Mr Lupton History

Lessons, resources and more for KS3 and KS4 History

Nazi Germany 16 markers technique

As a class, we have already explored how to write a 16 mark question for the Crime and Punishment paper. However, the technique needed for a Nazi Germany 16 mark question is different as it asks you to evaluate two interpretations .

Today we shall be exploring how to write these questions and will be attempting to write a 16-marker to round off the lesson.

Please use the YouTube video to help you with today’s lesson. You can download the worksheet for today’s lesson below. If you are unable to download the worksheet, please complete the tasks in the yellow boxes.

Interpretations

As you can see from the outline of the Nazi Germany exam below, the 16-marker is the last question (question 3d). It leads on from the interpretations questions. Therefore, it will be asking you how far you agree with one of the interpretations about something in Nazi Germany.

TASK ONE: What are the main differences between the following interpretations? For our first task today, let’s complete an interpretation question that we are already comfortable with: Study interpretations 1 and 2. They give different views about the increased support for the Nazis from 1929-33. What are the main differences between these views? This question will lead us on to the 16-marker question, so it’s good to practice this first.

Interpretation 1 From a history textbook, GCSE Modern World History, B. Walsh, published in 1996. The Nazis won increased support after 1929 due to Hitler. He was a powerful speaker and was years ahead of his time as a communicator. He travelled by plane on a hectic tour of rallies all over Germany. He appeared as a dynamic man of the moment, the leader of a modern party with modern ideas. At the same time, he was able to appear to be the man of the people, someone who knew and understood the people and their problems. Nazi support rocketed.

Interpretation 2 From a history text book, Modern World History, T. Hewitt, J. McCabe and A. Mendum, published in 1999. The Depression was the main reason for increased support for the Nazis. The government was taken by surprise at the speed and extent of the Depression. It also had very few answers as to how to deal with it. The Depression brought out all the weaknesses of the Weimar Republic, which seemed to be incapable of doing anything to end it. It is not surprising that the German people began to listen to parties promising to do something. In particular, they began to look to and support the Nazis.

STRUCTURE: Remember to structure your above answer as the following: Step 1: Identify the main view of interpretation 1 Interpretation 1 suggests that… Step 2: Give evidence from the interpretation that supports this. This is evident as the interpretation states that… Step 3: Identify the main interpretation of interpretation 2 On the other hand, Interpretation 2 suggests that… Step 4: Give evidence from the interpretation that supports this. This is evident as the interpretation states that…

TASK TWO: What knowledge can you link to both interpretations? In Task Three you will be asked to argue how far you agree with one of these interpretations. One key thing to do in this answer is match up the interpretations to your own knowledge. So what own-knowledge can you link up to both interpretations? Complete this as bullet points in a table. CHALLENGE: It’s even better if you can include SPEND in your table (statistics, places, events, names and dates) to act as evidence.

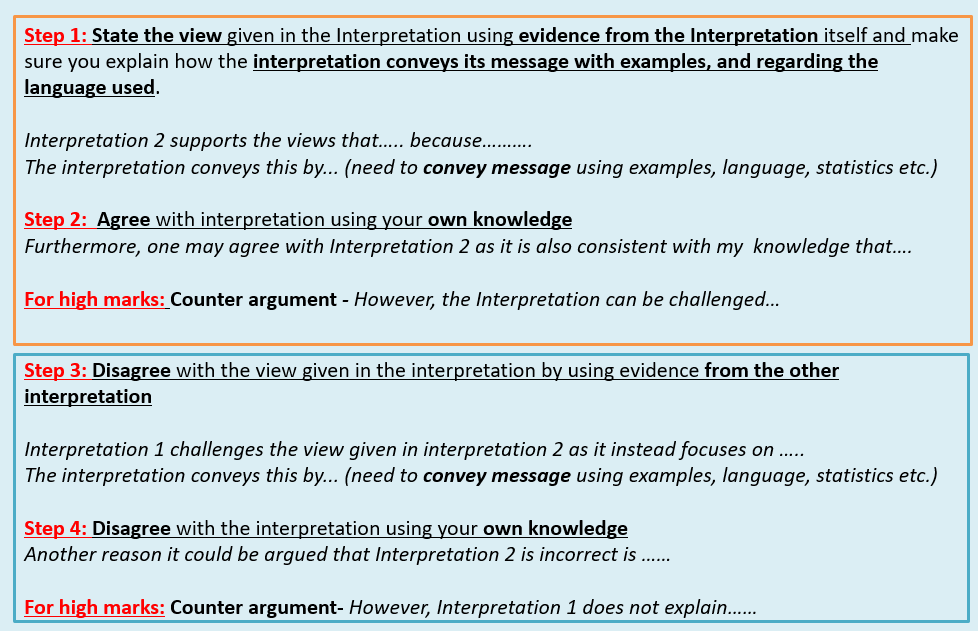

TASK THREE: a 16-marker interpretation question. Look at the interpretations again, and attempt to answer this question: How far do you agree with Interpretation 2 about the reasons for the increased support for the Nazis in the years 1929-1932? Use the structure guide below to help you.

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

How to write a conclusion for a history essay

Every essay needs to end with a concluding paragraph. It is the last paragraph the marker reads, and this will typically be the last paragraph that you write.

What is a ‘concluding paragraph?

The conclusion is the final paragraph of your essay that reminds the reader about the points you have made and how it proves the argument which you stated in your hypothesis .

By the time your marker reads your conclusion, they have read all the evidence you have presented in your body paragraphs . This is your last opportunity to show that you have proven your points.

While your conclusion will talk about the same points you made in your introduction , it should not read exactly the same. Instead, it should state the same information in a more developed form and bring the essay to an end.

In general, you should never use quotes from sources in your conclusion.

Concluding paragraph structure

While the concluding paragraph will normally be shorter than your introductory and body paragraphs , it still has a specific role to fulfil.

A well-written concluding paragraph has the following three-part structure:

- Restate your key points

- Restate your hypothesis

- Concluding sentence

Each element of this structure is explained further, with examples, below:

1. Restate your key points

In one or two sentences, restate each of the topic sentences from your body paragraphs . This is to remind the marker about how you proved your argument.

This information will be similar to your elaboration sentences in your introduction , but will be much briefer.

Since this is a summary of your entire essay’s argument, you will often want to start your conclusion with a phrase to highlight this. For example: “In conclusion”, “In summary”, “To briefly summarise”, or “Overall”.

Example restatements of key points:

Middle Ages (Year 8 Level)

In conclusion, feudal lords had initially spent vast sums of money on elaborate castle construction projects but ceased to do so as a result of the advances in gunpowder technology which rendered stone defences obsolete.

WWI (Year 9 Level)

To briefly summarise, the initially flood of Australian volunteers were encouraged by imperial propaganda but as a result of the stories harsh battlefield experience which filtered back to the home front, enlistment numbers quickly declined.

Civil Rights (Year 10 Level)

In summary, the efforts of important First Nations leaders and activist organisations to spread the idea of indigenous political equality had a significant effect on sway public opinion in favour of a ‘yes’ vote.

Ancient Rome (Year 11/12 Level)

Overall, the Marian military reforms directly changed Roman political campaigns and the role of public opinion in military command assignments across a variety of Roman societal practices.

2. Restate your hypothesis

This is a single sentence that restates the hypothesis from your introductory paragraph .

Don’t simply copy it word-for-word. It should be restated in a different way, but still clearly saying what you have been arguing for the whole of your essay.

Make it clear to your marker that you are clearly restating you argument by beginning this sentence a phrase to highlight this. For example: “Therefore”, “This proves that”, “Consequently”, or “Ultimately”.

Example restated hypotheses:

Therefore, it is clear that while castles were initially intended to dominate infantry-dominated siege scenarios, they were abandoned in favour of financial investment in canon technologies.

This proves that the change in Australian soldiers' morale during World War One was the consequence of the mass slaughter produced by mass-produced weaponry and combat doctrine.

Consequently, the 1967 Referendum considered a public relations success because of the targeted strategies implemented by Charles Perkins, Faith Bandler and the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.

Ultimately, it can be safely argued that Gaius Marius was instrumental in revolutionising the republican political, military and social structures in the 1 st century BC.

3. Concluding sentence

This is the final sentence of your conclusion that provides a final statement about the implications of your arguments for modern understandings of the topic. Alternatively, it could make a statement about what the effect of this historical person or event had on history.

Example concluding sentences:

While these medieval structures fell into disuse centuries ago, they continue to fascinate people to this day.

The implications of the war-weariness produced by these experiences continued to shape opinions about war for the rest of the 20 th century.

Despite this, the Indigenous Peoples had to lobby successive Australian governments for further political equality, which still continues today.

Ancient Rome (Year 11/12 Level)

The impact of these changes effectively prepared the way for other political figures, like Pompey, Julius Caesar and Octavian, who would ultimately transform the Roman republic into an empire.

Putting it all together

Once you have written all three parts of, you should have a completed concluding paragraph. In the examples above, we have shown each part separately. Below you will see the completed paragraphs so that you can appreciate what a conclusion should look like.

Example conclusion paragraphs:

In conclusion, feudal lords had initially spent vast sums of money on elaborate castle construction projects but ceased to do so as a result of the advances in gunpowder technology which rendered stone defences obsolete. Therefore, it is clear that while castles were initially intended to dominate infantry-dominated siege scenarios, they were abandoned in favour of financial investment in canon technologies. While these medieval structures fell into disuse centuries ago, they continue to fascinate people to this day.

To briefly summarise, the initially flood of Australian volunteers were encouraged by imperial propaganda, but as a result of the stories harsh battlefield experience which filtered back to the home front, enlistment numbers quickly declined. This proves that the change in Australian soldiers' morale during World War One was the consequence of the mass slaughter produced by mass-produced weaponry and combat doctrine. The implications of the war-weariness produced by these experiences continued to shape opinions about war for the rest of the 20th century.

In summary, the efforts of important indigenous leaders and activist organisations to spread the idea of indigenous political equality had a significant effect on sway public opinion in favour of a ‘yes’ vote. Consequently, the 1967 Referendum considered a public relations success because of the targeted strategies implemented by Charles Perkins, Faith Bandler and the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Despite this, the Indigenous Peoples had to lobby successive Australian governments for further political equality, which still continues today.

Overall, the Marian military reforms directly changed Roman political campaigns and the role of public opinion in military command assignments across a variety of Roman societal practices. Ultimately, it can be safely argued that Gaius Marius was instrumental in revolutionising the republican political, military and social structures in the 1st century BC. The impact of these changes effectively prepared the way for other political figures, like Pompey, Julius Caesar and Octavian, who would ultimately transform the Roman republic into an empire.

Additional resources

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

- International

- Schools directory

- Resources Jobs Schools directory News Search

GCSE Edexcel History- Elizabethan Englands: 12 and 16marker planned answers

Subject: History

Age range: 14-16

Resource type: Assessment and revision

Last updated

1 November 2019

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

This resource contains the planned full mark answers for 3 possible 12-markers from Elizabethan England and 2 16-markers. These is useful to not only learn as part of revision but also to understand how to write a 12 or 16 mark answer to get top grades.2

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

This resource hasn't been reviewed yet

To ensure quality for our reviews, only customers who have purchased this resource can review it

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

A Level History Essay Structure – A Guide

- Post author By admin

- Post date December 1, 2022

- No Comments on A Level History Essay Structure – A Guide

Getting an A Level History essay structure right is by no means an easy task. In this post we will look at how we can build a structure from which our essay can develop.

Here you can see the most simplified essay structure for tackling A level History essays. All students should be familiar with this structure. We have broken the essay down into an introduction and conclusion as well as 3 separate parts of content. Running through the entire essay at the side is our line of argument. Whilst this may seem fairly simple, many students still fail to adequately follow this structure, when writing essay answers under exam conditions.

The reasons this structure works well is that it enables you to cover 3 different factors of content. These can be aligned 2-1 or 1-2 on either side of the argument. Your essay is now balanced (covering both sides of the argument), whilst at the same time being decisive in terms of your line of argument and judgement. It is also consistent with the amount you can write in the exam time given for (20-25) mark essay questions.

Expanded A level History Essay Structure

Let’s look at an expanded essay structure. Again, we have our introduction and conclusion as well as 3 separate parts of content. Now we can see that we have added whether or not each of our parts of content agrees or disagrees with the question premise. In order to have a balanced essay we can see on this example that; Content 1 agrees, Content 2 disagrees, and Content 3 can go either way. This overall A Level History essay structure ensures a balanced essay that also reaches judgement.

Furthermore, we have now broken down each individual part of Content/Factor. This can be seen as a mini essay in its own right. The Content/Factor is introduced and linked to the question as well as being concluded and linked to the question. Then we write 2 to 3 separate points within the body of the Content/Factor. We have 2 points that agree with the overall argument of this section of content. This strongly backs up our argument.

Then we can also potentially (this doesn’t have to be done always, but when done right creates a more nuanced analysis) add a third point that balances that particular section of content. However, it doesn’t detract from the overall argument of this factor/content. E.g. In the short term ‘point 3’ occurred but of much greater significance was ‘point 1’ and ‘point 2.’

How To Improve Further at A Level History

Pass A Level History – is our sister site, which shows you step by step, how to most effectively answer any A Level History extract, source or essay question. Please click the following link to visit the site and get access to your free preview lesson. www.passalevelhistory.co.uk

Previous and Next Blog Posts

Previous – A Level History Questions – Do and Avoid Guide – passhistoryexams.co.uk/a-level-history-questions-do-and-avoid-guide/

Next – A Level History Coursework Edexcel Guide – passhistoryexams.co.uk/a-level-history-coursework-edexcel/

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Not Your Usual History Lesson: Writing Historical Markers

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

In this lesson, students will develop their understanding of writing and local history by creating their own historical markers. They begin by studying historical markers in their own communities and then draft content for an unmarked historical location.

This lesson was adapted from from a forthcoming book from Pearson by Tim Taylor and Linda Copeland.

Featured Resources

- Sample pictures of historical markers

- Access to resources about local history

- Writing a Historical Marker Assignment & Rubric handouts

From Theory to Practice

Summarizing information is a key skill for students at all grade levels. Repeated practice at summarizing and synthesizing information prepares them for writing assignments in any class as well as for giving presentations, writing research papers, conducting interviews, and keeping journals or logs, for example. NCTE/IRA Standards explicitly refer to conducting research and synthesizing data, emphasizing their importance for good communication practices.

Similarly, researchers describe how summarizing “…links reading and writing and requires higher-level thinking…Summarizing helps students learn more and retain information longer, partly because it requires effort and attention to text” (Dean 19). The more practice students have in younger grades with summarizing, the more successful they will be in various communication contexts later on. The generality of this lesson makes it appropriate for grades 6-8 but may also be tailored to meet standards for grades 9-12.

Further Reading

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

- 6. Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts.

- 7. Students conduct research on issues and interests by generating ideas and questions, and by posing problems. They gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of sources (e.g., print and nonprint texts, artifacts, people) to communicate their discoveries in ways that suit their purpose and audience.

- 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

Materials and Technology

- Projector or interactive whiteboard to display images of historical markers and students’ work

- Computers with internet access for class research (not needed if using books or textual resources)

- Digital cameras (optional)

- Understanding Historical Markers

- Writing a Historical Marker Assignment

- Taking Notes & Summarizing Information

- Interview Notes

- What is Important about Your Research

- Writing a Historical Marker Rubric

This website provides a catalog of historical markers and information. It showcases photographs, inscription transcriptions, marker locations, maps, additional information and commentary, and links to more information. Viewers can add markers to the database and update existing marker pages with new photographs, links, information and commentary.

This marker is listed as an example in Session 1. This site provides a picture of the historic marker in place and enlarges the content so it is readable by viewers of the site.

This site offers historical marker information organized by city and state for easy searching

Stoppingpoints.com provides travelers with historical marker information as well as other points of interest. It is less comprehensive than The Historical Marker Database or the Historical Marker Society of America, but it may afford some different examples.

In his article, author William Lee Anderson III shares information about the history of historical markers in the United States. This article is a good resource for teachers to learn more about historical markers before the lesson. It may also work well as a class reading for the students.

This site provides a list of important questions to ask when considering creating a historical marker.

Preparation

- Research information and prepare any handouts/overheads showing pictures of a variety of historical markers in your town or greater community.

- Research other historic areas or buildings in your town, noting ones that are historical but that do not already have a marker designating them as such. Select 5-10 to use as class writing practice or for students who have difficulty finding topics of their own. Photocopy, print or record website information for sharing with the class.

- Gather books, articles, and other resources describing the history of your town or community. Collect copies of materials for the classroom, make copies available for student use in the school or town library, and/or prepare a bibliography of web sources and post in the classroom or on a class website.

- Secure cameras (digital or camera phone work best) for students to photograph their historical sites or provide pictures for them (optional).

Student Objectives

Students will…

- conduct research on local historical markers in their communities.

- analyze existing historical markers to determine what information is included.

- interview community personnel about historical information and their historical/personal ties to their community.

- write a historical marker by following class guidelines about what constitutes a good historical marker.

Session One

- Begin with a discussion of students’ past vacations or travels. Ask them what kinds of things they have seen along the road when riding in a car to a destination. Make a list on the board or chart paper. The teacher may do this as a whole class discussion or put students into small groups for discussion.

- What are they?

- Where are they found?

- Why would people like/or not like them?

- What purpose do they serve?

- Who creates them?

- Which ones have they seen?

- Are there markers near where they live?

- Which ones do they find the most interesting?

- In this lesson, students will learn how to break down a historical marker to understand its rhetorical situation, noting the following: audience, purpose, language/word choice, location, and credibility. Give students the Understanding Historical Markers handout.

- Location : Where is this marker located? What state? What part of the state? Is the marker near any other landmarks? What is the weather like there? Why might we need to consider the weather?

- Audience : Who is likely to visit this area? Who will read this marker? (For example, age, nationality, education, etc.) Who do you think would not visit this area?

- Purpose : What does the marker want the reader to know? List at least 3 items and then rank them in order from most important to least important. Is there anything you think the marker did not include that it should have?

- Language/Word Choice : What kinds of words does the marker use? Are there any words you did not know or that were confusing to you? Did the marker have words written in a language other than English? Why is this important to think about?

- Credibility : Who created the marker? Does the marker name an author or a group/organization that created or funded it? Why is this important to consider? Were there any errors you noticed on the marker?

Session Two

- The session will begin with a brief review of the information from the Understanding Historical Markers handout.

- Show a picture of a historical marker that is in their town, community, near the school, or so forth. Briefly review it for location, audience, purpose, language/word choice, and credibility (see Understanding Historical Markers handout).

- Ask students to think of other places in their town or community that have markers or that might need a historical marker. Brainstorm this list on the overhead or the board putting information in two columns: Has Marker / Needs Marker. Examples may include an old Victorian house, a park named for a person, a train station, a store in a downtown area, a bridge, a historical neighborhood, a statue, another school, an office building and so forth.

- Each student will pick one location that they may know something about or that they have an interest in. They will conduct research to learn more about that location using different sources, such as websites about local history, books from the school library or others that the teacher has made available in the class. Students will be responsible for taking notes over the information they learned.

- Give students the Writing a Historical Marker Assignment handout and the Taking Notes & Summarizing Information handout and review the assignment. (The teacher will discuss the section on taking notes while discussing interviews in the next session.) Additionally, introduce the rubric and allow time for students to ask questions about the assignment expectations.

- Use the remainder of class for students to begin conducting research using books or online sources and taking notes over these.

Session Three

- The session will begin with each student sharing what location they are researching and one thing they have learned about it so far.

- Share with students that they will also find one person to interview about this place. This does not need to be an expert; it may be a family member or family friend who is familiar with the place. It may also be a neighbor. Help students think about people they know and would feel comfortable asking questions. Students will brainstorm who they might interview about that location (for example: museum curator or volunteer, parent or grandparent, neighbor, other relative, shop owner, home owner, etc.).

- What do you know about this location?

- Is this location important to you? Why or why not?

- Is this location important to other people as well?

- What memories do you have of this location?

- Did anything good, bad, or important happen here?

- (For a theatre) What movies do you remember showing here? How much did a ticket cost? Was it a popular place for young people? How did you get to the theatre? How often could you go?

- (For a train station) Does the station still operate? When did it start and when did it stop running? Did any famous people travel through town and stop this station? How many people usually rode the train? What stops did it make?

- (For a city park) Who or what is the park named after? Why is it named after that person? Did it always look like this? What else did it have? Why did it change? Are there other parks like it in town? What kinds of things did people do here in the past? Why was this a popular place to go?

- Students will then draft both general and specific questions about their location. Their assignment is to conduct their interview and write their notes for the next session. If you wish, interviews may be recorded.

Session Four

- Spend time reviewing the assignment description and then discussing the grading rubric . Help students understand what is important in a good marker and how they can use their information to achieve that.

- Discuss summarizing information. The key to summarizing information is to look at all of the information and discover what a reader must know to understand why that place is important.

- Students will take out their notes from their research and their interviews and review it. Using the What is Important about Your Research handout, they will make a list of the most important information about their location, noting what is important and why.

- Students then draft their historical markers by writing a paragraph for their location, introducing the reader to the place, telling them what is interesting about this location including any names or dates as needed, and telling them what is significant about it for the surrounding area and for history in general.

- Students will turn in a working draft to the teacher at the end of class. The teacher will comment and return to students at the next session.

- For homework, the teacher may assign students to draw a picture of their location or to take a picture of it, depending on access to technology. Students should bring these with them to the next class meeting.

Session Five

- The teacher will return students’ drafts which will have comments about what students did. Share positive elements and offer general suggestions to the class as a whole for revising.

- Students will use the rest of class time to revise their paragraphs: by either writing them out or typing and printing. The goal is for students to have a polished draft of their historical marker that looks professional. The teacher will move around the room helping students.

- Students will include their picture or drawn image of their location with their finished draft for display.

- The teacher may wish to showcase students’ markers around the room or throughout the school. In addition, the teacher may compile students’ historical markers into a class book using ReadWriteThink’s Profile Publisher or Multigenre Mapper , or by taking students’ writing and binding in another form.

- Teachers will grade students using the Writing a Historical Marker rubric . (Teachers may also assign students to finish their assignments and bring them back the next day.)

- Students may give presentations to the class or others in the school about their locations. They may even choose to dress up as a person from the time the location was famous.

- Teachers may assign students to write historical markers for themselves about a place they lived, played, visited, etc. They may write it as though they became famous and people wanted to know about their lives.

- The class may create a website showcasing their historical markers to others in the community or even sharing with a local tourism bureau to highlight as places of interest.

- Students could write more than one historical marker and then create brochures to advertise these for visitors to their community.

- Students might write their markers as though they would be published on the Historical Marker Database website: http://www.hmdb.org/.

- Profile Publisher may be used to help students draft profiles of historical people or places.

Stapleless Book may be useful for students when compiling notes from historical markers in their state or community while planning ideas for their own.

Character Trading Cards may be another way for students to learn about creating short bits of biographical information based on historical figures and then use that to create their own.

Student Assessment / Reflections

- Historical Marker Assignment Rubric

- Professional Library

- Lesson Plans

- Calendar Activities

The old cliche, "A picture is worth a thousand words" is put to the test when students write their own narrative interpretations of events shown in an image.

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Wisconsin has more than 600 historical markers. Here's where they come from

Wisconsin has 609 historical markers across the state, each one marking a person, place or event that is significant to Wisconsin history.

The program started in 1943 , when then-Governor Walter Goodland appointed people to the first historical markers committee. A new committee was formalized in 1950, and a law was passed in 1953 to officially establish the historical markers program. The act established an official seal and design for official markers so they would have a uniform appearance. The first marker under this system was placed in the Peshtigo Fire Cemetery.

In 2021, the Wisconsin Historical Society , which administers the program, received a grant from the William G. Pomeroy Foundation to diversify the stories represented by the markers .

Here's how a site is considered significant enough to receive a historical marker and the process that goes into erecting one.

Who chooses the sites for historical markers?

According to Mallory Hanson, the historical society's statewide services coordinator, it's a community-driven process. She said that any community member or organization can submit a proposal for a historical marker.

"There tend to be more organizations than individuals. Proposals very often come from town or county historical societies, and occasionally from cities as well," Hanson said. "There tend to be spikes during anniversary years, and it also tends to be seasonal with more proposals coming in spring and summer when it makes more sense to think about installation of markers."

Those who wish to apply for a historical marker can apply through the society's website ( wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS50 ). There's a $250 application fee, and although the Wisconsin Historical Society administers the program, they don't pay to erect or maintain the markers. Applicants must agree to pay for the marker and its maintenance, and they must have the permission of the landowner of the proposed marker site.

How is the history verified and the language chosen for the historical markers?

After the applicant submits the form, a review committee at the historical society ensures the site meets its criteria for a significant Wisconsin historical site (see below). If that requirement is met, the applicant's proposed text for the marker is scrutinized. The historical society requires that the text be well-researched and well-documented.

"At that point, the committee will review the narrative and the sources the applicant used to write it," Hanson said. "We also get history consultants to carefully review the text."

Hanson said the review process typically takes about six months.

What is the criteria for determining historically significant topics for markers?

Wisconsin's historical markers must be at sites associated with one of the following criteria :

- Events that have made a significant contribution to "the broad patterns of history"

- People who are no longer living who made a significant contribution to "the broad patterns of history and culture"

- Art or architecture that "embodies the distinctive characteristics of a type, style, period or method of construction or architecture," represents "the work of a master" or "possesses high artistic value"

- Prehistory or archaeology that "yields or is likely to yield information important in prehistory or history"

- Ethnic groups "who have made distinctive and significant contributions to history"

- Represents "significant aspects of the physical or natural history of the earth and its life"

- Legends, popular stories or myths that, "although not verifiable, are significant to history and culture"

Are there topics, stories or people that are underrepresented?

Hanson said the historical society is "always looking to be representing a full and rich history." The society recently conducted a study of the state's historical markers to determine the stories and groups that were "quite popular and some that were not as well recognized," she said.

"Through that study, we identified topics that are eligible for the Pomeroy Foundation grant to diversify our markers program," she added.

They found the underrepresented topics were stories from the history of women, immigrants and refugees, Black people, Hmong people, Latino people, LGBTQ+ people, disabled people, and Tribal Nations and Indigenous people.

The Pomeroy Foundation is also funding the installation of nine new state historical markers to highlight Milwaukee's role in the 1967-68 Fair Housing Movement.

What happens if language on a historical marker needs to be changed to be more accurate?

In September 2023, the historical society replaced a historical marker on Mooningwanekaaning (the Ojibwe name for Madeline Island). The original marker, which was erected in 1961, inaccurately stated that the island was discovered by the French.

According to a news release from the historical society , "the new historical marker, which bears the Ojibwe name for Madeline Island and was developed using input from the Bad River and Red Cliff Ojibwe communities, recognizes the central role of Indigenous peoples in the island's history."

Hanson said that if markers are discovered to have inaccurate details, the society will take steps to consult the owner of the marker in order to correct the narrative.

How can I find Wisconsin's historical markers?

Both a list and map of the Wisconsin's historical markers are available on the Wisconsin Historical Society's website.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Being prepared to write an essay response will help you structure your argument in a way that best answers the question while allowing you to demonstrate your knowledge of the topic, and so gets you the best mark possible! 16-mark questions will provide you with a statement and ask 'How far do you agree?'. First, you should provide a brief ...

An in-depth look into how to effectively answer a 16 mark "how far do you agree?" question - the type which appears on question 5/6 of paper 1 and question 4...

Is that pesky 16 marker getting you down? We're looking at how to get the best mark you can by structuring your essay to fit the exam spec.Get the worksheet ...

(16 marks) In your History GCSE, it is important that you not only have good subject knowledge, but have the skills to apply this knowledge to exam questions. Part of History Elizabeth I.

How do we write answers to 16-mark interpretation questions for GCSE History? This video outlines the structure and writing style needed to answer these ques...

each question as there are marks for that question, i.e. allow at least 16 minutes for an 8 mark answer. Focus on what is being asked (or suggested). • Always refer to the 'source' of the source, e.g. "A cartoon from a German newspaper of September 1939", or "A speech made in Parliament by Winston Churchill". Refer to bias,

This question will lead us on to the 16-marker question, so it's good to practice this first. From a history textbook, GCSE Modern World History, B. Walsh, published in 1996. The Nazis won increased support after 1929 due to Hitler. He was a powerful speaker and was years ahead of his time as a communicator.

1. Background sentences. The first two or three sentences of your introduction should provide a general introduction to the historical topic which your essay is about. This is done so that when you state your hypothesis, your reader understands the specific point you are arguing about. Background sentences explain the important historical ...

This final question requires you to produce a complex argument in response to a statement, using the second-order concepts close second-order concepts In the context of history, second-order ...

File previews. pptx, 794.8 KB. GCSE HISTORY EDEXCEL PLAN FOR 16 MARKERS PAPERS 1& 2. This resource is designed to be made into a booklet to aid students in planning answers to past questions (16 marks). The booklet gives clear instructions to students on what is required in the 16 mark questions on the Edexcel History GCSE exam (Papers 1 and 2).

1. Restate your key points. In one or two sentences, restate each of the topic sentences from your body paragraphs. This is to remind the marker about how you proved your argument. This information will be similar to your elaboration sentences in your introduction, but will be much briefer. Since this is a summary of your entire essay's ...

EV: Educated churchmen who could reas and write, so they assisted in writing out laws and record keeping Enabled Gov. to work effectively EXP: Incluence on the King's decisions + determine the way of the country tow work in their favourKing had to maintain good terms with the Church. Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms ...

Get ready for your exams with this GCSE History (Edexcel) exam preparation guide on Nazi Germany. Arrangements for exam and non-exam assessments for students may be subject to change. Please check ...

File previews. docx, 16.52 KB. This resource contains the planned full mark answers for 3 possible 12-markers from Elizabethan England and 2 16-markers. These is useful to not only learn as part of revision but also to understand how to write a 12 or 16 mark answer to get top grades.2. Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Here you can see the most simplified essay structure for tackling A level History essays. All students should be familiar with this structure. We have broken the essay down into an introduction and conclusion as well as 3 separate parts of content. Running through the entire essay at the side is our line of argument.

Overview. In this lesson, students will develop their understanding of writing and local history by creating their own historical markers. They begin by studying historical markers in their own communities and then draft content for an unmarked historical location. This lesson was adapted from from a forthcoming book from Pearson by Tim Taylor ...

An in-depth look into how to effectively answer a 16 mark "interpretations" question - the type which appears as question 3d of paper 3 of the 9-1 Edexcel GC...

A step-by-step guide to answering the 16 mark How far do you agree with interpretation X question that appears on Paper 3.

Original post by Mona123456. Okay. I've just had a look and definitely do an introduction - just a few lines/small paragraph though. You should outline whether you agree/disagree, to what extent and outline your main arguments briefly. My structure for the essays (16 marks + 4 SPAG questions) was introduction, three points then conclusion.

Watch this video for guidance, tasks, and an example of how to answer the 'Big 16 Marker' question for the AQA GCSE History exam. This has tasks you can foll...

Events that have made a significant contribution to "the broad patterns of history" People who are no longer living who made a significant contribution to "the broad patterns of history and culture"

Essay paragraphs. A Higher History essay must have at least 3 paragraphs but 4 paragraphs is good practice. Overall there is a total of 16 marks available across the essay paragraphs. Try to use ...

This GCSE History video provides a step-by-step approach to answering a 16-mark extended essay exam question (tailored for Edexcel GCSE History).