3.3 Effective Reading Strategies

Questions to Consider:

- What methods can you incorporate into your routine to allow adequate time for reading?

- What are the benefits and approaches to active and critical reading?

- Do your courses or major have specific reading requirements?

Allowing Adequate Time for Reading

You should determine the reading requirements and expectations for every class very early in the semester. You also need to understand why you are reading the particular text you are assigned. Do you need to read closely for minute details that determine cause and effect? Or is your instructor asking you to skim several sources so you become more familiar with the topic? Knowing this reasoning will help you decide your timing, what notes to take, and how best to undertake the reading assignment.

Depending on the makeup of your schedule, you may end up reading both primary sources—such as legal documents, historic letters, or diaries—as well as textbooks, articles, and secondary sources, such as summaries or argumentative essays that use primary sources to stake a claim. You may also need to read current journalistic texts to stay up to date in local or global affairs. A realistic approach to scheduling your time to allow you to read and review all the reading you have for the semester will help you accomplish what can sometimes seem like an overwhelming task.

When you allow adequate time in your hectic schedule for reading, you are investing in your own success. Reading isn’t a magic pill, but it may seem like it when you consider all the benefits people reap from this ordinary practice. Famous successful people throughout history have been voracious readers. In fact, former U.S. president Harry Truman once said, “Not all readers are leaders, but all leaders are readers.” Writer of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, inventor, and also former U.S. president Thomas Jefferson claimed “I cannot live without books” at a time when keeping and reading books was an expensive pastime. Knowing what it meant to be kept from the joys of reading, 19th-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass said, “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” And finally, George R. R. Martin, the prolific author of the wildly successful Game of Thrones empire, declared, “A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies . . . The man who never reads lives only one.”

You can make time for reading in a number of ways that include determining your usual reading pace and speed, scheduling active reading sessions, and practicing recursive reading strategies.

Determining Reading Speed and Pacing

To determine your reading speed, select a section of text—passages in a textbook or pages in a novel. Time yourself reading that material for exactly 5 minutes, and note how much reading you accomplished in those 5 minutes. Multiply the amount of reading you accomplished in 5 minutes by 12 to determine your average reading pace (5 times 12 equals the 60 minutes of an hour). Of course, your reading pace will be different and take longer if you are taking notes while you read, but this calculation of reading pace gives you a good way to estimate your reading speed that you can adapt to other forms of reading.

In the table above, you can see three students with different reading speeds. So, for instance, if Marta was able to read 4 pages of a dense novel for her English class in 5 minutes, she should be able to read about 48 pages in one hour. Knowing this, Marta can accurately determine how much time she needs to devote to finishing the novel within a set amount of time, instead of just guessing. If the novel Marta is reading is 497 pages, then Marta would take the total page count (497) and divide that by her hourly reading rate (48 pages/hour) to determine that she needs about 10 to 11 hours overall. To finish the novel spread out over two weeks, Marta needs to read a little under an hour a day to accomplish this goal.

Calculating your reading rate in this manner does not take into account days where you’re too distracted and you have to reread passages or days when you just aren’t in the mood to read. And your reading rate will likely vary depending on how dense the content you’re reading is (e.g., a complex textbook vs. a comic book). Your pace may slow down somewhat if you are not very interested in what the text is about. What this method will help you do is be realistic about your reading time as opposed to waging a guess based on nothing and then becoming worried when you have far more reading to finish than the time available.

Chapter 2 , “ Managing Your Time and Priorities ,” offers more detail on how best to determine your speed from one type of reading to the next so you are better able to schedule your reading.

Scheduling Set Times for Active Reading

Active reading takes longer than reading through passages without stopping. You may not need to read your latest sci-fi series actively while you’re lounging on the beach, but many other reading situations demand more attention from you. Active reading is particularly important for college courses. You are a scholar actively engaging with the text by posing questions, seeking answers, and clarifying any confusing elements. Plan to spend at least twice as long to read actively than to read passages without taking notes or otherwise marking select elements of the text.

To determine the time you need for active reading, use the same calculations you use to determine your traditional reading speed and double it. Remember that you need to determine your reading pace for all the classes you have in a particular semester and multiply your speed by the number of classes you have that require different types of reading. The table below shows the differences in time needed between reading quickly without taking notes and reading actively.

Practicing Recursive Reading Strategies

One fact about reading for college courses that may become frustrating is that, in a way, it never ends. For all the reading you do, you end up doing even more rereading. It may be the same content, but you may be reading the passage more than once to detect the emphasis the writer places on one aspect of the topic or how frequently the writer dismisses a significant counterargument. This rereading is called recursive reading.

For most of what you read at the college level, you are trying to make sense of the text for a specific purpose—not just because the topic interests or entertains you. You need your full attention to decipher everything that’s going on in complex reading material—and you even need to be considering what the writer of the piece may not be including and why. This is why reading for comprehension is recursive.

Specifically, this boils down to seeing reading not as a formula but as a process that is far more circular than linear. You may read a selection from beginning to end, which is an excellent starting point, but for comprehension, you’ll need to go back and reread passages to determine meaning and make connections between the reading and the bigger learning environment that led you to the selection—that may be a single course or a program in your college, or it may be the larger discipline, such as all biologists or the community of scholars studying beach erosion.

People often say writing is rewriting. For college courses, reading is rereading, but rereading with the intention of improving comprehension and taking notes.

Strong readers engage in numerous steps, sometimes combining more than one step simultaneously, but knowing the steps nonetheless. They include, not always in this order:

- bringing any prior knowledge about the topic to the reading session,

- asking yourself pertinent questions, both orally and in writing, about the content you are reading,

- inferring and/or implying information from what you read,

- learning unfamiliar discipline-specific terms,

- evaluating what you are reading, and eventually,

- applying what you’re reading to other learning and life situations you encounter.

Let’s break these steps into manageable chunks, because you are actually doing quite a lot when you read.

Accessing Prior Knowledge

When you read, you naturally think of anything else you may know about the topic, but when you read deliberately and actively, you make yourself more aware of accessing this prior knowledge. Have you ever watched a documentary about this topic? Did you study some aspect of it in another class? Do you have a hobby that is somehow connected to this material? All of this thinking will help you make sense of what you are reading.

Application

Imagine that you were given a chapter to read in your American history class about the Gettysburg Address, now write down what you already know about this historic document. How might thinking through this prior knowledge help you better understand the text?

Asking Questions

Humans are naturally curious beings. As you read actively, you should be asking questions about the topic you are reading. Don’t just say the questions in your mind; write them down. You may ask: Why is this topic important? What is the relevance of this topic currently? Was this topic important a long time ago but irrelevant now? Why did my professor assign this reading?

You need a place where you can actually write down these questions; a separate page in your notes is a good place to begin. If you are taking notes on your computer, start a new document and write down the questions. Leave some room to answer the questions when you begin and again after you read.

Inferring and Implying

When you read, you can take the information on the page and infer , or conclude responses to related challenges from evidence or from your own reasoning. A student will likely be able to infer what material the professor will include on an exam by taking good notes throughout the classes leading up to the test.

Writers may imply information without directly stating a fact for a variety of reasons. Sometimes a writer may not want to come out explicitly and state a bias, but may imply or hint at his or her preference for one political party or another. You have to read carefully to find implications because they are indirect, but watching for them will help you comprehend the whole meaning of a passage.

Learning Vocabulary

Vocabulary specific to certain disciplines helps practitioners in that field engage and communicate with each other. Few people beyond undertakers and archeologists likely use the term sarcophagus in everyday communications, but for those disciplines, it is a meaningful distinction. Looking at the example, you can use context clues to figure out the meaning of the term sarcophagus because it is something undertakers and/or archeologists would recognize. At the very least, you can guess that it has something to do with death. As a potential professional in the field you’re studying, you need to know the lingo. You may already have a system in place to learn discipline-specific vocabulary, so use what you know works for you. Two strong strategies are to look up words in a dictionary (online or hard copy) to ensure you have the exact meaning for your discipline and to keep a dedicated list of words you see often in your reading. You can list the words with a short definition so you have a quick reference guide to help you learn the vocabulary.

Intelligent people always question and evaluate. This doesn’t mean they don’t trust others; they just need verification of facts to understand a topic well. It doesn’t make sense to learn incomplete or incorrect information about a subject just because you didn’t take the time to evaluate all the sources at your disposal. When early explorers were afraid to sail the world for fear of falling off the edge, they weren’t stupid; they just didn’t have all the necessary data to evaluate the situation.

When you evaluate a text, you are seeking to understand the presented topic. Depending on how long the text is, you will perform a number of steps and repeat many of these steps to evaluate all the elements the author presents. When you evaluate a text, you need to do the following:

- Scan the title and all headings.

- Read through the entire passage fully.

- Question what main point the author is making.

- Decide who the audience is.

- Identify what evidence/support the author uses.

- Consider if the author presents a balanced perspective on the main point.

- Recognize if the author introduced any biases in the text.

When you go through a text looking for each of these elements, you need to go beyond just answering the surface question; for instance, the audience may be a specific field of scientists, but could anyone else understand the text with some explanation? Why would that be important?

Analysis Question

Think of an article you need to read for a class. Take the steps above on how to evaluate a text, and apply the steps to the article. When you accomplish the task in each step, ask yourself and take notes to answer the question: Why is this important? For example, when you read the title, does that give you any additional information that will help you comprehend the text? If the text were written for a different audience, what might the author need to change to accommodate that group? How does an author’s bias distort an argument? This deep evaluation allows you to fully understand the main ideas and place the text in context with other material on the same subject, with current events, and within the discipline.

When you learn something new, it always connects to other knowledge you already have. One challenge we have is applying new information. It may be interesting to know the distance to the moon, but how do we apply it to something we need to do? If your biology instructor asked you to list several challenges of colonizing Mars and you do not know much about that planet’s exploration, you may be able to use your knowledge of how far Earth is from the moon to apply it to the new task. You may have to read several other texts in addition to reading graphs and charts to find this information.

That was the challenge the early space explorers faced along with myriad unknowns before space travel was a more regular occurrence. They had to take what they already knew and could study and read about and apply it to an unknown situation. These explorers wrote down their challenges, failures, and successes, and now scientists read those texts as a part of the ever-growing body of text about space travel. Application is a sophisticated level of thinking that helps turn theory into practice and challenges into successes.

Preparing to Read for Specific Disciplines in College

Different disciplines in college may have specific expectations, but you can depend on all subjects asking you to read to some degree. In this college reading requirement, you can succeed by learning to read actively, researching the topic and author, and recognizing how your own preconceived notions affect your reading. Reading for college isn’t the same as reading for pleasure or even just reading to learn something on your own because you are casually interested.

In college courses, your instructor may ask you to read articles, chapters, books, or primary sources (those original documents about which we write and study, such as letters between historic figures or the Declaration of Independence). Your instructor may want you to have a general background on a topic before you dive into that subject in class, so that you know the history of a topic, can start thinking about it, and can engage in a class discussion with more than a passing knowledge of the issue.

If you are about to participate in an in-depth six-week consideration of the U.S. Constitution but have never read it or anything written about it, you will have a hard time looking at anything in detail or understanding how and why it is significant. As you can imagine, a great deal has been written about the Constitution by scholars and citizens since the late 1700s when it was first put to paper (that’s how they did it then). While the actual document isn’t that long (about 12–15 pages depending on how it is presented), learning the details on how it came about, who was involved, and why it was and still is a significant document would take a considerable amount of time to read and digest. So, how do you do it all? Especially when you may have an instructor who drops hints that you may also love to read a historic novel covering the same time period . . . in your spare time , not required, of course! It can be daunting, especially if you are taking more than one course that has time-consuming reading lists. With a few strategic techniques, you can manage it all, but know that you must have a plan and schedule your required reading so you are also able to pick up that recommended historic novel—it may give you an entirely new perspective on the issue.

Strategies for Reading in College Disciplines

No universal law exists for how much reading instructors and institutions expect college students to undertake for various disciplines. Suffice it to say, it’s a LOT.

For most students, it is the volume of reading that catches them most off guard when they begin their college careers. A full course load might require 10–15 hours of reading per week, some of that covering content that will be more difficult than the reading for other courses.

You cannot possibly read word-for-word every single document you need to read for all your classes. That doesn’t mean you give up or decide to only read for your favorite classes or concoct a scheme to read 17 percent for each class and see how that works for you. You need to learn to skim, annotate, and take notes. All of these techniques will help you comprehend more of what you read, which is why we read in the first place. We’ll talk more later about annotating and note-taking, but for now consider what you know about skimming as opposed to active reading.

Skimming is not just glancing over the words on a page (or screen) to see if any of it sticks. Effective skimming allows you to take in the major points of a passage without the need for a time-consuming reading session that involves your active use of notations and annotations. Often you will need to engage in that painstaking level of active reading, but skimming is the first step—not an alternative to deep reading. The fact remains that neither do you need to read everything nor could you possibly accomplish that given your limited time. So learn this valuable skill of skimming as an accompaniment to your overall study tool kit, and with practice and experience, you will fully understand how valuable it is.

When you skim, look for guides to your understanding: headings, definitions, pull quotes, tables, and context clues. Textbooks are often helpful for skimming—they may already have made some of these skimming guides in bold or a different color, and chapters often follow a predictable outline. Some even provide an overview and summary for sections or chapters. Use whatever you can get, but don’t stop there. In textbooks that have some reading guides, or especially in texts that do not, look for introductory words such as First or The purpose of this article . . . or summary words such as In conclusion . . . or Finally . These guides will help you read only those sentences or paragraphs that will give you the overall meaning or gist of a passage or book.

Now move to the meat of the passage. You want to take in the reading as a whole. For a book, look at the titles of each chapter if available. Read each chapter’s introductory paragraph and determine why the writer chose this particular order. Depending on what you’re reading, the chapters may be only informational, but often you’re looking for a specific argument. What position is the writer claiming? What support, counterarguments, and conclusions is the writer presenting?

Don’t think of skimming as a way to buzz through a boring reading assignment. It is a skill you should master so you can engage, at various levels, with all the reading you need to accomplish in college. End your skimming session with a few notes—terms to look up, questions you still have, and an overall summary. And recognize that you likely will return to that book or article for a more thorough reading if the material is useful.

Active Reading Strategies

Active reading differs significantly from skimming or reading for pleasure. You can think of active reading as a sort of conversation between you and the text (maybe between you and the author, but you don’t want to get the author’s personality too involved in this metaphor because that may skew your engagement with the text).

When you sit down to determine what your different classes expect you to read and you create a reading schedule to ensure you complete all the reading, think about when you should read the material strategically, not just how to get it all done . You should read textbook chapters and other reading assignments before you go into a lecture about that information. Don’t wait to see how the lecture goes before you read the material, or you may not understand the information in the lecture. Reading before class helps you put ideas together between your reading and the information you hear and discuss in class.

Different disciplines naturally have different types of texts, and you need to take this into account when you schedule your time for reading class material. For example, you may look at a poem for your world literature class and assume that it will not take you long to read because it is relatively short compared to the dense textbook you have for your economics class. But reading and understanding a poem can take a considerable amount of time when you realize you may need to stop numerous times to review the separate word meanings and how the words form images and connections throughout the poem.

The SQ3R Reading Strategy

You may have heard of the SQ3R method for active reading in your early education. This valuable technique is perfect for college reading. The title stands for S urvey, Q uestion, R ead, R ecite, R eview, and you can use the steps on virtually any assigned passage. Designed by Francis Pleasant Robinson in his 1961 book Effective Study, the active reading strategy gives readers a systematic way to work through any reading material.

Survey is similar to skimming. You look for clues to meaning by reading the titles, headings, introductions, summary, captions for graphics, and keywords. You can survey almost anything connected to the reading selection, including the copyright information, the date of the journal article, or the names and qualifications of the author(s). In this step, you decide what the general meaning is for the reading selection.

Question is your creation of questions to seek the main ideas, support, examples, and conclusions of the reading selection. Ask yourself these questions separately. Try to create valid questions about what you are about to read that have come into your mind as you engaged in the Survey step. Try turning the headings of the sections in the chapter into questions. Next, how does what you’re reading relate to you, your school, your community, and the world?

Read is when you actually read the passage. Try to find the answers to questions you developed in the previous step. Decide how much you are reading in chunks, either by paragraph for more complex readings or by section or even by an entire chapter. When you finish reading the selection, stop to make notes. Answer the questions by writing a note in the margin or other white space of the text.

You may also carefully underline or highlight text in addition to your notes. Use caution here that you don’t try to rush this step by haphazardly circling terms or the other extreme of underlining huge chunks of text. Don’t over-mark. You aren’t likely to remember what these cryptic marks mean later when you come back to use this active reading session to study. The text is the source of information—your marks and notes are just a way to organize and make sense of that information.

Recite means to speak out loud. By reciting, you are engaging other senses to remember the material—you read it (visual) and you said it (auditory). Stop reading momentarily in the step to answer your questions or clarify confusing sentences or paragraphs. You can recite a summary of what the text means to you. If you are not in a place where you can verbalize, such as a library or classroom, you can accomplish this step adequately by saying it in your head; however, to get the biggest bang for your buck, try to find a place where you can speak aloud. You may even want to try explaining the content to a friend.

Review is a recap. Go back over what you read and add more notes, ensuring you have captured the main points of the passage, identified the supporting evidence and examples, and understood the overall meaning. You may need to repeat some or all of the SQR3 steps during your review depending on the length and complexity of the material. Before you end your active reading session, write a short (no more than one page is optimal) summary of the text you read.

Reading Primary and Secondary Sources

Primary sources are original documents we study and from which we glean information; primary sources include letters, first editions of books, legal documents, and a variety of other texts. When scholars look at these documents to understand a period in history or a scientific challenge and then write about their findings, the scholar’s article is considered a secondary source. Readers have to keep several factors in mind when reading both primary and secondary sources.

Primary sources may contain dated material we now know is inaccurate. It may contain personal beliefs and biases the original writer didn’t intend to be openly published, and it may even present fanciful or creative ideas that do not support current knowledge. Readers can still gain great insight from primary sources, but readers need to understand the context from which the writer of the primary source wrote the text.

Likewise, secondary sources are inevitably another person’s perspective on the primary source, so a reader of secondary sources must also be aware of potential biases or preferences the secondary source writer inserts in the writing that may persuade an incautious reader to interpret the primary source in a particular manner.

For example, if you were to read a secondary source that is examining the U.S. Declaration of Independence (the primary source), you would have a much clearer idea of how the secondary source scholar presented the information from the primary source if you also read the Declaration for yourself instead of trusting the other writer’s interpretation. Most scholars are honest in writing secondary sources, but you as a reader of the source are trusting the writer to present a balanced perspective of the primary source. When possible, you should attempt to read a primary source in conjunction with the secondary source. The Internet helps immensely with this practice.

Researching Topic and Author

During your preview stage, sometimes called pre-reading, you can easily pick up on information from various sources that may help you understand the material you’re reading more fully or place it in context with other important works in the discipline. If your selection is a book, flip it over or turn to the back pages and look for an author’s biography or note from the author. See if the book itself contains any other information about the author or the subject matter.

The main things you need to recall from your reading in college are the topics covered and how the information fits into the discipline. You can find these parts throughout the textbook chapter in the form of headings in larger and bold font, summary lists, and important quotations pulled out of the narrative. Use these features as you read to help you determine what the most important ideas are.

Remember, many books use quotations about the book or author as testimonials in a marketing approach to sell more books, so these may not be the most reliable sources of unbiased opinions, but it’s a start. Sometimes you can find a list of other books the author has written near the front of a book. Do you recognize any of the other titles? Can you do an Internet search for the name of the book or author? Go beyond the search results that want you to buy the book and see if you can glean any other relevant information about the author or the reading selection. Beyond a standard Internet search, try the library article database. These are more relevant to academic disciplines and contain resources you typically will not find in a standard search engine. If you are unfamiliar with how to use the library database, ask a reference librarian on campus. They are often underused resources that can point you in the right direction.

Understanding Your Own Preset Ideas on a Topic

Consider this scenario: Laura really enjoys learning about environmental issues. She has read many books and watched numerous televised documentaries on this topic and actively seeks out additional information on the environment. While Laura’s interest can help her understand a new reading encounter about the environment, Laura also has to be aware that with this interest, she brings forward her preset ideas and biases about the topic. Sometimes these prejudices against other ideas relate to religion or nationality or even just tradition. Without evidence, thinking the way we always have is not a good enough reason; evidence can change, and at the very least it needs honest review and assessment to determine its validity. Ironically, we may not want to learn new ideas because that may mean we would have to give up old ideas we have already mastered, which can be a daunting prospect.

With every reading situation about the environment, Laura needs to remain open-minded about what she is about to read and pay careful attention if she begins to ignore certain parts of the text because of her preconceived notions. Learning new information can be very difficult if you balk at ideas that are different from what you’ve always thought. You may have to force yourself to listen to a different viewpoint multiple times to make sure you are not closing your mind to a viable solution your mindset does not currently allow.

Can you think of times you have struggled reading college content for a course? Which of these strategies might have helped you understand the content? Why do you think those strategies would work?

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/college-success-concise/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Amy Baldwin

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: College Success Concise

- Publication date: Apr 19, 2023

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-success-concise/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-success-concise/pages/3-3-effective-reading-strategies

© Sep 20, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

7.3: Text- Types of College Reading Materials

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 59530

- Lumen Learning

As a college student, you will eventually choose a major or focus of study. In your first year or so, though, you’ll probably have to complete “core” or required classes in different subjects. For example, even if you plan to major in English, you may still have to take at least one science, history, and math class. These different academic disciplines (and the instructors who teach them) can vary greatly in terms of the materials that students are assigned to read. Not all college reading is the same. So, what types can you expect to encounter?

Probably the most familiar reading material in college is the textbook . These are academic books, usually focused on one discipline, and their primary purpose is to educate readers on a particular subject—”Principles of Algebra,” for example, or “Introduction to Business.” It’s not uncommon for instructors to use one textbook as the primary text for an entire course. Instructors typically assign chapters as readings and may include any word problems or questions in the textbook, too.

Instructors may also assign academic articles or news articles . Academic articles are written by people who specialize in a particular field or subject, while news articles may be from recent newspapers and magazines. For example, in a science class, you may be asked to read an academic article on the benefits of rainforest preservation, whereas in a government class, you may be asked to read an article summarizing a recent presidential debate. Instructors may have you read the articles online or they may distribute copies in class or electronically.

The chief difference between news and academic articles is the intended audience of the publication. News articles are mass media: They are written for a broad audience, and they are published in magazines and newspapers that are generally available for purchase at grocery stores or bookstores. They may also be available online. Academic articles, on the other hand, are usually published in scholarly journals with fairly small circulations. While you won’t be able to purchase individual journal issues from Barnes and Noble, public and school libraries do make these journal issues and individual articles available. It’s common to access academic articles through online databases hosted by libraries.

Literature and Nonfiction Books

Instructors use literature and nonfiction books in their classes to teach students about different genres, events, time periods, and perspectives. For example, a history instructor might ask you to read the diary of a girl who lived during the Great Depression so you can learn what life was like back then. In an English class, your instructor might assign a series of short stories written during the 1960s by different American authors, so you can compare styles and thematic concerns.

Literature includes short stories, novels or novellas, graphic novels, drama, and poetry. Nonfiction works include creative nonfiction—narrative stories told from real life—as well as history, biography, and reference materials. Textbooks and scholarly articles are specific types of nonfiction; often their purpose is to instruct, whereas other forms of nonfiction be written to inform, to persuade, or to entertain.

- College Success. Authored by : Jolene Carr. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

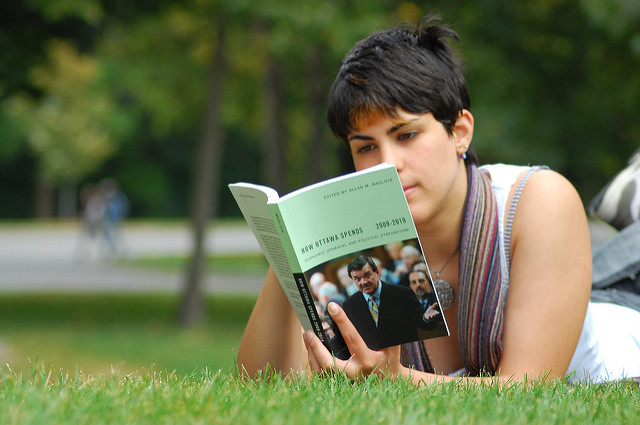

- Image of woman reading on lawn. Authored by : Grant. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/7sFp2A . License : CC BY: Attribution

The 7 Best Study Methods for All Types of Students

These are seven effective study methods and techniques for students looking to optimize their learning habits.

- By Sander Tamm

- Jan 10, 2023

E-student.org is supported by our community of learners. When you visit links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

“You must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool.” Richard Feynman

Choosing the correct study method is a crucial part of the learning process that students too often skip over. Picking the best study method for the situation can help students reach their full potential, while a poorly chosen study technique will kill any real progress, no matter how hard the student tries to study.

If you’re reading this article, you’re likely the exception, but the reality is that most students rely on ineffective study strategies. Researchers have found that between 83.6% and 84% of students rely on rereading: a study method that provides minimal benefits .

There are far superior study methods out there than rereading. Methods that have been developed and researched by the world’s top learning scientists. Yet, surprisingly few students have ever heard of them. That is why utilizing them effectively will give you not only an edge but an entire leg up on the competition.

These are the seven best study methods all students should know about:

Best Study Methods

Spaced repetition.

Spaced repetition , sometimes called spaced practice, interleaved practice, or spaced retrieval, is a study method that involves separating your study sessions into spaced intervals. It’s a simple concept but a game-changer to most students because of how powerful it is.

To demonstrate how spaced repetition works, let’s bring a real-life example. Let’s say you have an exam coming up in 36 days, and your first study session begins today. In this situation, a well-optimized interval might be:

- Session 1: Day 1

- Session 2: Day 7

- Session 3: Day 16

- Session 4: Day 35

- Exam Date: Day 36

In a nutshell, it’s the opposite of cramming and all-nighters. Rather than concentrating all studying into a small time frame, this method requires you to space out your studying by reviewing and recalling information at optimal intervals until the material has been memorized.

In the 21st century, this technique has gathered increasing popularity, and it’s not without reason. Spaced repetition manages to combine all the existing knowledge we have on human memory, and it uses that knowledge to create optimized algorithms for studying. One of the most popular examples of spaced repetition algorithms is Anki , based on another popular algorithm, SuperMemo .

For example, there is no better study method for medical students than Anki-based flashcard decks. There are entire online communities surrounding medical school Anki. You can get a small glimpse of that by heading over to r/medicalschoolanki .

There, you’ll find a breadth of different medical school Anki decks to choose from, such as:

- Pepper deck

- Lightyear deck

- UWorld deck

- Premed95 deck

But, the power of spaced repetition is not at all only applicable to medical students. Anyone trying to become a better and more efficient learner can benefit from spaced repetition. Spaced repetition is used in conjunction with other study methods, and it’s especially powerful when combined with the following study method we’ll discuss: active recall.

Active Recall

Active recall , sometimes called retrieval practice or practice testing, is a study technique involving actively recalling information (rather than just reading or re-reading it) by testing yourself repeatedly. Most students dread the word “test” for good reasons. After all, tests and exams can be very stressful because they are usually the main point of measure for your academic success.

However, active recall teaches us to look at testing from another angle. Not only should we learn for tests, but we should also learn by testing. Through flashcards, self-generated questions, and practice tests, this study method uses self-testing to help your brain memorize, retain, and retrieve information more efficiently.

One study found that students who conducted only one practice test before an exam got 17% better results right after. Two more studies conducted in 2005 and 2012 , plus a 2017 meta-analysis , yielded similar results, finding that students who used active recall and self-testing outperformed students who did not.

If you’re practicing for an upcoming exam, there’s no better study method than active recall. By using active recall, you’re essentially testing yourself dozens of times over. If you conduct these practice tests over a long period of time through spaced repetition, you’ll be able to ace any exam without cramming.

Keep in mind, though, that while very effective, active recall is also one of the most tiring study techniques on this list. It requires strong mental focus, deep concentration, and intense mental stamina. Active recall is cognitively demanding, so don’t expect to breeze through your learning materials with this method.

Next, I’ll cover my favorite time management strategy for students: the Pomodoro method.

Pomodoro Study Method

The Pomodoro study method is a time-management technique that uses a timer to break down your studying into 25-minute (or 45-minute) increments, called Pomodoro sessions. Then, after each session, you’ll take a 5-minute (or 15-minute) break, during which you entirely distance yourself from the study topic. And after completing four such sessions, you’ll take a more extended 15-to-30-minute break.

To try the Pomodoro technique without installing any software or buying a timer, I recommend you go to YouTube. YouTube is full of Pomodoro-based “study with me” videos from channels such as TheStrive Studies , Ali Abdaal , and MDprospect . Many of them include music, though, so if you’re distracted by music while studying, you might benefit from a purpose-built Pomodoro application such as TomatoTimer or RescueTime .

There are various benefits to using the Pomodoro method: it’s a simple and straightforward technique, it forces you to map out your daily tasks and activities, allows for easy tracking of the amount of time spent on each task, and it provides short bursts of concentrated work together with resting periods.

But, it’s also worth noting that the scientific evidence behind the Pomodoro method is mostly conjectural as there is little scientific research on its effectiveness. And another drawback of the Pomodoro study technique is that it’s not ideal for tasks that require prolonged, uninterrupted focusing. For these kinds of tasks, I recommend that you look into the closely related Flowtime method instead.

Despite that, though, I use the Pomodoro method on a daily basis myself, and it has become an integral and irreplaceable part of my workflow.

Feynman Technique

The Feynman Technique is a flexible, easy-to-use, and effective study technique developed by Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman. It is based on a simple idea: the best way to learn any topic is by teaching it to a sixth-grade child.

While this concept is not as advanced as the super-optimized spaced repetition algorithms I covered earlier, it’s still a method that continues to be relevant nearly a century after its creation.

The Feynman Technique is a powerful learning tool that requires learners to step out of their comfort zone by breaking down even the most complex topics into easily digestible chunks. Digestible enough for the average sixth-grade child.

This may seem like an easy task at first. After all, how difficult could it be to explain something to a child? In practice, it can be very difficult because you have to simplify and explain everything in an age-appropriate manner. When you start using the method, you’ll quickly realize that unless you have fully mastered the topic, meeting a child at their level of understanding is not easy.

To explain something clearly, you need to define all unfamiliar terms, generate straightforward explanations for complex ideas, understand connections between different topics and sub-topics, and articulate what is learned clearly and concisely. The Feynman Technique forces you to learn more deeply and think critically about what you are learning, and that is also why it’s a compelling learning method.

Leitner System

The Leitner System is a simple and effective study method that uses a flashcard-based learning strategy to maximize memorization. It was developed by Sebastian Leitner back in 1972, and it was a source of inspiration to many of the newer flashcard-based methods that succeeded it, such as Anki.

To use the method, you’ll first need to create flashcards. On the front of the cards, you’ll write the questions, and on the back, the answers. Then, once you have your flashcards ready, get three “Leitner boxes” big enough to hold all the cards you’ve created. Let’s name them Box 1, 2, and 3.

Now, you’re all set to start studying with your flashcards. In the beginning, you’ll place all cards in Box 1. Take a card from Box 1 and try to retrieve the answer from your memory. If you recall the answer, put it in Box 2. If not, keep it in Box 1. Then, you’ll repeat this until you’ve reviewed all the cards in Box 1 at least once. After that, you’ll start reviewing each box of cards based on time intervals.

Here’s an animation that shows how the Leitner System works:

Besides card placement, another important detail of the system is scheduling. Every box has a set review frequency, with Box 1 being reviewed the most frequently as it contains all the most difficult-to-learn flashcards. Box 3, on the other hand, will contain the cards you’ve already recalled correctly, which is why it does not need to be reviewed as frequently.

If you’ve never heard of the Leitner system, you might be surprised to hear that some of the world’s biggest learning platforms, such as Duolingo, use a variation to teach hundreds of millions of students. It’s particularly effective at language learning due to the ease of creating translation-based flashcards.

While I love the Leitner System for its simplicity, I don’t use it often anymore due to the lengthy setup process, and other flashcard study methods, such as Anki, tend to be more time-efficient. But, if you prefer physical flashcards over virtual ones, you should consider using the Leitner system. It’s a beautiful study technique that has stood the test of time.

PQ4R Study Method

The PQ4R is a study method developed by researchers Thomas and Robinson in 1972 – the same year as the Leitner System was conceived. PQ4R stands for the steps used for learning something new: Preview, Question, Read, Reflect, Recite, and Review. It’s commonly used to improve reading comprehension and is an essential method for students with reading disabilities.

However, the usefulness of PQ4R is not restricted to students with reading disabilities. The same six steps can be taken by any student trying to understand better what they’re reading. Improving reading comprehension is a worthy goal for any student, and if you need to read through a massive textbook for an exam, the PQ4R method offers a practical framework. It will allow you to understand all the passages of the text better and help you retain the information better.

By improving our reading comprehension, we can better synthesize information and interpret text. However, we must be careful not to let this strategy consume too much of our time in study sessions. Many modern learning scientists consider reading a passive and ineffective study strategy, and it’s best to rely on other methods when you can.

While I don’t use this study method as frequently as most other methods on this list, I still consider it an important strategy in my skill set. Whenever I need to extract the most critical details from a large textbook, I bring out the PQ4R to help me get through the information quicker while boosting memorization and retention. The PQ4R is a good study method to have ready, but it’s not something you should view as your primary strategy.

SQ3R Study Method

The SQ3R study method was developed by Francis P. Robinson in 1946 and is the predecessor of the PQ4R method. It’s a time-proven study technique that can be adapted to virtually any subject. The method’s name stands for Survey, Question, Read, Recite, and Review and it can be used to study anything quicker, better, and in a more structured way than conventional methods.

While groundbreaking for its time, the SQ3R study method has the same drawbacks as the newer PQ4R method. For one, it’s mainly used for improving reading comprehension, and reading is not considered an effective study strategy anymore. Another problem the method faces is that it lacks the “reflection” component that the newer PQ4R study method brings to the table.

In addition, three of the five steps of this method involve a passive approach (surveying, reading, and reviewing) rather than an active one. Modern learning theories suggest active retrieval is far better for information retention than passive reading. Thus, I recommend using this study method only when you don’t have the time to use a more robust method, such as spaced repetition.

SQ3R is best used when you have limited time to study, and your primary source of information comes from a textbook. In such cases, the technique can be very helpful for summarizing the key points written in the source material.

Now, it’s time to start wrapping up this article.

In conclusion, there are many excellent study methods you have to choose from as a student in the 21st century. The best one for you will depend on your learning style, the material you are studying, and how much free time you have. When possible, I recommend you study using a combination of spaced repetition, active recall, and the Pomodoro method. But the other strategies listed here certainly have their uses as well. Above all, try to be flexible and keep an open mind. In doing so, you’ll be able to maximize your learning potential.

Sander Tamm

The 13 most effective note-taking methods.

These are efficient note-taking methods that anyone can pick up and use to take better notes.

Robin Arzón’s MasterClass Review: Mental Strength

In her MasterClass, Robin Arzón shares her personal experience transitioning from a lawyer to an ultra-marathoner and how you can optimize your own mental strength to pursue your life’s purpose.

Review of Demystifying Artificial Intelligence on Skillshare

Are you trying to find a brief introduction to get started with machine learning? Read our review of Christian Heilmann’s course on Skillshare to see if this is a good fit for you.

- Available Courses

- The Google Teacher Podcast

- Kasey as a Guest

- Video Library

- FREE Downloads

- Choice Boards

- Google Resources

- Google Classroom

- For Tech Coaches

- Favorite Books & Gadgets

- Presentations

- Blended Learning with Google

- Google from A To Z

- Dynamic Learning Workshop

- Bulk Discounts

- About Kasey Bell

- Google Training for Schools

- Sponsorship and Advertising

- Connect on Social

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

Shake Up Learning

Shake Up Learning in your classroom today!

How to Plan an AWESOME Book Study!

May 3, 2022 by Kasey Bell

So I decided to put this post together, How to Plan an Awesome Book Study, to help guide you along the way.

I have been a part of what seems like hundreds of mandated book studies that simply fall flat.

Some books were great, some were not. Some conversations were great, others were BOR—ING.

Some studies changed my mindset and/or my practice, some were not worth the ink on the paper.

Let’s break this down and think through some ways to improve your professional group book studies!

Listen to this article.

STEP 1: Define Your Audience

Who will be reading this book? Is it open to educators at all levels and subject areas? Or is this a study for administrators? What type of administrators? Maybe this is a study for instructional coaches, a tech team, or even one that involves parents and the community.

Think through all of the possibilities for your audience and be sure you are forming a group with meaning. If not, consider forming multiple groups to better meet the needs of everyone. Trust me, nothing is worse than being forced to read a book about something that doesn’t really pertain to your role as an educator.

If you are unsure who will be participating, send out a Google Form survey.

STEP 2: Select Book Study Leaders

You need to ensure that someone is taking the lead so this whole shebang doesn’t fall apart. Is that person you? Maybe. Better yet, form a collaborative partnership or team to take the reigns and help the group navigate.

STEP 3: Define Your Goals

Why are you doing this book study? Is it because your admin says you have to do two book studies per year? I hope not. A meaningful book study should always start with the why, just like the learning in our classrooms.

- Is your goal to help teachers become more comfortable with technology? Is a book going to do that? Maybe.

- Is your goal to get teachers to make the shift to facilitator?

- Is your goal to help shift the mindset of your faculty?

- Is your goal to help teachers learn how to develop better assessments?

- Is your goal to focus on PBL?

- Is your goal to introduce innovative ideas?

Think carefully about the vision for your organization, school, or group, and connect this book study to your mission and goals. Make sure every one of the leaders is on the same page and in agreement before you move to step four.

STEP 4: Choosing a Book for Your Book Study

Once you have defined your audience and selected your leaders, it is time to select a book. Give your participants a choice! If you want buy-in and to truly effect change in your organization, you must give the participants a say in what they read. There is no shortage of books out there.

My suggestion is to have the leaders of the book study pick three to five books that fit the needs of your specific audience. Then share the choices with your participants for a vote. (Looking for ideas? Check out my recommended book list .)

Voting on a book can be fun! This can be something you do as a group, face-to-face, where you offer a “tasting” of the book options. Or with larger groups, you can create a Google Form for voting. Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms also offer some easy-to-use polling options, depending on how you communicate with your group.

If your group is over 20, DO NOT send this out as a mass email and ask for replies! What a waste of time. Use a digital tool to do the work for you.

STEP 5: Leaders Read the Book and Plan the Study

Yes, you read that correctly, read and plan the study before you start. Novel idea, I know! If you wing it, or just stay a chapter ahead, you will fail to connect the dots to the bigger picture and your overall goal.

So read, take notes, and begin to picture all the ways this book study could be facilitated, and how you will divide up the chapters and material. Flag the sections that you expect could meet resistance or disagreement. Gather additional resources. This piece is critical before you move on to step six.

STEP 6: Decide How You Will Facilitate the Book Study

Facilitating a book study doesn’t have to be complicated if you plan and organize.

- Plan out your timeline and decide on due dates for each chapter.

- Create discussion questions for each chapter.

- You may also have activities associated with each chapter. If so, now is the time to plan those out. Consider having participants create something to represent their learning, share reflections, sketch notes, booksnaps , lesson ideas, or other content related to the book’s topic.

- When and where will you meet to discuss?

- Google Classroom – great for assignments, calendars, and discussions in one location!

- Any type of website creator

- Facebook group

- Twitter with a unique hashtag

- Google Sites

- Google Groups

- Goodreads group

STEP 7: Facilitate with Finesse!

Facilitate your book study with some TLC and genuine support! Build relationships and go beyond the content of the book. Find ways to connect and learn with your group. Don’t just ask and respond to questions, make this something special for participants.

- Find ways to show positive support to those who struggle to keep up.

- Make it fun and engaging! Give away some swag or door prizes.

- Brag to administrators! Be sure you invite and tag your administrators if they are not participating so they can see the learning and support.

STEP 8: FOLLOW UP

One of the critical missing pieces to most professional learning experiences is follow-up.

Don’t forget to set a few reminders, and schedule some tweets or posts to help your participants review important concepts and IMPLEMENT ideas from the book study.

Offer a way for participants to share what they have implemented with the group. Just don’t let it all fade away.

You may also want to connect this back to a bigger project where participants are required to design and implement it by a certain date.

Ready. Set. Go!

I hope this helps you think through your book study projects and create a meaningful experience for your participants. Have more ideas to add to this list? Leave me a comment down below!

The Perfect Book Study Package!

The Shake Up Learning books were designed with book studies in mind! Not only are these books a great read for any educator, any grade level, any subject, any role, but these books have the entire package to help you facilitate a successful book study!

In Shake Up Learning and Blended Learning with Google, you will find tons of support for your professional book study!

- Discussion questions after each chapter . You don’t have to write your own! These are ready to go!

- Dedicated reflection pages after each chapter , helping you to encourage participants to think and reflect on their reading.

- Web resources and videos to support the books, including a dedicated webpage for each chapter!

- Planning and Implementation Chapters , to help readers TAKE ACTION on the content they read by designing meaningful lesson plans.

- FREE Downloads and Templates

- Meet the author! Contact me about doing a video chat with your group!

- FREE Stickers to support your book study!

- Bulk discounts for 10 or more books.

- Large group discounts on the online workshops.

© Shake Up Learning 2023. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kasey Bell and Shake Up Learning with appropriate and specific direction to the original content on ShakeUpLearning.com. See: Copyright Policy.

Subscribe Today!

Get the inside scoop.

There was an error submitting your subscription. Please try again.

- Contact Shake Up Learning

Privacy Overview

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- Types of Sources Explained | Examples & Tips

Types of Sources Explained | Examples & Tips

Published on May 19, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Throughout the research process , you’ll likely use various types of sources . The source types commonly used in academic writing include:

Academic journals

- Encyclopedias

Table of contents

Primary, secondary, and tertiary sources, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about types of sources.

Academic journals are the most up-to-date sources in academia. They’re typically published multiple times a year and contain cutting-edge research. Consult academic journals to find the most current debates and research topics in your field.

There are many kinds of journal articles, including:

- Original research articles: These publish original data ( primary sources )

- Theoretical articles: These contribute to the theoretical foundations of a field.

- Review articles: These summarize the current state of the field.

Credible journals use peer review . This means that experts in the field assess the quality and credibility of an article before it is published. Journal articles include a full bibliography and use scholarly or technical language.

Academic journals are usually published online, and sometimes also in print. Consult your institution’s library to find out what academic journals they provide access to.

Learn how to cite a journal article

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Academic books are great sources to use when you need in-depth information on your research or dissertation topic .

They’re typically written by experts and provide an extensive overview and analysis of a specific topic. They can be written by a single author or by multiple authors contributing individual chapters (often overseen by a general editor).

Books published by respected academic publishing houses and university presses are typically considered trustworthy sources. Academic books usually include a full bibliography and use scholarly or technical language. Books written for more general audiences are less relevant in an academic context.

Books can be accessed online or in print. Your institution’s library will likely contain access to a wide selection of each.

Learn how to cite a book

Websites are great sources for preliminary research and can help you to learn more about a topic you’re new to.

However, they are not always credible sources . Many websites don’t provide the author’s name, so it can be hard to tell if they’re an expert. Websites often don’t cite their sources, and they typically don’t subject their content to peer review.

For these reasons, you should carefully consider whether any web sources you use are appropriate to cite or not. Some websites are more credible than others. Look for DOIs or trusted domain extensions:

- URLs that end with .edu are specifically educational resources.

- URLs that end with .gov are government-related

Both of these are typically considered trustworthy.

Learn how to cite a website

Newspapers can be valuable sources, providing insights on current or past events and trends.

However, news articles are not always reliable and may be written from a biased perspective or with the intention of promoting a political agenda. News articles usually do not cite their sources and are written for a popular, rather than academic, audience.

Nevertheless, newspapers can help when you need information on recent topics or events that have not been the subject of in-depth academic study. Archives of older newspapers can also be useful sources for historical research.

Newspapers are published in both digital and print form. Consult your institution’s library to find out what newspaper archives they provide access to.

Learn how to cite a newspaper article

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

Encyclopedias are reference works that contain summaries or overviews of topics rather than original insights. These overviews are presented in alphabetical order.

Although they’re often written by experts, encyclopedia entries are not typically attributed to a single author and don’t provide the specialized knowledge expected of scholarly sources. As a result, they’re best used as sources of background information at the beginning of your research. You can then expand your knowledge by consulting more academic sources.

Encyclopedias can be general or subject-specific:

- General encyclopedias contain entries on diverse topics.

- Subject encyclopedias focus on a particular field and contain entries specific to that field (e.g., Western philosophy or molecular biology).

They can be found online (including crowdsourced encyclopedias like Wikipedia) or in print form.

Learn how to cite Wikipedia

Every source you use will be either a:

- Primary source : The source provides direct evidence about your topic (e.g., a news article).

- Secondary source : The source provides an interpretation or commentary on primary sources (e.g., a journal article).

- Tertiary source : The source summarizes or consolidates primary and secondary sources but does not provide additional analysis or insights (e.g., an encyclopedia).

Tertiary sources are often used for broad overviews at the beginning of a research project. Further along, you might look for primary and secondary sources that you can use to help formulate your position.

How each source is categorized depends on the topic of research and how you use the source.

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

There are many types of sources commonly used in research. These include:

- Journal articles

You’ll likely use a variety of these sources throughout the research process , and the kinds of sources you use will depend on your research topic and goals.

Scholarly sources are written by experts in their field and are typically subjected to peer review . They are intended for a scholarly audience, include a full bibliography, and use scholarly or technical language. For these reasons, they are typically considered credible sources .

Popular sources like magazines and news articles are typically written by journalists. These types of sources usually don’t include a bibliography and are written for a popular, rather than academic, audience. They are not always reliable and may be written from a biased or uninformed perspective, but they can still be cited in some contexts.

In academic writing, the sources you cite should be credible and scholarly. Some of the main types of sources used are:

- Academic journals: These are the most up-to-date sources in academia. They are published more frequently than books and provide cutting-edge research.

- Books: These are great sources to use, as they are typically written by experts and provide an extensive overview and analysis of a specific topic.

It is important to find credible sources and use those that you can be sure are sufficiently scholarly .

- Consult your institute’s library to find out what books, journals, research databases, and other types of sources they provide access to.

- Look for books published by respected academic publishing houses and university presses, as these are typically considered trustworthy sources.

- Look for journals that use a peer review process. This means that experts in the field assess the quality and credibility of an article before it is published.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). Types of Sources Explained | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/types-of-sources/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, types of plagiarism and how to recognize them, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Our Mission

5 Steps to More Effective PD With Book Studies

Educational book studies give teachers opportunities for powerful professional development built on collaboration and connection.

Book studies foster collaboration, provide educators with choices for professional learning, and help teachers explore new ideas. With an explosion of educational texts coming on the market post-pandemic, educators have more book options than ever. The bones of a book study are pretty universal: pick a book, read it, discuss it, earn continuing education credit.

Through my personal experience in a dozen book studies, both as a student and as an author/guest speaker, I’ve witnessed huge differences in book study execution, leading to very different results. Based on these experiences and conversations with book study host Dr. Nikki Vradenburg, NBCT, director of education with Montana PBS, several factors emerged that elevate a basic book study to a truly meaningful professional learning experience.

1. Provide Choice

Pretty simple: Increase engagement and growth by offering choice. Compared with a district-mandated book study done for a whole staff, engagement was greater in a summer course, Vradenburg notes, “because it was the teacher who had found the book study based on their own interest and desire.”

Gather recommendations from teachers, then provide several book options. Better yet, collaborate with other districts—in your state, region, etc.—to offer even more choices and ensure diverse perspectives for discussions (see No. 2 below).

As you build your book list, acknowledge that not all books will lead to action and impact in the classroom. What’s your goal: A feel-good experience? To increase the use of best practices and drive innovation? Explore new theories and methodologies?

If you’re not sure about a book, consider these questions: After we identify with the text and perhaps feel good or inspired, then what? What’s the takeaway? How will this book shift the teaching and learning environment? How will this book help make things better for teachers? For students?

2. Ensure that you have a diverse group of educators

Exposure to new ideas and experiences is critical to helping educators grow. We don’t know what we don’t know. When surrounded by the same people every day, it’s easy to think, “This is what teaching and learning looks like.” To foster greater innovation and increased impact, seek out diverse perspectives. Combine buildings. Coordinate with other districts and cohost your book study. Reach out to a district that looks and operates differently than yours.

Not only does a mixed group of educators fuel divergent thinking, but also it helps teachers break out of their roles within their building. Vradenburg notes, “It’s too easy for us to fall into labels and then have a hard time seeing people in other roles.” Plus, when we’re surrounded by people we see every day—especially our own administration—people tend to censor themselves, Vradenburg points out. While this is respectful, it’s not always the best for growth, problem-solving, or innovation. When teachers interact with educators from outside their district, they can be seen and heard in new ways, deepening the learning experience.

3. Set clear tasks: Read this, complete this

Having a concrete task helps hold teachers accountable for their learning and ensures more vibrant discussion. This doesn’t mean micromanaging the process, just simply providing clear objectives and deadlines. This structure can also help ensure that credit is available for the book study. See my Book Club Sample Framework for ideas.

Book studies are also an effective way to model new technology tools and rethink old favorites. Use a Google Form to gather favorite quotes; use Flip to vlog about two action steps that readers will take based on that chapter; share a Jamboard or Padlet to create a thought chain; go to Mentimeter to make a word cloud.

.css-1sk4066:hover{background:#d1ecfa;} Alternatives to Google Jamboard

4. ensure opportunities to connect.

Make the time to actually talk , whether virtually or in person. Self-paced, asynchronous courses are great for all the obvious reasons, but nothing matches the spark of teachers in a space together talking about their craft. Vradenburg says that the discussions in the Zoom breakout groups were vibrant and continuous. People could vent, connect, reflect, get ideas, and inspire each other far more in these conversations than they could via any writing activity.

We need each other. Despite surrounding us with people all day, teaching can be an oddly isolating profession. “We had a teacher on sabbatical/maternity leave,” Vradenburg shares, “and she chose to attend the book study because her brain needed the connection.” And, yes, our hearts need those connections too, to reenergize and reignite our passion for teaching. It’s hard, but find the time to connect.

5. Include an implementation plan

Everyone’s read the book. The book and the vigorous discussions with diverse educators filled everyone with amazing ideas. Maybe that’s enough. Maybe that’s what’s needed.

But it can also be so much more . Harness all that inspiration to drive change and improve teaching and learning. As you read, take time to identify aspects of teaching and learning that are not working—for students or teachers. Extrapolate potential solutions from the book, and use your discussions to further brainstorm ideas about what could be done instead. Provide a process for participants to work through their ideas to design something —an activity, lesson, unit, or presentation. Vradenburg uses The Educator Canvas , but use any design thinking or framework that works for your team.

The final book study meetup is then a celebration of innovative implementation ideas. Teachers share their designs and receive feedback on them. I’ve seen the tiniest seedling of an idea flourish with the questions, comments, feedback, and support of book study peers.

By including an implementation plan in the book study, you’ll elevate the uplifting, energizing experience into a purposeful exercise in problem-solving and change-making.

Book studies offer endless possibilities: Each book opens the door to new information, each reader brings their own challenges and perspectives, and each discussion ignites unlimited ideas. So go organize. And if you’d like a brainstorming buddy as you plan, please reach out.

18 Best Books on Learning and Building Great Study Habits [2024 Update]

Books about learning are something special. Not only do they give us knowledge, the meta concept of how to learn to learn . Once you discover these concepts, they will make all future knowledge become a little bit easier to grasp.

Learning, after all, is not something we do from first grade until we graduate from college. Learning is something that is done for life.

The days when you could simply go to college and learn everything you need to know, and the quit learning, are long in the past. If those days EVER truly existed.

These days if you want to stay ahead or just stay competitive, you need to constantly learn new things. That is why these learning books for adults are just as important as the grade school or college education you may have received many years in the past.

Sidenote : If you're attending university right now, setting the right goals matter. Check out our post about SMART goal examples for college students.

In this article, we profile 18 books that will help you learn better and create study habits that will help you permanently retain this information.

Let's get to it…

Table of Contents

18 Books on Learning and Improving Your Study Habits

1. the only skill that matters by jonathan a. levi.

Get Your FREE BOOK!

- The book emphasizes the importance of meta-learning, which involves mastering the skill of learning itself to adapt and thrive in a rapidly changing world.

- Levi advocates for a holistic approach to learning, incorporating mindset, memory techniques, and speed reading to enhance cognitive abilities.

- The author highlights the significance of continuous learning and personal growth, promoting the idea that learning is a lifelong skill that can lead to success and fulfillment.

- The book offers practical strategies for optimizing learning, memory retention, and information processing, enabling readers to become more efficient and effective learners.

- Levi encourages readers to embrace a growth mindset and adopt a proactive approach to self-improvement, empowering them to navigate challenges and achieve their full potential.

The sheer amount of information bombarding us every day is overwhelming. How do we stay on top of everything in order to keep our jobs or adapt to the new demands of modern life?

The Only Skill That Matters equips you with what you need to take on the challenges of the future – whether in your professional or personal life. And it’s offered for free. All you need to pay for is shipping and handling.

In the book, Jonathan Levi shares an approach that promises to help you become a super learner. This approach is anchored in neuroscience. Athletes and top performers have used the techniques to propel them to success.

Within the pages, you’ll learn the techniques for reading faster and improving your ability to recall information.

People who have already read this book call it a game changer. If you’re ready to unlock your potential greatness, get the free book.

2. Accelerated Learning Techniques for Students by Joe McCullough

Check Price on Amazon!