- Constructed scripts

- Multilingual Pages

Old English / Anglo-Saxon (Ænglisc)

Old English was the West Germanic language spoken in the area now known as England between the 5th and 11th centuries. Speakers of Old English called their language Englisc , themselves Angle , Angelcynn or Angelfolc and their home Angelcynn or Englaland .

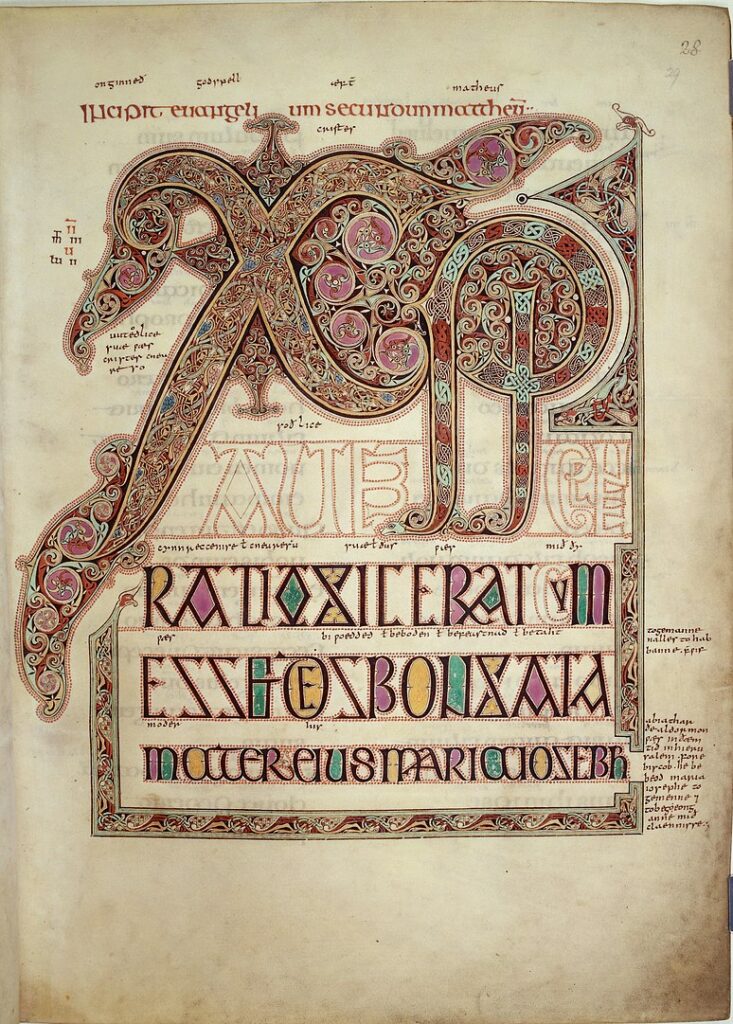

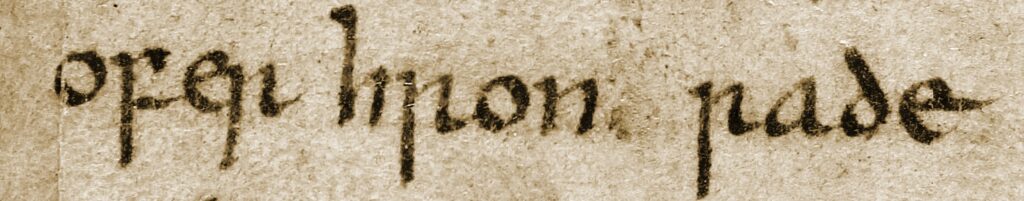

Old English began to appear in writing during the early 8th century. Most texts were written in West Saxon, one of the four main dialects. The other dialects were Mercian, Northumbrian and Kentish.

The Anglo-Saxons adopted the styles of script used by Irish missionaries, such as Insular half-uncial, which was used for books in Latin. A less formal version of minuscule was used for to write both Latin and Old English . From the 10th century Anglo-Saxon scribes began to use Caroline Minuscule for Latin while continuing to write Old English in Insular minuscule. Thereafter Old English script was increasingly influenced by Caroline Minuscule even though it retained a number of distinctive Insular letter-forms.

Anglo-Saxon runes (futhorc/fuþorc)

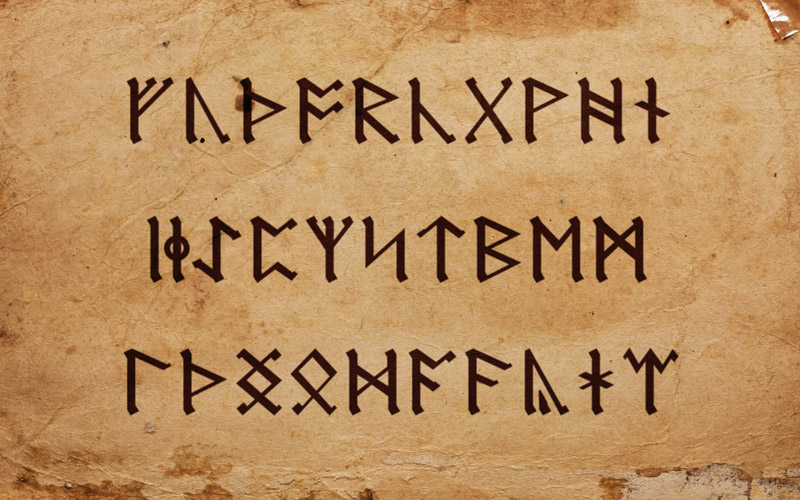

Old English / Anglo-Saxon was first written with a version of the Runic alphabet known as Anglo-Saxon or Anglo-Frisian runes, or futhorc/fuþorc. This alphabet was an extended version of Elder Futhark with between 26 and 33 letters. Anglo-Saxon runes were used probably from the 5th century AD until about the 10th century. They started to be replaced by the Latin alphabet from the 7th century, and after the 9th century the runes were used mainly in manuscripts and were mainly of interest to antiquarians. Their use ceased not long after the Norman conquest.

Old English alphabet

- Long vowels can be marked with macrons. These were not originally used in Old English, but are a more modern invention to distinguish between long and short vowels.

- The alternate forms of g and w (yogh and wynn/wen) were based on the letters used at the time of writing Old English. Today they can be substituted for g and w in modern writing of Old English.

- Yogh originated from an insular form of g and wynn/wen came from a runic letter and was used to represent the non-Latin sound of [w]. The letters g and w were introduced later by French scribes. Yogh came to represent [ç] or [x].

Other versions of the Latin alphabet

Archaic Latin alphabet , Basque-style lettering , Carolingian Minuscule , Classical Latin alphabet , Fraktur , Gaelic script , Merovingian , Modern Latin alphabet , Roman Cursive , Rustic Capitals , Old English , Sütterlin , Visigothic Script

Old English pronunciation

Download an alphabet chart for Old English (Excel speadsheet)

- c = [ʧ] usually before or after a front vowel, [k] elsewhere

- ð/þ = [θ] initially, finally, or next to voiceless consonants, [ð] elsewhere

- f = [f] initially, finally, or next to voiceless consonants, [v] elsewhere

- g (ʒ) = [ɣ] between vowels and voiced consonants, [j] usually before or after a front vowel, [ʤ] after n, [g] elsewhere

- h = [ç] after front vowels, [x] after back vowels, [h] elsewhere

- n = [ŋ] before g (ʒ) and k

- s = [s] initially, finally, or next to voiceless consonants, [z] elsewhere

- The letters j and v were rarely used and were nothing more than varients of i and u respectively.

- The letter k was used only ever rarely and represented [k] (never [ʧ])

Hear how to pronounce Old English:

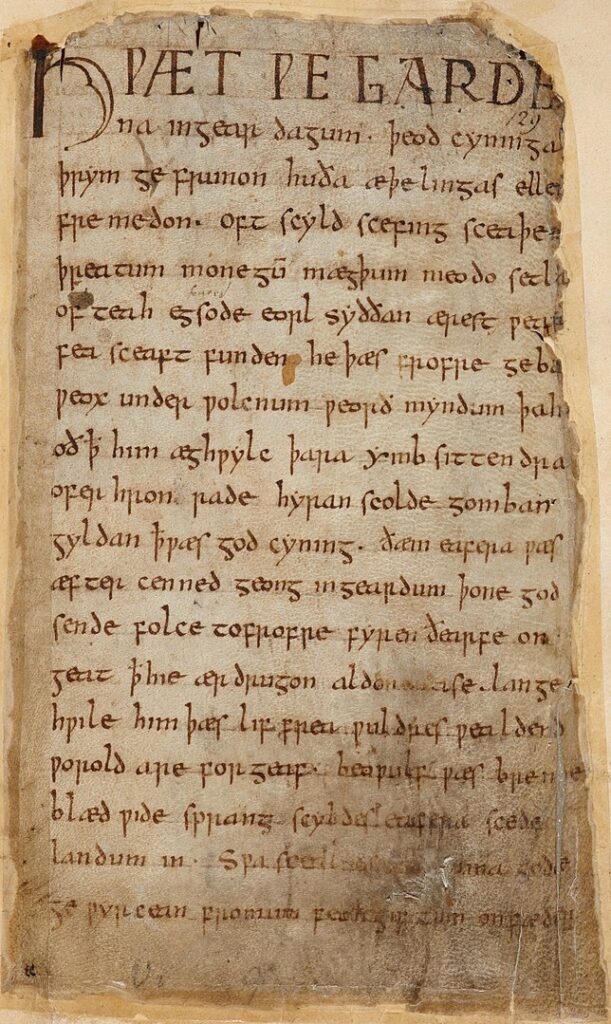

Sample text (Prologue from Beowulf)

Note : this text is based on an original manuscript of Beowulf The spacing between the words and letters may differ from other versions of the text. It is shown in an Old English font on the left ( Beowulf ) and a modern font on the right.

Modern English version

LO , praise of the prowess of people-kings of spear-armed Danes, in days long sped, we have heard, and what honor the athelings won! Oft Scyld the Scefing from squadroned foes, from many a tribe, the mead-bench tore, awing the earls. Since erst he lay friendless, a foundling, fate repaid him: for he waxed under welkin, in wealth he throve, till before him the folk, both far and near, who house by the whale-path, heard his mandate, gave him gifts:

A recording of this text:

You can also find the whole of the Beowulf story, with recording, at: http://ebeowulf.uky.edu/ebeo4.0/CD/main.html

Sample text (Article 1 of the UDHR)

Ealle menn sindon āre and rihtes efen ġeboren, and frēo. Him sindon ġiefeþe ġerād and inġehyġd, and hī sċulon dōn tō ōþrum on brōþorsċipes fēore.

Hear a recording of this text

Translation and recording by E. D. Hayes

Another version of this text by Aram Nersesian in the Old English alphabet:

Transliteration (Latin alphabet)

Eall folc weorþaþ frēo and efne bē āre and rihtum ġeboren. Ġerād and inġehyġd sind heom ġifeþu, and hīe þurfon tō ōþrum ōn fēore brōþorsċipes dōn.

Another version of this text by Japser, provided by Corey Murray:

Ealle menn sindon frēo and ġelīċe on āre and ġerihtum ġeboren. Hīe sindon witt and inġehygde ġetīðod, and hīe sċulon mid brōþorlīċum ferhþe tō heora selfes dōn.

Anglo-Saxon Runes

ᛠᛚᛖ᛬ᛗᛖᚾ᛬ᛋᛁᚾᛞᚩᚾ᛬ᚠᚱᛖᚩ᛬ᚪᚾᛞ᛬ᚷᛖᛚᛁᚳᛖ᛬ᚩᚾ᛬ᚪᚱᛖ᛬ᚪᚾᛞ᛬ᚷᛖᚱᛁᛇᛏᚢᛗ᛬ᚷᛖᛒᚩᚱᛖᚾ᛬ᚻᛁᛖ᛬ᛋᛁᚾᛞᚩᚾ᛬ᚹᛁᛏ᛬ᚪᚾᛞ᛬ᛁᚾᚷᛖᚻᚣᚷᛞᛖ᛬ᚷᛖᛏᛁᚦᚩᛞ᛬ᚪᚾᛞ᛬ᚻᛁᛖ᛬ᛋᚳᚢᛚᚩᚾ᛬ᛗᛁᛞ᛬ᛒᚱᚩᚦᚩᚱᛚᛁᚳᚢᛗ᛬ᚠᛖᚱᚻᚦᛖ᛬ᛏᚩ᛬ᚻᛖᚩᚱᚪ᛬ᛋᛖᛚᚠᛖᛋ᛬ᛞᚩᚾ

Translation (Modern English)

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. (Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights)

Samples of spoken Old English

Information about Old English | Phrases | Numbers | Tower of Babel | Books and learning materials

Information provided by Niall Killoran

Information about Old English https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_English https://www.britannica.com/topic/Old-English-language https://oldenglish.info/ https://ancientlanguage.com/old-english/ https://www.thehistoryofenglish.com/history_old.html https://lrc.la.utexas.edu/eieol/engol

Old English lessons http://www.jebbo.co.uk/learn-oe/contents.htm http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL9664A1E483AFCD12 https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCLnwScGuOxVlaN5aV9in9ag

Old English phrases http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Old_English/Phrases http://speaksaxon.blogspot.co.uk http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Appendix:Old_English_phrasebook#Old English https://babblelingua.com/useful-phrases-in-old-english/

Old English dictionaries http://lexicon.ff.cuni.cz/app/ http://oldenglishthesaurus.arts.gla.ac.uk/aboutoeonline.html

Old English - Modern English translator http://www.oldenglishtranslator.co.uk

Ða Engliscan Gesiðas - the society for people interested in all aspects of Anglo-Saxon language and culture: http://tha-engliscan-gesithas.org.uk/

Beowulf in Hypertext http://www.humanities.mcmaster.ca/~beowulf/

Recordings of Old English texts https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCc4039hpZ8rnV2ed9F2zPWg

ALPHABETUM - a Unicode font for ancient scripts, including Classical & Medieval Latin, Ancient Greek, Etruscan, Oscan, Umbrian, Faliscan, Messapic, Picene, Iberian, Celtiberian, Gothic, Runic, Old & Middle English, Hebrew, Sanskrit, Old Nordic, Ogham, Kharosthi, Glagolitic, Anatolian scripts, Phoenician, Brahmi, Imperial Aramaic, Old Turkic, Old Permic, Ugaritic, Linear B, Phaistos Disc, Meroitic, Coptic, Cypriot and Avestan. https://www.typofonts.com/alphabetum.html

Germanic languages

Afrikaans , Alsatian , Bavarian , Cimbrian , Danish , Dutch , Elfdalian , English , Faroese , Flemish , Frisian (East) , Frisian (North) , Frisian (Saterland) , Frisian (West) , German , Gothic , Gottscheerish , Gronings , Hunsrik , Icelandic , Limburgish , Low German , Luxembourgish , Mòcheno , Norn , Norwegian , Old English , Old Norse , Pennsylvania German , Ripuarian , Scots , Shetland(ic) , Stellingwarfs , Swabian , Swedish , Swiss German , Transylvanian Saxon , Värmlandic , Wymysorys , Yiddish , Yola , Zeelandic

Languages written with the Latin alphabet

CustomWritingPro offers a wide range of essay writing services online.

Page last modified: 28.02.24

728x90 (Best VPN)

Why not share this page:

If you like this site and find it useful, you can support it by making a donation via PayPal or Patreon , or by contributing in other ways . Omniglot is how I make my living.

Get a 30-day Free Trial of Amazon Prime (UK)

If you're looking for home or car insurance in the UK, why not try Policy Expert ?

- Learn languages quickly

- One-to-one Chinese lessons

- Learn languages with Varsity Tutors

- Green Web Hosting

- Daily bite-size stories in Mandarin

- EnglishScore Tutors

- English Like a Native

- Learn French Online

- Learn languages with MosaLingua

- Learn languages with Ling

- Find Visa information for all countries

- Writing systems

- Con-scripts

- Useful phrases

- Language learning

- Multilingual pages

- Advertising

Unconventional language hacking tips from Benny the Irish polyglot; travelling the world to learn languages to fluency and beyond!

Looking for something? Use the search field below.

Home » Articles » Old English Writing: A History of the Old English Alphabet

Full disclosure: This post contains affiliate links. ?

written by George Julian

Language: English

Reading time: 13 minutes

Published: Jan 12, 2018

Updated: Sep 17, 2021

Old English Writing: A History of the Old English Alphabet

Can you read Old English writing? Here's a sample:

Nu scylun hergan hefaenricaes uard metudæs maecti end his modgidanc uerc uuldurfadur sue he uundra gihuaes eci dryctin or astelidæ

Those are the first few lines of Cædmon's Hymn , a 7th-Century poem generally considered to be the oldest surviving work of English literature. Any idea what it means?

Me neither. Let's look at the modern translation:

Now shall we praise the Warden of Heaven-Kingdom the might of the Measurer and his purpose work of the Wulder-Father as he of wonders Eternal Lord the beginning created

Separated by more than a millennium, these two texts are barely recognisable as the “same” language. Only two words appear unchanged: he and his . A few other connections shine faintly through, like hefaen for heaven , fadur for father , and uerc for work , but I can’t glean much else… and even in the modern version, I still have no idea what a “Wulder-father” is.

There's no doubt about it: Old and Modern English might as well be two completely different languages. Cædmon's Hymn is utterly incomprehensible to the modern English reader.

(See here for an audio version of the original hymn.)

“Old English” is a broad topic. For this article I'll focus on the history of Old English writing . How was Old English written? How did it change as we shifted into middle and more modern dialects? Why doesn't “count” rhyme with the first syllable of “country”? And why do we continue to torture ESL students with bizarrities like the sentence “a rough coughing thoughtful ploughman from Scarborough bought tough dough in Slough”?

Below, I'll explore all these questions, and also tell you why you're probably pronouncing the word “ye” wrong.

But first, a short history lesson about Old English:

A Brief History of “Englisc”

English is a Germanic language, meaning its closest living relatives are Dutch, Frisian, and of course German. The Germanic family, however, is just one branch of the wider Indo-European language family. Other Indo-European branches include Slavic, Italic, and Celtic.

English originated in the area now called England (duh), but it wasn’t the first language to get here. Before English came along, most people in the British Isles spoke Celtic languages, a family whose modern descendants include Irish and Welsh.

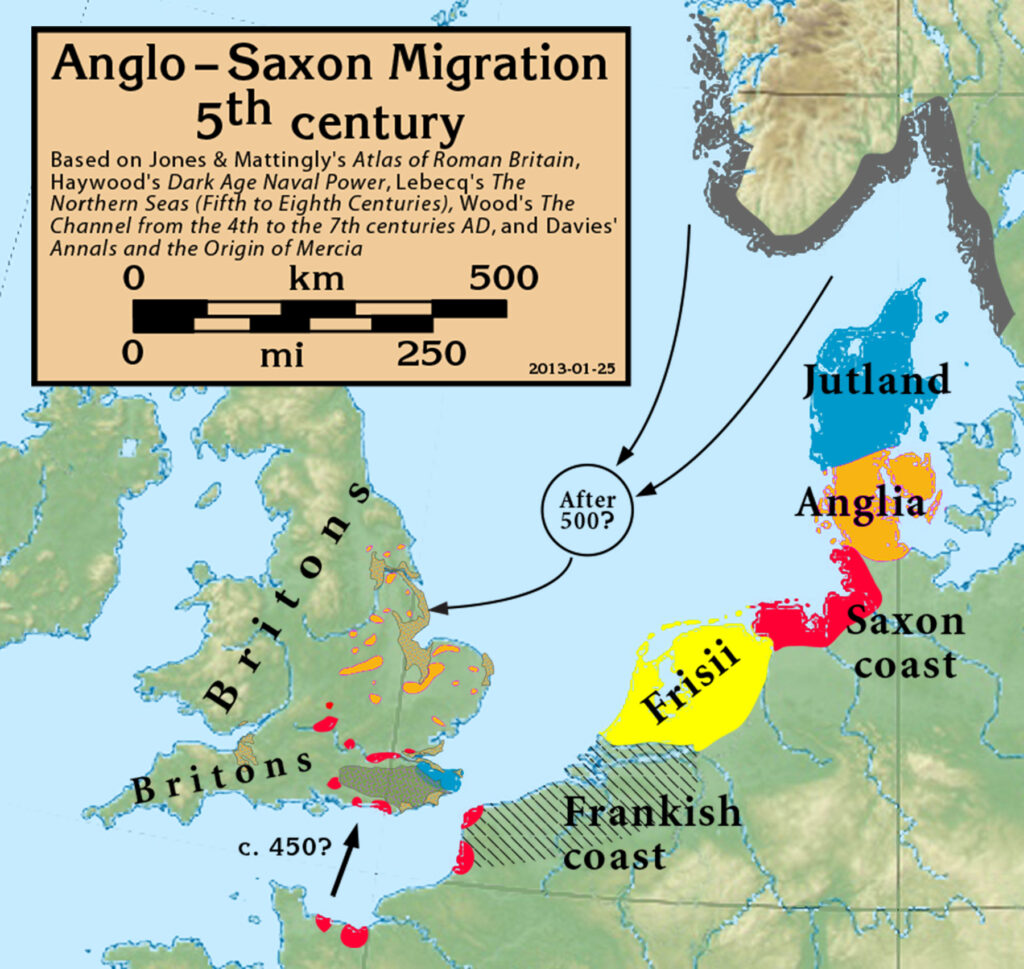

Throughout the first millennium AD, the Celtic-speakers of Britain were slowly displaced by waves of immigration and invasion from the European mainland. Groups like the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Danes and Frisians sailed to and settled in Britain, bringing their Germanic languages with them.

For obvious geographical reasons, these invaders mainly came from the southeast. That's why the few Celtic languages that remain in the British Isles today (Cornish, Welsh, Irish and Scottish Gaelic ) are only found in the archipelago’s northern and western extremities. Meanwhile, the various Germanic dialects slowly merged into a new language that its speakers called Englisc .

It was roundabout this time that Cædmon (his name is pronounced roughly like “CAD-mon”) composed his hymn.

Old English Runes – found in Ruins

“Hold on a minute” , I hear someone say. “Apart from the weird “æ”, that hymn is written using modern English letters. I thought the Old English alphabet used cool runic characters, kind of like what the dwarves use in Lord of the Rings?”

You're right. (Where do you think Tolkien got the idea from?)

You’re reading this article in the Latin alphabet, but English wasn't always written like this. Before the current writing system was introduced to Britain by Christian missionaries in the 9th and 10th centuries, English was primarily written with Anglo-Saxon runes .

The Old English Alphabet

The Old English alphabet looked like this:

This alphabet is also sometimes called the futhorc , from the pronunciation of its first six letters.

Some experts think that the futhorc was brought to the British Isles by immigrants from Frisia (the northern Netherlands). Another theory is that they came here from Scandinavia, then were taken to Frisia in the other direction.

What we know for sure is that the first runic inscriptions started showing up in Britain around the 5th century A.D.. The oldest known piece of written English is the Undley Bracteate , a gold medallion with a runic inscription that reads “this she-wolf is a reward to my kinsman.” Another example is the Franks Casket , a whalebone chest from the north of England that’s been dated to the 8th century:

By the 11th century, the futhorc resembled one of the Tolkien novels that it inspired: lots of dead characters. But while most runes fell into disuse, a few survived and were mixed in with the newer writing system.

A “Thorny Problem” with Old English Runes

The following is an extract from the poem The Battle of Maldon , thought to be written shortly after the titular battle of 991 AD:

Brimmanna boda, abeod eft ongean, sege þinum leodum miccle laþre spell, þæt her stynt unforcuð eorl mid his werode, þe wile gealgean eþel þysne

What are those funny “þ” and “ð” characters?

The former, called thorn , is a rune that stayed in use even after most other runes had been forgotten. The latter, called eth , is a modification of the Latin letter d . Both are pronounced like the modern “th” sound(s). So þæt means “that”, þe means “the”, and I have no idea what unforcuð means, but I imagine it was pronounced something like “un-for-kuth”.

(You can read a modern translation of The Battle of Maldon here .)

The rune ƿ (“wynn”) also survived longer than most, used to represent the sound that we now write as “w”. Eventually ƿ was replaced with “uu”, which was then simplified to “w”, which explains why “w” is called “double-u”.

If you speak a modern Latin language like Spanish, you’ll know that they generally don’t use “w”, except in foreign words and names like Washington . This is because “w” didn’t exist in the Latin alphabet; it’s a more recent innovation from English and other northern European languages.

Still, The Battle of Maldon is not much easier to understand than Caedmon’s Hymn .

Thanks to Runes, You're Saying “Ye” Wrong

Runes that have filtered down into “Latin” English can mean that even today we pronounce some English words incorrectly.

There's a trope in the English-speaking world of writing “ye olde [something]” when you want the name of that something to sound old-timey or Medieval. For example, you might see a pub called “Ye Olde Pubbe”.

There are two problems with this. First of all, the world olde is (ironically) a modern invention. “Old” was never written like that in historical English.

Secondly, when modern speakers read the “ye” of “ye olde”, they usually pronounce it like it's written, with a “y” sound. This isn’t how Old English speakers would have said it! If you said “ye” like this to an 11th-Century Englishman, they’d understand it as a plural form of you ; this sense lives on in archaic expressions like “hear ye”.

The misconception stems from the fact that the word “the” was once written as “þe”, using the “thorn” rune. A handwritten “þ” sometimes looked like a “y”. More importantly, Medieval printing presses didn’t have a “þ” character, so they substituted in “y” instead. So when they printed ye , they were actually writing the .

So, the correct way to pronounce “ye olde pubbe” is in fact simply “ the old pub”.

How Old English was Changed Forever by Norman Nobles

Have you noticed how many words English has?

Why do comprehend , respire and azure need to exist when we already have understand , breathe , and blue ?

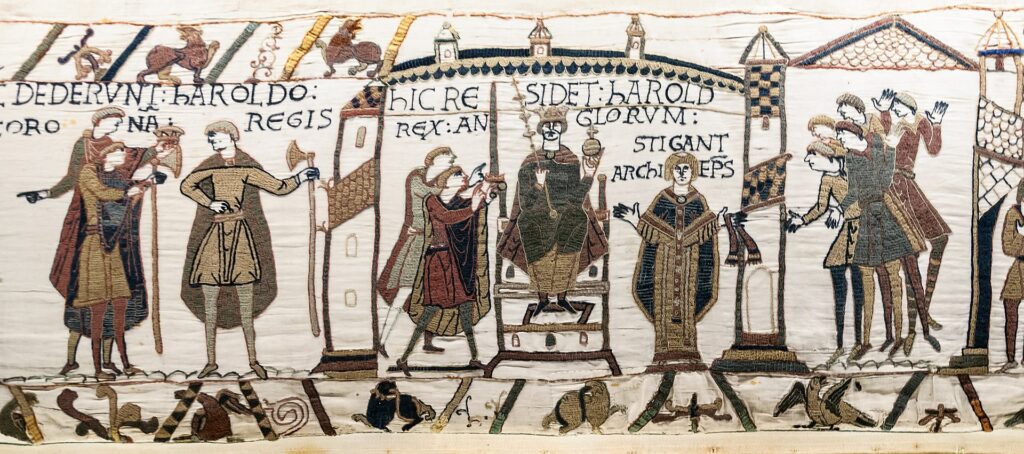

To answer this question, we must go all the way back to the year 1066. As every Brit learns in school, that was the year when William of Normandy, claiming to be the rightful king of England (it was a family matter) sailed across the English Channel, killed his rival Harold in battle, and installed himself on the throne.

With the Normans in charge of England, their dialect of French became the language of nobility. To this day, the British parliament still uses Norman French for certain official purposes.

Meanwhile, the plebeians and riff-raff continued to speak Englisc . The two languages merged over time, but we’re still living with the consequences: fancy words like comprehend and respire have their roots in Latin (via Norman French), while their more common synonyms like understand and breathe are the “original” English words, Germanic in origin.

(Fun fact: despite the French on their tongues, the Normans were actually Vikings who had settled in France; the name “Norman” comes from “North-man”. For some reason they lost their original language and picked up one of the local dialects instead, but the more interesting point is that the modern British royal family are directly descended from the same Norman nobles who conquered England in 1066. You heard it right: Queen Elizabeth II is a Viking.)

As well as introducing new vocabulary, the Normans also changed the spelling of some words. For example, the Old English hwaer , hwil and hwaenne became where , when and while , even though the “hw-” spelling more accurately reflected the pronunciation.

Some English speakers, particularly in parts of the U.S., still pronounce words like where with an “h” sound at the beginning – listen to how Johnny Cash says the word “white” at about 0:14 in The Man Comes Around . It’s been nearly 1,000 years, and we still haven’t recovered from this weird spelling change.

And as anyone remotely literate in English knows, when it comes to weird spelling, “white” is just the tip of the iceberg.

From Old English to Middle English

Linguists generally mark the Norman Conquest as the dividing line between Old and Middle English. Within a few centuries, English was finally starting to resemble the language we speak today:

A monk ther was, a fair for the maistrye An out-rydere, that lovede venerye; A manly man, to been an abbot able. Ful many a deyntee hors hadde he in stable

That’s from from The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, probably the most famous work of pre-Shakespearean English literature, and a well-known example of (Late) Middle English.

And it’s readable! The spelling is weird, and I don't know what venerye or “maistrye” are, but for the most part I can understand Chaucer without having to search Google for a modern translation.

The Canterbury Tales were written at the tail-end of the 14th Century, a time when English spelling varied widely from place to place. Why wouldn’t it? When you rarely communicate with people who live far away, and you pronounce things differently from them anyway, there’s not much incentive for everybody to try and spell things the same way. All that started to change, however, in the late 15th Century, thanks to an important new invention: the printing press.

As it became easier to put English to paper and to disseminate it widely, local variations in spelling were slowly ironed out. But who got to decide which spelling was “correct”? The answer: no-one. Publishers in different parts of the country used spellings that reflected their local pronunciations and biases. Some spellings caught on nationally, others didn’t, and the emerging “standard” system of English spelling picked up words from all over the place and became full of inconsistencies.

These inconsistencies persist to this day, and have only got worse as pronunciation has changed further. You can see this, for example, in the works of Shakespeare. Shakespeare rhymed “sword” with “word”, to give just one example – it made sense at the time, but since then the pronunciations have split. Even then, we haven’t bothered to update the spelling, so “sword” and “word” still look like they should rhyme.

(Some troupes now put on productions of Shakespeare using the original Elizabethan pronunciation , a delight for language nerds like myself.)

There was also a fad in some parts for using spellings that reflected not a word’s pronunciation but its etymology. So for example, “debt” gained its silent “b”, reflecting its origins in the Latin debitum .

Similarly, the Middle English word “iland” gained a silent “s” in order to make it closer to the French isle (and the Latin insula ). This was actually a mistake: iland was a Germanic word, and its resemblance to French and Latin is just a coincidence. 500 years later, the misconception remains uncorrected.

Even more unfortunately for modern learners of English, the advent of the printing press happened at a time when English pronunciation was changing rapidly. Modern linguists call it the Great Vowel Shift . Over a period of a few hundred years, the pronunciations of most English vowels changed dramatically, at the exact same time that their spellings were becoming set in stone.

And so in the 21st century, English spelling makes so little sense that even native speakers can struggle.

- Why don’t “stove”, “love” and “move” rhyme with each other?

- Why is “trollies” the plural of “trolley”, but the plural of “monkey” isn’t “monkies”?

- Why is it “i before e, except after c”… and except in science , receive , species , sufficient , vein , feisty , foreign , or ceiling ?

Hell, we don’t even write our language's name in a way that makes sense. Shouldn’t it be “Inglish”?

I wonder what the total economic cost is of all this madness? How much time and energy are wasted on schooling children, reprinting documents with errors, and pedantically correcting people who write “sneak peak” or “wrecking havoc”?

It shouldn't have to be like this. Is there any way out of this mess? We’ll see.

English Writing: A Standard Way of Spelling?

There have been many attempts to reform English spelling, and some have even been successful: when Noah Webster published his dictionaries in the 19th Century, he made several proposals for new spellings. Some, like the idea to drop the “k” from “publick” and “musick”, caught on. Others, like the suggestion to remove the “u” from “colour” and “humour”, only gained traction on one side of the Atlantic. Many of his other proposals didn’t catch on at all , and English remains full of oddities.

Reform isn’t impossible. The German-speaking countries managed to do it in the 1990s, slightly simplifying the spelling of some German words and making the new orthography compulsory in government documents and schools. More recently, the CPLP (Community of Portuguese Language Countries) passed a similar reform, which is still being implemented in Portuguese-speaking countries today.

In the English-speaking world, however, it’s unlikely that we’ll muster the will to change our spelling any time soon. One problem is that we don’t have an official body like the CPLP that has any influence over the language. Another problem is that there are there are just too many English speakers, spread across too many countries, with too many variations in pronunciation. No-one would ever agree on what the “correct” new spellings should be.

But the biggest barrier of all is that most people don’t care. In fact, many native English speakers are proud of the difficulty of English spelling; it’s seen as an intellectual achievement to master it all. And of course, people who have already learned all the current spellings don’t want to go through the bother of learning them all again.

For now, English spelling is one of those things like the QWERTY keyboard, or the fact that different countries drive on different sides of the road. It’s not ideal, and if we could start over we’d probably do things differently, but it’s just not worth the effort to fix. There are more important problems to worry about.

So it seems that for now, we’re stuck with that “rough coughing thoughtful ploughman”. And it’s been a hell of a journey to get here.

George Julian

Content Writer, Fluent in 3 Months

George is a polyglot, linguistics nerd and travel enthusiast from the U.K. He speaks four languages and has dabbled in another five, and has been to more than forty countries. He currently lives in London.

Speaks: English, French, Spanish, German, Vietnamese, Portuguese

Have a 15-minute conversation in your new language after 90 days

Old English and Anglo Saxon

The Origins of Modern English

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Old English was the language spoken in England from roughly 500 to 1100 CE. It is one of the Germanic languages derived from a prehistoric Common Germanic originally spoken in southern Scandinavia and the northernmost parts of Germany. Old English is also known as Anglo-Saxon, which is derived from the names of two Germanic tribes that invaded England during the fifth century. The most famous work of Old English literature is the epic poem, " Beowulf ."

Example of Old English

The Lord's Prayer (Our Father) Fæder ure ðu ðe eart on heofenum si ðin nama gehalgod to-becume ðin rice geweorþe ðin willa on eorðan swa swa on heofenum. Urne ge dæghwamlican hlaf syle us to-deag and forgyf us ure gyltas swa swa we forgifaþ urum gyltendum ane ne gelæde ðu us on costnunge ac alys us of yfle.

On Old English Vocabulary

"The extent to which the Anglo-Saxons overwhelmed the native Britons is illustrated in their vocabulary ... Old English (the name scholars give to the English of the Anglo-Saxons) contains barely a dozen Celtic words... It is impossible...to write a modern English sentence without using a feast of Anglo-Saxon words. Computer analysis of the language has shown that the 100 most common words in English are all of Anglo-Saxon origin. The basic building blocks of an English sentence— the, is, you and so on—are Anglo-Saxon. Some Old English words like mann, hus and drincan hardly need translation." —From "The Story of English" by Robert McCrum, William Cram, and Robert MacNeill

"It has been estimated that only about 3 percent of Old English vocabulary is taken from non-native sources and it is clear that the strong preference in Old English was to use its native resources in order to create new vocabulary. In this respect, therefore, and as elsewhere, Old English is typically Germanic." —From "An Introduction to Old English" by Richard M. Hogg and Rhona Alcorn

"Although contact with other languages has radically altered the nature of its vocabulary, English today remains a Germanic language at its core. The words that describe family relationships— father, mother, brother, son —are of Old English descent (compare Modern German Vater, Mutter, Bruder, Sohn ), as are the terms for body parts, such as foot, finger, shoulder (German Fuß, Finger, Schulter ), and numerals, one, two, three, four, five (German eins, zwei, drei, vier, fünf ) as well as its grammatical words , such as and, for, I (German und, für, Ich )." —From "How English Became English" by Simon Horobin

On Old English and Old Norse Grammar

"Languages which make extensive use of prepositions and auxiliary verbs and depend upon word order to show other relationships are known as analytic languages. Modern English is an analytic, Old English a synthetic language. In its grammar , Old English resembles modern German. Theoretically, the noun and adjective are inflected for four cases in the singular and four in the plural, although the forms are not always distinctive, and in addition the adjective has separate forms for each of the three genders . The inflection of the verb is less elaborate than that of the Latin verb, but there are distinctive endings for the different persons , numbers , tenses , and moods ." —From "A History of the English Language" by A. C. Baugh

"Even before the arrival of the Normans [in 1066], Old English was changing. In the Danelaw, the Old Norse of the Viking settlers was combining with the Old English of the Anglo-Saxons in new and interesting ways. In the poem, 'The Battle of Maldon,' grammatical confusion in the speech of one of the Viking characters has been interpreted by some commentators as an attempt to represent an Old Norse speaker struggling with Old English. The languages were closely related, and both relied very much on the endings of words—what we call 'inflections'—to signal grammatical information. Often these grammatical inflexions were the main thing that distinguished otherwise similar words in Old English and Old Norse.

"For example, the word 'worm' or 'serpent' used as the object of a sentence would have been orminn in Old Norse, and simply wyrm in Old English. The result was that as the two communities strove to communicate with each other, the inflexions became blurred and eventually disappeared. The grammatical information that they signaled had to be expressed using different resources, and so the nature of the English language began to change. New reliance was put on the order of words and on the meanings of little grammatical words like to, with, in, over , and around ." —From "Beginning Old English" by Carole Hough and John Corbett

On Old English and the Alphabet

"The success of English was all the more surprising in that it was not really a written language, not at first. The Anglo-Saxons used a runic alphabet , the kind of writing J.R.R. Tolkien recreated for 'The Lord of the Rings,' and one more suitable for stone inscriptions than shopping lists. It took the arrival of Christianity to spread literacy and to produce the letters of an alphabet which, with a very few differences, is still in use today." —From "The Story of English" by Philip Gooden

Differences Between Old English and Modern English

"There is no point...in playing down the differences between Old and Modern English, for they are obvious at a glance. The rules for spelling Old English were different from the rules for spelling Modern English, and that accounts for some of the difference. But there are more substantial changes as well. The three vowels that appeared in the inflectional endings of Old English words were reduced to one in Middle English, and then most inflectional endings disappeared entirely. Most case distinctions were lost; so were most of the endings added to verbs, even while the verb system became more complex, adding such features as a future tense , a perfect and a pluperfect . While the number of endings was reduced, the order of elements within clauses and sentences became more fixed, so that (for example) it came to sound archaic and awkward to place an object before the verb, as Old English had frequently done." —From "Introduction to Old English" by Peter S. Baker

Celtic Influence on English

"In linguistic terms, obvious Celtic influence on English was minimal, except for place-and river-names ... Latin influence was much more important, particularly for vocabulary... However, recent work has revived the suggestion that Celtic may have had considerable effect on low-status, spoken varieties of Old English, effects which only became evident in the morphology and syntax of written English after the Old English period... Advocates of this still-controversial approach variously provide some striking evidence of coincidence of forms between Celtic languages and English, a historical framework for contact, parallels from modern creole studies, and—sometimes—the suggestion that Celtic influence has been systematically downplayed because of a lingering Victorian concept of condescending English nationalism." —From "A History of the English Language" by David Denison and Richard Hogg

English Language History Resources

- English Language

- Key Events in the History of the English Language

- Language Contact

- Middle English

- Modern English

- Spoken English

- Written English

- McCrum, Robert; Cram, William; MacNeill, Robert. "The Story of English." Viking. 1986

- Hogg, Richard M.; Alcorn, Rhona. "An Introduction to Old English," Second Edition. Edinburgh University Press. 2012

- Horobin, Simon. "How English Became English." Oxford University Press. 2016

- Baugh, A. C. "A History of the English Language," Third Edition. Routledge. 1978

- Hough, Carole; Corbett, John. "Beginning Old English," Second Edition. Palgrave Macmillan. 2013

- Gooden, Philip. "The Story of English." Quercus. 2009

- Baker, Peter S. "Introduction to Old English." Wiley-Blackwell. 2003

- Denison, David; Hogg, Richard. "Overview" in "A History of the English Language." Cambridge University Press. 2008.

- Middle English Language Explained

- What Are the Letters of the Alphabet?

- Word Order in English Sentences

- Inflection Definition and Examples in English Grammar

- What is Vocabulary in Grammar?

- New Englishes: Adapting the Language to Meet New Needs

- What Are Irregular Verbs in English?

- What Words Are False Friends?

- Third-Person Pronouns

- A Linguistic Look at Spanish

- Inflectional Morphology

- Regular Verbs: A Simple Conjugation

- What Is American English (AmE)?

- etymology (words)

- Examples of Linguistic Mutation

Keep dead languages alive

We need your help to preserve & document ancient languages. Participate today.

Old English Online

Series introduction, jonathan slocum and winfred p. lehmann.

All lessons now include audio!

Recorded by Thomas M. Cable , Professor Emeritus of the University of Texas at Austin.

Old English is the language of the Germanic inhabitants of England, dated from the time of their settlement in the 5th century to the end of the 11th century. It is also referred to as Anglo-Saxon, a name given in contrast with the Old Saxon of the inhabitants of northern Germany; these are two of the dialects of West Germanic, along with Old Frisian, Old Franconian, and Old High German. Sister families to West Germanic are North Germanic, with Old Norse (a.k.a. Old Icelandic) as its chief dialect, and East Germanic, with Gothic as its chief (and only attested) dialect. The Germanic parent language of these three families, referred to as Proto-Germanic, is not attested but may be reconstructed from evidence within the families, such as provided by Old English texts.

Old English itself has three dialects: West Saxon, Kentish, and Anglian. West Saxon was the language of Alfred the Great (871-901) and therefore achieved the greatest prominence; accordingly, the chief Old English texts have survived in this dialect. In the course of time, Old English underwent various changes such as the loss of final syllables, which also led to simplification of the morphology. Upon the conquest of England by the Normans in 1066, numerous words came to be adopted from French and, subsequently, also from Latin.

For a reconstruction of the parent language of Old English, called Proto-Germanic, see Winfred Lehmann's book on this subject. For access to our online version of Bosworth and Toller's dictionary of Old English, see An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary .

Note: this page is for systems/browsers with Unicode ® support and fonts spanning the Unicode 3 character set relevant to Old English. Versions of this page rendered in alternate character sets are available via links ( Romanized and Unicode 2 ) in the left margin, and at the bottom of this page.

Alphabet and Pronunciation

The alphabet used to write our Old English texts was adopted from Latin, which was introduced by Christian missionaries. Unfortunately, for the beginning student, spelling was never fully standardized: instead the alphabet, with continental values (sounds), was used by scribal monks to spell words "phonetically" with the result that each dialect, with its different sounds, was rendered differently -- and inconsistently, over time, due to dialectal evolution and/or scribal differences. King Alfred did attempt to regularize spelling in the 9th century, but by the 11th century continued changes in pronunciation once again exerted their disruptive effects on spelling. In modern transcriptions such as ours, editors often add diacritics to signal vowel pronunciation, though seldom more than macrons (long marks).

Anglo-Saxon scribes added two consonants to the Latin alphabet to render the th sounds: first the runic thorn ( þ ), and later eth ( ð ). However, there was never a consistent distinction between them as their modern IPA equivalents might suggest: different instances of the same word might use þ in one place and ð in another. We follow the practices of our sources in our textual transcriptions, but our dictionary forms tend to standardize on either þ or ð -- mostly the latter, though it depends on the word. To help reduce confusion, we sort these letters indistinguishably, after T; the reader should not infer any particular difference. Another added letter was the ligature ash ( æ ), used to represent the broad vowel sound now rendered by 'a' in, e.g., the word fast . A letter wynn was also added, to represent the English w sound, but it looks so much like thorn that modern transcriptions replace it with the more familiar 'w' to eliminate confusion.

The nature of non-standardized Anglo-Saxon spelling does offer compensation: no letters were "silent" (i.e., all were pronounced), and phonetic spelling helps identify and track dialectal differences through time. While the latter is not always relevant to the beginning student, it is nevertheless important to philologists and others interested in dialects and the evolution of the early English language.

At first glance, Old English texts may look decidedly strange to a modern English speaker: many Old English words are no longer used in modern English, and the inflectional structure was far more rich than is true of its modern descendant. However, with small spelling differences and sometimes minor meaning changes, many of the most common words in Old and modern English are the same. For example, over 50 percent of the thousand most common words in Old English survive today -- and more than 75 percent of the top hundred. Conversely, more than 80 percent of the thousand most common words in modern English come from Old English. A few "teaser" examples appear below; our Master Glossary or Base-Form Dictionary may be scanned for examples drawn from our texts, and any modern English dictionary that includes etymologies will provide hundreds or thousands more.

- Nouns: cynn 'kin', hand , god , man(n) , word .

- Pronouns: hē , ic 'I', mē , self , wē .

- Verbs: beran 'bear', cuman 'come', dyde 'did', sittan 'sit', wæs 'was'.

- Adjectives: fæst 'fast', gōd 'good', hālig 'holy', rīce 'rich', wīd 'wide'.

- Adverbs: ær 'ere', alle 'all', nū 'now', tō 'too', ðǣr 'there'.

- Prepositions: æfter 'after', for , in , on , under .

- Articles: ðæt 'that', ðis 'this'.

- Conjunctions: and , gif 'if'.

Sentence Structure

In theory, Old English was a "synthetic" language, meaning inflectional endings signalled grammatical structure and word order was rather free, as for example in Latin; modern English, by contrast, is an "analytic" language, meaning word order is much more constrained (e.g., with clauses typically in Subject-Verb-Object order). But in practice, actual word order in Old English prose is not too often very different from that of modern English, with the chief differences being the positions of verbs (which might be moved, e.g., to the end of a clause for emphasis) and occasionally prepositions (which might become "postpositions"). In Old English verse, most bets are off: word order becomes much more free, and word inflections & meaning become even more important for deducing syntax. The same may be said, however, of modern English poetry, but in these lessons we tend to translate Old English poetry as prose. Altogether, once a modern English reader has mastered the common vocabulary and inflectional endings of Old English, the barriers to text comprehension are substantially reduced.

As we will see, Old English words were much inflected. Over time, most of this apparatus was lost and English became the analytic language we recognize today, but to read early English texts one must master the conjugations of verbs and the declensions of nouns, etc. Yet these inflectional systems had already been reduced by the time Old English was first being written, long after it had parted ways with its Proto-Germanic ancestor. The observation that matters "could have been worse" should serve as consolation to any modern English student who views conjugation and declension with trepidation.

Nouns, adjectives, and pronouns

These categories of Old English words are declined according to case (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, or sometimes instrumental), number (singular, plural, or [for pronouns] dual meaning 'two'), and gender (masculine, feminine, or neuter: inherent in nouns, but inherited by adjectives and pronouns from the nouns they associate with). In addition, some adjectives are inflected to distinguish comparative and superlative uses.

Adjectives and regular nouns are either "strong" or "weak" in declension. In addition, irregular nouns belong to classes that reflect their earlier Germanic or even Indo-European roots; these classes, or more to the point their progenitors, will not be stressed in our lessons, but descriptions are found in the handbooks.

Pronouns are typically suppletive in their declension, meaning inflectional rules do not account for many forms so each form must be memorized (as is true of modern English I/me , you , he/she/it/his/her , etc). Tables will be provided. Similarly, a few nouns and adjectives are "indeclinable" and, again, some or all forms must be memorized.

Old English verbs are conjugated according to person (1st, 2nd, or 3rd), number (singular or plural), tense (present or past/preterite), mood (indicative, imperative, subjunctive or perhaps optative), etc.

Most verbs are either "strong" or "weak" in conjugation; there are seven classes of strong verbs and three classes of weak verbs. A few other verbs, including modals (e.g. for 'can', 'must'), belong to a special category called "preterit-present," where different rules apply, and yet others (e.g. for 'be', 'do', 'go') are "anomalous," meaning each form must be memorized (as is true of modern English am/are/is , do/did , go/went , etc).

Other parts of speech

The numerals may be declined, albeit with fewer distinct forms than is normal for adjectives, and those for 'two' and 'three' may show gender. Other parts of speech are not inflected, except for some adverbs with comparative and superlative forms.

Lesson Recordings

This lesson series features audio recitations of each lesson text, accessible by clicking on the speaker icon (🔊) beside corresponding text sections. Prof. Thomas Cable, Emeritus, dedicated countless hours to the preparation and recording of these texts. The Linguistics Research Center is immensely grateful for Prof. Cable's generosity, patience, and good humor throughout the entire process.

Related Language Courses at UT

Most but not all language courses taught at The University of Texas concern modern languages; however, courses in Old and Middle English, at both the undergraduate and graduate levels, are taught in the Department of English (link opens in a new browser window). Other online language courses for college credit are offered through the University Extension (new window).

West Germanic Resources Elsewhere

Our Links page includes pointers to West Germanic resources elsewhere.

The Old English Lessons

- Beowulf: Prologue

- Bede's Account of the Poet Caedmon

- Cynewulf and Cyneheard

- Voyages of Ohthere and Wulfstan

- Alfred's Wars with the Danes

- The Battle of Maldon

- Genesis A: the Flood

- The Wanderer

- The Seafarer

- Beowulf: the Funeral

- Show full Table of Contents with Grammar Points index

- Open a Master Glossary window for these English texts

- Open a Base Form Dictionary window for these English texts

- Open an English Meaning Index window for these English texts

first lesson | next lesson

- Armenian - Romanized

- Old English

- N. T. Greek

- Old Iranian

- Old Russian

- Old Slavonic

- Lesson Resources

- Printable Version

- English Glossary

- English Dictionary

- English Meanings

Linguistics Research Center

University of Texas at Austin PCL 5.556 Mailcode S5490 Austin, Texas 78712 512-471-4566

- Linguistics Research Center Social Media

- Facebook Twitter

For comments and inquiries, or to report issues, please contact the Web Master at [email protected]

- Make a Gift

- YouTube

- Flickr

- Prospective

- Undergraduate

The College of Liberal Arts The University of Texas at Austin 116 Inner Campus Dr Stop G6000 Austin , TX 78712

- General Inquiries: 512-471-4141 Student Inquiries: 512-471-4271

Departments

- African & African Diaspora Studies

- Air Force Science

- American Studies

- Anthropology

- Asian Studies

- French & Italian

- Geography & the Environment

- Germanic Studies

Initiatives

Administration.

- Linguistics

- Mexican American Latina/o Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Military Science

- Naval Science

- Religious Studies

- Rhetoric & Writing

- Slavic & Eurasian Studies

- Spanish & Portuguese

- Office of the Dean

- Academic Affairs

- Research & Graduate Studies

- Student Affairs

- Business Affairs

- Human Resources

- Alumni & Giving

- Public Affairs

- LAITS: IT & Facilities

- The University of Texas at Austin 116 Inner Campus Dr Stop G6000 Austin, TX 78712

Web Privacy Policy Web Accessibility Policy © Copyright 2024

O ld English is the ancestor of modern English and was spoken in early medieval England. This website is designed to help you read Old English, whether you are a complete beginner or an advanced learner. It will introduce you, topic by topic, to the structure and sound of the Old English language in easy to digest chunks with plenty of opportunity to practice along the way.

Start from the Beginning

If you are new to Old English, or just want to begin with the basics, you should start here!

See the Course Index

If you need to review a specific topic, you can choose modules directly from the Course Index.

History of Old English

New to Old English and looking for a background to the language? You'll find it here.

Old English

Everything you need to learn old english.

Do you want to know the language of the Anglo-Saxons?

Want to read Beowulf – in the original?

Wish you could recite the Old English version of the Lord’s Prayer?

Maybe you just want to learn how to pronounce the letter þ (thorn)?

Whatever you want to do, you will find, below, everything you need to get started learning Old English , from the historical origins of the English language, to the basics of Old English pronunciation and grammar, to information about the Old English classes we offer at the Ancient Language Institute.

Let’s get started.

Table of Contents

The Origins of the English Language

The English language as we know it today is the product of a long history spanning thousands of years.

How did English get started? No one created the English language: it emerged between the 1st and 4th centuries AD out of a group of dialects spoken along the coast of the North Sea, in the western part of modern-day Denmark and the northwest coast of modern-day Germany. From there, it was carried into what we now call England in the 5th century AD by migrations of peoples known to history as the Angles, Saxons, and the Jutes.

It’s from the Angles that the English language gets its name. To distinguish this stage of the English language from those that came later, we call the language that the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes spoke “Old English,” or alternatively, “Anglo-Saxon.”

Once in England, this Old English language developed gradually into the Modern English we know today, although it changed a great deal along the way.

Is English a Germanic Language?

Yes, English is a Germanic language. That means it is related to the other Germanic languages. (What languages are Germanic? Some examples include German, Dutch, and the Scandinavian languages).

Why is English a Germanic language, especially since it looks and sounds so much more like a Romance language (i.e. a language descended from Latin, the language of the Romans)? Indeed, many of the words in English look a lot more like their French equivalents than their equivalents in German: compare English society with French société versus German Gesellschaft . It is true that only about 25% of the words in English are actually Germanic in origin. Despite this, we can still say that English is a Germanic language like German and not a Romance, or Latin-derived, language like French. Why?

Language relationships are not based solely on comparing the number of words that come from one language versus another. It matters how those words got into the language. Were they inherited, that is passed down from generation to generation all the way back into the mists of time? Or were they borrowed at some time in the past from another language?

Two friends could have the same hobbies, have the same job, have the same mannerisms, have the same style and presentation, and even split rent and have the same home address. They will likely resemble each other much more than either resembles his own uncle. But those friends are not in the same family, even though they may appear much more similar on the surface than a nephew and uncle do. Nevertheless, it’s the nephew and the uncle who are blood-related to each other.

Something like this happened with English and French. French moved into (well, invaded) England, and English ended up adopting tons of French words into its vocabulary. But English existed long before that happened, so even though its temporary French roommate rubbed off on English quite a bit, English didn’t become a Romance language. It just became a very French-looking Germanic language.

Languages, like people, are only “blood-related” when they spring from the same source. For people, you can trace two relatives’ ancestry back to the same person: a grandmother, a great-grandfather. For languages, it’s very similar: two languages are related if, as you go back through the generations, they become more and more similar until they reach a point where they are the same language.

For this reason, we can confidently say that English is a Germanic language.

Dr. Colin Gorrie , Old English & Latin Fellow of the Ancient Language Institute

These days, when Old English is taught at all, it’s typically taught by handing students a grammar book and a collection of texts and translating them by brute force. We know from our experience with Latin, Ancient Greek, and Biblical Hebrew that there is a better way to learn historical languages: through conversation and by reading level-appropriate texts. With ALI’s approach, you’ll be amazed at how quickly you’ll start to be able to understand Old English on its own terms. Beowulf awaits!

Old English Literature

Of the early Germanic languages, Old English is one of the earliest for which we have written texts. And we have lots of them, showing the literary wealth of Anglo-Saxon culture: over 400 manuscripts survive from the Anglo-Saxon period, which means that a student of Old English will not run out of reading material any time soon.

The people who wrote this literature are known to history as the Anglo-Saxons. Who were the Anglo-Saxons? They emerged from a group of Germanic tribes called the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes. They lived along the coast of the North Sea, in modern-Day Denmark and northwestern Germany, around the time of the fall of the western Roman Empire. When these peoples made their way to England they mixed together and developed a shared sense of cultural identity as “English”. Politically, they melded as well: faced with the need to defend against increasingly dangerous attacks from the Danes (the descendants of another Germanic people who stayed in Denmark – which is named after them – when the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes left), they developed a common sense of political identity as Anglo-Saxons.

Although vestiges of their pagan past linger in their literature, the Anglo-Saxons had become Christian by the seventh century, long before almost everything they wrote down: literacy had come along with Christianity. In those days, the ability to read and write was limited to a very small portion of the population: if you were literate in Anglo-Saxon England, you were almost certainly a monk or a student at a monastic school. Although most of what the Anglo-Saxons wrote was religious in character, we can’t define Anglo-Saxon literature exclusively in religious terms: secular texts existed too, in both poetry and prose.

Old English Poetry

Probably the most famous Old English text is a poem: this is Beowulf . Beowulf can be read in many ways: as a historical document of Anglo-Saxon hero culture, as a view into the complexity and contradictions of a Christian culture wrestling with its pagan past, or simply as a great adventure story.

The circumstances around Beowulf ’s composition are mysterious: it survives only in a single manuscript. After the Norman Conquest, it likely languished in some monastery library for hundreds of years, before being rediscovered by an Elizabethan collector named Sir Robert Cotton, whose collection (after surviving a fire) eventually became the foundation of the British Library. The manuscript seems to have been written in the early 11th century, but the language of the poem shows evidence of being older than that: based on some subtle details of how the poetry works, many scholars believe Beowulf was composed in the early 8th century. Although the version of Beowulf in the manuscript is written in the standard West Saxon dialect (as spoken around the capital, which was Winchester at the time), there are signs that the original was composed in Mercian, one of the other Old English dialects, this one spoken in the English Midlands.

For readers used to later forms of English poetry, such as the verse written by Chaucer or Shakespeare, Beowulf (and Old English poetry in general) often appears strange: instead of iambic pentameter ( e.g., Shall I compare thee to a Summers day? ), we get a line divided into two alliterating halves – each half had to contain words beginning with the same consonants – with a great variety of rhythms possible ( e.g., W eox under w olcnum || w eorðmyndum þah ; Þ eodcyninga || þ rym gefrunon ).

The requirement that both halves of a line must alliterate provides opportunities for a famous literary device of Old English poetry: the kenning . A kenning is a poetic circumlocution, a way of indirectly making reference to a thing or concept: for example, instead of sea , you might write whale-road . Instead of sun , you might say sky-candle . We still do this today occasionally: have you ever heard a raccoon called a trash-panda ? That’s a kenning too! Kennings gave Anglo-Saxon poets a chance to show off their creativity and at the same time choose a way referring to a thing that fit in with the alliteration each line required.

But Beowulf is not the only Old English poem worth reading. Another heroic poem, Genesis, tells the story of Satan’s war on Heaven and the Biblical story of the Fall of Man in the style of Old English heroic verse – like a pre-Miltonic Paradise Lost !

þa spræc se ofermoda cyning, þe ær wæs engla scynost, hwitost on heofne and his hearran leof, drihtne dyre, oð hie to dole wurdon, þæt him for galscipe god sylfa wearð mihtig on mode yrre.

Then spoke that berserker king, he who was before the most shining of angels, brightest in Heaven and beloved of his Leader, dear to the Lord, until he turned to folly thinking because of his desires that he could become God Himself, (tr. Oldrieve )

There are also beautiful elegiac poems such as The Wanderer and The Seafarer , which meditate on the fleeting nature of life. Here are a few lines from The Wanderer , in which a lonely exile recalls the days of his youth as a warrior in the service of his lord:

Hwær cwom mearg? Hwær cwom mago? Hwær cwom maþþumgyfa? Hwær cwom symbla gesetu? Hwær sindon seledreamas?

Where have the horses gone? where are the riders? where is the giver of gold? Where are the seats of the feast? where are the joys of the hall? (tr. Liuzza, 2014)

Old English Prose

Besides its poetry, Old English also has a rich corpus of prose in a variety of genres, both religious and secular. In the religious category, there are many homilies, biblical translations, and lives of saints to choose from.

Many religious texts were translated by King Alfred the Great (who reigned from 871–899), who wanted his subjects to be educated first in English rather than in Latin. For that reason, King Alfred himself wrote or commissioned Old English versions of what he saw to be the most important works of philosophy and religion: the Pastoral Care of Gregory the Great, Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy , the Soliloquies of St. Augustine, as well as the first fifty Psalms.

The Bible was never translated into Old English in its entirety: besides the partial translation of the Psalms attributed to King Alfred, we also have Old English translations of the four Gospels, the Hexateuch (Genesis through Joshua), and abridged translations of Judges, Kings, Job, Esther, Judith, and Maccabees. Doubtless there were other translations now lost to us. We know of one such lost translation in particular, a version of the Gospel of John translated by Bede, a monk who lived in Northern England in the 7th–8th centuries.

The source for all of these Old English translations was the Latin Vulgate. Here is a side-by-side example of one of the Ten Commandments in Latin, Old English, and the Early Modern English of the King James version:

Non habebis deos alienos coram me.

Ne lufa ðu oþre fremde godas ofer me.

(lit. Do not love other, foreign gods over me.)

Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

If you’re more interested in secular literature, there are historical works such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , which is a year-by-year record of events in the history of English. It is an extremely important source for historians studying the history of Anglo-Saxon England.

Other important prose works include technical manuals on mathematics, medicine, geography, and grammar, as well as a large selection of legal texts, including not only laws themselves, but also wills and records of legal cases, which give us a good view of what social life was like during Anglo-Saxon times.

Old English vs. Modern English

The language we know as Old English was never a static thing. Like all living languages, it changed from one generation to the next. The Old English spoken by the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes who came to England in the 5th century had changed a lot by the 11th century, but these changes were gradual and slow enough that we can think of the language as spoken from the 5th to the 11th centuries as Old English.

Here’s the introduction to Beowulf , a poem whose date of composition is uncertain but dates somewhere between the 8th and 11th centuries:

Hwæt. We Gardena in geardagum, þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon, hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon ( Beowulf 1–3)

As you can probably see, Old English is essentially a “foreign language” even for a native English speaker. The process that bridges Old English to Modern English took place over centuries. The political and linguistic situation changed dramatically when another group of people came to England in the year 1066: the Normans. The arrival of the Normans, who spoke an early form of French, marks the end of the Old English period. It wasn’t as if everyone radically changed their way of speaking in 1066. Gradual change went on as before, but English fell out of the historical record, as the Normans preferred to use their own scribes brought over from France, who spoke French, and wrote in either French or Latin. Although ordinary people kept speaking English, the upper classes were native French speakers for many generations. As a result, there were very few works written in English from the 12th until the 14th century, by which point the upper classes had largely assimilated to English culture.

By the time English started being widely written again in the 14th century, it now looked very different, as if all the changes of the intervening centuries showed up at once. We call this stage of the language Middle English. Since so much official business had been done in French, especially from the 11th to 14th centuries, many words from French found their way into English during this period as well. This is the period in which Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales . Looking at an excerpt from The Canterbury Tales allows us to see the degree to which French had begun to influence English:

Whan that Aprill , with his shoures soote The droghte of March hath perced to the roote And bathed every veyne in swich licour , Of which vertu engendred is the flour ; (General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales , 1–4)

Of the 30 words in this excerpt, the 8 words marked in boldface derive from French. That’s almost a quarter of the passage.

The Middle English period conventionally lasted from 1066 until the mid-16th century. What changed in the 16th century? The development of the printing press and the widespread publication of English versions of the Bible, which started to stabilize the written language. Although we often experience technological change as “speeding things up”, advances in communication technologies, such as printing, often “slow things down” in that they standardize and fossilize language.

Old English vs. Middle English vs. Modern English

If you’re wondering which of these terms corresponds to medieval English, you could say that both Old English and Middle English were medieval forms of the English language. If you assume the Middle Ages lasted from around AD 500 to 1500, Old English fits into the first half of that time period and Middle English fits into the second half.

If we keep that conventional division between ancient and medieval history in the year AD 500, only the very earliest forms of English could be called “ancient”. Since we don’t have almost any Old English writing until AD 650, information about this early “ancient” period in the history of English is very hazy, but very interesting to historical linguists.

By the 16th century, however, the language spoken in England had begun to look a lot like our own: for this reason, this period in the history of English is called Early Modern English. This is the language of Shakespeare:

Shall I compare thee to a Summers day? Thou art more louely and more temperate: Rough windes do shake the darling buds of Maie, And Sommers lease hath all too short a date: ( Sonnet 18)

It is a popular misconception that Old English is the language Shakespeare wrote in. Although Shakespeare’s English is old – he wrote 400 years ago – Old English is much older than Shakespeare’s English. Shakespeare’s language has a great deal more in common with our own English than with the English of Beowulf . This is why we can expect high school students to read Shakespeare’s plays with nothing but a glossary to help clarify some archaic words, but Old English requires a whole course of study: for all practical purposes, it’s a foreign language.

It’s only in the past two centuries that Old English has begun to be studied again by scholars and by others with an interest in the language, literature, and culture of the early Middle Ages in England.

Old English Grammar

For a speaker of Modern English, Old English is a fascinating mixture of the strange and the familiar. Many words in Old English look identical, or at least very close, to their modern equivalents: land means ‘land’, folc means ‘folk’, wel means ‘well’.

But other words, like wæstm (meaning ‘fruit’) or þearf (meaning ‘need’) give us no clues, not to mention the fact that they’re written with unfamiliar letters. And when it comes to grammar, Old English looks stranger still to the speaker of Modern English. Let’s take a look at some of the ways Old English differs from Modern English.

What Is Old English?

The biggest difference between Old English and Modern English is that Old English is an inflected language.

Unlike Modern English, which tends not to change the forms of words in order to fit them into a sentence, Old English words often look quite different depending on the sentence they appear in.

For example, the word “king” doesn’t change its form or spelling depending on its grammatical use:

The king is here. ( king = subject)

I gave the king the sword. ( king = indirect object)

But, in the equivalent Old English sentences, the word cyning (‘king’) does not look the same – it changes its form based on the grammatical role it plays:

Sē cyning is hēr. ( cyning = subject; this is called the ‘nominative’ case)

Iċ ġeaf þæt sweord þām cyninge . ( cyninge = indirect object; this is called the ‘dative’ case)

Does this sound complicated? Guess what – you already use (a very small number of) cases in modern English!

Look at this sentence:

The king’s sword is sharp.

Here’s the Old English equivalent, which uses the ‘genitive’ case:

Þæs cyninges sweord is sċearp.

Do you notice something similar between king’s and cyninges ?

You may have never thought about it before, but in order to denote possession, you regularly transform English words into the “genitive case” by adding an ‘s to the end. Although the Modern English possessive ’s doesn’t work exactly like the Old English -es ending, it is nevertheless the descendant of the Old English ending genitive -es .

An aside, if you’re curious: the difference between Old English -es and Modern English ’s is that ’s is what’s called a clitic . It goes on the end of the whole phrase, not the word that refers to the possessor: the Mayor of London’s hand is the hand of the mayor, not of the city.

The inflected nature of the grammar is one of the main differences between Old and Modern English. Grammar aside, though, the vocabulary should look relatively familiar: cyning isn’t too far off from king , especially once you know that the c is pronounced like a k , and sweord and sċearp are only a letter or two away from sword and sharp .

That combination sċ , by the way, is pronounced just like Modern English sh : so you should have no trouble recognizing sċip , fisċ , and bisċop as ship , fish , and bishop .

In fact, once you learn how the letters are pronounced, a modern English speaker can often understand many of the words in any given Old English passage. It’s just the relationships between the words that can pose a challenge.

"Old English" vs. "Anglo-Saxon"

Another word for Old English is Anglo-Saxon. In fact, Anglo-Saxon is the term you’ll see most often in sources from before the middle of the 20th century. Why two different terms for the same language?

Using either one is fine, though we often default to “Old English” because it highlights the continuity of the English language, and reminds us that Old English is the ancestor of Modern English, no matter how many French-isms have been absorbed into our language. There is potential for confusion, however, in using the term “Old English”: since, for example, Shakespeare’s English is still “old” to us. As a result, many people mistakenly think that Shakespeare wrote Old English plays and poetry, when, in fact, he wrote and spoke in what we call Early Modern English (this is the stage of the language people mean when they use the term “Elizabethan”). Using the term “Anglo-Saxon” for the language clears up that confusion.

But the term “Anglo-Saxon” has its own problems. Although the term Anglo-Saxon was used during the early Middle Ages (albeit in its Latin form Anglo-Saxones ), it wasn’t a term that the people used to refer to themselves. They just called themselves Englisc ‘English’. Besides, it totally ignores the Jutes! It also excludes anyone else who may have participated in the migration but didn’t retain a group identity once in England, such as the Frisians.

Since “Anglo-Saxon” was neither a term widely used by the people themselves and it does not include all the peoples it purports to describe, it has fallen out of favor in some circles.

Each term has its pros and cons , so you’ll likely see both used at one time or another.

The Old English Alphabet

Old English mostly used a version of the Latin alphabet, the same one Modern English uses.

However, the earliest Old English writing was done in runes, which is the name given to a family of alphabets used by the Germanic peoples before the adoption of the Latin alphabet. The name “rune” comes from an old Germanic word which means ‘secret’, which suggests that knowledge of runes was restricted to an elite, or that runes had some sort of esoteric meaning.

There is a long tradition of associating runes with magic: many runic inscriptions appear to be charms, and magic use of runes is explicitly mentioned in the Sigrdrífumál , an Old Norse text. The Old English runic alphabet was a variant of that used in Scandinavia. But the number of Old English texts written in runes is a very small fraction of the total amount of text written in Old English: runic Old English was mainly used for very short inscriptions on objects.

A particularly beautiful example of Runic Old English can be found on the Franks Casket , where references to the Germanic legend of Weyland the Smith, to Romulus and Remus, and to the Siege of Jerusalem (among other things) are briefly made.

Runic inscriptions aside, Old English was written in the Latin alphabet. But, compared to the version of the Latin alphabet used by Modern English, the Old English alphabet is missing a few letters: k, j, q, v, and z are used rarely or not at all. But Old English used a few letters we don’t: þ, ð, æ, and ƿ . When were they used? Read on.

Thorn Letter: þ

The letter called thorn is written þ (capital Þ). It comes from the Old English runic alphabet. As for the pronunciation of þ, there’s a clue in the name “thorn”: þ makes the sound at the start of the Modern English word th orn .

Depending on where it finds itself in the word, it can also make the sound written th in the Modern English word wea th er . Although these are technically different sounds, in Old English they were written the same (as they are in Modern English too: both are written with th !).

The English language continued to use þ into the Middle English period but, over time, the shape of the letter þ changed. By the late Middle Ages, the shape of þ had become almost indistinguishable from the letter y . When the printing press was invented, and the machines (which were imported from continental Europe) didn’t have þ, the printers substituted y , which is why we get things like ye (which is really the ), in “Ye olde shoppe”.

By the time of the printing press, however, þ had already fallen out of fashion and had been replaced by the two-letter combination th in most words, a situation which remains to this day.

Eth Letter: ð

The letter eth , written ð (capital Ð) was used in Old English in the exact same way that thorn was used: to make the sounds made by the Modern English letter combination th . Fun fact: eth was not the name that the Anglo-Saxons knew the letter by: they called it ðæt (pronounced like Modern English that ).

The two letters eth and thorn are interchangeable, and, although they varied in popularity over the years, both were often used on the same page by the same scribe. Unlike thorn, eth does not come from a runic source – it’s a modification of the Latin letter d . Eth lost its popularity much more quickly than thorn, and was already on its way out by the end of the Old English period.

Ash Letter: æ

The name ash is used for a letter that is made up of a combination of the letters a and e that looks like this: æ (capital Æ). This letter was used in Old English for the a sound used in most dialects of Modern English in the words hat or cat . The letter a on its own made a sound more like the vowel sound in f a ther (in most dialects of English). The letter æ is called ash after the name of the equivalent rune in the Old English runic alphabet.

Wynn Letter: ƿ

The letter wynn , written ƿ (capital Ƿ), is another letter adapted from the Old English runic alphabet. It makes the same sound as Modern English w , which replaced wynn in the Middle English period (via the intermediate step of uu , a literal “double u “, which is where we get the name of the letter w from). Most publishers of Old English texts or learning materials don’t bother writing the wynn, but rather substitute w in its place.

Another letter you may be wondering about is yogh , written ȝ (capital Ȝ). This letter was used in Middle English, not Old English, but it comes from a form of the letter g used in Old English, the “insular g”: ᵹ . The familiar form of g we use today was introduced in the Middle English period by scribes trained in France. But scribes didn’t get rid of the older insular g . Instead, they adapted it: ᵹ became ȝ. It was used to write a variety of sounds in Middle English, including those which we now write with the letter y (e.g., ȝise ‘yes’ ) and the combination gh (e.g., niȝt ‘night’ ). Over the Middle English period, ȝ was gradually replaced with y and gh .

Old English Phrases and Sentences

The speakers of Old English did not leave us a lot of evidence for how they spoke in daily life. In the Middle Ages, literacy was rare, and the production of books was laborious and expensive. People didn’t commit their casual chats to paper – that honor was reserved for works of religion, philosophy, and poetry. Rather formal stuff! This means we don’t know a great deal about the ways people spoke to each other from day to day.

But there are a few places where conversation is recorded : as dialogue in a poem, for example, or in example dialogues intended for use in schools.

The first English conversation ever recorded , in fact, was of the latter type: it occurs in the Colloquy of Ælfric (AD 1010) and is a dialogue between a teacher and student, written in Latin with an Old English version alongside. It was intended to be used as a teaching aid in schools, so it’s likely that it didn’t represent natural conversational speech.

Nevertheless, there’s still enough to have some idea of what the Old English equivalents to common phrases may have been. And where we lack direct evidence, if we’re willing to make educated guesses, we can extrapolate from other early Germanic languages and later forms of English to come up with reasonable guesses for what people may have said in different real-life situations.

Useful Phrases in Old English

In the collection of surviving Old English texts, we have a good selection of greetings and ways of saying thank you in Old English. Here are a few options.

Ic grete þe

‘I greet you’ (addressed to one person)

All of the following mean either ‘hello’ or ‘goodbye’, and should be addressed to one person:

Wes þu hal or hal wes þu .

Literally, this means ‘be healthy’.

Wes gesund .

Literally, this is another way of saying ‘be healthy’.

Sy þu hal .

This one is a slight variant on the previous examples: ‘may you be healthy’.

Here is a greeting you can address to multiple people:

Beoð ge gesunde .

Literally, this too means ‘be healthy’.

The modern ways of greeting someone in English, by wishing them a “good night” or “good morning”, seem to have come into the English language from French in the Middle English period, so we don’t have any evidence for Old English equivalents to those phrases.

To thank someone, you have a few options. To thank one person, you could say one of the following:

Ic þe þancas do .

Literally, this means ‘I do thanks to you’.

Ic þancie þe .

Literally, this one means ‘I thank you’.

To thank more than one person, you could say:

Ic sæcge eow þancas .

Literally, this means ‘I say thanks to you’.

Old English Insults

There are some great Old English insults in Beowulf . Here are a few:

Þonne wēne ic tō þē wyrsan geþingea