The New Yorker & Me

Introduction.

What is The New Yorker ? I know it’s a great magazine and that it’s a tremendous source of pleasure in my life. But what exactly is it? This blog’s premise is that The New Yorker is a work of art, as worthy of comment and analysis as, say, Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” Each week I review one or more aspects of the magazine’s latest issue. I suppose it’s possible to describe and analyze an entire issue, but I prefer to keep my reviews brief, and so I usually focus on just one or two pieces, to explore in each the signature style of its author. A piece by Nick Paumgarten is not like a piece by Jill Lepore, and neither is like a piece by Ian Frazier. One could not mistake Collins for Seabrook, or Bilger for Goldfield, or Kolbert for Mogelson. Each has found a style, and it is that style that I respond to as I read, and want to understand and describe.

Saturday, November 9, 2019

- Patricia Lockwood on John Updike

2 comments:

Nice summary. Can only imagine how Lockwood would treat Amis. I'd want to look, but would do so thru my fingers.

I could never read Updike nor Amis, except for his essays. I wouldn't hide behind my fingers. Lockwood is a tefreshing, somtimes shocking addition to the literary scene, definitely a blood transfusion to the brain or a tazer to the senses. She makes me laugh out loud, rare when you are 81.

- 3 for the River (5)

- 3 for the Road (13)

- 3 for the Sea (13)

- 3 More for the Road (13)

- 5 McPhee Canoe Trips (2)

- 5001 Nights at the Movies (8)

- 9/11 Memorial (1)

- A. D. Nuttall (1)

- A. J. Liebling (11)

- A. O. Scott (2)

- A. S. Byatt (1)

- Aaron Diehl (2)

- Abdellatif Kechiche (1)

- Acts of Seeing (14)

- Ad Reinhardt (1)

- Ada Limón (2)

- Adam Begley (3)

- Adam Foulds (1)

- Adam Gopnik (43)

- Adam Iscoe (6)

- Adam Kirsch (6)

- Adam Phillips (1)

- Adam Shatz (2)

- Adam Shoalts (1)

- Adam Zagajewski (3)

- Agnes Martin (1)

- Agnès Varda (2)

- Ahmed Rashid (1)

- AJ Frackattack (1)

- Al Franken (1)

- Al Hirschfeld (1)

- Alan Arkin (1)

- Alan Broadbent (2)

- Albert Camus (1)

- Alden Nowlan (1)

- Alec Soth (1)

- Alec Wilder (2)

- Alec Wilkinson (16)

- Alejandro Chacoff (1)

- Aleksandar Hemon (6)

- Alex Abramovich (2)

- Alex Haley (1)

- Alex Katz (3)

- Alex Ross (29)

- Alexander Nemerov (4)

- Alexander Pope (1)

- Alexandra Jacob (1)

- Alexandra Schwartz (16)

- Alfonso Cuarón (1)

- Alfred Hitchcock (1)

- Alfredo Cáliz (1)

- Alice Driver (1)

- Alice Gregory (1)

- Alice McDermott (1)

- Alice Munro (4)

- Alice Zoo (1)

- Allen Ginsberg (1)

- Amanda Petrusich (1)

- Amedeo Modigliani (1)

- Amelia Lester (15)

- Amia Srinivasan (1)

- Amy Goldwasser (2)

- Amy Lombard (2)

- Amy Sillman (1)

- Ana Juan (1)

- Anagh Banerjee (1)

- André Aciman (1)

- André Carrilho (3)

- Andre D. Wagner (2)

- André Malraux (2)

- Andrea K. Scott (31)

- Andrea Thompson (2)

- Andrea Ventura (7)

- Andrew Dominik (1)

- Andrew Marantz (3)

- Andrew O'Hagan (8)

- Andrew Wyeth (3)

- Andy Friedman (2)

- Andy Warhol (4)

- Ange Mlinko (1)

- Angelica Garnett (2)

- Angie Wang (2)

- Anita Desai (1)

- Anka Muhlstein (1)

- Ann Beattie (1)

- Ann Patchett (4)

- Anna Russell (7)

- Anne Boyer (7)

- Anne Carson (1)

- Anne Golaz (1)

- Annette Marnat (1)

- Annie Proulx (4)

- Anthony Bailey (19)

- Anthony Bourdain (2)

- Anthony Gottlieb (1)

- Anthony Lane (77)

- Anton Chekhov (2)

- Antony Huchette (1)

- Anuj Shrestha (1)

- April Bernard (1)

- April Bloomfield (1)

- Ariel Levy (3)

- Arlene Croce (5)

- Arthur Krystal (2)

- Arthur Lubow (3)

- Arthur Miller (1)

- Arthur Penn (1)

- Artur Domoslawski (1)

- Asif Kapadia (1)

- At the Archive (3)

- Atul Gawande (1)

- Aude Van Ryn (1)

- August Kleinzahler (1)

- August Sander (1)

- B. F. Skinner (1)

- B. J. Leggett (2)

- Bar Tab (1)

- Barack Obama (4)

- Barry Blitt (1)

- Barry Levinson (1)

- Barry Lopez (2)

- Basharat Peer (1)

- Becca Rothfeld (1)

- Becka Viau (1)

- Becky Cooper (14)

- Ben Affleck (1)

- Ben Greenman (1)

- Ben Lerner (5)

- Ben Maddow (2)

- Ben McGrath (20)

- Ben Ratliff (1)

- Ben Taub (10)

- Bendik Kaltenborn (13)

- Benjamin Anastas (1)

- Benjamin Hedin (1)

- Benjamin Labatut (1)

- Benjamin Lowy (6)

- Benjamin Moser (1)

- Benjamin Shapiro (1)

- Benjamin Taylor (1)

- Benoit Pilon (1)

- Berenice Abbott (1)

- Bernard Berenson (1)

- Bernard Madoff (1)

- Bernd and Hilda Becher (1)

- Berton Roueché (3)

- Best of 2010 (1)

- Best of 2011 (1)

- Best of 2012 (1)

- Best of 2013 (1)

- Best of 2014 (1)

- Best of 2020 (1)

- Best of 2021 (8)

- Best of 2022 (9)

- Best of the Decade (14)

- Betsy Morais (1)

- Betty Woodman (1)

- Bettye LaVette (3)

- Bianca Bagnarelli (1)

- Bill Barich (1)

- Bill Bragg (2)

- Bill Brandt (1)

- Bill Buford (9)

- Bill Charlap (5)

- Bill Knott (1)

- Billy Strayhorn (1)

- Bjorn Lie (1)

- Blake Bailey (1)

- Blexbolex (1)

- Bob Dylan (2)

- Bob Staake (1)

- Bonnie and Clyde (3)

- Bonnie Costello (3)

- Bookforum (17)

- Boyhood (1)

- Bożena Shallcross (1)

- Brad Leithauser (1)

- Brad Mehldau (1)

- Brassai (1)

- Brenda Shaughnessy (1)

- Brenda Wineapple (1)

- Brian De Palma (1)

- Brian Dillon (2)

- Brian Emfinger (1)

- Brian Kellow (3)

- Brian Seibert (2)

- Briana Younger (2)

- Brice Marden (1)

- Bruce Diones (3)

- Bruce McCall (1)

- Bruno Bettelheim (1)

- Bruno Martino (1)

- Burkhard Bilger (34)

- Byron Eggenschwiler (1)

- C. D. B. Bryan (1)

- C. K. Williams (1)

- Cait Oppermann (2)

- Calvin Tomkins (11)

- Calvin Trillin (12)

- Camille Pissarro (2)

- Carl Rotella (2)

- Carnovsky (1)

- Carol Sloane (1)

- Caroline Tompkins (2)

- Carolyn Drake (5)

- Carolyn Kormann (7)

- Carter Burwell (1)

- Casey N. Cep (1)

- Caspar David Friedrich (3)

- CBC Radio (1)

- Cecil Beaton (1)

- Cécile McLorin Salvant (4)

- Cecilia Carstedt (1)

- Chandler Burr (1)

- Chang Park (1)

- Chang-Rae Lee (3)

- Charis Wilson (1)

- Charles Finch (2)

- Charles McGrath (6)

- Charles Reich (1)

- Charles Simic (6)

- Charles Wright (2)

- Charlie Engman (1)

- Charlotte Mendelson (4)

- Charlotte Shane (1)

- Chimes at Midnight (1)

- Chinua Achebe (1)

- Chris Gash (2)

- Chris Wiley (6)

- Christa Wolf (1)

- Christaan Felber (4)

- Christian Lorentzen (1)

- Christian Wiman (1)

- Christina Gransow (1)

- Christine Smallwood (3)

- Christoph Mueller (1)

- Christoph Niemann (1)

- Christopher Benfey (2)

- Christopher Carroll (1)

- Christopher Hitchens (1)

- Christopher Payne (1)

- Christopher Ricks (3)

- Claes Oldenburg (1)

- Claudia Roth Pierpont (8)

- Clive James (10)

- Clyfford Still (1)

- Colin Burrow (1)

- Colin Stokes (12)

- Colin Thubron (1)

- Collier Schorr (1)

- Colm Tóibín (5)

- Colson Whitehead (1)

- Connie Walker (1)

- Conor Langton (4)

- Cormac McCarthy (9)

- Cory Arcangel (1)

- Craig Seligman (5)

- Crazy Horse (1)

- Cristiana Couceiro (2)

- Curran Hatleberg (2)

- Curtis Sittenfeld (6)

- Cynthia Ozick (1)

- Cynthia Zarin (2)

- Czeslaw Milosz (2)

- D. H. Lawrence (2)

- D. J. Enright (1)

- D. T. Max (6)

- Dadu Shin (1)

- Dahlia Lithwick (2)

- Dale Carpenter (2)

- Damien Hirst (1)

- Dan Chiasson (58)

- Dan Greene (1)

- Dan Kois (1)

- Dan Piepenbring (2)

- Dan Winters (4)

- Dana Goodyear (32)

- Dana Schutz (1)

- Dana Stevens (2)

- Daniel Berehulak (1)

- Daniel Halpern (1)

- Daniel Krall (2)

- Daniel Mendelsohn (5)

- Daniel Salmieri (1)

- Daniel Shea (2)

- Daniel Soar (1)

- Daniel Soloman (1)

- Danielle Allen (3)

- Daniyal Mueenuddin (1)

- Danyoung Kim (1)

- Darren Coffield (1)

- Darryl Pinckney (2)

- Dave Burrell (1)

- Dave McKenna (1)

- David Benjamin Sherry (1)

- David Black (2)

- David Cole (1)

- David Craig (1)

- David Denby (25)

- David Fincher (2)

- David Foster Wallace (1)

- David Grann (4)

- David Guttenfelder (1)

- David Hansen (1)

- David Huddle (1)

- David Hughes (1)

- David Kortava (8)

- David Levine (7)

- David Long (1)

- David Macfarlane (1)

- David Maraniss (1)

- David Means (1)

- David Orr (1)

- David Owen (14)

- David Park (1)

- David Peters Corbett (2)

- David Remnick (20)

- David Runciman (1)

- David S. Allee (2)

- David Salle (3)

- David Shields (3)

- David St. John (2)

- David Szalay (1)

- David Tarbet (1)

- David Wagoner (2)

- David Williams (2)

- David Wright Faladé (1)

- Davide Luciano (1)

- Davide Monteleone (4)

- Deana Lawson (2)

- Deanna Dikeman (3)

- Deborah Treisman (2)

- Debra Nystrom (1)

- Delphine Lebourgeois (1)

- Demetrios Psillos (1)

- Denis de Rougemont (2)

- Denis Johnson (1)

- Dexter Filkins (12)

- Diana Krall (1)

- Diane Arbus (4)

- Dick Conant (1)

- Dina Litovsky (9)

- Dinaw Mengestu (1)

- Dolly Faibyshev (5)

- Dominic Nahr (1)

- Don Friedman (1)

- Donald Barthelme (1)

- Donald Hall (1)

- Donald Trump (1)

- Dora Zhang (5)

- Doreen St. Félix (5)

- Dorothea Lange (2)

- Douglas Preston (2)

- Draft No. 4 (8)

- Duke Ellington (5)

- Dwight Garner (11)

- Dylan Kerr (2)

- E. B. Sledge (1)

- E. B. White (5)

- E. J. Bellocq (1)

- Eamon Grennan (1)

- Ed Caesar (8)

- Edgar Allan Poe (1)

- Edmund Wilson (1)

- Édouard Manet (2)

- Edward Burtynsky (1)

- Edward Hoagland (23)

- Edward Hopper (10)

- Edward Mendelson (4)

- Edward Sorel (4)

- Edward Weston (3)

- Edwin Fotheringham (1)

- Elaine Blair (1)

- Eleanor Birne (1)

- Eleanor Cook (2)

- Eleanor Davis (2)

- Eli Weinberg (3)

- Elie Nadelman (1)

- Elif Batuman (17)

- Elizabeth Barber (4)

- Elizabeth Bishop (18)

- Elizabeth Hardwick (3)

- Elizabeth Kolbert (25)

- Elizabeth Tallent (1)

- Ellie Wyeth Fox (1)

- Ellis Larkins (1)

- Ellsworth Kelly (1)

- Elsa Schiaparelli (1)

- Elvin Jones (2)

- Emanuele Satolli (1)

- Emily Dickinson (1)

- Emily Eakin (3)

- Emily Jo Gibbs (1)

- Emily Mason (1)

- Emily Nussbaum (3)

- Emily Witt (1)

- Emma Allen (13)

- Emma Cline (2)

- Enrique Vila-Matas (1)

- Eren Orbey (5)

- Eric Helgas (1)

- Eric Hobsbawm (1)

- Eric Klinenberg (1)

- Eric Lach (2)

- Eric Nyquist (1)

- Eric Ogden (3)

- Eric Rohmer (1)

- Erich von Stroheim (1)

- Erin Overbey (6)

- Ernest Hemingway (4)

- Ernest Jünger (1)

- Esquire (1)

- Ethan Iverson (2)

- Ethan Levitas (1)

- Eudora Welty (2)

- Eugène Atget (2)

- Eugène Delacroix (1)

- Eva Hoffman (1)

- Evan Osnos (9)

- Evelyn Waugh (1)

- F. Hopkinson-Smith (1)

- F. Scott Fitzgerald (3)

- Faith Ringgold (1)

- Favorite Photo Reviews (10)

- Fido Nesti (2)

- Forty-one False Starts (5)

- Frances Hwang (1)

- Francis Bacon (1)

- Francis Ford Coppola (2)

- Francis Luta (1)

- Francisco de Zurbarán (2)

- Francisco Goldman (2)

- François Lagarde (1)

- Frank Auerbach (2)

- Frank Kimbrough (2)

- Frank O'Hara (1)

- Frank Sinatra (1)

- Frank Stella (1)

- Frank Viva (1)

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1)

- Frans Hals (1)

- Franz Kline (1)

- Fred Astaire (1)

- Fred Kaplan (1)

- Fred Warner (1)

- Fred Wilpon (1)

- Frédéric Bazille (1)

- G. B. Edwards (1)

- Gabriele Stabile (1)

- Gabrielle Hamilton (4)

- Gaby Wood (1)

- Galen Strawson (3)

- Garry Wills (1)

- Garry Winogrand (5)

- Gary Bostwick (1)

- Gary Giddins (2)

- Gary Saul Morson (1)

- Gary Shteyngart (12)

- Gay Talese (2)

- Gazelle Mba (1)

- Geoff Dyer (30)

- Geoffrey O'Brien (2)

- George Ault (2)

- George Bellows (2)

- George Black (1)

- George Cables (2)

- George D. Painter (3)

- George Gershwin (1)

- George Kennan (1)

- George Orwell (3)

- George Packer (6)

- George Qulaut (1)

- George Saunders (1)

- George Segal (2)

- George Steiner (5)

- George Steinmetz (4)

- George V. Higgins (3)

- Georgia O'Keeffe (3)

- Gerald Scarfe (1)

- Gerald Stern (4)

- Gerard ter Borch (1)

- Gideon Lewis-Krauss (4)

- Gideon Mendel (1)

- Gigi Gryce (1)

- Gilbert Rogin (1)

- Giles Harvey (2)

- Gillian Laub (2)

- Ginger Rogers (1)

- Gini Alhadeff (2)

- Gizem Vural (1)

- Glenn Gould (1)

- GOAT Collage #1 (1)

- Goings On About Town (12)

- Golden Cosmos (1)

- Gordon Parks (1)

- Grant Cornett (4)

- Great Plains (3)

- Greg Bellow (1)

- Gregg Toland (1)

- Gretel Ehrlich (1)

- Guardian (1)

- Gus Powell (2)

- Gustav Klimt (1)

- Gustave Flaubert (1)

- H. C. Wilentz (1)

- Hal Foster (1)

- Han Ong (2)

- Hank Jones (1)

- Hannah Aizenman (2)

- Hannah Black (1)

- Hannah Goldfield (51)

- Hans Gissinger (2)

- Harold Ross (1)

- Harper's Magazine (2)

- Harry Levin (2)

- Harry Mulisch (1)

- Harry Warren (1)

- Heami Lee (2)

- Héctor Tobar (2)

- Heidi Julavits (3)

- Helen Frankenthaler (5)

- Helen Garner (1)

- Helen Rosner (13)

- Helen Shaw (2)

- Helen Vendler (34)

- Henri Matisse (3)

- Henrik Kubel (2)

- Henry Alford (1)

- Henry David Thoreau (4)

- Henry James (2)

- Henry Marsh (1)

- Henry Miller (2)

- Henry Worsley (1)

- Herbert Mabuza (1)

- Herman J. Mankiewicz (3)

- Herta Hilscher-Wittgenstein (2)

- Hervé Guibert (1)

- High Arctic Haulers (1)

- Hilaire Belloc (1)

- Hilary Mantel (1)

- Hilton Als (10)

- Hisham Matar (2)

- Hogs Wild (8)

- Howard Gardner (1)

- Howard Hawks (4)

- Howard Moss (5)

- Hua Hsu (4)

- Hubert van Eyck (1)

- Iain Sinclair (2)

- Ian Allen (3)

- Ian Buruma (1)

- Ian Crouch (1)

- Ian Frazier (158)

- Ian Parker (8)

- Icinori (1)

- Igor Levit (1)

- Igshaan Adams (1)

- Ilona Szwarc (1)

- Immo Klink (2)

- Ingrid Sischy (1)

- Interesting Emendations (38)

- Iphigenia In Forest Hills (4)

- Iqaluit (1)

- Ira Sachs (1)

- Irina Rozovsky (1)

- Iris Murdoch (1)

- Irving Penn (3)

- Isabel Magowan (1)

- Ismail Kadare (1)

- Istvan Banyai (2)

- Italo Calvino (1)

- Ivan Brunetti (1)

- Ivan Forde (1)

- J. B. Jackson (2)

- J. D. Salinger (1)

- J. M. Coetzee (1)

- Jackson Arn (9)

- Jackson Lears (1)

- Jacqueline Rose (2)

- Jacques de Loustal (3)

- Jake Halpern (3)

- James Agee (6)

- James Fenton (2)

- James Graves (1)

- James Joyce (5)

- James Lasdun (3)

- James Ley (1)

- James Marcus (3)

- James Merrill (4)

- James Nachtwey (2)

- James Schuyler (1)

- James Somers (2)

- James Thurber (2)

- James Wolcott (6)

- James Wood (141)

- Jamie Campbell (1)

- Jamie Hawkesworth (1)

- Jan van Eyck (1)

- Jane Freilicher (5)

- Jane Kramer (8)

- Jane Mayer (2)

- Janet Malcolm (75)

- Janicza Bravo (1)

- Janne Iivonen (1)

- Jason Farago (1)

- Jason Moran (1)

- Javi Aznarez (1)

- Javier Jaén (1)

- Jay Ruttenberg (3)

- Jean Renoir (1)

- Jean Rhys (1)

- Jeannie Suk Gersen (1)

- Jed Perl (3)

- Jeet Heer (1)

- Jeff Connaughton (1)

- Jeff Koons (1)

- Jeff Östberg (1)

- jefferson Hunter (1)

- Jeffrey Frank (1)

- Jeffrey Toobin (5)

- Jennifer B. McDonald (3)

- Jennifer Bartlett (1)

- Jennifer Egan (1)

- Jennifer Gonnerman (1)

- Jennifer Szalai (2)

- Jeremy Denk (2)

- Jeremy Liebman (2)

- Jerome Groopman (5)

- Jerome Kagan (1)

- Jerome Kern (2)

- Jérôme Sessini (2)

- Jerome Strauss (2)

- Jessamyn Hatcher (1)

- Jessica Pettway (1)

- Jessie Wender (2)

- Jiayang Fan (24)

- Jill Lepore (32)

- Jim Fingal (2)

- Jim Jarmusch (1)

- Jimmy DeSana (1)

- Jimmy Jim MacAulay (1)

- Joachim Trier (1)

- Joakim Eskildsen (1)

- Joan Acocella (10)

- Joan Didion (1)

- Joan Eardley (3)

- Joanna Biggs (1)

- Joanna Kavenna (1)

- João Fazenda (4)

- Jody Hewgill (1)

- Johanna Fateman (24)

- Johannes Vermeer (6)

- John Ashbery (5)

- John Berger (2)

- John C. Reilly (1)

- John Cheever (6)

- John Colapinto (2)

- John D'Agata (3)

- John F. Kennedy (1)

- John Gall (2)

- John Jeremiah Sullivan (3)

- John Keats (2)

- John Kinsella (4)

- John Lahr (6)

- John Lanchester (2)

- John Leonard (1)

- John MacDougall (19)

- John McPhee (121)

- John O'Hara (1)

- John Ruskin (2)

- John Russell (1)

- John Seabrook (25)

- John Szarkowski (2)

- John Updike (84)

- John Williams (1)

- Johnny Green (1)

- Jon Lee Anderson (10)

- Jon Michaud (1)

- Jon Qwelane (1)

- Jonathan Blitzer (6)

- Jonathan D. Spence (1)

- Jonathan Dee (1)

- Jonathan Demme (1)

- Jonathan Franzen (7)

- Jonathan Galassi (1)

- Jonathan Raban (24)

- Jordan Awan (1)

- Jorge Arevalo (1)

- Jorge Colombo (7)

- Jorie Graham (1)

- Jose Antonio Vargas (1)

- José Saramago (1)

- Joseph Brodsky (2)

- Joseph Conrad (2)

- Joseph Cornell (1)

- Joseph Lelyveld (1)

- Joseph Michael Lopez (3)

- Joseph Mitchell (22)

- Joseph O'Neill (1)

- Josh Cochran (1)

- Joshua Rothman (4)

- Joshua Yaffa (10)

- Joy Williams (5)

- Joyce Carol Oates (10)

- Juan Gris (1)

- Judith Thurman (20)

- Julia Ioffe (2)

- Julia Margaret Cameron (1)

- Julia Rothman (2)

- Julian Assange (1)

- Julian Barnes (2)

- Julian Bell (8)

- Julian Lucas (2)

- Julie Bruck (2)

- Julieta Cervantes (1)

- Julyssa Lopez (1)

- Justin Chang (1)

- Justin Quinn (1)

- Justin Trudeau (1)

- K. Leander Williams (1)

- Karen Kilimnik (1)

- Karen Solie (2)

- Karl Ove Knausgaard (3)

- Katherine Dunn (1)

- Katherine S. White (1)

- Kathryn Bigelow (1)

- Kathryn Paige Harden (1)

- Kathryn Schulz (8)

- Katie Orlinsky (1)

- Katie Roiphe (1)

- Katori Hall (1)

- Katy Grannan (1)

- Kay Ryan (1)

- Keith Gessen (7)

- Keith Haring (1)

- Keith Negley (2)

- Kelefa Sanneh (11)

- Kelly Reichardt (1)

- Ken Auletta (1)

- Kenneth Clark (1)

- Kenneth Tynan (4)

- Kevin Barry (2)

- Kevin Canty (1)

- Kevin Cooley (1)

- Kevin Dettmar (1)

- Kevin Mattson (1)

- Kevin Moore (1)

- Kirsten Ulve (1)

- Klauss Kremmerz (1)

- Krista Schlueter (2)

- Kyoko Hamada (1)

- Lafcadio Hearn (1)

- Lakin Ogunbanwo (1)

- Landon Nordeman (1)

- Langdon Hammer (1)

- Larissa MacFarquhar (2)

- Larry McMurtry (1)

- Larry Sultan (3)

- László Krasznahorkai (1)

- Laszlo Kubinyi (1)

- Laura Carlin (1)

- Laura Kipnis (1)

- Laura Miller (3)

- Laura Parker (5)

- Laura Preston (5)

- Lauren Collins (39)

- Lauren Hilgers (1)

- Lauren Lancaster (1)

- Laurent Cilluffo (4)

- Laurie Rosenwald (5)

- Laurie Winer (1)

- Lawrence H. Tribe (1)

- Lawrence Joseph (2)

- Lawrence Weschler (1)

- Lawrence Wright (1)

- Le War Lance (3)

- Leanne Shapton (3)

- Lee Gutkind (1)

- Lee Siegel (1)

- Leidy Churchman (1)

- Lena Herzog (1)

- Leo Espinosa (6)

- Leo Robson (9)

- Leo Steinberg (2)

- Leonard Garment (1)

- Leonardo da Vinci (2)

- Leslie Jamison (3)

- Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1)

- Lev Mendes (3)

- Lewis Thomas (1)

- Liam Hopkins (1)

- Lidija Haas (2)

- Lillian Ross (1)

- Linda Leavell (1)

- Lionel Stevenson (1)

- Lizzie Widdicombe (20)

- Lizzy Harding (1)

- London Review of Books (70)

- Lord Byron (1)

- Lore Segal (1)

- Lorenz Hart (1)

- Lorrie Moore (2)

- Los Angeles Review of Books (10)

- Louis Menand (14)

- Louise Brooks (1)

- Louise Erdrich (2)

- Louise Glück (2)

- Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne (2)

- Luca Guadagnino (2)

- Lucas Cranach (1)

- Lucian Freud (2)

- Lucie Brock-Broido (2)

- Lucy Raverat (1)

- Luigi Ghirri (1)

- Luis Grañena (1)

- Luke Mogelson (25)

- Lynda Bengalis (1)

- Lyndon B. Johnson (1)

- Lynn Freehill-Maye (1)

- Lynne Arriale (1)

- M. F. K. Fisher (3)

- M. Patterson (1)

- M. R. O'Connor (2)

- Maeve Dunigan (1)

- Maggie Doherty (1)

- Maggie Nelson (1)

- Mahatma Gandhi (1)

- Maile Meloy (2)

- Maira Kalman (3)

- Malcolm Gladwell (1)

- Malcolm X (1)

- Malika Favre (1)

- Manhola Dargis (1)

- Manning Marable (2)

- Marcel Proust (3)

- Marianne Moore (1)

- Marie Howe (1)

- Marina Warner (1)

- Marius Kociejowski (1)

- Mark Doty (2)

- Mark Ford (1)

- Mark Jarman (1)

- Mark Lyon (1)

- Mark Mazower (1)

- Mark Neville (2)

- Mark O'Connell (4)

- Mark Rothko (4)

- Mark Sandrich (1)

- Mark Singer (18)

- Mark Strand (2)

- Mark Svenvold (1)

- Mark Ulriksen (9)

- Mark Wang (1)

- Martin Amis (11)

- Martin Ansin (1)

- Martin Filler (1)

- Martin Schoeller (1)

- Martin Scorsese (1)

- Marvin Mudrick (1)

- Mary Karr (1)

- Mary Norris (1)

- Mary Price (2)

- Mary-Kay Wilmers (1)

- Masha Gessen (2)

- Matthew Hollister (2)

- Matthew Trammell (10)

- Maureen Gallace (2)

- Mauricio Lima (4)

- Mavis Gallant (3)

- Max Beckmann (2)

- Max Dalton (1)

- Maya Lin (1)

- McKenna Stayner (9)

- Megan Marshall (1)

- Meghan O'Rourke (4)

- Melissa Anderson (1)

- Meredith Jenks (2)

- Merve Emre (7)

- Michael Cavanagh (1)

- Michael Chabon (1)

- Michael Cimino (1)

- Michael Crawford (1)

- Michael Dirda (1)

- Michael Feinstein (1)

- Michael Fried (7)

- Michael Gillette (1)

- Michael Gorra (2)

- Michael Greenberg (1)

- Michael Heizer (1)

- Michael Hofmann (5)

- Michael Ondaatje (1)

- Michael Pearson (1)

- Michael Robbins (2)

- Michael Schulman (5)

- Michael Specter (6)

- Michael Sragow (3)

- Michael Winterbottom (1)

- Michael Wood (5)

- Michaelangelo Matos (8)

- Michel de Montaigne (1)

- Michelle Dean (1)

- Mid-Year Top Ten (15)

- Mike Brodie (1)

- Mike Nichols (2)

- Mike Peed (5)

- Mila Teshaieva (1)

- Mimi Sheraton (5)

- Min Heo (3)

- Min Jin Lee (1)

- Minna Zallman Proctor (1)

- Miriam Toews (1)

- Molly O'Neill (2)

- Molly Rankin (1)

- Morgan Elliott (1)

- Morgan Levy (1)

- Morgan Meis (1)

- Morten Strøksnes (2)

- Muhammad Ali (1)

- Muriel Belcher (1)

- Museums and Women (1)

- N. H. Pritchard (1)

- Nada Hayek (1)

- Nadav Kander (2)

- Nadine Ijewere (2)

- Naila Ruechel (4)

- Namwali Serpell (1)

- Nan Goldin (2)

- Nancy Franklin (1)

- Nancy Liang (1)

- Naomi Fry (2)

- Nate Chinen (1)

- Nathan Heller (10)

- Nathaniel Rich (1)

- Neal Ascherson (1)

- Neil Corcoran (1)

- Neil Sheehan (2)

- Neil Young (1)

- Neima Jahromi (4)

- Nellie McKay (1)

- New York Magazine (1)

- newyorker.com (42)

- Nicholas Breach (1)

- Nicholas Lemann (2)

- Nicholas Schmidle (17)

- Nicholson Baker (4)

- Nick Paumgarten (84)

- Nick Thorpe (1)

- Nicola Twilley (5)

- Nicolas Niarchos (16)

- Nicolas Poussin (1)

- Normal People (1)

- Norman Mailer (9)

- Norman Rockwell (2)

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan (1)

- NYR Daily (6)

- Olimpia Zagnoli (1)

- Oliver Sacks (6)

- On the Prison Highway (2)

- On the Rez (1)

- Orhan Pamuk (2)

- Orson Welles (4)

- Pablo Picasso (5)

- Paige Williams (3)

- Pankaj Mishra (2)

- Paolo Pellegrin (4)

- Pari Dukovic (8)

- Parul Sehgal (8)

- Pat Crow (1)

- Patricia Lockwood (2)

- Patricia Marx (6)

- Patrick Grant (1)

- Patrick Leger (1)

- Patrick Long (1)

- Patrick Radden Keefe (2)

- Patton Oswalt (1)

- Paul Berman (1)

- Paul Bowles (1)

- Paul Cézanne (4)

- Paul Farley (1)

- Paul Goldberger (1)

- Paul Graham (1)

- Paul Greenberg (1)

- Paul Mazursky (1)

- Paul McCartney (2)

- Paul Muldoon (1)

- Paul Rogers (1)

- Paul S. Amundsen (1)

- Pauline Kael (62)

- Pawel Pawlikowski (2)

- Penelope Gilliatt (1)

- Per Petterson (5)

- Personal History (8)

- Peter Bogdanovich (1)

- Peter Brooks (1)

- Peter Campbell (5)

- Peter Canby (2)

- Peter Doig (1)

- Peter Fisher (1)

- Peter Gay (2)

- Peter Hessler (15)

- Peter Jackson (1)

- Peter Schjeldahl (148)

- Peter Stark (1)

- Philip Connors (1)

- Philip Gefter (4)

- Philip Gourevitch (3)

- Philip Guston (2)

- Philip Larkin (7)

- Philip Montgomery (3)

- Philip Roth (2)

- Phillip Lopate (2)

- Phillip Toledano (1)

- Phyllis Ma (1)

- Piero della Francesca (1)

- Piet Mondrian (1)

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1)

- Ping Zhu (3)

- Pola Maneli (1)

- Postscript (16)

- Primo Levi (2)

- Quentin Tarantino (2)

- R. Kikuo Johnson (1)

- R. M. Patterson (5)

- Rachel Aviv (4)

- Rachel Carson (1)

- Rachel Domm (1)

- Rachel Felder (2)

- Rachel Monroe (1)

- Rachel Syme (8)

- Raffi Khatchadourian (18)

- Ralph Steadman (2)

- Ralph Waldo Emerson (1)

- Rebecca Mead (30)

- Rebecca Monk (2)

- Rebecca West (1)

- Redmond O'Hanlon (14)

- Renata Adler (8)

- Rereadings (4)

- Retrospective Reviews (2)

- Riccardo Vecchio (17)

- Richard B. Woodward (1)

- Richard Brody (85)

- Richard Buckle (1)

- Richard Cobb (1)

- Richard Diebenkorn (2)

- Richard Dorment (1)

- Richard Ellmann (4)

- Richard Franck Smith (1)

- Richard Holmes (1)

- Richard Linklater (1)

- Richard McGuire (1)

- Richard Merkin (1)

- Richard Pevear (1)

- Richard Preston (7)

- Richard Rodgers (1)

- Richard Schickel (1)

- Richard Serra (1)

- Richard Todd (1)

- Rita Dove (1)

- Rivka Galchen (20)

- Rob Brydon (2)

- Rob Fischer (1)

- Rob Garver (1)

- Robert A. Caro (5)

- Robert Adams (1)

- Robert Altman (1)

- Robert Andrew Parker (1)

- Robert B. Pippin (2)

- Robert Bresson (2)

- Robert Coates (1)

- Robert Coles (1)

- Robert Frank (1)

- Robert Gottlieb (2)

- Robert Guédiguian (1)

- Robert Hass (3)

- Robert Irwin (1)

- Robert Kushner (1)

- Robert Lowell (5)

- Robert Macfarlane (4)

- Robert Phelps (1)

- Robert Polidori (1)

- Robert Rauschenberg (3)

- Robert Risko (1)

- Robert Sullivan (29)

- Robert Weber (1)

- Roberto Calasso (1)

- Robin Robertson (1)

- Roe Ethridge (1)

- Roger Angell (9)

- Roger Strauss (1)

- Roland Barthes (6)

- Rollie McKenna (1)

- Roman Muradov (3)

- Ronald Blythe (1)

- Rose Wylie (1)

- Rosecrans Baldwin (1)

- Ross Landenberger (1)

- Route 3 (1)

- Roy Andries de Groot (1)

- Roy DeCarava (1)

- Roy Foster (1)

- Russell Baker (2)

- Ruth Bernard Yeazell (1)

- Ruth Franklin (3)

- Rutu Modan (1)

- Ryan Lizza (2)

- Ryan Ruby (1)

- Ryszard Kapuściński (2)

- S. F. Denton (1)

- Sabine Rewald (1)

- Saïd Sayrafiezadeh (1)

- Sallie Tisdale (3)

- Salman Toor (2)

- Salvatore Siano (1)

- Sam Alden (2)

- Sam Anderson (1)

- Sam Knight (2)

- Sam Shepard (1)

- Sam Sifton (1)

- Sam Wasson (2)

- Sam Youkilis (3)

- Samanth Subramanian (3)

- Samuel Johnson (1)

- Sandra M. Gilbert (1)

- Sanford Schwartz (12)

- Sarah Larson (10)

- Sarah Nicole Prickett (1)

- Sarah Stillman (2)

- Sasha Frere-Jones (8)

- Saul Bellow (5)

- Saul Friedländer (1)

- Saul Leiter (1)

- Saul Steinberg (2)

- Scaachi Koul (1)

- Seamus Heaney (14)

- Sean O'Brien (1)

- Serena Stevens (1)

- Sergei Diaghilev (1)

- Sergiy Maidukov (5)

- Serious Noticing (1)

- Seymour Hersh (1)

- Shae Detar (1)

- Shaped by This Land (1)

- Sharon Olds (1)

- Sharr White (1)

- Shauna Lyon (17)

- Sheila Yasmin Marikar (1)

- Shuffleton's Barber Shop (1)

- Siddhartha Mukherjee (2)

- Siegfried Kracauer (1)

- Sigmar Polke (1)

- Sigmund Freud (1)

- Silo No. 5 (1)

- Silvia Killingsworth (9)

- Simon Callow (1)

- Simon Norfolk (1)

- Simon Schama (5)

- Simon Winchester (1)

- Simone Massoni (3)

- Snowdon (2)

- Sofia Coppola (3)

- Sofia Yates (1)

- Sonny Rollins (1)

- Sophie Brickman (3)

- Sophie Taeuber-Arp (2)

- Sophy Hollington (1)

- Stacy Schiff (2)

- Stag at Sharkey's (1)

- Stanley Cavell (2)

- Stanley Chow (1)

- Stanley Crouch (1)

- Stefanie Augustine (1)

- Stephen Burt (2)

- Stephen Ellis (1)

- Stephen Jay Gould (2)

- Stephen Marche (1)

- Stephen Shore (2)

- Steve Coll (2)

- Steve Coogan (2)

- Steve Futterman (8)

- Steve Pyke (2)

- Steve Wilson (1)

- Steven Pinker (1)

- Steven Soderbergh (1)

- Stuart Jeffries (1)

- Subhankar Banerjee (1)

- Sue Song (1)

- Sundays with Updike (4)

- Susan Eilenberg (1)

- Susan Howe (1)

- Susan McCallum-Smith (1)

- Susan Orlean (6)

- Susan Sontag (16)

- Susan Stewart (1)

- Susan Tallman (2)

- Susannah Clapp (1)

- Susanne Lange (1)

- Sven Birkerts (1)

- Svetlana Alpers (4)

- Sybille Bedford (1)

- Sylvia Grinnell River (1)

- Sylvia Plachy (1)

- Sylvia Plath (1)

- T. J. Clark (16)

- Tables For Two (23)

- Tacita Dean (1)

- Tad Friend (21)

- Taking a Break (5)

- Talia Lavin (12)

- Tamara Shopsin (1)

- Tan Twan Eng (1)

- Tanya Tagaq (1)

- Tara McKelvey (1)

- Tarpley Hitt (1)

- Ted Conover (1)

- Ted Hughes (1)

- Teddy Wilson (1)

- Teju Cole (3)

- Terrance Malick (2)

- Terrance Rafferty (1)

- Terry Eagleton (1)

- The Crossing (3)

- The Egg Men (2)

- The Elements of Style (2)

- The Encircled River (4)

- The Hudson Review (1)

- The Kid with a Bike (4)

- The Long Goodbye (1)

- The New Republic (2)

- The New York Review of Books (109)

- The New York Times (25)

- The New York Times Magazine (10)

- The New York Times Sunday Book Review (23)

- The New Yorker (1136)

- The Painted Drum (1)

- The Paris Review (4)

- The Patch (2)

- The Social Network (4)

- The Talk Of The Town (16)

- The Turkey Season (3)

- The Virginia Quarterly Review (1)

- The Walrus (1)

- Theo Jansen (1)

- Therese Mitchell (1)

- This Cold Heaven (1)

- Thomas Beller (1)

- Thomas Berenato (1)

- Thomas Kunkel (1)

- Thomas Mallon (6)

- Thomas Mann (1)

- Thomas McGuane (1)

- Thomas Meaney (1)

- Thomas Powers (3)

- Thomas Prior (5)

- Thomas Struth (3)

- Thomas Wågström (1)

- Thurman and Lepore: Two Superb "New Yorker" Essayists (1)

- Tim Butcher (6)

- Timothy Ferriss (1)

- Tina Barney (1)

- Tom Bachtell (10)

- Tom Forrestall (1)

- Tom Kizzia (2)

- Tom Smart (1)

- Tom Wolfe (1)

- Toma Vagner (4)

- Tomas Transtromer (1)

- Tommy Flanagan (1)

- Tony Bennett (2)

- Tony Cenicola (1)

- Tony Judt (1)

- Top Ten Exhibition Reviews (10)

- Top Ten New Yorker & Me (4)

- Top Ten New Yorker Pieces 2023 (1)

- Top Ten Nick Paumgarten Pieces (10)

- Toward My Own Theory of Description (12)

- Tracy Kidder (1)

- Travels In Siberia (8)

- Travis B. (1)

- Trent Reznor (1)

- Truman Capote (3)

- Tsukasa Kodera (1)

- Tyler Hicks (1)

- V. S. Pritchett (6)

- Vanessa Bell (1)

- Vanessa Winship (1)

- Verlyn Klinkenborg (6)

- Victor J. Blue (2)

- Victor Schrager (1)

- Victoria Patterson (1)

- Viet Thanh Nguyen (2)

- Vince Aletti (9)

- Vincent Mahé (1)

- Vincent van Gogh (13)

- Vinson Cunningham (4)

- Virginia Woolf (1)

- Vladimir Nabokov (10)

- W. G. Sebald (7)

- W. H. Auden (1)

- W. S. Merwin (1)

- Walker Evans (7)

- Wallace Stevens (3)

- Wayne Koestenbaum (4)

- Wayne Thiebaud (6)

- Wei Tchou (5)

- Wendell Steavenson (1)

- Werner Herzog (1)

- Wesley Allsbrook (1)

- Where the Water Goes (1)

- White Sands (1)

- Whitney Balliett (26)

- Wil Counts (1)

- Wilfrid Sheed (2)

- Wilhelm Sasnal (1)

- Will Counts (1)

- Willa Cather (1)

- William Atkins (1)

- William Blake (1)

- William Carlos Williams (4)

- William Christenberry (1)

- William Eggleston (2)

- William Faulkner (1)

- William Finnegan (14)

- William Gibson (1)

- William Grimes (1)

- William Henry Jackson (1)

- William L. Howarth (2)

- William Logan (1)

- William Maxwell (1)

- William Mebane (12)

- William Murray (1)

- William S. Burroughs (2)

- William Shawn (8)

- William Strunk (8)

- William Styron (1)

- William Zinsser (3)

- Winslow Homer (1)

- Wolfgang Tillmans (2)

- Woody Allen (3)

- Wright Morris (1)

- Xan Rice (1)

- Yashar Kemal (1)

- Yolanda Whitman (2)

- Young Farmers (1)

- Yudhijit Bhattacharjee (1)

- Yudi Ela (1)

- Yuja Wang (1)

- Zach Helfand (1)

- Zachary Fine (2)

- Zachary Lazar (1)

- Zachary Zavislak (1)

- Zack Hatfield (1)

- Zadie Smith (11)

- Zbigniew Herbert (1)

- Zeina Durra (1)

- Zoë Heller (1)

- Zoe Strauss (1)

- Zora J. Murff (2)

Popular Posts

Blog Archive

- ► February (1)

- ► March (3)

- ► April (5)

- ► May (3)

- ► June (7)

- ► July (7)

- ► August (5)

- ► September (6)

- ► October (7)

- ► November (9)

- ► December (9)

- ► January (9)

- ► February (9)

- ► March (9)

- ► April (7)

- ► May (9)

- ► June (8)

- ► July (14)

- ► August (8)

- ► September (7)

- ► October (8)

- ► November (5)

- ► December (11)

- ► January (10)

- ► February (5)

- ► March (8)

- ► May (6)

- ► June (6)

- ► July (6)

- ► August (9)

- ► October (9)

- ► November (8)

- ► December (8)

- ► January (7)

- ► February (4)

- ► April (3)

- ► July (8)

- ► August (4)

- ► November (6)

- ► December (6)

- ► January (6)

- ► February (7)

- ► April (6)

- ► May (5)

- ► July (4)

- ► October (6)

- ► February (6)

- ► March (10)

- ► April (10)

- ► May (8)

- ► August (6)

- ► November (7)

- ► December (13)

- ► January (8)

- ► March (7)

- ► April (8)

- ► June (9)

- ► July (12)

- ► September (10)

- ► December (12)

- ► April (9)

- ► May (7)

- ► June (5)

- ► July (9)

- ► August (10)

- ► September (13)

- ► October (5)

- ► January (12)

- ► September (5)

- ► December (16)

- ► May (11)

- ► June (10)

- ► August (17)

- ► September (8)

- ► October (14)

- John McPhee's "Brigade de Cuisine" Retitled

- October 28, 2019 Issue

- Becka Viau's "Young Farmers"

- November 4, 2019 Issue

- Interesting Emendations: Jonathan Franzen's "The E...

- Roger Angell's Elegiac Impulse

- Susan Sontag's "Fascinating Fascism": Wolcott v. M...

- November 11, 2019 Issue

- November 18, 2019 Issue

- Describing Nazi and Soviet Prison Camps: Frazier a...

- Dan Kois' "How I Learned to Cycle Like a Dutchman"

- ► December (15)

- ► January (16)

- ► March (12)

- ► April (11)

- ► May (15)

- ► June (13)

- ► September (12)

- ► October (13)

- ► November (12)

- ► December (19)

- ► December (17)

- ► May (10)

- ► August (11)

- ► September (17)

- ► October (10)

- ► November (10)

- ► January (13)

- ► March (11)

- ► July (21)

- ► January (11)

- Adam Shoalts, Beyond the Trees (2019)

- Adam Weymouth, Kings of the Yukon (2018)

- Aleksandar Hemon, The Book of My Lives (2013)

- August Kleinzahler, Sallies, Romps, Portraits and Send-Offs (2017)

- Ben McGrath, Riverman (2022)

- Bill Buford, Dirt (2020)

- Burkhard Bilger, Fatherland (2023)

- C. K. Williams, On Whitman (2010)

- Charles Simic, The Life of Images (2015)

- Colm Tóibín, On Elizabeth Bishop (2015)

- Curtis Sittenfeld, You Think It, I'll Say It (2018)

- Eleanor Cook, Elizabeth Bishop at Work (2016)

- Geoff Dyer, Otherwise Known as the Human Condition (2011)

- Geoff Dyer, See/Saw (2021)

- Geoff Dyer, The Last Days of Roger Federer (2022)

- Geoff Dyer, The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand (2018)

- Geoff Dyer, White Sands (2016)

- Gideon Lewis-Krauss, A Sense of Direction (2012)

- Helen Vendler, Last Looks, Last Books (2010)

- Helen Vendler, The Ocean, the Bird and the Scholar (2015)

- Ian Frazier, Hogs Wild (2016)

- Ian Frazier, Travels in Siberia (2010)

- James Wolcott, Critical Mass (2013)

- James Wood, Serious Noticing (2019)

- James Wood, The Fun Stuff (2012)

- James Wood, The Nearest Thing to Life (2015)

- Janet Malcolm, Forty-one False Starts (2013)

- Janet Malcolm, Iphigenia in Forest Hills (2011)

- Janet Malcolm, Nobody's Looking at You (2019)

- Janet Malcolm, Still Pictures (2023)

- Jill Lepore, Joe Gould's Teeth (2015)

- Jill Lepore, The Deadline (2023)

- John Lahr, Joy Ride (2015)

- John McPhee, Draft No. 4 (2017)

- John McPhee, Silk Parachute (2010)

- John McPhee, Tabula Rasa (2023)

- John McPhee, The Patch (2018)

- John Updike, Always Looking (2012)

- John Updike, Higher Gossip (2011)

- Jonathan Franzen, The End of the End of the Earth (2018)

- Jonathan Raban, Driving Home (2010)

- Joyce Carol Oates, In Rough Country (2010)

- Judith Thurman, A Left-Handed Woman (2022)

- Julian Bell, Van Gogh (2015)

- Keith Gessen, A Terrible Country (2018)

- Lawrence Osborne, The Wet and the Dry (2013)

- Martin Amis, The Rub of Time (2018)

- Michael Hofmann, Where Have You Been? (2014)

- Morten Strøksnes, Shark Drunk (2018)

- Nicholson Baker, The Way the World Works (2012)

- Per Petterson, I Curse the River of Time (2010)

- Peter Hessler, Strange Stones (2013)

- Peter Schjeldahl, Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light (2019)

- Robert Hass, What Light Can Do (2012)

- Robert Macfarlane, The Old Ways (2012)

- Roger Angell, This Old Man (2015)

- Samanth Subramanian, Following Fish (2010)

- Svetlana Alpers, Walker Evans (2020)

- T. J. Clark, Heaven on Earth (2018)

- T. J. Clark, If These Apples Should Fall (2022)

- T. J. Clark, Picasso and Truth (2013)

- Verlyn Klinkenborg, More Scenes from the Rural Life (2013)

- Wayne Koestenbaum, My 1980s & Other Essays (2013)

- William Atkins, The Moor (2014)

- Zadie Smith, Feel Free (2018)

John MacDougall

Extremely Online and Wildly Out of Control

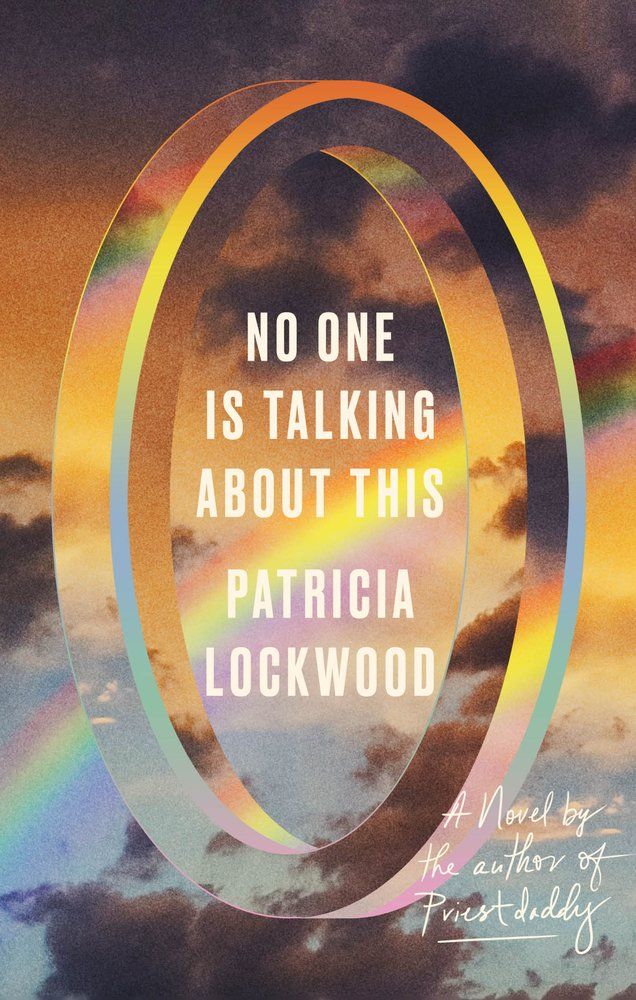

Patricia Lockwood’s debut novel explores the mind, and heart, of an internet-addled protagonist.

/media/video/upload/Coffin16X9.mp4)

This article was published online on February 13, 2021.

O n an Instagram account that I like, an illustrator publishes little four-panel drawings of smooth-headed aliens doing normal human things. Two aliens with bodies like slim light bulbs encounter each other against a bubblegum-pink background. One is sitting in a chair, reading a book; the other is just poking its head in, as if to say hello: “What are you doing?” The reading alien looks up from its book. “ Forming emotional bonds, ” it replies.

“If I am successful I will be despondent upon completion.”

“Well I hope you are devastated,” the friend says, warmly.

“Thank you—lowering my defenses,” the reading alien says with a jaunty hand gesture.

In another drawing , an alien gives an earbud to a friend. “Put this in your head,” it says. “I want you to hear vibrations that affect my emotions.” “So that mine are also affected?” the alien’s friend asks. “If all goes as planned,” the first replies.

What I like about this particular cartoon series , called Strange Planet , drawn by the artist Nathan W. Pyle, is that it presents the most mundane human actions—reading a novel, wanting a friend to hear and appreciate your sad music—out of context and in unfamiliar language. We’re so weird , I find myself saying, while snort-laughing, looking at my own behaviors in this frame. Why are we like this?

Recommended Reading

Poet on the Edge

Lucia Berlin’s Harrowing, Radiant Fiction

The Death of the Pioneer Myth

This is the experience—snort-laughter mixed with bewilderment at the absolute strangeness of the world in which I participate—that I tend to have when reading Patricia Lockwood, the poet turned memoirist and London Review of Books essayist who has now published her first novel, No One Is Talking About This . The novel follows a protagonist who is “extremely online,” a genius of the “portal,” as the internet is called here, and naturally adept at the cleverness and absurdity of social-media exchange. She has become famous for it. Recently, she has gained worldwide recognition for a post that says, in its entirety, “Can a dog be twins?” Her cat’s name is Dr. Butthole. She travels the world, invited to speak about the portal—both as an interpreter of its patterns and as a performer of its bizarre and hilarious argot.

“Stream-of-consciousness!” she shouts to an audience in Jamaica. “Stream-of-consciousness was long ago conquered by a man who wanted his wife to fart all over him. But what about the stream-of-a-consciousness that is not entirely your own? One that you participate in, but that also acts upon you?”

These are the driving questions of No One Is Talking About This . What happens to a mind that has enthusiastically joined a worldwide Mind, yet can still occasionally see—if only in flashes—the perversity of the exercise? “Modern womanhood was more about rubbing snail mucus on your face than she had thought it would be. But it had always been something, hadn’t it?” Lockwood’s narrator notes. Elsewhere: “She had a crystal egg up her vagina. Having a crystal egg up her vagina made it difficult to walk, which made her thoughtful, which counted as meditation.”

Where do these thoughts come from? Who made them? How did it come to be that we now have crystal eggs up our vaginas?

Already it was becoming impossible to explain things she had done even the year before, why she had spent hypnotized hours of her life, say, photoshopping bags of frozen peas into pictures of historical atrocities, posting OH YES HUNNY in response to old images of Stalin, why whenever she liked anything especially, she said she was going to “chug it with her ass.” Already it was impossible to explain these things.

I first encountered Lockwood, as many people did, on Twitter , where she has a large and devoted fandom, and where her current profile bio identifies her as a “hardcore berenstain bare-it-all.” One of the early Twitter projects that won her readers, circa 2011, was a series of “sexts” riffing on what was at the time an ascendant phenomenon of interpersonal communication, and turning it into a poetic mode.

“ Sext : I am a living male turtleneck. You are an art teacher in winter. You put your whole head through me.” “ Sext : I get nude as hell. I write BRA on my boobs and JEAN SHORTS on my pelvis. I walk through a philosophy class and I am not arrested.”

This kind of weird, slyly sophisticated humor, and a deep commitment to the profane as a tool for revelation and critique, are hallmarks of Lockwood’s style. Her high-low panache extends to her fierce and wonderful literary criticism for the London Review of Books , where she’s written about Vladimir Nabokov, John Updike, Carson McCullers, Joan Didion, and others. About Didion, she remarks: “It would be possible to write a parody of her novels called Desert Abortion—in a Car . Possible, but why? The best joke you could make wouldn’t touch her.”

Despite her concerns about the individual mind’s dilution in the great tidal insanity of Online Discourse, Lockwood is a stylist who only ever sounds like herself. Her first poetry collection, Balloon Pop Outlaw Black (2012), contains poems with titles like “Killed With an Apple Corer, She Asks What Does That Make Me” and “The Salesmen Open Their Trenchcoats, All Filled With Possible Names for the Watch.” Penguin published her second collection, Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals , in 2014 after one of its poems went viral, a response to a public debate at the time about whether rape jokes could ever be funny, which played out within a larger debate about whether women were categorically less funny than men. “The rape joke is that you were 19 years old,” the poem begins. “The rape joke is that he was your boyfriend … The rape joke is he was a bouncer, and kept people out for a living / Not you!”

“Rape Joke” established Lockwood’s talent for speaking the language of the zeitgeist and knifing the zeitgeist’s heart in the same gesture—her ability to win at both humor and lacerating critique. In her 2017 memoir, Priestdaddy , Lockwood recounts growing up as the daughter of one of the only married Catholic priests in the world (her father had been a Lutheran minister, but petitioned to be reordained ), which gives some context to her sensibility: She weaponizes hyperbole and irreverence as only a person raised on Roman Catholicism and then weaned on the internet can. In Priestdaddy , when she’s asked for descriptions of her poetry to fuel “the machinery of book publication,” she considers suggesting as her plaudit: “Electrifying … like if a bumblebee stang you right on the clit.”

From the May 2017 issue: James Parker on Patricia Lockwood’s ‘Priestdaddy’

Lockwood’s affinity for the surreal, for baroque wit, for the sexually weird, for the inane and shocking—for the “worst things the English language is capable of,” as she phrased it to The New York Times Magazine —has made her one of the most interesting writers of the past 10 years. It has also made her a master of Twitter. ( Her feed remains disturbing and hilarious . In November, she posted the back end of an uncastrated hog, generously endowed. Another time : “Was asked to pitch something to a ‘women’s magazine’ and the first thing that came to mind was ‘Covid Gave Me Really Soft Pubes Like A Chinchilla’ … but on second thought I’ll be saving that for a men’s magazine.”) But in No One Is Talking About This , Lockwood betrays suspicion of the skills that she wields with relish. She turns her critical streak toward the medium in which her writing, and her public life, has been forged.

The first half of No One Is Talking About This has the feeling of an endless scroll—it’s largely made up of brief, one-to-four-sentence increments, approximately tweet-length, rendered in super-close third person. These seem to have little relation to one another chronologically, and they don’t proceed logically. Instead, they are sporadic and self-contained: a joke, a story, a note, a question, a pithy comment. They pass the way social-media feeds pass. “Why were we all writing like this now?” the protagonist wonders. “Because a new kind of connection had to be made, and blink, synapse, little space-between was the only way to make it. Or because, and this was more frightening, it was the way the portal wrote.”

The portal, the protagonist realizes, “had also once been the place where you sounded like yourself. Gradually it had become the place where we sounded like each other, through some erosion of wind or water on a self not nearly as firm as stone.” She meets people at events on her tours who remember her old blog, and she remembers their blogs. “Tears sparked in her eyes instantaneously … His had been one of her very favorite lives.” But is any of this real? Real to whom? Real in what sense? Anyway, the self (whose self?) devised on the internet vanishes. “Myspace was an entire life,” she half-sobs at an event. “And it is lost, lost, lost, lost!”

The narrator’s endless, directionless tumble in time and language is interrupted by the hard stop of a very offline tragedy. Her younger sister, who is “leading a life that was 200 percent less ironic than hers,” is pregnant, and something has gone terribly wrong. The baby has Proteus syndrome, which causes tissues in some parts of the body to grow far out of correct proportion. The baby’s head is too big: She’s unlikely to survive birth, and certainly won’t survive infancy.

Proteus syndrome is a poetic choice here, an ironic choice even. It is a biological hyperbole suited to the sensibilities of the internet: runaway proliferation turning the body into a wildly exaggerated, Daliesque version of itself. It is surreality visited on the human form. With a less skillful writer, this would be a heavy-handed—or worse, manipulative—plot device, but the baby and her terminal condition turn the book into something unexpected: not a tragedy, but a romance. The baby is born and—improbably—survives, and Lockwood’s narrator is immediately and wholly lovestruck by this tiny creature and her runaway everything. “In every reaching cell of her she was a genius.” She is obsessed with the baby’s body, with the way the baby experiences the world purely physically and not in her mind, or in The Mind.

Her fingertips, her ears, her sleepiness and her wide awake, a ripple along the skin wherever she was touched. All along her edges, just where she turned to another state … The self, but more, like a sponge.

Through this baby, the narrator falls out of the life she spent “with a notebook, painstakingly writing ‘ oh my god—thor’s hammer was a chode metaphor ’ with a feeling of unbelievable accomplishment.” She falls “out of the broad warm us, out of the story that had seemed, up till the very last minute, to require her perpetual co-writing.” Now she realizes that it doesn’t need her co-writing, and that she maybe doesn’t care.

Through the membrane of a white hospital wall she could feel the thump of the life that went on without her, the hugeness of the arguments about whether you could say the word retard on a podcast. She laid her hand against the white wall and the heart beat, strong and striding, even healthy. But she was no longer in that body.

Lockwood uses the same language to describe the internet—a broad, warm body; a strong heartbeat—and the fragile corporeality of the baby, though those two domains are mutually incompatible. The baby the narrator can hold in her arms; the baby is broken and holy. The internet is elsewhere, voracious, profane. But they act on her similarly. The internet is a collective reality that swallows and reconfigures us—it is a kind of corpus. And so, of course, is the one truly universal human experience: confronting mortality. The truth of the body that suffers and fails is a reality—a hyper-reality, an inevitability—just as ready to swallow and reconfigure her. Which body does this narrator love? To which does she wish to ultimately belong?

Fortunately, Lockwood doesn’t make her narrator piously renounce her wild tweeting in favor of the “real world,” whatever that might mean. There’s a joke (on the internet) about the “broken brain”—“The internet broke my brain,” people commonly lament. The narrator has a broken brain, still; it’s just that now she has an incandescently broken heart, too. Sitting next to the baby, who is struggling to breathe, she is Googling Ray Liotta’s plastic surgery. She is telling the baby about Marlon Brando because “one of the fine spendthrift privileges of being alive [is] wasting a cubic inch of mind and memory on the vital statistics of Marlon Brando.” She is grieving and scrolling. Reading this, I suddenly remembered sitting in a hospital room, next to a loved one on a ventilator, and trying to scroll back through years of images online of some random dancer’s nondancing twin to see whether she, too, had a fraught relationship with her arms on account of having been raised in a religious cult. We’re so weird. Why are we like this?

The second half of the book, in which the narrator is newly deranged by the immovable reality of loving what must die—in addition to being deranged by the portal, which feels, by contrast, both eternal and editable—is electric with tenderness. “The doors of bland suburban houses now looked possible, outlined, pulsing—for behind any one of them could be hidden a bright and private glory.” She becomes like the baby, who “could not tell the difference between beauty and a joke.”

Lockwood’s genius for irony is matched by the radiance of her reverence, when she lets it show. A glory, the portal tells her, is also what you call the round rainbow that plane passengers sometimes see haloing the plane’s shadow as it moves through mist. “Every time she looked out the window it was there, traveling fleetly over clouds that had the same dense flocked pattern that had begun to appear on the baby’s skin, the soles of her feet and palms of her hands, so she seemed to have weather for finger and footprints.” Glories follow her through the sky, made only of water and light. Unusually for me, I wept through parts of this book, but in the best, beautiful-sad-music way—a grand success, the aliens would say.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

News, Notes, Talk

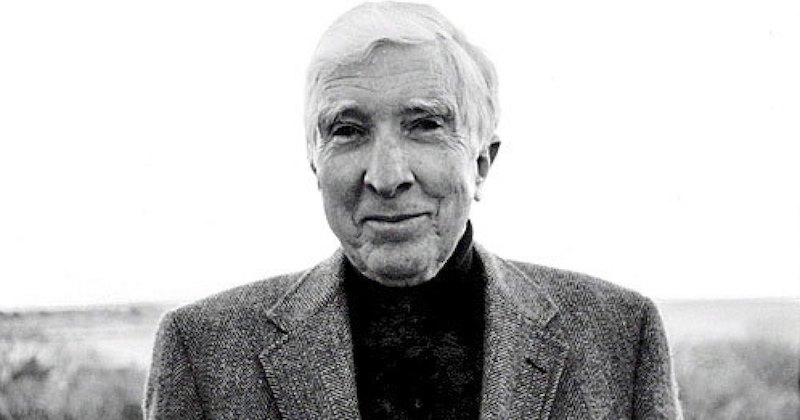

Here are a few of John Updike’s kindest, most cutting literary pans.

John Updike, with one notable exception , was an incredibly kind reviewer. Patricia Lockwood, in her London Review of Books survey of Updike’s work , observed Updike’s criticism “was not just game and generous but able, as his fiction is not, to reach deeply into the objectives of other human beings.” In the introduction to his 1975 collection Picked-Up Pieces , his list of rules for literary criticism began thus: “Try to understand what the author wished to do, and do not blame him for not achieving what he did not attempt.”

This empathy is also what makes his criticism so cutting, when it is: it’s done with a deep understanding of the reviewed work’s goal, and a generosity and willingness to praise what is good. I see what you’re attempting, a noble task, says the review; Here are your many good qualities; and, before I go, I noticed that you have—by the rules you’ve set out for yourself—a tiny problem which knocks down the house of cards that is your book. Like a kind coach clapping the authors he reviews on the shoulder, saying, Better luck next time ! Here are some of Updike’s kind-but-unkind takedowns:

On Salman Rushdie’s Shalimar the Clown :

Verbal hyperactivity of the sissy-Assisi sort nudges the hip reader on page after page . . . James Joyce and T. S. Eliot established brainy allusions as part of modernity’s literary texture, but at the risk of making the author’s brain the most vital presence on the page . . . His fascination with fame and theatricality, movies and rock music . . . gives his fiction a distracting glitter, like shaken tinsel.

On Flann O’Brien’s career and At-Swim-Two-Birds :

His novels begin with a swoop and a song but end in an uncomfortable murk and with an air of impatience . . . The elder Trellis is kept immobilized in his bed by surreptitiously drug-induced sleep while his characters, including a number of American cowboys recruited from the novels of one William Tracy, run wild. At least, that’s what I think is happening.

On Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close

[The novel,] on its local ground, seems thinner, overextended, and sentimentally watery . . . Foer is, I would say, a naturally noisy writer—a natural parodist, a jokester, full of ideas and special effects, keen to keep us off balance and entertained. The novel’s very title, “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close,” suggests the kind of impact he wants to make on the reader. But a little more silence, a few fewer messages, less graphic apparatus might let Foer’s excellent empathy, imagination, and good will resonate all the louder.

On Robert Alter’s translation of The Five Books of Moses:

In this age of widespread education and flagging creativity, new translations abound.

On Norman Rush’s Mortals :

Ray Finch, the hero of Norman Rush’s lengthy new novel, “Mortals,” finds many things annoying . . . Iris and Ray have been married for seventeen years, and she gives signs of having the seventeen-year itch. This is less surprising to the reader than to Ray, who is perhaps the most annoying hero this reviewer has ever spent seven hundred pages with.

. . . It is annoying, one could say, that a novel demonstrating so acute, well-stocked, and witty a sensibility is such a trial to read.

On Tom Wolfe’s A Man in Full :

A Man in Full . . . amounts to entertainment, not literature, even literature in a modest aspirant form. Like a movie desperate to recoup its bankers’ investment, the novel tries too hard to please us.

Well, that one was mean. Happy birthday, John Updike!

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

to the Lithub Daily

April 9, 2024.

- On Octavia Butler, Audre Lorde, and the power of pleasure

- Maggie Nelson talks to Lauren Michele Jackson

- The most challenged books of 2023 are probably exactly what you expect

Lit hub Radio

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

No One is Talking About This – Patricia Lockwood

[Riverhead; 2021]

When I first encountered Patricia Lockwood in her spirited reappraisal of John Updike in the London Review of Books , it felt like a revelation. Insight, asperity, un-pompous erudition — the perfect potion, it seemed — spilled delightfully onto the page. Here was a writer worth watching.

A quick Internet search told me that I was late to the party, as she’d already established a reputation as a poet and author of an acclaimed memoir, Priestdaddy (2017), while publishing essays and cultural criticism. So the release of her first novel, No One Is Talking About This , was much-anticipated, not merely in terms of media buzz, but by real readers, by which I mean, of course, myself.

Written in fragments, the novel is divided into two sections, centered on an unnamed protagonist who is an Internet celebrity and expert on digital media, pursuing her career on the international lecture circuit. The first part depicts her as nervously at home in these elements, surveying the virtual landscape and the evolving virtual inscape while traversing the planet’s time zones. In all contexts, the Internet, Twitter et al. are collectively referred to as “the portal.”

The second part of the novel shifts to a crisis in the non-virtual world, where the protagonist’s sister experiences a harrowing pregnancy and the birth of a baby with a rare genetic disorder called Proteus syndrome. Born blind and suffering from a grave assortment of health issues, the infant survives only six months, but during her brief life, she inspires a deep, transformative love in the sisters.

The stark contrast between the two parts is crucial to the novel’s design. One could imagine the author riffing longer in the first part and writing a timely stand-alone “Internet novel.” As the narrator asserts, “All writing about the portal so far had a strong whiff of old white intellectuals being weird about the blues, with possible boner involvement.” Or, similarly, the author could have developed the second part into a memoir-inflected autofiction.

Instead, by presenting these contrasting parts as a whole, Lockwood attempts something more ambitious, formally speaking. Overall, I don’t think the novel succeeds — more about that later — but in its best moments, the stylized fragments of No One is Talking About This are original and compelling. Here, she conveys a perception of police violence:

The labored officious breathing of the policemen, which was never the breathing that stopped. The poreless plastic of nightsticks, the shields, the unstoppable jigsaw roll of tanks, the twitch of a muscle in her face where she used to smile at policemen . . .

Both visceral and minutely observed (“poreless plastic”), this description might lazily be described as “poetic” but that would miss the mark. Although the author is also a poet, her prose offers a welcome reminder that poetry has no monopoly on sensuous language. Some novelists write as if the bare pine aesthetic of an Ikea bookshelf has leached into their style; Lockwood wants nothing of this. Consider the passage when the protagonist meets her newborn niece:

All the worries about what a mind was fell away as soon as the baby was placed in her arms. A mind was merely something trying to make it in the world. The baby, like a soft pink machete, swung and chopped her way through the living leaves. A path was a path was a path was a path. A path was a person and a path was a mind, walk, chop, walk, chop.

Until this moment, the main character has been preoccupied with trying to capture the “communal stream-of-consciousness” of the portal. She chronicles its antic dippiness and aleatory profundity, while musing about its effects on fashion, language, politics, and consciousness itself. Many of these fragments are cleverly done, but they’re not exactly news. I was reminded of Jennifer Egan’s inclusion of a PowerPoint format in A Visit from the Goon Squad, which might have felt technically daring in 2011 but now, only a decade later, seems quaint. There’s a similar problem here, as web novelty is dated as soon as the pixel fades.

This problem is most palpable in fragments which rely less on wit than on a kind of whimsy. Lockwood’s frankness can be refreshing but sometimes her ear fails her. Words like butthole or ass are treated as cutely transgressive — there’s definitely a puritanical edge here — and the protagonist enjoys chuckling at her own jokes. Though she supposedly travels extensively, there are few cultural particulars as countries blend into a duty-free pudding, where everybody speaks English and there is scant intimation of places outside of a touristic comfort zone. The same is true of the portal: it’s a monolingual monolith. For all its expressed angst about current American political woes (racism, violence, Trump as “dictator,” etc.) or hip cringing at old pop culture (“Sweet Caroline”), the novel evinces an unwitting sort of American triumphalism.

Thus, the second part of No One is Talking About This provides a salutary jolt. Here, the protagonist finds herself utterly disarmed by a baby whose condition defies easy answers or facile questions about “what does this meme?” Another world beckons, full of menace and promise, as she feels attracted to the child.

“I can do something for her,” she tried to explain to her husband, when he asked why she kept flying back to Ohio on those rickety $98 flights that had recently been exposed as dangerous by Nightline. “A minute means something to her, more than it means to us. We don’t know how long she has — I can give them to her, I can give her my minutes.” Then, almost angrily, “What was I doing with them before?

Like an observer in a 21 st century version of Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” she has concluded: you must change your life. Only in her case, the inspiration is not art but life itself, in one of its most challenging iterations. She becomes devoted to the baby, sharing with it as much life as she can. Songs, the sensation of a dog’s tongue on her body. Her own physical contact. And when the baby dies, there is the inevitable question of what it all meant. This is evoked in a conversation with a doctor:

The doctor took a bite of bagel and shaped his mouth the great word why . “When Jesus met the blind man, his disciples asked him why — was it the man’s sin, was it the sin of his parents? And Jesus said it was no one’s sin, that it happened so that God might move us forward, through and with and in that man.” Tears stood without falling in the doctor’s blue eyes; that is the medicine, she thought. “If I can do anything . . .” he said chokingly, with a slight amount of cream cheese in his mustache, which increased her love for the human race, which moved her forward through, with, in him, which was also for the glory of mankind.

This passage raises many questions about suffering and existence, and of course it’s not a flaw in a novel if these questions remain unanswerable or are selectively filtered through a character. Here and elsewhere the protagonist experiences an awakened love for humanity and a movement forward which is also for “the glory of mankind.” Her sister says of her valiant efforts with the dying child, “I would’ve done it for a million years.”

But here’s another question, largely unaddressed: how much can we instrumentalize the suffering of others? It is precisely the suffering of children that prompts Ivan Karamazov’s rebellion, his desire to “return the ticket.” Clearly Lockwood embraces another narrative, perhaps one of mystery (“Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth?” God tells Job), and that is indeed an answer with a long (and for some, venerable) history. But, in a novel couched in the religious terms that Lockwood is using, Ivan and his rebellious ilk ought to have at least been given a hearing, if only to be rejected. It would have been interesting to see how a writer of Lockwood’s talents would confront the question.

My first impression that Patricia Lockwood is a writer worth watching remains intact. But No One is Talking About This is an uneven performance. Its style cannot fix its gaps. The world of the portal described here is less a world than a province of the U.S.A. Its voice is powerful but unrelieved by other voices, by a readiness to put into question its own articulateness. That said, this is a wildly ambitious novel, so even a qualified success, or failure, is to its credit.

C harles Holdefer is an American writer based in Brussels. His work has appeared in the New England Review, North American Review, Chicago Quarterly Review and in the Pushcart Prize anthology. His latest book is AGITPROP FOR BEDTIME (stories) and his next novel, DON’T LOOK AT ME, will be released in 2021. Visit Charles at www.charlesholdefer.com

This post may contain affiliate links.

Full Stop Quarterly: Fall 2023

Out latest issue illuminates the role of literature, art, and other cultural practices in contemporary social movements related to the land. Read the introduction here.

THE JOHN UPDIKE SOCIETY

Celebrating one of the most significant american writers of the 20th century.

Is John Updike a ‘Malfunctioning Sex Robot’?

That’s the charge Patricia Lockwood levels after she’s charged with reading and reviewing Novels, 1959-65: The Poorhouse Fair; Rabbit, Run; The Centaur; Of the Farm, by John Updike for the London Review of Books . And she skewers Updike with the kind of zest the likes of which haven’t been seen since David Foster Wallace (quoted here) used to pillory Updike (“a penis with a thesaurus”) and other “Great White Male Narcissists.” It’s almost as if she’s hoping one of her own derogatory turns-of-phrase will be likewise immortalized.

She confesses her bias openly, in the first paragraph: “I was hired as an assassin. You don’t bring in a 37-year-old woman to review John Updike in the year of our Lord 2019 unless you’re hoping to see blood on the ceiling.” She writes, “In a 1997 review for the New York Observer, the recently kinged David Foster Wallace diagnosed how far Updike had fallen in the esteem of a younger generation. ‘Penis with a thesaurus’ is the phrase that lives on. . . . Today, he has fallen even further, still, in the pantheon but marked by an embarrassed asterisk: DIED OF PUSSY-HOUNDING. No one can seem to agree on his surviving merits. He wrote like an angel, the consensus goes, except when he was writing like a malfunctioning sex robot attempting to administer cunnilingus to his typewriter. Offensive criticism of him is often reductive, while defensive criticism has a strong flavour of people-are-being-mean-to-my-dad. There’s so much of him, spread over so much time, that perhaps everyone has read a different John Updike. . . . The more I read of him the more there was, like a fable.”

“When he is in flight you are glad to be alive. When he comes down wrong—which is often—you feel the sickening turn of an ankle, a real nausea. All the flaws that will become fatal later are present in the beginning. He has a three-panel cartoonist’s sense of plot. The dialogue is a weakness: in terms of pitch, it’s half a step sharp, too nervily and jumpily tuned to the tics and italics and slang of the era. And yes, there are his women. Janice is a grotesquerie with a watery drink in one hand and a face full of television static; her emotional needs are presented as a gaping, hungry and above all unseemly hole, surrounded by well-described hair. He paints and paints them but the proportions are wrong. He is like a God who spends four hours on the shading on Eve’s upper lip, forgets to give her a clitoris, and then decides to rest on Tuesday. In the scene where Janice drunkenly drowns the baby, it wasn’t the character I felt pity for but Updike, fumbling so clumsily to get inside her that in the end it’s his hands that get slippery, drop the baby.”

Patricia Lockwood is a poet whose memoir, Priestdaddy , was named one of the 10 Best Books of 2017 by The New York Times . Her full review—in the London Review of Books Vol. 41 No. 19, 10 October 2019, the Anniversary Issue: Part One—isn’t just a hatchet job. It’s a thorough and thoughtful reconsideration of Updike then through the eyes of a woman now , and that’s fascinating. The #metoo movement has claimed a number of casualties, most of them deserved. But it has to leave today’s male writers wondering if any of them can ever be as completely honest as Updike was about sex and relations with women, or if that ship has sailed . . . and long ago sunk.

One thought on “ Is John Updike a ‘Malfunctioning Sex Robot’? ”

I think that the parts where she finds Updike the most bad, is probably where a subsequent generation will find him most adventurous. Atwood said Updike is someone who put a lot of time wondering how it would be to be a woman. She did not follow it by saying… yet somehow he got the whole damn thing wrong! Or not as I remember.

Defending him, really defending him in not a hey, this is my dad you’re talking about! way, is like defending post-war psychoanalysis. You’re doomed unless you equivocate to the moon. He’s a sitting duck, that’ll get the full defence he deserves sometime outside our time. In the meantime, don’t bother, and read the authors reviewers like this one like, the current ones, for there’s momentum there, and it’s lovely to participate where the best and brightest of today feel the truly serious lies. You’ll surprise yourself in finding it’s growth you didn’t know you needed, even if it’s not equivalent to spending time with what a subsequent generation would have given you, which is the current gen’s less rage, more emotionally quieted psyche/less requirement of re-directed revenge, but who also have less need of a creative culture built to enfranchise so little that amounts to few truly powerful shocks.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Find anything you save across the site in your account

“The House of God,” a Book as Sexist as It Was Influential, Gets a Sequel

By Rachel Pearson