Literature Reviews

- Introduction

- Tutorials and resources

- Step 1: Literature search

- Step 2: Analysis, synthesis, critique

- Step 3: Writing the review

If you need any assistance, please contact the library staff at the Georgia Tech Library Help website .

Analysis, synthesis, critique

Literature reviews build a story. You are telling the story about what you are researching. Therefore, a literature review is a handy way to show that you know what you are talking about. To do this, here are a few important skills you will need.

Skill #1: Analysis

Analysis means that you have carefully read a wide range of the literature on your topic and have understood the main themes, and identified how the literature relates to your own topic. Carefully read and analyze the articles you find in your search, and take notes. Notice the main point of the article, the methodologies used, what conclusions are reached, and what the main themes are. Most bibliographic management tools have capability to keep notes on each article you find, tag them with keywords, and organize into groups.

Skill #2: Synthesis

After you’ve read the literature, you will start to see some themes and categories emerge, some research trends to emerge, to see where scholars agree or disagree, and how works in your chosen field or discipline are related. One way to keep track of this is by using a Synthesis Matrix .

Skill #3: Critique

As you are writing your literature review, you will want to apply a critical eye to the literature you have evaluated and synthesized. Consider the strong arguments you will make contrasted with the potential gaps in previous research. The words that you choose to report your critiques of the literature will be non-neutral. For instance, using a word like “attempted” suggests that a researcher tried something but was not successful. For example:

There were some attempts by Smith (2012) and Jones (2013) to integrate a new methodology in this process.

On the other hand, using a word like “proved” or a phrase like “produced results” evokes a more positive argument. For example:

The new methodologies employed by Blake (2014) produced results that provided further evidence of X.

In your critique, you can point out where you believe there is room for more coverage in a topic, or further exploration in in a sub-topic.

Need more help?

If you are looking for more detailed guidance about writing your dissertation, please contact the folks in the Georgia Tech Communication Center .

- << Previous: Step 1: Literature search

- Next: Step 3: Writing the review >>

- Last Updated: Feb 21, 2024 10:07 AM

- URL: https://libguides.library.gatech.edu/litreview

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

How scientists are making the most of Reddit

Career Feature 01 APR 24

Overcoming low vision to prove my abilities under pressure

Career Q&A 28 MAR 24

How a spreadsheet helped me to land my dream job

Career Column 28 MAR 24

Superconductivity case shows the need for zero tolerance of toxic lab culture

Correspondence 26 MAR 24

Cuts to postgraduate funding threaten Brazilian science — again

The beauty of what science can do when urgently needed

Career Q&A 26 MAR 24

The corpse of an exploded star and more — March’s best science images

News 28 MAR 24

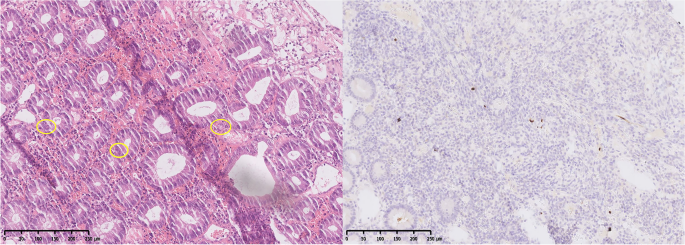

How papers with doctored images can affect scientific reviews

Nature is committed to diversifying its journalistic sources

Editorial 27 MAR 24

Supervisory Bioinformatics Specialist, CTG Program Head

National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Library of Medicine (NLM) National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Information Engineering...

Washington D.C. (US)

National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information

Postdoc Research Associates in Single Cell Multi-Omics Analysis and Molecular Biology

The Cao Lab at UT Dallas is seeking for two highly motivated postdocs in Single Cell Multi-Omics Analysis and Molecular Biology to join us.

Dallas, Texas (US)

the Department of Bioengineering, UT Dallas

Expression of Interest – Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions – Postdoctoral Fellowships 2024 (MSCA-PF)

Academic institutions in Brittany are looking for excellent postdoctoral researchers willing to apply for a Marie S. Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship.

France (FR)

Plateforme projets européens (2PE) -Bretagne

Tenure-track Assistant Professor in Ecological and Evolutionary Modeling

Tenure-track Assistant Professor in Ecosystem Ecology linked to IceLab’s Center for modeling adaptive mechanisms in living systems under stress

Umeå, Sweden

Umeå University

Faculty Positions in Westlake University

Founded in 2018, Westlake University is a new type of non-profit research-oriented university in Hangzhou, China, supported by public a...

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 10:40 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

Critically analyze and evaluate

Tip: read and annotate pdfs.

- 6. Synthesize

- 7. Write a Literature Review

Ask yourself questions like these about each book or article you include:

- What is the research question?

- What is the primary methodology used?

- How was the data gathered?

- How is the data presented?

- What are the main conclusions?

- Are these conclusions reasonable?

- What theories are used to support the researcher's conclusions?

Take notes on the articles as you read them and identify any themes or concepts that may apply to your research question.

This sample template (below) may also be useful for critically reading and organizing your articles. Or you can use this online form and email yourself a copy .

- Sample Template for Critical Analysis of the Literature

Opening an article in PDF format in Acrobat Reader will allow you to use "sticky notes" and "highlighting" to make notes on the article without printing it out. Make sure to save the edited file so you don't lose your notes!

Some Citation Managers like Mendeley also have highlighting and annotation features.Here's a screen capture of a pdf in Mendeley with highlighting, notes, and various colors:

Screen capture from a UO Librarian's Mendeley Desktop app

- Learn more about citation management software in the previous step: 4. Manage Your References

- << Previous: 4. Manage Your References

- Next: 6. Synthesize >>

- Last Updated: Jan 10, 2024 4:46 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

Scholarly Writing pp 41–70 Cite as

Writing the Literature Review: Common Mistakes and Best Practices

- Kelly Heider 3

- First Online: 21 November 2023

357 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

The literature review is an essential component of academic research writing, providing a comprehensive overview of existing research and informing the development of new studies. However, writing an effective literature review can be a challenging task for many authors, particularly those new to academic writing. This chapter aims to guide authors through the process of writing a literature review by highlighting common mistakes and best practices. The chapter begins with three short narratives that describe difficulties both novice and prolific authors encounter when writing the literature review. A chapter activity follows with steps that guide authors through the process of developing a research question to frame the literature review. Authors are then prompted to complete a self-assessment activity which includes a series of questions designed to build their skills as academic research writers. The body of the chapter recommends strategies and techniques to help authors locate and evaluate sources that will serve as the building blocks for a literature review that is thorough, current, and well-written. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the threats and benefits of artificial intelligence-based text production in relationship to academic research writing. Overall, this chapter provides practical guidance for authors looking to improve their literature review writing skills and enhance the quality of their research output.

- Locating sources

- Developing research questions

- Constructing search strings

- Evaluating sources

- Writing the literature review

- Analyzing the literature review

- AI-based text production

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Anson, C. M. (2022). AI-based text generation and the social construction of “fraudulent authorship”: A revisitation. Composition Studies, 50 (1), 37–46.

Google Scholar

Aylward, K., Sbaffi, L., & Weist, A. (2020). Peer-led information literacy training: A qualitative study of students’ experiences of the NICE evidence search student champion scheme. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 37 (3), 216–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12301

Article Google Scholar

Bohannon, J. (2013, October 4). Who’s afraid of peer review? Science, 342 (6154), 60–65. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.342.6154.60

Bouchrika, I. (2023, March 17). Top 10 qualities of good academic research . Research. https://research.com/research/top-10-qualities-of-good-academic-research

Bowler, M., & Street, K. (2008). Investigating the efficacy of embedment: Experiments in information literacy integration. Reference Services Review, 36 , 438–449. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320810920397

De La Torre, M. (2018, August 29). Academic racism: The repression of marginalized voices in academia . The Activist History Review. https://activisthistory.com/2018/08/29/academic-racism-the-repression-of-marginalized-voices-in-academia/

Drewes, K., & Hoffman, N. (2010). Academic embedded librarianship: An introduction. Public Services Quarterly, 6 (2–3), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2010.498773

Elsevier Author Services. (n.d.a). Journal acceptance rates: Everything you need to know . Publication process. https://scientific-publishing.webshop.elsevier.com/publication-process/journal-acceptance-rates/#:~:text=your%20paper%20to%3F-,What%20Our%20Research%20Shows,over%201%25%20to%2093.2%25 .

Elsevier Author Services. (n.d.b). What is a good H-index? Publication recognition. https://scientific-publishing.webshop.elsevier.com/publication-recognition/what-good-h-index/

Emerald Publishing. (2023). How to…conduct empirical research . https://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/how-to/research-methods/conduct-empirical-research

Enago Academy. (2022, May 3). How much research is enough for a good literature review? https://www.enago.com/academy/research-for-a-good-literature-review/

Fitzgibbons, M. (2021). Literature review synthesis matrix . Concordia University Library. [Adapted from original table by the WI+RE Team at UCLA Library.] https://www.concordia.ca/content/dam/library/docs/research-guides/gradproskills/Lit-review-synthesis-matrix-Word.docx

Garrett, W. (n.d.) Marginalized populations . Minnesota Psychological Association. https://www.mnpsych.org/index.php?option=com_dailyplanetblog&view=entry&category=division%20news&id=71:marginalized-populations

George Mason University Libraries. (2021, August 20). Find authors . Finding diverse voices in academic research. https://infoguides.gmu.edu/c.php?g=1080259&p=7871669

Gyles, C. (2014, February). Can we trust peer-reviewed science? The Canadian Veterinary Journal, 55 (2), 109–111. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3894865/#b2-cvj_02_109

Hern, A. (2022, December 4). AI bot ChatGPT stuns academics with essay-writing skills and usability . The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/dec/04/ai-bot-chatgpt-stuns-academics-with-essay-writing-skills-and-usability

Hoffman, N., Beatty, S., Feng, P., & Lee, J. (2017). Teaching research skills through embedded librarianship. Reference Services Review, 45 , 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-07-2016-0045

Indeed Editorial Team. (2022, June 28). Create a theoretical framework for your research in 4 steps . Indeed. https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/theoretical-framework

Jansen, D. (2021, June). How to choose your research methodology . GradCoach. https://gradcoach.com/choose-research-methodology/

Jansen, D., & Warren, K. (2020, June). What (exactly) is a literature review? GradCoach. https://gradcoach.com/what-is-a-literature-review/

Jin, Y. Y., Noh, H., Shin, H., & Lee, S. M. (2015). A typology of burnout among Korean teachers. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 24 (2), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-014-0181-6

Koufogiannakis, D., Buckingham, J., Alibhai, A., & Rayner, D. (2005). Impact of librarians in first-year medical and dental student problem-based learning (PBL) groups: A controlled study. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 22 , 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2005.00559.x

Larsen, C. M., Terkelsen, A. S., Carlsen, A. F., & Kristensen, H. K. (2019). Methods for teaching evidence-based practice: A scoping review. BMC Medical Education, 19 , 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1681-0

Liberties EU. (2021, October 5). What is marginalization? Definition and coping strategies . https://www.liberties.eu/en/stories/marginalization-and-being-marginalized/43767

Lucey, B., & Dowling, M. (2023). ChatGPT: Our study shows AI can produce academic papers good enough for journals—just as some ban it . The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/chatgpt-our-study-shows-ai-can-produce-academic-papers-good-enough-for-journals-just-as-some-ban-it-197762

Maior, E., Dobrean, A., & Păsărelu, C. (2020). Teacher rationality, social-emotional competencies, and basic needs satisfaction: Direct and indirect effects on teacher burnout. Journal of Evidence—Based Psychotherapies, 20 (1), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.24193/jebp.2020.1.8

Mertens, D. M. (2019). Research and evaluation in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Monash University. (2023). Structuring a literature review . Learn HQ. https://www.monash.edu/learnhq/excel-at-writing/how-to-write.../literature-review/structuring-a-literature-review

Nova, A. (2017, December 21). Learn how to write a literature review in simple steps . MyPerfectWords. https://myperfectwords.com/blog/research-paper-guide/how-to-write-a-literature-review

O’Byrne, I. (2018, February 9). Eight steps to write a literature review . https://wiobyrne.com/literature-review/

Online Campus Writing Center. (2023). Synthesis . The Chicago School of Professional Psychology. https://community.thechicagoschool.edu/writingresources/online/Pages/Synthesis.aspx

Phair, D. (2021, June). Writing a literature review: 7 common (and costly) mistakes to avoid . GradCoach. https://gradcoach.com/literature-review-mistakes/

Robinson, K. A., Akinyede, O., Dutta, T., Sawin, V. I., Li, T., Spencer, M. R., Turkelson, C. M., & Weston, C. (2013, February). Framework for determining research gaps during systematic review: Evaluation . Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (U.S.). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK126702/

Rommelspacher, A. (2020, November). How to structure your literature review: Three options to help structure your chapter . GradCoach. https://gradcoach.com/literature-review-structure/

Royal Literary Fund. (2023). The structure of a literature review . https://www.rlf.org.uk/resources/the-structure-of-a-literature-review/

Rudestam, K. E., & Newton, R. R. (1992). Surviving your dissertation: A comprehensive guide to content and process . SAGE Publications.

Scimago Lab. (2022a). About us . Scimago Journal and Country Rank. https://www.scimagojr.com/aboutus.php

Scimago Lab. (2022b). Journal rankings . Scimago Journal and Country Rank. https://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php

Shumaker, D. (2009). Who let the librarians out? Embedded librarianship and the library manager. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 48 (3), 239–257.

Statistics Solutions. (2023). Tips for the literature review: Synthesis and analysis . Complete dissertation. https://www.statisticssolutions.com/tips-for-the-literature-review-synthesis-and-analysis/

TechTarget. (2023). What is OpenAI? Open AI. https://www.techtarget.com/searchenterpriseai/definition/OpenAI

Texas A&M University Writing Center. (2023). Self-assessment . https://writingcenter.tamu.edu/Faculty-Advisors/Resources-for-Teaching/Feedback/Self-Assessment

University of Colorado at Colorado Springs. (2022, May 13). Evaluate sources. Public administration research. https://libguides.uccs.edu/c.php?g=617840&p=4299162

University of Maryland Global Campus. (n.d.). Discipline-specific research methods . https://coursecontent.umgc.edu/umgc/shareable-content/toolkits/BEHS000/1402/ResearchMethods/Discipline-SpecificResearchMethods.html

University of Melbourne. (2017, September 21). Academic writing: Writing the literature review [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=70n2-gAp7J0

Walker, R., & Solvason, C. (2014). Methodology: Choosing your research approach . SAGE Publications.

Wardle, E., & Downs, D. (2019). Writing about writing (4th ed.). Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Wiggers, K. (2023, January 31). OpenAI releases tool to detect AI-generated text, including from ChatGPT . TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2023/01/31/openai-releases-tool-to-detect-ai-generated-text-including-from-chatgpt/

Yilmaz, K., Altinkurt, Y., Guner, M., & Sen, B. (2015). The relationship between teachers’ emotional labor and burnout level. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 59 , 75–90.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Acting Assistant Vice Provost for University Libraries, Indiana University of PA, Indiana, PA, USA

Kelly Heider

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kelly Heider .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Emerita, Indiana, PA, USA

Mary Renck Jalongo

Teaching & Learning, Policy & Leadership, University of Maryland, College Park, College Park, MD, USA

Olivia N. Saracho

Issue: AI-Based Text Production in Academic Research Writing

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a relatively new technological development that can be used to support academic research writing, particularly reviews of research. Although it holds promise as a research tool, there are also concerns that AI-based scholarly writing could threaten not only the integrity but also the creativity of academic research writing. ChatGPT, an advanced chatbot developed by OpenAI (a nonprofit research company founded by Elon Musk and Sam Altman in 2015) has been at the center of much controversy as of late because of its ability to produce academic papers using artificial intelligence-based text production that have fooled academics and academic journal publishers (Hern, 2022 ; Lucey & Dowling, 2023 ; TechTarget, 2023 ). To demonstrate ChatGPT’s capabilities, consider its response to the question, “What is artificial intelligence-based text production?”.

Artificial Intelligence-Based Text Production is a process where machine learning algorithms are used to generate written content such as articles, product descriptions, social media posts, and more. It involves training machine learning models with vast amounts of data to learn how to generate human-like text automatically. The process can involve different techniques such as Natural Language Processing (NLP), deep learning, and neural networks to analyze and understand language patterns, grammar, context, and semantics. The resulting AI-generated text can be used for a wide range of applications, including content marketing, chatbots, language translation, and more. One of the main benefits of AI-based text production is that it can help businesses and organizations automate their content creation process, saving time and resources while producing high-quality content. However, it is important to note that AI-generated text may not always be perfect and may require human editing and review to ensure accuracy and coherence.

This response was produced by ChatGPT in about ten seconds. According to Anson ( 2022 ), “cutting and pasting all or part of this auto-generated text into a new text box can continue to prompt further content. The material is not plagiarized from existing sources but freshly composed. For this reason, it usually evades plagiarism-detection programs like Turnitin” (p. 40).

How Might AI-Based Text Production Threaten Academic Research Writing?

Obviously, computer-generated text that evades plagiarism-detection programs threatens the integrity of academic research writing. Some academic publishers have already banned or limited the use of AI-generated text in papers submitted to their journals (Lucey & Dowling, 2023 ). However, that is easier said than done. OpenAI recently developed a tool that attempts to distinguish between human-written and AI-generated text to prevent chatbots like ChatGPT from being abused, but it is only 26% effective (Wiggers, 2023 ).

Lucey and Dowling ( 2023 ) tested the credibility of ChatGPT by having expert reviewers examine papers produced by the chatbot. First, they asked ChatGPT to generate four parts of a research study: (1) research idea, (2) literature review, (3) dataset, and (4) suggestions for testing and examination. They chose a broad subject and instructed the chatbot to create a paper that could be published in “a good finance journal” (para. 6). Second, they pasted 200 relevant abstracts into the ChatGPT search box and asked the chatbot to consider the abstracts when generating the four-part research study. Finally, they asked academic researchers to read both versions of the AI-generated text and make suggestions for improvement. A panel of thirty-two reviewers read all versions of the four-part research study and rated them. In all cases, the papers were considered acceptable by the reviewers, although the chatbot-created papers that also included input from academic researchers were rated higher. However, “a chatbot was deemed capable of generating quality academic research ideas. This raises fundamental questions around the meaning of creativity and ownership of creative ideas—questions to which nobody yet has solid answers” (Lucey & Dowling, 2023 , para. 10).

How Might AI-Based Text Production Benefit Academic Research Writing?

Despite several publishers deciding to ban the inclusion of AI-based text production in submissions, some researchers have already listed ChatGPT as a co-author on their papers (Lucey & Dowling, 2023 ). There are many who believe there is no difference between the way ChatGPT produces text and the way authors synthesize studies in their literature reviews. In fact, the chatbot’s review is much more exhaustive because it can analyze “billions of existing, human-produced texts and, through a process akin to the creation of neural networks, generate new text based on highly complex predictive machine analysis” (Anson, 2022 , p. 39).

There are other advantages to using AI-based text production. It has the potential to aid groups of researchers who lack funding to hire human research assistants such as emerging economy researchers, graduate students, and early career researchers. According to Lucey and Dowling ( 2023 ), AI-based text production “could help democratize the research process” (para. 18). Anson ( 2022 ) also sees the potential in AI-based text production to “spark some new human-generated ideas” (p. 42), extract keywords, and create abstracts. The development of AI-based text production might also force instructors to change the way they teach academic writing. Instead of trying to detect or prevent the use of chatbots like ChatGPT, “a more sensible approach could involve embracing the technology, showing students what it can and can’t do, and asking them to experiment with it” (Anson, 2022 , p. 44). In other words, students could be asked to write about writing which leads to a deeper understanding of the writing process and the ability to transfer that understanding to any writing project (Wardle & Downs, 2019 ).

The Responsible Use of AI-Based Text Production in Academic Research Writing

The responsible use of AI-based text production in academic research writing involves understanding the technology's capabilities and limitations, as well as considering its potential impact on the research process. Researchers must carefully evaluate the intended purpose and context of using AI-generated text and make certain they are not compromising the authenticity and integrity of their research work. To ensure responsible use, it is essential to balance the benefits of increased efficiency and new insights with the need for originality and critical thinking in academic research writing. Researchers must also be transparent in disclosing the use of AI-generated text when submitting their work for publication. By adopting a responsible and thoughtful approach to the use of AI-based text production, researchers can maximize the benefits of the technology while maintaining the quality and authenticity of their research.

Applications of Technology

How to Write a Paper in a Weekend : https://youtu.be/UY7sVKJPTMA

Note : University of Minnesota Chemistry Professor, Peter Carr is not advocating for procrastination. This video outlines a strategy for generating a first draft after you have all your reading and notes assembled.

Research Gap 101: What Is a Research Gap & How to Find One : https://youtu.be/Kabj0u8YQ4Y

Using Google Scholar for Academic Research : https://youtu.be/t8_CW6FV8Ac .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Heider, K. (2023). Writing the Literature Review: Common Mistakes and Best Practices. In: Renck Jalongo, M., Saracho, O.N. (eds) Scholarly Writing. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-39516-1_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-39516-1_3

Published : 21 November 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-39515-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-39516-1

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Literature Reviews: Critical reading & evaluating

- What are literature reviews

- How & where to search

- Critical reading & evaluating

- Managing your results

- Publishing your review

Critical reading and evaluating

The ability to think critically and approach information objectively is an important academic skill.

To critically evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, and validity of a piece of information, consider the following:

- Identify the main points or arguments

- Evaluate each part of the source i.e. the methodology, the discussion, the findings/conclusions

- Analyse the arguments the author is making

- Approach information objectively and evaluate what is being said

- Does it disagree with the criteria you have selected?

- Can you see any weaknesses or gaps in the argument?

- Is there data or other research provided to support the argument?

- Has it highlighted something you had not investigated?

For more information use the Researcher Skills Toolkit - Evaluate module.

Deciding what to use

Not everything that you find will fit your criteria exactly. Once you have evaluated and analysed the information, you can determine the relevance of each source.

Consider and document the following:

- Will the source be used in your research?

- Why has it been included or excluded?

- Which part of your research does it address?

- What are the key concepts identified in the source?

- Screening and critical analysis tools used in your research

There are several screening and critical appraisal tools you can use in a review to assist with your appraisal.

Check the Appraisal, Extraction and Synthesis section of the Systematic Review Library Guide for more details.

For more information, visit Academic Learning Support resources on ' think, read and write critically '

Evaluating Information

- << Previous: How & where to search

- Next: Managing your results >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 11:54 AM

- URL: https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/Litreviews

- Library Homepage

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide: Evaluating Sources & Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews?

- Strategies to Finding Sources

- Keeping up with Research!

- Evaluating Sources & Literature Reviews

- Organizing for Writing

- Writing Literature Review

- Other Academic Writings

Evaluating Literature Reviews and Sources

- Tips for Evaluating Sources (Print vs. Internet Sources) Excellent page that will guide you on what to ask to determine if your source is a reliable one. Check the other topics in the guide: Evaluating Bibliographic Citations and Evaluation During Reading on the left side menu.

Criteria to evaluate sources:

- Authority : Who is the author? What are the author's credentials and areas of expertise? Is he or she affiliated with a university?

- Usefulness : How this source related to your topic? How current or relevant it is to your topic?

- Reliability : Does the information comes from a reliable, trusted source such as an academic journal?

- Critically Analyzing Information Sources: Critical Appraisal and Analysis (Cornell University Library) Ten things to look for when you evaluate an information source.

Reading Critically

Reading critically (summary from how to read academic texts critically).

- Who is the author? What is his/her standing in the field?

- What is the author’s purpose? To offer advice, make practical suggestions, solve a specific problem, critique or clarify?

- Note the experts in the field: are there specific names/labs that are frequently cited?

- Pay attention to methodology: is it sound? what testing procedures, subjects, materials were used?

- Note conflicting theories, methodologies, and results. Are there any assumptions being made by most/some researchers?

- Theories: have they evolved over time?

- Evaluate and synthesize the findings and conclusions. How does this study contribute to your project?

- How to Read Academic Texts Critically Excellent document about how best to read critically academic articles and other texts.

- How to Read an Academic Article This is an excellent paper that teach you how to read an academic paper, how to determine if it is something to set aside, or something to read deeply. Good advice to organize your literature for the Literature Review or just reading for classes.

- << Previous: Keeping up with Research!

- Next: Organizing for Writing >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 11:44 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucsb.edu/litreview

- Herron School of Art

- Ruth Lilly Law

- Ruth Lilly Medical

- School of Dentistry

Literature Review - A Self-Guided Tutorial

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the question

- 2. Review discipline styles

- Searching article databases - video

- Finding the article full-text

- Citation chaining

- When to stop searching

- 4. Manage your references

- 5. Critically analyze and evaluate

- 6. Synthesize

- 7. Write literature review

Who's My Librarian?

Locate your University Library's subject librarian for personalized assistance.

Students doing research in specific areas may also request assistance at other IUPUI libraries:

- IU School of Dentistry Library

- Ruth Lilly Law Library

- Ruth Lilly Medical Library

Critically analyze and evaluate

Ask yourself questions like these about each book or article you include:

- What is the research question?

- What is the primary methodology used?

- How was the data gathered?

- How is the data presented?

- What are the main conclusions?

- Are these conclusions reasonable?

- What theories are used to support the researcher's conclusions?

Take notes on the articles as you read them and identify any themes or concepts that may apply to your research question.

This sample template (below) may also be useful for critically reading and organizing your articles.

- Sample Template for Critical Analysis of the Literature

Opening an article in PDF format in Acrobat Reader will allow you to use "sticky notes" and "highlighting" to make notes on the article without printing it out. Make sure to save the edited file so you don't lose your notes!

- << Previous: 4. Manage your references

- Next: 6. Synthesize >>

- Last Updated: Jun 15, 2023 8:24 AM

- URL: https://iupui.libguides.com/literaturereview

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Getting Started

- Introduction

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

Reading Critically

To be able to write a good literature review, you need to be able to read critically. Below are some tips that will help you evaluate the sources for your paper.

Reading critically (summary from How to Read Academic Texts Critically)

- Who is the author? What is his/her standing in the field?

- What is the author’s purpose? To offer advice, make practical suggestions, solve a specific problem, to critique, or clarify?

- Note the experts in the field. Are there specific names/labs that are frequently cited?

- Pay attention to methodology. Is it sound? What testing procedures, subjects, and materials were used?

- Note conflicting theories, methodologies and results. Are there any assumptions being made by most/some researchers?

- Theories: Have they evolved overtime?

- Evaluate and synthesize the findings and conclusions. How does this study contribute to your project?

Useful links:

Tips to Evaluate Sources

Criteria to evaluate sources:

Authority : Who is the author? what is his/her credentials--what university he/she is affliliated? Is his/her area of expertise?

Usefulness : How this source related to your topic? How current or relevant it is to your topic?

Reliability : Does the information comes from a reliable, trusted source such as an academic journal?

Useful sites

- Critically Analyzing Information Sources (Cornell University Library)

Evaluating Literature Reviews and Sources

A good literature review evaluates a wide variety of sources (academic articles, scholarly books, government/NGO reports). It also evaluates literature reviews that study similar topics. This page offers you a list of resources and tips on how to evaluate the sources that you may use to write your review.

- A Closer Look at Evaluating Literature Reviews Excerpt from the book chapter, “Evaluating Introductions and Literature Reviews” in Fred Pyrczak’s Evaluating Research in Academic Journals: A Practical Guide to Realistic Evaluation , (Chapter 4 and 5). This PDF discusses and offers great advice on how to evaluate "Introductions" and "Literature Reviews" by listing questions and tips.

- Tips for Evaluating Sources (Print vs. Internet Sources) Excellent page that will guide you on what to ask to determine if your source is a reliable one. Check the other topics in the guide: Evaluating Bibliographic Citations and Evaluation During Reading on the left side menu.

- << Previous: Strategies to Find Sources

- Next: Tips for Writing Literature Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Literature reviews

- Introduction

- Conducting your search

- Store and organise the literature

Evaluate the information you have found

Critique the literature.

- Different subject areas

- Find literature reviews

When conducting your searches you may find many references that will not be suitable to use in your literature review.

- Skim through the resource - a quick read through the table of contents, the introductory paragraph or the abstract should indicate whether you need to read further or whether you can immediately discard the result.

- Evaluate the quality and reliability of the references you find - our page on evaluating information outlines what you need to consider when evaluating the books, journal articles, news and websites you find to ensure they are suitable for use in your literature review.

Critiquing the literature involves looking at the strength and weaknesses of the paper and evaluating the statements made by the author/s.

Books and resources on reading critically

- CASP Checklists Critical appraisal tools designed to be used when reading research. Includes tools for Qualitative studies, Systematic Reviews, Randomised Controlled Trials, Cohort Studies, Case Control Studies, Economic Evaluations, Diagnostic Studies and Clinical Prediction Rule.

- How to read critically - business and management From Postgraduate research in business - the aim of this chapter is to show you how to become a critical reader of typical academic literature in business and management.

- Learning to read critically in language and literacy Aims to develop skills of critical analysis and research design. It presents a series of examples of `best practice' in language and literacy education research.

- Critical appraisal in health sciences See tools for critically appraising health science research.

- << Previous: Store and organise the literature

- Next: Different subject areas >>

- Last Updated: Dec 15, 2023 12:09 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.uq.edu.au/research-techniques/literature-reviews

Literature Reviews

- Step 1: Understanding Literature Reviews

- Step 2: Gathering Information

- Step 3: Organizing your Information (Intellectually and Physically)

Analyzing and Evaluating the Literature

Evaluating your sources, analysing your sources.

- Step 5: Writing Your Literature Review

- Other Resources

How to evaluate a source

Consider the more obvious elements of the paper:.

- Is its title clear? Does it accurately reflect the content of the paper?

- Is the abstract well-structured (providing an accurate, albeit brief, description of the purpose, method, theoretical background of the research, as well as its results or conclusions?)

- What does their bibliography look like? For example, if most of their references are quite old despite being a newer paper, you should see if they provide an explanation for that in the paper itself. If not, you may want to consider why they do not have any newer sources informing their research.

- Is the journal its published in prestigious and reputable, or does the journal stand to gain something from publishing this paper? You may need to consider the biases of not only the author, but the publisher!

Evaluate the content:

- Look for identifiable gaps in their method, as well as potential problems with their interpretation of the data.

- Look for any obvious manipulations of the data.

- Do they themselves identify any biases or limitations, or do you notice any that they haven’t identified?

You are not just looking at what they are saying, but also at what they have NOT said. If they didn’t identify a clear gap or bias, why not? What does that say about the rest of the paper? If at all possible, you may want to see if you can identify where the funding for their study came from if you’re noticing these gaps, in case it is possible to spot a conflict of interest.

How do you analyze your sources?

It can be daunting to logically analyze the argument. If they are only showing one side and not addressing the topic from multiple perspectives, you may want to consider why, and if you feel they do a fair job of trying to present a holistic argument – if they don’t bring up conflicting information and demonstrate how they argument works against it, why not? You can also look for key red flags like:

- logical fallacies: mistakes in your reasoning that undermine the logic of the argument – usually identified due to a lack of evidence

- slippery slopes: a conclusion based on the idea that if one thing happens, it will trigger a series of other small steps leading to a drastic conclusion

- post hoc ergo propter hoc: a conclusion that says that if one event occurs after another, that it was the first event that caused the second due to chronology rather than evidence

- circular arguments: these are arguments that simply restate their premises rather than providing proof

- moral equivalence: this compares minor actions with major atrocities and concludes that both are equally immoral

- ad hominem: these are arguments that attack the character of the person making the argument rather than the argument itself

This is just a sample of the types or red flags that occur in academic writing. For more examples or further explanation, consult Purdue Owl’s academic writing guide, “ Logic in Argumentative Writing .”

- << Previous: Step 3: Organizing your Information (Intellectually and Physically)

- Next: Step 5: Writing Your Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Feb 6, 2024 5:46 PM

- URL: https://yorkvilleu.libguides.com/LiteratureReviews

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- Types of Literature Review

- Tips for Conducting a Literature Review

- Developing a Search Strategy

Tips for Writing your Literature Review

- Video Tutorial

Checklist for Literature Review

Does your literature review;

- Put your research into a wider context?

- Outline key relevant concepts or trends?

- Illustrate your unique/different perspective?

- Highlight a gap in the current research that your research will fill?

- Highlight a need for your research?

- Help to justify your selection of methodologies and methods (chapter 3)?

- Start reading

- Structuring your review

- Outline plan of your review

Writing the literature review can be daunting. However, creating an outline plan can help to simplify the process. Having gathered and evaluated the relevant information, you will need to begin to read. Use a reading strategy, for example skim, scan and intensive read. The next step will be to read critically , this means asking evaluative questions about information that you are reading.

- R ead, analyse and summarise the information you have gathered

Actively engage with the information by taking and making notes. Depending on the level of analysis that you need for your review, you could develop a criteria for analysing each source, using some (or similar) of the points below;

•Identify definitions, important quotes

•Identify strengths & weaknesses

•Extract main ideas, theories, concepts

•Identify the methodology (qualitative, quantitative or mixed), methods and data analysis methods

- Does this methodology improve upon previous studies?

- Was it appropriate for this research?

- Analyse and synthesise information from your sources & discuss

Following on from your analysis of the information, you can begin to identify common themes, ideas, methodologies, etc across your selected sources. You should begin to organise your material based on this analysis. Synthesise the information to support your research. This involves taking evidence (quotes, direct or indirect) from multiple sources and using them to support any claims you make. Discussing this analysis will be the main section of your literature review.

Regardless of the amount of information your have, you will need to present it in a structured and organised way. As you read the literature, you will begin to identify themes and patterns and a logical way of structuring information may present itself. Some popular methods of structuring information are:

•Topic

Material is organised by the main topics or issues within your research area

•Thematic

Material is organised according to the themes identified within your literature search

•Chronologicaly

Material is organised by the publication date of the literature

•Methodological

Material is organised by research design/methodology

Your literature review should tell a story, so it needs a beginning, a middle and an end. Use transitional sentences to make your train of thought easier to follow, and transitional words to indicate, contradictions, similarities, etc between points.

Chapter Outline

Introduction.

- Briefly highlight the uniqueness of your research relative to other research done within your topic.

- If you are focusing on themes or topics within a subject, outline which aspects you have included and excluded for purpose of the review. (it’s ok to acknowledge related themes or topics that exist but are not relevant to your research)