- +44 (0)1823 484444

- [email protected]

Helping Kiribati combat the effects of climate change

Find out how we are supporting data gathering in the low-lying island chain of Kiribati to help protect 115,000 people from coastal inundation.

As we face the unprecedented effects of climate change, so too do our oceans. Sea level rise, in particular, poses an imminent threat to our precious marine environments – a threat that will have life-changing implications for smaller coastal communities.

One such community is the island chain of Kiribati, comprising 32 islands that share an average height of just 2m above sea level. In fact, the United Nations predicts it could be completely overcome by the ocean within the 21st century.

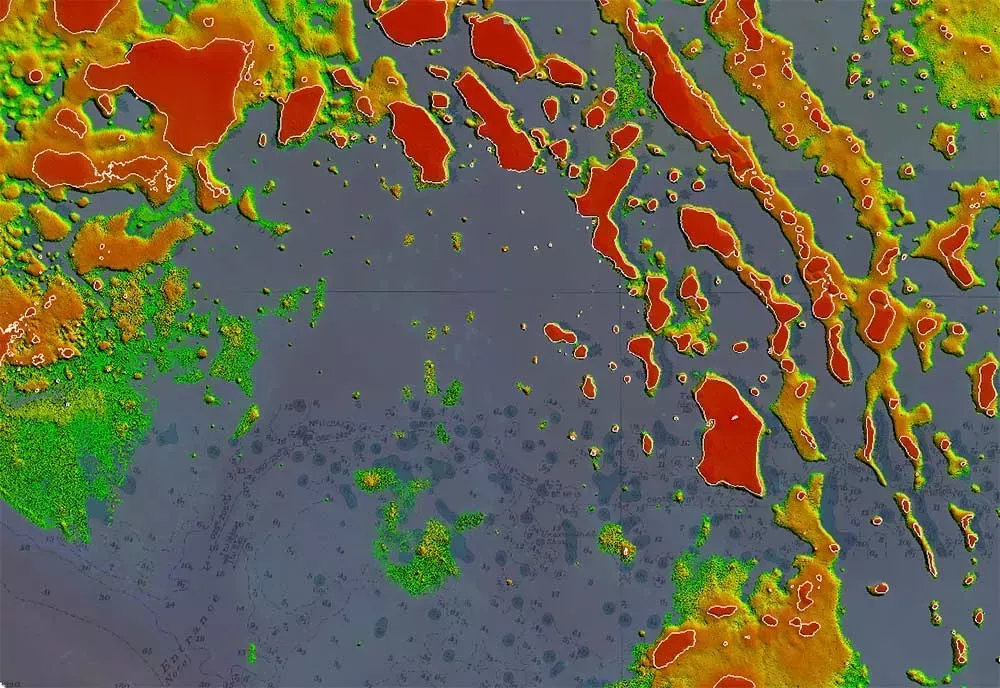

With sea level rise exacerbating the impact of storms, tsunamis and tidal surges, we’ve been helping to monitor and mitigate these effects by gathering vital data – starting with the surveys of islands and atolls spread over 3.5 million km 2 of ocean. For this, we captured data depicting the seabed with the use of satellite imagery; this method enabled us to access remote areas of ocean, all while minimising the impact on marine habitats that surround the islands. This data was handed over to the Kiribati Government last year to help them identify areas most at risk to flooding and plan sea defences accordingly.

The data collected will also enable the launch of the Kiribati Outer Island Transport Infrastructure Investment Project . Funded by the World Bank and Asian Development Bank , the project will help to improve maritime infrastructure in the outer islands and relieve the population pressure from its capital, Tarawa.

As part of global conservation efforts, we will continue to find new ways to support these vulnerable communities, so that we can protect the health of our oceans for generations to come.

Contact our team

This work was delivered in collaboration with the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office, World Bank and Asian Development Bank. If you are part of government and would like to find out how we can help you in a similar area, please get in touch with our government relations team using the contact information below.

You can also find out more about similar work on out government page.

Contact the UKHO

If you would like to speak to any of the team about our involvement in shaping the future of navigation, you can contact us using the form below.

UKHO privacy policy

Kiribati Relocation Strategy: An Exploration Of The Risks Kiribati Faces If Sea Levels Continue To Rise

by Virginia Raffaeli

Sea level rise is one of the most well known effects of the ongoing climate crisis. At a current estimated average rate of 3.6 mm per year, by 2050 sea level will have risen 24-32 cm [1]. Although this number may seem small, it is sufficient to have disastrous consequences on the hundreds of millions of people living in low-lying areas [2]. Amongst these, in the central Pacific Ocean we find the I-Kiribati, an indigenous people counting circa 119,000 individuals, living on the 32 atolls and one raised coral island which form the independent Republic of Kiribati [3].

According to the IPCC , if sea level rise continues at the present rate, by the middle of the century Kiribati is at risk of disappearing altogether [4]. The I-Kiribati are therefore facing an unprecedented question: what is the future of Kiribati and its people [5]?

Adaptation or displacement?

Pacific Island nations, such as Kiribati, are at the forefront of the climate crisis. First, they are extremely vulnerable to climate related events which are increasing in frequency due to the rise in global temperatures [1]. Second, they are amongst the least developed countries in the world and, as such, have little access to the resources necessary for effective mitigation and/or adaptation strategies [6].

Due to its high population density and scarce agricultural development, Kiribati is already plagued by food insecurity as well as significant water scarcity [7]. The rising sea level compounds these problems threatening the lives and livelihoods of the I-Kiribati [7].

For these reasons, in 2005 Kiribati’s president, Anote Tong, raised before the UN General Assembly the possibility of relocation of the entire I-Kiribati community, arguing that deliberate strategic relocation might be the ultimate form of adaptation to climate change [5].

Climate-induced migration, internal and cross-border, is not a novel idea. People have always relocated as a consequence of climate impacts, as was temporarily or permanently the case for over a million people following the flooding and destruction caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 [8, 9]. What is predicted to change, however, is the scale of the phenomenon. Indeed, there is growing consensus that “significant numbers” of people will not just relocate within their own territories, but will move across borders as environmental conditions worsen [10].

Yet, what the legal status of these persons will be remains uncertain [11].

Although often referred to as “climate refugees”, even people who are forcefully displaced due to their villages being swept away by water, for example, are not, legally speaking, “refugees” [11]. Since they are not “persecuted”, they cannot be classified as “refugees” under the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention [12, 13].

For this reason, alternative avenues for protection are being developed, ranging from initiatives such as the Sydney Declaration of Principles on the Protection of Persons Displaced in the Context of Sea Level Rise, to the application of human rights law [14, 10].

In Teitiota v New Zealand, in particular, an I-Kiribati man argued before the UN Human Rights Committee that, by sending him back to Kiribati, New Zealand would violate the principle of non-refoulement because the impacts of climate change represented a risk of irreparable harm to his right to life under the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights [15, 16]. Although Teitiota’s claim failed on the facts, the Committee did, nonetheless, recognise that in the future a similar claim may succeed [13, 15].

Migration with dignity and relocation to Fiji

As stated above, in just a few decades Kiribati may no longer exist as a physical territory. The I-Kiribati therefore are having to consider not whether they will have to leave, but how [5]. Rather than relying exclusively on its Adaptation Plan or on the eventuality of something like Teitiota’s claim one day succeeding, over the last fifteen years the Kiribati Government has adopted two separate strategies [17].

First, it has set up higher education and mobility programmes with states such as Australia and New Zealand, in line with a policy plan that has been referred to as “Migration with Dignity” [5, 18].

Second, it has taken steps to potentially implement the “deliberate strategic relocation” suggested by Anote Tong. In 2014 the Government struck a deal to purchase 5,460 acres of land in Fiji, with the declared aims of using it not only to ensure food security, but also as a possible destination of relocation [18].

Contrary to the “Migration with Dignity” programmes, which exclude people with limited literacy skills and largely subsistence livelihoods, and which are non considered to be sustainable long-term due to the restrictive migration requirements imposed by other states, the prospective relocation of the I-Kiribati to Fiji has been welcomed by the Fijian Government [17, 19].

Nevertheless, the submerging and relocation of Kiribati raises serious questions regarding firstly whether it could continue to exist as a sovereign state irrespective of the complete loss of territory [20]. More importantly, despite the fact that in 2014 the Fijian president stated that “The spirit of the people of Kiribati will not be extinguished [17]. It will live on somewhere else because a nation isn’t only a physical place”, the relocation also raises the issue of whether the I-Kiribati culture, traditions and language themselves and, therefore, the I-Kiribati as a people will survive [17].

Virginia Raffaeli is a law and policy researcher currently working for the Geopolitics and Global Futures Programme of the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP) in Switzerland. Before, she worked as a Legal Intern for the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), focusing on the impact of climate change on land in the context of indigenous and women’s rights. She holds an LL.B. from the University of Durham and an LL.M. in International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights from the Geneva Academy.

References:

[1] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2019). Special Report: Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, Chapter 4 Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities, paras. 4.1.2, 4.3.2, URL: https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/chapter/chapter-4-sea-level-rise-and-implications-for-low-lying-islands-coasts-and-communities (accessed 16 May 2021).

[2] Merkens, J.-L., L. Reimann, J. Hinkel and A. T. Vafeidis (2016). Gridded population projections for the coastal zone under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Global and Planetary Change , 145: 58-59, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2016.08.009 .

[3] Kiribati National Statistics Office (2020). Kiribati Population and Housing Census Provisional Results, URL: https://kir20phc.prism.spc.int/ (accessed 16 May 2021).

[4] Donner, S. D. and S. Webber (2014). Obstacles to climate change adaptation decisions: a case study of sea-level rise and coastal protection measures in Kiribati. Sustainability Science , 9 (3): 331-345, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-014-0242-z .

[5] Hermann E. and Kempf E. (2017). Climate Change and Imaging of Migration: Emerging Discourses on Kiribati’s Land Purchase in Fiji. The Contemporary Pacific , 29 (2): 231-233, 237, https://doi.org/10.1353/cp.2017.0030 .

[6] Barnett J., Adger W.N. (2003). Climate dangers and atoll countries. Climatic Change , 61: 321–337, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:CLIM.0000004559.08755.88 .

[7] Loughry M. and McAdam J. (2008). Kiribati – relocation and adaptation. Forced Migration Review , 31: 51-52, URL: https://www.fmreview.org/climatechange/loughry-mcadam .

[8] Borges I.M. (2018). Environmental Change, Forced Displacement and International Law: From Legal Protection Gaps to Protection Solutions . Milton, Routledge: 16.

[9] Sastry N., Gregory J. (2014). The Location of Displaced New Orleans Residents in the Year After Hurricane Katrina. Demography , 51 (3): 4, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0284-y .

[10] McAdam J. (2020). Protecting People Displaced by the Impacts of Climate Change: The UN Human Rights Committee and the Principle of Non-Refoulement. American Journal of International Law , 114(4): 712, 709, https://doi.org/10.1017/ajil.2020.31 .

[11] McAdam J. (2012). Conceptualising Climate Change-Related Movement, in American Society of International Law (2012). Confronting Complexity, Vol. 16, Proceedings of 106th Annual Meeting , Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 433-436, https://doi.org/10.5305/procannmeetasil.106.0433 .

[12] 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 189 UNTS 137 (adopted 28 July 1951, entered into force 22 April 1954), Art. 1A(2).

[13] Caskey C. (2020). Environmental Degradation: Examining the Entry Points and Improving Access to Protection. The Global Migration Research Paper Series , 26: 6, 16-17, ISBN: 978-2-8399-3111-3.

[14] Committee on International Law and Sea Level Rise (2018). Sydney Declaration of Principles on the Protection of Persons Displaced in the Context of Sea Level Rise, International Law Association ILA res. 6/2018, annex, 19-24 Aug. 2018.

[15] United Nations Human Rights Committee, Teitiota v. New Zealand (2019), UN Doc. CCPR/C/127/D/2728/2016, para. 9.7.

[16] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 999 UNTS 171 (adopted 16 December 1966, entered into force 23 March 1976), Article 6 .

[17] Roberts E. and Andrei S. (2015). The rising tide: migration as a response to loss and damage from sea level rise in vulnerable communities. International Journal of Global Warming , 8(2): 262, 264, 267, https://doi.org/10.1504/IJGW.2015.071965 .

[18] Oakes, R., Milan, A., and Campbell J. (2016). Kiribati: Climate change and migration – Relationships between household vulnerability, human mobility and climate change. Report No. 20. Bonn: United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS): 28, URL: https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:5903/Online_No_20_Kiribati_Report_161207.pdf .

[19] McNamara K.E. (2015). Cross-border migration with dignity in Kiribati, Forced Migration Review , 49: 64, URL: https://www.fmreview.org/climatechange-disasters/mcnamara .

[20] Kälin, W. (2010). Conceptualising climate-induced displacement, in McAdam, J. (Ed.). Climate Change and Displacement: Multidisciplinary Perspectives . Oxford and Portland, Hart Publishing: 81 – 103.

Tell us what you think! Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Related Posts

The #StopRosebank And #StopCambo Campaigns

Rosebank, if approved, would create more CO2 (through burning oil and gas) than the combined

ICJ Asked To Clarify Countries’ Obligations To Fight Climate Change

In a historic unanimous resolution the UNGA asked the ICJ to clarify what are states’

What Is The EACOP?

The East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) is a 1,443 km heated and buried pipeline

- International

- Schools directory

- Resources Jobs Schools directory News Search

Tectonics and Sea Level Rise (Kiribati case study)

Subject: Geography

Age range: 16+

Resource type: Lesson (complete)

Last updated

15 August 2022

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

In this lesson, students discover how tectonic activity has affected sea level change in the past and present. They go on to assess the landforms that are created as a result of sea level change, and evaluate the case study of Kiribati (links to resources on final slide). This lesson works well in conjunction with the Oxford AQA Geography A Level & AS Physical Geography Student Book (Ross, Bayliss, Collins, and Griffiths, 2016).

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

This resource hasn't been reviewed yet

To ensure quality for our reviews, only customers who have purchased this resource can review it

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

‘No safe place’: Kiribati seeks donors to raise islands from encroaching seas

Pacific state needs billions for its ambitious plan – its president demands wealthy nations act to help now

D eveloping countries vulnerable to the worst ravages of global heating have spent the past week at United Nations climate talks urging more support from wealthy nations. The Pacific state of Kiribati has a very specific and unusual demand – that its islands be physically raised up to escape the encroaching seas.

The plan to dig up huge clumps of sand and rocks from the seabed and layer them upon the thin coral atolls that make up Kiribati’s sparse landmass will cost “in the billions” of dollars, the country’s president, Taneti Maamau, told the Guardian.

Kiribati has secured a more modest amount from the World Bank to help protect its tenuous water supply but Maamau argues that the rich countries that have done the most to cause the climate crisis should pay out far more to help save this slice of Pacific island life.

“We’ve asked donors to help – the physical land is limited but we have a lot of sea area, we can reclaim those areas and raise them high,” he said. “[Developed countries] should act, because time is short for us. Every day counts, a delay of a day means loss to us. It’s time for action, we demand action now.

“For too long we have waited and waited and then the negotiation prolongs, maybe it’s one way of delaying loss and damage,” Maamau said of the animating issue for developing countries – a proposed form of finance given from rich countries to poor to help pay for climate damages – at the Cop27 talks in Egypt. “I hope they listen now, because they have to honour their commitments and pledges. They need to open their ears more clearly, and their minds. The wealthy countries are after all responsible for what we are now facing.”

Kiribati (pronounced Ki-ri-bahss, a local translation of “Gilberts”, its name under British colonial rule) is comprised of 33 coral atolls scattered across a huge expanse of ocean in the central Pacific ocean, between Hawaii and Australia. It covers more than 1.3m sq miles, making it one of the world’s largest nations when sea area is included, but is one of the smallest in terms of land, with most of its 120,000 population crammed into the narrow outcrops that make up Tarawa, its capital.

No part of Kiribati’s land rises more than two metres above the ocean, making it one of the most vulnerable places in the world to the sea level rise being driven by global heating. Several small islands have already been inundated by water, with parts of others eroded by the advancing tides. Intruding salt water threatens the ability to grow crops and risks the fresh groundwater that sits upon the porous reefs that form the basis of the islands.

The flooding is “scary at times”, according to Maamau, and has caused a “huge outcry” from the population of Kiribati to act. His government has decided that fortifying the islands is the best option, a departure from the previous president, Anote Tong, who championed a concept of “migrate with dignity”, where people would form growing expat communities in places like Australia and Fiji to escape the rising seas.

“If you move people to Fiji, they are also facing the same issue with climate change,” Maamau said. “So where can we go? The whole world is facing a climate crisis. There is no safe place. The option is to give the people their preference.”

The Kiribati public are largely in favour of staying and fighting for their survival, Maamau said. “They say, ‘We’ve been here for over 2,000 years, how can you convince us that our islands are going to disappear?’”

Sea level rise will be relentless this century, and beyond, even if planet-heating emissions are constrained. The global average will rise by up to a metre by 2100 , maybe more if the huge ice sheets at the poles break up faster than expected. This, according to hired consultants, will require Kiribati’s land to be raised by three to five metres to cope with storm surge, although the government considers this too high as it will impact people’s ability to access the sea, a key resource for food and income.

Anything up to three metres is acceptable to Maamau, although this will still require a huge operation to dredge the seabed (only one dredger, donated by Japan, is currently available) to bolster the coastlines. Rocks from Fiji have already been imported to defend areas eroding. In the lagoon that abuts Tarawa, sand and gravel naturally accumulates and could be accessed, although the task will be more complicated on more remote and sparsely populated islands.

“If it’s realistic anywhere it’s realistic in Tarawa, elsewhere you’d need to move communities to central locations to protect them,” said Simon Donner, a climate scientist and coral expert who has conducted research in Kiribati . “In the outer islands it becomes less feasible. But in many ways the other options are worse.”

It’s a widespread misconception, Donner said, that low-lying islands like Kiribati will simply drown under the rising seas. The flooding will shift and remould the islands rather than completely sink them, unless sea level rise is extreme, but the devastation wrought upon day-to-day life makes this process an “existential threat” to civilisation in Kiribati, he said.

“With a lower rate of sea level rise it’s conceivable the island itself survives but I’m not sure how the communities survive without a huge investment in adaption,” Donner said. This is technically possible, he said, pointing to China’s development of artificial islands for military purposes in disputed areas of the South China Sea.

“But this is a question of resources. If Kiribati was off the coast of Los Angeles you’d say it was doable. It’s possible if you throw enough resources at it, but who is going to do it for Kiribati? Sadly, it’s going to be down to how much rest of the world cares.”

Kiribati’s desire to generate new investment has enmeshed it within broader geopolitics, with Tong, who was president until 2016, accusing Maamau’s government of “cooking something with China”. Last year the government opened the Phoenix Islands Protected Area, one of the world’s largest marine reserves, to commercial fishing, where Chinese trawlers can fish for tuna. It’s also been speculated that China wants a military base within Kiribati territory, although both Beijing and Maamau have denied this.

“The western countries, those we thought we were very close with, have left us for so long, so we have to fill the gap,” said Maamau. “When Taiwan comes, and when China comes, they bring a lot. As donors, we have to deal with them.”

Donner said there were some “pretty disturbing” things happening in Kiribati, including the dismissal of the country’s chief justice to be replaced by the attorney general , leading to concerns over conflict of interest (Maamau denies any laws have been broken in this).

“That’s not good but I wouldn’t blame them for turning to China, because it’s not like countries that colonised them are helping them,” he said. “The whole thing is heartbreaking, really.”

- Asia Pacific

- Climate crisis

- Pacific islands

Most viewed

Geography of Kiribati

George Steinmetz / Getty Images

- Country Information

- Physical Geography

- Political Geography

- Key Figures & Milestones

- Urban Geography

- M.A., Geography, California State University - East Bay

- B.A., English and Geography, California State University - Sacramento

Kiribati is an island nation located in Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. It is made up of 32 island atolls and one small coral island spread out over 1.3 million square miles. The country itself, however, has only 313 square miles (811 sq km) of area. Kiribati is also along the International Date Line on its easternmost islands and it straddles the Earth's equator . Because it is on the International Date Line, the country had the line shifted in 1995 so that all of its islands could experience the same day at the same time.

Fast Facts: Kiribati

- Official Name: Republic of Kiribati

- Capital: Tarawa

- Population: 109,367 (2018)

- Official Languages: I-Kiribati, English

- Currency: Australian dollar (AUD)

- Form of Government: Presidential republic

- Climate: Tropical; marine, hot and humid, moderated by trade winds

- Total Area: 313 square miles (811 square kilometers)

- Highest Point: Unnamed elevation on Banaba island at 265 feet (81 meters)

- Lowest Point: Pacific Ocean at 0 feet (0 meters)

History of Kiribati

The first people to settle Kiribati were the I-Kiribati when they settled on what are the present-day Gilbert Islands around 1000-1300 BCE. Fijians and Tongans later invaded the islands. Europeans did not reach the islands until the 16th century. By the 1800s, European whalers, traders, and those selling enslaved people began visiting the islands and causing social problems. In 1892, the Gilbert and Ellice Islands agreed to become British protectorates. In 1900, Banaba was annexed after natural resources were found and in 1916 they all became a British colony. The Line and Phoenix Islands were also later added to the colony.

During World War II , Japan seized some of the islands and in 1943 the Pacific portion of the war reached Kiribati when United States forces launched attacks on the Japanese forces on the islands. In the 1960s, Britain began giving Kiribati more freedom of self-government and in 1975 the Ellice Islands broke away from the British colony and declared their independence in 1978. In 1977, the Gilbert Islands were given more self-governing powers and on July 12, 1979, they became independent with the name Kiribati.

Government of Kiribati

Today, Kiribati is considered a republic and it is officially called the Republic of Kiribati. The country's capital is Tarawa and its executive branch of government is made up of a chief of state and a head of government. Both of these positions are filled by Kiribati's president. Kiribati also has a unicameral House of Parliament for its legislative branch and Court of Appeal, High Court, and 26 Magistrates' courts for its judicial branch. Kiribati is divided into three different units, the Gilbert Islands, the Line Islands, and the Phoenix Islands, for local administration. There are also six different island districts and 21 island councils for Kiribati's islands.

Economics and Land Use in Kiribati

Because Kiribati is in a remote location and its area is spread over 33 small islands, it is one of the least developed Pacific island nations. It also has few natural resources, so its economy is mainly dependent on fishing and small handicrafts. Agriculture is practiced throughout the country and the main products of that industry are copra, taro, breadfruit, sweet potatoes, and assorted vegetables.

Geography and Climate of Kiribati

The islands making up Kiribati are located along the equator and International Date Line about halfway between Hawaii and Australia . The closest nearby islands are Nauru, the Marshall Islands, and Tuvalu . It is made up of 32 very low lying coral atolls and one small island. Because of this, Kiribati's topography is relatively flat and its highest point is an unnamed point on the island of Banaba at 265 feet (81 m). The islands are also surrounded by large coral reefs.

The climate of Kiribati is tropical and as such it is mainly hot and humid but its temperatures can be somewhat moderated by the trade winds.

- Central Intelligence Agency. "CIA - The World Factbook - Kiribati."

- Infoplease.com. " Kiribati: History, Geography, Government, and Culture. "

- United States Department of State. " Kiribati. "

- The Geography of Oceania

- Geography of Bermuda

- The World's 10 Smallest Countries

- The Philippines: Geography and Fact Sheet

- Geography of France

- Geography of Japan

- World War II: Battle of Makin

- Geography of Belize

- Geography of Hawaii

- Geography and History of Tuvalu

- The Maldives: Facts and History

- Geography of El Salvador

- What Is the International Date Line and How Does it Work?

- Basic Facts About U.S. Territories

- 10 Facts About Hong Kong

- History and Geography of Greenland

Explore historical and projected climate data, climate data by sector, impacts, key vulnerabilities and what adaptation measures are being taken. Explore the overview for a general context of how climate change is affecting Kiribati.

- Climate Change Overview

- Country Summary

- Climatology

- Trends & Variability

- Mean Projections (CMIP6)

- Mean Projections (CMIP5)

- Extreme Events

- Historical Natural Hazards

Sea Level Rise

This page is undergoing an update and new offerings will be available soon.

- VIEW BY MAP

- VIEW BY LIST

- Find Flashcards

- Why It Works

- Tutors & resellers

- Content partnerships

- Teachers & professors

- Employee training

Brainscape's Knowledge Genome TM

Entrance exams, professional certifications.

- Foreign Languages

- Medical & Nursing

Humanities & Social Studies

Mathematics, health & fitness, business & finance, technology & engineering, food & beverage, random knowledge, see full index, kiribati case study flashcards preview, a level geography - aqa > kiribati case study > flashcards.

What is Kiribati’s background

-One of the worlds lowest-lying nations - first to experience impacts of climate change - 33 islands - 4m above sea level

What are the impacts on kiribati

- abandoned / submerged villages

- salt water contamination

- Displacement and separation of communities

- King tides - extreme high tides

What are the responses to Kiribati

- Need global action on carbon emissions - they’ve grown impatient

- Sending citizens to AUS to get training - MIGRATION WITH DIGNITY

- Building sea walls

- Mangrove trees put in to protect sand

What is the impact to Kiribati

- Mass migration to the Capital - overcrowding (already had issues), pollution and disease

- Loss of identity - loss of cultural and spiritual land

Decks in A level Geography - AQA Class (22):

- Coasts Theme 1

- Coasts Theme 2 Waves

- Coasts Theme 2 Tides

- Coasts Theme 2 Currents

- Coasts Theme 2 Hec And Lec

- Coasts Theme 2 Geomorphological

- Coasts Theme 2 Erosion + D EP Osition + Transportation

- Coasts Theme 2 Geology

- Coastal Landscapes

- Estuarine Mudflats/Saltmarsh Environments

- Eustatic And Isostatic Sae Level Changes

- Submergent And Emergent Features

- Recent And Predicted Climate Change

- Kiribati Case Study

- Pevensey Bay

- Bognor Regis

- West Wittering

- The Sundarbans

- Changing Places Theme 1

- Corporate Training

- Teachers & Schools

- Android App

- Help Center

- Law Education

- All Subjects A-Z

- All Certified Classes

- Earn Money!

- 0 Shopping Cart

Geography Case Studies

All of our geography case studies in one place

Coastal Erosion

Use the images below to find out more about each case study.

The Holderness Coast

The Dorset Coast

Happisburgh

Coastal Management

Sandscaping at Bacton, Norfolk

Coastal Realignment Donna Nook

Coastal Realignment Medmerry

Coastal Deposition

Spurn Point

Blakeney Point Spit

Earthquakes

Amatrice Earthquake Case Study

Chile Earthquake 2010

Christchurch Earthquake

Haiti Earthquake

Japan Earthquake 2011

L’Aquila Earthquake

Lombok Indonesia Earthquake 2018

Nepal Earthquake 2015

Sulawesi, Indonesia Earthquake and Tsunami 2018

New Zealand 2016

Malaysia Causes of Deforestation

Malaysia Impacts of Deforestation

Alaska Case Study

Epping Forest Case Study

Sahara Desert Case Study

Svalbard Case Study

Thar Desert Case Study

Western Desert Case Study

Energy Resources

Chambamontera Micro-hydro Scheme

Extreme Weather in the UK

Beast from the East Case Study

Storm Ciera Case Study

Food Resources

Almería, Spain: a large-scale agricultural development

The Indus Basin Irrigation System: a large-scale agricultural development

Sustainable food supplies in a LIC – Bangladesh

Sustainable food supplies in a LIC – Makueni, Kenya

Landforms on the River Tees

Landforms on the River Severn

Indus River Basin (CIE)

River Flooding

Jubilee River Flood Management Scheme

Banbury Flood Management Scheme

Boscastle Floods

Kerala Flood 2018

Wainfleet Floods 2019

The Somerset Levels Flood Case Study

UK Floods Case Study November 2019

River Management

The Three Gorges Dam

Mekong River

The Changing Economic World

How can the growth of tourism reduce the development gap? Jamaica Case Study

How can the growth of tourism reduce the development gap? Tunisia Case Study

India Case Study of Development

Nigeria – A NEE

Torr Quarry

Nissan Sunderland

The London Sustainable Industries Park (London SIP)

Tropical Storms

Beast from the East

Hurricane Andrew

Cyclone Eline

Cyclone Idai Case Study

Typhoon Haiyan 2013

Hurricane Irma 2017

Typhoon Jebi 2018

Hurricane Florence 2018

Typhoon Mangkhut 2018

Urban Issues

Birmingham – Edexcel B

Urban Growth in Brazil – Rio de Janeiro

Urban Growth in India – Mumbai

Urban Growth in Nigeria – Lagos

London – A Case Study of a UK City

Inner City Redevelopment – London Docklands

Sustainable Urban Living – Freiburg

Sustainable Urban Living – East Village

Sustainable Urban Transport Bristol Case Study

Bristol – A major UK city

Volcanic Eruptions

Eyjafjallajokull – 2010

Mount Merapi – 2010

Mount Pinatubo – 1991

Sakurajima Case Study

Nyiragongo Case Study

Water Resources

Hitosa, Ethiopia – A local water supply scheme in an LIC

The South-North Water Transfer Project, China

Wakal River Basin Project

Lesotho Large-Scale Water Transfer Scheme

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Please Support Internet Geography

If you've found the resources on this site useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Search Internet Geography

Top posts and pages.

Latest Blog Entries

Pin It on Pinterest

- Click to share

- Print Friendly

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Find out how we are supporting data gathering in the low-lying island chain of Kiribati to help protect 115,000 people from coastal inundation. As we face the unprecedented effects of climate change, so too do our oceans. Sea level rise, in particular, poses an imminent threat to our precious marine environments - a threat that will have life ...

[3] Kiribati National Statistics Office (2020). Kiribati Population and Housing Census Provisional Results, URL: https://kir20phc.prism.spc.int/ (accessed 16 May 2021). [4] Donner, S. D. and S. Webber (2014). Obstacles to climate change adaptation decisions: a case study of sea-level rise and coastal protection measures in Kiribati.

Human-caused climate change has caused our oceans to rise. This can have disastrous effects on coastal communities and coastal ecosystems. Kiribati is predicted to be one of the countries most impacted by climate change, in part to its vulnerability to sea-level rise. It is less than 2 meters above sea level.

Jordan Shamoun, Arlene Chen, Jonah Taranta, Eunice Rodriguez, Alexey Tarasov

Environmental Social Sciences and Geography, University of Freiburg, Germany ABSTRACT Reducing vulnerabilities is at the core of climate change adaptation interventions. This goal is usually ... part of the Kiribati case study, before moving to a review of recent research that problematizes knowledge-power relations in climate change adaptation ...

The president of Kiribati, Tong has become best known for admonishing wealthy countries for burning through fossil fuels at the expense of low-lying atolls scattered across the equatorial Pacific. On Kiribati's 33 islands, the average land height rises little more than six feet (about 2 meters) above the sea.

Impact Assessment of Storm Surge and Climate Change-Enhanced Sea Level Rise on Atoll Nations: A Case Study of the Tarawa Atoll, Kiribati. ... High-resolution Geography (GSHHG), Version 2.3.7, June 15,

funded climate change adaptation projects, using a case study of sea-level rise and coastal protection measures in Kiribati. The central equatorial Pacific country (Fig.1)is home to the Kiribati Adaptation Project (KAP), the first climate change adaptation project administered by the World Bank. Since the World Bank is the trustee of the

They go on to assess the landforms that are created as a result of sea level change, and evaluate the case study of Kiribati (links to resources on final slide). This lesson works well in conjunction with the Oxford AQA Geography A Level & AS Physical Geography Student Book (Ross, Bayliss, Collins, and Griffiths, 2016).

KIRIBATI VULNERABILITY TO ACCELERATED SEA-LEVEL RISE: A PRELIMINARY STUDY 2/ /(5 {; Ocean;r-Unconfined aquifer ... Department of Geography, University of Wollongong Wollongong, Australia ard ... Case studies 49 8.1. Case study 1 : Betio 49 8.2. Case study 2: Buota 51 8.3. Case study 3: Buariki 55

The Republic of Kiribati, a group of 33 Pacific Islands home to 100,000 people, sits on average six feet above sea level. Scientists believe that at some point this century, these islands may ...

case study of kiribati - geography. 19 terms. IslaI2. Preview. A Level Geography, Coasts, Kiribati Islands. 8 terms. benjamwarren. Preview. GEo - CSMP - LYMPSTONE. 23 terms. ellakelleralways. Preview. globalisation . 86 terms. jolieskye05. Preview. Evaluate the view that rates of coastal recession are largely controlled by geological factors (20)

Climate change is threatening the livelihoods of the people of tiny Kiribati, and even the island nation's existence. The government is making plans for the island's demise. By Mike Ives (July 2, 2016) TARAWA, Kiribati — One clear bright day last winter, a tidal surge swept over an ocean embankment

A. CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS. Climate is changing and Earth's temperature is increasing.34 According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Earth's temperature has increased 1.4°F in the last century, and it is estimated that it will rise an additional 2°F to 11.5°F in the next century.35. 30 Id.

There is no safe place. The option is to give the people their preference.". The Kiribati public are largely in favour of staying and fighting for their survival, Maamau said. "They say, 'We ...

Kiribati is an island nation located in Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. It is made up of 32 island atolls and one small coral island spread out over 1.3 million square miles. The country itself, however, has only 313 square miles (811 sq km) of area. Kiribati is also along the International Date Line on its easternmost islands and it straddles ...

The systematic warming of the planet is directly causing global mean sea level to rise in two primary ways: (1) mountain glaciers and polar ice sheets are increasingly melting and adding water to the ocean, and (2) the warming of the water in the oceans leads to an expansion and thus increased volume. Global mean sea level has risen approximately 210-240 millimeters (mm) since 1880, with ...

Bangladesh A level Geography Coast Case Study. 12 terms. lucasmeggyesi. Preview. Kiribati case study. 5 terms. maddybegg. Preview. Religions of the World Test. Teacher 24 terms. nicole_clarkson24. Preview. The Global Tapestry (1200-1450) 49 terms. Lilli0828. Preview. Terms in this set (14) How many atolls is it made from?

3rd adaption strategy that kiribati uses to manage sea level rise -. where have sea walls been put in place. Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like what problems is kiribati facing, kiribati causes of increasing coastal erosion and flooding - 3 points, effect of increased wave heights and frequency and more.

A. -One of the worlds lowest-lying nations - first to experience impacts of climate change - 33 islands - 4m above sea level. 2. Q. What are the impacts on kiribati. A. abandoned / submerged villages. salt water contamination. Displacement and separation of communities.

Planting mangroves and education on their importance Migration with dignity - Gradually moving the entire population to other land masses - Australia and New Zealand Sea walls Water tanks so drinking water can't be contaminated during flooding. Prohibiting taking sand and gravel from the beaches. Moving back to farming traditional crops Fiji government offered their help when the Kiribati ...

Share this: Geography Case Studies - A wide selection of geography case studies to support you with GCSE Geography revision, homework and research.

State sea level surrounding the Kiribati islands. Sea levels are rising by 12mm per year (4 times more than global average) What are the problems as a result of sea level rise? 1. Most places are predicted to disappear below sea level rise in the next 50 years 2. Rising sea levels result in salinization 3.