Master the 7-Step Problem-Solving Process for Better Decision-Making

Discover the powerful 7-Step Problem-Solving Process to make better decisions and achieve better outcomes. Master the art of problem-solving in this comprehensive guide. Download the Free PowerPoint and PDF Template.

StrategyPunk

Introduction

Mastering the art of problem-solving is crucial for making better decisions. Whether you're a student, a business owner, or an employee, problem-solving skills can help you tackle complex issues and find practical solutions. The 7-Step Problem-Solving Process is a proven method that can help you approach problems systematically and efficiently.

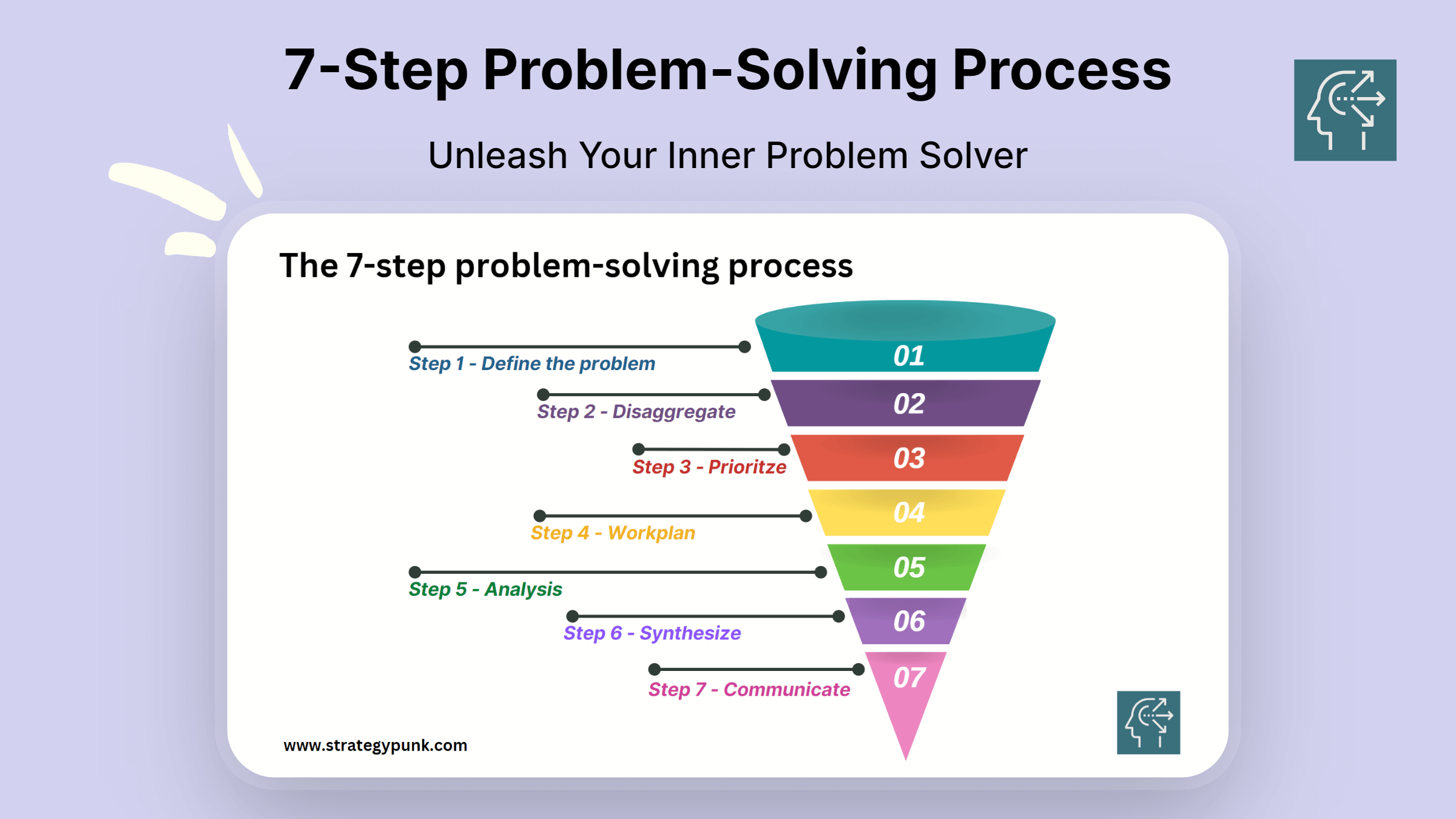

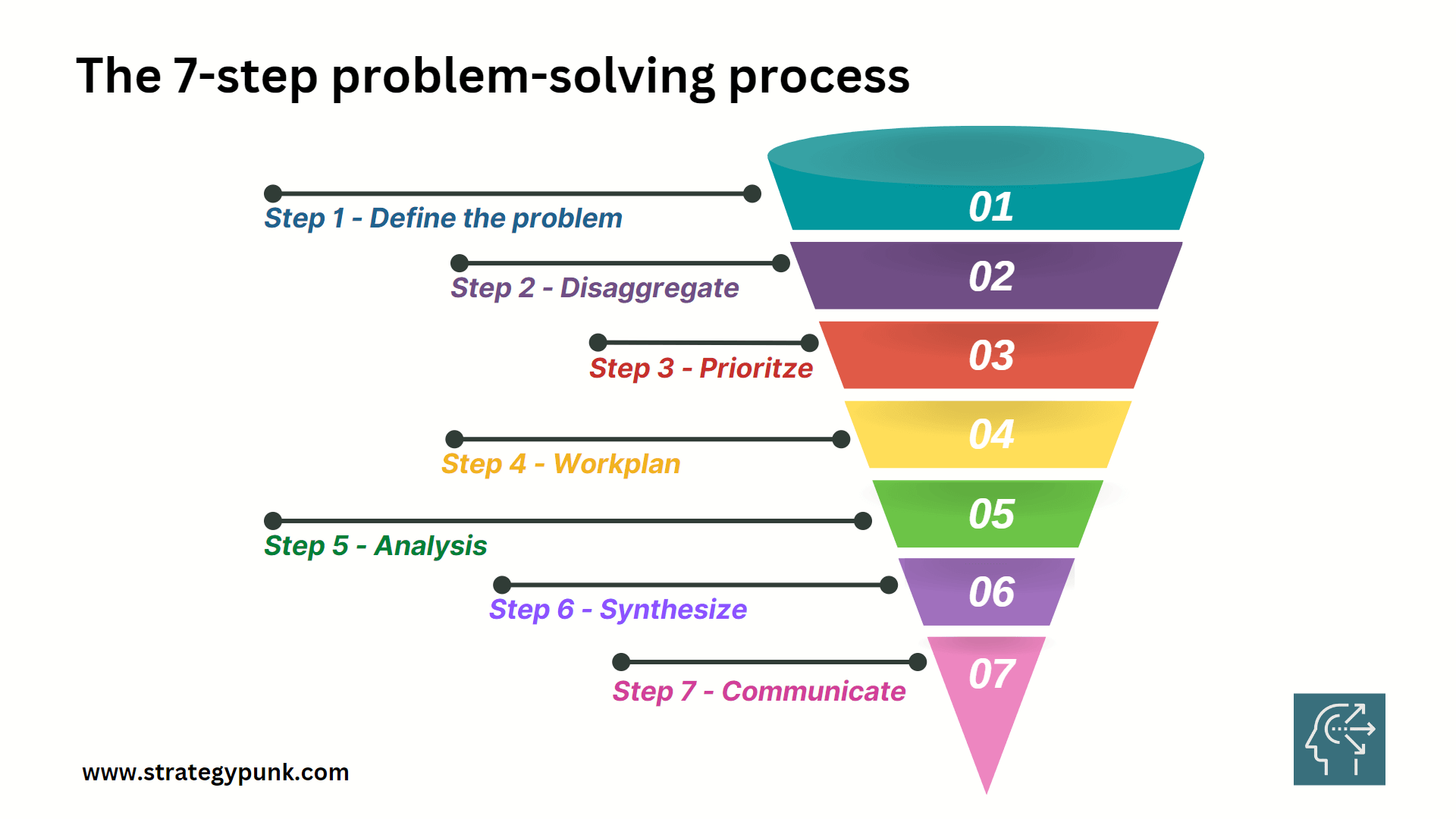

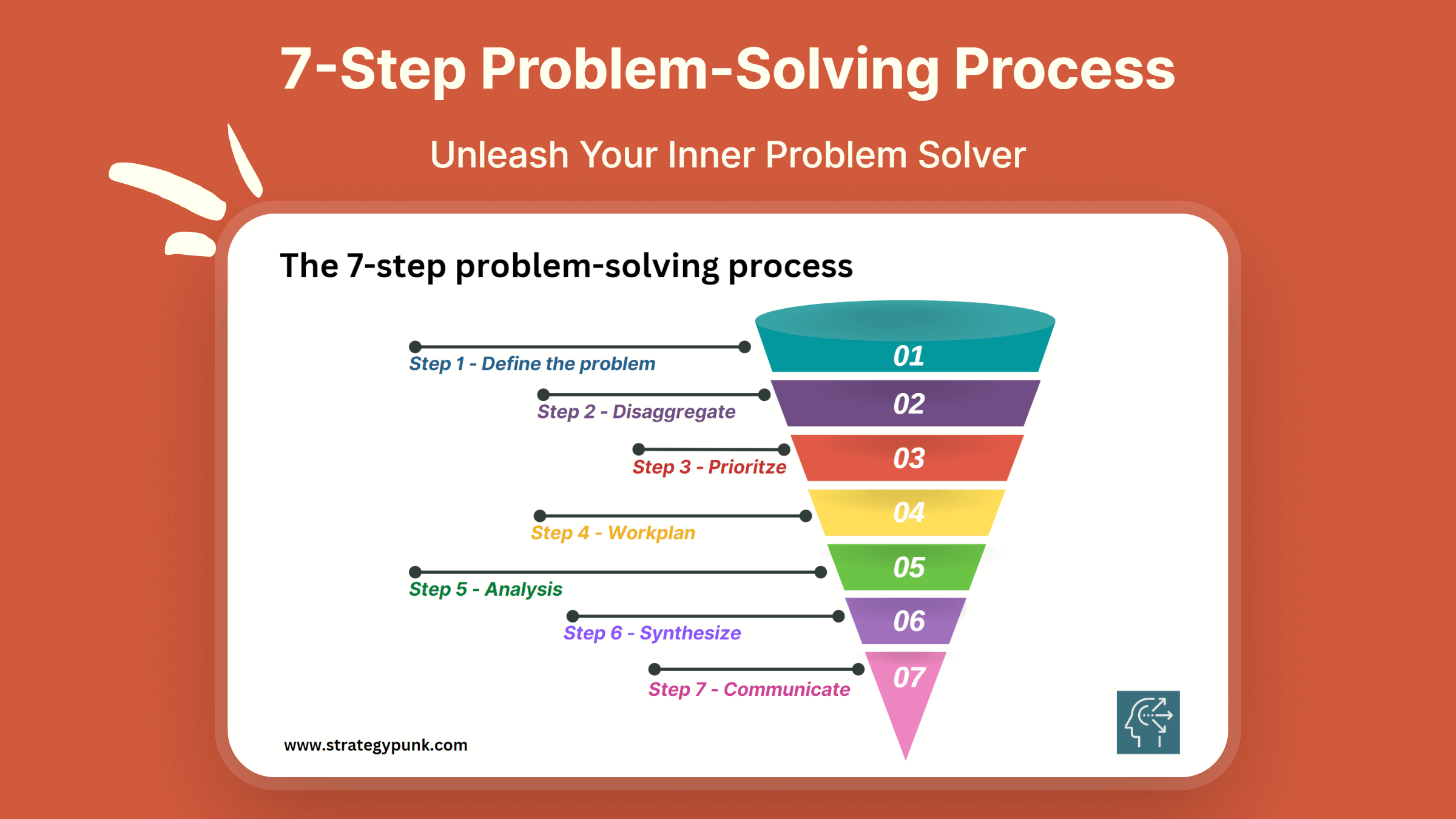

The 7-Step Problem-Solving Process involves steps that guide you through the problem-solving process. The first step is to define the problem, followed by disaggregating the problem into smaller, more manageable parts. Next, you prioritize the features and create a work plan to address each. Then, you analyze each piece, synthesize the information, and communicate your findings to others.

By following this process, you can avoid jumping to conclusions, overlooking important details, or making hasty decisions. Instead, you can approach problems with a clear and structured mindset, which can help you make better decisions and achieve better outcomes.

In this article, we'll explore each step of the 7-Step Problem-Solving Process in detail so you can start mastering this valuable skill. You can download the process's free PowerPoint and PDF templates at the end of the blog post .

Step 1: Define the Problem

The first step in the problem-solving process is to define the problem. This step is crucial because finding a solution is only accessible if the problem is clearly defined. The problem must be specific, measurable, and achievable.

One way to define the problem is to ask the right questions. Questions like "What is the problem?" and "What are the causes of the problem?" can help. Gathering data and information about the issue to assist in the definition process is also essential.

Another critical aspect of defining the problem is identifying the stakeholders. Who is affected by it? Who has a stake in finding a solution? Identifying the stakeholders can help ensure that the problem is defined in a way that considers the needs and concerns of all those affected by it.

Once the problem is defined, it is essential to communicate the definition to all stakeholders. This helps to ensure that everyone is on the same page and that there is a shared understanding of the problem.

Step 2: Disaggregate

After defining the problem, the next step in the 7-step problem-solving process is to disaggregate the problem into smaller, more manageable parts. Disaggregation helps break down the problem into smaller pieces that can be analyzed individually. This step is crucial in understanding the root cause of the problem and identifying the most effective solutions.

Disaggregation can be achieved by breaking down the problem into sub-problems, identifying the contributing factors, and analyzing the relationships between these factors. This step helps identify the most critical factors that must be addressed to solve the problem.

A tree or fishbone diagram is one effective way to disaggregate a problem. These diagrams help identify the different factors contributing to the problem and how they are related. Another way is to use a table to list the other factors contributing to the situation and their corresponding impact on the issue.

Disaggregation helps in breaking down complex problems into smaller, more manageable parts. It helps understand the relationships between different factors contributing to the problem and identify the most critical factors that must be addressed. By disaggregating the problem, decision-makers can focus on the most vital areas, leading to more effective solutions.

Step 3: Prioritize

After defining the problem and disaggregating it into smaller parts, the next step in the 7-step problem-solving process is prioritizing the issues that need addressing. Prioritizing helps to focus on the most pressing issues and allocate resources more effectively.

There are several ways to prioritize issues, including:

- Urgency: Prioritize issues based on their urgency. Problems that require immediate attention should be addressed first.

- Impact: Prioritize issues based on their impact on the organization or stakeholders. Problems with a high impact should be given priority.

- Resources: Prioritize issues based on the resources required to address them. Problems that require fewer resources should be dealt with first.

Considering their concerns and needs, it is important to involve stakeholders in the prioritization process. This can be done through surveys, focus groups, or other forms of engagement.

Once the issues have been prioritized, developing a plan of action to address them is essential. This involves identifying the resources required, setting timelines, and assigning responsibilities.

Prioritizing issues is a critical step in problem-solving. By focusing on the most pressing problems, organizations can allocate resources more effectively and make better decisions.

Step 4: Workplan

After defining the problem, disaggregating, and prioritizing the issues, the next step in the 7-step problem-solving process is to develop a work plan. This step involves creating a roadmap that outlines the steps needed to solve the problem.

The work plan should include a list of tasks, deadlines, and responsibilities for each team member involved in the problem-solving process. Assigning tasks based on each team member's strengths and expertise ensures the work is completed efficiently and effectively.

Creating a work plan can help keep the team on track and ensure everyone is working towards the same goal. It can also help to identify potential roadblocks or challenges that may arise during the problem-solving process and develop contingency plans to address them.

Several tools and techniques can be used to develop a work plan, including Gantt charts, flowcharts, and mind maps. These tools can help to visualize the steps needed to solve the problem and identify dependencies between tasks.

Developing a work plan is a critical step in the problem-solving process. It provides a clear roadmap for solving the problem and ensures everyone involved is aligned and working towards the same goal.

Step 5: Analysis

Once the problem has been defined and disaggregated, the next step is to analyze the information gathered. This step involves examining the data, identifying patterns, and determining the root cause of the problem.

Several methods can be used during the analysis phase, including:

- Root cause analysis

- Pareto analysis

- SWOT analysis

Root cause analysis is a popular method used to identify the underlying cause of a problem. This method involves asking a series of "why" questions to get to the root cause of the issue.

Pareto analysis is another method that can be used during the analysis phase. This method involves identifying the 20% of causes responsible for 80% of the problems. By focusing on these critical causes, organizations can make significant improvements.

Finally, SWOT analysis is a valuable tool for analyzing the internal and external factors that may impact the problem. This method involves identifying the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats related to the issue.

Overall, the analysis phase is critical for identifying the root cause of the problem and developing practical solutions. Organizations can gain a deeper understanding of the issue and make informed decisions by using a combination of methods.

Step 6: Synthesize

Once the analysis phase is complete, it is time to synthesize the information gathered to arrive at a solution. During this step, the focus is on identifying the most viable solution that addresses the problem. This involves examining and combining the analysis results for a clear and concise conclusion.

One way to synthesize the information is to use a decision matrix. This involves creating a table that lists the potential solutions and the essential criteria for making a decision. Each answer is then rated against each standard, and the scores are tallied to arrive at a final decision.

Another approach to synthesizing the information is to use a mind map. This involves creating a visual representation of the problem and the potential solutions. The mind map can identify the relationships between the different pieces of information and help prioritize the solutions.

During the synthesis phase, remaining open-minded and considering all potential solutions is vital. To ensure everyone's perspectives are considered, it is also essential to involve all stakeholders in the decision-making process.

Step 7: Communicate

After synthesizing the information, the next step is communicating the findings to the relevant stakeholders. This is a crucial step because it helps to ensure that everyone is on the same page and that the decision-making process is transparent.

One effective way to communicate the findings is through a well-organized report. The report should include the problem statement, the analysis, the synthesis, and the recommended solution. It should be clear, concise, and easy to understand.

In addition to the report, a presentation explaining the findings is essential. The presentation should be tailored to the audience and highlight the report's key points. Visual aids such as tables, graphs, and charts can make the presentation more engaging.

During the presentation, it is essential to be open to feedback and questions from the audience. This helps ensure everyone agrees with the recommended solution and addresses concerns or objections.

Effective communication is vital to ensuring the decision-making process is successful. Stakeholders can make informed decisions and work towards a common goal by communicating the findings clearly and concisely.

The 7-step problem-solving process is a powerful tool for helping individuals and organizations make better decisions. By following these steps, individuals can identify the root cause of a problem, prioritize potential solutions, and develop a clear plan of action. This process can be applied to various scenarios, from personal challenges to complex business problems.

Through disaggregation, individuals can break down complex problems into smaller, more manageable parts. By prioritizing potential solutions, individuals can focus their efforts on the most impactful actions. The work step allows individuals to develop a clear action plan, while the analysis step provides a framework for evaluating possible solutions.

The synthesis step combines all the information gathered to develop a comprehensive solution. Finally, the communication step allows individuals to share their answers with others and gather feedback.

By mastering the 7-step problem-solving process, individuals can become more effective decision-makers and problem-solvers. This process can help individuals and organizations save time and resources while improving outcomes. With practice, individuals can develop the skills to apply this process to a wide range of scenarios and make better decisions in all areas of life.

7-Step Problem-Solving Process PPT Template

Free powerpoint and pdf template, executive summary: the 7-step problem-solving process.

The 7-Step Problem-Solving Process is a robust and systematic method to help individuals and organizations make better decisions by tackling complex issues and finding practical solutions. This process comprises defining the problem, disaggregating it into smaller parts, prioritizing the issues, creating a work plan, analyzing the data, synthesizing the information, and communicating the findings.

By following these steps, individuals can identify the root cause of a problem, break it down into manageable components, and prioritize the most impactful actions. The work plan, analysis, and synthesis steps provide a framework for developing comprehensive solutions, while the communication step ensures transparency and stakeholder engagement.

Mastering this process can improve decision-making and problem-solving capabilities, save time and resources, and improve outcomes in personal and professional contexts.

Please buy me a coffee.

I'd appreciate your support if my templates have saved you time or helped you start a project. Buy Me a Coffee is a simple way to show your appreciation and help me continue creating high-quality templates that meet your needs.

7-Step Problem-Solving Process PDF Template

7-step problem-solving process powerpoint template.

Xpeng SWOT Analysis: Free PPT Template and In-Depth Insights (free file)

Unlock key insights into Xpeng with our free SWOT analysis PPT template. Dive deep into its business dynamics at no cost.

Strategic Insights 2024: A SWOT Analysis of Nestle (Plus Free PPT)

Explore Nestle's strategic outlook with our SWOT analysis for 2024. This PowerPoint template highlights key areas for growth and challenges.

2024 Business Disruption: Navigating Growth Through Shaping Strategy

Discover the importance of being a shaper in 2023's business ecosystem. Shaping strategy, attracting a critical mass of participants, and finding the right strategic path to create value.

Samsung PESTLE Analysis: Unveiling the Driving Forces (Free PPT)

Download our comprehensive guide: Samsung PESTLE Analysis (Free PPT). Discover the strategic insights & driving forces shaping Samsung's future.

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

8 Steps in the Decision-Making Process

- 04 Feb 2020

Strong decision-making skills are essential for newly appointed and seasoned managers alike. The ability to navigate complex challenges and develop a plan can not only lead to more effective team management but drive key organizational change initiatives and objectives.

Despite decision-making’s importance in business, a recent survey by McKinsey shows that just 20 percent of professionals believe their organizations excel at it. Survey respondents noted that, on average, they spend 37 percent of their time making decisions, but more than half of it’s used ineffectively.

For managers, it’s critical to ensure effective decisions are made for their organizations’ success. Every managerial decision must be accompanied by research and data , collaboration, and alternative solutions.

Few managers, however, reap the benefits of making more thoughtful choices due to undeveloped decision-making models.

Access your free e-book today.

Why Is Making Decisions Important?

According to Harvard Business School Professor Leonard Schlesinger, who’s featured in the online course Management Essentials , most managers view decision-making as a single event, rather than a process. This can lead to managers overestimating their abilities to influence outcomes and closing themselves off from alternative perspectives and diverse ways of thinking.

“The reality is, it’s very rare to find a single point in time where ‘a decision of significance’ is made and things go forward from there,” Schlesinger says. “Embedded in this work is the notion that what we’re really talking about is a process. The role of the manager in managing that process is actually quite straightforward, yet, at the same time, extraordinarily complex.”

If you want to further your business knowledge and be more effective in your role, it’s critical to become a strong decision-maker. Here are eight steps in the decision-making process you can employ to become a better manager and have greater influence in your organization.

Steps in the Decision-Making Process

1. frame the decision.

Pinpointing the issue is the first step to initiating the decision-making process. Ensure the problem is carefully analyzed, clearly defined, and everyone involved in the outcome agrees on what needs to be solved. This process will give your team peace of mind that each key decision is based on extensive research and collaboration.

Schlesinger says this initial action can be challenging for managers because an ill-formed question can result in a process that produces the wrong decision.

“The real issue for a manager at the start is to make sure they are actively working to shape the question they’re trying to address and the decision they’re trying to have made,” Schlesinger says. “That’s not a trivial task.”

2. Structure Your Team

Managers must assemble the right people to navigate the decision-making process.

“The issue of who’s going to be involved in helping you to make that decision is one of the most central issues you face,” Schlesinger says. “The primary issue being the membership of the collection of individuals or group that you’re bringing together to make that decision.”

As you build your team, Schlesinger advises mapping the technical, political, and cultural underpinnings of the decision that needs to be made and gathering colleagues with an array of skills and experience levels to help you make an informed decision. .

“You want some newcomers who are going to provide a different point of view and perspective on the issue you’re dealing with,” he says. “At the same time, you want people who have profound knowledge and deep experience with the problem.”

It’s key to assign decision tasks to colleagues and invite perspectives that uncover blindspots or roadblocks. Schlesinger notes that attempting to arrive at the “right answer” without a team that will ultimately support and execute it is a “recipe for failure.”

3. Consider the Timeframe

This act of mapping the issue’s intricacies should involve taking the decision’s urgency into account. Business problems with significant implications sometimes allow for lengthier decision-making processes, whereas other challenges call for more accelerated timelines.

“As a manager, you need to shape the decision-making process in terms of both of those dimensions: The criticality of what it is you’re trying to decide and, more importantly, how quickly it needs to get decided given the urgency,” Schlesinger says. “The final question is, how much time you’re going to provide yourself and the group to invest in both problem diagnosis and decisions.”

4. Establish Your Approach

In the early stages of the decision-making process, it’s critical to set ground rules and assign roles to team members. Doing so can help ensure everyone understands how they contribute to problem-solving and agrees on how a solution will be reached.

“It’s really important to get clarity upfront around the roles people are going to play and the ways in which decisions are going to get made,” Schlesinger says. “Often, managers leave that to chance, so people self-assign themselves to roles in ways that you don’t necessarily want, and the decision-making process defers to consensus, which is likely to lead to a lower evaluation of the problem and a less creative solution.”

5. Encourage Discussion and Debate

One of the issues of leading a group that defaults to consensus is that it can shut out contrarian points of view and deter inventive problem-solving. Because of this potential pitfall, Schlesinger notes, you should designate roles that focus on poking holes in arguments and fostering debate.

“What we’re talking about is establishing a process of devil’s advocacy, either in an individual or a subgroup role,” he says. “That’s much more likely to lead to a deeper critical evaluation and generate a substantial number of alternatives.”

Schlesinger adds that this action can take time and potentially disrupt group harmony, so it’s vital for managers to guide the inner workings of the process from the outset to ensure effective collaboration and guarantee more quality decisions will be made.

“What we need to do is establish norms in the group that enable us to be open to a broader array of data and decision-making processes,” he says. “If that doesn’t happen upfront, but in the process without a conversation, it’s generally a source of consternation and some measure of frustration.”

Related: 3 Group Decision-Making Techniques for Success

6. Navigate Group Dynamics

In addition to creating a dynamic in which candor and debate are encouraged, there are other challenges you need to navigate as you manage your team throughout the decision-making process.

One is ensuring the size of the group is appropriate for the problem and allows for an efficient workflow.

“In getting all the people together that have relevant data and represent various political and cultural constituencies, each incremental member adds to the complexity of the decision-making process and the amount of time it takes to get a decision made and implemented,” Schlesinger says.

Another task, he notes, is identifying which parts of the process can be completed without face-to-face interaction.

“There’s no question that pieces of the decision-making process can be deferred to paper, email, or some app,” Schlesinger says. “But, at the end of the day, given that so much of decision-making requires high-quality human interaction, you need to defer some part of the process for ill-structured and difficult tasks to a face-to-face meeting.”

7. Ensure the Pieces Are in Place for Implementation

Throughout your team’s efforts to arrive at a decision, you must ensure you facilitate a process that encompasses:

- Shared goals that were presented upfront

- Alternative options that have been given rigorous thought and fair consideration

- Sound methods for exploring decisions’ consequences

According to Schlesinger, these components profoundly influence the quality of the solution that’s ultimately identified and the types of decisions that’ll be made in the future.

“In the general manager’s job, the quality of the decision is only one part of the equation,” he says. “All of this is oriented toward trying to make sure that once a decision is made, we have the right groupings and the right support to implement.”

8. Achieve Closure and Alignment

Achieving closure in the decision-making process requires arriving at a solution that sufficiently aligns members of your group and garners enough support to implement it.

As with the other phases of decision-making, clear communication ensures your team understands and commits to the plan.

In a video interview for the online course Management Essentials , Harvard Business School Dean Nitin Nohria says it’s essential to explain the rationale behind the decision to your employees.

“If it’s a decision that you have to make, say, ‘I know there were some of you who thought differently, but let me tell you why we went this way,’” Nohria says. “This is so the people on the other side feel heard and recognize the concerns they raised are things you’ve tried to incorporate into the decision and, as implementation proceeds, if those concerns become real, then they’ll be attended to.”

How to Improve Your Decision-Making

An in-depth understanding of the decision-making process is vital for all managers. Whether you’re an aspiring manager aiming to move up at your organization or a seasoned executive who wants to boost your job performance, honing your approach to decision-making can improve your managerial skills and equip you with the tools to advance your career.

Do you want to become a more effective decision-maker? Explore Management Essentials —one of our online leadership and management courses —to learn how you can influence the context and environment in which decisions get made.

This article was update on July 15, 2022. It was originally published on February 4, 2020.

About the Author

.webp)

Problem Solving and Decision Making - Two Essential Skills of a Good Leader

.webp)

Problem solving and decision making are two fascinating skillsets. We call them out as two separate skills – and they are – but they also make use of the same core attributes.

They feed on a need to communicate well, both through questioning and listening, and be patient and not rushing both processes through. Thus, the greatest challenge any leader faces when it comes to solving problems and decision making is when the pressure of time comes into play. But as Robert Schuller highlights in his quote, allowing problem-solving to become the decision means you’ll never break free from the problem.

“Never bring the problem-solving stage into the decision-making stage. Otherwise, you surrender yourself to the problem rather than the solution.”—Robert H. Schuller

So how does a leader avoid this trap? How do they ensure the problem solving doesn’t become the be-all and end-all?

The 7 steps of Effective Problem Solving and Decision Making

A vital hurdle every leader must overcome is to avoid the impulsive urge to make quick decisions . Often when confronted with a problem, leaders or managers fall back in past behaviours. Urgency creates pressure to act quickly as a result, the problem still exists, just side-lined until it rears its ugly head again.

Good problem solving opens opportunity. A notable example of this is the first principles thinking executed by the likes of Elon Musk and others. Understanding the fundamentals blocks of a process and the problem it’s creating can lead to not just the problem but accelerate beyond it.

So, to avoid the trap, and use problem solving and decision making effectively , you should embody yourself with the following seven steps.

1. What is the problem?

Often, especially in time-critical situations, people don’t define the problem. Some label themselves as fire-fighters, just content with dowsing out the flames. It is a reactionary behaviour and one commonplace with under-trained leaders. As great as some fire-fighters are, they can only put out so many fires at one time, often becoming a little industry.

The better approach is to define the problem, and this means asking the following questions:

- What is happening? ( What makes you think there is a problem?)

- Where is it taking place?

- How is it happening?

- When is it happening?

- Why is it happening?

- With whom is it happening? (This isn’t a blame game…all you want to do is isolate the problem to a granular level.)

- Define what you understand to be the problem in writing by using as few sentences as possible. (Look at the answers to your what, where, why, when, and how questions.)

2. What are the potential causes?

Having defined the problem it is now time to find out what might be causing the problem. Your leadership skills: your communication skills need to be strong, as you look to gather input from your team and those involved in the problem.

Key points:

- Talk to those involved individually. Groupthink is a common cause of blindness to the problem, especially if there is blame culture within the business.

- Document what you’ve heard and what you think is the root cause is.

- Be inquisitive. You don’t know what you don’t know, so get the input of others and open yourself up to the feedback you’ll need to solve this problem.

3. What other ways can you overcome the problem?

Sometimes, getting to the root cause can take time. Of course, you can’t ignore it, but it is important to produce a plan to temporarily fix the problem. In business, a problem will be costing the business money, whether it be sales or profit. So, a temporary fix allows the business to move forward, providing it neutralises the downside of the original problem.

4. How will you resolve the problem?

At this stage, you still don’t know what the actual problem is. All you have is a definition of the problem which is a diagnosis of the issue. You will have the team’s input, as well as your opinions as to what the next steps should be.

If you don’t, then at this stage you should think about reassessing the problem. One way forward could be to become more granular and adopt a first-principles approach.

- Break the problem down into its core parts

- What forms the foundational blocks of the system in operation?

- Ask powerful questions to get to the truth of the problem

- How do the parts fit together?

- What was the original purpose of the system working in this way?

- Name and separate your assumptions from the facts

- Remind yourself of the goal and create a new solution

Solve hard problems with inversion

Another way is to invert the problem using the following technique:

1. Understand the problem

Every solution starts with developing a clear understanding of what the problem is. In this instance, some clarity of the issue is vital.

2. Ask the opposite question

Convention wisdom means we see the world logically. But what if you turned the logical outcome on its head. Asking the opposite questions brings an unfamiliar perspective.

3. Answer the opposite question

It seems a simple logic, but you can’t just ask the opposite question and not answer it. You must think through the dynamics that come from asking the question. You're looking for alternative viewpoints and thoughts you've not had before.

4. Join your answers up with your original problem

This is where solutions are born. You’re taking your conventional wisdom and aligning it with the opposite perspective. So often the blockers seen in the original problem become part of the solution.

5. Define a plan to either fix the problem permanently or temporarily

You now know the problem. You understand the fix, and you are a position to assess the risks involved.

Assessing the risks means considering the worst-case scenarios and ensuring you avoid them. Your plan should take into the following points:

- Is there any downtime to implementing the solution? If so, how long, and how much will it cost? Do you have backup systems in place to minimise the impact?

- If the risk is too great, consider a temporary fix which keeps current operations in place and gives you time to further prepare for a permanent fix.

- Document the plan and share it with all the relevant stakeholders. Communication is key.

Here we see the two skills of problem solving and decision making coming together. The two skills are vital to managing business risks as well as solving the problem.

6. Monitor and measure the plan

Having evolved through the five steps to this stage, you mustn’t take your eye off the ball as it were.

- Define timelines and assess progress

- Report to the stakeholders, ensuring everyone is aware of progress or any delays.

- If the plan doesn’t deliver, ask why? Learn from failure.

7. Have you fixed the problem?

Don’t forget the problem you started with. Have you fixed it? You might find it wasn’t a problem at all. You will have learnt a lot about the part of the business where the problem occurred, and improvements will have taken place.

Use the opportunity to assess what worked, what didn’t, and what would have helped. These are three good questions to give you some perspective on the process you’ve undertaken.

Problem solving and decision making in unison

Throughout the process of problem solving, you’re making decisions. Right from the beginning when the problem first becomes clear, you have a choice to either react – firefight or to investigate. This progresses as move onto risk assessing the problem and then defining the solutions to overcome the issue.

Throughout the process, the critical element is to make decisions with the correct information to hand. Finding out the facts, as well as defeating your assumptions are all part of the process of making the right decision.

Problem solving and decision making – a process

Problem solving isn’t easy. It becomes even more challenging when you have decisions to make. The seven steps I’ve outlined will give you the ability to investigate and diagnose the problem correctly.

- What is the problem?

- What are the potential causes?

- What other ways can you overcome the problem?

- How will you resolve the problem?

- Define a plan to either fix the problem permanently or temporarily.

- Monitor and measure the plan.

- Have you fixed the problem?

Of course, this logical step by step process might not enable you to diagnose the issue at hand. Some problems can be extremely hard, and an alternative approach might help. In this instance, first principles thinking or using the power of inversion are excellent ways to dig into hard problems. Problem solving and decision making are two skills every good leader needs. Using them together is an effective way to work.

.webp)

Decision Growth Made Easy

Related articles.

.webp)

How Thinking Like a Detective Will Improve Your Decisions

How Thinking in Patterns Will Make You Think Better

.webp)

Fact-Based Decision Making: The Key to Making Progress as a Creator

.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:42px;color:#F5F4F3;}@media (max-width: 1120px){.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:12px;}} Join us: Learn how to build a trusted AI strategy to support your company's intelligent transformation, featuring Forrester .css-1ixh9fn{display:inline-block;}@media (max-width: 480px){.css-1ixh9fn{display:block;margin-top:12px;}} .css-1uaoevr-heading-6{font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-1uaoevr-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} .css-ora5nu-heading-6{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:start;-ms-flex-pack:start;-webkit-justify-content:flex-start;justify-content:flex-start;color:#0D0E10;-webkit-transition:all 0.3s;transition:all 0.3s;position:relative;font-size:16px;line-height:28px;padding:0;font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{border-bottom:0;color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover path{fill:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div{border-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div:before{border-left-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active{border-bottom:0;background-color:#EBE8E8;color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active path{fill:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div{border-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div:before{border-left-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} Register now .css-1k6cidy{width:11px;height:11px;margin-left:8px;}.css-1k6cidy path{fill:currentColor;}

- Leadership |

- 7 important steps in the decision makin ...

7 important steps in the decision making process

The decision making process is a method of gathering information, assessing alternatives, and making a final choice with the goal of making the best decision possible. In this article, we detail the step-by-step process on how to make a good decision and explain different decision making methodologies.

We make decisions every day. Take the bus to work or call a car? Chocolate or vanilla ice cream? Whole milk or two percent?

There's an entire process that goes into making those tiny decisions, and while these are simple, easy choices, how do we end up making more challenging decisions?

At work, decisions aren't as simple as choosing what kind of milk you want in your latte in the morning. That’s why understanding the decision making process is so important.

What is the decision making process?

The decision making process is the method of gathering information, assessing alternatives, and, ultimately, making a final choice.

Decision-making tools for agile businesses

In this ebook, learn how to equip employees to make better decisions—so your business can pivot, adapt, and tackle challenges more effectively than your competition.

The 7 steps of the decision making process

Step 1: identify the decision that needs to be made.

When you're identifying the decision, ask yourself a few questions:

What is the problem that needs to be solved?

What is the goal you plan to achieve by implementing this decision?

How will you measure success?

These questions are all common goal setting techniques that will ultimately help you come up with possible solutions. When the problem is clearly defined, you then have more information to come up with the best decision to solve the problem.

Step 2: Gather relevant information

Gathering information related to the decision being made is an important step to making an informed decision. Does your team have any historical data as it relates to this issue? Has anybody attempted to solve this problem before?

It's also important to look for information outside of your team or company. Effective decision making requires information from many different sources. Find external resources, whether it’s doing market research, working with a consultant, or talking with colleagues at a different company who have relevant experience. Gathering information helps your team identify different solutions to your problem.

Step 3: Identify alternative solutions

This step requires you to look for many different solutions for the problem at hand. Finding more than one possible alternative is important when it comes to business decision-making, because different stakeholders may have different needs depending on their role. For example, if a company is looking for a work management tool, the design team may have different needs than a development team. Choosing only one solution right off the bat might not be the right course of action.

Step 4: Weigh the evidence

This is when you take all of the different solutions you’ve come up with and analyze how they would address your initial problem. Your team begins identifying the pros and cons of each option, and eliminating alternatives from those choices.

There are a few common ways your team can analyze and weigh the evidence of options:

Pros and cons list

SWOT analysis

Decision matrix

Step 5: Choose among the alternatives

The next step is to make your final decision. Consider all of the information you've collected and how this decision may affect each stakeholder.

Sometimes the right decision is not one of the alternatives, but a blend of a few different alternatives. Effective decision-making involves creative problem solving and thinking out of the box, so don't limit you or your teams to clear-cut options.

One of the key values at Asana is to reject false tradeoffs. Choosing just one decision can mean losing benefits in others. If you can, try and find options that go beyond just the alternatives presented.

Step 6: Take action

Once the final decision maker gives the green light, it's time to put the solution into action. Take the time to create an implementation plan so that your team is on the same page for next steps. Then it’s time to put your plan into action and monitor progress to determine whether or not this decision was a good one.

Step 7: Review your decision and its impact (both good and bad)

Once you’ve made a decision, you can monitor the success metrics you outlined in step 1. This is how you determine whether or not this solution meets your team's criteria of success.

Here are a few questions to consider when reviewing your decision:

Did it solve the problem your team identified in step 1?

Did this decision impact your team in a positive or negative way?

Which stakeholders benefited from this decision? Which stakeholders were impacted negatively?

If this solution was not the best alternative, your team might benefit from using an iterative form of project management. This enables your team to quickly adapt to changes, and make the best decisions with the resources they have.

Types of decision making models

While most decision making models revolve around the same seven steps, here are a few different methodologies to help you make a good decision.

Rational decision making models

This type of decision making model is the most common type that you'll see. It's logical and sequential. The seven steps listed above are an example of the rational decision making model.

When your decision has a big impact on your team and you need to maximize outcomes, this is the type of decision making process you should use. It requires you to consider a wide range of viewpoints with little bias so you can make the best decision possible.

Intuitive decision making models

This type of decision making model is dictated not by information or data, but by gut instincts. This form of decision making requires previous experience and pattern recognition to form strong instincts.

This type of decision making is often made by decision makers who have a lot of experience with similar kinds of problems. They have already had proven success with the solution they're looking to implement.

Creative decision making model

The creative decision making model involves collecting information and insights about a problem and coming up with potential ideas for a solution, similar to the rational decision making model.

The difference here is that instead of identifying the pros and cons of each alternative, the decision maker enters a period in which they try not to actively think about the solution at all. The goal is to have their subconscious take over and lead them to the right decision, similar to the intuitive decision making model.

This situation is best used in an iterative process so that teams can test their solutions and adapt as things change.

Track key decisions with a work management tool

Tracking key decisions can be challenging when not documented correctly. Learn more about how a work management tool like Asana can help your team track key decisions, collaborate with teammates, and stay on top of progress all in one place.

Related resources

100+ teamwork quotes to motivate and inspire collaboration

Beat thrash for good: 4 organizational planning challenges and solutions

Work schedule types: How to find the right approach for your team

When to use collaboration vs. coordination

- Principles of Management

- Study Guides

- The Decision‐Making Process

- Functions of Managers

- Dispelling Common Management Myths

- Management and Organizations

- Behavioral Management Theory

- Quantitative School of Management

- Contingency School of Management

- Quality School of Management

- Management in the Future

- Classical Schools of Management

- Adapting to Environments

- Introduction to Managerial Environments

- The External Environment

- The Internal Environment

- Conditions that Influence Decison Making

- Personal Decison‐Making Styles

- Decision Making with Quantitative Tools

- Detailing Types of Plans

- Identifying Barriers to Planning

- Defining Planning

- Recognizing the Advantages of Planning

- Using Plans to Achieve Goals

- Concepts of Organizing

- The Informal Organization

- Going from Planning to Organizing

- The Organizational Process

- Bureaucracy Basics

- Factors Affecting Organizational Design

- Five Approaches to Organizational Design

- Organizational Design Defined

- Challenges of Organizational Change

- Diagnosing the Need for Change

- Steps in Planned Change

- Opposition to Organizational Changes

- Causes of Organizational Change

- Types of Organizational Change

- HR Management: Laws and Regulations

- Determining Human Resource Needs

- Selecting the Best Person for the Job

- Orientation and Training Programs

- Evaluating Employee Performance

- Making Employment Decisions

- Staffing as a Management Function

- Compensating Employees

- Effectiveness of Teams

- Team Building

- Stages of Team Development

- Managing Team Conflict

- Teamwork Defined

- Types of Teams

- Motivation Theories: Behavior

- Management Philosophies and Motivation

- Motivation Strategies

- Defining Motivation

- Motivation Theories: Individual Needs

- Challenges Facing Leaders

- Leadership Defined

- Situational Approaches to Leadership

- The Communication Process

- Methods of Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Organizational Communication

- Improving Communications

- The Significance of Communication

- Effective Organizational Control Systems

- Organizational Control Techniques

- Organizational Control Objectives

- The Organizational Control Process

- Types of Organizational Controls

- Major Contributors to TQM

- The Implementation of TQM

- World‐Class Quality: ISO 9000 Certification

- Productivity and Quality

- Total Quality Management (TQM)

- The International Environment

- Functions of the International Manager

- Personal Challenges for Global Managers

- The Multinational Corporation

Managers are constantly called upon to make decisions in order to solve problems. Decision making and problem solving are ongoing processes of evaluating situations or problems, considering alternatives, making choices, and following them up with the necessary actions. Sometimes the decision‐making process is extremely short, and mental reflection is essentially instantaneous. In other situations, the process can drag on for weeks or even months. The entire decision‐making process is dependent upon the right information being available to the right people at the right times.

The decision‐making process involves the following steps:

1.Define the problem.

2.Identify limiting factors.

3.Develop potential alternatives.

4.Analyze the alternatives. 5.Select the best alternative.

6.Implement the decision.

7.Establish a control and evaluation system.

Define the problem

The decision‐making process begins when a manager identifies the real problem. The accurate definition of the problem affects all the steps that follow; if the problem is inaccurately defined, every step in the decision‐making process will be based on an incorrect starting point. One way that a manager can help determine the true problem in a situation is by identifying the problem separately from its symptoms.

The most obviously troubling situations found in an organization can usually be identified as symptoms of underlying problems. (See Table for some examples of symptoms.) These symptoms all indicate that something is wrong with an organization, but they don't identify root causes. A successful manager doesn't just attack symptoms; he works to uncover the factors that cause these symptoms.

All managers want to make the best decisions. To do so, managers need to have the ideal resources — information, time, personnel, equipment, and supplies — and identify any limiting factors. Realistically, managers operate in an environment that normally doesn't provide ideal resources. For example, they may lack the proper budget or may not have the most accurate information or any extra time. So, they must choose to satisfice — to make the best decision possible with the information, resources, and time available.

Time pressures frequently cause a manager to move forward after considering only the first or most obvious answers. However, successful problem solving requires thorough examination of the challenge, and a quick answer may not result in a permanent solution. Thus, a manager should think through and investigate several alternative solutions to a single problem before making a quick decision.

One of the best known methods for developing alternatives is through brainstorming, where a group works together to generate ideas and alternative solutions. The assumption behind brainstorming is that the group dynamic stimulates thinking — one person's ideas, no matter how outrageous, can generate ideas from the others in the group. Ideally, this spawning of ideas is contagious, and before long, lots of suggestions and ideas flow. Brainstorming usually requires 30 minutes to an hour. The following specific rules should be followed during brainstorming sessions:

Concentrate on the problem at hand. This rule keeps the discussion very specific and avoids the group's tendency to address the events leading up to the current problem.

Entertain all ideas. In fact, the more ideas that come up, the better. In other words, there are no bad ideas. Encouragement of the group to freely offer all thoughts on the subject is important. Participants should be encouraged to present ideas no matter how ridiculous they seem, because such ideas may spark a creative thought on the part of someone else.

Refrain from allowing members to evaluate others' ideas on the spot. All judgments should be deferred until all thoughts are presented, and the group concurs on the best ideas.

Although brainstorming is the most common technique to develop alternative solutions, managers can use several other ways to help develop solutions. Here are some examples:

Nominal group technique. This method involves the use of a highly structured meeting, complete with an agenda, and restricts discussion or interpersonal communication during the decision‐making process. This technique is useful because it ensures that every group member has equal input in the decision‐making process. It also avoids some of the pitfalls, such as pressure to conform, group dominance, hostility, and conflict, that can plague a more interactive, spontaneous, unstructured forum such as brainstorming.

Delphi technique. With this technique, participants never meet, but a group leader uses written questionnaires to conduct the decision making.

No matter what technique is used, group decision making has clear advantages and disadvantages when compared with individual decision making. The following are among the advantages:

Groups provide a broader perspective.

Employees are more likely to be satisfied and to support the final decision.

Opportunities for discussion help to answer questions and reduce uncertainties for the decision makers.

These points are among the disadvantages:

This method can be more time‐consuming than one individual making the decision on his own.

The decision reached could be a compromise rather than the optimal solution.

Individuals become guilty of groupthink — the tendency of members of a group to conform to the prevailing opinions of the group.

Groups may have difficulty performing tasks because the group, rather than a single individual, makes the decision, resulting in confusion when it comes time to implement and evaluate the decision.

The results of dozens of individual‐versus‐group performance studies indicate that groups not only tend to make better decisions than a person acting alone, but also that groups tend to inspire star performers to even higher levels of productivity.

So, are two (or more) heads better than one? The answer depends on several factors, such as the nature of the task, the abilities of the group members, and the form of interaction. Because a manager often has a choice between making a decision independently or including others in the decision making, she needs to understand the advantages and disadvantages of group decision making.

The purpose of this step is to decide the relative merits of each idea. Managers must identify the advantages and disadvantages of each alternative solution before making a final decision.

Evaluating the alternatives can be done in numerous ways. Here are a few possibilities:

Determine the pros and cons of each alternative.

Perform a cost‐benefit analysis for each alternative.

Weight each factor important in the decision, ranking each alternative relative to its ability to meet each factor, and then multiply by a probability factor to provide a final value for each alternative.

Regardless of the method used, a manager needs to evaluate each alternative in terms of its

Feasibility — Can it be done?

Effectiveness — How well does it resolve the problem situation?

Consequences — What will be its costs (financial and nonfinancial) to the organization?

After a manager has analyzed all the alternatives, she must decide on the best one. The best alternative is the one that produces the most advantages and the fewest serious disadvantages. Sometimes, the selection process can be fairly straightforward, such as the alternative with the most pros and fewest cons. Other times, the optimal solution is a combination of several alternatives.

Sometimes, though, the best alternative may not be obvious. That's when a manager must decide which alternative is the most feasible and effective, coupled with which carries the lowest costs to the organization. (See the preceding section.) Probability estimates, where analysis of each alternative's chances of success takes place, often come into play at this point in the decision‐making process. In those cases, a manager simply selects the alternative with the highest probability of success.

Managers are paid to make decisions, but they are also paid to get results from these decisions. Positive results must follow decisions. Everyone involved with the decision must know his or her role in ensuring a successful outcome. To make certain that employees understand their roles, managers must thoughtfully devise programs, procedures, rules, or policies to help aid them in the problem‐solving process.

Ongoing actions need to be monitored. An evaluation system should provide feedback on how well the decision is being implemented, what the results are, and what adjustments are necessary to get the results that were intended when the solution was chosen.

In order for a manager to evaluate his decision, he needs to gather information to determine its effectiveness. Was the original problem resolved? If not, is he closer to the desired situation than he was at the beginning of the decision‐making process?

If a manager's plan hasn't resolved the problem, he needs to figure out what went wrong. A manager may accomplish this by asking the following questions:

Was the wrong alternative selected? If so, one of the other alternatives generated in the decision‐making process may be a wiser choice.

Was the correct alternative selected, but implemented improperly? If so, a manager should focus attention solely on the implementation step to ensure that the chosen alternative is implemented successfully.

Was the original problem identified incorrectly? If so, the decision‐making process needs to begin again, starting with a revised identification step.

Has the implemented alternative been given enough time to be successful? If not, a manager should give the process more time and re‐evaluate at a later date.

Previous Decision Making with Quantitative Tools

Next Detailing Types of Plans

Work Life is Atlassian’s flagship publication dedicated to unleashing the potential of every team through real-life advice, inspiring stories, and thoughtful perspectives from leaders around the world.

Contributing Writer

Work Futurist

Senior Quantitative Researcher, People Insights

Principal Writer

This is how effective teams navigate the decision-making process

Zero Magic 8 Balls required.

Get stories like this in your inbox

Flipping a coin. Throwing a dart at a board. Pulling a slip of paper out of a hat.

Sure, they’re all ways to make a choice. But they all hinge on random chance rather than analysis, reflection, and strategy — you know, the things you actually need to make the big, meaty decisions that have major impacts.

So, set down that Magic 8 Ball and back away slowly. Let’s walk through the standard framework for decision-making that will help you and your team pinpoint the problem, consider your options, and make your most informed selection. Here’s a closer look at each of the seven steps of the decision-making process, and how to approach each one.

Step 1: Identify the decision

Most of us are eager to tie on our superhero capes and jump into problem-solving mode — especially if our team is depending on a solution. But you can’t solve a problem until you have a full grasp on what it actually is .

This first step focuses on getting the lay of the land when it comes to your decision. What specific problem are you trying to solve? What goal are you trying to achieve?

How to do it:

- Use the 5 whys analysis to go beyond surface-level symptoms and understand the root cause of a problem.

- Try problem framing to dig deep on the ins and outs of whatever problem your team is fixing. The point is to define the problem, not solve it.

⚠️ Watch out for: Decision fatigue , which is the tendency to make worse decisions as a result of needing to make too many of them. Making choices is mentally taxing , which is why it’s helpful to pinpoint one decision at a time.

2. Gather information

Your team probably has a few hunches and best guesses, but those can lead to knee-jerk reactions. Take care to invest adequate time and research into your decision.

This step is when you build your case, so to speak. Collect relevant information — that could be data, customer stories, information about past projects, feedback, or whatever else seems pertinent. You’ll use that to make decisions that are informed, rather than impulsive.

- Host a team mindmapping session to freely explore ideas and make connections between them. It can help you identify what information will best support the process.

- Create a project poster to define your goals and also determine what information you already know and what you still need to find out.

⚠️ Watch out for: Information bias , or the tendency to seek out information even if it won’t impact your action. We have the tendency to think more information is always better, but pulling together a bunch of facts and insights that aren’t applicable may cloud your judgment rather than offer clarity.

3. Identify alternatives

Use divergent thinking to generate fresh ideas in your next brainstorm

Blame the popularity of the coin toss, but making a decision often feels like choosing between only two options. Do you want heads or tails? Door number one or door number two? In reality, your options aren’t usually so cut and dried. Take advantage of this opportunity to get creative and brainstorm all sorts of routes or solutions. There’s no need to box yourselves in.

- Use the Six Thinking Hats technique to explore the problem or goal from all sides: information, emotions and instinct, risks, benefits, and creativity. It can help you and your team break away from your typical roles or mindsets and think more freely.

- Try brainwriting so team members can write down their ideas independently before sharing with the group. Research shows that this quiet, lone thinking time can boost psychological safety and generate more creative suggestions .

⚠️ Watch out for: Groupthink , which is the tendency of a group to make non-optimal decisions in the interest of conformity. People don’t want to rock the boat, so they don’t speak up.

4. Consider the evidence

Armed with your list of alternatives, it’s time to take a closer look and determine which ones could be worth pursuing. You and your team should ask questions like “How will this solution address the problem or achieve the goal?” and “What are the pros and cons of this option?”

Be honest with your answers (and back them up with the information you already collected when you can). Remind the team that this isn’t about advocating for their own suggestions to “win” — it’s about whittling your options down to the best decision.

How to do it:

- Use a SWOT analysis to dig into the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the options you’re seriously considering.

- Run a project trade-off analysis to understand what constraints (such as time, scope, or cost) the team is most willing to compromise on if needed.

⚠️ Watch out for: Extinction by instinct , which is the urge to make a decision just to get it over with. You didn’t come this far to settle for a “good enough” option!

5. Choose among the alternatives

This is it — it’s the big moment when you and the team actually make the decision. You’ve identified all possible options, considered the supporting evidence, and are ready to choose how you’ll move forward.

However, bear in mind that there’s still a surprising amount of room for flexibility here. Maybe you’ll modify an alternative or combine a few suggested solutions together to land on the best fit for your problem and your team.

- Use the DACI framework (that stands for “driver, approver, contributor, informed”) to understand who ultimately has the final say in decisions. The decision-making process can be collaborative, but eventually someone needs to be empowered to make the final call.

- Try a simple voting method for decisions that are more democratized. You’ll simply tally your team’s votes and go with the majority.

⚠️ Watch out for: Analysis paralysis , which is when you overthink something to such a great degree that you feel overwhelmed and freeze when it’s time to actually make a choice.

6. Take action

Making a big decision takes a hefty amount of work, but it’s only the first part of the process — now you need to actually implement it.

It’s tempting to think that decisions will work themselves out once they’re made. But particularly in a team setting, it’s crucial to invest just as much thought and planning into communicating the decision and successfully rolling it out.

- Create a stakeholder communications plan to determine how you’ll keep various people — direct team members, company leaders, customers, or whoever else has an active interest in your decision — in the loop on your progress.

- Define the goals, signals, and measures of your decision so you’ll have an easier time aligning the team around the next steps and determining whether or not they’re successful.

⚠️Watch out for: Self-doubt, or the tendency to question whether or not you’re making the right move. While we’re hardwired for doubt , now isn’t the time to be a skeptic about your decision. You and the team have done the work, so trust the process.

7. Review your decision

9 retrospective techniques that won’t bore your team to tears.

As the decision itself starts to shake out, it’s time to take a look in the rearview mirror and reflect on how things went.

Did your decision work out the way you and the team hoped? What happened? Examine both the good and the bad. What should you keep in mind if and when you need to make this sort of decision again?

- Do a 4 L’s retrospective to talk through what you and the team loved, loathed, learned, and longed for as a result of that decision.

- Celebrate any wins (yes, even the small ones ) related to that decision. It gives morale a good kick in the pants and can also help make future decisions feel a little less intimidating.

⚠️ Watch out for: Hindsight bias , or the tendency to look back on events with the knowledge you have now and beat yourself up for not knowing better at the time. Even with careful thought and planning, some decisions don’t work out — but you can only operate with the information you have at the time.

Making smart decisions about the decision-making process

You’re probably picking up on the fact that the decision-making process is fairly comprehensive. And the truth is that the model is likely overkill for the small and inconsequential decisions you or your team members need to make.

Deciding whether you should order tacos or sandwiches for your team offsite doesn’t warrant this much discussion and elbow grease. But figuring out which major project to prioritize next? That requires some careful and collaborative thought.

It all comes back to the concept of satisficing versus maximizing , which are two different perspectives on decision making. Here’s the gist:

- Maximizers aim to get the very best out of every single decision.

- Satisficers are willing to settle for “good enough” rather than obsessing over achieving the best outcome.

One of those isn’t necessarily better than the other — and, in fact, they both have their time and place.

A major decision with far-reaching impacts deserves some fixation and perfectionism. However, hemming and hawing over trivial choices ( “Should we start our team meeting with casual small talk or a structured icebreaker?” ) will only cause added stress, frustration, and slowdowns.

As with anything else, it’s worth thinking about the potential impacts to determine just how much deliberation and precision a decision actually requires.

Decision-making is one of those things that’s part art and part science. You’ll likely have some gut feelings and instincts that are worth taking into account. But those should also be complemented with plenty of evidence, evaluation, and collaboration.

The decision-making process is a framework that helps you strike that balance. Follow the seven steps and you and your team can feel confident in the decisions you make — while leaving the darts and coins where they belong.

Advice, stories, and expertise about work life today.

- Media Center

Decision-making process

The basic idea, theory, meet practice.

TDL is an applied research consultancy. In our work, we leverage the insights of diverse fields—from psychology and economics to machine learning and behavioral data science—to sculpt targeted solutions to nuanced problems.

Which do you prefer, hamburgers or pizza?

You probably came up with the answer to that question quickly — unless you’re really torn between those two delicious meals. Yet, whenever we are making a choice between two or more things, our brains go through a decision-making process.

When we are presented with a choice, we first have to identify the decision. For the hamburger vs. pizza question, that’s an easy step — you immediately know that the decision is between two food items. Next, we have to gather the relevant information. You think of hamburgers and pizzas and their respective tastes. Then, you identify alternatives. Are there any other options? Maybe a secret taco stash laying around? No.

Now that you know the parameters of the decision, it’s time to weigh the evidence. Since it’s based on personal preference, you only have to conjure up your own experience eating both. Which one have you preferred in the past? And finally: you’re ready to make the choice. 1

If the question was to require an action, such as “Do you want to go get hamburgers or pizza?”, after making the choice, you would implement the action and order one or the other. The last step is to reflect on that decision. As you sit thedown with your slice of pizza, are you content? You evaluate your outcome so that in the future, you can improve your choices. 2

A decision-making process is the cognitive process where you weigh alternatives to achieve a desired result. 3

It doesn’t matter which side of the fence you get off on sometimes. What matters most is getting off. You cannot make progress without making decisions. - American entrepreneur and motivational speaker Jim Rohn. 4

Problem Solving: while problem solving and decision making are related, they are not the same. Problem solving is an analytical process used to identify the possible solutions to a situation at hand and is sometimes a part of the decision-making process. However, sometimes you make a decision without identifying all possible solutions to the problem. 5

Analysis Paralysis: the inability to decide because of over-thinking. People usually get stuck in the stage where they consider all the alternatives and can be overwhelmed by choice (known as the choice overload bias ), preventing them from picking a choice. 6

Boundary conditions: constraints necessary for the solution of a decision. 7 The boundary conditions determine what the objective of the decision is and therefore what solutions will be suitable. 8

Maximizing: a decision-making process in which an individual employs optimization, where they gain all the necessary data on alternatives to make the best decision. 9

Bounded rationality : decision-making processes where individuals satisfice instead of optimize.

Decision-making processes are one of the facets that make humans unique. There are definitely similarities between the ways that humans and animals make decisions (in fact, we wrote a whole article about it: “ Decision-Making Parallels Between Humans and Animals ”). But humans are thought to engage in more complex decision-making processes - our actions are less governed by instinct than animals.

Since decision-making processes are an integral part of humanity, it’s impossible to pinpoint a time where they were first an object of research, as we have been interested in how humans make decisions as long as we have existed! In research, decision-making processes are usually examined as either group decision-making, or individual decision-making.

In group decision-making, multiple individuals work together to analyze a question or problem, consider alternative choices, and make a choice. An obvious difference between group decision-making and individual decision-making is that the former process is usually more formal and occurs outside of internal thought processes. Being in a group also has quite impactful effects on the types of decisions we come to. For example, groupthink is a phenomenon borne from our desire to achieve consensus - individuals ignore evidence or neglect to speak out if their thoughts contradict the majority opinion. It is a form of group conformity that hinders critical thinking and can lead to suboptimal decisions. Additionally, groups tend to make riskier decisions than individuals. 10

Yet, sometimes group decision-making processes are advantageous because there are a greater number of perspectives which can reduce the personal biases that come into play with individual decision-making. Groups can usually come up with a greater number of alternatives, because they have more time and resources. Oftentimes, individuals have to employ the satisficing technique, where they make a choice that is satisfactory rather than optimal. When satisficing, individuals don’t engage in problem-solving, but pick the first choice they come across that adheres to the boundary conditions, because it requires too much time, effort, and resources to gather all the necessary evidence and alternative options.

Various research has gone into trying to outline the steps involved in the decision-making process. One of the earlier processes,developed by Australian psychologist Leon Mann in the 1980s, is known as the GOFER process. It was based on a theory Mann had previously proposed alongside psychologist Irvin Janis, the conflict theory of decision making, which suggests decision-makers must choose from a set of alternatives that each have positive and negative outcomes. 11 GOFER represents an acronym for five decision-making steps:

- G oal clarification. In this step, the decision-maker must determine what their goal is and what they are trying to achieve with their decision.

- O ptions generation. The decision-maker conjures up different options that are available to them and that would help them achieve their goals.

- F acts-finding. During this stage, the decision-maker examines what evidence they have on each alternative and what information they are missing that could help them make their decision.

- E ffects. The decision-maker considers the positive and negative outcomes of each alternative.

- R eview. Now that a decision has been arrived at, the decision-maker considers how it will be implemented. 12

Another popular decision-making process model is the DECIDE model, developed in 2008 by Hawaiian educator, Kristina Guo. It has similar steps as the GOFER model and Guo developed it to help healthcare managers make better decisions. The acronym stands for:

- D efine the problem.

- E stablish the criteria.

- C onsider the alternatives.

- I dentify the best alternative.

- D evelop a plan and implement the plan of action.

- E valuate and monitor the solution and feedback. 10

While the first five steps are similar to the GOFER model, the DECIDE model has an additional step, evaluate, which is crucial for improving decision-making processes in the long run, as evaluating your choice will help you learn how successful it was and whether you should make the same decision in the future.

Consequences

Although we usually make decisions quickly, following decision-making models can help us make thoughtful decisions. By outlining the decision-making process, you can ensure that you are going through each step, considering the alternatives, and making an informed decision, which should lead to better outcomes. When it comes to group settings, being transparent about the decision-making process can also help other people understand why you’re making the choices you are. After all, wasn’t it irritating when your parents told you that the answer was no ‘because they said so’?

Controversies

Oftentimes, people assume that decision-making processes are rational. Many models assume that individuals will make choices that maximize utility while minimizing costs. They also assume people have all of the information required to make the optimal choice — all of the models include a stage where the decision-maker analyzes various alternatives.

But consider how many decisions you have made today. Is it really possible to go through each stage of the decision-making process, weigh out all the advantages and disadvantages of each alternative, and then come to a clear decision? Humans are thought to make around 35,000 choices per day, which makes it impossible for us to have the time, resources, or brain capacity to have all the information necessary to make a perfectly rational decision. 13

That’s why many people criticize decision-making models for being unrealistic, and instead suggest that decision-making processes actually adhere to bounded rationality , where decision-makers satisfice instead of optimize.

Effectiveness of the GOFER Decision-Making Process

Giving teens the tools to make better, more thought-out decisions can help improve outcomes. In 1988, Leon Mann and his colleagues from The Flinders University of South Australia conducted a study to determine how effective teaching students the GOFER decision-making process was. 14

Mann and his colleagues developed and ran a GOFER course to teach teens generalized decision-making skills that would enable the students to apply the decision skills to a range of problems even beyond the school context. They delivered the course over the span of a year with the aid of two principal texts. The first book outlined decision-making processes and the GOFER technique, while the second applied the principles of GOFER to five areas: decision-making in groups, friendships and decision-making, subject choices, money, and finally, the GOFER technique employed in various different professions. 14

Mann et al. compared the students in South Australia who had taken the GOFER course with a control group of high school students who had not taken the course. They gave all students a questionnaire that asked them to reflect on their decision self-esteem, their vigilance with decisions, panic measures they might be prone to, cop out tendencies they use to avoid making decisions, and complacency. They filled out another questionnaire that examined their performance on decision-making across the five areas taught by the course, and a third questionnaire that asked them general information about decision-making, with questions like, “What makes a good decision maker?” 14