An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Health Serv Res

- PMC10464255

Quality communication can improve patient-centred health outcomes among older patients: a rapid review

Samer h. sharkiya.

Faculty of Graduate Studies, Arab American University, 13 Zababdeh, P.O Box 240, Jenin, Palestine

Associated Data

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Effective communication is a cornerstone of quality healthcare. Communication helps providers bond with patients, forming therapeutic relationships that benefit patient-centred outcomes. The information exchanged between the provider and patient can help in medical decision-making, such as better self-management. This rapid review investigated the effects of quality and effective communication on patient-centred outcomes among older patients.

Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, and PsycINFO were searched using keywords like “effective communication,“ “elderly,“ and “well-being.“ Studies published between 2000 and 2023 describing or investigating communication strategies between older patients (65 years and above) and providers in various healthcare settings were considered for selection. The quality of selected studies was assessed using the GRADE Tool.

The search strategy yielded seven studies. Five studies were qualitative (two phenomenological study, one ethnography, and two grounded theory studies), one was a cross-sectional observational study, and one was an experimental study. The studies investigated the effects of verbal and nonverbal communication strategies between patients and providers on various patient-centred outcomes, such as patient satisfaction, quality of care, quality of life, and physical and mental health. All the studies reported that various verbal and non-verbal communication strategies positively impacted all patient-centred outcomes.

Although the selected studies supported the positive impact of effective communication with older adults on patient-centred outcomes, they had various methodological setbacks that need to be bridged in the future. Future studies should utilize experimental approaches, generalizable samples, and specific effect size estimates.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-023-09869-8.

Introduction

Excellent communication is critical for all health professionals [ 1 , 2 ]. It affects the quality of healthcare output, impacts the patient’s health and satisfaction, and benefits both patients and providers [ 3 ]. Communication is a critical clinical competence because it establishes trust between providers and patients, creating a therapeutic relationship [ 4 ]. Physician-patient communication plays several functions, including making decisions, exchanging information, improving the physician-patient relationship, managing the patient’s doubts, addressing emotions, and enhancing self-management [ 5 ]. Features of effective or quality communication include involving patients in decisions, allowing patients to speak without interruptions, encouraging a patient to ask questions and answering the questions, using a language that the patient understands, paying attention to the patient and discussing the next steps [ 5 ]. This communication also includes listening, developing a good interpersonal relationship, and making patient-centred management plans.

The quality of patient-physician communication influences various patient-centred outcomes [ 6 ]. In this review, patient-centred outcomes refer to all the outcomes that contribute to the recovery or indicate the recovery of patients, as well as suggest positive experiences with the care process. For instance, effective communication is associated with enhanced patient satisfaction, regulating emotions, and increasing compliance, leading to improved health and better outcomes [ 7 , 8 ]. According to [ 9 ], quality communication enhances patients’ trust in their providers, making patients more satisfied with the treatment. A trusting provider-patient relationship causes individuals to believe they receive better care [ 10 ]. For instance, [ 11 ] report that effective provider-patient communication improves social, somatic, and psychological health. During communication, the provider may enhance positive motivations and involve the individual in treatment decisions. Communication helps patients to acknowledge their illnesses, the associated risks, and the advantages of consistent treatment [ 5 ]. note that mutual communication between providers and patients stimulates or strengthens patients’ perception of control over their health, the knowledge to discern symptoms and self-care and identify changes in their condition. Effective communication leads to improved perceived quality of health care [ 12 ]. report that physician-patient communication influences the perceived quality of healthcare services. All these outcomes that suggest or contribute to patient’s positive experiences or imply a positive recovery journey, such as shorter hospital stays, are considered patient-centred outcomes.

This rapid review aims to review studies that have previously investigated the influence of quality communication on patient-centred outcomes among older adults, such as psychological well-being, quality of health care, emotional well-being, cognitive well-being, individualised care, health status, patient satisfaction, and quality of life. The specific objectives include (a) exploring the strategies used to ensure quality and effective communication with older patients in various healthcare settings, (b) exploring the patient-centred health outcomes reported by previous studies investigating quality communication between providers and older patients, and (c) to link quality communication strategies with older patients to patient-centred health outcomes among older patients.

The primary rationale for conducting this rapid review is that although many studies have examined the relationship between quality communication and various patient-centred outcomes, few studies have used older patients as their participants. It is a significant research gap because older adults have unique communication needs, which, if not considered, their communication with healthcare providers could be ineffective [ 13 ]. For example, older adults experience age-related changes in cognition, perception, and sensation, which can interfere with the communication process [ 14 ]. As a result, more research is needed to the specific quality communication strategies that could improve patient-centred outcomes among older adults. To my knowledge, no systematic review has focused on this topic. Therefore, this is the first rapid review to explore quality communication and its impact on patient-centred health outcomes among older patients in various healthcare settings.

This rapid review’s findings could inform practitioners of the quality communication strategies they can use to improve patient-reported outcomes. Besides, the rapid review evaluates the quality of studies investigating this matter and makes informed recommendations for future research to advance knowledge on this subject.

This rapid review was conducted in conformity with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [ 15 ]. The main difference between a systematic review and a rapid review is that the former strictly conforms to the PRISMA protocol, whereas the latter can miss a few elements of a typical systematic review. A rapid review was suitable because a single reviewer was involved in the study selection process, whereas at least two independent reviewers are recommended in typical systematic reviews [ 16 ].

Eligibility criteria

Table 1 below summarises the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to guide study selection in this rapid review. Also, justification is provided for each inclusion/exclusion criteria. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were drafted based on the target population, the intervention, the outcomes, year of publication, article language, and geographical location. This approach corresponds with the PICO (P – population, I – intervention, C – comparison, and O – outcomes) framework [ 17 ].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Information sources

Four academic databases were searched: PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. These databases were used as sources of information because they publish studies in healthcare sciences on a wide range of topics, including communication and the health outcomes of various interventions. Additionally, Google Scholar was searched to supplement the databases because it indexes academic journal articles in all disciplines, including healthcare. Combining Google Scholar with these databases has been recommended for an optimal search strategy [ 18 ].

Search strategy

Various search terms related to the critical variables of this rapid review, namely quality communication, patient-centred health outcomes, and older patients, were combined using Boolean connectors (AND & OR). Regarding quality communication, some of the keywords that were used include “quality communication,“ “effective communication,“ “doctor-patient communication,“ and “patient-centred communication.“ The keywords that were used for patient-centred outcomes included “well-being,“ “patient satisfaction,“ “quality of care,“ “health status,“ and “quality of life.“ The search terms related to older patients included “nursing home residents,“ “older,“ and “elderly.“ Additionally, since most older patients are institutionalised, search terms like “nursing homes” and “assisted living facilities” were used in the search strategy. Table 2 below presents a sample search strategy executed on PubMed between September 2022 and July 2023. As shown in Table 2 , Mesh terms were used alongside regular keywords. Truncations on the three keywords, namely elderly, nursing homes, and geriatric were used to allow more of their variations to be captured in the search. The use of Mesh terms was only performed on PubMed – Mesh terms are only supported on PubMed and MEDLINE. The rest of the sources of information were searched using the search terms without specifying whether they are Mesh terms or not.

Study selection process

One reviewer (the author) was involved in screening the studies. The reviewer screened each record at least twice for confirmation purposes. Afterwards, an automation tool called ASReview which relies on machine learning to screen textual data was used as a second confirmation [ 19 ]. Research has shown that combining a machine learning tool and a single reviewer can significantly reduce the risk of missing relevant records [ 20 ]. This decision was reached based on previous research that has also demonstrated the good sensitivity of ASReview as a study selection tool in systematic reviews [ 19 ]. The software was trained on the eligibility criteria and the broader context of this study before it was used to screen the studies and confirm the reviewer’s decision. Therefore, if a record were retrieved, the author would screen for its eligibility the first time and confirm it the second time. For the third time confirmation, ASReview was employed. In case of disagreement between the author’s first and second attempts, a third attempt could be made to resolve it. In case of disagreement between the author’s first/second/third attempts and ASReview, a fourth attempt was made to resolve it.

Data collection process

One reviewer (the author) extracted data from the qualifying records. The reviewer could collect data from a given study in the first round, record them, and confirm them in the second round. In case of disagreement between the first and second rounds, the author would extract data from the record for the third time to resolve it. The data points on which data extraction was based include the country where the study was conducted, the study’s research design (if reported), the population and setting of the study, the characteristics of the intervention (communication), and outcomes. Also, the author remained keen to identify ways the studies defined quality or effective communication in the context of older patient care. Regarding the characteristics of the intervention, some of the data sought included the type of communication (e.g., verbal or non-verbal) and the specific communicative strategies, such as touch and active listening.

Regarding outcomes, ‘patient-centred outcomes’ was used as an umbrella term for several variables that relate to the patient’s subjective well-being. Such variables include perceptions of quality of care, quality of life, symptom management, physical health, mental health, health literacy, patient satisfaction, individualised care, and overall well-being, including social processes, self-actualisation, self-esteem, life satisfaction, and psychosocial well-being. If studies reported on the acceptance and usability of communicative strategies, it was also included as a patient-centred outcome because the patient accepts a specific intervention and acknowledges its usability.

Study quality assessment

The study quality assessment in this rapid review entailed the risk of bias and certainty assessments. Risk of bias assessment formed an essential aspect of certainty assessment. The risk of bias in qualitative studies was evaluated using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Qualitative Checklist [ 21 ]; the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) tool was used for randomised studies [ 22 ]; and Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) was used for cross-sectional observational studies [ 23 ]. The Grading for Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) tool was used to assess the certainty of the evidence for all study designs [ 24 ]. The risk of bias in each study design and its corresponding assessment tool was calculated as a percentage of the total points possible. For example, the CASP Qualitative Checklist has ten items; each awarded one point. If a study scored seven out of 10 possible points, its risk of bias would be rated as 70%. The GRADE Tool has five domains, namely risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. The first domain, risk of bias, was populated using the findings of risk of bias assessment using the stated tools. The overall quality of a study was based upon all five domains of the GRADE Tool.

Synthesis methods

Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included in this review. The studies were highly heterogeneous in their research designs hence statistical methods like a meta-analysis synthesis were impossible [ 25 ]. Besides, the studies also had substantial heterogeneity in the study settings (some were conducted in primary care settings, but a majority were conducted in long-term care facilities/nursing homes) and outcomes. The studies measured different outcomes under the umbrella variable of patient-centred outcomes. As such, a narrative synthesis approach was considered the most suitable [ 26 ]. The narrative synthesis guidance by [ 27 ] was used. The first step based on the guidelines should be developing a theoretical model of how the interventions work, why, and for whom.

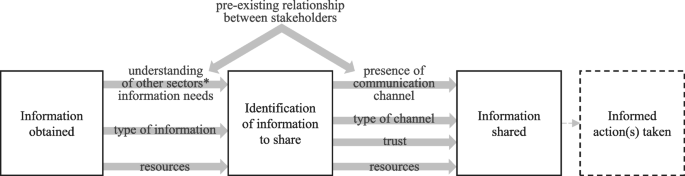

This rapid review’s explanation of how effective or quality communication leads to improved patient-centred outcomes in the introduction section formed the theoretical basis, that is, effective communication facilitates informational exchange between the patient and provider, leading to better decision-making, which positively influences patient outcomes The second step of a narrative synthesis entails organising findings from the included studies to describe patterns across the studies based on the direction of the effect size or effects [ 27 ]. The third step is to explore the relationship in the data by identifying the reasons for the direction of effects or effect size. This rapid review’s reasons were based on the theoretical notions outlined above in this paragraph. The final step is to provide insights into the generalizability of the findings to other populations, which, in the process, further research gaps can be outlined. The results are stated below.

Study selection

After running the search strategy, 40 articles were identified from PubMed, 13 from Google Scholar (records identified from websites (Fig. 1 )), 24 from Scopus, 18 from CINHAL, and 10 from PsycINFO based on the relevance of the titles. It was discovered that 26 were duplicated records between databases and Google Scholar, which reduced the number of identified records to 79. Further, the automation tool (ASReview) marked five records as ineligible based on their title considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria. These articles were excluded because the author confirmed in the fourth round that they were ineligible. After realising they did not focus on older adults, the author excluded three more records. Therefore, 71 records were screened using their abstracts with the help of ASReview (64 records from databases and 7 records from Google Scholar), whereby 44 were excluded (40 records from databases and 4 records from Google Scholar) for various reasons, such as being expert opinions and professional development based on field experiences (e.g., [ 28 ]) and did not have a methodology. The remaining 27 records (24 records from databases and 3 records from Google Scholar) were sought for retrieval, whereby one was excluded because its full text was inaccessible. The remaining 26 articles (23 records from databases and 3 records from Google Scholar) were assessed for eligibility with the help of ASReview, whereby eight records were excluded because they did not report their methodologies (e.g., [ 29 ]), another eight were secondary studies (e.g., [ 30 ]), and three were non-peer-reviewed preprints. Therefore, seven studies met the eligibility criteria for this rapid review.

PRISMA Flowchart summarising the study selection process

Study characteristics

Out of the seven studies, one was an experimental study [ 31 ], one was a cross-sectional observational study [ 32 ], and five were qualitative studies [ 33 – 37 ]. As shown in Table 3 , most of the studies (n = 4) were conducted in the United States. The following countries produced one study each: Australia, Cameroon, the Netherlands, and Hungary. Although all the studies utilised a sample of older patients, the characteristics of the patients differed from one study to another. The studies ranged from primary care settings [ 36 ] and adult medical wards [ 37 ] to long-term care facilities like nursing homes. Apart from [ 36 ], the rest of the studies investigated various non-verbal communication strategies with older adults and their impact on various types of patient-centred outcomes, ranging from health-related outcomes (e.g., smoking cessation) to patient-reported outcomes, such as patient satisfaction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. These outcomes are within the broader umbrella category of patient-centred m outcomes.

Characteristics of included studies

Further, the studies used different types of communicative strategies that can be used to enhance or promote patient-centred outcomes. In this rapid review, they were categorised into seven, namely (a) touching, (b) smiling, (c) gaze, head nod, and eyebrow movement, (d) active listening, (e) close physical distance, and (f) use of visual aids, and (g) telephone communication. Table 4 summarises the various ways in which each study described its interventions.

Description of interventions used in studies

Quality assessment findings

All seven studies were of high quality based on the GRADE Tool-based Assessment. However, [ 31 ] conducted an experimental study, but they did not provide any details indicating whether there was concealment in participant allocation and blinding of participants and outcome assessors. Therefore, it has a high likelihood of risk of bias. However, they scored excellently in the other domains of the GRADE Tool. All five qualitative studies and the cross-sectional observational study also scored excellently in the domains of the GRADE Tool, apart from the imprecision domain where they could not be scored because none of them reported effect sizes (Table 5 ).

Quality assessment using the GRADE Tool

Results of individual studies

[ 31 ] was the only experimental study used in this rapid review investigating the effect of comfort touch on older patients’ perceptions of well-being, self-esteem, health status, social processes, life satisfaction, self-actualisation, and self-responsibility. The authors did not report the effect sizes but indicated that comforting touch had a statistically significant effect on each of the five variables. In summary, the authors suggested that comfort touch, characterised by a handshake or a pat on the shoulders, forearm, or hand, had a statistically significant positive impact on the various patient-centred outcomes reported in their study. For each variable, the authors used three groups, the first and second control groups and the third experimental group. After delivering the intervention, they investigated whether the scores of these variables changed between three-time points in each of the three groups. The first time point was the baseline data collected before intervention was initiated; the second was two weeks after baseline data; and the third was four weeks after baseline data. The authors found that in each of the five variables, the scores remained almost the same in the three-time points for the two control groups, but there were significant improvements in the experimental group (the one that received the intervention). For example, the self-esteem variable was measured using Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale, with the highest attainable score of 40. In the first control group, the score remained 27.00, 27.27, and 27.13 for Time 1 (baseline), Time 2 (after two weeks), and Time 3 (after four weeks), respectively. The same trend was observed in the second control group. However, in the experimental group, the score improved from 29.17 at baseline to 36.00 at Time 2 and 37.47 at Time 3. These findings suggest that comfort touch was highly effective in improving self-esteem among older patients. The same significant improvements were evident for all the other variables (p.184).

While all the other studies focused on nonverbal communication cues, [ 36 ] focused on telephone communication. They aimed to investigate the effect of a tailored intervention on health behaviour change in older adults delivered through telephone communication. Therefore, the primary rationale for selecting this study for review is that it used a specific communicative strategy (telephone) to deliver the intervention, which is the primary purpose of effective communication in most healthcare settings. The older patients used as participants in this study lived with COPD. The nurses trained to administer the intervention made regular phone calls over 12 months. The intervention was delivered to 90 participants. Of these, 65 were invited for interviews at the end of 12 months. One of the most important outcomes relevant to this rapid review is that the participants reported “being listened to by a caring health professional.“ It means that regular telephone communication improved the patient’s perceptions of the quality of care. Other critical patient-centred outcomes that improved due to this intervention include many participants quitting smoking and increased awareness of COPD effects.

[ 34 ] also conducted a qualitative study but needed to specify the specific research design, which was generally non-experimental. The authors used formative evaluation and a participatory approach to develop a communicative intervention for older adults with limited health literacy. In other words, apart from literature reviews, the authors involved the target population in developing a curated story to improve their health literacy. They developed photo and video-based stories by incorporating narrative and social learning theories. The most important finding of this study was that the authors found the developed communicative strategy appealing and understandable. Such observations imply that the participants’ health literacy also likely improved even though the authors did not evaluate it.

Further, using a sample of 155 older patients, [ 32 ] investigated the relationship between the communication characteristics between nursing practitioners and the older patients and patients’ proximal outcomes, namely patient satisfaction and intention to adhere to the NPs’ recommendations, and patients’ long-term outcomes (presenting problems and physical and mental health). The proximal outcomes (satisfaction and intention to adhere) were measured after visits, whereas the long-term outcomes (presenting problems, mental health, and physical health) were measured at four weeks. The communication and relationship components observed include various non-verbal communication strategies: smile, gaze, touch, eyebrow movement, head nod, and handshakes. The authors recorded videos during patient-provider interactions. These communicative strategies were measured using the Roter Interaction Analysis System (independent variable).

In contrast, the other outcomes (dependent variables) outlined above were each measured separately with a validated tool or single-item instruments [ 32 ]. For example, presenting problems were measured with a single-item instrument, whereas the physical and mental health changes at four weeks were measured using the SF-12 Version 2 Health Survey. The authors found that verbal and nonverbal communication strategies focused on providing patients with biomedical and psychosocial information and positive talk characterised by receptivity and trust were associated with better patient outcomes, such as significant improvements in mental and physical health at four weeks. Although the study did not report effect sizes, the findings agree that effective and quality communication can improve patient-centred outcomes like patient satisfaction.

[ 35 ] conducted a qualitative study with focus groups (eight focus groups with a range of three to nine participants) of 15 older adults in a nursing home. The study used an ethnographic qualitative design. The nonverbal communication strategies observed in this study included active listening (including verbal responses) and touching. The authors found that the characteristics of the communication strategies that make communication quality and effective include mutual respect, equity, and addressing conflict. The patients perceived that their nursing aides gave them better-individualised care if their relationship and communication were characterised by mutual respect. Portraying mutual respect includes showing the patients that they are being listened to and heard, which can include calling them by their names and showing signs of active listening. Some residents (older patients) complained that some nursing aides had favouritism, whereby they liked some patients and not others. When such a perception emerges, the patients could perceive the treatment as unjust, compromising individualised care quality. Also, nursing aides must equip themselves with communicative strategies to address conflict rather than avoid it. For example, knowing about the patient’s history can help nursing aides understand their behaviour in the facility, improving prospects of providing better personalised or individualised care.

[ 33 ] also conducted a qualitative study utilising a sample of 17 older adults in nursing homes and assisted living facilities in the United States. They aimed to identify the types and examples of nurse-aide-initiated communication with long-term care residents during mealtime assistance in the context of the residents’ responses. Using a naturalistic approach, the researchers observed communicative interactions between the nurse aides and the residents during mealtime assistance. Videos were recorded and transcribed and analysed using the grounded theory approach. They found that apart from emotional support, nonverbal communication strategies were used by nurse aides to address the residents, initiate and maintain personal conversations, and check-in. Although the authors did not provide statistical proof that these communication strategies improved well-being, their findings can inform future studies.

Finally, [ 37 ] conducted a qualitative, grounded theory study to develop a model for effective non-verbal communication between nurses and older patients. The authors conducted overt observations of patient-nurse interactions using a sample of eight older patients. They found that the nature of nonverbal communication to be employed depends on the context or environment, and certain external factors influence it. The factors influencing nonverbal communication include the nurses’ intrinsic factors, positive views of older adults, awareness of nonverbal communication, and possession of nonverbal communication skills. Patient factors that can also influence the effectiveness of nonverbal communication include positive moods, financial situations, and non-critical medical conditions. The model developed also emphasised that non-verbal communication, if carried out correctly considering context and environment, can lead to positive outcomes, such as increased adherence to providers’ recommendations, improved quality of care, and shorter hospital stays.

Results of syntheses

Four themes emerged from the narrative synthesis: nonverbal communication, verbal communication, communication strategies, and patient-centred outcomes. Table 6 summarises the subthemes that emerged under each theme. They are discussed below.

Nonverbal communication

Nonverbal communication was a critical theme that emerged in several studies. Five out of the seven studies investigated the effectiveness of touch on various patient-centred outcomes [ 31 ]. found that nonverbal communication strategies such as comfort touch, characterised by a handshake or a pat on the shoulders, forearm, or hand, had a statistically significant positive impact on patient-centred outcomes, such as well-being, self-esteem, health status, social processes, life satisfaction, self-actualisation, and self-responsibility [ 31 ]. implemented comfort touch exclusively without combining it with other nonverbal communication strategies. It means that comfort touch on its own can be effective in improving various patient-centred outcomes. As such, it can be hypothesised that if comfort touch is combined with other nonverbal communication strategies, such as active listening, eye gazing, smiling, maintaining a close distance, eyebrow movement, and nodding/shaking of the head can lead to even better results regarding patient-centred outcomes [ 32 , 33 , 35 , 37 ]. [ 35 ] identified active listening and touching as important nonverbal communication strategies that make communication quality and effective [ 33 ]. found that nurse-aide-initiated communication during mealtime assistance using nonverbal communication strategies, such as emotional support, smiling, laughing, touching, eye gazing, shaking hands, head nodding, leaning forward, and a soft tone were crucial in addressing the residents, initiating (and maintaining) personal conversations, and checking in. Finally, [ 37 ] developed a model that emphasised the importance of effective nonverbal communication in forming effective therapeutic relationships, promoting patient satisfaction, and improving the quality of care. An exhaustive list of the nonverbal communication approaches is shown in Table 6 .

In general, most studies, especially the qualitative ones, supported the utilisation of multiple non-verbal communication strategies in a single communicative episode. The studies also implied that it is the responsibility of healthcare providers to initiate and maintain effective nonverbal communication cues, such as those detailed in Table 6 . Additionally, it is important to note that it is only one study [ 31 ] that investigated the effectiveness of comfort touch on patient-centred outcomes. Therefore, the notion implied in qualitative studies that combining various nonverbal strategies could lead to a better improvement in patient-centred outcomes is subject to further empirical investigation. It was noted that there is a lack of empirical studies investigating how the combination of various non-verbal communication techniques or strategies can influence patient-centred outcomes, such as patient satisfaction and perceptions of quality of care.

Verbal communication

Four out of the seven studies implied that verbal communication improved patient-centred outcomes [ 32 , 34 – 36 ]. Effective and quality verbal communication was found to impact patient satisfaction positively [ 32 ], increased awareness of COPD effects [ 36 ], improved health literacy [ 34 ], presented problems [ 32 ], and mental and physical health [ 32 ]. It is worth noting that [ 32 ] used a cross-sectional survey approach and used regression analyses to investigate the relationship between communication and various patient-centred outcomes, such as patient satisfaction and mental and physical health. Also, it is important noting that the authors combined both verbal (e.g., more positive talk, greater trust, and receptivity) and non-verbal (e.g., smile, gazing, eyebrow movements, and interpersonal touches) in their study. Therefore, it can be a bit challenging to directly conclude that effective verbal communication alone without non-verbal communication is effective on its own in improving patient-centred outcomes. Similarly, [ 34 ] combined both narrative-based and picture-based communication strategies to give patients education about health literacy. Therefore, it can be challenging to know whether narratives comprising of verbal communication (and often non-verbal communication) can improve patient-centred outcomes on their own. The rest of the studies were qualitative [ 35 , 36 ], which means that their findings generally reflected the subjective experiences or opinions of their participants. Therefore, it can be said that although all the four studies supported verbal communication can effectively improve patient-centred outcomes, there is a need for future research to experimentally test its effectiveness without being combined with non-verbal communication strategies.

Moreover, two of the four studies implied that some conditions must be met for verbal communication to be effective [ 32 , 35 ]. some communication strategies, such as higher lifestyle discussion and rapport-building rates, were perceived as patronising and associated with poor outcomes [ 32 ]. Instead, the authors found that communication strategies like seeking and giving biomedical and psychosocial information were more effective in improving patient outcomes [ 32 ]. It implies that healthcare providers should be attentive and intentional of the topics they discuss with patients. Further, in their qualitative study, [ 35 ] found that effective verbal communication also requires mutual respect, equity, and addressing conflict. Indeed, it appears that certain communication strategies like lifestyle discussions can undermine the process of establishing trust, which is why they were associated with adverse patient outcomes. Also, unlike nonverbal communication, the studies that highlighted the effect of verbal communication on patient-centred outcomes did not provide rich descriptions of the specific verbal communication strategies that can be used in a face-to-face healthcare setting. The described strategies like using phone calls to regularly communicate with the patient without having to visit a healthcare facility and things to ensure when communicating with the older patient, such as mutual respect and avoiding too many discussions on lifestyle do not offer rich insights into the specific nature of the verbal communication strategies.

Communication strategies

In 3.5.2 above, it was shown that the sample of participants that [ 32 ] used in their study did not prefer discussions related with healthy lifestyles, which compromised patient-centred outcomes. Therefore, it was also important to determine the best approaches to formulate communication strategies that work. Two out of the seven studies implied how communication strategies can be formulated [ 34 , 36 ] [ 36 ]. found that a tailored intervention delivered through telephone communication improved patient perceptions of the quality of care. In this regard, the authors first identified the needs of the patients to guide the development of the tailored intervention, from which they might have obtained insights into the patients’ communication preferences [ 34 ]. found a participatory approach to developing a curated story that improves health literacy appealing and understandable. The findings emphasised the need for participatory approaches when developing communication interventions for patients with varied health and social needs. Although the studies did not compare or contrast the effectiveness of participatory-based communication strategies and non-participatory-based communication strategies, their findings provide useful insights into the significance of involving patients when developing them. From their findings, it can be anticipated that a participatory approach is more likely to yield better patient-centred outcomes than non-participatory-based communication strategies.

Patient-centred outcomes

All studies reviewed highlighted patient-centred outcomes as the goal of effective communication in older patients. Patient-centred outcomes included well-being, self-esteem, health status, social processes, life satisfaction, self-actualisation, and self-responsibility (Butt, 2001), as well as patient satisfaction [ 32 , 36 ], increased awareness of COPD effects [ 36 ], and improved health literacy [ 34 ]. Others included presenting problems, mental health, and physical health [ 32 ], as well as adherence to providers’ recommendations, improved quality of care, and shorter hospital stays [ 37 ]. All seven studies indicated that the various verbal and nonverbal communication approaches could improve these patient-centred outcomes. The consistency observed between the experimental study by [ 31 ], the qualitative studies, and other quantitative study designs implies the need to pay greater attention to verbal and non-verbal communication strategies used by healthcare professionals as they can directly influence numerous patient-centred outcomes. This consistency further implies that effective communication is the anchor of high-quality care, and its absence will always compromise patient-centred outcomes, such as satisfaction and health outcomes.

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion of findings.

In agreement with various studies and reviews conducted in younger populations [ 1 – 3 ], all the seven studies selected in this rapid review supported that effective communication is a cornerstone of improved patient-centred outcomes. Like [ 5 , 11 , 12 ], the studies reviewed in this rapid review also supported the idea that effective communication with older adults involves the combination of verbal and nonverbal communication cues. However, this rapid review went a step ahead to identify the specific conditions that must be present for effective verbal and nonverbal communication to take place, such as perceptions of equity, mutual respect, and addressing conflict instead of avoiding it. The qualitative studies used in this rapid review also offered rich descriptions of how providers use nonverbal communication strategies.

However, the main shortcoming of the seven studies reviewed is that none aimed to define or describe what constitutes effective communication with older adults, apart from [ 37 ], who described a model of nonverbal communication with older adults. The study was qualitative and only formed a theoretical basis of how effective nonverbal communication with older adults could be shaped. The theory developed needs to be tested in an experimental setting so that its effect size in improving patient-centred outcomes, such as quality of care, quality of life, patient satisfaction, and emotional and cognitive well-being, can be documented unbiasedly and validly. Therefore, as much as the reviewed studies agreed with younger populations regarding the positive effect of effective and quality communication on patient-centred outcomes [ 9 , 10 ], the methodological rigour of studies with older patients needs to be improved.

Although the individual studies reviewed in this rapid review had low risk of bias apart from [ 31 ], the screening was based on the judgment of the individual research designs. Otherwise, if the assessment had been done from the perspective of the focus of this rapid review, the risk of bias in studies could have been high in predicting the influence of effective communication on patient-centred outcomes. First, apart from [ 31 ], none of the studies used a random sample. The qualitative studies used purposively obtained samples, which means the risk of bias from an interventional perspective was high. However, the studies provided in-depth insights into the characteristics and features of verbal and non-verbal communication strategies that can be used to form and maintain provider-patient relationships.

Recommendations for practice and future research

The main recommendation for practice is that nurses and providers serving older patients must be aware of their verbal and non-verbal communication strategies. Besides, they should engage in continuous professional development to enhance their verbal and non-verbal communication skills. Combining a wide range of nonverbal communication, such as touching the patient on the shoulder or arm or even handshaking can help create strong bonds and relationships, which are key in an effective therapeutic relationship. The qualitative studies reviewed showed that nurses and other providers combine a wide range of nonverbal communication in a single interaction instance, such as eye gazing, nodding, touching, and eyebrow movement. Although studies on verbal communication were rare in this rapid review, some lessons learned from the few studies included (e.g., [ 36 ]) is that using telephones to communicate with older patients regularly is potentially effective in improving patient-centred outcomes like better self-management. The information shared by the nurse should be tailored to serve the specific health needs of older patients. For example, for COPD patients, a nurse can make regular calls to old patients to educate them about the importance of quitting smoking and alcohol to improve their health condition and better self-management. However, as [ 32 ] indicated, the nurse should be cautious about how to present the information to the client and be able to detect patronising discussions quickly. For example, the sample of adults used by [ 32 ] found that many lifestyle and rapport-building discussions with the nurse were patronising in ways that may be detrimental to patient-centred outcomes. Some of the strategies providers can employ to ensure that communication is not perceived as patronising by older patients include ensuring mutual respect (e.g., active listening as a sign of mutual respect), creating perceptions of equity rather than favouritism when communicating with multiple patients at a time, and solving conflicts rather than avoiding them, which entails extra efforts, such as understanding the patient’s behaviour in the past and present. Overall, although studies have not provided specific estimates of the effect sizes of effective communication on patient-centred outcomes among older adults, there is a general trend and consensus in studies that effective communication, nonverbal and verbal, is the cornerstone of high-quality healthcare.

Further, future research needs to address various gaps identified in this study. The first gap is that although [ 37 ] tried to develop a model of nonverbal communication with older adults, their study had some drawbacks that limited the comprehensiveness of the model. First, the authors used a sample of only eight older adults in two medical wards in Cameroon. Besides the small sample, the study was conducted in medical wards, which means its findings may not be generalisable to long-term care settings like nursing homes. More older adults who encounter healthcare professionals are admitted in long-term care facilities, calling for developing a more robust communication strategy. Second, [ 37 ] only focused on nonverbal communication, thereby providing limited practical applicability of the model since verbal and nonverbal communication co-exists in a single interactional instance. Therefore, there is a need to develop a model that provides a complete picture into what effective communication is like with older adults.

After developing a valid, reliable, and generalisable model for effective communication with older adults in various healthcare settings, future research should also focus on investigating the impact of such a model on patient-centred outcomes, such as quality of care, quality of life, patient satisfaction, and physical and mental health. More particularly, the developed model can be used to derive communication interventions, which can be applied and tested in various healthcare settings with older adults. That way, research on this subject matter will mature as more and more studies test the effectiveness of such a communication model in various settings and countries. All that is known in the literature is that effective verbal and nonverbal communication can help promote patient-centred outcomes among older adults.

Limitations

Although this rapid review was conducted rigorously by adhering to the PRISMA guidelines, the use of a single reviewer in the study selection process can undermine the quality of the review. When a single reviewer is involved, the probability of missing out relevant studies increases immensely. However, this limitation was mitigated in this review by using an automation tool in the study selection process. In was assumed that combining the automation tool with one independent reviewer could significantly reduce the probability of missing relevant studies.

Another possible limitation is that few studies have been conducted between 2000 and 2023 investigating the effect of effective communication on various patient-centred outcomes. Although the literature recognises the importance of effective communication, and there is a unanimous agreement between studies of various research designs that it is the cornerstone of quality of care, more studies need to be conducted examining how various communication strategies influence patient outcomes, both subjective and objective. For example, [ 31 ] investigated the effect of comfort touch. Other studies using empirical means (e.g., experiments) can also test the other strategies identified, such as eye gazing, head nodding, eyebrow movement, et cetera. In this way, a more specific and structured approach to communication in healthcare settings can be developed using the evidence base.

Moreover, I initially intended to review studies published within the past five years (2018–2023) but later learned there were insufficient studies meeting the eligibility criteria. Consequently, I adjusted the publication date to the past ten years (2013–2023). I also learned insufficient studies published within that period. Consequently, I chose the period of 2000–2023, which yielded seven studies. Thus, some of the studies included may not capture contemporary realities in healthcare settings, raising the need for more empirical studies on this topic.

This rapid review selected seven studies whose narrative synthesis demonstrated that effective verbal and non-verbal communication could improve patient-centred outcomes. However, the studies were mostly qualitative, and hence they only provided rich descriptions of how nurses and older patients communicate in various clinical settings. It is only one study (Butts, 2001) that was experimental. Still, its risk of bias was high since patients were not concealed to allocation, and participants and outcome assessors were not blinded. Future research needs to focus on deriving a valid, reliable, and generalisable communication model with older adults using a larger and more representative sample size of older patients. Such a model should encompass both verbal and nonverbal communication. After developing a robust model, the next phase of future studies is to derive interventions based on the model and then, through experimental research, test their effectiveness. In that way, a standard approach to communicating effectively and in quality will be achieved, which is yet to be achieved in the current studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

I thank my wife and children for their patience and the great opportunity to devote a lot of time to doing the article in the best possible way.

Authors’ contributions

I am the primary and sole author of this article. My contribution to this article is a full contribution.

Data Availability

Declarations.

The authors declare no competing interests.

‘Not applicable’ for that section. The article is a rapid review type.

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

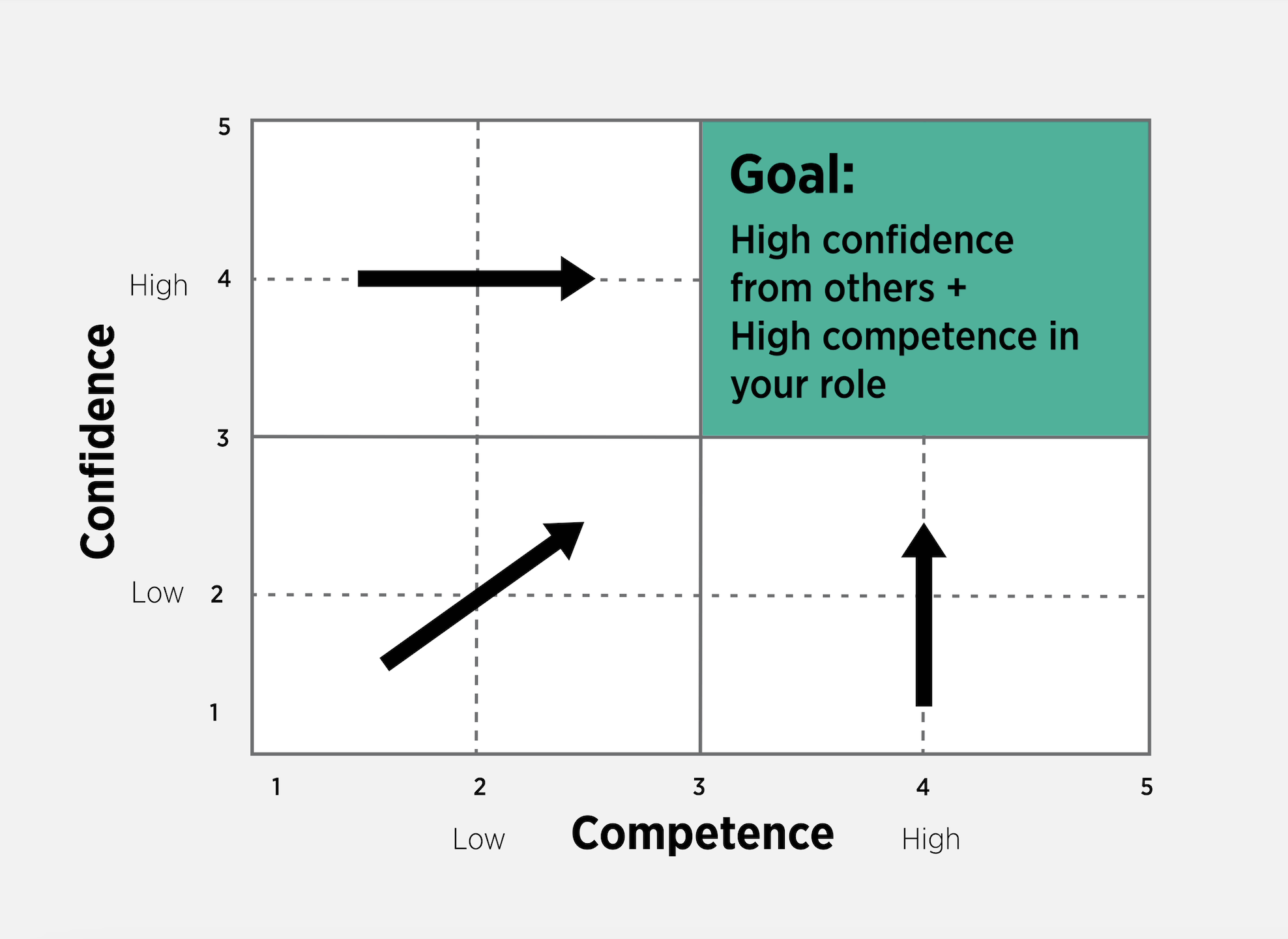

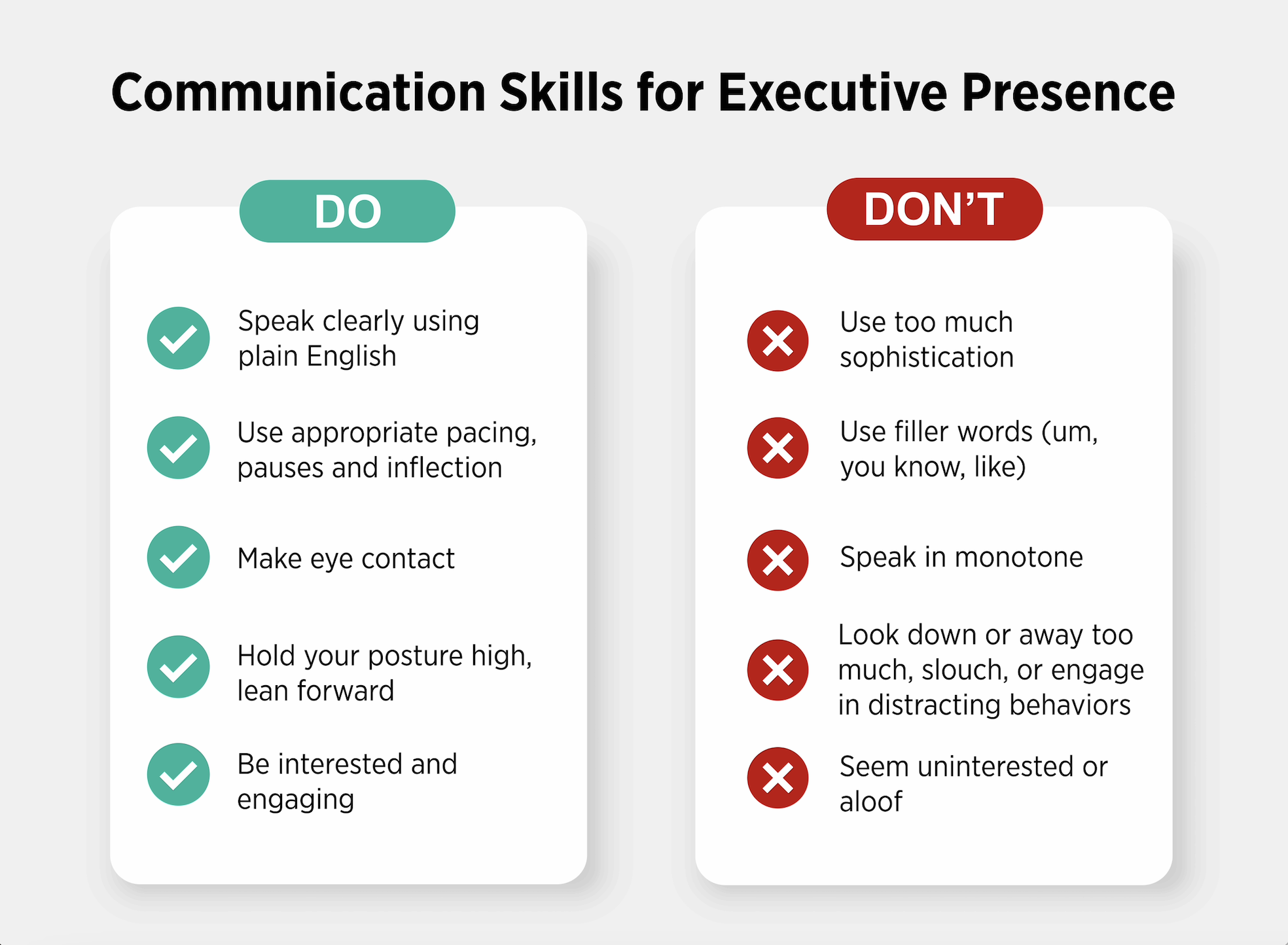

How Great Leaders Communicate

- Carmine Gallo

Four strategies to motivate and inspire your team.

Transformational leaders are exceptional communicators. In this piece, the author outlines four communication strategies to help motivate and inspire your team: 1) Use short words to talk about hard things. 2) Choose sticky metaphors to reinforce key concepts. 3) Humanize data to create value. 4). Make mission your mantra to align teams.

In the age of knowledge, ideas are the foundation of success in almost every field. You can have the greatest idea in the world, but if you can’t persuade anyone else to follow your vision, your influence and impact will be greatly diminished. And that’s why communication is no longer considered a “soft skill” among the world’s top business leaders. Leaders who reach the top do not simply pay lip service to the importance of effective communication. Instead, they study the art in all its forms — writing, speaking, presenting — and constantly strive to improve on those skills.

- Carmine Gallo is a Harvard University instructor, keynote speaker, and author of 10 books translated into 40 languages. Gallo is the author of The Bezos Blueprint: Communication Secrets of the World’s Greatest Salesman (St. Martin’s Press).

Partner Center

Undergraduate Research Opportunities Center

Present or publish your research or creative activity, effective communication: case study, three types of communication.

Communicating with your audience is more than giving a handful of information, it is the use of clear language that is factual and logical to depict to the audience that the message is essential to their lives and their future.

The biggest communication problem is we do not listen to understand. We listen to reply.

Here is a video depicting why it is important to tailor to your audience's needs

Communicating to a Diverse Demographic Audience

This video depicts the importance of communication to different demographic audience members. Making sure that your presentation is understood by all individuals is a valuable communication tool

Remember that no matter the audience, everyone should understand and enjoy the information you are presenting.

Thanks for helping us improve csumb.edu. Spot a broken link, typo, or didn't find something where you expected to? Let us know. We'll use your feedback to improve this page, and the site overall.

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Communication →

- 16 Feb 2024

- Research & Ideas

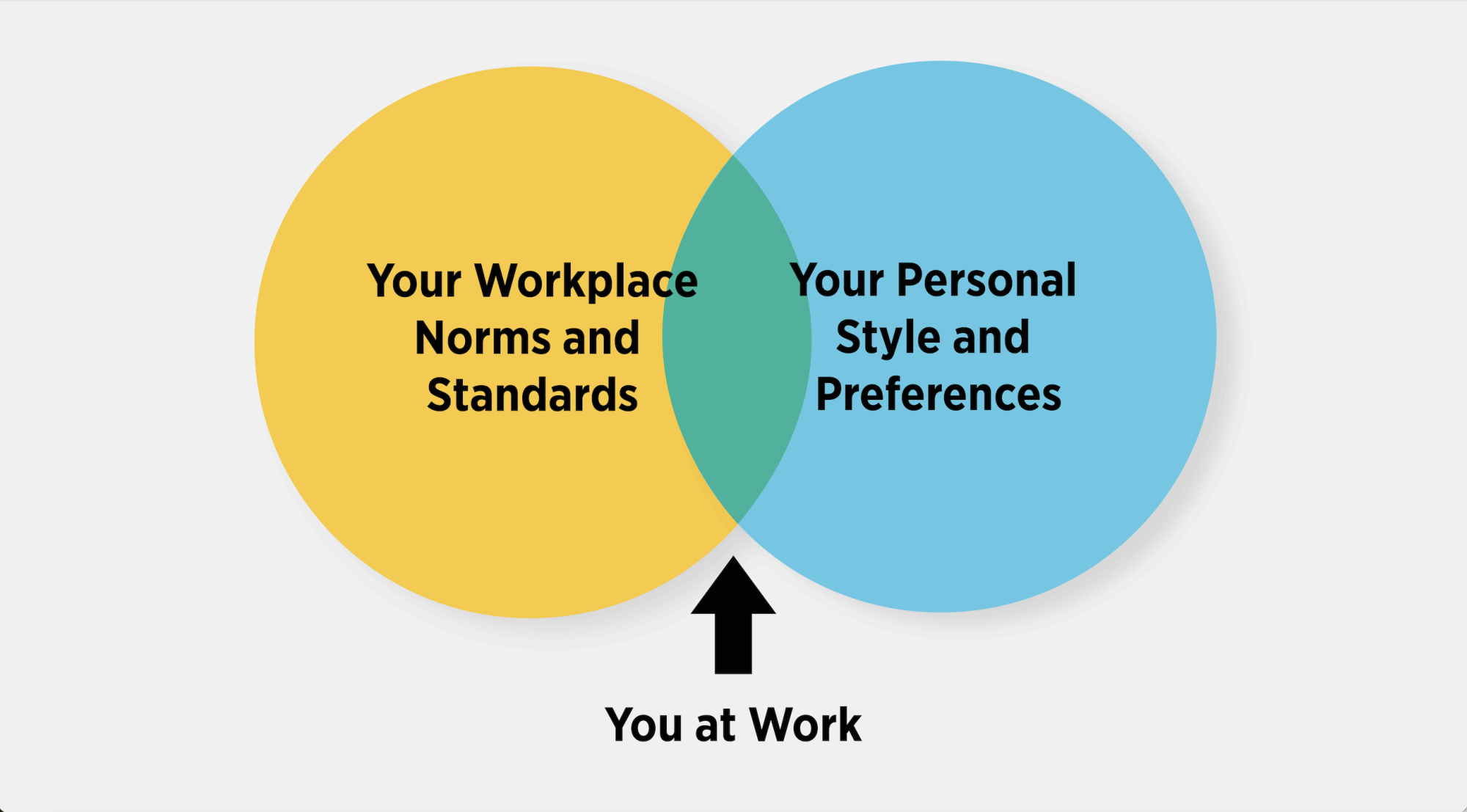

Is Your Workplace Biased Against Introverts?

Extroverts are more likely to express their passion outwardly, giving them a leg up when it comes to raises and promotions, according to research by Jon Jachimowicz. Introverts are just as motivated and excited about their work, but show it differently. How can managers challenge their assumptions?

- 06 Nov 2023

Did You Hear What I Said? How to Listen Better

People who seem like they're paying attention often aren't—even when they're smiling and nodding toward the speaker. Research by Alison Wood Brooks, Hanne Collins, and colleagues reveals just how prone the mind is to wandering, and sheds light on ways to stay tuned in to the conversation.

.jpg)

- 31 Oct 2023

Checking Your Ethics: Would You Speak Up in These 3 Sticky Situations?

Would you complain about a client who verbally abuses their staff? Would you admit to cutting corners on your work? The answers aren't always clear, says David Fubini, who tackles tricky scenarios in a series of case studies and offers his advice from the field.

- 24 Jul 2023

Part-Time Employees Want More Hours. Can Companies Tap This ‘Hidden’ Talent Pool?

Businesses need more staff and employees need more work, so what's standing in the way? A report by Joseph Fuller and colleagues shows how algorithms and inflexibility prevent companies from accessing valuable talent in a long-term shortage.

- 23 Jun 2023

This Company Lets Employees Take Charge—Even with Life and Death Decisions

Dutch home health care organization Buurtzorg avoids middle management positions and instead empowers its nurses to care for patients as they see fit. Tatiana Sandino and Ethan Bernstein explore how removing organizational layers and allowing employees to make decisions can boost performance.

- 24 Jan 2023

Passion at Work Is a Good Thing—But Only If Bosses Know How to Manage It

Does showing passion mean doing whatever it takes to get the job done? Employees and managers often disagree, says research by Jon Jachimowicz. He offers four pieces of advice for leaders who yearn for more spirit and intensity at their companies.

- 10 Jan 2023

How to Live Happier in 2023: Diversify Your Social Circle

People need all kinds of relationships to thrive: partners, acquaintances, colleagues, and family. Research by Michael Norton and Alison Wood Brooks offers new reasons to pick up the phone and reconnect with that old friend from home.

- 15 Nov 2022

Why TikTok Is Beating YouTube for Eyeball Time (It’s Not Just the Dance Videos)

Quirky amateur video clips might draw people to TikTok, but its algorithm keeps them watching. John Deighton and Leora Kornfeld explore the factors that helped propel TikTok ahead of established social platforms, and where it might go next.

- 03 Nov 2022

Feeling Separation Anxiety at Your Startup? 5 Tips to Soothe These Growing Pains

As startups mature and introduce more managers, early employees may lose the easy closeness they once had with founders. However, with transparency and healthy boundaries, entrepreneurs can help employees weather this transition and build trust, says Julia Austin.

- 15 Sep 2022

Looking For a Job? Some LinkedIn Connections Matter More Than Others

Debating whether to connect on LinkedIn with that more senior executive you met at that conference? You should, says new research about professional networks by Iavor Bojinov and colleagues. That person just might help you land your next job.

- 08 Sep 2022

Gen Xers and Millennials, It’s Time To Lead. Are You Ready?

Generation X and Millennials—eagerly waiting to succeed Baby Boom leaders—have the opportunity to bring more collaboration and purpose to business. In the book True North: Emerging Leader Edition, Bill George offers advice for the next wave of CEOs.

- 05 Aug 2022

Why People Crave Feedback—and Why We’re Afraid to Give It

How am I doing? Research by Francesca Gino and colleagues shows just how badly employees want to know. Is it time for managers to get over their discomfort and get the conversation going at work?

- 23 Jun 2022

All Those Zoom Meetings May Boost Connection and Curb Loneliness

Zoom fatigue became a thing during the height of the pandemic, but research by Amit Goldenberg shows how virtual interactions can provide a salve for isolation. What does this mean for remote and hybrid workplaces?

- 13 Jun 2022

Extroverts, Your Colleagues Wish You Would Just Shut Up and Listen

Extroverts may be the life of the party, but at work, they're often viewed as phony and self-centered, says research by Julian Zlatev and colleagues. Here's how extroverts can show others that they're listening, without muting themselves.

- 24 May 2022

Career Advice for Minorities and Women: Sharing Your Identity Can Open Doors

Women and people of color tend to minimize their identities in professional situations, but highlighting who they are often forces others to check their own biases. Research by Edward Chang and colleagues.

- 12 May 2022

Why Digital Is a State of Mind, Not Just a Skill Set

You don't have to be a machine learning expert to manage a successful digital transformation. In fact, you only need 30 percent fluency in a handful of technical topics, say Tsedal Neeley and Paul Leonardi in their book, The Digital Mindset.

- 08 Feb 2022

Silos That Work: How the Pandemic Changed the Way We Collaborate

A study of 360 billion emails shows how remote work isolated teams, but also led to more intense communication within siloed groups. Will these shifts outlast the pandemic? Research by Tiona Zuzul and colleagues. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- Cold Call Podcast

What’s Next for Nigerian Production Studio EbonyLife Media?

After more than 20 years in the media industry in the UK and Nigeria, EbonyLife Media CEO Mo Abudu is considering several strategic changes for her media company’s future. Will her mission to tell authentic African stories to the world be advanced by distributing films and TV shows direct to customers? Or should EbonyLife instead distribute its content through third-party streaming services, like Netflix? Assistant Professor Andy Wu discusses Abudu’s plans for her company in his case, EbonyLife Media. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

.jpg)

- 11 Jan 2022

Feeling Seen: What to Say When Your Employees Are Not OK

Pandemic life continues to take its toll. Managers who let down their guard and acknowledge their employees' emotions can ease distress and build trust, says research by Julian Zlatev and colleagues. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 04 Jan 2022

Scrap the Big New Year's Resolutions. Make 6 Simple Changes Instead.

Self-improvement doesn't need to be painful, especially during a pandemic. Rather than set yet another gym goal, look inward, retrain your brain, and get outside, says Hirotaka Takeuchi. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- Relationships

Why Communication Matters

We communicate to create, maintain, and change relationships and selves..

Posted July 15, 2021 | Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

- Why Relationships Matter

- Find a therapist to strengthen relationships

- How we communicate helps relationships get off on the right foot, navigate problems, and change over time.

- In communication, we develop, create, maintain, and alter our relationships.

- We communicate to work our way through family changes and challenges in verbal and non-verbal ways.

I remember seeing a poster on my junior high classroom wall: “Communication is the Beginning of Understanding.” This spoke to me at the time. Yet, like so many people, I had never really thought much about communication. I would have described communication as sending and receiving messages.

Communication Is More Than Sending and Receiving Messages

In reality, communication is often about transmitting information. We send and receive messages with people in our lives. Daily, much of our communication consists of coordinating schedules, “What time are you getting home for dinner?” and negotiating whose turn it is to do the dishes, pay the bills, or take dinner to a friend who is ill. We send messages like, “It is your turn to let the dog out” and receive messages like, “Don’t forget to get dog food at the store” (if you have not guessed, a lot of the messages in my house are about the dog).

We might also blame problems on communication, talking about “communication breakdowns” or on a “lack of communication.” If we think about communication in these ways, we have missed so much that is important about communication. We have neglected how and why communication matters.

Communication Matters to Creating and Changing Relationships

We become aware of how Communication Matters when

- We confront issues with work-life balance.

- We experience positive events like the birth of a baby or winning an award.

- We have a friend does who does not do or say what we expect.

- We have disagreements over religious beliefs or political values.

Both positive and challenging events affect, reflect, and change our identity and the identity of our personal and family relationships. What do I mean by this? How did these relationships come into being? Well, think about the last time you started a new friendship or had a new member join your family. Through what you and the other person said and did, what we’d call verbal and nonverbal communication , these relationships took shape.

Sometimes relationships develop easily and clearly. They are healthy and pleasant. Other times, relationships develop in stress and storm and may be healthy or not. How we communicate helps relationships get off on the right foot, navigate problems, and change over time.

What is important to understand is that relationships are talked into (and out of) being. In communication, we develop, create, maintain, and alter our relationships. As we communicate, we become and change who we are. Think about how you have grown and changed as you communicate at home, at work, with friends, and in your community.

Communication Matters to Relationship and Family Identity

As we communicate, we co-create relationships and our own identity. As you think about your close relationships and your family, you can likely recall important events, both positive and negative, that impacted how you understand your relationship and yourself as a person.

Consider this example: one of my college students described a childhood family ritual of going out on the front lawn on Christmas Eve. The family sang Christmas carols and threw carrots on the roof for Santa’s reindeers. The family still does this annual carrot-throwing ritual in adulthood. You can picture them bringing their sometimes confused new partners and spouses out in the snow to throw carrots onto the roof and sing.

Why does this family still throw carrots and sing? Through this seemingly silly ritual, the family celebrates who they are as a family and the togetherness that is important to them. The family creates space for new people to join the family. Through their words and actions, members of the family teach their new partners how to be family members through carrot throwing and other vital experiences.

I am sure you can point to experiences that have been central to creating your relationships and your identity.

Communication Matters as We Face Change and Challenges

We also communicate to work our way through family changes and challenges. Family members or others may have different expectations of what our family and personal identity or should be. This is especially true when a family does not fit dominant cultural models, such as single-parent families, multi-ethnic families, stepfamilies, LGBTQ families, or adoptive families.

For me, becoming a stepfamily was highly challenging. We became a stepfamily when I was 12 years old. My mother had recently died, and my Dad surprised us, kids, introducing us to the woman he wanted to marry. We no longer matched the other families in the neighborhood where we’d lived most of our lives. We certainly did not feel like a family overnight.

It took my stepfamily several years to create an understanding of what it meant to be a family. As we interacted, and with many mistakes and some successes, we slowly came to understand what we needed and expected from each other to be a family.

For all of us, relationship and family identity is constantly developing and changing. In my case, I remember my stepmom reminding me to wear a jacket when going out in the evening, even into my 40s, and giving me advice about my health. At some point, our roles changed, and now, as she moves toward her 80s, more often than not, I am in the role of asking about her health and helping her with significant decisions. What it means to be a mother or daughter and what we expect of each other and ourselves change as we interact.

Communication Matters . Whether we are negotiating whose turn it is to feed the dog, how to become a parent, how to interact with a difficult co-worker, or how to celebrate with a friend who won a major award, it is in communication that we learn what to do and say. This is what I will write about in this blog as I reflect on what I have learned as a professor and researcher of interpersonal and family communication. I invite you to go on this journey with me. I hope to give you insights into your communication.

Communication Matters. Communication is the Beginning of Understanding . It is an exciting and ever-changing journey.

Baxter, L. A. (2004). Relationships as dialogues. Personal Relationships, 11 , 1-22. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00068.x

Braithwaite, D. O., Foster, E. A., & Bergen, K. M. (2018). Social construction theory: Communication co-creating families. In D. O. Braithwaite, E. A. Suter, & K. Floyd. (Eds.). Engaging theories in family communication: Multiple perspectives (2nd ed., pp. 267-278). Routledge.

Braithwaite, D. O., Waldron, V. R., Allen, J., Bergquist, G., Marsh, J., Oliver, B., Storck, K., Swords, N., & Tschampl-Diesing, C. (2018). “Feeling warmth and close to her”: Communication and resilience reflected in turning points in positive adult stepchild-stepparent relationships. Journal of Family Communication, 18 , 92-109. doi: 10.1080/15267431.2017.1415902

Dawn O. Braithwaite, Ph.D., a professor of communication at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, studies families and close relationships, especially step- and chosen families.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

Effective Communication in the Workplace

Source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/social-media-connections-networking-3846597/ is in the Public Domain at Pixabay.com. Retrieved 07.05.2022.

Effective workplace communication helps maintain the quality of working relationships and positively affects employees' well-being. This article discusses the benefits of practicing effective communication in the workplace and provides strategies for workers and organizational leaders to improve communication effectiveness.

Workplace Communication Matters

Effective workplace communication benefits employees' job satisfaction, organizational productivity, and customer service (Adu-Oppong & Agyin-Birikorang, 2014). We summarized Bosworth's (2016) and Adu-Oppong and Agyin-Birikorang's (2014) works below related to the benefits of practicing effective communication in the workplace.

- Reduces work-related conflicts

- Enhances interpersonal relationships

- Increases workers' performance and supervisors' expectations

- Increases workforce productivity through constructive feedback

- Increases employee engagement and job satisfaction

- Builds organizational loyalty and trust

- Reduces employees' turnover rate

- Facilitates the proper utilization of resources

- Uncovers new employees' talents

Strategies to Improve Communication Effectiveness

Effective communication is a two-way process that requires both sender and receiver efforts. We summarized research works and guidelines for good communication in the workplace proposed by Cheney (2011), Keyton (2011), Tourish (2010), and Lunenburg (2010).

Sender's strategies for communication planning

- Clearly define the idea of your message before sharing it.

- Identify the purpose of the message (obtain information, initiate action, or change another person's attitude)

- Be aware of the physical and emotional environment in which you communicate your message. Consider the tone you want to use, the configuration of the space, and the context.

- Consult with others when you do not feel confident or comfortable communicating your message.

- Be mindful of the primary content of the message.

- Follow-up previous communications to verify the information.

- Communicate on time, avoid postponing hard conversations, and be consistent.

- Be aware that your actions support your messages and be coherent in your verbal and behavioral communication style.

- Be a good listener, even when you are the primary sender.

Receiver's strategies during a conversation

- Show interest and attitude to listen.

- Listen more than talk.

- Pay attention to the talker and the message, avoiding distractions.

- Be patient and allow the talker time to transmit the message.

- Be respectful and avoid interrupting a talker.

- Hold your temper. An angry person takes the wrong meaning from words

- Go easy on argument and criticism.

- Engage in the conversation by asking questions. This attitude helps develop key points and keep a fluid conversation.

Effective communication practices are essential for any successful team and organization. Organizational communication helps to disseminate important information to employees and builds relationships of trust and commitment.

Key points to improve communication in the workplace

- Set clear goals and expectations

- Ask clarifying questions

- Schedule regular one-on-one meetings

- Praise in public, criticize in private

- Assume positive intent

- Repeat important messages

- Raise your words, not your voice

- Hold town hall meetings and cross-functional check-ins.

Adu-Oppong, A. A., & Agyin-Birikorang, E. (2014). Communication in the Workplace: Guidelines for improving effectiveness. Global journal of commerce & management perspective , 3 (5), 208–213.

Bosworth, P. (2021, May 19). The power of good communication in the workplace . Leadership Choice. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

Cheney, G. (2011). Organizational communication in an age of globalization: Issues, reflections, practices . Waveland Press.

Keyton, J. (2011). Communication and organizational culture: A key to understanding work experience . Sage.

Tourish, D. (2010). Auditing organizational communication: A handbook of research, theory, and practice . Routledge

Lunenburg, F. C. (2010). Communication: The process, barriers, and improving effectiveness. Schooling , 1 (1), 1-10.

- Adult leadership

- Volunteerism

- Volunteer management

You may also be interested in ...

Diferencias culturales en el ambiente laboral

Consejos Para Desarrollar una Filosofía Personal de Liderazgo

How to Become a Community Leader

Importance of Incorporating Local Culture into Community Development

Conducting Effective Surveys - 'Rules of the Road'

Conflict Styles, Outcomes, and Handling Strategies

Employee Disengagement and the Impact of Leadership

Dealing with Conflict

Developing Self-Leadership Competencies

Diversity Training in the Workplace

Personalize your experience with penn state extension and stay informed of the latest in agriculture..

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1. WHAT IS TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION?

1.4 Case Study: The Cost of Poor Communication

No one knows exactly how much poor communication costs business, industry and government each year, but estimates suggest billions. In fact, a recent estimate claims that the cost in the U.S. alone are close to $4 billion annually! [1] Poorly-worded or inefficient emails, careless reading or listening to instructions, documents that go unread due to poor design, hastily presenting inaccurate information, sloppy proofreading — all of these examples result in inevitable costs. The problem is that these costs aren’t usually included on the corporate balance sheet at the end of each year; if they are not properly or clearly defined, the problems remain unsolved.

You may have seen the Project Management Tree Cartoon before ( Figure 1.4.1 ); it has been used and adapted widely to illustrate the perils of poor communication during a project.

The waste caused by imprecisely worded regulations or instructions, confusing emails, long-winded memos, ambiguously written contracts, and other examples of poor communication is not as easily identified as the losses caused by a bridge collapse or a flood. But the losses are just as real—in reduced productivity, inefficiency, and lost business. In more personal terms, the losses are measured in wasted time, work, money, and ultimately, professional recognition. In extreme cases, losses can be measured in property damage, injuries, and even deaths.

The following “case studies” show how poor communications can have real world costs and consequences. For example, consider the “ Comma Quirk ” in the Rogers Contract that cost $2 million. [3] A small error in spelling a company name cost £8.8 million. [4] Examine Edward Tufte’s discussion of the failed PowerPoint presentation that attempted to prevent the Columbia Space Shuttle disaster. [5] The failure of project managers and engineers to communicate effectively resulted in the deadly Hyatt Regency walkway collapse. [6] The case studies below offer a few more examples that might be less extreme, but much more common.

In small groups, examine each “case” and determine the following:

- Define the rhetorical situation : Who is communicating to whom about what, how, and why? What was the goal of the communication in each case?

- Identify the communication error (poor task or audience analysis? Use of inappropriate language or style? Poor organization or formatting of information? Other?)

- Explain what costs/losses were incurred by this problem.

- Identify possible solution s or strategies that would have prevented the problem, and what benefits would be derived from implementing solutions or preventing the problem.

Present your findings in a brief, informal presentation to the class.

Exercises adapted from T.M Georges’ Analytical Writing for Science and Technology. [7]

CASE 1: The promising chemist who buried his results

Bruce, a research chemist for a major petro-chemical company, wrote a dense report about some new compounds he had synthesized in the laboratory from oil-refining by-products. The bulk of the report consisted of tables listing their chemical and physical properties, diagrams of their molecular structure, chemical formulas and data from toxicity tests. Buried at the end of the report was a casual speculation that one of the compounds might be a particularly safe and effective insecticide.

Seven years later, the same oil company launched a major research program to find more effective but environmentally safe insecticides. After six months of research, someone uncovered Bruce’s report and his toxicity tests. A few hours of further testing confirmed that one of Bruce’s compounds was the safe, economical insecticide they had been looking for.

Bruce had since left the company, because he felt that the importance of his research was not being appreciated.

CASE 2: The rejected current regulator proposal

The Acme Electric Company worked day and night to develop a new current regulator designed to cut the electric power consumption in aluminum plants by 35%. They knew that, although the competition was fierce, their regulator could be produced more affordably, was more reliable, and worked more efficiently than the competitors’ products.