take responsibility for your decision making.

This exercise allowed “C” and Komiko to examine their roles in the counselling relationship and reinforced that Komiko was responsible for the decision making. Komiko and “C” both were fairly warmed up after this exercise, so “C” encouraged Komiko to perform a dialogue exercise between her assertive self and her unassertive self. “C” explained that this was a chance for both of these sides to talk to each other and air their grievances.

“C” said to Komiko, “In this first chair I want you to position yourself as your assertive self. Your assertive self should talk to your unassertive self in this other chair. “As your assertive self, I want you to sit, speak and act in an assertive manner. You should tell your unassertive side what it is you want to be more assertive about and why.”

As Komiko progressed through this exercise, “C” prompted her to talk about what her assertive side felt and to point out what she didn’t like about her unassertive self. Komiko grew slowly into her role as her assertive self. She experimented with the role of advice giver and decision maker, clarifying the choices that she wanted to make in regards to her life. In particular these included moving out of her parental home and pursuing a relationship.

After this point, Komiko was a little quiet. When prompted to speak, Komiko explained that she feared her parent’s response to these changes. “C” then suggested that Komiko take on her unassertive side. Komiko’s unassertive side defended some of the actions and principles of her traditional upbringing. She explained some of the value that she saw in behaving in accordance with the belief’s of her parents. She wanted to make her own choices, but she wanted her parent’s approval to do so. She was afraid that they would not tolerate her decisions. She explained that some of her parent’s expectations included having supervised dates with young men, living at home until she was married, preferably marrying a Japanese man, wearing skirts and dresses and generally keeping a feminine appearance.

After lengthy discussions with her two sides, Komiko came to realise more clearly the nature of her conflict. Her assertive side wanted to move out of home and be more independent, realising that she may have to live with the disapproval of her parents for a while. Komiko’s unassertive side felt afraid without the support of her family. She thought that maybe she could ease her parents into the idea of her moving out by starting to collect furniture, saving money, looking for suitable apartments and discussing her plans with them.

“C” suggested to Komiko to consider the consequences of moving out on her own, or staying in her parents house. “C” also suggested to Komiko to write a letter to her parents, to tell them of her fears of their disapproval and the consequences this has for her. “C” explained to Komiko that the letter should not be sent, but that she could bring the letter to their next session to discuss its meaning.

In the final part of the session, “C” asked Komiko how she might feel about attempting a more difficult exercise – playing the role of her non-Catholic self, non-traditional self. “C” explained that Komiko was already well acquainted with her Catholic/traditional self and suggested that she experience what it would be like to be her non-Catholic, non-traditional self.

Initially Komiko was hesitant and didn’t understand how she might act as a non-Catholic or non-traditional self. “C” suggested that she think about how she might look, what she might wear, how she might do her hair. Komiko thought that she might wear pants more often, dress in a less feminine style and cut her hair shorter. She practiced walking around the room, as this side of herself, slowly gaining confidence to put a bounce in her step and imagining her hair to be shorter and coloured. She was quite shy about her performance and so “C” joined in also, by mimicking her movements and asking her to describe how she felt about herself.

When seated again, “C” moved on to ask Komiko how she might act on an average day. “C” asked her to imagine her non-Catholic, non-traditional self going to work, doing the shopping or visiting friends. Komiko imagined herself talking avidly to her more assertive friends about making decisions. She discussed the possibility of having her own place to be herself, and how she might plan meals for herself and arrange everything to her own liking. She thought of having friends stay over for weekends and setting up a study room for her work.

Komiko moved on to consider having the freedom to see a male friend from church that she was interested in, without being under the watch of her parents. After this point she was quiet and “C” asked what she was thinking. Komiko said that her Catholic/traditional side was not happy about this, as she was afraid of becoming involved with someone.

“C” prompted Komiko to imagine how her non-Catholic, non-traditional self might approach this problem. Komiko thought that her non-Catholic self probably wouldn’t get involved unless she thought that the relationship could be serious. When asked what being serious meant, Komiko replied that there would be some sort of verbal agreement with her partner and that she would feel in love. She thought that she might see him on weekends and would consider introducing him to her parents.

“C” asked her how her non-Catholic, non-traditional side would feel at this stage. Komiko thought that she might be quite happy, though her Catholic/traditional side feared that her parents might find out earlier, or might not approve of her choice. As the session was near to finishing, “C” asked Komiko to stop playing the role, suggesting that they may work further on these roles in the next session. Komiko sat quietly for some time, reflecting on her role reversal. “C” expressed her admiration of Komiko’s attempts to explore herself and her conflicts. “C” asked her to give herself some feedback on the session.

Komiko felt that she had further explored her motives for change and her fears of change in further detail. She had come to realise her responsibility for both her assertion and lack of it, and had been surprised at the extent of her desire to take more control of her life. She felt that her assertive side had the strength to be independent, whereas earlier, she didn’t think that she had any inner resources to make changes to her life. She hoped to continue the therapy until she became more decided about the decisions she wanted to make.

“C” validated this progress that Komiko had made and suggested that they might continue the next session by exploring some more of the conflict between her catholic/traditional and non-catholic, non-traditional values and to consider the letter that she was to write to her parents.

End of Session

Some points to consider with Gestalt Therapy include:

The assumption of Gestalt therapy is that individuals are responsible for their own growth and behaviour. It is an experiential approach, designed to help people gain more awareness of what they are doing. Gestalt therapy is an active therapy and clients are expected to take part in their own growth.

Most of the techniques of Gestalt therapy are designed to assist people to more fully experience themselves. The therapist should not force clients to partake in experiments if they don’t want to, but in this instance should explore the client’s resistance to the therapy.

Some of the activities and exercises employed by Gestalt therapists include the following:

- I take responsibility for.this is to help someone accept their own personal responsibility for their feelings, actions and their subsequent consequences. This can be useful if the client is blaming others for their problems. By taking responsibility for their problems, the client may be more empowered to change their thinking, actions, and feelings.

- The dialogue exercise…this is a useful experiment to employ if the person is engaged in a struggle of some kind. The client should carry on a conversation between the two parts of themselves that are in conflict. This exercise can help the client to better understand the motives of each side and clarify their experiences.

- I have a secret…this is a technique for exploring secrets and imagining revealing them to others. It allows the client to think about the reactions of others to their secrets and understand the reasons for keeping these secrets. Writing a letter to someone (but not sending it!) may be a way to explore secrets or taboo subjects.

- Reversal technique…if a client is attempting to deny a side of themselves, this technique may be used to help explore the side they wish to cover up. By experiencing themselves as this side, may help them to explore what they are failing to deal with.

- The Rehearsal technique…we rehearse many things inwardly, when we imagine how situations will be. The technique is to rehearse these out-loud by acting out all the things that you might be experiencing inwardly. You might do this when facing something you are afraid of, such as applying for a job, or asking someone for a date.

- The exaggeration exercise…this is designed to draw attention to our body language. The client is to deliberately exaggerate a body movement that they do often, such as frowning or smiling when they feel hurt. The exercise aims to make people more aware of their feelings when they use these particular body movements and gestures.

These are just some of the experiments used in Gestalt therapy. You may know of others. Perhaps you might like to think about how you might use these experiments with someone like Komiko.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Subscribe to our newsletter

You’ll regularly receive powerful strategies for personal development, tips to improve the growth of your counselling practice, the latest industry news, and much more.

Keyword search

AIPC specialises in providing high quality counselling and community services courses, with a particular focus on highly supported external education. AIPC is the largest provider of counselling courses in the Australia, with over 27 years specialist experience.

Learn more: www.aipc.net.au

Recent Posts

- Men and Emotions: From Repression to Expression

- Men, Emotions and Alexithymia

- The Fine Art of Compassion

- The Benefits of Intentional Daydreaming

- Solution-focused Techniques in Counselling

Recommended Websites

- Australian Counselling Association

- Life Coaching Institute

Gestalt Therapy Explained: History, Definition and Examples

These terms have become part of the cultural lexicon, yet few know that their roots come from gestalt therapy.

Gestalt therapy is an influential and popular form of therapy that has had an impact on global culture and society. It is an amalgamation of different theories and techniques, compiled and refined over the years by many people, most notably its founder, Fritz Perls.

Although gestalt therapy is often considered a “fringe therapy,” it is applicable in diverse settings, from the clinic to the locker room to the boardroom. Read on for an introduction to this exciting therapy.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will provide you with detailed insight into Positive CBT and give you the tools to apply it in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains:

Gestalt therapy defined, a brief history: the 3 founders of gestalt therapy, 4 key concepts and principles, the empty chair technique, examples of gestalt therapy, criticisms and limitations, 3 books on the topic, a take-home message.

Gestalt therapy is a bulky concept to define. Let’s start with a definition by Charles Bowman (1998, p. 106), a gestalt therapy scholar and practitioner. We’ll present the full definition and then break down its parts:

Gestalt therapy is a process psychotherapy with the goal of improving one’s contact in community and with the environment in general. This goal is accomplished through aware, spontaneous and authentic dialogue between client and therapist. Awareness of differences and similarities [is] encouraged while interruptions to contact are explored in the present therapeutic relationship.

Let’s break it down into three components:

Gestalt therapy is a process psychotherapy with the goal of improving one’s contact in community and with the environment in general . A process psychotherapy is one that focuses on process over discrete events. This means that gestalt therapists are more interested in the process as a whole, rather than individual events or experiences.

This goal is accomplished through aware, spontaneous and authentic dialogue between client and therapist . Gestalt psychotherapists use a relational, here-and-now framework , meaning that they prioritize the current interactions with the client over history and past experience.

And finally: Awareness of differences and similarities [is] encouraged while interruptions to contact are explored in the present therapeutic relationship . Gestalt therapy draws upon dialectical thinking and polarization to help the client achieve balance, equilibrium, contact, and health. We will explore these concepts in greater depth later in this post.

Gestalt therapy borrows heavily from psychoanalysis , Gestalt psychology, existential philosophy, zen Buddhism, Taoism, and more (Bowman, 2005). It is an amalgamation of different theoretical ideas, packaged for delivery to patients using the traditional psychoanalytic therapy situation, and also includes elements from more fringe elements of psychology, such as psychodrama and role-playing .

It is tempting to buy into the “great man theory” of gestalt therapy and give all of the credit to Fritz Perls; however, the story is more nuanced than this (Bowman, 2005). Gestalt therapy is the result of many people’s contributions. Since this is a brief article, we will focus on three founders: Fritz Perls, Laura Perls, and Paul Goodman.

Gestalt therapy originated in Germany in the 1930s. Fritz and Laura Perls were psychoanalysts in Frankfurt and Berlin. The Perlses’ ideas differed from Freud’s so radically that they broke off and formed their own discipline.

In 1933 they fled Nazi Germany and moved to South Africa, where they formulated much of gestalt therapy. They eventually moved to New York and wrote the book on gestalt therapy with the anarchist writer and gestalt therapist Paul Goodman (Wulf, 1996).

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to find new pathways to reduce suffering and more effectively cope with life stressors.

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

‘Whole’ + Health + Awareness + Responsibility:

The German word gestalt has no perfect English translation, but a close approximation is “whole.”

Gestalt therapy is based on gestalt psychology, a discipline of experimental psychology founded in Germany in 1912. Gestalt psychologists argued that human beings perceive entire patterns or configurations, not merely individual components.

This is why when we see a group of dots arranged as a triangle, we see a triangle instead of random dots. Our brains organize information into complete configurations, or gestalts (O’Leary, 2013).

Additionally, the individual is thought of as being involved in a constant construction of gestalts, organizing and reorganizing their experience, searching for patterns and a feeling of wholeness. Gestalt therapy associates feeling whole with feeling alive and connected to one’s own unique experience of existence.

Gestalt therapists apply this philosophy of wholeness to their clients. They believe that a human being cannot be understood by generalizing one part of the self to understand the whole person (O’Leary, 2013). For example, the client cannot be understood solely by their diagnosis, or by one interaction, but must be considered the total of all they are.

To understand what it means to be healthy in gestalt therapy, we must first understand the ideas of figure and ground. To illustrate, let’s use an image called the Rubin Vase.

There is a black outline of a vase on the screen, and at first, this is all the viewer notices, but after a moment, the viewer’s attention shifts and they notice the two faces outlined in the white part of the screen, one on either side of the vase.

In the first perception, the black vase is called the figure, and the white faces are called the ground. But the viewer can shift their attention, and through this act, the figure and ground switch, with the white faces becoming the figure, and the black vase the ground.

Gestalt therapists apply this perceptual phenomenon to human experience. Going through the world, we are engaged in a constant process of differentiating figures and grounds. The figure is whatever we are paying attention to, while the ground is whatever is happening in the background. Healthy functioning is the ability to attend flexibly to the figure that is most important at the time (O’Leary, 2013).

Gestalt therapy sees healthy living is a series of creative adjustments (Latner, 1973, p. 54). This means adjusting one’s behavior, naturally and flexibly, to the figure in awareness.

Here is another example of this process: As I am writing, I realize that my lips are dry and my mouth is parched. I get up, pour a glass of water, and then return to my writing. In response to my feeling of thirst, I shift my frame of awareness from my writing, to drinking water, and then back to my writing. The act of drinking water, satisfying my thirst, completes the gestalt, and I am free to return to my work.

In contrast, unhealthy living results when one’s attention flits from one figure to the other without ever achieving wholeness.

An easy example of this can be seen through our relationships with our phones. If we are working on something important and our phone rings, we can make a decision to ignore it for the moment, finish our work, and then call the person back later. If there is a deadline for our project, this may be the healthy choice. But if we allow our attention to be divided each time our phone rings, we may never finish our project.

Healthy living requires the individual to attend flexibly and intentionally to the most crucial figure in their awareness.

3. Awareness

Although we cannot help but live in the present, it is clear to anyone living that we can direct our attention away from it. Gestalt therapists prioritize present moment awareness and the notion that paying attention to the events unfolding in the here-and-now is the way to achieve healthy living.

Awareness allows for the figure/ground differentiation process to work naturally, helping us form gestalts, satisfy our needs, and make sense of our experience (Latner, 1973, p. 72). Awareness is both the goal and the methodology of gestalt therapy (O’Leary, 2013).

Therapists use what is present in the here-and-now, including actions, posture, gesticulations, tone of voice, and how the client relates to them, to inform their work (O’Leary, 2013). The past is thought of as significant insofar as it exists in the present (O’Leary, 2013).

Gestalt therapists focus on helping their clients restore their natural awareness of the present moment by focusing on the here-and-now in the therapy room. Experiences and feelings that have not been fully processed in the past are revisited and worked through in the present, such as with the empty chair technique, explored later in this post.

4. Responsibility

In gestalt therapy, there are two ways of thinking about responsibility. According to Latner (1973, p. 70), we are responsible when we are “ aware of what is happening to us ” and when we “ own up to acts, impulses, and feelings. ” Gestalt therapists help their clients take both kinds of personal responsibility.

When therapy begins, clients do not internalize feelings, emotions, or problems, often externalizing and shifting responsibility for their actions as the fault or consequence of others (O’Leary, 2013). They may be stuck in the past, ruminating on mistakes or regrets about their actions.

When clients are better able to take responsibility for themselves, they come to realize how much they can do for themselves (O’Leary, 2013).

To do this, clients must have an awareness of what is happening to them in the present moment, as well as awareness of their part of the interaction. Increasing this type of awareness, completing past experiences, and encouraging new and flexible behaviors are some of the ways that gestalt therapists help their clients take personal responsibility.

Things that are in our awareness but incomplete are called “ unfinished business .” Because of our natural tendency to make gestalts, unfinished business can be a significant drain of energy, as well as a block on future development (O’Leary, 2013).

The most popular and well-known technique in gestalt therapy, the empty chair technique or empty chair dialogue (ECH), is a method of resolving unfinished business in the therapy room.

Unfinished business is often the result of unexpressed emotion, such as not grieving a loss (O’Leary, 2013), and/or unfulfilled needs, such as unaired grievances in a relationship. The client may have chosen to avoid the unfinished business in the moment, deciding not to rock the boat or to preserve the relationship.

After the fact, these unexpressed feelings may lack a suitable outlet or may continue to be avoided because of shame or fear of being vulnerable. Most people tend to avoid these painful feelings instead of doing what is necessary to change (Perls, 1969).

The empty chair technique is a way of bringing unexpressed emotion and unfulfilled needs into the here-and-now. In ECH, the therapist sets up two chairs for the client, one of which is left empty. The client sits in one chair and imagines the significant other with whom they have unfinished business in the empty chair.

The client is then instructed and helped to say what was left unsaid to the imaginary significant other. Sometimes the client switches chairs and speaks to themselves as though they were the significant other. Through this dialogue, the client’s past emotions are brought into the present. They are then processed and worked through with the therapist.

This technique can be done with either an ongoing relationship or a relationship that has ended. The resolution of the work is to help the client shift their self-perception. Clients undergoing ECH may shift from viewing themselves as weak and victimized to a place of greater self-empowerment. They may see the significant other with greater understanding or hold them accountable for harm (Paivio & Greenberg, 1995).

Gestalt therapy is used in a variety of settings, from the clinic to the corporate boardroom (Leahy & Magerman, 2009). Gestalt institutes exist all over the world, and the approach is practiced in inpatient clinics and private practices in individual and group therapy . Because of this variety of applications, it can take many forms.

In 1965 the American Psychological Association filmed a series called “ Three Approaches to Psychotherapy ,” featuring Fritz Perls (gestalt therapy), Carl Rogers ( person-centered therapy ), and Albert Ellis ( rational emotive behavior therapy ), demonstrating their approaches with a patient named Gloria.

To see what gestalt therapy looks like, you can watch this video of Perls working in real time. In the video, Perls describes his approach, works with Gloria for a brief session, and then debriefs the viewer at the end.

Much of the criticism in the literature focuses on Fritz Perls, the larger-than-life founder of gestalt therapy. Perls had a powerful personality and left a deep personal imprint on the therapy that he developed. Indeed, his own limitations may have limited the therapy.

Perls struggled with interpersonal relationships throughout his life. In turn, the therapy he helped create focused on the ideas of separateness, personal responsibility, and self-support as ideal ways of being (Dolliver, 1981).

One criticism of Perls’s work of spreading gestalt therapy to lay audiences is that he focused on specific techniques that he could demonstrate on film or in live demonstrations.

These demonstrations elevated Perls to guru status and also encouraged practitioners to apply his techniques piece-meal, without understanding the underlying theory of gestalt therapy. This had the overall effect of watering down the method as a whole (Janov, 2005).

Another critique is that Perls’s gestalt therapy focused on helping clients to have “honest interactions” with others. In contrast, he maintained a strict focus on the client’s experience, leaving himself out of the room by avoiding personal questions, turning them back on the client (Dolliver, 1981).

Recent gestalt therapists have revised this aspect, bringing more of themselves into the room and answering their clients’ questions when there could be therapeutic value in doing so.

Perls also emphasized “total experiencing,” yet he de-emphasized the client’s past and kept the focus of the work strictly on the present. He also emphasized “ living as one truly is ,” but in the room, he relied upon reenactment and role-play, which he strictly controlled (Janov, 2005).

Gestalt therapy promotes a specific way of living, and therapists need to be mindful of whether encouraging these behaviors and values in their client is actually in their best interest. By adopting an explicit focus on helping clients “ become who they truly are ,” Perls denied his part in shaping what parts of themselves clients felt free to express in the therapy (Dolliver, 1981).

Gestalt therapists have spent a long time living in Perls’s shadow. New therapists would be better served by learning the theory and practicing without trying to imitate Perls’s style, pushing forward and altering the therapy to make it a better fit for their methods and the needs of their clients.

To practice gestalt therapy effectively and cohesively, rather than as a disconnected set of techniques and quick fixes, it is crucial to have a good understanding of the underlying theory as well as the historical antecedents that it is based on (Bowman, 2005).

17 Science-Based Ways To Apply Positive CBT

These 17 Positive CBT & Cognitive Therapy Exercises [PDF] include our top-rated, ready-made templates for helping others develop more helpful thoughts and behaviors in response to challenges, while broadening the scope of traditional CBT.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

These three books discuss Gestalt Therapy more in-depth.

1. Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality – Fritz Perls, Ralph Hefferline, and Paul Goodman

This book, written in 1951, is the original textbook describing gestalt theory and practice. If you are interested in going to the source before examining a more modern perspective, this is the book for you.

Available on Amazon .

2. The Gestalt Therapy Book – Joel Latner

If you are interested in a brief overview of gestalt therapy, as well as a snapshot of the field in the 1970s, this book is a good choice.

3. Buddhist Psychology & Gestalt Therapy Integrated: Psychotherapy for the 21st Century – Eva Gold and Steve Zahm

For those interested in the intersection between Buddhism and the gestalt technique, this book will be of particular interest.

Related: 16 Best Therapy Books to Read for Therapists

Gestalt therapy is an exciting and versatile therapy that has evolved over the years. There is a dynamic history behind this therapy, and it should not be discounted by practitioners, coaches, or therapists who are deciding upon their orientation.

Gestalt psychology also has appeal to laypeople who find the gestalt way of life to be in line with their values.

When learning about gestalt therapy, it is essential to maintain a focus on the underlying theory, moving past the charisma of its founder, Fritz Perls. Perls’s work is instructive and vital to understanding the rise of gestalt therapy.

If you are interested in practicing gestalt therapy, take the time to learn the story and the theory, and then make it your own.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. For more information, don’t forget to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free .

- Bowman, C. (1998). Definitions of gestalt therapy: Finding common ground. Gestalt Review , 2 (2), 97–107.

- Bowman, C. E. (2005). The history and development of gestalt therapy. In A. L. Woldt & S. M. Toman (Eds.), Gestalt therapy: History, theory, and practice (pp. 3–20). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dolliver, R. H. (1981). Some limitations in Perls’ gestalt therapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice , 18 (1), 38–45.

- Gold, E., & Zahm, S. (2018). Buddhist psychology and gestalt therapy integrated: Psychotherapy for the 21st century . Metta Press.

- Janov, A. (2005). Grand delusions: Psychotherapies without feeling. Retrieved from http://primaltherapy.com/GrandDelusions/GD12.htm

- Latner, J. (1973). The Gestalt therapy book: A holistic guide to the theory, principles, and techniques of Gestalt therapy developed by Frederick S. Perls and others. New York, NY: Julian Press.

- Leahy, M., & Magerman, M. (2009). Awareness, immediacy, and intimacy: The experience of coaching as heard in the voices of Gestalt coaches and their clients. International Gestalt Journal , 32 (1), 81–144.

- O’Leary, E. (2013). Key concepts of gestalt therapy and processing. In E. O’Leary (Ed.), Gestalt therapy around the world (pp. 15–36). Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Paivio, S. C., & Greenberg, L. S. (1995). Resolving “unfinished business”: Efficacy of experiential therapy using empty-chair dialogue. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 63 (3), 419–425.

- Perls, F. S. (1969). Gestalt therapy verbatim . Lafayette, CA: Real People Press.

- Perls. F. S., Hefferline, R., & Goodman, P. (1951). Gestalt therapy: Excitement and growth in the human personality . New York, NY: Julian Press.

- Wulf, R. (1996). The historical roots of gestalt therapy. Gestalt Dialogue: Newsletter for the Integrative Gestalt Centre. Christchurch, NZ.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Thank you for a hugely informative article. Helped me to draw together the different strands of Gestalt in a coherent way.

As a student of counseling, I saw Perls’ video and was totally turned off to the technique. Then I got a practice client who was emotionally shut down and agonized over the various techniques to use that were in my textbook. I realized the client’s mom (the “figure”) was in the room with us and decided to try Gestalt despite my misgivings. It was incredibly fruitful, driving me to always be in the present with the client and always examine my own blocks to being totally present in the moment with the client. I veered into what appeared to be other methodologies as necessary such as somatic, mindfulness, even CBT, but found that those methodologies were actually already part of Gestalt as I learned more about it. It’s a very flexible and powerful container for addressing a client’s needs and keeping the therapist honest with themselves and growing professionally.

I really liked your summary and references, they helped me explain what I’m thinking about Gestalt to others.

How to answer the question “how are you? ” in gestalt

Obviously the client can answer any way they choose, but seeing as Gestalt Therapy focuses on present-moment experience, they might be encouraged to respond openly and honestly with reference to how they presently feel in their body, thoughts running through their head, etc. These are just a couple examples 🙂

Hope that answers your question.

– Nicole | Community Manager

Great and informative article and the video was very helpful in putting this together.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Holistic Therapy: Healing Mind, Body, and Spirit

The term “holistic” in health care can be dated back to Hippocrates over 2,500 years ago (Relman, 1979). Hippocrates highlighted the importance of viewing individuals [...]

Trauma-Informed Therapy Explained (& 9 Techniques)

Trauma varies significantly in its effect on individuals. While some people may quickly recover from an adverse event, others might find their coping abilities profoundly [...]

Recreational Therapy Explained: 6 Degrees & Programs

Let’s face it, on a scale of hot or not, attending therapy doesn’t make any client jump with excitement. But what if that can be [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (48)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (27)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (36)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (49)

- Resilience & Coping (35)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

In and Out of Sync: an Example of Gestalt Therapy

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 22 December 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 75–88, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ryszard Praszkier ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5135-5210 1 &

- Andrzej Nowak 1

8572 Accesses

2 Citations

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

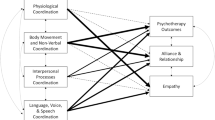

This article emphasizes the importance of synchronization in changing patients’ dysfunctional patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to functional ones. Furthermore, the concept of synchronization in psychotherapy is delineated herein, showing its feasibility through the free energy principle. Most sync-oriented publications focus on the therapist-patient relationship. In contrast, this article is focusing on the therapeutic process, especially by analyzing how dysfunctional units—both in an individual’s mind, as well as in social relationships—assemble in synchrony and how psychotherapy helps to disassemble and replace them with functional units. As an example, Gestalt psychology and Gestalt psychotherapy are demonstrated through the lenses of synchronization, supported by diverse case studies. Finally, it is concluded that synchronization is opening a gateway to understanding the change dynamics in psychotherapy and, as such, is worth further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Interpersonal Coordination Dynamics in Psychotherapy: A Systematic Review

Travis J. Wiltshire, Johanne Stege Philipsen, … Sune Vork Steffensen

- Synchronization

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is growing interest in synchronization in relation to the therapeutic process (Koole & Tschacher, 2016 ; Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2011 ; Reich et al., 2014 ; Tschacher et al., 2014 ; Yokotani et al., 2020 ). This is supported by development in the hard- and software monitoring of synchronization in therapy. Footnote 1 However, most publications focus on the therapist-patient relationship. In contrast, this article advances the field by focusing on the therapeutic process, especially by analyzing how dysfunctional units—both in an individual’s mind, as well as in social relationships—assemble in synchrony and how psychotherapy helps to disassemble and replace them with functional units.

Synchronization is the process of the coordination of events in order to operate a system in unison. Elements can achieve selective (cluster) synchronization if they simultaneously become salient in some manner, and this mechanism is likely used to synchronize elements that are instrumental to the achievement of a goal (Nowak et al., 2020 , p. 18).

Synchronization can be described using two different perspectives: at the level of system dynamics and at the level of inter-influence among system elements. Both perspectives represent the binding of dynamics, i.e., the dynamics of one element being dependent on the dynamics of another element (Nowak et al., 2020 , p. 6).

In relation to therapy, incompatible elements may be neglected, disregarded, or repressed, or two conflicting mental structures may be created. In both cases, dysfunctional units are assembled: in the first case, leading to the emergence of aggravating unfinished business—a term used in Gestalt therapy (see: Greenberg & Malcolm, 2002 ; O'Leary & Nieuwstraten 1999 ); in the second case, the persistence of conflicted mental structures in time may lead to neurotic stress (e.g., Andrews et al., 1993 ).

To deal effectively with these problems, it is necessary to disassemble dysfunctional units, thereby setting the stage for a reconfiguration that is more adaptive.

Functional and Dysfunctional Units

A functional unit refers to allowing for the creation of temporary structures in unique configurations that are assembled to perform a specific task (Köhler, 1970 ; Mandler, 1967 ; Nowak et al., 2020 ; Tulving, 1968 ).

Nowak et al. ( 2020 ) proposed that the functioning of a system is made possible because of intermittent synchronization, in which sets of elements are assembled and disassembled over time, as demanded by the present function. The elements comprising a substructure are assembled to create a functional unit, which can be observed at different levels of psychological and social reality, from the human brain to minds, groups, and societies. In this vein, to deal effectively with human problems, it is necessary to disassemble dysfunctional patterns, thus setting the stage for a reconfiguration that is more adaptive.

Free Energy Principle

Energy is perceived as an important issue in psychotherapy (e.g., Feinstein, 2008 ; Gallo, 2004 ). There are three kinds of human energy mentioned in the literature, as follows:

Energy being a result of metabolism. For example, studies have found that mental effort can be measured in terms of increased metabolism in the brain (Benton et al., 1996 ; Fairclough & Houston, 2004 ; Gailliot et al., 2007 ). Brain metabolism, measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging or positron emission tomography, is a physical correlate of mental activity.

Libidinal energy, primarily mentioned in psychoanalysis as psychic energy produced by the libido (Barratt, 2015 ; Jung, 1913 ). For example, Sigmund Freud ( 1900 ) used the term “libidinal energy economy” for the dynamic contradictoriness of repression barriers.

The understanding of energy in this article relates to the harmony of a system associated with synchronization.

Synchronization is a natural state in which self-organizing systems strive for a state of minimum energy, according to the free energy principle; an emergent property of this process is synchronization (Ashby, 1962 ; Friston, 2010 ; Friston et al., 2006 ). This relates to all biological systems, including the brain, individuals, and families. It is instrumental for a child’s successful development (Feldman, 2007 ; Harrist & Waugh, 2002 ) and an adolescent’s successful social adaptation (Barber et al., 2001 ). Some authors posit that synchrony is an emergent property of free energy minimization and, in lieu of this, synchronization is a state of a “resting brain” (Palacios et al., 2019 ).

In groups, synchronization increases the tendency to cooperate and to maintain positive relationships (Tschacher et al., 2014 ; Wiltermuth & Heath, 2009 ), while it decreases the occurrence of conflicts and generates efficiency of task groups (Barsade, 2002 ). On an individual level, individuals tend to like and to have more compassion for those with whom they are synchronized (Hove & Risen, 2009 ; Moritz, 2017 ; Valdesolo & DeSteno, 2011 ), and are also more eager to cooperate with them (Lang et al., 2017 ; Wiltermuth & Heath, 2009 ).

The state of synchronization may be temporary, depending on its usefulness. The elements of a system assemble into functional synchronized units and then disassemble when no longer serviceable (Nowak et al., 2020 ; Ramseyer, 2011 ). This property is especially important when the temporary synchronized unit is dysfunctional, leading to some impairments, e.g., on a neuronal level, such as in epilepsy (Jiruska et al., 2013 ; Lehnertz et al., 2009 ), or on an individual level, e.g., obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) (Özçoban et al., 2014 ; Tass et al., 2003 ). On a family level, some sequences of mutually reinforced subsequent actions/reactions may occur, thereby forming destructive patterns (Nowak et al., 2020 ; Praszkier, 1992 ).

The Psychotherapeutic Process and Synchronization

Psychotherapy is the use of psychological methods to help a person change and overcome problems in desired ways. It is a collaborative treatment based on the relationship between an individual and a psychologist, grounded in dialog and the provision of a supportive environment that allows the individual to talk openly with someone who is objective, neutral, and nonjudgmental, with the aim of working together to identify and change the thought and behavior patterns that keep the patient from feeling good (Hamlyn, 2007 ; Wampold, 2019 ).

There have been some studies related to synchronization in psychotherapy, though mostly focused on the positive impact of synchronization on the psychotherapist-patient relationship and the way it influences the outcomes of psychotherapy (Koole & Tschacher, 2016 ; Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2008 , 2011 ; Tschacher et al., 1998 , 2014 ). To date, there have been no studies on the change dynamics in relation to synchronization.

Filling this gap, and using the premise of the synchronization concept, the psychotherapeutic process may be seen as focused on disassembling dysfunctional units and thus creating space for the emergence of functional ones.

Some problems (e.g., neuroses) appear when elements assembled on a lower level (e.g., memories from past experiences) create, at a higher level of awareness, new dysfunctional units. These units usually influence an individual’s cognitive structure, impacting one’s ability to understand oneself, to attribute others’ behaviors, and to perceive the relationships between oneself and others.

Perhaps, the best illustration of psychotherapy as a process of disassembling dysfunctional units and providing space for replacing them with new emergent structures in one’s cognition, emotions, and awareness is Gestalt theory and Gestalt therapy.

Gestalt Psychology and Gestalt Psychotherapy

Presented below are the basic concepts of Gestalt psychology and field theory, followed by a delineation of the application of synchronization to Gestalt theory, concluded with a characterization of the principles of Gestalt therapy.

Gestalt Psychology and Field Theory

Kurt Lewin’s original conception of field theory (Lewin, 2004 ) was based on Gestalt psychology (Burnes & Cooke, 2012 ). The basic premise is seeing the situation as a whole (Lewin, 2004 ); in other words, perceiving functional systems instead of single elements. There are several related principles (Deutsch, 1954 ; Parlett & Lee, 2005 ), as follows:

Organization and retroflection: Even small, seemingly irrelevant movements, such as tapping one’s finger on the table, may be significant as a symptom of one or more important mechanisms, e.g., the retroflection of energy. Retroflection occurs when a person turns his/her stored up, mobilized energy back upon himself instead of out into the environment, and tapping may be a signal of a suppressed need for the discharge of retroflected energy.

Contemporaneity: The present time reflects both the past (as it was remembered) and the anticipated future.

Singularity: Each situation is unique and could be seen as a “new opening.”

Changing process: Nothing is fixed and static in an absolute way. For each individual, the field is newly constructed moment by moment; individuals cannot have an identical experience twice.

Possible relevance: No part of the total field can be excluded in advance as irrelevant. Everything in the field is part of the total organization and is potentially meaningful.

The figure–ground construct: In Gestalt psychology, an important concept is the figure–ground theory, which refers to the tendency of a system to simplify a scene into the main object being observed (i.e., the figure) and to educe it from everything else that forms the background (Cherry, 2016 ; Wertheimer & Riezler, 1944 ). When a need appears (e.g., hunger), all related images of food, smells, etc., become figures, and the rest of the reality remains in the background. When hunger is appeased, a new functional unit appears, which is a new Gestalt (and it is Gestalt psychology that first introduced the emergence of functional units; see: Nowak et al., 2020 ), such as admiring the beauty of nature or business challenges, and everything else moves into the background.

Gestalt Theory and Synchronization

This delineated process is synchronous: Gestalts emerge, and after gratification has been removed, space is created for new functional Gestalts, thus forming new functional units. However, in some cases, the existing Gestalt is not fulfilled or gratified, and as such, while new needs become more pressing, it is (semi)moved into the background. The unattained functional unit lingers and retroflects in the background, popping up through some unintended movement (e.g., tapping a finger) or action (e.g., emotions transferred to someone else). This kind of a dysfunctional unit does not integrate and, often unconsciously, shatters synchrony.

An example might be that someone did not tell his father, before he died, that he loved him. This unfulfilled need endures, in the background, throughout the rest of his life, unintentionally influencing various actions. The Gestalt principle of contemporaneity allows the individual to fulfill this need in the present through a dialog with the imagined father sitting on an empty chair (see Gestalt techniques below). In this way, the mental system regains synchrony.

Gestalt Therapy

In Gestalt therapy , the ultimate goal is to achieve a client’s awareness, which includes knowing the environment, taking responsibility for choices, self-knowledge, self-acceptance, and the ability to establish contact with others (Yontef, 1993 ). Awareness is seen here as both the content and the process, both of which progress to deeper levels as the therapy proceeds (Yontef, idem ).

The founder of Gestalt therapy, Fritz Perls, believed that the ultimate goal of psychotherapy is the achievement of a degree of integration that facilitates its own development (Perls, 1992 ). In the language of this article, this means decomposing the dysfunctional configurations in the patient’s awareness and fostering the process of recomposing them into new functional units.

Perls based his approach on the concept of phenomenological experience (Crocker, 1999 ; Latner, 2000 ; Yontef, 1993 ), i.e., on shifting the awareness from interpretations and attributions (i.e., malfunctioning cognitive units) to experiencing the “here and now,” and in this way, decomposing old dysfunctional cognitive units and recomposing them on a new functional level. This process was delineated by Melnick and Nevis ( 2005 ) as follows:

Rather than talking about a critical person (e.g., a parent) from a client’s life, a Gestalt therapist might ask him or her to imagine this person in the present (e.g., as if sitting opposite them on an empty chair), or imagining that the therapist is the parent; in both situations, the patient is asked to talk to that person directly in the present.

A Gestalt therapist might notice something about the non-verbal behavior or tone of voice of the client; then, he or she might have the client explore or exaggerate this non-verbal behavior and fully experience how this reverberates in their emotions.

The Gestalt therapist works with process rather than content, i.e., the “how” rather than the “what.”

Similarly, Gestalt therapy principles were seen by Marcus ( 1979 ) as exploring:

Contact, especially the “here and now” contact with the therapist.

Process, i.e., the flow of the “here and now” behaviors, thoughts, and attributions.

Experimentation, e.g., transforming the patient’s verbal account into role-playing.

These principles translate into very specific techniques, which Yontef ( 1993 ) called “patient focusing:”

Stay with it: Whatever you feel, e.g., being sad, just stay with it, try to explore and deepen the feeling, instead of escaping from it.

Enactment: Change descriptive narration into action; instead of talking about someone, talk to this person (e.g., imagining him or her sitting on an empty chair opposite them).

Exaggerate statements or expressions and connect with associated feelings.

Guided fantasy: The patient closes their eyes and imagines metaphorical situations described by the therapist (e.g., “imagine walking up the hill, finding a dark cave; you are entering the cave—what do you feel?” or “You see a door, come close to it, what are your first thoughts?”).

Body techniques—for integrating body and mind.

Paradoxical techniques, e.g., identifying with both sides of the conflict and speaking from both perspectives (e.g., changing between two chairs, each representing one of the opposing parties).

The Gestalt therapist acts as a “field theory agent:” He/she is not detached from the field, but rather is a part of it (Latner, 2000 ; Parlett & Lee, 2005 ), and carries out mutual “investigation” into how the field and its different parts are organized (Clarkson, 2013 ; Lewin, 2004 ; Parlett & Lee, 2005 ). In lieu of this, the therapist analyzes the existing (“here and now”) functional or nonadaptive units (e.g. some synchronized maladjusted sequences), creating an enabling environment that fosters the process of dissolving old, dysfunctional mental units and replacing them with new ones, based on the perception of reality (especially in the “here and now”). The following cases show therapists “in action.”

From the dynamical point of view, these techniques lead to disenabling of the dysfunctional emotional units and assembling new and functional ones; and in that way—achieving a higher synchrony level.

Examples of Gestalt-Style Interventions

The below cases are abbreviated accounts. The first two are from the Gestalt workshops of Eric Marcus, M.D. carried out in Warsaw in the late 1970s. The third refers to the co-author’s (Praszkier, 1992 ) professional experience as a psychotherapist.

Ann: Discomfort When Focusing on Oneself

In a group session, Ann decided to present her problem. In preparation, she shifted from her comfortable position to an awkward, forward-leaning posture that required muscle tension to be sustained. When she started to talk about her problem, the Gestalt facilitator stopped her and said, “Please don’t move, and fully experience the position you are currently sitting in.” “How does it feel?” he asked.

“I am tense,” Ann responded. The facilitator asked her to relax back into her previous position. Ann sat back, comfortably supported by the back of the chair.

“How do you feel?” asked the facilitator.

“Relaxed,” said Ann.

“Now please sit back in the position you took when you started to present your problem.” Ann again leaned forward to the tense position. The facilitator said, “Ann, please say: ‘When I speak about myself, I must take an uncomfortable position’.”

The group members held their breath as Ann hesitated. Finally, clearly upset, she said in a low voice, “When I speak about myself, I must take an uncomfortable position.” The therapist then asked Ann to repeat this phrase loudly, “When I focus on myself, I must feel uncomfortable!” He asked whether the statement fit her actual feelings.

Ann cried, while the group members remained in total silence, understanding that this was relieving the discharge of previously suppressed emotions. After a while, the Gestalt therapist asked: “When do you feel similar?” Ann responded that this was actually the issue she wanted to raise at the beginning: That with her peers or among her colleagues at work, she always feels tense and stunned, especially when it is her turn to speak up; it even—or especially—happens when she has something important or interesting to say.

This therapeutic experience of enactment and exaggeration solved her problem, as she realized how much she tortured herself whenever focusing on herself or her own ideas. “I will always remember this experience and how I believed that when I speak about myself I must feel uncomfortable.”

The therapist commented that this new experience gave Ann good momentum. At one of the next sessions, Ann volunteered to continue. The therapist asked about her first remembered experience of feeling similar, and this brought back childhood memories. Again, the method was to speak directly to the key people in her life, imagining them sitting across from her—and, in turn, stepping into their shoes to respond to “little Ann.” This inner and often suppressed dialog was enacted at a high-energy level.

In this way, the lingering unfinished and unclosed Gestalts were closed in the “here and now,” in accordance with the contemporaneity principle.

John: Intellectual Shield Covering Anger

John was the most intellectual group member. He talked slowly, weighed his words, and took an unemotional stance. In this way, he was respected, though not very much liked.

During group sessions, John was the last to discuss his problems. When he did speak, he focused on the furthest corner of the ceiling and spoke slowly and without emotion. It came across as a very studied and intellectual account of how he is honest in relationships with people and how this honesty makes others keep him at a distance. At one point, the facilitator interrupted him, “Have you noticed that whenever you talk, you find a spot on the ceiling to talk to? This must be an important place to attract your attention. What is this spot telling you?”.

John looked unnerved and flustered, hesitant to respond. The facilitator continued, “Could you imagine being this spot and talking to John?” John stared at the therapist and then back at the ceiling. Finally, a bit jittery, he started to talk: “I am a neutral spot, I keep your attention so you don’t become emotional; I am your resource to stay balanced.” The facilitator asked John to reply to what the spot on the ceiling told him. John looked even more agitated. “Thank you for being my guardian. Without you…. without you…. I would become furious,” he said in a faltering voice, his hands and legs shaking slightly.

He looked at the therapist, who said, “John, try to be furious then; see what it looks like. Take a pillow and hit the sofa.” John tried. “Harder, John, let all of that anger out of you, and shout out whatever comes to your mind.”

John became furious, hitting the sofa as hard as he could and yelling “I hate you, I hate you.” Finally, he threw the pillow away and, looking a bit confused, sat down. It was the first moment the group saw “the real” John—as per their comments in a feedback session, they witnessed John being natural and being human. Some said that during the lunch break that followed this episode, they wanted to socialize with John, who reacted in a new way, without his usual intellectual shield. After the break, John confirmed that he felt much closer to people.

In one of the next sessions, John came forward, willing to explore where his unwanted anger came from. The therapist asked about his first memories of feeling anger. This apparently raised John’s tension levels. Finally, he said that he remembered being six years old, beset by other children on the playground, especially by the girl he liked the most. At that time, he did not react. He did not even tell his parents, because he was shy to admit that the other children were after him. The therapist asked if there was a specific child he remembered; it was Mary, the girl he actually liked the most. The therapist asked John to imagine Mary sitting on the empty chair in front of him and to talk to her. Through a tense and painful process, John finally opened up and talked to Mary, saying how much he both liked and hated her and that he wanted to hit her in the present moment. The therapist gave John a pillow and prompted him to hit the empty chair and the imaginary Mary. He also told John to speak and shout while hitting the pillow. After this high-energy experience, John became calm and reflective, as well as visibly more relaxed on a physical level.

A Tedious Family

Sessions with this family were prompted by the 16-year-old daughter Juliet’s risk of developing anorexia. In this case, medical support was secured. There were also several preceding individual sessions with the daughter that indicated family communication problems.

During the first few family meetings, the progress gradually slowed to the point that it seemed stuck. The family members communicated in a succinct and formal way, spirited only by Juliet’s problems. Analyzing this case with his colleagues, the therapist noted that there was no real vitality in this family, only routine and tedious patterns. It seemed that the daughter and her younger brother expected more vibrant relationships, and implicitly, that both parents would appreciate such a change as well. In this case, their lack of “fire” was understood as a lack of interest.

The psychotherapist thought that without an occasional burst of joy and “craziness,” relationships usually remain limited to formal patterns, becoming overwhelmingly boring and meaningless. The issue was how to bring into the family some vibrant humor and creativity—a daunting challenge given that “bringing in humor” seemed like an oxymoron (as humor is usually spontaneous). Finally, the idea was to use the Gestalt technique of guided fantasy.

During the next session, the therapist suggested that everybody close their eyes and follow his instructions: “Imagine that your family is sitting at the dinner table. Who sits where? Who says what? Now imagine that the person on your right is doing something really crazy. What is it?”.

There was complete silence. After a while, with their eyes still closed, some of them started to giggle. “Now imagine that the person to your left is doing something really crazy.” The chuckles turned into laughs. The therapist asked the family to open their eyes and to share with one another what they had envisioned. They kept laughing, feeling relaxed and spontaneously talking to one another.

The son imagined their father putting the plate of noodles over his head and the noodles slowly creeping down his face. The father imagined his wife putting her favorite china cat sculpture into a cage. Juliet imagined her brother climbing up onto their wardrobe and loudly reading poems from there (the boy hated poems), and so forth. They could not stop laughing, and continued to share their images. The family left the therapist’s office sharing their ridiculous visions, especially those of the usually formal and humorless father with noodles on his head.

This experience triggered a different communication style at home. The images remained in their memories as “implants,” paving the way to more spontaneous communication. Funny ideas and jokes emerged; they changed their usual patterns, hung out together, went for outdoor treks, etc. This, in a feedback loop, had an influence on Juliet, alleviating her feeling of isolation and lack of acceptance and releasing her tension, thereby eradicating the root causes of her over-fasting.

The curative effects of Gestalt techniques such as enactment, “stay with it,” empty chair dialog, exaggeration, and guided fantasy seem apparent. Ann took her first step by identifying, on the emotional and bodily levels, her previous dysfunctional pattern that merged self-focus with discomfort. The next level of intervention led her to relive her early memories and to explore the circumstances supporting the occurrence of such a conjunction. Her lingering dysfunctional units were dismantled, opening her up to new experiences, i.e., building functional units around self-acceptance and self-reliance.

John was seemingly unwilling to accept the interpretation of him cutting himself off from his emotions and, instead, over-intellectualizing. However, the Gestalt enactment techniques contributed to a non-defensive, emotional way of gaining insight into his process of over-intellectualization that served as a shield, protecting him from his anger, which he was previously hiding from his own cognition. This new insight, together with releasing his emotions in public, gained him attention and was reinforced by positive feedback for being perceived as much more natural and real.

Through the guided fantasy technique, Juliet’s family found a way to change their usual patterns to more vibrant, real, and joyful experiences. The images of family members doing something funny shattered the previous dysfunctional system that was maintaining only formal, a-emotional relationships; also, these images paved the way for a new communication mode that turned into a functional unit, thereby bonding the family.

Previously, the family was paradoxically “bonded” by Juliet’s anorectic problems—the only field where they shared true emotions. The family systems theory indicates that symptoms often play a “positive” role by providing a platform for vibrant communication and, in lieu of this, offering protection from other threats, e.g., family disintegration (Keeney, 1983 ; Praszkier, 1992 ). The new functional unit re-bonded the family, creating a new way of synchronization.

In all those cases, there was demonstrated a process of achieving a new, adaptive synchrony level, through dismantling the dysfunctional emotional and behavioral units and assembling more functional ones.

Fabian Ramseyer and Wolfgang Tschacher from Bern University asserted that synchronization is a pervasive concept relevant to diverse domains in physics, biology, and the social sciences. Are they right in positing that synchrony is also pivotal for psychotherapeutic processes? It seems that it is, considering the growing volume of articles in this field across the last two decades (e.g., Koole & Tschacher, 2016 ; Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2006 ; Reich et al., 2014 ; Yokotani et al., 2020 ).

The premise of synchronization and the assembly and disassembly of dysfunctional units seems cut out for Gestalt therapy: The dysfunctional units of unfinished business (Greenberg & Malcolm, 2002 ; Lubinski & Thompson, 2017 ; O'Leary & Nieuwstraten 1999 ) are being addressed—according to the Gestalt contemporaneity principle—in the present, as they are present in the present.

Other than the Gestalt therapeutic approaches that refer to the essential role of synchronization, e.g., the psychoanalytic concept of separation, individuation has also been analyzed under the premise of synchronization (Moon & Bahn, 2016 ); additionally, family systems therapy has been presented through the lens of synchronization (Nowak et al., 2020 ).

A caveat is that the therapeutic process often is more complicated than in the cases demonstrated in this article. The presented examples were selected as to best portray the issues of synchronization in Gestalt Therapy .

The method used in this article is to delineate the core theoretical concept through case studies. This article is only a first step into deepening our knowledge on the role of synchronization in psychotherapy. The conclusions thus far indicate the value of further study in this direction.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

For example, by motion energy analysis (Ramseyer, 2019 ; Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2011 ).

Andrews, G., Page, A. C., & Neilson, M. (1993). Sending your teenagers away: Controlled stress decreases neurotic vulnerability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50 (7), 585–589. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820190087009

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ashby, W. R. (1962). Principles of the self-organizing system. In H. Von Foerster & G. W. Zopf (Eds.), Principles of Self-Organization: Transactions of the University of Illinois Symposium (pp. 255–278). Pergamon Press.

Google Scholar

Barber, J., Bolitho, F., & Bertrand, L. (2001). Parent-child synchrony and adolescent adjustment. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 18 (1), 5–64. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026673203176

Article Google Scholar

Barsade, S. G. (2002). The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. A Dministrative Science Quarterly, 47 (4), 644–675. https://doi.org/10.2307/3094912

Benton, D., Parker, P. Y., & Donohoe, R. T. (1996). The supply of glucose to the brain and cognitive functioning. Journal of Biosocial Science, 28 (4), 463–479. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021932000022537

Barratt, B. B. (2015). On the mythematic reality of libidinality as a subtle energy system: Notes on vitalism, mechanism, and emergence in psychoanalytic thinking. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 32 (4), 626–644. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034973

Burnes, B., & Cooke, B. (2012). Kurt Lewin’s field theory: A review and re-evaluation. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15 (4), 408–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012.00348.x

Cherry, K. (2016). What is figure-ground perception? Very well. Retrieved 26.10.16 from: https://www.verywell.com/what-is-figure-ground-perception-2795195 .

Clarkson, P. (2013). Gestalt Counselling in Action . SAGE Publications.

Crocker, S. (1999). A well-lived life; Essays in Gestalt Therapy . Gestalt Press.

Deutsch, M. (1954). Field Theory in Social Psychology. In: Lindzey, G. & Aronson, E. The Handbook of Social Psychology , vol. 1, pp. 412–487. Hoboken, NJ, Wiley.

Fairclough, S. H., & Houston, K. (2004). A metabolic measure of mental effort. Biological Psychology, 66 (2), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2003.10.001