Do Your Students Know How to Analyze a Case—Really?

Explore more.

- Case Teaching

- Student Engagement

J ust as actors, athletes, and musicians spend thousands of hours practicing their craft, business students benefit from practicing their critical-thinking and decision-making skills. Students, however, often have limited exposure to real-world problem-solving scenarios; they need more opportunities to practice tackling tough business problems and deciding on—and executing—the best solutions.

To ensure students have ample opportunity to develop these critical-thinking and decision-making skills, we believe business faculty should shift from teaching mostly principles and ideas to mostly applications and practices. And in doing so, they should emphasize the case method, which simulates real-world management challenges and opportunities for students.

To help educators facilitate this shift and help students get the most out of case-based learning, we have developed a framework for analyzing cases. We call it PACADI (Problem, Alternatives, Criteria, Analysis, Decision, Implementation); it can improve learning outcomes by helping students better solve and analyze business problems, make decisions, and develop and implement strategy. Here, we’ll explain why we developed this framework, how it works, and what makes it an effective learning tool.

The Case for Cases: Helping Students Think Critically

Business students must develop critical-thinking and analytical skills, which are essential to their ability to make good decisions in functional areas such as marketing, finance, operations, and information technology, as well as to understand the relationships among these functions. For example, the decisions a marketing manager must make include strategic planning (segments, products, and channels); execution (digital messaging, media, branding, budgets, and pricing); and operations (integrated communications and technologies), as well as how to implement decisions across functional areas.

Faculty can use many types of cases to help students develop these skills. These include the prototypical “paper cases”; live cases , which feature guest lecturers such as entrepreneurs or corporate leaders and on-site visits; and multimedia cases , which immerse students into real situations. Most cases feature an explicit or implicit decision that a protagonist—whether it is an individual, a group, or an organization—must make.

For students new to learning by the case method—and even for those with case experience—some common issues can emerge; these issues can sometimes be a barrier for educators looking to ensure the best possible outcomes in their case classrooms. Unsure of how to dig into case analysis on their own, students may turn to the internet or rely on former students for “answers” to assigned cases. Or, when assigned to provide answers to assignment questions in teams, students might take a divide-and-conquer approach but not take the time to regroup and provide answers that are consistent with one other.

To help address these issues, which we commonly experienced in our classes, we wanted to provide our students with a more structured approach for how they analyze cases—and to really think about making decisions from the protagonists’ point of view. We developed the PACADI framework to address this need.

PACADI: A Six-Step Decision-Making Approach

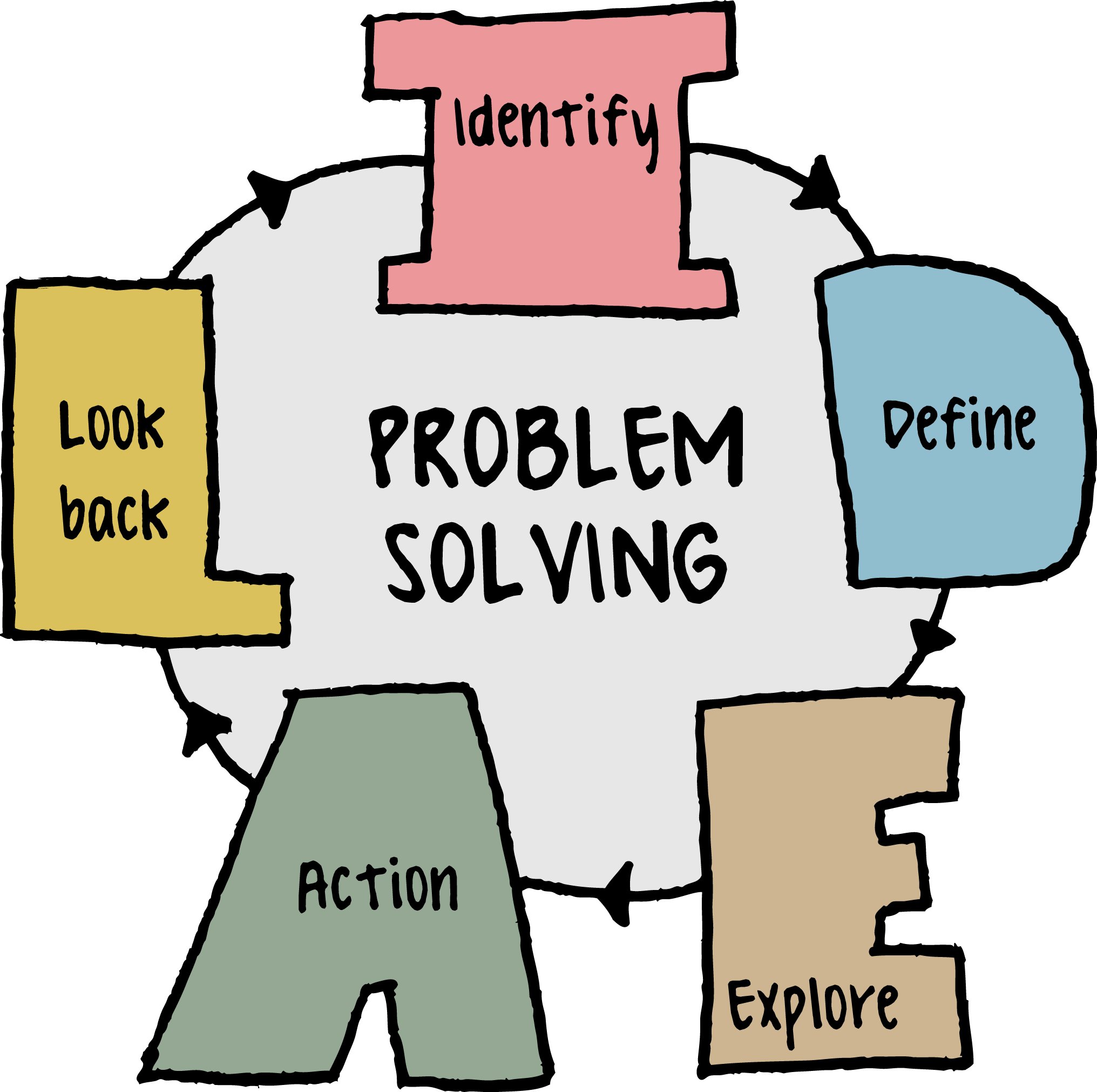

The PACADI framework is a six-step decision-making approach that can be used in lieu of traditional end-of-case questions. It offers a structured, integrated, and iterative process that requires students to analyze case information, apply business concepts to derive valuable insights, and develop recommendations based on these insights.

Prior to beginning a PACADI assessment, which we’ll outline here, students should first prepare a two-paragraph summary—a situation analysis—that highlights the key case facts. Then, we task students with providing a five-page PACADI case analysis (excluding appendices) based on the following six steps.

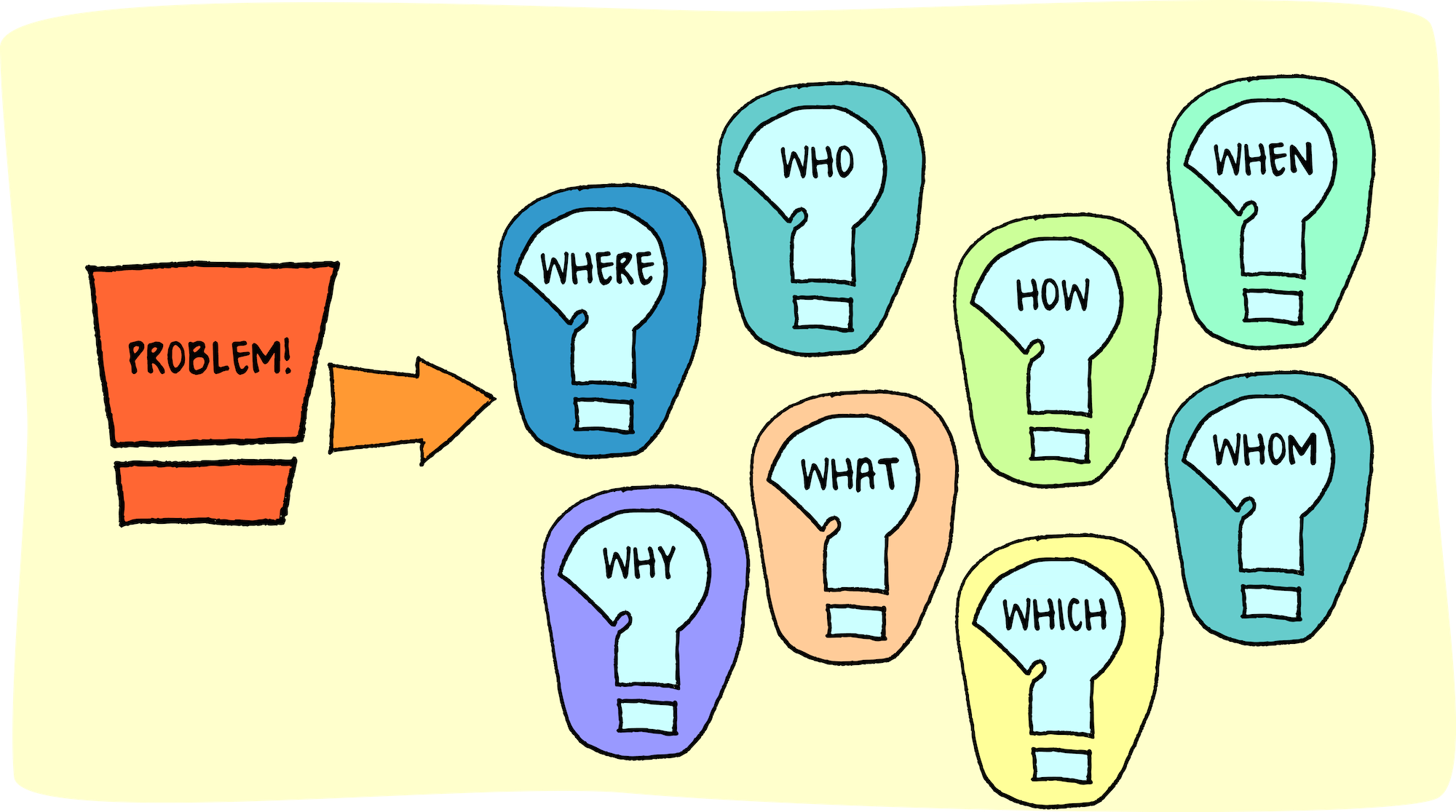

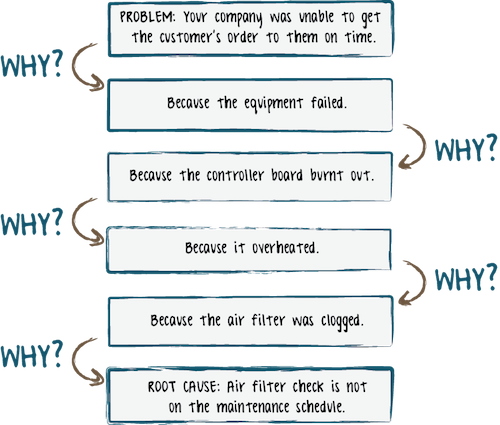

Step 1: Problem definition. What is the major challenge, problem, opportunity, or decision that has to be made? If there is more than one problem, choose the most important one. Often when solving the key problem, other issues will surface and be addressed. The problem statement may be framed as a question; for example, How can brand X improve market share among millennials in Canada? Usually the problem statement has to be re-written several times during the analysis of a case as students peel back the layers of symptoms or causation.

Step 2: Alternatives. Identify in detail the strategic alternatives to address the problem; three to five options generally work best. Alternatives should be mutually exclusive, realistic, creative, and feasible given the constraints of the situation. Doing nothing or delaying the decision to a later date are not considered acceptable alternatives.

Step 3: Criteria. What are the key decision criteria that will guide decision-making? In a marketing course, for example, these may include relevant marketing criteria such as segmentation, positioning, advertising and sales, distribution, and pricing. Financial criteria useful in evaluating the alternatives should be included—for example, income statement variables, customer lifetime value, payback, etc. Students must discuss their rationale for selecting the decision criteria and the weights and importance for each factor.

Step 4: Analysis. Provide an in-depth analysis of each alternative based on the criteria chosen in step three. Decision tables using criteria as columns and alternatives as rows can be helpful. The pros and cons of the various choices as well as the short- and long-term implications of each may be evaluated. Best, worst, and most likely scenarios can also be insightful.

Step 5: Decision. Students propose their solution to the problem. This decision is justified based on an in-depth analysis. Explain why the recommendation made is the best fit for the criteria.

Step 6: Implementation plan. Sound business decisions may fail due to poor execution. To enhance the likeliness of a successful project outcome, students describe the key steps (activities) to implement the recommendation, timetable, projected costs, expected competitive reaction, success metrics, and risks in the plan.

“Students note that using the PACADI framework yields ‘aha moments’—they learned something surprising in the case that led them to think differently about the problem and their proposed solution.”

PACADI’s Benefits: Meaningfully and Thoughtfully Applying Business Concepts

The PACADI framework covers all of the major elements of business decision-making, including implementation, which is often overlooked. By stepping through the whole framework, students apply relevant business concepts and solve management problems via a systematic, comprehensive approach; they’re far less likely to surface piecemeal responses.

As students explore each part of the framework, they may realize that they need to make changes to a previous step. For instance, when working on implementation, students may realize that the alternative they selected cannot be executed or will not be profitable, and thus need to rethink their decision. Or, they may discover that the criteria need to be revised since the list of decision factors they identified is incomplete (for example, the factors may explain key marketing concerns but fail to address relevant financial considerations) or is unrealistic (for example, they suggest a 25 percent increase in revenues without proposing an increased promotional budget).

In addition, the PACADI framework can be used alongside quantitative assignments, in-class exercises, and business and management simulations. The structured, multi-step decision framework encourages careful and sequential analysis to solve business problems. Incorporating PACADI as an overarching decision-making method across different projects will ultimately help students achieve desired learning outcomes. As a practical “beyond-the-classroom” tool, the PACADI framework is not a contrived course assignment; it reflects the decision-making approach that managers, executives, and entrepreneurs exercise daily. Case analysis introduces students to the real-world process of making business decisions quickly and correctly, often with limited information. This framework supplies an organized and disciplined process that students can readily defend in writing and in class discussions.

PACADI in Action: An Example

Here’s an example of how students used the PACADI framework for a recent case analysis on CVS, a large North American drugstore chain.

The CVS Prescription for Customer Value*

PACADI Stage

Summary Response

How should CVS Health evolve from the “drugstore of your neighborhood” to the “drugstore of your future”?

Alternatives

A1. Kaizen (continuous improvement)

A2. Product development

A3. Market development

A4. Personalization (micro-targeting)

Criteria (include weights)

C1. Customer value: service, quality, image, and price (40%)

C2. Customer obsession (20%)

C3. Growth through related businesses (20%)

C4. Customer retention and customer lifetime value (20%)

Each alternative was analyzed by each criterion using a Customer Value Assessment Tool

Alternative 4 (A4): Personalization was selected. This is operationalized via: segmentation—move toward segment-of-1 marketing; geodemographics and lifestyle emphasis; predictive data analysis; relationship marketing; people, principles, and supply chain management; and exceptional customer service.

Implementation

Partner with leading medical school

Curbside pick-up

Pet pharmacy

E-newsletter for customers and employees

Employee incentive program

CVS beauty days

Expand to Latin America and Caribbean

Healthier/happier corner

Holiday toy drives/community outreach

*Source: A. Weinstein, Y. Rodriguez, K. Sims, R. Vergara, “The CVS Prescription for Superior Customer Value—A Case Study,” Back to the Future: Revisiting the Foundations of Marketing from Society for Marketing Advances, West Palm Beach, FL (November 2, 2018).

Results of Using the PACADI Framework

When faculty members at our respective institutions at Nova Southeastern University (NSU) and the University of North Carolina Wilmington have used the PACADI framework, our classes have been more structured and engaging. Students vigorously debate each element of their decision and note that this framework yields an “aha moment”—they learned something surprising in the case that led them to think differently about the problem and their proposed solution.

These lively discussions enhance individual and collective learning. As one external metric of this improvement, we have observed a 2.5 percent increase in student case grade performance at NSU since this framework was introduced.

Tips to Get Started

The PACADI approach works well in in-person, online, and hybrid courses. This is particularly important as more universities have moved to remote learning options. Because students have varied educational and cultural backgrounds, work experience, and familiarity with case analysis, we recommend that faculty members have students work on their first case using this new framework in small teams (two or three students). Additional analyses should then be solo efforts.

To use PACADI effectively in your classroom, we suggest the following:

Advise your students that your course will stress critical thinking and decision-making skills, not just course concepts and theory.

Use a varied mix of case studies. As marketing professors, we often address consumer and business markets; goods, services, and digital commerce; domestic and global business; and small and large companies in a single MBA course.

As a starting point, provide a short explanation (about 20 to 30 minutes) of the PACADI framework with a focus on the conceptual elements. You can deliver this face to face or through videoconferencing.

Give students an opportunity to practice the case analysis methodology via an ungraded sample case study. Designate groups of five to seven students to discuss the case and the six steps in breakout sessions (in class or via Zoom).

Ensure case analyses are weighted heavily as a grading component. We suggest 30–50 percent of the overall course grade.

Once cases are graded, debrief with the class on what they did right and areas needing improvement (30- to 40-minute in-person or Zoom session).

Encourage faculty teams that teach common courses to build appropriate instructional materials, grading rubrics, videos, sample cases, and teaching notes.

When selecting case studies, we have found that the best ones for PACADI analyses are about 15 pages long and revolve around a focal management decision. This length provides adequate depth yet is not protracted. Some of our tested and favorite marketing cases include Brand W , Hubspot , Kraft Foods Canada , TRSB(A) , and Whiskey & Cheddar .

Art Weinstein , Ph.D., is a professor of marketing at Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He has published more than 80 scholarly articles and papers and eight books on customer-focused marketing strategy. His latest book is Superior Customer Value—Finding and Keeping Customers in the Now Economy . Dr. Weinstein has consulted for many leading technology and service companies.

Herbert V. Brotspies , D.B.A., is an adjunct professor of marketing at Nova Southeastern University. He has over 30 years’ experience as a vice president in marketing, strategic planning, and acquisitions for Fortune 50 consumer products companies working in the United States and internationally. His research interests include return on marketing investment, consumer behavior, business-to-business strategy, and strategic planning.

John T. Gironda , Ph.D., is an assistant professor of marketing at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. His research has been published in Industrial Marketing Management, Psychology & Marketing , and Journal of Marketing Management . He has also presented at major marketing conferences including the American Marketing Association, Academy of Marketing Science, and Society for Marketing Advances.

Related Articles

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 10 min read

Case Study-Based Learning

Enhancing learning through immediate application.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

If you've ever tried to learn a new concept, you probably appreciate that "knowing" is different from "doing." When you have an opportunity to apply your knowledge, the lesson typically becomes much more real.

Adults often learn differently from children, and we have different motivations for learning. Typically, we learn new skills because we want to. We recognize the need to learn and grow, and we usually need – or want – to apply our newfound knowledge soon after we've learned it.

A popular theory of adult learning is andragogy (the art and science of leading man, or adults), as opposed to the better-known pedagogy (the art and science of leading children). Malcolm Knowles , a professor of adult education, was considered the father of andragogy, which is based on four key observations of adult learners:

- Adults learn best if they know why they're learning something.

- Adults often learn best through experience.

- Adults tend to view learning as an opportunity to solve problems.

- Adults learn best when the topic is relevant to them and immediately applicable.

This means that you'll get the best results with adults when they're fully involved in the learning experience. Give an adult an opportunity to practice and work with a new skill, and you have a solid foundation for high-quality learning that the person will likely retain over time.

So, how can you best use these adult learning principles in your training and development efforts? Case studies provide an excellent way of practicing and applying new concepts. As such, they're very useful tools in adult learning, and it's important to understand how to get the maximum value from them.

What Is a Case Study?

Case studies are a form of problem-based learning, where you present a situation that needs a resolution. A typical business case study is a detailed account, or story, of what happened in a particular company, industry, or project over a set period of time.

The learner is given details about the situation, often in a historical context. The key players are introduced. Objectives and challenges are outlined. This is followed by specific examples and data, which the learner then uses to analyze the situation, determine what happened, and make recommendations.

The depth of a case depends on the lesson being taught. A case study can be two pages, 20 pages, or more. A good case study makes the reader think critically about the information presented, and then develop a thorough assessment of the situation, leading to a well-thought-out solution or recommendation.

Why Use a Case Study?

Case studies are a great way to improve a learning experience, because they get the learner involved, and encourage immediate use of newly acquired skills.

They differ from lectures or assigned readings because they require participation and deliberate application of a broad range of skills. For example, if you study financial analysis through straightforward learning methods, you may have to calculate and understand a long list of financial ratios (don't worry if you don't know what these are). Likewise, you may be given a set of financial statements to complete a ratio analysis. But until you put the exercise into context, you may not really know why you're doing the analysis.

With a case study, however, you might explore whether a bank should provide financing to a borrower, or whether a company is about to make a good acquisition. Suddenly, the act of calculating ratios becomes secondary – it's more important to understand what the ratios tell you. This is how case studies can make the difference between knowing what to do, and knowing how, when, and why to do it.

Then, what really separates case studies from other practical forms of learning – like scenarios and simulations – is the ability to compare the learner's recommendations with what actually happened. When you know what really happened, it's much easier to evaluate the "correctness" of the answers given.

When to Use a Case Study

As you can see, case studies are powerful and effective training tools. They also work best with practical, applied training, so make sure you use them appropriately.

Remember these tips:

- Case studies tend to focus on why and how to apply a skill or concept, not on remembering facts and details. Use case studies when understanding the concept is more important than memorizing correct responses.

- Case studies are great team-building opportunities. When a team gets together to solve a case, they'll have to work through different opinions, methods, and perspectives.

- Use case studies to build problem-solving skills, particularly those that are valuable when applied, but are likely to be used infrequently. This helps people get practice with these skills that they might not otherwise get.

- Case studies can be used to evaluate past problem solving. People can be asked what they'd do in that situation, and think about what could have been done differently.

Ensuring Maximum Value From Case Studies

The first thing to remember is that you already need to have enough theoretical knowledge to handle the questions and challenges in the case study. Otherwise, it can be like trying to solve a puzzle with some of the pieces missing.

Here are some additional tips for how to approach a case study. Depending on the exact nature of the case, some tips will be more relevant than others.

- Read the case at least three times before you start any analysis. Case studies usually have lots of details, and it's easy to miss something in your first, or even second, reading.

- Once you're thoroughly familiar with the case, note the facts. Identify which are relevant to the tasks you've been assigned. In a good case study, there are often many more facts than you need for your analysis.

- If the case contains large amounts of data, analyze this data for relevant trends. For example, have sales dropped steadily, or was there an unexpected high or low point?

- If the case involves a description of a company's history, find the key events, and consider how they may have impacted the current situation.

- Consider using techniques like SWOT analysis and Porter's Five Forces Analysis to understand the organization's strategic position.

- Stay with the facts when you draw conclusions. These include facts given in the case as well as established facts about the environmental context. Don't rely on personal opinions when you put together your answers.

Writing a Case Study

You may have to write a case study yourself. These are complex documents that take a while to research and compile. The quality of the case study influences the quality of the analysis. Here are some tips if you want to write your own:

- Write your case study as a structured story. The goal is to capture an interesting situation or challenge and then bring it to life with words and information. You want the reader to feel a part of what's happening.

- Present information so that a "right" answer isn't obvious. The goal is to develop the learner's ability to analyze and assess, not necessarily to make the same decision as the people in the actual case.

- Do background research to fully understand what happened and why. You may need to talk to key stakeholders to get their perspectives as well.

- Determine the key challenge. What needs to be resolved? The case study should focus on one main question or issue.

- Define the context. Talk about significant events leading up to the situation. What organizational factors are important for understanding the problem and assessing what should be done? Include cultural factors where possible.

- Identify key decision makers and stakeholders. Describe their roles and perspectives, as well as their motivations and interests.

- Make sure that you provide the right data to allow people to reach appropriate conclusions.

- Make sure that you have permission to use any information you include.

A typical case study structure includes these elements:

- Executive summary. Define the objective, and state the key challenge.

- Opening paragraph. Capture the reader's interest.

- Scope. Describe the background, context, approach, and issues involved.

- Presentation of facts. Develop an objective picture of what's happening.

- Description of key issues. Present viewpoints, decisions, and interests of key parties.

Because case studies have proved to be such effective teaching tools, many are already written. Some excellent sources of free cases are The Times 100 , CasePlace.org , and Schroeder & Schroeder Inc . You can often search for cases by topic or industry. These cases are expertly prepared, based mostly on real situations, and used extensively in business schools to teach management concepts.

Case studies are a great way to improve learning and training. They provide learners with an opportunity to solve a problem by applying what they know.

There are no unpleasant consequences for getting it "wrong," and cases give learners a much better understanding of what they really know and what they need to practice.

Case studies can be used in many ways, as team-building tools, and for skill development. You can write your own case study, but a large number are already prepared. Given the enormous benefits of practical learning applications like this, case studies are definitely something to consider adding to your next training session.

Knowles, M. (1973). 'The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species [online].' Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Open your eyes.

Exercise to Explore How People React When They Speak to Them or Try to Influence Them

Book Insights

Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity

David Allen

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Get 20% off your first year of Mind Tools

Our on-demand e-learning resources let you learn at your own pace, fitting seamlessly into your busy workday. Join today and save with our limited time offer!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

Pain Points Podcast - Balancing Work And Kids

Pain Points Podcast - Improving Culture

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Pain points podcast - what is ai.

Exploring Artificial Intelligence

Pain Points Podcast - How Do I Get Organized?

It's Time to Get Yourself Sorted!

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

The catalyst effect: 12 skills and behaviors to boost your impact and elevate team performance.

Jerry Toomer, Craig Caldwell, Steve Weitzenkorn and Chelsea Clark

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Problem-Solving in Business: CASE STUDIES

- ABOUT THIS LIBGUIDE

- PROBLEM-SOLVING DEFINED AND WHY IT IS IMPORTANT

- SKILLS AND QUALIFICATIONS NEEDED IN PROBLEM-SOLVING

- PROBLEM-SOLVING STEPS

- CASE STUDIES

- MORE HELPFUL RESOURCES

- << Previous: PROBLEM-SOLVING STEPS

- Next: MORE HELPFUL RESOURCES >>

- Last Updated: Mar 23, 2024 4:47 PM

- URL: https://libguides.nypl.org/problem_solving_in_business

How to master the seven-step problem-solving process

In this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , Simon London speaks with Charles Conn, CEO of venture-capital firm Oxford Sciences Innovation, and McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin about the complexities of different problem-solving strategies.

Podcast transcript

Simon London: Hello, and welcome to this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , with me, Simon London. What’s the number-one skill you need to succeed professionally? Salesmanship, perhaps? Or a facility with statistics? Or maybe the ability to communicate crisply and clearly? Many would argue that at the very top of the list comes problem solving: that is, the ability to think through and come up with an optimal course of action to address any complex challenge—in business, in public policy, or indeed in life.

Looked at this way, it’s no surprise that McKinsey takes problem solving very seriously, testing for it during the recruiting process and then honing it, in McKinsey consultants, through immersion in a structured seven-step method. To discuss the art of problem solving, I sat down in California with McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin and also with Charles Conn. Charles is a former McKinsey partner, entrepreneur, executive, and coauthor of the book Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything [John Wiley & Sons, 2018].

Charles and Hugo, welcome to the podcast. Thank you for being here.

Hugo Sarrazin: Our pleasure.

Charles Conn: It’s terrific to be here.

Simon London: Problem solving is a really interesting piece of terminology. It could mean so many different things. I have a son who’s a teenage climber. They talk about solving problems. Climbing is problem solving. Charles, when you talk about problem solving, what are you talking about?

Charles Conn: For me, problem solving is the answer to the question “What should I do?” It’s interesting when there’s uncertainty and complexity, and when it’s meaningful because there are consequences. Your son’s climbing is a perfect example. There are consequences, and it’s complicated, and there’s uncertainty—can he make that grab? I think we can apply that same frame almost at any level. You can think about questions like “What town would I like to live in?” or “Should I put solar panels on my roof?”

You might think that’s a funny thing to apply problem solving to, but in my mind it’s not fundamentally different from business problem solving, which answers the question “What should my strategy be?” Or problem solving at the policy level: “How do we combat climate change?” “Should I support the local school bond?” I think these are all part and parcel of the same type of question, “What should I do?”

I’m a big fan of structured problem solving. By following steps, we can more clearly understand what problem it is we’re solving, what are the components of the problem that we’re solving, which components are the most important ones for us to pay attention to, which analytic techniques we should apply to those, and how we can synthesize what we’ve learned back into a compelling story. That’s all it is, at its heart.

I think sometimes when people think about seven steps, they assume that there’s a rigidity to this. That’s not it at all. It’s actually to give you the scope for creativity, which often doesn’t exist when your problem solving is muddled.

Simon London: You were just talking about the seven-step process. That’s what’s written down in the book, but it’s a very McKinsey process as well. Without getting too deep into the weeds, let’s go through the steps, one by one. You were just talking about problem definition as being a particularly important thing to get right first. That’s the first step. Hugo, tell us about that.

Hugo Sarrazin: It is surprising how often people jump past this step and make a bunch of assumptions. The most powerful thing is to step back and ask the basic questions—“What are we trying to solve? What are the constraints that exist? What are the dependencies?” Let’s make those explicit and really push the thinking and defining. At McKinsey, we spend an enormous amount of time in writing that little statement, and the statement, if you’re a logic purist, is great. You debate. “Is it an ‘or’? Is it an ‘and’? What’s the action verb?” Because all these specific words help you get to the heart of what matters.

Want to subscribe to The McKinsey Podcast ?

Simon London: So this is a concise problem statement.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah. It’s not like “Can we grow in Japan?” That’s interesting, but it is “What, specifically, are we trying to uncover in the growth of a product in Japan? Or a segment in Japan? Or a channel in Japan?” When you spend an enormous amount of time, in the first meeting of the different stakeholders, debating this and having different people put forward what they think the problem definition is, you realize that people have completely different views of why they’re here. That, to me, is the most important step.

Charles Conn: I would agree with that. For me, the problem context is critical. When we understand “What are the forces acting upon your decision maker? How quickly is the answer needed? With what precision is the answer needed? Are there areas that are off limits or areas where we would particularly like to find our solution? Is the decision maker open to exploring other areas?” then you not only become more efficient, and move toward what we call the critical path in problem solving, but you also make it so much more likely that you’re not going to waste your time or your decision maker’s time.

How often do especially bright young people run off with half of the idea about what the problem is and start collecting data and start building models—only to discover that they’ve really gone off half-cocked.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah.

Charles Conn: And in the wrong direction.

Simon London: OK. So step one—and there is a real art and a structure to it—is define the problem. Step two, Charles?

Charles Conn: My favorite step is step two, which is to use logic trees to disaggregate the problem. Every problem we’re solving has some complexity and some uncertainty in it. The only way that we can really get our team working on the problem is to take the problem apart into logical pieces.

What we find, of course, is that the way to disaggregate the problem often gives you an insight into the answer to the problem quite quickly. I love to do two or three different cuts at it, each one giving a bit of a different insight into what might be going wrong. By doing sensible disaggregations, using logic trees, we can figure out which parts of the problem we should be looking at, and we can assign those different parts to team members.

Simon London: What’s a good example of a logic tree on a sort of ratable problem?

Charles Conn: Maybe the easiest one is the classic profit tree. Almost in every business that I would take a look at, I would start with a profit or return-on-assets tree. In its simplest form, you have the components of revenue, which are price and quantity, and the components of cost, which are cost and quantity. Each of those can be broken out. Cost can be broken into variable cost and fixed cost. The components of price can be broken into what your pricing scheme is. That simple tree often provides insight into what’s going on in a business or what the difference is between that business and the competitors.

If we add the leg, which is “What’s the asset base or investment element?”—so profit divided by assets—then we can ask the question “Is the business using its investments sensibly?” whether that’s in stores or in manufacturing or in transportation assets. I hope we can see just how simple this is, even though we’re describing it in words.

When I went to work with Gordon Moore at the Moore Foundation, the problem that he asked us to look at was “How can we save Pacific salmon?” Now, that sounds like an impossible question, but it was amenable to precisely the same type of disaggregation and allowed us to organize what became a 15-year effort to improve the likelihood of good outcomes for Pacific salmon.

Simon London: Now, is there a danger that your logic tree can be impossibly large? This, I think, brings us onto the third step in the process, which is that you have to prioritize.

Charles Conn: Absolutely. The third step, which we also emphasize, along with good problem definition, is rigorous prioritization—we ask the questions “How important is this lever or this branch of the tree in the overall outcome that we seek to achieve? How much can I move that lever?” Obviously, we try and focus our efforts on ones that have a big impact on the problem and the ones that we have the ability to change. With salmon, ocean conditions turned out to be a big lever, but not one that we could adjust. We focused our attention on fish habitats and fish-harvesting practices, which were big levers that we could affect.

People spend a lot of time arguing about branches that are either not important or that none of us can change. We see it in the public square. When we deal with questions at the policy level—“Should you support the death penalty?” “How do we affect climate change?” “How can we uncover the causes and address homelessness?”—it’s even more important that we’re focusing on levers that are big and movable.

Would you like to learn more about our Strategy & Corporate Finance Practice ?

Simon London: Let’s move swiftly on to step four. You’ve defined your problem, you disaggregate it, you prioritize where you want to analyze—what you want to really look at hard. Then you got to the work plan. Now, what does that mean in practice?

Hugo Sarrazin: Depending on what you’ve prioritized, there are many things you could do. It could be breaking the work among the team members so that people have a clear piece of the work to do. It could be defining the specific analyses that need to get done and executed, and being clear on time lines. There’s always a level-one answer, there’s a level-two answer, there’s a level-three answer. Without being too flippant, I can solve any problem during a good dinner with wine. It won’t have a whole lot of backing.

Simon London: Not going to have a lot of depth to it.

Hugo Sarrazin: No, but it may be useful as a starting point. If the stakes are not that high, that could be OK. If it’s really high stakes, you may need level three and have the whole model validated in three different ways. You need to find a work plan that reflects the level of precision, the time frame you have, and the stakeholders you need to bring along in the exercise.

Charles Conn: I love the way you’ve described that, because, again, some people think of problem solving as a linear thing, but of course what’s critical is that it’s iterative. As you say, you can solve the problem in one day or even one hour.

Charles Conn: We encourage our teams everywhere to do that. We call it the one-day answer or the one-hour answer. In work planning, we’re always iterating. Every time you see a 50-page work plan that stretches out to three months, you know it’s wrong. It will be outmoded very quickly by that learning process that you described. Iterative problem solving is a critical part of this. Sometimes, people think work planning sounds dull, but it isn’t. It’s how we know what’s expected of us and when we need to deliver it and how we’re progressing toward the answer. It’s also the place where we can deal with biases. Bias is a feature of every human decision-making process. If we design our team interactions intelligently, we can avoid the worst sort of biases.

Simon London: Here we’re talking about cognitive biases primarily, right? It’s not that I’m biased against you because of your accent or something. These are the cognitive biases that behavioral sciences have shown we all carry around, things like anchoring, overoptimism—these kinds of things.

Both: Yeah.

Charles Conn: Availability bias is the one that I’m always alert to. You think you’ve seen the problem before, and therefore what’s available is your previous conception of it—and we have to be most careful about that. In any human setting, we also have to be careful about biases that are based on hierarchies, sometimes called sunflower bias. I’m sure, Hugo, with your teams, you make sure that the youngest team members speak first. Not the oldest team members, because it’s easy for people to look at who’s senior and alter their own creative approaches.

Hugo Sarrazin: It’s helpful, at that moment—if someone is asserting a point of view—to ask the question “This was true in what context?” You’re trying to apply something that worked in one context to a different one. That can be deadly if the context has changed, and that’s why organizations struggle to change. You promote all these people because they did something that worked well in the past, and then there’s a disruption in the industry, and they keep doing what got them promoted even though the context has changed.

Simon London: Right. Right.

Hugo Sarrazin: So it’s the same thing in problem solving.

Charles Conn: And it’s why diversity in our teams is so important. It’s one of the best things about the world that we’re in now. We’re likely to have people from different socioeconomic, ethnic, and national backgrounds, each of whom sees problems from a slightly different perspective. It is therefore much more likely that the team will uncover a truly creative and clever approach to problem solving.

Simon London: Let’s move on to step five. You’ve done your work plan. Now you’ve actually got to do the analysis. The thing that strikes me here is that the range of tools that we have at our disposal now, of course, is just huge, particularly with advances in computation, advanced analytics. There’s so many things that you can apply here. Just talk about the analysis stage. How do you pick the right tools?

Charles Conn: For me, the most important thing is that we start with simple heuristics and explanatory statistics before we go off and use the big-gun tools. We need to understand the shape and scope of our problem before we start applying these massive and complex analytical approaches.

Simon London: Would you agree with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: I agree. I think there are so many wonderful heuristics. You need to start there before you go deep into the modeling exercise. There’s an interesting dynamic that’s happening, though. In some cases, for some types of problems, it is even better to set yourself up to maximize your learning. Your problem-solving methodology is test and learn, test and learn, test and learn, and iterate. That is a heuristic in itself, the A/B testing that is used in many parts of the world. So that’s a problem-solving methodology. It’s nothing different. It just uses technology and feedback loops in a fast way. The other one is exploratory data analysis. When you’re dealing with a large-scale problem, and there’s so much data, I can get to the heuristics that Charles was talking about through very clever visualization of data.

You test with your data. You need to set up an environment to do so, but don’t get caught up in neural-network modeling immediately. You’re testing, you’re checking—“Is the data right? Is it sound? Does it make sense?”—before you launch too far.

Simon London: You do hear these ideas—that if you have a big enough data set and enough algorithms, they’re going to find things that you just wouldn’t have spotted, find solutions that maybe you wouldn’t have thought of. Does machine learning sort of revolutionize the problem-solving process? Or are these actually just other tools in the toolbox for structured problem solving?

Charles Conn: It can be revolutionary. There are some areas in which the pattern recognition of large data sets and good algorithms can help us see things that we otherwise couldn’t see. But I do think it’s terribly important we don’t think that this particular technique is a substitute for superb problem solving, starting with good problem definition. Many people use machine learning without understanding algorithms that themselves can have biases built into them. Just as 20 years ago, when we were doing statistical analysis, we knew that we needed good model definition, we still need a good understanding of our algorithms and really good problem definition before we launch off into big data sets and unknown algorithms.

Simon London: Step six. You’ve done your analysis.

Charles Conn: I take six and seven together, and this is the place where young problem solvers often make a mistake. They’ve got their analysis, and they assume that’s the answer, and of course it isn’t the answer. The ability to synthesize the pieces that came out of the analysis and begin to weave those into a story that helps people answer the question “What should I do?” This is back to where we started. If we can’t synthesize, and we can’t tell a story, then our decision maker can’t find the answer to “What should I do?”

Simon London: But, again, these final steps are about motivating people to action, right?

Charles Conn: Yeah.

Simon London: I am slightly torn about the nomenclature of problem solving because it’s on paper, right? Until you motivate people to action, you actually haven’t solved anything.

Charles Conn: I love this question because I think decision-making theory, without a bias to action, is a waste of time. Everything in how I approach this is to help people take action that makes the world better.

Simon London: Hence, these are absolutely critical steps. If you don’t do this well, you’ve just got a bunch of analysis.

Charles Conn: We end up in exactly the same place where we started, which is people speaking across each other, past each other in the public square, rather than actually working together, shoulder to shoulder, to crack these important problems.

Simon London: In the real world, we have a lot of uncertainty—arguably, increasing uncertainty. How do good problem solvers deal with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: At every step of the process. In the problem definition, when you’re defining the context, you need to understand those sources of uncertainty and whether they’re important or not important. It becomes important in the definition of the tree.

You need to think carefully about the branches of the tree that are more certain and less certain as you define them. They don’t have equal weight just because they’ve got equal space on the page. Then, when you’re prioritizing, your prioritization approach may put more emphasis on things that have low probability but huge impact—or, vice versa, may put a lot of priority on things that are very likely and, hopefully, have a reasonable impact. You can introduce that along the way. When you come back to the synthesis, you just need to be nuanced about what you’re understanding, the likelihood.

Often, people lack humility in the way they make their recommendations: “This is the answer.” They’re very precise, and I think we would all be well-served to say, “This is a likely answer under the following sets of conditions” and then make the level of uncertainty clearer, if that is appropriate. It doesn’t mean you’re always in the gray zone; it doesn’t mean you don’t have a point of view. It just means that you can be explicit about the certainty of your answer when you make that recommendation.

Simon London: So it sounds like there is an underlying principle: “Acknowledge and embrace the uncertainty. Don’t pretend that it isn’t there. Be very clear about what the uncertainties are up front, and then build that into every step of the process.”

Hugo Sarrazin: Every step of the process.

Simon London: Yeah. We have just walked through a particular structured methodology for problem solving. But, of course, this is not the only structured methodology for problem solving. One that is also very well-known is design thinking, which comes at things very differently. So, Hugo, I know you have worked with a lot of designers. Just give us a very quick summary. Design thinking—what is it, and how does it relate?

Hugo Sarrazin: It starts with an incredible amount of empathy for the user and uses that to define the problem. It does pause and go out in the wild and spend an enormous amount of time seeing how people interact with objects, seeing the experience they’re getting, seeing the pain points or joy—and uses that to infer and define the problem.

Simon London: Problem definition, but out in the world.

Hugo Sarrazin: With an enormous amount of empathy. There’s a huge emphasis on empathy. Traditional, more classic problem solving is you define the problem based on an understanding of the situation. This one almost presupposes that we don’t know the problem until we go see it. The second thing is you need to come up with multiple scenarios or answers or ideas or concepts, and there’s a lot of divergent thinking initially. That’s slightly different, versus the prioritization, but not for long. Eventually, you need to kind of say, “OK, I’m going to converge again.” Then you go and you bring things back to the customer and get feedback and iterate. Then you rinse and repeat, rinse and repeat. There’s a lot of tactile building, along the way, of prototypes and things like that. It’s very iterative.

Simon London: So, Charles, are these complements or are these alternatives?

Charles Conn: I think they’re entirely complementary, and I think Hugo’s description is perfect. When we do problem definition well in classic problem solving, we are demonstrating the kind of empathy, at the very beginning of our problem, that design thinking asks us to approach. When we ideate—and that’s very similar to the disaggregation, prioritization, and work-planning steps—we do precisely the same thing, and often we use contrasting teams, so that we do have divergent thinking. The best teams allow divergent thinking to bump them off whatever their initial biases in problem solving are. For me, design thinking gives us a constant reminder of creativity, empathy, and the tactile nature of problem solving, but it’s absolutely complementary, not alternative.

Simon London: I think, in a world of cross-functional teams, an interesting question is do people with design-thinking backgrounds really work well together with classical problem solvers? How do you make that chemistry happen?

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah, it is not easy when people have spent an enormous amount of time seeped in design thinking or user-centric design, whichever word you want to use. If the person who’s applying classic problem-solving methodology is very rigid and mechanical in the way they’re doing it, there could be an enormous amount of tension. If there’s not clarity in the role and not clarity in the process, I think having the two together can be, sometimes, problematic.

The second thing that happens often is that the artifacts the two methodologies try to gravitate toward can be different. Classic problem solving often gravitates toward a model; design thinking migrates toward a prototype. Rather than writing a big deck with all my supporting evidence, they’ll bring an example, a thing, and that feels different. Then you spend your time differently to achieve those two end products, so that’s another source of friction.

Now, I still think it can be an incredibly powerful thing to have the two—if there are the right people with the right mind-set, if there is a team that is explicit about the roles, if we’re clear about the kind of outcomes we are attempting to bring forward. There’s an enormous amount of collaborativeness and respect.

Simon London: But they have to respect each other’s methodology and be prepared to flex, maybe, a little bit, in how this process is going to work.

Hugo Sarrazin: Absolutely.

Simon London: The other area where, it strikes me, there could be a little bit of a different sort of friction is this whole concept of the day-one answer, which is what we were just talking about in classical problem solving. Now, you know that this is probably not going to be your final answer, but that’s how you begin to structure the problem. Whereas I would imagine your design thinkers—no, they’re going off to do their ethnographic research and get out into the field, potentially for a long time, before they come back with at least an initial hypothesis.

Want better strategies? Become a bulletproof problem solver

Hugo Sarrazin: That is a great callout, and that’s another difference. Designers typically will like to soak into the situation and avoid converging too quickly. There’s optionality and exploring different options. There’s a strong belief that keeps the solution space wide enough that you can come up with more radical ideas. If there’s a large design team or many designers on the team, and you come on Friday and say, “What’s our week-one answer?” they’re going to struggle. They’re not going to be comfortable, naturally, to give that answer. It doesn’t mean they don’t have an answer; it’s just not where they are in their thinking process.

Simon London: I think we are, sadly, out of time for today. But Charles and Hugo, thank you so much.

Charles Conn: It was a pleasure to be here, Simon.

Hugo Sarrazin: It was a pleasure. Thank you.

Simon London: And thanks, as always, to you, our listeners, for tuning into this episode of the McKinsey Podcast . If you want to learn more about problem solving, you can find the book, Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything , online or order it through your local bookstore. To learn more about McKinsey, you can of course find us at McKinsey.com.

Charles Conn is CEO of Oxford Sciences Innovation and an alumnus of McKinsey’s Sydney office. Hugo Sarrazin is a senior partner in the Silicon Valley office, where Simon London, a member of McKinsey Publishing, is also based.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Strategy to beat the odds

Five routes to more innovative problem solving

- --> Login or Sign Up

- Problem Solving Workshop

How to Approach a Case Study in a Problem Solving Workshop

John Palfrey and Lisa Brem

Share This Article

- Custom Field #1

- Custom Field #2

- Similar Products

Product Description

This note, designed for students in the Problem Solving Workshop, gives helpful tips for approaching problem solving case studies. Learning Objectives

- Help students effectively read problem solving case studies and prepare for problem solving class discussions and exercises.

Subjects Covered Problem Solving, Case Studies

Accessibility

To obtain accessible versions of our products for use by those with disabilities, please contact the HLS Case Studies Program at [email protected] or +1-617-496-1316.

Educator Materials

Registered members of this website can download this product at no cost. Please create an account or sign in to gain access to these materials.

Note: It can take up to three business days after you create an account to verify educator access. Verification will be confirmed via email.

For more information about the Problem Solving Workshop, or to request a teaching note for this case study, contact the Case Studies Program at [email protected] or +1-617-496-1316.

Additional Infor mation

The Problem Solving Workshop: A Video Introduction

Copyright Information

Please note that each purchase of this product entitles the purchaser to one download and use. If you need multiple copies, please purchase the number of copies you need. For more information, see Copying Your Case Study .

Product Videos

Custom field, product reviews, write a review.

Find Similar Products by Category

Recommended.

Creating Collaborative Documents

David Abrams

How to Be a Good Team Member

Joseph William Singer

Problem Solving for Lawyers

Writing and Presenting Short Memoranda to Supervisors

David B. Wilkins

- Related Products

- Harvard Case Study Solution

- Case Study Report Writing Service

- Case Study Presentation Help

- Finance Case Study Help

- Accounting Case Study Help

- Marketing Case Study Help

- Nursing Case Study Help

- Management Case Study Help

- Economics Case Study Help

- MBA Case Study Help

- Assignment Help

- Accounting Assignment Help

- Finance Assignment Help

- Marketing Assignment Help

- HR Assignment Help

- Economics Assignment Help

- Law Assignment Help

- Project Management Assignment Help

- Nursing Assignment Help

- Biology Assignment Help

- Chemistry Assignment Help

- English Assignment Help

- Homework Help

- Thesis Help

- Dissertation Help

- How it Works

How To Solve A Case Study

Introduction

What is a case study? A case study is a deep study or a detailed examination of a particular case. In politics case studies, it can range from little happenings to huge undertakings like world wars. It is not necessary that a case study only highlights only an individual’s case but it can also highlight groups, belief systems, organizations, or events. Necessarily the case study does did not include only one observation but it may include many observations. In the case of studies projects for research involving several cases are called cross-case research; on the other hand, the study of a single case is called within the case research.

How to solve a case study?

Solving a case study requires deep analyzing skills, the ability to investigate the current problem, examine the right solution, and using the most supportive and workable evidence. It is necessary to take notes, highlight influential facts, and underline the major problems involved. Into days modern times; you can also online case study solutions help by contacting experts on their websites. To make it easier we follow a step-wise procedure to make it understandable. So before you begin Writing the case, follow the step-by-step procedure to get reasonable and desired results.

Step#1: Identify The Case

The first step is about taking notes, highlight the key factors which are being involved, and also introduce the relevant factors which are necessary.

Step#2: Focus Your Analysis

Identify the key problems. Find the reason that why Do they exist? How can they affect the organization or client? Which thing is responsible, and go for their best possible solutions.

Step#3: Realize Possible Solutions

Review all the reading related to the case study course, related discussions, consult it with outside sources, and utilize your experience.

Step#4: Choose The Best Possible Solution

Consider the best and supporting evidence. Its pros and cons, and how realistic it is?. Scan the gathered information again and do not overlook it without focusing on each point.

This is how to solve a case study step by step and easily conclude it while benefiting your clients following these well-researched steps. Additionally following these steps one can also be familiar that how to write case study assignment while getting less confusion.

Examples OF Solving A Case Study

As we know case study involves examining things deeply; for example, we take a case study in medicines. It may be related to an ailment or a patient; a case study in the business sector might cover a broader market; in politics, a case study might range from a narrow happening to a huge undertaking. Let’s discuss How to solve case studies with examples,

Example#1: AnaOwas a woman’s pseudonym of a lady named Bertha. A patient of a famous physical expert Jose Breuer. She was never a patient of another physician Freud. Both physicians Breuer and Joseph, extensively discuss her case. The woman was expecting the symptoms of a disease known as hysteria and it is also found that talking about her issues relieving her a lot and her symptoms. Her case becomes beneficial to understand the fact that therapy of talking has an excellent approach towards mental health.

Example#2: Phineas Gage was an employee in railways. Phineas experiences a scary accident in which a metal rod stuck his skull, damaging a sensitive portion of his brain; although he recovered after that, he comes up with extreme changes in his behavior and personality.

Example#3: Genie a young beautiful girl faced horrifying abuse and isolation. Genie’s case study allows many researchers to examine whether languages could be learned even after hectic times for developing language had vanished for her. Her case also enables everyone to understand that how interference of scientific researches leads to more abuse of a vulnerable person. One can also consult their mentors to understand which case study to buy and get the valuable guidance.

Benefits and Limitations OF A Case Study

A case study could have both strengths and drawbacks. Here we discuss its good and bad things in the form of bullets. First of all, we get to know about its pros.

- It allows investigators and researchers to attain high-level knowledge.

- Give them a chance to attain valuable information from Unusual and rare cases.

- Allow the individuals for research to develop their hypotheses to explore them at experimental research.

Along with its pros, case studies have their cons too. Let’s discuss them in bullets.

- The case study cannot briefly demonstrate cause and influences.

- It cannot be generalized in public.

- It can also lead to bias.

Bottom Lines

Generally, case studies can be included in many different fields like education, anthropology, psychology, medicines, and political sciences. We have discussed in the article above about case study definition, how to solve it, and also include the examples for your better understanding. Hoping that this article will play its part in building your knowledge about studying a case.

Suggested Articles

How To Answer A Case Study

A Step To Step Guide On The Importance OF Case Study

How To Buy A Case Study Assignment Help

How To Write Case Study In MBA

How To Write A Case Study For Assignment

- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

10 Successful Design Thinking Case Study

Dive into the realm of Successful Design Thinking Case Studies to explore the power of this innovative problem-solving approach. Begin by understanding What is Design Thinking? and then embark on a journey through real-world success stories. Discover valuable lessons learned from these case studies and gain insights into how Design Thinking can transform your approach.

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Introduction to Management

- Management Training for New Managers

- Problem Solving Course

- Leadership Skills Training

- Design Thinking for R&D Engineers Training

Design Thinking has emerged as a powerful problem-solving approach that places empathy, creativity, and innovation at the forefront. However, if you are not aware of the power that this approach holds, a Design Thinking Case Study is often used to help people address the complex challenges of this approach with a human-centred perspective. It allows organisations to unlock new opportunities and drive meaningful change. Read this blog on Design Thinking Case Study to learn how it enhances organisation’s growth and gain valuable insights on creative problem-solving.

Table of Contents

1) What is Design Thinking?

2) Design Thinking process

3) Successful Design Thinking Case Studies

a) Airbnb

b) Apple

c) Netflix

d) UberEats

e) IBM

f) OralB’s electric toothbrush

g) IDEO

h) Tesla

i) GE Healthcare

j) Nike

3) Lessons learned from Design Thinking Case Studies

4) Conclusion

What is Design Thinking ?

Before jumping on Design Thinking Case Study, let’s first understand what it is. Design Thinking is a methodology for problem-solving that prioritises the understanding and addressing of individuals' unique needs.

This human-centric approach is creative and iterative, aiming to find innovative solutions to complex challenges. At its core, Design Thinking fosters empathy, encourages collaboration, and embraces experimentation.

This process revolves around comprehending the world from the user's perspective, identifying problems through this lens, and then generating and refining solutions that cater to these specific needs. Design Thinking places great importance on creativity and out-of-the-box thinking, seeking to break away from conventional problem-solving methods.

It is not confined to the realm of design but can be applied to various domains, from business and technology to healthcare and education. By putting the user or customer at the centre of the problem-solving journey, Design Thinking helps create products, services, and experiences that are more effective, user-friendly, and aligned with the genuine needs of the people they serve.

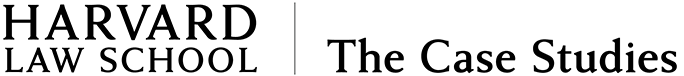

Design Thinking process

Design Thinking is a problem-solving and innovation framework that helps individuals and teams create user-centred solutions. This process consists of five key phases that are as follows:

To initiate the Design Thinking process, the first step is to practice empathy. In order to create products and services that are appealing, it is essential to comprehend the users and their requirements. What are their anticipations regarding the product you are designing? What issues and difficulties are they encountering within this particular context?

During the empathise phase, you spend time observing and engaging with real users. This might involve conducting interviews and seeing how they interact with an existing product. You should pay attention to facial expressions and body language. During the empathise phase in the Design Thinking Process , it's crucial to set aside assumptions and gain first-hand insights to design with real users in mind. That's the essence of Design Thinking.

During the second stage of the Design Thinking process, the goal is to identify the user’s problem. To accomplish this, collect all your observations from the empathise phase and begin to connect the dots.

Ask yourself: What consistent patterns or themes did you notice? What recurring user needs or challenges were identified? After synthesising your findings, you must create a problem statement, also known as a Point Of View (POV) statement, which outlines the issue or challenge you aim to address. By the end of the define stage, you will be able to craft a clear problem statement that will guide you throughout the design process, forming the basis of your ideas and potential solutions.

After completing the first two stages of the Design Thinking process, which involve defining the target users and identifying the problem statement, it is now time to move on to the third stage - ideation. This stage is all about brainstorming and coming up with various ideas and solutions to solve the problem statement. Through ideation, the team can explore different perspectives and possibilities and select the best ideas to move forward with.

During the ideation phase, it is important to create an environment where everyone feels comfortable sharing their ideas without fear of judgment. This phase is all about generating a large quantity of ideas, regardless of feasibility. This is done by encouraging the team to think outside the box and explore new angles. To maximise creativity, ideation sessions are often held in unconventional locations.

It’s time to transform the ideas from stage three into physical or digital prototypes. A prototype is a miniature model of a product or feature, which can be as simple as a paper model or as complex as an interactive digital representation.

During the Prototyping Stage , the primary objective is to transform your ideas into a tangible product that can be tested by actual users. This is crucial in maintaining a user-centric approach, as it enables you to obtain feedback before proceeding to develop the entire product. By doing so, you can ensure that the final design adequately addresses the user's problem and delivers an enjoyable user experience.

During the Design Thinking process, the fifth step involves testing your prototypes by exposing them to real users and evaluating their performance. Throughout this testing phase, you can observe how your target or prospective users engage with your prototype. Additionally, you can gather valuable feedback from your users about their experiences throughout the process.

Based on the feedback received during user testing, you can go back and make improvements to the design. It is important to remember that the Design Thinking process is iterative and non-linear. After the testing phase, it may be necessary to revisit the empathise stage or conduct additional ideation sessions before creating a successful prototype.

Unlock the power of Design Thinking – Sign up for our comprehensive Design Thinking for R&D Engineers Training Today!

Successful Design Thinking Case Studies

Now that you have a foundational understanding of Design Thinking, let's explore how some of the world's most successful companies have leveraged this methodology to drive innovation and success:

Case Study 1: Airbnb

Airbnb’s one of the popular Design Thinking Case Studies that you can aspire from. Airbnb disrupted the traditional hotel industry by applying Design Thinking principles to create a platform that connects travellers with unique accommodations worldwide. The founders of Airbnb, Brian Chesky, Joe Gebbia, and Nathan Blecharczyk, started by identifying a problem: the cost and lack of personalisation in traditional lodging.

They conducted in-depth user research by staying in their own listings and collecting feedback from both hosts and guests. This empathetic approach allowed them to design a platform that not only met the needs of travellers but also empowered hosts to provide personalised experiences.

Airbnb's intuitive website and mobile app interface, along with its robust review and rating system, instil trust and transparency, making users feel comfortable choosing from a vast array of properties. Furthermore, the "Experiences" feature reflects Airbnb's commitment to immersive travel, allowing users to book unique activities hosted by locals.

Case Study 2. Apple

Apple Inc. has consistently been a pioneer in Design Thinking, which is evident in its products, such as the iPhone. One of the best Design Thinking Examples from Apple is the development of the iPhone's User Interface (UI). The team at Apple identified the need for a more intuitive and user-friendly smartphone experience. They conducted extensive research and usability testing to understand user behaviours, pain points, and desires.

The result? A revolutionary touch interface that forever changed the smartphone industry. Apple's relentless focus on the user experience, combined with iterative prototyping and user feedback, exemplifies the power of Design Thinking in creating groundbreaking products.

Apple invests heavily in user research to anticipate what customers want before they even realise it themselves. This empathetic approach to design has led to groundbreaking innovations like the iPhone, iPad, and MacBook, which have redefined the entire industry.

Case Study 3. Netflix

Netflix, the global streaming giant, has revolutionised the way people consume entertainment content. A major part of their success can be attributed to their effective use of Design Thinking principles.

What sets Netflix apart is its commitment to understanding its audience on a profound level. Netflix recognised that its success hinged on offering a personalised, enjoyable viewing experience. Through meticulous user research, data analysis, and a culture of innovation, Netflix constantly evolves its platform. Moreover, by gathering insights on viewing habits, content preferences, and even UI, the company tailors its recommendations, search algorithms, and original content to captivate viewers worldwide.

Furthermore, Netflix's iterative approach to Design Thinking allows it to adapt quickly to shifting market dynamics. This agility proved crucial when transitioning from a DVD rental service to a streaming platform. Netflix didn't just lead this revolution; it shaped it by keeping users' desires and behaviours front and centre. Netflix's commitment to Design Thinking has resulted in a highly user-centric platform that keeps subscribers engaged and satisfied, ultimately contributing to its global success.

Case Study 4. Uber Eats

Uber Eats, a subsidiary of Uber, has disrupted the food delivery industry by applying Design Thinking principles to enhance user experiences and create a seamless platform for food lovers and restaurants alike.

One of UberEats' key innovations lies in its user-centric approach. By conducting in-depth research and understanding the pain points of both consumers and restaurant partners, they crafted a solution that addresses real-world challenges. The user-friendly app offers a wide variety of cuisines, personalised recommendations, and real-time tracking, catering to the diverse preferences of customers.

Moreover, UberEats leverages technology and data-driven insights to optimise delivery routes and times, ensuring that hot and fresh food reaches customers promptly. The platform also empowers restaurant owners with tools to efficiently manage orders, track performance, and expand their customer base.

Case Study 5 . IBM

IBM is a prime example of a large corporation successfully adopting Design Thinking to drive innovation and transform its business. Historically known for its hardware and software innovations, IBM recognised the need to evolve its approach to remain competitive in the fast-paced technology landscape.

IBM's Design Thinking journey began with a mission to reinvent its enterprise software solutions. The company transitioned from a product-centric focus to a user-centric one. Instead of solely relying on technical specifications, IBM started by empathising with its customers. They started to understand customer’s pain points, and envisioning solutions that genuinely addressed their needs.

One of the key elements of IBM's Design Thinking success is its multidisciplinary teams. The company brought together designers, engineers, marketers, and end-users to collaborate throughout the product development cycle. This cross-functional approach encouraged diverse perspectives, fostering creativity and innovation.

IBM's commitment to Design Thinking is evident in its flagship projects such as Watson, a cognitive computing system, and IBM Design Studios, where Design Thinking principles are deeply embedded into the company's culture.

Elevate your Desing skills in Instructional Design – join our Instructional Design Training Course now!

Case Study 6. Oral-B’s electric toothbrush

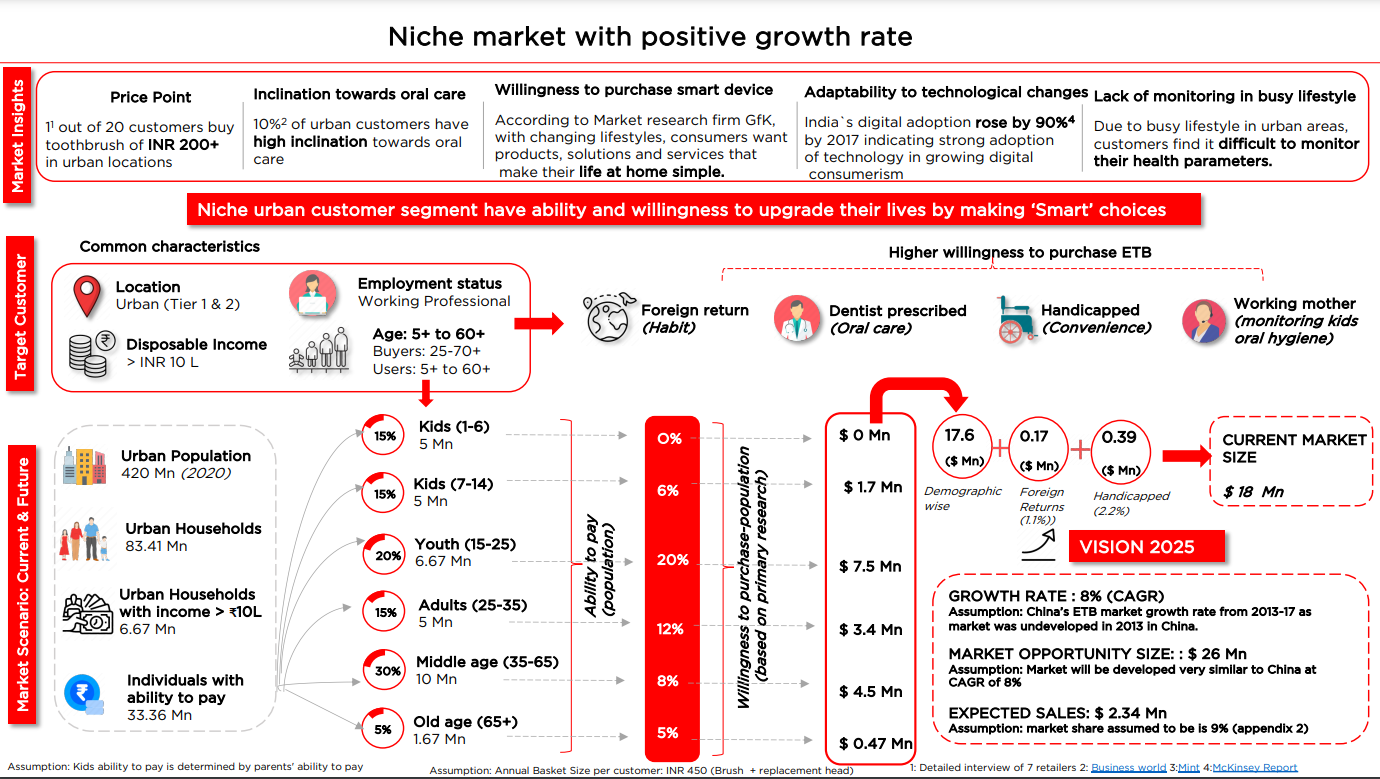

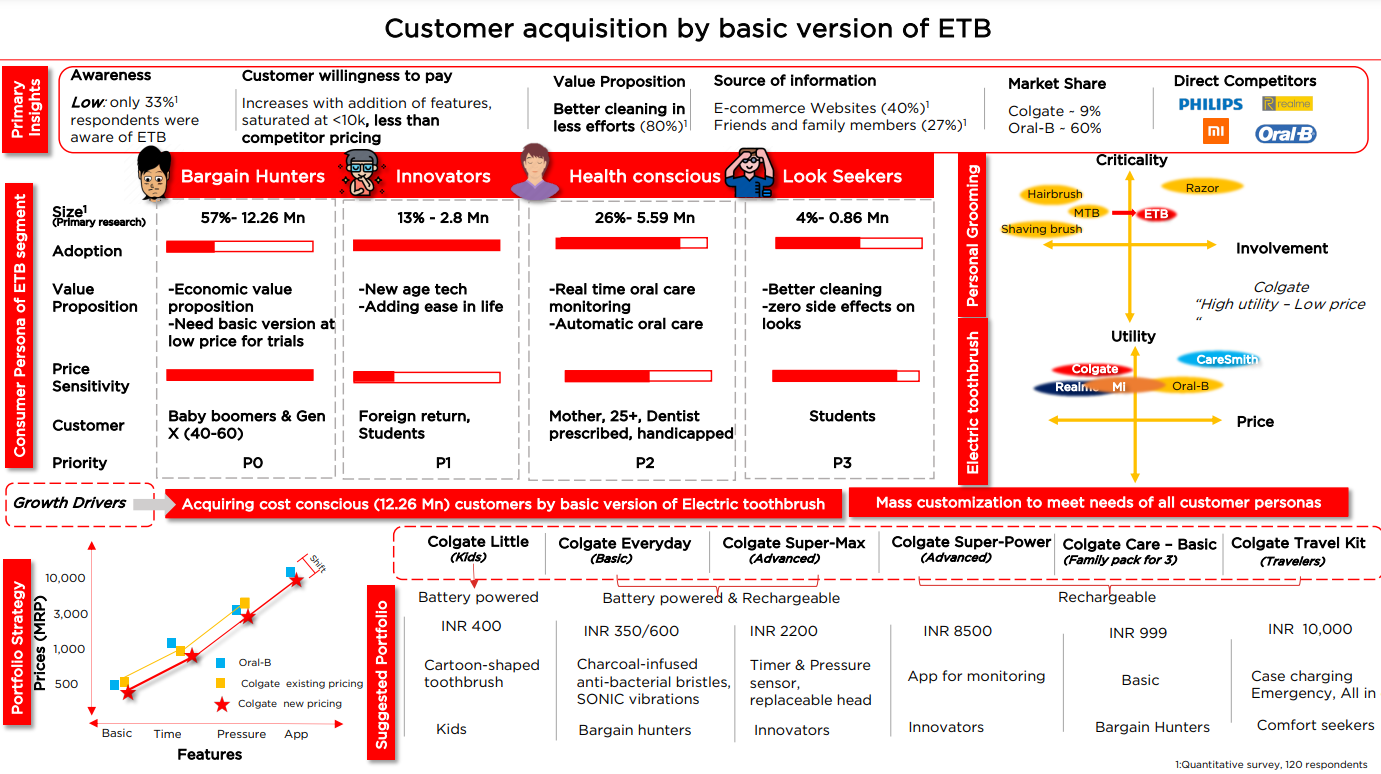

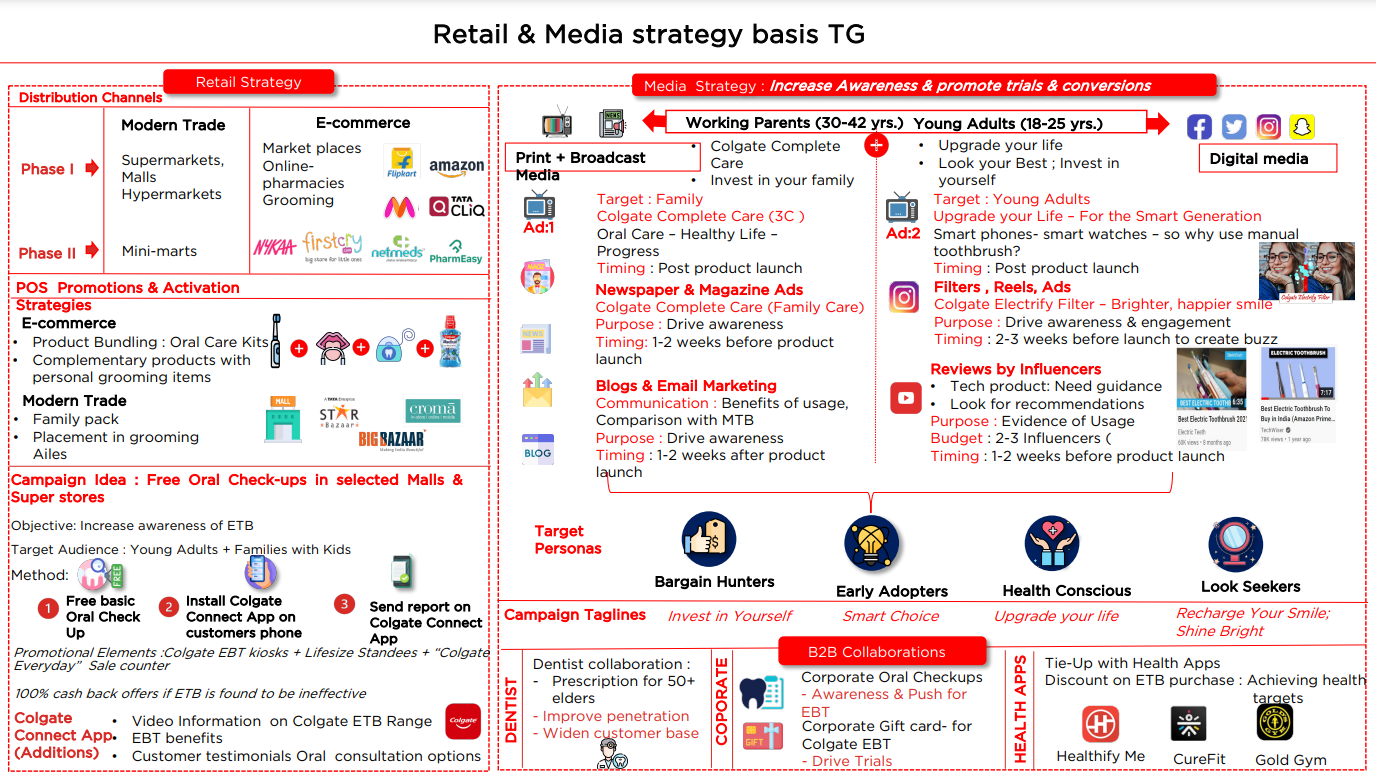

Oral-B, a prominent brand under the Procter & Gamble umbrella, stands out as a remarkable example of how Design Thinking can be executed in a seemingly everyday product—Electric toothbrushes. By applying the Design Thinking approach, Oral-B has transformed the world of oral hygiene with its electric toothbrushes.

Oral-B's journey with Design Thinking began by placing the user firmly at the centre of their Product Development process. Through extensive research and user feedback, the company gained invaluable insights into oral care habits, preferences, and pain points. This user-centric approach guided Oral-B in designing electric toothbrushes that not only cleaned teeth more effectively but also made the entire oral care routine more engaging and enjoyable.

Another of Oral-B's crucial innovations is the integration of innovative technology into their toothbrushes. These devices now come equipped with features like real-time feedback, brushing timers, and even Bluetooth connectivity to sync with mobile apps. By embracing technology and user-centric design, Oral-B effectively transformed the act of brushing teeth into an interactive and informative experience. This has helped users maintain better oral hygiene.

Oral-B's success story showcases how Design Thinking, combined with a deep understanding of user needs, can lead to significant advancements, ultimately improving both the product and user satisfaction.

Case Study 7. IDEO

IDEO, a Global Design Consultancy, has been at the forefront of Design Thinking for decades. They have worked on diverse projects, from creating innovative medical devices to redesigning public services.

One of their most notable Design Thinking examples is the development of the "DeepDive" shopping cart for a major retailer. IDEO's team spent weeks observing shoppers, talking to store employees, and prototyping various cart designs. The result was a cart that not only improved the shopping experience but also increased sales. IDEO's human-centred approach, emphasis on empathy, and rapid prototyping techniques demonstrate how Design Thinking can drive innovation and solve real-world problems.

Upgrade your creativity skills – register for our Creative Leader Training today!

Case Study 8 . Tesla

Tesla, led by Elon Musk, has redefined the automotive industry by applying Design Thinking to Electric Vehicles (EVs). Musk and his team identified the need for EVs to be not just eco-friendly but also desirable. They focused on designing EVs that are stylish, high-performing, and technologically advanced. Tesla's iterative approach, rapid prototyping, and constant refinement have resulted in groundbreaking EVs like the Model S, Model 3, and Model X.

From the minimalist interior of their Model S to the autopilot self-driving system, every aspect is meticulously crafted with the end user in mind. The company actively seeks feedback from its user community, often implementing software updates based on customer suggestions. This iterative approach ensures that Tesla vehicles continually evolve to meet and exceed customer expectations .

Moreover, Tesla's bold vision extends to sustainable energy solutions, exemplified by products like the Powerwall and solar roof tiles. These innovations showcase Tesla's holistic approach to Design Thinking, addressing not only the automotive industry's challenges but also contributing to a greener, more sustainable future.

Case Study 9. GE Healthcare