- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Top 10 verse novels

From Homer’s classical epic to Kae Tempest’s mythic struggles in modern London, these books show that poetry can be more immediate than prose

Verse novels have been with us for millennia, yet when you publish one, many are surprised by your breach of the prose-novel tradition and also somewhat fearful of trying something new.

It is curious how we love poems as children, and as adults drag them out for weddings and funerals – and yet in our day-to-day lives feel poetry doesn’t belong to us. When I speak at events the overwhelming refrain from my audiences is that poetry is difficult and makes readers feel ignorant. But the verse novel, well that’s something slightly different. As a poet I write with melody in mind, but as a novelist, story is king, so if showing off with language will muddy my reader’s ability to engage with the characters, I scratch it out and try again, and most verse novelists I read do the same.

If you haven’t read verse before here are some of my very favourites, and in the same vein as my new book Here Is the Beehive , most of my picks are short novels that can be read in a couple of sittings. Verse doesn’t require the same-sized canvas as prose; sparsity is what lends these novels their magic, the white spaces on the page revealing almost half of what the chosen words express and sometimes that space says even more.

1. Charlotte by David Foenkinos Translated from the French by Sam Taylor, Charlotte is an international bestseller. Though the verse is not particularly complex or gruelling, its simple and unsentimental tone makes it all the more heartbreaking. A story about loss and resilience, set in Nazi Germany, Charlotte is an inspiring novel made all the more powerful by being based on a true story about the life of a relatively unknown artist. The ending comes as no surprise, but I still found myself devastated by it.

2. The Long Take by Robin Robertson Shortlisted for the Man Booker prize in 2018, this is a novel I read in one gulp, realising as I did that the verse form I had long used to write for children absolutely could work for adults. I then listened to the audiobook, and hearing the melody of the poet’s voice at work (though read by an actor) left me in awe. It is an overwhelming story, using dialogue to stunning effect, about Walker, a war veteran moving between New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco, suffering from PTSD and unable to return to his home, and his lost love, in Nova Scotia. I refer to it when I want to remember how verse novels should be written and how much harder I need to be working.

3. The Iliad by Homer, translated by Robert Fagles I have had this translation on my bookshelf for years, and I suppose I thought that if it remained there, a couple of Post-it notes in its pages, I could pretend to myself and others that I had read it in its entirety. But I had not, and am ashamed to admit I did not finally succumb until I was overwhelmed by the The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker . The story opens near the end of the 10-year war between the Greeks and Trojans, men and Gods battling for power, the legend of Achilles at its core. And this translation is entirely modern, with helpful footnotes throughout, so you won’t need a PhD to understand it. May take longer than a couple of sittings, however!

4. Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse I was a middle-school teacher in New Jersey when a colleague handed me a copy of Hesse’s Newbery medal-winning novel and suggested I teach it to the kids. A coming-of-age story set during the Oklahoma dust bowl of the 1930s, this centres on 14-year-old Billie Jo and her navigation of grief. This I was on board with, but when I saw the layout I practically spat out my bagel. I had been a teacher for years and knew one thing: teenagers would not endure an entire novel made up of poems. Teenagers hated poetry. Ah, how wrong I was – the students loved it. And less than six months later I began my own project in verse, which later turned into my debut novel.

5. The Marlowe Papers by Ros Barber The most incredible thing about Barber’s phenomenal novel, which supposes Christopher Marlowe did not die in a brawl but lived and wrote under the name William Shakespeare, is that it is written entirely in iambic pentameter. It’s original, clever and gripping – I don’t know how she pulled it off.

6. Love That Dog by Sharon Creech This slip of a thing will be devoured by your children, and then by you, in mere minutes. It is the story of a boy who cautiously begins to engage with poetry, and his own feelings, through his homework assignments. If you aren’t sure poetry speaks to you any longer, let Creech heal you by reminding you that it is everywhere and can be accessed by anyone. A fabulous, fun novel you’ll read again and again.

7. Booked by Kwame Alexander I shudder ever so slightly when a new YA verse novel is presented to me, fearing it will be nothing more than cut-up prose. Kwame Alexander, however, is a true master of the form, using sophisticated poetic devices throughout each of his novels to propel story and engage even the most reluctant teen reader. If I’m forced to choose a favourite from his oeuvre it’ll have to be this story about a football-obsessed boy who’s troubled by his parents’ separation. Alexander is already a superstar stateside, and on his way to snapping up the teen verse market here, too.

8. Brand New Ancients by Ka e Tempest I’ve seen Tempest perform twice and both times came away altered and gibbering slightly. They communicated on some ethereal level that defies explanation as the work is accessible, relatable and without pretence. This is a story about violence and love, which confronts the reader with what it means to be human in all its agonising complexity. If you can, listen to the audiobook, too.

9. Citizen by Claudia Rankine This book pushes form to create a kind of documentary novel about injustice in the US. As a white reader I felt exposed, and rightly so. As a poet, I felt jealous; the text’s refusal to be defined and the way it forces the reader to constantly adjust to its shifting form makes this a masterfully brave and important piece of literature.

10. The Golden Gate by Vikram Seth This list would not be complete without Seth’s prize-winning first novel. It was inspired by the poetic structure of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin and is written in the iambic tetrameter he used. Like The Marlowe Papers, this is a triumph simply for managing to sustain its form throughout (whereas most of the other verse novels I have included are written in free verse). Set in the 1980s in Silicon Valley, the story opens with the successful but lonely John Brown placing a lonely hearts advertisement. The novel trots along at quite a pace, a plethora of characters coming into and out of the narrative, with themes from sexuality to war being explored. This is a chunkier read than the others but certainly worth the effort.

Here Is the Beehive by Sarah Crossan is published by Bloomsbury. To order a copy, go to guardianbookshop.com .

- Vikram Seth

- Robin Robertson

- Kae Tempest

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Definition of Verse

The literary device verse denotes a single line of poetry. The term can also be used to refer to a stanza or other parts of poetry.

Generally, the device is stated to encompass three possible meanings, namely a line of metrical writing, a stanza, or a piece written in meter . It is important to note here that the term “verse” is often incorrectly used for referring to “poetry” in order to differentiate it from prose .

Types of Verse

There are generally two types of verse, namely free verse and blank verse .

A free verse poem has no set meter; that is to say there is no rhyming scheme present, and the poem doesn’t follow a set pattern. For some poets this characteristic serves as a handy tool for the purpose of camouflaging their fluctuation of thoughts, whereas others think that it affects the quality of work being presented.

Example #1 Free Verse

After the Sea-Ship (By Walt Whitman )

“After the Sea-Ship—after the whistling winds; After the white-gray sails, taut to their spars and ropes, Below, a myriad, myriad waves, hastening, lifting up their necks, Tending in ceaseless flow toward the track of the ship: Waves of the ocean, bubbling and gurgling, blithely prying, Waves, undulating waves—liquid, uneven, emulous waves, Toward that whirling current, laughing and buoyant, with curves, Where the great Vessel, sailing and tacking, displaced the surface…”

As can be seen from the stanza quoted above, there is an absence of rhyming effect and structure in each verse.

Example #2 Free Verse

Fog (By Carl Sandburg)

“The fog comes on little cat feet. It sits looking over harbor and city on silent haunches and then moves on.”

Here, it can be observed that there is no form or rhyme scheme present in the verse.

- Blank Verse

There is no rhyming effect present in a blank verse poem. However, it has an iambic pentameter . It is usually employed for presenting passionate events, and to create an impact on the reader. Shakespeare was an ardent user of blank verse.

Example #1 Blank Verse

Furball Friend (Author Unknown)

“Sweet pet by day, hunter by night . She sleeps, she eats, she plays. My feet, caught in white paws. She’s up the fence, watching her prey – a bird. Poor thing, better run quick, ’cause watch, she’ll pounce! She’ll sweetly beg for fuss, but don’t be fooled. ‘Cause one minute she’ll purr and smile, then snap! She’ll spit and hiss – and oh – surprise! A mouse. He’s dead. A gift. Retracts her claws. Miaow! Figure of eight between my legs, looks up at me and purrs. The sound pulls my heartstrings. Her big blue eyes like dinner plates – so cute. Cunning she is, she knows I can’t resist. Curling up tight, we sleep entwined as one. Despite her quirks, I would not change a claw of her. Cheeky Sammy: my snow -white queen.”

The poem quoted above depicts the use of blank verse throughout. Here, it is important to note that there is no rhyming scheme present. Also, it can be seen that there is a presence of iambic pentameter throughout the verses.

Short Examples of Verse

- The difference between ambience and silence , When nature speaks, you are silent. (Blank Verse)

- Words limit the silence Upsetting the peace Of infinite tranquility… (Blank Verse)

- Flower in a faraway valley, Wind carries it away as butterflies move around. (Blank Verse)

- A ship sailor from the West lands on the land between the mountains and the seas. (Blank Verse)

- Cold cold, Winter sticks to the trees and the seas. (Free Verse)

- Just off the road to city, Twilight bounds swiftly froth on the plants. (Free Verse)

- What thought I’d think tonight, for I walk down the street Under thick trees with a self-conscious mind looking at full moon. (Free Verse)

- The sea is silent to-day, The tides are high, the moon sparks Upon the curved stairs; on the coast The light shines and goes; the cliffs stand, Gleaming and huge, out on a tranquil shore. (Free Verse)

- A land filled with ice Covered by the arches of sky, Hurls into eternity. (Free Verse)

- Many stars tonight And their memory. Yet how much room is there for quiet clouds? (Free Verse)

- Forgetfulness is a melody That frees itself from measure and beat, wanders. (Free Verse)

- Above the ruffles of surf The sun sparkles on the waves, And the waves carry thunder on the shore. (Free Verse)

- Standing out vibrantly in the garden A dream flower blossoms. (Free Verse)

- Beneath the earthly and cosmos sky, Floral butterfly ascends towards showers. (Free Verse)

- I entered the forest for a walk, I cross by many trees with overhead shades With small beam of light straining through them. (Free verse)

Examples of Verse in Literature

Example #1: fairies and fusiliers (by robert graves).

“I now delight In spite Of the might And the right Of classic tradition, In writing And reciting Straight ahead, Without let or omission… Because, I’ve said, My rhymes no longer shall stand arrayed No! No! My rhymes must go Twinkling, frosty, Will-o’-the-wisp-like, misty…”

This is an excellent example of a free verse poem, as it’s free from artificial expression of poetry. Without any poetic restraints, it gives a natural flow of reading experience.

Example #2: Feelings, Now (By Katherine Foreman)

“Some kind of attraction that is neither Animal , vegetable, nor mineral, a power not Solar, fusion, or magnetic… And find myself sitting there.”

This is another instance of free verse poetry that does not follow any rules, nor any rhyme scheme. However, it still gives an artistic and creative expression.

Example #3: Thanatopsis (By William Cullen Bryant)

“To him who in the love of Nature holds A various language; for his gayer hours She has a voice of gladness, and a smile…”

The above mentioned poem presents an example of blank verse that adds cadence and a subtle rhythm , mimicking the pattern of the language that is audible in nature.

Example #4: Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art (By John Keats)

“ Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art — Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night And watching, with eternal lids apart, Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,…”

This is an example of a rhymed verse poem that has used an ABAB rhyme scheme, which means the first and third, and the second and fourth lines rhyme with one another.

Example #5 Daffodils (By William Wordsworth)

“ I wandered lonely as a cloud That floats on high o’er vales and hills, When all at once I saw a crowd, A host, of golden daffodils; Beside the lake, beneath the trees, Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.”

The above quoted stanza from William Wordsworth’s poem Daffodils presents to the reader various examples of verse. It can be noted here that the use of the tool of verse adds a scenic element to the structure of poetry.

Function of Verse

The use of verse in a piece of writing has a pleasing effect on the reader’s mind. It is usually employed in poetry writing. The poets make use of the tool of verse in order to provide their poetry with a desired structure. It serves as an avenue through which writers project their ideas in the form of a composition having rhyme, rhythm, and deeper meanings. The device provides the writer with a framework for poetry writing.

Related posts:

- 10 Best Blank Verse Poems

- 15 Best Shakespeare’s Blank Verse

- Sonnet 17: Who Will Believe My Verse in Time to Come

- 10 Famous Free-Verse Poems

- 10 Best Free-Verse Poem Examples For Kids

- 15 Famous Short Free-Verse Poems

Post navigation

10 Essential Verse Forms Everyone Should Know

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

Learning the different verse forms that poets have used for centuries might seem like a daunting task, but in this article we’ve picked ten of the most popular and enduring verse forms, and offer a short introduction to each of them. So, if you’ve always wanted to know more about different verse forms, and would like to be able to tell a sonnet from a ballad, look no further.

Let’s start with one of the most widely used and enduring verse forms in all of literature. Originating in Italy in the thirteenth century (it was actually a little-known Sicilian poet named Giacomo da Lentini, rather than the later and more famous Petrarch, who invented this form), the sonnet (almost) always takes 14 lines and comes in a variety of forms, though the two most famous are the English or Shakespearean sonnet (three quatrains of alternate rhymes, i.e. abab cdcd efef , followed by a concluding rhyming couplet, gg ) and the Italian or Petrarchan sonnet (an octave rhymed abbaabba and a sestet that can be rhymed a number of ways, though often cdcdcd ).

The beauty of the sonnet form is that it’s just long enough to explore/argue an issue or work through a mental or emotional conflict, but will never outstay its welcome. Some poets have innovated with the sonnet form in surprising way: see our longer introduction to the sonnet here. Here is a fine example of the sonnet form by its earliest English practitioner, Sir Thomas Wyatt:

Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind, But as for me, hélas , I may no more. The vain travail hath wearied me so sore, I am of them that farthest cometh behind. Yet may I by no means my wearied mind Draw from the deer, but as she fleeth afore Fainting I follow. I leave off therefore, Since in a net I seek to hold the wind. Who list her hunt, I put him out of doubt, As well as I may spend his time in vain. And graven with diamonds in letters plain There is written, her fair neck round about: Noli me tangere , for Caesar’s I am, And wild for to hold, though I seem tame.

We all know about haiku: the Japanese verse form comprising three lines and a total of 17 syllables, i.e. 5 syllables in the first line, 7 in the second line, and 5 in the third? This actually only tells part of the story (there is a difference between our understanding of ‘syllables’ based on the original Japanese formula), and haiku, strictly, should be about nature – we explore the form in more detail here .

Strictly speaking, ballad metre is verse in quatrains comprising lines of alternating tetrameter (four feet) and tetrameter (three feet), rhymed abcb (rather than abab , for instance). A typical example is the opening stanza from the anonymous ballad ‘Sir Patrick Spens’:

The King sits in Dunferline toun, Drinkin the blude-reid wine ‘O whaur will A get a skeely skipper Tae sail this new ship o mine?’

Ballads usually tell a story, so they’re a form of narrative poem, but written in the abcb quatrains illustrated above. However, ballads were originally composed to be sung and danced to, with musical accompaniment: the word ‘ballad’ comes from the Latin ballare , meaning ‘to dance’.

4. Villanelle.

This very restrictive verse form presents a challenge to the poet, since it hinges on the repeated use of two refrains. As its name suggests, the villanelle is a French verse form, yet this French form took its name from an Italian one: the word derives from villanella, a form of Italian part-song which originated in Naples in the sixteenth century.

Yet English poetry, rather than French or Italian, has become the naturalised home of the villanelle. This intriguing verse form comprises 19 lines made up of five tercets (three-line stanzas) and a concluding quatrain.

As the Oxford English Dictionary summarises it, ‘The first and third lines of the first stanza are repeated alternately in the succeeding stanzas as a refrain, and form a final couplet in the quatrain.’

An example of how the villanelle works in practice can be seen in an early example in English, Oscar Wilde’s ‘Theocritus: A Villanelle’ from 1890:

O singer of Persephone! In the dim meadows desolate Dost thou remember Sicily?

Still through the ivy flits the bee Where Amaryllis lies in state; O Singer of Persephone!

Simaetha calls on Hecate And hears the wild dogs at the gate; Dost thou remember Sicily?

And so on. Although it remains a niche form, some fantastic poems have been written using the villanelle form in the twentieth century, including W. H. Auden’s ‘ If I Could Tell You ’, William Empson’s ‘ Missing Dates ’, and Dylan Thomas’s ‘Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night’ . We have a fuller history of the villanelle here .

5. Ottava Rima.

The term ottava rima is Italian, as is this verse form, comprising eight-line stanzas rhymed abababcc . Like the heroic couplet below, it was first used to write about grand, heroic things; but later, it was used, especially in English, for mock-heroic poems, most famously Byron’s long narrative poem Don Juan , where the rhymes were also often comically polysyllabic (as with ‘satire, he’ and ‘flattery/battery’ here):

I am no flatterer – you’ve supped full of flattery: They say you like it too – ’tis no great wonder: He whose whole life has been assault and battery, At last may get a little tired of thunder; And swallowing eulogy much more than satire, he May like being praised for every lucky blunder; Called ‘Saviour of the Nations’ – not yet saved, And Europe’s Liberator – still enslaved.

6. Sestina.

The sestina is great fun to write, though, as Stephen Fry acknowledges in The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking the Poet Within , hard to explain. But the gist is that you have six-line stanzas – six of them in all – followed by a concluding three-line stanza. The ‘rhymes’ at the ends of the lines are not rhymes at all; instead, you have six words – Fry calls them ‘hero’ words – which you repeat at the ends of lines, once each for each stanza, but at different points in the stanza.

We’ve gathered together some examples of the sestina form here which help to explain how the form works. Here is the opening stanza from one of the most famous sestinas in English, by Sir Philip Sidney:

Ye goatherd gods, that love the grassy mountains, Ye nymphs which haunt the springs in pleasant valleys, Ye satyrs joyed with free and quiet forests, Vouchsafe your silent ears to plaining music, Which to my woes gives still an early morning, And draws the dolor on till weary evening …

7. Rhyme Royal.

Used by Geoffrey Chaucer for his long narrative poem Troilus and Criseyde , rhyme royal is very similar to ottava rima, except it’s seven lines long rather than eight, and rhymed ababbcc . The verse form was later used by Tudor poets, such as Sir Thomas Wyatt, whose ‘ They Flee from Me ’ is a superlative example of what the form can do:

They flee from me that sometime did me seek With naked foot, stalking in my chamber. I have seen them gentle, tame, and meek, That now are wild and do not remember That sometime they put themself in danger To take bread at my hand; and now they range, Busily seeking with a continual change.

8. Heroic Couplet.

The ‘heroic couplet’ is the name given to rhyming couplets written in iambic pentameter . They’re called ‘heroic’ because they were used in translations of epic poetry into English – poems about heroes from classical mythology.

Heroic couplets thus suggest grandeur and ‘weightiness’, although the flipside of this is that they have sometimes been used to create the opposite effect: for instance, Alexander Pope, in his mock-heroic poem The Rape of the Lock , uses heroic couplets to summon the lofty world of gods and goddesses … in a poem about an upper-class woman having a lock of her hair cut off:

This Nymph, to the destruction of mankind, Nourish’d two Locks, which graceful hung behind In equal curls, and well conspir’d to deck With shining ringlets the smooth iv’ry neck. Love in these labyrinths his slaves detains, And mighty hearts are held in slender chains.

Heroic couplets were also popular in the eighteenth century – before the advent of Romanticism brought in a preference for blank verse (see below) – since they suggested order and neatness, which neoclassical or ‘Augustan’ poets like Pope, Samuel Johnson, and others wanted to bring to poetry. Johnson in particular wrote verse satires and didactic poems using heroic couplets.

9. Blank Verse.

Blank verse is unrhymed iambic pentameter, and is not to be confused with free verse (which is unrhymed but doesn’t have a regular metre). Of all the verse forms listed here, with the exception of free verse below, blank verse is the one that comes the closest to the natural rhythms of English speech, which is what helped to make it so useful to writers of verse dramas, such as Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, John Webster, and, later, T. S. Eliot.

Here’s a famous example from Shakespeare:

To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles And by opposing end them. To die—to sleep, No more; and by a sleep to say we end The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to: ’tis a consummation Devoutly to be wish’d. To die, to sleep; To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub: For in that sleep of death what dreams may come …

You’ll notice that blank verse has a rhythm (iambic pentameter goes ti-TUM ti-TUM ti-TUM ti-TUM ti-TUM), but no rhyme. We explore blank verse in more depth here .

10. Free Verse.

As mentioned above, free verse is different from blank verse: it’s unrhymed, but also has no regular metre – and doesn’t even need regular line lengths. This gives the poet far greater freedom, as this short 1908 poem from T. E. Hulme shows:

A touch of cold in the Autumn night – I walked abroad, And saw the ruddy moon lean over a hedge Like a red-faced farmer. I did not stop to speak, but nodded, And round about were the wistful stars With white faces like town children.

Note the lines can be very short (like that second one) or much longer (the third), there is no rhyme at the ends of the lines, and no set rhythm. However, much free verse does still have a loose rhythm. It just isn’t rigidly enforced throughout the poem. It’s more like a rough beat for the poet to keep coming back to. We’ve written a more in-depth introduction to free verse .

4 thoughts on “10 Essential Verse Forms Everyone Should Know”

The ode less travvelled is fantastic. Another very good book is Meter and meaning, by T. Carper and D Attridge. It is more specifically on meter rather than form, but I recommend it: it is not difficult and doesn’t get lost in complicated terminology.

Good shout on the Carper and Attridge. There’s an art to talking about metre without getting frustratingly over-technical, and that book gets it just right.

I teach English lang. and lit in Italy, and most of my colleagues either only cover Iambic pentameter (well, that’s a lot of course) or worry about teaching terminology the way the Latin lit teacher do it, without really working on how meter works. Meter and meaning helped me find a way to do that, and confirmed in my idea that once you know binary meters in English you’ve got what you need.

Very helpful. You omitted to mention that most English sonnets are written in pentameters, but I’m glad you haven’t repeated the heresy that all sonnets have to have lines of only ten syllables. The rule for sonnet lines, as for all pentameters, is simply that there have to be five STRESSED syllables. As a simple examination of Shakespeare’s and Milton’s sonnets shows. Ten syllables may be a useful discipline but it is NOT compulsory

Comments are closed.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

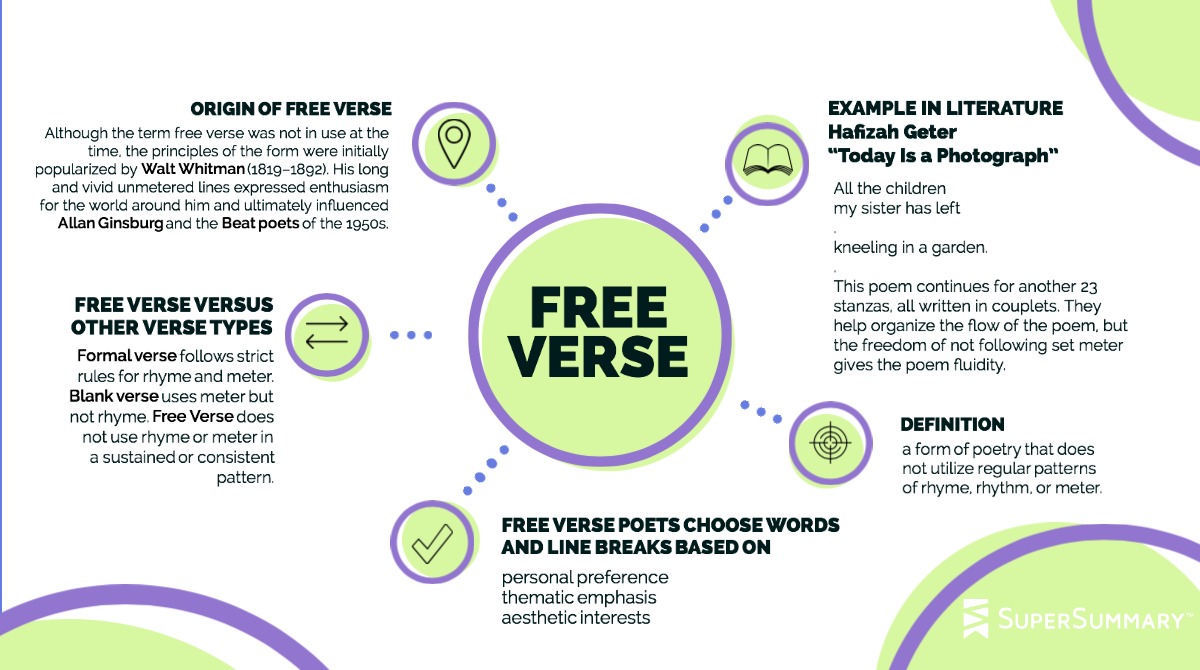

Free Verse Definition

What is free verse? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Free verse is the name given to poetry that doesn’t use any strict meter or rhyme scheme . Because it has no set meter, poems written in free verse can have lines of any length, from a single word to much longer. William Carlos Williams’s short poem “The Red Wheelbarrow” is written in free verse. It reads: “so much depends / upon / a red wheel / barrow / glazed with rain / water / beside the white / chickens.”

Some additional key details about free verse:

- The opposite of free verse is formal verse , or poetry that uses both a strict meter and rhyme scheme.

- Not only do poets writing in free verse have the freedom to write unrhymed lines of any length, but they also often use enjambment in unconventional ways, inserting line breaks in the middle of sentences and even in the middle of words (such as “wheelbarrow” and “rainwater”).

- Walt Whitman is often said to be the father of free verse. It’s true that he popularized this type of poetry, but in fact there were others who had written unrhymed, unmetered poetry before him.

- Most poets writing today write in free verse.

Free Verse in Depth

In order to understand free verse in more depth, it’s helpful to have a strong grasp of a few other literary terms related to poetry. We cover each of these in depth on their own respective pages, but below is a quick overview to help make understanding blank verse easier.

- Formal verse : Poetry with a strict meter (rhythmic pattern) and rhyme scheme.

- Blank verse : Poetry with a strict meter but no rhyme scheme.

- Free verse: Poetry without any strict meter or rhyme scheme.

- Stress : In poetry, the term stress refers to the emphasis placed on certain syllables in words. For instance, in the word “happily” the emphasis is on the first syllable (“hap”), so “hap” is the “stressed” syllable and the other two syllables (“pi” and “ly”) are “unstressed.”

- Foot : In poetry, a "foot" refers to the rhythmic units of stressed and unstressed syllables that make up lines of meter . For example, an iamb is one type of foot that consists of one unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable, as in the word "De- fine ."

- Meter : A pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables that defines the rhythm of lines of poetry. Poetic meters are named for the type and number of feet they contain. For example, iambic pentameter is a type of meter that contains five iambs per line (thus the prefix “penta,” which means five).

Free Verse, Meter, and Rhyme

Poems written in free verse are characterized by generally not using meter or rhyme , but that doesn’t mean that they can never include meter or rhyme. In fact, poets writing in free verse often do include a bit of meter or rhyme in their poetry. Saying that a poem is “free verse” just means that the use of meter or rhyme is not extensive or consistent in the poem.

For instance, TS Elliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” is a famous free verse poem in which many lines end in rhyme, but those rhymes don't follow any particular pattern (or rhyme scheme ) and the poem follows no particular meter. Similarly, Walt Whitman was known to occasionally lapse in and out of using meter in his unrhymed poetry—but for the most part his poems don’t make use of meter, so they’re still considered free verse.

Stanzas in Free Verse

While some types of formal verse have specific requirements for the length or number of stanzas , free verse has no such restrictions. A poet writing in free verse may use stanzas of regular length consistently throughout their poem, though more often than not the length of stanzas in free verse poems varies at least somewhat throughout the poem—which is just to say that they don't follow any rule in particular.

Free Verse and Prose Poems

Since free verse is, by definition, free of formal constraints, there aren’t any specific types or “forms” of free verse poetry (as there are with formal verse)—except for one. Prose poems are a specific type of free verse poetry that doesn’t have any line breaks, and which therefore take the form of paragraphs.

Free Verse Examples

T.s. eliot's "the love song of j. alfred prufrock".

This famous free verse poem by T.S. Eliot rhymes, but not according to any particular pattern, and it doesn’t use meter (note how varied the line lengths are). Here's an excerpt:

Let us go then, you and I, When the evening is spread out against the sky Like a patient etherized upon a table; Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets, The muttering retreats Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells: Streets that follow like a tedious argument Of insidious intent To lead you to an overwhelming question ... Oh, do not ask, “What is it?” Let us go and make our visit.

Walt Whitman's "When Lilacs Last In Dooryard Bloom’d"

Walt Whitman is best known for writing free verse, but he often injected metered lines into his free verse sporadically. Here the second line is a near-perfect line of dactylic hexameter (six feet of stressed - unstressed - unstressed syllables) that appears seemingly out of the blue. The lines before and after this example are not dactylic at all.

I fled forth to the hiding receiving night that talks not, Down to the shores of the wa ter , the path by the swamp in the dim ness , To the solemn shadowy cedars and ghostly pines so still.

E.E. Cummings's "[i carry your heart with me(i carry it in]"

E.E. Cummings was famous for pushing the boundaries of what many readers would have even recognized as poetry at the time when he was writing. Written in free verse, the formal inventiveness of his poetry bucks many other poetic conventions as well, including the use of proper punctuation and normal rules of indentation. [i carry your heart with me(i carry it in] is one of his more well-known poems, and it uses rhyme irregularly throughout. This excerpt contains the poem's first two stanzas:

i carry your heart with me(i carry it in my heart)i am never without it(anywhere i go you go,my dear;and whatever is done by only me is your doing,my darling) i fear no fate(for you are my fate,my sweet)i want no world(for beautiful you are my world,my true) and it’s you are whatever a moon has always meant and whatever a sun will always sing is you

William Carlos Williams's "This Is Just To Say"

Williams's writing is a good example of the incredibly spare, restrained style that can be achieved through free verse—in this case, by using very short lines to heighten language that might otherwise seem perfectly ordinary and unremarkable. Here are the first two stanzas of his famous poem, "This is Just to Say":

I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast

Why Do Writers Use Free Verse?

Generally speaking, formal verse gradually fell out of fashion with poets over the course of the 20th century. This was in part because, as literacy levels rose, meter and rhyme (which originated as formal features to aid in memorization and comprehension) no longer seemed necessary.

But free verse was also attractive to poets simply because it lacked the restrictions and constraints imposed on poetry by meter and rhyme, and therefore left it to the poet to determine the form his or her poem would take—and to invent his or her own restrictions and constraints. Today, it could be said that the main reason most poets write in free verse is simply that it has become the norm, in much the same way that formal and blank verse were once the norm.

While free verse lacks some of the restraints of formal and blank verse, it still involves all the elements that make up the form of a poem (including diction , syntax , lineation , stanza , rhythm , and the many different types of rhyme ). It's just that there aren't any rules governing how they must be used.

Other Helpful Free Verse Resources

- The Wikipedia Page on Free Verse : An overview of free verse, including a bit more information on the history of its use.

- The Dictionary Definition of Free Verse : A simple definition of free verse.

- Collected free verse : A webpage that compiles some of the more famous examples of free verse poetry from history.

- Free Verse on Youtube : A short video that gives a basic definition of free verse and provides some examples.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1902 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,034 quotes across 1902 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Blank Verse

- Formal Verse

- Rhyme Scheme

- Point of View

- Round Character

- Deus Ex Machina

- Polysyndeton

- External Conflict

- Personification

- Onomatopoeia

- Foreshadowing

- Figure of Speech

6 Books in Verse That Will Leave You in Awe

Yashvi Peeti

Yashvi Peeti is an aspiring writer and an aspiring penguin. She has worked as an editorial intern with Penguin Random House India and HarperCollins Publishers India. She is always up for fangirling over poetry, taking a walk in a park, and painting tiny canvases. You can find her on Instagram @intangible.perception

View All posts by Yashvi Peeti

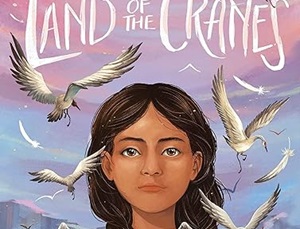

A Poet’s Glossary defines books in verse as “A novel in poetry. A hybrid form, the verse novel filters the devices of fiction through the medium of poetry.” Fiction filtered through verse are stories gifted with all the beauty and liberation provided by poetic devices. Here’s a list that holds wonderful books in verse that have moved me with their narrative, intensity and rhythm.

Other Words for Home by Jasmine Warga

This book in verse follows a young Syrian refugee as she leaves her home, father, and brother behind to live in Cincinnati with her mother and relatives. The tender and torn perspective of the middle grader captures the inner conflict of being a refugee. The verse format and hard-hitting lines call for our empathy and kindness.

“There is an Arabic proverb that says: She makes you feel like a loaf of freshly baked bread.

It is said about the nicest kindest people. The type of people who help you rise.”

For Every One by Jason Reynolds

For Every One truly is for every one. It is a letter in verse to all dreamers. Jason Reynolds acknowledges and appreciates all the colors and shades of dreams that humanity can hold within its heart. It reminds every reader of both the weight and weightlessness of every dream they hold. I highly recommend that you read this short, wonderful book in verse in one sitting.

“Though the struggle is always made to sound admirable and poetic, the thumping uncertainty is still there.”

The Black Flamingo by Dean Atta

This beautiful book follows Michael, a half Jamaican, half Greek-Cyprian boy who is trying to come to terms with his mixed-race queer identity. The novel holds important conversations about race, sexuality, homophobia, and racism. It introduces ideas such as internalized racism and homophobia which give us much-needed insights. Filled with intensity, fierceness, confusion and celebration; this verse novel is an entire journey.

“Don’t come out unless you want to. Don’t come out for anyone else’s sake. Don’t come out because you think society expects you to. Come out for yourself. Come out to yourself. Shout, sing it. Softly stutter. Correct those who say they knew before you did. That’s not how sexuality works, it’s yours to define.”

Turtle Under Ice by Juleah del Rosario

Told in dual perspectives, this verse novel captures the grief and hope of two sisters after losing their mother. Its haunting yet eloquent style makes the story hit home. The lines make you pause and ponder and feel deeper.

“But that’s not what our family is.

It’s a frayed string of lights that someone needs to fix with electrical tape.

It’s the electricity that can’t get to us because Mom’s bulb has burned out, so now the whole string is dark.

But without the lights turned on, does anyone even notice that we are broken?”

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox. By signing up you agree to our terms of use

When You Ask Me Where I’m Going by Jasmin Kaur

Wonderfully woven with poetry, illustrations, and prose, this book will leave you in awe. It tells the story of two Sikh women in a land away from home; a mother and a daughter navigating with fear, love and hope. It tackles difficult political, feminist and mental health themes with a voice that is as fierce as it is gentle.

“a woman once offered me a pencil and i thanked her profusely

another offered me life again and again and i never got around to thanking her.”

Inside Out & Back Again by Thanhhà Lai

Inside Out & Back Again was inspired by Thanhhà Lại’s own experiences. She writers in the author’s note: “At age ten, I, too, witnessed the end of the Vietnam War and fled to Alabama with my family. I, too, had a father who was missing in action. I also had to learn English and even had my arm hair pulled the first day of school. The fourth graders wanted to make sure I was real, not an image they had seen on TV.” The eloquent verse format explores the journey of a young, fierce girl navigating an unfamiliar world while craving the comfort of home.

“But last night I pouted when Mother insisted one of my brothers must rise first this morning to bless our house because only male feet can bring luck.

An old, angry knot expanded in my throat.

I decided to wake up before dawn and tap my big toe

to the tile floor first.

Not even Mother, sleeping beside me, knew. February 11 Tết”

For more recommendations, check out our list of 100 Must-Read YA Books in Verse .

You Might Also Like

A Brief History of the Novel in Verse

Poetry is constantly evolving, becoming more diverse and wide-ranging. In fact, sometimes it refuses to be contained within one genre, leading to innovative works that blur categorization and boundaries. The novel in verse, in particular, brings together both fiction and poetry, using the imagery-driven lyricism of poetry to make a narrative impact. Though this genre has roots in sprawling and ancient epic poetry, it gained traction in the 19th century. Here are some of the novel in verse’s biggest moments and most spotlighted texts.

19th century

It took the famed and prolific Lord Byron five years to compose the 16 cantos that make up Don Juan , one of the earliest examples of the novel in verse. Published in 1823, the novel satirizes topics like dating, seduction, and British aristocracy. Like many influential works, Don Juan received backlash , with critics calling it immoral and speculating that Lord Byron found inspiration from those in his own life. Nevertheless, the text continues to be studied today, with many noting its surprising twists and unabashed playfulness.

Another early novel in verse comes from acclaimed classic writer Elizabeth Barrett Browning , who published Aurora Leigh in 1856. The book stretches across nine volumes, as well as spans the varied, sophisticated settings of Florence, London, and Paris. Told in a diary-like style with a strong, first-person voice, Aurora Leigh chronicles its titular character’s childhood, her pursuit of an education, and her accomplishments as a writer.

20th century

The 20th century introduced the novel in verse to an expanded audience, with major publishers taking on these titles, which went on to win notable awards. Alan Wearne ’s The Nightmarkets— a searing yet funny book that criticizes bureaucracy and money in politics—came out in 1986. With this release, Wearne achieved honors like winning the Grace Levin Prize and Colin Roderick Award. Wearne also showcased the international appeal of the novel in verse, as well as the genre’s ability to reflect a sense of place, culture, and history, through his depiction of Melbourne suburbs throughout The Nightmarkets.

The 20th century also cemented the novel in verse as a genre that connects with children and YA audiences , a trend that continues today. Newberry Medal winner Sharon Creech became a fixture in school libraries with Love That Dog and Heartbeats , two novels that featured storylines about young teenagers exploring creative self-expression and coming of age. While these novels in verse spoke from a modern perspective, Karen Hesse ’s Out of the Dust— another iconic YA title in the genre—transported readers to the Oklahoman Dust Bowl, using the novel in verse as a compelling, more person-centered way to introduce historical lessons and perspectives.

Recently, the novel in verse has propelled itself toward more recognition and popularity. In 2018, The Long Take by Robin Robertson won the Walter Scott Prize and was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Told from the perspective of a veteran who served in Normandy, the book discusses trauma, homelessness, and gentrification, as readers follow the main character through New York City, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.

Novels in verse often blend not only fiction and poetry, but multiple cultures or multiple languages. Leticia Sala ’s In Real Life , published in 2020, is a Spanish and English novel that speaks to the common experience of finding love online through a distinctly uncommon lens: This love takes the protagonist from Barcelona to New York City.

This is part of Read Poetry’s National Poetry Month series. For more on the history of poetry, check out our introductions to free verse , lyric poetry , and spoken word .

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Incorporating Sound Into Modern Poetry

5 Fiery Writing Prompts for Aries Season

4 Poetry Collections to Read After You Listen to Kacey Musgraves’ Deeper Well

- Our Mission

Verse Novels Are Everywhere—Here’s How to Teach Them

The distinct and evolving genre merges devices of fiction and poetry with a clear narrative arc—and it’s uniquely compelling to middle and high school readers.

Last spring, the English supervisor in my district sent an unexpected gift to teachers: a list of several dozen books from which we could each order six for our classrooms on the district’s dime. Many titles were familiar classics such as Poe short stories and Twain novels. But a portion of the books were in a format I’d not yet incorporated in my teaching: novels in verse, also called verse novels. Among the selections for eighth grade were bestsellers like Jason Reynolds’s Long Way Down , Elizabeth Acevedo’s The Poet X , and Thanhha Lai’s Inside Out and Back Again .

Verse novels are having a moment—in the publishing world and in classrooms across America. Often using free verse, creative punctuation, and in some cases blank space to tell stories with characters and narrative arcs, they recall ancient epic poetry but are recast in today’s vernacular, multimedia fluency, and cultural diversity. “Over the last few years, we’ve seen such an amazing boom” in verse novels, says Philadelphia-based literary agent Eric Smith, “particularly from marginalized writers.” The Song of Us , published this year and written by Smith’s client Kate Fussner, for instance, retells the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice in verse as a queer love story. Reynolds, who is the Library of Congress’s 2020 national ambassador for young people’s literature, blurbed the book as “a gorgeous tale” that “feels like a song.”

To find out more about how middle and high school teachers are incorporating this exciting literary form into lessons, I checked in with educators from Texas to Shanghai and came away inspired to use verse novels with my students this year.

A Powerful Engagement Hook

The immediacy, expansiveness, and playfulness of verse novels draw in students who otherwise may find poetry opaque or flowery, and prose novels intimidatingly dense. They also tend to let students begin to see a place for themselves as writers. “They start realizing that writing doesn’t have to be a specific thing,” says Schuyler Hunt, a ninth-grade teacher in Washington, D.C. “Writing doesn’t have to fit in a narrow box; it can be expansive, it can be playful, it can be outside of a formal register and still have tremendous power.”

Teachers who’ve taught verse novels for years told me about their immediacy. Written with YA readers in mind, they’re often focused on contemporary concerns, engaging kids quickly, compared with, for example, classic long-form poems like The Odyssey —which may take longer for kids to connect with but should continue to be an important part of the reading mix. Students find a verse novel like Inside Out and Back Again “easy to read and understand because each of the poems are set up like snapshots of a moment in time,” says Lisa Bello, a middle school teacher in Jersey City, New Jersey. Because they use blank space and creative lineation, verse novels can provide a transition from illustrated books to all-text novels. Yet teachers emphasize that they are not simply a step on the way to “real novels” but a valuable and essential form that engages students and leans on oral traditions, broadening the middle and high school canons.

The engagement piece is critical, of course, as the research continues to track how reading for pleasure, now at its lowest level in decades, drops precipitously by middle school, according to the Pew Research Center . Around third grade, 42 percent of kids say they read for fun almost every day, but by age 13, that number drops to 17 percent. Experts such as the psychologist Jean Twenge attribute this decline to the distractions of social media and smartphones , but others fault school accountability measures , which haven’t led to significant gains in reading or engagement , especially as testing mandates squeeze out classroom activities known to reinforce lifelong reading habits, such as independent reading time and access to different genres and formats.

With verse novels, the appearance of brevity “never fails to hook my reluctant readers,” says Rebecca Decker, who teaches English at Brick Township High School in New Jersey. Her observation is echoed by many teachers I spoke with. “The amount of blank space on the pages is initially very attractive,” says high school teacher Hunt. “Blank space defines what is actually on the page. It’s a great exercise in inferential reading.”

While the clever, sparse writing style and format may appeal to new or lapsed readers, teachers say it allows for a similar level of layered analytical interpretation as they’d use in a poetry unit. The verse novel “allows teachers the flexibility of having deeper discussion, and it empowers kids because they can finish a book,” says Bloomington, Illinois, high school teacher Brandon Thornton. “I felt more empowered to teach figurative language in context—to have a text in front of me to say when [Reynolds] says your tail is showing, he’s not talking about a dog tail.”

Like Someone Talking In Your Ear

While verse novels may feel like a new and exciting type of reading when students first encounter them, teachers point out that the form has a long history, going back to epic poetry and oral storytelling. Verse novels, says Rebecca Decker, “are updated forms of writing we have had for centuries. But therein lies the key—they’re updates . Our students are worlds apart from The Odyssey , and while it’s important to show them where writing has come from, I believe as an educator it is even more important to show them how writing has evolved.”

Verse novels tend to be first person and personal, making them uniquely accessible to younger readers. They are often “very direct, almost like someone is talking in your ear, someone is pouring their heart out to you, and kids relate to that,” says author Betty Culley, whose book The Name She Gave Me follows an adoptee finding her birth mother.

They are also expansive in whose voices and lives are featured in a story. “With students who are first generation or immigrants themselves, sometimes it makes them feel less alone because they can identify with some of the experiences of the characters,” says Bello, the middle school teacher. Many cultures had long literary traditions before the popularization of the prose novel in 19th-century Europe. While the first identified novel, or fictional work in prose, is an 11th-century Japanese work , The Tale of Genji, most global cultures historically focused on poetry and drama.

The connection to spoken word and oral storytelling resonated with the Latinae and Black San Diego high school students in the classroom of Andreana McCall, now an English professor at Mount San Antonio College. “Students from historically marginalized communities—Black, brown, Asian—have oral traditions. They are familiar with tia s and tio s telling stories at community and familial events. When they are exposed to a writing form that mimics that, then they are at home.” McCall would preface reading of The Poet X , about a high school student who finds a home in the school’s slam poetry club, with videos of the author sharing spoken-word poems, which grabbed her students’ interest immediately.

Verse Novels in the Classroom

As I spoke with teachers about the verse novel format and its impact on middle and high school readers, they shared many creative strategies for teaching these books in class. Here are four standout approaches.

Create book clubs: Students can pick from a selection of verse novels to form book clubs and then discuss and analyze literary elements in whole-class lessons. Schuyler Hunt’s ninth graders choose from Long Way Down , The Poet X , and Dean Atta’s The Black Flamingo for an end-of-year unit where they examine the author’s use of language (and their own language growth) through a full-class Socratic seminar and a portfolio. In Matthew Kloosterman’s middle-school classroom in Shenzhen, China, students form book clubs that support a shared theme. “Students can take a stance as a book club on whether their verse novel connects or does not to the theme, with justification provided,” he says.

Dive into literary analysis: Verse novels can be accessible as whole-class reads, focusing on analysis of poetic and narrative elements, from metaphor and simile to characterization and conflict. Students can analyze a poem or page during one class. Bloomington’s Thornton adjusts his figurative language lessons to incorporate examples from Long Way Down , and students write their own couplets in response, highlighting a literary element.

Explore themes and background knowledge: Most verse novels make a point to engage with larger social issues. While reading Reynolds’s Long Way Down, Thornton’s 11th graders in Indiana focus on the idea of rules and which ones are productive, culminating in an impassioned debate about the book’s open-ended conclusion. Rebecca Decker’s students read the same book for a unit on juvenile justice. Kloosterman’s middle-grade students in China compare themes of truth, history, and individual freedom in Long Way Down and The Outsiders . Independent reading and multimedia responses: Students can pick a verse novel from a classroom library or from a curated selection of verse novels for independent reading, and then highlight favorite quotes on a classroom quote wall or via multimedia projects such as music videos, written poetry, or spoken-word poetry. McCall’s students’ final project, for example, was a short video montage that featured their own poem in the style of Acevedo with accompanying music and photographs.

- Equity & Inclusion

- Workshop Login

- 570-253-1192

Writing Novels in Verse: 5 Articles To Help You With Form, Structure, and Style

Sep 23, 2021 | Novels in Verse

The verse novel is an incredibly powerful art form when done well, packing a punch with judicious word choices, open spaces, vivid encapsulations of scenes and emotions, all delivered in a narrative that flows rhythmically. We’ve put together a few articles to help you explore questions to consider when writing a verse novel and to discover what makes a novel in verse successful.

Verse Novels: A String of Emotional Moments

Successful verse novelists Padma Venkatraman and Joy McCullough interview each other about why they write novels in verse and discuss some of the ways in which verse novels differ from prose novels, what some of their favorite verse novels are, and how to know when a story is well suited for the novel in verse form. Read the full article .

Auditioning Poetry Devices for Your Verse Novel’s Voice

Writing verse novels means tackling particular limitations but it also means uncovering, experimenting and a lot of play. It is an expansive form that can be liberating! One of the major liberations is all that poetry has to offer your verse novel. Opening up the poetry toolbox and finding the precise tools you need to create a dynamic voice for your narrative style is one of the most exciting aspects of writing verse novels. Read the full article .

Read a Verse Novel a Day for Poetry Month

Verse novelist Kathryn Erskine decided to read a verse novel each day of April. Her round-up of the books she read provides an introduction to some really great verse novels. Read the full article .

Imagining an Image System for Your Novel in Verse

An image system is the family of images (metaphors, similes, symbols, etc.) an author chooses to showcase in their verse novel. An image system, by use of extended metaphors, can show how characters emotionally grow and change through the course of a story. They also can work to build story tension, foreshadow events, develop secondary characters, inspire characters to action, illuminate setting and reflect a story question or theme. Image systems in verse novels can reveal character growth and central story themes and questions. Read the full article .

The Verse Novel: If I Can Do It, So Can You

Kathryn Erskine talks about how she decided that verse was the right vehicle for her novel: “Using the verse form enabled me to focus on emotions. I could use a variety of characters and viewpoints, so the reader could see and evaluate the big picture. I could string the scenes and people together with an invisible thread from one person’s consciousness to another’s, weaving the story from their different voices.” Read the full article .

Related Posts

3 Questions for Laura Shovan About Using Breaks and Blank Spaces in Your Verse Novel or Poetry

Conveying and Understanding Emotions Through Powerful Poetry: A Verse Novel Example

Podcast: Chris Baron And Rajani LaRocca

See all programs.

About Our Programs

> Working Retreats > In-Community Retreats & Programs > Online Courses > On-Demand (Self-Paced Online) > The Whole Novel Workshop > Summer Camp > Free #HFGather Webinars

More Ways to Learn & Connect

> Explore by Genre & Format > Just starting? Learn About Children's Publishing

Visit On Your Own

> Personal Retreats > Custom Retreats

What Makes Us Different

Our Faculty Share Your Story, Inspire a Child Testimonials

Need help figuring out what's right for you?

Ask an ambassador !

Find All Upcoming Retreats & Workshops

Our Mission in Action

Share Your Story, Inspire a Child Scholarships Equity & Inclusion in Kidlit Partners & Sponsors

The Highlights Foundation positively impacts children by amplifying the voices of storytellers who inform, educate, and inspire children to become their best selves. Learn more about our impact.

Get Involved

Donate Support Our Scholarship Program Sponsor a Cabin Sponsor Our Essential Conversations Support the Highlights Foundation

Need help deciding on a workshop? Ask an ambassador !

Logistics & Info

- Visiting Our Campus

- Payment Plans

- Reschedule & Refund Policies

- Gift Certificates

- Sign Up for Our Email List

- Follow Us on Social Media

- Tell Us About Your Experience

- Anti-Harassment Policy

- Community Standards

- Commitment to Equity & Inclusion

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

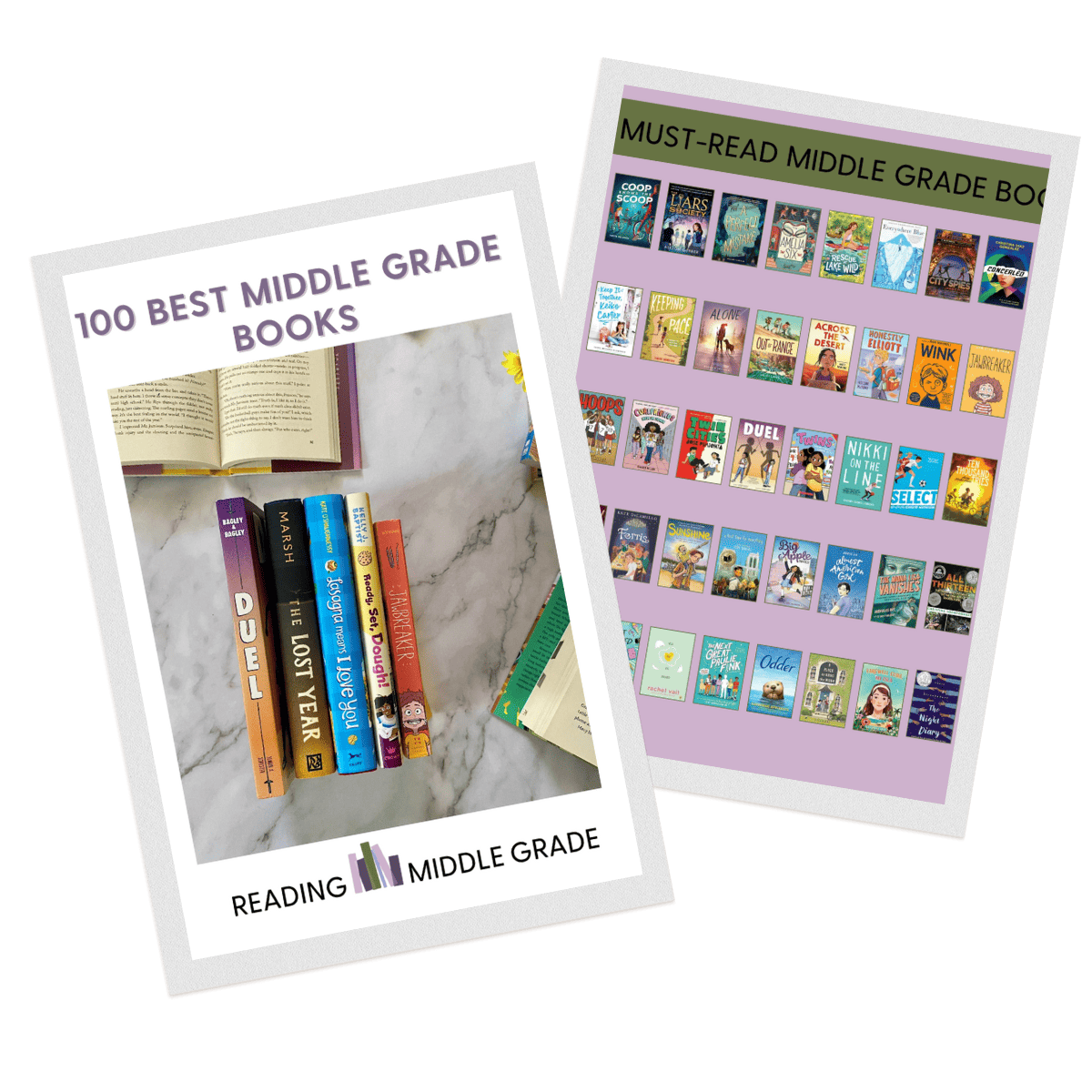

Download 100 Best Middle Grade Books. Send it!

Join our Patreon Community for EXCLUSIVE content

Reading Middle Grade

Books for Kids and Grown Ups

30 Best Middle-Grade Novels in Verse

Middle-Grade novels in verse have been around for a while. Not sure what that is? Novels in verse are novels written in stanzas, pretty much like poetry. Still, they weave in dialogue, characters, and all the elements of a novel. I’m not a massive fan of novels in verse (generally) because they tend to lack the level of detail I enjoy in novels, but there are several that I’ve read and LOVED.

Anyone can enjoy middle-grade novels in verse but I definitely think poetry lovers would gravitate more to this narrative form. They also work well for ESL students as the vocabulary tends to be simpler and more accessible. For this list, I’m sharing my FAVORITE verse novels for the middle school (and upper elementary) crowd, many of which tackle tough issues like immigration, mental health, and grief. You’ll also find an engaging mix of historical and contemporary options.

Join our Patreon community to get the printable version of this li st ! You’ll also get access to other kid lit resources and perks, like our seasonal guides and educator interviews, to inspire you.

30 Moving Middle-Grade Novels in Verse

Here are 30 best middle grade novels in verse:

This survival verse novel follows 12-year-old Maddie, who gets abandoned by some twist of fate when her entire town is mysteriously evacuated. Left alone with no human in sight, she bonds with a Rottweiler named George, who is one of many abandoned pets. Soon after, they lose power and then water, and Maddie has to fend for herself using a variety of ingenious means and the town resources at her disposal, including an empty library, grocery store, and neighbors’ homes. Kids in grades 6+ won’t be able to get enough of this verse novel with a tenacious protagonist and engaging plot.

Isabel in Bloom

After years of living in the Philippines while her mom works abroad, it’s finally time for Isabel to reunite with her mother in California. But when she arrives, there’s so much to adjust to, from snooty classmates to big malls, the absence of green space in their small apartment, and the different food. Armed with her grandfather’s advice to look for the familiar, things slowly get easier as she joins a cooking club in school and starts working on growing the school garden. I enjoyed this one and loved the underrepresented theme of an immigrant parent reuniting with a child and the insight into balikbayan boxes. It also includes a depiction of Filipino culture and musings about elderly Asian attacks as one older man in the community is attacked. Good for readers in grades 6+

Other Words for Home

Young Jude is uprooted from her life in Syria in the midst of the civil unrest. She and her mother (who is pregnant) moved temporarily to Cincinnati to live with her uncle and his family. Jude is sad to leave behind her country, best friend Fatima, father, and brother who’s involved in various protests in Syria. In America, Jude — who used to be the best English student in Syria — has to join an ESL class and deal with questions about her hijab. Still, Jude finds good things in America and learns how brave she can be. I would recommend Other Words for Home to anyone looking for stories set in Syria, fans of Hena Khan’s Amina’s Voice, and readers in search of a story with a brave female protagonist.

Louder Than Hunger

In John Schu’s debut middle-grade verse novel, he pulls back the curtain to let readers into a fictionalized depiction of his struggle with an eating disorder and life in a facility fighting against the condition. This book is truly a gut punch and flies by so quickly for such a thick novel with a tough subject matter — a testament to Schu’s great writing. Perfect for readers in grades 6+ looking for more body image books and fans of Lerner’s A Work in Progress .

Closer to Nowhere

This was my first Ellen Hopkins book, and I get the hype now. It grabbed me from page one with unmistakable character voices. Readers will follow Cal and Hannah, two cousins suddenly living under the same roof after a family tragedy. While Cal twists the truth and likes pranks, Hannah is serious and “honest as the day is long.” This is a heartwrenching and heartwarming book about family, grief, substance abuse, and empathy. Great for grades 6+ and especially grades 7 & 8.

Force of Nature

This verse novel is inspired by the life of Rachel Carson and presents a well detailed account of her childhood, passion for nature, and love for her mother. It also features art by Sophie Blackall. Although I love verse novels, I didn’t know much about Carson’s life and wasn’t as invested in this one. However, the writing is nostalgic and poetic and the illustrations complement the text nicely. Fans of Rachel Carson and poetry will love this. Grades 5+

Before the Ever After

ZJ’s dad is a popular pro American footballer. He has a awesome crew of male friends who feel like family. Life seems pretty good until his dad comes home early from a game with an awful headache. The headache is joined by disturbing symptoms like forgetfulness, aggression, spacing out, and general confusion. The book is set in 1999-2000, when there was just a growing awareness of CTE. ZJ’s mom is worried because she knows a few other football friends of his dad who have had the same symptoms. As ZJ tries to get through each day, not knowing whether it’ll be a good day for his dad or a bad one, he finds comfort in family, comfort, and community. This is a brilliant, true-to-life portrayal of a child coping with his famous father’s deterioration due to CTE. Grades 6+

Tully Birch’s mom left them weeks ago and Tully is convinced that if she does a marathon swim, something her mom was supposed to help her train for, her mom would see she is worth returning for. Her friend Arch is her only supporter, and although the swim starts out well, the weather, poor training, the weight of sad memories, and fatigue catch up with Tully just around the halfway mark. This book is gorgeously written and accessible for tween readers. I loved the shape poems, the survival edge throughout the story, and Tully and Arch’s friendship. I also enjoyed the way Sumner gradually shows readers a clearer vision of Tully’s mom besides the initial rosy depiction we see. This is a very short book that will appeal to fans of Alone and verse novel lovers in general. Grades 5+

Forget Me Not

Read this book about a girl with Tourette’s in one sitting! Calliope June’s mother moves around so often and yet always wants her to hide the fact that she has Tourette’s. Of course, hiding TS is nearly impossible because Calliope sometimes unintentionally makes noises or faces (tics). Things get interesting when she meets and likes a boy who turns out to be a popular student in her school. At first, he seems to like her, but when people at school make fun of Callie, he’s embarrassed to be seen with her. This novel in verse, is so beautifully written. I felt Calliope’s pain in every word. Such an unexpectedly moving book. Highly recommend! Grades 6+

Ultraviolet

Elio is in love for the first time, and his dreams come true when Camelia, his crush, becomes his first girlfriend. His first relationship and an association of males teach him plenty about consent, patriarchy, toxic masculinity, and respect for women. Plenty happens in this book, written in lyrical, accessible verse that feels akin to Judy Blume but for boys, as Salazar writes candidly about Elio’s morning erection, nocturnal emissions, and the way he feels down there when he’s around Camelia. Still, the text remains appropriate for tweens and young teens looking for more information than they might be getting from their parents about vital sex ed. Good for grades 7+

Starfish features Ellie, a fat girl who has been bullied for her weight since she wore a whale swimsuit and made a big splash in the pool. Even her older brother and sister make fun of her weight. Her mom controls her diet, monitoring her portions and choosing lackluster “healthy” alternatives. Ellie is feeling more disheartened because her friend Viv who is also plus-sized is moving away. Thankfully, after Viv moves, Ellie finds a friend in her new neighbor Catalina and her family. The family loves food and welcome Ellie with open arms, never judging her for her weight. This is a powerful, fat-positive middle grade verse novel about a girl who is learning that she deserves to take up space. Grades 5+

Iveliz Explains It All

In this Newbery Honor book, we meet Iveliz, a new 7th grader who’s recovering from a rough year and determined to bounce back. Unfortunately, more life changes, unprocessed grief, and mental health challenges threaten to keep her stuck. My heart ached for Iveliz throughout this story, and I think it will especially speak to tweens struggling with their mental health. I also loved the notebook-style font design and illustrations throughout the book. Good for grades 6+

Everywhere Blue

When Madrigal’s (Maddie) older brother, Strum, goes missing from his college campus, her musical family loses its harmony. Her French mother is distraught — broken for the first time as Maddie has never seen her. Her piano-playing father doesn’t even touch his instrument, and her fiery sister retreats into a rebellious funk, drinking and partying, even though she’s only 16. Maddie tries to keep everything together: focus on her oboe lessons and compulsive counting that calms her mind. Eventually, though, with all leads looking dead-ended, Maddie just might have what it takes to find Strum. But can she find her way to him? Everywhere Blue is a poignant, moving middle grade verse novel about family, mental health, music, and caring for the environment. Grades 6+

Malian is stuck visiting her grandparents when the COVID pandemic starts. When a stray rez dog shows up at their door, Malian is eager to welcome him in. This is a warm, gentle, and short verse novel (with very little plot) about the ways indigenous communities look out for each other (and how they did in times past). Grades 5+

The Magical Imperfect

Etan develops selective mutism after his mom has to go to a treatment facility for a mental disorder in 1980’s San Francisco. Around that time, mini-earthquakes are frequent and Etan tries to keep up his daily schedule, which is basically school and then time with his grandfather. Sometimes, he helps an older shopkeeper in the neighborhood walk her dog and run errands. It is while he is on one of those errands that he meets Malia, a Filipina-American girl with severe eczema. Etan and Malia become fast friends and he gets a closer look at how debilitating her eczema is. He wants to take Malia’s suffering away, and he thinks his grandfather’s Dead Sea clay can make a difference — perhaps even heal Malia’s eczema. But will the clay work? This is an incredibly moving verse novel about friendship, family, body image, and community. Grades 6+

Thirteen-year-old Ava lives in 80s California and loves to catch a wave with her best friend, Phoenix, a cancer survivor, whom she’s beginning to crush on. Her mom is a single mother and her dad lives in Iran with his new family and rarely contacts them. Ava likes to write poetry and sing (she’s getting to sing in the school choir soon) but her mom who’s a doctor wants Ava to consider that career path. Amidst all the drama, Phoenix’s lymphoma returns aggressively and he doesn’t want to pursue treatment anymore. Can Ava convince him to keep trying? This is a lyrical, captivating, and heartwrenching middle grade verse novel about first crushes, surfing, and grief. Grades 7+

Red, White, and Whole

The year is 1983, and 13-year-old Reha is caught between two cultures: her Indian family and community at home and the all-American experience at school and with her white “school best friend.” But it’s not all rosy. Her mother doesn’t approve of Reha acting more American than Indian. Then her mom is diagnosed with leukemia, and Reha’s life is turned upside down. Between school, family issues, and navigating her affection for a boy in her neighborhood, Reha has her plate full. Red, White, and Whole is a heartwarming and heartbreaking verse novel about mothers and daughters, the eighties, and straddling two cultures. Grades 6+

The Lost Language

The Lost Language centers around 6th grade Betsy and her best friend, Lizard (both girls are actually named Elizabeth!) who decide to save a disappearing language Guernsiais (spoken on the small Isle of Guernsey, off the coast of France). Betsy’s mom is a passionate linguist who — unbeknownst to Betsy — is also dealing with depression and anxiety. Lizard has always been a bit of a bossy, possessive friend, thanks to her assertive character. As the two girls work on the project together, cracks in their friendship begin to show and a near-tragedy in Betsy’s family threatens to tear them apart. This is a thoughtful, engaging look into a changing friendship as one friend grows into herself. Grades 5+

The Crossover

Thanks to their dad, Josh and his twin brother, Jordan, are kings on the court. But Josh has more than basketball in his blood—he’s got mad beats, too, which help him find his rhythm when it’s all on the line. As their winning season unfolds, things begin to change. When Jordan meets a girl, the twins’ bond unravels. This is an utterly moving novel in verse. Grades 6+

Golden Girl

Afiyah has a problem with stealing things even when she tries really hard not to. Fortunately, she’s often remorseful and returns the stolen items. She’s shaken when her father is wrongfully arrested for embezzlement at the airport during a family trip. The situation puts a strain on her family and moves Afiyah to strongly examine her tendency to steal — especially after she gets caught in the act. This is a touching, realistic coming-of-age story about trying to break bad habits and dealing with a family crisis. Grades 6+

The One and Only Ivan

Having spent 27 years behind the glass walls of his enclosure in a shopping mall, Ivan has grown accustomed to humans watching him. He hardly ever thinks about his life in the jungle. Instead, Ivan occupies himself with television, his friends Stella and Bob, and painting. But when he meets Ruby, a baby elephant taken from the wild, he is forced to see their home, and his art, through new eyes. Grades 3+

The Night Diary

This is a heartbreaking middle grade book about a girl’s experience during the partition of India. Nisha is caught between her Hindu-Indian and Muslim-Indian sides. She’s also dealing with the loss of her mother. So when her country starts to split in two, her search for identity becomes even more meaningful. There’s a reason why this one is a Newbery Honor book. If your kids loved this book, here’s a list of more books like The Night Diary . Grades 6+

When Reena, her little brother, Luke, and their parents first move to Maine, Reena doesn’t know what to expect. She’s ready for beaches, blueberries, and all the lobster she can eat. Instead, her parents “volunteer” Reena and Luke to work for an eccentric neighbor named Mrs. Falala, who has a pig named Paulie, a cat named China, a snake named Edna—and that stubborn cow, Zora. This heartwarming story, told in a blend of poetry and prose, reveals the bonds that emerge when we let others into our lives. Grades 5+

Garvey’s Choice

This verse novel follows the evolution of a boy named Garvey, who loves astronomy, music, and books — everything but the sports that his dad would prefer he enjoys. Despite all the bullying he faces, once he joins the school chorus, he starts to grow past his father’s expectations, finding a way to connect with his father on his terms. Grades 5+

Reckless Glorious Girl

Beatrice lives with her Mawmaw (her grandmother) and her mom in Bardstown, Kentucky. Her father died in an accident months before she was born. The book is set the summer before seventh grade and Beatrice is trying to figure out who she wants to be. Although she has two great girlfriends, she’s curious about what life would be like with the popular girls. Reckless, Glorious, Girl is a quintessential coming-of-age story about a girl whose community of women helps her find herself.

The One Thing You’d Save

Linda Sue Park’s The One Thing You’d Save is a unique hybrid of sorts. It’s geared toward middle schoolers, but has lovely black and white illustrations on nearly every page. It is also less than 80 pages long, with sparse text in the Korean sijo poetry style. By the end of the class, even the teacher rethinks her choices, just as every reader will. This book might not satisfy you, if like me you enjoy plot, but it will make you think about the one thing, or things that matter most to you. Teachers and middle schoolers alike will find this book to be an excellent conversation starter, and the illustrations will entice reluctant and younger readers.

Emmy in the Key of Code

In a new city, at a new school, twelve-year-old Emmy has never felt more out of tune. Things start to look up when she takes her first coding class, unexpectedly connecting with the material—and Abigail, a new friend—through a shared language: music. But when Emmy gets bad news about their computer teacher, and finds out Abigail isn’t being entirely honest about their friendship, she feels like her new life is screeching to a halt. Despite these obstacles, Emmy is determined to prove one thing: that, for the first time ever, she isn’t a wrong note, but a musician in the world’s most beautiful symphony. Grades 6+

In the Beautiful Country

Living in 80s Taiwan with her mother, Ai Shi (Anna) eagerly anticipates living in the beautiful country (the US) where their father moved a few months ago. As she gives away her favorite clothes and toys to cousins in preparation for the move, she can’t help but brag about the new life awaiting them. But she’s in for a shock when they arrive at their cramped apartment. Her father was conned into buying a failing fast-food restaurant, and Anna’s parents struggle to make ends meet. At school, she feels like an outsider since she can barely speak English. On top of that, her parents are dealing with some unkind customers who mistreat them because they’re Asians.This is a moving, poignant, and lyrical verse novel about immigration, identity, food and family. Grades 6+

Rain Rising

13-year-old Rain is dealing with several issues. First, her best friend has been acting like a frenemy lately. Then, she’s just so sad all the time and can’t stop feeling negative about her body — thinking she’s ugly and too big. Her single source of solace is her family. When the thoughts become too tough to handle, her mother and brother Xander, especially, bring light to her day, even without knowing her challenges. But when Xander gets beaten up in a racially motivated attack during a potential college visit, Rain feels the walls closing in on her. Can she and her family find their way back to normalcy? Rain Rising is a powerful debut middle grade verse novel about mental health, body image, family, and healing. Grades 6+

When Winter Robeson Came