- Schools & departments

Projects, centres, networks and publications in English and Scottish Literature.

Research in English Literature, and the benefits it has brought to a range of partners and beneficiaries, have received outstanding endorsements in the latest Research Excellence Framework (REF 2021) – the UK’s system for assessing the quality of research in UK higher education institutions.

In Times Higher Education, English at Edinburgh is ranked fifth in the UK (out of more than 90 institutions) for the overall quality of its publications and other outputs, the impact of its research on people’s lives, and its supportive research environment.

Over 90 per cent of our research and impact is classed as world-leading and internationally excellent by Research Professional. 69 per cent is graded at the world-leading level – the highest of the REF’s four categories.

We have received this standout evaluation for research that ranges across literary history from the later Middle Ages to the present day, and is at the forefront of interdisciplinary fields including Digital and Environmental Humanities and studies of the history and future of books and material culture. Our submission covered collaboration with researchers in disciplines as varied as Education, Economic History, Informatics, and Astronomy.

We are particularly pleased that our research environment has been assessed as 100 per cent world-leading for the support we give to postgraduate and early career researchers, our research facilities, and our partnerships and collaborations within and beyond the University.

Browse Edinburgh Research Explorer for staff profiles, research outputs and activities

Selected research centres and networks.

Research centres and networks range from formal collaborations to informal groups of researchers working together on a theme or challenge.

A number are based in - or are affiliated with - English and Scottish Literature; others are based elsewhere in the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures (LLC), the University of Edinburgh, or the wider academic community, but involve our staff and students.

The groups provide opportunities for researchers at all career stages to work together with partners and stakeholders in organising events, workshopping publications, engaging audiences outside the academy, and exploring ideas for future projects and funding bids.

Here are just a few of our current groups, and significant networks that are no longer live but have left a legacy of networking and collaboration...

Centre for Medieval & Renaissance Studies

Spanning a range of disciplines in European, Islamic, American and Asian studies, including medieval literatures and cultures, the Centre brings together around 70 researchers across the University of Edinburgh.

Take me to the Centre for Medieval & Renaissance Studies website

Diaspolinks

Bringing together specialists in the fields of anglophone and francophone diasporas, this international network is unique in comparing the various diasporic communities’ responses to issues of identity, belonging and relocation in the specific contexts of British/French and Canadian immigration policies.

Take me to the Diaspolinks website

Digestive Modernisms

An informal interdisciplinary network meeting in-person and online, this group brings together researchers, artists, and writers interested in the gastronomics of modern literature and life. Spanning diverse critical contexts, from the medical humanities to posthumanism, Digestive Modernisms looks at food, diet, and gut health in modernist literature, art, culture and philosophy.

Take me to the Digestive Modernisms website

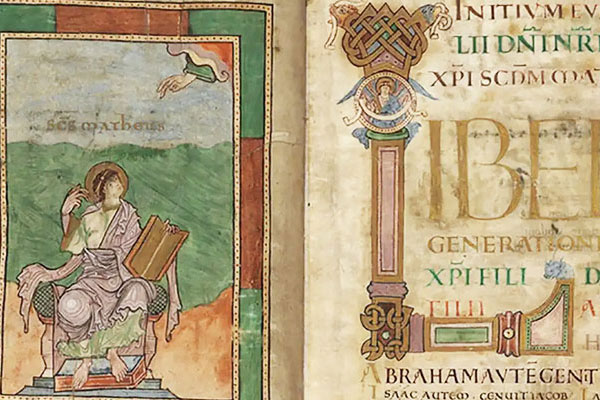

A collaborative initiative at the University of Edinburgh, Edition supports new research in all aspects of the history of the book, from traditional forms of bibliography, codicology and textual editing to the latest theoretical and digital innovations. Launched in 2024, it continues the legacy of the Centre for the History of the Book (CHB) which was active at the University of Edinburgh between 1995 and 2020. Edition's website hosts selected CHB video and audio resources.

Take me to the Edition website

Ethical Pressures on Thinking

Growing out of conversations started in a group on Emotionally Distressing Research, this is a forum for researchers experiencing the ‘pressure on thinking’ from the ethical dilemmas their research gives rise to. Involving researchers from across the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, including English and Scottish Literature and elsewhere in the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures (LLC), it embeds ethical reflection in research culture and collaboration.

Scottish Writing in the Nineteenth Century (SWINC)

Founded in 2008, SWINC builds connections between researchers working in the field of 19th century Scottish studies and fosters public awareness of the richness and diversity of Scottish culture in the period. The network supports early career researchers, including current holders of ARHC Studentships and Marie-Curie Fellowships, and runs workshops, lectures and other events, a number of which are associated with the 250th anniversary of Sir Walter Scott in 2021.

Take me to the SWINC website

Selected research projects

Beauty in the struggle and say their names: art of the black freedom movement.

Dr Hannah Jeffery’s interdisciplinary research focuses on the understudied role of Black muralism in the Black Freedom Movement. In the first of two recent projects, Beauty in the Struggle, she sought to uncover the empowering, educational, and self-affirming role Black-created interior mural art played in segregated public spaces in the USA, from enslavement to the early-twentieth century. In particular, the project explored how Black artists resurrected inspiring Black and African diasporic memory, history and culture to transform the interiors of segregated public buildings into sites of protest, creating visual platforms for Black liberation.

Drawing on unexplored archival materials, Beauty in the Struggle focused on the work of Charles White, Aaron Douglas, Hale Woodruff, Charles Alston, Robert Scott Duncanson, William Edouard Scott, and John Biggers. Say Their Names brought the research into the 21st century, and widened its scope beyond interior art and the USA to the commemorative street art which has marked a new age of international muralism since the death of Oscar Grant in 2009. For this project, Dr Jeffery created an online digital archive and curriculum tool preserving all known Black Lives Matter murals across the world.

Funded by a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship: September 2020 to August 2023 (Beauty in the Struggle), and by a Small Research Grant Award from the British Academy: September 2021 to June 2023 (Say Their Names)

LLC team: Dr Hannah Jeffery ( Principal Investigator; Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellow )

The British empire, colonialism, and cultural responses to famine and food crisis

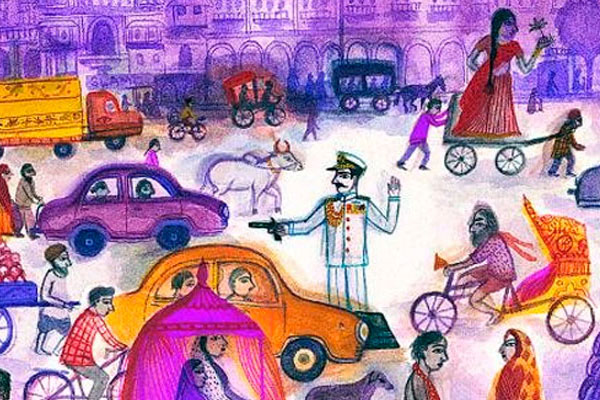

The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed a number of devastating famines in British colonies, resulting in a huge body of literary and artistic work and journalistic debate around their ‘man-made’ nature. While the Irish literary case, for example, is relatively well known, the same cannot be said of literary-cultural responses to the Indian famines, including the 1943 crisis in Bengal. Over a number of projects, Dr Sourit Bhattacharya is recovering famine works, and administrative and periodical sources by Indian and British writers and critics, including influential Scots. A key aim is to maximise visibility of events that were much debated at the time, but are now rarely discussed, despite having influenced anticolonial mobilisation and postcolonial food crisis debates.

This body of work aims to catalyse extensive, long-term research that historicises contemporary debates on neo-colonialism and global food crisis, and indigenous responses to them. Outputs will include an online literary bibliography of the Bengal famine, annotations of major works, and a short film on famine survivors. The projects variously include archival fieldwork in Britain and India, and collaboration with an international team of researchers, library professionals, and curators to form a Network on the British Empire, Scotland, and Indian famines. The Network will host academic conferences in Edinburgh and Guwahati, an authors’ workshop and knowledge exchange programme in Edinburgh, and a public engagement event in Kolkata.

Keep up to date with the Network on its website

Funded by a Research Incentive Grant from the Carnegie Trust: July 2021 to November 2022, and by a Royal Society of Edinburgh Network Award: March 2022 to March 2024

LLC team: Dr Sourit Bhattacharya (Principal Investigator)

The Carlyle Letters

Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) and Jane Welsh Carlyle (1801-1866) were prolific Scottish writers who corresponded with many of the outstanding cultural and political figures of their time in the UK, Europe and North America. The Collected Letters of Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle, Duke-Edinburgh edition is one of the major editorial projects in Victorian studies of the last half-century. Started by C.R.Sanders of Duke University, in co-operation with John Butt in Edinburgh, it has since amassed an archive of over 10,000 surviving letters, mostly in manuscript, the core collections being in the National Library of Scotland and Edinburgh University Library.

Since the publication of the first four volumes in 1970, the project has produced 48 (of 50) fully-edited, annotated and indexed volumes. Drawing on multiple scholarly collections, w ork proceeds simultaneously on both sides of the Atlantic. The publishers are Duke University Press in the USA, advised by academics from around the world. Other research papers have regularly appeared, and the project has held a number of conferences and published a free digital archive, the Carlyle Letters Online.

Search the Carlyle Letters Online by date, recipient, subject, or volume

Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the British Academy, the Binks Trust, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation and private donations.

LLC team: Professor Kenneth Fielding, Professor Ian Campbell, Aileen Christianson, Dr Jonathan Wild, Dr Katherine Inglis, Jane Roberts, Liz Sutherland

Disability-Led Theatre in Scotland: Birds of Paradise's History and Practice

Founded in Scotland in 1993, Birds of Paradise is today one of the most successful disability-led theatre companies in the world. Drawing on her previous research, including her award-winning book on Samuel Beckett and Disability Performance, Dr Hannah Simpson is working with the company to record its 30-year history, articulating their practice and ideology for the benefit of other theatre makers. The project’s main output will be a book published in the Palgrave Theatre and Disability series, released in multiple formats and shared with industry audiences in a series of events. Along the way, the researchers will contribute opinion and feature pieces to the industry and wider press.

As well as Bird of Paradise’s Robert Softley Gale (Artistic Director) and Máiri Taylor (Executive Director), the book is being co-edited by Judith Drake who has worked with the company over the course of her PhD on disability theatre in Scotland. In particular, Part One of the book - which explores Birds of Paradise’s production history - will capitalise on Drake’s work with the company archives, as well as an analysis of some of its particularly influential productions. The second part of the book will offer step-by-step, tried-and-tested practical guidance for other theatre companies, artists and venues. Aimed at developing their own accessible practice, the guidance will cover all aspects of the theatrical performance journey, from the rehearsal room to the auditorium.

Read Hannah Simpson’s Guardian article on disabled actors and Richard III

Funded by the LLC Research Fund and LLC Impact Fund: November 2023 to July 2024

LLC team: Dr Hannah Simpson (Principal Investigator); Judith Drake

Exhibiting the Written Word

Are there challenges or difficulties unique to the task of exhibiting books and manuscripts? What kinds of pressures and demands do librarians and curators face? How do policies and frameworks aimed at connecting archives, libraries and museums with the communities around them shape our approach to staging such exhibitions? Beginning with a workshop, and culminating in an advisory report that remains widely used, Exhibiting the Written Word brought academics, librarians and curators together to find out.

Exhibiting the Written Word was led by the Making Our Connections team comprising researchers from the University of Edinburgh (including the Centre for Research Collections) and the National Library of Scotland. Together with the core team, participants included the British Library, National Galleries of Scotland, National Trust for Scotland, Trinity College Dublin, University of Ulster, Edinburgh Napier University, Dublin City Library and Archive, Scottish Poetry Library, Seven Stories children's book centre and the Wordsworth Trust.

Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC): February 2011 - August 2011

LLC team: Professor James Loxley (Principal Investigator)

LitLong: Edinburgh

A unique exploration of the possibilities of big data for literary research, LitLong is a project to digitally map the ways in which Edinburgh has been used as a setting by myriad writers. Over two key phases, it has mapped around 47,000 excerpts from more than a million books made available by the British Library, the National Library of Scotland and the Hathi Trust, collectively spanning five centuries of writing. The project brings together researchers in literature, informatics and the digital humanities at three Scottish universities to text mine and analyse narratives. Its interactive map of literary Edinburgh has two visual interfaces: a website; and a free-to-download app.

Since 2014, LitLong has been embedded in Edinburgh’s UNESCO City of Literature digital and on-site programming, with character-led walking tours being a particularly popular addition to the city’s cultural offer. Through foregrounding marginalised voices, including on Wikipedia, the project has also inspired new work by over 80 of the city’s contemporary poets and prose writers whose work is published in the Umbrellas of Edinburgh anthology. Latterly, its methods have been adopted by Edinburgh International Book Festival and its partner Jalada Africa to map a series of transcontinental journeys and trace trajectories of African writing in English.

Visit the LitLong: Edinburgh website [external]

Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC): January 2014 - March 2015; January 2017 - January 2018

LLC team: Professor James Loxley (Principal Investigator), Dr Beatrice Alex (Chancellor’s Fellow)

Marshall Islands Project (MAP): Exploring experiences of displacement through the arts

Between 1946 and 1958, the US conducted 67 nuclear bomb tests across the Republic of the Marshall Islands, forcing many communities into open-ended exile, including over 2,300 miles away in Hawaii. Led by Professor Michelle Keown (LLC) and Dr Shari Sabeti (Moray House School of Education and Sport), the Marshallese Arts Project (MAP) aims to better understand the Marshallese experience of displacement, and to explore how strategies of resilience that remain within the community might be deployed to build educational and socioeconomic capacity in the future.

Collaborating with artists Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, Solomon Enos and Christine Germano, the project team ran a series of participatory arts workshops with school-aged children to generate new understandings of the unique historical trajectories and community development needs of Marshall Islanders. Raising international awareness of the effects of America’s enduring nuclear legacy in the Pacific, the project has led to the publication of the first Marshallese graphic novel, a video performance poem, improved pedagogical approaches in participating and other schools, and an anthology of poetry by children who have demonstrated significant personal growth through MAP.

Visit the MAP website [external]

Funded by an ESRC/AHRC Global Challenges Research Fund award: November 2016 - April 2018; AHRC Follow-on Funding: December 2018 - March 2019, and an EPSRC Global Impact Accelerator Account: February 2019 - January 2020.

LLC team - Professor Michelle Keown (Principal Investigator)

Our Bondage and Our Freedom: The Anna Murray and Frederick Douglass Family and their Intergenerational Fight for Social Justice

As a world famous African American author, activist and philosopher, Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) is often presented as an exceptional individual working in isolation. Our Bondage and Our Freedom breaks new ground by reinterpreting Douglass’ activism and authorship in relation to that of his wife Anna Murray, daughters Rosetta and Annie, and sons Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr and Charles Remond Douglass, as well as hundreds of other 19th century African American freedom-fighters on both sides of the Atlantic.

The project has involved recovering, digitising and interpreting over 1,000 documents, artworks and artefacts, and making these available to new audiences through four site-specific exhibitions, an award-winning book, free digital assets such as the National Library of Scotland’s 'Struggles for Liberty' learning resource, talks, walking tours, interviews and a documentary. Working collaboratively, the team of US and UK partners has helped educators, curators, and archivists to interpret the Douglass family’s intergenerational fight for liberation and to share the lives and works of nineteenth-century African American freedom-fighters with US and UK audiences in their thousands.

Read about our collaboration with the National Library of Scotland on Struggles for Liberty

Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC): August 2018 - January 2020

LLC team - Professor Celeste-Marie Bernier (Principal Investigator), Professor Andrew Taylor

Picturing Finance and The History of Financial Advice

Through two projects on the culture of finance – Picturing Finance and The History of Financial Advice – Dr Paul Crosthwaite's research has brought humanities approaches to bear on economic questions, helping us better understand the abstract, and often mystifying, domain of money, investment, credit and debt. Involving the Universities of Edinburgh, Manchester and Southampton, and galleries and other partners across the UK, the projects have used literary and cultural methodologies to explore the integral importance of visual culture to finance and to a critical questioning of some of its assumptions and practices.

Picturing Finance’s co-curated exhibition 'Show Me the Money: The Image of Finance, 1700 to the Present' reached around 70,000 people, producing acclaimed new work by commissioned artists, and receiving excellent reviews from the public and media alike. Free digital resources from both projects, including an app, MOOC, and eight quality-accredited lesson plans, have improved financial literacy - a relatively new addition to the National Curriculum, and one that has rapidly increased in importance as Britain prepares to meet the twin economic challenges posed by Brexit and the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Watch or listen to the research team talk about Show Me the Money: The Image of Finance on vimeo

Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC): March 2013 - September 2014; January 2016 - May 2019

LLC team - Dr Paul Crosthwaite (Co-Investigator)

Realising the healing potential of applied theatre

Working within the field of Applied Theatre, Nicola McCartney has developed a unique, research-led methodology that helps people affected by conflict or inequality to better interpret and address their life circumstances through dramaturgy. Her research has underpinned the significant international expansion of Edinburgh’s Traverse Theatre’s flagship education project Class Act which, between 2016 and 2019, developed 55 new plays by 120 young people working with various cultural practitioners in Russia, Ukraine and India.

In addition to Class Act and her own plays, Nicola worked with Dritan Kastrati, who was smuggled from Kosovo to the UK as a child and then spent many years in the care system. Their award-winning, co-written play How Not to Drown (2019) is a piece of physical theatre interweaving interviews with Kastrati’s own writing. In October 2020, McCartney was named as lead artist on the National Theatre Scotland project, Care in Contemporary Scotland, A Creative Enquiry. Involving local authorities, carers and cared for young people, this project enables her to continue her work on the positive impact of creative responses to experiences of the care system.

Watch or listen to the trailer for Holding / Holding On, a filmed reading of a work in progress script for Care in Contemporary Scotland

Watch or listen to theatre critic Mark Fisher talking about How Not to Drown as part of Made in Scotland 2019

Funded by various bodies including Traverse Theatre, the British Council, BBC (Emerging Artists Award), and National Theatre Scotland

LLC team: Nicola McCartney

Scotland and Russia: Cultural Encounters Since 1900

Scotland and Russia have a long tradition of mutual engagement and influence, going back to the Middle Ages and still thriving today. Drawing on the expertise of scholars, creative practitioners and the general public, Scotland and Russia: Cultural Encounters Since 1900 explores the full spectrum of these connections: from passive consumption of each other’s culture to ethnographic reflection upon it; from creative transformation of each other’s cultural products to professional collaboration in the creation of joint cultural capital.

In addition to three collaboratively-hosted academic conferences covering music, theatre, literature, art, politics and history, the project has organised concerts, a performance workshop, and talks by visiting speakers. Its website hosts an extensive cultural archive of textual, audio and visual materials - some newly translated and all brought together for the first time.

Visit the Scotland and Russia website [external]

Funded by the University of Edinburgh Challenge Investment Fund: 2014-2015, by the Universities of Aberdeen and Dundee, and by the Royal Society of Edinburgh Arts and Humanities Research Network Award: January 2015 - December 2016

LLC team: Dr Anna Vaninskaya (Principal Investigator), Dr Rania Karoula (Research Assistant)

Technicities of Illusion: Dynamism and deception in post-war literature

Since the mid twentieth century, a rapid rise in optical technologies has made the textual and the visual more intimately bound than ever. This project explored the ways in which post-war literature has contemplated the perceptual challenges posed by movement, optical illusion, and new media. In thinking about the implications of the kinetic in literature, it asked how motion is expressed, and what impact this had had on the ways we experience or 'read' the world.

Technicities of Illusion traced the lineage of technological literacy in the arts through archival collections of optical devices, artworks, digital design and literary responses. Reappraising the work of authors, sculptors, filmmakers, and designers, it identified the literary strategies that developed in Britain and America in the post-war period to keep pace with a culture increasingly driven by technological enhancement and the rapid flow of information. In doing so, Natalie Ferris built a new history of the ways we manage and visualise information, deepening our understanding of how we read, think, create, and write now.

Listen to Natalie talk about the work of experimental writer Christine Brooke-Rose on the TLS Voices podcast

Funded by a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship : October 2018 - September 2021

LLC team: Dr Natalie Ferris (Principal Investigator)

Travel, Environment, Sustainability: A literary and cultural history of Irish and Scottish coastal routes

Coastal Routes offers the first comparative study of a neglected archive of Romantic travel writing that explores the deep history of human-environment relationships along the environmentally fragile Atlantic coasts of Ireland and Scotland. Combining approaches from the Environmental Humanities, Archipelagic Criticism and Geocriticism, it examines the ways in which tourists construct landscapes as a resource; considers changing attitudes and values; and demonstrates how environmental narratives grew up around particular locations.

Coastal Routes thereby contributes to the UN’s 2030 Sustainability Agenda in relation to sustainable development of marine resources as well as consumption and production patterns. Uncovering lost environmental understandings captured in travel writing from 1770 to 1840 allows critical reflection on contemporary practices and future directions. Project outputs include a Special Issue of Nineteenth-Century Contexts on ‘Ecologies of the Atlantic Archipelago’ and a one-day workshop on ‘Scotland’s Coastal Romanticisms’ (hosted by Scottish Writing in the Nineteenth Century (SWINC) and The Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities).

Listen to Anna talk about 'The Beach Today' project with artist Christina Riley at the Scotland's Coastal Romanticisms workshop

Funded by a Marie Sk łodowska-Curie Actions Individual Fellowship: September 2020 - August 2022

LLC team: Dr Anna Pilz ( Marie Sk ł odowska-Curie Fellow), Professor Penny Fielding (Supervisor)

Writing the North

The Northern Scottish islands of Orkney and Shetland have both a rich literary history and an active community of poets and novelists at work today. Exploring the many continuities between the historic and the contemporary is challenging, given the location of the islands, and the geographic dispersal of the many people who can contribute to the process, including literary historians, museum professionals, writers, and their audiences. Bringing these groups together, Writing the North unlocked a range of archival and contextual material - shedding light on forgotten writers, and inspiring new work.

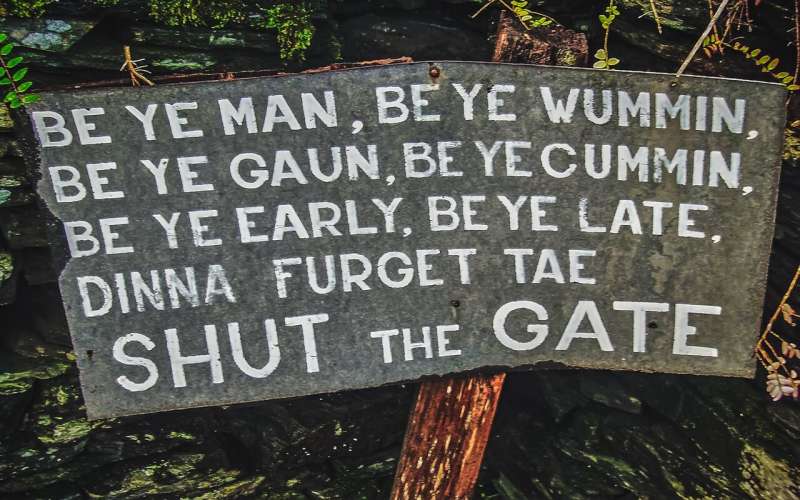

Arising out of Professor Penny Fielding's earlier AHRC Fellowship on Shetland and Orkney literature and the literary record of visitors to the islands, t he project involved a major six-week exhibition bringing together two collections at Shetland Museum and Archives. Associated activities and events included an animation, lesson packs for schools, digital resources, and a series of creative 'dialogues' resulting in "Archipelagos", an anthology steeped in Shetlandic and Orcadian history. Beyond Scotland, the project has acted as a model for preserving and celebrating minority languages and dialects, including through connections with Hudson’s Bay Company Archives in Manitoba, Canada. Although Writing the North has formally ended, related activities such as writing workshops, continue.

Visit the Writing the North website [external]

Funded by Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC): May 2013 - June 2014

LLC team: Professor Penny Fielding (Principal Investigator), Robert Alan Jamieson, Dr Alex Thomson

Postgraduate research and supervision

Doctorate-level study is an opportunity to make an original, positive contribution to research in literature and related fields.

As the oldest department of English Literature in the UK, based in one of the largest and most diverse Schools in the University of Edinburgh, we are the ideal place for PhD study.

We also offer a one year Masters by Research degree, which is a good stepping stone between undergraduate and doctoral study.

Our interdisciplinary environment brings together specialists in all periods and genres of literature and literary analysis. Given the breadth and depth of our expertise, we are able to support students wishing to develop research projects in any field of Anglophone literary studies.

Find out more about postgraduate study in English and Scottish Literature

Read our pre-application guidance on writing a PhD research proposal

Beyond the books

Beyond the Books is a podcast that gives you a behind-the-scenes look at research in the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures and the people who make it happen.

To date, hosts Ellen and Emma have talked to the following researchers from our community in English and Scottish Literature:

- Series 1: Episode 1 - Rachel Chung, PhD candidate in English Literature

- Series 1: Episode 2 - David Farrier, Professor of Literature and the Environment

- Series 2: Episode 2 - Anna Kemball, PhD candidate in English Literature

Browse all episodes of Beyond the Books

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Journal › Top Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature

Top Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on June 15, 2020 • ( 0 )

1. English Historical Review -(OXFORD) (https://academic.oup.com/ehr/pages/About)

2. ASIATIC: IITUM Journal of English Language & Literature ( https://journals.iium.edu.my/asiatic/index.php/AJELL )

3. English for Specific Purposes ( https://www.journals.elsevier.com/english-for-specific-purposes )

4. The Australian Association for the Teaching of English (AATE) ( https://www.aate.org.au/journals/english-in-australia )

5. English in Education (Wiley) ( https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/17548845 )

6. English World-Wide | A Journal of Varieties of English ( https://benjamins.com/catalog/eww )

7. European Journal of English Studies– Taylor & Francis Online ( https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/neje20/current )

8. Journal of English for Academic Purposes – Elsevier B.V. ( https://www.journals.elsevier.com/journal-of-english-for-academic-purposes )

9. Journal of English Linguistics- SAGE Journals ( https://journals.sagepub.com/home/eng )

10. Research in the Teaching of English-NCTE ( https://www2.ncte.org/resources/journals/research-in-the-teaching-of-english/ /)

11. The English Classroom – Regional Institute of English ( http://www.riesielt.org/english-classroom-journal )

12. World Englishes (Wiley Blackwell) ( https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/1467971x )

13. English Language & Linguistics – Cambridge Core ( https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/english-language-and-linguistics )

14. English Today-The International Review of the English Language-Cambridge Core ( https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/english-today )

Share this:

Categories: Journal

Tags: Best Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature , Free Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature , Gnuine Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature , Journals in English Literature , Literary Theory , Scopus Indexed Journals , Top Scopus Indexed Journals in English , Top Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature , UGC Approved Journals , UGC Approved Journals in English

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Literatures in English

Subject librarian.

Rebecca Wingfield

About the literatures in english collection.

Stanford Libraries’ collections of literatures in English support the study and teaching of all periods of literary history from the Middle Ages to the present. We collect contemporary fiction and poetry, literary criticism, academic journals on literary studies, and digital resources related to English literature from around the world, including the United States, Canada, the Anglophone Caribbean, Great Britain, Ireland, Africa, and South Asia. Stanford’s Special Collections hold several notable rare books and archival collections, including the Felton collection of British and American literature, the papers of John Steinbeck, and the papers of several notable postwar American poets, including Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, and Denise Levertov. The curator of American and British Literature provides research consultations, instruction sessions for classes, and helps students and faculty access materials related to literary studies in English.

Cecil H. Green Library

Further resources.

- Literature in English

- Modern Language Association of America (MLA) international bibliography

- Literature online

- Early English books online (EEBO)

- American fiction, 1774-1920

Department of English and Related Literature

English research

Field-defining research covering a wide range of periods, regions, languages and disciplines.

Our researchers have a unique approach to what literature is, what it does, how we read it, and how we write about it.

We cover the whole spectrum of English literary studies, including Africa, Australasia and the US. Our research expertise extends to the literature and language of other cultures – from ancient Greece to modern Pakistan.

The Research Excellence Framework 2021

- We’re a top ten research department according to the Times Higher Education’s ranking of the latest REF results (2021), and 98% of our research is rated 3* and higher.

Learn more about the 2021 REF results

Research strengths

The focal points of our research are our four major schools: Medieval, Renaissance, Eighteenth Century and Romantics, and Modern.

All staff and postgraduate researchers belong to at least one school, which creates the ideal environment for collaboration and discussion. The chronological range of our collective expertise enables opportunities for large-scale collaborations, and many staff members conduct research that crosses the historical boundaries of the schools.

Our researchers also work on a series of featured research projects .

Renaissance

Eighteenth Century and Romantics

Impact and engagement

Our research is underpinned by our belief in the intrinsic aesthetic and social value of literary texts, whether as agents of social and political change or of historical understanding.

We work closely with arts organisations, councils, schools and other partners to ensure our research contributes positively to society and culture.

- Remembering the Reformation

- Challenging perceptions of Dickens

- Writing by Muslims in South Asia and Britain

The Humanities Research Centre , based in the Berrick Saul Building, is an interdisciplinary hub for arts and humanities research.

Research centres

We are involved in a number of interdisciplinary research centres:

- Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies

- Centre for Medieval Literature

- Centre for Medieval Studies

- Centre for Modern Studies

- Centre for Narrative Studies

- Centre for Renaissance and Early Modern Studies

- Centre for Women's Studies

- Humanities Research Centre

Meet our research students

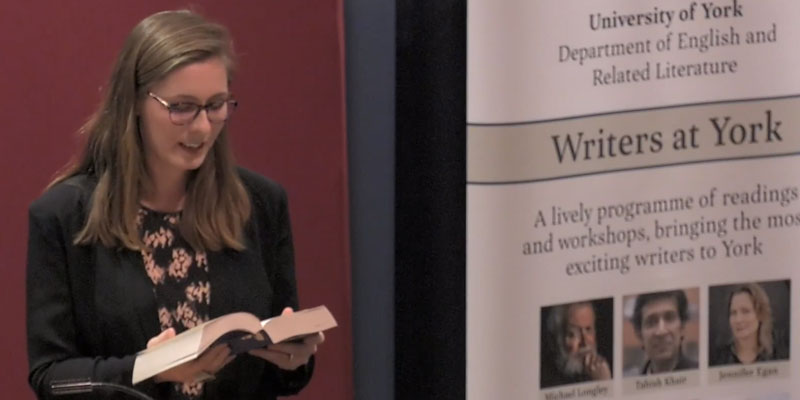

Writers at York

Writers at York is a lively programme of readings and workshops, bringing exciting new voices and some of the most important contemporary writers to York.

Our recent events have featured poets Denise Riley, Alice Oswald and Seamus Heaney, playwright David Edgar, novelists Graham Swift, Emma Donoghue, J. M. Coetzee, Booker-shortlisted novelist (and York PhD student) Fiona Mozley, and many others.

Explore our upcoming and past events

One of our recent events saw Dr Alexandra Kingston-Reese in conversation with New Zealand's Eleanor Catton, a prominent contemporary novelist.

Publications

See our recently published books and articles as well as forthcoming work.

Research degrees

Push the boundaries of knowledge in our supportive and stimulating environment.

Fellowships and Postdoctoral Research

Benefit from a dynamic research culture and excellent facilities.

Academic visitors

We welcome scholars who wish to work with us for up to one year.

- Aug 17, 2020

A guide to research in English literary studies

Updated: Jun 26, 2022

This guide introduces you to basic resources for doing research in English literary studies. Some of these resources are geared towards the British eighteenth century, which is my area of specialization, but some cut across periods and fields. You will probably be familiar with some of them, but others may be new to you. You will find this guide helpful whether you are writing a seminar paper, getting started on your dissertation, or need more advanced tools for locating primary and secondary sources.

Primary Sources

◾ Sources that used to require visits to distant archives are increasingly available on digital databases that you may be able to access through your university library. If you are looking for titles published in Britain from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, search for the English Short Title Catalogue ( ESTC ), the most extensively bibliography of primary sources in early modern Britain. The ESTC will help you find titles, but in order to locate the actual texts you should visit other databases that store sources. Two marvelous ones are Early English Books Online ( EEBO ) and Nineteenth-Century Collections Online ( NCCO ).

◾ If your field is the British eighteenth century, then your database of choice is Eighteenth-Century Collections Online ( ECCO ) . It holds more than a hundred thousand digitized texts from the eighteenth century, all of them text searchable. The reason why ECCO is so useful is that most texts published in the eighteenth century do not exist in modern editions. This includes not only hundreds and hundreds of novels that were never republished, but also journalism, book reviews, philosophical treatises, sermons, almanacs, diaries, political pamphlets, and so on. Once you get a sense of what your dissertation will be about, spend some time on ECCO doing keyword searches. This does not necessarily involve finding new sources to write chapters about (even though it can involve that); you may simply be interested in what eighteenth-century reviewers were saying about the novel or poem you are reading, or in how people wrote on the issues you are tracing (sensibility, women’s lives, commerce, elections, slavery, the imagination, human nature, and so on). You are very likely to find exciting sources you did not know about but which may be perfect for your purposes.

You may be able to access ECCO through your library website, as long as they have a subscription. There are also other eighteenth-century repositories you should consider, including Eighteenth-Century Journals (which holds rare journals printed between c.1685 and 1835) and the 17th and 18th Century Burney Collection . For additional resources, consult the website of the Lewis Walpole Library (a rare-book library specializing in the British eighteenth century): https://guides.library.yale.edu/british18thc

◾ If you are doing work on the Enlightenment, here are a few websites containing reliable versions of important primary sources: the ARTFL Project ( https://artfl-project.uchicago.edu/ ) gives you access to the complete works of Voltaire ( Tout Voltaire ) and to the full text of Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie . Both are in French. For an ongoing English translation of the Encyclopédie , consult The Encyclopedia of Diderot and d’Alembert ( https://quod.lib.umich.edu/d/did/ ). And for the complete works of David Hume, you can use Hume Texts Online ( https://davidhume.org/ ).

◾ If you read French and are looking for French-language materials, the closest equivalent to ECCO is Gallica, the digital library of the Bibliothèque nationale de France ( https://www.bnf.fr/en/gallica-bnf-digital-library ).

◾A different way of looking for potentially useful primary sources would be to consult the catalogs of presses that publish in our field. The Broadview Press has been publishing lots of previously unavailable eighteenth-century works (both fiction and nonfiction) in annotated editions. Check their website for a full list of titles: https://broadviewpress.com/product-category/english-studies/ .

◾Two final words about primary sources: (1) If you are working with sources available in modern editions, then keep in mind that not all modern editions are equal. Amazon sells lots of “print-on-demand” editions which you should avoid by all means: they are carelessly copied from online texts and may be distorted or miss important passages. It is also prudent to avoid editions by popular presses such as Signet or Vintage. Instead, work with editions prepared by an eighteenth-century scholar. Publishers like Oxford, Penguin, Norton, and others clearly identify the editor who prepared the text and the critical apparatus. Prefer these editions. And then, (2), in the case of highly canonical authors there often are modern editions considered to be the “standard” edition. These are viewed as the best extant editions of your source, and journals often expect you to use (and to quote) that particular edition in your articles. For example, if you are working on Samuel Johnson, the standard edition is the one published by Yale University Press; the standard edition for Henry Fielding is The Wesleyan Edition of the Works of Henry Fielding , while for Jane Austen it is The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Jane Austen. (If you are working on Austen, make sure to consult Jane Austen in Context , one of the volumes of the Cambridge Edition.) In most cases these are very expensive editions you may not be able to afford, but the library should have them. What I usually do is to begin work with a good paperback edition and then check out the standard edition when I sit down to write.

Secondary Sources

This is where you may feel paralyzed, since there is so much out there to know about. Where do you even start? Most students start by checking the library, asking people for recommendations, and consulting the bibliographies included in modern editions of primary sources. Those are all good methods, but there are better gateways into the world of secondary sources — ones that will make sure you are not missing the crucial article that came out just last year. You probably already know about databases such as Jstor and Project MUSE , which serve as aggregators for important journals in English. Jstor is good but Project MUSE is better, as it gives you access to more recent scholarship and often features abstracts of articles. But there are other resources out there, including the following:

- Bibliographies of English studies. These give you access to comprehensive lists of the existing scholarship on any given topic, and they exist both online and in print. The most important one in our field is the MLA International Bibliography , which you can learn about here . It is essentially an advanced search engine focused on scholarship in the field of modern languages and literatures. Online bibliographies like the MLA and the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature ( ABELL ) have the advantage that they are regularly updated. But you may also consult printed bibliographies, many of which offer annotations on titles, giving you a sense of an article’s or book’s contents before you dive into reading it. Book-format bibliographies usually include the word “bibliography” in the title, so they should be easy to search for (an example is Barry Roth’s An Annotated Bibliography of Jane Austen Studies , 1973-83 ). The advantage of such bibliographies is that they save you a lot of time — you can quickly gather which books and articles you need to read and which ones you can safely skip. While useful, however, they inevitably get dated and must be used alongside more current material.

- Yearly reviews . These serve a different role than bibliographies. You can use them to get a sense of what is available out there, but they tend to be less comprehensive than a proper bibliography. Their advantage, however, is that they provide brief reviews of the listed items. The most comprehensive yearly review for secondary sources in English Studies is Oxford’s The Year’s Work in English Studies ( YWES ), available at https://academic.oup.com/ywes . Once a year YWES publishes a 1,500-page volume, fully available online, reviewing relevant books and articles in all periods of British and American literature, organizing them by section. There are sections, for example, entitled “Old English,” “The Eighteenth Century,” “The Victorian Period,” and “American Literature to 1900.” You can go straight to the section that matters for you and search for reviews on the author/source you are interested in. This serves as a shortcut into the world of secondary literature, allowing you to read many reviews at one sitting and deciding which articles/books you should read in full and which ones you can safely skip.

If you are doing work in the eighteenth-century, then make sure to also use The Scriblerian and the Kit-Cats ( https://muse.jhu.edu/journal/567 ), available on Project MUSE. The Scriblerian reviews all articles and books on canonical eighteenth-century authors including Aphra Behn, Daniel Defoe, Eliza Haywood, and Henry Fielding.

- Surveys of recent studies: These are different than either bibliographies or yearly reviews, in that they consider trends in the field. The best example is the yearly “omnibus” essay published by SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500-1900 covering recent developments in four different fields: “The English Renaissance” (Winter), “Tudor and Stuart Drama” (Spring), “The Restoration and Eighteenth Century” (Summer), and “The Nineteenth Century” (Autumn). Once a year, SEL invites a major scholar in each of these fields to survey approximately 100 books published the previous year and write a long review essay. The essays discuss individual books but focus on describing the state of the field and identifying trends in the scholarship. Reading (or even browsing) a few of these essays will give you a good sense of the conversations currently taking place, and may help you decide where you belong and who your interlocutors are. You can then compile a list of sources you want to consult more directly.

A different type of survey, organized by topic, is published by the online journal Literary Compass , which regularly publishes articles covering scholarship on themes such as gender studies, ecocriticism, memory studies, literature and technology, secularism, and so on.

- Metacritical studies. Just as there are studies of literary history, there are studies of studies of literary history. A good example is the Readers’ Guides to Essential Criticism series, published by Palgrave ( https://www.macmillanihe.com/series/readers-guides-to-essential-criticism/14520/ ). If you are working on the rise of the novel, for example, I can’t recommend highly enough Nicholas Seager’s The Rise of the Novel: A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. It surveys, in brief and informative chapters organized chronologically, the main books written on the rise of the novel both before and after Ian Watt’s The Rise of the Novel (1957), separating them by topic (feminist studies, postcolonial studies, and so on). The same series features books surveying decades of scholarship on Gothic fiction, Virginia Woolf, postcolonial literature, children’s literature, Jane Austen, literature and science, Shakespeare, and a lot else.

- You probably already know the Cambridge Companion series: these are collections of essays targeted at students and scholars seeking an entry into a new subject.

- Dedicated online journals. If you are doing work on Jane Austen, make ample use of the online version of Persuasions , the journal of the Jane Austen Society of North America ( http://jasna.org/publications/persuasions-online/ ). Make sure, in particular, to check the bibliographical essays, which cover the year’s output in Austen studies. If you are working on Defoe, make sure to check Digital Defoe ( https://digitaldefoe.org/ ).

This list is far from exhaustive, and is limited by my knowledge of the field. If you are working outside of traditional British literary history, consult a professor who specializes in your field and ask them for similar resources. For example, my colleague Dr. Margaret Galvan recommends this page to students looking for scholarship on comics. Other fields very probably benefit from field-specific bibliographies, aggregators, review journals, digital databases and other resources you may not know about. It's worth asking.

Three important reference works

This should go without saying, but if you are planning to quote definitions from a modern dictionary, the dictionary to quote is the Oxford English Dictionary ( OED ). The OED has several advantages over more popular dictionaries: it is incomparably more comprehensive, it provides rich etymological information on every entry, and — most importantly for our purposes — it provides quotations to illustrate how words were used in past historical periods. It shows, for example, how the word “novel” changed meanings over the course of the centuries.

If, by contrast, you are looking for how a word was defined in the eighteenth century, you can use the OED in conjunction with Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755), which the University of Central Florida is currently in the process of digitizing: https://johnsonsdictionaryonline.com/ .

Another source you need to know is the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ( DNB ) . Also available through library subscription, the DNB is the source to go if you need a biography of a British figure. Unlike popular sources such as Wikipedia, the DBN is written by experts — thus the entry on Jane Austen is written by the influential Austen scholar Marilyn Butler, while the entry on Daniel Defoe is written by Defoe’s most important biographer, Paula R. Backscheider. The entries often consist in summaries of the standard biographies with updated information.

Recent Posts

Should you get a guinea pig?

Did Schrödinger think that a cat can be dead and alive at the same time?

Guinea pigs are neither pigs nor from Guinea. Then why are they called that in English?

Comentarios

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 November 2021

The role of literary fiction in facilitating social science research

- Bryan Yazell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2263-3488 1 , 2 ,

- Klaus Petersen 2 , 3 ,

- Paul Marx 3 , 4 , 5 &

- Patrick Fessenbecker 6 , 7

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 261 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

6884 Accesses

2 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scholars in literature departments and the social sciences share a broadly similar interest in understanding human development, societal norms, and political institutions. However, although literature scholars are likely to reference sources or concepts from the social sciences in their published work, the line of influence is much less likely to appear the other way around. This unequal engagement provides the occasion for this paper, which seeks to clarify the ways social scientists might draw influence from literary fiction in the development of their own work as academics: selecting research topics, teaching, and drawing inspiration for projects. A qualitative survey sent to 13,784 social science researchers at 25 different universities asked participants to describe the influence, if any, reading works of literary fiction plays in their academic work or development. The 875 responses to this survey provide numerous insights into the nature of interdisciplinary engagement between these disciplines. First, the survey reveals a skepticism among early-career researchers regarding literature’s social insights compared to their more senior colleagues. Second, a significant number of respondents recognized literary fiction as playing some part in shaping their research interests and expanding their comprehension of subjects relevant to their academic scholarship. Finally, the survey generated a list of literary fiction authors and texts that respondents acknowledged as especially useful for understanding topics relevant to the study of the social sciences. Taken together, the results of the survey provide a fuller account of how researchers engage with literary fiction than can be found in the pages of academic journals, where strict disciplinary conventions might discourage out-of-the-field engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Conceptualizing science diplomacy in the practitioner-driven literature: a critical review

Pierre-Bruno Ruffini

Lifting the smokescreen of science diplomacy: comparing the political instrumentation of science and innovation centres

Elisabeth Epping

A bibliometric analysis of cultural heritage research in the humanities: The Web of Science as a tool of knowledge management

Ionela Vlase & Tuuli Lähdesmäki

Introduction

Interdisciplinary research has become the buzzword of university managers and funding agencies. It is said that researchers need to think out of the box, be innovative and agile, and—last but not least—be curious about other disciplines in order to solve the complex challenges of the modern world. The tension inevitably generated by calls for more interdisciplinary work between university administrators on the one side and researchers on the other risks obscuring a fundamental question: what exactly is new about interdisciplinary research in the first place? For all the handwringing about interdisciplinarity, there is no clear consensus about what the boundaries of a given discipline are in the first place. Debates have waged over the last several decades about the divisions between the sciences and the humanities, their origins, and possible methods for rectifying them. Perhaps most famously, British scientist and novelist C.P. Snow identified “two cultures” in the academy separated by “a gulf of mutual incomprehension” ( 1961 , p. 4). According to Snow, “literary intellectuals” and “physical scientists” not only distrusted each other’s pronouncements, but fundamentally saw the world differently ( 1961 , p.4, 6). Although this assessment has been influential in framing these respective disciplines for decades, its presentation of a binary division between the hard sciences and the arts does not account for the fields of study with overlapping interests and, at times, borrowed methodological tools: the social sciences and literature departments.

The social sciences and literary studies share an indelible link by virtue of their twinned emergence as academic disciplines in the early twentieth century. Both disciplines in the broadest sense share a keen interest in understanding and describing human behavior and social relationships. However despite—or perhaps owing to—these similarities, the disciplines have historically identified themselves in terms of opposition. On one side, Émile Durkheim’s Rules of Sociological Method, published in 1895, defined the discipline in terms of positivism and quantitative study. On the other side, foundational literature scholars such as Matthew Arnold and F.R. Leavis understood literary study as a crucial component to the project of invigorating the national culture: to identify among the mass of popular culture the most elite examples of art. Critics in this early school of literary study therefore understood literature less as a mirror of society and more as a way to access what is best about cultural ideals or humanistic achievement (Arnold, 1873 ; Leavis, 2011 ). In this early context, social scientists were more interested in making society itself the object of study. While the features of each respective field have undoubtedly changed dramatically over the past century, this underlying division regarding the “science” in the social science persists. If the social scientist and literature scholar can speak with some degree of shared comprehension, they nonetheless are beset by disciplinary boundaries that make the task of mutual exchange harder than it might otherwise appear.

The decision to better document the uses of literature within the social sciences was born from an overarching drive to understand literature’s impact on researchers that often escape notice. After all, literary scholars are in general familiar with (if not thoroughly informed by) the works of sociologists, economists, and political scientists. Moreover, they are likely to be comfortable both with using the toolset of the social sciences in their own work and, more to the point, citing sociologists such as Émile Durkheim, Erving Goffman, and Bruno Latour. Over the last decade, for instance, several prominent literary scholars have advocated for a descriptive model for analyzing literary texts modeled on the social sciences (e.g., Love 2010 ; Marcus and Love, 2016 ). This relatively recent turn to the social sciences does not begin to consider, of course, the much longer history of literary scholars drawing critical concepts from the Frankfurt School (such as Theodor Adorno or Jürgen Habermas) or, more significantly, the works of Karl Marx. All of which is to say, one can easily expect references to sources broadly associated with the social sciences when reading a literary studies monograph.

However, if it is clear that literary scholars are familiar with prominent works by social scientists, it is much less apparent if the reverse is true. In an essay in World Politics, the political scientist Cathie Jo Martin outlines the profound insight literary sources can offer the field. Novels and other literary fiction provide “a site for imagining policy”, help define shared group interests, and create narratives that legitimize systems of governance (Martin, 2019 , p. 432). Elsewhere, Nobel prize-winning economist Robert J. Shiller calls for greater engagement with literature and fiction in Narrative Economics (2019). However, as we show below, cases of social scientists explicitly acknowledging literary sources are few and far in between. Rather than articulate yet another call for better dialog between the disciplines, we instead seek greater insight into the way social scientists are already referring to, engaging with, or simply using literature in their field as researchers and teachers. As explained in detail below, this task is not as straightforward as it may seem.

Our project proceeded in two steps. The first was a qualitative study of social science articles that included references to literary authors drawn from the collection of social science journals cataloged on the JSTOR digital library. The evaluation of literary references captured in our study (outlined below) made it possible to track the proliferation of literary sources across social science research and to create a loose typology of these uses. For the second step, we developed a survey for social science researchers to elaborate on how, if at all, their work engages with works of literary fiction. Before going into the field, the survey was tested and discussed with a small number of academics to ensure that the items capture the concepts of interest. The survey was then sent electronically to 13,784 researchers at all stages (from PhD students to full professors) from the top 25 social science departments as ranked in 2019 by Times Higher Education (World University Rankings).

If academic departments are guardians of their disciplines, then this sample of prominent departments might reflect the international standard for their respective fields. In other words, researchers attached to these institutions may be more inclined to protect conventions than to go against the grain. In contrast, we can imagine that scholars at smaller schools, colleges, or cross-disciplinary research centers might be more inclined to engage with other disciplines. Focusing on the former institutions rather than the later, our survey finds hard test cases for our questions about the use of literary references in social sciences. Finally, by calling attention to the different forms of influence literature may (or may not) assume, the survey made it possible to dwell in more detail on how social scientists esteem literary fiction as a tool for understanding social concepts.

Before conducting our survey, we first developed a typology of what we term uses of literature within the social sciences. This typology is the result of an ongoing project seeking to understand how literature might already play a role in the social sciences, no matter how small this role might appear at first glance. Our investigations were further motivated by the distinct lack of sources on the subject. While there are a number of prominent cases that call for social scientists to incorporate the insights of literature into their research (e.g., Shiller, 2019 ) and teaching (e.g., Morson and Schapiro, 2017 ), there are hardly any that demonstrate how (and where) they might already be doing so. For those of us who wish to expound on the value of not only literature per se but the study of literature specifically, a thorough account of how experts in an adjacent field like social science might already incorporate literary objects in their scholarship is a critical starting point. The absence of a generalized account of the field therefore required us to generate our own.

To do so, we first devised a plan to comb through the entire catalog of published social science articles on JSTOR, which spans nearly a century’s worth of material. Our goal at this point was to identify and categorize where and how social scientists refer to literary fiction in their published work. As will become clear, this approach’s limitations—namely, its reliance on a pre-determined list of searchable terms—set the groundwork for our survey, which was designed to account for surprising or unexpected responses. Nevertheless, the survey provided valuable insight into the more fleeting references to literary fiction in published social science research.

A brief account of this JSTOR project is useful for contextualizing the results of our social science survey. First, it was necessary to generate a delimited archive of social science articles that use, in some shape or another, literary sources. For the sake of producing an adequate number of sources, we composed a list of search terms that consisted of 30 prominent Anglophone authors, along with two famous literary characters, Robinson Crusoe, and Sherlock Holmes (Fig. 1 ). To determine these search terms, we cross-referenced popular online media articles (including blogs, short essays, and user forums) that offered broad rankings of, for example, the most important authors of all time. To best address the historical breadth of the JSTOR catalog, the names were edited down further to focus on authors who published before the middle of the twentieth century. It goes without saying that this initial list was far from exhaustive. Instead, it was intended to produce a large enough body of results in order for us to further generate a working typology of literary references as they appeared in the articles. Footnote 1 Second, we conducted a qualitative analysis of these articles alongside the rough typology of uses Michael Watts, Professor of Economics at Purdue, outlines in his study of economics and literature—the only workable typology we found.

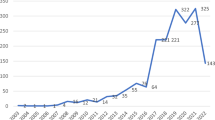

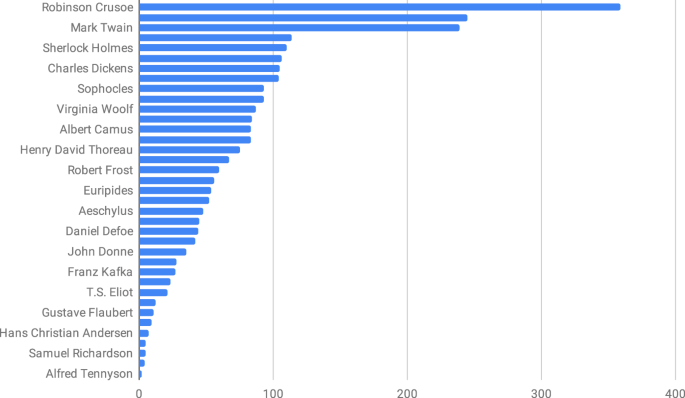

Chart displays search terms (author name or fictional character name) and their corresponding total number of appearances across all social science articles on JSTOR. Figure shows 19 most popular results from the compiled search term list.

According to Watts, economists who engage with literature to any degree tend to do so according to four different categories: 1. eloquent description of human behavior; 2. historical evidence conveying the context of a particular time or place; 3. Alternative accounts of rational behavior that complement or challenge economic theory; 4. Evidence of an antimarket/antibusiness orientation in esthetic works. ( 2002 , p. 377)

When viewed alongside the JSTOR articles, however, the limitations to Watts’s typology were apparent. Most immediately, the emphasis on what one might call deep or sustained engagements with literature means that his typology will not capture those more fleeting uses of literature that make up the vast majority of literary references in the social science archive. Once one recognizes these limits, it becomes clear that any categorization or typology of literature in social science must be sufficiently flexible enough to capture the many and often surprising ways that the disciplinary fields might intersect. Of course, this latter point is underscored by the fact that Watt’s original typology is concerned with economics only. By expanding our search to include the social sciences in general, we allow for a wider scale for evaluating literature’s usefulness as seen by, for instance, political scientists, social theorists, and behavioral economists. After reviewing the JSTOR set of articles, we expanded on Watt’s initial typology to produce a more encompassing categorization of literary uses that better accommodated the range of literary references as they appeared in the archive. Ultimately, we determined that an expanded typology of uses of literature as they appear in published social science articles must include several more categories, never mind the four in Watts’s initial outline:

Literature as argument

Causal Argument/Historical data: marks studies that see literature as an agent of historical change along the lines of something a historian of the period can recognize.

Alternate Explanation: notes studies that see literary writers as rival social theorists whose arguments warrant proper countering.

Philosophical Position: refers to studies that associate an author with an argument that is developed or sustained across that author’s body of work.

Literature as context

Historical Context: designates studies that use information from literary texts as a way of characterizing a particular historical period, without claiming that the work was an agent of change in the period.

Biography: refers to studies that cite biographical details of an author or literary source as a way of situating concurrent historical events.

Literature as metonym

Cultural Standard: names studies that refer to literary texts as a cultural metonym, for example using Shakespeare as a way of referring to Renaissance England or to Western Culture as a whole.

Parable: designates studies that refer to a literary object that has lost its original literary contextualization and now stands in for something else entirely (e.g., Robinson Crusoe as a parable for homo economicus).

Literature as decoration

Literary effects/style: accounts for those literary texts that are evoked subtly via an author’s style or phrasing.

Decoration: names instances when the references to a literary text appear merely decorative and play no significant role in the argument.

Nonfiction quote: denotes direction quotations attributed to authors outside their published works.

Literature as Inspiration: marks moments in which a literary text plays no direct role in the argument but inspired the scholar’s thinking.

Literature as Teaching Tool: acknowledges instances where scholars use literary texts within the classroom or to help explain a concept.

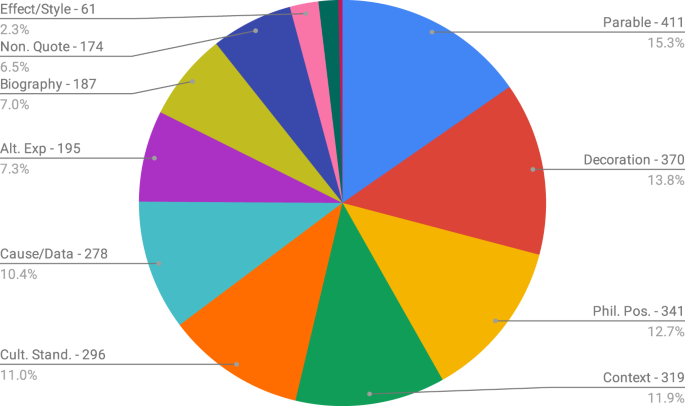

As this expanded typology suggests, our initial assessment of the JSTOR articles highlights literature’s wide range of applications within the social sciences (Fig. 2 ). Moreover, it jumpstarts a dialog on what, exactly, constitutes a use of literature within this field. After all, it seems significant that a great portion of literary references as captured in the JSTOR survey are essentially non-critical uses—pithy quotations from authors or famous literary epigrams—when viewed from the perspective of literary studies. Nonetheless, to account for these references to literature is to acknowledge something of the role literary fiction per se plays, if not in the entire field of social science research, then in the academic conventions of social science publishing.

Chart shows the proportion of literary typographies across JSTOR’s social science catalog from among our compiled search term list. The presented types originate from our expanded typography based on Watts’s categorisations.

At the same time, our attempts to expand this typology ran into several hurdles of its own. First and foremost, our ability to generate search results from the JSTOR archive was limited by the terms we used: because any search for “literature” or “fiction” produces too many non-applicable and generalized results, one must enter specific search terms (e.g., William Shakespeare; Virginia Woolf) to produce relevant results. Along similar lines, our typology can only take shape in view of these limited sources; it is after all possible that an author or literary text that did not appear on our initial list has been received by social scientists in ways that confound expectations beyond even our expanded typology.

Finally, our reliance on both pre-conceived search terms and archived research articles prevents us from evaluating the newest trends in both literature as well as social science research. As our survey results below demonstrate, there is ample evidence that literature produced within the last twenty years has an outsized impact on those social scientists who acknowledge literary fiction as an influence in their work. The conventions of academic publishing in non-literary fields, however, might prevent researchers from likewise acknowledging these contemporary examples in their published material in favor of more familiar, canonical examples. In view of the affordances and limitations to our initial JSTOR study, we decided to approach the subject of literature and social science from another direction: by going directly to the source.

If publications are the end products of academic work, the product does not always reflect all details of the research process. Nobody leaves the scaffolding standing when the house is completed; likewise, the notes, readings, and other sources of inspiration that lay the foundation for an article or academic monograph often go unacknowledged. To be sure, simply searching for references to literary fiction in the published text of these sources is likely to return some results—for instance, the frequent conflation of the homo economicus model with the protagonist of Robinson Crusoe, albeit in a manner that elides any reference to Daniel Defoe, the author (Watson, 2017 ). As the example of Crusoe suggests, the small pool of literary sources that appear in the text of social science articles cannot adequately account for the wide range of influences literature might have at all stages of research. To better capture these invisible or unacknowledged uses of literature in the social science, we decided to simply ask social scientists themselves. The survey asked a few simple questions on their use (or not) of fictional literature in any stage of their academic work. The survey questions are included in the supplementary material as supplementary note . We received 875 responses at a response rate of 7 percent, a number which we deemed acceptable for allowing us to detect some overall patterns. Given the use of THE rankings, the sample is dominated by North American and European social science departments. The sample includes all career stages: Ph.D students (35 pct.), postdocs and assistant professors (20 pct.), and tenured staff (42 pct.). It includes the four major social science disciplines: economics (20 pct.), sociology (31 pct.), political science (26 pct.), psychology (19 pct.), whereas a small group (4 pct.) identified with other disciplines. A full demographic breakdown (Table S.1) is included in the supplementary material .

Discussion: what do social scientists say?

To be clear, not all social scientists use literature in a manner conforming with our typology above or even consider literature a factor in their work life. In the survey, we focused on the non-explicit uses of literature and the considerations behind their uses. In other words, the survey is meant to supplement our findings from the study of social science journals from the JSTOR digital library. The survey should not be taken as a test of the above-mentioned categories developed from the empirical study of academic publications. Still, it is possible to glean some points of overlap between the two approaches. Several of these categories can be easily applied to responses from the survey, especially the categories relating to literature’s inspirational value or its usefulness as a teaching tool. At the same time, other categories that feature heavily in the published articles—especially “literature as decoration” and “literature as metonym”—were hardly mentioned at all in the survey responses. The gap between what social scientists say about literature and what appears in social science articles reiterates the value of the survey, which captures some of the underlying motivations for using literature (or not) that otherwise would not come across in view of published academic work.

Even considering the general self-selection bias—i.e., respondents who react positively to the idea of using literature are also more likely to participate in the survey—93 percent agreed that “Literature often contains important insights into the nature of society and social life”, while only 2 percent disagreed. However, it is one thing to acknowledge that literature offers general insights into life and quite another to affirm that literature plays a role in individual research biographies. To address this issue, we posed the question if “Reading literature played a role in the formation of your research questions or the development of your research projects.”

We were somewhat surprised to learn that this was the case for almost half of the respondents (46 precent agree or totally agree), and only a third (34 percent) rejected this premise (Table 1 ). Looking at the comments in the open sections shed light on this. For some researchers there was a very clear link. For example, one respondent explained: “Toni Morrison and other women of color (Ana Castillo, for example) greatly enriched my understanding of the role of gender in society (I am a man).”

Raising the bar even higher, we then asked about publications. Publications are arguably the most delicate matter in our survey. After all, publications can make or break careers inasmuch as they factor into promotions and tenure reviews. In response to our publishing question (“How often do you quote or in other ways use a work of fiction in your publications”), 25 percent recorded occasionally using literary fiction in some form and an additional 13 percent affirmed doing so often or very often. In other words, almost 40 percent of the respondents acknowledge using literary sources in their publications (Table 2 ).

However, it must be stressed that these uses vary in form and substance. Based on our qualitative assessment of a subset of social science sources (outlined above), we found that explicit engagements range from the superficial (e.g., brief quotations of famous quips or observations from literary sources), the decontextualized (e.g., Robinson Crusoe functions only as a model of economic behavior), to more sustained engagements with the arguments or ideas presented in literature (e.g., Thomas Piketty’s references to Jane Austen and Balzac in Capital in the Twenty-First Century). In other words, a great many of these applications of literature do not resemble the type of work one finds in literature departments. Moreover, the depth or method for engagement is rather unsystematic.

Of course, publications and research only constitute part of the work academics do at the university. Our survey also asked about teaching in order to capture other literary uses that published papers are unlikely to acknowledge. As noted above, Robinson Crusoe appears in textbooks on microeconomics in the figure of the homo economicus. Elsewhere, there are several examples of sources who call for incorporating literary fiction in the teaching of the social sciences in order to benefit from the imaginative social logics embedded in, for instance, science fiction novels (e.g., Rodgers et al., 2007 ; Hirschman et al., 2018 ). As our survey demonstrates, most of the respondents use or have used literary sources as pedagogical tools: less than a third (30 percent) never do so, most do so at least sometimes, and a few (12 percent) frequently use literature in their teaching (Table 3 ).

If we had expanded the category from literature to art in a wide sense (including, for example, movies, television series, paintings, and music) we suspect the numbers would have been significantly higher.

Finally, our survey provides some insight into what characterizes social scientists who use literature in their work. We generally find only small differences between disciplines within the field of social science, with economists marginally more skeptical of literature’s usefulness in the classroom than researchers in sociology, political science, and psychology (Table 3 ). This confirms earlier findings. A survey from 2006 showed that 57 percent of economist disagreed with the proposition that “In general, interdisciplinary knowledge is better than knowledge obtained by a single discipline.” For psychology, political science, and sociology the numbers were 9, 25 and 28 percent respectively (Fourcade et al., 2015 ).